Abstract

The human and financial costs of dementia care are growing exponentially. Over five and a half million older Americans are estimated to be living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia (ADRD). By 2050, this is expected to increase to over 13 million, and persons of color are at the highest risk. Considerable funds have been committed to research to prevent, treat, and care for persons at risk for ADRD. However, enrollment of research participants, particularly those coming from diverse backgrounds, is a perennial challenge and has serious implications. This paper quantitatively details the results of a community-based multi-modal outreach effort to recruit a racially diverse sample for non-pharmacological dementia intervention, including referral and participant sources and yield, total recruitment costs and cost per enrolled dyad, and a qualitative description of lessons learned, with particular attention to the recruitment of Black participants. The largest number of referrals and referrals converting to study participants, for both Black and White persons, were from a Maryland Department of Health mailing to Medicaid recipients. There was an important difference in the most effective strategies, proportionally, for white and Black participants. The MDH mailing had the highest yield for our Black referrals and participants, while professional referrals had the highest yield for white referrals and participants. The total estimated cost of recruitment was $101,058, or $156.19 per enrolled dyad. Ultimately 646 persons with dementia and care partner dyads were enrolled, 323 (50%) of whom were Black.

Keywords: Dementia, care coordination, recruitment, diversity, community outreach, memory disorders

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease is a present and looming crisis. Soon, the costs, both human and financial, of dementia care will grow exponentially. Over five and a half million older Americans are estimated to be living with Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementia (ADRD),1 and Alzheimer’s Disease is expected to double by 2060 with 13.9 million Americans projected to be diagnosed.2 Alzheimer’s disease is the fifth leading cause of death in those ≥65 years of age.1

This sweeping epidemic will not affect all older people equally, however. The highest burdens will be on Black and Hispanic people. By 2050, 20% of persons living with dementia (PLWD) will be Black.1 Further, 13.8 percent of Black people over the age of 65 are estimated to have the highest burden of Alzheimer’s disease from 2015 to 2060.2

Given these disparities, it is critical to enroll Black people into clinical trials for ADRD research. Historically, recruitment of people representing diverse racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds into ADRD clinical trials, where most research has been conducted, has been challenging, largely because patient populations in these centers are not racially diverse.3,4 Barriers have included availability of a study partner, attitudes toward research, and logistical and financial constraints.3

The barriers for recruitment of Black people are greater and represent unique - perhaps more intransigent - challenges. Recruitment of Black people into ADRD studies is met with a significant history of injustices from the health care and research communities such as poor-quality, culturally incompetent care, unethical treatment, and lack of integrity, all of which has resulted in mistrust.5–7 Failure to sufficiently enroll Black and Hispanic participants will misrepresent the validity of potential treatment and limit generalizability of interventions for populations most at risk of dementia.

Several studies have examined the differential return of various recruitment strategies.8,9 Effective strategies include community group referrals generally8 and advertising, and collaboration with health care providers for minority.9

Costs of recruiting a diverse sample of dyads for ADRD research is poorly studied. In 2000, Tarlow examined costs associated with recruiting caregivers of PLWD from care settings with brochures, mailing and newspaper ads, all of which reportedly helped develop a sense of legitimacy. The team recruited 100 participants at a cost of $10,127, a rate of $101 per participant.10

In related research, Morrison et al, 2016, compared effectiveness and cost of three strategies in enrolling 237 PLWD/caregiver dyads into a home-based dementia support program aimed at improving functioning and quality of life. These researchers found that direct mailings were the most effective at the lowest cost, while newspaper advertisements and community outreach were more costly and less effective. Overall, recruitment costs, including staff time, were $154/dyad. Analysis of best strategies by race of participant was limited because only 26% of the sample consisted of Black people.11

Between 2015 and 2017, a Johns Hopkins study team implemented a wide-ranging research recruitment effort in the Baltimore-Washington DC area to enroll a diverse sample of PLWD in the community and caregivers (CGs) into two large federally funded dementia care coordination trials.12,13 The goal was to approximate the diversity represented in the City of Baltimore14 in the participant pool. This paper critically examines the costs and yield of those strategies for these trials and provides guidance on recruitment in future dementia trials, especially for recruiting a racially diverse pool of participants. These findings provide new, more nuanced information to support researchers in the planning, design, and implementation of future dementia trials.

Materials and Methods

This analysis describes the recruitment of research participants enrolled into one of two concurrent studies, an NIA-funded randomized controlled trial (MIND-RCT; R01AG046274), or a CMS Health Care Innovation Award Round 2 demonstration project (MIND-HCIA; 1C1CMS331332) that took place between 03/2015 and 04/2017 in the Central Maryland and Greater Baltimore-Washington Region. Both studies were evaluating a comprehensive, home-based dementia care coordination program, Maximizing Independence at Home (MIND at Home). Recruitment included referrals from community organizations, health care providers, local and state Medicaid waiver programs, health departments, and a broad community outreach campaign with community-based events and local media publicity. The team categorized, tracked and recorded all recruitment efforts over the course of enrollment including costs incurred as well as the disposition status of unique referrals to the studies.

For the MIND-HCIA study, the initial aim was to enroll 600 dually eligible Medicare-Medicaid beneficiaries with a diagnosis of dementia living at home in Baltimore City, Baltimore County, and Howard County into a demonstration project to evaluate the impact of MIND at Home on clinical outcomes and health care expenditures. Due to recruitment difficulties discussed below, the eligibility criteria were expanded to include Medicare-only beneficiaries, individuals from a broader area, and a requirement that the person meet all cause criteria for dementia rather than have a dementia diagnosis.

For MIND-RCT the aim was to recruit and enroll 300 individuals with dementia and a caregiver who lived at home in the same geographical area to evaluate the effectiveness of a streamlined version of MIND at Home. There were no criteria related to insurance for this project.

For both studies, participants and their caregivers needed to speak English.

