Abstract

Introduction

Global shortages in the supply of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines have resulted in campaigns to first inoculate individuals at highest risk for death from COVID-19. Here, we develop a predictive model of COVID-19-related death using longitudinal clinical data from patients in metropolitan Detroit.

Methods

All individuals included in the analysis had a laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. Thirty-six pre-existing conditions with a false discovery rate p<0.05 were combined with other demographic variables to develop a parsimonious prediction model using least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression. The model was then prospectively validated in a separate set of individuals with confirmed COVID-19.

Results

The study population consisted of 15 502 individuals with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2. The main prediction model was developed using data from 11 635 individuals with 709 reported deaths (case fatality ratio 6.1%). The final prediction model consisted of 14 variables with 11 comorbidities. This model was then prospectively assessed among the remaining 3867 individuals (185 deaths; case fatality ratio 4.8%). When compared with using an age threshold of 65 years, the 14-variable model detected 6% more of the individuals who would die from COVID-19. However, below age 45 years and its risk equivalent, there was no benefit to using the prediction model over age alone.

Discussion

Using a prediction model, such as the one described here, may help identify individuals who would most benefit from COVID-19 inoculation, and thereby may produce more dramatic initial drops in deaths through targeted vaccination.

Keywords: COVID-19, viral infection

Key messages.

Prioritisation for COVID-19 vaccination has largely been based on age; it is not known if using additional comorbidity information can improve targeting high-risk individuals without substantial increasing the numbers needing to be vaccinated.

We show that using comorbidities can substantially improve identifying individuals likely to die from COVID-19 if infected over using age alone as a predictor; however, the relative benefit of this added information disappears below the risk equivalent of age 45 years.

Our prediction algorithm was developed in a large and diverse patient population from metropolitan Detroit with electronic data on longitudinal care; hence, we were able to build and validate a prediction model of COVID-19-related death that is broadly generalisable and easily applied.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by SARS-CoV-2, has exceeded 32 million cases and a half million deaths in the USA.1 Real-world vaccination effectiveness studies suggest that the mRNA-based vaccines are highly effective in preventing symptomatic disease—up to 82% after one dose and 94% after two doses.2 Even with the recent overwhelming spread of the SAR-CoV-2 Delta variant, vaccination is associated with a >11 times lower age-standardised incidence rate ratio for death.3 To date over 7 billion vaccine doses have been administered, yet the distribution of these doses has been skewed—approximately 65% of individuals in high-income countries have been vaccinated in contrast to 6.5% in low-income countries.4

Given limited supply of vaccines, immunisation roll-out strategies have prioritised high-risk individuals; this prioritisation has been largely based on patient age.5 6 Vaccination prioritisation could be improved through better algorithms to identify individuals at highest risk of death once infected. Here, we leverage detailed longitudinal clinical information of pre-existing comorbidities to develop a prediction model of COVID-19-related death in a racially diverse patient population from southeast Michigan. It is hoped that the information gleaned from this well-characterised patient population can inform COVID-19 severity prediction and vaccination roll-out strategies elsewhere.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

This study was developed to identify individuals at highest risk for COVID-19 death to help target individuals for early immunisation. For the purposes of this study, we use terms African American and European American to refer to individuals who self-identified as non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white, respectively.

Model development

The prediction models were developed in accordance to Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis guidelines.7 We used medical records from patients receiving care at the health system to identify adults with the following characteristics: age ≥20 years, a PCR confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, and ≥1 outpatient visit 2 years to 1 month before the first positive SARS-CoV-2 test was collected (ie, the index date). Online supplemental figure 1 illustrates how individuals were identified and how their data were used for developing and testing the prediction model. A COVID-19-related death was defined as one occurring during a hospital admission or within 14 days of hospital discharge for a COVID-19 infection (n=805). We also included 89 patients who died outside of the hospital and whose last diagnosis of record was a COVID-19 infection (n=89).

bmjresp-2021-001016supp001.pdf (77.7KB, pdf)

There were 15 502 laboratory confirmed COVID-19 cases with 894 related deaths (13 686 cases from 2020 and 1816 cases from 2021); index dates ranged from 12 March 2020 to 21 February 2021. We used 85% of the cases from 2020 (n=11 635 with 709 deaths) to develop the prediction model (training set), and we randomly set aside a group of 2051 cases (with 123 deaths) from 2020 and 1816 cases (with 62 deaths) from 2021 to measure model performance (testing set). The distinction by year of disease onset was done to ensure that the prediction model was robust to the changing characteristics of the epidemic and the patient populations affected.

All primary encounter diagnoses within the health system between March 2018 and January 2021 were categorised into 133 separate clinical categories, and each category consisted of multiple International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes. A pre-existing condition was defined as receiving at least two diagnoses (ICD-10 codes) within a category between 2 years prior to 1 month prior to the index date. Conditions in which ≤1 individual with COVID-19 was affected or conditions confined to only one sex (eg, pregnancy, erectile dysfunction and menopause) were not analysed. This resulted in 78 separate pre-existing conditions available for assessing association with COVID-19-related death. Patient age, sex, race-ethnicity, smoking status, body mass index (BMI), serum creatinine values and pre-existing conditions (the latter restricted to those with a false discovery rate adjusted p<0.05), were used as initial input in constructing the prediction model. Least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression was used to select a parsimonious set of predictor variables for COVID-19-related death. LASSO regression was used since it can handle overfitting and multicollinearity8 9; less influential coefficients are shrunk to zero.8 The penalty parameter (lambda=0.01) for LASSO regression was selected to optimise performance in 10-fold cross validation.9 10

A risk score (RS) was constructed from the variables selected via LASSO; this score was assessed for its predictive performance in the set aside group of 3867 individuals. Variable weights were transformed by multiplying each coefficient by 1000; this ensured that all model weights were >1. Each individual’s composite RS was calculated by summing the weighted variable results. Analyses were conducted using the statistical software R11; the R packages glmnet and caret were used for LASSO regression and for calculating the confusion matrix, respectively.12 13

