Abstract

When mammalian cells are subjected to stress targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), such as depletion of the ER Ca2+ store, the transcription of a family of glucose-regulated protein (GRP) genes encoding ER chaperones is induced. The GRP promoters contain multiple copies of the ER stress response element (ERSE), consisting of a unique tripartite structure, CCAAT(N9)CCACG. Within a subset of mammalian ERSEs, N9 represents a GC-rich sequence of 9 bp that is conserved across species. A novel complex (termed ERSF) exhibits enhanced binding to the ERSE of the grp78 and ERp72 promoters using HeLa nuclear extracts prepared from ER-stressed cells. Optimal binding of ERSF to ERSE and maximal ERSE-mediated stress inducibility require the conserved GGC motif within the 9-bp region. Through chromatographic purification and subsequent microsequencing, we have identified ERSF as TFII-I. Whereas TFII-I remains predominantly nuclear in both nontreated NIH 3T3 cells and cells treated with thapsigargin (Tg), a potent inducer of the GRP stress response through depletion of the ER Ca2+ store, the level of TFII-I transcript was elevated in Tg-stressed cells, correlating with an increase in TFII-I protein level in the nuclei of Tg-stressed cells. Purified recombinant TFII-I isoforms bind directly to the ERSEs of grp78 and ERp72 promoters. The stimulation of ERSE-mediated transcription by TFII-I requires the consensus tyrosine phosphorylation site of TFII-I and the GGC sequence motif of the ERSE. We further discovered that TFII-I is an interactive protein partner of ATF6 and that optimal stimulation of ERSE by ATF6 requires TFII-I.

When mammalian cells are subjected to Ca2+ depletion stress or glycosylation block, the transcription of a family of glucose-regulated protein (GRP) genes encoding endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperones is induced. The GRP promoters contain multiple copies of the ER stress response element (ERSE) (20, 26). The ERSE consists of a tripartite structure, CCAAT(N9)CCACG, with N being an invariant region of 9 bp. Through binding site competitions and immuno-cross-reactivity, two major transcription factors from HeLa cell nuclear extracts (NEs) that bind to the ERSE have been identified. They are NF-Y/CBF and YY1, and they interact with the CCAAT and CCACG elements, respectively (11, 21).

Using −98 ERSE1 of the rat grp78 promoter as a model system, we discovered a novel complex (termed ERSF) in NE prepared from ER-stressed HeLa cells that exhibits enhanced binding to the ERSE (20). Optimal binding of the ERSF to the ERSE requires a conserved GGC motif within the internal 9-bp region. Specific mutation of the GGC motif results in substantial loss of stress inducibility mediated by the ERSE. However, ERSF binding to the ERSE alone is not sufficient to activate the ER stress response, since full stress inducibility of ERSE requires integrity of the CCAAT, GGC, and CCACG sequence motifs, as well as precise spacing among these sites. In addition, ATF6, a basic leucine zipper protein, activates the ERSE through the CCACG sequence (6, 26, 27). ATF6 itself undergoes ER stress-induced changes and has been shown to interact with ERSE binding factors YY1 and NF-Y (6, 9, 27). There is also evidence suggesting the existence of a mammalian homologue of the yeast Hac1 protein that binds selectively to a unfolded protein response element-related sequence within the −163 ERSE3 of the rat grp78 promoter (4). Collectively, these findings imply that multiple transcription factors are required for ERSE activation through direct or indirect interaction with DNA regulatory elements on the ERSE. The mechanism for these upstream regulatory complexes to communicate with the basal transcription machinery of the GRP promoters is presently unknown.

The transcription factor TFII-I was isolated as a binding protein that binds to the initiator elements in core promoters of TATA-less promoters (18, 19). Subsequently, it has been shown that TFII-I can also bind to E-box elements and can interact with upstream regulatory factors, such as USF1 and c-myc (16, 17). In addition to the 957-amino-acid form of TFII-I (referred to as Δ), there are three other alternatively spliced forms of TFII-I (α, β, and γ) (3). The primary structure of the multiple forms of TFII-I, ranging in size from 120 to 150 kDa, contains six directly repeated 90-residue motifs that each possess a potential helix-loop–span-helix homology (5, 17). These unique structural features suggest that TFII-I may have the capacity for multiple protein-protein interactions and, potentially, multiple protein-DNA interactions. In support of this possibility, ectopic TFII-I can act synergistically with USF1 to activate transcription of the adenovirus major late promoter in vivo (17).

Recent evidence suggests that TFII-I may also have a role in signal transduction. TFII-I is phosphorylated in vivo at serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues, and its activity is regulated by phosphorylation (14). Tyrosine phosphorylation of TFII-I is enhanced after epidermal growth factor stimulation (8). Also, the nuclear import of TFII-I could be regulated in response to antigenic stimuli (15). Thus, it has been proposed that TFII-I is a multifunctional protein that can coordinate the formation of an active promoter complex and provide linkage-specific signal-responsive activator complexes to the general transcription machinery (5, 17). TFII-I itself could also be a sensor of induction stimuli, resulting in specific modifications upon stimulation of gene expression. Through chromatographic purification and microsequencing, we have identified ERSF as TFII-I. In NIH 3T3 cells, TFII-I remains predominantly nuclear in both control cells and cells treated with thapsigargin (Tg), a potent inducer of the GRP stress response through depletion of the ER Ca2+ store. However, in Tg-treated cells, the level of TFII-I transcript was elevated, correlating with an overall increase in TFII-I protein level in the nuclei of Tg-stressed cells. Purified recombinant isoforms of TFII-I bind directly to the ERSE of the grp78 and ERp72 promoters. The stimulation of ERSE-mediated transcription by TFII-I requires the integrity of the consensus tyrosine phosphorylation site and the GGC sequence motif of the ERSE. We further discovered that TFII-I is an interactive protein partner of ATF6 and that optimal stimulation of ERSE by ATF6 requires TFII-I.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture conditions.

NIH 3T3 and COS cells were maintained in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum, 2 mM glutamine, and 1% penicillin-streptomycin-neomycin antibiotics at 35°C. For stress induction, cells were grown to 80% confluence and treated with 300 nM Tg for various time intervals as indicated.

EMSAs.

HeLa S-3 cells were grown in 2-liter suspension cultures (approximately 1.4 × 109 cells) and subsequently treated in the presence or absence of 300 nM Tg for 5 h. NEs were prepared by the method of Shapiro et al. (22). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were performed as described previously (20) or with some minor modifications. The sequences of the −98 ERSE of rat grp78 and −194 ERSE of murine ERp72 oligomers have been described previously (20). Synthetic oligonucleotides were supplied by Sigma-Genosys. The oligonucleotides were reannealed and radiolabeled. The NE (4.5 μg) was mixed with 15 to 180 ng of sonicated poly(dI · dC) in EMSA binding buffer consisting of 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM EDTA, 5% glycerol, 2 μg of bovine serum albumin (BSA) per 20 μl, and 0.5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). The samples were preincubated at 4°C for 10 min, and then 3 ng of labeled oligonucleotides was added, followed by incubation at 4°C for 15 min. The reaction mixtures were electrophoresed on 5% polyacrylamide gels. For antibody inhibition of protein-DNA interaction, 4.5 μg of Tg-treated HeLa NE in EMSA binding buffer containing 180 ng of poly(dI · dC) was preincubated for 30 min at 4°C with either 2 μl of water, 2 μl of normal rabbit serum, or 2 μl of rabbit polyclonal anti-TFII-I antibody (13) prior to the addition of the 32P-labeled −98 ERSE oligonucleotide probe.

Binding of recombinant TFII-I to ERSE.

Whole-cell extracts were prepared from COS cells transfected with a plasmid containing a glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged TFII-I cDNA (pEBGTFII-I) or with an empty vector (pEBG) (2). Fifty micrograms of each extract was incubated with 15 μl of glutathione-agarose beads (Sigma) for 2 h at 4°C on a shaker. Subsequently, the beads were centrifuged for 10 s at 4,000 × g, decanted, and washed five times at 4°C with 75 μl of a solution containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.8), 100 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and 1 μg each of leupeptin, antipain, aprotinin, and pepstatin per ml. The bound protein was eluted for 30 min at 4°C in 16 μl of 10 mM reduced glutathione (Sigma) contained in EMSA binding buffer and 3 ng of poly(dI · dC). The mixture was added to 2 ng of 32P-labeled ERSE duplex oligonucleotide, and binding was performed at 4°C in 20 μl for 15 min. The reaction mixtures were electrophoresed on a 5% polyacrylamide gel.

TFII-I isoforms.

