Abstract

Background:

Exposed-based psychotherapy is a mainstay of treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and anxious psychopathology. The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and the default mode network (DMN), which is anchored by the mPFC, promote safety learning. Neuromodulation targeting the mPFC might augment therapeutic safety learning and enhance response to exposure-based therapies.

Methods:

To characterize the effects of mPFC neuromodulation on functional connectivity, 17 community volunteers completed resting-state fMRI scans before and after 20 minutes of frontopolar anodal multifocal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). To examine the effects of tDCS on therapeutic safety learning, 24 patients with OCD completed a pilot randomized clinical trial; they were randomly assigned (double-blind, 50:50) to receive active or sham frontopolar tDCS before completing an in vivo exposure and response prevention (ERP) challenge. Changes in subjective emotional distress during the ERP challenge were used to index therapeutic safety learning.

Results:

In community volunteers, frontal pole functional connectivity with the middle and superior frontal gyri increased, while connectivity with the anterior insula and basal ganglia decreased (ps<.001, corrected) after tDCS; functional connectivity between DMN and salience network also decreased after tDCS (ps<.001, corrected). OCD patients who received active tDCS exhibited more rapid therapeutic safety learning (ps<.05) during the ERP challenge than patients who received sham tDCS.

Conclusions:

Frontopolar tDCS may modulate mPFC and DMN functional connectivity and can accelerate therapeutic safety learning. Though limited by small samples, these findings motivate further exploration of the effects of frontopolar tDCS on neural and behavioral targets associated with exposure-based psychotherapies.

Introduction

Approximately 28% of the American population will meet criteria for an anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) during their lifetime.1 Exposure-based psychotherapies are among the most efficacious treatments for these disorders.2, 3 However, partial response and relapse are common, and a sizeable minority of patients is treatment refractory.4, 5

Exposure therapies depend on safety learning, particularly fear extinction,6 a process whereby a fear is inhibited through the acquisition of new safety learning that is promoted by therapeutic exposure.7, 8 The canonical extinction circuit is principally composed of the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC),9 hippocampus, and amygdala.10-12 Meta-analyses of human imaging studies suggest that fear extinction is also associated with activation of the basal ganglia and cortical areas within distributed intrinsic networks, including the default mode network (DMN), which is anchored by the mPFC and posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), the salience network (SN), which is anchored by the anterior insula and dorsal cingulate cortex (dACC), and the executive control network (ECN), which is anchored by the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (dlPFC) and parietal lobes.13 These findings are consistent with recent work showing that DMN activation, particularly in the mPFC, supports fear extinction and is anti-correlated with activation of the SN, particularly the right anterior insula and dorsal cingulate, during the processing of danger and safety cues.14 Abnormalities in fear extinction learning, fronto-limbic circuitry, and the DMN, SN, and ECN are associated with OCD and with response to exposure-based psychopathology.15-26 Moreover, vmPFC and PCC hypoactivity and hyperconnectivity between the mPFC and SN are associated with deficient extinction learning and memory in OCD.27-29

Neuromodulation of the mPFC may alter metabolic activity and functional connectivity of this region but may also impact connectivity of intrinsic networks that include the mPFC or are functionally linked with it.30, 31 Depending on the timing and directionality of these effects, this could augment the processing of danger and safety cues, fear extinction, and the efficacy and efficiency of exposure-based CBT.8, 32, 33 Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) is a relatively safe and inexpensive technique that can modulate the probability of neuronal firing by depolarizing or hyperpolarizing neurons under the anode and cathode, respectively.34 The effects of tDCS can last hours after stimulation35-38 and can modulate functional connectivity of the area(s) being stimulated,39, 40 in addition to remote areas and networks,31 due in part to its effects on LTP-like plasticity.41, 42 In bipolar tDCS, electrical flux is greatest beneath the two electrodes (anode and cathode),43 but the passed current also has significant effects on large areas of surrounding and intervening neural tissue.44, 45 Multifocal tDCS provides far greater spatial precision than bipolar tDCS by using more than two electrodes, typically one stimulation electrode and four or more return electrodes.43-45

Multiple studies have investigated whether bipolar tDCS targeting the mPFC can modulate safety learning in humans.46-53 Three studies have modestly enhanced extinction acquisition in community volunteers by indirectly targeting the vmPFC with tDCS before and during extinction learning.47, 51, 53 One study targeted the vmPFC by passing current between electrodes over the left and right ventrolateral PFC (F7/F8, 10-20 EEG),53 and two studies passed current from an anode placed over the left lateral PFC (AF3) and a cathode over the contralateral mastoid.47, 51 The effects of the latter tDCS montage have also been shown to marginally improve extinction recall in a sample of PTSD patients when applied after extinction training.48 A recent sham-controlled study with community volunteers found no beneficial effects of anodal tDCS over the frontal pole (nasion/Fpz) on extinction acquisition or recall when tDCS was applied during extinction training.52 Lastly, the only study to examine the effects of tDCS on safety learning during therapeutic exposure found that, when administered simultaneously with six sessions of virtual reality exposure, anodal bipolar tDCS targeting the vmPFC (via the ventrolateral PFC) accelerated therapeutic safety learning and reduced PTSD symptomatology more than sham tDCS in a small sample of PTSD patients.54