Results

As shown in table 1, the average age of the 15 502 study individuals was 56.0 years (SD=18.0 years), and 9118 (58.8%) were female. The race-ethnic breakdown included 9176 (59.2%) European Americans, 4117 (26.6%) African Americans, 609 (3.9%) Latinos and 284 Asians (1.8%). Overall, 894 of the 15 502 individuals with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 died from COVID-19 (case fatality ratio of 5.8%). The demographic characteristics of the individuals who died of COVID-19 differed from those who survived. When compared with those who survived, individuals who died tended to be older (76.95 years vs 54.73 years), were more likely to be male (54.7% vs 40.4%), had higher serum creatinine levels (1.58 mg/dL vs 0.99 mg/dL) and had a history of smoking (60.7% vs 40.8%). Patients in the training and testing sets were characteristically similar. A total of 709 of the 11 635 individuals used in the train set died of COVID-19 (case fatality ratio 6.1%), and 185 of the 3867 individuals in the testing set died of COVID-19 (case fatality ratio 4.8%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with COVID-19 stratified by analysis group and survival status*

| Combined | Training set | Testing set | |||||||

| All individuals (n=15 502) | Survived (n=14 608) | Died (n=894) | All (n=11 635) | Survived (n=10 926) | Died (n=709) | All (n=3867) | Survived (n=3682) | Died (n=185) | |

| Age in years—mean±SD | 56.01±17.98 | 54.73±17.43 | 76.95±13.22 | 56.10±17.96 | 54.75±17.37 | 76.89±13.39 | 55.73±18.04 | 54.66±17.59 | 77.17±12.55 |

| Age categories | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| 20–29 years | 1499 (9.7) | 1495 (10.2) | 4 (0.4) | 1125 (9.7) | 1121 (10.3) | 4 (0.6) | 374 (9.7) | 374 (10.2) | 0 (0) |

| 30–49 years | 4145 (26.7) | 4115 (28.2) | 30 (3.4) | 3048 (26.2) | 3024 (27.7) | 24 (3.4) | 1097 (28.4) | 1091 (29.6) | 6 (3.2) |

| 50–64 years | 4866 (31.4) | 4746 (32.5) | 120 (13.4) | 3721 (32.0) | 3626 (33.2) | 95 (13.4) | 1145 (29.6) | 1120 (30.4) | 25 (13.5) |

| 65–79 years | 3479 (22.4) | 3143 (21.5) | 336 (37.6) | 2608 (22.4) | 2340 (21.4) | 268 (37.8) | 871 (22.5) | 803 (21.8) | 68 (36.8) |

| ≥80 years | 1513 (9.8) | 1109 (7.6) | 404 (45.2) | 1133 (9.7) | 815 (7.5) | 318 (44.9) | 380 (9.8) | 294 (8.0) | 86 (46.5) |

| Sex—no (%) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Female | 9118 (58.8) | 8713 (59.6) | 405 (45.3) | 6835 (58.7) | 6510 (59.6) | 325 (45.8) | 2283 (59.0) | 2203 (59.8) | 80 (43.2) |

| Male | 6384 (41.2) | 5895 (40.4) | 489 (54.7) | 4800 (41.3) | 4416 (40.4) | 384 (54.2) | 1584 (41.0) | 1479 (40.2) | 105 (56.8) |

| Race-ethnicity—no (%) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| African American | 4117 (26.6) | 3856 (26.4) | 261 (29.2) | 3109 (26.7) | 2894 (26.5) | 215 (30.3) | 1008 (26.1) | 962 (26.1) | 46 (24.9) |

| European American | 9176 (59.2) | 8623 (59.0) | 553 (61.9) | 6828 (58.7) | 6400 (58.6) | 428 (60.4) | 2348 (60.7) | 2223 (60.4) | 125 (67.6) |

| Asian | 284 (1.8) | 280 (1.9) | 4 (0.4) | 220 (1.9) | 217 (2.0) | 3 (0.4) | 64 (1.7) | 63 (1.7) | 1 (0.5) |

| Latino | 609 (3.9) | 586 (4.0) | 23 (2.6) | 473 (4.1) | 452 (4.1) | 21 (3.0) | 136 (3.5) | 134 (3.6) | 2 (1.1) |

| Other or unknown† | 1316 (8.5) | 1263 (8.6) | 53 (5.9) | 1005 (8.6) | 963 (8.8) | 42 (5.9) | 311 (8.0) | 300 (8.1) | 11 (5.9) |

| BMI in kg/meter2—mean±SD‡ | 31.83±7.88 | 31.98±7.83 | 29.45±8.38 | 31.82±7.89 | 31.97±7.82 | 29.54±8.59 | 31.86±7.87 | 32.00±7.86 | 29.10±7.53 |

| BMI categories | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| <18.5 (underweight) | 143 (0.9) | 108 (0.7) | 35 (3.9) | 114 (1.0) | 85 (0.8) | 29 (4.1) | 29 (0.7) | 23 (0.6) | 6 (3.2) |

| 18.5 to <25 (normal weight) | 2714 (17.5) | 2461 (16.8) | 253 (28.3) | 2019 (17.4) | 1821 (16.7) | 198 (27.9) | 695 (18.0) | 640 (17.4) | 55 (29.7) |

| 25 to <30 (overweight) | 4378 (28.2) | 4123 (28.2) | 255 (28.5) | 3302 (28.4) | 3095 (28.3) | 207 (29.2) | 1076 (27.8) | 1028 (27.9) | 48 (25.9) |

| 30 to <35 (class-1 obesity) | 3788 (24.4) | 3611 (24.7) | 177 (19.8) | 2852 (24.5) | 2714 (24.8) | 138 (19.5) | 936 (24.2) | 897 (24.4) | 39 (21.1) |

| 35 to <40 (class-2 obesity) | 2270 (14.6) | 2189 (15.0) | 81 (9.1) | 1684 (14.3) | 1625 (14.9) | 59 (8.3) | 586 (15.2) | 564 (15.3) | 22 (11.9) |

