Abstract

To understand the role of white collar-2 in the Neurospora circadian clock, we examined alleles of wc-2 thought to encode partially functional proteins. We found that wc-2 allele ER24 contained a conservative mutation in the zinc finger. This mutation results in reduced levels of circadian rhythm-critical clock gene products, frq mRNA and FRQ protein, and in a lengthened period of the circadian clock. In addition, this mutation altered a second canonical property of the clock, temperature compensation: as temperature increased, period length decreased substantially. This temperature compensation defect correlated with a temperature-dependent increase in overall FRQ protein levels, with the relative increase being greater in wc-2 (ER24) than in wild type, while overall frq mRNA levels were largely unaltered by temperature. We suggest that this temperature-dependent increase in FRQ levels partially rescues the lowered levels of FRQ resulting from the wc-2 (ER24) defect, yielding a shorter period at higher temperatures. Thus, normal activity of the essential clock component WC-2, a positive regulator of frq, is critical for establishing period length and temperature compensation in this circadian system.

Predictable daily oscillations in environmental variables such as light and temperature have led to the evolution of circadian rhythms, endogenous programs that allow organisms to anticipate and respond appropriately to predictable environmental changes (53, 68). Circadian rhythms regulate a number of different physiological and developmental processes in diverse species, ranging from the sleep-wake cycle in humans to photosynthesis in single-celled algae. These rhythms persist under constant environmental conditions with a period length of about 24 h. The daily oscillations in light and temperature found in nature provide cues to which circadian clocks are responsive; these environmental variables provide reference points that synchronize the organism's internal clock (19).

Genetic and molecular analyses have identified a number of so-called clock genes involved in the generation of circadian rhythms, most notably in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, the filamentous fungus Neurospora crassa, the cyanobacterium Synechococcus, and mammalian systems (8, 18, 26, 35, 45, 56, 66, 67). Such studies have established that circadian rhythms are based in part upon transcription-translation-based negative feedback loops. In each case, oscillations in the transcript and/or protein levels of specific clock genes frequency (frq) and WC-1 (wc-1 transcript does not cycle) in fungi, kaiA and kaiBC in cyanobacteria, period, timeless (per and tim), and clk in flies, and mPer1, mPer2, mPer3, cry1, cry2, and Bmal1 in mammals appear to play a central role in the generation of rhythms. It has been shown that the proteins encoded by many of these loci negatively feed back to reduce the level of their own transcripts (18, 26, 30); thus, negative autoregulatory feedback appears to be a central process in the generation of circadian rhythms.

In Neurospora, light resetting of the clock occurs via a rapid and highly sensitive induction of frq transcript by light (13) that is mediated by the products of the white collar-I (wc-1) and white collar-2 (wc-2) genes (12). These genes were originally identified as mutations in Neurospora resulting in blindness for all photoresponses measured (28, 40). As expected, a wc-1 mutant photoblind for all measured light responses was also blind for light-regulated frq expression (12), thereby establishing a role for WC-1 in photoregulated phase entrainment of the clock. Surprisingly, in complete darkness, FRQ protein and frq mRNA were undetectable in the wc-1 mutant, and overt rhythmicity in this strain was never observed (12), demonstrating an essential role for WC-1 in the circadian oscillatory system. However, a presumptive null wc-2 mutant, which was photoblind for all measured light responses, retained partial inducibility of frq transcript in response to light or temperature pulses, although subsequent levels of the transcript and protein were very low and detectable cycling of frq mRNA, protein, or overt rhythmicity never followed. Thus it was predicted that wc-2 encodes a positively acting component of the Neurospora clock, but that it might play a limited role in the entrainment of the oscillator (12).

The proteins encoded by wc-1 and wc-2 are putative transcription factors. Both contain GATA type zinc fingers (Zn-fingers) that have been shown to bind to DNA sequences in the promoter of the albino-3 (al-3) gene, necessary for light induction of the al-3 transcript (7, 41). WC-1 and WC-2 also possess putative transcriptional activation and nuclear localization domains, features consistent with their proposed role as transcription factors (7, 17, 41). In addition, WC-1 and WC-2 have PAS domains, a domain known to mediate protein-protein interactions (25). Consistent with this, the PAS (PER, ARNT, and SIM) domains of WC-1 and WC-2 are required for these proteins to form both homo- and heterodimers in vitro (6), and WC-1 and WC-2 interact in vivo (17, 62) and with the negative clock component FRQ (17), perhaps as its dimer (10). These data have led to a model in which heterodimers of WC-1 and WC-2 regulate the majority of light-induced gene expression in Neurospora (62), while in darkness WC-1 and WC-2 are predicted to form PAS domain-mediated heterodimers and cooperate in increasing the levels of frq transcript (18, 44, 45). Furthermore, FRQ represses the level of its own transcript (3) by antagonizing the activity of WC-1–WC-2 heterodimers via direct interaction (17), giving rise to cyclical frq transcription (18). Similar models based on PAS-PAS heterodimer formation of the circadian transcriptional activators CLOCK-CYCLE and CLOCK-BMAL1 have been elaborated in D. melanogaster and mammals, respectively (1, 5, 14, 24, 29, 34, 38, 59).

The model of how eukaryotic clocks function that has thus emerged posits a transcription-translation-based negative feedback loop as an essential part of eukaryotic clocks (18, 31). Within this loop, levels of clock gene transcripts (e.g., frq) are positively regulated by heterodimers of PAS domain-containing transcription factors (e.g., WC-1 and WC-2). The arising clock proteins then function in a negative fashion to repress levels of their own transcripts by directly antagonizing the positively acting transcription factors (17). Presumably as a consequence of the lag between production of frq transcript and protein (18), there is an overshoot in the amount of FRQ made beyond the minimum amount needed to inhibit WC activation, contributing to the long time constant. Additionally, during the time FRQ levels are high, FRQ plays a positive role in increasing the levels of WC-1 protein through a posttranscriptional mechanism (39). The turnover of FRQ protein also contributes to the 24-h time constant (43), and once FRQ is degraded to low levels, the positively acting transcription factors WC-2 at a constitutively high level (17) and WC-1 at maximum levels, as induced by the presence of FRQ (39), are free to start the cycle again.

Because WC-2 acts in the absence of light as a positive element in the clock-associated feedback loop, a prediction from this model is that partial loss-of-function mutations in WC-2 might affect basic clock properties, as had been found with mutations in the negative component frq. Period length defects might occur from either an increase or decrease in transcriptional activation, although a defect in the property of temperature compensation was not foreseen. We examined the effect on the clock of several alleles of wc-2 reported to be temperature sensitive and found that strains carrying one of these alleles, wc-2 (ER24), had a lengthened period of clock-controlled conidiation under semipermissive conditions, defining a hypomorphic phenotype for wc-2 in the Neurospora clock as increased period length. Consistent with this observation, in constant darkness, levels of the essential clock components frq mRNA and FRQ protein were reduced in this mutant and cycled with an increased period. Sequence analysis of this allele revealed a mutation in the Zn finger, presumably altering a function of this domain.