Recruitment Approach

The multi-modal recruitment approach included a broad community-level marketing campaign as well as a targeted outreach to specific population segments. Strategies included community organization mailings and e-blasts (including Easter Seals, County- and City-level Departments on Aging, Meals On Wheels, the Alzheimer’s Association, AARP Maryland), hosted tables and seminars at community events and health fairs, direct referrals from primary care and specialty providers (e.g., geriatric psychiatry, neurologists, social workers), formal and informal presentations to specific providers/organizations/commissions/councils/other stakeholders, print and radio advertising, newsletter articles, and other local media publicity. This recruitment approach was designed to target low-income residents through outreach to community associations serving those residents. All recruitment materials were in English because the project could only enroll participants who were fluent in English.

A primary recruitment source was a new collaboration with the Maryland Department of Health (MDH) to send recruitment letters to individuals who were either dual eligible or those on a Medicaid Waiver waitlist. These individuals were identified through a partnership with The Hilltop Institute, which houses Maryland’s Medicaid data and conducts research. The study team received approval to work with the state Medicaid data through leaders at MDH and all study protocols were reviewed by their IRB. Importantly, study team members never had direct access to the Medicaid participant lists as all mailings were handled by a HIPAA compliant printer, who received mailing lists directly from Hilltop. Developing this relationship was crucial and involved a considerable time commitment of senior project staff.

The team also received guidance from a racially diverse Community Advisory Board (CAB) representing a range of stakeholders including state program partners, community-based aging organizations, providers, and caregivers. The Board provided input on recruitment sources; collaborated on mailings and other outreach; reviewed recruitment materials; and shared project information throughout their organizations. CAB members advised the adaptation of outreach and recruitment materials to emphasize participant payment for study time, to use more appropriate literacy levels, and to explain terms such as “care coordination” more simply.

Recruitment efforts that come from culturally competent sources can increase engagement of Black people in research.15,16 Consequently, we solicited advice and assistance, and did outreach through, culturally-competent, trusted Black community organizations such as radio stations with traditionaly Black audiences, meals on wheels, Medicaid, and the Alzheimer’s Association African American Forum. We also made targeted efforts to conduct presentations and participate in community events within Baltimore City, including to senior centers serving predominantly Black neighborhoods. The project staff member who coordinated the outreach had years of experience working with the Baltimore aging community, as well as engagement with organizations predominantly serving Black community members.

Data Management and Analysis

Study team members maintained a detailed database of activities for each recruitment strategy and event. This database was analyzed to determine the nature and extent of the recruitment effort in total (see “Recruitment strategies”). Costs of these recruitment efforts also were maintained in a database developed in concert with budget expenditures.

Individuals who heard about the study in one of the ways described above and called the study phone line to ask about participating are called “referrals” in this paper. The study team administered a standard interview protocol to collect information from interested callers (who were typically caregivers), which included information about the person with dementia’s race (a choice of: Black/African American, White, Asian, or other), ethnicity (Hispanic or non-Hispanic) and how the person had heard about the study (e.g., a mailing from MDH or a flyer from a community event). The team member used an access database to record the person’s information. If the person agreed to participate in the study, they were converted to “participant” in the access database.

The study databases were analyzed to assess the following questions:

How many potential recipients were referred by each recruitment strategy? (See Recruitment Strategies)

Which recruitment strategy was most effective for obtaining referrals, and which was most effective for different races? (See Referral Yield from Recruitment Strategy by Race)

Which recruitment strategy was most effective for enrolling participants, and which was most effective for different races? (See Participant Yield from Recruitment Strategies by Race)

How expensive were the individual recruitment strategies and what was the estimated cost per referral, per participant, and per participants of different races? (See Cost of Recruitment Strategies and Yield by Race)

