Abstract

The pandemic of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome 2 coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is a continuing worldwide threat to human health and social economy. Historically, SARS-CoV-2 follows SARS and MERS as the third coronavirus spreading across borders and continents, but far more dangerous with long-lasting symptomatic consequences. The current situation is strong evidence that coronaviruses will continue to be pathogens of consequence in the future, thus calling for the development of neutralizing antibody-based prophylactics and therapeutics for prevention and treatment of COVID-19 and other human coronavirus diseases. This review summarized the progresses of developing neutralizing monoclonal antibodies against infection of SARS-CoV-2, SARS-CoV, and MERS-CoV, and discussed their potential applications in prevention and treatment of COVID-19 and other human coronavirus diseases.

Current Opinion in Virology 2022, 53:101199

This review comes from a themed issue on Anti-viral strategies (2022)

Edited by Zhong Huang and Qiao Wang

For complete overview about the section, refer Anti-viral strategies (2022)

Available online 30th December 2021

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coviro.2021.12.015

1879-6257/© 2021 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Introduction

By the time SARS-CoV-2 (originally named 2019-nCoV by WHO) (https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019) first emerged in late 2019 [1], seven human coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV in 2002/2003 (https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/summary-of-probable-sars-cases-with-onset-of-illness-from-1-november-2002-to-31-july-2003) and MERS-CoV in 2012 (https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2021-DON317), had caused the outbreaks of severe coronavirus diseases a worldwide. However, COVID-19, caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection, has posed more serious threat to public health, social stability and economy development. Presently, many vaccines against COVID-19 are in the clinical trials (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=vaccine&cond=Covid19&age_v=&gndr=&type=&rslt=&phase=2&phase=3&Search=Apply), and some have already applied for and obtained emergency use authorization. Cases of side effects after vaccination have been reported. This means that safety and efficacy, particularly in view of the growing number of mutant strains diverging from wild type [2••], and length of immunization still need further study with more data. Beyond vaccine development, antibody cocktails have shown some efficacy against viral mutants [2••]. Fully human antibodies can accurately and efficiently identify antigens with few side effects in humans. Some neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (NMAbs) have also entered clinical trials (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?term=antibody&cond=Covid19&age_v=&gndr=&type=&rslt=&Search=Apply). In view of the importance of NMAbs in the prevention and treatment of coronavirus diseases, this review summarizes the progresses of developing NMAbs against SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2, providing scientific knowledge about these NMAbs to combat the current COVID-19 pandemic and future emerging and re-emerging coronavirus diseases.

Key targets of coronavirus NMAbs

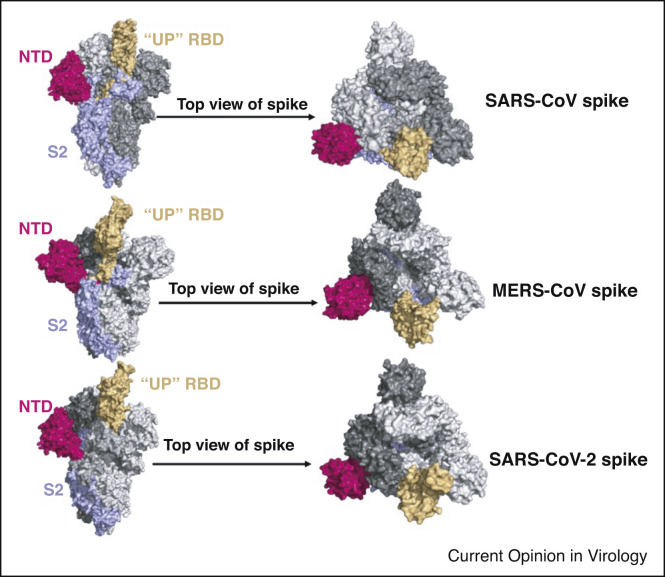

The coronavirus spike (S) glycoprotein is the primary immunogenic target for the design of neutralizing antibodies. The trimeric S protein is a type I fusion transmembrane protein which mediates virus binding to corresponding receptors and finally entry into host cells. In the case of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2, they recognize the same receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), whereas MERS-CoV S protein binds to dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4). The S protein trimer comprises three copies of an S1 subunit that contains the N-terminal domain (NTD) and receptor binding domain (RBD) and three copies of S2 [3, 4, 5, 6,7••,8]. The RBD has two conformational states, the closed ‘down’ state, which hides the receptor-binding regions, and the open ‘up’ state, which exposes the determinants of receptor binding (Figure 1 ). Finally, the S2 subunit mediates the fusion of coronavirus and host cell membrane [9••,10].

Figure 1.

The crystal structure of S glycoproteins with one receptor-binding domain (RBD); up conformation of three coronaviruses that cause severe symptoms. The order of crystal structures is SARS-CoV S, PDB: 6vyb; (5x5f) MERS-CoV S, PDB: 5x5f and SARS-CoV-2 S, PDB: 7kj5, respectively. In one S glycoprotein monomer, N-terminal domain (NTD) is shown in purple, RBD is shown in earth yellow, and S2 is shown in wathet blue. The other two are shown in gray.

NMAbs against SARS-CoV

Human NMAbs against SARS-CoV

NMAbs identified by screening of antibody libraries

As the SARS outbreak during 2002/2003, some fully human-derived NMAbs targeting the RBD were identified from nonimmune phage libraries of human antibodies [11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16], such as 80R, CR3014, and m396 (Figure 2 a) (Table 1 ). The S protein of SARS-CoV continued to mutate during transmission, but researchers found that CR3014 did not neutralize all mutant strains. However, researchers also discovered that the combination of CR3022 and CR3014, now known as an antibody cocktail, could effectively neutralize multiple mutant strains [17]. B1 is the first S2-targeting mAb screened from an antibody library of SARS-CoV convalescent patients [18] (Table 1).

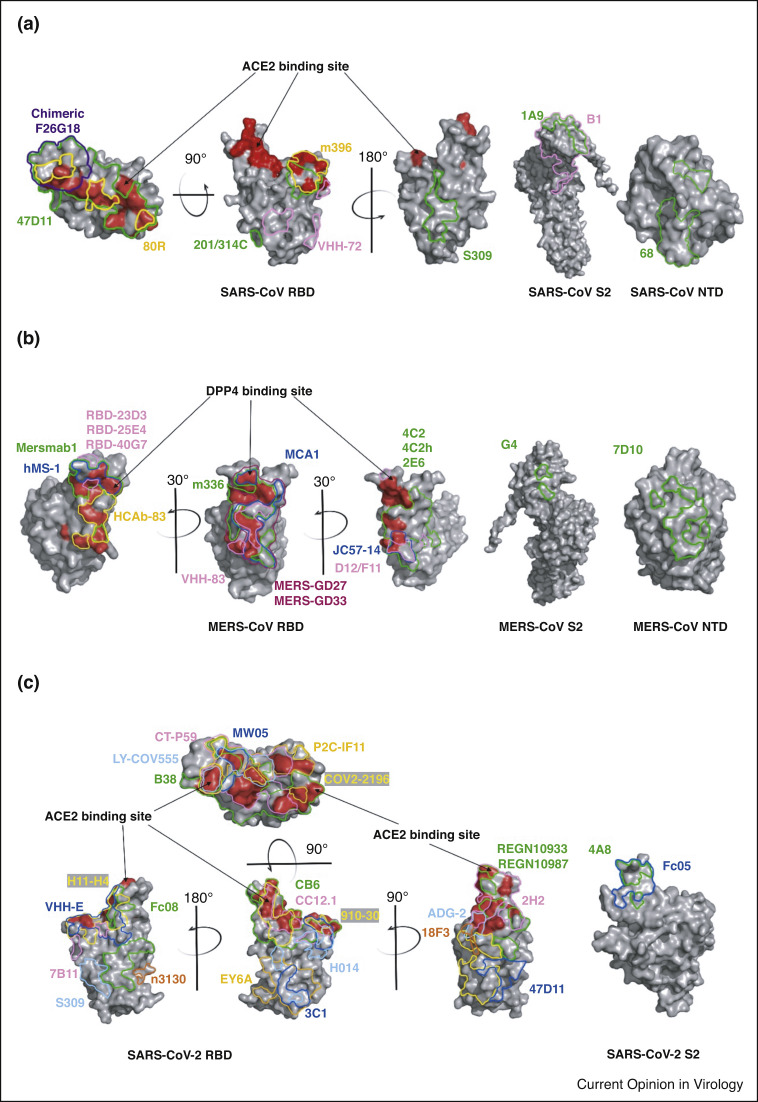

Figure 2.

