Abstract

Background

Targeted therapies for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) with oncogenic drivers have caused a paradigm shift in care. Biomarker testing is needed to assess eligibility for these therapies. Pulmonologists often perform bronchoscopy, providing tissue for both pathologic diagnosis and biomarker analysis. We performed this survey to define the existing knowledge and practices regarding the pulmonologists’ role in biomarker testing for advanced NSCLC.

Research Question

What is the current knowledge and practice of pulmonologists regarding biomarker testing and targeted therapies in advanced NSCLC?

Study Design and Methods

This cross-sectional study was performed using an electronic survey of a random sample of 7,238 pulmonologists. Questions focused on diagnostic steps and biomarker analyses for NSCLC.

Results

A total of 453 pulmonologists responded. Respondents vary by reported lung cancer patient volume, ranging from 51% evaluating one to four new cases per month to 19% evaluating > 10 cases per month. Interventional training, academic practice setting, and higher volume of endobronchial ultrasound with transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) were associated with increased knowledge of practice guidelines for the number of recommended passes during EBUS-TBNA (P < .05). Academic pulmonologists more commonly performed or referred for EBUS-TBNA than community pulmonologists (96% and 83%, respectively; P < .0005). Higher testing rates were associated with interventional training, academic setting, and the presence of an institutional policy, whereas lower testing rates were associated with general pulmonologists, practice in community settings, and lack of a guiding institutional policy (P < .05).

Interpretation

Substantial differences among pulmonologists’ evaluation of advanced NSCLC, variation in knowledge of available biomarkers and the importance of targeted therapies, and differences in institutional coordination likely lead to underutilization of biomarker testing. Interventional training appears to drive improved knowledge and practice for biomarker testing more than practice setting. Improvements are needed in tissue acquisition and interdisciplinary coordination to ensure universal and comprehensive testing for eligible patients.

Key Words: biomarker, endobronchial ultrasound with fine needle aspiration, non-small cell lung cancer, targeted therapies

Abbreviations: AP, academic pulmonologist; CHEST, American College of Chest Physicians; EBUS-TBNA, endobronchial ultrasound with transbronchial needle aspiration; FDA, Food and Drug Administration; IP, interventional pulmonologist; NSCLC, non-small cell lung cancer; ROSE, rapid on-site evaluation; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor; TMB, tumor mutation burden

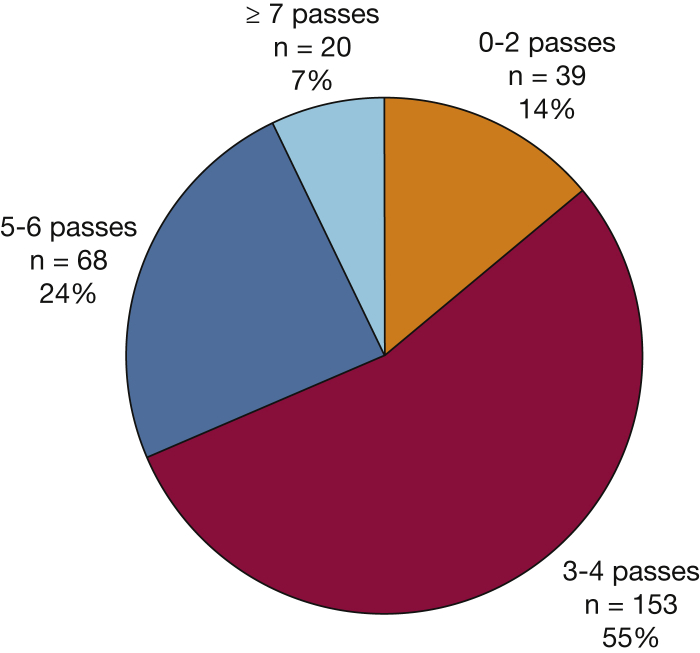

Graphical Abstract

Advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for more than one-half of new diagnoses of lung cancer in the United States. Although 5-year survivorship is generally poor, recent advances hold much promise.1,2 Until recently, advanced lung cancer was primarily treated with platinum-based combination therapies.3 After treatment with targeted therapy, 15% to 50% of patients with EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements survive > 5 years.4, 5, 6, 7 Such personalized therapy relies on identification of specific biomarkers.8 The current paradigm is to directly sample and test lung cancer tissue for biomarkers that indicate a targetable genetic mutation.

Erlotinib, an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), was the first targeted therapy to gain permanent US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2013 after it was shown to be superior to standard cytotoxic chemotherapy alone, in those with the mutation.9,10 EGFR TKIs have since been incorporated into society guidelines and have become the standard of care for eligible patients.11, 12, 13 Since the success of EGFR-targeted therapy, additional oncogenic drivers have been identified that can be effectively treated with targeted therapies. These include ALK or ROS1 rearrangements, BRAF V600E mutations, NTRK gene fusions, MET exon 14 skipping mutations, and RET rearrangements that have FDA-approved therapies and ERBB2/HER2 and KRAS p.G12C mutations that have therapies with FDA breakthrough therapy designations.13,14

Predictive markers are also important for identifying appropriate patients for immunotherapy. PD-L1 expression, mismatch repair deficiency, and tumor mutation burden (TMB) are predictive markers to help identify preferred patients for immunotherapy.15,16 Patients with PD-L1 expression > 50% are candidates for first-line immunotherapy alone.15 More biomarkers to aid in selection of targeted therapies and immunotherapy are under investigation and their numbers are expected to grow.8

