Abstract

4-Hydroxy-2-pyridone alkaloids have attracted attention for synthetic and biosynthetic studies due to their broad biological activities and structural diversity. Here we elucidated the pathway and chemical logic of (−)-sambutoxin (1) biosynthesis. In particular, we uncovered the enzymatic origin of the tetrahydropyran moiety and showed that the p-hydroxyphenyl group is installed via a late-stage, P450-catalyzed oxidation of the phenylalanine-derived side chain rather than via a direct incorporation of tyrosine.

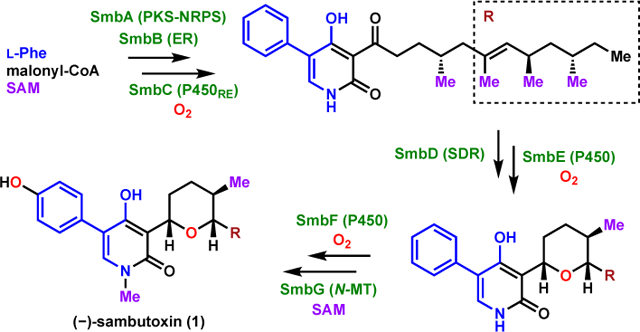

Graphical Abstract

4-Hydroxy-2-pyridone alkaloids are a family of fungal natural products exhibiting an impressive range of biological activities and structural diversity.1 Based on the linkage in the 3-position, they have been divided into the 3-acyl-, 3-alkyl- and 3-ether-modified subfamilies.1 While the biosynthesis of 3-acyl- (e.g., ilicicolin H) and 3-alkyl subfamilies (e.g., leporins, citridones, and pyridoxatin) have been well-studied with recent emphasis on ring-forming reactions,2–7 much less is known about the biosynthesis of 3-ether subfamily featuring the tetrahydropyran motif such as (−)-sambutoxin (1) (Figure 1A).

