ABSTRACT

Background: It has been suggested that resilience is best conceptualized as healthy and stable functioning in the face of a potentially traumatic event. However, most research on this field has focused on self-reported resilience, and other patterns of response when facing adversity, in cross-sectional designs.

Objective: Alternatively, we aimed to study changing patterns of psychological responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in the general population, based on patterns of symptoms, and factors contributing to those patterns.

Method: A national representative sample of Spain (N = 1,628) responded to an internet-based survey at two assessment points, separated by 1 month (April and May 2020), during the official national confinement stage. Based upon whether participants exhibited absence/presence of distress (i.e., significant trauma-related, depression, or anxiety symptoms) at one or two of the assessment times, patterns of psychological responses were defined by categorizing individuals into one of the four categories: Resilience, Delayed distress, Recovered, and Sustained distress.

Results: Analyses of the levels of disturbance associated with the symptoms provided support to that four-fold distinction of patterns of responses. Furthermore, resilience responses were the most common psychological response to the pandemic. Multinomial regression analyses revealed that the main variables increasing the probability of resilience to COVID-19 were being male, older, having no history of mental health difficulties, higher levels of psychological well-being and high identification with all humanity. Also, having low scores in several variables (i.e., anxiety and economic threat due to COVID-19, substance use during the confinement, intolerance to uncertainty, death anxiety, loneliness, and suspiciousness) was a significant predictor of a resilient response to COVID-19.

Conclusion: Our findings are consistent with previous literature that conceptualizes resilience as a dynamic process. The clinical implications of significant predictors of the resilience and the rest of psychological patterns of response are discussed.

KEYWORDS: Resilience, psychological adjustment, anxiety, depression, PTSD, distress, trauma, COVID-19, well-being, trajectories

HIGHLIGHTS:

• National representative survey (N=1700) assessed twice during compulsory confinement. • Four patterns of response were identified and validated: resilience, sustained distress, delayed distress and recovered.• Resilience was the most common pattern (55.3% of the sample).

Antecedentes: Se ha sugerido que la mejor manera de conceptualizar la resiliencia es como un funcionamiento saludable y estable ante un evento potencialmente traumático. Sin embargo, la mayor parte de las investigaciones sobre la resiliencia y otras pautas de respuesta ante la adversidad se han centrado en el uso de cuestionarios de autoinforme de resiliencia en diseños transversales.

Objetivo: Alternativamente, nuestro objetivo fue estudiar los cambios en los patrones de las respuestas psicológicas a la pandemia de COVID-19 en la población general y analizar de manera empírica las características que contribuyen a la respuesta resiliente.

Métodos: Se utilizó una muestra nacional representativa española (N=1.628), que respondió a una encuesta realizada a través de Internet, en dos momentos de evaluación, separados por un mes, durante la etapa de confinamiento asociada a la pandemia (Abril y Mayo 2020). Se definieron los patrones de respuesta psicológica en función de la ausencia/presencia de malestar (v.g., síntomas significativos de estrés post-traumático, depresión y Ansiedad) en los dos momentos de evaluación, clasificando a los individuos en: resiliencia, malestar tardío, recuperación y malestar sostenido.

Resultados: Análisis de los niveles de interferencia apoyaron estos cuatro de patrones dinámicos de respuesta psicológica. Además, la respuesta de resiliencia fue la más común frente a la pandemia. Un análisis de regresión multinomial indicó que los predictores de una mayor probabilidad de resiliencia fueron ser hombre, tener más edad, no tener antecedentes de salud mental, y altos niveles de identificación con la humanidad y de bienestar psicológico. Además, bajos niveles en otras variables (ansiedad y amenaza económica debida a la pandemia, consumo de sustancias durante el confinamiento, intolerancia a la incertidumbre, ansiedad ante la muerte, soledad, y desconfianza) fueron también predictores significativos de una respuesta de resiliencia psicológica al COVID-19.

Conclusión: Nuestros hallazgos están en línea con la literatura previa que identifica la resiliencia como un patrón de respuesta común y un proceso dinámico. Se discuten las implicaciones clínicas de los predictores significativos de los cuatro diferentes patrones de respuesta.

PALABRAS CLAVE: resiliencia, ajuste psicológico, ansiedad, depresión, TEPT, malestar, trauma, COVID-19, bienestar psicológico, trayectorias

背景: 在缺乏对心理韧性通用定义的情况下, 有人建议最好将其概念化为面对潜在创伤事件保持健康和稳定的功能。但是, 大多数对于面对逆境时心理韧性和其他反应模式的研究都集中在横截面设计中对心理韧性的自我评估。

目的 :反之, 我们旨在根据症状模式研究普通人群对COVID-19疫情心理反应的变化模式及其促成因素。

方法: 在官方国家禁闭阶段, 一个全国代表性样本 (N = 1,628) 在两个相隔一个月的评估点 (2020年4月和2020年5月) 对网络调查做出了回应。根据参与者在一次或两次评估表现出/不存在困扰 (即明显的创伤相关, 抑郁或焦虑症状), 通过将个体分为以下四类之一来定义心理反应的模式:心理韧性, 延迟困扰, 康复和持续困扰。

结果: 对症状相关困扰水平的分析为四种反应模式的区分提供了支持。此外, 心理韧性反应是应对疫情最常见的心理反应。多项回归分析表明, 增加对COVID-19心理韧性的主要变量是男性, 年龄较大, 没有精神健康困难史, 心理健康水平较高以及对全人类的认同感。同样, 在几个变量中具有较低的水平 (即由COVID-19引起的焦虑和经济威胁, 分娩期间的药物使用, 对不确定性的不容忍, 死亡焦虑, 孤独和可疑性) 都是对COVID- 19心理韧性反应的预测因子。

结论: 我们的发现与先前将创伤事件后心理韧性确定为一种常见的反应模式, 并将其概念化为一种动态过程的文献一致。讨论了心理韧性和其他心理反应模式显著预测指标的临床意义。

关键词: 心理韧性, 心理适应, 焦虑, 抑郁, PTSD, 困扰, 创伤, COVID-19, 幸福感, 轨迹。

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic across the world has had a major impact on the levels of psychological adjustment in the general population (Qian et al., 2020; Shevlin et al., 2020; Valiente et al., 2020). Interestingly, these studies have also shown that a large percentage of adult individuals do not reach significant levels of distress as measured by standardized screening tools and that feelings of well-being are also present, intermingled with symptoms of psychological suffering (Valiente et al., 2020).

In the last two decades, epidemiological studies conducted in the general population have indicated that traumatic responses are not the rule when faced with adversity, but rather the exception. Some evidence came from representative studies of the general population which found that, while about two-thirds of adults report a lifetime exposure to at least one potentially traumatic event, rates of post-traumatic stress disorder are relatively low: 3.6% lifetime prevalence in the USA and 1.1% prevalence over 12 months in Europe (Darves-Bornoz et al., 2008). These findings contributed to the current interest in a reconceptualization of trauma that incorporates resilience as a common response pattern that deserves serious attention (Vazquez, 2013).