Binding interface of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies on SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 S glycoproteins. The binding sites of neutralizing antibodies with S proteins of (a) SARS-CoV, (b) MERS-CoV and (c) SARS-CoV-2 are indicated on the NTD, S2 and ‘up’ RBD. Arrow points to red area, the site where RBD binds to the receptor. Multiple colors were used to represent different antibodies. PDBs of crystal structure were shown as follows: SARS-CoV RBD S2 PDB: 2ajf; SARS-CoV NTD PDB: 5x4s; MERS-CoV RBD S2 PDB: 4kqz; MERS-CoV NTD PDB: 6pxh; SARS-CoV-2 RBD PDB: 6m0j; SARS-CoV-2 NTD PDB: 7l2c.

Table 1.

NMAbs against highly pathogenic coronaviruses

| Name of NMAb | Type | Source | Preparation | Target | Mechanisms of neutralization | Developing stage | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMAbs against SARS-CoV | |||||||

| 80R | scFv | Human | Non-immune phage libraries of human antibodies | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [11,12] |

| CR3014 | scFv | Human | Non-immune phage libraries of human antibodies | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [13,14] |

| CR3022 | scFv | Human | A scFv phage display library generated from cells of a convalescent SARS patient | RBD | Blocking conformational changes of S proteins | Preclinical | [17] |

| m396 | Fab | Human | Antibody library derived from cells of healthy volunteers | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [15,16] |

| B1 | scFv | Human | A scFv phage display library generated from cells of a convalescent SARS patient | S2 | – | Preclinical | [18] |

| S3.1 | IgG | Human | Epstein-Barr virus transformation of human B cells of a convalescent SARS patient | S | – | Preclinical | [19] |

| S230.15 | IgG | Human | Epstein-Barr virus transformation of human B cells of a convalescent SARS patient | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [16] |

| 68 | IgG | Human | Transgenic mice | NTD | – | Preclinical | [21] |

| 201 | IgG | Human | Transgenic mice | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [21] |

| F26G18 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [22, 23, 24] |

| 1A5 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [25] |

| 2C5 | |||||||

| 341C | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [26] |

| S34 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | 548 to 567 of S protein | – | Preclinical | [27] |

| S84 | |||||||

| 1A9 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | S2 | – | Preclinical | [30, 31, 32] |

| NMAbs against MERS-CoV | |||||||

| m336 | Fab | Human | A phage-displayed antibody Fab library generated from B cells of healthy donors | RBD | Competition with DPP4 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [33,34] |

| m337 | |||||||

| m338 | |||||||

| 3B11 | scFv | Human | A non-immune phages-displayed scFv library | RBD | Blocking the binding of DPP4 and RBD | Preclinical | [35] |

| MERS-4 | scFv | Human | A non-immune yeast-displayed scFv library | RBD | Competition with DPP4 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [36] |

| MERS-27 | |||||||

| LCA60 | IgG | Human | Epstein-Barr virus transformation of B cells of a convalescent SARS patient | RBD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to cell receptor DPP4 | Preclinical | [38] |

| MCA1 | Fab | Human | A phage-displayed antibody library from a MERS-CoV survivor | RBD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to cell receptor DPP4 | Preclinical | [37] |

| CDC2-C2 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of memory B cells from a MERS patient | RBD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to cell receptor DPP4 | Preclinical | [41] |

| MERS-GD27 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of memory B cells from convalescent MERS patient | RBD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to cell receptor DPP4 | Preclinical | [42,43] |

| REGN3051 | IgG | Human | Transgenic mice | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to DPP4 | Preclinical | [39] |

| REGN3048 | |||||||

| 7.7g6 | IgG | chimeric | Transgenic mice | RBD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to cell receptor DPP4 | Preclinical | [40] |

| 1.6f9 | |||||||

| 1.2g5 | |||||||

| 4.6e10 | |||||||

| 1.6c7 | IgG | chimeric | Transgenic mice | S2 | Preventing comformational changes in the S2 subunit | Preclinical | [40] |

| 3.5g6 | |||||||

| Mersmab1 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to DPP4 | Preclinical | [45,47] |

| 4C2 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | RBD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to cell receptor DPP4 | Preclinical | [46] |

| 2E6 | |||||||

| D12 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | RBD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to cell receptor DPP4 | Preclinical | [49] |

| F11 | |||||||

| G2 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | NTD | – | Preclinical | [49] |

| G4 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | S2 | Inhibition of membrane fusion | Preclinical | [49,50] |

| 5F9 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | NTD | Precluding the conformational changes required for membrane fusion | Preclinical | [52] |

| 7D10 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | NTD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to cell receptor DPP4 and precluding the conformational changes required for membrane fusion | Preclinical | [51] |

| RBD-23D3 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to DPP4 | Preclinical | [48] |

| RBD-25E4 | |||||||

| RBD-40G7 | |||||||

| JC57-14 | IgG | Macaques | Animal immunization and gene cloning | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to DPP4 | Preclinical | [41] |

| JC57-13 | IgG | Macaques | Animal immunization and gene cloning | Non-RBD regions of S1 | – | Preclinical | [41] |

| FIB-H1 | |||||||

| VHH-83 | HCAbs | Camel | VHH complementary DNA library | RBD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to cell receptor DPP4 | Preclinical | [61] |

| NbMS10 | HCAbs | Llama | A VHH phage display library | RBD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to cell receptor DPP4 | Preclinical | [62] |

| VHH-55 | HCAbs | Llama | A VHH phage display library | RBD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to cell receptor DPP4 | Preclinical | [63•] |

| NMAbs against SARS-CoV-2 | |||||||

| ab1 | scFv | Human | Non-immune phage libraries of human antibodies | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [64•] |

| rRBD-15 | Fab | Human | A synthetic human Fab antibody library AB1 | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [65] |

| n3130 | HCAbs | Human | A fully human phage displayed single-domain antibody library of healthy adult donors | S1 | Non-competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [67••] |

| 5A6 | Fab | Human | A highly diverse naïve human Fab library | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [66] |

| CT-P59 | IgG | Human | A scFv phage display library generated from cells of a convalescent SARS patient | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Clinical | [68•] |

| 910-30 | Fab | Human | A yeast-displayed Fab library generated from cells of a COVID-19 convalescent patient | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [70] |

| 2B11 | IgG | Human | Phage-display immune libraries constructed from the pooled PBMCs of COVID-19 convalescent patients | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [69] |

| 1E10 | |||||||

| ADI-55689 | IgG | Human | A yeast-displayed library generated from cells of SARS-infected patients | RBD | Blocking receptor attachment and inducing S1 shedding | Preclinical | [71•] |

| ADI-55993 | |||||||

| ADI-56000 ADI-55688 | |||||||

| ADI-56046 | |||||||

| ADI-56010 ADI-55690 ADI-55951 | |||||||

| ADG-2 | IgG | Human | Engineered antibody | RBD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [72] |

| S309 | IgG | Human | Epstein-Barr virus transformation of human B cells of SARS-infected patients | RBD | S trimer cross-linking, steric hindrance or aggregation of virions | Preclinical | [73•] |

| BD-368-2 | IgG | Human | High-throughput single-cell RNA and VDJ sequencing of convalescent COVID-19 patients’ B cells | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [74] |

| CB6 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells from a COVID-19 convalescent patient | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [79] |

| B38 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells from a COVID-19 convalescent patient | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [86••] |

| H4 | |||||||

| COV2-2196 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells from COVID-19 patients | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [87,88] |

| COV2-2130 | |||||||

| REGN10933 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells from transgenic mice and SARS-CoV-2-infected patients | RBD | blocking the binding of ACE2 to the RBD | Clinical | [90,92,93••] |

| REGN10987 | |||||||

| P2C-1F11 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells from a COVID-19 patient | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [82] |

| P2B-2F6 | |||||||

| CC12.1 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells from COVID-19 patients | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [75] |

| COVA1-18 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells fromCOVID-19 patients | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [94,100] |

| COVA2-15 | |||||||

| COVA1-16 | |||||||

| COVA2-02 | |||||||

| S2E12 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells from COVID-19 patients | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [89] |

| S2M11 | |||||||

| CV07-209 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells from of COVID-19 patients | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [83] |

| C1A-B12 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells from of COVID-19 patients | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [80] |

| A19-46.1 | IgG | Human | B cell sorting of COVID-19 patients and V(D)J sequencing | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [101] |

| A19-61.1 | |||||||

| A23-58.1 | |||||||

| B1-182.1 | |||||||

| DH1047 | IgG | Human | B cell sorting of SARS patients and V(D)J sequencing | RBD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [102,104] |

| CV2-75 | IgG | Human | B cell sorting of COVID-19 patients and V(D)J sequencing | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [103] |

| CV1-30 | |||||||

| 2-15 | IgG | Human | single-cell 5′-mRNA and V(D)J sequencing of COVID-19 patients’ B cells | RBD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to cell receptor ACE2 | Preclinical | [78••] |

| 2-17 | IgG | Human | single-cell 5′-mRNA and V(D)J sequencing of COVID-19 patients’ B cells | NTD | – | Preclinical | [78••] |

| 5-24 | |||||||

| 4-8 | |||||||

| 4A8 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells from of COVID-19 patients | NTD | Altering the conformation of S protein | Preclinical | [76•] |

| MW05 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells from a COVID-19 convalescent patient | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [95] |

| MW07 | |||||||

| 311mab-31B5 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells from a COVID-19 convalescent patient | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [96] |

| 311mab-32D4 | |||||||

| C121 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells fromof COVID-19 patients | RBD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to cell receptor ACE2 | Preclinical | [97] |

| C144 | |||||||

| C135 | |||||||

| CV30 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells from a COVID-19 patient | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [98,99•] |

| EY6A | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells froma COVID-19 convalescent patient | RBD | Altering the pre-fusion conformation of S protein | Preclinical | [106] |

| LY-CoV555 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells from a COVID-19 patient | RBD | Interfering with the binding of RBD to cell receptor ACE2 | Clinical | [84••,85] |

| S2X259 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells from a COVID-19 patient | RBD | Blocked binding of the RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [105] |

| S2H13 | IgG | Human | Antibody gene cloning of B cells of COVID-19 patients | RBD | Blocking the binding of ACE2 and RBD | Preclinical | [81] |

| S2H14 | |||||||

| 2H2 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [107] |

| 3C1 | |||||||

| 7B11 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | RBD | Blocking the binding of RBD to ACE2 | Preclinical | [109•] |

| 18F3 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | RBD | Non-competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [109•] |

| 7D6 | IgG | Mouse | Animal immunization and hybridoma technology | RBD | Non-competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [108] |

| 6D6 | |||||||

| H014 | IgG | humanized | A phage-display scFv library generated from mice immunized with SARS-CoV RBD | RBD | Blocking the binding of ACE2 and RBD through steric hindrance | Preclinical | [110] |

| 47D11 | IgG | chimeric | Transgenic mice | RBD | – | Preclinical | [111•] |

| VHH-72 | HCAbs | llama | A phage display library generated from cells of immune camels | RBD | Blocking the binding of ACE2 and RBD through steric hindrance | Preclinical | [63•] |

| 3F11 | HCAbs | camel | A phage display library generated from cells of nonimmune camels | RBD | blocking the binding of ACE2 to the RBD | Preclinical | [112] |

| H11 | HCAbs | camel | A naive llama phage display antibody library | RBD | blocking the binding of ACE2 to the RBD | Preclinical | [113] |

| NIH-CoVnb-112 | HCAbs | llama | A phage display library generated from cells of immunized llama | RBD | Blocking the binding of ACE2 and RBD | Preclinical | [114] |

| W25 | HCAbs | alpaca | A VHH E. coli displayed antibody library | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [115] |

| Ty1 | HCAbs | alpaca | A phage display library generated from cells of alpaca | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [117] |

| VHH E | HCAbs | camel | A phage display library generated from cells of camel | RBD | Competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD | Preclinical | [116••] |

NMAbs identified by use of Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) transformation technology

Similar to the use of hybridoma technology, researchers used EBV to infect antibody-secreting B cells in order to construct immortal cell lines that stably express antibodies. In this way, a pool of human NMAbs was screened out, such as S3.1 and S230.15 [16,19] (Table 1).

NMAbs identified from transgenic mice

Fully humanized NMAbs have been developed from the human immunoglobulin G (IgG) transgenic mouse, XenoMouse®, immunized with the SARS-CoV S protein [20]. The NMAbs 68 and 201 targeting the NTD and RBD, respectively, identified from the immunized transgenic mice. Mice receiving 40 mg/kg of either NMAb before SARS-CoV challenge were completely protected [21] (Table 1).

NMAbs against SARS-CoV from other sources

NMAbs identified by use of hybridoma technology

Owing to limited human trials, the development of animal immunization and hybridoma technology has substantially enriched SARS-CoV antibody research. A large number of animal-derived NMAbs were screened out, such as F26G18, and the corresponding chimeric antibodies were obtained by antibody humanization. These chimeric NMAbs were shown to target RBD and exert antiviral effects by inhibiting ACE2 binding to RBD [22, 23, 24]. Similarly, many NMAbs with strong neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV were identified, including 1A5, 2C5, and 341C, all targeting RBD [25,26]. To explore effective targets, researchers immunized mice with different regions of the S protein as antigens and obtained S34 and S84 with correspondingly different targets [27]. The mutation of the S2 region was much slower, compared to S1, resulting in the development of more broad-spectrum S2-targeting antibodies against SARS-CoV mutant strains [28,29]. Accordingly, researchers immunized mice with S2 as the antigen and screened a number of NMAbs targeting S2, among which 1A9 was the most potent [30, 31, 32].

NMAbs against MERS-CoV

Human NMAbs against MERS-CoV

NMAbs identified by screening of antibody libraries

NMAbs m336, m337, and m338 that were identified from a phage-displayed Fab library from healthy donors showed potent antiviral activity against MERS-CoV pseudovirus [33,34]. The 3B11 was screened from a nonimmune phage-displayed single chain fragment variable (scFv) library [35]. In addition, MERS-4 and MERS-27 were identified from a yeast-displayed scFv library from healthy donors [36]. These antibodies all targeted the RBD and inhibited viral invasion by blocking the binding between RBD and DPP4 (Figure 2b). Originating from MERS-CoV-infected patients, MCA1 is an RBD-targeting NMAb screened from a phage display library [37].

NMAbs identified by use of EBV transformation technology

In addition to constructing phage libraries, immortalized B cell-based EBV infection has also been performed in antibody studies. For MERS-CoV, LCA60 was screened in this way [38].

NMAbs identified from transgenic mice

REGN3051 and REGN3048 are fully humanized NMAbs screened from transgenic mice [39] (Table 1). A group of chimeric antibodies were also screened from transgenic mice [40]. Among them, 7.7g6, 1.6f9, 1.2g5 and 4.6e10 target RBD, while 1.6c7 and 3.5g6 target S2 to prevent viral invasion by inhibiting the conformational change of S2 [40] (Table 1).

NMAbs identified by use of gene cloning technology

Many NMAbs, such as CDC2-C2 [41] and MERS-GD27 [42,43], have also been obtained using a fast and efficient method known as cloning and expressing antibody genes [44].

NMAbs against MERS-CoV from other sources

NMAbs identified by use of hybridoma technology

A large number of mouse-derived antibodies have been screened. Among of them, Mersmab1 [45], 4C2 and 2E6 were screened for targeting RBD and subsequently produced humanized antibodies that showed potent antiviral activity in vitro and in vivo [46,47]. RBD-23D3, RBD-25E4, and RBD-40G7, all targeting RBD, were identified with high cross-neutralizing activity among mutant isolates [48]. NMAbs D12 and F11 targeting RBD, G2 targeting NTD, and G4 targeting S2 subunit were all identified by immunized mice [49,50]. Screened by hybridoma technology, 5F9 and 7D10 are murine NMAbs targeting the NTD [51,52] (Table 1). In addition to murine-derived antibodies, researchers have obtained neutralizing antibodies from immunized animals of other species. For example, JC57-14, targeting RBD, JC57-14 and FIB-H1, targeting non-RBD regions of S1, were screened from macaques [41]. Furthermore, JC57-14 could protect DPP4-transgenic mice against MERS-CoV infection [41].

Single domain antibodies (sdAbs) identified by screening of antibody libraries

In addition to conventional antibodies, heavy-chain-only antibodies (HCAbs) produced by camelids contain a single-variable domain (VHH), instead of two variable regions on the heavy and light chains, respectively, of conventional IgG antibodies that affords the equivalent effect [53]. VHH shows affinities and specificities for antigens comparable to conventional antibodies. VHHs can be easily constructed into multivalent formats and show higher thermo-stability and chemo-stability, compared to most other antibodies [54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59]. VHHs are also less susceptible to steric hindrance during binding [60]. For MERS-CoV, VHH-83, NbMS10 and VHH-55 were screened from antibody libraries of immunized camels [61,62,63•] (Table 1).

NMAbs against SARS-CoV-2

Human NMAbs against SARS-CoV-2

NMAbs identified by screening of antibody libraries

Ab1, rRBD-15 and 5A6 were screened from nonimmune antibody libraries of healthy humans and showed strong neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro or in vivo [64•,65,66]. In addition, to solve the immunogenicity problem of heterologous single-domain antibodies, researchers constructed a fully human single-domain antibody phage-displayed library by modifying healthy human heavy chains to obtain soluble and highly stable single-domain antibodies [67••], and a pool of NMAbs against SARS-CoV-2 was identified. Among of them, n3130 had the most potency in targeting SARS-CoV-2 S1 [67••]. However, it did not effectively inhibit the binding of RBD to receptor ACE2.