Twelve studies have examined the effects of tDCS in patients with OCD.55-66 Bipolar tDCS was employed for all, most targeted the dlPFC, supplementary motor area, or orbitofrontal cortex, and most were treatment studies of repeated tDCS.67, 68 The only study to examine the neural effects of tDCS in OCD reported that a single session of bilateral dlPFC tDCS normalized resting state oscillatory dynamics (measured with EEG).59 The only study to examine the effects of tDCS targeting the mPFC in OCD found that, compared to sham and anodal tDCS, cathodal tDCS acutely reduced anxiety provoked with individualized stimuli; anodal tDCS had no effect relative to sham tDCS.65 Given electrode size and positioning (35mm2 electrodes over Fpz and the shoulder), however, it is likely that this montage influenced far more that the mPFC.43, 45, 69

No studies have reported on the neural effects of tDCS montages used to manipulate safety learning, no studies have explored the effects of tDCS on safety learning in OCD, and no studies have explored the effects of multifocal tDCS on safety learning; all have used the less spatially precise bipolar tDCS. To address these gaps, we completed two pilot studies to test the effects of frontopolar multifocal tDCS on resting functional connectivity in a community sample and on exposure-relevant therapeutic safety learning in a sample of patients with OCD.

Materials and Methods

Study 1

Eighteen adult volunteers who denied psychiatric diagnoses were recruited from the greater New Haven area to complete an open-label within-subject study. Volunteers completed a brief phone screen to probe for common psychiatric diagnoses. After completing a Yale Human Investigations Committee (HIC/IRB)-approved (#0803003626) informed consent form, volunteers completed standard tDCS and MRI safety screening tools,70, 71 a demographic form, and self-report ratings of depression, anxiety, and OCD symptoms (Supplementary Table 1).72, 73 Participants then underwent structural MRI and baseline resting state fMRI (rs-fMRI) scans. Volunteers were then escorted to a nearby room to receive 20-minutes of frontopolar anodal multifocal tDCS. Immediately following tDCS, volunteers were returned to the scanner to complete post-tDCS rs-fMRI scans. Participants then completed a tDCS side-effects questionnaire71 and were compensated $50 for their time.

MRI Acquisition and Processing:

Imaging data were collected on a Siemens Prisma 3T system using a 64-channel foam-padded phased array head coil. An HCP-style multiband fMRI sequence was used. A total of four six-minute rs-fMRI runs (504 volumes) were completed; two runs before and two runs after tDCS. Participants were instructed to rest with their eyes open during scanning and were video monitored to ensure they stay awake. Image preprocessing was completed with AFNI software using standard steps (Supplemental Materials).74

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS):

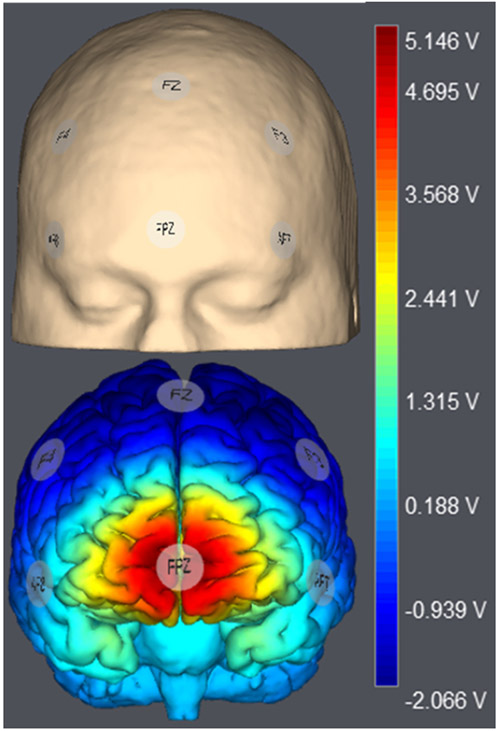

tDCS was delivered using a battery driven Starstim transcranial electric stimulator (Neuroelectrics®, Cambridge, MA) through 1cm2 ceramic electrodes. A single anode was placed over the frontal pole (Fpz), which was surrounded by five return electrodes (AF7, AF8, F3, F4, and Fz at 0.3mA, Figure 1A). Twenty minutes of tDCS was administered to all participants (1.5mA, 30s ramp in/out). Modelling of electrical field distribution suggests that this montage concentrates positive current in the frontal pole beneath the anode, while negative current is of limited strength beneath the five cathodes (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

1.5 mA multifocal tDCS was administered using a Starstim transcranial electric stimulator, with a 1 cm2 anode over Fpz (10-20 EEG) surrounded by five cathodes in a circumferential array (AF3, AF4, F3, FZ, and F4). Simulation of the electrical fields produced by this montage was performed using Stimweaver and showed enhance electrical field potentials throughout the mPFC, particularly the frontopolar cortex and adjacent cortices, with limited effects on surrounding grey matter, including in brain tissue beneath the cathodes.