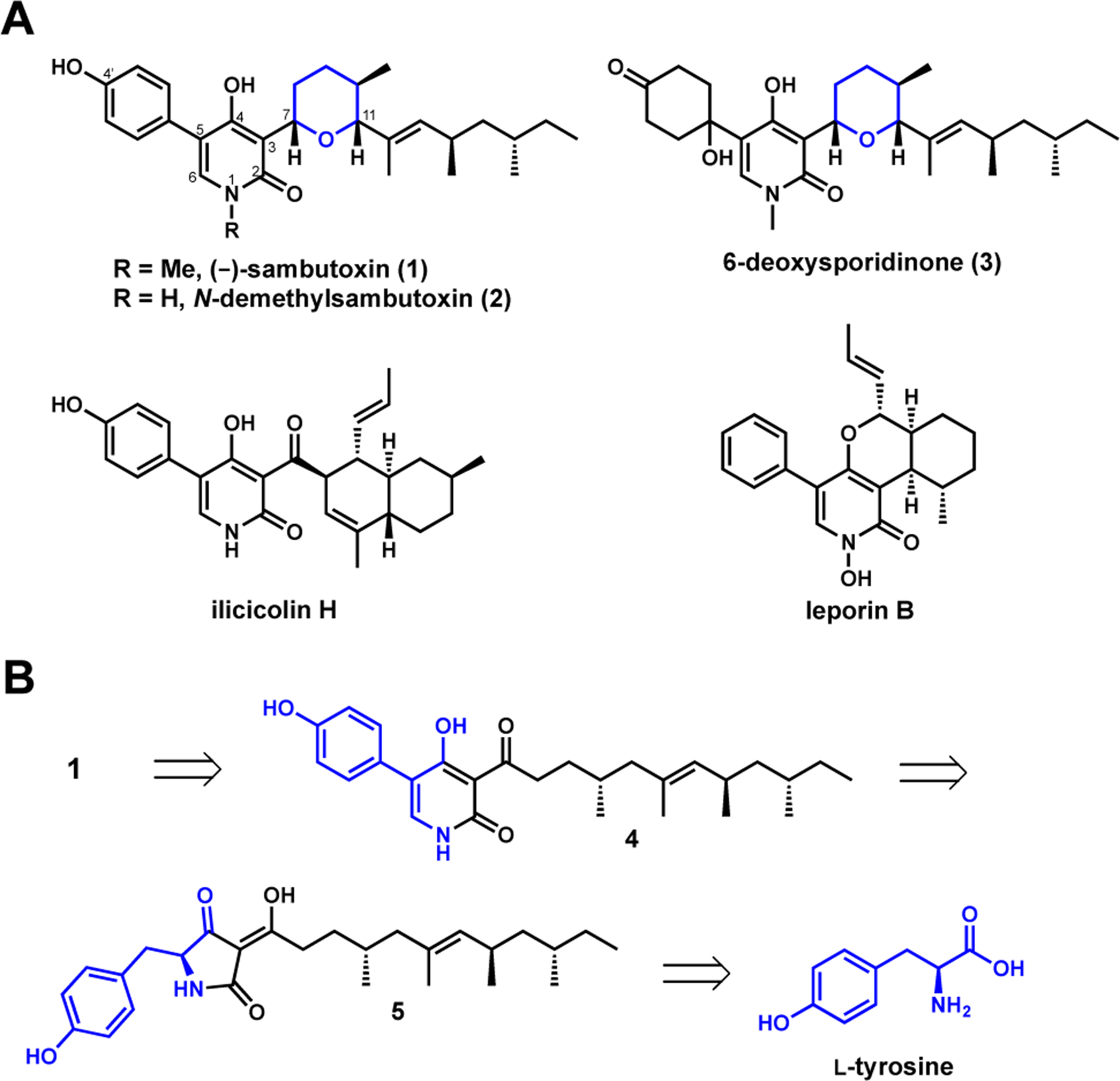

Figure 1.

4-Hydroxy-2-pyridone natural products. (A) Structures of (−)-sambutoxin (1) and related compounds; (B) Retrobiosynthesis of 1 suggests incorporation of tyrosine by the pathway.

First isolated from the potato parasite Fusarium sambucinum,8 1 exhibited toxicity in chicken embryos and human tumor cells and caused hemorrhages in rats. In addition, 1 has been co-isolated with structurally-related analogs such as N-demethylsambutoxin (2) and 6-deoxysporidinone (3) from another Fusarium plant pathogen.8,9 Given its potent biological activity and unique tetrahydropyranyl motif at C3 of the 2-pyridone core, 1 has been subjected to total synthesis efforts that led to the assignment of its absolute stereochemistry.10

Based on the biosynthetic relationship of 1 to other 4-hydroxy-2-pyridone natural products,2–5,11 a retrobiosynthesis was proposed as shown in Figure 1B. We initially proposed the N-methylation to be catalyzed by a N-methyltransferase, a modification seen only in 1 and its co-metabolite 4-hydroxy-2-pyridones. The tetrahydropyran moiety in 1 was expected to form via an oxidative cyclization of the linear pyridone precursor 4, which is structurally similar to aspyridone A and pretenellin B.7,12,13 In turn, 4 may be derived from the P450-catalyzed ring expansion of the tetramic acid 5, which can be synthesized from the collaborative efforts of a polyketide synthase-nonribosomal peptide synthetase (PKS-NRPS) and a trans-enoyl reductase (ER). The NRPS module of the PKS-NRPS was expected to activate and amidate the polyketide acyl chain with L-tyrosine given the p-hydroxyphenyl group in 1.

Because the published strains that produce 1 were not available to our laboratory, we used a genome mining approach to identify possible biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) of 1 in other Fusarium species from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) fungal genome database. Querying the NCBI genome database with protein sequences of the PKS-NRPS (LepA), trans-ER (LepG), and P450RE (LepH) from the leporin B biosynthetic pathway,2 with the added requirement of a N-methyltransferase, arrived at a well-conserved BGC in several species of Fusarium (Figure 2A). Also present in the clusters were genes encoding a short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase (SDR) and two additional P450 monooxygenases. One of the species housing the cluster was Fusarium oxysporum, from which 1–3 have been previously isolated.9

