Visual Abstract

Keywords: atrasentan, endothelin receptor antagonist, albuminuria, kidney outcome, hospitalization for heart failure, heart failure, urinary tract physiological phenomena

Abstract

Background and objectives

Atrasentan reduces the risk of kidney failure but increases the risk of edema and, possibly, heart failure. Patients with severe CKD may obtain greater absolute kidney benefits from atrasentan but may also be at higher risk of heart failure. We assessed relative and absolute effects of atrasentan on kidney and heart failure events according to baseline eGFR and urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (UACR) in a post hoc analysis of the Study of Diabetic Nephropathy with Atrasentan (SONAR) trial.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

The effect of atrasentan versus placebo in 3668 patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD with elevated albuminuria was examined in the SONAR trial. We used Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to study effects on the primary kidney outcome (composite of doubling of serum creatinine, kidney failure, or kidney death) and heart failure hospitalization across subgroups of eGFR (<30, ≥30–45, and ≥45 ml/min per 1.73 m2) and UACR (<1000, ≥1000–3000, and ≥3000 mg/g).

Results

Atrasentan reduced the relative risk of the primary kidney outcome (hazard ratio, 0.71; 95% confidence interval, 0.58 to 0.88) consistently across all subgroups of baseline eGFR and UACR (all P interaction >0.21). Patients in the highest UACR and lowest eGFR subgroups, in whom rates of the primary kidney outcome were highest, showed the largest absolute benefit (all P interaction <0.01). The risk of heart failure hospitalization was higher in the atrasentan group (hazard ratio, 1.39; 95% confidence interval, 0.97 to 1.99) and was consistent across subgroups, with no evidence that relative or absolute risks differed across eGFR or UACR subgroups (all P interaction >0.09).

Conclusions

Atrasentan reduced the relative risk of the primary kidney outcome consistently across baseline UACR and eGFR subgroups. The absolute risk reduction was greater among patients in the lowest eGFR and highest albuminuria category who were at highest baseline risk. Conversely, the relative and absolute risks of heart failure hospitalization were similar across baseline UACR and eGFR subgroups.

Clinical Trial registry name and registration number: Study of Diabetic Nephropathy with Atrasentan (SONAR), NCT01858532

Introduction

Inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system confer kidney protection in patients with CKD with and without diabetes (1–3). Prior studies have shown that the benefits of these drugs are consistent regardless of the eGFR level, and some studies suggested that their benefits may be greater in patients with higher levels of albuminuria (4,5).

Atrasentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA), decreased albuminuria and reduced the risk of kidney failure in the Study of Diabetic Nephropathy with Atrasentan (SONAR) trial (6). However, ERAs, including atrasentan, may cause fluid retention that may lead to edema and higher risk of heart failure (7). Despite incorporation of precautionary measures in the design of the SONAR trial, the proportion of patients with adverse events related to fluid retention was higher in the atrasentan group compared with the placebo group (6).

Higher albuminuria and lower eGFR are well-known to be associated with kidney failure, and they are the basis of the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes classification system (8). As kidney function declines, the capacity of the kidney to regulate sodium and fluid decreases. Accordingly, the incidence of heart failure is higher in patients with more severe kidney damage (9). Because albuminuria and eGFR are strongly associated with kidney failure, patients with more severe kidney disease (i.e., those with higher albuminuria and lower eGFR values) might obtain a greater absolute kidney benefit from albuminuria-lowering drugs, such as ERAs. Whether the relative and absolute risks of heart failure due to ERA therapy are more pronounced in patients with more severe kidney disease is unknown.

Patients with type 2 diabetes and stages 2–4 CKD (eGFR between 25 and 75 ml/min per 1.73 m2) with greatly increased albuminuria (urinary albumin-creatinine ratio [UACR] between 300 and 5000 mg/g) were enrolled in the SONAR trial. In this population at risk for kidney and heart failure events, we assessed the relative and absolute effects of atrasentan on kidney and heart failure outcomes according to subgroups of baseline albuminuria and eGFR.

Materials and Methods

Patients and Study Design

We performed a post hoc analysis of the SONAR trial. SONAR was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial that evaluated the effect of atrasentan on kidney outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD. The design and results have been published previously (6,10,11). The SONAR trial included patients with type 2 diabetes with ages ranging between 18 and 85 years, eGFR between 25 and 75 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and UACR between 300 and 5000 mg/g who were receiving a maximally tolerated dose of an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker. Patients with B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels >200 pg/ml were excluded.