Although there is no universally accepted definition of resilience (Southwick, Bonanno, Masten, Panter-Brick, & Yehuda, 2014), it can be described as a stable trajectory of healthy functioning in response to a clearly defined event (Bonanno, 2012). This definition incorporates two important aspects: good functioning and stability in spite of adversity. Yet, conceptualizing what is good functioning can be elusive. Whereas in some cases resilience is simply defined as the absence of significant psychological symptoms (e.g., Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli, & Vlahov, 2006), other more comprehensive definitions of complete mental health (Keyes, 2007) combine both the absence of problems or symptoms and the presence of positive aspects of functioning (e.g., hedonic or eudaimonic well-being). In our study, we have included some specific positive mental health variables (i.e., well-being and positive attitude towards the future) as potential predictors of the participants’ patterns of psychological symptoms over time rather than integrating those variables in the own definition of resilience. Given the lack of consensus on which would be the key positive ingredients of resilience and their relative importance, an examination of patterns of response to the stressor, exclusively based on symptoms, may yield clearer results to understand the impact of the current pandemic in the individuals’ mental health. Regarding the second ingredient of the definition (i.e., stability or recovery over time), it can only be captured by a dynamic approach. Unfortunately, even though there have been early calls advocating for a dynamic view of the stress-response dialectics (Brown, Bifulco, & Harris, 1987), most of the existing research on resilience has been carried out using cross-sectional designs, which are limited to capture the temporal essence of resilience (Windle, Bennett, & Noyes, 2011). Studying stability across time requires longitudinal designs and sensitive measures to capture response variations, which are key components of the dynamic nature of resilience (Kalisch et al., 2019). Although two-point designs, like ours, are often used to identify trajectories of resilience (e.g., Bonanno et al., 2006; Hobfoll et al., 2009), ideally designs should include multiple point time measures (Galatzer-Levy, Huang, & Bonanno, 2018).

There is also a lack of agreement on whether to consider resilience as a predictor or as an outcome (Bonanno, Pat-Horenczyk, & Noll, 2011). Studies focusing on the predictive value of resilience have typically relied on self-reported trait-like abilities to cope with adversity (e.g., Windle et al., 2011). On the other hand, studies focusing on resilience as an outcome have rather focused on the magnitude of symptoms (e.g., Bonanno, Rennicke, & Dekel, 2005) or patterns of behavioural responses (e.g., García & Rimé, 2019). Infurna and Luthar (2018) suggested that, given the complementarity of different perspectives, the assessment of resilience should incorporate multiple measures to provide a more comprehensive picture of resilience. In our study, we have followed this recommendation by using both a standard self-report instrument of resilience (Brief Resilience Scale, Smith et al., 2008) and a symptom-based definition of resilience (e.g., Hobfoll et al., 2009). This empirical definition was based on the presence or absence of significant symptoms of anxiety, depression or post-traumatic stress measured in two time-points which resulted in four different types of psychological patterns (i.e., Recovered, Resilient, Sustained distress and Delayed distress). In addition, we provide an evidence-based corroboration of these four psychological patterns by identifying the amount of disturbance of daily functioning experienced in each of the groups as measured by the disturbance dimension of the International Trauma Questionnaire (Cloitre et al., 2018).

Most of the research in trauma has focused on the clinical features and predictors of symptoms and dysfunctional responses, while research on what promotes resilience has been comparatively scarce (Ungar & Theron, 2020). It is likely that resilience is not the result of one single factor, but rather of multiple independent predictors, each of which explains a relatively small portion of the variance (Bonanno et al., 2011). For example, Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli, and Vlahov (2007) found that after the September 11 terrorist attack the prevalence of resilience was predicted by a diverse array of sociodemographic and psychological variables as well as factors related to the previous history of the individual. Equally, Butler et al. (2009) found that after indirect exposure to this same terrorist attack, resilience was predicted by factors like being open to one’s own emotional reactions and having intact benign worldviews. Thus, to fully understand human resilience, a range of biological, psychological, social, and even ecological factors have to be taken into account (Ungar & Theron, 2020).

Following a multicomponent perspective of resilience, the present study includes a series of predictor variables that have been associated to resilience and psychological adjustment after the exposure to traumatic events such as demographic characteristics (e.g., Bonanno & Diminich, 2013; Campbell-Sills, Forde, & Stein, 2009), economic resources (e.g., McGiffin, Galatzer-Levy, & Bonanno, 2019), health-related factors (e.g., Zhu, Galatzer-Levy, & Bonanno, 2014) and good social network (e.g., Fritz, de Graaff, Caisley, Van Harmelen, & Wilkinson, 2018). Also, in the context of the current epidemic, several psychological factors potentially related to the stress-related responses were also included in the study. In this regard, Chen and Bonanno (2020) have recently argued that to better understand psychological dysfunction and resilience during the global COVID-19 pandemic, it is not only advisable to use longitudinal designs but also to incorporate multiple risk and resilience factors to improve outcome prediction.

1.1. Aim

The present study aims to: (i) provide a psychological response pattern classification based on the presence/absence of psychological symptoms over time; (ii) provide an objective, evidence-based validation of this classification by analysing the level of disturbance experienced by the subgroups; (iii) determine the role of sociodemographic, health, psychological and interpersonal variables in predicting membership in the pre-defined psychological response categories. We hypothesized that we would observe an increase in the probability of resilience for those with better previous health, less ideas of suspiciousness, less intolerance to uncertainty, more identification with humanity, lower levels of anxiety about the COVID-19 pandemic, absence of increased substance use and loneliness, better living conditions and more economic stability. Regarding the differential predictive value of these variables to discriminate between the four different types of response patterns over time to the pandemic, no specific hypotheses were set up.

2. Methods

As part of the efforts of an international Consortium to analyse the mental health effects of the COVID-19 (McBride et al., 2020), a longitudinal design was used to assess psychological adjustments during the pandemic in the adult general population of Spain (see further details of the general protocol in McBride et al., 2020 see project registration, for a detailed description, at https://osf.io/2y45r). An internet-based survey was designed via Qualtrics (https://www.qualtrics.com) and launched at two different assessment points: T1, took place at the peak of the pandemic (7–14 April 2020, when daily deaths related to COVID-19 were between 499 and 747) in the midst of a nation-wide confinement and; T2, conducted before the confinement measures began to unwind (7–11 May, when daily deaths were declining in the country, i.e. between 123 and 229).

2.1. Participants

Respondents were participants of an online research panel who completed a survey both at T1 and T2 (N = 1,700, 82.13% of compliance). The panel used stratified quota sampling to ensure that the sample characteristics of sex, age, household income, and population of each region matched the population of Spain. The average time to complete the first wave was 42.5 min (SD = 15 min), and 26.2 min (SD = 10 min) for the shortened survey at the second wave. Participants received a small monetary compensation each time (i.e. 1 euro). In both surveys, strict criteria were followed to ensure the validity of the responses, discarding those with questionable validity. The final sample used in the analyses was N = 1,628. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the School of Psychology (Complutense University) Deontological Commission.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Predictive variables

Socio-demographic Characteristics and Living Conditions. In addition to data related to sex, age and civil status, respondents provided information about other sociodemographic and housing conditions (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and living condition sample characteristics

| Participants (N = 1,628) |

|

|---|---|

| Gender [n (%)] | |

| Male | 859 (52.8) |

| Female | 766 (47.1) |

| Other | 3 (0.1) |

| Age [Mean (SD, range)] | 45.75 (12.76, 18-75) |

| Educational level [n (%)] | |

| No formal education | 5 (0.3) |

| Primary | 42(2.6) |

| Secondary | 153 (9.4) |

| Vocational training | 233 (14.3) |

| Baccalaureate | 371 (22.8) |

| University graduate | 617 (37.8) |

| Postgraduate | 207 (12.8) |

| Religion [n, (%)] | |

| Catholic | 877 (53.9) |

| Agnostic or Atheist | 658 (40.4) |

| Other | 93 (5.7) |

| Urbanicity of residential location [n (%)] | |

| Urban | 1,380 (84.8) |

| Rural | 248 (15.2) |

| Current economic activity [n (%)] | |

| Full-time job | 926 (56.9) |

| Part-time job | 168 (10.3) |

| Unemployed | 282 (17.3) |

| Retired | 154 (9.5) |

| Student | 85 (5.2) |

| With disability | 13 (0.8) |

| Gross annual household income in euros, 2019 [n (%)] | |

| 1,450 – 20,200 | 560 (34.4) |

| 20,200 – 35,200 | 559 (34.3) |

| 35,200 – 60,000 | 396 (24.3) |

| Over 60,000 | 113 (6.9) |

| Household composition [n (%)] | |

| Living alone | 210 (12.9) |

| Accompanied by one or more adults | 1,418 (87.1) |

| With children at home | 649 (39.9) |

| Housing conditions during confinement [n (%)] | |

| Makes it much harder | 93 (5.7) |

| Makes it a little harder | 337 (20.7) |

| Does not affect | 650 (39.9) |

| Makes it a little easier | 203 (12.5) |

| Makes it much easier | 345 (21.2) |

Previous Health Conditions. Participants were asked if they, or close relatives, had been infected by the SARS-CoV-2, had any pre-existing chronic health condition considered to be a risk factor for the virus (e.g., lung disease), were pregnant, or had a history of mental health difficulties for which they were treated.