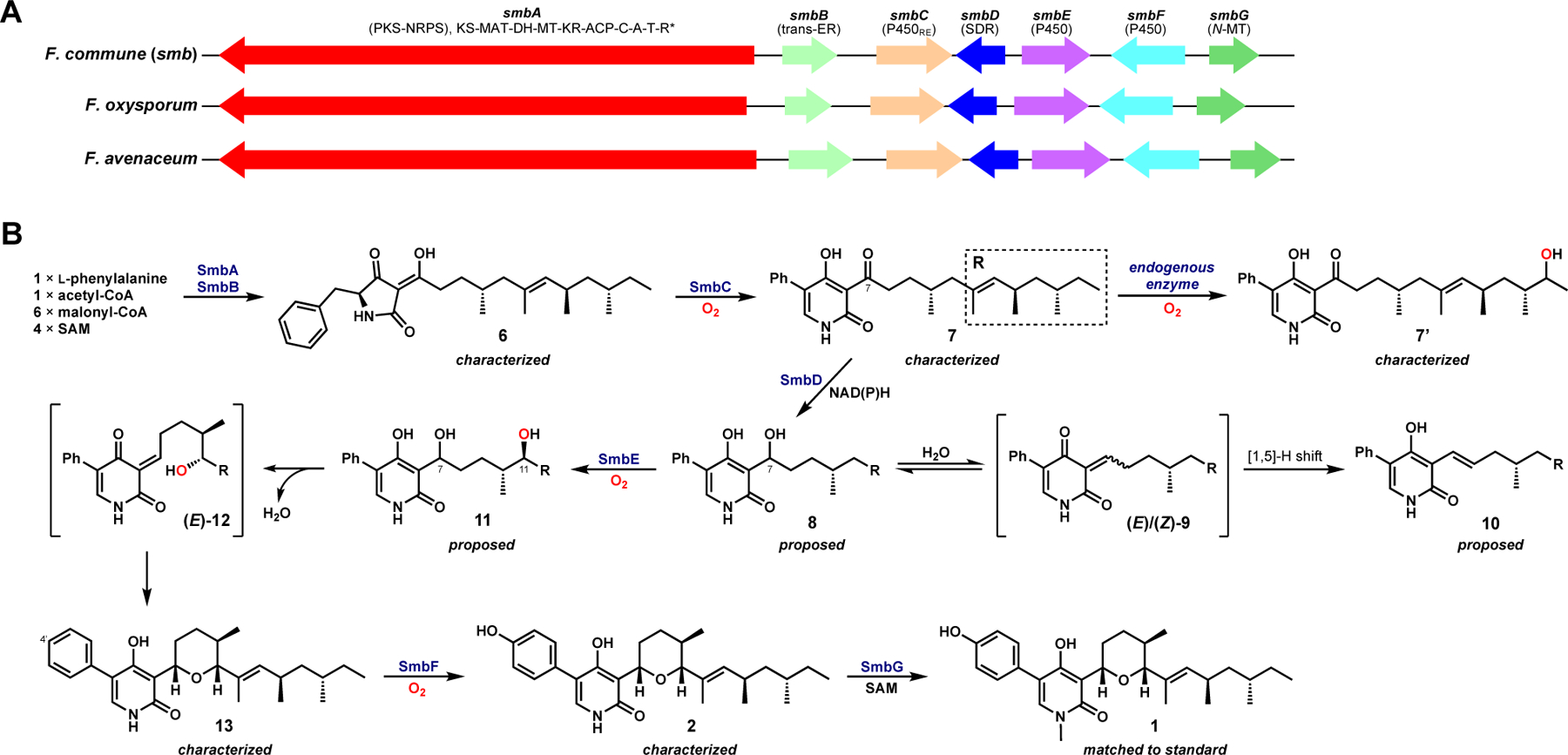

Figure 2.

Biosynthetic pathway to 1. (A) A conserved biosynthetic gene cluster from various species of Fusarium is proposed to be involved in the biosynthesis of 1. (B) Proposed biosynthetic pathway for 1 based on step-wise reconstitution.

