Abstract

The oral microbiome in dogs is a complex community. Under some circumstances, it contributes to periodontal disease, a prevalent inflammatory disease characterized by a complex interaction between oral microbes and the immune system. Porphyromonas and Tannerella spp. are usually dominant in this disease. How the oral microbiome community is altered in periodontal disease, especially sub-dominant microbial populations is unclear. Moreover, how microbiome functions are altered in this disease has not been studied. In this study, we compared the composition and the predicted functions of the microbiome of the cavity of healthy dogs to those with from periodontal disease. The microbiome of both groups clustered separately, indicating important differences. Periodontal disease resulted in a significant increase in Bacteroidetes and reductions in Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria. Porphyromonas abundance increased 2.7 times in periodontal disease, accompanied by increases in Bacteroides and Fusobacterium. It was predicted that aerobic respiratory processes are decreased in periodontal disease. Enrichment in fermentative processes and anaerobic glycolysis were suggestive of an anaerobic environment, also characterized by higher lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis. This study contributes to a better understanding of how periodontal disease modifies the oral microbiome and makes a prediction of the metabolic pathways that contribute to the inflammatory process observed in periodontal disease.

Keywords: oral microbiome, periodontal disease, Porphyromonas, 16S rRNA

1. Introduction

Periodontal disease is an inflammatory, multifactorial disease that affects the tissues that support dental pieces. It involves complex interactions between microorganisms in the oral cavity and the host immune response [1]. In dogs, it is one of the most prevalent diseases worldwide, affecting around 70% of canine patients [2,3,4,5]. The microbiome of the canine oral cavity is diverse and complex. It comprises the microbiota of different niches such as oral mucosa, tongue, saliva, supragingival and subgingival plaque [6]. Each of these niches is different in its composition, and together they create a unique ecosystem. When this microbiome suffers certain imbalances, a dysbiosis state generates a favorable environment for pathogenic microorganisms, increasing the virulence of microorganisms present [7,8]. These alterations exacerbate the immune response of the host, contributing to chronic inflammatory states and giving rise to the pathologies such as periodontal disease [9]. The etiology of this disease involves multiple factors, including the dental plaque and the community of microorganisms present at the dental surface. These bacteria establish a biofilm, colonizing the gingival grooves and the root surface of the tooth, sometimes resulting in the loss of dental pieces [10]. Tartar or dental calculus is generated when this biofilm is mineralized, and despite not being the leading cause of inflammation, it acts as a retention factor for microorganisms in the biofilm [11,12,13]. In humans, as in dogs and cats, periodontal disease and its pathogenesis have been strongly related to microorganisms such as Porphyromonas sp. [14,15,16,17]. Other research indicates that Porphyromonas gulae, Tannerella forsythia, and Campylobacter rectus are dominant periodontal pathogens in dogs [18]. Certain studies have addressed the differences in the composition of the microbiome of the canine oral cavity, both healthy and pathological, elucidating important information to understand the state of dysbiosis that periodontal disease entails. The presence of Gram-negative bacteria has been associated with healthy dogs, and an increase in Gram-positive bacteria has been associated with dogs with moderate periodontal disease [6]. On the contrary, it has been observed that the increase of anaerobic Gram-negative bacteria in the supragingival and subgingival plaque is related to the release of enzymes and endotoxins during the formation of periapical lesions [19].

How the oral microbiome is altered in dogs is unclear, and the impact of periodontal disease on sub-dominant microbial populations is unclear. The objective of this study was to compare the composition and the predicted functions of the microbiome of the cavity of healthy dogs to those suffering from periodontal disease using 16S rRNA sequencing.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects and Inclusion Criteria

This study was approved by the Bioethics Committee at the Veterinary Clinic Los Avellanos (Approval Certificate HCVLA-010) and was carried out in one veterinary clinic, located in Independencia, Metropolitan Region, Chile (S33°24′54.4″ O70°39′56.7″). Samples were collected during the month of January 2021. Targeted sampling was performed to select 24 dogs, 12 with gingivitis or periodontitis and 12 without periodontal disease. Dogs older than two years were included, without distinction of breed or sex, without underlying pathologies and without antibiotic treatment at least three months before sampling.

The clinical examination of the oral cavity was performed by the same veterinarian, with prior authorization by informed consent. The presence or absence of gingivitis or periodontitis, gingival index (mild, moderate, severe) [20], dental calculus, and tooth exfoliation was evaluated during the clinical examination. In the group of healthy animals, all the assessed clinical signs were absent. In the periodontitis group, there were at least 4/6 clinical signs for inclusion. Data such as age, sex, race, body condition score (BS) [21] and type of diet were recorded for each patient (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the animals (M: male; F: female). Clinical diagnosis was classified in not observed (0) and observed (1). Diet type was Commercial Dry (CD), homemade (HM), and both (CD&HM).

| Classification | Code | Sex | Age (y) | Race | Weight (kg) | BS | Diet Type | Gingivitis or Periodontitis | Gingival Index | Dental Calculus | Halitosis | Tooth Exfoliation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Periodontium (H) |

