Abstract

Cocaine craving, seeking, and relapse are mediated, in part, by cocaine-induced adaptive changes in the brain reward circuits. The nucleus accumbens (NAc) integrates and prioritizes different emotional and motivational inputs to the reward system by processing convergent glutamatergic projections from the medial prefrontal cortex, basolateral amygdala, ventral hippocampus, and other limbic and paralimbic brain regions. Medium spiny neurons (MSNs) are the principal projection neurons in the NAc, which can be divided into two major subpopulations, namely dopamine receptor D1- versus D2-expressing MSNs, with complementing roles in reward-associated behaviors. After cocaine experience, NAc MSNs exhibit complex and differential adaptations dependent on cocaine regimen, withdrawal time, cell type, location (NAc core versus shell), and related input and output projections, or any combination of these factors. Detailed characterization of these cellular adaptations has been greatly facilitated by the recent development of optogenetic/chemogenetic techniques combined with transgenic tools. In this review, we discuss such cell type- and projection-specific adaptations induced by cocaine experience. Specifically, (1) D1 and D2 NAc MSNs frequently exhibit differential adaptations in spinogenesis, glutamatergic receptor trafficking, and intrinsic membrane excitability, (2) cocaine experience differentially changes the synaptic transmission at different afferent projections onto NAc MSNs, (3) cocaine-induced NAc adaptations exhibit output specificity, e.g., being different at NAc-ventral pallidum vs. NAc-ventral tegmental area synapses, and (4) the input, output, subregion, and D1/D2 cell type may together determine cocaine-induced circuit plasticity in the NAc. In light of the projection and cell-type specificity, we also briefly discuss ensemble and circuit mechanisms contributing to cocaine craving and relapse after drug withdrawal.

Keywords: cocaine, silent synapse, accumbens, projection-specific, cell type-specific, adaptations

Introduction

In recent years, our quest for the neural mechanisms underlying substance use disorder (SUD) has been greatly empowered by two scientific advancements. Conceptually, the neuroadaptation theory identifies SUD as a chronic brain disease of learning and memory1–3, prompting the search for key forms of neural plasticity that are engaged in drug seeking and relapse. Technically, the development of research tools, particularly optogenetic/chemogenetic approaches combined with transgenic animals, has enabled projection- and cell type-specific understanding of drug-induced adaptations in unprecedented detail. Here, we will summarize the most relevant background literature, in order to facilitate a discussion of the projection- and cell type-specific adaptations induced by cocaine experience.

Anatomical connections of the nucleus accumbens in the context of cocaine seeking

Located at the ventral striatum, the nucleus accumbens (NAc) is a key hub within the mesolimbic reward circuit. It receives dopaminergic input from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and extensive convergent glutamatergic inputs from limbic and paralimbic brain regions, including the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), basolateral amygdala (BLA), ventral hippocampus (vHipp), paraventricular nucleus of the thalamus (PVT), and others4. The NAc projects to the ventral pallidum (VP), VTA, and other components of the basal ganglia and mesencephalon to regulate motor output and mesencephalic dopamine release4. These circuit features position the NAc as an interface bridging and prioritizing emotional and motivational arousals for behavioral output, thus regulating reward learning and goal-driven behaviors5–7. The behavioral role of the NAc in drug-related behaviors was initially revealed by early observations that disruption of NAc DA signaling compromises the acquisition of cocaine self-administration (SA)8, 9, and that NAc DA is important for the expression of amphetamine-induced locomotor sensitization10, 11 (rodent models see Box 1). Similarly, blocking glutamatergic transmission to the NAc compromises multiple forms of reinstated drug-seeking after withdrawal from drug SA, as well as the expression of psychomotor sensitization following repeated non-contingent drug procedures12, 13. However, excitotoxic lesion of the NAc core/shell does not entirely prevent the acquisition of cocaine SA14, suggesting that the NAc is not required for the establishment of operant responding, but rather regulates the conditioning of the responding by incorporating information pertaining to emotional and motivational salience. Taken together, the NAc stands as a critical interface of glutamatergic and dopaminergic signaling in regulating the development of drug-related behaviors.

Box 1: Rodent models of cocaine-induced behaviors.

A wide array of rodent models has been used to study drug seeking, relapse, and other SUD-related behaviors. Excellent in-depth reviews can be found elsewhere15–19. Broadly defined, the procedures can be categorized as non-contingent versus contingent models, with the latter frequently referred to as self-administration (SA). In a non-contingent model, cocaine is administered by the experimenter, usually through intraperitoneal (IP) or subcutaneous injections, and can therefore be considered passive exposure to drugs of abuse. Non-contingent administration can elicit behaviors such as locomotor sensitization and conditioned-place preference (CPP), the latter of which is often used to infer the rewarding effect of cocaine. SA paradigms can be categorized as limited versus extended access based on the daily session duration (e.g., 2, 6, or 12 hour) and the total number of sessions used in an experiment (e.g., 1-day, 1-week daily, 1-month daily, etc.). A third model, intermittent SA, mimics cycles of drug use by utilizing distinct drug- and no-drug-trials within a daily session. This model, while not discussed here, is reviewed elsewhere20. SA paradigms can employ fixed or progressive ratio reinforcement schedules, with progressive ratios multiplicatively increasing the required number of operant responses for a reward. The progressive ratio procedure tests how much the animal is willing to work to gain a reward and is thus often used to assess levels of motivation to obtain a drug15, 21. In humans, drug craving refers to an affective state of increased propensity to relapse17, 22–24. Though not directly measurable in rodents, drug craving can be inferred from the experimentally measurable parameter ‘drug seeking’ following SA25. An important form of drug seeking is induced by re-exposure to cues that are previously associated with the drug, thus called cue-induced drug seeking26. The degree of drug craving after withdrawal can therefore be reflected by comparing the intensities of cue-induced drug seeking (i.e., the number of drug-related operant responses) between animals or between different time points of the same animals after withdrawal27. Cue-induced drug seeking after withdrawal measured in the absence of extinction training (see below) often exhibits persistent and progressive intensification after withdrawal from drug SA, which is termed the incubation of drug craving17, 28, 29. On the other hand, drug seeking can be reduced by extinction training, during which operant responding no longer results in drug delivery. Extinction training is often performed in the absence of drug-associated cues, which preferentially disconnects the operant responding with drug seeking. After such extinction training, operant responding (i.e., drug seeking) can be reinstated upon re-exposure to conditioned cues, stress, or a drug primer to model drug relapse26. Thus, cue-induced reinstatement test differs from the above-mentioned “incubation” test by including an extinction training before reinstatement. While the extinction-reinstatement paradigm has contributed enormously to the SUD research, the extinction training component is not readily applicable to the human situation, thereby necessitating the development of new behavioral models with improved translatability20, 30. In response to this necessity, the ‘punishment-induced’ and ‘voluntary’ abstinence models have been developed, in which drug cessation is driven by punishment avoidance or the pursuit of an alternative reinforcer, both of which better reflect motivators of drug abstinence in humans18. These two models can be integrated with some other models mentioned above and create unique behavioral angles for future SUD research.

Role of NAc glutamatergic synapses

The NAc can be divided into anatomical-functional subregions, such as the core (Co) and shell (Sh). While sharing some similarities, the NAcCo and NAcSh often undergo different forms of adaptive changes and differentially contribute to the “motor” and “limbic” aspects of drug seeking14, 16, 22, 31. Both the NAcCo and NAcSh are composed of ~95% GABAergic medium spiny projecting neurons (MSNs), which can be largely sorted into two populations based on their predominant expression of either dopamine D1 or D2 receptors, with a potential third, small population expressing both receptor subtypes32–35. The remaining NAc neurons are non-glutamatergic interneurons36–40.

Lacking intrinsic pace-making mechanisms, action potential firing of NAc MSNs is driven by glutamatergic synaptic inputs. Based on early in vivo recordings and pharmaco-behavioral studies, it has been long speculated that cocaine-induced changes in the NAc glutamatergic transmission critically contribute to various aspects of drug-seeking behaviors12, 41, 42. This notion has been supported by numerous empirical results involving both the NAcSh and NAcCo. For example, in both NAcSh and NAcCo, MSNs often exhibit increased densities of dendritic spines suggestive of increased glutamatergic synapses after withdrawal from either non-contingent or contingent cocaine procedures, though details on NAcSh/Co differences and spine subcategories are not always consistent43–47. In the NAcSh MSNs, electrophysiological recordings combined with molecular tagging and imaging suggest de novo synaptogenesis following non-contingent cocaine exposure, producing “AMPA-silent” glutamatergic synapses (“silent synapses”)48, 49 (Box 2). Silent synapses have since been observed in NAcSh MSNs in neuronal ensembles that accompany behavioral sensitization in response to non-contingent cocaine50, 51, as well as following cocaine SA (limited-access) (for review see52). Moreover, after withdrawal from either non-contingent or contingent cocaine exposure, synaptic recruitment of AMPARs has been observed in NAcSh MSN synapses, upon which some of cocaine-generated silent synapses mature into fully functional synapses and contribute to the consolidation of cocaine-associated memories53–58. Furthermore, upon cue re-exposure after drug withdrawal, mature, AMPAR-containing, cocaine-generated synapses become temporarily re-silenced, followed by re-maturation several hours later, two synaptic states corresponding with the destabilization and reconsolidation of cocaine-associated memories59. Thus, by generating nascent synaptic contacts, cocaine experience may redefine the connectivity patterns of key glutamatergic projections to NAcSh MSNs, thereby remodeling NAc circuits to embed cocaine-associated memories52. In the NAcCo, upregulation of synaptic AMPARs also occurs after withdrawal but differs between non-contingent versus contingent cocaine regimens22. Following non-contingent exposure and 2–3 weeks of withdrawal, typical, calcium-impermeable AMPARs (CI-AMPARs) are upregulated. By contrast, following extended-access cocaine SA and long-term withdrawal (after day 25–35), atypical, calcium-permeable AMPARs (CP-AMPARs) are upregulated at overall NAcCo MSN synapses22, 60, 61 (but see CI-AMPARs recruitment at prelimbic PFC-to-NAcCo synapses54). The accumulation of CP-AMPARs at NAcCo synapses is negatively regulated by mGluR161–63, and dependent on protein synthesis64, though not necessarily matches with spine density changes47. Moreover, pharmacological inhibition of these receptors in the NAcCo decreases cue-induced cocaine seeking after long-term withdrawal from extended-access cocaine SA60. These and other results (for review see22, 31) highlight NAc glutamatergic synapses as key neuronal substrates through which cocaine experience produces persistent synaptic and circuit adaptations to promote drug seeking and pave the road for cell type- and projection-specific studies of drug-induced circuit adaptations.