Results

Recruitment strategies

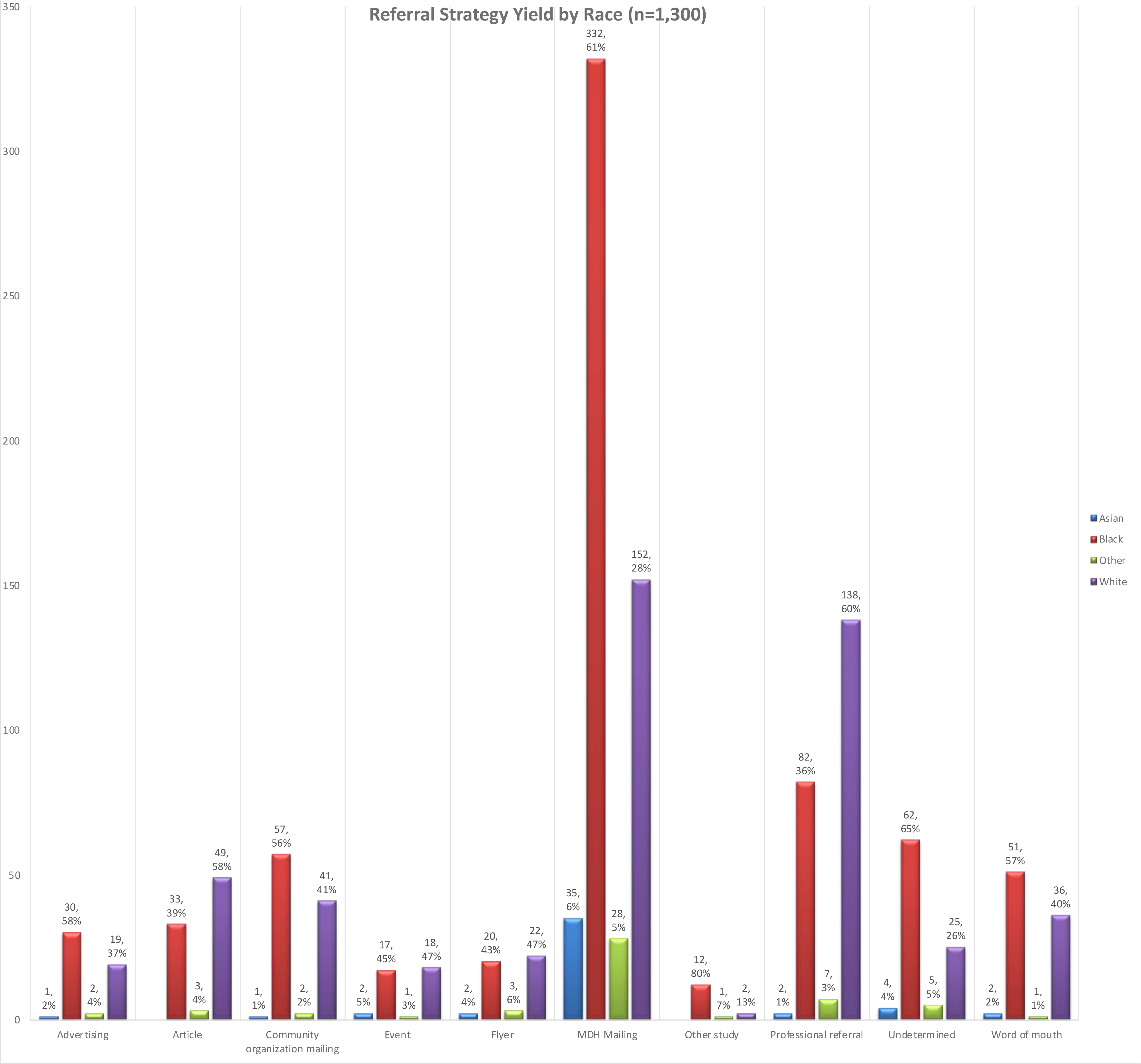

Referral Yield from Recruitment Strategy by Race

To understand how effective each strategy was in recruiting people of different races, we examined the highest yield within each strategy. For example, for the MDH mailing, the highest percentage yield was from Black people (61%), followed by white people (28%). For professional referrals, the highest yield was from White people (60%), followed by Black people (36%).

To understand which strategies overall were most effective in recruiting people of different races, we examined the highest yield across the strategies. For example, for referrals who were white, the highest percentage yield across the categories was from MDH mailing (33%) followed by professional referrals (30%). For referrals who were Black, the MDH mailing yield (51%) was also highest, much higher than for white referrals, followed again by professional referrals (13%).