Study 2

Twenty-four volunteers were drawn from a large pool of individuals with OCD – determined by a doctoral level clinical and structured clinical interview – who were recruited from the greater New Haven community, had previously participated in one or more studies at the Yale OCD Research Clinic, and had agreed to be contacted about additional studies. Co-morbid psychosis, autism, mania, active substance abuse, and major neurological disease were grounds for exclusion, as were serious tDCS contraindications (e.g., history of seizures). Participants were required to be medication free or stably (≥ 4 weeks) medicated with an SRI; anxiolytics and psychostimulants were grounds for exclusion.75, 76 See Supplemental Figure 1 for CONSORT flowchart.

After signing a Yale HIC/IRB-approved consent form (#1412015006), OCD patients completed standard tDCS safety screening tools,70, 71 a demographics form, and self-report ratings of depression, anxiety, and OCD symptoms (Supplementary Table 1).72, 73, 77,78 OCD patients then began the exposure and response prevention (ERP) Challenge (Supplemental Materials). They were first provided standard ERP psychoeducation, taught the 0-to-100-point subjective units of distress scale (SUDS) to rate their emotional distress, and then identified an individualized in vivo ERP exercise (see Supplemental Table 2). OCD patients were then randomized (double-blind, 1:1, parallel) to receive Active- (as per Study 1) or Sham-tDCS (see below) before beginning exposures on the first day of the ERP Challenge. The randomization sequence was generated on random.org by TA. Following tDCS, OCD patients completed five 10-min. trials of in vivo exposure. SUDS was reported every minute of the ERP Challenge. Day 1 concluded with completion of a tDCS side effects questionnaire71 and a 5-point question to assess the degree to which they believed that they received real (active) or placebo (sham) tDCS. OCD patients returned 18-36 hours later to complete five more 10-min. trials of the same exposure exercise; no tDCS was administered on Day 2. Participants were then debriefed and compensated $80.

Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS):

Active-tDCS procedures were identical to those described for Study 1. Sham-tDCS used the same multifocal montage, but no current was delivered between ramping. Both the OCD patients and the experimenter administering the ERP Challenge were blind to experimental assignment, though the staff administering the tDCS were not always blind.

Results

Study 1

We tested whether frontopolar anodal multifocal tDCS modulates functional connectivity in an adult community sample. Participants received active (real) tDCS before and after rs-fMRI scans.

Functional connectivity to a frontopolar seed region was computed following published procedures and standard AFNI software (Supplemental Materials).79 A linear mixed effects model (LME) was calculated using 3dLME to estimate the effects of tDCS on each voxel’s connectivity with this seed region. The main effects of tDCS (pre vs. post) and scan run (first vs. second) and the tDCS*run interaction were modelled as fixed effects and the intercept was modelled as a random effect. Cluster-level thresholding (3dclustersim) using an autocorrelated function (-acf in 3dFWHMx) was applied to the resulting LME group-level effects to control for voxelwise comparisons with a corrected p<.05 (two-tailed given an uncorrected p<.001).80 This resulted in a necessary cluster size of 30.6 face-connected voxels.

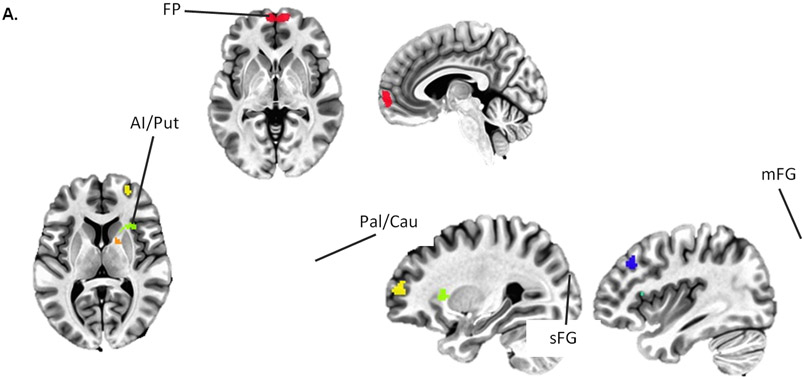

There were significant main effects of tDCS on functional connectivity between the frontal pole and four clusters, all of which were in the right hemisphere, and all of which shifted towards less negative or more positive functional connectivity following tDCS (Table 1 and Figure 2). Negative functional connectivity between the frontal pole and a cluster comprising regions of anterior insula and putamen reduced in negative connectivity, while another cluster within the pallidum and caudate changed from negative to positive connectivity. Positive functional connectivity between the frontal pole and clusters centered in the right middle frontal gyrus (mFG) and superior frontal gyrus (sFG) increased following administration of tDCS (Figure 2B); both clusters changed from negative to positive connectivity.

Table 1.