1H | M | 2 | Mutt | 9.8 | 8 | CD&HM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2H | F | 4 | Mutt | 29 | 5 | CD&HM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 3H | M | 1 | Poodle | 7 | 5 | CD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4H | M | 2 | Mutt | 10 | 5 | CD&HM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 5H | F | 1 | Mutt | 20 | 5 | CD&HM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 6S | F | 2.5 | Labrador | 25 | 5 | CD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 7H | F | 1 | German Shepherd | 33 | 5 | CD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8H | M | 7 | Teckel | 5.8 | 5 | CD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 9H | M | 3 | Mutt | 17 | 5 | CD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 10H | M | 5 | Mutt | 21 | 5 | CD&HM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 11H | F | 2 | Mutt | 18 | 5 | CD&HM | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 12H | M | 3 | Maltese | 5 | 5 | CD | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Average H | 2.79 | 16.72 | 5.25 | |||||||||

| Periodontitis (P) | 1P | F | 8 | Mutt | 35 | 5 | CD | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2P | M | 7 | Poodle | 6.2 | 5 | CD | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 3P | M | 9 | Poodle | 4.9 | 5 | CD&HM | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 4P | F | 3 | Mutt | 20 | 5 | CD&HM | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 5P | M | 4 | Mutt | 17 | 5 | CD&HM | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 6P | F | 3 | Cocker Spaniel | 12.5 | 5 | CD&HM | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 7P | F | 6 | Teckel | 7 | 7 | CD | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 8P | F | 8 | Mutt | 6 | 5 | CD&HM | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 9P | F | 13 | Poodle | 8.8 | 7 | CD | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 10P | M | 8 | Maltese | 5 | 5 | CD&HM | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 11P | M | 6 | Chihuahua | 4.6 | 7 | CD&HM | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| 12P | F | 2 | Yorkshire | 3.5 | 5 | CD&HM | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Average P | 6.42 | 10.88 | 5.50 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

2.2. Analysis of the Oral Cavity Microbiome

The samples were obtained by swabbing the gingival margin of the right maxillary fourth premolar in the oral cavity, as previously described [22]. The swab was deposited in an Eppendorf tube with 1 mL of RNA later (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA). Before DNA extraction (Quick-DNA Fecal/Soil Microbe Miniprep Kit, Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA), each tube with its swab was placed in the disruption for 5 min using a Disruptor Genie device (Scientific Industries, Bohemia, NY, USA). DNA samples were diluted to 20 ng/µL in nuclease-free water (NanoDrop 2000c; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham MA, USA). DNA samples were submitted for Illumina MiSeq sequencing to the DNA Sequencing Services at Molecular Research (MR-DNA, Shallowater, TX, USA). The variable region V3-V4 gene of the 16S rRNA was amplified using primers 341F and 785R. A barcode was added to the forward primer for pooling multiple samples. The reaction was run for 30 cycles using the HotStarTaq Plus Master Mix Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). DNA samples were pooled and purified using Ampure XP microspheres (Agencourt Bioscience Corporation, Boston, MA, USA). DNA libraries were prepared using the TruSeq DNA LT Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed using the MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA).

2.3. Bioinformatics Analyses

Processed sequences were uploaded to the European Nucleotide Archive under the project code PRJEB47716. Bioinformatics analyses were done as previously described [23] with modifications. Sequences were filtered by quality and trimmed to 250 nucleotides and used to infer Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) employing the DADA2 v1.10 R package [24]. Taxonomy was assigned utilizing the SILVA database version 132 [25,26] and a Naïve Bayesian classifier [27]. The abundance of metabolic pathways and enzymes were inferred from the ASV table using the PICRUSt2 python package [28] and the MetaCyc database [29]. Differences in the relative abundance of taxa were assessed with the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test [30], and differences in the abundance of metabolic functions and pathways were evaluated with the Linear Discriminant Analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) method [31]. The significance level for all statistical analyses was p-value < 0.05.

3. Results

The oral microbiome of 24 adult dogs was analyzed in this study. We included 12 dogs without periodontitis (S) and 12 animals with periodontal disease (P). The latter presented significant signs of gingivitis, erythema, gingival bleeding, tartars, or halitosis (Table 1; p < 0.05). Both groups were not different regarding their body scores (BS), but the dog’s group without gingivitis or periodontitis had a younger age than the other group (Table 1; p < 0.05). None of the included subjects had oral cavity hygiene habits.

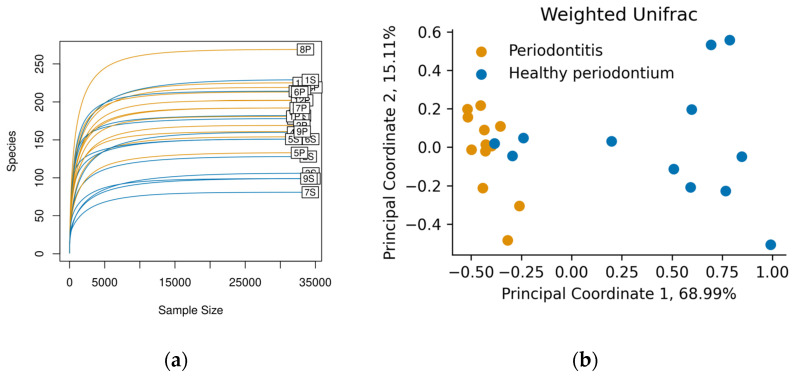

Swab samples were taken from the gingival margin in the oral cavity. After 16S rRNA sequencing, each sample contained approximately 35,000 reads, and we identified between 80 and 262 ASVs per sample (Figure 1a). The rarefaction curves showed saturation, indicating that the depth of sequencing was appropriate to describe the microbial composition in these groups.

Figure 1.

(a) Rarefaction curves for each sample show saturation of the identified Amplicon sequence variant (ASVs) (“Species” axis). Figure was made with the vegan R package, version 2.5-7; (b) Principal Coordinate Analysis of the Weighted Unifrac diversity metric. Colors represent animals in the Healthy periodontium group (S, Blue) and animals diagnosed with Periodontitis (P, orange).

Weighed Unifrac was used to compare the oral microbiome composition in both groups at the phylum level (Figure 1b). There was a clear clustering in the oral microbiome of dogs with periodontal disease, different from dogs with healthy periodontium. This last group showed broader microbiome distributions than diseased animals, who had a more similar microbiome composition (Figure 1b). The difference between groups was corroborated by ANOSIM and PERMANOVA tests (p < 0.05).