The ongoing development of targeted treatments and immunotherapy for patients with lung cancer presents new challenges for pulmonologists. Endobronchial ultrasound with transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) can provide both a diagnosis and mediastinal lymph node stage for patients with suspected advanced NSCLC. It can be especially useful for those without evidence of extrathoracic metastasis and its use is supported by American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) guidelines.17 A meta-analysis showed that the pooled probability of obtaining a sufficient sample for identification of EGFR mutations by EBUS-TBNA was 94.5% (95% CI, 93.2%-96.4%).18 In addition to their role in acquiring tissue for testing, pulmonologists may also order biomarker testing. Pulmonologists are now being asked to collect adequate tumor tissue for testing, keep informed of biomarker testing indications, and collaborate with oncologists and pathologists to coordinate appropriate and timely biomarker testing.

However, studies show that biomarker testing is variably deployed and underused.19, 20, 21 Evidence suggests biomarker testing among patients with metastatic NSCLC may be as low as 10% to 20%, limiting potentially eligible patients to conventional therapies with shorter survival than those treated with effective targeted therapies.22,23 We undertook this study in collaboration with the American Cancer Society National Lung Cancer Roundtable and CHEST to better define pulmonologists’ practice patterns for tissue acquisition and knowledge of biomarkers, targeted therapies, and immunotherapy in the setting of newly diagnosed advanced NSCLC.

Study Design and Methods

The survey instrument was developed by lung cancer experts (G. A. S., J. R. J., U. B. R., J. C. K., N. M., and R. A. S.) from a subgroup of the National Lung Cancer Roundtable Triage for Appropriate Treatment Task Group in 2018. The entire group consisted of three pulmonologists specializing in thoracic oncology, three people from patient advocacy groups, and two epidemiologists. Questions focused on key domains for pulmonologists including clinical volume, tissue sampling methods, responsible party for ordering biomarker testing, and knowledge of available biomarkers and FDA-approved targeted therapies. There were a total of 38 items which included multiple choice and Likert scale questions (see e-Appendix 1 for complete questionnaire).

Pilot testing of the survey was performed by nine volunteer physicians, one thoracic surgery fellow, and eight pulmonary fellows, at the Medical University of South Carolina. Participants were asked to provide feedback on issues they encountered as they completed the survey with specific attention to unclear language or response options that did not match their possible answers. Comments from the pilot test were reviewed by the members of the expert panel, and edits were made to the instrument before final deployment. Data collection and analysis were conducted by CHEST analytics in a deidentified format. This study was designated as exempt from the institutional review board at the Medical University of South Carolina.

The CHEST analytic database is composed of 25,237 physicians in the United States, 14,208 of whom are pulmonologists. A total of 7,238 pulmonologists in the CHEST analytic database were randomly generated and invited to participate. E-mail invitations were delivered in April and May 2019. The initial invitation explained the goals of the study and provided a link to the survey. Each invitee was contacted up to an additional two times via reminder e-mails over 10 days. The invitational e-mails communicated an incentive $50 gift card for completion of the survey.

Descriptive statistical analyses are presented in the form of frequency tables of responses to the questionnaire by all respondents. Inferential statistical analysis was performed using χ2 test, Fisher exact test, and the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, as appropriate, to measure the strength of associations and to make comparisons of responses by pulmonologist practice setting, subspecialty training, volume of EBUS-TBNA, and presence of an institutional policy for handling biomarkers. When multiple comparisons were made, post hoc χ2 testing was used. A comparison of responders and nonresponders was performed to assess for possible nonresponse bias (e-Table 1).

Results

Respondent Demographics and Practice Profile

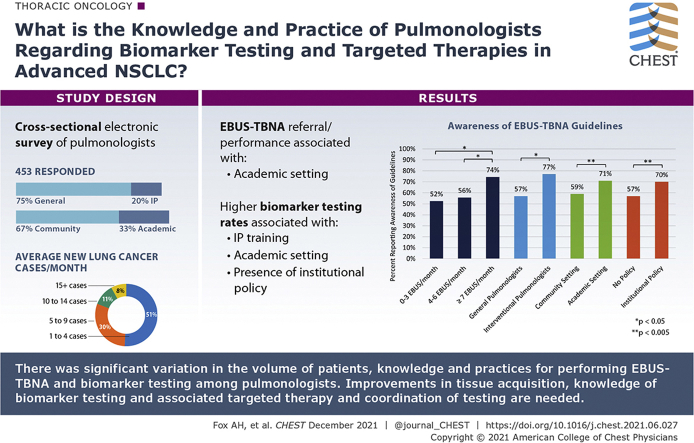

A total of 453 pulmonologists (6.3%) responded to the survey. Most respondents were male (73%), white (58%), general pulmonologists (75%) who worked in a community setting (67%) and who predominantly spent time in clinical care of patients (Table 1). There were no significant differences in outcomes (eg, awareness of biomarkers with available targeted therapies, awareness of guidelines of the number of passes to make during EBUS-TBNA) based on age or practice tenure. Interventional pulmonologists (IPs) comprised 20% of all respondents, 59% of whom worked in an academic practice setting. IPs represent 36% of pulmonologists in academic settings and 12% of those in the community. Breakdown of both practice setting and presence of interventional training for selected outcomes provide insight into their relative contributions on outcomes (e-Table 2). Reported volume of lung cancer cases per month was variable among providers in different practice settings and types of training (Fig 1). About one-half (51%) reported seeing only one to four patients with new diagnoses of lung cancer per month. In contrast, a substantial group (19%) saw > 10 new cases per month. IPs reported higher volumes of newly diagnosed lung cancer cases per month than general pulmonologists.