In the enrichment phase of the SONAR trial, 5117 patients from 689 sites in 41 countries were enrolled. During this 6-week open-label period, all patients received a daily dose of 0.75 mg of atrasentan. The goal of the enrichment period was to select patients who responded to atrasentan and to exclude patients who developed adverse effects. Patients who had a weight gain of >3 kg or had a BNP of ≥300 pg/ml during enrichment had to discontinue participating in the trial. Responders were defined as patients with at least a 30% reduction in UACR, and nonresponders were defined as patients with <30% reduction in UACR. Of the 5117 patients entering the enrichment phase, 3668 patients continued into the double-blind period, of whom 2648 were responders and 1020 were nonresponders. In the double-blind period, patients either continued with 0.75 mg of atrasentan per day or were transitioned to placebo (1:1). Because the effects of atrasentan on the primary outcome did not differ between the responder and nonresponder strata, we combined the two strata for the purpose of this analysis (6).

The SONAR trial is registered at clinicaltrials.gov; its protocol was approved by local or central ethics committees for each trial site and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (version amended October 2000).

Urinary Albumin-Creatinine Ratio and Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate Measurements and Categories

eGFR was calculated from the serum creatinine measurements using the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration equation (12). The population was stratified on the basis of eGFR, and UACR was measured at baseline before the start of the enrichment period. eGFR was categorized using the following thresholds: ≥45, ≥30–45, and <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2. UACR categories were defined as <1000, ≥1000 to <3000, and ≥3000 mg/g.

Outcomes

The primary kidney outcome was a composite consisting of doubling of serum creatinine confirmed by a second measurement, onset of kidney failure, or kidney death. Kidney failure was defined as an eGFR <15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 confirmed by a second measurement after ≥30 days, the start of maintenance dialysis for at least 90 days, or a kidney transplantation. Other kidney outcomes were the individual components of the composite end point of doubling of serum creatinine and kidney failure separately. Cardiovascular outcomes were heart failure hospitalization and a composite of heart failure hospitalization and cardiovascular death. Heart failure hospitalization was a prespecified safety outcome in the trial. All primary and secondary end points and heart failure hospitalization outcomes were adjudicated by an independent event adjudication committee using rigorous outcome definitions, and the members were blinded to study treatment assignment (10).

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics are presented as means and SDs. For variables with a non-normal distribution, the median and the interquartile range (IQR) are reported. Categorical variables are shown as the number of observations and the percentage of observations. UACR was log transformed in all analyses to account for their skewed distributions. Differences in baseline characteristics across the defined subgroups of eGFR and UACR were tested with one-way ANOVA or the chi-squared test where appropriate. Event rates were calculated as the number of events per 100 patient-years using Poisson regression.

In the overall population, we used Cox proportional hazards regression analyses to calculate the treatment effect of atrasentan compared with placebo on all outcomes. We analyzed subgroups of eGFR and UACR and adjusted the Cox model for log-transformed UACR (at the start of enrichment and at randomization), serum albumin at randomization, age, and eGFR at randomization, as prespecified in the SONAR trial (10). The heterogeneity of treatment effects across the eGFR and UACR subgroups was assessed by adding the subgroup categories as an interaction term with treatment in each model.

The absolute risk reduction (ARR) was calculated as described by Altman and Andersen (13) using the hazard ratio (HR) and event rate. We used the pooled HR of the overall population when significant heterogeneity across subgroups was absent. When heterogeneity across subgroups was detected, the HR of the interaction model was used to calculate the ARR. Heterogeneity in ARR across eGFR and UACR subgroups was estimated using fixed effects metaregression (14,15).

We analyzed the effects of atrasentan on eGFR slope using a mixed effects model with a random intercept and random slope for treatment. The model included fixed effects of treatment, visit, and subgroup category. To determine eGFR slopes for each eGFR and UACR subgroup, we added to the model all possible interaction terms for treatment effect, subgroup, and visit. To allow generality for the covariance structure, we used an unstructured variance-covariance matrix (i.e., purely data dependent).

Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 14.2 SE (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and the R package Survival version 2.44–1.1 (16,17) in the R programming language version 3.5.1. Two-sided P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 3668 patients were randomly assigned to atrasentan (n=1834) or placebo (n=1834) in the SONAR trial. At baseline, patients had a mean age of 65 years (SD 9), 946 (26%) patients were women, mean eGFR was 43 (SD 14) ml/min per 1.73 m2, and median UACR was 829 (IQR, 457–1556) mg/g.

There were 2127 (58%), 1269 (35%), and 271 (7%) patients with baseline UACR of <1000, ≥1000–3000, and ≥3000 mg/g, respectively. Patients with a higher baseline UACR were more likely to be women and had higher BP and BNP, but they had lower eGFR (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the Study of Diabetic Nephropathy with Atrasentan participants according to baseline urinary albumin-creatinine ratio and eGFR

| Characteristic | Baseline eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | Baseline Urinary Albumin-Creatinine Ratio, mg/g | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 | ≥30–45 | ≥45 | <1000a | ≥1000–3000 | ≥3000 | |

| No. of patients | 592 | 1508 | 1567 | 2127 | 1269 | 271 |

| Age, yr | 65 (9) | 65 (9) | 64 (9) | 66 (8) | 63 (9) | 62 (10) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Men | 412 (70) | 1119 (74) | 1191 (76) | 1578 (74) | 959 (76) | 185 (68) |