For ectopic expression of Δ and β isoforms of TFII-I, COS7 cells were transfected with 7.5 μg of expression plasmids (pEBGII-IΔ or pEBGII-Iβ) as described previously (3). For affinity purification of recombinant proteins, cells were harvested at 36 h posttransfection and whole-cell extracts were prepared by addition of lysis buffer BC100 (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 100 mM KCl, 10% [vol/vol] glycerol) containing 0.2% Triton X-100, Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Complete EDTA-free (Boehringer Mannheim), and phosphatase inhibitors (5 mM NaF, 2 mM Na3VO4, and 1 mM Na4P2O7). The cell lysate was clarified by centrifugation for 10 min at 15,300 × g at 4°C. The GST-His 6-tagged TFII-I was purified by using a TALON column (Clontech) as described previously (3). The EMSA conditions for the purified TFII-I isoforms (see Fig. 9) were as follows. Either Tg-treated HeLa NEs (0.75 μg) or recombinant forms of TFII-I isoforms were incubated with the ERSE probes at 30°C for 20 min in buffer B100 containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.3), 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 100 mM KCl, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 100 ng of BSA/μl, 2.5 ng of poly(dA · dT)/μl, and 5 mM DTT in a final volume of 20 μl. The DNA-protein complex was separated on a 5% native polyacrylamide gel as described previously (13).

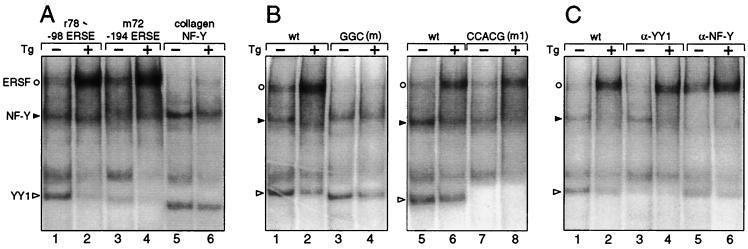

FIG. 9.

Binding of purified GST–TFII-I isoforms to −98 ERSE. (A) GST–TFII-I was purified from COS cells transfected with expression vector for the Δ form of GST–TFII-I (120 kDa) or the β form of GST–TFII-I (128 kDa). These were used in the EMSAs with 32P-labeled −98 ERSE as a probe performed under conditions that optimized TFII-I isoform binding (see Materials and Methods). Lanes 1 and 3, probe alone; lanes 2 and 4, isoform complexes being formed. HeLa NE from Tg-treated cells was mixed with the −98 ERSE probe under the same EMSA conditions used for the TFII-I isoforms in the absence (lane 6) or presence (lane 7) of anti-TFII-I antibody. Lane 5, probe alone. wt, wild type. (B) The probes used were the −98 ERSE wt (lanes 1 and 2), the −98 ERSE GGC mutant (lanes 3 and 4), and the −194 ERSE from ERp72 (lanes 5 and 6) as indicated. GST–TFII-Iβ was used in the EMSA reactions.

UV cross-linking.

Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU)-substituted probes were prepared by annealing 215 ng of −98 ERSE oligonucleotide with 142 ng of primers (RP1 paired with RP2 and RP3 paired with RP4 [see Fig. 3A]). The primer was extended in a reaction with 17 μM BrdUTP, 17 μM dATP, 17 μM dGTP, 2 μM dCTP, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.9), 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM DTT, 80 μCi of [α-32P]dCTP (3,000 Ci/mmol), and 20 U of Klenow fragment for 1 h at room temperature. The reaction was continued for 30 min by adding 15 μM dCTP, followed by heat inactivation and ethanol precipitation. EMSA binding reactions were with 20 μg of HeLa NE from either control or Tg-treated cells in the EMSA binding buffer containing 240 ng of poly(dI · dC). The EMSA reaction mixture was preincubated for 10 min at 4°C, followed by incubation with 32P-labeled −98 ERSE probe for 15 min at 4°C. The reaction mixture was electrophoresed on a 5% polyacrylamide gel (40:1 acrylamide–N,N′-bisacrylcystamine) in 1× Tris-borate-EDTA for 2 h at 200 V. The gel was then irradiated with 0.5 J in a UV Stratalinker 2400 (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). Following autoradiography, the band corresponding to DNA-bound ERSF was excised and crushed. The sample was treated with 30 μl of β-mercaptoethanol and 100 μl of a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer containing 160 mM Tris (pH 6.8), 5.8% SDS, 0.17 M β-mercaptoethanol, and 25% glycerol. The sample was heated at 100°C for 10 min and electrophoresed with prestained protein markers (New England Biolabs) on an SDS–7% polyacrylamide gel at 40 mA for 3.5 h. The gel was dried and subjected to autoradiography.

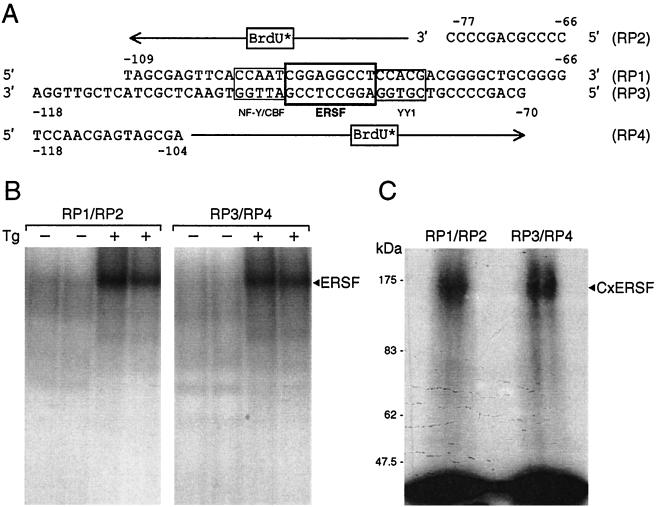

FIG. 3.

UV cross-linking of the ERSF complex. (A) Sequence of −98 ERSE with the locations of the NF-Y, YY1, and ERSF binding sites boxed. The primers for the BrdU substitution and the orientation of the extended products are indicated. (B) Preparative EMSA gel for isolating ERSF complexes using either RP1-RP2 or RP3-RP4 as template-primer. The EMSA binding reactions included HeLa NE from either control or Tg-treated cells and were performed in duplicate. The autoradiograms are shown. The position of the ERSF complex is indicated. (C) Estimation of the molecular size of the ERSF UV-cross-linked complex. The preparative gel shown in panel B was subjected to UV cross-linking. The bands corresponding to ERSF obtained with RP1-RP2 or RP3-RP4 were excised and subjected to SDS-PAGE. The autoradiogram is shown. The positions of the ERSF cross-linked complex (CxERSF) and the molecular size markers are indicated.

Protein purification.

SP Sepharose (cation-exchange) and Q Sepharose (anion-exchange) (Amersham Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.) chromatographies were performed in tandem using 4.0 mg of HeLa NE filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter. The extract (480 μl) was diluted with 1.5 ml of APB (40 mM Tris-HCI [pH 7.6], 40 mM NaF, 40 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3O4, 5 mM metabisulfite, 10 mM benzamidine, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 20% glycerol). The columns (resin volume of 1 ml) were washed and equilibrated with APB, and fractions were eluted at 4°C using a salt gradient (0 to 1.0 M KCl). One-milliliter fractions were collected at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min. EMSA reactions were performed using 2 μl of each fraction, 15 ng of poly(dI · dC), and the −98 ERSE oligonucleotide probe. Fractions 16 to 21 (0.3 to 0.9 M KCl) containing ERSF binding activity were pooled and mixed with APB to yield a 0.1 M KCl solution. The concentration of proteins in each fraction was determined by the Bio-Rad assay using BSA as a standard. The pooled fractions diluted to 30 ml was pumped into a 1-ml heparin Sepharose column preequilibrated with APB containing 0.1 M KCl. One-milliliter fractions were collected at a flow rate of 1 ml/min using a salt gradient (0.1 to 1.0 M KCl). Fractions 14 and 15 (0.46 to 0.52 M KCl), containing the majority of the ERSF binding activity, were pooled. The sample was then chromatographed on a DNA Sepharose affinity column containing the human −61 ERSE1 element (26), which is homologous to rat −98 ERSE1. The DNA affinity column was prepared by the method of Kadonaga (7). Briefly, 250 μg (each) of complementary oligonucleotides was annealed. The ends of the duplex oligonucleotide were phosphorylated in a T4 polynucleotide kinase reaction. The 5′-phosphorylated DNA was then ligated using T4 DNA ligase. The DNA was then coupled to 1.5 g of CNBr-activated Sepharose 4B (Fluka BioChemika, Buchs, Switzerland) using 0.5 M Tris, pH 8.0. Fourteen micrograms of poly(dI · dC) and 1.9 mg of BSA were added to the pooled fractions from the heparin Sepharose column. This sample was diluted to yield 1× APB in 0.1 M KCl. The sample was loaded onto a 0.5-ml column, and 1.0-ml fractions were collected from a 0.1 to 1.0 M KCl gradient. EMSA analysis was performed to detect ERSF binding. The proteins in the DNA affinity fractions were analyzed by silver staining of SDS-polyacrylamide gels, in parallel with high-molecular-weight protein markers (Amersham Pharmacia).