Table 1.

Demographics and Practice Characteristics of Survey Respondents

| Variable | No. of Respondents (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (n = 287), y | |

| < 40 | 62 (22) |

| 40-50 | 108 (38) |

| 51-60 | 70 (24) |

| 61-80 | 47 (16) |

| Sex (n = 288) | |

| Male | 210 (73) |

| Female | 61 (21) |

| Declined to answer | 17 (6) |

| Race (n = 290) | |

| White | 168 (58) |

| Black | 2 (1) |

| Asian | 76 (26) |

| Other | 4 (1) |

| Declined to answer | 40 (14) |

| Hispanic or Latino heritage (n = 288) | |

| Yes | 19 (7) |

| No | 234 (81) |

| Declined to answer | 35 (12) |

| Region of practice (n = 287) | |

| West | 44 (15.5) |

| Midwest | 63 (22) |

| South | 116 (40.5) |

| Northeast | 64 (22) |

| Specialty (N = 453) | |

| General pulmonologist | 341 (75) |

| Interventional pulmonologist | 91 (20) |

| Intensivist | 21 (5) |

| Practice setting (N = 453) | |

| Academic | 148 (33) |

| Community | 305 (67) |

| Practice setting and subspecialty training (N = 453) | |

| General/academic | 94 (20.7) |

| General/community | 268 (59.2) |

| Interventional/academic | 54 (11.9) |

| Interventional/community | 37 (8.2) |

| Length of time in practice (n = 288), y | |

| ≤ 10 | 130 (45) |

| 11-30 | 129 (45) |

| 31-50 | 29 (10) |

| Reported % clinical time (n = 288) | |

| < 50 | 10 (3) |

| 50-74 | 28 (10) |

| > 74 | 250 (87) |

| Average No. of new lung cancer cases diagnosed per month (N = 453) | |

| 1-4 | 230 (51) |

| 5-9 | 137 (30) |

| 10-14 | 48 (11) |

| ≥ 15 | 38 (8) |

| Which of the following biopsy/tissue sampling techniques do you perform most often with your patients (regardless of whether you perform the actual procedure)? (N = 453) | |

| EBUS-TBNA | 397 (87) |

| Transthoracic needle biopsy | 326 (72) |

| Surgical specimen | 147 (32) |

| Mediastinoscopy | 110 (24) |

| Do you perform EBUS-TBNA to provide a cancer diagnosis and stage? (N = 453) | |

| Performs EBUS-TBNA themselves | 280 (62) |

| Refers to another provider | 174 (38) |

EBUS-TBNA = endobronchial ultrasound with transbronchial needle aspiration.

Figure 1.

A, Number of new diagnoses of lung cancer per month for all survey respondents. B, Breakdown of the number of new lung cancer diagnoses per month by practice setting and interventional training.

EBUS-TBNA Practices

Most pulmonologists (93%) thought that determining the cell type of lung cancer was important or very important. For diagnostic and staging purposes, the most common method of tissue sampling was either EBUS-TBNA (87%) or transthoracic needle aspiration (72%). Respondents who reported themselves as academic pulmonologists (APs) were significantly more likely to choose EBUS-TBNA as their most common diagnostic technique (96%) compared with community pulmonologists (83%; P < .0005). Almost two-thirds (62%) of all pulmonologists in the study performed EBUS-TBNA procedures. APs were more likely to perform EBUS-TBNA than community pulmonologists (71% vs 57%, respectively; P = .004). All IPs performed EBUS-TBNA compared with 52% of general pulmonologists (P < .005). IPs performed more EBUS-TBNA procedures than general pulmonologists (P < .001). Of those who performed EBUS-TBNA, most (74%) IPs performed > 10 per month, whereas most (77%) generalists performed six or fewer per month. Nearly one-quarter (22%) of all providers performed three or fewer EBUS-TBNA procedures per month.