Box 2: Silent synapses.

Silent synapses are glutamatergic synapses that possess NMDARs but lack functionally stable AMPARs65–68. These synapses are abundant during development but decline to low levels in the adult brain69. Following either non-contingent or contingent cocaine exposure, silent synapses, which resemble nascent synapses in the developing brain, are detected in NAcSh MSNs48, 49, 52–55. Although silent synapses are minimally activated near resting membrane potentials, their abundance in NMDARs, especially GluN2B-containing ones, make them excellent glutamate-depolarization coincidence detectors and a presumed substrate for long-term potentiation65, 67. Moreover, the subsequent maturation of silent synapses through AMPAR recruitment (allowing synaptic activation and conductance) re-organizes the functional connectivity of related neural circuits by bringing cocaine-induced adaptations “on-line”. The similarities between cocaine-induced silent synapses and nascent synapses led to the “rejuvenation hypothesis” of SUD – that exposure to drugs of abuse reopens developmental mechanisms at the molecular, cellular, and circuit levels to redevelop glutamatergic reward circuits, thus resulting in the durable, maladaptive alterations that underly SUD70, 71.

Glutamatergic synapses on D1 versus D2 MSNs

The availability of transgenic animals enabling genetic manipulation/marking of specific neuronal subpopulations72, 73 has provided extensive demonstrations of how cocaine-induced plasticity is differentially expressed in NAc D1 and D2 MSNs31, 33, 34, 74, 75. NAc D1 and D2 MSNs form divergent yet partially overlapping connections with downstream brain regions76–78. In behaving animals performing reward-seeking tasks, NAc D1 and D2 MSNs often exhibit differential activity patterns79, and stimulation (or suppression) of D1 versus D2 MSNs can result in distinct, often antagonistic, regulation over reward-associated behaviors80–82. A note of caution is that the “antagonistic” roles of D1 versus D2 MSNs in regulating reward-associated behaviors deduced from experimenter-imposed activation or suppression of selective neuronal populations may be different from the natural in vivo situation83, where D1 and D2 MSNs also exhibit cooperative roles, as demonstrated in the dorsal striatum84, and are differentially, but not antagonistically, involved in learning-associated cellular plasticity85, 86.

Non-contingent cocaine exposure:

One week following a single i.p. injection of cocaine (20 mg/kg), NAcSh D1, but not D2, MSNs exhibit increased miniature (m) EPSC amplitude and frequency (of postsynaptic origin), accompanied by a reduced capacity for LTP induction, suggesting cocaine-induced AMPAR insertions selectively in NAcSh D1 MSNs87. Furthermore, reversing this postsynaptic potentiation in cocaine-exposed mice abolishes the expression of cocaine-induced psychomotor sensitization87. Similarly, after 5-day non-contingent cocaine exposure (15 mg/kg/injection), NAcSh D1, but not D2, MSNs exhibit increased spine densities74, 88, which is accompanied by an increase in the frequency of mEPSCs in D1 versus a decrease in D2 MSNs. On the other hand, the membrane excitability of NAcSh D1, but not D2, MSNs is decreased74. Furthermore, after ~4 weeks of non-contingent exposure to high-dose (30 mg/kg) cocaine, densities of dendritic spines exhibit a fast-onset and sustained increase in both NAcCo and NAcSh D1 MSNs75, while in D2 MSNs, the increase is transient and disappears by withdrawal day 3075. Taken together, these results suggest that spine densities and likely numbers of excitatory synapses on D1 MSNs are upregulated by either short- or long-term exposure to cocaine, while these parameters are only changed in D2 MSNs after prolonged and/or high-dose cocaine exposure. These non-contingent procedure-related results prompt the exploration of cell type-specific adaptations after contingent exposure to cocaine.

Cocaine SA:

There have been limited studies differentiating NAc D1 versus D2 MSNs in response to cocaine SA with bulk assessment of glutamatergic inputs. In the NAcSh, D1 MSNs preferentially exhibit a postsynaptic potentiation at glutamatergic synapses following 1-month withdrawal from an initial 5-day 2-h daily cocaine SA with a fixed ratio (FR) schedule 1 and subsequent 5-day SA with FR289. Furthermore, NAcSh D1 MSNs are preferentially enriched with CP-AMPARs following 10 days of short- or extended access, regular dose SA, with D2 MSNs only exhibiting similar potentiation after a high-dose, extended-access regiment57. In the NAcCo, postsynaptic potentiation occurs preferentially at D1 over D2 MSN synapses after a chronic cocaine SA procedure (6–7 weeks of 2-h daily sessions, at least 17 sessions), except in a subset of mice in which a greater potentiation of D2 MSN synapses is observed that correlates with higher resilience to compulsive cocaine use82.

Re-exposure to drug-associated cues after SA:

Following long-term withdrawal (~45 days) from an overnight session and 5-day 2-h cocaine SA, re-exposure to cocaine-associated cues induces a transient de-potentiation (“re-silencing”) then recovery of cocaine-generated synapses in the NAcSh, which is postulated to mediate the destabilization and reconsolidation of cocaine-associated memories59. However, the cell-type specificity was not determined in this study. Using a different paradigm, it is shown that 2–3 weeks after withdrawal from 10-day cocaine SA, NAcCo D1 and D2 MSNs do not show changes in AMPAR/NMDAR ratios. However, upon re-exposure to cocaine-associated discrete or contextual cues at this withdrawal time (without extinction training), the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio of NAcCo D1 (but not D2) MSNs is transiently increased. By contrast, in mice that undergo extinction training, re-exposure to the extinguished context selectively increased the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio in NAcCo D2 (but not D1) MSNs and decreased cue-induced cocaine-seeking, implicating this D2 MSN-specific adaptation in cocaine-refraining behavior. Furthermore, in mice that undergo extinction training prior to re-exposure to cocaine-associated discrete cues, both NAcCo D1 and D2 MSNs show increased AMPAR/NMDAR ratio, suggesting that cue-induced relapse is effectively balanced by the relative activation patterns of these two neuronal populations90. This is partially supported by results from the rat NAcSh, wherein there is a transient increase in the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio during drug-refraining, presumably driven by D2 MSNs91. However, the same paper found no significant differences in the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio of D1 and D2 NAcSh MSNs in mice, although there was increased innervation of D2 MSNs relative to D191. Thus, these results suggest that differential potentiation of NAcCo D1 and D2 MSN excitatory inputs in response to contextual or discrete cocaine-associated cues regulates the balance between cocaine seeking or refraining behaviors. The combined discrepancies of NAc D1 and D2 MSNs and the observed subregion differences thereby prompts a consideration of cocaine-induced changes in projection- and cell type-specific manners.

Projection- and cell type-specific changes on NAc glutamatergic inputs

Early in vivo multi-unit recordings provide glimpses of neuronal activity patterns in the NAc during cocaine SA and after withdrawal. Specifically, select populations of NAcCo/ventral striatal neurons exhibit a phasic increase in firing correlated with the initiation and maintenance of cocaine SA, as well as an increase in firing upon re-exposure to cocaine-associated cues after drug withdrawal92–94. These ensemble-like activities hint at the possibility that NAc MSNs are functionally organized, may be preferentially driven by different glutamatergic projections at different behavioral moments, and likely undergo cocaine-induced changes. These initial results establish strong premises for studying projection-specific control of cocaine-induced neural plasticity in the NAc.

