Abstract

With rising global demand for food proteins and significant environmental impact associated with conventional animal agriculture, it is important to develop sustainable alternatives to supplement existing meat production. Since fat is an important contributor to meat flavor, recapitulating this component in meat alternatives such as plant based and cell cultured meats is important. Here, we discuss the topic of cell cultured or tissue engineered fat, growing adipocytes in vitro that could imbue meat alternatives with the complex flavor and aromas of animal meat. We outline potential paths for the large scale production of in vitro cultured fat, including adipogenic precursors during cell proliferation, methods to adipogenically differentiate cells at scale, as well as strategies for converting differentiated adipocytes into 3D cultured fat tissues. We showcase the maturation of knowledge and technology behind cell sourcing and scaled proliferation, while also highlighting that adipogenic differentiation and 3D adipose tissue formation at scale need further research. We also provide some potential solutions for achieving adipose cell differentiation and tissue formation at scale based on contemporary research and the state of the field.

Keywords: Adipose, cell culture, tissue engineering, food, cellular agriculture, cultured fat, cultured meat, cultivated fat, cultivated meat, in vitro meat, in vitro fat, livestock, pig, pork, porcine, cow, beef, bovine, chicken, avian, galline, duck, buffalo, livestock, RNA delivery, omega 3, macroscale, scale up

Introduction

Conventional livestock production has been calculated by the United Nation’s Food and Agriculture Organization to be a significant contributor to human impact on the environment, comprising an estimated 15–18% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [1,2]. For comparison, this is higher than the 14% attributed to GHG emissions from global transportation, although the actual value of livestock GHGs is disputed [3–5]. Currently, animal farming uses at least one-third of arable land and fresh water [1,6,7]. Conventional animal agriculture also generates wastes such as manure, which contributes to groundwater and local ecosystem contamination as well as eutrophication [1,8–11]. Meat consumption is the largest driver of livestock production, and concerns over it extend to human health impacts, playing a role in the growth of antimicrobial resistance and the emergence of pathogenic diseases. The emergence of antimicrobial resistance has been associated with antibiotic use in animal agriculture systems, causing significant health and food safety complications through human contact with contaminated food, water or manure and the horizontal gene transfer of antibiotic resistance genes amongst microbes [12–15]. The emergence and spread of zoonotic diseases have been connected to livestock farming practices, with over half of all human pathogens classified as zoonotic and 73% of emergent pathogens identified as zoonotic [16,17].

As meat production is predicted to increase 1.8-fold by 2050 from 2005/2007 levels, the impact of conventionally produced meats on areas such as disease and the environment are at risk of further increasing [18]. Due to this, the emergence of alternative meats and proteins would be beneficial for supplementing existing production to meet rising demand for food proteins. Alternative proteins should be comparable in taste, texture, and sensory properties in order to satisfy the same consumer demand that drives meat consumption. Ideally, such alternatives should be made with minimal impact to the environment to promote food system sustainability. Plant based meats utilize plant or other non-animal components to mimic animal meat, bypassing the low efficiency feed to food conversion ratios encountered when raising livestock for meat (3% of calories and protein for beef) [19–21]. As an example, Beyond Meat produces plant based meat alternatives on a large scale, including a burger patty calculated to involve 90% less GHG emissions and land use, while requiring less than half the energy and over 99% less water when compared to traditional livestock-derived beef [22,23]. Similarly, the Impossible Burger claims to require 87% less water, 96% less land, 89% less GHGs and 92% less aquatic pollutants than its beef equivalent [24].

Cultured meat (also called in vitro, cultivated, lab grown, cell-based meat) is another alternative to traditional animal agriculture that aims to produce the skeletal muscle and adipose tissues that normally comprise animal meats, except using in vitro tissue and biological engineering techniques [25,26]. By directly growing meat in vitro, energy and nutrients can be more efficiently focused on the outcome – muscle and adipose as opposed to unused components such as the lungs and nerves [25,27,28]. While processes to produce cultured meat are still being scaled up, estimates based on current industry values and projections involve the emission of fewer GHGs and the use of much less land when compared to ruminant meat like beef and lamb. Estimations of energy requirements vary more widely, ranging far below and above that of conventional beef production [29–33]. Compared to the weight of livestock increasing linearly over time, the timeframe to generate cultured meat tissues in vitro is thought to be faster due to the exponential nature of in vitro cell proliferation (cell numbers doubling during each round of proliferation) [34–39]. Cultured meat is estimated to only require several weeks of growth, as opposed to months or years for pork and beef [34,40–42]. The direct use of animal muscle and fat cells in cultured meat might also provide a greater resemblance in taste and nutrition to conventional meat when compared to plant based meats [23,29,43–45]. Moreover, control over cell biology during tissue cultivation, as well as the overall production process, allows for the fine tuning of nutritional properties to improve human health, where muscle and fat cells can be engineered to produce vital nutrients such as anti-oxidative carotenoids that would otherwise not be found (or only at low concentrations) in conventional meat [46]. Taken together, these factors suggest that cultured meat production systems may be able to offer healthier, more efficient, and more environmentally compatible options to traditional animal sourced meats. Furthermore, opportunities to improve food safety at all levels of need also derive from the cultured meat production process.

To date, plant based and cultured meat alternatives have focused on mimicking the muscle component of meat [26,47,48]. However, fat is also a crucial component, contributing to sensory and textural attributes [49]. For example, an increase in fat content improved the juiciness and tenderness ratings of Japanese black steer samples, with maximum evaluation scores attributed to samples containing 36% crude fat [50]. Beef samples with an intramuscular fat content over 10% had significantly higher amounts of lipid-derived flavor volatiles, implying that the adipose content of meat improves flavor as well as texture [51]. The lipid component of meat is also responsible for the complex, undefined, species-specific flavor that is present in meat from different animals, which is not provided by conventional ingredients used in plant based meats or fats. This means that the inclusion of adipocytes may be important for plant based and cultured meats that aim to fully capture the sensory profile of conventional meat [52,53]. For plant based meats, this could mean directly supplementing cultured adipocytes to generate a hybrid plant based meat containing the aforementioned species-specific flavors (e.g., pork flavors). In addition to species specific flavors, the addition of adipocytes to plant meats could generally aid in incorporating an animal “essence”, or general meat specific flavor [52]. Hundreds of volatile compounds comprise the aroma of cooked animal meat, with the majority of them originating from the degradation of lipids upon heating [54,55].

Since fat plays a crucial role in the consumption of animal meat, cultured adipocytes are hypothesized to be key to sensory qualities in cultured and plant based meats. This review contains a guide to the biology and engineering surrounding larger scale adipocyte cell cultures, with consideration for culturing fat for food applications. We provide an evaluation of the cell sources that may be used to produce cultured fat, followed by techniques for proliferating these cells at scale. We also discuss efficient induction of adipogenesis of the cells after large scale proliferation, as well as how cultured adipocytes might ultimately be converted from individual cells into bulk, macroscale fat tissue.

Cell Sources for Scaling Adipocyte Culture

Interest in large scale adipocyte culture has centered on the potential use of human cells in personalized medicine [56]. With the recent emergence of cultured meat products, attention has expanded to include adipocytes from non-human animal sources that can be used to augment cell-based meats. Various cell sources (adipogenic precursor cells) can be utilized for cultured fat, related to proliferative capacity and lipid accumulation. Senescence is an issue that also needs to be considered in the process. Some common cell types used in adipose tissue engineering applications, including pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), can be passaged indefinitely while maintaining some proliferative and adipogenic capacities. Both natural and engineered cells are reviewed here as sources for large scale production of adipose tissue for food. Here, we designate dedifferentiated fat (DFAT), PSCs, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), adipose derived stem cells (ADSCs), fibroadipogenic progenitors (FAPs), and preadipocytes as non-engineered cells and highlight their potential as cell sources for large scale adipocyte generation. In the following section, we discuss cells, such as MSCs, that eventually senesce and potentially lose adipogenic capacity. However, primary cells, including MSCs, ADSCs, and preadipocytes (i.e., stromal vascular fraction-isolated cells) often show improved lipid accumulation and differentiation potential compared to most PSCs. We focus on some of the most promising livestock PSC sources and discuss future steps to improve their proliferative and adipogenic capacities. These cells are generally free from genetic manipulation or mutagenesis, but they can also be bioengineered to increase proliferative capacity or prevent senescence (i.e., immortalization) [57]. Bioengineered cells, including induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), transdifferentiated cells, and genetically engineered cells are also considered as potential sources for food outcomes. In this analysis we include non-livestock species that may not be directly applicable to large scale adipocyte culture for food, however that their inclusion remains relevant as a guide for researchers. Non-livestock cells provide validated models that are important tools in developing new approaches relevant for cultured meat and fat. For example, readers may refer to adipogenic genes targeted in murine studies to enhance their own work with livestock adipocytes. Though not typically considered livestock, murine cells ultimately may find use as food for cats, with at least one group currently working to scale up mouse cell production for pet food [58]. A summary of non-engineered cells reviewed in this section is provided in Table 1, while engineered cells are summarized in Table 2.

Table 1.