Summary of peak areas of change in functional connectivity with the frontopolar seed from pre- to post-tDCS (cluster corrected [> 30.6 voxels], p < .001). Cluster size (# voxels) and x,y,z coordinates (MNI) provided.

| LME Main Effects | Pre-tDCS M(SE) |

Post-tDCS M(SE) |

F-value (d) |

|---|---|---|---|

| tDCS (pre vs. post) | |||

| R. Anterior Insula / Putamen −27.0, −20.2, +7.5 (50 vox) |

−0.211 (0.016) |

−0.078 (0.023) |

20.55 (2.27) |

| R. Pallidum / Caudate −19.5, −2.8, +5.0 (34 vox) |

−0.118 (0.042) |

0.026 (0.041) |

34.67 (2.94) |

| R. Superior Frontal Gyrus −37.0, −30.2, +35.0 (34 vox) |

−0.004 (0.013) |

0.111 (0.017) |

19.75 (2.22) |

| R. Middle Frontal Gyrus −27.0, −57.8, +10.0 (44 vox) |

−0.054 (0.041) |

0.108 (0.041) |

22.35 (2.36) |

Figure 2.

(A) Seed-based functional connectivity analyses with stringent cluster correction (p < .001, cluster sizes > 31 voxels) before and after administration of tDCS identified reduced negative functional connectivity between the frontopolar (FP) seed (red) and the right anterior insula / putamen (AI/Put; green) and pallidum / caudate (Pal/Cau; orange) and increased functional connectivity between the FP and the right superior and middle frontal gryi ([sFG] blue and [mFG] yellow). (B) Mean connectivity between FP and each of these clusters before and after tDCS.

To explore the effects of frontopolar multifocal anodal tDCS on inter-network connectivity, we conducted independent component analysis (ICA) of resting state data using published methods (Supplemental Materials).74, 81, 82 Data were combined across all four scan runs for estimation of independent components. To identify networks for second-level analyses, artifact networks (e.g., motion or ventricle networks) were discarded and all remaining functional networks were visually inspected for overlap with the frontal pole seed or with clusters identified in the seed-based analysis. This resulted in the selection of seven networks: the SN, the right ECN (frontoparietal), three components of the DMN (ventral, posterior, medial), and two striatal networks. LME models (MATLAB fitlme.m) were used to examine the effects of tDCS on connectivity between the selected networks; intercept, tDCS (pre vs. post), scan run (first vs. second), and tDCS*run were modelled as fixed effects and the intercept was modelled as a random effect. Bonferroni adjustment was used to correct for familywise error.

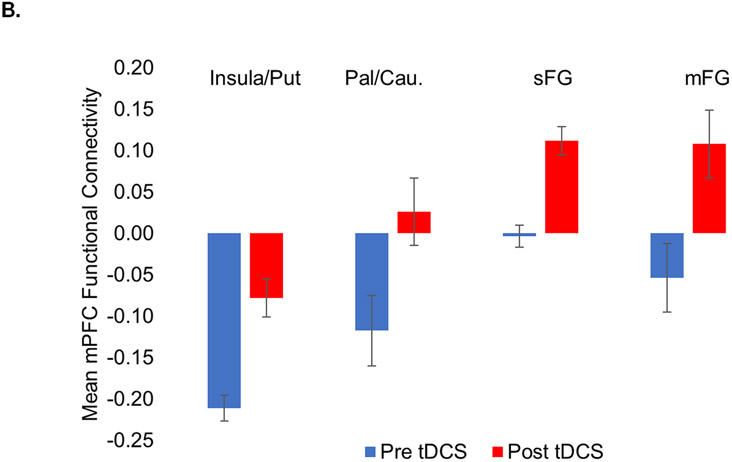

The main effect of tDCS was significant (ps≤.007) in three models, all of which included the SN and a DMN component (Figure 3A). Negative intercept coefficients indicate that the SN was anticorrelated with all three DMN components at baseline (pre-tDCS). Significant positive main effects of tDCS indicate that these anticorrelations were reduced following administration of tDCS (ps≤0.005; Table 2 and Figure 3B). The main effects of tDCS for all remaining contrasts were non-significant following correction for multiple comparisons (ps>.007), including contrasts between the SN and the right ECN and the two striatal networks.

Figure 3.

Inter-network connectivity between the salience network (SN) and subnetworks of the default mode network ([DMN] ventral, posterior, and medial) significantly (ps < .005, significant after Bonferroni correction) decreased following administration of frontopolar tDCS.

Table 2.