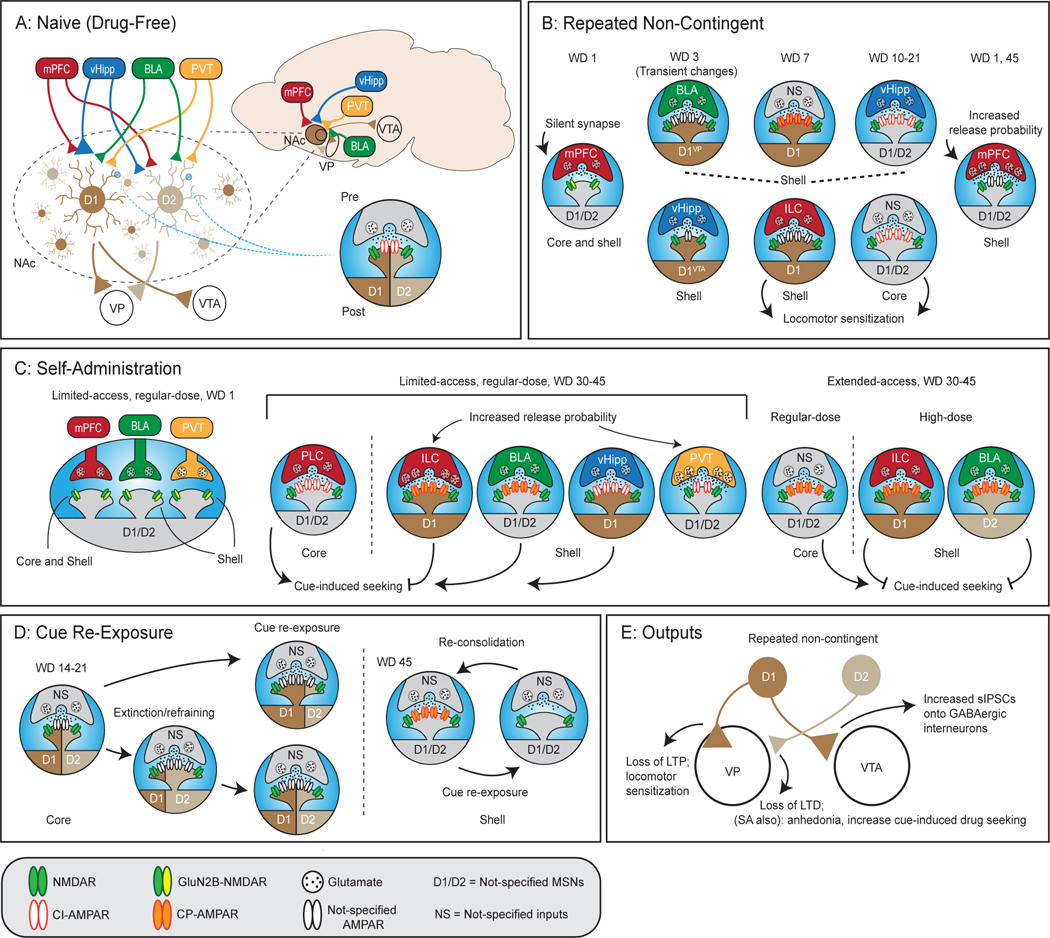

Glutamatergic inputs from various cortical and subcortical regions differentially innervate NAc sub-regions95–97. At the cellular level, these projections converge on individual MSNs, often on the same segments of dendrites98–102. Here, we focus on the mPFC, BLA, vHipp, and PVT projections for cocaine-induced changes (Figure 1) and their behavioral correlates.

Figure 1.

Cocaine-induced projection- and cell type-specific neural adaptations in the NAc circuit. A: Schematic diagram of the NAc circuit. Prior to cocaine exposure, glutamatergic inputs are largely unbiased between D1 and D2 MSNs, with the exception of vHipp inputs which are stronger at D1 than D2 MSN-synapses88, 126. The majority of glutamatergic synapses onto D1 or D2 MSNs contain CI-AMPARs. B: Shortly after repeated non-contingent cocaine exposure, silent synapses are detected in the mixed populations of NAc MSNs48, 49 as well as at mPFC inputs54. At withdrawal day ~3, an increase of BLA-to-D1 MSNVP transmission and a decrease of vHipp-to-D1VTA transmission are observed in the NAcSh, both of which are likely transient changes88, 126. At withdrawal day ~7 following a single injection protocol, an LTP-like potentiation of IL-to-D1 synapses occurs in the NAcSh, which contributes to the development of locomotor sensitization87. At around the same withdrawal time, one study found selective CP-AMPAR potentiation in D1 MSNs when assessed in bulk57. At withdrawal day 10–14, vHipp-to-NAcSh synapses show increased AMPAR transmission mediated by CI-AMPARs96. Behavioral sensitization on withdrawal day 21 is associated with increased surface expression of GluA1 and GluA2/3 (thus likely CI-AMPARs) in the core22, 212. On both withdrawal day 1 and 45, an increase in presynaptic glutamate release probability is observed at mPFC-to-NAcSh synapses114. C: Cocaine SA results in the transient formation of GluN2B-NMDAR-rich “silent synapses” in the core and shell, as examined at mPFC, BLA, and PVT projections53, 54, 148. Cocaine-induced silent synapses undergoing AMPAR-insertion after withdrawal are likely to be found predominantly on D1 MSNs, with D2 MSNs potentially undergoing a brief or incomplete synapse generation during early withdrawal55, 57, 74, 89. Silent synapses undergo maturation in a projection specific manner: PL-to-NAcCo synapses undergo CI-AMPAR insertion, which promotes incubation of cocaine craving. IL-to-NAcSh synapses display CP-AMPAR insertion, most likely on D1 MSNs, which reduces incubation54, 55 (but see89). Likewise, BLA-to-NAc silent synapse maturation with CP-AMPARs has been demonstrated in rats following limited-access SA and long-term withdrawal, which contributes to incubated cocaine craving53. vHipp-to-NAcSh synapses undergo potentiation via the selective insertion of CI-AMPARs in D1 MSNs, and potentiation of this projection facilitates cue-induced cocaine seeking89. Both IL-to-NAcSh and PVT-to-NAcSh synapses show increased glutamate release probability after cocaine SA and long-term withdrawal114, 148. Following extended-access to regular-dose cocaine SA and long-term withdrawal, CP-AMPARs are upregulated in the NAcCo MSNs through mGluR1-regulated, protein synthesis-dependent mechanisms, which critically mediates incubation of cocaine craving22, 60–64. Following extended-access to high-dose cocaine SA and long-term withdrawal, selective potentiation of mPFC-to-NAcSh D1(but not D2) MSNs is detected, likely mediated by synaptic insertion of CP-AMPARs57. By contrast, following the same cocaine regimen and withdrawal, CP-AMPARs are inserted selectively at BLA-D2 MSN synapses, which concurs with incubation and is thought to be related to negative affect and aversion learning57. D: Re-exposure to cocaine-associated cues induces additional AMPAR plasticity. For instance, cue re-exposure after withdrawal preferentially potentiates D1 MSNs in the NAcCo, whereas extinction training prior to cue re-exposure preferentially strengthens D2 MSNs90. In the NAcSh, cue re-exposure temporarily re-silences cocaine-generated synapses, which can be followed by a re-maturation process accompanying the reconsolidation of cocaine-cue associations59. E: Downstream at NAc outputs, VTA GABAergic neurons that receive from NAc D1 MSNs show increased spontaneous IPSCs following repeated non-contingent cocaine, disinhibiting dopaminergic neural activity165; D1 MSN-to-VP transmission is strengthened following repeated non-contingent cocaine and withdrawal, while D2 MSN-to-VP transmission is weakened (and/or loses plasticity following non-contingent cocaine or SA and extinction)169, 170. Thus, the outcomes of these adaptive changes are potential shifts in the inhibitory network balance established by D1 and D2 MSNs, which are shaped at the NAc inputs, as well as at downstream outputs onto the VP and VTA. PLC, prelimbic PFC; ILC, infralimbic PFC; WD, withdrawal day.

mPFC-to-NAc:

Corticostriatal projections from the mPFC are crucial for the generation of adaptive strategies in reward seeking by regulating reward anticipation, reward evaluation, and risk assessment6, 103–105. Extensive evidence suggests that the glutamatergic projection from the prelimbic mPFC (PL) to the NAcCo functions to promote cue- and drug priming-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking after extinction of SA106–108, whereas the infralimbic mPFC (IL) projection to the NAcSh functions to suppress cocaine seeking during extinction training, inhibit cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking, and facilitate the consolidation of memories related to extinction learning109–113.

Non-contingent cocaine (15–20 mg/kg/injection):

After 5 days of non-contingent cocaine administration, mPFC (presumably IL)-to-NAcSh synapses exhibit persistently increased presynaptic release probability over the 45-day withdrawal period114. Although no postsynaptic changes were detected at IL-to-NAcSh synapses 10–14 days after 5-day non-contingent cocaine exposure in one study96, a single injection of cocaine leads to the occlusion of LTP in D1 MSNs in both NAcCo and NAcSh at one week, but not a month, after administration87 as well as a facilitation of NMDAR-dependent LTD at IL-to-NAcSh synapses, suggesting cocaine-induced increases in AMPAR transmission within this projection. This is further shown to contribute to sensitized locomotor responses during early drug withdrawal87.