Summary of non-engineered cell sources for large scale adipose production.

| Cell Type | Species | Main outcome(s) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DFAT | Porcine | Cells expressed stemness markers CD34, Sca1, CD90, and CD45; cells also expressed mature adipocyte markers Oct3/4, Sox2, c-Myc, and Klf4 | [63] |

| Porcine | Cells remained viable over at least 37 passages | [69] | |

| Porcine | Cells viable over 60 days in culture; expressed adipocyte genes PPARγ, aP2, LPL, and adiponectin | [70] | |

| Bovine | Improved cell growth in plates versus flasks; Wagyu-IM DFAT cells used | [73] | |

| Bovine | Improved adipogenesis with appropriate media formulation, but adipogenesis not as efficient as with porcine cells | [71] | |

| Avian (Chicken) | Incorporation of differential plating techniques (two hour “pre-plate”) helped improve intramuscular chicken DFAT purity | [95] | |

| MSCs/ADSCs/Preadipocytes | Porcine | ADSCs successfully isolated, cultured over 28 passages; positively expressed the stem cell surface markers CD29, CD44, CD71, CD73, CD90, CD105, and CD166, as well as vimentin | [86] |

| Porcine | Bone marrow MSCs experienced decreased proliferation at later passages (>P15), but also exhibited increased adipogenesis | [87] | |

| Porcine | Clonal pig intramuscular preadipocytes were cultured up to 35 passages | [88] | |

| Bovine, Buffalo | Bovine and Buffalo ASCs lasted 15 and 25 passages in culture respectively. | [89] | |

| Bovine | Cells successfully isolated, cultured over 25 passages; expressed high levels of β-integrin, CD44, and CD73 | [90] | |

| Bovine | Clonal cow intramuscular preadipocytes were cultured for over 60 passages | [103] | |

| Bovine | Adipogenic differentiation was effective when media was supplemented with insulin, dexamethasone, isobutylmethylxanthine, octanoate, and 2% Intralipid | [115] | |

| Bovine | MSCs experienced the highest degree of lipid accumulation in serum free media supplemented with ascorbic acid | [92] | |

| Bovine | Bovine preadipocytes co-cultured with mature adipocytes resulted in improved adipogenesis | [93] | |

| Bovine | Isolation methods for bovine preadipocytes exist; additional methods are necessary for future applications | [82] | |

| Avian (Chicken) | ADSCs successfully isolated, cultured over 37 passages; cells expressed CD29, CD31, CD44, CD71 and CD73 | [116] | |

| Avian (Chicken) | Cells isolated from the stromal vascular fraction of excised adipose tissue readily accumulated lipid when treated with adipogenic culture media | [95] | |

| Avian (Duck) | Preadipocytes isolated from different duck breeds exhibited varying rates of lipid accumulation | [96] | |

| Murine | GSH and melatonin prevent senescence, maintain differentiation potential of cells over at least 9 passages | [104] | |

| Human | 3D aggregate culture improved adipogenesis compared to suspension culture; some proliferative capacity maintained | [117] | |

| Human | Immortalization may not be necessary to maintain proliferation and achieve large scale production of certain ADSCs | [118] | |

| Human | ADSCs successfully expanded in animal serum-free media | [119] | |

| Human | Cells expressed CD34 and CD90; large scale in vitro adipogenesis demonstrated; cells secreted adipogenic ECM after 60 days in culture | [85] | |

| Human | Osteogenic genes (RUNX2, SP7, ATF4, BGLAP) more likely to be expressed in DFAT than ADSCs | [120] | |

| Human | Preadipocytes have good adipogenic potential; potential varies based on harvest area | [121] | |

| PSCs | Porcine | Using culture medium containing FGF2 and LIF, and inhibitors of MAPK14, MAPK8, TGFB1, MAP2K1, GSK3A and BMP results in lentiviral-reprogrammed PSCs becoming naïve-state stem cells; cells were viable >45 passages, expressed pPOU5F1 and pSOX2 | [112] |

| Porcine | Transgene insertion-free generation of porcine iPSCs | [122] | |

| Porcine | Serum-free derivation and propagation of pig ESCs | [123] | |

| Bovine | The first report of successful bovine ESC generation and propagation | [124] | |

| Bovine | Feeder free bovine ESCs via replacement using Matrigel or recombinant vitronectin | [110] | |

| Avian (Chicken) | Long term in vitro ESC proliferation (>25 passages) with supporting DF-1 chicken fibroblast feeder cells | [125] | |

| Human | PPARγ2 transfection greatly improved the adipogenic differentiation of iPSCs and ESCs. Cells were first differentiated to MSCs and then to adipocytes | [113] |

Table 2.

Engineered cell sources for large scale adipose production.

| Cell Type | Species | Main outcome(s) | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immortalized cells with adipogenic capacity | Avian (chicken) preadipocytes | Expression of telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) and/or telomerase RNA enable >100 doublings of preadipocytes, while maintaining adipogenicity. | [126] |

| Murine preadipocytes | Conditional expression of the SV40 T antigen imparts immortality during proliferation, and cessation of SV40 expression allows adipogenic differentiation. | [127] | |

| Human preadipoctyes | Combined expression of TERT with the papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein immortalized preadipocytes while maintaining adipogenicity. | [153] | |

| Avian (chicken) fibroblasts | Adipogenesis with treatment with fatty acids and insulin or all-trans retinoic acid. | [128] | |

| Porcine fibroblasts | Immortalized fibroblasts from peripheral blood. Adipogenesis in media supplemented with dexamethasone, 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine, indomethacin, and insulin. | [129] | |

| Bovine fibroblasts | Immortalized bovine embryonic fibroblasts. Ectopic expression of PPARγ2 induces adipogenesis in adipogenic media. | [130] | |

| Murine fibroblasts | Adipogenesis with increased serum concentration in the media. | [133] | |

| Reprogrammed cells from food-relevant species* | Porcine iPSCs | Doxycycline-inducible expression of human Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc, Nanog and Lin28 in primary ear fibroblasts result in reprogramming and the ability to differentiate into all three germ layers. At time of publication (2009) showed stability over 41 passages. | [154] |

| Bovine iPSCs | Retroviral insertion of bovine Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, c-Myc, Lin28, and NANOG into embryonic fibroblasts resulted in the ability to differentiate into all three germ layers. At time of publication (2011) showed stability over 16 passages. | [155] | |

| Leporine (Rabbit) | Lentiviral insertion of human Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc into liver cells resulted in the ability to differentiate into all three germ layers. At the time of publication (2010) showed stability over 50 passages. | [156] | |

| Ovine | Lentiviral insertion of doxycycline-inducible mouse Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc into fetal fibroblasts resulted in the ability to differentiate into all three germ layers, though this capacity was unstable over more than two passages. | [157] | |

| Avian (Chicken) | Lentiviral insertion of mammalian Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc into embryonic fibroblasts resulted in the ability to differentiate into all three germ layers. At the time of publication (2013), showed stability over 20 passages. | [158] | |

| Piscine (Zebrafish) | Lentiviral insertion of mammalian Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc into embryonic fibroblasts resulted in the ability to differentiate into all three germ layers. Stability over >5 passages was not described. | [158] |

First publication of iPSCs from these species listed here. For more in-depth review, the reader is referred to [159].

Non-Engineered Cells (Primary Cells)

Dedifferentiated fat (DFAT) cells

DFAT cells have emerged as a cell source for engineered fat applications [59–61]. DFAT cells are derived from lipid-containing (mature) adipocytes, which possess the ability to symmetrically or asymmetrically proliferate, replicate, and redifferentiate or transdifferentiate. Though adipocytes were previously thought to be terminally differentiated, their ability to proliferate into large numbers of daughter cells was initially documented using cells from the anterior abdominal walls of human infants and children [62]. The origins and characteristics of DFAT cells have been reviewed elsewhere [59], and more recent studies have elucidated some of the mechanisms by which DFAT cells maintain both proliferation and differentiation capacities [63]. Briefly, DFAT cells are distinguishable from other adipocytes via the expression of the stem cell markers cluster of differentiation (CD)34, Stem cells antigen (Sca)1, CD90, and CD45, as well as octamer binding transcription factor (Oct)3/4, sex-determining region y-box 2 (Sox2), myc proto-oncogene (c-Myc), and Krüppel-like factor 4 (Klf4). Under specific culture conditions, DFAT cells are multipotent; forming adipocytes, chondrocytes [64], osteoblasts [65], skeletal myocytes [66], cardiomyocytes [67], and smooth muscle cells [68].

Porcine DFAT cells maintain proliferation and adipogenicity over at least 37 passages [69]. DFAT cells accumulated more lipid than stromal vascular-isolated preadipocytes, MSCs, and ADSCs, highlighting their enhanced potential for use in large scale cultured fat production [69]. Porcine DFAT cells also grew and accumulated lipids over 60 days in culture, and consistently expressed adipocyte genes peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), adipocyte protein 2 (aP2), lipoprotein lipase (LPL), and adiponectin [70]. Additionally, these cells maintained the capacity for myogenic differentiation when the culture medium was changed to include galectin-1. Interestingly, flow cytometric analysis showed that the porcine DFAT cells displayed similar cell-surface antigen profiles to MSCs, including markers CD44, CD29, and CD90, suggesting that DFAT cells maintain their high proliferative capacity during long-term culture at least in part by reverting to a stem-like state. The mechanisms by which this reversion takes place are yet to be elucidated, but improving understanding of these cellular processes will be a key factor in scaling up the cell-based production of adipose tissue. Overall, DFAT cells are promising for large scale engineered fat production in terms of both proliferative capacity and adipogenic potential.