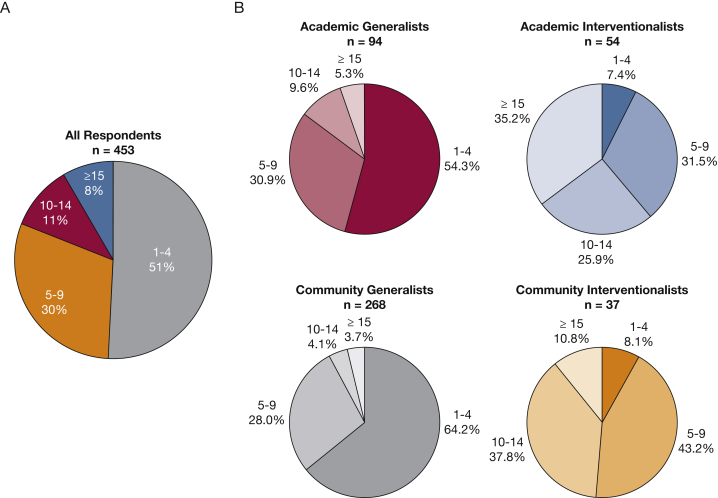

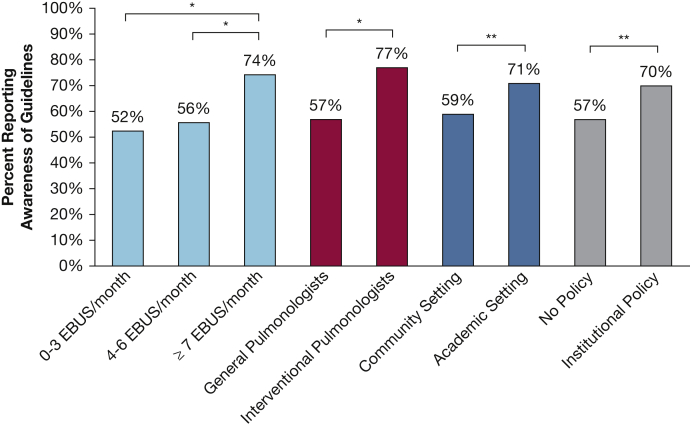

Knowledge and practice characteristics for performing EBUS-TBNA by providers are summarized in e-Table 3. Most providers (80%) who performed EBUS-TBNA reported they followed a national societal guideline for technique.24 However, only 63% reported awareness of guidelines, which suggest a minimum of three passes per sampling site, especially when rapid on-site evaluation (ROSE) is unavailable. Providers who have interventional training, practice in academic settings, and/or performed seven or more EBUS-TBNA procedures per month had higher rates of knowledge for guidelines and for the number of passes recommended during EBUS-TBNA (Fig 2). Variation was found in the number of extra needle passes per site to obtain tissue for molecular analysis (Fig 3). More than one-half (55%) reported that they usually performed three or four passes to collect tissue for biomarker analysis, 31% reported five or more passes, and 14% reported fewer than three passes. There was general agreement (90%) that the number of passes made was determined by confidence that enough tissue was collected for molecular analysis. Although only a minority of respondents cited needle gauge as a determining factor for number of passes taken during EBUS-TBNA, general pulmonologists were more likely to do so than IPs (16% vs 8%, respectively; P = .058). Most (84%) reported access to ROSE, which was more often available to IPs than general pulmonologists (98% and 77%, respectively; P < .0005) and to those in academic practice settings compared with those in community settings (94% and 77%, respectively; P < .0005). For those without access to ROSE, most (85%) used cell block cytology to send samples for pathology. Overall, most (75%) agreed that cell block cytology is as useful as a core biopsy to collect tissue for diagnostic and biomarker analysis.

Figure 2.

Comparison of awareness of guidelines for number of passes performed during endobronchial ultrasound with transbronchial needle aspiration (EBUS-TBNA) by volume of EBUS-TBNA performed, presence of interventional pulmonology subspecialty training, and practice setting. This was only assessed for providers who reported performing EBUS-TBNA (n = 280). ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .005. EBUS = endobronchial ultrasound with transbronchial needle aspiration.

Figure 3.

Number of extra needle passes per site during endobronchial ultrasound with transbronchial needle aspiration for biomarker testing.

Coordination of Biomarker Testing

Pulmonologists and members of their institutions have different practices for ordering and coordinating biomarker testing (e-Table 4). Oncologists were most commonly responsible for ordering biomarker testing (37%), followed by pathologists, pulmonologists, and tumor boards (31%, 23%, and 7%, respectively). Nearly one-half (48%) reported an institutional policy for handling biomarker testing for patients with advanced NSCLC. IPs were more likely to report having an institutional policy than general pulmonologists (59% vs 46%, respectively; P < .019), as were APs compared with community pulmonologists (58% vs 44%, respectively; P < .006). Nearly 40% routinely sent all samples for biomarker testing, whereas approximately one-third tested samples based on cell type determination and about one-quarter sent samples for testing based on oncologist preference. Routine testing of all samples was associated with presence of an institutional policy (50% and 29%; P < .0005) and academic practice setting (46% and 36%; P < .03) when compared with absence of a policy and community centers, respectively. The pathologist was more likely to be responsible for biomarker testing when an institutional policy was present when compared with absent (40% vs 23%, respectively; P < .005). In-house biomarker testing was reported by 20%, outside testing by 44%, and a combination of the two by 31% of pulmonologists surveyed.