Limited-access cocaine SA:

The limited-access cocaine SA training typically contains an extended overnight (O/N) session of unlimited access followed by ~5 days of 2-hr daily SA (0.75 mg/kg/infusion). After either short-term (1-day) or long-term (45-day) withdrawal from this training procedure, IL-to-NAcSh synapses exhibit increased presynaptic release probability114. Moreover, AMPAR upregulation-mediated postsynaptic potentiation occurs at both PL-to-NAcCo and IL-to-NAcSh synapses following long-term withdrawal from a similar cocaine regimen, though with differential molecular mechanisms and contrasting behavioral consequences54. After short-term withdrawal from cocaine SA, AMPAR-silent synapses are detected within PFC-to-NAc projections54. After cocaine withdrawal, some of the PL-to-NAcCo silent synapses mature by recruiting predominantly CI-AMPARs, whereas IL-to-NAcSh silent synapses mature by recruiting predominantly CP-AMPARs54. After long-term withdrawal, reversing the maturation of PL-to-NAcCo silent synapses decreases cue-induced cocaine seeking, whereas reversing the maturation of IL-to-NAcSh silent synapses induces the opposite effect54. Thus, by generating silent synapses, cocaine experience simultaneously remodels both the PL-to-NAcCo and IL-to-NAcSh projections, resulting in opposing behavioral consequences. Although the above rat studies do not distinguish D1 versus D2 MSNs, in mice following long-term withdrawal from a 10-day mixed FR1/FR2 schedule SA paradigm, mPFC-to-NAcSh synapses are selectively potentiated in D1 MSNs by CP-AMPAR insertions89. Reversing this cocaine-induced adaptation increases the rate of incorrect operant responding during cue-induced cocaine seeking, suggesting an impaired cue-cocaine association89.

Extended-access, high-dose cocaine SA:

After a month of withdrawal from 10 days of 6 hr daily sessions with a high cocaine dosage (1.5 mg/kg/infusion), selective postsynaptic potentiation of mPFC-to-NAcSh D1(but not D2) MSNs is detected, likely mediated by synaptic insertion of CP-AMPARs57. This conceivably shifts the balance of the mPFC inputs toward stronger drive onto D1 MSNs, as compared to the drug-naïve animals, where the overall activation of mPFC-to-NAc inputs evokes largely equal postsynaptic responses in D1 versus D2 MSNs in both NAcCo and NAcSh88, 115. After high-dose SA paradigms, the magnitude of CP-AMPAR upregulation is positively correlated with the level of incubated cocaine seeking57.

BLA-to-NAc:

The amygdala is an evolutionarily conserved brain region that encodes and relays information pertaining to cues associated with emotional valence, including cocaine-associated cues116, 117. The BLA-to-NAc projection may impose either positive or negative regulation of reward-elicited behaviors118–122, and plays a crucial role in cue-induced cocaine seeking123. A population of NAcCo MSNs exhibits increased activities upon re-exposure to the cues that are previously associated with reward consumption, and formation of this MSN response requires excitation of BLA neurons in conjunction with NAcCo dopamine signaling during the cue-reward training124. Furthermore, successive excitation of the BLA-to-NAcCo projection increases this cue-induced MSN response and facilitates reward seeking124. After extinction from 12 days cocaine SA, optogenetic inhibition of BLA-to-NAcCo transmission decreases cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking125. These results implicate the BLA-to-NAc projection in cue-conditioned reward and cocaine seeking, and raise the question of how this projection interacts with MSNs in a cell type-specific manner.

When assessed in bulk using optogenetic stimulation of populational BLA fibers within the NAc, the synaptic weights of BLA inputs to NAcSh D1 and D2 MSNs appear unbiased in naïve mice88, 126. However, these results do not exclude the possibility of preferential innervation of D1 versus D2 MSNs by individual BLA neurons, which has yet to be explored.

Non-contingent cocaine (15 mg/kg/injection):

In contrast to the mPFC projection, BLA-to-NAcSh synapses do not exhibit changes in presynaptic release probability following short- (1-day) or long-term (45-day) withdrawal from 5-day non-contingent cocaine exposure114. Postsynaptically, the overall AMPAR/NMDAR ratio at BLA-to-NAcSh synapses also remains constant after ~2 weeks of withdrawal from 5-day non-contingent cocaine exposure96. However, the relative innervation of NAcSh D1 versus D2 MSNs by BLA projections appears to be increased after short-term withdrawal from 5-day non-contingent cocaine exposure88, 126. Specifically, after 3 days withdrawal from 5-day non-contingent cocaine exposure, the BLA-to-D1 MSN transmission in the NAcSh is preferentially enhanced, accompanied by increases in the frequency of miniature EPSCs and overall density of dendritic spines on D1, but not D2, MSNs, suggesting selective strengthening of BLA-to-D1 MSN transmission88. Furthermore, D1 MSNs that exhibit potentiated BLA-to-NAcSh transmission are preferentially those that project to the VP in relation to those that project to the VTA126, hinting at a projection-specific mechanism that warrants further exploration.

Limited-access cocaine SA:

The general presynaptic properties of BLA-to-NAcSh synapses are not altered after either short- or long-term withdrawal from O/N+5-day SA or non-contingent administration of cocaine114. However, a silent synapse-mediated postsynaptic adaptation at BLA-to-MSN synapses is detected in rats after short-term withdrawal from O/N+5-day cocaine SA53. In mice, while this particular adaptation has not been examined, the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio at BLA-to-D1 MSNs in the NAcSh is not changed after withdrawal from a 10-day FR1/FR2 mixed limited-access SA89. In rats, CP-AMPARs are inserted to cocaine-generated silent synapses within the BLA-to-NAcSh projection after long-term withdrawal from O/N+5-day cocaine SA, indicating that at least a portion of BLA-to-NAcSh synapses, located either on D1 or D2 MSNs, are potentiated53. Furthermore, an in vivo optogenetic LTD protocol that preferentially removes CP-AMPARs from potentiated BLA-to-NAcSh synapses attenuates cue-induced cocaine seeking after cocaine withdrawal53, 127. It remains to be determined whether this adaptation is cell-type specific.

Extended-access or high-dose cocaine SA:

Following 10 days of 6-hr daily regular-dose cocaine SA (0.75mg/kg/infusion) and long-term (>40-day) withdrawal, local field potentials recorded in the NAcCo in response to BLA stimulation (40 Hz trains) are increased, to which either a potentiation of the BLA-to-NAcCo transmission or alterations in local GABAergic inhibitory circuits may contribute128. In addition, following high-dose, extended cocaine SA (1.5 mg/kg/infusion, 6-hr daily for 10 days) and long-term (1 month) withdrawal, CP-AMPAR insertion at BLA-to-NAcSh synapses is observed at D2, but not D1, MSN synapses in mice57. Such a D2 MSN-selective effect does not occur after SA of relatively low doses of cocaine89, suggesting the intensity of drug experience as a key factor in determining cell type-specific adaptations. It is speculated that potentiation of BLA-to-NAcSh D2 MSN projection may facilitate aversion learning57.

vHipp-to-NAc:

The vHipp is a key brain region that encodes spatial information related to stress and reward, and its projection to the NAc is important for context-induced reward seeking, reward-associated evaluations, and other behaviors129–135. In vivo optogenetic stimulation or suppression of vHipp-to-NAcSh synapses during non-contingent administration enhances or reduces cocaine-induced locomotor activities, respectively96.

The vHipp projection predominately innervates the medial shell of the NAc4, 96. In drug-naïve mice, the vHipp-to-NAcSh projection forms more synaptic connections onto D1 MSNs compared to presumed D2 MSNs88, 126. Furthermore, among all D1 MSNs, the subpopulation of D1 MSNs that project to the VTA (D1 MSNVTA) receive more abundant vHipp inputs compared to those D1 MSNs that project to the VP (D1 MSNVP)126.

Non-contingent cocaine (15 mg/kg/injection):

A weakening of vHipp-to-NAcSh synapses is initially detected in NAcSh D1 MSNs after 1- or 3-day withdrawal from non-contingent cocaine exposure, primarily due to a selective decrease in vHipp-to-D1 MSNVTA innervation88, 126. By contrast, after 10–14 days of withdrawal from 5-day non-contingent cocaine exposure, an increased AMPAR/NMDAR ratio is detected at D1 MSN synapses within the vHipp-to-NAcSh projection, suggesting a postsynaptic potentiation96, while the downstream targets of these D1 MSNs are not determined. This potentiation is not associated with changes in the rectification index of AMPAR EPSCs, thus likely mediated by upregulation of synaptic CI-AMPARs96. These potentially sequential changes suggest dynamic states of these synapses along the proceeding of drug withdrawal.

Limited-access cocaine SA:

After 30 days of withdrawal from 10-day, 2-hr daily (FR1-FR2) cocaine SA (0.75 mg/kg/infusion), an increase in the AMPAR/NMDAR ratio is observed at vHipp-to-NAcSh D1 MSN (but not D2 MSN) synapses89. Similarly, this potentiation is not associated with changes in the rectification index of AMPAR EPSCs and is therefore likely mediated by synaptic upregulation of CI-AMPARs89. Moreover, optogenetically inducing LTD to reverse cocaine SA-induced strengthening of vHipp-to-NAcSh synapses after drug withdrawal reduces cue-induced cocaine seeking89.

Taken together, the vHipp-to-NAcSh projection undergoes a range of dynamic adaptations with projection and cell-type specificity, likely dependent on the cocaine regimen used and withdrawal time.