| ≥40 (class-3 obesity) | 2209 (14.2) | 2116 (14.5) | 93 (10.4) | 1664 (14.3) | 1586 (14.5) | 78 (11.0) | 545 (14.1) | 530 (14.4) | 15 (8.1) |

| Serum creatinine in mg/dL – (mean±SD)‡ | 1.02±1.03 | 0.99±0.96 | 1.58±1.76 | 1.03±1.05 | 0.99±0.96 | 1.62±1.85 | 1.01±0.98 | 0.99±0.95 | 1.46±1.34 |

| Smoking status – no (%) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Ever smoker§ | 6505 (42.0) | 5962 (40.8) | 543 (60.7) | 4874 (41.9) | 4444 (40.7) | 430 (60.6) | 1631 (42.2) | 1518 (41.2) | 113 (61.1) |

| Never smoker | 8997 (58.0) | 8646 (59.2) | 351 (39.3) | 6761 (58.1) | 6482 (59.3) | 279 (39.4) | 2236 (57.8) | 2164 (58.8) | 72 (38.9) |

| Occupation | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Healthcare worker | 307 (2.0) | 304 (2.1) | 3 (0.3) | 229 (2.0) | 227 (2.1) | 2 (0.3) | 78 (2.0) | 77 (2.1) | 1 (0.5) |

| Other | 2086 (13.5) | 1975 (13.5) | 111 (12.4) | 1583 (13.6) | 1492 (13.7) | 91 (12.8) | 503 (13.0) | 483 (13.1) | 20 (10.8) |

| Unknown | 13 109 (84.6) | 12 329 (84.4) | 780 (87.2) | 9823 (84.4) | 9207 (84.3) | 616 (86.9) | 3286 (85.0) | 3122 (84.8) | 164 (88.6) |

*The training set comprised individuals used to identify risk factors for COVID-19-related death; these individuals were used to create the prediction model. The testing set comprised a separate group of individuals used to test the performance of the prediction model.

†Other or unknown race-ethnicity included individuals who did not identify as exclusively African American, European American, Asian or Latino. This group also included individuals who identified as being part of multiple groups.

‡This was based on the most recent measure of BMI or creatinine >1 month prior to the index date. Index date was defined as the date that the first SARS-CoV-2 test was collected.

§Ever smokers included both past and current smokers.

BMI, body mass index.

The prediction model was developed and trained in a randomly selected set of 11 635 SARS-CoV-2-infected individuals. The demographic and clinical variable association results from model development are shown in both table 2 and online supplemental table 1 of the online supplement. Age was the most significant predictor for COVID-19-related death (p=1.76×10−144), but male sex (p=2.68×10−5), African American race (p=5.94×10−5), a history of smoking (p=3.28×10−6) and higher serum creatinine values (p=7.28×10−16) were also significantly associated. BMI was not associated with COVID-19-related death after adjusting for the above variables (p=0.675). Thirty-six pre-existing conditions were also associated with COVID-19-related death with a false discovery rate adjusted p<0.05. The most significant pre-existing conditions were a history of respiratory failure (p=1.22×10−18) and congestive heart failure (p=1.27×10−17). A final set of fourteen variables were selected for the prediction model (table 2), resulting in the following RS calculation:

Table 2.

Variable selection for a prediction model of COVID-19-related death among individuals with laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection

| Clinical variable | Base multivariable model (p value)* | Diagnoses promoted for evaluation by LASSO regression (FDR adjusted p value)† | LASSO-derived coefficients for variables retained in the final prediction model‡ | OR for the retained variable§ |

| Age | 1.76×10–144 | -- | 0.06290 | 1.065 |

| Sex-male | 2.68×10–5 | -- | 0.00718 | 1.007 |

| Race-ethnicity—African American | 5.94×10–5 | -- | -- | -- |

| Race-ethnicity—Asian | 0.070 | -- | -- | -- |

| Race-ethnicity—Latino | 0.282 | -- | -- | -- |

| Race-ethnicity—other | 0.721 | -- | -- | -- |

| Smoking status | 3.28×10–6 | -- | -- | -- |

| BMI | 0.675 | -- | -- | -- |

| Creatinine, serum | 7.28×10–16 | -- | 0.12933 | 1.138 |

| Pulmonary: respiratory failure | -- | 1.22×10–18 | 0.58317 | 1.792 |

| Cardiovascular: congestive heart failure | -- | 1.27×10–17 | 0.53928 | 1.715 |

| Pulmonary: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | -- | 3.69×10–13 | 0.29649 | 1.345 |

| General: supplemental O2 or ventilation | -- | 3.82×10–10 | -- | -- |

| Cardiovascular: coronary artery disease | -- | 3.07×10–7 | 0.07760 | 1.081 |

| Cardiovascular: atrial fibrillation or flutter | -- | 6.27×10–7 | 0.07681 | 1.080 |

| Cardiovascular: cerebrovascular disease | -- | 7.20×10–6 | 0.12774 | 1.136 |

| Gastrointestinal: liver disease, not otherwise specified | -- | 7.20×10–6 | -- | -- |

| General: electrolyte disorder | -- | 7.74×10–6 | -- | -- |

| Infectious disease: sepsis | -- | 1.95×10–5 | -- | -- |

| Cardiovascular: pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis | -- | 2.74×10–5 | -- | -- |

| Musculoskeletal: skeletal disorder affecting thorax | -- | 2.74×10–5 | 0.09123 | 1.096 |

| Psychiatric and substance use: alcohol use | -- | 2.74×10–5 | -- | -- |

| Infectious disease: pneumonia | -- | 2.98×10–5 | -- | -- |

| Cardiovascular: peripheral vascular occlusive disease | -- | 3.01×10–5 | 0.14121 | 1.152 |