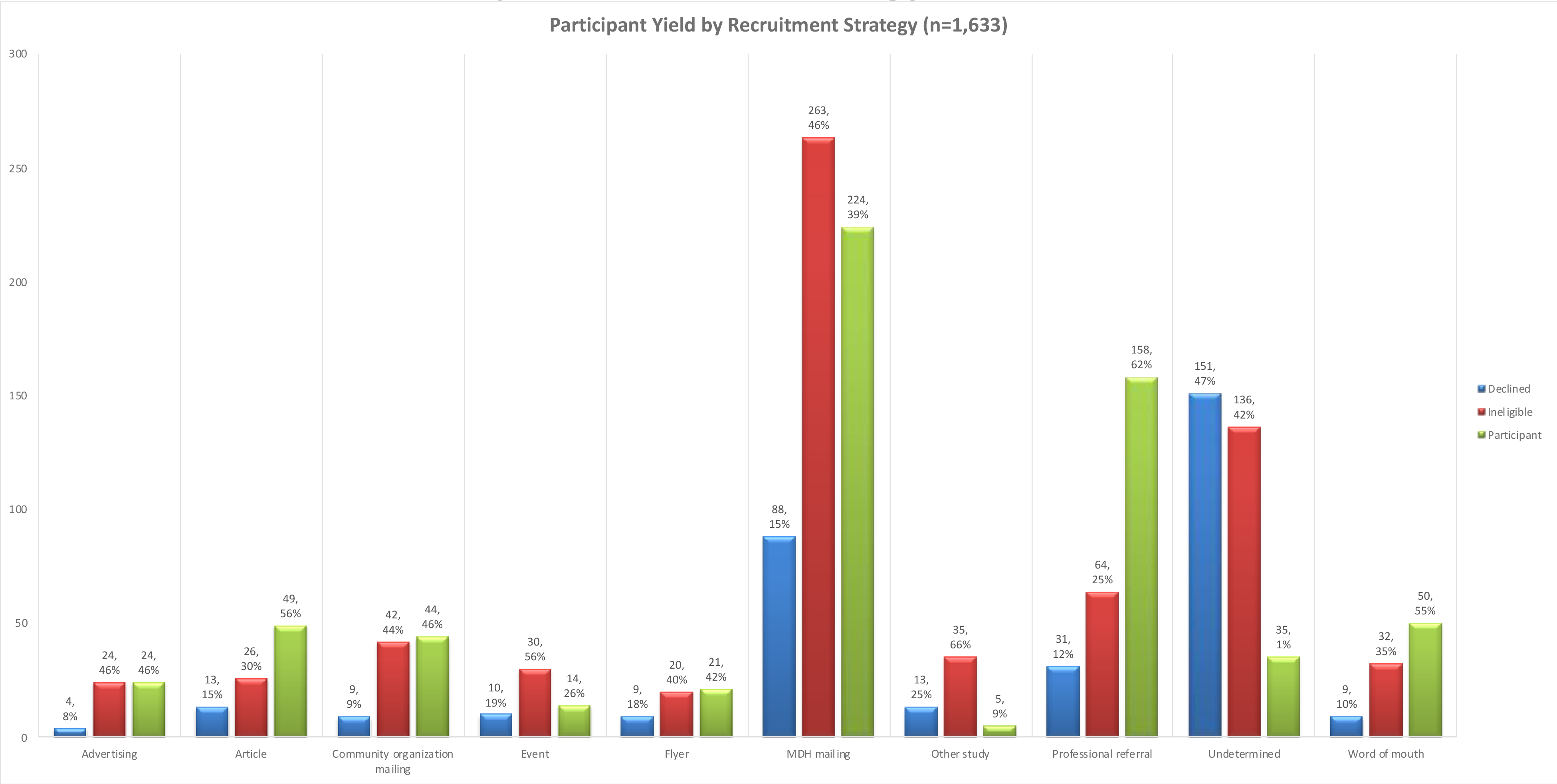

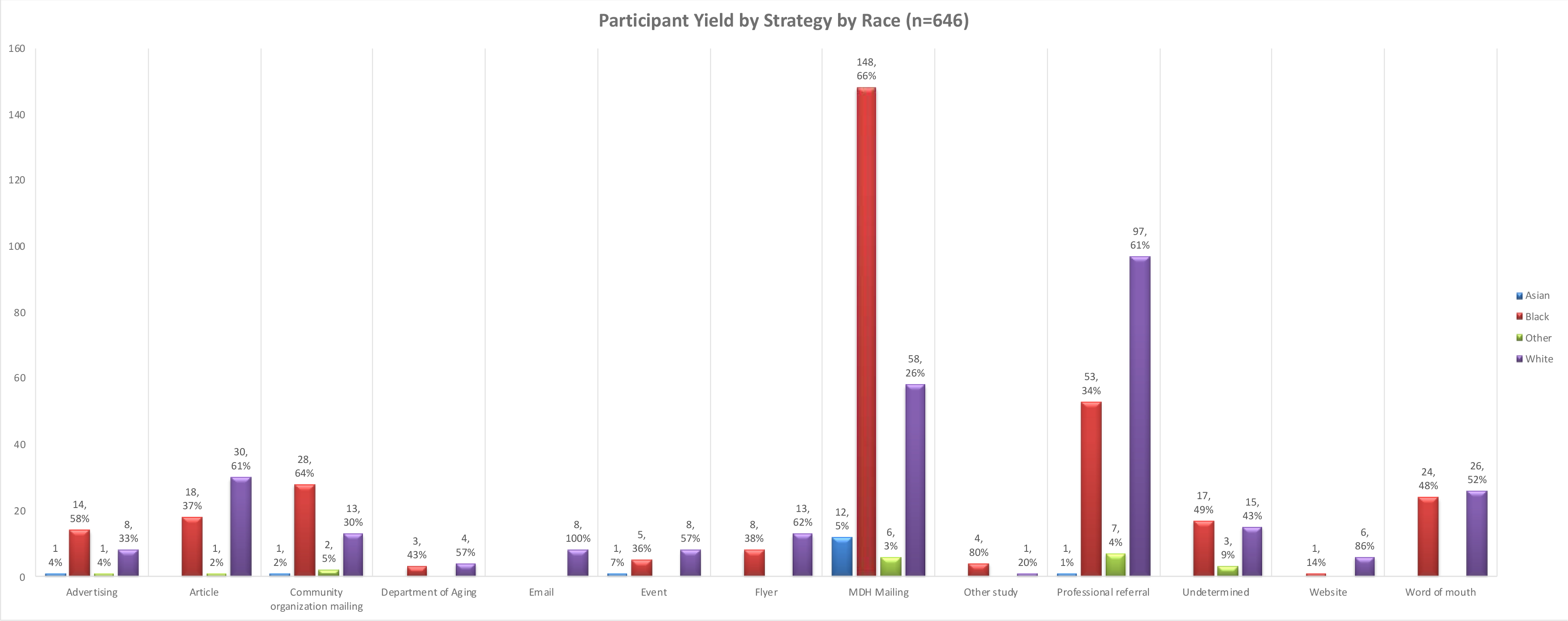

Participant Yield from Recruitment Strategies by Race

To understand how effective each strategy was in recruiting actual participants, we examined the highest participant yield within each strategy. For example, the highest yield of ineligible participants was in the MDH mailing (46%), and the highest percentage yield of actual participants was from professional referrals (62%).

To understand which strategies overall were most effective in recruiting participants, we examined the highest yield across the strategies. For example, just as for the referrals, the highest yield of participants (in green) across categories was from the MDH mailing (36%) and professional referrals (25%). Many people were sent a total of four rounds of letters, which may have been enough to establish that the mailing was important. The study team recruited a total of 646 participants, the majority of whom (50%) were Black.

To understand how effective each strategy was in recruiting participants of different races, we examined the highest participant yield within each strategy. For example, the highest yield of Black participants was in the MDH mailing (66%), and the highest percentage yield of white participants was from professional referrals (61%).

To understand which strategies overall were most effective in recruiting participants of different races, we examined the highest yield across the strategies. When examining the participant yield by race, the largest percentage of white participants was brought in through professional referrals (34%), followed by MDH mailing (20%). For participants who self-reported as Black, the same two strategies were the highest, but in reverse order 46% of Black participants were brought in by the MDH mailing, followed by professional referrals, which brought in 16% of Black participants.

Cost of Recruitment Strategies and Yield by Race

Not included here is salary for the staff person who ran the recruitment and enrollment effort for two years (at 67,500 per year) for both studies. This staff person developed relationships with the community organizations, hosted event tables, arranged for all advertising, and worked with the HIPAA compliant printer to obtain all needed copies and manage all mailings.

The project goal was to approximate the diversity represented in the City of Baltimore in the participant pool. According to census data14 for Baltimore City, Maryland, residents are 30.5% white alone, 62.4% Black alone, 2.6% Asian alone and 5.3% Hispanic. Although not exact, our participant pool did approximate the city profile.

Discussion

This paper reports on the effectiveness and cost of a multi-modal recruitment approach for two trials of dementia care coordination in a large metropolitan area. The goal was to recruit a diverse population, including those with lower incomes who are most vulnerable to poor outcomes. The approach also intentionally focused on recruiting Black people, who are most at risk of ADRD and health inequities. To do this, the strategy engaged trusted community organizations and health care professionals.