PVT-to-NAc:

The thalamic projections to the NAc have been increasingly recognized for their roles in goal-directed behaviors, including drug seeking (for a comprehensive review see136). The PVT sends extensive glutamatergic projections to the NAcSh, which converge on MSNs with other excitatory synapses or dopaminergic terminals from the midbrain137–141, positioning this projection as a potential regulator of cue-associated behaviors such as drug seeking136, 142–144. Specific to cocaine-elicited behaviors, inactivation of the PVT reduces the development of cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization145, abolishes the expression of cocaine CPP146 and attenuates cocaine-primed reinstatement of drug-seeking following extinction of cocaine SA147, revealing its critical role in regulating cocaine-elicited behaviors. Selective ablation of PVT-NAcSh synaptic transmission slightly decreases the acquisition of cocaine SA without affecting incubated cocaine craving at later withdrawal times148. Results from morphine experiments suggest that the PVT-NAcSh D2 MSN pathway contributes to the negative salience associated with opiate withdrawal144. Whether the PVT-NAcSh projection plays a similar role in cocaine withdrawal symptomology has yet to be determined.

There is limited research on whether and how the PVT-NAcSh projection is altered following cocaine exposure. A single non-contingent injection of cocaine increases Fos protein expression in the PVT149, as does cue re-exposure following extinction from cocaine SA150, 151. Following O/N+5-day limited-access cocaine SA (0.75 mg/kg/infusion), an increased level of silent synapses in the PVT-NAcSh projection is detected, which returns to basal levels by withdrawal day 45. At withdrawal day 45, these synapses exhibit characteristics of CI-AMPARs, and AMPAR/NMDAR ratio is similar to that of cocaine naïve animals148. Furthermore, 5-day cocaine SA increases the release probability at PVT-NAcSh synapses, tested on withdrawal days 1 and 45148. These results suggest a mix of transient and persistent alterations in PVT-NAcSh glutamatergic transmission following cocaine SA. The cell-type specificity as well as the behavioral consequences of these changes remain to be determined.

From silent synapses to projection- and cell type-specific adaptations

AMPAR-silent, NMDAR-containing synapses, often simply referred to as silent synapses (Box 2), are highly abundant in the developing brain, but decline to low levels after development69. They are thought to be immature, nascent glutamatergic synapses that participate in the initial formation of the neural network. As development progresses, some silent synapses mature by recruiting AMPARs and consolidate the established neural circuits, while others are eliminated as a process of circuit refinement67, 68. In the adult NAcSh, levels of silent synapses are increased after 1-day withdrawal from 5 days of either non-contingent exposure or SA of cocaine48, 53, 54. Cocaine-generated silent synapses exhibit strikingly common cellular features shared with silent synapses in the newborn brain48, 56, 152. Recent results demonstrate that after cocaine SA, an astrocytic signaling pathway that mediates synaptogenesis during development is utilized as a mechanism in the generation of silent synapse in the NAcSh58. These findings support the hypothesis that through utilization of developmental mechanisms and synaptogenesis, cocaine experiences create new connectivity patterns within NAc circuits, which underlie cocaine memories52, 70. During development, only a portion of newborn synapses mature and are incorporated in the neural circuits, while others are pruned away153. A similar scenario might happen to cocaine-generated silent synapses such that they are generated throughout afferent projections in a relatively nonspecific manner, while their maturation and the concurring synapse elimination constitute a refining process for projection and/or cell-type specificity. These speculations predict a permissive role of silent synapses in remodeling and refining NAc circuits during encoding and expression of cocaine-associated memories.

After 1-day withdrawal from 5-day non-contingent cocaine exposure, high levels of silent synapses are preferentially generated in NAcSh D1, but not D2, MSNs55. An acute molecular adaptation of the NAc in response to cocaine exposure is an increase of CREB activity154. NAcSh levels of silent synapses start to increase as early as after 3 days of cocaine exposure, an effect requiring acute elevation of CREB activities48, 56. On the other hand, repeated cocaine exposure and withdrawal induces an accumulation of ΔFosB in NAc MSNs155. Mimicking this effect by overexpression of ΔFosB leads to opposing synaptic changes and spine alterations suggestive of an increase versus decrease in silent synapse levels in the NAcSh D1 versus D2 MSNs, respectively156. Compared to CREB, Δ FosB accumulation exhibits a slower time course over withdrawal periods157, suggesting that ΔFosB-mediated and other transcriptional pathway may preferentially participate in NAc circuit remodeling after prolonged cocaine exposure and withdrawal, contributing to the persistent increase of glutamatergic transmission to NAc D1 MSNs158.

After withdrawal from cocaine, a portion of NAc silent synapses mature by recruiting either CI-AMPARs or CP-AMPARs in a projection-specific manner53, 54, 148. As such, multiple inputs that converge onto NAc MSNs undergo differential silent synapse-mediated remodeling, with CP-AMPAR insertion at BLA- or IL-to-NAc synapses and CI-AMPAR insertion at PL- or vHipp-to-NAc synapses53, 54, 89. If occurring on the same MSNs, these differential maturation processes are expected to involve different molecular mechanisms, two possibilities being the activity-dependent versus constitutive insertion of AMPARs. In the developing hippocampus, strong synaptic activities, such as LTP conditioning, induce unsilencing/maturation of silent synapses, mediated by insertion of CP-AMPARs159. On the other hand, AMPARs that are constitutively inserted to synapses during metabolic turnover are largely CI-AMPARs160. Furthermore, non-contingent versus contingent cocaine experience may also contribute to the differential insertion of CP-AMPARs161. Thus, the activity states of different NAc afferent projections in response to specific cocaine experiences may trigger different machineries for AMPAR insertions. In addition, the synaptic stability of CP-AMPARs in the NAcCo MSNs is critically regulated by the tonic activity of mGluR1 signaling63, 89. It is also possible that silent synapses within different NAc projections dwell in different local tones of mGluR1 signaling162, 163, resulting in receptor subtype-selective insertions and maintenance. Compared to CI-AMPARs, insertion of CP-AMPARs at synapses not only increases AMPAR transmission, but also enhances synaptic Ca2+ conductance at resting membrane potentials, sometimes enacting new rules for synaptic plasticity, as demonstrated in the VTA164. Equipped with CP-AMPARs after cocaine withdrawal, matured silent synapses may not only change the connectivity pattern of NAc circuits, but also how information flows through these circuits.

NAc D1 and D2 MSNs output-specific changes

Cocaine-induced cellular adaptations in NAc MSNs are ultimately conveyed through GABAergic outputs to downstream targets, including the VTA, substantia nigra (SN), and VP, where another set of cocaine-induced changes occur. NAc-to-VTA/SN projections are predominantly composed of D1 MSNs, whereas both D1 and D2 MSNs project to the VP with further differentiation at the target cell types34, 76, 77. Currently, there is ongoing anatomical debate as to what extent the D1 MSN projection to the VP arises from axonal bifurcation versus a separate D1 MSN population34, 76, 78, 126.

Non-contingent cocaine (15–20 mg/kg/infusion):

Within the D1 MSN-to-VTA projection, 5 days of non-contingent cocaine exposure results in an increase in spontaneous IPSCs in postsynaptic VTA GABAergic neurons after 1-day withdrawal, an effect that may favor reduced inhibition of dopaminergic neurons and increased dopamine release in the NAc165. D1 MSNs also synapse directly onto VTA DA neurons166, 167, although the role of this projection has not been selectively examined in cocaine models168. Within the NAcSh-to-ventromedial (vm) VP projection, 5-day non-contingent cocaine administration increases D1 MSN-to-vmVP synaptic transmission while simultaneously decreasing D2 MSN-to-vmVP transmission on withdrawal day 10. These changes occlude the induction of LTP at D1 MSN-to-vmVP synapses and LTD at D2 MSN-to-vmVP synapses169, suggesting shared mechanisms between experience-dependent synaptic plasticity and cocaine-induced synaptic changes. Furthermore, the differential adaptations in NAcSh D1 versus D2 MSN-to-vmVP synapses mediate different aspects of cocaine-elicited behaviors. Whereas potentiation of NAcSh D1 MSN-to-vmVP transmission drives cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization, depression of NAcSh D2 MSNs-to-vmVP transmission impairs hedonic (sucrose) reward seeking, tested 10 days after cocaine cessation169.

Limited-access cocaine SA and reinstatement:

Following cocaine SA (2 h/day over 10–15 days; 0.75 mg/kg/infusion) and extinction, LTD at NAcCo D2 MSN-to-dorsolateral VP synapses is occluded, suggesting suppression of this projection, which leads to the facilitation of cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking170. Although cocaine-induced changes at NAcCo D1 MSN-to-VP synapses have not been examined, following the same cocaine SA and extinction procedure, chemogenetic inhibition of the NAcCo D1 MSN-to-VP projection reduces cue- as well as drug-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking76. By contrast, inhibiting the NAcCo D1 MSN-to-SN projection does not affect reinstatement76. Further complexity is added to the NAc-to-VP projections in that NAcCo D1 versus D2 MSNs exhibit overlapping but differential innervation of VP glutamatergic, GABAergic, and enkephalinergic neurons, which then impose distinct impacts on cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking after extinction77. Whether and how cocaine SA, extinction, and cue re-exposure induce differential neural adaptations in these functionally opposing sub-circuits remain to be determined.