| Haematologic: leucopenia | -- | 3.87×10–5 | -- | -- |

| Dermatology: pressure ulcer | -- | 7.11×10–5 | 0.21731 | 1.243 |

| Pulmonary: pulmonary vascular hypertension | -- | 8.32×10–5 | -- | -- |

| Gastrointestinal: cirrhosis | -- | 1.15×10–4 | -- | -- |

| General: nutritional deficiency | -- | 7.88×10–4 | -- | -- |

| Neurologic: traumatic brain injury | -- | 8.84×10–4 | 0.04844 | 1.050 |

| Cardiovascular: structural heart disease | -- | 1.23×10–3 | -- | -- |

| Neurologic: epilepsy | -- | 1.88×10–3 | -- | -- |

| Cardiovascular: cardiomyopathy | -- | 2.74×10–3 | -- | -- |

| Neurologic: dementia | -- | 4.12×10–3 | 0.13412 | 1.144 |

| Endocrine and metabolism: diabetes any | -- | 5.70×10–3 | -- | -- |

| Rheumatologic: sarcoidosis | -- | 7.48×10–3 | -- | -- |

| Haematologic: coagulopathy | -- | 7.49×10–3 | -- | -- |

| Psychiatric and substance use: opioid use | -- | 9.14×10–3 | -- | -- |

| Gastrointestinal: gastro-oesophageal disease | -- | 0.011 | -- | -- |

| Oncologic: solid malignancy | -- | 0.021 | -- | -- |

| Infectious disease: infectious enteritis | -- | 0.021 | -- | -- |

| Gastrointestinal: constipation | -- | 0.030 | -- | -- |

| General: muscle contraction or wasting | -- | 0.038 | -- | -- |

| Neurologic: encephalopathy | -- | 0.041 | -- | -- |

| Rheumatologic: systemic lupus erythematosus | -- | 0.049 | -- | -- |

Risk score=2340.58 + 62.90×age (in years)+7.18×sex (male=1, female=0)+129.33×serum creatinine (in mg/dL)+583.17×history of respiratory failure (yes=1, no=0)+539.28×congestive heart failure (yes=1, no=0)+296.49×chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (yes=1, no=0)+77.60×coronary artery disease (yes=1, no=0)+76.81×atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter (yes=1, no=0)+127.74×cerebrovascular disease (yes=1, no=0)+91.23×musculoskeletal disease affecting thorax (yes=1, no=0)+141.21×peripheral vascular disease (yes=1, no=0)+217.31×pressure ulcer (yes=1, no=0)+48.44×traumatic brain injury (yes=1, no=0)+134.12×dementia (yes=1, no=0).

*The base model included all of the variables shown; p values were derived from the adjusted model.

†P values are adjusted for the false discovery rate. Each clinical variable is separately adjusted by the following model: COVID-19 death ~age+sex+race-ethnicity+smoking status +BMI+serum creatinine +clinical variable. Online supplemental table 1 shows the additional clinical variables which were screened but which did not meet the criteria for evaluation by LASSO regression for prediction model building.

‡Variable weights using in the actual prediction model were obtained by multiplying each coefficient by 1000; this ensured that all model weights were >1. The final 14-variable prediction model had the following form.

§OR for COVID-19-related death according to a one-unit increase in the listed variable (coding and directionality for each variable retained is described in the preceding footnote).

BMI, body mass index; FDR, false discovery rate; LASSO, least absolute shrinkage and selection operator.

bmjresp-2021-001016supp002.pdf (80.4KB, pdf)

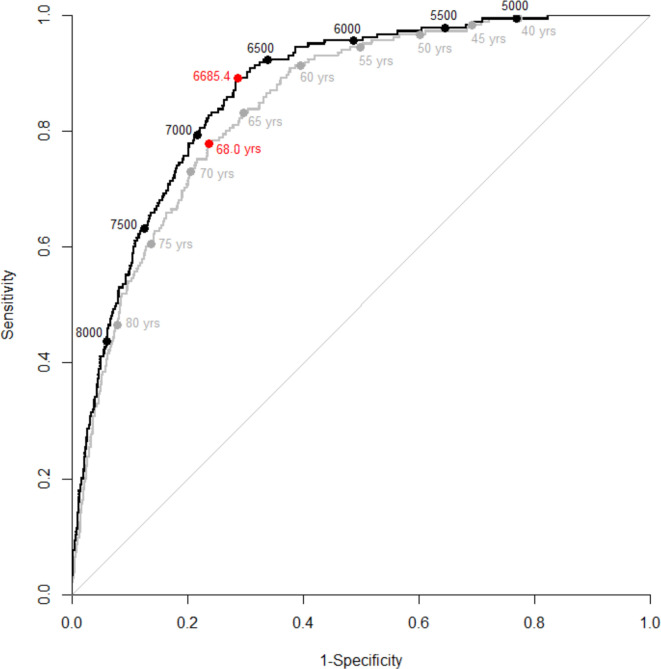

Test performance was assessed in a separate group of 3867 individuals (figure 1 and table 3). The optimum cut-point, defined by the Youden index,14 was a RS of ≥6685.4 in the 14-variable model and an age of ≥68 years in the age-only model. An age threshold of ≥65 years, the age used by many states to define early eligibility for vaccination,15 had a sensitivity of 83.2%, a specificity of 70.2%, a positive predictive value (PPV) of 12.3% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 98.8%. In comparison, the 14-variable RS with the same specificity of 70.2% (RS ≥6646.5), had a sensitivity of 89.2%, a PPV of 13.1% and an NPV of 99.2%. At an age threshold of ≤45 years, there was no difference in sensitivity using the 14-variable RS with the same specificity (RS ≤5304.8).

Figure 1.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves demonstrating the performance of two models to predict COVID-19-related deaths among individuals with laboratory confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection (n=3867) from southeast Michigan and the Detroit metropolitan area. The black line denotes the 14-variable prediction model with black circles representing risk score thresholds. The grey line denotes the age-only prediction model with grey circles representing age thresholds. Red circles represent the Youden index (ie, the point that maximises Sensitivity +Specificity – 1). The area under the curve (AUC) for the 14-variable ROC curve was 0.868 (0.846–0.891), and the AUC for the age-only ROC curve was 0.846 (0.821–0.871).

Table 3.