The expansive recruitment approach ultimately yielded a sample that approximated the race of the Baltimore City, Maryland community, which is noted as 62% Black according to the census,14and the population most at risk for dementia: we recruited 646 participants, 323 (50%) of whom were Black. This success took substantial financial investment, however. The total effort cost approximately $101,044, which represents a cost of $157 for each of the 646 participants, which does not include staff time.

The primary recruitment method was through letters to individuals who were either dual-eligible or on a Maryland Medicaid Waiver waitlist. The broader recruitment effort included additional community organization mailings and e-blasts, hosted tables and seminars at community events and health fairs, direct referrals from primary care and specialty providers, formal and informal presentations to specific stakeholders, print and radio advertising, newsletter articles, and other local media publicity.

For recruitment specifically for the MIND-CMS study, the initial focus was on dual eligible persons living with dementia. The project initially experienced difficulties in using Medicaid claims to identify beneficiaries with a diagnosis of dementia. At the start of the study, The Hilltop Institute estimated there were 120,000 dual-eligible beneficiaries (full and partial) in the state of Maryland, of which an estimated 98,000 lived in the community. Of these, it was estimated that 15 – 20% would have a dementia diagnosis (14,700–19,600). Because the actual incidence of dementia diagnoses in the claims data was even lower, the research team decided to send multiple rounds of letters to all dual-eligible individuals over the age of 65 in our Maryland catchment area, which significantly increased our cost.

Because of the difficulty of finding enough dual-eligible members of the community with a diagnosis of dementia, the research team changed eligibility criteria to include Medicare-only beneficiaries and individuals from a broader area. Further, because so few people have been diagnosed with dementia, the requirement that the person have a medical diagnosis of dementia was changed. Instead, we required participants to meet “all cause criteria” for dementia (criteria include impairment in social, functional and at least one cognitive ability), and that those changes represent a change from baseline regardless of etiology.17 The study team was then responsible for assessing their impairment in the listed “causes” to determine if they were eligible for the study.

A pattern emerged in the effectiveness of certain recruitment strategies over others first in referrals and then in participant yield. For both referrals and actual participants, the yield was greatest with mailings, but it took many mailings over time, at quite an expense. Importantly, our professional outreach and referrals were effective as well, which is not consistent with some prior research.8 This may be because our outreach was ongoing for 24 months, and medical professionals were often affiliated with Johns Hopkins and knew the project team members. While not as effective as other methods, outreach methods such as community organization mailings, articles in well-regarded publications and presentations that blanketed our catchment area likely laid the groundwork to build community knowledge of the projects, and as such are valuable to do and relatively inexpensive.

There was an important difference in the most effective strategies for white and Black participants. The MDH mailing was the most effective for our Black referrals and participants, while professional referrals were the most effective for white referrals and participants. The MDH mailings may have been especially effective for recruiting Black participants leery of health care providers or research in general because the letters came from the state Medicaid provider, a more trusted partner. Professionals may have referred fewer Black people because they have fewer Black patients, perhaps due to systemic bias against Black people. These biases can lead to lower rates of diagnosis, fewer Black people engaged in treatment, and Black individuals’ avoidance of medical professionals.18

Our findings are consistent with previous research documenting recruitment sources and costs for a similar population of people with dementia and their caregivers.10,11 For those studies, mailings were also most effective. Where this data diverges from the extant research is in the cost of the recruitment effort and our ability to recruit a racially and economically diverse sample. Our costs were much higher than Tarlow ($101/participant) and consistent with Morrison’s ($154), but Morrison included staff costs in that estimate, and we did not. Other researchers might then expect recruitment expenses needed for a large, racially, and economically diverse sample will be more costly.

These study findings are limited in several ways. First, the project could only enroll participants and caregivers who speak English. This restricted the ability to enroll Hispanic and Asian community members who did not speak English. Future research could include translation services, which would allow researchers to learn which strategies may be best for recruiting these individuals. Further, our cost estimates did not include staff time because the staff person who worked on recruitment was also responsible for other tasks, and this was not well tracked. The salary for this person was $67,500, and she was employed for two years. Finally, the reporting of race for referrals is limited because race data is missing for 691 (34%) of the 2,049 referrals to the projects. This data was missing when staff could not reach individuals who left a message or when a person declined participation before staff could capture race data.

Researchers hoping to improve the racial diversity of participant pools in dementia studies should be prepared to expend significant budget amounts to send multiple mailings in collaboration with trusted community partners, such as Medicaid providers. Second, recruitment from a group of health care professionals who themselves serve a black patient population is essential. Ultimately, a broad community outreach campaign, achieved through a combination of different methods appears to be an effective overall strategy.