| Women | 180 (30) | 389 (26) | 376 (24) | 549 (26) | 310 (24) | 86 (32) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 354 (60) | 893 (59) | 863 (55) | 1233 (58) | 716 (56) | 160 (59) |

| Black | 45 (7) | 94 (6) | 85 (5) | 139 (7) | 74 (6) | 11 (4) |

| Asian | 159 (27) | 467 (31) | 571 (37) | 688 (32) | 428 (34) | 82 (30) |

| Other | 34 (6) | 54 (4) | 48 (3) | 67 (3) | 51 (4) | 18 (7) |

| BP, mm Hg | ||||||

| Systolic | 136 (16) | 136 (15) | 137 (15) | 135 (15) | 138 (15) | 140 (16) |

| Diastolic | 73 (10) | 75 (10) | 76 (10) | 74 (10) | 76 (10) | 78 (10) |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 2.4 (0.4) | 1.8 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.2) | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.5) |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 25 (3) | 37 (4) | 56 (10) | 44 (14) | 42 (13) | 39 (13) |

| HbA1c, | 7.4 (1.5) | 7.6 (1.5) | 7.6 (1.5) | 7.5 (1.4) | 7.7 (1.5) | 7.7 (1.6) |

| Serum albumin, g/dl | 3.9 (0.4) | 3.9 (0.4) | 4.0 (0.3) | 4.0 (0.3) | 3.8 (0.3) | 3.5 (0.4) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 12.3 (1.6) | 12.8 (1.7) | 13.3 (1.7) | 13.0 (1.7) | 12.8 (1.7) | 12.6 (1.9) |

| B-type natriuretic, pg/ml | 52 [27–93] | 50 [27–88] | 45 [24–82] | 45 [24–80] | 51 [27–91] | 66 [37–117] |

| UACR, mg/g | 963 [527–1888] | 898 [498–1622] | 731 [417–1336] | 511 [339–713] | 1576 [1240–2084] | 3688 [3276–4308] |

| Medications, n (%) | ||||||

| β-blocker | 259 (44) | 660 (44) | 611 (39) | 897 (42) | 516 (41) | 118 (44) |

| Diuretics | 527 (89) | 1286 (85) | 1251 (80) | 1774 (83) | 1055 (83) | 236 (87) |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | 489 (83) | 1198 (79) | 1225 (78) | 1668 (78) | 1037 (82) | 207 (76) |

| SGLT2 inhibitor | 2 (0.3) | 20 (1) | 31 (2) | 32 (2) | 17 (1) | 4 (1) |

| History of cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 95 (16) | 220 (15) | 240 (15) | 330 (16) | 178 (14) | 47 (17) |

Characteristics are shown at the start of the active run-in period (enrichment period) except for Hba1c, which was only measured at randomization. Data are reported as mean (SD), median [interquartile range], or n (percentage). HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; UACR, urinary albumin-creatinine ratio; SGLT2, sodium-glucose cotransporter 2.

The majority (81) of patients had a UACR of 300–1000 mg/g.

Across eGFR categories, 1567 (43%), 1508 (41%), and 592 (16%) patients had baseline eGFR of ≥45, ≥30–45, and <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively. Patients with a lower baseline eGFR had a higher UACR and BNP (Table 1).

Kidney Outcomes

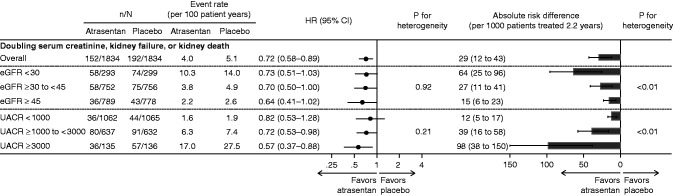

During a median 2.2-year (IQR, 1.4–2.9) follow-up, the event rate for the primary kidney outcome (doubling of serum creatinine, kidney failure, and kidney death) was progressively higher in higher UACR categories and lower eGFR categories. For example, in the placebo group, 1.9 (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.4 to 2.6) events per 100 patient-years occurred in patients with baseline UACR <1000 mg/g versus 27.5 (95% CI, 21.2 to 35.6) events per 100 patient-years in patients with a baseline UACR ≥3000 mg/g (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Atrasentan reduced the relative risk of the primary kidney outcome consistently across all categories of baseline eGFR and urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (UACR); patients in the highest UACR and lowest eGFR categories showed the largest absolute benefit. The figure shows the relative effect and absolute risk differenceof atrasentan on theprimary kidney end point across baseline eGFR and UACRcategories. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio.

The effect of atrasentan on the primary kidney outcome (HR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.58 to 0.89) was consistent across all baseline eGFR (P interaction >0.92) and UACR subgroups (P interaction >0.21) (Figure 1). Additionally, the effect of atrasentan on doubling of serum creatinine (HR, 0.74; 95% CI, 0.57 to 0.95) and kidney failure (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.55 to 0.88) was similar across eGFR and UACR subgroups (all P interaction >0.51) (Supplemental Figure 1).