In addition, this mutation altered a second canonical property of the biological clock, temperature compensation: as temperature increased, the speed of the clock increased (i.e., period length decreased). Previously, temperature compensation defects have been found only in negative regulators of the clock, including long-period alleles of frq in Neurospora (23) and alleles of both per (27, 36) and tim (timrit [49]) in Drosophila.

We examined frq mRNA levels at 25 and 30°C and found that they were largely unchanged by temperature. However, this decrease in period with increasing temperature was concomitant with an increase in FRQ levels, consistent with expectations that the levels of FRQ and its transcript are critical determinants for period length and a temperature-compensated clock. Thus, WC-2, as a positive regulator of frq, is an essential component of the Neurospora circadian system.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains, crosses, growth conditions, and race tube assay.

General conditions for growth and manipulation of N. crassa have been described elsewhere (15). Race tube assays and rhythmic liquid cultures were performed as previously described (48) with the exception that 1× Vogel's salts and 100 μM ZnCl2 were used in all experiments. For acquisition of rhythm data, either race tubes or pictures of race tubes (5 in. by 7 in. [ca. 13 cm by 18 cm]) were scanned using a LaCie Silver Scanner III and thereby converted into a PICT file for analysis by CHRONO (55). The daily rhythm in conidial density was quantified as the number of white pixels in each vertical line of the image. The vertical scale for each image was arbitrarily chosen to scale the amplitude of the rhythm to the space allowed in each figure.

N. crassa strains containing wc-2 alleles ER24 (FGSC 4405) and ER44 (FGSC 4410) were obtained from the Fungal Genetics Stock Center (University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, Kans.). Upon receipt, the FGSC 4405 and 4410 strains were immediately crossed with strains containing band (bd) for generation of the wc-2 (ER24) and wc-2 (ER44) strains used in this study for circadian analysis. The bd mutation, referred to as wild type throughout, has two clear phenotypes, reduced growth rate and increased conidiation; it allows clear observation of the overt rhythm in conidiation but has no effect on the underlying clock mechanism (52). The null allele Δwc-2 contains the bd mutation and is a complete gene replacement of the wc-2 open reading frame (ORF) with the bacterial hygromycin phosphotransferase gene (M. A. Collett, J. C. Dunlap, and J. J. Loros, unpublished data).

PCR and DNA sequencing.

Standard molecular genetic techniques were performed as described (60). Genomic DNA of Neurospora strains was extracted using standard protocols (4). For sequence analysis of the different wc-2 alleles, PCR was performed on genomic DNA from strains containing the mutant allele of interest using Taq DNA polymerase (Gibco-BRL) with primers designed to the published wc-2 sequence (41) (DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank accession number Y09119) so that overlapping fragments were generated. PCR products visible as a single band on an agarose gel were purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). Purified PCR products were sequenced using ABI PRISM BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing Ready Reaction kit with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase. The resulting DNA fragments were electrophoresed and analyzed using an automated ABI model 373 DNA Stretch sequencer, and sequences were assembled and analyzed using LaserGene Navigator 1.59 software from DNAStar. For each allele of wc-2, both strands of the entire ORF and introns were sequenced, with at least one strand sequenced twice for all regions analyzed.

RNA and protein analysis.

RNA analysis was performed as described previously (13). Western blot analysis was performed as previously described (22). X-ray films of Western and Northern blots were scanned and densitometry was performed using NIH Image 1.59.

Sequence alignments.

Sequences were initially aligned in Gene Inspector (Textco), and the alignment was then realigned in MultiAlin (11), accessed through the Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique website (http: //www.toulouse.inra.fr/multalin.html). Gap weight was set at 15, and the low consensus level was set at 25%, with all other parameters at default setting.

RESULTS

Partially functional wc-2 gives a long period.

We reasoned that if WC-2 is a component of the Neurospora clock, positively regulating levels of frq mRNA, it should be possible to obtain period length mutations in the clock caused by hypo- or hypermorphic mutations in wc-2. Two alleles of wc-2, ER24 and ER44, reported as temperature sensitive for light-induced carotenogenesis, were previously isolated in a screen for photoblind Neurospora mutants (16). The authors concluded that at the permissive temperature of 26°C, there was partial carotenogenesis in these wc-2 alleles, while at the nonpermissive temperature of 34°C, there was no evidence of carotenogenesis. We analyzed temperature sensitivity of carotenogenesis in our bd-containing wc-2 alleles (see Materials and Methods) in both liquid and solid media, using bd and bd Δwc-2 strains as positive and negative controls, respectively. Visual examination of cultures at 25 and 34°C over 3 days after transfer from dark to light found no significant difference between the bd-containing ER24 strain and the null allele Δwc-2, both showing no carotenogenesis at any time point above dark-grown levels. The wild-type strain, containing the bd mutation, showed an increase in carotenoids over time in light, as expected. This increase was greater at 25 than at 34°C. The ER44 strain also showed an increase in carotenoid content, although lower than the wild type, after lights on at 25°C, but showed no increase at 34°C. As carotenogenesis in the wild type displayed a temperature-dependent decrease, it was not possible to distinguish between a general decrease in overall carotenoid production and a temperature sensitivity-induced inability to produce carotenoids at the higher temperature. Therefore, we cannot conclude that the ER44 allele, when containing the bd mutation in the genome, is an actual temperature-sensitive as opposed to a partially functional allele.

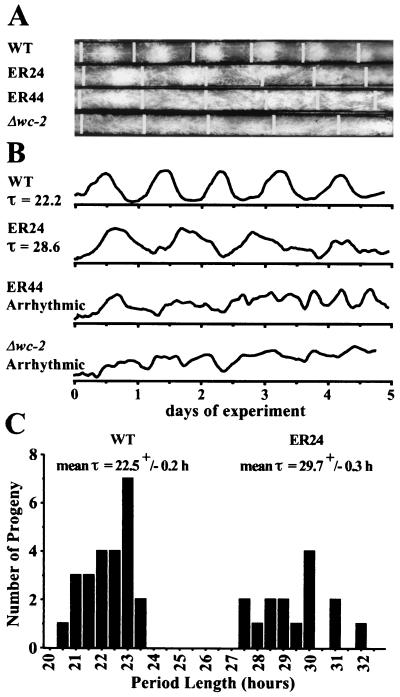

To examine the role of WC-2 in the Neurospora clock, we analyzed rhythmic conidial spore production in strains bearing wc-2 (ER24) and wc-2 (ER44). Furthermore, to determine the clock phenotype of a true null allele of wc-2, we examined a strain containing a definitive null allele of wc-2, Δwc-2, created by deleting the entire wc-2 ORF (Collett et al., unpublished). Strains containing wc-2 (ER44) and Δwc-2 were arrhythmic on race tubes (Fig. 1A and B), the same arrhythmic clock phenotype previously reported for wc-2 (ER33) (12, 58). However, wc-2 (ER24) strains possessed a novel clock phenotype, displaying a long period rhythm of 29.7 ± 0.3 h (Fig. 1A, B, and C) that frequently damped, so that individual race tubes usually became arrhythmic. At 25°C, about 70% of cultures could sustain rhythmicity for three or four circadian days. In crosses of strains containing these mutant wc-2 alleles, the clock defects segregated with the defects in light-induced carotenogenesis, so the prediction that partial wc-2 function results in a partially functional and slower clock proved to be correct for the ER24 allele. The strain carrying the ER44 allele, under the conditions used here, appeared to be an extreme hypomorph unable to support clock function. Arrhythmicity in the Δwc-2 allele is indicative of the essential nature of WC-2 in the clock.