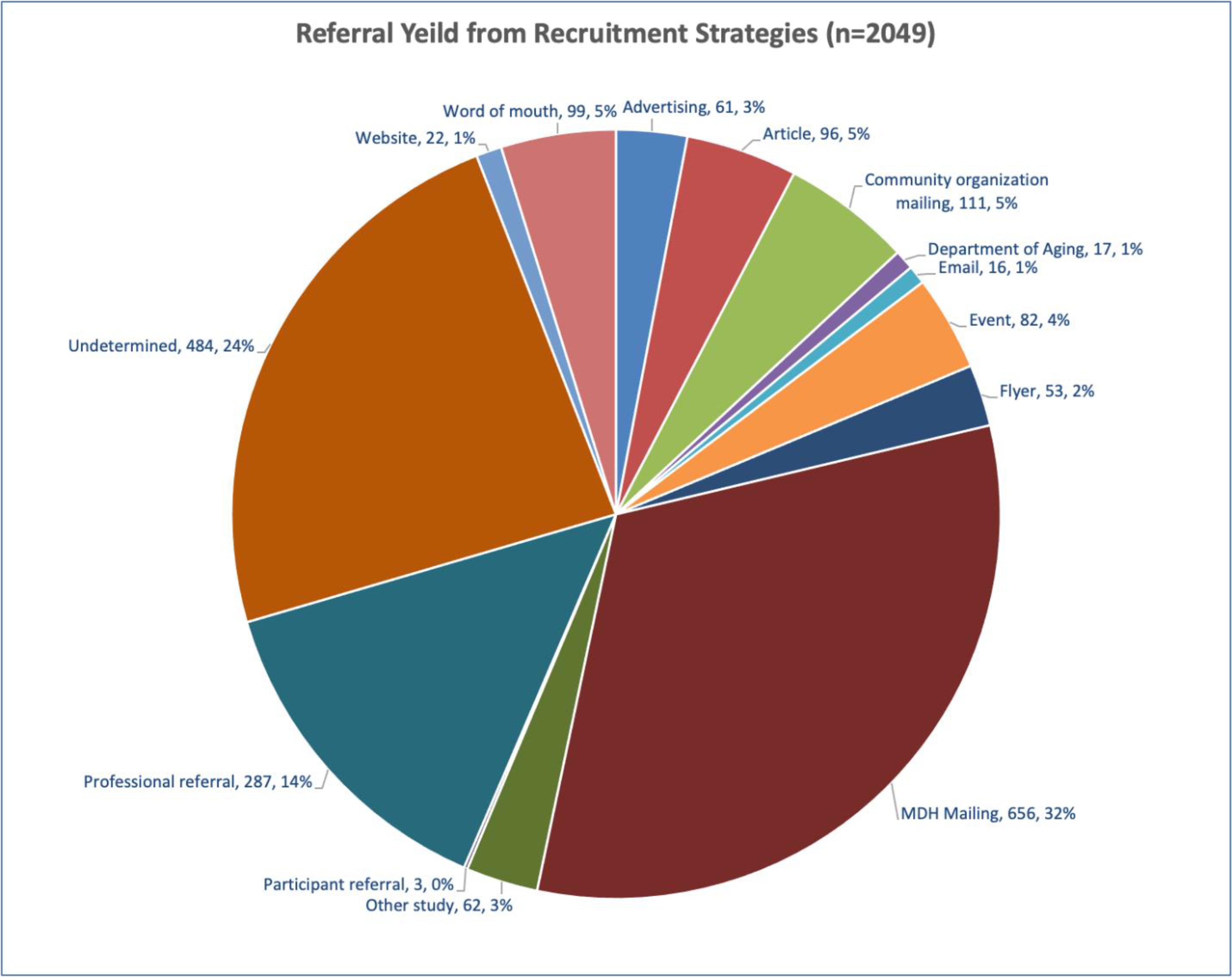

Figure 1. Number of unique referrals from different recruitment strategies (n=2049).

Figure 1 shows the yield of each recruitment strategy. The project received 2049 referrals during the recruitment phase. The largest numbers were from the MDH mailing and professional referrals. The “undetermined category” primarily consists of people who contacted us, but were later unreachable for further information, as well as those who did not remember how they heard about the study.

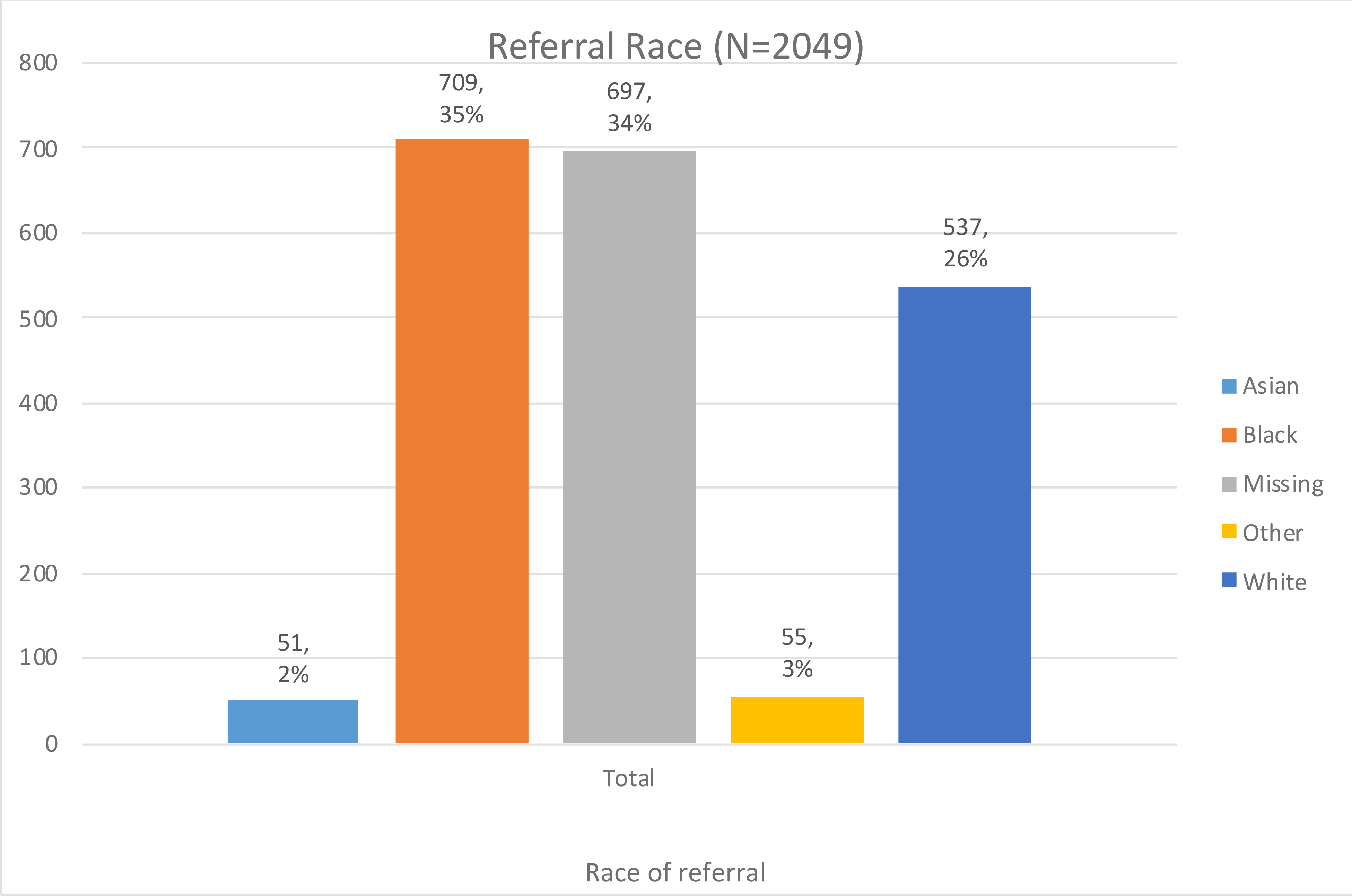

Figure 2: Referral Race (n=2049).