Differences in model performance at fixed specificity between the age-only and the 14-variable prediction models for COVID-19-related death among individuals with laboratory-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection*

| Age | Age-only model performance | Risk score | 14-variable model performance‡ | Absolute difference in sensitivity between models§ | Absolute difference in per cent designated high risk between models¶ | ||||||||

| Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value | Per cent of test population designated high risk† | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value | Per cent of test population designated high risk† | ||||

| 40 | 99.5% | 22.8% | 6.1% | 99.9% | 78.2% | 4984.6 | 99.5% | 22.8% | 6.1% | 99.9% | 78.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 41 | 99.5% | 24.1% | 6.2% | 99.9% | 77.1% | 5042.0 | 99.5% | 24.1% | 6.2% | 99.9% | 77.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 42 | 99.5% | 25.5% | 6.3% | 99.9% | 75.7% | 5108.0 | 99.5% | 25.5% | 6.3% | 99.9% | 75.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 43 | 99.5% | 27.1% | 6.4% | 99.9% | 74.1% | 5163.2 | 99.5% | 27.1% | 6.4% | 99.9% | 74.1% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 44 | 98.9% | 28.9% | 6.5% | 99.8% | 72.4% | 5234.6 | 99.5% | 28.9% | 6.6% | 99.9% | 72.4% | 0.5% | 0.0% |

| 45 | 98.4% | 30.8% | 6.7% | 99.7% | 70.6% | 5304.8 | 98.4% | 30.8% | 6.7% | 99.7% | 70.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 46 | 97.3% | 32.3% | 6.7% | 99.6% | 69.1% | 5376.8 | 97.8% | 32.3% | 6.8% | 99.7% | 69.2% | 0.5% | 0.0% |

| 47 | 97.3% | 33.8% | 6.9% | 99.6% | 67.7% | 5445.5 | 97.8% | 33.8% | 6.9% | 99.7% | 67.7% | 0.5% | 0.0% |

| 48 | 97.3% | 35.7% | 7.1% | 99.6% | 65.9% | 5508.0 | 97.8% | 35.7% | 7.1% | 99.7% | 65.9% | 0.5% | 0.0% |

| 49 | 97.3% | 37.5% | 7.3% | 99.6% | 64.1% | 5566.8 | 97.8% | 37.5% | 7.3% | 99.7% | 64.2% | 0.5% | 0.0% |

| 50 | 96.8% | 39.8% | 7.5% | 99.6% | 62.0% | 5624.6 | 97.3% | 39.8% | 7.5% | 99.7% | 62.0% | 0.5% | 0.0% |

| 51 | 96.8% | 42.3% | 7.8% | 99.6% | 59.5% | 5705.1 | 97.3% | 42.3% | 7.8% | 99.7% | 59.6% | 0.5% | 0.0% |

| 52 | 96.2% | 44.0% | 8.0% | 99.6% | 57.9% | 5765.5 | 96.8% | 44.0% | 8.0% | 99.6% | 58.0% | 0.5% | 0.0% |

| 53 | 95.7% | 46.1% | 8.2% | 99.5% | 55.9% | 5837.5 | 96.8% | 46.1% | 8.3% | 99.7% | 56.0% | 1.1% | 0.0% |

| 54 | 95.7% | 47.8% | 8.4% | 99.6% | 54.3% | 5883.8 | 96.2% | 47.8% | 8.5% | 99.6% | 54.3% | 0.5% | 0.0% |

| 55 | 94.6% | 50.2% | 8.7% | 99.5% | 52.0% | 5958.2 | 95.7% | 50.2% | 8.8% | 99.6% | 52.0% | 1.1% | 0.1% |

| 56 | 94.1% | 52.6% | 9.1% | 99.4% | 49.7% | 6042.9 | 95.7% | 52.6% | 9.2% | 99.6% | 49.7% | 1.6% | 0.1% |

| 57 | 93.0% | 54.2% | 9.3% | 99.4% | 48.0% | 6094.3 | 95.7% | 54.2% | 9.5% | 99.6% | 48.2% | 2.7% | 0.1% |

| 58 | 93.0% | 56.7% | 9.8% | 99.4% | 45.6% | 6170.6 | 95.1% | 56.7% | 10.0% | 99.6% | 45.8% | 2.2% | 0.1% |

| 59 | 92.4% | 58.7% | 10.1% | 99.4% | 43.7% | 6236.2 | 95.1% | 58.7% | 10.4% | 99.6% | 43.9% | 2.7% | 0.1% |

| 60 | 91.4% | 60.5% | 10.4% | 99.3% | 42.0% | 6295.2 | 94.6% | 60.5% | 10.7% | 99.6% | 42.2% | 3.2% | 0.2% |

| 61 | 90.3% | 62.3% | 10.7% | 99.2% | 40.2% | 6370.0 | 93.0% | 62.3% | 11.0% | 99.4% | 40.4% | 2.7% | 0.1% |

| 62 | 88.1% | 64.3% | 11.0% | 99.1% | 38.2% | 6437.7 | 92.4% | 64.3% | 11.5% | 99.4% | 38.4% | 4.3% | 0.2% |

| 63 | 86.0% | 66.4% | 11.4% | 99.0% | 36.1% | 6509.2 | 92.4% | 66.4% | 12.1% | 99.4% | 36.4% | 6.5% | 0.3% |

| 64 | 83.8% | 68.0% | 11.6% | 98.8% | 34.5% | 6559.8 | 91.4% | 68.0% | 12.6% | 99.4% | 34.8% | 7.6% | 0.4% |

| 65 | 83.2% | 70.2% | 12.3% | 98.8% | 32.4% | 6646.5 | 89.2% | 70.2% | 13.1% | 99.2% | 32.6% | 6.0% | 0.3% |

| 66 | 80.5% | 72.4% | 12.8% | 98.7% | 30.1% | 6727.3 | 86.0% | 72.4% | 13.5% | 99.0% | 30.4% | 5.4% | 0.3% |