Bovine DFAT cells have also been explored as a potential cell source for engineered adipose tissue. Bovine DFAT cells were not as adipogenic or proliferative as porcine cells, possibly due to the culture parameters evaluated [71]. Prior work has optimized and improved adipogenesis conditions for human, murine, and porcine cells, which share commonalities in terms of their biology. There remains a need to develop culture parameters for adipogenesis from bovine cells, and some recent work has focused on addressing this gap. Wagyu-intramuscular fat (IMF) DFAT cells cultured in flat plates versus flasks enabled more facile removal of contaminating cell types, allowing more subpopulations of cells to be adipogenic compared to cells cultured in standard tissue culture flasks [71]. Recent work highlighted new techniques for robust lipid accumulation in bovine DFAT cells through the use of low fetal bovine serum (FBS) media during adipogenic differentiation [72]. Despite the limitations compared to porcine DFAT cells, bovine DFAT cells can be returned to a proliferative state, and recent work has demonstrated simple and optimized culture conditions for improving this process [73]. Taken together, existing work illustrates that improved culture conditions and media formulations should improve the proliferative and adipogenic capacity of bovine DFAT cells to improve yields of both proliferative and differentiating DFAT for scaling adipocyte generation.

Mesenchymal Stem cells (MSCs), Adipose Derived Stem Cells (ADSCs), Fibroadipogenic Progenitors (FAPs) and Preadipocytes

Other cell sources such as MSCs, ADSCs, FAPs and preadipocytes merit continued investigation with similar proliferative and adipogenic capacity to DFAT cells [74]. MSCs are multipotent cells derived from various tissues such as bone marrow, adipose, cord blood, muscle and neural tissue, while ADSCs specifically refer to MSCs derived from adipose [75–77]. FAPs typically refer to intramuscular MSCs, while sometimes also including the general medley of cells (fibroblasts, endothelial cells) within the interstitial space of skeletal muscle [78–80]. Preadipocytes refer to adipose progenitor cells (derived from any cell type) that are committed to adipogenesis, but are still able to proliferate [81]. In this review, we broadly consider preadipocytes, FAPs and MSCs from all tissues as one group, due to similarities in terms of proliferative ability, culture media requirements and most importantly, their ability to differentiate into adipocytes. ADSCs and general preadipocytes also typically share similar isolation protocols, where adipose tissue is broken down mechanically and enzymatically, then subsequently centrifuged to capture its stromal vascular cell fraction [82–84]. Human ADSCs have been shown to generate a complete adipose tissue in vitro, expressing adiponectin and PPARγ while fibroblasts present in the cell population secreted an extracellular matrix (ECM). After 60 days cultured tissues were positive for type I collagen and fibronectin, eventually becoming comparable with adult human adipose tissue after forming vessels and collagenic fibers during long-term culture (120 days) [85].

Various livestock preadipocytes and MSCs have been reported in the literature, with longevity for in vitro culture typically lasting between at least 15 to 37 passages for pig, cow, buffalo, chicken and duck cells [82,86–96]. The maintenance of adipogenicity throughout an isolated cell population’s lifespan is a separate variable though, with reports of adipogenicity waning before the cessation of proliferation [83,97]. Waning adipogenicity of MSCs in particular has been accompanied by an increase in osteogenic differentiation, which could point to factors such as substrate stiffness influencing MSC differentiation [98–101]. Hard surfaces such as tissue culture flasks, well plates and petri dishes have been shown to promote osteogenesis in MSCs [102]. At the same time, there are concurrent reports of an increase in adipogenicity during extended MSC culture, so the exact changes to cell adipogenicity during long term culture may depend on numerous factors such as the cell type, culture conditions and perhaps even batch-to-batch variation [87].

One solution to cell longevity and adipogenicity may be to generate clonal cell lines from isolated MSCs and preadipocytes, where particularly proliferative and adipogenic cells are selected from the bulk population to screen for the best fat precursor cells. Indeed, the longest lasting MSCs or preadipocytes reported in the literature have undergone clonal selection, with porcine intramuscular preadipocyte clones in one study maintaining proliferative and adipogenic ability for at least 35 passages [88]. For bovine cells, a clonal intramuscular preadipocyte line has been allegedly passaged over 60 times while retaining the ability to adipogenically differentiate [103]. While there is a report of uncloned chicken ADSCs lasting for 37 passages, the study reported a subculture ratio of 1:2, which is much lower than what other groups have published (e.g., ~1:7 for the clonal porcine cells). Despite this, it is likely true that the variability in in vitro cell proliferation observed across the range of reported passage numbers could reflect how protocol optimization could play a role in maximizing the longevity of cultured MSCs and preadipocytes. For example, switching from a standard DMEM+10% FBS culture media to a custom formulation (with 5% FBS) extended the proliferation of porcine ADSCs from 34.8 population doublings to 54.9, with no signs of stopping at the end of the 110-day experiment [97]. The addition of glutathione (GSH) and melatonin as antioxidants during ADSC cell culture has also been shown to combat cell senescence while preserving stemness and multidirectional differentiation potential [104]. Recently characterized transcriptional profiles and single cell RNA-seq data may also offer clues for maintaining the proliferative and adipogenic potential of ADSCs [105]. Ultimately, combining multiple approaches for improved MSC and preadipocyte growth (clonal selection, culture media optimization, substrate stiffness) might yield the most favorable results, giving rise to MSCs and preadipocytes that maintain high levels of proliferative capacity and adipogenicity over extended in vitro culture.

Pluripotent Stem Cells (PSCs)

Mouse embryonic stem cells are considered the “original” PSC, and have helped illuminate many of the conditions favorable to adipogenesis [56]. While their role in deciphering potential adipogenic mechanisms has been invaluable, mouse cells are largely not appropriate for uses in regenerative medicine and cultured meat. Instead, several livestock sources of ESCs have been developed in the last decade, and are reviewed comprehensively elsewhere [106].

Promising recent work has demonstrated that bovine stem cell generation is becoming more feasible at larger scales [106–108]. Bovine pluripotent stem cells hold the potential to substantially advance cultured meat by providing a livestock source of cells that can be differentiated into all the necessary components of meat (muscle and fat). Bovine expanded potential stem cells (bEPSCs) were recently established from preimplantation embryos of both wild-type and somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) bovine embryos [109]. bEPSCs expressed high levels of pluripotency genes and were able to differentiate towards adipogenic lineages in vitro, and cells remained viable in their undifferentiated state for at least 50 passages [109]. Additionally, stable bovine embryonic stem cells (bESCs) were recently reported [110]. Combined with recent advances in simplified, effective, culture conditions that no longer rely on mouse embryonic fibroblast feeder cells, bESCs may soon be a reliable cell source for cultured adipose production. Recently, bESC lines were cultured and derived using a base medium consisting of commercially available supplements and only 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) [110]. The newly derived bESC lines were easy to establish, simple to propagate and stable after long-term culture. Additionally, the bESCs expressed pluripotency markers and remained viable for over 35 passages. bESCs maintained normal karyotype and the ability to differentiate into all 3 germ lineages, suggesting they can be used for adipocyte generation. In addition to media and culture conditions, recently developed differentiation methods, such as forward programming in established livestock PSCs to guide differentiation, can also be integrated into bovine and porcine approaches to establish cell lines for generation of adipose tissue [107]. As more bovine stem cell lines are established, novel methodologies will be adopted and refined to generate cell lines useful for cultured meat.

Porcine stem cells are another promising cell source for cultured meat applications. Though much research has focused on the potential uses of porcine DFAT cells for cultured adipose tissue, several studies have attempted to generate and characterize porcine PSCs. This is partially due to the high applicability of porcine cell and tissue models in human medicine, as well as the constant search for improved gamete generation and breeding schemes of farmed animals [111]. One study found that using culture medium containing basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), inhibitors of mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK)14, MAPK8, transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ)1, MAP2K1, glycogen synthase kinase (GSK)3A and bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), lentiviral-reprogrammed porcine PSCs were transformed into naïve-state stem cells [112]. The cells were viable for over 45 passages and expressed the pluripotency-related endogenous genes pPOU5F1 and pSOX2. RNA-sequencing (RNAseq) data suggested that the key mechanism was blocking TGFβ1 and BMP signaling. Many compounds can block these pathways, making this finding an important future direction to explore in the generation of adipocytes for cultured fat. It is worth noting that a significant limitation of PSCs is that the cells must be first be differentiated into MSCs, and then adipogenically differentiated into fat [113]. These complex processes take time and result in some off-target effects, such as osteogenic or chondrogenic differentiation [114]. Direct conversion of PSCs to adipocytes or to readily accumulate lipid (i.e., become adipocyte-like cells), would make this process a more viable option. Despite this concern, PSCs remain a promising cell source for large scale cultured fat production.

Conclusions

Ultimately, highly proliferative and adipogenic cells are crucial for large scale cultured fat production. Studies highlighted in this section demonstrate that there are cells capable of proliferating for dozens of passages while remaining adipogenic. Of the various cell types listed, it appears that DFAT cells may be the most promising due to strong adipogenic capacity coupled with the ability to remain proliferative over extended in vitro culture. Clonal MSC-type cells are another good option, and selecting for promising clones from a bulk population of isolated cells brings their proliferative and adipogenic capacity close to that of DFAT cells. It is important to note that strategies such as clonal selection are also applicable and potentially beneficial to DFAT cells [72]. DFAT cells and MSC-type cells are also abundantly available in adipose tissue, minimizing primary cell isolation requirements. While PSCs are known to be very proliferative, their path to adipogenic differentiation is less characterized and more difficult. One limitation in the field is that most cell lines presented here have been characterized in “proof of concept” studies, with few cells proliferated and adipogenically differentiated at scale. While industrial and commercial proliferation of cells for cultured fat can rely on scaling frameworks established for other cells, as the demand for large scale adipose tissue engineering increases, novel approaches will be needed for generating sufficient cell biomass for cultured fat and meat.