Fixed effect estimates (linear mixed effects model) of the intercept and the main effect of tDCS on connectivity between the salience network (SN) and subnetworks of the default mode network (DMN). All effects are significant with Bonferroni correction for familywise error (ps ≤ .007).

| (Inter-Network Connectivity) |

Intercept B (SE) |

tDCS B (SE) |

Upper - Lower C.I. (95%) |

Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SN to Anterior DMN | −0.21 (0.03) | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.02 to 0.09 | 0.73 |

| SN to Posterior DMN | −0.30 (0.03) | 0.05 (0.02) | 0.02 to 0.08 | 0.77 |

| SN to Ventral/Medial DMN | −0.12 (0.03) | 0.06 (0.02) | 0.03 to 0.09 | 0.94 |

Study 2

We next tested whether frontopolar anodal multifocal tDCS can enhance therapeutic safety learning in patients with OCD. Participants were randomized to receive either active (real) or sham (placebo) tDCS before the first of two one-hour individualized in vivo exposure sessions, which were modeled on standard therapeutic exercises during ERP (see Methods).

All analyses were completed using SPSS 22.83 There were no significant differences in age or the distribution of gender and race between active and sham tDCS groups (all ps > .10; Supplemental Table 1). There were also no significant differences in the severity of OCD, anxiety, or depressive symptoms, nor were there differences in the percent of those on psychotropic medications or SRIs at the time of the experiment (all ps>.10; Supplemental Table 1). There were no significant differences in SUDS ratings (ps>.10) immediately before or after tDCS (but before beginning exposure; Supplemental Figure 5A). No unanticipated harm or effects were reported in either group. Importantly, most participants reported that they believed they were receiving Active stimulation, with no difference in confidence between groups (Supplemental Figure 5B), suggesting that our Sham condition and blinding were effective.

LME was used to examine the effects of tDCS on within- and between-trial safety learning during Day 1 of the ERP Challenge (Table 3). The intercept, mins (1-10), trials (1-5), group (sham tDCS [0] vs. active tDCS [1]) and all two- and three-way interactions were modeled as fixed effects. The intercept, mins, and trials were also modelled as random effects. Only fixed effects are reported. Power analyses for LME suggest that a sample of 24 (12 per group) would be sufficient to observe a significant group by trial effect (α = .05) given a large effect size (r2=.21)84, 85 and 1–β=.84.86

Table 3.

Linear mixed effects modeling of within- (mins) and between-trial (trials) learning during Day 1 of exposure with response prevention (ERP) challenge among OCD patients who received active tDCS (n = 12) or sham tDCS (n = 12) immediately before completing five 10-min trials of in vivo exposure. The significant group*mins and group*trials interactions identify accelerated within- and between-trial extinction learning in the active tDCS group relative to the sham tDCS group (see Figure 4).

| Fixed Factors | Beta (SE) | 95% C.I. Lower |

Upper |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 51.41 (4.40) | 42.33 | 60.48 |

| Mins | −.49 (.31) | −1.12 | 0.14 |

| Trials | −2.47 (1.30) | −5.15 | 0.21 |

| Group | −5.54 (6.22) | −18.37 | 7.30 |

| Mins*Trials | −.01 (.06) | −0.12 | 0.11 |

| Group*Mins | −1.67 (.44)** | −2.56 | −0.78 |

| Group*Trials | −3.83 (1.84)* | −7.63 | −0.04 |

| Group*Mins*Trials | .31 (.08)** | 0.15 | 0.46 |

Note

= p < .05

= p < .01. SUDS = Subjective Units of Distress

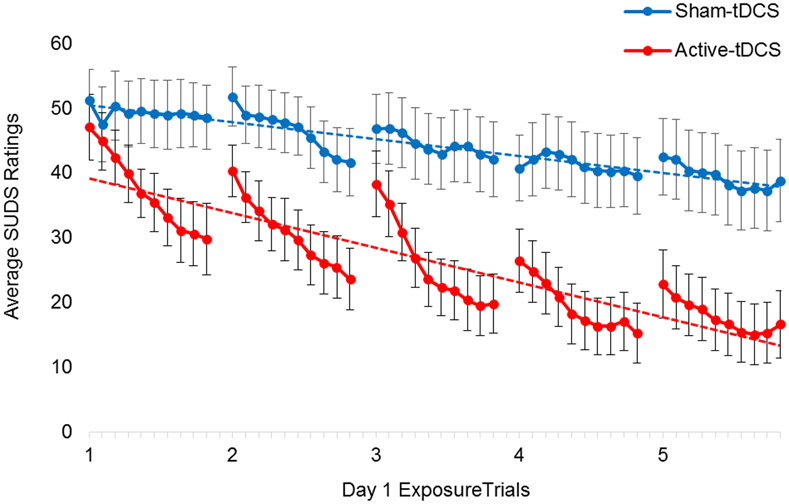

There was a significant group*mins*trials interaction (β=0.31, 95%C.I. = 0.15 to 0.46), suggesting that the mins*trials interaction varied by experimental group. Within-trial reductions in SUDS were greater for OCD patients in the active-tDCS group than for those in the sham-tDCS group (Figure 4; group*mins β=−1.67, 95%C.I. = −2.56 to −0.78). Similarly, between-trial reductions in SUDS were greater for OCD patients in the active-tDCS group than in the sham-tDCS group (Figure 4; group*trials β=−3.83, 95%C.I. = −7.63 to −0.05). On average, OCD patients in the active-tDCS group reported a 64.6% reduction in SUDS from the beginning of the first trial to the end of the last trial of the ERP Challenge on Day 1, whereas those in the sham-tDCS group reported a 24.2% reduction (t[22]=5.58, p<.01).