Anxiety and Economic Threat-related to COVID-19. These two items were assessed by using a visual slider scale (ranging 0–100 and 0–10, respectively).

Increased Substance Use (ISU). Increases in the use of food, alcohol, cigarettes, psychotropic medication and drugs, during the confinement, were measured by a 5-item scale using a 4-point Likert scale.

The Pemberton Happiness Index (PHI; Hervás & Vazquez, 2013) is an integrative measure of well-being, including 11 items related to general hedonic, eudaimonic and social well-being on a scale that provides an overall well-being score. This scale has been validated in multiple countries, generally with good internal consistency (above α = 0.89).

The Openness to the Future Scale (OF; Botella et al., 2018). This 10-item scale assesses a positive attitude towards the future on a 5-point Likert scale with good psychometric properties in the general population (α = 0.87) and the clinical population (α = 0.82). An OF total score is calculated by adding all the item scores.

The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS, Smith et al., 2008) is a widely used 6-item self-report measuring the perceived ability to recover by using a 5-point Likert scale, with good psychometric properties in undergraduate students (α = 0.87) and excellent in the general population (α = 0.91). A total score is obtained by adding the item scores.

The Intolerance to Uncertainty Scale (IUS-short version; Carleton, Norton, & Asmundson, 2007) is a 12-item instrument scored on a 5-point Likert scale with excellent psychometric properties (α = 0.91). A total score is calculated by summing up the 12 items.

The Death Anxiety Inventory (DAI; Tomás-Sábado & Gómez-Benito, 2005) includes 17 items corresponding to five factors (i.e., externally generated death anxiety, meaning and acceptance of death, thoughts about death, life after death, and brevity of life), on a 5-point Likert scale with excellent internal consistency (α = 0.90). We selected five items (one per factor), which were added up providing a total death anxiety score.

The Three-item Loneliness Scale (TLS; Hughes, Waite, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, 2004). Respondents were asked on a 3-point Likert scale, how often they felt that they: lacked companionship; were left out; and were isolated from others. This scale has acceptable psychometric properties (α = 0.72). Individuals’ responses are summed up, with higher scores indicating greater loneliness.

Belongingness in Neighbourhood (BIN). This 3-item scale is adapted from the UK Community Life Survey (Cabinet Office, 2015) and rated on a 4-point Likert scale. One item was used to assess participants’ level of belongingness to their neighbourhood.

The Short-form Persecution and Deservedness Scale (SF-PaDS; McIntyre, Wickham, Barr, & Bentall, 2018) is a 5-item instrument that provides an overall measure of suspiciousness severity. Both the original scale and its adaptation (Valiente et al., 2020) have good reliability (α = 0.84; α = 0.85), respectively.

The Primals Inventory (PI; Clifton et al., 2019) is a 99-item instrument measuring major primal world beliefs, with excellent psychometric properties (α = 0.90) and test–retest stability. We used the six items corresponding to the PI-6 factor: perception of the goodness of the world, on a 6-point Likert scale. A total score is obtained by adding the item scores.

The Identification with all Humanity Scale (IWAH; McFarland, Webb, & Brown, 2012) is a 3-item questionnaire exploring respondents’ identification with people in your community; people from your country; and all humans everywhere. For the three groups the scale has good psychometric properties (α = 0.89; α = 0.83; α = 0.81), respectively. Response scale uses a 5-point Likert scale. An average total score was calculated for three subscales.

In this study, we used the median as the cut-off for the predictive variables since they did not have established cut-offs. Measures properties of all variables are depicted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reliability Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and descriptive statistics of measures of waves T1 and T2 (N = 1,628)

| Cronbach’s α |

T1 |

T2 |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | T1 | T2 | Test–retest | Mean | SD | Median | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| Psychological adjustment outcomes | ||||||||||||

| PHQ-9 | 0.888 | 0.897 | 0.86 | 6.32 | 5.58 | 5 | 0 | 27 | 6.69 | 5.65 | 0 | 27 |

| GAD-7 | 0.927 | 0.932 | 0.86 | 5.79 | 5.23 | 5 | 0 | 21 | 5.67 | 5.17 | 0 | 21 |

| ITQ severity | 0.890 | 0.898 | 0.80 | 4.72 | 4.98 | 3 | 0 | 24 | 5.01 | 5.14 | 0 | 24 |

| ITQ disturbance | 0.855 | 0.868 | 0.73 | 2.13 | 2.73 | 1 | 0 | 12 | 2.26 | 2.71 | 0 | 12 |

| Predictive variablesa | ||||||||||||

| ISU | 0.598 | - | - | 0.32 | 0.39 | 0.20 | 0 | 3 | - | - | - | - |

| PHI | 0.921 | - | - | 7.17 | 1.58 | 7.36 | 0 | 10 | - | - | - | - |

| OFS | 0.866 | - | - | 38.3 | 6.04 | 39 | 14 | 50 | - | - | - | - |

| BRS | 0.876 | - | - | 3.47 | 0.75 | 3.50 | 1 | 5 | - | - | - | - |

| IUS | 0.869 | - | - | 33.08 | 9.42 | 33.0 | 12 | 60 | - | - | - | - |

| DAI | 0.804 | - | - | 11.72 | 4.43 | 11.0 | 5 | 25 | - | - | - | - |

| TLS | 0.817 | - | - | 4.48 | 1.62 | 4.00 | 3 | 9 | - | - | - | - |

| BIN | - | - | - | 2.87 | 0.84 | 3 | 1 | 4 | - | - | - | - |

| SF-PaDS | 0.835 | - | - | 5.94 | 4.36 | 5.00 | 0 | 20 | - | - | - | - |

| PI-6 | 0.856 | - | - | 3.39 | 0.86 | 3.5 | 0 | 5 | - | - | - | - |

| IWAH | 0.863 | - | - | 3.78 | 0.63 | 3.77 | 1 | 5 | - | - | - | - |

Note: BIN: Belongingness in Neighbourhood; BRS: Brief Resilience Scale; DAI: The Death Anxiety Inventory; GAD-7: The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; ISU: Increases in Substance Use; ITQ: The International Trauma Questionnaire; IUS: The Intolerance to Uncertainty Scale; IWAH: The Identification with all humanity scale; OFS: The Openness to the Future Scale; SF-PADS: The Short-form Persecution and Deservedness Scale; PHI: The Pemberton Happiness Index; PHQ-9: The Patient Health Questionnaire-9; PI: The Primals Inventory; TLS: The Three-item Loneliness Scale; aPredictors were assessed only at T1.

2.2.2. Psychological adjustment outcomes

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002) is a 9-item scale assessing the severity of depressive symptoms over the last 2 weeks, with good internal reliability (α = 0.89) and excellent test–retest reliability. Responses are on a 4-point Likert scale. We used the suggested threshold of 10 (i.e., moderate levels of depression) as a cut-off.