NAc interneuron-specific changes

Though NAc interneurons comprise but a small fraction of the total neuronal population, they powerfully influence dopaminergic, glutamatergic, and GABAergic transmission in the NAc31, 37, 40. Based on genetic and electrophysiological characteristics, NAc GABAergic interneurons can be largely categorized into two heterogenous classes, fast-spiking interneurons (FSIs) expressing parvalbumin and/or CB1 receptors, and low-threshold spiking interneurons expressing a combination of somatostatin, neuropeptide Y, and neuronal nitric oxide synthase, often referred to as SST-NPY-nNOS interneurons (SSTIs)37. The NAc also contains a population of large, tonically active cholinergic interneurons (CINs)31. While an increasing number of interneuron subtypes have been discovered in the dorsal striatum, it has yet to be determined if these neuronal types are mirrored in the NAc38, 39. Here we focus on cholinergic and GABAergic interneurons, which undergo differential adaptive changes after cocaine experience31, 39, 40, 171.

Cholinergic interneurons:

CINs provide an intrinsic source of cholinergic innervation within the NAc172. Through a widely distributed and rich variety of receptors, CINs regulate many glutamatergic, GABAergic, and dopaminergic transmissions in the NAc, through which they critically influence the processing of reward, satiation, aversion, and other affective responses7, 171, 173, 174. Our understanding of CINs in cocaine-elicited behaviors has been greatly facilitated by the availability of optogenetic tools. For example, optogenetically inhibiting CINs in the NAcCo/Sh during cocaine CPP training slows down the acquisition of cocaine CPP175. Moreover, after cocaine CPP is established and during initial extinction training, optogenetic activation of medial NAc CINs enhances the extinction of cocaine CPP without affecting food CPP, while inhibiting NAc CINs suppresses the extinction of cocaine CPP176. These roles of NAc CINs in cocaine-elicited behaviors as revealed in optogenetics studies are not entirely consistent with results from ablation studies, where bilateral ablation of NAcCo/Sh CINs augments locomotor responses to cocaine and decreases the dose threshold for inducing cocaine CPP177. These results, taken together, suggest a complex and, possibly, dynamic role of NAc CINs in behavioral responses induced by acute cocaine administration.

NAcSh CINs are directly responsive to cocaine to increase spontaneous firing upon cocaine perfusion in brain slices175. Moreover, increased levels of acetylcholine (ACh) are observed in both the NAcSh and Co following in vivo intra-NAc infusion of cocaine178. Likewise, ACh levels increase following low-dose cocaine SA, with higher levels and longer-lasting effects being observed in SA groups compared to the yoked controls179. Following a 1-hour cocaine SA session, the number of Fos-expressing NAcSh CINs is increased, and this increase is positively correlated with the amount of cocaine intake during SA180. It is not known, however, whether these cocaine-elicited responses may lead to longer-term adaptations in the NAc cholinergic system. Nonetheless, NAc CIN activity modulates long-term plasticity of glutamatergic transmission to NAc MSNs181, 182, which may impose long-term modulation of NAc activity after cocaine experience. Remarkably, strong activation of NAc D1 MSNs, which likely occurs following cocaine experience, leads to long-term potentiation of AMPAR transmission to D2 MSNs through recruiting local CIN activity182. Though speculative, these effects of CINs may serve as part of the mechanisms by which high-dose and/or chronic cocaine exposure induces potentiation of glutamatergic transmission to NAc D2 MSNs57, 82.

A sustained increase in NAc levels of ACh persists after withdrawal from nicotine, morphine, or alcohol, which may contribute to certain withdrawal symptoms183. While levels of NAc ACh have not been explored during withdrawal from cocaine SA, increased gene expressions of choline acetyltransferase, nAChRs, and mAChRs are observed in mouse NAc after 28 days of withdrawal from a 7-day non-contingent cocaine procedure184. However, after prolonged, excessive-access (~90 mg/kg/day) cocaine SA, the activity of choline acetyltransferase in the NAc is persistently decreased up to 3 weeks into withdrawal185. These seeming discrepancies may reflect the procedural and subregional differences171, as neither of the above studies distinguished between the NAc core and shell subregions. It is not known whether these changes may mediate changes in DA and/or glutamate signaling in the NAc after withdrawal from cocaine exposure, although dopaminergic regulation of ACh levels in the NAcCo and Sh during non-contingent infusion has been demonstrated178.

SST-NPY-nNOS interneurons:

SSTIs represent <1% of the NAc neuronal population36, 186. In non-contingent drug models, optogenetic stimulation or inhibition of SSTIs in the NAc (Co/Sh), facilitates or suppresses the acquisition of cocaine CPP, respectively186, revealing a regulatory role of these neurons in rewarding-associated learning. After 7 days of non-contingent cocaine exposure, the intrinsic membrane excitability of SSTIs is decreased, together with changes in a wide range of transcripts including protein-coding genes, as well as regulatory RNAs186. These results present NAc SSTIs as a potential neuronal target for cocaine to induce prolonged local circuit and behavioral adaptations.

While it remains unclear how NAc SSTIs are affected following cocaine SA, important clues exist in studies of NAc nNOS signaling, for which SSTIs provide a critical local source. NAcCo nNOS signaling regulates relapse-like behaviors by inducing S-nitrosylation of GluA1 subunits of AMPARs, AMPAR auxiliary subunit stargazin, extracellular endopeptidases matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2 and MMP-9, and other key molecules critical for synaptic stability and plasticity31, 187–190. Therefore, by engaging nNOS signaling, SSTIs may participate in the synaptic remodeling of NAc MSNs and regulate related behaviors.

Fast-spiking interneurons:

FSIs represent ~1% of NAc neuronal population37. They exert powerful feed-forward inhibition onto MSNs, and are thought to orchestrate NAc MSN functional ensembles during behavior40. After 1 day or 40 days of withdrawal from repeated non-contingent cocaine procedures (15 mg/kg/injection), the membrane excitability of NAcSh FSIs is increased in mice191. By contrast, the membrane excitability of NAcSh MSNs is decreased following similar non-contingent as well as contingent cocaine procedures, a prominent cellular change that contributes to incubation of cue-induced cocaine craving after drug withdrawal192–196. Thus, an increased membrane excitability of FSIs may strengthen the inhibitory control over MSNs, aggravating the hypoactive state of NAcSh MSNs after cocaine withdrawal.

After short (1-day)- or long (40–45 day)-term withdrawal from either 5 days of non-contingent (15 mg/kg/injection) or 10 days of limited-access cocaine SA (0.75 mg/kg/infusion), the basal FSI-to-MSN synaptic transmission in the NAcSh, as well as the CB1-mediated short-term plasticity of this transmission, are not altered191, 197. However, the excitatory drive to NAcSh FSIs is increased after cocaine. Specifically, glutamatergic inputs from the BLA to NAcSh FSIs exhibit increased release probability after 45 days of withdrawal from 10-day cocaine SA197. Furthermore, optogenetically-induced LTP that mimics this projection-specific synaptic strengthening expedites the acquisition of cocaine SA40, 197. Thus, although the basic framework of FSI-mediated feedforward circuit is ‘immune’, the excitatory drive to FSIs undergo adaptive changes after cocaine, tweaking the functional output of NAc MSNs favoring cocaine-motivated behaviors.

A glimpse of neuronal ensembles

Behavioral adaptations following exposure to drugs of abuse are thought to be mediated by distinct neuronal ensembles in the reward circuitry198, 199, which are separate from those directing natural reward seeking, and further distinguished along different aspects of SUD-associated behaviors199, 200. For example, cocaine versus sucrose seeking in response to reward-associated cues engage distinct sets of NAcCo D1 MSNs in the same animals199. Moreover, combining Fos-labeling of neuronal ensembles and Daun02 inactivation procedure, it is shown that context-induced reinstatement of cocaine seeking, tested following extinction from 12 days of cocaine SA, is mediated by context-specific ensembles in the NAcSh (but not NAcCo)201. Using a similar approach, it is shown in mice after 14 days of cocaine SA that separate vmPFC ensembles, connecting to NAcCo or NAcSh respectively, control cocaine SA versus extinction76. These results underscore a highly selective feature of individual NAc-associated ensembles.

Remarkably, categorizing MSNs along the anatomical-by-genetic dimensions appears to match, to a certain degree, with the neuronal ensembles in the NAc. For example, cocaine CPP-encoding ensembles in the vHipp CA1 may strengthen their synaptic connections with a select population of NAcCo D1 (but not D2) MSNs to form a large, circuit level ensemble202. Conversely, cocaine CPP also leads to increased coupling between hippocampal place cells and a subset of NAc D2 MSNs203. Taken the two studies together, the vHipp-to-NAcCo D1 MSN projection may preferentially encode contextual information, while the vHipp-to-D2 MSN projection may facilitate the behavioral execution after the memory is reactivated by cocaine-associated context.