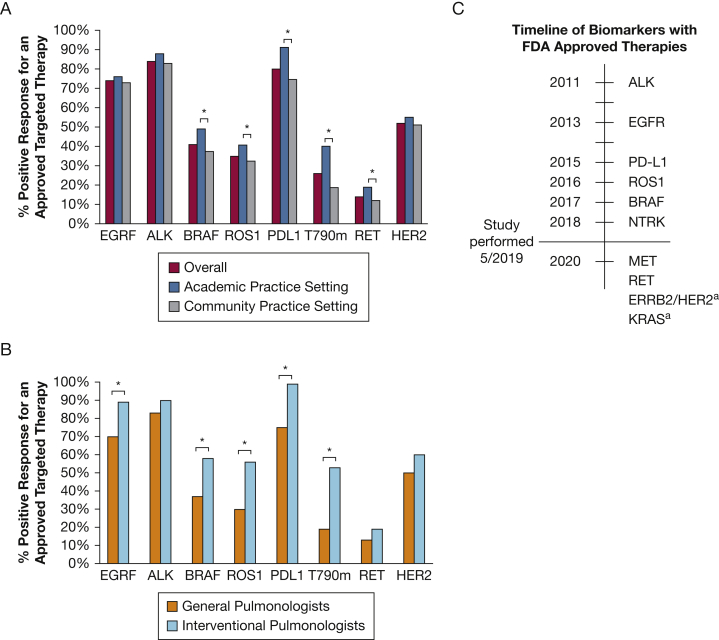

Knowledge and Practice for Individual Molecular Tests and Therapeutics

Pulmonologists were asked to select molecular biomarkers for which they routinely test outside of clinical trials (Table 2). At the time of our study, the six following biomarkers had FDA-approved therapies: ALK, EGFR, PD-L1, ROS1, BRAF, and NTRK (Fig 4C). Testing was high overall for EGFR (99%) and ALK (95%) testing with no significant differences based on practice setting, subspecialty, or presence of an institutional testing policy. Higher rates of testing for nine biomarkers (BRAF, ROS1, NTRK, PD-L1, ERRB2/HER2, KRAS, MET, RET, and TMB) were associated with academic practice setting, six biomarkers (BRAF, ROS1, KRAS, MET, RET, and TMB) with interventional subspecialty, and four biomarkers (BRAF, ROS1, NTRK, and PD-L1) with presence of an institutional policy (P < .05). Finally, the respondents were given a list of lung cancer biomarkers (EGFR, ALK, BRAF, ROS1, PD-L1, T790M, RET, and ERBB2/HER2) and asked whether they were aware of an FDA-approved targeted chemotherapeutic for this biomarker (Fig 4). Overall, pulmonologists identified biomarkers with approved targeted therapies at the highest rate for those with the longest duration of FDA approval and did worse identifying those with more recent approval. About one-half incorrectly identified ERBB2/HER2 as having an FDA-approved therapy for advanced NSCLC. IPs had a higher rate of identifying available targeted therapies associated with biomarkers compared with general pulmonologists, including EGFR, BRAF, ROS1, PD-L1, and T790M (P < .005). A similar trend was seen among APs compared with community pulmonologists for BRAF, PD-L1, and T790M (P < .05).

Table 2.

Frequency for Which Biomarkers Were Routinely Tested Outside of Clinical Trials by Practice Setting, Subspecialty Training, and Presence of Institutional Policy (N = 453)

| Biomarker | No. (%) | Comparison by Practice Setting |

Comparison by Subspecialty Training |

Comparison by Presence of an Institutional Testing Policy |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academic Setting (%) | Community Setting (%) | Interventional Pulmonologists (%) | General Pulmonologists (%) | Institutional Policy (%) | Lack of a Policy (%) | ||

| EGFRa | 447 (99) | 99 | 98 | 100 | 98 | 98 | 100 |

| ALKa | 430 (95) | 97 | 94 | 100 | 94 | 96 | 94 |

| BRAFa | 201 (44) | 55b | 39b | 70b | 38b | 51b | 38b |

| ROS1a | 219 (48) | 55b | 45b | 80b | 40b | 55b | 42b |

| NTRKa | 57 (13) | 17b | 10b | 14 | 12 | 15b | 10b |

| PD-L1a | 347 (77) | 84b | 73b | 99 | 71 | 82b | 72b |

| ERBB2/HER2 | 149 (33) | 40b | 29b | 41b | 31b | 34 | 32 |

| KRAS | 309 (68) | 74b | 65b | 82b | 65b | 70 | 67 |

| MET | 84 (19) | 29b | 13b | 34b | 15b | 20 | 17 |

| RET | 70 (15) | 26b | 10b | 27b | 12b | 18 | 13 |

| TMB | 41 (9) | 16b | 6b | 18b | 7b | 10 | 9 |

Biomarkers with Food and Drug Administration approval at the time the study was performed.

Significant difference with P < .05.

Figure 4.

A, Percent responding that an FDA-approved targeted therapy exists for the corresponding molecular biomarker for all respondents, and by academic and community practice settings. B, Percent responding that an FDA-approved targeted therapy exists for the corresponding molecular biomarker comparing general and interventional pulmonologists. C, Timeline of FDA approval for molecular biomarkers with associated targeted therapeutics. aFDA breakthrough therapy designation only (not full approval). FDA = Food and Drug Administration. b∗P < .05.

Discussion

Biomarker-driven targeted therapies for patients with advanced NSCLC offer opportunities for improved outcomes. For example, osimertinib and alectinib have demonstrated median survivals of > 3 and 5 years for patients with EGFR mutations and ALK rearrangements, respectively.4,25 In comparison, patients with nonsquamous NSCLC treated with pemetrexed and cisplatin have a median survival of < 1 year.26 Additionally, there is evidence that targeted therapies may worsen outcomes if the associated oncogenic driver is not present, further demonstrating the importance of biomarker testing. In the Iressa trial, for the subgroup of patients who were negative for EGFR mutations, progression-free survival was significantly longer among those who received carboplatin-paclitaxel compared with those who received gefitinib.11 This rapidly evolving field poses unique challenges for pulmonologists and the multidisciplinary teams who care for patients with lung cancer. The current study adds to our knowledge about how pulmonologists manage biomarker testing in three notable ways. First, there is significant variation by practice type and setting, the volume of EBUS-TBNA performed, the technique used to acquire tissue, and the knowledge of guideline-recommended care when evaluating patients with suspected advanced NSCLC. Second, significant differences exist between practice type, setting, and presence of institutional policy in the rate of biomarker testing and knowledge of available targeted agents. Finally, there is significant variation in the coordination of biomarker testing between subspecialty services across institutions. To provide patients with optimal care, improvements in all three areas will be necessary to make targeted therapies more widely available.