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Löwe, 2006) was used whereby respondents were asked to report, on a 4-point Likert scale, on how often they were bothered by seven anxiety symptoms listed, in the past 7 days. We used the recommended cut-off of 10. This instrument has an excellent internal reliability (α = 0.92) and good test–retest reliability.

The International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ; Cloitre et al., 2018). A shortened version was used, including six items (i.e., two for each of the three post-traumatic stress clusters: re-experiencing, avoidance and sense of threat) and three items to assess the extent to which these symptoms impaired/disturbed daily functioning, with good psychometric properties (α = 0.79). Items were worded in relation to the COVID-19 and respondents used a 5-point Likert scale. A total post-traumatic stress severity score was generated by adding the six post-traumatic stress items. Since a score of ≥2 (moderately) is considered symptom ‘endorsement’, in this study, the severity cut-off was to have at least one symptom endorsed for each of the three post-traumatic stress symptom clusters. A total Disturbance score was computed by adding the three impairment items and was used as an additional dependent variable to ascertain the level of impairment in each of the psychological response pattern categories.

2.2.3. Patterns of psychological response over time

The presence of distress was conceptualized as meeting standard cut-off scores in depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD-7) or post-traumatic stress severity (ITQ). Although not of diagnostic value, this procedure allows for the identification of probable cases of psychological disorders. Then, a mental health status classification was carried out by first, categorizing individuals according to whether they exhibited absence/presence of distress (i.e., reaching cut-off scores for either depression, anxiety or post-traumatic responses) and second, taking into account the assessment time-point (i.e., T1 and T2). The combination of these two variables provided four different categories that tap the pattern of responses after traumatic events (Bonanno, 2004; Galatzer-Levy et al., 2018): a) Recovered (i.e., presence of distress at T1, absence at T2); b) Resilient (i.e., absence of distress at T1 and T2); c) Sustained distress (i.e., presence of distress at T1 and T2); and d) Delayed distress (i.e., absence of distress at T1, presence at T2). Scores for each variable by pattern of response and time of assessment are depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive data for each outcome measure by each psychological response pattern at Time 1 (T1) and Time 2 (T2) (N = 1,628)

| Variables scores |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 |

GAD-7 |

ITQ severity |

ITQ disturbance |

|||||

| Psychological response pattern | T1 M (SD) |

T2 M (SD) |

T1 M (SD) |

T2 M (SD) |

T1 M(SD) |

T2 M(SD) |

T1 M(SD) |

T2 M(SD) |

|

Recovered (N = 130) |

8.66 (4.9) |

4.85 (2.97) |

8.41 (4.64) |

4.36 (2.82) |

8.30 (4.39) | 3.45 (2.75) |

3.19 (2.74) | 1.62 (1.99) |

|

Resilient (N = 901) |

3.24 (2.93) |

3.52 (2.83) |

2.81 (2.66) |

2.70 (2.60) |

2.03 (2.41) | 2.03 (2.23) |

.81 (1.56) |

.91 (1.47) |

| Sustained distress (N = 395) | 12.64 (5.65) | 13.04 (5.73) |

12.08 (4.81) | 11.67 (4.91) | 10.3 (5.06) | 10.69 (5.13) | 4.82 (2.90) | 4.82 (2.95) |

| Delayed distress (N = 202) | 6.18 (3.13) |

963 (4.22) |

5.10 (2.77) |

7.98 (4.10) |

3.43 (2.65) | 8.14 (4.47) |

2.08 (2.36) | 3.63 (2.64) |

Note: M: mean; SD: standard deviation; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; ITQ: International Trauma Questionnaire; T1: first assessment point; T2: second assessment point.

2.3. Data analysis

Data were analysed using the SPSS v.22 (IBM Corp, 2013). To explore the differences in the level of disturbance, measured with an ITQ subscale, between the four categories, we conducted a 4 × 2 repeated-measures ANOVA, with a within-subject factor Time (T1, T2), and a between-subject factor Group (Resilient, Recovered, Delayed, Sustained distress). Multinomial logistic regression analyses were used to determine which health-related, psychological, interpersonal and socio-demographic variables predicted membership of the four psychological response patterns over time. Predictors were tested in two steps to preserve statistical power. First, four separated multinomial logistic regressions were run: one with the four health-related variables (i.e. pre-existing health condition, pregnancy, SARS-CoV-2 infection and history of mental health difficulties), one with the eight psychological variables (i.e. anxiety about the COVID-19 pandemic, economic threat due to COVID-19, increased substance use during confinement, intolerance to uncertainty, death anxiety, well-being, openness to the future and self-reported resilience), one with the six interpersonal variables (i.e. loneliness, perception of belonging, suspiciousness of others, religious identity, goodness of the world beliefs and identification with humanity) and one with the eight demographic and living conditions variables (i.e. sex, age, education, employment, income, urbanicity, living with children and housing conditions). Then, the predictors that were significant (<.05) in the first regressions were included in a final multinomial regression model.

3. Results

Sociodemographic and living condition characteristics are depicted in Table 1. The frequency of psychological response patterns over time is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Psychological response patterns defined by changes over time; sample and percentages (N = 1,628)

| Clinically significant symptoms Time two |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Absent | Present | ||

|

Clinically significant symptoms Time one |

Absent |

Resilient N = 901, 55.3% |

Delayed distress N = 202, 12.4% |

| Present |

Recovered N = 130, 8.0% |

Sustained distress N = 395, 24.3% |

|

Note: Categories are based on established cut-off scores on measures of either depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD-7), or traumatic stress-related symptoms (ITQ).

3.1. Level of disturbance among psychological response patterns over time

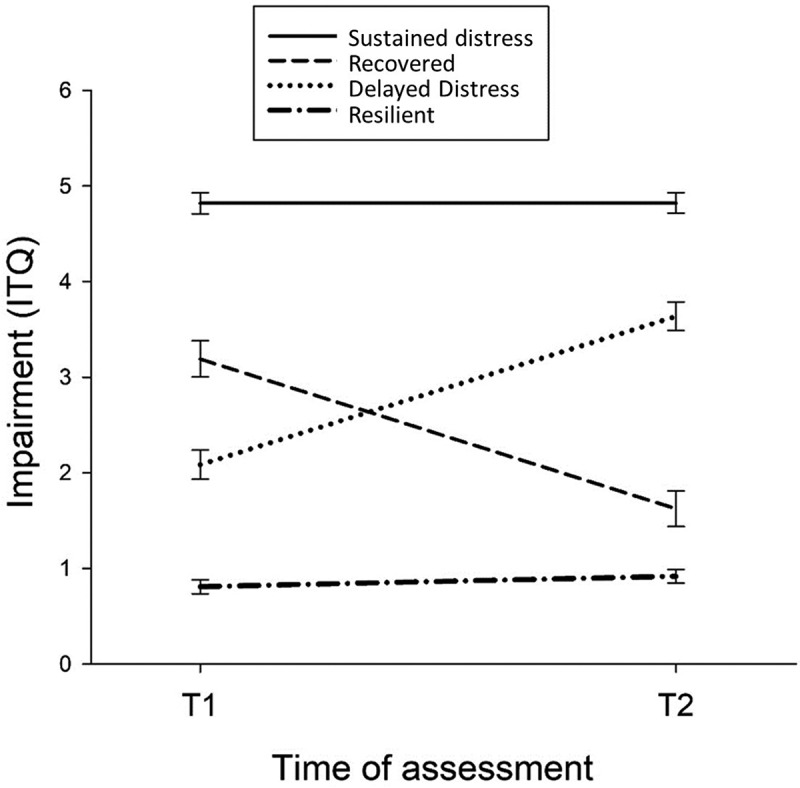

The overall level of impairment, as measured by the disturbance score provided in the ITQ, in the four psychological patterns over time, is depicted in Figure 1. There was a significant main effect of Group [F (1,1624) = 2359.26, p = <0.001, η2 = .592]. Yet, this effect was qualified by a significant Group × Time interaction [F (3, 1624) = 45.23, p < 0.001, η2 = .077]. Post hoc tests revealed significant differences (all p values <0.001) showing that the Recovered group had less impairment in T2 than in T1 and the Delayed group showed the opposite time-pattern. However, the Resilient and Sustained distress group did not show change across T1 and T2 (see Figure 1.)

