Abstract

Objective

To determine the odds of accessing telemedicine either by phone or by video during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We performed a retrospective study of patients who were seen at a single academic institution for a urologic condition between March 15, 2020 and September 30, 2020. The primary outcome was to determine characteristics associated with participating in a telemedicine appointment (video or telephone) using logistic regression multivariable analysis. We used a backward model selection and variables that were least significant were removed. We adjusted for reason for visit, patient characteristics such as age, sex, ethnicity, race, reason for visit, preferred language, and insurance. Variables that were not significant that were removed from our final model included median income estimated by zip code, clinic location, provider age, provider sex, and provider training.

Results

We reviewed 4234 visits: 1567 (37%) were telemedicine in the form of video 1402 (33.1%) or telephone 164 (3.8%). The cohort consisted of 2516 patients, Non-Hispanic White (n = 1789, 71.1%) and Hispanic (n = 417, 16.6%). We performed multivariable logistic regression analysis and demonstrated that patients who were Hispanic, older, or had Medicaid insurance were significantly less likely to access telemedicine during the pandemic. We did not identify differences in telemedicine utilization when stratifying providers by their age, sex, or training type (physician or advanced practice provider).

Conclusion

We conclude that there are differences in the use of telemedicine and that this difference may compound existing disparities in care. Additionally, we identified that these differences were not associated with provider attributes. Further study is needed to overcome barriers in access to telemedicine.

The novel coronavirus, COVID-19, is causing significant disruption in healthcare delivery throughout the United States with accelerated adoption of telemedicine platforms to deliver ambulatory care. Many urologic practices are shifting resources to deliver urologic care in the form of telemedicine.1 Further, some authors have suggested that telemedicine might be used to reach underserved and rural populations who might lack urologic care.2 , 3 Ultimately, little is known about how urologic practices have adopted this technology and the characteristics of the patients engaging in telemedicine visits. Current analyses on this subject are limited to small studies prior to the pandemic or small surveys of patients about their preferences.4 Secondly, little is known about the association of provider bias on telemedicine utilization.

We sought to determine differences in telemedicine usage at an academic urologic practice which serves a diverse regional population during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Due to the rapid adoption of telemedicine some populations might be disproportionately lack access to telemedicine further impacting care. We hypothesized that there might be disparities in the adoption of telemedicine depending on patient characteristics.

METHODS

We retrospectively identified patients older than 18 years old who were seen for a urologic condition between March 15, 2020 and September 30, 2020 at a single institution. Our institution, UC San Diego Health, is a large academic institution serving the County of San Diego. We have two hospitals that are within close proximity to each other. Patients were seen within hospital-based clinics at these two sites by a cumulative sum of 23 providers.

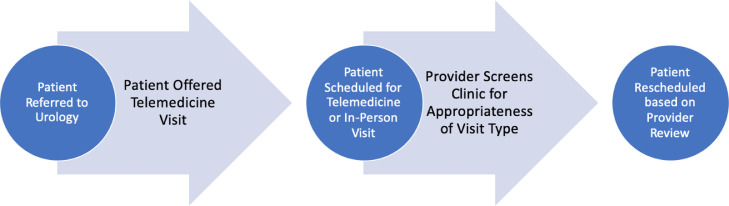

Patients were excluded if they participated in a procedure visit (ie, cystoscopy or prostate biopsy). All patients were offered a telemedicine (video or telephone) visit and providers were asked to review whether this was appropriate prior to scheduling. Prior to March 15, 2020 telemedicine was not available to providers or patients in the clinic setting at our institution. The clinic work flow is further detailed in Figure 1 .

Figure 1.

Clinic work flow. (Color version available online.)

We grouped ICD-10 codes to identify the reason for visit into the following categories, general urology/endourology, reconstructive, infertility, oncology, and female urology. Our primary outcome was to determine patient characteristics associated with the use of telemedicine services either by phone or video using multivariable logistic regression analysis. We performed a stepwise backward model selection. Variables that were the least significant were removed. Variables that were not significant that were removed included median income estimated by zip code, clinic location, provider age, provider sex, and provider training. The final model adjusted for patient characteristics such as age, sex, ethnicity, race, reason for visit, preferred language, and insurance.