FIG. 1.

Partially functional wc-2 allele, ER24, results in a long period, while wc-2 (ER44) and a null allele, Δwc-2, are arrhythmic. (A) Race tube analysis showing the banding rhythm at 25°C in strains possessing either a wild-type (WT) allele of wc-2, wc-2 (ER24), wc-2 (ER44), or Δwc-2. The strain possessing wc-2 (ER24) has a long period, and wc-2 (ER44) and Δwc-2 are arrhythmic. Race tubes were inoculated at the left end, incubated in constant light at room temperature for 2 days, and then transferred into darkness at 25°C, at which point the growth front (vertical white line) was marked. Growth fronts were marked at 24-h intervals thereafter. (B) Densitometric analysis of race tubes, plotting conidial density over time. The period length (τ) is indicated where relevant. (C) Distribution of period length in progeny possessing the bd mutation from a cross of bd with wc-2 (ER24). Period length cosegregated with light-induced mycelial carotenogenesis, and those progeny possessing wc-2+ (WT) or wc-2 (ER24) photoresponses are indicated with mean period length (τ) ± standard error of the mean (SEM) above the appropriate group.

Sequence analysis of wc-2 (ER24) and wc-2 (ER44) reveals Zn finger and splicing defects.

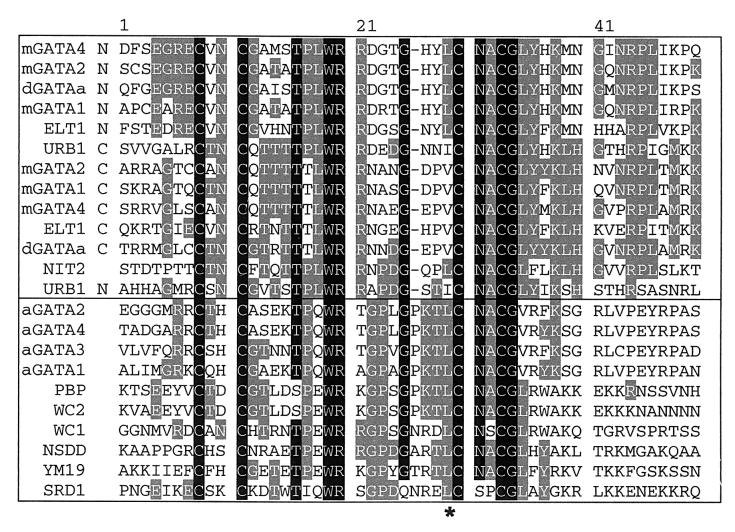

The wc-2 ER24 and ER44 alleles were sequenced to determine the nature of the mutations in these strains. ER24 is the result of a C→A point mutation at nucleotide 4926 in the published wc-2 sequence (42), causing Leu→Ile at a conserved position in the Zn finger DNA-binding domain of WC-2; in Fig. 2, this corresponds to amino acid residue 29 and is marked with an asterisk. Two forms of type IV Zn fingers have been identified based on sequence comparisons, type IVa and type IVb. Both WC-2 and WC-1 possess type IVb Zn fingers (7, 63), and the Leu altered in WC-2 (ER24) is conserved in all members of the type IVb Zn fingers so far identified (Fig. 2). This mutation presumably alters the function of the Zn finger (see Discussion), either weakening the DNA-binding ability of ER24-encoded WC-2 or altering protein-protein interactions, both processes mediated by Zn fingers in a number of different proteins (33, 50).

FIG. 2.

Sequence alignment of the Zn finger domain of WC-2 and other proteins from the GenBank protein and nucleic acid sequence databases. The top group of sequences are all type IVa Zn fingers, and the bottom group are all type IVb Zn fingers (using the designation of Teakle and Gilmartin [63]). A black background marks residues which are found in 90% or more of the sequences, and those which are found in 25 to 90% are shown by a gray background. An asterisk marks the mutated amino acid of allele ER24. An N or a C after the protein name indicates the N- or C-terminal Zn finger of that protein. The organism and GenBank accession number for the different sequences are mGATA4 (Mus musculus, GenBank 3183530), mGATA2 (M. musculus, 1754586), dGATAa (D. melanogaster, 709699), mGATA1 (M. musculus, 120957), ELT1 (Caenorhabditis elegans, 119299), URB1 (Ustilago maydis, 731074), NIT2 (N. crassa, 128352), aGATA2 (Arabidopsis thaliana, Y13648), aGATA4 (A. thaliana, Y13651), aGATA3 (A. thaliana, Y13650), aGATA1 (A. thaliana, Y13648), PBP (Fusarium solani, 1362526), WC-2 (N. crassa, 1835159), WC-1 (N. crassa, 2494692), NSDD (Aspergillus nidulans, 1617552), YM19 (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, 732160), and SRD1 (S. cerevisiae, 140465).

In ER44, the single point mutation identified is in the first intron of wc-2, at nucleotide 3484 in the published sequence. The nucleotide mutated is in the midst of a perfect match to the Neurospora lariat consensus sequence (G/A)CT(A/G)AC (9); the T in this sequence has been mutated to a C in ER44, presumably resulting in loss of splicing or missplicing of the transcript. The outcome of this would be a premature translational stop, yielding a protein having just 48 amino acids of the 530-amino-acid WC-2 protein (17, 41). It seems likely that this loss of splicing would result in a nonfunctional protein, although wc-2 (ER44) has been reported as a temperature-sensitive allele (16).

In confirmation of this putative splicing defect, analysis of reverse transcription-PCR amplification products from WT and ER44 RNAs indicated that the bulk of the ER44 mRNA was unspliced for the first intron, with no evidence for the use of any cryptic splice sites. The second intron was spliced correctly. There was, however, a very low level of correctly spliced RNA in the mutant, compatible with the partially functional phenotype of ER44 (data not shown). Possibly there is a temperature-sensitive defect in splicing, allowing more or less efficient splicing at different temperatures, but all at reduced efficiency, as discussed by Hamblen et al. (27) for the temperature-sensitive per04 mutation in flies. Western analysis of WC-2 protein levels shows no detectable WC-2 above background in the ER44 lanes (data not shown). Given the arrhythmic clock phenotype of ER44 (Fig. 1) and other phenotypes of this strain (Collett et al., unpublished), ER44 appears to be a more extreme hypomorph than ER24.