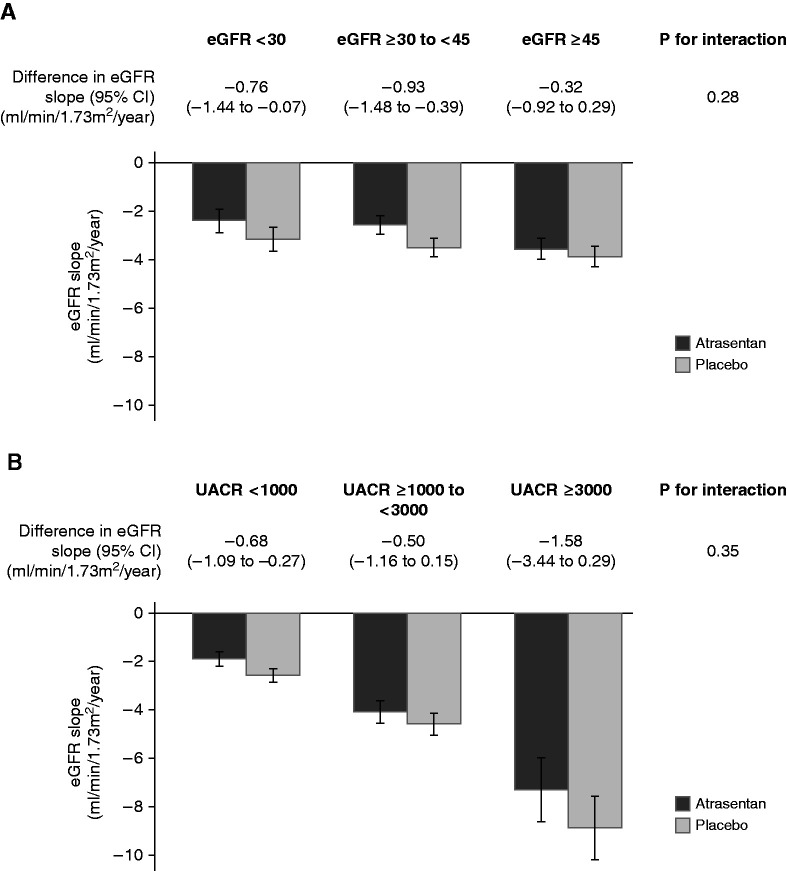

The annual change in eGFR was −3.6 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (95% CI, −3.9 to −3.3) in the placebo group. Atrasentan reduced the annual rate of change in eGFR to −3.0 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (treatment effect, −0.6; 95% CI, −1.0 to −0.3; P<0.001). The effect of atrasentan on eGFR slope was consistent, irrespective of UACR and eGFR categories (all P interaction >0.28) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The effect of atrasentan on eGFR slope was consistent, irrespective of urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (UACR) and eGFR categories. The figure shows the effect of atrasentan versus placebo on eGFR slope across baseline eGFR (A) and UACR (B) categories.

Although the relative risk reductions were consistent for all kidney outcomes according to baseline eGFR and UACR categories, the absolute benefit appeared greatest in the highest UACR category (≥3000 mg/g; P interaction <0.01) and lowest eGFR category (<30 ml/min per 1.73 m2; P interaction <0.01) (Figure 1). For every 1000 patients with the highest level of baseline albuminuria or lowest eGFR treated over 2.2 years, atrasentan would be expected to prevent 98 and 64 participants from experiencing the primary kidney outcome, respectively. The absolute benefit of atrasentan was also largest in the highest UACR and lowest eGFR categories when the kidney failure end point was analyzed alone (Supplemental Figure 1).

When the atrasentan UACR responder population was analyzed, the relative effects of atrasentan on the kidney end points were consistent regardless of baseline UACR and eGFR. The absolute effects for the primary kidney outcome differed by baseline UACR and eGFR, similar to our main analyses (Supplemental Figure 2).

Heart Failure

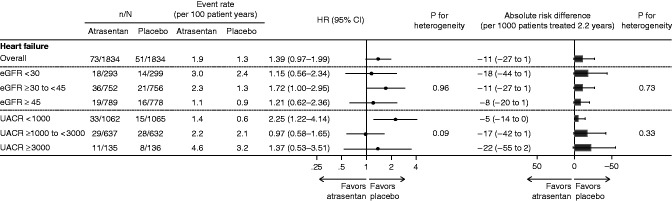

The rate of heart failure hospitalization was progressively higher in higher UACR categories and lower eGFR categories, although the risk gradient was less steep than for the primary kidney outcome (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The relative and absolute risks for heart failure hospitalization related to the use of atrasentan were consistent across eGFR and urinary albumin-creatinine ratio (UACR) categories. The figure shows the relative effect and absolute risk difference of atrasentan on heart failure hospitalization across baseline eGFR and UACR categories.