| 67 | 78.9% | 74.4% | 13.4% | 98.6% | 28.1% | 6804.3 | 83.8% | 74.4% | 14.1% | 98.9% | 28.4% | 4.9% | 0.2% |

| 68 | 77.3% | 76.3% | 14.1% | 98.5% | 26.3% | 6889.6 | 82.2% | 76.3% | 14.8% | 98.8% | 26.5% | 4.9% | 0.2% |

| 69 | 75.1% | 77.9% | 14.6% | 98.4% | 24.6% | 6975.6 | 79.5% | 77.9% | 15.3% | 98.7% | 24.8% | 4.3% | 0.2% |

| 70 | 73.0% | 79.4% | 15.1% | 98.3% | 23.1% | 7066.7 | 77.8% | 79.4% | 16.0% | 98.6% | 23.3% | 4.9% | 0.2% |

| 71 | 69.2% | 80.9% | 15.4% | 98.1% | 21.5% | 7129.0 | 74.6% | 80.9% | 16.4% | 98.5% | 21.8% | 5.4% | 0.3% |

| 72 | 66.5% | 82.1% | 15.7% | 98.0% | 20.3% | 7193.1 | 72.4% | 82.1% | 16.9% | 98.3% | 20.5% | 6.0% | 0.3% |

| 73 | 66.0% | 83.5% | 16.7% | 98.0% | 18.9% | 7264.7 | 69.7% | 83.5% | 17.5% | 98.2% | 19.0% | 3.8% | 0.2% |

| 74 | 62.7% | 85.1% | 17.4% | 97.9% | 17.2% | 7358.3 | 67.0% | 85.1% | 18.4% | 98.1% | 17.4% | 4.3% | 0.2% |

| 75 | 60.5% | 86.3% | 18.2% | 97.8% | 15.9% | 7422.4 | 65.4% | 86.3% | 19.4% | 98.0% | 16.2% | 4.9% | 0.2% |

| 76 | 57.8% | 87.5% | 18.8% | 97.6% | 14.7% | 7503.9 | 63.2% | 87.5% | 20.2% | 97.9% | 15.0% | 5.4% | 0.3% |

| 77 | 56.2% | 88.7% | 20.0% | 97.6% | 13.5% | 7563.8 | 61.6% | 88.7% | 21.5% | 97.9% | 13.7% | 5.4% | 0.3% |

| 78 | 54.1% | 89.9% | 21.2% | 97.5% | 12.2% | 7652.7 | 56.2% | 89.9% | 21.9% | 97.6% | 12.3% | 2.2% | 0.1% |

| 79 | 51.9% | 91.1% | 22.6% | 97.4% | 11.0% | 7744.8 | 53.5% | 91.1% | 23.1% | 97.5% | 11.1% | 1.6% | 0.1% |

| 80 | 46.5% | 92.0% | 22.6% | 97.2% | 9.8% | 7827.6 | 50.3% | 92.0% | 24.0% | 97.4% | 10.0% | 3.8% | 0.2% |

| 81 | 43.8% | 93.0% | 24.0% | 97.1% | 8.7% | 7914.3 | 48.1% | 93.0% | 25.7% | 97.3% | 9.0% | 4.3% | 0.2% |

| 82 | 40.5% | 93.8% | 24.8% | 96.9% | 7.8% | 7995.5 | 44.3% | 93.8% | 26.5% | 97.1% | 8.0% | 3.8% | 0.2% |

| 83 | 38.4% | 94.5% | 25.8% | 96.8% | 7.1% | 8048.2 | 41.6% | 94.5% | 27.4% | 97.0% | 7.3% | 3.2% | 0.2% |

| 84 | 34.6% | 95.1% | 26.1% | 96.7% | 6.3% | 8104.4 | 38.9% | 95.1% | 28.5% | 96.9% | 6.5% | 4.3% | 0.2% |

| 85 | 32.4% | 95.7% | 27.5% | 96.6% | 5.6% | 8217.2 | 34.1% | 95.7% | 28.5% | 96.7% | 5.7% | 1.6% | 0.1% |

| 86 | 29.7% | 96.3% | 28.8% | 96.5% | 4.9% | 8294.8 | 31.4% | 96.3% | 29.9% | 96.5% | 5.0% | 1.6% | 0.1% |

| 87 | 23.8% | 97.0% | 28.4% | 96.2% | 4.0% | 8392.3 | 28.7% | 97.0% | 32.3% | 96.4% | 4.2% | 4.9% | 0.2% |

| 88 | 20.5% | 97.4% | 28.4% | 96.1% | 3.5% | 8452.2 | 26.5% | 97.4% | 33.8% | 96.4% | 3.8% | 6.0% | 0.3% |

| 89 | 17.8% | 97.9% | 29.7% | 96.0% | 2.9% | 8538.6 | 21.1% | 97.9% | 33.3% | 96.1% | 3.0% | 3.2% | 0.2% |

| 90 | 15.7% | 98.2% | 30.2% | 95.9% | 2.5% | 8576.6 | 20.0% | 98.2% | 35.6% | 96.1% | 2.7% | 4.3% | 0.2% |

| 91 | 10.8% | 98.5% | 27.0% | 95.7% | 1.9% | 8686.0 | 17.8% | 98.5% | 37.9% | 96.0% | 2.3% | 7.0% | 0.3% |

| 92 | 9.7% | 98.9% | 31.0% | 95.6% | 1.5% | 8860.5 | 14.1% | 98.9% | 39.4% | 95.8% | 1.7% | 4.3% | 0.2% |

| 93 | 7.6% | 99.2% | 31.8% | 95.5% | 1.1% | 8974.9 | 10.3% | 99.2% | 38.8% | 95.7% | 1.3% | 2.7% | 0.1% |

| 94 | 6.0% | 99.5% | 35.5% | 95.5% | 0.8% | 9110.9 | 7.6% | 99.5% | 41.2% | 95.5% | 0.9% | 1.6% | 0.1% |

| 95 | 2.7% | 99.5% | 22.7% | 95.3% | 0.6% | 9163.6 | 7.6% | 99.5% | 45.2% | 95.5% | 0.8% | 4.9% | 0.2% |

Risk score=2340.58 + 62.90×age (in years)+7.18×sex (male=1, female=0)+129.33×serum creatinine (in mg/dL)+583.17×history of respiratory failure (yes=1, no=0)+539.28×congestive heart failure (yes=1, no=0)+296.49×chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (yes=1, no=0)+77.60×coronary artery disease (yes=1, no=0)+76.81×atrial fibrillation/atrial flutter (yes=1, no=0)+127.74×cerebrovascular disease (yes=1, no=0)+91.23×musculoskeletal disease affecting thorax (yes=1, no=0)+141.21×peripheral vascular disease (yes=1, no=0)+217.31×pressure ulcer (yes=1, no=0)+48.44×traumatic brain injury (yes=1, no=0)+134.12×dementia (yes=1, no=0).