Engineered cells for robust expansion and adipogenesis

Along with primary or native cell populations, engineered and adapted cell lines offer significant opportunities for scaling cultured fat production. For instance, immortalized somatic cell lines offer advantages in terms of proliferative capacity and control over cell fate and could therefore improve the dependability and scalability of cultured fat production. Precedent exists for this in food-relevant species, such as chicken, where primary preadipocytes have been immortalized through overexpression of Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase (TERT) alone or in concert with telomerase RNA (TR) to generate immortalized chicken preadipocytes (ICP1) [126]. This work showed that ectopic TERT alone could overcome the population doubling limits of primary preadipocytes, and that co-expression with TR could drastically improve proliferation rates (a ~30% rate increase compared to TERT alone). These preadipocytes maintained adipogenic potential and underwent robust lipid accumulation following long-term expansion. Alternatively, genetic immortalization of murine preadipocytes has been achieved through the conditional expression of the simian virus 40 (SV40) T-antigen during proliferation [127]. Application of these systems to various livestock species could offer promising options for cultured fat production. In addition to immortalized preadipocytes, the immortalization of alternate cell types with subsequent induction of adipogenesis could offer scalable solutions for cultured fat. For instance, adipogenesis in immortalized DF-1 chicken fibroblasts was demonstrated by treatment with fatty acids, insulin, and retinoic acid [128]. Immortalization of bovine and porcine fibroblasts was demonstrated with overexpression of TERT, cyclin-dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) and cyclin D1 [129,130]. Taken together, these results indicate that the immortalization of numerous cell types could help provide scalable solutions for cultured fat production.

In addition to engineering cells to generate immortalized somatic cell lines, spontaneous immortalization of cells can be pursued through routine subculturing or treatment with mutagenic agents such as radiation or chemical mutagens [131]. Under these conditions, some percentage of random mutations will induce an escape from cellular senescence, thereby immortalizing the cells. Indeed, spontaneous immortalization through subculture was the method through which the DF-1 chicken fibroblast cell line was established, as well as the commonly-used mammalian adipogenic fibroblast line—murine 3T3-L1’s [132,133]. While these spontaneously generated cell lines may not be considered engineered, per se, neither are they unaltered, due to the selection for cells that have undergone specific mutations. However, it is possible that spontaneous immortalization could offer regulatory advantages compared with genetically engineered cells, particularly in jurisdictions that disallow any genetic engineering in food production [134]. Similarly, various methods for transiently inhibiting cellular senescence could offer non-genetically modified organism (GMO) opportunities for “immortalizing” cells. For instance, human fibroblasts treated with mRNA encoding TERT showed a 1012-fold increase in total cell number compared with untreated cells, without requiring modifications to the genome [135]. Such transient genetic strategies could overcome regulatory issues facing GMOs, while offering the bioprocess benefits of genetically immortalized cells. Other non-genetic methods can be explored as well. For instance, small molecule inhibition of the PAPD5 polymerase—which halts endogenous TERT activity by triggering degradation of the telomerase RNA component—can recover TERT activity in stem cells, extending proliferative capacity [136]. Additionally, antioxidant treatment has been shown to reduce senescence in adipose-derived stem cells while maintaining adipogenic potential [104].

Along with immortalizing somatic cells, adult cells can be reprogrammed to a stem cell state by the overexpression of Yamanaka factors (Oct3/4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc), which are naturally expressed in high levels in embryonic stem cells [137]. These cells—called induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)—are capable of indefinite expansion and differentiation into a range of cell types, including lipid accumulating adipocytes [138]. iPSCs offer a range of potential advantages for cultured fat production: They are capable of expansion in suspension bioreactors with rapid growth rates (~20 hour doubling times for porcine iPSCs in suspension culture) [139]; they can be obtained through entirely non-invasive means, such as via keratinocytes from hair follicles [140]; they can be generated through transient mRNA delivery, thus potentially avoiding regulatory hurdles facing fully engineered GMOs [141]; and they have been successfully generated for many livestock species, including pigs, cattle, chicken, sheep, and goats, as reviewed extensively by others [106,142–145]. Despite these advantages, iPSCs offer their own challenges for cultured fat production. For instance, unless produced through transient mRNA methods—and potentially even still—iPSCs could face regulatory hurdles as genetically controlled cells, as the specific regulatory status of transgenic, gene-edited, and transiently altered cells for cultured meat is yet to be determined. Additionally, iPSCs often require challenging or complex differentiation processes. For instance, differentiation into lipid accumulating adipocytes can be less robust in iPSCs than ADSCs, and often involves a transition through an MSC state, which can complicate the differentiation process [113,138]. Lastly, iPSC generation from livestock species have to-date offered some unique challenges compared with human or murine iPSCs, such as requiring additional genes (e.g., TERT) to be expressed or relying on continued Yamanaka factor expression, potentially indicating incomplete reprogramming [142,144,146,147]. Despite these challenges, the stated advantages of iPSCs warrant extensive exploration of their use for cultured fat and could allow for highly scalable production systems.

Lastly, along with engineering efforts that are directly related to the immortalization or reprogramming of cells, genetic strategies can be used to engineer cell lines towards optimal properties for large scale fat production. For instance, engineering the previously mentioned immortalized chicken preadipocyte (ICP1) cells to overexpress BMP4 increased cell proliferation, which could improve process dynamics and economics [148]. Additionally, ICP1 cells engineered to overexpress perilipin 1 (PLIN1) or retinoid X receptor α (RXRα) showed improved lipid accumulation and adipogenic differentiation [149,150]. In both iPSCs and fibroblasts, overexpression of PPARγ can be used to improve adipogenic differentiation and lipid accumulation [113,151]. In fibroblasts, commensurate overexpression of the CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein alpha (CEBPα) can further improve adipogenesis [151,152]. Taken together, these results demonstrate how immortalization or reprogramming and subsequent genetic engineering strategies can generate cell lines that are capable of both robust proliferation and differentiation to enable the large scale production of high-quality cultured fat. A summary of engineered cell sources for large scale adipose production is provided in Table 2.

In all these possible cell engineering efforts, consumer and regulatory considerations play an important role in affecting the eventual application of permanently or transiently engineered cells. This could be particularly true for the above approaches, as the development of high-tech foods—which genetically modified cultured meat would certainly be categorized as—can be met with skepticism from consumers [160]. Ultimately, further research is required to determine the impact that such genetic strategies would have on consumer acceptance. From a regulatory standpoint, the impact of cell engineering will likely vary significantly by country. In the United States, two genetically modified animals have to-date been approved for human consumption, and therefore point towards a potential path for regulatory approval of genetically engineered cultured meat products [161,162].

Large scale Cell Proliferation Techniques for Cultured Fat

After an appropriate adipogenic cell source is selected, methods of proliferating the cells to produce sufficient biomass for food applications will be required. Many scalable cell production systems exist from the biotechnology and pharmaceutical spaces and should be applicable to cultured fat cell production for food purposes. However, there may be unique challenges associated with adipocyte culture due to cell buoyancy during lipid accumulation as well as costs associated with process controls and growth factors. Scalable cell proliferation techniques are grouped here into two approaches: Suspension and adherent culture-based strategies.

Suspension Culture

One promising avenue for large scale adipose culture is via suspension culture. Suspension culture is the process of growing single cells or cell aggregates in growth medium with agitation, allowing for proliferation without attachment to a culture flask. Adaptation of adherent cells to suspension culture has been widely explored in the literature, and prior to inoculation in a suspension system cells are generally adapted to serum-free medium [163,164]. Although adherent culture can achieve high cell density (discussed further below), suspension culture is widely used in various biotechnology applications and large scale infrastructure already exists that could be easily transferred to fat-relevant cell types [165–167]. Suspension culture is also favored for scale-up compared with adherent culture because cell growth is limited by cell concentration (or aggregate size) as opposed to surface area. Furthermore, suspension cultures are less labor-intensive, provide a more homogenous culture environment, and require fewer resources (culture flasks, enzymes to passage adherent cultures, et cetera.) [168].