CT-P59, screened from a patient antibody library [68•], showed good therapeutic efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro and in vivo and was used in clinical trials. Similarly, 910-30 and 2B11 were identified from convalescent patient-derived yeast and phage display libraries, respectively [69,70]. Notably, a number of cross-reactive NMAbs (like ADI-55689) against SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 were identified from yeast-displayed libraries established with B cells of SARS convalescent patients based on the genome similarity between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 [71•]. Through genetic mutations, diversity was introduced into the heavy and light chain variable genes of ADI-55688, ADI55689 and ADI-56046, and three highly active antibodies were identified, among which, ADG-2 showed broad-spectrum neutralizing activity against clade 1 sarbecoviruses [72].

NMAbs identified from EBV transformed memory B cells of a recovered SARS patient

S309 was identified from EBV-transformed memory B cells of a recovered patients who was infected by SARS-CoV in 2003 and showed strong cross-neutralizing activity against both SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 [73•].

NMAbs screened by gene cloning and sequencing techniques

Antibody gene cloning and sequencing technologies for identification of SARS-CoV-2 NMAbs from B cells sorted from COVID-19 patients are being used more frequently, and several high-throughput screening methods have been established [74,75], considerably reducing the time required for antibody development and enriching antibody diversity. These NMAbs showed strong neutralizing activity in vitro or in vivo. Most of them target the RBD in S1 subunit, and their mechanism of action is summarized in Table 1. Also, NMAbs targeting SARS-CoV-2 NTD, for example, 4A8 and 4–8, were isolated in this way [76•,77,78••]. A large group of RBD-targeting NMAbs, including BD-368-2, P2C-1F11, CB6, S2H13 and C1A-B12, could interfere with the binding of RBD to the receptor ACE2, showing strong neutralizing activity in vitro [74,79, 80, 81, 82]. CB6 showed potent in vivo efficacy, protecting rhesus macaques against SARS-CoV-2 infection in both prophylactic and treatment settings [79]. CC12.1 exhibited the most potent in vitro neutralizing activity and completely protected Syrian hamsters against the challenge of a Washington strain (USA-WA1/2020) in vivo [75]. CV07-209 could reduce lung pathology in a COVID-19 hamster model [83]. LY-CoV555 protected against SARS-CoV-2 infection in nonhuman primates and showed potent neutralization effect and good safety profiles in clinical trials [84••,85] (Table 1). Notably, B38 and H4 target different neutralizing epitopes in RBD [86••]. No competition takes place between the two NMAbs; therefore, the combination results in an ideal cocktail candidate for COVID-19 therapy, which is also effective in preventing escape mutations. Such antibody pairs are not uncommon in SARS-CoV-2 antibody studies, and their combination has shown better neutralizing activity compared to the use of each compound alone. Examples are COV2-2196/COV2-2130 [87,88], S2M11/S2E12 [89] and REGN10933/REGN10987 (REGN-CoV2) [90,91••,92] (Figure 2c). Further, REGN-CoV2 has shown neutralization effect and safety in clinical trials [93••] (Table 1). Similarly, researchers screened a large set of NMAbs with different targets against SARS-CoV-2 [94]. Among them, COVA1-18 and COVA2-15 showed the strongest antiviral activity [94]. Many NMAbs, such as MW05 [95], 311mab-31B5/311mab-32D4 [96], C121 [97] and CV30 [98,99•] were identified from the sorted SARS-CoV-2 RBD-specific, IgG class-switched memory B cell of COVID-19 convalescent patients using antibody gene cloning technology. They have shown neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro and in vivo through competition with ACE2 in binding with RBD (Table 1). It was found that epitopes of some NMAbs are relatively conservative in sequence (e.g. DH1047, A19-46.1, S2X259 and CV1-30), and these NMAbs show cross-neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants and other sarbecoviruses [100,111•,102, 103, 104, 105]. Like these NMAbs, EY6A targets a conserved footprint in RBD that is distinct from receptor binding motifs, and it inhibits viral invasion by altering the pre-fusion conformation of S proteins [106]. Moreover, it showed cross-reactivity against SARS-CoV S1 protein [106].

NMAbs against SARS-CoV-2 from other sources

NMAbs identified by use of hybridoma technology

2H2 and 3C1 were identified by using animal immunization and hybridoma technology. Because the two NMAbs target different epitopes in SARS-CoV-2 RBD, they can be used in combination, that is, a cocktail therapy (Figure 2c). Their combination exhibited more potent neutralizing activity against authentic SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro [107]. Similarly, 7D6 and 6D6 were identified from mice immunized with SARS-CoV-2 S protein, and SARS-CoV-2/SARS-CoV S protein/MERS-CoV RBD, respectively, showing cross-neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 as well as its variants [108]. 7B11 and 18F3, SARS-CoV neutralizing mAbs by targeting different neutralizing epitopes in RBD of SARS-CoV S protein, were identified from mice immunized with SARS-CoV S-RBD [109•].

NMAbs identified by screening of antibody libraries

H014, a humanized SARS-CoV-2 NMAb, was originally identified from a phage display antibody library generated from RNAs of the peripheral lymphocytes of SARS-CoV RBD-immunized mice. It exhibited potent neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro by blocking RBD-ACE2 binding through steric hindrance [110].

NMAbs identified from transgenic mice

47D11, a chimeric antibody with human variable region and rat constant region, was identified from transgenic mice, showing cross-neutralizing reactivity against SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 [111•].

SdAbs identified by screening of antibody libraries

3F11 was identified from a phage display library from nonimmune camel and was expressed by fusion with human IgG Fc fragment in order to overcome the limitations of sdAbs [58,112]. H11 was also identified from a naive llama phage display antibody library. Researchers obtained H11-H4 and H11-D4 with more affinity for SARS-CoV-2 RBD by random mutation of H11, both exhibiting strong antiviral activity in vitro [113].

More commonly, camels are immunized to obtain sdAbs. VHH-72, was identified from a phage display library of a llama immunized with SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV S proteins multiple times showed cross-neutralizing activity against pseudotyped SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 [63•]. NIH-CoVnb-112 was isolated from an immune llama phage display library [114]. W25 was identified from a VHH Escherichia coli (E. coli) — displayed antibody library of immune alpaca. It showed potent neutralizing activity against the D614G isolate, whether monomer or dimer [115]. Another sdAb that exhibited strong neutralizing activity in multimeric form is VHH E (Figure 2c), which was screened from an immune camel phage display library [116••]. The trimeric VHH EEE inhibits both SARS-CoV-2 pseudovirus and authentic virus infection. The combination of VHH E and VHH V, targeting different sites of the RBD, is effective in preventing escape mutations, whereas multimers could not [116••]. In a similar method, Ty1 was screened from an alpaca phage display library [117]. In addition, a large number of nanobodies have been screened as candidate drugs for the treatment of COVID-19 [118, 119, 120].

Conclusion and prospects

Coronaviruses constitute a large group in nature, and genome sequence analysis shows that many coronaviruses are highly homologous to SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV or SARS-CoV-2 [121]. Therefore, coronaviruses may continue to threaten human health. Rapid development of therapeutic and prophylactic drugs is essential, both for coronaviruses that have already emerged to infect humans and for those that may emerge in the future. With the development of high-throughput screening technology for antibodies, the cycle time for antibody development is shortening. Antibody drugs could be the antiviral drug of choice based on their advantages of high targeting and low side effects. Moreover, different species of coronaviruses have conserved loci between their genomes, and it may be possible to design and screen antibodies with broad-spectrum antiviral activity based on these loci. Many studies on the mechanism of NMAbs with cross-neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV-2 variants and other sarbecoviruses have shown that the targets of these NMAbs are relatively conservative [85,100, 101, 102, 103,105]. In a recent study, 41 RBD-directed NMAbs were classified into seven antibody communities with distinct footprints and competition profiles [122]. A number of NMAb cocktails consist of NNAbs from different RBD-directed antibody communities showed enhanced neutralizing potency. However, the potency of some NNAbs in the combinations is compromised by emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Improving the neutralizing activity of these NMAbs through other means (e.g. mutation and multimeric forms) greatly enhance their application prospects [72,122]. Therefore, in addition to the combination strategy, the in vitro modification of antibodies is also crucial to improve the neutralizing activity of the antibody drugs. Of course, the acceleration of antibody drug formation, the miniaturization of effective antibody molecules and the improvement of in vivo longevity are expected.

Conflict of interest statement

Nothing declared.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81974302 to FY, 82041025 to SJ), the Program for ‘333 Talents Project’ of Hebei Province (A202002003), the Natural Science Foundation of Hebei Province (H2021204001) and the Science and Technology Project of Hebei Education Department (QN2021071).

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., Zhao X., Huang B., Shi W., Lu R., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2••.Wang P., Nair M.S., Liu L., Iketani S., Luo Y., Guo Y., Wang M., Yu J., Zhang B., Kwong P.D., et al. Antibody resistance of SARS-CoV-2 variants B.1.351 and B.1.1.7. Nature. 2021;593:130–135. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; For SARS-CoV-2 Variants B.1.351 and B.1.1.7, this study evaluated the neutralizing activity of multiple antibodies and the neutralizing activity of vaccine-generated antibodies. It is a study of the safety of the vaccine and the effectiveness of the antibody formulation.