Figure 4.

Despite nearly identical SUDS ratings at the beginning of the ERP Challenge (min. 1 of trial 1), OCD patients who received active tDCS reported significantly greater within-trial (solid lines, p ≤ .05) and between-trial (dashed lines, p ≤ .01) therapeutic extinction learning than those who received sham stimulation.

Note. SUDS = Subjective Units of Distress (0-100)

An LME model was used to examine the return of fear on day 2. The intercept, group, and time were all modelled as fixed effects; time was defined as SUDS ratings from the end of the last exposure trial on Day 1 (coded as 0) and the beginning of the first trial on Day 2 (coded as 1). Return of fear was similar across the two experimental groups (group*time β= 0.83, 95%C.I. = −8.24 to 29.91). See Supplemental Table 2 and Figure 6.

Discussion

The present findings suggest that multifocal anodal frontopolar tDCS may acutely modulate resting mPFC and DMN functional connectivity in a community sample and can potentiate safety learning during therapeutic exposure in a sample of patients with OCD. Study 1 joins a growing body of research showing that tDCS can influence both local and remote regions and networks. Study 2 is the first to explore the effects of multifocal tDCS safety learning in any sample, including OCD; no published work has reported the effects of tDCS on safety learning in the context of therapeutic exposure or extinction of conditioned fear in OCD patients. Although a recent study reported that bipolar cathodal tDCS over the frontal pole reduced anxiety induced by an individualized in vivo symptom provocation task, this study did not examine safety learning.65 Similar to the present findings (Supplemental Figure 5A), this study also failed to detect acute anxiolytic effects of anodal frontopolar tDCS.65 Like research showing that tDCS can be used with SRIs to augment the treatment of OCD,57, 60, 62, 64, 66 frontopolar tDCS may be used accelerate or strengthen therapeutic safety learning in OCD and other patient populations treated with exposure-based CBT. This may shorten treatment duration, improve efficacy, and may ultimately provide an additional treatment option for treatment refractory patients.32

Most of the clusters identified in our seed-based analysis are contained within the DMN, SN, and right ECN (Figure 2A and Supplemental Figure 4). Functional connectivity between the frontal pole and right anterior insula were anticorrelated at baseline but moved toward zero following tDCS. Similarly, anticorrelations between the SN and all three DMN subnetworks were significantly reduced following tDCS. The observed effects of frontopolar tDCS on therapeutic safety learning may be mediated by modulation of such inter-network relationships.87 SN activation, particularly in the right anterior insula, is triggered by salient cues (e.g., threatening stimuli), which then inhibits the DMN and activates the ECN.88-90 Accordingly, reduced anticorrelations between the DMN and SN, as was found in the present study, may raise the threshold at which SN activation could inhibit or “switch off” the DMN. Reduced DMN inhibition during the processing of emotionally arousing and salient stimuli (e.g., a contaminated object) may then promote safety learning during therapeutic exposure.13, 14 This is speculative, since we did not measure brain activity during our safety learning task.

Unexpectedly, we also observed significant reductions in functional connectivity between the frontal pole and subcortical reward circuitry, particularly in the right striatum, following administration of frontopolar tDCS (Figure 2A and Supplemental Figure 3). This includes areas associated with fear extinction, the detection of safety signals, and approach behaviors.13, 91,92 Elevated striatal activity is also seen in individuals with OCD, both at rest and upon symptom provocation, and is moderated by treatment.93, 94 The two striatal networks identified in ICA analyses showed no significant changes in connectivity following frontopolar tDCS. However, the SN included areas that overlapped with the right anterior insula/putamen cluster identified in seed-based analyses. In our patient sample, tDCS may have modulated striatal activity or connectivity and associated obsessions, compulsive urges, or emotional distress caused by the exposure exercise. Future research should examine this idea in the context of fMRI-based OCD symptom provocation paradigms.95, 96

Although promising, these findings have several important limitations. Sample sizes were relatively small for both studies and important details about the OCD sample was not assessed (e.g., ERP treatment history); replication with larger and well-characterized samples is necessary. Imaging and behavioral data were collected in distinct samples. This was necessary because our behavioral safety learning task was designed to recapitulate procedures used during ERP for OCD and was not compatible with MRI, but it weakens linkage of the two studies. The neural effects of frontopolar tDCS in community and OCD samples may differ. Subjective ratings of emotional distress were used to measure emotional arousal and safety learning. The effects of frontopolar tDCS on objective measures of safety learning (e.g., heart rate changes) may differ. Future research should also include objective psychophysiological measures. Lastly, study one utilized a within-subject design and lacked a control group. While within-subject functional connectivity is largely stable over time,97 a well-powered, double-blind, sham-controlled fMRI study is needed to make stronger inferences. Study 2, conversely, utilized a double-blind, sham-controlled design. The OCD subject and the experimenter administering the ERP Challenge were both blind to the experimental condition, but the experimenter administering tDCS was not always blind. Predicted difficulty of exposures during exposure planning were nearly identical across the two groups, as were SUDS ratings immediately before and after tDCS administration and during the first several minutes of the first exposure trial. Nonetheless, replication efforts should ensure blinding of all individuals involved in data collection efforts. Ideally, future research should attempt to integrate stimulation, imaging, and extinction learning or therapeutic exposure into a single, double-blind, placebo-controlled study to test if changes in functional activation or connectivity mediate the effects of frontopolar tDCS on safety learning.