Peptide sequencing.

Six hundred microliters of fraction 9 of the DNA affinity column eluate containing the largest amount of ERSF binding activity was concentrated (Millipore, Bedford, Mass.) to a 40-μl volume and then electrophoresed on a preparative SDS–8% polyacrylamide gel. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue, and the ERSF protein band was excised and subjected to microsequencing (W.M. Keck Biomedical Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, University of Virginia, Charlottesville). The data generated were analyzed by searching the National Center for Biotechnology Information nonredundant database using the Sequest algorithm.

Immunofluorescence staining.

NIH 3T3 cells were grown to 80% confluence in chamber slides (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, Ill.), washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min. The cells were permeabilized in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, 0.1% NP-40, and 5% BSA for 1 h. For detection of TFII-I, the cells were stained with anti-TFII-I antibody (Ab2240 [a gift of S. Desiderio, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine] at a 1:300 dilution) as a primary antibody and the fluorescein-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (1:100 dilution) (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, Calif.) as a secondary antibody. For the detection of hemagglutinin-ATF6 (HA-ATF6), the transfected COS cells were stained with monoclonal anti-HA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, Calif.) at a 1:500 dilution as a primary antibody and the Texas Red anti-mouse IgG (1:100 dilution) (Vector Laboratories Inc.) as a secondary antibody. The cells were mounted using Vecta Shield mounting solution (Vector Laboratories Inc.), with or without propidium iodide counterstaining.

Plasmids.

The construction of (−109/−74)MCAT containing two copies of −98 ERSE linked to the minimal promoter of mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) driving the expression of chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) has been described previously (10). The construction of the GGC mutant of −98 ERSE has been described previously (20). The mammalian expression vector pCGN-ATF6 containing HA-tagged full-length ATF6 driven by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (a gift of R. Prywes, Columbia University) has been described previously (29). The construction of expression vectors for myc–TFII-I (BAP-135 cloned into the vector pCIS2, a gift of S. Desiderio) (25) and GST–TFII-I cloned into the vector pEBG (pEBGTFII-I) has been described previously (2). The construction of the tyrosine phosphorylation site mutant of GST-tagged TFII-I referred to as the YY-FF mutant has been described previously (14).

For the construction of the antisense expression vector for TFII-I [TFII-I(N)/AS] and its sense control [TFII-I(N)/S], the myc–TFII-I expression vector (BAP-135) was digested with BglII to generate a 1,168-bp fragment that encompasses part of the vector sequence and extends 1,125 bp into the TFII-I-coding sequence. Simultaneously, the pCIS2 vector was cleaved with BglII (unique site downstream from the CMV promoter-enhancer). Following electrophoresis, the 1,168-bp BglII fragment and BglII-linearized pCIS2 vector DNA were excised and purified (Qiagen). The purified BglII-cut pCIS2 vector DNA was then dephosphorylated with calf intestine alkaline phosphatase. The linearized vector and 1,168-bp BglII fragment were ligated with T4 DNA ligase (Boehringer Mannheim). DNA from the transformants was digested with XhoI, KpnI, or SspI to generate restriction digest patterns for confirmation of the antisense versus sense orientation of the 1,168-bp TFII-I subfragment with respect to the CMV promoter.

Northern blotting.

For Northern analysis, total RNA was isolated from NIH 3T3 cells using Tri-reagent (Sigma). For each sample, 15 μg of total RNA was separated by formaldehyde-agarose gel electrophoresis and transferred to a nylon membrane via capillary transfer. The blot was dried and UV cross-linked before it was prehybridized in prehybridization solution (5× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate], 5× Denhardt solution, 1% SDS, and 100 μg of denatured salmon sperm DNA per ml) for 4 h at 42°C. Hybridization was carried out overnight in Perfect-Hyb buffer (Sigma) using a 32P-labeled 1,168-bp BglII subfragment of TFII-I. The membrane was washed twice for 30 min in 1× SSC–0.1% SDS at 45°C and then exposed to X-OMAT AR film (Kodak) for 12 h.

Transfection conditions.

COS cells were seeded in six-well plates and grown to about 60 to 80% confluence. One microgram of the (−109/−74)MCAT reporter plasmid was cotransfected with 1 μg of pCH110, an expression vector for β-galactosidase under the control of the simian virus 40 promoter, as an internal control for transfection efficiency, along with various amounts of expression vectors for GST- or myc-tagged TFII-I, HA-tagged ATF6, or their respective empty vectors, using SuperFect reagent (Qiagen). For stress induction, 24 h after transfection the cells were treated with 300 nM Tg for 16 h prior to harvesting. Preparation of the cell lysates for CAT assays and quantitation of the CAT assays have been described previously (11). Cell extracts corresponding to equal β-galactosidase units were used.

Western blotting.

Conditions for Western blotting were as previously described (9). Whole-cell lysates were prepared in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. For detection of endogenous TFII-I, the primary antibody was Ab2240 at a 1:500 dilution. The second antibody was horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Sigma), at a dilution of 1:6,600. For detection of the myc or HA epitopes, the primary antibodies were mouse monoclonal anti-HA (at a dilution of 1:500) or anti-myc (at a dilution of 1:2,000) antibodies (Santa Cruz Inc.). The secondary antibody was horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Roche, Indianapolis, Ind.) at a dilution of 1:5,000. Visualization of the protein bands was performed with an ECL kit (Amersham).

Coimmunoprecipitation assays.

COS cells at 80% confluence in 10-cm-diameter dishes were cotransfected with 4 μg of myc-tagged TFII-I and 4 μg of HA-tagged ATF6 or empty vector using SuperFect reagent. The cells with or without Tg treatment were harvested at 48 h after transfection and lysed in 300 μl of NP-40 buffer (0.5% NP-40, 50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150 mM sodium chloride). Protein extract (500 μg) from each sample was immunoprecipitated with anti-myc antibody. The conditions for the coimmunoprecipitation assays have been described previously (9). The immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS–8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–8% PAGE) and Western blotting using anti-HA antibody to detect the coimmunoprecipitation with HA-ATF6.

RESULTS

Binding of ERSF to a conserved GC-rich motif among a subset of mammalian ERSEs.

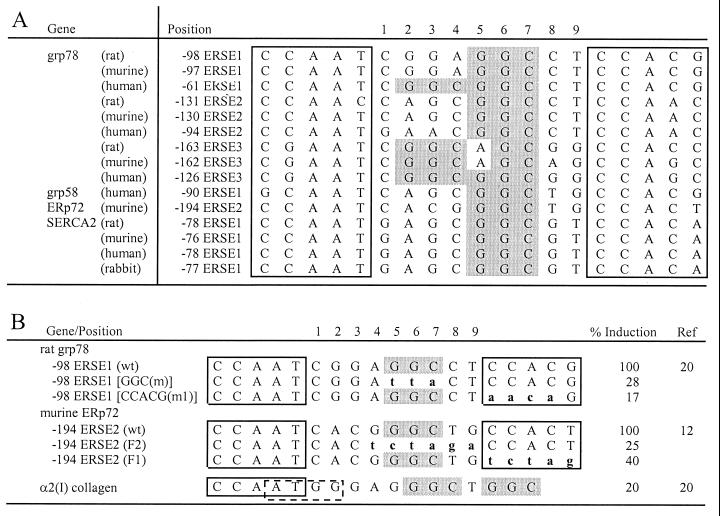

Promoters of a variety of ER stress-inducible genes from both vertebrates and invertebrates contain ERSE-like sequences (1, 12, 20, 23, 26). The ERSE consists of a tripartite structure, CCAAT(N9)CCACG. Within a subset of ERSEs from the promoters of the mammalian grp78, grp58, ERp72, and SERCA2 genes, N9 contains a strikingly GC-rich central sequence motif (Fig. 1A). The triplet sequence GGC occurs once and sometimes twice within the N9 region. Another striking feature is that the entire N9 sequence within each set of ERSEs is highly conserved across species. For example, the N9 sequence of ERSE1 from grp78 is totally conserved between rat, murine, and human with the exception of one base, whereas ERSE1 of SERCA2 from rat, murine, human, and rabbit is perfectly conserved. In support of the functional significance of the conserved GGC motif, two independent studies (12, 20) showed that direct mutation of the GGC motif within N9 resulted in inhibition of ER stress induction mediated by the ERSE, as was observed for the mutation of the 3′ flanking CCACG/T motif (Fig. 1B). These mutations on the rat grp78 ERSE1 and ERp72 ERSE2 did not change the 9-bp spacing of N9, nor did they alter the two other components of the ERSE. Further, the α2(I) collagen promoter containing two GGC motifs in a different sequence configuration was minimally induced by ER stress (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Sequence and spatial conservation of the GC-rich sequence motif within the N9 region of ERSE. (A) Sequence alignment of ERSEs from the promoter regions of the ER protein genes grp78, grp58, ERp72, and SERCA2 (1, 12, 20, 23, 26). The CCACT and CCACG motifs are boxed. For each ERSE, the negative number indicates the distance in base count of the first C of the CCAAT element with the transcription initiation site (set at +1). For each gene, the ERSEs are numbered (1 to 3) in the order of increasing distance upstream of the transcription initiation site. The GGC triplets within the 9-bp region of the ERSEs are shaded in gray. (B) The GGC sequence is required for optimal stress inducibility of ERSE-mediated transcription. The sequences of −98 ERSE1 of grp78 and −194 ERSE of ERp72 are shown with the CCAAT and CCACG/CCACT motifs boxed. The mutated bases of each ERSE are in lowercase and aligned against the wild-type (wt) sequences. For the grp78 reporter gene, ER stress was induced by Tg (20). For the ERp72 reporter gene, stress was induced by accumulation of μ heavy chain in the ER (12). The α2(I) collagen promoter contained an inverted YY1 binding site, CCAT (indicated by the dashed box), overlapping with the CCAAT sequence. Its induction by Tg was directly compared to that of the wild-type −98 ERSE of grp78 (20).

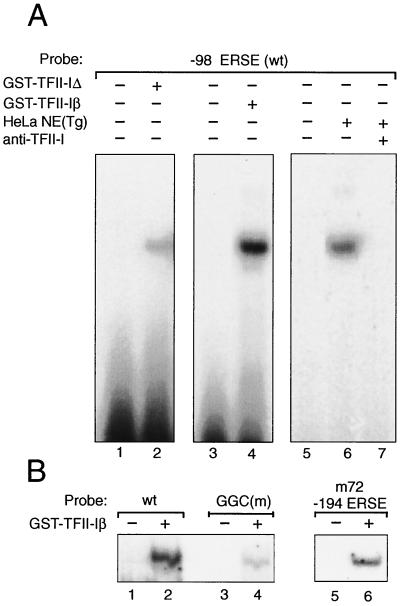

Using HeLa NEs prepared from control cells and cells treated with Tg, three complexes binding to the ERSEs of both the grp78 and ERp72 promoters could be detected (Fig. 2A). Two of the complexes have been identified as NF-Y, which is also referred to as CBF and YY1 (20). A stress-inducible complex, ERSF, was detected with ERSEs from both the grp78 and ERp72 promoters (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 to 4) but not with a GC-rich sequence derived from the α2(I) collagen promoter bearing a CCAAT sequence overlapping with a YY1 binding site (Fig. 2A, lanes 5 and 6). The binding of ERSF to the ERSE is dependent on the GGC motif (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 to 4) but does not require sequence integrity of the 3′ flanking CCACG motif (Fig. 2B, lanes 5 to 8). Further, while anti-NF-Y and anti-YY1 antibodies inhibited the formation of the constitutive faster-migrating complexes binding to the ERSE, the formation of ERSF was unaffected (Fig. 2C). We noted that after the removal of YY1, a faint residual band still persisted (Fig. 2C, lanes 3 and 4) but was totally eliminated through mutation of the CCACG sequence (Fig. 2B, lanes 7 and 8). This residual complex could be due to ATF6 or some other factor binding to the CCACG sequence. Collectively, these results indicate that it is unlikely that the ERSF complex contains NF-Y and YY1, which were previously shown to bind to the CCAAT and CCACG motifs, respectively, of −98 ERSE (ERSE1) of the rat grp78 promoter (20). The ERSF described here is also distinct from the stress-inducible complex of ATF6 and NF-Y, since that complex cannot be detected by gel shift assays using NEs and its formation is dependent on NF-Y and the CCACG motif (24, 27).

FIG. 2.

Requirement for stress-induced enhanced binding of ERSF to ERSE. (A) The EMSAs were performed with HeLa NEs prepared from either control (−) or Tg-treated (+) cells with the different probes as indicated at the top. (B) ERSF binding to ERSE requires the GGC motif. The EMSAs were performed with either the wild-type (wt) −98 ERSE of grp78 or the GGC(m) mutant as a probe. (C) The probe used was wt −98 ERSE. No antibody was added to the first two lanes. Anti-YY1 or anti-NF-Y antibody was added to the reaction mixture as indicated at the top. The ERSF, NF-Y, and YY1 complexes formed are indicated by an open circle, a closed arrowhead, and an open arrowhead, respectively.

Identification of TFII-I as ERSF through chromatographic purification.

To estimate the molecular size of ERSF, UV cross-linking was performed using HeLa NE and −98 ERSE as a probe. The scheme for labeling the ERSF protein complex is shown in Fig. 3A. Two −98 ERSE probes were prepared: one using the ERSE coding strand RP1 as the template and RP2 as the primer and the other using the ERSE noncoding strand RP3 as the template and RP4 as the primer. Both primers were extended in the presence of BrdU and [32P]dCTP. The radiolabeled, BrdU-substituted probes were used in EMSAs with HeLa NE prepared from control cells or cells treated with 300 nM Tg, under binding conditions that optimized ERSF binding (Fig. 3B). After UV cross-linking, the ERSF complexes derived from RP1-RP2 and RP3-RP4 were excised from the gel and subjected to SDS-PAGE. Both ERSF complexes yielded a labeled protein band of around 160 kDa (Fig. 3C). After subtraction of the molecular mass of the cross-linked oligomers, the estimated molecular mass of ERSF was about 130 kDa.

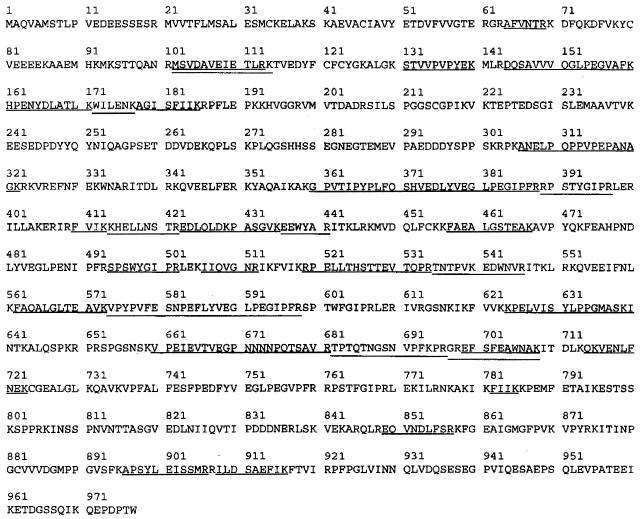

The steps for chromatographic purification of ERSF are shown in Fig. 4A. HeLa NE was fractionated on SP/Q Sepharose, heparin Sepharose, and DNA affinity columns sequentially. In the last column, the human sequence equivalent to −98 ERSE was coupled to CNBr-activated Sepharose and used for the purification of ERSF from heparin column fractions enriched for ERSF binding in EMSAs (Fig. 4B). The majority of the ERSF binding activity was recovered in the 0.2 M eluates of the DNA affinity column (Fig. 4C) and correlated with the appearance of a doublet protein band around 125 kDa in those fractions as revealed by silver staining (Fig. 4D). The peptide sequences of the doublet protein band were determined by mass spectrometry and found to be identical. The 32 peptide sequences generated matched directly to the sequence of human TFII-I (Fig. 5), a ubiquitous transcription factor with several isoforms ranging in size from 120 to 150 kDa (3).

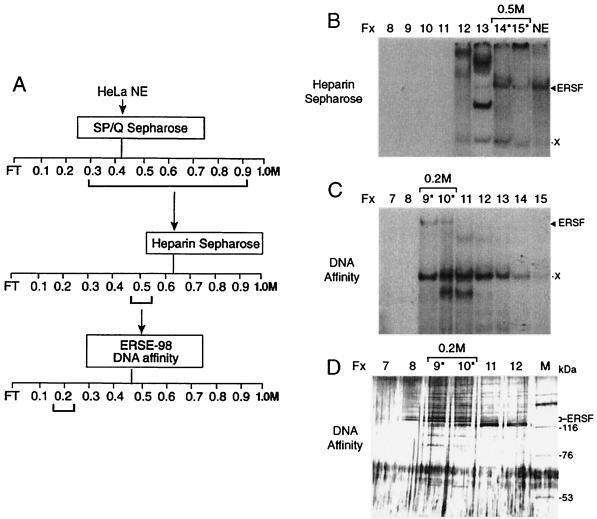

FIG. 4.

Protein purification of ERSF binding activity. (A) Scheme for ERSF purification. Salt concentrations at which ERSF binding activity eluted from the columns are bracketed. FT, flowthrough. (B) Heparin Sepharose column chromatography of pooled SP/Q Sepharose fractions. The EMSAs for eluted fractions (Fx) 8 through 15 (corresponding to 0.1 to 0.5 M KCl) are shown, with HeLa NE providing a positive control for the electrophoretic mobility of the ERSF complex. Fractions 14 and 15 were pooled for their ability to form the ERSF complex. The positions of the ERSF complex and an unknown copurifying complex (X) are indicated. The column fractions containing major ERSF binding activity are indicated with an asterisk. (C) DNA affinity column fractionation of ERSF binding activity. The EMSAs for fractions 7 through 15 (corresponding to 0.1 to 0.5 M KCl) are shown. (D) SDS-PAGE analysis of fractions from the DNA affinity column. Fifteen-microliter portions of fractions 7 through 12 were electrophoresed alongside high-molecular-weight protein markers (lane M) on an SDS–8% polyacrylamide gel. The gel was silver stained. The sizes of markers are indicated. Fractions 9 and 10 contain proteins which correlate with the major ERSF binding activity as defined by EMSAs.

FIG. 5.

Alignment of peptide sequence derived from ERSF with human TFII-I. The amino acid sequence of human TFII-I is shown. The matching peptides are underlined.

Increase of TFII-I in Tg-stressed cells.

Immunofluorescence studies were performed with NIH 3T3 cells to examine the amount and localization of the TFII-I following Tg stress. We observed that TFII-I existed primarily as a nuclear protein in both nonstressed and stressed cells (Fig. 6A). Through biochemical fractionation of the whole-cell extracts, we confirmed that the majority of TFII-I was recovered from 0.25 M NaCl washes of the nuclear preparation (reference 9 and data not shown). Further, we noted that the immunofluorescence staining for TFII-I was much more intense in cells following Tg treatment, suggesting that the amount of TFII-I was elevated in the stressed cells (Fig. 6A).

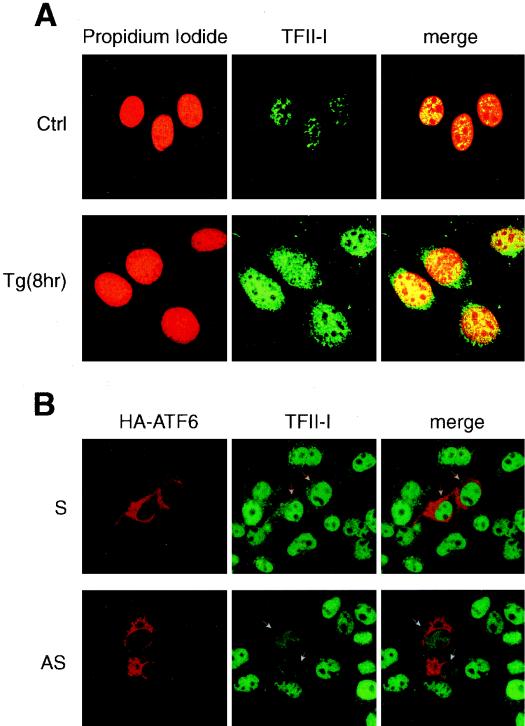

FIG. 6.

Nuclear localization of TFII-I. (A) NIH 3T3 cells were grown to 80% confluence in chamber slides. The cells were either not treated (Ctrl) or treated with 300 nM Tg for 8 h. The cells were stained with anti-TFII-I antibody (Ab2240) and viewed with a 40× oil immersion lens yielding a magnification of ×400, using a Zeiss confocal microscope with LSM 510 imaging software. The left panels show propidium iodide-stained nuclei, the middle panels show the TFII-I staining, and the right panels show the merge of the two immunofluorescence images. (B) COS cells were grown to 80% confluence in chamber slides. At 36 h following transient transfection, the cells were fixed and stained with an anti-HA epitope antibody and anti-TFII-I antibody (Ab2240). The upper set of images shows cells transfected with the sense (S) vector [myc-TFII-I(N)/S], and the lower set shows cells transfected with the antisense (AS) vector [myc-TFII-I(N)/AS]. Both sets were cotransfected with HA-ATF6. The left panel shows HA staining, the middle panel shows endogenous TFII-I staining, and the right panel shows the merge of the two images. The transfected cells, as indicated by high-level expression of the HA epitope, are indicated with arrowheads.

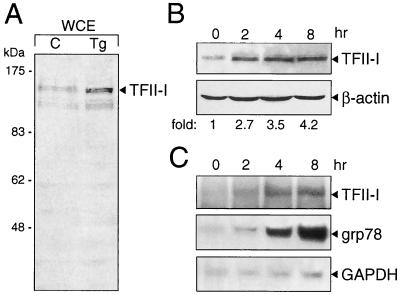

To confirm this observation, whole-cell extracts were prepared from NIH 3T3 cells and Western blot analysis was performed to detect the level of TFII-I. Compared with the level of TFII-I in control cells, an increase in TFII-I level was detected in cells treated with Tg for 6 h (Fig. 7A). To monitor the kinetics of induction of TFII-I, the cells were treated for various times with Tg and the level of TFII-I was examined. At 2 h following Tg treatment, a 2.7-fold increase in TFII-I was detectable; by 4 and 8 h the TFII-I level increased to 3.5- and 4.2-fold, respectively, after normalization to the β-actin level in each sample (Fig. 7B). To determine whether the increase in TFII-I protein level was due to an increase in the TFII-I transcript level, total RNA was isolated from control cells and cells treated with Tg. Northern blotting was performed to monitor the kinetics of induction of the TFII-I transcript. Our results showed that the increase in TFII-I protein level in Tg-stressed cells is at least in part due to an increase in TFII-I mRNA level (Fig. 7C). Further, the kinetics of Tg induction of TFII-I was similar to that of grp78 induction (Fig. 7C). This provides the first evidence that in NIH 3T3 cells TFII-I itself is upregulated following Tg stress.

FIG. 7.

Tg stress induction of endogenous TFII-I. (A) NIH 3T3 cells were either grown under normal culture conditions (lane C) or treated with Tg for 6 h. The whole-cell extract (WCE) was prepared by lysing the cells directly in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. The levels of TFII-I were detected by Western blotting using an anti-TFII-I antibody (Ab2240). (B) The cells were subjected to Tg treatment for the time indicated. TFII-I and β-actin protein levels were detected by Western blotting. The fold induction of TFII-I after normalization to the β-actin level is indicated. (C) Total RNA was prepared from NIH 3T3 cells treated with Tg for the time indicated. The levels of TFII-I, grp78, and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) transcripts were detected by Northern blotting.

TFII-I is an ERSE binding protein.

To investigate whether TFII-I is a component of the ERSF complex from HeLa NE that binds to −98 ERSE, we tested the effect of an antibody specifically directed against TFII-I on the formation of the ERSF complex in EMSA. The addition of the rabbit polyclonal anti-TFII-I antibody inhibited the formation of the ERSF complex, whereas normal rabbit serum was without effect (Fig. 8A). Similar results were observed with a second anti-TFII-I antibody derived independently (25) (data not shown). To determine whether TFII-I directly binds ERSF, COS cells were transfected with either the empty vector or the expression vector for GST–TFII-I. The purified GST protein was used in EMSA. We observed that under the standard conditions used for ERSF binding, purified GST–TFII-I exhibited a weak but detectable binding to −98 ERSE, with electrophoretic mobility similar to that of the ERSF complex formed using HeLa NE (Fig. 8B). Using EMSA conditions optimized for purified, recombinant TFII-I binding to DNA, we observed that both the 957-amino-acid form of TFII-I (TFII-I Δ) and the 978-amino-acid form (TFII-I β) readily bound −98 ERSE, with the TFII-I β form exhibiting a higher affinity than the Δ form (Fig. 9A, lanes 1 to 4). Under these same EMSA binding conditions for optimal TFII-I isoform binding, one predominant complex was formed when HeLa NE from Tg-treated cells was added to the −98 ERSE probe. This complex migrated at the same mobility as the TFII-I isoform DNA complex and was completely abolished with antibody against TFII-I (Fig. 9A, lanes 5 to 7). In agreement with the requirement of the GGC triplet sequence for the binding of ERSF from HeLa NE to −98 ERSE (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 to 4), the binding of recombinant TFII-I β to the −98 ERSE probe was diminished when the GGC sequence was mutated (Fig. 9B, lanes 1 to 4). As in the case of ERSF binding (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 4), recombinant TFII-I also bound −194 ERSE of the ERp72 promoter (Fig. 9B, lanes 5 and 6).

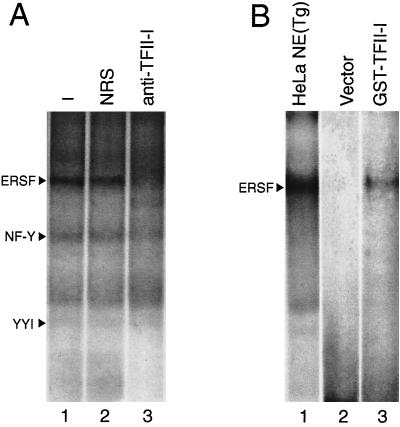

FIG. 8.