- 3.Belouzard S., Chu V.C., Whittaker G.R. Activation of the SARS coronavirus spike protein via sequential proteolytic cleavage at two distinct sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5871–5876. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809524106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burkard C., Verheije M.H., Wicht O., van Kasteren S.I., van Kuppeveld F.J., Haagmans B.L., Pelkmans L., Rottier P.J., Bosch B.J., de Haan C.A. Coronavirus cell entry occurs through the endo-/lysosomal pathway in a proteolysis-dependent manner. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Millet J.K., Whittaker G.R. Host cell entry of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus after two-step, furin-mediated activation of the spike protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:15214–15219. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407087111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park J.E., Li K., Barlan A., Fehr A.R., Perlman S., McCray P.B., Jr., Gallagher T. Proteolytic processing of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spikes expands virus tropism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:12262–12267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1608147113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7••.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T.S., Herrler G., Wu N.H., Nitsche A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181:271–27280.e278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this paper, investigators investigated the entry mechanism of SARS-CoV-2 and showed that ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are essential for the invasion of the virus.

- 8.Walls A.C., Xiong X., Park Y.J., Tortorici M.A., Snijder J., Quispe J., Cameroni E., Gopal R., Dai M., Lanzavecchia A., et al. Unexpected receptor functional mimicry elucidates activation of coronavirus fusion. Cell. 2019;176:1026–1039.e1015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9••.Xia S., Zhu Y., Liu M., Lan Q., Xu W., Wu Y., Ying T., Liu S., Shi Z., Jiang S., et al. Fusion mechanism of 2019-nCoV and fusion inhibitors targeting HR1 domain in spike protein. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:765–767. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0374-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this paper, researchers found that parts of the virus itself can effectively inhibit the invasion of the virus, a new anti-antiviral strategy.