Figure 1.

Psychological response patterns of each category over time

3.2. Psychological response patterns predicting variables

The final multinomial logistic regression analysis (see Table 5) identified age, history of mental health difficulties, COVID-19 anxiety and economic threat, increased substance use, well-being, intolerance to uncertainty, death anxiety, loneliness, suspiciousness and identification with humanity as significant predictors of a resilient response to the pandemic. The full model was a significant improvement in fit over a null model [χ2 (57) = 854.990, p < .001]. Both the Pearson’s chi-square test and the Deviance chi-square indicated good fit [χ2 (4770) = 4644.943, p = .901; χ2 (4770) = 2810.631, p = 1]. The Nagelkerke pseudo-R-square values indicated that 45.7 of the overall variance was explained.

Table 5.

Multinomial logistic regression estimates for predictors of psychological response patterns over time

| Resilient vs. |

Recovered vs. |

Delayed |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recovered |

Delayed |

Sustained distress |

Delayed |

Sustained distress |

Sustained distress |

|||||||||

| Estimate | S.E. | Estimate | S.E. | Estimate | S.E. | Estimate | S.E. | Estimate | S.E. | Estimate | S.E. | |||

| Demographic and living conditions variables | ||||||||||||||

| Sex | −0.31 | 0.73 | −0.10 | 0.90 | −0.40* | 0.67 | 0.21 | 1.24 | −0.09 | 0.91 | −0.30 | 0.74 | ||

| Age | −0.21** | 0.81 | −0.23** | 0.80 | −0.26** | 0.78 | −0.02 | 0.98 | −0.05 | 0.96 | −0.03 | 0.97 | ||

| Living with children | 0.04 | 1.04 | −0.34 | 0.71 | 0.16 | 1.18 | −0.38 | 0.69 | 0.12 | 1.13 | 0.50* | 1.65 | ||

| Housing conditions | 0.33 | 1.39 | −0.09 | 0.92 | −0.08 | 0.93 | −0.41 | 0.66 | −0.40 | 0.67 | 0.01 | 1.01 | ||

| Health-related variables | ||||||||||||||

| Pre-existing health condition | 0.40* | 1.49 | 0.01 | 1.01 | 0.06 | 1.06 | −0.39 | 0.68 | −0.34 | 0.71 | 0.05 | 1.05 | ||

| Previous mental health difficulties | −0.11 | 0.90 | 0.24 | 1.27 | 0.63** | 1.88 | 0.35 | 1.41 | 0.74** | 2.10 | 0.40 | 1.49 | ||

| Psychological variables | ||||||||||||||

| Anxiety about COVID-19 | 1.18** | 3.25 | 0.89** | 2.43 | 1.57** | 4.79 | −0.29 | 0.75 | 0.39 | 1.47 | 0.68** | 1.97 | ||

| Economic threat due to COVID-19 | −0.05 | 0.95 | 0.46** | 1.59 | 0.81** | 2.24 | 0.51* | 1.67 | 0.86** | 2.36 | 0.34 | 1.41 | ||

| Increased substance use | 0.97** | 2.63 | 0.84** | 2.32 | 1.43** | 4.17 | −0.13 | 0.88 | 0.46* | 1.58 | 0.59** | 1.80 | ||

| Intolerance of uncertainty scale | 0.52* | 1.68 | 0.49** | 1.63 | 0.86** | 2.37 | −0.03 | 0.97 | 0.35 | 1.42 | 0.38 | 1.46 | ||

| Death Anxiety Inventory | 0.36 | 1.44 | 0.15 | 1.17 | 0.82** | 2.27 | −0.21 | 0.81 | 0.46* | 1.58 | 0.67** | 1.94 | ||

| The Pemberton Happiness Index | 0.37 | 1.44 | −0.45* | 0.64 | −0.40* | 0.67 | −0.82** | 0.44 | −0.76** | 0.47 | 0.05 | 1.06 | ||

| Brief Resilience Scale | −0.20 | 0.82 | −0.27 | 0.76 | −0.35 | 0.71 | −0.08 | 0.93 | −0.15 | 0.86 | −0.07 | 0.93 | ||

| Interpersonal variables | ||||||||||||||

| The Three-item Loneliness Scale | 0.71** | 2.04 | 0.66** | 1.94 | 0.86** | 2.36 | −0.05 | 0.95 | 0.14 | 1.16 | 0.20 | 1.22 | ||

| Belongingness in Neighbourhood | 0.36 | 1.43 | 0.22 | 1.24 | 0.36 | 1.46 | −0.14 | 0.87 | 0.00 | 1.01 | 0.14 | 1.15 | ||

| Suspiciousness (SF-PaDS) | 0.82** | 2.27 | 0.39* | 1.48 | 0.75** | 2.11 | −0.43 | 0.65 | −0.07 | 0.93 | 0.36 | 1.43 | ||

| Religiousness | 0.43* | 1.5 | 0.16 | 1.17 | 0.16 | 1.16 | −0.27 | 0.76 | −0.27 | 0.76 | 0.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Goodness of the world (PI-6) | 0.03 | 1.03 | 0.20 | 1.23 | −0.15 | 0.86 | 0.17 | 1.18 | −0.18 | 0.83 | −0.35 | 0.70 | ||

| Identification with Humanity Scale | 0.15 | 1.16 | 0.20 | 1.23 | 0.59** | 1.81 | 0.05 | 1.06 | 0.44* | 1.56 | 0.39* | 1.47 | ||

Note: SF-PaDS: The Short-form Persecution and Deservedness Scale; PI-6: The Primals Inventory. *p < 0.001; **p < 0.01.

3.2.1. Resilience vs. sustained distress

Compared to the resilient group, the probability of having sustained distress was significantly higher for younger people, females, and respondents with previous mental health difficulties or with a high level of identification with humanity.

3.2.2. Resilience vs. delayed and sustained distress

Compared to the resilient group, the probability of having a delayed or sustained distress was significantly higher for those respondents with higher levels of anxiety about the COVID-19 or worry about its economic consequences, increased substance use during confinement, as well as those with higher scores of intolerance to uncertainty, loneliness and suspiciousness. On the contrary, higher levels of well-being were associated with a decreased probability of having delayed or sustained distress compared to those classified as resilient.

3.2.3. Resilience vs. recovery

The probability of being classified as recovered was significantly higher for younger people, and for those with pre-existing health conditions, an increased substance use, higher levels of COVID-19 anxiety, intolerance to uncertainty, loneliness and suspiciousness. Interestingly, people that identified themselves as religious had also an increased probability to be classified as recovered compared to resilient people.

3.2.4. Sustained distress vs other categories

It is remarkable that people that recovered were more likely to experience higher levels of well-being at T1 than those with delayed or sustained distress. Also, in comparison to those with delayed responses, respondents that had children, identification with humanity, had higher scores of death anxiety, increased substance use and COVID-19 anxiety were more likely to experience sustained distress.

4. Discussion

By combining the identification of the presence/absence of distress, established by cut-off scores in instruments measuring depression (PHQ-9), anxiety (GAD-7), and post-traumatic symptoms (ITQ) at two different times-points, we identified cases of resilience, sustained distress, delayed distress, and recovery in a national representative sample exposed to the COVID-19. The ANOVA results and post-hoc analyses provided strong initial support to the symptom-based fourfold distinction (see Figure 1) based on previous categorizations (Bonanno, 2004).