Figure 2 displays the race of study referrals. In addition, for the ethnicity question, only 45 individuals reported being Hispanic. The number of Asian and Hispanic referrals was very small, likely because we could only enroll English speaking individuals.

Figure 3. Referral Yield by Recruitment Strategy and Race (n=1,300).

Figure 3 shows the yield of several recruitment strategies by race of referral, detailing the percentage within that strategy category. Several ineffective strategies, which were those with 22 or fewer referrals or a total of 3% of referrals, are excluded. This excluded a total of 58 referrals that came from: Departments of Aging mailings, care partner-initiated emails to the study account, referrals from existing participants, and study website. Missing data on race (n=691) also reduced the sample in this chart, particularly from the “undetermined” group or people who did not complete the screening.

Figure 4. Participant Yield by Recruitment Strategy (n=1,633).

Figure 3 shows the yield of study participants from referrals, for each of the strategies, detailing the percentage within that strategy category. The study team was able to reach and screen a total of 1,685 people, who then either declined to participate, were ineligible or agreed. This graph excludes another 52 people referred from ineffective strategies excluded previously (6 of the 58 people excluded above were not screened and thus do not appear in this chart).

Figure 5. Participant Yield by Recruitment Strategy and Race (n=646).

To tell the full story for the participant pool, figure 5 includes the participants who were recruited by “ineffective strategies.” Figure 5 details the percentage within each strategy category.

Table 1.

Recruitment Strategies and Numbers of Recipients.

| Strategy | Count | Approximate total # of recipients |

|---|---|---|

| Community Organization Mailings (including Easter Seals, Department on Aging, MOW, Alzheimer’s Association) | 10 mailings | 10,000+ |

| MDH Mailing | 14 mailings | 38,474 |

| E-blasts (AARP Maryland) | 8 e-blasts | 87,000+ |

| Events, presentations, professional outreach | 88 events and presentations | 7,100+ |

| Advertising (including placemats and radio ads) | 10 ads | 500,000+ |

| Newsletter articles and website | 6 articles | 97,000+ |

| Totals | 136 | 739,574+ |

Table 1 summarizes recruitment strategies and the number of recipients for each. The large “approximate total # of recipients” for the advertising is based on listenership of the radio stations and readership of the placed advertisements. The approximate number of recipients for newsletters and E-blasts was obtained from the community organizations who distributed those newsletters. These strategies reached an approximate total of 739,574 persons, which included 24 discrete mailings, 88 community events, 6 articles, 8 e-blasts, and 10 advertisements.

Table 2.

Cost of Recruitment Strategies and Return on Investment.

| Strategy | Count | Approximate total # of recipients | Cost | Participant Yield | ROI - Total | Black Participant Yield | ROI - Black |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Community Organization Mailings (including Easter Seals, Department on Aging, MOW, Alzheimer’s Association) | 10 mailings | 10,000+ | $2,847 | 51 | $56 | 31 | $92 |

| MDH Mailing | 14 mailings | 38,474 | $52,879 | 224 | $236 | 148 | $357 |

| E-blasts (AARP Maryland) | 8 e-blasts | 87,000+ | $0 | 8 | $0 | 0 | $0 |

| Events, presentations, professional outreach | 88 events and presentations | 7,100+ | $21,892 | 198 | $111 | 70 | $313 |

| Advertising (including placemats and radio ads) | 10 ads | 500,000+ | $15,554 | 24 | $648 | 14 | $1,111 |

| Newsletter articles and website | 6 articles | 97,000+ | $0 | 55 | $0 | 19 | $0 |

| Other | $7,872 | 0 | 0 | $0 | |||

| Unknown (undetermined, word of mouth) | 84 | 0 | 41 | 0 | |||

| Total | $101,044 | 644 | $157 | 323 | $313 |

Table 2 includes the cost of each strategy and calculates a return on investment. The cost for mailings included copying letters and flyers, and postage. Additional costs related to events included registration fees, purchase of promotional materials (pens, hand sanitizers, etc.), and copying flyers. We mailed 112,342 pieces of mail for MDH. The average cost per participant was $157 and the average cost per Black participant was roughly $313.

Table 3.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants with Dementia (All-Cause)

| Person Living with Dementia Characteristics | Mean (SD) | N (%) | Total n | Min-Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 79.95 (9.75) | 646 | 36–103 | |

| Female, No. (%) | 446 (69.0) | 646 | ||

| Black/African American or Other Non-White Race, No. (%) | 360 (55.8) | 645 | ||

| Education, mean (SD), y | 12.30 (3.87) | 637 | 0–28 | |

| Living with Caregiver or Other, No. (%) | 511 (79.1) | 645 | ||

| Annual Household Income 25K or more, No. (%) | 240 (42.9) | 559 | ||

| No. routine medications taking, mean (SD) | 5.09 (3.93) | 629 | 0–24 | |

| General Medical Health Rating, mean (SD) | 2.77 (0.83) | 646 | 1–4 | |

| ≥ 1 hospitalization in past year, No. (%) | 245 (38.8) | 632 | ||

| ≥ 1 ED visit in past year, No.(%) | 195 (30.9) | 632 | ||

| MMSE (out of 30), mean (SD) † | 19.2 (7.7) | 623 | 0–30 | |

| Mild (21–30) | 244 (39.2) | |||

| Moderate (11–20) | 259(41.6) | |||

| Severe (0–10) | 120 (19.3) |

Table 3 displays the demographics of the resulting participant pool. Participants ultimately enrolled in the MIND at Home studies (n = 646) were an average age of 80 (standard deviation [SD] = 9.8); mostly (69%) female; and were majority non-white race (56% non-White). The average Mini-Mental State Exam score (ranging from 0 to 30) at enrollment was 19.2 (SD = 7.7), with 39% in the mild stage, 42% in the moderate, and 19% in the severe stage. About 20% lived at home alone.