To examine the products of the cluster (named smb), we chose to reconstitute the cluster from F. commune, of which we obtained the genomic DNA. The engineered strain of Aspergillus nidulans ΔSTΔEM14 was chosen for heterologous expression of smb genes due to its reduced endogenous metabolite background. Metabolites produced by this strain transformed with different combinations of smb genes are shown in Figure S3. First, co-expression of the PKS-NRPS (SmbA) and trans-ER (SmbB) gave a new compound 6 (Figure S3, trace ii) at a titer of 2 mg/L. Scaled-up culturing, isolation and structural characterization revealed 6 to be the tetramic acid shown in Figure 2B (Table S5 and Figures S7–S11). The polyketide portion of 6 is consistent with that proposed for 5, but it contained a phenyl group that is presumably derived from phenylalanine instead of the expected p-hydroxyphenyl group derived from tyrosine. No MS signal was observed for m/z of 442[M+H]+ corresponding to the tyrosine-derived tetramic acid 5. This initial surprise suggested that SmbA exclusively accepts phenylalanine to make the early-stage intermediate in the pathway to 1. While this work was underway, Õmura and Shiomi reported the isolation of fusaramin, a co-metabolite of 1–3 from Fusarium sp. derived from hydroxylation of the Cβ of phenylalanine in 6.15 Together with our identification of 6, the isolation of fusaramin suggested that contrary to our initial proposal, the biosynthesis of 1 starts with phenylalanine, and the p-hydroxy group of 1 is introduced at a later stage.

Next, co-expression of SmbC, which has sequence similarity to other characterized ring expansion P450s (P450RE), with SmbA and SmbB resulted in the production of 7 (Figure 2B and Figure S3, trace iv). 7 was structurally confirmed to be the 2-pyridone ketone (Table S6 and Figures S6A, S12–S16), consistent with the functions of P450RE enzymes in other 2-pyridone alkaloid pathways.2–4,16 In addition to 7, a co-metabolite 7’ with +16 mu was also isolated and characterized (Figure 2B and Table S7, Figures S17–S21). 7’ was found to contain a secondary alcohol in polyketide chain of 7, which may be attributed to the activity of endogenous alkyl hydroxylases in A. nidulans observed in other reconstitution studies.17,18 It is worth noting here that 7’ persists throughout the remaining reconstitution work (Figure S3) and is not modified by the downstream smb enzymes.

With 7 in hand, we next investigated the sequence of transformations leading to the formation of the tetrahydropyran. In the biosynthesis of other cyclic 2-pyridone such as leporins and citridones, the C7 ketone is reduced by a SDR to C7 alcohol and dehydrated to yield a reactive ortho-quinone methide (o-QM) that can serve as dienes or (di)enophiles in pericyclic reactions2,4,5,19. In the smb pathway, SmbD displayed moderate sequence homology to LepF2 and PfpC4 (36%). When co-expressed with SmbA–C, two new metabolites, 8 and 10, with m/z 426[M+H]+ and 408[M+H]+, respectively, were produced (Figure S3, trace v). Neither compound was isolated for NMR characterization due to low amounts and relative instability. However, based on the mass and biosynthetic logic, we propose that 8 is the C7 alcohol following the ketoreduction of 7, and 10 with more extended conjugation (Figure S4) is the [1,5]-hydride shifted shunt product (Figure 2B). These putative assignments were supported by chemical reduction of 7 with NaBH4, a method that has been used in previous 2-pyridone studies to verify SDR functions.2,5 Here, chemical reduction of 7 led to the same two compounds 8 and 10, eluting at the same retention time with the same MS and UV profiles (Figure S3, traces v and xii). Compound 10 may be formed via dehydration of 8 to either the (E)- or (Z)- o-QM 9, which may subsequently undergo a [1,5]-hydride shift as observed in the synthetic study of 2-pyridones.20 One product of the chemical reduction of 7 that was not detected from A. nidulans reconstitution is the likely methoxy adduct 8’ (Figure S4, traces ii and iii) resulting from the addition of solvent methanol to 9. The co-emergence of 8 and 10 upon heterologous co-expression of SmbA-D as well as in the NaBH4 reduction of 7 supports that SmbD functions as a ketoreductase, consistent with previous studies of their homologs,2,5 and it also suggests that an additional enzyme that can function on 8 is need to minimize shunt product formation.