A review of longitudinal studies (Galatzer-Levy et al., 2018), has recognized that resilience responses to traumatic events are the most common pattern over time across populations (average of 65.7% vs. 55.3% in our study), followed by recovery (20.8% vs. 8.0% in our study), chronic (10.6% vs. 24.3% in our study) and delayed responses (8.9% vs. 12.4% in our study). Consistently, we found a relatively higher proportion of individuals with a resilient profile. However, compared to those data, we found less recovery and more significant distress (either sustained or delayed onset) in our sample. These differences could be explained by the fact that our two assessments were conducted during the forced confinement with only 1-month lag between them. The duration of the pandemic, without a clearly defined end, may also be a factor in determining a pattern of response that appears to be less resilient, overall. In fact, it has been shown that sustained distress had higher prevalence rates for chronic events (Galatzer-Levy et al., 2018). The unprecedented scale of the event and lack of preparedness may have contributed to an increase in delayed distress responses. Research has found that there is more resilience and better psychological adjustment when the person has received training and is well prepared for the potential trauma (Mobbs & Bonanno, 2018). A recent review points out that it is possible to avoid the long-lasting effects of COVID-19 quarantine by providing, in addition to enough supplies, a clear rationale for it and information about protocols (Brooks et al., 2020). In any case, our results might also indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic, due to the complex interactions of multiple stressors (e.g., home quarantines, social distance, loss of jobs, additional loads in caring of children or dependent relatives, health-related threats, etc.), may have unexpected lasting negative effects in the population (Horesh & Brown, 2020). Although it is well known that resilience is the most common psychological pattern in facing adverse life circumstances (Santiago et al., 2013), the relatively high rates of individuals with either sustained or delayed stress in our population study seem to warn that we are facing serious mental health challenges in this new scenario.

The last aim was to identify predictors of psychological response patterns which may also contribute to the validity of this symptom-based classification of resilience and the rest of psychological response patterns. Our results showed that the main variables increasing the probability of resilience to COVID-19 were being male, older, having no history of mental health difficulties, higher levels of psychological well-being and high identification with all humanity. Also, having lower levels in several variables (i.e. anxiety and economic threat due to COVID-19, substance use during the confinement, intolerance to uncertainty, death anxiety, loneliness, and suspiciousness) was a significant predictor of a resilient response to COVID-19.

Contrary to what was found in previous studies (Campbell-Sills et al., 2009), demographic factors such as, in our case, years of education, employment, income, urbanicity, living with children and housing conditions were not significant predictors of resilience, except for age and sex. In relation to the age effect, some studies have found that age is a curvilinear predictor factor of resilience, where younger and older populations are more vulnerable (e.g., Bonanno & Diminich, 2013). However, in our study, we found that older age was a significant linear predictor of resilience in comparison to all other psychological response patterns. Other studies have also found that younger individuals, in comparison with older adults, have been particularly affected by the pandemic in terms of psychopathological symptoms (Valiente et al., 2020.; Shevlin et al., 2020). There were no age differences among the three non-resilient groups. Sex only allowed distinguishing between those who had a resilience pattern and those who had a sustained stress pattern. Our results are in line with Bonanno and Diminich (2013), indicating that, compared to the sustained distress group, males were more likely to be classified as resilient. This supports the existence of some important gender-related differences in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., Adams-Prassl, Boneva, Golin, & Rauh, 2020; Ausín, González-Sanguino, Castellanos, & Muñoz, 2020).

Surprisingly, physical health-related variables associated with COVID-19 were not significantly related to resilience. However, our findings indicated that, compared to the sustained distress group, people without previous mental health difficulties were more likely to be classified as resilient or as recovered. So, previous mental health difficulties seem to have been a vulnerability risk factor for psychological distress during the pandemic. Other studies have found that pre-pandemic emotional distress was the strongest predictor of during-pandemic psychological adjustment difficulties (Shanahan et al., 2020). Related to this issue, our results confirmed, as hypothesized, the important predictive role of psychological factors (Galatzer-Levy et al., 2018). We found that lowered perception of threat (i.e., anxiety about COVID-19 and its economic consequences) and tolerance to uncertainty was associated with resilience but not with the other psychological response patterns. Using other psychological predictors, for other types of traumatic events, Fritz et al. (2018) identified variables associated with emotional stability, such as high self-esteem and absence of rumination, as significant predictors of resilience (see also, García, Cova, Rincón, & Vázquez, 2015). Interestingly, our results supported the idea that well-being is a relevant factor related to the concept of resilience. A high level of hedonic, eudaimonic and social well-being in T1 was associated with a pattern of resilience compared to delayed and sustained distress patterns over time. Enhanced well-being was also associated with recovery in comparison with the two distress patterns. Thus, psychological well-being could be a potential compensating and protection mechanism for preserved mental health (Fredrickson & Joiner, 2002). Yet not all positive variables had the same impact on resilience. Contrary to what has been found in relation to optimism (e.g., Galatzer-Levy & Bonanno, 2014), a positive orientation to the future did not have an effect on psychological patterns over time in our study. It is possible that tending to look positively to the future has a scarce effect in the current context of extremely high uncertainty in relation to almost any health or economic aspect. Moreover, it is noteworthy that self-reported perception of resilience (measured with the BRS) did not predict resilience in the final model of our study. Despite the popularity of self-report questionnaires of resilience (Windle et al., 2011), their predictive value seems very small at best as has been cogently argued by Bonanno (2012). It is likely that measuring resilience with a self-report instrument (i.e., the BRS), or with a permanent absence of significant symptoms of psychology, could represent different constructs that may tap complementary perspectives on resilience. Further studies on the predictive and incremental validity of both approaches are needed to discern their utility in the context of the current pandemic.

Regarding interpersonal variables, our results were partially in line with the past literature. Several studies have shown that good social networks are relevant predictors of both trauma-related responses (Brewin, Andrews, & Valentine, 2000) and resilience (e.g., Fritz et al., 2018). In this line, we found that loneliness decreased the likelihood of being classified as resilient but increased the probability of being classified in the recovered, delayed or sustained distress groups. Likewise, we found that suspiciousness, which is associated to a lack of interpersonal trust and low levels of perceived social support (Lamster, Lincoln, Nittel, Rief, & Mehl, 2017), was a risk factor to experience sustained distress in the current pandemic and decreased the chance of being classified as resilient, which is in line with the findings by Vazquez et al. (2021). Likewise, other studies have highlighted the role of social support factors in predicting resilience over time after traumatic events (Butler et al., 2009).

Paradoxically, we also found that identification with humanity was also a risk factor to experience sustained distress in comparison with the rest of the psychological response patterns. This concept relates to higher levels of concern and supportive behaviour towards the disadvantaged, a stronger endorsement of human rights, and stronger responses in favour of global harmony (McFarland et al., 2012). Thus, although it could be conceptualized as a humane and nurturing characteristic of a person, it could also be a source of distress in the context of a potentially traumatic event where being sensitive towards other people may increase overall anxiety and concern about the pandemic and its consequences (Vazquez et al., 2021).