- 10.Yu F., Xiang R., Deng X., Wang L., Yu Z., Tian S., Liang R., Li Y., Ying T., Jiang S. Receptor-binding domain-specific human neutralizing monoclonal antibodies against SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:212. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00318-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sui J., Li W., Murakami A., Tamin A., Matthews L.J., Wong S.K., Moore M.J., Tallarico A.S., Olurinde M., Choe H., et al. Potent neutralization of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus by a human mAb to S1 protein that blocks receptor association. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2536–2541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307140101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sui J., Li W., Roberts A., Matthews L.J., Murakami A., Vogel L., Wong S.K., Subbarao K., Farzan M., Marasco W.A. Evaluation of human monoclonal antibody 80R for immunoprophylaxis of severe acute respiratory syndrome by an animal study, epitope mapping, and analysis of spike variants. J Virol. 2005;79:5900–5906. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.10.5900-5906.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van den Brink E.N., Ter Meulen J., Cox F., Jongeneelen M.A., Thijsse A., Throsby M., Marissen W.E., Rood P.M., Bakker A.B., Gelderblom H.R., et al. Molecular and biological characterization of human monoclonal antibodies binding to the spike and nucleocapsid proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2005;79:1635–1644. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1635-1644.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ter Meulen J., Bakker A.B., van den Brink E.N., Weverling G.J., Martina B.E., Haagmans B.L., Kuiken T., de Kruif J., Preiser W., Spaan W., et al. Human monoclonal antibody as prophylaxis for SARS coronavirus infection in ferrets. Lancet. 2004;363:2139–2141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16506-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prabakaran P., Gan J., Feng Y., Zhu Z., Choudhry V., Xiao X., Ji X., Dimitrov D.S. Structure of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus receptor-binding domain complexed with neutralizing antibody. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:15829–15836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600697200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu Z., Chakraborti S., He Y., Roberts A., Sheahan T., Xiao X., Hensley L.E., Prabakaran P., Rockx B., Sidorov I.A., et al. Potent cross-reactive neutralization of SARS coronavirus isolates by human monoclonal antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:12123–12128. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701000104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ter Meulen J., van den Brink E.N., Poon L.L., Marissen W.E., Leung C.S., Cox F., Cheung C.Y., Bakker A.Q., Bogaards J.A., van Deventer E., et al. Human monoclonal antibody combination against SARS coronavirus: synergy and coverage of escape mutants. PLoS Med. 2006;3 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duan J., Yan X., Guo X., Cao W., Han W., Qi C., Feng J., Yang D., Gao G., Jin G. A human SARS-CoV neutralizing antibody against epitope on S2 protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Traggiai E., Becker S., Subbarao K., Kolesnikova L., Uematsu Y., Gismondo M.R., Murphy B.R., Rappuoli R., Lanzavecchia A. An efficient method to make human monoclonal antibodies from memory B cells: potent neutralization of SARS coronavirus. Nat Med. 2004;10:871–875. doi: 10.1038/nm1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coughlin M., Lou G., Martinez O., Masterman S.K., Olsen O.A., Moksa A.A., Farzan M., Babcook J.S., Prabhakar B.S. Generation and characterization of human monoclonal neutralizing antibodies with distinct binding and sequence features against SARS coronavirus using XenoMouse. Virology. 2007;361:93–102. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenough T.C., Babcock G.J., Roberts A., Hernandez H.J., Thomas W.D., Jr., Coccia J.A., Graziano R.F., Srinivasan M., Lowy I., Finberg R.W., et al. Development and characterization of a severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus-neutralizing human monoclonal antibody that provides effective immunoprophylaxis in mice. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:507–514. doi: 10.1086/427242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krokhin O., Li Y., Andonov A., Feldmann H., Flick R., Jones S., Stroeher U., Bastien N., Dasuri K.V., Cheng K., et al. Mass spectrometric characterization of proteins from the SARS virus: a preliminary report. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2003;2:346–356. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M300048-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berry J.D., Jones S., Drebot M.A., Andonov A., Sabara M., Yuan X.Y., Weingartl H., Fernando L., Marszal P., Gren J., et al. Development and characterisation of neutralising monoclonal antibody to the SARS-coronavirus. J Virol Methods. 2004;120:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berry J.D., Hay K., Rini J.M., Yu M., Wang L., Plummer F.A., Corbett C.R., Andonov A. Neutralizing epitopes of the SARS-CoV S-protein cluster independent of repertoire, antigen structure or mAb technology. mAbs. 2010;2:53–66. doi: 10.4161/mabs.2.1.10788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chou T.H., Wang S., Sakhatskyy P.V., Mboudjeka I., Lawrence J.M., Huang S., Coley S., Yang B., Li J., Zhu Q., et al. Epitope mapping and biological function analysis of antibodies produced by immunization of mice with an inactivated Chinese isolate of severe acute respiratory syndrome-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) Virology. 2005;334:134–143. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tripp R.A., Haynes L.M., Moore D., Anderson B., Tamin A., Harcourt B.H., Jones L.P., Yilla M., Babcock G.J., Greenough T., et al. Monoclonal antibodies to SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV): identification of neutralizing and antibodies reactive to S, N, M and E viral proteins. J Virol Methods. 2005;128:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou T., Wang H., Luo D., Rowe T., Wang Z., Hogan R.J., Qiu S., Bunzel R.J., Huang G., Mishra V., et al. An exposed domain in the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein induces neutralizing antibodies. J Virol. 2004;78:7217–7226. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.13.7217-7226.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coughlin M.M., Prabhakar B.S. Neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus: target, mechanism of action, and therapeutic potential. Rev Med Virol. 2012;22:2–17. doi: 10.1002/rmv.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elshabrawy H.A., Coughlin M.M., Baker S.C., Prabhakar B.S. Human monoclonal antibodies against highly conserved HR1 and HR2 domains of the SARS-CoV spike protein are more broadly neutralizing. PLoS One. 2012;7 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keng C.T., Zhang A., Shen S., Lip K.M., Fielding B.C., Tan T.H., Chou C.F., Loh C.B., Wang S., Fu J., et al. Amino acids 1055 to 1192 in the S2 region of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus S protein induce neutralizing antibodies: implications for the development of vaccines and antiviral agents. J Virol. 2005;79:3289–3296. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.6.3289-3296.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lip K.M., Shen S., Yang X., Keng C.T., Zhang A., Oh H.L., Li Z.H., Hwang L.A., Chou C.F., Fielding B.C., et al. Monoclonal antibodies targeting the HR2 domain and the region immediately upstream of the HR2 of the S protein neutralize in vitro infection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Virol. 2006;80:941–950. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.941-950.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng O.W., Keng C.T., Leung C.S., Peiris J.S., Poon L.L., Tan Y.J. Substitution at aspartic acid 1128 in the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein mediates escape from a S2 domain-targeting neutralizing monoclonal antibody. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0102415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ying T., Prabakaran P., Du L., Shi W., Feng Y., Wang Y., Wang L., Li W., Jiang S., Dimitrov D.S., et al. Junctional and allele-specific residues are critical for MERS-CoV neutralization by an exceptionally potent germline-like antibody. Nat Commun. 2015;6 doi: 10.1038/ncomms9223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ying T., Du L., Ju T.W., Prabakaran P., Lau C.C., Lu L., Liu Q., Wang L., Feng Y., Wang Y., et al. Exceptionally potent neutralization of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus by human monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 2014;88:7796–7805. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00912-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tang X.C., Agnihothram S.S., Jiao Y., Stanhope J., Graham R.L., Peterson E.C., Avnir Y., Tallarico A.S., Sheehan J., Zhu Q., et al. Identification of human neutralizing antibodies against MERS-CoV and their role in virus adaptive evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E2018–E2026. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402074111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jiang L., Wang N., Zuo T., Shi X., Poon K.M., Wu Y., Gao F., Li D., Wang R., Guo J., et al. Potent neutralization of MERS-CoV by human neutralizing monoclonal antibodies to the viral spike glycoprotein. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen Z., Bao L., Chen C., Zou T., Xue Y., Li F., Lv Q., Gu S., Gao X., Cui S., et al. Human neutralizing monoclonal antibody inhibition of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication in the common marmoset. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:1807–1815. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Corti D., Zhao J., Pedotti M., Simonelli L., Agnihothram S., Fett C., Fernandez-Rodriguez B., Foglierini M., Agatic G., Vanzetta F., et al. Prophylactic and postexposure efficacy of a potent human monoclonal antibody against MERS coronavirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:10473–10478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510199112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pascal K.E., Coleman C.M., Mujica A.O., Kamat V., Badithe A., Fairhurst J., Hunt C., Strein J., Berrebi A., Sisk J.M., et al. Pre- and postexposure efficacy of fully human antibodies against spike protein in a novel humanized mouse model of MERS-CoV infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:8738–8743. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510830112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Widjaja I., Wang C., van Haperen R., Gutiérrez-Álvarez J., van Dieren B., Okba N.M.A., Raj V.S., Li W., Fernandez-Delgado R., Grosveld F., et al. Towards a solution to MERS: protective human monoclonal antibodies targeting different domains and functions of the MERS-coronavirus spike glycoprotein. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2019;8:516–530. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2019.1597644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang L., Shi W., Chappell J.D., Joyce M.G., Zhang Y., Kanekiyo M., Becker M.M., van Doremalen N., Fischer R., Wang N., et al. Importance of neutralizing monoclonal antibodies targeting multiple antigenic sites on the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike glycoprotein to avoid neutralization escape. J Virol. 2018;92:e02002–e02017. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02002-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Niu P., Zhang S., Zhou P., Huang B., Deng Y., Qin K., Wang P., Wang W., Wang X., Zhou J., et al. Ultrapotent human neutralizing antibody repertoires against Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus from a recovered patient. J Infect Dis. 2018;218:1249–1260. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiy311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Niu P., Zhao G., Deng Y., Sun S., Wang W., Zhou Y., Tan W. A novel human mAb (MERS-GD27) provides prophylactic and postexposure efficacy in MERS-CoV susceptible mice. Sci China Life Sci. 2018;61:1280–1282. doi: 10.1007/s11427-018-9343-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith K., Garman L., Wrammert J., Zheng N.Y., Capra J.D., Ahmed R., Wilson P.C. Rapid generation of fully human monoclonal antibodies specific to a vaccinating antigen. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:372–384. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Du L., Zhao G., Yang Y., Qiu H., Wang L., Kou Z., Tao X., Yu H., Sun S., Tseng C.T., et al. A conformation-dependent neutralizing monoclonal antibody specifically targeting receptor-binding domain in Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein. J Virol. 2014;88:7045–7053. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00433-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li Y., Wan Y., Liu P., Zhao J., Lu G., Qi J., Wang Q., Lu X., Wu Y., Liu W., et al. A humanized neutralizing antibody against MERS-CoV targeting the receptor-binding domain of the spike protein. Cell Res. 2015;25:1237–1249. doi: 10.1038/cr.2015.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qiu H., Sun S., Xiao H., Feng J., Guo Y., Tai W., Wang Y., Du L., Zhao G., Zhou Y. Single-dose treatment with a humanized neutralizing antibody affords full protection of a human transgenic mouse model from lethal Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS)-coronavirus infection. Antiviral Res. 2016;132:141–148. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goo J., Jeong Y., Park Y.S., Yang E., Jung D.I., Rho S., Park U., Sung H., Park P.G., Choi J.A., et al. Characterization of novel monoclonal antibodies against MERS-coronavirus spike protein. Virus Res. 2020;278 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.197863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang L., Shi W., Joyce M.G., Modjarrad K., Zhang Y., Leung K., Lees C.R., Zhou T., Yassine H.M., Kanekiyo M., et al. Evaluation of candidate vaccine approaches for MERS-CoV. Nat Commun. 2015;6 doi: 10.1038/ncomms8712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pallesen J., Wang N., Corbett K.S., Wrapp D., Kirchdoerfer R.N., Turner H.L., Cottrell C.A., Becker M.M., Wang L., Shi W., et al. Immunogenicity and structures of a rationally designed prefusion MERS-CoV spike antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E7348–E7357. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707304114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou H., Chen Y., Zhang S., Niu P., Qin K., Jia W., Huang B., Zhang S., Lan J., Zhang L., et al. Structural definition of a neutralization epitope on the N-terminal domain of MERS-CoV spike glycoprotein. Nat Commun. 2019;10 doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10897-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen Y., Lu S., Jia H., Deng Y., Zhou J., Huang B., Yu Y., Lan J., Wang W., Lou Y., et al. A novel neutralizing monoclonal antibody targeting the N-terminal domain of the MERS-CoV spike protein. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2017;6 doi: 10.1038/emi.2017.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamers-Casterman C., Atarhouch T., Muyldermans S., Robinson G., Hammers C., Songa E.B., Bendahman N., Hammers R. Naturally occurring antibodies devoid of light chains. Nature. 1993;363:446–448. doi: 10.1038/363446a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.De Vlieger D., Ballegeer M., Rossey I., Schepens B., Saelens X. Single-domain antibodies and their formatting to combat viral infections. Antibodies. 2019;8:1. doi: 10.3390/antib8010001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dumoulin M., Conrath K., Van Meirhaeghe A., Meersman F., Heremans K., Frenken L.G.J., Muyldermans S., Wyns L., Matagne A. Single-domain antibody fragments with high conformational stability. Protein Sci. 2002;11:500–515. doi: 10.1110/ps.34602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Govaert J., Pellis M., Deschacht N., Vincke C., Conrath K., Muyldermans S., Saerens D. Dual beneficial effect of interloop disulfide bond for single domain antibody fragments. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:1970–1979. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.242818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Laursen N.S., Friesen R.H.E., Zhu X., Jongeneelen M., Blokland S., Vermond J., van Eijgen A., Tang C., van Diepen H., Obmolova G., et al. Universal protection against influenza infection by a multidomain antibody to influenza hemagglutinin. Science. 2018;362:598–602. doi: 10.1126/science.aaq0620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rotman M., Welling M.M., van den Boogaard M.L., Moursel L.G., van der Graaf L.M., van Buchem M.A., van der Maarel S.M., van der Weerd L. Fusion of hIgG1-Fc to 111In-anti-amyloid single domain antibody fragment VHH-pa2H prolongs blood residential time in APP/PS1 mice but does not increase brain uptake. Nucl Med Biol. 2015;42:695–702. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.van der Linden R.H., Frenken L.G., de Geus B., Harmsen M.M., Ruuls R.C., Stok W., de Ron L., Wilson S., Davis P., Verrips C.T. Comparison of physical chemical properties of llama VHH antibody fragments and mouse monoclonal antibodies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1431:37–46. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(99)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Forsman A., Beirnaert E., Aasa-Chapman M.M., Hoorelbeke B., Hijazi K., Koh W., Tack V., Szynol A., Kelly C., McKnight A., et al. Llama antibody fragments with cross-subtype human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1)-neutralizing properties and high affinity for HIV-1 gp120. J Virol. 2008;82:12069–12081. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01379-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stalin Raj V., Okba N.M.A., Gutierrez-Alvarez J., Drabek D., van Dieren B., Widagdo W., Lamers M.M., Widjaja I., Fernandez-Delgado R., Sola I., et al. Chimeric camel/human heavy-chain antibodies protect against MERS-CoV infection. Sci Adv. 2018;4 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aas9667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhao G., He L., Sun S., Qiu H., Tai W., Chen J., Li J., Chen Y., Guo Y., Wang Y., et al. A novel nanobody targeting Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) receptor-binding domain has potent cross-neutralizing activity and protective efficacy against MERS-CoV. J Virol. 2018;92 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00837-18. e00837-00818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63•.Wrapp D., De Vlieger D., Corbett K.S., Torres G.M., Wang N., Van Breedam W., Roose K., van Schie L., Hoffmann M., Pöhlmann S., et al. Structural basis for potent neutralization of betacoronaviruses by single-domain camelid antibodies. Cell. 2020;181:1004–1015.e1015. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this paper, single-domain antibodies with cross-activity between SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 were obtained by immunization camel with S protein of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV.