In the overall population, we observed higher risks of heart failure hospitalization (HR, 1.39; 95% CI, 0.97 to 1.99) and the composite end point of heart failure or cardiovascular death (HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 0.97 to 1.71) in patients treated with atrasentan. The risk for heart failure related to use of atrasentan was consistent across eGFR and UACR subgroups (all P interaction >0.09) (Figure 3). Similar results were seen for the composite end point of heart failure and cardiovascular death (Supplemental Figure 3).

The absolute effect of atrasentan on the risk of heart failure hospitalization was consistent across eGFR and UACR subgroups (all P interaction >0.33) (Figure 3). For every 1000 patients treated over 2.2 years, atrasentan caused 11 participants to experience heart failure hospitalization (Figure 3). The absolute risk related to atrasentan was also consistent for the composite end point of heart failure and cardiovascular death across subgroups (Supplemental Figure 3).

In the atrasentan responder population, the relative and absolute effects of atrasentan on the heart failure end points were consistent regardless of baseline UACR and eGFR (Supplemental Figure 4).

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of the SONAR trial, we demonstrated that atrasentan reduced the relative risk of kidney disease progression that was consistent across subgroups of baseline albuminuria and eGFR. Because the rates of kidney outcomes were higher at lower eGFR or higher UACR values, the greatest ARR with atrasentan treatment was observed in the lowest eGFR and highest UACR categories. Conversely, both the higher relative risk and the higher absolute risk for heart failure hospitalization with atrasentan were consistent across subgroups of baseline albuminuria and eGFR. Together, these findings indicate that the benefit to risk ratio for atrasentan is most favorable in patients with the lowest eGFR or highest albuminuria.

Our first major observation was that atrasentan’s efficacy in reducing the relative risk of doubling of serum creatinine or kidney failure was preserved in patients with the lowest levels of eGFR and highest albuminuria. The absolute benefits on these clinically important kidney outcomes were greater in those with lower eGFR and more pronounced albuminuria because of their higher absolute risk at baseline. These beneficial effects of atrasentan were reinforced by the attenuation of decline in kidney function across all categories of baseline eGFR and albuminuria. It is important to note that these benefits of atrasentan were obtained on top of maximum recommended ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker treatment, and they underscore the value of atrasentan even in patients at the highest risk of kidney failure. Additionally, in the SONAR trial, atrasentan was deliberately continued until patients reached dialysis, and there was no eGFR threshold below which study treatment had to be discontinued.

ERAs increase the risk of fluid retention and heart failure (6,7). Here, we show that the risk of heart failure with atrasentan was consistent across subgroups of baseline kidney function. Earlier studies with ERAs reported conflicting results regarding the risk of heart failure by baseline eGFR. One study showed a higher risk for atrasentan-associated fluid retention in patients with a lower eGFR (18), whereas in a study with the ERA avosentan, the risk for avosentan-induced heart failure was higher in patients with a higher eGFR (19). Because ERAs are known to cause fluid retention, additional measures were incorporated in the design of the SONAR trial to reduce the risk of edema and heart failure. These were exclusion of patients with known heart failure or BNP>200 pg/ml, optimization of diuretic treatment, an active run-in period, and an enrichment period to identify and exclude patients who did not tolerate atrasentan (10). These measures led to a population at relatively low risk of heart failure as reflected by the lower event rates in SONAR (1.2 per 100 patient-years) compared with other recent trials in patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD, including FIDELIO-DKD (2.2 per 100 patient-years) and CREDENCE (2.5 per 100 patient-years) (20,21).

Understanding the benefits and risks of ERAs in specific patient subgroups will guide appropriate use of ERAs in clinical practice. Because the absolute benefit (reflected in kidney failure) was higher at advanced stages of CKD but absolute risk (reflected in heart failure) was not, the overall benefit-risk ratio of atrasentan was favorable even in patients with advanced CKD. However, it has been shown that intervention at early stages of CKD delays the time to dialysis more than late intervention (22). The SONAR trial only recruited patients with severe kidney disease, and benefit-risk comparisons with patients at the earliest stages of CKD cannot be made. Additional trials with ERAs in patients with higher eGFR and lower UACR are ongoing and will also evaluate possible synergistic effects with sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (ZENITH-CKD: NCT04724837 and AFFINITY: NCT04573920).

The strengths of the SONAR trial are that it was a large, international trial representing a broad cohort of patients with advanced CKD and used rigorous methods of data collection and end point adjudication. However, this study also has limitations. First, the relatively stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria limit generalizability of the results, which are only certain to apply to patients who share the characteristics of the enrolled population and tolerate atrasentan, defined as no increase in body weight of >3 kg or BNP increase to >300 pg/ml after a few weeks of treatment. In addition, heart failure and BNP >200 pg/ml were exclusion criteria for the trial. We thus studied a population with a narrow BNP range, which limited assessment of the effect of atrasentan in subgroups by baseline BNP. We combined the responder and nonresponder strata for the purpose of this analysis because the effects of atrasentan on the primary outcome did not differ between responders and nonresponders (6). However, the nonresponders were a selection of 1020 patients out of a larger group of nonresponders. Because the SONAR trial was stopped prematurely because of a lower than expected event rate, the statistical power to assess secondary end points, such as heart failure hospitalization, was limited.