The current study has several strengths and limitations. We used a representative sample from a national population, which has been relatively uncommon in the initial series of studies published on the mental health consequences of the pandemic (Nieto, Navas, & Vázquez, 2020). Also, keeping a substantial response rate between T1 and T2 must be considered as an asset of the study. Second, the inclusion of two points of assessment allowed the analysis of a psychological adjustment from a dynamic approach, as supported by Bonanno (2012), rather than relying on a cross-sectional perspective of the patterns of responses. The two assessment points were coincidental with high levels of exposure to the event (i.e., very high rates of infected people and deceased by the COVID-19) while respondents were still mandatorily confined. Also, a strength of the design was that the selected measures, through instruments with sound psychometric properties, tapped common variables explored in trauma-related studies (e.g., depression, anxiety, or post-traumatic stress symptoms) but also some selected variables that were thought to be specifically related to the psychosocial and political context of the current pandemic (e.g., ideas of suspiciousness, loneliness, feelings of being connected with humanity). Nevertheless, several limitations need to be acknowledged. First, all instruments were based on self-report and thereby, inferences on the participants’ clinical status must be taken with caution since we used standard cut-off scores and not clinical criteria (Drummond, 2020) which, nevertheless, has been the norm in studies exploring the mental health consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic (see the systematic review by Pappa et al., 2020). Furthermore, the presence of symptoms does not equate a diagnosable condition and self-report measures can significantly overestimate its prevalence (Levis et al., 2020). Second, it is worth mentioning that the current study focuses on psychological response patterns to the COVID-19 pandemic, a unique and hard to predict adverse circumstance that presents a complex combination of stressors and blocks access to protective factors (Gruber et al., 2020). Thus, we must be cautious when generalizing these results to other types of adverse circumstances. Moreover, some of the predictive factors of the psychological response patterns (e.g. “economic threat due to COVID-19”) are also factors that may contribute to the severity of the event itself (Boyraz & Legros, 2020). Third, we do not have baseline data on the participants’ mental health status and symptoms of distress could simply reflect, at least in some cases, previous levels of distress. Forth, the use of three alternative criteria in defining significant distress (i.e., depression or anxiety or post-traumatic stress), might inflate the figures of distressed individuals. Yet, we used that approach to maximize the sensitivity of our results. Finally, there were only two time points, which do not allow for the identification of the entire response trajectory and could therefore conflate recovery and chronic distress profiles (Galatzer-Levy & Bonanno, 2014). Moreover, we did not incorporate the positive aspects of functioning in our definition of resilience and used a more straightforward symptom-based definition.

Although we have identified many sociodemographic and psychological variables as predictors of psychological response patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic, some of the variables found in this study were not reflected in the previous literature. Therefore, in line with Chen and Bonanno (2020), there is a need for more studies that address long-term mental health patterns and integrate the multiple variables that help individuals develop a resilient response. Future research should adopt longitudinal designs with sufficient measurement times to be able to compare and draw conclusions about the results on the dynamics of resilience. Given this new situation, there is a need for new ways of thinking about, and researching, crises, as discussed in (Horesh & Brown, 2020). It is also necessary to disentangle, in future studies, the complex interplay of multiple and changing variables (e.g., Boyraz & Legros, 2020). For example, the use of procedures such as experience sampling methods (e.g., Gelkopf, Lapid Pickman, Carlson, & Greene, 2019) would provide a dynamic perspective for studying the pattern of response when facing with a global pandemic.

In conclusion, our results contribute to the current interest of conceptualizing resilience as a complex process that might benefit both going beyond simple trait-like questionnaires of resilience and incorporating measures of well-being to better predict resilience. Our results seem encouraging to adopt more ambitious definitions and more complex designs and methodologies to capture the dynamic essence of adaptation to life adversities in a crisis that opens new public mental health challenges that need to be adequately addressed (Brewin, DePierro, Pirard, Vazquez, & Williams, 2020).

Acknowledgments

We thank Jamie O’Grady for his help in editing the paper.

Funding Statement

This research was supported, in part, by grants from the Ministry of Science and Innovation [PSI2016-74987-P and PID2019-108711GB-I00] and the Instituto de Salud Carlos III COVID-19 Instituto de Salud Carlos III grants [COV20/00737-CM] and funds from the UCM for consolidated research groups [GR29/20]. Almudena Trucharte had a UCM doctoral fellowship [CT42/18] and Vanesa Peinado had a Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness doctoral Fellowship [BES-2017082015].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest.

Data availability

The data of the study are publicly available at https://zenodo.org/record/4126984#.X5bHgogza5h (doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4126983)

References

- Adams-Prassl, A., Boneva, T., Golin, M., & Rauh, C. (2020). Inequality in the impact of the coronavirus shock: Evidence from real time surveys. Journal of Public Economics, 189, 104245. [Google Scholar]

- Ausín, B., González-Sanguino, C., Castellanos, M. Á., & Muñoz, M. (2020). Gender-related differences in the psychological impact of confinement as a consequence of COVID-19 in Spain. Journal of Gender Studies, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/09589236.2020.1799768 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G. A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extremely aversive events? American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G. A. (2012). Uses and abuses of the resilience construct: Loss, trauma, and health-related adversities. Social Science and Medicine, 74(5), 753–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G. A., & Diminich, E. D. (2013). Annual research review: Positive adjustment to adversity–trajectories of minimal–impact resilience and emergent resilience. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(4), 378–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G. A., Galea, S., Bucciarelli, A., & Vlahov, D. (2006). Psychological resilience after disaster: New York City in the aftermath of the September 11th terrorist attack. Psychological Science, 17(3), 181–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G. A., Galea, S., Bucciarelli, A., & Vlahov, D. (2007). What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(5), 671–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G. A., Pat-Horenczyk, R., & Noll, J. (2011). Coping flexibility and trauma: The perceived ability to Cope with Trauma (PACT) scale. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 3(2), 117–129. [Google Scholar]

- Bonanno, G. A., Rennicke, C., & Dekel, S. (2005). Self-Enhancement among high-exposure survivors of the September 11th terrorist attack: Resilience or social maladjustment? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(6), 984–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botella, C., Molinari, G., Fernández-Álvarez, J., Guillén, V., García-Palacios, A., Baños, R. M., & Tomás, J. M. (2018). Development and validation of the openness to the future scale: A prospective protective factor. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 16(1), 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyraz, G., & Legros, D. N. (2020). Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and traumatic stress: Probable risk factors and correlates of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 25(6–7), 503–522. [Google Scholar]

- Brewin, C. R., Andrews, B., & Valentine, J. D. (2000). Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 68(5), 748–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewin, C. R., DePierro, J., Pirard, P., Vazquez, C., & Williams, R. (2020). Why we need to integrate mental health into pandemic planning. Perspectives in Public Health, 140(6), 309–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, G. W., Bifulco, A., & Harris, T. O. (1987). Life events, vulnerability and onset of depression: Some refinements. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 150(1), 30–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, L. D., Koopman, C., Azarow, J., Blasey, C. M., Magdalene, J. C., DiMiceli, S., … Spiegel, D. (2009). Psychosocial predictors of resilience after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197(4), 266–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office . (2015). Community life survey technical report 2014-15.