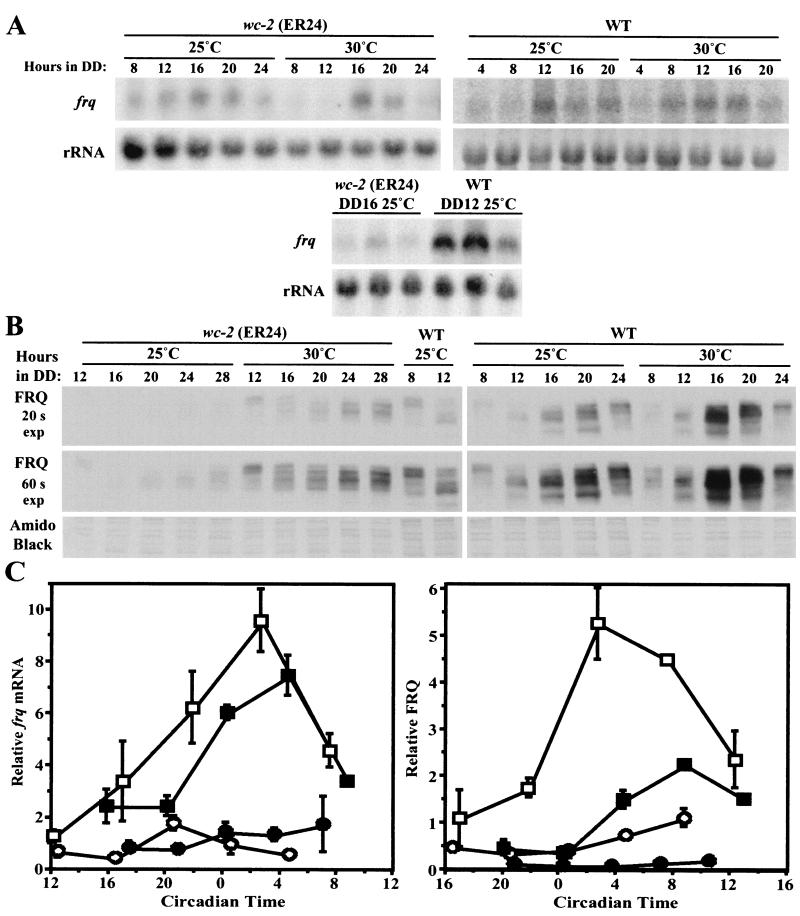

Partially functional WC-2 gives reduced dark levels of frq mRNA and FRQ protein.

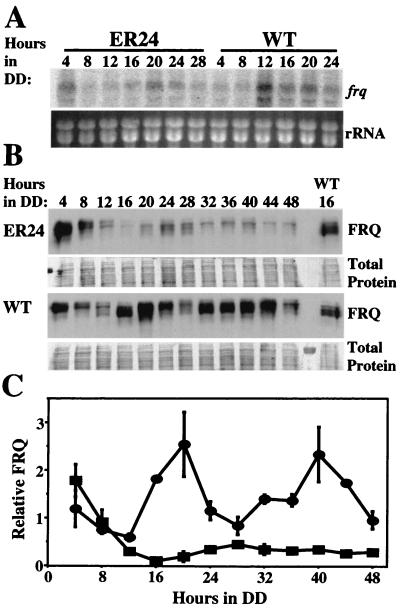

As WC-2 is important for strong expression of frq in the dark (12), a likely result of the wc-2 (ER24) mutation would be a reduction in frq expression levels. This is the case; levels of frq mRNA and protein synthesized in the dark (Fig. 3A and B) in a wc-2 (ER24) background were reduced by severalfold compared to the wild type. The levels of frq mRNA in ER24 peaked later than in the wild type (Fig. 3A), and FRQ protein in ER24 cycled with a long period and damped through a reduction in peak levels (Fig. 3B and 3C). The cycle in FRQ is most clearly followed by examining the progressive shift in mobility of FRQ observed throughout the FRQ oscillation (22). (Newly synthesized FRQ has the highest mobility of FRQ forms observed, and as the cycle progresses, phosphorylation of FRQ results in a gradual decrease in mobility.) Additionally, in contrast to poor expression in the dark, FRQ levels in constant light are similar in wc-2 (ER24) and the wild type (Collett et al., unpublished), so that the first 8 h in darkness, during which no FRQ synthesis occurs, allows a comparison of FRQ stability in ER24 and the wild type. After 4 and 8 h in darkness (DD4 and DD8, respectively), FRQ is at similar levels and a similar mobility in the wild type and wc-2 (ER24), suggesting that FRQ has a similar turnover rate in both strains. At DD12, newly synthesized FRQ is beginning to appear below the highly phosphorylated form of FRQ in the wild type; in ER24, however, only the highly phosphorylated form of FRQ is obvious at this time. By DD16, a large bolus of newly synthesized FRQ is present in the wild type. However, in ER24, FRQ is almost entirely absent at DD16, and no newly synthesized FRQ is apparent in this strain until DD20, when a small quantity of lower-molecular-weight FRQ is apparent, with more accumulating at DD24 and DD28. These data are consistent with expectations for a partially functional positive regulator of frq: levels of frq mRNA and FRQ are reduced throughout the cycle, FRQ drops for a longer time (16 h to the trough after the light-to-dark step in ER24 as opposed to 12 h in the wild type), frq mRNA and thus FRQ protein take a longer time to reach peak due to weakening in a positive component of the loop. Moreover, the peak levels reached in the dark are lower than the peaks in a wild-type strain. As mentioned, the degradation rate of FRQ appears to be similar in wc-2 (ER24) and the wild type; however, FRQ levels drop for a longer time in ER24, as in this mutant it takes longer for new FRQ to be synthesized.

FIG. 3.

Levels of frq mRNA and protein are reduced in a strain containing wc-2 (ER24) grown at 25°C. (A) Northern blots of frq mRNA in wc-2 (ER24) and a wild-type (WT) strain over one circadian cycle. Ethidium bromide staining of the rRNA bands on the agarose gel is shown below the Northern blot. (B) Western blot of FRQ protein in wc-2 (ER24) and a wild-type strain over 48 h. The amido black-stained membrane is shown below the blot of FRQ. A wild-type reference sample from DD16 was included on the ER24 blot and on the wild-type blot to allow a comparison of the levels of FRQ between the strains. The level of FRQ is greatly reduced in the wc-2 (ER24) strain compared to the wild type and cycles with an altered period. (C) Densitometric analysis plotting the amount of FRQ normalized against the wild-type DD16 reference sample versus time. Squares, wc-2 (ER24); circles, wc-2+. Each point corresponds to the mean of two experiments. Error bars show the SEM.

Thus, in the wc-2 (ER24) mutant, the negative feedback loop has been tipped off balance; the portion of the loop where the positive factors activate has been lengthened and impaired, leading to a longer period, weaker oscillations, and damping of the rhythm.

Partially functional wc-2 results in reduced temperature compensation.

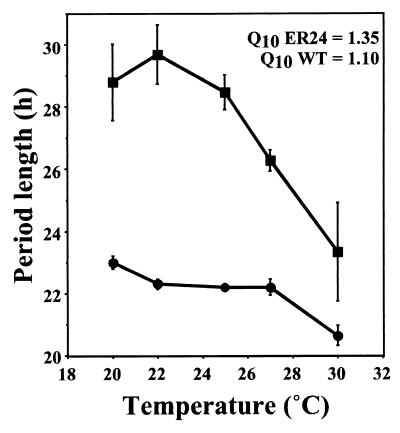

As wc-2 (ER24) had previously been reported to be a temperature-sensitive allele (16), we were interested in examining the effect of temperature on the circadian period of this strain. Given the decreased frq expression resulting from decreased WC-2 activity and increased period length of the clock, we expected that as temperature increased (leading to a concomitant decrease in the activity of a temperature-sensitive protein), the period length of this strain would continue to lengthen until the nonpermissive temperature for this allele was reached, at which point arrhythmia would result. We examined the period length between 20 and 30°C in this strain and compared this to a wild-type strain (Fig. 4). Surprisingly, what we observed was the opposite of what we had expected: rather than period increasing with temperature due to a weakening in the activity of WC-2, the period length instead shortened with increasing temperature. This is reminiscent of the behavior of the long-period alleles of frq (23). This period shortening at higher temperatures is reflected in a Q10 greater than 1, where Q10 is the rate of an activity at a given temperature versus that at 10°C higher. For example, within the physiological range, a perfectly compensated clock would have a Q10 of exactly 1.0.

FIG. 4.

Reduced temperature compensation in a strain containing wc-2 (ER24). Mean period plotted against temperature for wc-2 (ER24) and clock wild type (WT). Squares, wc-2 (ER24); circles, wc-2+. Error bars show the SEM. Q10 from 25 to 30°C was calculated from the equation Q10 = (P2/P1)10/T1−T2, where P1 and P2 are mean periods at temperatures T1 and T2, respectively (64).

Next we looked at frq mRNA and FRQ protein levels in ER24 and wild-type strains at 25 and 30°C to determine what effect temperature had on the levels of these clock gene products. If wc-2 (ER24) encodes a temperature-sensitive protein required for regulation of frq transcript levels, then increasing temperature would lead to reduced frq expression at higher temperatures. Alternatively, ER24 may not be temperature sensitive for frq regulation, which should give little effect of temperature on frq mRNA levels. We were also interested in examining FRQ protein levels, as these are known to be regulated posttranscriptionally by temperature, with overall FRQ levels increasing with temperature (43a, 43b). We thought that this temperature-dependent posttranscriptional increase in FRQ could in part explain the temperature compensation defect caused by wc-2 (ER24); increasing temperature would lead to increased FRQ, to some degree rescuing the defect (reduced production of FRQ) imparted by the ER24 mutation.

We analyzed strains bearing wc-2 (ER24) and wc-2+ for levels of frq transcript and protein at 25 and 30°C (Fig. 5). Levels of frq transcript were much reduced in wc-2 (ER24) compared to the wild type (Fig. 5A and C), as observed in the experiment shown in Fig. 3; however, no large difference in overall frq transcript levels in either strain was detected between the two temperatures, suggesting that ER24 is not temperature sensitive for regulation of frq mRNA. In contrast to frq mRNA, the overall amount of FRQ protein in the wild type increased with temperature at all times (Fig. 5B and C), and FRQ levels were again reduced in wc-2 (ER24) compared to the wild type. In a wc-2 (ER24) strain at 30°C, total FRQ levels were increased at all points compared to levels at 25°C, demonstrating that the temperature-dependent increase in FRQ levels seen in the wild type is present in ER24. Relative to FRQ levels at 25°C, the increase in FRQ with temperature in ER24 is greater than that in the wild type: in ER24 there was a 5.4-fold increase in FRQ peak levels when temperature increased from 25 to 30°C, while in the wild type there was a 2.3-fold increase (average of two experiments). The data in Fig. 5 suggest that the ER24 temperature compensation defect is a consequence, at least in part, of the greater relative temperature-dependent increase in FRQ levels in ER24. This overall increase in FRQ levels results in a shorter period at higher temperatures.

FIG. 5.

Elevated temperature results in increased FRQ levels in wc-2 (ER24) strains and wild type. (A) Representative Northern blots of frq mRNA in strains containing either wc-2 (ER24) or wc-2+ grown at 25 or 30°C. The membrane of blotted RNA was cut in half between the large and small nuclear ribosomal subunits, the top half was hybridized to a probe specific for frq, and the bottom was hybridized to a probe for rRNA. To allow comparison of relative frq mRNA levels between the two strains, reference samples corresponding to peak frq mRNA levels from wc-2+ (DD12) and wc-2 (ER24) (DD16) were compared in triplicate (bottom). (B) Representative Western blots of FRQ in strains containing wc-2 (ER24) or wc-2+ grown at 25 or 30°C. Two different exposures, 20 and 60 s, of the blots are shown for each temperature. The amido black-stained membrane is shown as an estimate of loading. Wild-type samples were included on each blot for reference to allow a comparison of the levels of FRQ between the strains. (C) Densitometric analysis plotting the relative amounts of frq mRNA and FRQ protein versus time. Each point corresponds to the mean of two experiments for FRQ and three experiments for frq mRNA ±, SEM. For each sample, the density of the frq or FRQ signal was divided by the corresponding density of the rRNA or amido black-stained protein. These values were then normalized to the reference sample for each blot. Squares, wc-2+; circles, wc-2 (ER24); solid symbols, 25°C; open symbols, 30°C.

Levels of WC-2 protein in the wild type and wc-2 (ER24) at 25 and 30°C have also been measured over the time course shown for FRQ (17) (M. A. Collett and D. L. Denault, unpublished data); neither temperature nor the wc-2 (ER24) mutation had an effect on WC-2 levels. Thus, the differences observed in frq levels between ER24 and the wild type are presumably due to activity of WC-2 and are not due to differences in the amount of WC-2 in the cell.

The relationship between frq mRNA and protein oscillations also appears to have changed in wc-2 (ER24). This is most clearly seen at 30°C, where frq mRNA peaks 16 h after lights off (about circadian time 20 [CT20], subjective late night), but the peak in FRQ is delayed until 28 h after the light-to-dark transition (about CT8, subjective midday), increasing the lag between transcript and protein in ER24. A similar difference is seen in ER24 at 25°C, although frq mRNA oscillations are less controlled under these conditions and have lowered amplitude, with frq sometimes unpredictably high at times other than 16 to 20 h after transition into the dark (CT0–4, subjective morning). The occasional unpredictability in frq mRNA oscillations at 25°C is presumably due to very low FRQ levels.

DISCUSSION

We have demonstrated here that an allele of wc-2, wc-2 (ER24), thought to encode a partially functional protein, gives a lengthened period of the circadian rhythm in N. crassa. WC-2 (ER24) has a mutation in the Zn finger domain, replacing a highly conserved leucine with an isoleucine. This partially functional WC-2 results in reduced levels of the essential clock components frq mRNA and FRQ protein. Additionally, this mutation results in reduced temperature compensation of the period, while the wc-2 (ER44) and Δwc-2 alleles result in arrhythmicity. The phenotypes imparted by these alleles are all consistent with the predicted role of wc-2 as a transcriptional activator of frq transcription, i.e., a positive component in a negative feedback loop of the Neurospora clock. A major determinant of period length in the wild type is thought to be the rate of FRQ turnover (43, 57). In the ER24 mutant, the period length of the rhythm reflects not only the rate of FRQ turnover but also the rate of frq synthesis, demonstrating that period can be affected by both the rate of accumulation of frq mRNA and FRQ protein and the rate of FRQ turnover.

Another allele of wc-2, wc-2 (ER33), containing what is predicted to result in an extreme alteration to the Zn finger, results in greatly reduced levels of frq mRNA and FRQ and arrhythmicity in constant darkness (12). This, in addition to the data here, demonstrates that the Zn finger of WC-2 plays a critical role in determining levels of frq expression in darkness. We have further shown here that the function specified by the WC-2 Zn finger is critical for a temperature-compensated clock and can be a determinant of period length. Zn finger domains are typically involved in DNA binding and/or protein-protein interactions (33, 50). The Zn fingers of WC-2 and WC-1 have both been shown to bind elements in the promoter of a light-responsive transcript (7, 41). It is possible that these mutations in the Zn finger of WC-2 decrease its ability to bind DNA in the frq promoter, and this results in lowered levels of frq transcription.

The Zn finger of WC-2 (and WC-1) is similar to type IV Zn fingers, a well-characterized class which generally bind the consensus sequence (A/T)GATA(A/G) and are thus known as GATA Zn-fingers (20, 21, 37, 51, 65). From sequence comparisons, type IV Zn finger proteins have been shown to form two distinct subclasses: type IVa, containing the conserved motif C-X2-C-X17-C-X2-C, and type IVb (including WC-1 and WC-2), containing the conserved motif C-X2-C-X18-C-X2-C (63), where Xn indicates a stretch of n residues. The features that distinguish type IVa fingers from type IVb include the spacing of the conserved cysteine pairs as well as differences between conserved amino acid residues between the cysteine pairs. Of particular note are residues at position 18 and 29 in the amino acid alignment in Fig. 2. In all type IVa Zn fingers, the residue at position 18 is a leucine (L18). Structural and genetic analysis of type IVa Zn fingers demonstrates that L18 plays a critical role in DNA binding by these Zn fingers (61). In type IVb Zn fingers, this residue is no longer conserved, being a glutamine, glutamate, or threonine. Conversely, in type IVb Zn fingers, residue 29 is always a leucine (L29). In WC-2 (ER24), L29 has been mutated to an isoleucine, which substantially alters the function of WC-2; however, this residue may be a leucine, valine, or isoleucine in type IVa Zn fingers. Given the ER24 mutation and the differences between type IVa and IVb Zn fingers noted above, it is tempting to speculate that L29 in the type IVb Zn fingers plays a more critical role in Zn finger function.

Whatever the biochemical basis for the lowered frq transcript levels in the wc-2 (ER24) mutant, clearly a positive part of the frq cycle has been altered, resulting in a lowered amplitude of frq oscillations (from 10-fold in the wild type to 5-fold in ER24) and lengthened period. Hence, wc-2 (ER24) causes FRQ levels to rise for a longer time but to a lower level than in the wild type. One surprising difference between the rhythms in frq mRNA and FRQ protein in wc-2 (ER24) and the wild type is that ER24 has a greater lag between the peak in frq mRNA and peak in FRQ protein. In the wild type the lag is about 4 h, while in ER24 it is closer to 8 h. A mutation which most likely alters transcriptional regulation of frq would not have been predicted to alter the lag time between appearance of RNA and protein, suggesting that generation of the lag may be complex.

The change in the FRQ rhythm in wc-2 (ER24) is of interest, as in the simplest case one could imagine two possible outcomes for this part of the Neurospora circadian oscillator (as we currently understand it) with a weakened positive component. In one scenario, FRQ protein levels must reach a certain threshold before negative feedback is triggered, and this threshold would be independent of the rate of FRQ synthesis; the clock would measure FRQ levels, and once this threshold was reached, negative feedback would be triggered, as in a relaxation oscillator. Alternatively, once FRQ is present, it begins negative feedback independent of FRQ levels; in this case, negative feedback would reflect the rate of FRQ synthesis and activity (which may include modification of FRQ to an active form). The fact that FRQ synthesized in the dark in wc-2 (ER24) never reaches the same levels as in the wild type argues against a simple relaxation oscillator. However, the time lag between the peaks in frq mRNA and protein increases in ER24, suggesting a critical level of FRQ is needed for the oscillator to function, and the weakening in frq activation in ER24 mean a longer time is required for this critical level to be achieved. This issue is complex; negative feedback may require multiple components, the ER24 mutation may have different effects on these components, and all result in reduced levels of the protein FRQ, which is required to promote synthesis of WC-1 (39).

The finding of period length defects caused by a mutation in wc-2 adds to the similarities between the Neurospora clock and the clocks of mammals and fruit flies. The hypomorphic mutation in wc-2 resulting in lengthened period and eventual damping of the rhythm is a similar phenotype to that possessed by mice homozygous for the Clock mutation (66) and Drosophila flies heterozygous for the Cyc or ClkJrk mutation (1, 59). These three mutations all affect genes, like wc-2 and wc-1, that encode PAS domain-containing positive-acting transcription factors, which are understood to activate transcription of the negatively acting clock genes per and tim in flies and the mper genes in mammals (14, 24, 29). In agreement with the role of these genes as positive factors, all three mutations result in lowered mRNA levels of the relevant clock genes (1, 32, 59).

The temperature compensation defect in wc-2 (ER24), however, was novel and unexpected; until now, defects in temperature compensation caused by mutations in single genes have only been noted in alleles of the negative elements frq (2, 23; see also 46), per (27, 36), and tim (49) and in the hamster tau mutant, which encodes casein kinase I epsilon hypomorphic for phosphorylation of mPER1 (47, 54, 64). The reduced temperature compensation in a wc-2 (ER24)-containing strain suggests that temperature compensation probably results from an interplay between positively and negatively acting elements in the circadian cycle. The period shortening as temperature increases in ER24 is correlated with the temperature-dependent increase in FRQ levels. However, this increase in FRQ levels is also observed in the wild type, with only a mild period shortening effect observed, prompting the question of why this effect is so great in ER24 compared to the wild-type strain. A possible explanation is that, relative to FRQ levels at 25°C, the increase in FRQ with temperature in ER24 is greater than the corresponding increase in the wild type. This greater relative increase in FRQ might lead to a period-shortening effect, partially rescuing the decreased levels of FRQ found in wc-2 (ER24) and leading to a shortened period at higher temperatures. The greater increase in FRQ in ER24 suggests that there may be a mechanism regulating FRQ levels with temperature. Perhaps once FRQ exceeds a given level at a given temperature, the excess FRQ is degraded. However, FRQ levels in ER24 would be so low that this mechanism would have only a very small effect on FRQ levels in the mutant.

It is clear that wc-2 is a positively acting component of the Neurospora clock, a positive regulator of levels of frq mRNA. Determination of the mechanism of action of WC-2 on the frq promoter, be it direct or indirect (through other proteins), is critical for a future understanding of the clock in Neurospora.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of our laboratory for thoughtful discussions. We are especially grateful to Allan Froehlich, Hildur Colot, and Minou Nowrousian for experimental help and to anonymous reviewers for constructive suggestions on earlier drafts of the manuscript.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM 34985 and MH01186 to J.C.D., MH44651 to J.C.D. and J.J.L.), the National Science Foundation (MCB-0084509 to J.J.L.), and the Norris Cotton Cancer Center core grant at Dartmouth Medical School.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allada R, White N E, So W V, Hall J C, Rosbash M. A mutant Drosophila homolog of mammalian Clock disrupts circadian rhythms and transcription of period and timeless. Cell. 1998;93:791–804. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81440-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson B D, Johnson K A, Dunlap J C. The circadian clock locus frequency: a single ORF defines period length and temperature compensation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:7683–7687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aronson B D, Johnson K A, Loros J J, Dunlap J C. Negative feedback defining a circadian clock: autoregulation of the clock gene frequency. Science. 1994;263:1578–1584. doi: 10.1126/science.8128244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aronson B D, Lindgren K M, Dunlap J C, Loros J J. An efficient method of gene disruption in Neurospora crassa. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;242:490–494. doi: 10.1007/BF00281802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bae K, Lee C, Sidote D, Chuang K-Y, Edery I. Circadian regulation of a Drosophila homolog of the mammalian Clock gene: PER and TIM function as positive regulators. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6142–6151. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.6142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballario P, Talora C, Galli D, Linden H, Macino G. Roles in dimerization and blue light photoresponses of PAS and LOV domains of Neurospora crassa white collar proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:719–729. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ballario P, Vittorioso P, Magrelli A, Talora C, Cabibbo A, Macino G. white collar-1, a central regulator of blue-light responses in Neurospora crassa, is a zinc-finger protein. EMBO J. 1996;15:1650–1657. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bell-Pedersen D. Understanding circadian rhythmicity in Neurospora crassa: from behavior to genes and back again. Fungal Genet Biol. 2000;29:1–18. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.2000.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruchez J, Eberle J, Russo V. Regulatory sequences in the transcription of Neurospora crassa genes: CAAT box, TATA box, introns, poly(A) tail formation sequences. Fung Genet News. 1993;40:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng P, Yang Y, Heintzen C, Liu Y. Coiled-coil domain-mediated FRQ-FRQ interaction is essential for its circadian function in Neurospora. EMBO J. 2001;20:101–108. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corpet F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10881–10890. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.22.10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crosthwaite S C, Dunlap J C, Loros J J. Neurospora wc-1 and wc-2: Transcription, photoresponses, and the origins of circadian rhythmicity. Science. 1997;276:763–769. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5313.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crosthwaite S C, Loros J J, Dunlap J C. Light-induced resetting of a circadian clock is mediated by a rapid increase in frequency transcript. Cell. 1995;81:1003–1012. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Darlington T K, Wager-Smith K, Ceriani M F, Stankis D, Gekakis N, Steeves T, Weitz C J, Takahashi J, Kay S A. Closing the circadian loop: CLOCK induced transcription of its own inhibitors, per and tim. Science. 1998;280:1599–1603. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis R L, deSerres D. Genetic and microbial research techniques for Neurospora crassa. Methods Enzymol. 1970;27A:79–143. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Degli-Innocenti F, Russo V. Isolation of new white collar mutants of Neurospora crassa and studies on their behavior in the blue light-induced formation of protoperithecia. J Bacteriol. 1984;159:757–761. doi: 10.1128/jb.159.2.757-761.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Denault D, Loros J, Dunlap J. WC-2 mediates WC-1-FRQ interaction within the PAS protein-linked circadian feedback loop of Neurospora. EMBO J. 2001;20:109–117. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunlap J. Molecular bases for circadian clocks. Cell. 1999;96:271–290. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80566-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Edmunds L N., Jr . Cellular and molecular bases of biological clocks. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans T, Felsenfield G. The erythroid-specific transcription factor Eryf1: a new finger protein. Cell. 1989;58:877–885. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90940-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu Y-H, Marzluf G. nit-2, the major positive-acting nitrogen regulatory gene of Neurospora crassa, encodes a sequence-specific DNA-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:5331–5335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.14.5331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garceau N, Liu Y, Loros J J, Dunlap J C. Alternative initiation of translation and time-specific phosphorylation yield multiple forms of the essential clock protein FREQUENCY. Cell. 1997;89:469–476. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80227-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardner G F, Feldman J F. Temperature compensation of circadian periodicity in clock mutants of Neurospora crassa. Plant Physiol. 1981;68:1244–1248. doi: 10.1104/pp.68.6.1244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gekakis N, Staknis D, Nguyen H B, Davis F C, Wilsbacher L D, King P Y, Takahashi J S, Weitz C J. Role of the CLOCK protein in the mammalian circadian mechanism. Science. 1998;280:1564–1569. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5369.1564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gu Y-Z, Hogenesch J B, Bradfield C A. The PAS superfamily: sensors of environmental and developmental signals. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000;40:519–561. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.40.1.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hall J C. Tripping along the trail to the molecular mechanisms of biological clocks. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:230–240. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)93908-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamblen M J, White N E, Emery P T, Kaiser K, Hall J C. Molecular and behavioral analysis of four period mutants in Drosophila melanogaster encompassing extreme short, novel long, and unorthodox arrhythmic types. Genetics. 1998;149:165–178. doi: 10.1093/genetics/149.1.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harding R W, Turner R V. Photoregulation of the carotenoid biosynthetic pathways in albino and white collar mutants of Neurospora crassa. Plant Physiol. 1981;68:745–749. doi: 10.1104/pp.68.3.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hogenesch J B, Gu Y-Z, Jain S, Bradfield C A. The basic-helix-loop-helix-PAS orphan MOP3 forms transcriptionally active complexes with circadian and hypoxia factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5474–5479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishiura M, Kutsuna S, Aoki S, Iwasaki H, Anderson C R, Tanabe A, Golden S S, Johnson C H, Kondo T. Expression of a gene cluster kaiABC as a circadian feedback process in cyanobacteria. Science. 1998;281:1519–1523. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iwasaki H, Dunlap J C. Microbial circadian oscillatory systems in Neurospora and Synechococcus: models for cellular clocks. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3:189–196. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jin X, Shearman L P, Weaver D R, Zylka M J, de Vries G J, Reppert S M. A molecular mechanism regulating rhythmic output from the suprachiasmatic circadian clock. Cell. 1999;96:57–68. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80959-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawana M, Lee M, Quertermous E, Quertermous T. Cooperative interaction of GATA-2 and AP1 regulates transcription of the endothelin-1 gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4225–4231. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.King D, Zhao Y, Sangoram A, Wilsbacher L, Tanaka M, Antoch M, Steeves T, Vitaterna M, Kornhauser J, Lowrey P, Turek F, Takahashi J. Positional cloning of the mouse circadian Clock gene. Cell. 1997;89:641–653. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80245-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kondo T, Tsinoremas N, Golden S, Johnson C H, Kutsuna S, Ishiura M. Circadian clock mutants of cyanobacteria. Science. 1994;266:1233–1236. doi: 10.1126/science.7973706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Konopka R J, Pittendrigh C, Orr D. Reciprocal behavior associated with altered homeostasis and photosensitivity of Drosophila clock mutants. J Neurogenet. 1989;6:1–10. doi: 10.3109/01677068909107096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kudla B, Caddick M X, Langdon T, Martinez-Rossi N M, Bennett C F, Sibley S, Davies R W, Arst H N J. The regulatory gene areA mediating nitrogen metabolite repression in Aspergillus nidulans. Mutations affecting specificity of gene activation alter a loop residue of a putative zinc finger. EMBO J. 1990;9:1355–1364. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08250.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee C, Bae K, Edery I. The Drosophila CLOCK protein undergoes daily rhythms in abundance, phosphorylation, and interactions with the PER-TIM complex. Neuron. 1998;21:857–867. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80601-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee K, Loros J, Dunlap J. Interconnected feedback loops in the Neurospora circadian system. Science. 2000;289:107–110. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5476.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Linden H, Ballario P, Macino G. Blue light regulation in Neurospora crassa. Fungal Genet Biol. 1997;22:141–150. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1997.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Linden H, Macino G. White collar-2, a partner in blue-light signal transduction, controlling expression of light-regulated genes in Neurospora crassa. EMBO J. 1997;16:98–109. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.1.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Linden H, Rodriguez-Franco M, Macino G. Mutants of Neurospora crassa defective in regulation of blue light perception. Mol Gen Genet. 1997;254:111–118. doi: 10.1007/s004380050398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Y, Loros J J, Dunlap J C. Phosphorylation of the Neurospora clock protein FREQUENCY determines its degradation rate and strongly influences the period length of the circadian clock. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:234–239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.1.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43a.Liu Y, Garceau N, Loros J J, Dunlap J C. Thermally regulated translational control mediates aspects of circadian temperature responses in the Neurospora circadian clock. Cell. 1997;89:477–486. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80228-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43b.Liu Y, Merrow M, Loros J J, Dunlap J C. How temperature changes reset a circadian oscillator. Science. 1998;281:825–829. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5378.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loros J J. Time at the end of the millennium: the Neurospora clock. Curr Opin Microbiol. 1998;1:698–706. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(98)80118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loros J J, Dunlap J C. Genetic and molecular analysis of circadian rhythms in Neurospora. Annu Rev Physiol. 2001;63:757–794. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loros J J, Feldman J F. Loss of temperature compensation of circadian period length in the frq-9 mutant of Neurospora crassa. J Biol Rhythms. 1986;1:187–198. doi: 10.1177/074873048600100302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lowry P L, Shimomura K, Antoch M P, Yamazaki S, Zemenides P D, Ralph M R, Menaker M, Takahashi J S. Positional syntenic cloning and functional characterization of the mammalian circadian mutation tau. Science. 2000;288:483–491. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5465.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luo C, Loros J J, Dunlap J C. Nuclear localization is required for function of the essential clock protein FREQUENCY. EMBO J. 1998;17:1228–1235. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsumoto A, Tomioka K, Chiba Y, Tanimura T. timrit lengthens circadian period in a temperature-dependent manner through suppression of PERIOD protein cycling and nuclear localization. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4343–4354. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Merika M, Orkin S. Functional synergy and physical interactions of the erythroid transcription factor GATA-1 with the Kruppel family proteins SP1 and EKLF. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2437–2447. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.5.2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Omichinski J, Clore G, Schaad O, Felsenfeld G, Trainor C, Appella E, Stahl S, Gronenborn A. NMR structure of a specific DNA complex of Zn-containing DNA binding domain of GATA-1. Science. 1993;261:438–446. doi: 10.1126/science.8332909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Perkins D D, Radford A, Newmeyer D, Bjorkman M. Chromosomal loci of Neurospora crassa. Microbiol Rev. 1982;46:426–570. doi: 10.1128/mr.46.4.426-570.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pittendrigh C S. Temporal organization: reflections of a Darwinian clock-watcher. Annu Rev Physiol. 1993;55:17–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.55.030193.000313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ralph M R, Menaker M. A mutation of the circadian system in golden hamsters. Science. 1988;241:1225–1227. doi: 10.1126/science.3413487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roenneberg T, Taylor W. Automated recordings of bioluminescence with special reference to the analysis of circadian rhythms. Methods Enzymol. 2000;305:104–119. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)05481-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rosbash M, Allada R, Dembinska M, Guo W Q, Le M, Marrus S, Qian Z, Rutila J, Yaglom J, Zeng H. A Drosophila circadian clock. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1996;61:265–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruoff P, Vinsjevik M, Monnerjahn C, Rensing L. The Goodwin oscillator: on the importance of degradation reactions in the circadian clock. J Biol Rhythms. 1999;14:469–479. doi: 10.1177/074873099129001037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Russo V. Blue light induces circadian rhythms in the bd mutant of Neurospora: double mutants bd, wc-1 and bd, wc-2 are blind. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1988;2:59–65. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(88)85037-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rutila J E, Suri V, Le M, So W V, Rosbash M, Hall J C. CYCLE is a second bHLH-PAS clock protein essential for circadian rhythmicity and transcription of Drosophila period and timeless. Cell. 1998;93:805–813. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81441-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sambrook H, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Starich M, Wikstrom M, Schumacher S, Arst H, Jr, Gronenborn A, Clore G. The solution structure of the Leu22>Val mutant AREA DNA binding domain complexed with a TGATAG core element defines a role for hydrophobic packing in the determination of specificity. J Mol Biol. 1998;277:621–634. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Talora C, Franchii L, Linden H, Ballario P, Macino G. Role of a white collar-1-white collar-2 complex in blue-light signal transduction. EMBO J. 1999;18:4961–4968. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.4961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Teakle G, Gilmartin P. Two forms of type IV zinc-finger motif and their kingdom-specifc distribution between the flora, fauna and fungi. Trends Biochem. 1998;23(3):100–102. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tosini G, Menaker M. The tau mutation affects temperature compensation of hamster retinal circadiina oscillators. NeuroReport. 1998;9:1101–1105. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199804200-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tsai S-F, Martin D, Zon L, D'Andrea A, Wong G, Orkin S. Cloning of cDNA for the major DNA-binding protein of the erythroid lineage through expression in mammalian cells. Nature. 1989;339:446–451. doi: 10.1038/339446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vitaterna K W, King P Y, Chang A M, Kornhauser J M, Lowrey P L, McDonald J D, Dove W F, Pinto L H, Turek F W, Takahashi J S. Mutagenesis and mapping of a mouse gene, Clock, essential for circadian behavior. Science. 1994;264:719–725. doi: 10.1126/science.8171325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Young M W. The molecular control of circadian behavioral rhythms and their entrainment in Drosophila. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:135–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zatz M, editor. Circadian rhythms. Vol. 8. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1992. [Google Scholar]