- 64•.Li W., Chen C., Drelich A., Martinez D.R., Gralinski L.E., Sun Z., Schäfer A., Kulkarni S.S., Liu X., Leist S.R., et al. Rapid identification of a human antibody with high prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy in three animal models of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:29832–29838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2010197117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this paper, a germline antibody against SARS-CoV-2 was obtained by screening an antibody library from healthy individuals.

- 65.Zeng X., Li L., Lin J., Li X., Liu B., Kong Y., Zeng S., Du J., Xiao H., Zhang T., et al. Isolation of a human monoclonal antibody specific for the receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 using a competitive phage biopanning strategy. Antibody Ther. 2020;3:95–100. doi: 10.1093/abt/tbaa008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Asarnow D., Wang B., Lee W.H., Hu Y., Huang C.W., Faust B., Ng P.M.L., Ngoh E.Z.X., Bohn M., Bulkley D., et al. Structural insight into SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies and modulation of syncytia. Cell. 2021;184:3192–3204.e3116. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67••.Wu Y., Li C., Xia S., Tian X., Kong Y., Wang Z., Gu C., Zhang R., Tu C., Xie Y., et al. Identification of human single-domain antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;27:891–898.e895. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study, a fully human single-domain antibody library was constructed and a large set of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-2 was screened.

- 68•.Kim C., Ryu D.K., Lee J., Kim Y.I., Seo J.M., Kim Y.G., Jeong J.H., Kim M., Kim J.I., Kim P., et al. A therapeutic neutralizing antibody targeting receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Nat Commun. 2021;12 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20602-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study, a neutralizing antibody targeting RBD was screened in patients, and the antibody has entered clinical trials.

- 69.Pan Y., Du J., Liu J., Wu H., Gui F., Zhang N., Deng X., Song G., Li Y., Lu J., et al. Screening of potent neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 using convalescent patients-derived phage-display libraries. Cell Discov. 2021;7:57. doi: 10.1038/s41421-021-00295-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Banach B.B., Cerutti G., Fahad A.S., Shen C.H., Oliveira De Souza M., Katsamba P.S., Tsybovsky Y., Wang P., Nair M.S., Huang Y., et al. Paired heavy- and light-chain signatures contribute to potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralization in public antibody responses. Cell Rep. 2021;37 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71•.Wec A.Z., Wrapp D., Herbert A.S., Maurer D.P., Haslwanter D., Sakharkar M., Jangra R.K., Dieterle M.E., Lilov A., Huang D., et al. Broad neutralization of SARS-related viruses by human monoclonal antibodies. Science. 2020;369:731–736. doi: 10.1126/science.abc7424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study, a group of antibodies with broad-spectrum activity against SARS-related viruses was screened from patients with SARS-CoV.

- 72.Rappazzo C.G., Tse L.V., Kaku C.I., Wrapp D., Sakharkar M., Huang D., Deveau L.M., Yockachonis T.J., Herbert A.S., Battles M.B., et al. Broad and potent activity against SARS-like viruses by an engineered human monoclonal antibody. Science. 2021;371:823–829. doi: 10.1126/science.abf4830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73•.Pinto D., Park Y.J., Beltramello M., Walls A.C., Tortorici M.A., Bianchi S., Jaconi S., Culap K., Zatta F., De Marco A., et al. Cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by a human monoclonal SARS-CoV antibody. Nature. 2020;583:290–295. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2349-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study, an antibody with cross-activity against SARS-CoV-2 was screened from patients with SARS-CoV.

- 74.Cao Y., Su B., Guo X., Sun W., Deng Y., Bao L., Zhu Q., Zhang X., Zheng Y., Geng C., et al. Potent neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 identified by high-throughput single-cell sequencing of convalescent patients’ B cells. Cell. 2020;182:73–84.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rogers T.F., Zhao F., Huang D., Beutler N., Burns A., He W.T., Limbo O., Smith C., Song G., Woehl J., et al. Isolation of potent SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies and protection from disease in a small animal model. Science. 2020;369:956–963. doi: 10.1126/science.abc7520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76•.Chi X., Yan R., Zhang J., Zhang G., Zhang Y., Hao M., Zhang Z., Fan P., Dong Y., Yang Y., et al. A neutralizing human antibody binds to the N-terminal domain of the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Science. 2020;369:650–655. doi: 10.1126/science.abc6952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study, a neutralizing antibody targeting the S protein NTD was screened.

- 77.McCallum M., De Marco A., Lempp F.A., Tortorici M.A., Pinto D., Walls A.C., Beltramello M., Chen A., Liu Z., Zatta F., et al. N-terminal domain antigenic mapping reveals a site of vulnerability for SARS-CoV-2. Cell. 2021;184:2332–2347.e2316. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78••.Liu L., Wang P., Nair M.S., Yu J., Rapp M., Wang Q., Luo Y., Chan J.F., Sahi V., Figueroa A., et al. Potent neutralizing antibodies against multiple epitopes on SARS-CoV-2 spike. Nature. 2020;584:450–456. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2571-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study, neutralizing antibodies targeting different regions of the S protein were screened.

- 79.Shi R., Shan C., Duan X., Chen Z., Liu P., Song J., Song T., Bi X., Han C., Wu L., et al. A human neutralizing antibody targets the receptor-binding site of SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;584:120–124. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2381-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Clark S.A., Clark L.E., Pan J., Coscia A., McKay L.G.A., Shankar S., Johnson R.I., Brusic V., Choudhary M.C., Regan J., et al. SARS-CoV-2 evolution in an immunocompromised host reveals shared neutralization escape mechanisms. Cell. 2021;184:2605–2617.e2618. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Piccoli L., Park Y.J., Tortorici M.A., Czudnochowski N., Walls A.C., Beltramello M., Silacci-Fregni C., Pinto D., Rosen L.E., Bowen J.E., et al. Mapping neutralizing and immunodominant sites on the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain by structure-guided high-resolution serology. Cell. 2020;183:1024–1042.e1021. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ju B., Zhang Q., Ge J., Wang R., Sun J., Ge X., Yu J., Shan S., Zhou B., Song S., et al. Human neutralizing antibodies elicited by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nature. 2020;584:115–119. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2380-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kreye J., Reincke S.M., Kornau H.C., Sánchez-Sendin E., Corman V.M., Liu H., Yuan M., Wu N.C., Zhu X., Lee C.D., et al. A therapeutic non-self-reactive SARS-CoV-2 antibody protects from lung pathology in a COVID-19 hamster model. Cell. 2020;183:1058–1069.e1019. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84••.Chen P., Nirula A., Heller B., Gottlieb R.L., Boscia J., Morris J., Huhn G., Cardona J., Mocherla B., Stosor V., et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody LY-CoV555 in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:229–237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2029849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Clinical results show that LY-CoV555 shows good therapeutic effects.

- 85.Jones B.E., Brown-Augsburger P.L., Corbett K.S., Westendorf K., Davies J., Cujec T.P., Wiethoff C.M., Blackbourne J.L., Heinz B.A., Foster D., et al. The neutralizing antibody, LY-CoV555, protects against SARS-CoV-2 infection in nonhuman primates. Sci Transl Med. 2021;13 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abf1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86••.Wu Y., Wang F., Shen C., Peng W., Li D., Zhao C., Li Z., Li S., Bi Y., Yang Y., et al. A noncompeting pair of human neutralizing antibodies block COVID-19 virus binding to its receptor ACE2. Science. 2020;368:1274–1278. doi: 10.1126/science.abc2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study, a non-competitive neutralizing antibody pair was developed, which can effectively avoid escape mutations, a good therapeutic strategy.

- 87.Zost S.J., Gilchuk P., Case J.B., Binshtein E., Chen R.E., Nkolola J.P., Schäfer A., Reidy J.X., Trivette A., Nargi R.S., et al. Potently neutralizing and protective human antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020;584:443–449. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2548-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zost S.J., Gilchuk P., Chen R.E., Case J.B., Reidy J.X., Trivette A., Nargi R.S., Sutton R.E., Suryadevara N., Chen E.C., et al. Rapid isolation and profiling of a diverse panel of human monoclonal antibodies targeting the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Nat Med. 2020;26:1422–1427. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0998-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tortorici M.A., Beltramello M., Lempp F.A., Pinto D., Dang H.V., Rosen L.E., McCallum M., Bowen J., Minola A., Jaconi S., et al. Ultrapotent human antibodies protect against SARS-CoV-2 challenge via multiple mechanisms. Science. 2020;370:950–957. doi: 10.1126/science.abe3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hansen J., Baum A., Pascal K.E., Russo V., Giordano S., Wloga E., Fulton B.O., Yan Y., Koon K., Patel K., et al. Studies in humanized mice and convalescent humans yield a SARS-CoV-2 antibody cocktail. Science. 2020;369:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91••.Baum A., Fulton B.O., Wloga E., Copin R., Pascal K.E., Russo V., Giordano S., Lanza K., Negron N., Ni M., et al. Antibody cocktail to SARS-CoV-2 spike protein prevents rapid mutational escape seen with individual antibodies. Science. 2020;369:1014–1018. doi: 10.1126/science.abd0831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This study has developed a neutralizing antibody pair that effectively avoids escape mutations, a good therapeutic strategy. This cocktail is already in clinical trials.