In conclusion, the relative reduction in the risk of the primary kidney outcome with atrasentan was consistent across subgroups of baseline albuminuria and eGFR. Therefore, the greatest absolute kidney benefit was observed among patients in the lowest eGFR and highest albuminuria categories who were at highest baseline risk. Conversely, the relative and absolute risks of heart failure hospitalization with atrasentan were similar across baseline eGFR and albuminuria subgroups, suggesting a favorable benefit-risk ratio for atrasentan and supporting its use in patients with eGFR between 25 and 75 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and substantial albuminuria.

Disclosures

G.L. Bakris reports consultancy agreements with Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cyclerion Therapeutics, Horizon Pharma, Ionis, Janssen, KBP Biosciences, Medscape, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Quantum Genomics, Vascular Dynamics, and Vifor; receiving research funding from Bayer, Novo Nordisk, and Vascular Dynamics (funding for steering committee activities that goes to the University of Chicago Medicine); receiving honoraria from Alnylam, AstraZeneca, Ionis, KBP Biosciences, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Teijin, and Vifor; serving on the steering committee or as a principal investigator for Alnylam, Bayer, Novo Nordisk, Quantum Genomics, and Vascular Dynamics; serving as a scientific advisor or member of the American Heart Association, KBP Biosciences, Merck, Teijin, UpToDate Nephrology, and Vifor; serving as an editor of American Journal of Nephrology, an associate editor of Diabetes Care, and an associate editor of Hypertension Research; and other interests/relationships with the American Diabetes Association, the American Heart Association, the Blood Pressure Council, and the National Kidney Foundation. R. Correa-Rotter reports consultancy agreements with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Janssen, Medtronic, and Novo Nordisk; receiving research funding from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, GSK, and Novo Nordisk; receiving honoraria from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, and Takeda (honoraria for consultancy or speaker); serving on advisory boards for AstraZeneca and Boehringer; serving as a scientific advisor or member of the AstraZeneca Membership Steering Committee of Dapagliflozin and Prevention of Adverse Outcomes in Chronic Kidney Disease (DAPA CKD), the GSK National Leader ASCEND (A Randomised, Double Blind, Placebo Controlled, Parallel Group Study to Assess the Effect of the Endothelin Receptor Antagonist Avosentan on Time to Doubling of Serum Creatinine, End Stage Renal Disease or Death in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Diabetic Nephropathy) study, and the Novo Nordisk National Leader FLOW study; serving on the editorial boards of Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension, Nefrologia Latinoamericana, and Revista de Investigación Clinica; serving as an associate editor of Blood Purification; serving on the speakers bureau for AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Janssen, Sanofi, and Takeda; and serving as a member of the European Dialysis and Transplant Associtation/European Renal Assocation (EDTA/ERA), a member of the International Society of Nephrology, a member of the Latin American Society of Nephrology and Hypertension, a member of the Mexican Institute for Research in Nephrology, and a member of the National Kidney Foundation. D. de Zeeuw reports consultancy agreements with Abbvie, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Fresenius, Janssen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, and Travere Pharmaceuticals; honoraria from Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Fresenius, Janssen, Mitsubishi Tanabe, and Travere Pharmaceuticals; has served on advisory boards and/or as a speaker for Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Fresenius, Mundipharma, and Mitsubishi Tanabe; has served on steering committees and/or as a speaker for AbbVie and Janssen; and has served on data safety and monitoring committees for Bayer. R.T. Gansevoort reports consultancy agreements with AstraZeneca, Bayer, Galapagos, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and Sanofi-Genzyme; receiving research funding from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Galapagos, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, and Sanofi-Genzyme; receiving honoraria from Bayer, Galapagos, Mironid, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, and Sanofi-Genzyme; and serving as a scientific advisor or member of American Journal of Kidney Diseases, CJASN, Journal of Nephrology, Kidney360, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, and Nephron Clinical Practice. R.T. Gansevoort has received fees for acting on advisory boards or as a consultant and received grants from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Baxter, Bayer, Mundipharma, and Sanofi-Genzyme; all money is paid to his employing institution. H.J.L. Heerspink is supported by a VIDI (917.15.306) grant from The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research and reports ongoing consultancy agreements with AbbVie, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chinook, CSL Pharma, Dimerix Fresenius, Gilead, Janssen, Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Mundi Pharma, Novo Nordisk, Retrophin, and Travere Pharmaceuticals; receiving research funding from AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Janssen (grant funding directed to employer); and serving on the speakers bureau for AstraZeneca. F.-F. Hou reports consultancy agreements with AbbVie and AstraZeneca; receiving honoraria from AbbVie and AstraZeneca; and serving on the editorial boards of Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension, Kidney Diseases (Basel), Kidney International, and Kidney Medicine. D.W. Kitzman reports consultancy agreements with Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, CinRx, Corvia Medical, DCRI, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and St. Luke's Hospital (Kansas City, MO); owning stock in Gilead; receiving research funding from AstraZeneca, Bayer, the National Institutes of Health, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and St. Luke's Hospital (Kansas City, MO); receiving honoraria from Abbvie, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, CinRx, Corvia Medical, DCRI, Merck, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, and St. Luke's Hospital (Kansas City, MO); and serving as a scientific advisor or member of Bayer, Corvia Medical, and St. Luke's Hospital (Kansas City, MO). D.E. Kohan has received fees for acting on steering committees, on advisory boards, or as a consultant for AbbVie, AstraZeneca, Chinook Therapeutics, Janssen, and Travere Therapeutics and serves on various journals' editorial boards. H. Makino reports consultancy agreements with Boehringer Ingelheim, Teijin, and Travere Therapeutics. J.J.V. McMurray is the director of Global Clinical Trial Partners Ltd.; was a member of the SONAR steering committee; and reports receiving personal lecture fees from Abbott Diabetes Care, Alkem Metabolics, Eris Lifesciences, Hikma, Lupin, Medscape/Heart.Org, ProAdWise Communications, Radcliffe Cardiology, Servier, Sun Pharmaceutical Industries Inc., and The Corpus. J.J.V. McMurray’s employer, Glasgow University, has been paid for his participation in advisory boards organized by AstraZeneca and Novartis. Payments to Glasgow University have also been made for his work on clinical trials, consulting, and other activities with Abbvie, Alnylam, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cardurion, Cytokinetics, Dal-Cor, GSK, Ionis, KBP Biosciences, Novartis, Pfizer, and Theracos. H.-H. Parving reports consultancy agreements with Abbott, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, and Novartis; ownership interest in Merck and Novo Nordisk; and receiving honoraria from Abbott, AbbVie, AstraZeneca, and Novartis. V. Perkovic reports consultancy agreements with AbbVie, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Baxter, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dimerix, Durect, Eli Lilly, Gilead, GSK, Janssen, Merck, Metavant, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Mundipharma, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, PharmaLink, Relypsa, Retrophin, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, Tricida, UpToDate, and Vitae; research support from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (Senior Research Fellowship and Program Grant); serving on steering committees for trials funded by AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, Janssen, Novo Nordisk, Retrophin, and Tricida; and participating in scientific presentations or advisory boards with AbbVie, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Baxter, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dimerix, Durect, Eli Lilly, Gilead, GSK, Janssen, Merck, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Pharmalink, Relypsa, Retrophin, Sanofi, Servier, and Tricida. S. Tobe reports consultancy agreements with HLS Therapeutics, receiving honoraria from AstraZeneca and CHEPPlus, serving as a scientific advisor or member of the American Society of Hypertension Specialists and the Thunder Bay Regional Health Research Institute, other interests/relationships with CHEPPlus, and participating on a steering committee for Bayer Fidelio/Figaro studies and speakers bureaus for Pfizer and Servier. The remaining author has nothing to disclose.