Suspension bioreactor types

Many different bioreactor types have been explored to facilitate suspension cell culture (Figure 1A). The most common suspension bioreactor is a stirred suspension bioreactor (SSB), comprised of a cylindrical culture vessel and mechanism to stir the media to prevent excessive cell aggregation [169]. SSBs are typically characterized by the media replenishment mechanism involved in the process: batch (no replenishment, proliferation until cell harvest), fed-batch (media replacement in batches), or continuous (constant media replacement). Other relevant suspension bioreactors are wave (disposable flexible systems on an undulating surface to gently mix), shake-flask (flasks that are agitated on shaking incubators), and airlift (gas is injected from the bottom of the culture vessel) [170–172]. Cell types relevant to fat culture have been grown in SSBs (bovine ADSCs, avian fibroblasts, porcine iPSCs) and wave bioreactors (avian fibroblasts) [139,169,173]. Computational fluid dynamic models suggest that airlift bioreactors may be the most realistic and efficient production method for large scale cultured meat production (although specific cell types/species were not directly modeled) [174]. While these studies present promising evidence for the production of cultured fat-relevant cell types in suspension, future work will be necessary to optimize bioreactor type, as well as media and culture conditions to ensure efficient, cost-effective, fat culture scale-up depending on the cell type used. Despite the limited literature on livestock adipose suspension culture, a large volume of work has been published using suspension culture to scale-up human and rodent fat-relevant cell types and can serve as a base for the generation of large scale fat production for food applications. Human MSCs, ESCs, and iPSCs have been expanded in SSBs and maintain proliferative potential [175–179]. Notably, human iPSCs and ADSCs retained their ability to differentiate while still in suspension. This could be a promising route to large scale fat production where livestock stem cells are expanded in suspension and adipogenic differentiation is induced after sufficient cell mass has been produced [180]. 3D adipose spheroids generated using preadipocytes and hADSCs in suspension using low attachment tissue culture plates show increased differentiation efficiency and more accurately represent the 3D microenvironment [180,181]. One potential explanation for this is that cell shape has been shown to regulate stem cell fate, and cells that are allowed to remain circular (such as in suspension as opposed to flattening during adherent culture) will favor adipogenesis over osteogenesis [182].

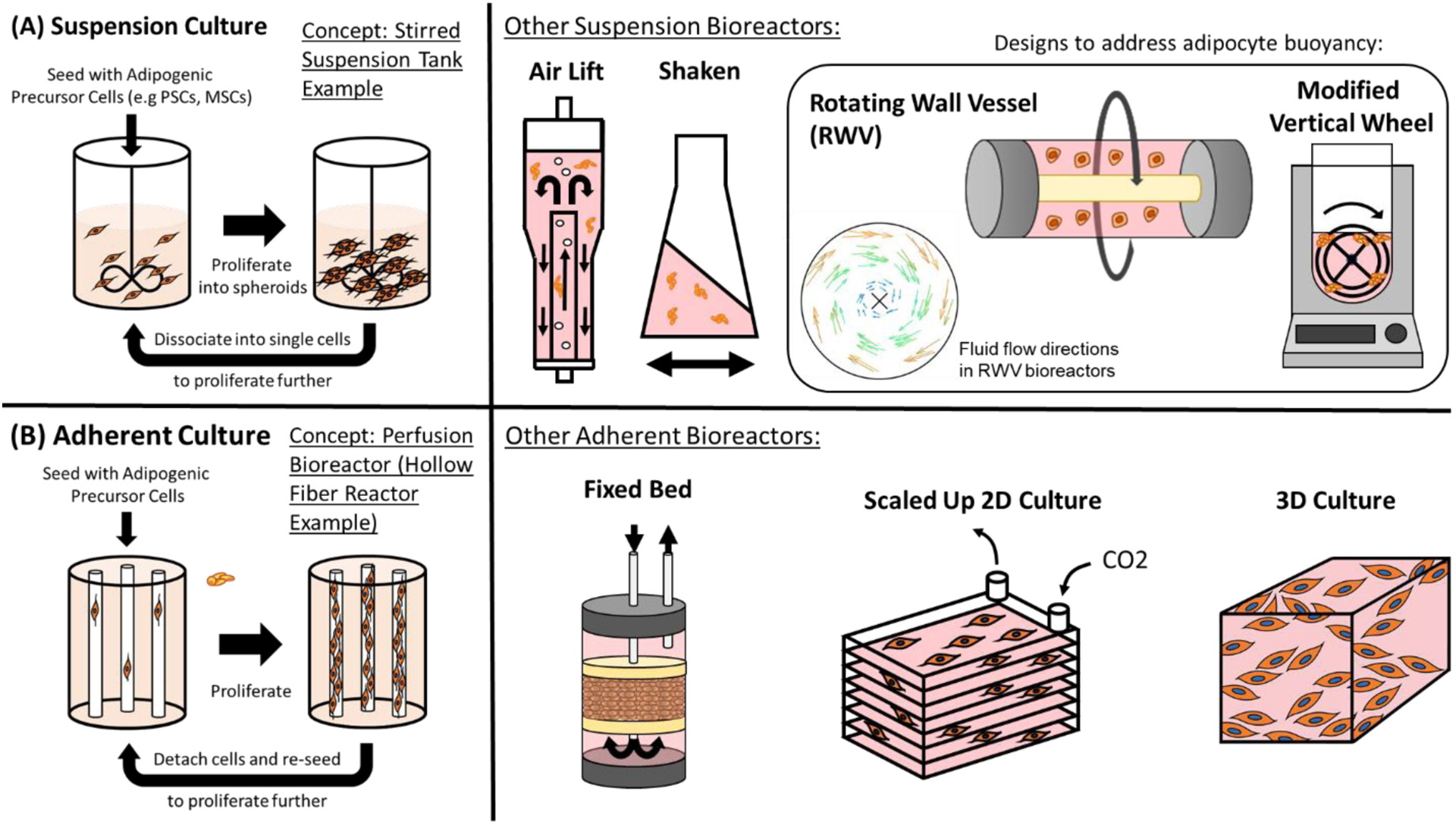

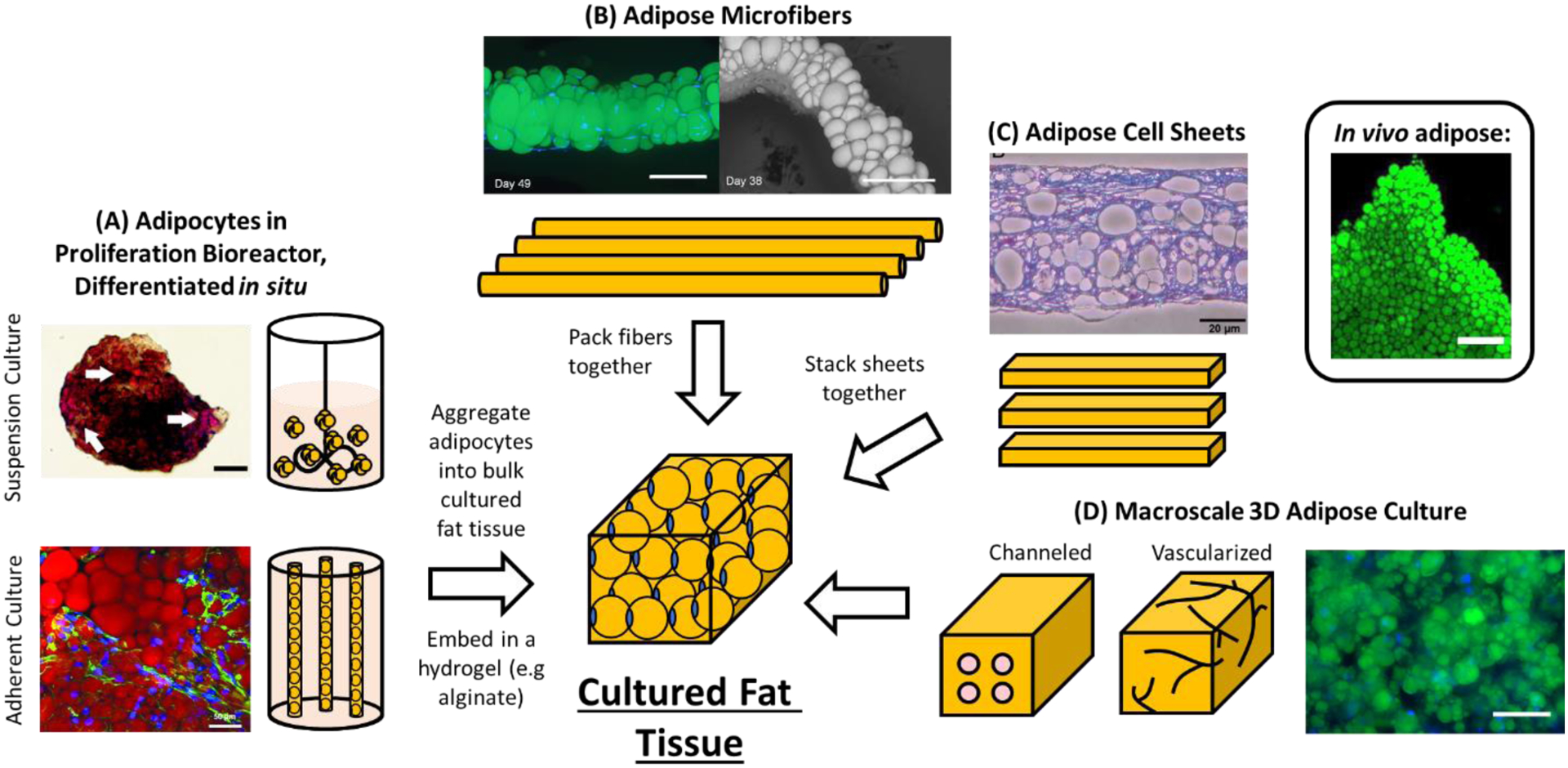

Figure 1.

Overview of (A) suspension and (B) adherent culture-based bioreactors for the large scale proliferation of adipogenic precursor cells in order to obtain large numbers of cells for the downstream generation of adipocytes. The fluid velocity tracking diagram (short arrows) for rotating wall vessel bioreactors is reproduced from [197].