Conclusions

Limitations aside, the present findings are both novel and promising. To the authors’ knowledge, these are the first studies to examine both behavioral and neurobiological target engagement of tDCS in the context of safety learning or therapeutic exposure. The present findings have clear implications for the treatment of OCD, anxiety, and related disorders. If replicated with larger samples and extended and over multiple sessions of tDCS and exposure, this strategy may lead to a novel means to accelerate recovery, reduce dropout, or improve response rates in the exposure-based treatment of OCD and anxious pathology.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Eileen Billingslea, MA, and Suzanne Wasylink, RN-C, for their assistance with IRB and clinical trial compliance, subject recruitment and screening, and budget management. Portions of these data were presented at annual conferences for the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP) and Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA).

Disclosures

Dr. Adams and the reported studies were supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; K23MH111977, T32MH062994, and L30MH111037). Study one was also supported, in part, by the Clinical Neurosciences Division of the National Center for PTSD and the Department of Veteran Affairs. Brain stimulation equipment was loaned by Starstim® to support study pilots and was purchased using funds from the Detre Foundation (R13306). Study two was supported, in part, by an International Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Foundation (IOCDF) Young Investigator Award and an American Psychiatric Association (APA) Psychiatric Fellowship Award (R12965). These studies were also supported by the State of Connecticut through its support of the Ribicoff Research Facilities at the Connecticut Mental Health Center. Dr. Anticevic is supported by the NIMH (R01MH108590). Dr. Abdallah is supported by the Beth K. and Stuart Yudofsky Chair in the Neuropsychiatry of Military Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome. Dr. Pittenger is supported by the Taylor Family Foundation and the NIMH (R01MH116038 and K24MH121571). The views in this article are those of the authors, not of the State of Connecticut or of other funders.

Dr. Adams, Dr. Cisler, Dr. Kelmendi, Ms. George, Mr. Kichuck, and Mr. Averill have no financial disclosures/conflicts to report. Dr. Anticevic consults and holds equity in Blackthorn Therapeutics. Dr. Abdallah has served as a consultant, speaker and/or on advisory boards for Genentech, Janssen, Psilocybin Labs, Lundbeck, Guidepoint and FSV7, and editor of Chronic Stress for Sage Publications, Inc.; He also filed a patent for using mTORC1 inhibitors to augment the effects of antidepressants (Aug 20, 2018). Dr. Pittenger serves as a consultant for Biohaven, Teva, Lundbeck, Brainsway, and CH-TAC receives royalties and/or honoraria from Oxford University Press and Elsevier, and has filed a patent on the use of NIRS neurofeedback in the treatment of anxiety, which is not relevant to the current work.

Footnotes

Data Sharing and Data Accessibility: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Trial Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03572543