TFII-I is an ERSE binding protein. (A) Antibody inhibition of ERSF complex formation. EMSAs were performed using HeLa NE from Tg-treated cells and 32P-labeled −98 ERSE as a probe. Lane 1, standard EMSA reaction; lane 2, preincubation of the extract with 2 μl of normal rabbit serum (NRS); lane 3, binding reaction with 2 μl of the anti-TFII-I antibody. The positions of the ERSF, NF-Y, and YY1 complexes are indicated. (B) Binding of GST–TFII-I to −98 ERSE. An EMSA is presented for reactions of 32P-labeled −98 ERSE as a probe and GST–TFII-I purified from extracts of COS cells transfected with either the empty vector (lane 2) or the expression vector for GST-TFII-I (lane 3). The band detected in lane 3 comigrated with the ERSF complex formed between −98 ERSE and HeLa NE prepared from Tg-treated cells (lane 1).

Transcription activation of ERSE by TFII-I.

To test whether TFII-I can activate −98 ERSE, COS cells were cotransfected with (−109/−74)MCAT containing two copies of −98 ERSE linked to the MMTV minimal promoter directing the expression of the CAT reporter gene. COS cells were used because of the relatively low endogenous level of TFII-I. Under nonstressed conditions, TFII-I was able to enhance ERSE-mediated transcription activity in a dosage-dependent manner (Fig. 10). In cells treated with Tg when the promoter activity was already at high level, overexpression of TFII-I resulted in only a slight increase in the overall promoter activity (Fig. 10).

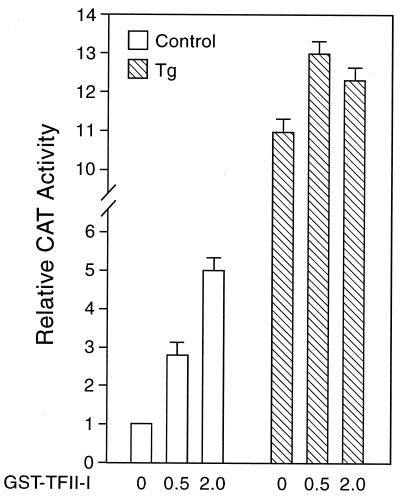

FIG. 10.

Effect of overexpression of TFII-I on the −98 ERSE-mediated CAT activity. The construct (−109/−74)MCAT was used as the reporter gene and was cotransfected with empty vector alone or increasing amounts (in micrograms) of the expression vector for GST–TFII-I (pEBGTFII-I) into COS cells. An expression vector for β-galactosidase activity was included to normalize for transfection efficiency. The amount of total DNA in each transfection was adjusted to be the same by addition of the empty vector in the reaction mixture. The transfected cells were either grown under normal culture conditions (open bars) or treated with Tg (hatched bars). The CAT activity in nonstressed cells transfected with the empty vector was set at 1. The relative promoter activities are shown with standard deviations.

The consensus tyrosine phosphorylation motif at residues 248 and 249 in TFII-I is critical for transcriptional activity of TFII-I in vivo but is dispensable for its ability to bind DNA (14). Activation of −98 ERSE by TFII-I also requires these sites, since mutation of the tyrosine residues at 248 and 249 to phenylalanine to generate the YY-FF mutant resulted in the loss of its ability to stimulate −98 ERSE (Fig. 11). In addition, mutation of the GGC motif of −98 ERSE (20), which is required for optimal ERSF and TFII-I binding, also eliminated the stimulatory effect of TFII-I (Fig. 11). The latter result showed that the target sequence of TFII-I is the ERSE and not the initiator element, since both the wild-type and the GGC mutant promoter constructs contain the identical minimal MMTV promoter. Collectively, these results show that TFII-I stimulation of −98 ERSE is dependent on the consensus tyrosine phosphorylation site of TFII-I as well as an intact GGC sequence within the N9 region of −98 ERSE.

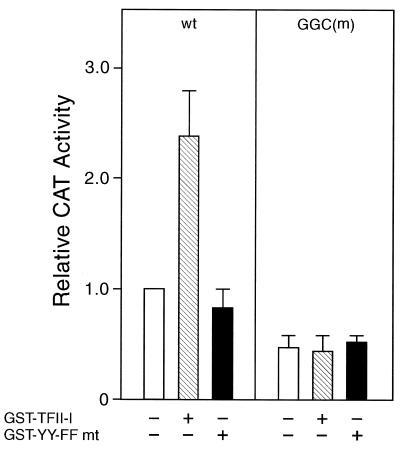

FIG. 11.

Requirements for TFII-I stimulation of −98 ERSE. COS cells were transfected either with (−109/−74)MCAT containing the wild-type (wt) rat grp78 −98 ERSE as the reporter gene (left panel) or with the GGC mutant [GGC(m)] of −98 ERSE as the reporter gene (right panel). The cells were transfected with either the empty vector, the wild-type GST–TFII-I, or the tyrosine phosphorylation site mutant (mt) of GST-TFII-I (YY-FF) as indicated. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

ATF6 stimulation of ERSE requires TFII-I.

In transient-cotransfection assays, overexpression of ATF6 stimulated −98 ERSE-mediated transcription by about 10-fold (Fig. 12A). To test for functional interaction between ATF6 and TFII-I, we tested the effect of a TFII-I antisense vector [TFII-I(N)/AS] on ATF6-mediated stimulation of the ERSE. As a negative control, parallel experiments were performed with the sense vector [TFII-I(N)/S] containing the same TFII-I subfragment encoding the amino-terminal third of the protein inserted in the sense orientation. Immunofluorescence analysis confirmed the ability of the antisense vector to reduce the level of endogenous TFII-I in the transfected cells, whereas the sense vector showed no such effect (Fig. 6B). Furthermore, neither the antisense vector nor the sense vector affected the expression level of HA-ATF6, as revealed by immunofluorescence (Fig. 6B) and confirmed by Western blot analysis of whole-cell lysates from transfected cells (data not shown). While overexpression of antisense or sense vector did not have any inhibitory effect on the basal promoter activity of (−109/−74)MCAT or the β-galactosidase activity included as transfection efficiency control, overexpression of the TFII-I antisense vector, but not the sense vector, suppressed ATF6 stimulation of −98 ERSE (Fig. 12A). Similarly, the TFII-I antisense vector was able to partially suppress Tg induction of −98 ERSE (Fig. 12B).

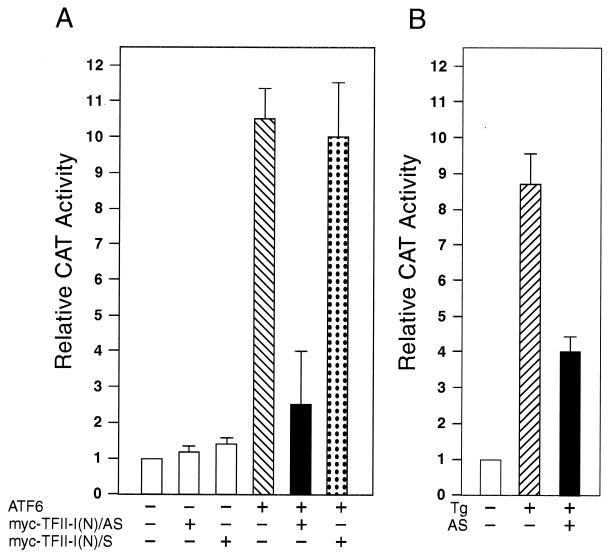

FIG. 12.

Suppression of ATF6 and Tg stimulation of −98 ERSE by antisense TFII-I. (A) COS cells were transfected with (−109/−74)MCAT as the reporter gene. The cells were cotransfected with either the empty CMV vector, pCGN-ATF6, or TFII-I(N)/AS or TFII-I(N)/S, alone and in combination, as indicated. The CAT activity in cells transfected with the empty CMV vector was set at 1. The relative promoter activities are shown with standard deviations. (B) COS cells were transfected with (−109/−74)MCAT as the reporter gene. The cells were either not treated or treated with Tg in the presence of the empty vector or the antisense TFII-I (AS) vector as indicated.

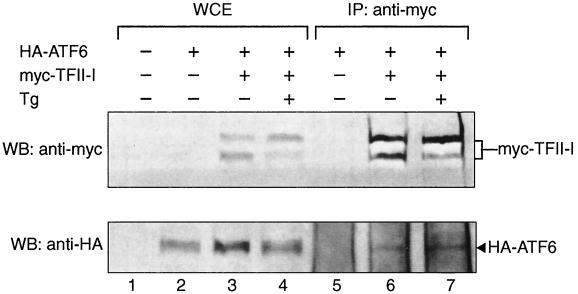

Next, we examined whether ATF6 and TFII-I form protein complexes in vivo. COS cells were cotransfected with HA-ATF6 and myc–TFII-I. Whole-cell extracts were prepared from nonstressed cells or cells treated with Tg. The expression of the epitope-tagged proteins was confirmed by Western blotting of the whole-cell extracts using monoclonal antibodies against the HA or the myc epitope (Fig. 13, lanes 1 to 4). The same whole-cell extracts were subjected to immunoprecipitation with the anti-myc antibody, followed by Western blotting with either the anti-HA or anti-myc antibody (Fig. 13, lanes 5 to 7). We observed that in cells cotransfected with TFII-I and ATF6, coimmunoprecipitation of TFII-I and ATF6 was detected. The immunoprecipitation of ATF6 was not due to background immunoprecipitation by the anti-myc antibody, since without coexpression of the myc-tagged TFII-I, ATF6 was not detected (Fig. 13, lane 5).