Funding

AbbVie was the sponsor of the SONAR trial.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all SONAR participants and investigators.

H.J.L. Heerspink and S.W. Waijer analyzed and interpreted the data; H.J.L. Heerspink, V. Perkovic, and S.W. Waijer wrote the first draft of the manuscript; all other authors were involved in data interpretation and contributed to revisions for important intellectual content; and all authors read and approved the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Atrasentan: The Difficult Task of Integrating Endothelin A Receptor Antagonists into Current Treatment Paradigm for Diabetic Kidney Disease,” on pages 1775–1778.

Data Sharing Statement

These clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research and will be provided after review and approval of a research proposal and statistical analysis plan and execution of a data sharing agreement by the corresponding author and the SONAR Steering Committee. Data requests can be submitted at any time.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.07340521/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Figure 1. Effect of atrasentan on the doubling of serum creatinine and kidney failure across baseline eGFR and UACR categories.

Supplemental Figure 2. The effect of atrasentan on kidney end points across baseline eGFR and UACR categories in the atrasentan responder population.

Supplemental Figure 3. The effect of atrasentan on heart failure and cardiovascular death across baseline eGFR and UACR categories.

Supplemental Figure 4. The effect of atrasentan on heart failure and heart failure and cardiovascular death across baseline eGFR and UACR categories in the atrasentan responder population.