Formation and organization of neuronal ensembles encoding drug experience may rely on Hebbian and other plasticity mechanisms198, 204–206, and are likely boosted by developmental mechanisms as postulated by the rejuvenation hypothesis70. While ensemble-specific synaptic potentiation has been observed following cocaine CPP202, 203, a demonstration of NAc ensemble-specific potentiation following cocaine SA is still missing. Similarly, the role of silent synapses has not been directly assessed when cocaine-encoding NAc ensembles are formed. However, silent synapses are revealed in ensemble-specific neurons following re-exposure to cocaine context-associated cues after 6–11 days of withdrawal from non-contingent cocaine (15–20 mg/kg, 5 d)50, 51, perhaps reflecting a destabilization of ensemble synapses and internalization of synaptic AMPARs upon drug-cue re-exposure, analogous to that following cocaine SA59. These results provide indications that silent synapses may participate in the formation and/or reorganization of neuronal ensembles mediating SUD-associated behaviors.

An important feature of Fos-based identification of cocaine ensembles is that only a small fraction of NAc MSNs (2%−5%) is labeled, which exhibit distinct electrophysiological properties from the non-labeled but otherwise identical neighboring neurons50, 51, 207, 208. Thus, the large-scale generation and maturation of silent synapses in the NAcSh detected after contingent or non-contingent cocaine exposures may serve a permissive role in facilitating ensemble evolvement in response to cocaine.

Until recently, most of our focus had been aligned with the anatomical-by-cell type dimensions, which represents our best efforts to dissect cocaine-induced changes in NAc circuits. However, reward learning and seeking typically orchestrate both D1 and D2 MSN activities52, 79. It is conceivable that cocaine-encoding NAc ensembles are not limited by the cell types, pathways, or anatomical locations. As such, the different adaptations observed following different cocaine regimens (non-contingent versus contingent; short, long, versus intermittent access; incubation, extinction, versus reinstatement; etc.) may represent different cellular means through which different NAc ensembles are formed. Thus, detecting, differentiating, and monitoring ensemble formation, interaction, and plasticity over the course of cocaine-induce behaviors will help better conceptualize cocaine-induced plasticity, and target cocaine-induced plasticity with precise behavioral correlates.

Concluding remarks

Extensive preclinical research has demonstrated that cocaine experience induces adaptive changes in the brain reward circuit, exemplified by both acute and long-term changes at various glutamatergic synapses converging onto the NAc. These changes often exhibit projection and cell-type specificity, are mediated by different AMPAR subtypes, may organize into different functional ensembles, and differentially regulate cocaine-elicited behaviors. Beyond cocaine, projection and cell-type specificities of NAc circuits have also been observed in seeking behaviors induced by other drugs of abuse as well as natural rewards, with similar and yet differential cellular and circuit features in each case55, 120, 209–211. It is important for future studies to define both the uniqueness and common ground underlying the ensemble, circuit, and behavioral correlates induced by these drug/reward experiences.

Compared to where we stood two decades ago, our understanding of cocaine-induced neuroadaptations in the NAc with cell-type and projection specificities starts to depict a framework for revealing the complexity of neural networks that underlie SUD. Future efforts at circuit and systems levels are needed to understand how these projection- and cell type-specific changes coalesce into neuronal and circuit ensembles underlying cocaine memories. At the moment, molecular and genetic innovations to define and capture extensive behaviorally relevant neuronal ensembles, as well as the rapidly evolving large-population, chronic in vivo imaging and computational innovations to depict ensemble interactions and plasticity are forging new frontiers to substantially move the field forward.

Acknowledgement:

Preparation of this review was supported by NIH funds DA043826 (YHH), DA046346 (YHH), DA046491 (YHH), AA028145 (YHH), R01DA040620 (YD), R21DA047861 (YD), R37DA023206 (YD) and R21DA051010 (YD).