FIG. 13.

In vivo interaction of TFII-I with ATF6. COS cells were transfected with either the empty vector, HA-tagged-ATF6, or myc-tagged TFII-I, alone and in combination, as indicated. The cells were either not treated or treated with Tg for 16 h prior to preparation of the whole-cell extract (WCE) in NP-40 buffer. Fifty micrograms of the WCE was directly applied to SDS–8% PAGE for Western blots (WB) (lanes 1 to 4). To detect ATF6 and TFII-I interaction, 500 μg of the WCE was immunoprecipitated (IP) with 2 μg of anti-myc antibody (lanes 5 to 7). The immunoprecipitates were applied to denaturing SDS–8% PAGE and Western blotted with either anti-myc (upper panel) or anti-HA (lower panel) antibody. The positions of myc–TFII-I and HA-ATF6 are indicated.

DISCUSSION

Through the use of a series of chromatographic steps, ERSF was isolated from HeLa NE as a 125-kDa polypeptide eluted from the ERSE DNA affinity column. This protein was matched directly to the human transcription factor TFII-I through mass spectrophotometry of the peptides generated. Several independent criteria established TFII-I as ERSF, which was initially discovered as a novel stress-inducible complex binding to ERSE using gel shift assays (20). First, the size of TFII-I resembled that estimated from UV cross-linking of the ERSF complex to the ERSE. Second, two independent sources of antibodies directed specifically against TFII-I inhibited the formation of the ERSF complex binding to ERSE. Third, purified recombinant forms of TFII-I were able to bind ERSE, with electrophoretic mobilities identical to that of ERSF formed between HeLa NE and the ERSE probe. As shown for ERSF, recombinant TFII-I can bind the ERSEs from both the grp78 and ERp72 promoters. Fourth, overexpression of TFII-I can transactivate −98 ERSE in nonstressed cells. Although the magnitude of enhancement was moderate, the stimulatory effect of TFII-I is dependent on the GGC sequence motif within the ERSE that is required for optimal ERSF and TFII-I binding. Lastly, TFII-I is an interactive partner of ATF6, a potent stimulator of −98 ERSE activity; maximal ATF6 activation requires TFII-I.

TFII-I was first discovered as an initiator binding protein (19). Evidence has accumulated that it is a multifunctional protein with broad biochemical and biological activities. In addition to the 957-amino-acid form of TFII-I (Δ), there are three other alternatively spliced isoforms in human, referred to as α (977 amino acids), β (978 amino acids), and γ (998 amino acids). Of the four isoforms, the γ isoform is expressed predominantly, if not exclusively, in neuronal cells. The α isoform exhibits expression only in humans and not in mice. All four isoforms, when ectopically and individually expressed in COS cells, exhibit similar subcellular distributions, and they form stable complexes with each other either when coexpressed ectopically or when present endogenously in eukaryotic cells (3). The endogenous complex was preferentially located in the nucleus compared to the cytoplasm in a variety of transformed cell types. All four isoforms, when expressed in recombinant forms, exhibit similar DNA binding to both the Vβ initiator element and the upstream regulatory site of the c-fos promoter. Here we observed in EMSAs that in contrast to the Vβ initiator element, the β isoform of TFII-I appears to bind with higher affinity to the ERSE than the Δ isoform. The binding of TFII-I to stress-inducible and other promoters could resemble that of the “architectural” high-mobility-group proteins in that the binding site sequence is not highly rigid but contributes to the overall complex formation and stability. Under in vivo conditions and/or in the presence of other proteins that are part of the complex, the binding of TFII-I to its target sites could be further enhanced due to complex stabilization.

Through immunofluorescence we discovered that the staining pattern of TFII-I within the nuclei is unusual in that it is not uniformly distributed, suggesting association with a special subnuclear structure. Similar staining patterns were observed with NF-Y, which is also a binding protein of the ERSE (data not shown). Another unexpected finding is that in NIH 3T3 cells TFII-I itself is stress inducible. Other cell lines that exhibit increases in TFII-I level upon Tg stress include COS cells and the hamster fibroblast K12 cell line (20). However, an increase was not observed in 293T cells, which exhibit a high basal level of TFII-I. Previously, we and others have reported that ATF6 undergoes stress-inducible changes following ER stress (6, 9). One notable change is an increase in the level of ATF6 as grp78 induction reaches its maximal level several hours after the addition of the stress inducers. Here we report that TFII-I followed a similar pattern of induction, and this induction is due in part to the accumulation of TFII-I transcripts following Tg stress. While future studies will address the molecular mechanism for TFII-I induction, the discovery that the amount of TFII-I increases as cells undergo ER stress offers one explanation for the increase in ERSF binding to the ERSE in NEs prepared from ER-stressed cells (20).

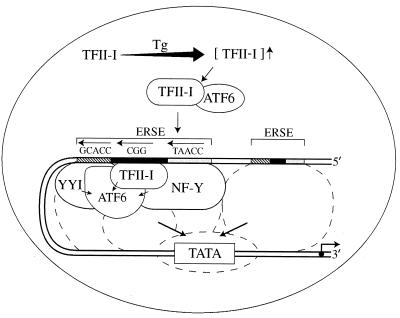

Our model for TFII-I induction of ERSE following Tg stress is summarized in Fig. 14. TFII-I is primarily a nuclear protein expressed at a basal level in nonstressed cells. Upon Tg treatment, the level of TFII-I increases. TFII-I can associate with ATF6, and TFII-I is required for maximal stimulation of ERSE by ATF6. These two factors, together with NF-Y and YY1, become part of a multiprotein complex binding onto the ERSE of the grp78 promoter. Components of this multiprotein complex have the potential to serve as bridging proteins between the upstream ERSE regulatory elements and the basal transcription machinery. Acting synergistically, they promote activation of the grp78 promoter in response to Tg stress. In support of the role of TFII-I as a linker protein promoting formation of multiprotein complexes, ATF6 has been shown to interact with the serum response factor SRF, which binds to the serum response element required for the regulated expression of the c-fos promoter (29). Interestingly, TFII-I can also form in vivo protein-protein complexes with SRF (8). Here we identify ATF6 as a new interactive partner of TFII-I. Thus, TFII-I might under some conditions serve as a linker protein between ATF6 and SRF towards the activation of the c-fos promoter. Under other conditions, TFII-I complexes with other proteins which exert influence on other genes.

FIG. 14.

Model for TFII-I action on ERSE following Tg stress. TFII-I is a nuclear protein expressed at a basal level in nonstressed cells. Upon Tg treatment, the level of TFII-I increases. TFII-I can associate with ATF6. These two factors become part of a multiprotein complex binding onto the ERSE of the grp78 promoter. TFII-I, NF-Y, and YY1 serve as coactivators for ATF6. Other Tg-induced modifications of the transcription factors may also occur. Components of this multiprotein complex have the potential to serve as bridging proteins between the upstream ERSE regulatory elements and the basal transcription machinery. Acting synergistically, they promote activation of the grp78 promoter in response to Tg stress.

The model proposed for TFII-I action does not preclude stress-induced posttranslational modifications of TFII-I and other ER stress-inducible complexes binding to the ERSE. Recently, using resin pull-down assays, a complex consisting of NF-Y and a heterodimer of proteolytically cleaved ATF6 binding to the adjacent CCACG motif has been observed (27). Whereas the cleaved forms of ATF6 in Tg-treated cells are transient and occur in very small amounts (26), TFII-I is stable and abundant in stressed cells and could contribute to the sustained transcription of the GRP promoter in Tg-treated cells. TFII-1 is phosphorylated in vivo at serine, threonine, and tyrosine residues (14). TFII-1 can associate with Bruton's tyrosine kinase, which facilitates TFII-1 tyrosine phosphorylation (15, 25). Our finding that the consensus tyrosine phosphorylation site at residues 248 and 249 is required for TFII-I stimulation of the ERSE is consistent with the previous finding that this site is required for the transcription-activating property of TFII-I (14). Further, since ER stress induction of grp78 can be suppressed by genistein, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor, we have postulated that a signaling pathway mediated by tyrosine kinases could be involved in the induction process of grp78 (28). The discoveries that TFII-I is ERSF and that the tyrosine phosphorylation site of TFII-I is required for its stimulatory activity on the ERSE provide the first link that molecularly connects the tyrosine kinase transduction pathway to a transcription factor implicated in grp78 induction. Thus, TFII-I could be a target for tyrosine phosphorylation modification and in such a capacity integrate signals from ER stress to nuclear gene activation. TFII-I isoforms are generated by alternative splicing (3), a mechanism invoked by yeast to regulate the unfolded protein response (4). Further, the different TFII-I isoforms may be complexed with distinct proteins in a constitutive state. Upon stress signaling, they might complex with each other to change either the amplitude or the duration of signaling. Alternatively, each isoform can receive independent signals and act accordingly. Whether they act coordinately or independently, they increase the combinatorial possibilities of activating target genes.