- Campbell-Sills, L., Forde, D. R., & Stein, M. B. (2009). Demographic and childhood environmental predictors of resilience in a community sample. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(12), 1007–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton, R. N., Norton, M. P. J., & Asmundson, G. J. (2007). Fearing the unknown: A short version of the intolerance of uncertainty scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(1), 105–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S., & Bonanno, G. A. (2020). Psychological adjustment during the global outbreak of COVID-19: A resilience perspective. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(S1), S51–S54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifton, J. D., Baker, J. D., Park, C. L., Yaden, D. B., Clifton, A. B., Terni, P., … Schwartz, H. A. (2019). Primal world beliefs. Psychological Assessment, 31(1), 82–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloitre, M., Shevlin, M., Brewin, C. R., Bisson, J. I., Roberts, N. P., Maercker, A., … Hyland, P. (2018). The International Trauma Questionnaire: Development of a self-report measure of ICD-11 PTSD and complex PTSD. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 138(6), 536–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darves-Bornoz, J.-M., Alonso, J., de Girolamo, G., Graaf, R. D., Haro, J.-M., Kovess-Masfety, V., … Vilagut, G. (2008). Main traumatic events in Europe: PTSD in the European study of the epidemiology of mental disorders survey. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21(5), 455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drummond, L. M. (2020). Does coronavirus pose a challenge to the diagnoses of anxiety and depression? A view from psychiatry. BJPsych Bulletin, 1–3. doi: 10.1192/bjb.2020.102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2002). Positive emotions trigger upward spirals toward emotional well-being. Psychological Science, 13(2), 172–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz, J., de Graaff, A. M., Caisley, H., Van Harmelen, A.-L., & Wilkinson, P. O. (2018). A systematic review of amenable resilience factors that moderate and/or mediate the relationship between childhood adversity and mental health in young people. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galatzer-Levy, I. R., & Bonanno, G. A. (2014). Optimism and death: Predicting the course and consequences of depression trajectories in response to heart attack. Psychological Science, 25(12), 2177–2188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Huang, S. H., & Bonanno, G. A. (2018). Trajectories of resilience and dysfunction following potential trauma: A review and statistical evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 63, 41–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García, D., & Rimé, B. (2019). Collective emotions and social resilience in the digital traces after a terrorist attack. Psychological Science, 30(4), 617–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García, F. E., Cova, F., Rincón, P., & Vázquez, C. (2015). Trauma or growth after a natural disaster? The mediating role of rumination processes. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1), 26557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelkopf, M., Lapid Pickman, L., Carlson, E. B., & Greene, T. (2019). The dynamic relations among peritraumatic and posttraumatic stress symptoms: An experience sampling study during wartime. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(1), 119–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, J., Prinstein, M. J., Clark, L. A., Rottenberg, J., Abramowitz, J. S., Albano, A. M., … Weinstock, L. M. (2020). Mental health and clinical psychological science in the time of COVID-19: Challenges, opportunities, and a call to action. American Psychologist, 1–17. 10.1037/amp0000707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hervás, G., & Vazquez, C. (2013). Construction and validation of a measure of integrative well-being in seven languages: The Pemberton happiness index. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 11(1), 66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S. E., Palmieri, P. A., Johnson, R. J., Canetti-Nisim, D., Hall, B. J., & Galea, S. (2009). Trajectories of resilience, resistance, and distress during ongoing terrorism: The case of Jews and Arabs in Israel. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(1), 138–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horesh, D., & Brown, A. D. (2020). Traumatic stress in the age of COVID-19: A call to close critical gaps and adapt to new realities. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(4), 331–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infurna, F. J., & Luthar, S. S. (2018). Re-evaluating the notion that resilience is commonplace: A review and distillation of directions for future research, practice, and policy. Clinical Psychology Review, 65, 43–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalisch, R., Cramer, A. O., Binder, H., Fritz, J., Leertouwer, I. J., Lunansky, G., … Van Harmelen, A.-L. (2019). Deconstructing and reconstructing resilience: A dynamic network approach. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(5), 765–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes, C. L. (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. American Psychologist, 62(2), 95–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K., & Spitzer, R. L. (2002). The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals, 32(9), 509–515. [Google Scholar]

- Lamster, F., Lincoln, T. M., Nittel, C. M., Rief, W., & Mehl, S. (2017). The lonely road to paranoia: A path-analytic investigation of loneliness and paranoia. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 74, 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levis, B., Benedetti, A., Ioannidis, J. P. A., Sun, Y., Negeri, Z., He, C., … Thombs, B. D. (2020). Patient health questionnaire-9 scores do not accurately estimate depression prevalence: Individual participant data meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 122, 115–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride, O., Murphy, J., Shevlin, M., Gibson Miller, J., Hartman, T. K., Hyland, P., … Bentall, R. (2020). An overview of the context, design and conduct of the first two waves of the COVID-19 psychological research consortium (C19PRC) study. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1861 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland, S., Webb, M., & Brown, D. (2012). All humanity is my ingroup: A measure and studies of identification with all humanity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(5), 830–853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGiffin, J. N., Galatzer-Levy, I. R., & Bonanno, G. A. (2019). Socioeconomic resources predict trajectories of depression and resilience following disability. Rehabilitation Psychology, 64(1), 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, J. C., Wickham, S., Barr, B., & Bentall, R. P. (2018). Social identity and psychosis: Associations and psychological mechanisms. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(3), 681–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobbs, M. C., & Bonanno, G. A. (2018). Beyond war and PTSD: The crucial role of transition stress in the lives of military veterans. Clinical Psychology Review, 59, 137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, I., Navas, J. F., & Vázquez, C. (2020). The quality of research on mental health related to the COVID-19 pandemic: A note of caution after a systematic review. Brain, Behavior, & Immunity - Health, 7, 100123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappa, S., Ntella, V., Giannakas, T., Giannakoulis, V. G., Papoutsi, E., & Katsaounou, P. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 88, 901–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian, M., Wu, Q., Wu, P., Hou, Z., Liang, Y., Cowling, B. J., & Yu, H. (2020). Psychological responses, behavioral changes and public perceptions during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in China: A population based cross-sectional survey. MedRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Santiago, P. N., Ursano, R. J., Gray, C. L., Pynoos, R. S., Spiegel, D., Lewis-Fernandez, R., & Friedman, M. J. (2013). A systematic review of PTSD prevalence and trajectories in DSM-5 defined trauma exposed populations: Intentional and non-intentional traumatic events. PloS One, 8(4), e59236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, L., Steinhoff, A., Bechtiger, L., Murray, A. L., Nivette, A., Hepp, U., … Eisner, M. (2020). Emotional distress in young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence of risk and resilience from a longitudinal cohort study. Psychological Medicine, 1–10. doi: 10.1017/S003329172000241X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevlin, M., McBride, O., Murphy, J., Miller, J. G., Hartman, T. K., Levita, L., … Bentall, R. P. (2020). Anxiety, depression, traumatic stress and COVID-19-related anxiety in the UK general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open, 6(6), e125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B. W., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(3), 194–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwick, S. M., Bonanno, G. A., Masten, A. S., Panter-Brick, C., & Yehuda, R. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: Interdisciplinary perspectives. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 5(1), 25338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomás-Sábado, J., & Gómez-Benito, J. (2005). Construction and validation of the death anxiety inventory (DAI). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 21(2), 108–114. [Google Scholar]

- Ungar, M., & Theron, L. (2020). Resilience and mental health: How multisystemic processes contribute to positive outcomes. The Lancet Psychiatry, 7(5), 441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valiente, C., Contreras, A., Peinado, V., Trucharte, A., Martínez, A., & Vazquez, C. (2020). Psychological adjustment in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic: Positive and negative mental health outcomes in the general population. The Spanish Journal of Psychology. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez, C. (2013). A new look at trauma: From vulnerability models to resilience and positive changes. In Moore K. A., Kaniasty K., Buchwald P., & Sese A. (Eds.), Stress and anxiety: Applications to health and well-being, work stressors and assessment (pp. 27–40). Berlin: Logos Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez, C., Valiente, C., García, F. E., Contreras, A., Peinado, V., Trucharte, A., & Bental, R. P. (2021). Post-traumatic growth and stress-related responses during the COVID-19 pandemic in a national representative sample: The role of positive core beliefs about the world and others. Journal of Happiness Studies. 10.1007/s10902-020-00352-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Windle, G., Bennett, K. M., & Noyes, J. (2011). A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9(1), 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z., Galatzer-Levy, I. R., & Bonanno, G. A. (2014). Heterogeneous depression responses to chronic pain onset among middle-aged adults: A prospective study. Psychiatry Research, 217(1–2), 60–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data of the study are publicly available at https://zenodo.org/record/4126984#.X5bHgogza5h (doi: 10.5281/zenodo.4126983)