We evaluated provider characteristics to determine if there was variation in provider usage of telemedicine. We used Chi-squared distribution to evaluate telemedicine usage by provider age, sex, and training (Advanced Practice Provider or Physician. We did not have access to provider race/ethnicity. We also performed a sensitivity analysis excluding providers with less than 30 patients seen within the time period. We performed a secondary sensitivity analysis removing billing codes to identify outlier visits that may necessitate in-person follow up. This was determined by identifying that certain billing codes (ie, testicular mass) were more likely to result with in-person follow up.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v.27 (IBM, Armonk, NY). P-value <.05 was considered to be significant. This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board, IRB #200724.

RESULTS

Over a period of 6.5 months, we analyzed a total of 4234 visits from 2516 patients over the study period; 1567 (37%) were telemedicine in the form of video 1402 (33.1%) or telephone 164 (3.8%) (Table 1 ). There were a total of 2516 unique patients included. Our cohort was notable for a large proportion of patients older than 65 years old (n = 1653, 65.7%), male (n = 2092, 83.1%), White race (n = 1789, 71.1%), English speaking (n = 2242, 89.1%), with commercial insurance (n = 1264, 50.2%) or Medicare (n = 1,1559 46.1%). Our sample size is notable for an ethnically diverse patient population including 417 (16.6%) Hispanic patients. A majority of visits were for general urology/endourology (n = 2300, 54.6%).

Table 1.

Demographics

| Patients With Any Visit | In-Persson Visits | Telemedicine Visits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in Years | |||

| <55 | 316 (12.6%) | 318 (11.9%) | 225 (14.4%) |

| 55-64 | 547 (21.7%) | 582 (21.8%) | 321 (20.5%) |

| 65-74 | 948 (37.7%) | 1010 (37.9%) | 610 (38.9%) |

| >75 | 705 (28.0%) | 757 (28.4%) | 411 (26.2%) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 2092 (16.9%) | 426 (16.0%) | 264 (16.8%) |

| Male | 424 (83.1%) | 2241 (84.0%) | 1303 (83.2%) |

| Race Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 417 (16.6%) | 496 (18.6%) | 234 (14.9%) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 155 (6.2%) | 158 (5.9%) | 87 (5.6%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 99 (3.9%) | 105 (3.9%) | 57 (3.6%) |

| Other | 159 (6.3%) | 187 (7.0%) | 104 (6.6%) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1686 (67.0%) | 171 (64.5%) | 1085 (69.2%) |

| Preferred Language | |||

| Spanish | 189 (7.5%) | 242 (9.1%) | 107 (6.8%) |

| Other | 85 (3.4%) | 98 (3.7%) | 50 (3.2%) |

| English | 2242 (89.1%) | 2327 (87.3%) | 1410 (90.0%) |

| Insurance | |||

| Commercial | 1264 (50.2%) | 1285(48.2%) | 771 (49.2%) |

| Medicare | 1159 (46.1%) | 1257 (47.1%) | 743 (47.4%) |

| Other | 48 (1.9%) | 49 (1.8%) | 27 (1.7%) |

| Medicaid | 45 (1.8%) | 76 (2.8%) | 26 (1.7%) |

| Reason for Visit | |||

| General Urology/Endourology | 2300 (54.6%) | 807 (51.8%) | 1493 (56.2%) |

| Female Urology | 437 (10.4%) | 276 (10.4%) | 161 (10.03%) |

| Urologic Oncology | 479 (18.0%) | 282 (18.1%) | 761 (18.1%) |

| Reconstructive Surgery | 110 (4.1%) | 46 (3.0%) | 156 (3.7%) |

| Infertility | 297 (11.22%) | 26 (16.8%) | 559 (13.3%) |

In multivariable analysis (Table 2 ), patients were less likely to access telemedicine if they were older (reference age <55 years), ≥75 [Odds Ratio (OR) 0.69, 95% Confidence Interval (CI) 0.54-0.88, P = .003], 65-74 (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.64-0.98, P = .0.049) and 55-64(OR 0.79, 95%CI 0.63-0.99, P = .044). Patients were also less likely to access telemedicine if they were Hispanic (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.61-0.97, P = .028) or if patients had Medicaid insurance (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.38-0.97, P = .040). We also identified that patients were more likely to participate in a telemedicine visit if they were seen for a urologic condition related to infertility (OR 1.43, 95%CI 1.14-1.80, P = .002).

Table 2.