References

- 1.Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, Berl T, Pohl MA, Lewis JB, Ritz E, Atkins RC, Rohde R, Raz I; Collaborative Study Group : Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 345: 851–860, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, Keane WF, Mitch WE, Parving H-H, Remuzzi G, Snapinn SM, Zhang Z, Shahinfar S; RENAAL Study Investigators : Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 345: 861–869, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jafar TH, Schmid CH, Landa M, Giatras I, Toto R, Remuzzi G, Maschio G, Brenner BM, Kamper A, Zucchelli P, Becker G, Himmelmann A, Bannister K, Landais P, Shahinfar S, de Jong PE, de Zeeuw D, Lau J, Levey AS: Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and progression of nondiabetic renal disease. A meta-analysis of patient-level data. Ann Intern Med 135: 73–87, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossing P, Hommel E, Smidt UM, Parving H-H: Reduction in albuminuria predicts a beneficial effect on diminishing the progression of human diabetic nephropathy during antihypertensive treatment. Diabetologia 37: 511–516, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Remuzzi G, Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Dimitrov BD, de Zeeuw D, Hille DA, Shahinfar S, Carides GW, Brenner BM; RENAAL Study Group : Continuum of renoprotection with losartan at all stages of type 2 diabetic nephropathy: A post hoc analysis of the RENAAL trial results. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 3117–3125, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heerspink HJL, Parving H-H, Andress DL, Bakris G, Correa-Rotter R, Hou F-F, Kitzman DW, Kohan D, Makino H, McMurray JJV, Melnick JZ, Miller MG, Pergola PE, Perkovic V, Tobe S, Yi T, Wigderson M, de Zeeuw D; SONAR Committees and Investigators : Atrasentan and renal events in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (SONAR): A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 393: 1937–1947, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann JFE, Green D, Jamerson K, Ruilope LM, Kuranoff SJ, Littke T, Viberti G; ASCEND Study Group : Avosentan for overt diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 21: 527–535, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group : KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Available at https://kdigo.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/KDIGO_2012_CKD_GL.pdf. Accessed November 3, 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY: Chronic kidney disease and the risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med 351: 1296–1305, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heerspink HJL, Andress DL, Bakris G, Brennan JJ, Correa-Rotter R, Dey J, Hou FF, Kitzman DW, Kohan D, Makino H, McMurray J, Perkovic V, Tobe S, Wigderson M, Parving HH, de Zeeuw D: Rationale and protocol of the Study of Diabetic Nephropathy with AtRasentan (SONAR) trial: A clinical trial design novel to diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Obes Metab 20: 1369–1376, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heerspink HJL, Andress DL, Bakris G, Brennan JJ, Correa-Rotter R, Hou FF, Kitzman DW, Kohan D, Makino H, McMurray J, Perkovic V, Tobe S, Wigderson M, Yi T, Parving HH, de Zeeuw D: Baseline characteristics and enrichment results from the SONAR trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 20: 1829–1835, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altman DG, Andersen PK: Calculating the number needed to treat for trials where the outcome is time to an event. BMJ 319: 1492–1495, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwarzer G, Carpenter J, Rücker G: Meta-Analysis with R (Use-R!), 2015. Available at: http://meta-analysis-with-r.org/. Accessed August 1, 2020

- 15.Viechtbauer W: Conducting meta-analyses in R with the Metafor package. J Stat Softw 36: 1–48, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Therneau TM: A Package for Survival Analysis in S. Version 2, 2015. Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/package=survival. Accessed August 1, 2020

- 17.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM: Modeling Survival Data: Extending the {C}ox Model, New York, Springer, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohan DE, Lambers Heerspink HJ, Coll B, Andress D, Brennan JJ, Kitzman DW, Correa-Rotter R, Makino H, Perkovic V, Hou FF, Remuzzi G, Tobe SW, Toto R, Parving HH, de Zeeuw D: Predictors of atrasentan-associated fluid retention and change in albuminuria in patients with diabetic nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1568–1574, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoekman J, Lambers Heerspink HJ, Viberti G, Green D, Mann JFE, de Zeeuw D: Predictors of congestive heart failure after treatment with an endothelin receptor antagonist. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 490–498, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, Pitt B, Ruilope LM, Rossing P, Kolkhof P, Nowack C, Schloemer P, Joseph A, Filippatos G; FIDELIO-DKD Investigators : Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 383: 2219–2229, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, Bompoint S, Heerspink HJL, Charytan DM, Edwards R, Agarwal R, Bakris G, Bull S, Cannon CP, Capuano G, Chu PL, de Zeeuw D, Greene T, Levin A, Pollock C, Wheeler DC, Yavin Y, Zhang H, Zinman B, Meininger G, Brenner BM, Mahaffey KW; CREDENCE Trial Investigators : Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 380: 2295–2306, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shlipak MG, Tummalapalli SL, Boulware LE, Grams ME, Ix JH, Jha V, Kengne AP, Madero M, Mihaylova B, Tangri N, Cheung M, Jadoul M, Winkelmayer WC, Zoungas S; Conference Participants : The case for early identification and intervention of chronic kidney disease: Conclusions from a Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Controversies Conference. Kidney Int 99: 34–47, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.