Highlights.

Maximum recruitment from mailed letters and professional referrals

Diverse sample enrolled due to trusted partners.

Multiple mailings were costly but effective.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the caregivers and people living with dementia who participated in our project, our funders and sponsors, The National Institute of Aging (NIA) and the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Innovation (CMMI), and our partners in this work, and particularly the Maryland Department of Health, the University of Maryland Hilltop Institute, The Alzheimer’s Association Greater Maryland Chapter, AARP Maryland, and Jewish Community Services in Baltimore, MD and the Johns Hopkins Home Health Care Agency, who executed the care coordination programs.

Funding

The author(s) disclose receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by Grant Number 1C1CMS331332 from the Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (US) and by Grant Number R01AG046274 from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health (US). The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health or any of their agencies.

Footnotes

Disclaimers/Disclosures

Conflict of interest statement

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Previous Presentation of Abstract

A limited amount of data presented in this manuscript was presented in a poster presentation at the Geriatric Society of American (GSA) Virtual Conference in 2020. Reference: Reuland M, Johnston D, Bunting M, et al. Recruitment of Diverse Research Cohort in Large Metropolitan Area for Dementia Intervention Studies. Geriatric Society of American (GSA) Virtual Conference presentation, 2020.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Melissa Reuland, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, SOM Department of Psychiatry, 5200 Eastern Avenue, Room 322E, Baltimore MD, 21224.

Danetta Sloan, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Health Behavior and Society, Hampton House 904E.

Inga Margret Antonsdottir, Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, 525 N. Wolfe Street Baltimore, Maryland 21205.

Morgan Spliedt, Memory & Aging Services Innovation Center, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, SOM Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, 5200 Eastern Ave., Room 319E, Baltimore, MD 21224.

Mary C Deirdre Johnston, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Division of Geriatrics Psychiatry and Neuropsychiatry, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, 5200 Eastern Ave., East Tower, 3rd floor, Baltimore, MD 21224.

Quincy Samus, Director of the Memory and Aging Services Innovation Center, Division of Geriatrics Psychiatry and Neuropsychiatry, Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, 5200 Eastern Ave, Mason F. Lord Building, East Tower #326, Baltimore, MD 21224.

References

- 1.Alzheimer’s Association. 2021 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2021;17(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matthews KA, Xu W, Gaglioti AH, et al. Racial and ethnic estimates of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias in the United States (2015–2060) in adults aged≥ 65 years. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2019;15(1):17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grill JD, Galvin JE. Facilitating Alzheimer’s disease research recruitment. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2014;28(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szabo SM, Whitlatch CJ, Orsulic-Jeras S, Johnson JD. Recruitment challenges and strategies: Lessons learned from an early-stage dyadic intervention (innovative practice). Dementia. 2018;17(5):621–626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watson JL, Ryan L, Silverberg N, Cahan V, Bernard MA. Obstacles and opportunities in Alzheimer’s clinical trial recruitment. Health Aff 2014;33(4):574–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dilworth-Anderson P, Cohen MD. Beyond diversity to inclusion: recruitment and retention of diverse groups in Alzheimer research. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24:S14–S18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilmore-Bykovskyi AL, Jin Y, Gleason C, et al. Recruitment and retention of underrepresented populations in Alzheimer’s disease research: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s Dement Transl Res Clin Interv. 2019;5:751–770. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carr SA, Davis R, Spencer D, et al. Comparison of Recruitment Efforts Targeted at Primary Care Physicians versus the Community At Large for Participation in Alzheimer’s Disease Clinical Trials. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181aba927 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Wong R, Amano T, Lin S-Y, Zhou Y, Morrow-Howell N. Strategies for the Recruitment and Retention of Racial/Ethnic Minorities in Alzheimer Disease and Dementia Clinical Research. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2019;16(5):458–471. doi: 10.2174/1567205016666190321161901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarlow BA, Mahoney DF. The cost of recruiting Alzheimer’s disease caregivers for research. J Aging Health. 2000;12(4):490–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morrison K, Winter L, Gitlin LN. Recruiting Community-Based Dementia Patients and Caregivers in a Nonpharmacologic Randomized Trial: What Works and How Much Does It Cost? J Appl Gerontol. 2016;35(7):788–800. doi: 10.1177/0733464814532012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samus QM, Black BS, Reuland M, et al. MIND at Home-Streamlined: Study protocol for a randomized trial of home-based care coordination for persons with dementia and their caregivers. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;71:103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Samus QM, Davis K, Willink A, et al. Comprehensive home-based care coordination for vulnerable elders with dementia: Maximizing Independence at Home-Plus—Study protocol. Int J care Coord. 2017;20(4):123–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bureau UC. QuickFacts Baltimore City, Maryland; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lincoln KD, Chow T, Gaines BF, Fitzgerald T. Fundamental causes of barriers to participation in Alzheimer’s clinical research among African Americans. Published online 2018. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2018.1539222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang Angela Coker HD. Examining Issues Affecting African American Participation in Research Studies. J Black Stud. 2010;40(4):619–636. doi: 10.1177/0021934708317749 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mckhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease NIH Public Access. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit Racial/Ethnic Bias Among Health Care Professionals and Its Influence on Health Care Outcomes: A Systematic Review. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]