Multivariable regression analysis

| Variable | OR | 95 % CI | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 0.77 | 0.61-0.97 | .028 |

| Asian | 0.89 | 0.67-1.19 | .455 |

| Black | 0.85 | 0.61-.120 | .367 |

| Other | 0.86 | 0.66-1.12 | .287 |

| White | Referent | ||

| Language | |||

| Spanish | 0.89 | 0.65-1.23 | .510 |

| Other | 0.92 | 0.63-1.35 | .695 |

| English | Referent | ||

| Age | |||

| ≥75 | 0.69 | 0.54-0.88 | .003 |

| 65-74 | 0.80 | 0.64-0.98 | .049 |

| 56-64 | 0.79 | 0.63-0.99 | .044 |

| ≤ 55 | Referent | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 1.16 | 0.97-1.39 | .099 |

| Male | Referent | ||

| Insurance | |||

| Other | 0.97 | 0.60-1.58 | .926 |

| Medicaid | 0.61 | 0.38-0.97 | .040 |

| Medicare | 1.06 | 0.91-1.24 | .412 |

| Commercial | Referent | ||

| Reason for Visit | |||

| Urologic Oncology | 0.90 | 0.75-1.07 | .239 |

| Infertility | 1.43 | 1.14-1.80 | .002 |

| Reconstructive | 0.69 | 0.47-1.00 | .056 |

| Female Urology | 0.94 | 0.73-1.21 | .663 |

| General Urology/Endourology | Referent |

We also evaluated provider characteristics to determine if there were differences in the utilization of telemedicine based on provider attributes. There was no difference in telemedicine usage when stratifying providers by their training type (P = .867), age (P = .104), or sex (P = .228) (Supplemental Table 1).

In our sensitivity analysis, patients were less likely to access telemedicine if they were older (referent age <55 years), ≥75 (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.51-0.85), 65-74 (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.58 -0.94) and 55-64(OR 0.78, 95%CI 061-0.99, P = .043). Patients were also less likely to access telemedicine if they were Hispanic (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.62-0.95, P = .017) or if patients had Medicaid insurance (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.36-0.98, P = .044). We also identified that patients were more likely to participate in a telemedicine visit if they were seen for a urologic condition related to infertility (OR 1.40, 95%CI 1.12-1.77, P = .003) (Supplemental Table 2).

We performed a secondary sensitivity analysis removing billing codes to identify outlier visits that may necessitate in-person follow up (ie, testicular mass). These results can be found in Supplemental Table 3.

DISCUSSION

In our study we present one largest retrospective analyses of urologic patients who accessed telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. Providers were asked to pre-screen their clinics prior to appointments to determine if patients should be converted to a telemedicine visit. Our analysis demonstrates that telemedicine was routinely utilized by patients over the study period, with 37% of visits being conducted by phone or video. We found that patients who were of Hispanic ethnicity, older, or on Medicaid insurance were less likely to utilize telemedicine. This variation does not appear to be attributable to provider characteristics. Accelerated adoption of telemedicine to provide care in an ambulatory academic urologic setting spurred on by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with significant differences in access which may compound existing age, racial/ethnic, and insurance-related disparities.

Until recently, telemedicine utilization was low in large part due to reimbursement related concerns, resistance to change, or patient related factors and concerns.5 Lonergan et al evaluated 12,946 video visits at a cancer center and identified no disparities in terms of uptake of telemedicine comparing pre- and post-COVID-19 periods in terms of race/ethnicity, primary language, or payor. However, the authors did not compare telemedicine to in-person visits and it remains unclear if there were disparities in the post-COVID-19 period.6 Chao et. al evaluated 109 610 surgical visits and found that urology had the highest conversion rate to telemedicine, 14.3%. However, the authors did not evaluate patient characteristics of telemedicine usage. Our study is amongst the first to look at the specific characteristics of urology patients who are accessing telemedicine. We identified that Hispanic in itself was associated with a lower odds of accessing telemedicine. Rodriguez et al evaluated 162,102 patients mostly from primary care and found that patients who Hispanic were less likely to utilize telemedicine (OR 0.76, 95% CI 0.73-0.80). Our results mirror those of Rodriguez further indicating that for specialty care like urology there are similar differences in telemedicine utilization.