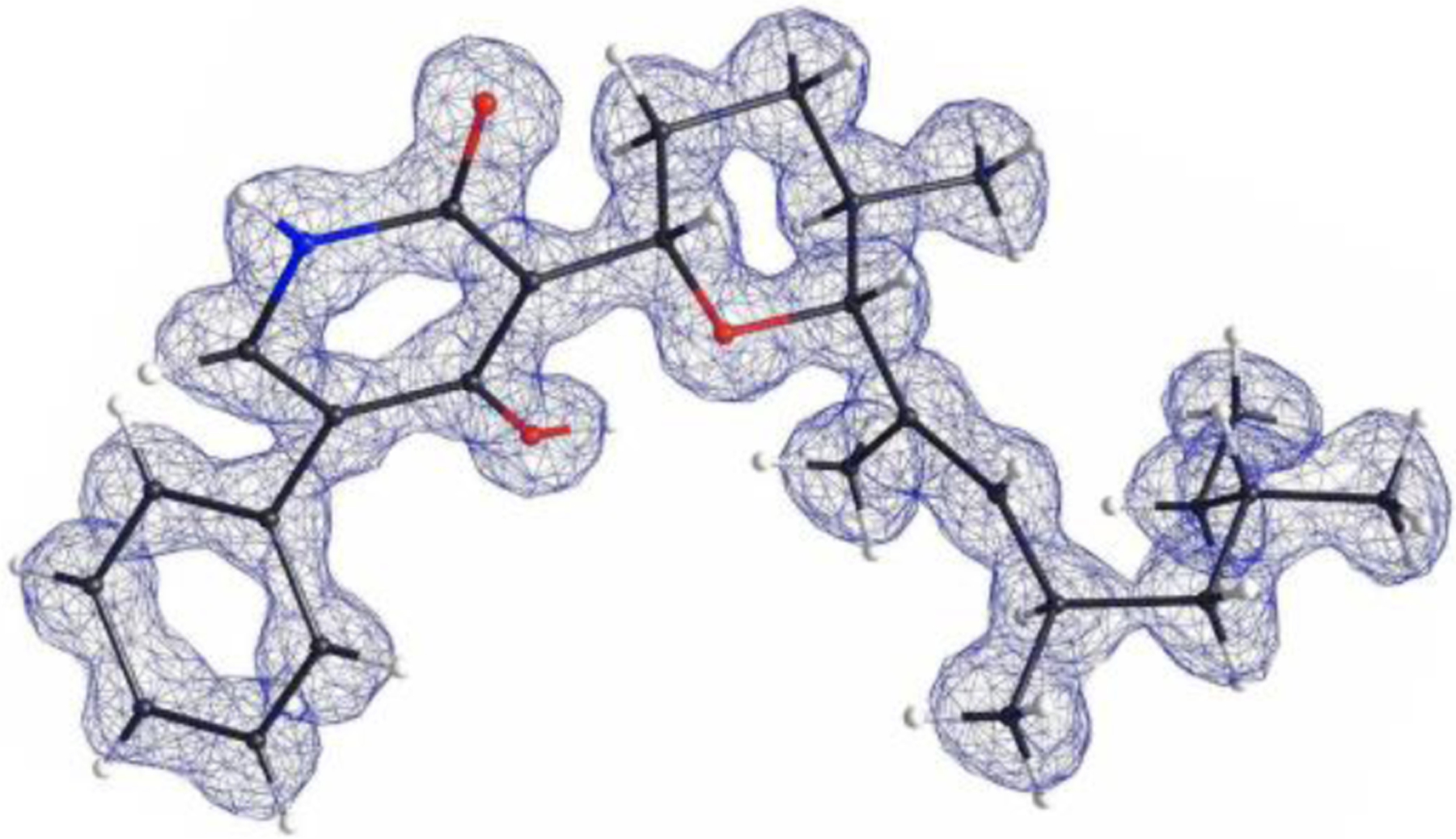

Given that electrophilic o-QMs can serve as Michael acceptors in nucleophilic additions21,22, we propose that the (E)- o-QM formed by a stereospecific dehydration of 8 serves as a Michael acceptor for the tetrahydropyran formation. This would require the installation of a (R)-hydroxyl group at C11 of the polyketide chain as in (E)-12 to serve as an internal nucleophile (Figure 2B). The Michael addition could take place in a stereospecific manner without enzymatic control given the bulky groups on C2 and C6 of the tetrahydropyran would preferentially assume the equatorial positions (Figure S1), as demonstrated in the total syntheses of (+)-1 and septoriamycin (Figure S1).10,23 Hydroxylation of the allylic C11 in 8 can be catalyzed by one of the remaining P450 enzymes, SmbE or SmbF. No new metabolite was produced (8 and 10 remained) when SmbF was co-expressed with SmbA–D (vida infra) (Figure S3, trace vi). In contrast, co-expression of SmbE with SmbA–D led to significant changes in the metabolite profile (Figure S3, trace vii). A new metabolite 13 with m/z 424[M+H]+ emerged (titer of 3.7 mg/L), accompanied by a significant decrease in the level of 8 (Figure S3, trace vii). Structural characterization of 13 by NMR (Table S8 and Figures S22–S26) revealed the compound to indeed contain the tetrahydropyran moiety found in 1. To further verify that the relative stereochemistries of the tetrahydropyran and methyl groups in the polyketide chain are consistent with the reported structure of 1, we obtained the three-dimensional structure of 13 using microcrystal electron diffraction (MicroED)24 (Figure 3). Microcrystals of 13 were obtained by slow air evaporation of a pure HPLC fraction of 13 in acetonitrile/water. The relative stereochemistry of 13 was identical to that reported for (−)-1, confirming that 13 is most likely an on-pathway intermediate, and that SmbE functions as the C11 hydroxylase to enable the tetrahydropyran formation via an intramolecular Michael addition.

Figure 3.

MicroED structure of 13.

It is interesting to note that up to 13 in the sambutoxin biosynthetic pathway, the aromatic ring at C4’ has remained an un-oxidized phenyl group, in contrast to the p-hydroxyphenyl group in 1. Given that the remaining enzymes in the cluster were another P450 (SmbF) and an N-MT (SmbG), we anticipated that SmbF would oxidize the C4’ of the phenyl group to give 2. Indeed, when SmbF was co-expressed with SmbA–E in A. nidulans, the strain produced a new compound 2 (titer of 2 mg/L) that was confirmed to be N-demethylsambutoxin (Figure S3, trace x; Table S9 and Figures S27–S31). As a result, SmbF was assigned as the C4’-hydroxylase in this pathway. The timing of SmbF function must follow tetrahydropyran formation initiated by SmbE, as no phenyl hydroxylation activity was observed when SmbF was expressed with SmbA–D in the absence of SmbE.

Two possible mechanism can be proposed for the SmbF-catalyzed aryl hydroxylation: i) abstraction of hydrogen from the weak amide N1-H bond generates a free radical that can be delocalized to C4’ on the phenyl ring (Figure S6C), which could further react with the iron-bound hydroxyl radical in SmbF to complete the regiospecific C4’-hydroxylation; or ii) epoxidation at C3’-C4’ of the phenyl group is followed by 1,2-hydride (NIH) shift to form the 4’-OH group in a mechanism that is similar to that reported for cinnamate hydroxylase (Figure S6D).25 This late-stage C-H oxidation by SmbF to oxidize the para position of the phenylalanine-derived phenyl group is rather unique in the biosynthesis of polyketide-nonribosomal peptide hybrid molecules. For tenellin, aspyridone, and illicicolin H, the p-hydroxyphenyl groups are all introduced at the start of biosynthetic pathways via incorporation of tyrosine by the respective PKS-NRPSs.3,7,12 It is thus intriguing that the biosynthesis of sambutoxin does not begin with tyrosine, which could lead to a shorter and more efficient pathway. One possible explanation for the choice of phenylalanine by SmbA is that some P450RE enzymes are capable of dephenylating tyrosine-containing tetramic acids in the process of ring expansion (Figure S6B).5,26 The p-hydroxyphenyl group in the tetramic acid is critical for dephenylation, which has been shown to occur in the biosynthesis of pyridoxatin5, aspyridone7, harzianopyridone.26 Dephenylation of 5 would derail the biosynthesis of 1, hence rationalizing the strategy employed by the smb pathway to first incorporate a phenylalanine at the early stage of sambutoxin biosynthesis and dedicate a separate enzyme to oxidize the phenyl group at a later stage in the pathway when dephenylation is no longer possible.