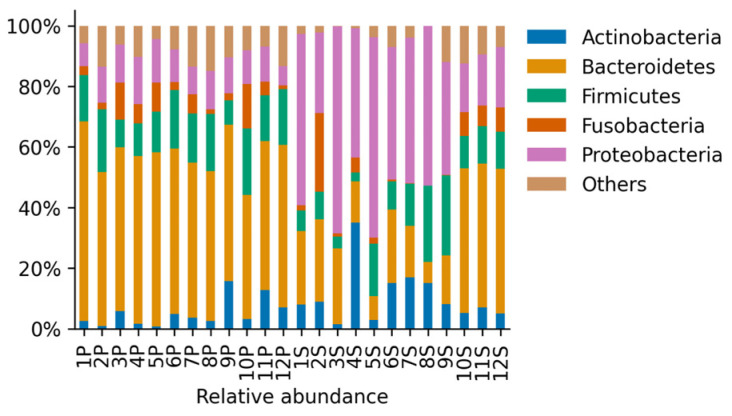

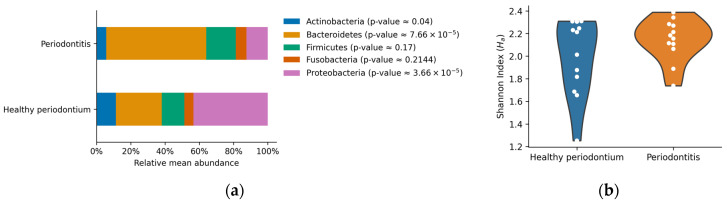

The most abundant phyla in both groups of animals were Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, and Proteobacteria (Figure 2). Other phyla were present below the 5% of the total abundance, contributing 0.08–14.84% in total (Figure 2). Dogs with periodontal disease presented a significant increase in Bacteroidetes relative abundance accompanied by a significant reduction in Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria relative abundance (p < 0.05, Figure 3a). These results showed important alterations at the phylum level in the oral microbiome of dogs with periodontal disease. However, no significant differences in the Shannon diversity between healthy and periodontal oral microbiomes were determined (p = 0.18; Figure 3b).

Figure 2.

Relative abundance of the identified phyla for samples derived from all animals in the Healthy periodontium group (S, n = 12) and in the Periodontitis group (P, n = 12). Phyla that were present less than 5% in any sample were aggregated and contributed up to approximately 15% of the relative abundance.

Figure 3.

(a) Relative mean abundance per group. Bars represent the arithmetic mean for the most abundant phyla (over 5% of the relative abundance). p-values of the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U-test are shown between parentheses; (b) Violin plots of the Shannon diversity index. Each dot represents the determined index per sample, and the shape represents an estimated probability density function of the data.

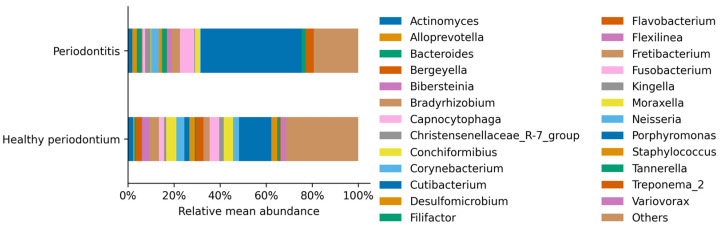

The most abundant genus in healthy and periodontal disease dogs was Porphyromonas, belonging to the Bacteroidetes phylum (Figure 4). The Porphyromonas relative abundance increased 2.7 times from 12.9% up to 34.7% of total sequences in periodontal disease, concordant with previous observations (Table 2). This dominance was accompanied by a significant increase in other genera such as Bacteroides and Fusobacterium, and a significant decrease in less represented genera, such as Staphylococcus and Streptococcus (Table 2; p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Relative mean abundance of each identified genus per treatment. Genus that was present less than 1% in any sample were aggregated, contributing 31.35% in the healthy periodontium individuals and 19.30% in the group of animals with periodontitis.

Table 2.

Relative mean abundance of the identified genus in animals on the healthy periodontium (S) and with periodontal disease (P) groups. The table shows only the genera with significant changes (p-values < 0.05) and ratios different from 0.

| Genus | Healthy Periodontium (Mean%) |

Periodontitis (Mean%) |

Ratio S/P | Ratio P/S | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acholeplasma | 0.055 ± 0.19 | 0.34 ± 0.21 | 0.16 | 6.06 | 0.00116 |

| Acinetobacter | 0.27 ± 0.44 | 0.0015 ± 0.0038 | 177.32 | 0.01 | 0.00015 |

| Alloprevotella | 0.46 ± 0.58 | 1.7 ± 3.1 | 0.27 | 3.74 | 0.04040 |

| Bacteroides | 0.62 ± 1.1 | 1.6 ± 1.7 | 0.38 | 2.62 | 0.01414 |

| Bosea | 0.1 ± 0.31 | 0.0031 ± 0.0062 | 32.16 | 0.03 | 0.01828 |

| Bradyrhizobium | 3.9 ± 6.6 | 0.007 ± 0.0099 | 552.06 | 0.000795 | 0.00042 |

| Brevundimonas | 0.079 ± 0.18 | 0.015 ± 0.015 | 5.3 | 0.19 | 0.03289 |

| Campylobacter | 0.24 ± 0.41 | 0.33 ± 0.2 | 0.73 | 1.38 | 0.04374 |

| Candidatus Tammella | 0.00049 ± 0.0017 | 0.13 ± 0.14 | 0.0038 | 259.03 | 0.00080 |