Many cell types self-organize into aggregates that proliferate, retain differentiation potential, and more accurately recapitulate a natural 3D environment than single cell suspensions [177]. Culturing cell aggregates in suspension eliminates the complexity of designing edible microcarriers (or removing inedible materials at the end of cell culture), while producing higher cell numbers versus microcarriers since the entire aggregate is comprised of cells. Cell aggregate-based suspension culture can theoretically be applied to many different cell types (iPSCs, MSCs, hADSCs, preadipocytes, etc.) [176,180,181,183]. One important consideration in the suspension culture of aggregates is the formation of a necrotic core when cell density and aggregate size exceeds the limit where nutrients can reach the central cells [184]. While this is essential to consider when designing systems, engineering controls can be enacted to either harvest or passage spheroids into single cell suspensions before they become necrotic. Unfortunately, when considering scaling-up cultured fat production, increased passaging may result in increased process complexity and would likely have to be optimized for specific cell types used. The necrotic core challenge could also be addressed by co-culturing fat-relevant cell types with endothelial cells to transport nutrients throughout the aggregate [185]. For example, a previous study generated vascularized human subcutaneous white adipose tissue spheroids that retained the ability to differentiate into unilocular adipocytes [186].

Overcoming Adipocyte Buoyancy in Suspension

While aggregate cell culture could be a promising route for simple and efficient fat scale-up, the inherent nature of lipid-producing cells will likely present unique challenges. As lipid accumulation increases, cells become buoyant and float to the surface of culture systems. This interferes with nutrient/oxygen flow in the bioreactor and decreases yield [185]. One option would be to simply harvest cells once they become buoyant and allow proliferation of non-lipid loaded cells to continue below, thus allowing for “self-selection” of differentiated fat cells on the culture surface. Another option is to incorporate methods that allow continued culture of buoyant adipocytes in suspension. For example, it may be necessary to use dense microcarriers to counteract adipocyte buoyancy, although this would lower yield compared to cell aggregate-based systems as mentioned.

Perhaps the most promising avenue to overcome buoyancy issues would be to adopt specialty suspension bioreactors for fat accumulation. Rotating wall vessel bioreactors (RWVBs) initially developed by NASA to simulate a microgravity environment produce rotational forces that draw cells towards the center of the bioreactor chamber, and may thus work for cells that sink downwards and float upwards (see “Rotating Wall Vessel” in Figure 1A) [187]. RWVBs comprise a rotating cylindrical culture vessel surrounded by a membrane to allow oxygenation are favored for cell types that are sensitive to shear stress [188,189]. In contrast to SSBs, RWVBs do not require an internal mixing device and instead are completely filled with culture medium, while cells and nutrients are mixed by gentle rotation of the entire vessel. Two types of RWVBs exist: High Aspect Ratio Vessels (HARV, developed by NASA to stimulate a microgravity environment) and Slow-Turning Lateral Vessels (STLVs) [190]. HARV bioreactors have been used to culture lipid-containing 3T3-L1 aggregates and lead to increased adipogenesis in MSCs [191,192]. Hollow fiber membranes can also be added to RWVBs to enhance efficiency/cell health [193]. Alternatively, a system designed to draw floating adipose cells back into the media (e.g., a modified Vertical Wheel Bioreactor) could enable efficient culture of buoyant cells [183,194]. Another potentially relevant bioreactor type is the random positioning machine (RPM) bioreactor, which rotates a culture vessel over multiple axes to ultimately create a microgravity environment. RPMs require a large footprint relative to RWVBs however, and may be more difficult to scale up [195,196].

Adherent Culture

Using adherent cell culture strategies is another approach towards upscaling adipocyte cultures (Figure 1B). While suspension culture offers some advantages by foregoing the need to fabricate and utilize scaffolds, there are potential advantages to scaling the growth of adipocytes using adherent cell culture strategies. Given that ADSCs and adipocytes are sensitive to mechanical cues, one major advantage of utilizing adherent culture strategies is the potential to increase culture efficiency by stimulating cells using mechanical cues. For example, adult ADSCs undergo adipogenesis by simply tuning the substrate stiffness to physiologically relevant levels of adipose tissue (~2 kPa) [198]. In addition, adipocytes differentiated on more compliant substrates exhibited higher levels of lipid accumulation when compared to fat cells grown on less deformable substrates [199]. There is also potential to utilize cell adherence onto substrates to apply mechanical cues to stimulate adipogenesis in stem cells. Thus, the use of adherent cell culture strategies would allow for the tuning of mechanical environments, which could be harnessed to improve the growth of adipocyte precursors and lipid accumulation of differentiated adipocytes.

Additionally, while the occurrence of cell buoyancy upon adipocyte differentiation presents challenges during suspension culture upscale, one benefit of growing adipocytes in adherent bioreactors would be to prevent this occurrence by either having cells attached to an immobile 2D surface. Culture surfaces could be treated further to maintain cell attachment, for example with the use of elastin-like peptides [200]. On the other hand, cell buoyancy could be harnessed as a potential advantage in both suspension culture and adherent culture to improve the efficiency of cell harvesting by selecting for differentiated adipocytes which lift off, thus freeing up surface area for proliferating cells.

Next, we will discuss current technological approaches towards upscaling adherent cell cultures with specific examples highlighted towards progress with adipocyte-relevant cell types. For a more extensive review on general approaches towards upscaling adherent cell cultures, we refer the reader to a recent review [201].

Adherent Bioreactor Types

Given that cell culture techniques are best characterized and established in 2D, one approach is to iterate and improve upon the efficiency of conventional 2D culture techniques for adipocyte culture upscale. For example, 2D multilayered flasks offer a scale up approach for the growth of adherent cells. While the use of multilayered flasks is not feasible with static media at a larger scale, one study found that the incorporation of active gas ventilation resulted in >95% cell viability of hiPSCs cultured within 10 layers with a total surface area of 6320 cm2 [202]. Additionally, a 44% increase in cell proliferation of hiPSCs was observed when compared to cells grown in static media [202]. Using the same culture system, gas transport could be further enhanced with oxygen-permeable layers, similar to culture vessels which are commercially available such as Corning®’s HYPERflask or HYPERstack. While there are some improvements towards upscaling 2D culture methods, the approach remains limiting for upscale and additional innovations would be necessary to make 2D culturing a viable approach. Specifically, it will be important to address the technical challenge of increasing the amount of surface area for cell attachment while achieving proper nutrient and oxygen mixing as culture vessels increase in volume.

The utilization of microcarriers offers the advantages of adherent cell culture techniques with the benefit of growing cells in suspension to increase scalability, providing a promising approach towards upscaling adipocyte cell culture [203]. Microcarrier beads are widely used to increase surface area for adherent cell attachment and to increase yield efficiency in cells that are unable to form spheroids or aggregates in suspension [204]. It is important to note that the generation of microcarrier scaffolds adds an additional processing step which may add to overall production costs. However, if mechanical cues could substitute for expensive growth factors, and similarly stimulate important cell growth and differentiation pathways, the added cost of scaffold fabrication could potentially eliminate other production costs. Additionally, the choice of scaffold material will be important to consider for not only manufacturing costs, but also production logistics and the resulting adipose tissue properties. For example, additional complexities to the cell harvesting process can occur if synthetic carriers are used given that production facilities must separate cells from the carriers. Alternatively, microcarriers could be edible and engineered to match the mechanical properties of adipose tissue to increase cell differentiation efficiency [199]. However, it will be important to consider the effects of integrating scaffolds on the taste, texture, and nutritional profiles of the final adipose tissue product.

Another approach towards upscaling adherent culture of adipocytes is through the use of perfusion bioreactors, where media is passed through adhered cell cultures, such as hollow fiber bioreactors (HFBs). HFBs can be designed to have multiple oxygen and nutrient permeable tubing running in parallel, which provides a substrate for adherent cells to grow on. Using HFBs, researchers have demonstrated its ability to support scalable culture with well-characterized proliferation and differentiation of MSCs, ADSCs, and iPSCs [35,205–208]. Using a similar perfusion approach, fixed-bed bioreactors (FBBs) can be utilized. Here, cells are immobilized within macroporous carriers, packed within a cylindrical bioreactor, and perfused with media. The approach provides a higher surface area to volume ratio, and thus, less cell passaging is required [209,210]. It also provides a low shear stress environment for mammalian cells. Importantly, its ability to support the proliferation of adipocyte precursors, such as MSCs, has been demonstrated at laboratory scale [211]. Further innovations among perfusion-type bioreactors are underway, for example, with the recent development of an interchangeable production line system which incorporates feeder cells for the supplementation of growth factors and allows for adjustments in media circulation flow. Thus, media can flow to deliver essential growth factors to adherent cells and be reversed for other essential processes such as for media recycling. Though the process is currently geared towards muscle cell proliferation, the approach could be tuned towards adipocyte cell culture provided that the feeder cells are producing the appropriate growth factors needed [212].

Although there is strong potential to scale-up adipocyte cultures using scaffold suspensions or perfusion bioreactors, nutrient and oxygen mixing is key and becomes more challenging as these systems are scaled [209]. Additionally, there are concerns over the use of expensive enzymes for cell passaging and harvesting when growing cells under adherent culture conditions. To address this challenge, innovative approaches are being developed which are designed to have cells proliferate and self-detach via cleavable peptides [213]. This approach would allow for additional cells to grow on newly unoccupied substrates as well as increase the ease of cell harvesting, while reducing costs. It is important to note that this approach is not limited to 2D culture and could be applied to 3D culture techniques as well. Lastly, the potential effects on adipocyte precursor proliferation and differentiation when culturing in 2D must be considered given that studies have shown differences in cell behavior and gene expression when compared to 3D cultures [200,214,215]. For example, primary mouse adipocyte exhibit phenotypes similar to those seen in vivo—such as the presence of unilocular lipid droplets—when grown in 3D compared to 2D [216]. Thus, methods for upscaling adipocytes in 3D adherent cultures should be considered.