These findings are also unique in identifying that patient who were older than 60 were less likely to utilize telemedicine compared to younger patients. Nearly two thirds of the urologic population is older than 65 years old. This cohort of patients is also considered to be amongst the highest risk population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Boehm et al interviewed 399 urologic patients in March 2020 and found that patients 76 or older had a negative view of telemedicine.4 Narasimha et al reviewed articles focused on telemedicine in geriatric patients and suggested there is limited research in this cohort of patients when designing telemedicine systems. Secondly the utility of telemedicine technology in an increasingly older population of patients and its impact on cognition and behavior is largely unknown.7 Our study indicates that there are age related differences in telemedicine usage. This may stem from patient comfort with the use of technology or preference for an in-person visit. Further efforts are needed to address age related disparities in the usage of telemedicine. These can include patient education sessions on telemedicine usage or tablet loan programs.8

We identified that Medicaid was independently associated with a lower usage of telemedicine. While this finding might be expected, it highlights that integration of telemedicine usage into routine practice needs to be further evaluated to not disadvantage this patient population. Prior to the pandemic, Medicaid beneficiaries were severely limited in their utilization of telemedicine and there were substantial regulatory barriers that were waived due to the pandemic 9 Ray et al evaluated 42,695 pediatric Medicaid beneficiaries in 2014 and demonstrated that telemedicine was used in 146 (0.3%) of visits. Our findings indicate that telemedicine may provide a means of reaching this at-risk population but that focused efforts on identifying patient related barriers are critical to future success.

Lastly, we identified that there was nearly equal uptake of telemedicine by all providers. We did not notice any difference in telemedicine utilization when stratifying physicians by their age, sex, or training (physician or advanced practice provider). Thus, our study indicates that telemedicine can be successfully integrated into physician practice on a routine basis.

Our study has limitations; firstly, our cohort consists of largely older patients. However, we include a robust distribution of patients across all age spectrums and this cohort is most reflective of urologic practices. Secondly, we could not account for unmeasurable inherent provider bias, which may impact the utilization of telemedicine. Third, we identified that infertility related visits were more likely to be conducted via telemedicine, however our practice employs 2 infertility providers and thus it remains unclear if this truly a trend in utilization of telemedicine or bias. Fourth, due to limitations of the database we could not reliably differentiate new patients from follow up patients. Lastly, we could not assess the quality of the visits or visit length, and further analysis of this is needed.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our results underscore that telemedicine can be successfully integrated into urologic practices but there are disparities in utilization based on patient age, race/ethnicity, and insurance status. Urologic community vigilance is necessary to promote equal access to telemedicine modalities as this technology will continue to be an integral role in future practice.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2021.11.037.

Appendix. SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

REFERENCES

- 1.Gadzinski AJ, Gore JL, Ellimoottil C, Odisho AY, Watts KL. Implementing telemedicine in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Urol. 2020 doi: 10.1097/JU.0000000000001033. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller A, Rhee E, Gettman M, Spitz A. The current state of telemedicine in urology. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102:387–398. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Javier-DesLoges JF, Segal D, Khan A, et al. Urology residency training in medically underserved areas through the integration of a federally qualified health center rotation. Urology. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.11.057. Published online. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boehm K, Ziewers S, Brandt MP, et al. Telemedicine online visits in urology during the COVID-19 pandemic-potential, risk factors, and patients’ perspective. Eur Urol. 2020;78:16–20. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2020.04.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott Kruse C, Karem P, Shifflett K, Vegi L, Ravi K, Brooks M. Evaluating barriers to adopting telemedicine worldwide: a systematic review. J Telemed Telecare. 2018;24:4–12. doi: 10.1177/1357633X16674087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lonergan PE, Washington SL, III, Branagan L, et al. Rapid utilization of telehealth in a comprehensive cancer center as a response to COVID-19: cross-sectional analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22 doi: 10.2196/19322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narasimha S, Madathil KC, Agnisarman S, et al. Designing telemedicine systems for geriatric patients: a review of the usability studies. Telemed J E-Health Off J Am Telemed Assoc. 2017;23:459–472. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2016.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bridging the Digital Divide to Avoid Leaving the Most Vulnerable Behind | Medical Devices and Equipment | JAMA Surgery | JAMA Network. Accessed September 10, 2021. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamasurgery/fullarticle/2778016 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Ray KN, Mehrotra A, Yabes JG, Kahn JM. Telemedicine and outpatient subspecialty visits among pediatric medicaid beneficiaries. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20:642–651. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2020.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.