References

- 1.Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, et al. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 2012; 21: 169–184. DOI: 10.1002/mpr.1359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuerk PW. Starting from something: augmenting exposure therapy and methods of inquiry. American Journal of Psychiatry 2014; 171: 1034–1037. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14070880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams TG, Brady RE, Lohr JM, et al. A meta-analysis of CBT components for anxiety disorders. The Behavior Therapist 2015; 38: 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNally RJ. Mechanisms of exposure therapy: how neuroscience can improve psychological treatments for anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychology Review 2007; 27: 750–759. DOI: 10.1016/j.cpr.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hofmann SG and Smits JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2008; 69: 621–632. DOI: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singewald N, Schmuckermair C, Whittle N, et al. Pharmacology of cognitive enhancers for exposure-based therapy of fear, anxiety and trauma-related disorders. Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2015; 149: 150–190. DOI: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2014.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters J, Kalivas PW and Quirk GJ. Extinction circuits for fear and addiction overlap in prefrontal cortex. Learning & Memory 2009; 16: 279–288. DOI: 10.1101/lm.1041309 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Craske MG, Treanor M, Conway CC, et al. Maximizing exposure therapy: an inhibitory learning approach. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2014; 58: 10–23. DOI: 10.1016/j.brat.2014.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phelps EA, Delgado MR, Nearing KI, et al. Extinction learning in humans: Role of the amygdala and vmPFC. Neuron 2004; 43: 897–905. Article. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milad MR and Quirk GJ. Fear extinction as a model for translational neuroscience: Ten years of progress. Annual Review of Psychology 2012; 63: 129–151. Review. DOI: 10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sehlmeyer C, Schöning S, Zwitserlood P, et al. Human fear conditioning and extinction in neuroimaging: a systematic review. PloS one 2009; 4: e5865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moustafa AA, Gilbertson MW, Orr SP, et al. A model of amygdala-hippocampal-prefrontal interaction in fear conditioning and extinction in animals. Brain and Cognition 2013; 81: 29–43. DOI: 10.1016/j.bandc.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fullana MA, Albajes-Eizagirre A, Soriano-Mas C, et al. Fear extinction in the human brain: A meta-analysis of fMRI studies in healthy participants. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2018; 88: 16–25. DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marstaller L, Burianová H and Reutens DC. Adaptive contextualization: a new role for the default mode network in affective learning. Human Brain Mapping 2017; 38: 1082–1091. DOI: 10.1002/hbm.23442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berry AC, Rosenfield D and Smits JAJ. Extinction retention predicts improvement in social anxiety symptoms following exposure therapy. Depression and Anxiety 2009; 26: 22–27. DOI: 10.1002/da.20511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peres JF, Newberg AB, Mercante JP, et al. Cerebral blood flow changes during retrieval of traumatic memories before and after psychotherapy: a SPECT study. Psychological Medicine 2007; 37: 1481–1491. DOI: 10.1017/S003329170700997X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klumpp H, Keutmann MK, Fitzgerald DA, et al. Resting state amygdala-prefrontal connectivity predicts symptom change after cognitive behavioral therapy in generalized social anxiety disorder. Biology of Mood & Anxiety Disorders 2014; 4: 1–7. DOI: 10.1186/s13587-014-0014-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ball TM, Knapp SE, Paulus MP, et al. Brain activation during fear extinction predicts exposure success. Depression and Anxiety 2017; 34: 257–266. DOI: 10.1002/da.22583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forcadell E, Torrents-Rodas D, Vervliet B, et al. Does fear extinction in the laboratory predict outcomes of exposure therapy? A treatment analog study. International Journal of Psychophysiology 2017; 121: 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lange I, Goossens L, Michielse S, et al. Neural responses during extinction learning predict exposure therapy outcome in phobia: results from a randomized-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020; 45: 534–541. DOI: 10.1038/s41386-019-0467-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raeder F, Merz CJ, Margraf J, et al. The association between fear extinction, the ability to accomplish exposure and exposure therapy outcome in specific phobia. Scientific Reports 2020; 10: 1–11. DOI: ARTN 4288 10.1038/s41598-020-61004-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scheveneels S, Boddez Y, Vervliet B, et al. The validity of laboratory-based treatment research: Bridging the gap between fear extinction and exposure treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2016; 86: 87–94. DOI: 10.1016/j.brat.2016.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waters AM and Pine DS. Evaluating differences in Pavlovian fear acquisition and extinction as predictors of outcome from cognitive behavioural therapy for anxious children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2016; 57: 869–876. DOI: 10.1111/jcpp.12522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feusner J, Moody T, Lai TM, et al. Brain connectivity and prediction of relapse after cognitive-behavioral therapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2015; 6: 74. DOI: 10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moody T, Morfini F, Cheng G, et al. Mechanisms of cognitive-behavioral therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder involve robust and extensive increases in brain network connectivity. Translational Psychiatry 2017; 7: e1230. DOI: 10.1038/tp.2017.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reggente N, Moody TD, Morfini F, et al. Multivariate resting-state functional connectivity predicts response to cognitive behavioral therapy in obsessive–compulsive disorder. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2018; 115: 2222–2227. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1716686115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Milad MR, Furtak SC, Greenberg JL, et al. Deficits in conditioned fear extinction in obsessive-compulsive disorder and neurobiological changes in the fear circuit. JAMA Psychiatry 2013; 70: 608–618. DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milad MR, Pitman RK, Ellis CB, et al. Neurobiological basis of failure to recall extinction memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biological Psychiatry 2009; 66: 1075–1082. Article. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apergis-Schoute AM, Gillan CM, Fineberg NA, et al. Neural basis of impaired safety signaling in Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2017; 114: 3216–3221. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1609194114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raij T, Nummenmaa A, Marin MF, et al. Prefrontal Cortex Stimulation Enhances Fear Extinction Memory in Humans. Biological Psychiatry 2018; 84: 129–137. Article. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wörsching J, Padberg F, Goerigk S, et al. Testing assumptions on prefrontal transcranial direct current stimulation: Comparison of electrode montages using multimodal fMRI. Brain Stimul 2018; 11: 998–1007. DOI: 10.1016/j.brs.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marin MF, Camprodon JA, Dougherty DD, et al. Device-based brain stimulation to augment fear extinction: implications for PTSD treatment and beyond. Depression and Anxiety 2014; 31: 269–278. DOI: 10.1002/da.22252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Craske MG, Kircanski K, Zelikowsky M, et al. Optimizing inhibitory learning during exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2008; 46: 5–27. Article. DOI: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nitsche MA, Cohen LG, Wassermann EM, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation: State of the art 2008. