Abstract

Background:

Unintended pregnancy among women with short-inter-pregnancy intervals remains common. Women’s attendance at the 4–6 week postpartum visit, when contraception provision often occurs, is low, while their attendance well-baby visits is high. We aimed to evaluate if offering co-located contraceptive services to mothers at well-baby visits increases use of long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) at 5 months postpartum compared to usual care in a randomized controlled trial.

Methods:

Women with infants aged ≤4.5 months who were not using a LARC method and had not undergone sterilization were eligible. Generalized linear models were used to estimate risk ratios (RR). Likability and satisfaction of the contraception visit were assessed.

Results:

Between January 2015 and January 2017, 446 women were randomized. LARC use at 5 months was 19.1% and 20.9% for the intervention and control groups, respectively, and was not significantly different after controlling for weeks postpartum (RR=0.85, 95% CI 0.59–1.23). Uptake of the co-located visit was low (17.7%), but the concept was liked; insufficient time to stay for the visit was the biggest barrier to uptake. Women who accepted the visit were more likely to use a LARC method at 5 months compared to women in the control group (RR=1.97, 95% CI 1.26–3.07).

Conclusion:

Women perceived co-located care favorably and LARC use was higher among those who completed a visit; however, uptake was low for reasons including inability to stay after the infant visit. Intervention effects were possibly diluted. Future research should test a version of this intervention designed to overcome barriers that participants reported.

Introduction

Postpartum women experience high rates of unintended pregnancy, with rates documented up to 44% within the first postpartum year (Bryant, Haas, McElrath, & McCormick, 2006; Kabakian‐Khasholian & Campbell, 2005; Kershaw et al., 2003; Weir et al., 2011). Pregnancies occurring within a short inter-pregnancy interval, defined as less than 18 months after delivery, have been associated with increased risks of preterm birth, low birth weight (Grisaru-Granovsky, Gordon, Haklai, Samueloff, & Schimmel, 2009; Kwon, Lazo-Escalante, Villaran, & Li, 2012), and preeclampsia (Trogstad, Eskild, Magnus, Samuelsen, & Nesheim, 2001). Almost one third (29%) of second-order pregnancies in the United States occur within a short inter-pregnancy interval (Thoma, Copen, & Kirmeyer, 2016). Use of the most effective methods of contraception, such as long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), could significantly reduce the risk of experiencing an unintended short inter-pregnancy interval (White, Teal, & Potter, 2015). However, research has found that few postpartum women who plan to use LARC receive that method (Harney, Dude, & Haider, 2017; Potter et al., 2017; Potter et al., 2016; Tang, Dominik, Re, Brody, & Stuart, 2013).

For women who do not receive contraception immediately after delivery, provision of postpartum contraception is typically limited to the traditional six-week postpartum visit. However, attendance rates at the postpartum visit are low, with an estimated 49–63% of women attending their six-week visit (Rankin et al., 2016; Thiel de Bocanegra et al., 2017); thus, many women miss the opportunity to receive timely contraception. Provision of contraception, including placement of immediate postpartum LARC (IPPLARC), prior to hospital discharge is promoted as an option to ensure access to contraception (Moniz, Chang, Heisler, & Dalton, 2017). Prenatal contraception counselling can play a key role in educating women with regard to IPPLARC; however, because system-level changes are required for IPPLARC provision such as additional insurance coverage, provider training, and stocking LARC devices in hospital pharmacies, many barriers to implementation persist (Hofler et al., 2017). Although widespread access to IPPLARC is promising, current access is limited, thus, additional strategies are needed for optimizing provision of contraception for postpartum women. Lastly, even in clinical environments where care is provided to both mothers and infants (i.e., family medicine clinic), the care is rarely coordinated. Continuity of care for families with the same primary care clinician or practice has been associated with improved outcomes, including increased use of preventive services, better adherence to clinician recommendations, and lower total costs, although this model of care has not been well studied in the context of maternal and child care delivery (O’Malley, Rich, Maccarone, DesRoches, & Reid, 2015).

Linking contraceptive services with infant care is one such strategy to optimize provision of contraception for postpartum women. Since the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends normal infants have well-baby visits at 3–5 days post hospital discharge and by one month of age (both of which are prior to the standard postpartum visit) and four more visits before one year (i.e., two, four, six, and nine months) (Workgroup, Practice, & Medicine, 2017), the newborn care visit is an opportunity to reach more women than are reached through the current standard postpartum visit model of care. Additionally, there is a high rate of attendance at infant well-baby visits (Ghandour et al., 2018). In 2009–2011, 93% of women reported that their infant had a well-baby visit within one week of birth, and in 2011–2012, over 90% of U.S. infants attended regular well-baby visits during the first year of life (CDC, 2011).

Moreover, there is also precedent for linking maternal health care to infant care. Addressing maternal health needs during a pediatric visit is now standard practice for pediatricians with respect to screening for postpartum depression. Evidence supports findings that postpartum depression screening is reliable and feasible in the pediatric setting (Freeman et al., 2005), which led to national systematic changes to include postpartum depression screening at the well-baby visit. Furthermore, research efforts are beginning to study the feasibility of management of postpartum depression within pediatric care (Van Der Zee-Van et al., 2017). Routine infant health care visits represent the most regular contact new mothers have with the health care system (Olin et al., 2016), making it an ideal venue for implementing timely postpartum contraception care.

Lastly, contraception counseling in conjunction with infant care has been found to be highly acceptable to postpartum women and pediatricians (Caskey et al., 2016; Henderson et al., 2016; Kumaraswami et al., 2018). However, research to date has not evaluated the impact of provision of postpartum contraception coupled with infant care.

This study builds on previous literature by evaluating contraception counseling and provision in conjunction with an infant’s care. Our objectives were two-fold: 1) to measure if a novel system-level intervention offering contraceptive counseling and provision, in conjunction with an infant’s well-baby visit during the first four months of life, increases postpartum women’s utilization of LARC, compared to usual care; and, 2) to describe patient-centered facilitators and barriers to implementing a novel system-level intervention at the well-baby visit. The first objective assumes that increased LARC utilization indicates improved access; the overarching goal is to assure access to preferred methods of postpartum contraception rather than to reach a particular level of LARC use.

Materials and Methods

Trial Design and Setting

This is a single-site, randomized controlled trial. The trial took place in an urban academic medical center serving a predominantly publicly-insured patient population. The University of Illinois at Chicago’s (UIC) review board approved this study on September 26, 2014.

Participants

All enrollment was conducted between January 2015 and January 2017. Women bringing their infants in for care at the general pediatric clinic within the academic medical center were approached. Women were asked if they wanted to participate voluntarily in a study about postpartum contraception. A woman was eligible if: 1) her infant was four and a half months of age or less; 2) she had not previously received a LARC method or permanent sterilization; 3) she was not currently pregnant; 4) she was a patient at the medical center or affiliated clinic to allow for electronic medical record (EMR) review; and 5) she spoke English or Spanish. Eligible women who agreed to participate then gave written informed consent for study participation, including access to their EMR for review. Participants were blinded to the study objective regarding LARC use until the end of their participation in the study, and the study team was blinded for follow-up data collection. Blinding of participants about the study objective was done to avoid any sense of coercion to choose a LARC method among the intervention group or influence control participants to obtain a LARC method by virtue of being told about the study objective. Randomization occurred after participants were screened for eligibility and consented.

Randomization Procedure

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the two study arms following simple randomization procedures performed by the study’s epidemiologist (KR) using a random number generator in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute: Cary, NC). Random assignment was implemented using the randomization module in the REDCap electronic data capture tool. Participants randomized to the intervention arm were offered co-located contraception services after their well-baby visit, while participants randomized to the control arm received no additional contraception care at baseline and went on to get usual postpartum care.

Intervention

All women assigned to the intervention group were offered a same-day contraception visit with a Certified Nurse Midwife or Obstetrician/Gynecologist (Ob/Gyn) at the medical center’s women’s health clinic, which is in the same building as the pediatric clinic. If participants could not stay for a same-day visit, they were offered a visit on another day in conjunction with their infant’s care. Participants who accepted the contraceptive visit were provided comprehensive contraception counseling, screened for any medical contraindications. Payment for the visit and contraception were through the participant’s insurance coverage and billed per usual protocol for the services delivered. LARC devices were provided using Title X family planning grant at the institution for those women who did not have insurance coverage for contraception services for women in both the intervention arm of the study and the control arm. All methods of contraception were provided, including LARC, at no cost to participants. The visit procedures, documentation, and billing occurred per usual clinical practices.

Data Collection

Study data were collected and managed using REDCap, a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies. All enrolled participants completed a baseline survey in a private space in the general pediatric clinic; the survey included demographic data, weeks postpartum, past and current contraceptive use, pregnancy intention, method of infant feeding, prenatal care attendance, delivery method, and postpartum visit attendance. Women who were randomized to the intervention arm and accepted the contraception visit completed a satisfaction survey at the end of the visit. Intervention group participants who declined the contraception visit completed a survey assessing their reasons for declining. All study participants received a follow-up phone call at five months postpartum to assess contraceptive use, attendance at a postpartum visit, and current pregnancy status. Finally, a trained research assistant reviewed all participants’ EMRs for primary and secondary outcome data.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was use of a LARC method by five months postpartum. To minimize missing data, we collected data by both 5-month phone interview and EMR review. The composite dichotomous variable was created to indicate evidence of uptake of a LARC method from either data source.

Secondary outcomes included receipt of any contraceptive method classified by WHO Tiers of Efficacy or use of emergency contraception or pregnancy by 5-month follow-up. WHO Tiers include: Tier 1 highly effective methods (LARC and permanent sterilization), Tier 2 moderately effective methods (oral contraceptive pills, vaginal ring, patch, shot), and Tier 3 least effective methods (barrier methods such as male condoms). If there was a discrepancy between the method(s) used between the phone interview and the medical record, then the most effective method was chosen. If the two methods did not vary by effectiveness, then the most recent method was chosen. It is common clinical practice to offer women on Depomedroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) a LARC method and also common for women who choose DMPA to transition to a LARC method at a later time. Thus, we included women who had received DMPA in the intervention.

The second aim of the study included only women randomized to the intervention arm of the study. Participants were asked to complete a satisfaction survey after completing their contraceptive visit or a survey after refusing the contraceptive services. Surveys addressed women’s preference or likability of the co-located contraceptive care concept using a four point Likert scale. A series of close-ended questions assessed their reasons for: 1) liking or not liking the offered co-located care; 2) choosing to receive services or not receive services. We also assessed their likelihood of choosing to receive co-located care, in order to assess other thoughts about the intervention. Women who accepted the intervention were asked questions assessing their satisfaction and comfort with the counseling and contraception care provided during the visit. We also assessed their willingness to recommend the intervention to a friend.

Sample Size

For women delivering at UIC, we estimated a baseline rate of 15% of obtaining LARC by 5 months postpartum. This relatively high estimate of postpartum LARC use is due to UIC’s providers placing a priority on educating patients about safety and efficacy of all contraceptive options and removing barriers to access to LARC use, specifically for their medically complicated patients. We assumed our intervention could improve LARC uptake from 15% to 28% (Relative Risk = 1.87). Based on this assumption, we calculated a sample size of 448 total participants to achieve 80% power at alpha=0.05 and account for a 30% attrition rate at five months. The primary outcome analysis was intention-to-treat and involved all patients who were randomized.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4, following a predetermined statistical analysis plan. Initial analyses assessed for the equivalency of study groups on baseline characteristics using chi-squared tests to compare proportions for categorical variables and t-tests to compare means for continuous variables. Risk ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the primary (LARC uptake at 5 months postpartum) and secondary (any use of Tier 1, Tier 2, or Tier 3 contraceptive or emergency contraception, or pregnancy, at 5 months postpartum) outcomes using a generalized linear model that adjusted for baseline characteristics not equivalent between groups.

Results

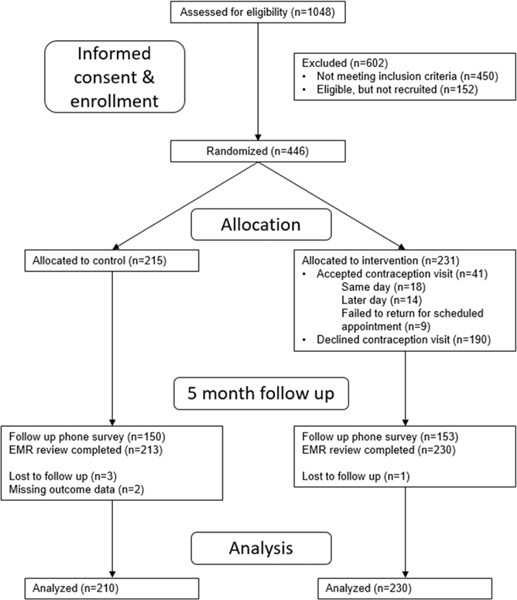

Of the 1,048 women assessed for eligibility for participation in the trial, 446 total women were randomized to the control (n=215) or intervention (n=231) group, Figure 1. Reasons for exclusion included women having an infant older than 4.5 months of age (n=183), having already participated in the study (n=47), having had a tubal ligation after delivery (n=84), already having a LARC method (n=103), not being a patient at the medical center (n=140), and not speaking English or Spanish (n=31). The 152 participants who were eligible but did not participate included individuals who declined participation as well as those who were called to their pediatric visit and were lost before completion of enrollment.

Figure 1:

Study flow diagram.

Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups except there was a significant difference in the mean number of weeks postpartum between the intervention and control groups (4.5 vs. 5.2 weeks, respectively). Therefore, all analyses controlled for the number of weeks postpartum. There was also a significant difference in the percentage of women who had a postpartum visit, but as this is correlated with weeks postpartum, only weeks postpartum was controlled for in later analyses.

Aim 1

Of the 231 women randomized to the intervention, 41 (17.8%) accepted a co-located contraception visit either the same day or scheduled with a future well-baby visit. Of the women who accepted the intervention, 18 (43.9%) had a same day visit, 14 (34.1%) scheduled and attended a future visit within 5 months, and 9 (22.0%) scheduled a future visit but did not return. Fifteen women received a LARC method at their intervention contraception visit.

Based on both phone and EMR data, six patients had missing data for the primary outcome. The intent-to-treat analysis showed that LARC use at five months postpartum was similar for both randomized groups (19.1% for intervention, 20.9% for control), with no significant difference between the groups even after controlling for weeks postpartum at time of enrollment (RR: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.59, 1.23) (Table 2). Additionally, there were no significant differences for the secondary outcomes between the randomized groups. Specifically, contraception use of any type (Tier 1, 2, or 3) was similar, as were pregnancy rates by five months between control and intervention groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes by Group

| Outcomes at 5 Months Postpartum | Intervention (n=230) | Control (n=210) | p-value | Adjustedc Risk Ratio (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| LARC Use a | |||||

| Any: | Yes | 44 (19.1%) | 44 (20.9%) | 0.63 | 0.85 (0.59, 1.23) |

| Method Type: | IUD | 24 (10.4%) | 27 (12.9%) | 0.43 | |

| Implant | 20 (8.7%) | 17 (8.1%) | 0.82 | ||

| Tier 2 Contraceptive Use a | |||||

| Any: | Yes | 99 (43.0%) | 75 (35.7%) | 0.12 | 1.23 (0.97, 1.56) |

| Method Type: | Pill | 50 (21.7%) | 31 (14.8%) | 0.06 | |

| Patch | 8 (3.5%) | 3 (1.4%) | 0.17 | ||

| Depo Shot | 38 (16.5%) | 38 (18.1%) | 0.66 | ||

| Ring | 3 (1.3%) | 3 (1.4%) | 0.91 | ||

| Pregnancy b | Yes | 4 (1.8%) | 2 (1.0%) | 0.49 | 1.58 (0.29, 8.50) |

6 participants missing

27 participants missing

Adjusted for weeks postpartum, which was non-equivalent across groups

Due to the low uptake of the contraceptive visit within the intervention group, we conducted a per protocol analysis to determine if LARC use differed by acceptance or decline of the contraceptive visit compared to the control group. LARC use at 5 months was significantly higher (46.9%, crude RR=2.24, 95% CI 1.42–3.51) for women who had a co-located visit compared to the control group, and this remained significant after adjusting for weeks postpartum (adjusted RR=1.97, 95% CI 1.26–3.07) (Table 2). Out of 15 women reporting LARC use at 5 months in the intervention group, 13 received it during a co-located visit. LARC use at 5 months was much lower for women who declined the visit (12.6%), corresponding to a 43% lower rate of LARC use compared to the control group after adjusting for weeks postpartum (adjusted RR=0.57, 95% CI 0.35–0.92). There was no significant difference in LARC use at 5 months for women who accepted but did not return for their scheduled visit (22.6%). Two out of the 13 women who received LARC from the intervention (both received an implant) switched to a Tier 2 form of contraception by the 5 month follow-up due to undesirable side effects from the implant.

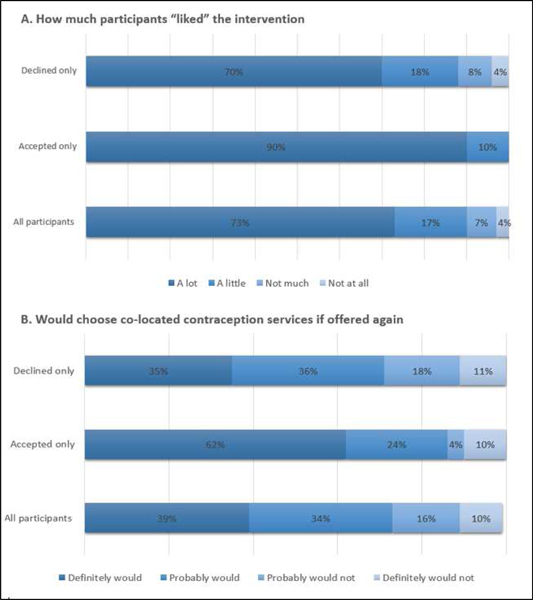

Aim 2

Of the 222 women randomized to the intervention and who completed a survey, perceptions of the offered contraceptive visit linked with well-baby care were high, in spite of low uptake. As seen in Table 3, when asked how much they liked the idea of a contraceptive visit linked with well-baby care, the majority of participants, regardless of uptake, rated liking the concept “a lot” or “a little. Similarly, the majority of women “definitely would” or “probably” would choose to receive the linked services again if offered in the future, although there was a significant difference between those who accepted and those who declined the contraceptive visit.

Table 3.

Likability and satisfaction of co-located contraception services with infant care

| Overall (n=222) | Accepted Intervention (n=32) | Declined Intervention (n=190) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liked the intervention (n=194) | A lot | 141 | 26 (89.7%) | 115 (69.7%) | 0.12 |

| A little | 33 | 3 (10.3%) | 30 (18.2%) | ||

| Not much | 13 | 0 | 13 (7.9%) | ||

| Not at all | 7 | 0 | 7 (4.2%) | ||

| What was liked: | Missed postpartum follow up | 5 | 2 (6.3%) | 3 (1.6%) | 0.10 |

| Not planning on attending postpartum follow up | 3 | 1 (3.1%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0.35 | |

| In need of birth control | 22 | 13 (40.6%) | 9 (4.7%) | <.0001 | |

| Convenient | 112 | 19 (59.4%) | 93 (49.0%) | 0.28 | |

| Other | 4 | 2 (6.3%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0.04 | |

| None of the above | 59 | 1 (3.1%) | 58 (30.5%) | 0.001 | |

| What was not liked: | No time to stay longer | 42 | 1 (3.1%) | 41 (21.6%) | 0.01 |

| Too tired after baby’s visit | 13 | 3 (9.4%) | 10 (5.3%) | 0.36 | |

| Uncomfortable seeing new provider | 9 | 0 (0.0%) | 9 (4.7%) | 0.21 | |

| Children were there | 7 | 0 (0.0%) | 7 (3.7%) | 0.27 | |

| Worried about insurance | 3 | 1 (3.1%) | 2 (1.1%) | 0.35 | |

| Othera | 20 | 1 (3.1%) | 19 (10.0%) | 0.21 | |

| None of the above | 116 | 24 (75.0%) | 92 (48.4%) | 0.005 | |

| Choose to use these services again (n=181) | Definitely would | 71 | 18 (62.1%) | 53 (34.9%) | 0.03 |

| Probably would | 62 | 7 (24.1%) | 55 (36.2%) | ||

| Probably would not | 29 | 1 (3.5%) | 28 (18.4%) | ||

| Definitely would not | 19 | 3 (10.3%) | 16 (10.5%) | ||

| Reasons for declining intervention: (n=188) | No time to stay longer | 40 (21.3% | |||

| Too tired to stay longer | 6 (3.2%) | ||||

| Uncomfortable seeing new provider | 9 (4.8%) | ||||

| Children were present | 4 (2.1%) | ||||

| Worried about insurance coverage | 3 (1.6%) | ||||

| Do not want birth control | 33 (17.6%) | ||||

| Already have birth control | 48 (25.5%) | ||||

| Already have a scheduled PP visit | 50 (26.6%) | ||||

| Other | 7 (3.7%) | ||||

| None of the above | 3 (1.6%) | ||||

| Satisfaction with counseling (n=30) | Very satisfied | 30 (100.0%) | |||

| Somewhat satisfied | 0 | ||||

| Not very satisfied | 0 | ||||

| Not at all satisfied | 0 | ||||

| Comfortable with BC at this visit (n=30) | Very uncomfortable | 29 (96.7%) | |||

| Somewhat comfortable | 1 (3.3%) | ||||

| Somewhat uncomfortable | 0 | ||||

| Very uncomfortable | 0 | ||||

| Convenience of visit (n=30) | Very convenient | 26 (86.7%) | |||

| Somewhat convenient | 3 (10.0%) | ||||

| Neither convenient nor inconvenient | 1 (3.3%) | ||||

| Somewhat inconvenient | 0 | ||||

| Very inconvenient | 0 | ||||

| Time spent on counseling (n=30) | Too little time | 0 | |||

| Just the right amount of time | 27 (90.0%) | ||||

| A little too much time | 1 (3.3%) | ||||

| Way too much time | 2 (6.7%) | ||||

| Received new BC method today (n=30) | Yes | 21 (70.0%) | |||

| No | 9 (30.0%) | ||||

| Recommend to a friend (n=28) | Definitely would | 18 (64.2%) | |||

| Probably would | 5 (17.9%) | ||||

| Probably would not | 0 | ||||

| Definitely would not | 5 (17.9%) | ||||

| Rating of quality of care (n=30) | Excellent | 24 (80.0%) | |||

| Very good | 4 (13.3%) | ||||

| Good | 2 (6.7%) | ||||

| Fair | 0 | ||||

| Poor | 0 |

Other reasons for not liking the intervention that participants wrote in: uninterested or unsure about birth control (n=8); already have birth control (n=6); already have appointment scheduled (n=5); do not like having to wait (n=1).

With regards to specific reasons why women liked the linked contraceptive visit, the most commonly cited reason was convenience (50%), followed by no specific reason (27%), and 10% stated they were in need of birth control. Among those who reported a need for birth control, there was a significant difference between women who accepted the contraceptive visit and women who declined it (40% and 4.7% respectively, p<.0001).

Among only those women who declined the contraceptive visit, the most common reasons for not accepting contraceptive services included: already having a postpartum visit scheduled (26.6%, n=50), already having a method of birth control (25.5%, n=48), did not have time to stay after pediatric visit (21.5%, n=40), and did not want birth control (17.6%, n=33). Other responses such as being tired, not being comfortable seeing a new provider, and having other children present were selected by less than 5% of participants. Length of the pediatric visit was observed for the last 144 participants, and almost half had pediatric visit lengths of 1.5 to 2.5 hours.

Among only women who accepted the contraceptive visit, satisfaction ratings were very high and the majority (70%) of women who attended a visit received a new method of birth control. As seen in Table 3, 80% or more of women answered questions assessing satisfaction with the most positive response. When asked if they would recommend a linked contraceptive visit with well-baby care to a friend, 64% of women chose “definitely would” and 18% chose “probably would.” When asked if there was anything that would make it easier to get contraceptive counseling and birth control at the same time as their infant’s visit, the most common suggestion was scheduling the co-visits together ahead of time.

Discussion

This study tested the novel approach of offering postpartum contraception at the well-baby visit, and its influence on rates of postpartum contraception uptake. Similar to previous research assessing acceptability of contraception counseling at the time of pediatric care (Caskey et al., 2016; Fagan, Rodman, Sorensen, Landis, & Colvin, 2009; Kumaraswami et al., 2018), data from our second aim demonstrate maternal support for the concept of co-located contraceptive care. However, the intervention was not found to increase postpartum LARC use among the intervention group, compared to control participants. This null finding could be related to a number of factors. First, this finding could result from a dilution of the intervention effect due to the low uptake of the contraception visit. The per protocol analysis revealed that women who completed the co-located visit were actually twice as likely as the control group to use LARC at 5 months. Second, this finding could be influenced by a higher baseline postpartum LARC use rate at this medical center than was accounted for in the sample size. Recent data on postpartum LARC use suggest that LARC use was increasing nationally during the time of our study (Dee et al., 2017; Law, Yu, Wang, Lin, & Lynen, 2017), and therefore could have influenced our results. Unfortunately, we do not have baseline data on postpartum LARC use for the institution where this study took place; however, we suspect it to be higher than the typically rates as there is a strong family planning presence at this institution.

We must further examine the low rate of uptake of the contraceptive visit, in spite of participants having favorable ratings of the idea. We believe this finding is likely influenced by the long waiting times women experienced for pediatric visits. It was not uncommon for women to spend 1.5 to 2.5 hours in the clinic for their pediatric visits, which could have caused women who would have otherwise been interested in the intervention to decline. Data from our second aim supports this, as one in five women who declined the intervention indicated they did not have additional time to stay as a reason for declining the intervention. Furthermore, due to the study design, women were offered the intervention at the time of a previously scheduled well-baby visit with no advance notice about the option for co-located contraception services. Therefore, they had little opportunity to arrange their schedules accordingly (e.g., transportation, childcare arrangements, etc.), and this likely accounts for lower uptake of the intervention. Also, a majority of women who declined the contraception visit gave various reasons suggesting they did not need this type of visit (did not want birth control, already had birth control, or already had a planned postpartum visit). Co-located care may be more important for some women than others, and better targeting (i.e., adjusting screening criteria) of this service may increase uptake. For instance, women could be asked if they are currently using a form of contraception that they are happy with. Future research efforts should focus on reducing the influence of these factors by implementing advanced scheduling of the co-located visits.

It is also important to recognize other missed opportunities for earlier postpartum contraception care visits and reaching women earlier. For instance, scheduling the routine postpartum visit earlier, such as the 2 week post-operative wound check for women who had Cesarean deliveries or at 3–4 weeks postpartum as suggested by Speroff and Mishell (Speroff & Mishell, 2008) are earlier opportunities to address postpartum care. Since many women resume sexual activity before the 6-week postpartum visit, and because ovulation frequently occurs before 6 weeks, Speroff and Mishell note that a 3-week visit would be more effective in preventing postpartum conception by initiating effective contraception at this time (Speroff & Mishell, 2008).

This study had limitations. First, our study is a single-site study that was conducted at an academic medical center, and therefore the results should not be generalized other health care settings. Additionally, logistical issues specific to women’s schedules could have influenced acceptance rates. Specifically, women who use public transit or relied on others for their transportation to and from their pediatric visit may not have had the flexibility to change their transportation plans to remain for another hour or more to attend an additional visit. Lastly, due to the way data was collected and analyzed for this study, we were not able to determine the number of women who accepted a future date appointment who also had a follow-up Ob/Gyn appointment before that future appointment.

A strength of this study was surveying all women in the intervention group about the likeability of the intervention (i.e., being offered a co-located contraceptive visit with well-baby care) and reasons why the visit was declined giving us insight to improve the intervention in future studies. Incorporating such elements concurrent to a clinical effectiveness trial may help speed the pace of translating research into practice (Curran, Bauer, Mittman, Pyne, & Stetler, 2012).

Implications for Practice and/or Policy

Low postpartum visit attendance and the persistent gap between planned and actual LARC use show a need for continued investigation of alternative models that reduce barriers to women’s use of their preferred contraceptive methods. At this point, direct application to practice or policy is premature, but continued research can additionally evaluate implementation strategies concurrent with individual contraception use outcomes to further enable other clinical settings to adopt co-located contraception care for their postpartum patients.

Conclusions

Co-located care was perceived favorably by postpartum women and in turn, may lead to greater uptake of LARC as well as all methods of contraception for those women who choose it. Additionally, offering multiple options and opportunities for obtaining contraception is necessary to meet all women’s contraceptive needs, and co-located care could provide an additional opportunity to meet the contraceptive needs of postpartum women. More research is needed to optimize and test a systems-level intervention such that women who need a co-located visit can make arrangements ahead of time as well as address other systems-level factors that would be required to create a sustainable co-located model of care.

Figure 2:

Participant ratings on likability and future interest of co-located contraception services

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of enrolled women by group

| Maternal Characteristics | Overall (n=446) | Intervention (n=231) | Control (n=215) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Weeks Postpartum | <2 | 177 | 96 (41.6%) | 81 (37.7%) | 0.006 |

| 2–<4 | 71 | 47 (20.4%) | 24 (11.2%) | ||

| 4–<6 | 70 | 35 (15.1%) | 35 (16.3%) | ||

| 6–<12 | 83 | 30 (13.0%) | 53 (24.6%) | ||

| ≥12 | 45 | 23 (9.9%) | 22 (10.2%) | ||

| Maternal Age | <20 | 42 | 24 (10.4%) | 18 (8.4%) | 0.80 |

| 20–24 | 128 | 65 (28.1%) | 63 (29.3%) | ||

| 25–29 | 125 | 66 (28.6%) | 59 (27.4%) | ||

| 30–34 | 97 | 46 (19.9%) | 51 (23.7%) | ||

| ≥35 | 54 | 30 (13.0%) | 24 (11.2%) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | African American | 256 | 136 (58.9%) | 120 (56.1%) | 0.17 |

| Latina/Hispanic | 102 | 59 (25.5%) | 43 (20.1%) | ||

| White | 52 | 22 (9.5%) | 30 (14.0%) | ||

| Asian/Pacific Islander | 19 | 9 (3.9%) | 10 (4.7%) | ||

| Other/Multirace | 16 | 5 (2.2%) | 11 (5.1%) | ||

| Education | <HS/In HS | 32 | 18 (7.8%) | 14 (6.5%) | 0.59 |

| HS graduate | 126 | 66 (28.6%) | 60 (27.9%) | ||

| Some college/2 year degree | 180 | 97 (42.0%) | 83 (38.6%) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree or higher | 108 | 50 (21.6%) | 58 (27.0%) | ||

| Marital Status/Living Arrangements | Married, living together | 128 | 62 (26.8%) | 66 (30.7%) | 0.11 |

| Not married, living together | 148 | 73 (31.6%) | 75 (34.9%) | ||

| Not married, living apart | 96 | 48 (20.8%) | 48 (22.3%) | ||

| Single | 74 | 48 (20.8%) | 26 (12.1%) | ||

| Parity | 1 | 236 | 122 (52.8%) | 114 (53.0%) | 0.96 |

| 2 | 129 | 66 (28.6%) | 63 (29.3%) | ||

| 3+ | 81 | 43 (18.6%) | 38 (17.7%) | ||

| Employment | Full-time | 54 | 30 (13.1%) | 24 (11.2%) | 0.43 |

| Part-time | 23 | 11 (4.8%) | 12 (5.6%) | ||

| Maternity leave | 185 | 102 (44.5%) | 83 (38.6%) | ||

| Unemployed | 182 | 86 (37.6%) | 96 (44.6%) | ||

| Ever Use of Contraceptives | Oral contraceptive pill | 264 | 136 (60.2%) | 128 (60.4%) | 0.97 |

| Patch | 76 | 47 (20.9%) | 29 (13.7%) | 0.05 | |

| NuvaRing/Vaginal ring | 35 | 17 (7.6%) | 18 (8.5%) | 0.74 | |

| IUD | 41 | 24 (10.7%) | 17 (8.0%) | 0.34 | |

| Implant | 16 | 7 (3.1%) | 9 (4.3%) | 0.53 | |

| Depo (Shot) | 205 | 106 (46.9%) | 99 (46.1%) | 0.78 | |

| Emergency contraception | 92 | 41 (18.3%) | 51 (24.1%) | 0.14 | |

| Vasectomy | 3 | 1 (0.5%) | 2 (1.0%) | 0.53 | |

| None | 47 | 23 (14.7%) | 24 (15.4%) | 0.87 | |

| Pregnancy Intention | Intended | 209 | 105 (45.6%) | 104 (48.6%) | 0.81 |

| Unwanted/Mistimed | 204 | 108 (47.0%) | 96 (44.9%) | ||

| Don’t know/Refused | 31 | 17 (7.4%) | 14 (6.5%) | ||

| Prenatal Care | Yes | 438 | 227 (98.3%) | 211 (98.1%) | 0.92 |

| Delivery Method | Vaginal | 324 | 160 (70.5%) | 164 (77.0%) | 0.12 |

| Cesarean section | 116 | 67 (29.5%) | 49 (23.0%) | ||

| Currently Using Birth Control | Yes | 178 | 88 (38.9%) | 90 (43.9%) | 0.30 |

| Current Birth | Tier 1 | 10 | 7 (3.1%) | 3 (1.5%) | 0.37 |

| Control Tier a | Tier 2 | 141 | 70 (31.0%) | 71 (34.6%) | |

| Tier 3 | 26 | 11 (4.9%) | 15 (7.3%) | ||

| None/EC | 254 | 138 (61.0%) | 116 (56.6%) | ||

| Postpartum Follow Up Visit | Yes | 122 | 53 (23.0%) | 69 (32.1%) | 0.03 |

| Infant Feeding | Breast only | 87 | 40 (17.5%) | 47 (21.9%) | 0.50 |

| Breast and bottle – breast milk only | 62 | 35 (15.3%) | 27 (12.6%) | ||

| Bottle – formula | 173 | 87 (38.0%) | 86 (40.0%) | ||

| Formula and breastmilk | 122 | 67 (29.2%) | 55 (25.6%) | ||

Birth Control Tier: Tier 1 – vasectomy; Tier 2 – pill, ring, patch, shot, and multiple methods; Tier 3 – condoms or other method; None/EC – no method stated or emergency contraception only

Biography

Author Descriptions:

Sadia Haider, MD, MPH, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Section Chief of Family Planning and Contraceptive Research at the University of Chicago. Her research program focuses on health services research to decrease reproductive health disparities.

Cynthia Stoffel, MPH, CNM, MSN, is a Certified Nurse Midwife at Erie Family Health Centers in Chicago, Illinois. Her research interests include family planning and maternal health disparities.

Kristin Rankin, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the Epidemiology and Biostatistics Division and Co-Director of the Maternal and Child Health Epidemiology Training Program at the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health. Her research interests include women’s health, family planning, implementation science, and racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in adverse birth outcomes.

Keriann Uesugi, PhD, is a Research Assistant Professor in the Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health. Her research focuses on the evaluation of maternal and child health interventions, programs, and policies.

Arden Handler, DrPH, is the Director of the Center of Excellence in Maternal Child Health and Interim Division Director of Community Health Sciences at the University of Illinois as Chicago School of Public Health. Her research focuses on the exploration of factors that increase inequities in adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Rachel Caskey, MD, MAPP, is an Associate Professor of Pediatrics and Internal Medicine and the Division Chief of Academic Internal Medicine and Geriatrics at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Her research focuses on reproductive health care delivery through scalable behavior change interventions.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Sadia Haider, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Section Chief of Family Planning and Contraceptive Research at the University of Chicago.

Cynthia Stoffel, Midwife at Erie Family Health Centers in Chicago, Illinois.

Kristin Rankin, Epidemiology and Biostatistics Division and Co-Director of the Maternal and Child Health Epidemiology Training Program at the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health.

Keriann Uesugi, Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Illinois at Chicago School of Public Health.

Arden Handler, Center of Excellence in Maternal Child Health and Interim Division Director of Community Health Sciences at the University of Illinois as Chicago School of Public Health.

Rachel Caskey, Pediatrics and Internal Medicine and the Division Chief of Academic Internal Medicine and Geriatrics at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

References

- Bryant AS, Haas JS, McElrath TF, & McCormick MC (2006). Predictors of compliance with the postpartum visit among women living in healthy start project areas. Maternal and child health journal, 10(6), 511–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caskey R, Stumbras K, Rankin K, Osta A, Haider S, & Handler A (2016). A novel approach to postpartum contraception: a pilot project of Pediatricians’ role during the well-baby visit. Contraception and reproductive medicine, 1(1), 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2011). National Survey of Children’s Health - State and local area integrated telephone survey. [Google Scholar]

- Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, & Stetler C (2012). Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Medical care, 50(3), 217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dee DL, Pazol K, Cox S, Smith RA, Bower K, Kapaya M, . . . D’Angelo D. (2017). Trends in Repeat Births and Use of Postpartum Contraception Among Teens—United States, 2004–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 66(16), 422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan EB, Rodman E, Sorensen EA, Landis S, & Colvin GF (2009). A survey of mothers’ comfort discussing contraception with infant providers at well-child visits. Southern medical journal, 102(3), 260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman MP, Wright R, Watchman M, Wahl RA, Sisk DJ, Fraleigh L, & Weibrecht JM (2005). Postpartum depression assessments at well-baby visits: screening feasibility, prevalence, and risk factors. Journal of Women’s Health, 14(10), 929–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghandour RM, Jones JR, Lebrun-Harris LA, Minnaert J, Blumberg SJ, Fields J, . . . Kogan MD (2018). The Design and Implementation of the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health. Maternal and child health journal, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grisaru-Granovsky S, Gordon ES, Haklai Z, Samueloff A, & Schimmel MM (2009). Effect of interpregnancy interval on adverse perinatal outcomes--a national study. Contraception, 80(6), 512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harney C, Dude A, & Haider S (2017). Factors associated with short interpregnancy interval in women who plan postpartum LARC: a retrospective study. Contraception, 95(3), 245–250. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2016.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson V, Stumbras K, Caskey R, Haider S, Rankin K, & Handler A (2016). Understanding factors associated with postpartum visit attendance and contraception choices: listening to low-income postpartum women and health care providers. Maternal and child health journal, 20(1), 132–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofler LG, Cordes S, Cwiak CA, Goedken P, Jamieson DJ, & Kottke M (2017). Implementing immediate postpartum long-acting reversible contraception programs. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 129(1), 3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabakian‐Khasholian T, & Campbell O (2005). A simple way to increase service use: triggers of women’s uptake of postpartum services. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 112(9), 1315–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw TS, Niccolai LM, Ickovics JR, Lewis JB, Meade CS, & Ethier KA (2003). Short and long-term impact of adolescent pregnancy on postpartum contraceptive use: implications for prevention of repeat pregnancy. J Adolesc Health, 33(5), 359–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaraswami T, Rankin KM, Lunde B, Cowett A, Caskey R, & Harwood B (2018). Acceptability of Postpartum Contraception Counseling at the Well Baby Visit. Maternal and child health journal, 22(11), 1624–1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon S, Lazo-Escalante M, Villaran MV, & Li CI (2012). Relationship between interpregnancy interval and birth defects in Washington State. J Perinatol, 32(1), 45–50. doi: 10.1038/jp.2011.49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law A, Yu J, Wang W, Lin J, & Lynen R (2017). Trends and regional variations in provision of contraception methods in a commercially insured population in the United States based on nationally proposed measures. Contraception, 96(3), 175–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moniz M, Chang T, Heisler M, & Dalton VK (2017). Immediate Postpartum Long Acting Reversible Contraception: The Time Is Now. Contraception, 95(4), 335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley AS, Rich EC, Maccarone A, DesRoches CM, & Reid RJ (2015). Disentangling the linkage of primary care features to patient outcomes: a review of current literature, data sources, and measurement needs. Journal of general internal medicine, 30(3), 576–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olin S-CS, Kerker B, Stein RE, Weiss D, Whitmyre ED, Hoagwood K, & Horwitz SM (2016). Can postpartum depression be managed in pediatric primary care? Journal of Women’s Health, 25(4), 381–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter JE, Coleman-Minahan K, White K, Powers DA, Dillaway C, Stevenson AJ, . . . Grossman D (2017). Contraception After Delivery Among Publicly Insured Women in Texas: Use Compared With Preference. Obstet Gynecol, 130(2), 393–402. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter JE, Hubert C, Stevenson AJ, Hopkins K, Aiken AR, White K, & Grossman D (2016). Barriers to Postpartum Contraception in Texas and Pregnancy Within 2 Years of Delivery. Obstet Gynecol, 127(2), 289–296. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rankin KM, Haider S, Caskey R, Chakraborty A, Roesch P, & Handler A (2016). Healthcare Utilization in the Postpartum Period Among Illinois Women with Medicaid Paid Claims for Delivery, 2009–2010. Matern Child Health J, 20(Suppl 1), 144–153. doi: 10.1007/s10995-016-2043-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speroff L, & Mishell DR (2008). The postpartum visit: it’s time for a change in order to optimally initiate contraception. Contraception, 78(2), 90–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang JH, Dominik R, Re S, Brody S, & Stuart GS (2013). Characteristics associated with interest in long-acting reversible contraception in a postpartum population. Contraception, 88(1), 52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thiel de Bocanegra H, Braughton M, Bradsberry M, Howell M, Logan J, & Schwarz EB (2017). Racial and ethnic disparities in postpartum care and contraception in California’s Medicaid program. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 217(1), 47.e41–47.e47. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoma ME, Copen CE, & Kirmeyer SE (2016). Short Interpregnancy Intervals in 2014: Differences by Maternal Demographic Characteristics. NCHS Data Brief(240), 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trogstad LI, Eskild A, Magnus P, Samuelsen SO, & Nesheim BI (2001). Changing paternity and time since last pregnancy; the impact on preeclampsia risk. A study of 547 238 women with and without previous preeclampsia. Int J Epidemiol, 30(6), 1317–1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Der Zee-Van AI, Boere-Boonekamp MM, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CG, IJzerman MJ, Haasnoot-Smallegange RM, & Reijneveld SA (2017). Post-up study: postpartum depression screening in well-child care and maternal outcomes. Pediatrics, 140(4), e20170110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weir S, Posner HE, Zhang J, Willis G, Baxter JD, & Clark RE (2011). Predictors of prenatal and postpartum care adequacy in a Medicaid managed care population. Women’s Health Issues, 21(4), 277–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White K, Teal SB, & Potter JE (2015). Contraception after delivery and short interpregnancy intervals among women in the United States. Obstet Gynecol, 125(6), 1471–1477. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Workgroup, B. F. P. S., Practice, C. o., & Medicine, A. (2017). 2017 recommendations for preventive pediatric health care. Pediatrics, 139(4), e20170254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]