| Catonella | 0.0076 ± 0.024 | 0.17 ± 0.17 | 0.05 | 21.77 | 0.00024 |

| Christensenellaceae R-7 group | 0.76 ± 1.1 | 2 ± 2.3 | 0.38 | 2.62 | 0.02258 |

| Cutibacterium | 2 ± 3.3 | 0.0021 ± 0.0051 | 950.79 | 0.0011 | 0.00039 |

| Defluviitaleaceae UCG-011 | 0.16 ± 0.21 | 0.72 ± 0.46 | 0.23 | 4.4 | 0.00134 |

| Desulfobulbus | 0.00079 ± 0.0027 | 0.35 ± 0.52 | 0.0023 | 447.73 | 0.00101 |

| Desulfoplanes | 0.002 ± 0.0052 | 0.14 ± 0.19 | 0.01 | 69.55 | 0.04242 |

| Desulfovibrio | 0.31 ± 0.57 | 1.3 ± 1.4 | 0.24 | 4.12 | 0.00426 |

| Ezakiella | 0.021 ± 0.058 | 0.35 ± 0.51 | 0.06 | 16.39 | 0.00081 |

| Fastidiosipila | 0.00051 ± 0.0018 | 0.11 ± 0.12 | 0.0046 | 216.92 | 0.00080 |

| Filifactor | 0.57 ± 0.75 | 1.8 ± 1.4 | 0.32 | 3.1 | 0.01018 |

| Finegoldia | 0.93 ± 1.6 | 0.00076 ± 0.0026 | 1233.58 | 0.00082 | 0.00253 |

| Flexilinea | 0.22 ± 0.48 | 1.8 ± 1.7 | 0.12 | 8.01 | 0.00072 |

| Fusibacter | 0.39 ± 0.71 | 0.89 ± 0.64 | 0.43 | 2.31 | 0.01003 |

| Gemella | 0.39 ± 1 | 0.0062 ± 0.015 | 62.64 | 0.02 | 0.03913 |

| H1 | 0.027 ± 0.074 | 0.16 ± 0.12 | 0.17 | 5.95 | 0.00121 |

| Helcococcus | 0.0051 ± 0.0055 | 0.47 ± 0.64 | 0.01 | 92.4 | 0.00165 |

| Luteibacter | 0.1 ± 0.17 | 0.022 ± 0.0098 | 4.45 | 0.22 | 0.00610 |

| Massilia | 1.1 ± 3.5 | 0.055 ± 0.015 | 19.7 | 0.05 | 0.00244 |

| Odoribacter | 0.0024 ± 0.0062 | 0.29 ± 0.54 | 0.01 | 118.57 | 0.00012 |

| Pelomonas | 1.7 ± 3 | 0.0015 ± 0.0051 | 1127.24 | 0.00088 | 0.00253 |

| Peptoanaerobacter | 0.19 ± 0.42 | 0.37 ± 0.35 | 0.52 | 1.92 | 0.03371 |

| Peptococcus | 0.019 ± 0.043 | 0.61 ± 0.56 | 0.03 | 32.56 | 0.00008 |

| Peptoniphilus | 0.27 ± 0.46 | 0.092 ± 0.22 | 2.94 | 0.34 | 0.04230 |

| Peptostreptococcus | 0.014 ± 0.018 | 0.87 ± 1.1 | 0.02 | 61.97 | 0.00086 |

| Porphyromonas | 13 ± 15 | 39 ± 11 | 0.32 | 3.1 | 0.00048 |

| Prevotella 7 | 0.0022 ± 0.0076 | 0.24 ± 0.36 | 0.01 | 110.08 | 0.00038 |

| Propionivibrio | 0.035 ± 0.072 | 0.092 ± 0.082 | 0.38 | 2.63 | 0.00997 |

| Proteiniphilum | 0.0022 ± 0.0076 | 0.22 ± 0.37 | 0.01 | 100.8 | 0.00314 |

| Proteocatella | 0.2 ± 0.45 | 0.45 ± 0.56 | 0.45 | 2.22 | 0.01885 |

| Pseudarthrobacter | 0.39 ± 1.1 | 0.0075 ± 0.021 | 51.86 | 0.02 | 0.01563 |

| Pseudomonas | 0.94 ± 2.8 | 0.073 ± 0.018 | 12.85 | 0.08 | 0.00244 |

| Rikenellaceae RC9 gut group | 0.0025 ± 0.0059 | 0.2 ± 0.25 | 0.01 | 79.88 | 0.00015 |

| Roseburia | 0.0084 ± 0.026 | 0.22 ± 0.23 | 0.04 | 26.23 | 0.00004 |

| Ruminiclostridium 9 | 0.0011 ± 0.0037 | 0.47 ± 0.93 | 0.0023 | 442.97 | 0.00101 |

| Ruminococcaceae UCG-004 | 0.08 ± 0.21 | 0.35 ± 0.47 | 0.23 | 4.41 | 0.04291 |

| Salinisphaera | 0.99 ± 1.5 | 0.0015 ± 0.0036 | 647.56 | 0.0015 | 0.00280 |

| Sediminispirochaeta | 0.0049 ± 0.017 | 0.045 ± 0.045 | 0.11 | 9.16 | 0.00587 |

| Sphaerochaeta | 0.0081 ± 0.028 | 0.034 ± 0.071 | 0.24 | 4.21 | 0.04809 |

| Sphingomonas | 0.13 ± 0.13 | 0.074 ± 0.017 | 1.8 | 0.56 | 0.01202 |

| Staphylococcus | 2.4 ± 3.3 | 0.0027 ± 0.0067 | 873.18 | 0.0011 | 0.00009 |

| Streptococcus | 1.7 ± 1.9 | 0.079 ± 0.24 | 21.19 | 0.05 | 0.00203 |

| Suttonella | 0.16 ± 0.15 | 0.078 ± 0.028 | 2.02 | 0.49 | 0.04639 |

| Treponema 2 | 0.35 ± 0.57 | 3 ± 1.8 | 0.12 | 8.48 | 0.00019 |

| Variovorax | 2.2 ± 3.1 | 0.026 ± 0.024 | 84.26 | 0.01 | 0.00006 |

| Verticia | 0.12 ± 0.026 | 0.072 ± 0.028 | 1.73 | 0.58 | 0.00016 |

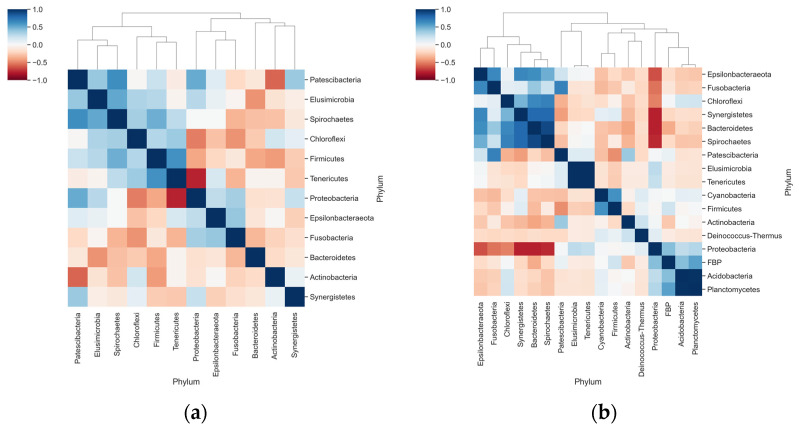

Correlation analyses suggested a negative interaction between Proteobacteria and Tenericutes in dogs with periodontal disease (Figure 5a). Stronger correlations were observed in healthy animals: negative interactions between Proteobacteria with Bacteroidetes and Fusobacteria, and positive correlations in the abundance of Bacteroides with Synergistetes and Spirochetes (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Correlation and clustering analyses for the relative abundance of phyla in each group. (a) Heatmap shows the Pearson Correlation Coefficient determined for the relative abundance of phyla only in animals with periodontal disease; (b) Pearson correlation coefficients of the relative abundance within animals in the Healthy periodontium group.

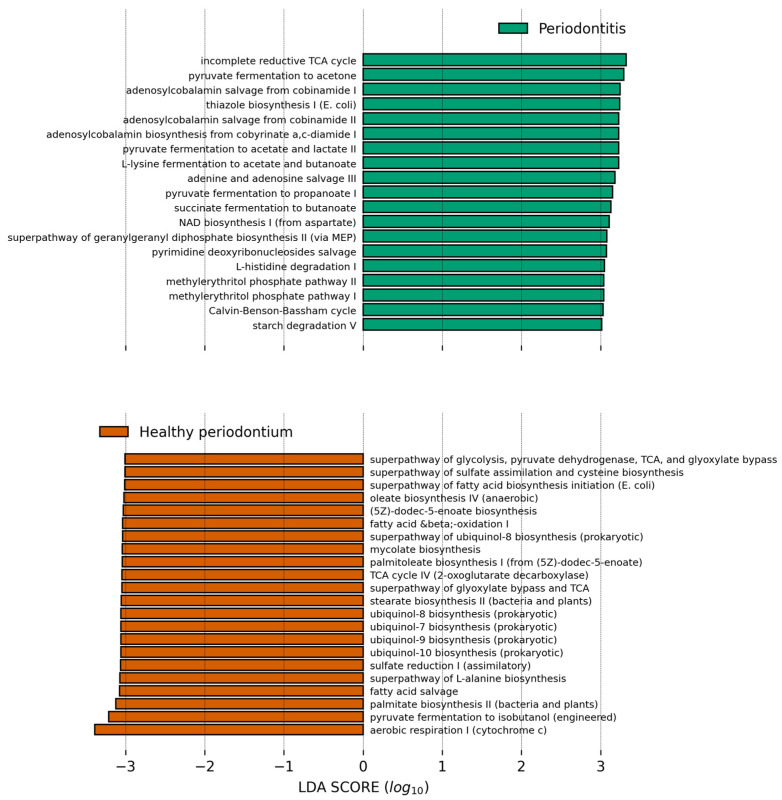

We finally used PICRUSt2 to predict the abundance of major metabolic pathways in the microbiome of both groups and the differential abundance was analyzed with LEfSe (Figure 6). The healthy oral microbiome was enriched in aerobic respiration pathways, especially the glyoxylate bypass and ubiquinol biosynthesis. This enrichment also suggests that aerobic respiration processes are decreased in periodontal disease. The healthy oral microbiome was also enriched in fatty acid biosynthesis (Figure 6). In contrast, functions that are more abundant of the studied animals with periodontal disease compared to animals in the healthy gum group were lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis, coenzyme B12 (adenosylcobalamin) biosynthesis, anaerobic glycolysis, and fermentative processes from pyruvate.

Figure 6.

Bar plot showing the PICRUSt2 inferred pathways which relative abundance is higher in the respective group compared to the other and have a Linear Discriminant Analysis score higher than 3.0. Data was analyzed in the Galaxy Server at https://huttenhower.sph.harvard.edu/galaxy/ accessed on 16 October 2021, and results were plotted with a modified script from https://github.com/SegataLab/lefse, accessed on 16 October 2021.

4. Discussion

The healthy canine oral microbiome is a diverse, structured community [32]. There is only a small set of studies addressing the composition of the oral microbiome in dogs. This and other studies differ in several aspects, such as the number of animals recruited and sequencing techniques. One essential aspect of studying this community is sampling. It is known that communities in the oral cavity vary significantly across sections in the dental plaque (supragingival, subgingival, saliva) [33,34], however, these studies still have an unrepresentative sample size. Another limitation of this study is the significant difference in the age of the animals, with diseased dogs being older compared to healthy animals. While we cannot rule out that age is a confounding factor in our results, no studies indicate how the oral dog microbiome changes across age, so it would be interesting to have future studies that include animals of different age groups. There is evidence in humans and other models that indicate that the oral microbiome shows a decrease in diversity and increase in taxa, such as Tannerella and Porphyromonas [35,36]. Important variations in its composition have been observed in dogs compared to healthy oral microbiomes by other studies. It has been suggested that periodontal disease in dogs is associated with a dominance of Gram-positive bacteria [37]. However, this and other studies show that the healthy and periodontal oral microbiome are dominated by two phyla characterized by Gram-negative bacteria, Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes [38]. The main outcome observed at the phylum level between groups is an expansion in Bacteroidetes, especially Porphyromonas, and a reduction in Proteobacteria. A modest increase in the Firmicutes phylum was also determined in our cohort. A negative correlation between Proteobacteria and Bacteroidetes sustains the significant changes observed at the phylum level in periodontal disease in dogs.

The canine oral microbiome differs significantly from the human oral microbiome, with only a 16.4% coincidence of bacterial taxa [32]. Likewise, the formation of biofilms in humans has been widely studied, where species in the Streptococcus genus have a key role in its development, formation, and maturation of bacterial plaque [39,40,41]. For example, S. mutans is characterized by the ability to form biofilms and secrete virulence factors that facilitate caries formation and S. sanguinis, known as a pioneer colonizer of oral biofilms [42]. However, it is recognized that in the formation of dental caries there is a dysbiosis of the oral microbiota, where different bacterial species participate that perpetuate and increase this condition [43]. In dogs, the Streptococcus genus appears to be subdominant. Neisseria and Corynebacterium species have also been highlighted in biofilm formation [39]. In this study, we observed that while they have a representation between 2–3% in healthy microbiomes, it is decreased during periodontal disease.

The most abundant genus in both healthy and diseased dogs was Porphyromonas, increasing its abundance 2.7 times in diseased dogs. Porphyromonas species can modulate the host’s innate immune response processes, resulting in the exacerbation of interleukins, cyclooxygenase 2 directly related to periodontal tissue damage [44,45]. Porphyromonas gingivalis is one of the most studied bacteria in humans regarding its development pathways for periodontal disease. It is an opportunistic pathogenic bacterium, which requires anaerobic conditions and nutrients for its growth in vitro. It obtains energy by the fermentation of amino acids, which contribute to its growth in inflammatory environments due to the release of products resulting from tissue damage, including peptides. In addition, it can invade gingival epithelial cells, periodontal ligament fibroblasts, immune cells, and osteoblasts [46].

This is interesting, since the bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) derived from gram negative bacteria, such as P. gingivalis, initiates the acute phase response, thus upregulating the expression of metalloproteinase, increasing the permeability of the gingival epithelium, and altering the humoral immune response, collectively contributing to the periodontal disease [47]. On the other hand, monocytes produce IL-1, TNF-α and β, which induce the destruction of soft tissues of the periodontium, which, associated with the secretion of PGE2 alpha by fibroblasts, generate bone resorption [48].

In dogs, P. gingivalis and other bacteria such as Tannerella forysthia and Campylobacter rectus are part of the periodontal oral microbiome [2,18]. In companion animals such as dogs, bacteria found in the highest proportion in periodontal disease is Porphyromonas gulae [38,40,41] and Porphyromona cangingivalis [34,49,50]. The striking differences in the oral microbiome of healthy and diseased animals were also reflected in changes in the predicted metabolic functions. Healthy oral microbiomes are characterized by a dominance of aerobic microorganisms (such as Proteobacteria) compared to the microbiomes of dogs with periodontal disease. In the latter, there is an increase in facultative anaerobic and strict anaerobic bacteria such as Porphyromonas and Tannerella [37]. Firmicutes also see an increase in their representation in periodontal disease, which might be favored by a more anaerobic environment, contributing to increments in anaerobic glycolysis and fermentative processes. In diseased dogs, we observed a putative higher production of lipopolysaccharide, a high inflammatory bacterial molecule. Its increase probably contributes to invasion and oral tissue destruction, as it is observed in this disease. In humans, increases in LPS have been related to the origin of the pulp inflammatory process and processes associated with the destruction of alveolar bone in advanced periodontal diseases [51,52].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.T.; methodology, P.T. and C.F.-Y.; software, R.S.; validation, D.G., C.F.-Y. and R.S.; formal analysis, R.S. and C.R.-S.; investigation, C.R.-S. and C.F-. Y.; resources, P.T.; data curation, R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, P.T.; writing—review and editing, D.G. and C.R.-S. visualization, R.S.; supervision, D.G.; project administration, P.T.; funding acquisition, P.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ANID. PAI # 77190079.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee HCVLA (protocol code HCVLA-010 and date of approval 10 January 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the dogs’ owner involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/PRJEB47716, accessed on 24 September 2021.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Chen W.-P., Chang S.-H., Tang C.-Y., Liou M.-L., Tsai S.-J.J., Lin Y.-L. Composition analysis and feature selection of the oral microbiota associated with periodontal disease. BioMed Res. Int. 2018;2018:1–14. doi: 10.1155/2018/3130607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Bello A., Buonavoglia A., Franchini D., Valastro C., Ventrella G., Greco M.F., Corrente M. Periodontal disease associated with red complex bacteria in dogs. J. Small Anim. Pr. 2014;55:160–163. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marshall M.D., Wallis C.V., Milella L., Colyer A., Tweedie A.D., Harris S. A longitudinal assessment of periodontal disease in 52 miniature schnauzers. BMC Vet. Res. 2014;10:166. doi: 10.1186/1746-6148-10-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stella J.L., Bauer A.E., Croney C.C. A cross-sectional study to estimate prevalence of periodontal disease in a population of dogs (Canis familiaris) in commercial breeding facilities in Indiana and Illinois. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0191395. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wallis C., Holcombe L.J. A review of the frequency and impact of periodontal disease in dogs. J. Small Anim. Pr. 2020;61:529–540. doi: 10.1111/jsap.13218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruparell A., Inui T., Staunton R., Wallis C., Deusch O., Holcombe L.J. The canine oral microbiome: Variation in bacterial populations across different niches. BMC Microbiol. 2020;20:1–13. doi: 10.1186/s12866-020-1704-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beikler T., Bunte K., Chan Y., Weiher B., Selbach S., Peters U., Klocke A., Watt R., Flemmig T. Oral microbiota transplant in dogs with naturally occurring periodontitis. J. Dent. Res. 2021;100:764–770. doi: 10.1177/0022034521995423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruparell A., Wallis C., Haydock R., Cawthrow A., Holcombe L.J. Comparison of subgingival and gingival margin plaque microbiota from dogs with healthy gingiva and early periodontal disease. Res. Vet. Sci. 2021;136:396–407. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2021.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy M., Kolodziejczyk A.A., Thaiss C.A., Elinav E. Dysbiosis and the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2017;17:219–232. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Freitas C.O.T., Gomes-Filho I.S., Naves R.C., da Rocha Nogueira Filho G., da Cruz S.S., de Souza Teles Santos C.A., Dunningham L., de Miranda L.F., da Silva Barbosa M.D. Influence of periodontal therapy on C-reactive protein level: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2012;20:1–8. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572012000100002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kačírová J. In: Dental Biofilm as Etiological Agent of Canine Periodontal Disease. Maďar M., editor. IntechOpen; Rijeka, Croatia: 2020. p. Ch. 15. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Booij-Vrieling H.E., van der Reijden W.A., Houwers D.J., de Wit W.E.A.J., Bosch-Tijhof C.J., Penning L.C., van Winkelhoff A.J., Hazewinkel H.A.W. Comparison of periodontal pathogens between cats and their owners. Vet. Microbiol. 2010;144:147–152. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pereira dos Santos J.D., Cunha E., Nunes T., Tavares L., Oliveira M. Relation between periodontal disease and systemic diseases in dogs. Res. Vet. Sci. 2019;125:136–140. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nomura R., Shirai M., Kato Y., Murakami M., Nakano K., Hirai N., Mizusawa T., Naka S., Yamasaki Y., Matsumoto-Nakano M., et al. Diversity of fimbrillin among Porphyromonas gulae clinical isolates from Japanese dogs. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2012;74:885–891. doi: 10.1292/jvms.11-0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiorillo L., Cervino G., Laino L., D’Amico C., Mauceri R., Tozum T.F., Gaeta M., Cicciù M. Porphyromonas gingivalis, periodontal and systemic implications: A systematic review. Dent. J. 2019;7:114. doi: 10.3390/dj7040114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gawron K., Wojtowicz W., Łazarz-Bartyzel K., Łamasz A., Qasem B., Mydel P., Chomyszyn-Gajewska M., Potempa J., Mlynarz P. Metabolomic status of the oral cavity in chronic periodontitis. In Vivo. 2019;33:1165–1174. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwashita N., Nomura R., Shirai M., Kato Y., Murakami M., Matayoshi S., Kadota T., Shirahata S., Ohzeki L., Arai N., et al. Identification and molecular characterization of Porphyromonas gulae fimA types among cat isolates. Vet. Microbiol. 2019;229:100–109. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maruyama N., Mori A., Shono S., Oda H., Sako T. Evaluation of changes in periodontal bacteria in healthy dogs over 6 months using quantitative real-time PCR. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2018;21:127–132. doi: 10.24425/119030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Özavci V., Erbas G., Parin U., Yüksel H.T., Kirkan Ş. Molecular detection of feline and canine periodontal pathogens. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2019;8:100069. doi: 10.1016/j.vas.2019.100069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Löe H. The Gingival Index, the Plaque Index and the Retention Index Systems. J. Periodontol. 1967;38:610–616. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6_part2.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chun J.L., Bang H.T., Ji S.Y., Jeong J.Y., Kim M., Kim B., Lee S.D., Lee Y.K., Reddy K.E., Kim K.H. A simple method to evaluate body condition score to maintain the optimal body weight in dogs. J Anim Sci Technol. 2019;61:366–370. doi: 10.5187/jast.2019.61.6.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato Y., Shirai M., Murakami M., Mizusawa T., Hagimoto A., Wada K., Nomura R., Nakano K., Ooshima T., Asai F. Molecular detection of human periodontal pathogens in oral swab specimens from dogs in Japan. J. Vet. Dent. 2011;28:84–89. doi: 10.1177/089875641102800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thomson P., Santibañez R., Aguirre C., Galgani J.E., Garrido D. Short-term impact of sucralose consumption on the metabolic response and gut microbiome of healthy adults. Br. J. Nutr. 2019;122:856–862. doi: 10.1017/S0007114519001570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Callahan B.J., McMurdie P.J., Rosen M.J., Han A.W., Johnson A.J.A., Holmes S.P. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quast C., Pruesse E., Yilmaz P., Gerken J., Schweer T., Yarza P., Peplies J., Glöckner F.O. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D590–D596. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yilmaz P., Parfrey L.W., Yarza P., Gerken J., Pruesse E., Quast C., Schweer T., Peplies J., Ludwig W., Glöckner F.O. The SILVA and “All-species Living Tree Project (LTP)” taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D643–D648. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Q., Garrity G.M., Tiedje J.M., Cole J.R. Naïve Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–5267. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00062-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Douglas G.M., Maffei V.J., Zaneveld J.R., Yurgel S.N., Brown J.R., Taylor C.M., Huttenhower C., Langille M.G.I. PICRUSt2 for prediction of metagenome functions. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:685–688. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0548-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caspi R., Billington R., Ferrer L., Foerster H., Fulcher C.A., Keseler I.M., Kothari A., Krummenacker M., Latendresse M., Mueller L.A., et al. The MetaCyc database of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc collection of pathway/genome databases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:D471–D480. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mann H.B., Whitney D.R. On a test of whether one of two random variables is stochastically larger than the other. Ann. Math. Stat. 1947;18:50–60. doi: 10.1214/aoms/1177730491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Segata N., Izard J., Waldron L., Gevers D., Miropolsky L., Garrett W.S., Huttenhower C. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dewhirst F.E., Klein E.A., Thompson E.C., Blanton J.M., Chen T., Milella L., Buckley C.M.F., Davis I.J., Bennett M.-L., Marshall-Jones Z.V. The canine oral microbiome. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36067. doi: 10.1371/annotation/c2287fc7-c976-4d78-a28f-1d4e024d568f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oba P.M., Carroll M.Q., Alexander C., Valentine H., Somrak A.J., Keating S.C.J., Sage A.M., Swanson K.S. Microbiota populations in supragingival plaque, subgingival plaque, and saliva habitats of adult dogs. Anim. Microbiome. 2021;3:38. doi: 10.1186/s42523-021-00100-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Niemiec B.A., Gawor J., Tang S., Prem A., Krumbeck J.A. The bacteriome of the oral cavity in healthy dogs and dogs with periodontal disease. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2022:1–9. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.21.02.0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lira-Junior R., Åkerman S., Klinge B., Boström E.A., Gustafsson A. Salivary microbial profiles in relation to age, periodontal, and systemic diseases. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0189374. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.An J.Y., Darveau R., Kaeberlein M. Oral health in geroscience: Animal models and the aging oral cavity. GeroScience. 2017;40:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11357-017-0004-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis I.J., Wallis C., Deusch O., Colyer A., Milella L., Loman N., Harris S.A. Cross-sectional survey of bacterial species in plaque from client owned dogs with healthy gingiva, gingivitis, or mild periodontitis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e83158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gadê-Neto C.R., Rodrigues R.R., Louzada L.M., Arruda-Vasconcelos R., Teixeira F.B., Viana Casarin R.C., Gomes B.P. Microbiota of periodontal pockets and root canals in induced experimental periodontal disease in dogs. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2019;10:e12439. doi: 10.1111/jicd.12439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holcombe L.J., Patel N., Colyer A., Deusch O., O’Flynn C., Harris S. Early canine plaque biofilms: Characterization of key bacterial interactions involved in initial colonization of enamel. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e113744. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Valm A.M. The structure of dental plaque microbial communities in the transition from health to dental caries and periodontal disease. J. Mol. Biol. 2019;431:2957–2969. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lyu X., Wang L., Shui Y., Jiang Q., Chen L., Yang W., He X., Zeng J., Li Y. Ursolic acid inhibits multi-species biofilms developed by Streptococcus mutans, Streptococcus sanguinis, and Streptococcus gordonii. Arch. Oral Biol. 2021;125:105107. doi: 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2021.105107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao W.-W., Zan K., Wu J.-Y., Gao W., Yang J., Ba Y.-Y., Wu X., Chen X.-Q. Antibacterial triterpenoids from the leaves of Ilex hainanensis Merr. Nat. Prod. Res. 2019;33:2435–2439. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2018.1452010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi N., Nyvad B. The Role of Bacteria in the Caries Process: Ecological Perspectives. J. Dent. Res. 2010;90:294–303. doi: 10.1177/0022034510379602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.de Araújo A.A., de Morais H.B., de Medeiros C.A.C.X., de Castro Brito G.A., Guedes P.M.M., Hiyari S., Pirih F.Q., de Araújo Júnior R.F. Gliclazide reduced oxidative stress, inflammation, and bone loss in an experimental periodontal disease model. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2019;27:e20180211. doi: 10.1590/1678-7757-2018-0211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nomura R., Inaba H., Yasuda H., Shirai M., Kato Y., Murakami M., Iwashita N., Shirahata S., Yoshida S., Matayoshi S., et al. Inhibition of Porphyromonas gulae and periodontal disease in dogs by a combination of clindamycin and interferon alpha. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:3113. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-59730-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Andrade K.Q., Almeida-Da-Silva C.L.C., Coutinho-Silva R. Immunological pathways triggered by Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum: Therapeutic possibilities? Mediat. Inflamm. 2019;2019:1–20. doi: 10.1155/2019/7241312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aziz J., Rahman M.T., Vaithilingam R.D. Dysregulation of metallothionein and zinc aggravates periodontal diseases. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2021;66:126754. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2021.126754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guimaraes-Stabili M.R., de Medeiros M.C., Rossi D., Camilli A.C., Zanelli C.F., Valentini S.R., Spolidorio L.C., Kirkwood K.L., Rossa C. Silencing matrix metalloproteinase-13 (Mmp-13) reduces inflammatory bone resorption associated with LPS-induced periodontal disease in vivo. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021;25:3161–3172. doi: 10.1007/s00784-020-03644-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wallis C., Marshall M., Colyer A., O’Flynn C., Deusch O., Harris S. A longitudinal assessment of changes in bacterial community composition associated with the development of periodontal disease in dogs. Vet. Microbiol. 2015;181:271–282. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.O’Flynn C., Deusch O., Darling A.E., Eisen J.A., Wallis C., Davis I.J., Harris S.J. Comparative genomics of the genus Porphyromonas identifies adaptations for heme synthesis within the prevalent canine oral species Porphyromonas cangingivalis. Genome Biol. Evol. 2015;7:3397–3413. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evv220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Aquino-Martinez R., Rowsey J.L., Fraser D.G., Eckhardt B.A., Khosla S., Farr J.N., Monroe D.G. LPS-induced premature osteocyte senescence: Implications in inflammatory alveolar bone loss and periodontal disease pathogenesis. Bone. 2020;132:115220. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2019.115220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ramenzoni L.L., Annasohn L., Miron R.J., Attin T., Schmidlin P.R. Combination of enamel matrix derivative and hyaluronic acid inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory response on human epithelial and bone cells. Clin. Oral Investig. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00784-021-04152-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/PRJEB47716, accessed on 24 September 2021.