To replicate 3D environments similar to native adipose tissue, one approach to consider is the encapsulation of adipocytes within hydrogels. Though there has been extensive research regarding hydrogel encapsulation for tissue engineering applications, more recent innovations in biomaterial development have improved culturing efficiency. For example, the culture of cells using the thermoreversible Mebiol Gel which has been shown to support the growth of high cell densities (~20 million cells/mL using hMSCs), provides increased ease in cell harvesting [217]. Importantly, encapsulation of adipocyte precursors within hydrogels would protect cultures from high shear stress in the presence of tank mixing or fluid flow in a perfusion bioreactor.

Another option is the culture of adipocytes within porous scaffolds in a bioreactor [218]. However, similar to cell aggregates in suspension, nutrient and oxygen diffusion limitations exist using a top-down approach in 3D tissue engineering. Diffusion rates are dependent on multiple factors such as scaffold porosity, nutrient molecule size, and media viscosity, which can limit 3D cultures to a range of tissue thickness from ~100 μm − 1 mm when cultured in static media and in the absence of vasculature [219–221]. As a result, there is potential to use a modular, or bottom-up approach in which smaller microtissues can be cultured as building blocks for larger 3D structures [222]. For example, this can be achieved using biodegradable microcarriers which assists in the formation of adipocyte cell aggregates in suspension and does not remain in the final tissue culture product. However, in this scenario, it will be important to use food-grade scaffold materials for cultured meat applications [223]. Another approach towards engineering adherent adipocyte spheroids is through surface chemistry treatments on 2D substrates. For example, the introduction of surface charge induces spheroid formation while surface conjugation with appropriate peptides results in consistent cell attachment to the substrate [200]. Using this approach provides the benefits of growing adipocyte precursors in 3D, while avoiding issues of adipocytes lifting off during differentiation.

Overall, upscaling adipose tissue using adherent culture methods offers potential to overcome current hurdles with adipocyte cell culture such as increasing the efficiency of preadipocyte proliferation and adipocyte differentiation via mechanical stimuli, reducing shear stress on cells, and providing methods towards engineering 3D adipose tissue for structured cuts of meat. However, suspension culture certainly presents advantages towards adipocyte cell culture upscale. For example, foregoing the need to produce scaffolds could significantly reduce production costs. Importantly, the most efficient method will likely vary according to cell type and target product type. Therefore, it will be important to continue research to determine which culture method is most efficient for adipocyte culture upscale according to each cell type and application.

Culture Media Considerations

Since one goal of plant based and cultured meat is to supplement conventional animal agriculture, there is intense effort in developing culture media formulations that do not depend on animal products such as serum from blood. For the cultivation of cultured fat cells, three types of culture media formulations are usually considered (Figure 2A): A proliferation medium that supports and promotes the expansion of adipogenic precursor cells to achieve a desired amount of biomass, followed by an adipogenic induction medium (also called differentiation medium) that initiates adipogenesis within precursor cells. Adipogenic differentiation is typically accompanied by cell cycle arrest, where cell division no longer takes place [224]. Once the adipogenic program has been sufficiently activated, cultured cells are often switched to a pared down lipid accumulation medium (also called maintenance medium) containing fewer adipogenic compounds at concentrations sufficient to maintain adipogenic gene expression [225].

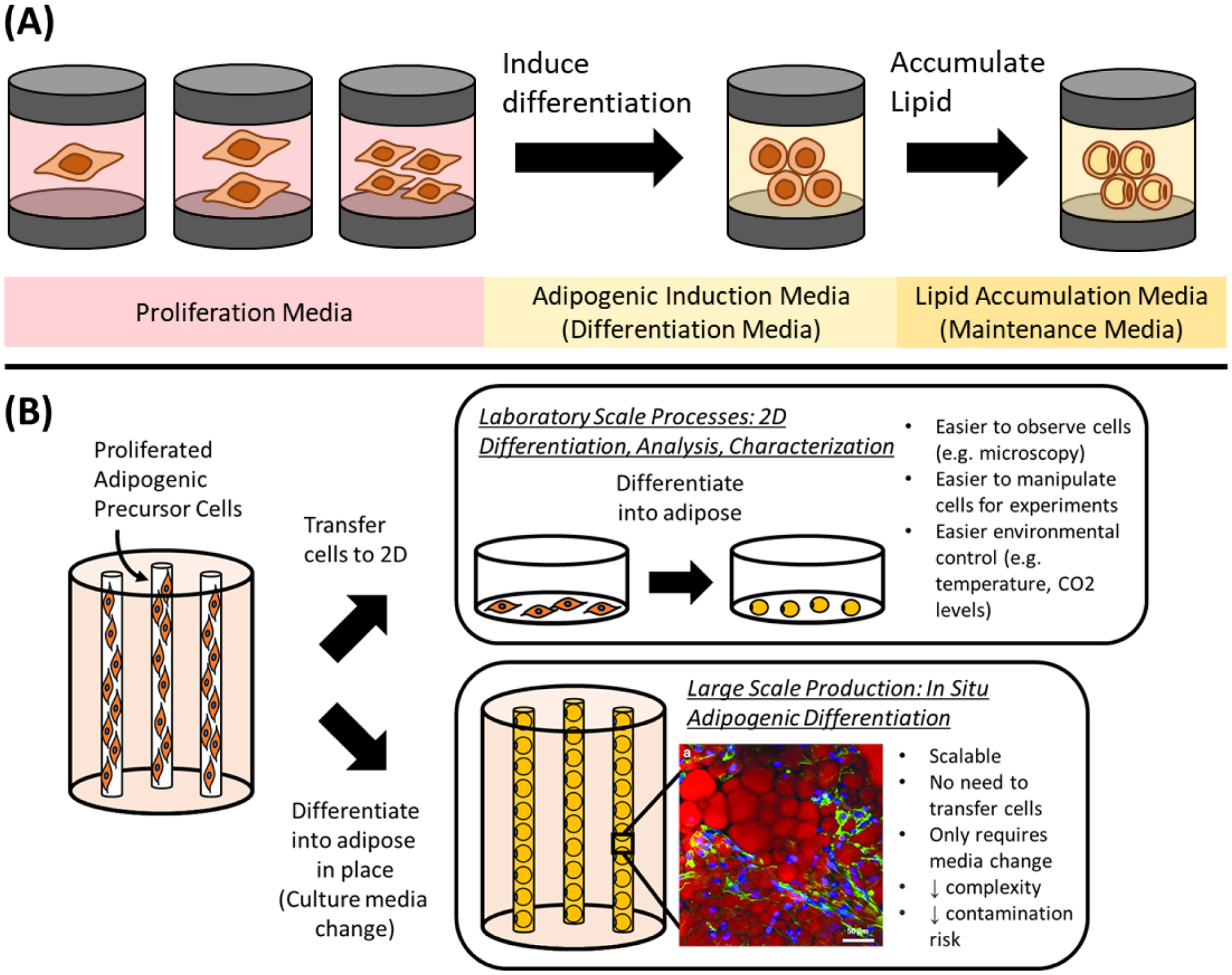

Figure 2.

(A) Biological sequence of events for adipogenic differentiation, where proliferated adipose precursor cells are differentiated via an adipogenic induction medium (differentiation medium), followed by a switch to a medium designed to foster subsequent lipid accumulation (maintenance medium) after the cultured cells become primed for adipogenesis. (B) In situ adipogenic differentiation using a hollow fiber bioreactor as an example - leveraging the same proliferation bioreactor environment to enable the differentiation of adipogenic precursor cells by merely changing the culture media. This is juxtaposed with the conventional practice of taking cells out of the proliferation bioreactor and differentiating them on 2D cell culture substrates. Inlay of hollow fiber differentiated adipose from [259] stained with AdipoRed, scale bar is 50 μm.

For proliferation media, numerous serum free formulations have been devised for the adipogenesis-competent cells that we have covered in this review, albeit often still comprising of animal components such as growth factors, extracellular matrix components and other signaling molecules [173,175,176,226–232]. Individual animal components are often produced recombinantly, but the question then shifts to cost and commercial viability. Low cost recombinant protein production may be feasible when performed at scale though; and simple serum free formulations only requiring a few recombinant factors exist for certain cell types such as MSCs [227,233–235]. Other approaches that may avoid the use of recombinant growth factors exist in the form of purported serum replacements such as algae, yeast, mushroom, numerous plant extracts, as well as various plant protein hydrolysates [236–240]. Synthetic peptides also show promise as a way of mimicking full growth factors such as FGF2 at a lower cost [241]. If desired, even animal products such as pork plasma could be marshalled to supplement culture media as a way to valorize waste and by-products from the meat industry [242].

For adipogenic differentiation and maintenance media, there have been numerous reports across species of serum free adipogenesis, as well as some cases documenting how the exclusion of serum can even lead to improved adipocyte lipid accumulation and gene expression [72,91,92,231,232,243,244]. As was the case for proliferation media, there have been reports of plant based culture media components promoting adipogenic differentiation in cultured cells such as MSCs [238]. It is important to note though, that adipogenesis media formulations may not be readily interchangeable across species due to differences in adipose biology between livestock species [71,245–247]. For example, porcine and avian adipocytes use glucose as the primary building block for fatty acid synthesis, while bovine and ovine adipocytes use acetate [247]. These differences may relate to how optimal adipogenic differentiation media for adipocytes of varying species can differ considerably: Ovine cells have been shown to require a prolonged period of adipogenic induction (via the inclusion of a PPARγ agonist in their differentiation culture media) in order to accumulate intracellular lipid, whereas murine cells show no such requirement and begin accumulating lipids much more readily with fewer adipogenic media factors [248,249]. For other cell types, there has been success with the adipogenic differentiation of human, mouse and porcine DFAT cells, but similar differentiation media formulations do not as robustly induce adipogenesis in bovine DFAT cells [71]. The optimization of adipogenesis in less elucidated species such as cows is taking place over time though, with insights emerging on alternative adipogenic factors that are able to induce lipid accumulation. For example, addition of the growth factor BMP4 during the proliferation stage of bovine skeletal muscle MSCs has been shown to improve adipogenesis, while small molecules such as certain retinoids and carotenoids have been shown to perform better than rosiglitazone (PPARγ agonist) in bovine preadipocytes [76,250]. Very recently, robust adipogenesis has been demonstrated in bovine DFAT cells using adipogenic media containing 0.25% and 2.5% FBS, as opposed to the standard 10% FBS [72]. The same DFAT cells treated with was also found to exhibit maximal glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH) activity when treated with 1 mM acetate.

During the large scale production of cultured meat, culture media is one of the largest contributors to cost [42,251]. As such, media recycling may be an important consideration for boosting efficiency and extending culture media utility. The buildup of metabolic waste products is often the limiting factor that requires culture media changes in conventional cell culture, often limiting cell growth as other nutrients and growth factors remain present at sufficient amounts. In a smaller scale (100 ml working volume) suspension bioreactor that refined culture media via dialysis, media recycling with only 1 media change permitted a culture of iPSCs to proliferate at the same rate as a conventional culture with 5 media changes [252]. In this system, saving unused growth factors and nutrients led to a 2 to 3-fold reduction of the amount of TGF-β1, insulin, transferrin, ascorbic acid and selenium required during cell proliferation. It is important to note though, that while this example of media recycling offers great cost reduction potential (because growth factors are the largest component of culture media cost), dialysis is known to be water intensive. In this example, the 2 to 3-fold reduction of certain media components required a 4 to 5-fold increase in water usage due to the need for dialysis media [251]. Alternative methods of recycling culture media or extending its use are thus worth investigating. For example, extending culture media has also been explored through the co-culture of mammalian cells with algae, with decreased lactic acid and ammonia levels observed in co-culture groups when compared to mono-culture controls. It was hypothesized that algae-produced oxygen promoted aerobic respiration, while ammonia was metabolized by co-cultured algae to produce amino acids [253,254].

Metabolic and genetic engineering approaches are additional options for reducing culture media costs. Glutamine synthetase overexpression is an option for reducing glutamine requirements in culture media, while also providing a method of reducing NH3 levels as it is an substrate of the enzyme [255]. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells engineered to overexpress enzymes of the phenylalanine-to-tyrosine biosynthesis pathway gained the ability to grow in culture media devoid of tyrosine, while also producing fewer growth inhibitory compounds associated with bottlenecks during tyrosine synthesis [256]. In the same study, improved proliferation was observed in CHO cells treated with CRISPR to knock out the enzyme branched chain aminotransferase 1, which halted the production of various compounds that were inhibitory to cell growth. For more information and examples of cell optimizations for improved growth and viability, we refer the reader to [257].

Several key challenges lay in the way of effective culture media development for cultured fat. However, various paths exist that may help overcome these obstacles. The inclusion of recombinant proteins in serum free media formulations for adipocyte precursor cell growth represents a pain point in cost, but solutions may exist with the use of small molecules or peptides that can mimic full growth factor proteins. The emergence of alternate adipogenic differentiation media formulations for difficult cases such as bovine adipogenic precursor cells bodes well for achieving robust lipid accumulation in the future. Culture media requirements may also be fundamentally lowered through the rational engineering of cultured cells to limit the production of inhibitory metabolites and reduce exogenous growth factor requirements. Media recycling may also be an important component in extending a single batch of culture media, because expended media often contain unused nutrients and growth factors.

Methods to Induce Adipogenic Differentiation and Lipid Accumulation at Scale

In previous sections we have outlined studies on the scaled proliferation of adipogenic precursor cells such as MSCs and PSCs. Many groups have demonstrated the feasibility of using stirred suspension tanks or hollow fiber bioreactors for large scale cell production. However, in these studies cells are often adipogenically differentiated using traditional 2D culture techniques [139,176,177,258]. During large scale processes, this would lead to a bottleneck in production as transferring large numbers of cells to well plates and petri dishes for differentiation would not be tenable. Thus, scalable methods of differentiating proliferated adipose precursor cells are needed.

In situ Adipogenesis

One method to induce adipogenesis at scale would be to perform an in situ differentiation, where cells proliferated in a bioreactor are differentiated in place via a change in culture media or through the addition of adipogenesis-inducing factors (Figure 2B). This has the advantage of eliminating cell transfer from proliferation bioreactors to a separate bioreactor or apparatus for differentiation, enabling reduced complexity, cost and risk of contamination. For hollow fiber bioreactors, such an in situ adipogenesis approach has been reported using polyethersulfone (PES) fibers, where cells were expanded for 2–3 weeks and then differentiated via a change from proliferation to adipogenic media [259,260]. After 2 weeks of differentiation, cultured MSCs on the hollow fibers had differentiated better than 2D cultured adipocytes. For food applications, it may be possible to detach PES hollow fiber-grown adipocytes (e.g., proteolytically with enzymes such as TrypLE, Accutase and TrypZean) for further downstream processing [206,261–263]. Alternatively, edible hollow fibers could be used for process simplicity and to avoid obstacles such as hollow fiber clogging during cell detachment, while also preserving adipocyte extracellular matrix (ECM) components that would typically be degraded when using proteolytic enzyme-based cell detachment approaches [264,265].

For suspension cultures, in situ adipogenic differentiation was demonstrated using stirred suspension tank and rotating wall vessel bioreactors, where adipogenically differentiated MSC spheroids (via an addition of adipogenic factors to the media) accumulated more lipid when compared to 2D controls [192]. ESC spheroids have also been adipogenically differentiated, but only in static suspension cultures [266]. While promising, these studies on MSCs and ESCs were performed using preformed spheroids, which in terms of cell expansion is less efficient and more complicated to scale up when compared to suspension cultures that are inoculated with single cells [194]. Nonetheless, the fact that other studies have demonstrated MSC and ESC spheroid formation from single cell inoculations suggests that an efficient expansion of MSCs and ESCs – followed by their in situ differentiation into adipocytes – should be possible [175,258]. This has been demonstrated beyond MSCs and ESCs, where single cell inoculated 3T3-L1s in a rotating wall vessel bioreactor formed spheroids and accumulated lipid [191]. 3T3-L1 spheroids were also differentiated into fat upon deliberate induction with adipogenic media, which is important for preventing cells from spontaneously differentiating during proliferation and exiting the cell cycle [185].

Potential Food-Safe Strategies to Induce and Enhance Adipogenic Differentiation

While the in situ adipogenic differentiation of cells within proliferation bioreactors has been outlined as an attractive option for large scale cultured fat production, the formulations of differentiation media typically used to induce adipogenesis often contain ingredients that may be questionable for a food production process. Conventional adipogenic differentiation media commonly contains ingredients that are not approved for food use (e.g., 3-isobutyl-1-methylxanthine), or compounds (indomethacin, rosiglitazone, dexamethasone) that are used as medical drugs [267]. Although the use of such compounds may only be required transiently during the initial induction of adipogenesis – and may thus be diluted to negligible levels by media exchanges during extended cell culture – here we cover alternative options for inducing adipogenesis that may be relevant to large scale food production scenarios (Figure 2B).

Free Fatty Acids to Induce Adipogenesis

Certain free fatty acids (FFAs) have been characterized as agonists of PPARγ and have thus been investigated as adipogenesis-inducing compounds [268]. For livestock cells, bovine stromal vascular cells from adipose tissue have been induced to differentiate using a cocktail of monounsaturated and branched chain fatty acids [82]. In experiments of FFAs added to conventional differentiation media for bovine stromal vascular cells, oleic and linoleic acid were found to be the most efficacious for promoting lipid accumulation [269]. For bovine muscle satellite cells, oleic acid was found to promote adipogenic gene expression and lipid accumulation [270]. FFA-based adipogenesis has been demonstrated with porcine preadipocytes using oleic acid, linoleic acid and to a lesser extent the omega 3 FFA α-linolenic acid [271]. Oleic acid alone has been shown to be sufficient for inducing lipid accumulation in chicken preadipocytes [272,273]. Preadipocyte cell lines such as 3T3-L1s have also been differentiated with FFAs [274].

FFA-induced adipogenesis appears to have not been reported for PSCs, however the differentiation path of PSCs to adipocytes typically routes through an MSC or MSC-like cell phase, followed by adipogenic induction via a conventional differentiation media designed for MSC adipogenesis with cow, pig and chicken cells [113,114,275]. The fact that the final stage of PSC to adipocyte differentiation is the same as MSC adipogenesis suggests that it may be possible to substitute conventional differentiation media formulations with an FFA-based protocol once PSCs are induced to become MSC-like.