*High risk is defined as greater than or equal to the threshold age or risk score.

†Prediction models were tested in 3867 individuals with PCR confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection in 2020 and 2021. Test specificity at a given age was used to determine the corresponding 14-variable risk score performance for same specificity.

‡The 14-variable prediction model risk score was calculated using the following formula:.

§Absolute difference in sensitivity=sensitivity of 14-variable model – sensitivity of age-only model.

¶Absolute difference in the per cent at high risk=per cent designated high risk using 14-varaible model – per cent designated high risk using age-only model.

Discussion

Vaccines have been effective at reducing COVID-19 severity and death,16 yet global supplies are still limited, particularly in developing countries.4 Even in countries with ready access to vaccination, uptake has been insufficient to halt SARS-CoV-2 spread and a resurgence of infections and deaths. For example, in the US more than 40% of individuals are not fully vaccinated. This underscores the continued importance of targeting high risk individuals in the initial stages of vaccine roll-out, as well as for uptake once supply needs are met.

Wynants et al performed a systematic review of existing prediction models of COVID-19-related outcomes, but found a number of deficiencies in the existing literature.17 Of the 107 articles on COVID-19 prognostic models reviewed, 39 were for predicting mortality. Problematic issues in the existing literature included small study sizes and high potential bias (eg, by not adhering to prediction model reporting standards, using proxy measures for outcomes, and including study individuals not reflective of the larger target population). However, the review did identify three studies with uncertain bias but large sample sizes.18–20 Nevertheless, only two of these studies predicted COVID-19 mortality,19 20 and these were among individuals already severe enough to be admitted to the hospital.

In contrast, our prognostic score may be useful in identifying high-risk individuals based on pre-existing conditions (ie, characteristics that predispose to dying from COVID-19 prior to becoming infected). Design features which bolster the importance of our findings include using separate large and racially diverse groups for model development and validation, restricting cases to those with laboratory-confirmed SARS-COV-2 diagnoses, drawing on an extensive longitudinal record of pre-existing clinical conditions, and accounting for COVID-19-related deaths both within and outside of the hospital. In this regard, our RS represents a valuable tool to identify individuals at greatest risk from dying of COVID-19 and thus could inform vaccination roll-out schemas. For example, as compared with using an age cut-off of ≥65 years alone, our study found that incorporating pre-existing comorbidities could identify 6% more of the individuals who would die from COVID-19 if infected without increasing the total number of individuals deemed ‘high risk’ (ie, improved sensitivity with the same specificity). Conversely, our data suggest that once high-risk individuals (RS ≥5304.8) and individuals aged ≥45 years have been vaccinated, additional triage based on age or risk score among adults is not needed.

Our study should be considered in light of potential limitations. First, all the participants were recruited from a single health system in southeast Michigan. While this may limit the generalisability of our prediction model, it is important to note that our study population included all documented cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection with the health system. As a result, we broadly captured the diversity of the Detroit metropolitan area. Second, as this is an observational study, it is possible that our model missed other important predisposing clinical conditions. Nevertheless, the large number of conditions that we considered (ie, diagnoses made over nearly 3 years for the entire covered patient population) makes it is unlikely that we missed common diseases with large effects. However, the large number of variables that we evaluated simultaneously could also result in erroneous parameter estimation via multicollinearity, as has been observed elsewhere.21 To mitigate the effect of multicollinearity, we used LASSO regression. This penalised regression method constrains the degree of parameter inflation, selecting some variables for model inclusion while shrinking the parameter estimates of others to zero. In so doing, LASSO regression can improve model prediction accuracy while limiting the number of variables to those with the strongest effects.8 Third, the factors that predispose to COVID-19-related death, may not have the same relationship to vaccine response. For example, older age, smoking and obesity have been associated with lower response to SARS-CoV-2 vaccination.22 23 Unfortunately, in this study, we did not have measures of vaccine response; hence, we could not incorporate this into our model of COVID-19 mortality prediction. On the other hand, vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 were not widely available for the vast majority of our observation period. Therefore, it is highly unlikely that vaccination status confounded our risk model of COVID-19-related death. Lastly, the COVID-19 pandemic has been ever changing with new viral variants emerging rapidly.24 25 This rapid evolution has implications on vaccine response, breakthrough infections and viral virulence.26 27 To partially address this issue, we evaluated the performance of our model in patients first infected in 2020 and in 2021; our model produced similar results (data not shown). Therefore, it is possible that the predictive ability of our model may change over time, but we did not observe a noticeable difference in our time window.

In conclusion, we have developed a prediction model of COVID-19-related death using pre-existing patient characteristics and comorbidities. Since our model was based on a large, diverse and well-characterised patient population, we believe that the resulting prediction equation may be broadly suited to identifying individuals at high risk of COVID-19 death. Our model suggested that while age is an important and dominant risk factor for COVID-19-related death, if used alone to determine vaccine prioritisation, it would miss a substantial portion of high-risk individuals (ie, persons who would receive the largest risk benefit from vaccination).

Footnotes

Contributors: SX and LKW conceived the work; SX, NS, SH, WC, SS, MY, DEL and LKW were involved in either acquiring, analysing or interpreting the data for the work; SX, NS, DEL and LKW were involved in drafting the work; SX, NS, SH, WC, SS, MY, DEL and LKW revised the work for important intellectual content; all authors gave final approval of the version to be published; and all others agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work ensuring that questions related its accuracy or integrity are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding: This work was supported by the Fund for Henry Ford Hospital (DEL and LKW) and from the following institutes of the National Institutes of Health: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (R01AI079139 to LKW), the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (R01HL103871 and R01HL132154 to DEL and R01HL118267, R01HL141845, and X01HL134589 to LKW) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney diseases (R01DK113003 to LKW).

Competing interests: DEL reports serving as a consultant for Amgen, Janssen, Ortho Diagnostics, DCRI (Novartis), Cytokinetics and Martin Pharmaceuticals and having participated in the running clinical trials for Amgen, Bayer, and Janssen; these activities are unrelated to the subject matter of the current manuscript. LKW reports owning stock in companies which produce SARS-CoV-2 vaccines; there was no transactional relationship related to this manuscript. None of the other authors report any competing interests.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Henry Ford Health System. No approval ID provided.This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Henry Ford Health System. The IRB permitted a waiver of individual consent to use and analyze longitudinal clinical records of health system patients in order to build a prediction model of COVID-19-related death. This waiver was predicated on the use of the data involving no more than minimal risk to study subjects (ie, data were collected as part of clinical care), that the research could not be practicably performed without a waiver, and that the waiver didn’t negatively affect the rights or welfare of study subjects. Given the rapidly evolving pandemic, it was also not possible to include patients or the public in the design or conduct of the study or in the reporting or dissemination of this work.

References

- 1.COVID data tracker: centers for disease control and prevention, 2021. Available: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#datatracker-home [Accessed 21 May 2021].

- 2.Pilishvili T, Fleming-Dutra KE, Farrar JL, et al. Interim Estimates of Vaccine Effectiveness of Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID-19 Vaccines Among Health Care Personnel - 33 U.S. Sites, January-March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:753–8. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7020e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scobie HM, Johnson AG, Suthar AB, et al. Monitoring Incidence of COVID-19 Cases, Hospitalizations, and Deaths, by Vaccination Status - 13 U.S. Jurisdictions, April 4-July 17, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021;70:1284–90. 10.15585/mmwr.mm7037e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard: World Health Organization, 2021. Available: https://covid19.who.int/ [Accessed 14 Nov 2021].

- 5.Dooling K, McClung N, Chamberland M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices' Interim Recommendation for Allocating Initial Supplies of COVID-19 Vaccine - United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1857–9. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6949e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.An C, Lim H, Kim D-W, et al. Machine learning prediction for mortality of patients diagnosed with COVID-19: a nationwide Korean cohort study. Sci Rep 2020;10:18716. 10.1038/s41598-020-75767-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, et al. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. BMJ 2015;350:g7594. 10.1136/bmj.g7594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tibshirani R. Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B 1996;58:267–88. 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1996.tb02080.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J Stat Softw 2010;33:1–22. 10.18637/jss.v033.i01 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Breiman L, Friedman JH, Olshen RA. Classification and regression trees. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 11.R Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedman JH, Tibshirani T, Narasimhan R, et al. Lasso and Elastic-Net Regularized Generalized Linear Models, 2021. Available: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/glmnet/glmnet.pdf [Accessed 22 Nov 2021].

- 13.Kuhn M. Building Predictive Models in R Using the caret Package. J Stat Softw 2008;28:1–26. 10.18637/jss.v028.i0527774042 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950;3:32–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tompkins LW, Lee AS, Ivory JC. As States Expand Access To the Vaccine, Hopes Rise Along With the Confusion. The New York Times 2021 Jan 16, 2021;6 2021.

- 16.Creech CB, Walker SC, Samuels RJ. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. JAMA 2021;325:1318–20. 10.1001/jama.2021.3199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wynants L, Van Calster B, Collins GS, et al. Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of covid-19: systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ 2020;369:m1328. 10.1136/bmj.m1328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jehi L, Ji X, Milinovich A, et al. Individualizing risk prediction for positive coronavirus disease 2019 testing: results from 11,672 patients. Chest 2020;158:1364–75. 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knight SR, Ho A, Pius R, et al. Risk stratification of patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO clinical characterisation protocol: development and validation of the 4C mortality score. BMJ 2020;370:m3339. 10.1136/bmj.m3339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo M, Liu J, Jiang W, et al. IL-6 and CD8+ T cell counts combined are an early predictor of in-hospital mortality of patients with COVID-19. JCI Insight 2020;5. 10.1172/jci.insight.139024. [Epub ahead of print: 09 07 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Higaki A. Potential multicollinearity among NLR and other variables in the prediction model for the COVID-19 mortality. Am J Emerg Med 2021;47:296. 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.04.068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watanabe M, Balena A, Tuccinardi D, et al. Central obesity, smoking habit, and hypertension are associated with lower antibody titres in response to COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2021:e3465 (published Online First: 2021/05/07). 10.1002/dmrr.3465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kennedy NA, Lin S, Goodhand JR, et al. Infliximab is associated with attenuated immunogenicity to BNT162b2 and ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in patients with IBD. Gut 2021;70:1884–93. 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Plante JA, Liu Y, Liu J, et al. Spike mutation D614G alters SARS-CoV-2 fitness. Nature 2021;592:116–21. 10.1038/s41586-020-2895-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vöhringer HS, Sanderson T, Sinnott M, et al. Genomic reconstruction of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in England. Nature 2021. 10.1038/s41586-021-04069-y. [Epub ahead of print: 14 Oct 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Waltz E. COVID vaccine makers brace for a variant worse than delta. Nature 2021;598:552–3. 10.1038/d41586-021-02854-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krause PR, Fleming TR, Longini IM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants and vaccines. N Engl J Med 2021;385:179–86. 10.1056/NEJMsr2105280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjresp-2021-001016supp001.pdf (77.7KB, pdf)

bmjresp-2021-001016supp002.pdf (80.4KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information.