- 92.Baum A., Ajithdoss D., Copin R., Zhou A., Lanza K., Negron N., Ni M., Wei Y., Mohammadi K., Musser B., et al. REGN-COV2 antibodies prevent and treat SARS-CoV-2 infection in rhesus macaques and hamsters. Science. 2020;370:1110–1115. doi: 10.1126/science.abe2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93••.Weinreich D.M., Sivapalasingam S., Norton T., Ali S., Gao H., Bhore R., Musser B.J., Soo Y., Rofail D., Im J., et al. REGN-COV2, a neutralizing antibody cocktail, in outpatients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:238–251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2035002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Clinical results show that cocktail REGN-COV2 demonstrates good therapeutic efficacy.

- 94.Brouwer P.J.M., Caniels T.G., van der Straten K., Snitselaar J.L., Aldon Y., Bangaru S., Torres J.L., Okba N.M.A., Claireaux M., Kerster G., et al. Potent neutralizing antibodies from COVID-19 patients define multiple targets of vulnerability. Science. 2020;369:643–650. doi: 10.1126/science.abc5902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wang S., Peng Y., Wang R., Jiao S., Wang M., Huang W., Shan C., Jiang W., Li Z., Gu C., et al. Characterization of neutralizing antibody with prophylactic and therapeutic efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 in rhesus monkeys. Nat Commun. 2020;11 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19568-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen X., Li R., Pan Z., Qian C., Yang Y., You R., Zhao J., Liu P., Gao L., Li Z., et al. Human monoclonal antibodies block the binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to angiotensin converting enzyme 2 receptor. Cell Mol Immunol. 2020;17:647–649. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-0426-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Robbiani D.F., Gaebler C., Muecksch F., Lorenzi J.C.C., Wang Z., Cho A., Agudelo M., Barnes C.O., Gazumyan A., Finkin S., et al. Convergent antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in convalescent individuals. Nature. 2020;584:437–442. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2456-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Seydoux E., Homad L.J., MacCamy A.J., Parks K.R., Hurlburt N.K., Jennewein M.F., Akins N.R., Stuart A.B., Wan Y.H., Feng J., et al. Analysis of a SARS-CoV-2-infected individual reveals development of potent neutralizing antibodies with limited somatic mutation. Immunity. 2020;53:98–105.e105. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99•.Hurlburt N.K., Seydoux E., Wan Y.H., Edara V.V., Stuart A.B., Feng J., Suthar M.S., McGuire A.T., Stamatatos L., Pancera M. Structural basis for potent neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 and role of antibody affinity maturation. Nat Commun. 2020;11 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19231-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study, mutations in antibody genes were found to be necessary for effective neutralization of SARS-CoV-2.

- 100.Liu H., Wu N.C., Yuan M., Bangaru S., Torres J.L., Caniels T.G., van Schooten J., Zhu X., Lee C.D., Brouwer P.J.M., et al. Cross-neutralization of a SARS-CoV-2 antibody to a functionally conserved site is mediated by avidity. Immunity. 2020;53:1272–1280.e1275. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2020.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Wang L., Zhou T., Zhang Y., Yang E.S., Schramm C.A., Shi W., Pegu A., Oloniniyi O.K., Henry A.R., Darko S., et al. Ultrapotent antibodies against diverse and highly transmissible SARS-CoV-2 variants. Science. 2021;373 doi: 10.1126/science.abh1766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Martinez D.R., Schäfer A., Gobeil S., Li D., De la Cruz G., Parks R., Lu X., Barr M., Stalls V., Janowska K., et al. A broadly cross-reactive antibody neutralizes and protects against sarbecovirus challenge in mice. Sci Transl Med. 2021 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abj7125. eabj7125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Jennewein M.F., MacCamy A.J., Akins N.R., Feng J., Homad L.J., Hurlburt N.K., Seydoux E., Wan Y.H., Stuart A.B., Edara V.V., et al. Isolation and characterization of cross-neutralizing coronavirus antibodies from COVID-19+ subjects. Cell Rep. 2021;36 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Li D., Edwards R.J., Manne K., Martinez D.R., Schäfer A., Alam S.M., Wiehe K., Lu X., Parks R., Sutherland L.L., et al. In vitro and in vivo functions of SARS-CoV-2 infection-enhancing and neutralizing antibodies. Cell. 2021;184:4203–4219.e4232. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tortorici M.A., Czudnochowski N., Starr T.N., Marzi R., Walls A.C., Zatta F., Bowen J.E., Jaconi S., Di Iulio J., Wang Z., et al. Broad sarbecovirus neutralization by a human monoclonal antibody. Nature. 2021;597:103–108. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03817-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhou D., Duyvesteyn H.M.E., Chen C.P., Huang C.G., Chen T.H., Shih S.R., Lin Y.C., Cheng C.Y., Cheng S.H., Huang Y.C., et al. Structural basis for the neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by an antibody from a convalescent patient. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2020;27:950–958. doi: 10.1038/s41594-020-0480-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zhang C., Wang Y., Zhu Y., Liu C., Gu C., Xu S., Wang Y., Zhou Y., Wang Y., Han W., et al. Development and structural basis of a two-MAb cocktail for treating SARS-CoV-2 infections. Nat Commun. 2021;12 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20465-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Li T., Xue W., Zheng Q., Song S., Yang C., Xiong H., Zhang S., Hong M., Zhang Y., Yu H., et al. Cross-neutralizing antibodies bind a SARS-CoV-2 cryptic site and resist circulating variants. Nat Commun. 2021;12 doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-25997-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109•.Tai W., Zhang X., He Y., Jiang S., Du L. Identification of SARS-CoV RBD-targeting monoclonal antibodies with cross-reactive or neutralizing activity against SARS-CoV-2. Antiviral Res. 2020;179 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study, a pair of antibodies with cross-activity against SARS-2 was screened from a murine-derived hybridoma of SARS-CoV.

- 110.Lv Z., Deng Y.Q., Ye Q., Cao L., Sun C.Y., Fan C., Huang W., Sun S., Sun Y., Zhu L., et al. Structural basis for neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 and SARS-CoV by a potent therapeutic antibody. Science. 2020;369:1505–1509. doi: 10.1126/science.abc5881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111•.Wang C., Li W., Drabek D., Okba N.M.A., van Haperen R., Osterhaus A., van Kuppeveld F.J.M., Haagmans B.L., Grosveld F., Bosch B.J. A human monoclonal antibody blocking SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Commun. 2020;11 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16256-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; In this study, an antibody with cross-activity against SARS-CoV-2 was screened from SARS-CoV-immunized transgenic mice.

- 112.Chi X., Liu X., Wang C., Zhang X., Li X., Hou J., Ren L., Jin Q., Wang J., Yang W. Humanized single domain antibodies neutralize SARS-CoV-2 by targeting the spike receptor binding domain. Nat Commun. 2020;11 doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18387-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Huo J., Le Bas A., Ruza R.R., Duyvesteyn H.M.E., Mikolajek H., Malinauskas T., Tan T.K., Rijal P., Dumoux M., Ward P.N., et al. Neutralizing nanobodies bind SARS-CoV-2 spike RBD and block interaction with ACE2. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2020;27:846–854. doi: 10.1038/s41594-020-0469-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Esparza T.J., Martin N.P., Anderson G.P., Goldman E.R., Brody D.L. High affinity nanobodies block SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor binding domain interaction with human angiotensin converting enzyme. Sci Rep. 2020;10:22370. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-79036-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Valenzuela Nieto G., Jara R., Watterson D., Modhiran N., Amarilla A.A., Himelreichs J., Khromykh A.A., Salinas-Rebolledo C., Pinto T., Cheuquemilla Y., et al. Potent neutralization of clinical isolates of SARS-CoV-2 D614 and G614 variants by a monomeric, sub-nanomolar affinity nanobody. Sci Rep. 2021;11:3318. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-82833-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116••.Koenig P.A., Das H., Liu H., Kümmerer B.M., Gohr F.N., Jenster L.M., Schiffelers L.D.J., Tesfamariam Y.M., Uchima M., Wuerth J.D., et al. Structure-guided multivalent nanobodies block SARS-CoV-2 infection and suppress mutational escape. Science. 2021;371 doi: 10.1126/science.abe6230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Studies have shown that nanobody multimers are more effective in neutralizing, but less synergistic than multiple antibodies in avoiding escape mutations.