From 2, the remaining N-MT (SmbG) is proposed to perform the N-methylation to afford 1. When SmbG was co-expressed with SmbA–F in A. nidulans, we observed a small peak with m/z 454[M+H]+ that eluted at the same retention time as a commercial standard of 1 (Figure S3, traces xi and xiii). Attempts to purify sufficient amount of 1 for NMR structural characterization from 4L of cultures was unsuccessful due to low titer, possibly due to unknown degradation/detoxification pathways in the host. However, we were able to demonstrate that recombinantly expressed SmbG is capable of N-methylating 2 in vitro (KM = 54.7 ± 11.4 μM, kcat = 1.70 ± 0.13 min–1, and kcat/KM = 3.1 × 104 min–1 M–1) to give 1 in the presence of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) (Figure S5). SmbG specifically methylated 2 and was inactive on 13, as no new peak corresponding to the N-methylated derivative of 13 was observed upon reaction with SmbG and SAM. These results confirmed that the N-methylation of 2 to 1 by SmbG is the final step to complete the biosynthetic pathway of 1.

In summary, we have uncovered the linear biosynthetic pathway for 1, providing insight into nature’s strategy for synthesizing the tetrahydropyran motif in 4-hydroxy-2-pyridone alkaloids. This is the first example from 4-hydroxy-2-pyridone alkaloid biosynthesis in which the p-hydroxyphenyl group at C4’ is derived not from tyrosine but rather via a late-stage oxidation of phenylalanine. Full reconstitution of the biosynthesis of 1 enables genome-based mapping of fungi capable of making this toxin and sets the stage for the investigation of related compounds such as 6-deoxysporidinone (3).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was supported by grants from the NIH (1R01AI141481) to Y.T. We thank Prof. David Williams from Indiana University for his generous sample of (+)-sambutoxin. E.G. was supported by the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website.

Experimental details and spectroscopic data (NMR, UV-Vis absorption, HRMS).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- (1).Jessen HJ; Gademann K 4-Hydroxy-2-Pyridone Alkaloids: Structures and Synthetic Approaches. Nat. Prod. Rep 2010, 27 (8), 1168–1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Ohashi M; Liu F; Hai Y; Chen M; Tang M; Yang Z; Sato M; Watanabe K; Houk KN; Tang Y SAM-Dependent Enzyme-Catalysed Pericyclic Reactions in Natural Product Biosynthesis. Nature 2017, 549 (7673), 502–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Zhang Z; Jamieson CS; Zhao Y-L; Li D; Ohashi M; Houk KN; Tang Y Enzyme-Catalyzed Inverse-Electron Demand Diels–Alder Reaction in the Biosynthesis of Antifungal Ilicicolin H. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (14), 5659–5663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Zhang Z; Qiao T; Watanabe K; Tang Y Concise Biosynthesis of Phenylfuropyridones in Fungi. Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2020, 59 (45), 19889–19893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Ohashi M; Jamieson CS; Cai Y; Tan D; Kanayama D; Tang M-C; Anthony SM; Chari JV; Barber JS; Picazo E; Kakule TB; Cao S; Garg NK; Zhou J; Houk KN; Tang Y An Enzymatic Alder-Ene Reaction. Nature 2020, 586 (7827), 64–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Halo LM; Heneghan MN; Yakasai AA; Song Z; Williams K; Bailey AM; Cox RJ; Lazarus CM; Simpson TJ Late Stage Oxidations during the Biosynthesis of the 2-Pyridone Tenellin in the Entomopathogenic Fungus Beauveria Bassiana. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130 (52), 17988–17996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Wasil Z; Pahirulzaman KAK; Butts C; Simpson TJ; Lazarus CM; Cox RJ One Pathway, Many Compounds: Heterologous Expression of a Fungal Biosynthetic Pathway Reveals Its Intrinsic Potential for Diversity. Chem. Sci 2013, 4 (10), 3845–3856. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kim J-C; Lee Y-W; Tamura H; Yoshizawa T Sambutoxin: A New Mycotoxin Isolated from Fusarium Sambucinum. Tetrahedron Letters 1995, 36 (7), 1047–1050. [Google Scholar]

- (9).Jayasinghe L; Abbas HK; Jacob MR; Herath WHMW; Nanayakkara NPD N-Methyl-4-Hydroxy-2-Pyridinone Analogues from Fusarium Oxysporum. J. Nat. Prod 2006, 69 (3), 439–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Williams DR; Turske RA Construction of 4-Hydroxy-2-Pyridinones. Total Synthesis of (+)-Sambutoxin. Org. Lett 2000, 2 (20), 3217–3220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Fisch KM Biosynthesis of Natural Products by Microbial Iterative Hybrid PKS–NRPS. RSC Adv. 2013, 3 (40), 18228–18247. [Google Scholar]

- (12).Eley KL; Halo LM; Song Z; Powles H; Cox RJ; Bailey AM; Lazarus CM; Simpson TJ Biosynthesis of the 2-Pyridone Tenellin in the Insect Pathogenic Fungus Beauveria Bassiana. ChemBioChem 2007, 8 (3), 289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Bergmann S; Schümann J; Scherlach K; Lange C; Brakhage AA; Hertweck C Genomics-Driven Discovery of PKS-NRPS Hybrid Metabolites from Aspergillus Nidulans. Nat Chem Biol 2007, 3 (4), 213–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Liu N; Hung Y-S; Gao S-S; Hang L; Zou Y; Chooi Y-H; Tang Y Identification and Heterologous Production of a Benzoyl-Primed Tricarboxylic Acid Polyketide Intermediate from the Zaragozic Acid A Biosynthetic Pathway. Org. Lett 2017, 19 (13), 3560–3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Sakai K; Unten Y; Iwatsuki M; Matsuo H; Fukasawa W; Hirose T; Chinen T; Nonaka K; Nakashima T; Sunazuka T; Usui T; Murai M; Miyoshi H; Asami Y; Ōmura S; Shiomi K Fusaramin, an Antimitochondrial Compound Produced by Fusarium Sp., Discovered Using Multidrug-Sensitive Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. The Journal of Antibiotics 2019, 72 (9), 645–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Kim LJ; Ohashi M; Tan D; Asay M; Cascio D; Rodriguez J; Tang Y; Nelson H Structural Determination of an Orphan Natural Product Using Microcrystal Electron Diffraction and Genome Mining. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- (17).Liu N; Abramyan ED; Cheng W; Perlatti B; Harvey CJB; Bills GF; Tang Y Targeted Genome Mining Reveals the Biosynthetic Gene Clusters of Natural Product CYP51 Inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143 (16), 6043–6047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Zhu Y; Wang J; Mou P; Yan Y; Chen M; Tang Y Genome Mining of Cryptic Tetronate Natural Products from a PKS-NRPS Encoding Gene Cluster in Trichoderma Harzianum t-22. Org. Biomol. Chem 2021, 19 (9), 1985–1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Chen Q; Gao J; Jamieson C; Liu J; Ohashi M; Bai J; Yan D; Liu B; Che Y; Wang Y; Houk KN; Hu Y Enzymatic Intermolecular Hetero-Diels–Alder Reaction in the Biosynthesis of Tropolonic Sesquiterpenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (36), 14052–14056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Fotiadou AD; Zografos AL Accessing the Structural Diversity of Pyridone Alkaloids: Concise Total Synthesis of Rac-Citridone A. Org. Lett 2011, 13 (17), 4592–4595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Purdy TN; Kim MC; Cullum R; Fenical W; Moore BS Discovery and Biosynthesis of Tetrachlorizine Reveals Enzymatic Benzylic Dehydrogenation via an Ortho-Quinone Methide. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2021, 143 (10), 3682–3686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Doyon TJ; Perkins JC; Baker Dockrey SA; Romero EO; Skinner KC; Zimmerman PM; Narayan ARH Chemoenzymatic O-Quinone Methide Formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2019, 141 (51), 20269–20277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Nakamura T; Harachi M; Kano T; Mukaeda Y; Hosokawa S Concise Synthesis of Reduced Propionates by Stereoselective Reductions Combined with the Kobayashi Reaction. Org. Lett 2013, 15 (12), 3170–3173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Jones CG; Martynowycz MW; Hattne J; Fulton TJ; Stoltz BM; Rodriguez JA; Nelson HM; Gonen T The CryoEM Method MicroED as a Powerful Tool for Small Molecule Structure Determination. ACS Cent. Sci 2018, 4 (11), 1587–1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Ortiz de Montellano PR; Nelson SD Rearrangement Reactions Catalyzed by Cytochrome P450s. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2011, 507 (1), 95–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Bat-Erdene U; Kanayama D; Tan D; Turner WC; Houk KN; Ohashi M; Tang Y Iterative Catalysis in the Biosynthesis of Mitochondrial Complex II Inhibitors Harzianopyridone and Atpenin B. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2020, 142 (19), 8550–8554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.