The discovery that TFII-I is ERSF also raises the issue of whether TFII-I is a general regulator of the ER stress-induced genes. Among the ERSEs of ER stress-inducible promoters identified thus far, the N9 regions of a subset of ERSEs belonging to mammalian grp78, grp58, ERp72, and SERCA2 genes are strikingly rich in GC sequence, whereas this feature is not prominent among ERSE-like motifs from invertebrates, plants, and fungi (26). The triplet GGC sequence occurs once and sometimes twice within the N9 regions of the mammalian ERSEs. The redundancy of the GGC motif within −61 ERSE of human grp78 could explain why single base substitutions might not be effective in eliminating TFII-I interaction and stimulation (26). For grp78 and ERp72, site-directed mutagenesis of the single GGC triplet without affecting the other features of the tripartite structure of the ERSE resulted in substantial loss of ER stress inducibility (12, 20). This, coupled with the high degree of conservation of the entire N9 sequence within each set of ERSEs across species, strongly suggests that N9 is functional and not simply a random spacer region within the ERSE. Our results predict that TFII-I regulates a subset of ER stress-induced genes as a component of the stress response perhaps unique to mammals and vertebrate animals. Since the induction of ER stress-responsive genes is strictly dependent on the integrity of the tripartite structure of ERSE and requires at least two other transcription factors, NF-Y and ATF6, as coactivators (9, 12, 27, 28), we envision that only a subset of cellular promoters containing the TFII-I binding site will be activated by ER stress. Further investigations into the molecular mechanisms whereby TFII-I regulates the transcription of ER stress genes and other promoters bearing the TFII-I binding site will address these issues.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are greatly indebted to Ebrahim Zandi for helpful discussion and assistance with protein fractionation. We thank Stephen Desiderio for TFII-I expression vectors and antibodies, Ron Prywes for the ATF6 expression vector, and Mengyin Liu for assistance with Western blotting. The microsequencing was performed by Nicholas Sherman at the University of Virginia Biomedical Research Facility.

The University of Virginia Biomedical Research Facility is funded by a grant from the University of Virginia Pratt Committee. The microscopy was performed at the Electron Microscopy Core Facility at the Doheny Eye Institute, University of Southern California, supported by NEI/NIH core grant EY03040 and the USC/Norris Cancer Center. This work was supported by Public Health Service grants CA27607 from the NCI, National Institutes of Health, to A.S.L. and AI45150 from NIH to A.L.R.

REFERENCES

- 1.Caspersen C, Pedersen P S, Treiman M. The sarco/endoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase 2b is an endoplasmic reticulum stress-inducible protein. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:22363–22372. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheriyath V, Novina C D, Roy A L. TFII-I regulates Vβ promoter activity through an initiator element. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4444–4454. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.8.4444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheriyath V, Roy A L. Alternatively spliced isoforms of TFII-I. Complex formation, nuclear translocation, and differential gene regulation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26300–26308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002980200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foti D M, Welihinda A, Kaufman R J, Lee A S. Conservation and divergence of the yeast and mammalian unfolded protein response. Activation of specific mammalian endoplasmic reticulum stress element of the grp78/BiP promoter by yeast Hac1. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:30402–30409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.43.30402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grueneberg D A, Henry R W, Brauer A, Novina C D, Cheriyath V, Roy A L, Gilman M. A multifunctional DNA-binding protein that promotes the formation of serum response factor/homeodomain complexes: identity to TFII-I. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2482–2493. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.19.2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haze K, Yoshida H, Yanagi H, Yura T, Mori K. Mammalian transcription factor ATF6 is synthesized as a transmembrane protein and activated by proteolysis in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol Biol Cell. 1999;10:3787–3799. doi: 10.1091/mbc.10.11.3787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadonaga J T. Purification of sequence-specific binding proteins by DNA affinity chromatography. Methods Enzymol. 1991;208:10–23. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)08004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim D W, Cheriyath V, Roy A L, Cochran B H. TFII-I enhances activation of the c-fos promoter through interactions with upstream elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3310–3320. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li M, Baumeister P, Roy B, Phan T, Foti D, Luo S, Lee A S. ATF6 as a transcription activator of the endoplasmic reticulum stress element: thapsigargin stress-induced changes and synergistic interactions with NF-Y and YY1. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:5096–5106. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.14.5096-5106.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li W W, Alexandre S, Cao X, Lee A S. Transactivation of the grp78 promoter by Ca2+ depletion. A comparative analysis with A23187 and the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12003–12009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li W W, Hsiung Y, Zhou Y, Roy B, Lee A S. Induction of the mammalian GRP78/BiP gene by Ca2+ depletion and formation of aberrant proteins: activation of the conserved stress-inducible grp core promoter element by the human nuclear factor YY1. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:54–60. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marcus N, Green M. NF-Y, a CCAAT box-binding protein, is one of the trans-acting factors necessary for the response of the murine ERp72 gene to protein traffic. DNA Cell Biol. 1997;16:1123–1131. doi: 10.1089/dna.1997.16.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Novina C D, Cheriyath V, Denis M C, Roy A L. Methods for studying the biochemical properties of an Inr element binding protein: TFII-I. Methods. 1997;12:254–263. doi: 10.1006/meth.1997.0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novina C D, Cheriyath V, Roy A L. Regulation of TFII-I activity by phosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33443–33448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novina C D, Kumar S, Bajpai U, Cheriyath V, Zhang K, Pillai S, Wortis H H, Roy A L. Regulation of nuclear localization and transcriptional activity of TFII-I by Bruton's tyrosine kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:5014–5024. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.7.5014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roy A L, Carruthers C, Gutjahr T, Roeder R G. Direct role for Myc in transcription initiation mediated by interactions with TFII-I. Nature. 1993;365:359–361. doi: 10.1038/365359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roy A L, Du H, Gregor P D, Novina C D, Martinez E, Roeder R G. Cloning of an inr- and E-box-binding protein, TFII-I, that interacts physically and functionally with USF1. EMBO J. 1997;16:7091–7104. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.23.7091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roy A L, Malik S, Meisterernst M, Roeder R G. An alternative pathway for transcription initiation involving TFII-I. Nature. 1993;365:355–359. doi: 10.1038/365355a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roy A L, Meisterernst M, Pognonec P, Roeder R G. Cooperative interaction of an initiator-binding transcription initiation factor and the helix-loop-helix activator USF. Nature. 1991;354:245–248. doi: 10.1038/354245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roy B, Lee A S. The mammalian endoplasmic reticulum stress response element consists of an evolutionarily conserved tripartite structure and interacts with a novel stress-inducible complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:1437–1443. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.6.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Roy B, Li W W, Lee A S. Calcium-sensitive transcriptional activation of the proximal CCAAT regulatory element of the grp78/BiP promoter by the human nuclear factor CBF/NF-Y. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28995–29002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.28995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shapiro D J, Sharp P A, Wahli W W, Keller M J. A high-efficiency HeLa cell nuclear transcription extract. DNA. 1988;7:47–55. doi: 10.1089/dna.1988.7.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tillman J B, Mote P L, Walford R L, Spindler S R. Structure and regulation of the mouse GRP78 (BiP) promoter by glucose and calcium ionophore. Gene. 1995;158:225–229. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00083-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang Y, Shen J, Arenzana N, Tirasophon W, Kaufman R J, Prywes R. Activation of ATF6 and an ATF6 DNA binding site by the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27013–27020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003322200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang W, Desiderio S. BAP-135, a target for Bruton's tyrosine kinase in response to B cell receptor engagement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:604–609. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshida H, Haze K, Yanagi H, Yura T, Mori K. Identification of the cis-acting endoplasmic reticulum stress response element responsible for transcriptional induction of mammalian glucose-regulated proteins. Involvement of basic leucine zipper transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33741–33749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshida H, Okada T, Haze K, Yanagi H, Yura T, Negishi M, Mori K. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced formation of transcription factor complex ERSF including NF-Y (CBF) and ATF6α/β that activates the mammalian unfolded protein response. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1239–1248. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1239-1248.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou Y, Lee A S. Mechanism for the suppression of the mammalian stress response by genistein, an anticancer phytoestrogen from soy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:381–388. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.5.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu C, Johansen F E, Prywes R. Interaction of ATF6 and serum response factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4957–4966. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.4957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]