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no financial interest related to the content of this review. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Hyman SE. Addiction to cocaine and amphetamine. Neuron 1996; 16(5): 901–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyman SE, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. Neural mechanisms of addiction: the role of reward-related learning and memory. Annu Rev Neurosci 2006; 29: 565–598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hyman SE. Addiction: a disease of learning and memory. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162(8): 1414–1422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sesack SR, Grace AA. Cortico-Basal Ganglia reward network: microcircuitry. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010; 35(1): 27–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mogenson GJ, Jones DL, Yim CY. From motivation to action: functional interface between the limbic system and the motor system. Progress in neurobiology 1980; 14(2–3): 69–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelley AE. Memory and addiction: shared neural circuitry and molecular mechanisms. Neuron 2004; 44(1): 161–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox J, Witten IB. Striatal circuits for reward learning and decision-making. Nat Rev Neurosci 2019; 20(8): 482–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pettit HO, Ettenberg A, Bloom FE, Koob GF. Destruction of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens selectively attenuates cocaine but not heroin self-administration in rats. Psychopharmacology 1984; 84(2): 167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts DC, Koob GF, Klonoff P, Fibiger HC. Extinction and recovery of cocaine self-administration following 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the nucleus accumbens. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1980; 12(5): 781–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cador M, Bjijou Y, Stinus L. Evidence of a complete independence of the neurobiological substrates for the induction and expression of behavioral sensitization to amphetamine. Neuroscience 1995; 65(2): 385–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paulson PE, Robinson TE. Sensitization to systemic amphetamine produces an enhanced locomotor response to a subsequent intra-accumbens amphetamine challenge in rats. Psychopharmacology 1991; 104(1): 140–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kalivas PW. Glutamate systems in cocaine addiction. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2004; 4(1): 23–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tzschentke TM, Schmidt WJ. Glutamatergic mechanisms in addiction. Mol Psychiatry 2003; 8(4): 373–382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ito R, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Differential control over cocaine-seeking behavior by nucleus accumbens core and shell. Nat Neurosci 2004; 7(4): 389–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nat Neurosci 2005; 8(11): 1481–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koob GF, Volkow ND. Neurocircuitry of addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology 2010; 35(1): 217–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pickens CL, Airavaara M, Theberge F, Fanous S, Hope BT, Shaham Y. Neurobiology of the incubation of drug craving. Trends Neurosci 2011; 34(8): 411–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venniro M, Caprioli D, Shaham Y. Animal models of drug relapse and craving: From drug priming-induced reinstatement to incubation of craving after voluntary abstinence. Prog Brain Res 2016; 224: 25–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Joffe ME, Grueter CA, Grueter BA. Biological substrates of addiction. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci 2014; 5(2): 151–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venniro M, Banks ML, Heilig M, Epstein DH, Shaham Y. Improving translation of animal models of addiction and relapse by reverse translation. Nat Rev Neurosci 2020; 21(11): 625–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richardson NR, Roberts DC. Progressive ratio schedules in drug self-administration studies in rats: a method to evaluate reinforcing efficacy. J Neurosci Methods 1996; 66(1): 1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolf ME. Synaptic mechanisms underlying persistent cocaine craving. Nat Rev Neurosci 2016; 17(6): 351–365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Everitt BJ, Belin D, Economidou D, Pelloux Y, Dalley JW, Robbins TW. Review. Neural mechanisms underlying the vulnerability to develop compulsive drug-seeking habits and addiction. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2008; 363(1507): 3125–3135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.O’Brien CP, Childress AR, Ehrman R, Robbins SJ. Conditioning factors in drug abuse: can they explain compulsion? Journal of psychopharmacology 1998; 12(1): 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shalev U, Grimm JW, Shaham Y. Neurobiology of relapse to heroin and cocaine seeking: a review. Pharmacol Rev 2002; 54(1): 1–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaham Y, Shalev U, Lu L, de Wit H, Stewart J. The reinstatement model of drug relapse: history, methodology and major findings. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003; 168(1–2): 3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Markou A, Weiss F, Gold LH, Caine SB, Schulteis G, Koob GF. Animal models of drug craving. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1993; 112(2–3): 163–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grimm JW, Hope BT, Wise RA, Shaham Y. Neuroadaptation. Incubation of cocaine craving after withdrawal. Nature 2001; 412(6843): 141–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tran-Nguyen LT, Fuchs RA, Coffey GP, Baker DA, O’Dell LE, Neisewander JL. Time-dependent changes in cocaine-seeking behavior and extracellular dopamine levels in the amygdala during cocaine withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology 1998; 19(1): 48–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz JL, Higgins ST. The validity of the reinstatement model of craving and relapse to drug use. Psychopharmacology 2003; 168(1–2): 21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scofield MD, Heinsbroek JA, Gipson CD, Kupchik YM, Spencer S, Smith AC et al. The Nucleus Accumbens: Mechanisms of Addiction across Drug Classes Reflect the Importance of Glutamate Homeostasis. Pharmacol Rev 2016; 68(3): 816–871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gerfen CR, Surmeier DJ. Modulation of striatal projection systems by dopamine. Annu Rev Neurosci 2011; 34: 441–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lobo MK, Nestler EJ. The striatal balancing act in drug addiction: distinct roles of direct and indirect pathway medium spiny neurons. Front Neuroanat 2011; 5: 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith RJ, Lobo MK, Spencer S, Kalivas PW. Cocaine-induced adaptations in D1 and D2 accumbens projection neurons (a dichotomy not necessarily synonymous with direct and indirect pathways). Current opinion in neurobiology 2013; 23(4): 546–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tritsch NX, Sabatini BL. Dopaminergic modulation of synaptic transmission in cortex and striatum. Neuron 2012; 76(1): 33–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kawaguchi Y, Wilson CJ, Augood SJ, Emson PC. Striatal interneurones: chemical, physiological and morphological characterization. Trends Neurosci 1995; 18(12): 527–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tepper JM, Tecuapetla F, Koos T, Ibanez-Sandoval O. Heterogeneity and diversity of striatal GABAergic interneurons. Front Neuroanat 2010; 4: 150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silberberg G, Bolam JP. Local and afferent synaptic pathways in the striatal microcircuitry. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2015; 33: 182–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tepper JM, Koos T, Ibanez-Sandoval O, Tecuapetla F, Faust TW, Assous M. Heterogeneity and Diversity of Striatal GABAergic Interneurons: Update 2018. Front Neuroanat 2018; 12: 91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schall TA, Wright WJ, Dong Y. Nucleus accumbens fast-spiking interneurons in motivational and addictive behaviors. Mol Psychiatry 2020: 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.White FJ, Hu XT, Zhang XF, Wolf ME. Repeated administration of cocaine or amphetamine alters neuronal responses to glutamate in the mesoaccumbens dopamine system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1995; 273(1): 445–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolf ME. The role of excitatory amino acids in behavioral sensitization to psychomotor stimulants. Prog Neurobiol 1998; 54(6): 679–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Robinson TE, Gorny G, Mitton E, Kolb B. Cocaine self-administration alters the morphology of dendrites and dendritic spines in the nucleus accumbens and neocortex. Synapse 2001; 39(3): 257–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson TE, Kolb B. Structural plasticity associated with exposure to drugs of abuse. Neuropharmacology 2004; 47 Suppl 1: 33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Russo SJ, Dietz DM, Dumitriu D, Morrison JH, Malenka RC, Nestler EJ. The addicted synapse: mechanisms of synaptic and structural plasticity in nucleus accumbens. Trends Neurosci 2010; 33(6): 267–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Golden SA, Russo SJ. Mechanisms of psychostimulant-induced structural plasticity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2012; 2(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Christian DT, Wang X, Chen EL, Sehgal LK, Ghassemlou MN, Miao JJ et al. Dynamic Alterations of Rat Nucleus Accumbens Dendritic Spines over 2 Months of Abstinence from Extended-Access Cocaine Self-Administration. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017; 42(3): 748–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huang YH, Lin Y, Mu P, Lee BR, Brown TE, Wayman G et al. In vivo cocaine experience generates silent synapses. Neuron 2009; 63(1): 40–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang YH, Schluter OM, Dong Y. Silent Synapses Speak Up: Updates of the Neural Rejuvenation Hypothesis of Drug Addiction. Neuroscientist 2015; 21(5): 451–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Koya E, Cruz FC, Ator R, Golden SA, Hoffman AF, Lupica CR et al. Silent synapses in selectively activated nucleus accumbens neurons following cocaine sensitization. Nat Neurosci 2012; 15(11): 1556–1562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whitaker LR, Carneiro de Oliveira PE, McPherson KB, Fallon RV, Planeta CS, Bonci A et al. Associative Learning Drives the Formation of Silent Synapses in Neuronal Ensembles of the Nucleus Accumbens. Biol Psychiatry 2016; 80(3): 246–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wright WJ, Dong Y. Psychostimulant-Induced Adaptations in Nucleus Accumbens Glutamatergic Transmission. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2020; 10(12): a039255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lee BR, Ma YY, Huang YH, Wang X, Otaka M, Ishikawa M et al. Maturation of silent synapses in amygdala-accumbens projection contributes to incubation of cocaine craving. Nat Neurosci 2013; 16(11): 1644–1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ma YY, Lee BR, Wang X, Guo C, Liu L, Cui R et al. Bidirectional modulation of incubation of cocaine craving by silent synapse-based remodeling of prefrontal cortex to accumbens projections. Neuron 2014; 83(6): 1453–1467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Graziane NM, Sun S, Wright WJ, Jang D, Liu Z, Huang YH et al. Opposing mechanisms mediate morphine- and cocaine-induced generation of silent synapses. Nat Neurosci 2016; 19(7): 915–925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Brown TE, Lee BR, Mu P, Ferguson D, Dietz D, Ohnishi YN et al. A silent synapse-based mechanism for cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization. J Neurosci 2011; 31(22): 8163–8174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Terrier J, Luscher C, Pascoli V. Cell-Type Specific Insertion of GluA2-Lacking AMPARs with Cocaine Exposure Leading to Sensitization, Cue-Induced Seeking, and Incubation of Craving. Neuropsychopharmacology 2016; 41(7): 1779–1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang J, Li KL, Shukla A, Beroun A, Ishikawa M, Huang X et al. Cocaine Triggers Astrocyte-Mediated Synaptogenesis. Biol Psychiatry 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Wright WJ, Graziane NM, Neumann PA, Hamilton PJ, Cates HM, Fuerst L et al. Silent synapses dictate cocaine memory destabilization and reconsolidation. Nat Neurosci 2020; 23(1): 32–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Conrad KL, Tseng KY, Uejima JL, Reimers JM, Heng LJ, Shaham Y et al. Formation of accumbens GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors mediates incubation of cocaine craving. Nature 2008; 454(7200): 118–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCutcheon JE, Loweth JA, Ford KA, Marinelli M, Wolf ME, Tseng KY. Group I mGluR activation reverses cocaine-induced accumulation of calcium-permeable AMPA receptors in nucleus accumbens synapses via a protein kinase C-dependent mechanism. J Neurosci 2011; 31(41): 14536–14541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Loweth JA, Reimers JM, Caccamise A, Stefanik MT, Woo KKY, Chauhan NM et al. mGlu1 tonically regulates levels of calcium-permeable AMPA receptors in cultured nucleus accumbens neurons through retinoic acid signaling and protein translation. Eur J Neurosci 2019; 50(3): 2590–2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Loweth JA, Scheyer AF, Milovanovic M, LaCrosse AL, Flores-Barrera E, Werner CT et al. Synaptic depression via mGluR1 positive allosteric modulation suppresses cue-induced cocaine craving. Nat Neurosci 2014; 17(1): 73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Scheyer AF, Wolf ME, Tseng KY. A protein synthesis-dependent mechanism sustains calcium-permeable AMPA receptor transmission in nucleus accumbens synapses during withdrawal from cocaine self-administration. J Neurosci 2014; 34(8): 3095–3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liao D, Hessler NA, Malinow R. Activation of postsynaptically silent synapses during pairing-induced LTP in CA1 region of hippocampal slice. Nature 1995; 375(6530): 400–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Isaac JT, Nicoll RA, Malenka RC. Evidence for silent synapses: implications for the expression of LTP. Neuron 1995; 15(2): 427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kerchner GA, Nicoll RA. Silent synapses and the emergence of a postsynaptic mechanism for LTP. Nat Rev Neurosci 2008; 9(11): 813–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hanse E, Seth H, Riebe I. AMPA-silent synapses in brain development and pathology. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013; 14(12): 839–850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Durand GM, Kovalchuk Y, Konnerth A. Long-term potentiation and functional synapse induction in developing hippocampus. Nature 1996; 381(6577): 71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dong Y, Nestler EJ. The neural rejuvenation hypothesis of cocaine addiction. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2014; 35(8): 374–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bellone C, Luscher C. Drug-evoked plasticity: do addictive drugs reopen a critical period of postnatal synaptic development? Front Mol Neurosci 2012; 5: 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Valjent E, Bertran-Gonzalez J, Hervé D, Fisone G, Girault J-A. Looking BAC at striatal signaling: cell-specific analysis in new transgenic mice. Trends in neurosciences 2009; 32(10): 538–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ade KK, Wan Y, Chen M, Gloss B, Calakos N. An Improved BAC Transgenic Fluorescent Reporter Line for Sensitive and Specific Identification of Striatonigral Medium Spiny Neurons. Front Syst Neurosci 2011; 5: 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim J, Park BH, Lee JH, Park SK, Kim JH. Cell type-specific alterations in the nucleus accumbens by repeated exposures to cocaine. Biol Psychiatry 2011; 69(11): 1026–1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lee KW, Kim Y, Kim AM, Helmin K, Nairn AC, Greengard P. Cocaine-induced dendritic spine formation in D1 and D2 dopamine receptor-containing medium spiny neurons in nucleus accumbens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2006; 103(9): 3399–3404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pardo-Garcia TR, Garcia-Keller C, Penaloza T, Richie CT, Pickel J, Hope BT et al. Ventral pallidum is the primary target for accumbens D1 projections driving cocaine seeking. Journal of Neuroscience 2019; 39(11): 2041–2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Heinsbroek JA, Bobadilla AC, Dereschewitz E, Assali A, Chalhoub RM, Cowan CW et al. Opposing Regulation of Cocaine Seeking by Glutamate and GABA Neurons in the Ventral Pallidum. Cell Rep 2020; 30(6): 2018–2027 e2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kupchik YM, Brown RM, Heinsbroek JA, Lobo MK, Schwartz DJ, Kalivas PW. Coding the direct/indirect pathways by D1 and D2 receptors is not valid for accumbens projections. Nature neuroscience 2015; 18(9): 1230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Calipari ES, Bagot RC, Purushothaman I, Davidson TJ, Yorgason JT, Pena CJ et al. In vivo imaging identifies temporal signature of D1 and D2 medium spiny neurons in cocaine reward. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016; 113(10): 2726–2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]