This study documents significant variation in the frequency with which pulmonologists encounter advanced NSCLC in clinical practice and how they use EBUS-TBNA. EBUS-TBNA commonly provides the least invasive tissue sampling method for diagnosis and staging and was shown in a meta-analysis to be 95% effective for tissue acquisition for biomarker analysis.17,18 As one might expect, IPs in our study saw more lung cancer cases per month, used EBUS-TBNA more often, had higher awareness of guidelines for EBUS-TBNA, and had higher rates of routine testing of more biomarkers. Examination of study outcomes by both practice setting and interventional training suggests that the high proportion of interventionalists in the academic setting drives the associations with improved knowledge and practices for the academic setting (e-Table 2). Multiple studies support a relationship between higher procedural volumes or experience with more appropriate lung cancer staging and an increased diagnostic yield.27, 28, 29, 30 One study assessed appropriateness of mediastinal staging with EBUS-TBNA in a simulation for 60 pulmonologists and found that increased procedural volume correlated with appropriate staging.28 Based on these results, we suspect that pulmonologists who see few patients with lung cancer and/or perform few procedures are more likely to underuse biomarker testing. A variety of barriers likely contribute to this phenomenon at both the community and institutional level. These include access to technologies (eg, EBUS-TBNA, ROSE), subspecialty expertise, or opportunities for training and knowledge enhancement.

This study also revealed differences regarding practices and awareness of guidelines for EBUS-TBNA. Possible knowledge deficiencies identified include not following any guidelines for performing EBUS-TBNA, lack of awareness of guidelines for the recommended number of passes to make at each site, and making fewer than three passes per site during EBUS-TBNA. Despite randomized trials showing no evidence for difference in yield by needle size used during EBUS-TBNA, some report needle gauge factors into the number of passes they perform.31,32 ROSE is a well-established tool to aid in diagnosis and ensure sample adequacy for EBUS-TBNA.33 Although there is a paucity of data investigating utilization of ROSE, one survey of cytopathologists suggests a median utilization of 70%; however, some did not use it at all.34 The determination of adequacy for biomarker analysis without ROSE during EBUS-TBNA remains unanswered. Given the apparent positive associations with increased procedural volumes, subspecialty interventional training, and academic practice centers, two possible solutions include either improved education for providers in need or referral of patients to providers with adequate resources and training.

There is also significant variation in knowledge of targeted therapies and reported testing rates for biomarkers that appear to lag behind their FDA approval, such that those available the longest (eg, EGFR and ALK TKIs) are those which are most likely to be tested for presence. A similar trend was found in a survey of members of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer that assessed biomarker utilization by different providers worldwide in 2018.35 In comparison, HER2/ERBB2, a biomarker for breast cancer-targeted therapy, has an analogous trend toward increased testing over time. Its first targeted therapy, trastuzumab, was approved for the treatment of breast cancer in 1998, and guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology in 2007 recommended testing for all invasive breast cancers.36 Few studies look at utilization at a national level over time. One health system’s study reviewing new diagnoses in 1999 and 2000 showed a HER2 testing rate of 51.8%; a later national study in 2010 reported a testing rate of 91.2%.37,38

Significant differences in coordination of biomarker testing are evident by variation in the provider responsible for test ordering and whether institutions have a policy to guide them. Nearly one-quarter of pulmonologists order biomarker testing that places a burden to stay informed of the landscape of testing and treatment. Providers who perform few EBUS-TBNA and who do not have institutionally driven testing may be at a particular disadvantage. Over one-third of the time, oncologists were responsible for ordering biomarker testing. However, testing would ideally be ordered at the time of tissue acquisition, to prevent delays in treatment. Only one-half of those surveyed reported having an institutional policy, which when present, correlated with higher rates of testing for multiple actionable biomarkers. Overall, these results argue for better interdisciplinary communication between specialties and hospital infrastructure to coordinate testing.

Reflex testing may reduce the burden of knowledge on individual providers and would allow pulmonologists to focus on adequate tissue acquisition, rather than nuances and logistics of testing.39 Reflex testing increases the number of patients tested and reduces time to appropriate treatment.39, 40, 41, 42 In one study, reflex testing increased EGFR testing rates from 79% to 95% and ALK testing from 44% to 83% with reduced time to appropriate treatment from a median of 36 to 22 days.40 Another study demonstrated disparities in testing for EGFR and ALK with fourfold higher testing for patients with an Asian background, fivefold higher testing for patients who never smoked, and twice higher testing for women.42 Systematic testing would have the potential to reduce effects of implicit bias of providers. Perhaps most importantly, it is unrealistic to expect practicing pulmonologists, especially those who see very few patients with lung cancer, to keep abreast of the ever-changing landscape of biomarkers and targeted therapies. Next-generation sequencing panels allow for comprehensive testing without the need for knowledge about individual tests. We suggest institutions develop testing policies that focus on interdisciplinary communication and testing strategies that are systematic, comprehensive, and modifiable as advances are made in biomarkers and targeted therapies. We feel institutional policies should, at minimum, attempt to test all eligible patients for biomarkers with FDA-approved targeted therapies in a manner that works best with their institutional workflow and patient population.

This study has several limitations. The response rate is low; however, this is quite common when physicians are surveyed. This finding makes the results of the survey more difficult to generalize. Given the complexities of health care systems, recall bias has the potential to have significant influence on responses, especially those involving institutional practices. For example, a response indicating a lack of an institutional policy for when to perform biomarker testing may simply indicate a lack of awareness of the policy. Additional research is needed to identify individual and institutional factors associated with successful biomarker testing and treatment with targeted therapies. Characteristics of responders and nonresponders suggest a possible nonresponse bias with a smaller portion of community pulmonologists completing the survey (62% among responders and 75% among nonresponders). Despite these limitations, we report practice patterns of many pulmonologists (N = 453) from diverse practice settings which provide valuable insights on current knowledge and practice patterns concerning care for patients with advanced NSCLC in the era of targeted therapy.

Interpretation

Pulmonologists face new challenges caring for patients with advanced NSCLC in an era of rapidly evolving targeted therapy options. This study documents variation in key aspects of care that may influence biomarker testing. Some differences by practice setting and subspecialty training argue for improvements and standardization of care through education and/or specialization of care. Finally, systematic and uniform comprehensive biomarker testing strategies with a focus on interdisciplinary communication should alleviate burdens on pulmonologists and improve biomarker testing rates and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Take-home Points.

Study Question: What is the current knowledge and practice of pulmonologists regarding biomarker testing and targeted therapies in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)?

Results: Pulmonologists vary by the volume of patients with advanced NSCLC seen in clinical practice, their knowledge and practices for performing endobronchial ultrasound with transbronchial needle aspiration and biomarker testing, and in how they coordinate testing with other specialties.

Interpretation: Improvements in tissue acquisition, knowledge of biomarkers and associated targeted therapies, and coordination of testing for patients with advanced NSCLC are required to increase utilization of biomarker testing and treatment with targeted therapies.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: G. A. S. takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article. G. A. S., J. R. J., U. B. R., J. C. K., N. M., and R. A. S. contributed to study design, interpretation of results, composition, and revision. A. H. F., B. E. J., R. U. O., M. P. R., and L. S. R. contributed to interpretation of results, composition, and revision.

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: None declared.

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Additional information: The e-Appendix and e-Tables can be found in the Supplemental Materials section of the online article.

Footnotes

Part of this article has been presented at the CHEST Annual Meeting, October 18-21, 2020.

FUNDING/SUPPORT: This study is supported by the National Institutes of Health [Grant NIH-T21-HL144470].

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Howlader N., Noone A.M., Krapcho M., et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review (CSR), 1975-2017. https://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2017/

- 2.Howlader N., Forjaz G., Mooradian M.J., et al. The effect of advances in lung-cancer treatment on population mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(7):640–649. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiller J.H., Harrington D., Belani C.P., et al. Comparison of four chemotherapy regimens for advanced non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(2):92–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mok T., Camidge D.R., Gadgeel S.M., et al. Updated overall survival and final progression-free survival data for patients with treatment-naive advanced ALK-positive non-small-cell lung cancer in the ALEX study. Ann Oncol. 2020;31(8):1056–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin J.J., Cardarella S., Lydon C.A., et al. Five-year survival in EGFR-mutant metastatic lung adenocarcinoma treated with EGFR-TKIs. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11(4):556–565. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2015.12.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inoue A., Yoshida K., Morita S., et al. Characteristics and overall survival of EGFR mutation-positive non-small cell lung cancer treated with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors: a retrospective analysis for 1660 Japanese patients. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2016;46(5):462–467. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyw014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solomon B.J., Kim D.W., Wu Y.L., et al. Final Overall survival analysis from a study comparing first-line crizotinib versus chemotherapy in ALK-mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(22):2251–2258. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.77.4794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan M., Huang L.-L., Chen J.-H., Wu J., Xu Q. The emerging treatment landscape of targeted therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2019;4:61. doi: 10.1038/s41392-019-0099-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosell R., Carcereny E., Gervais R., et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(3):239–246. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khozin S., Blumenthal G.M., Jiang X., et al. U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval summary: erlotinib for the first-line treatment of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer with epidermal growth factor receptor exon 19 deletions or exon 21 (L858R) substitution mutations. Oncologist. 2014;19(7):774–779. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mok T.S., Wu Y.-L., Thongprasert S., et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin–paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindeman N.I., Cagle P.T., Aisner D.L., et al. Updated molecular testing guideline for the selection of lung cancer patients for treatment with targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors: guideline from the College of American Pathologists, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, and the Association for Molecular Pathology. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13(3):323–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) NCCN; 2021. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: non-small cell lung cancer. Version 3.2021.https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/category_1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanna N.H., Robinson A.G., Temin S., et al. Therapy for stage IV non–small-cell lung cancer with driver alterations: ASCO and OH (CCO) joint guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(14):1608–1632. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herbst R.S., Giaccone G., de Marinis F., et al. Atezolizumab for first-line treatment of PD-L1–selected patients with NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(14):1328–1339. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1917346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Le D.T., Uram J.N., Wang H., et al. PD-1 blockade in tumors with mismatch-repair deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silvestri G.A., Gonzalez A.V., Jantz M.A., et al. Methods for staging non-small cell lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5):e211S–e250. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Labarca G., Folch E., Jantz M., Mehta H.J., Majid A., Fernandez-Bussy S. Adequacy of samples obtained by endobronchial ultrasound with transbronchial needle aspiration for molecular analysis in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2018;15(10):1205–1216. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201801-045OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynch J.A., Berse B., Rabb M., et al. Underutilization and disparities in access to EGFR testing among Medicare patients with lung cancer from 2010 – 2013. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):306. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4190-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Enewold L., Thomas A. Real-world patterns of EGFR testing and treatment with erlotinib for non-small cell lung cancer in the United States. PLoS One. 2016;11(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kehl K.L., Lathan C.S., Johnson B.E., Schrag D. Race, poverty, and initial implementation of precision medicine for lung cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;111(4):431–434. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djy202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shen C., Kehl K.L., Zhao B., Simon G.R., Zhou S., Giordano S.H. Utilization patterns and trends in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutation testing among patients with newly diagnosed metastatic lung cancer. Clinical Lung Cancer. 2017;18(4):e233–e241. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palazzo L.L., Sheehan D.F., Tramontano A.C., Kong C.Y. Disparities and trends in genetic testing and erlotinib treatment among metastatic non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2019;28(5):926–934. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-18-0917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wahidi M.M., Herth F., Yasufuku K., et al. Technical aspects of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2016;149(3):816–835. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ramalingam S.S., Vansteenkiste J., Planchard D., et al. Overall survival with osimertinib in untreated, EGFR-mutated advanced NSCLC. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(1):41–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1913662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scagliotti G.V., Parikh P., von Pawel J., et al. Phase III study comparing cisplatin plus gemcitabine with cisplatin plus pemetrexed in chemotherapy-naive patients with advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(21):3543–3551. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.0375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bellinger C.R., Chatterjee A.B., Adair N., Houle T., Khan I., Haponik E. Training in and experience with endobronchial ultrasound. Respiration. 2014;88(6):478–483. doi: 10.1159/000368366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miller R.J., Mudambi L., Vial M.R., Hernandez M., Eapen G.A. Evaluation of appropriate mediastinal staging among endobronchial ultrasound bronchoscopists. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14(7):1162–1168. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201606-487OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Castro F.R., López F.D., Serdá G.J., Navarro P.C., López A.R., Gilart J.F. Relevance of training in transbronchial fine-needle aspiration technique. Chest. 1997;111(1):103–105. doi: 10.1378/chest.111.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sehgal I.S., Dhooria S., Aggarwal A.N., Agarwal R. Training and proficiency in endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration: a systematic review. Respirology. 2017;22(8):1547–1557. doi: 10.1111/resp.13121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oki M., Saka H., Kitagawa C., et al. Randomized study of 21-gauge versus 22-gauge endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration needles for sampling histology specimens. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol. 2011;18(4):306–310. doi: 10.1097/LBR.0b013e318233016c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dooms C., Vander Borght S., Yserbyt J., et al. A randomized clinical trial of Flex 19G needles versus 22G needles for endobronchial ultrasonography in suspected lung cancer. Respiration. 2018;96(3):275–282. doi: 10.1159/000489473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jain D., Allen T.C., Aisner D.L., et al. Rapid on-site evaluation of endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspirations for the diagnosis of lung cancer: a perspective from members of the Pulmonary Pathology Society. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142(2):253–262. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0114-SA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.VanderLaan P.A., Chen Y., Alex D., et al. Results from the 2019 American Society of Cytopathology survey on rapid on-site evaluation-part 1: objective practice patterns. J Am Soc Cytopathol. 2019;8(6):333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jasc.2019.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smeltzer M.P., Wynes M.W., Lantuejoul S., et al. The International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Global Survey on Molecular Testing in Lung Cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15(9):1434–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guideline summary: American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor HER2 testing in breast cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3(1):48–50. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0718501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Howlader N., Altekruse S.F., Li C.I., et al. US incidence of breast cancer subtypes defined by joint hormone receptor and HER2 status. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(5):dju055. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stark A., Kucera G., Lu M., Claud S., Griggs J. Influence of health insurance status on inclusion of HER-2/neu testing in the diagnostic workup of breast cancer patients. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16(6):517–521. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gregg J.P., Li T., Yoneda K.Y. Molecular testing strategies in non-small cell lung cancer: optimizing the diagnostic journey. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2019;8(3):286–301. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2019.04.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheema P.K., Menjak I.B., Winterton-Perks Z., et al. Impact of reflex EGFR/ALK testing on time to treatment of patients with advanced nonsquamous non–small-cell lung cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2016;13(2):e130–e138. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.014019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheema P.K., Raphael S., El-Maraghi R., et al. Rate of EGFR mutation testing for patients with nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer with implementation of reflex testing by pathologists. Curr Oncol. 2017;24(1):16–22. doi: 10.3747/co.24.3266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lim C., Tsao M.S., Le L.W., et al. Biomarker testing and time to treatment decision in patients with advanced nonsmall-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2015;26(7):1415–1421. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.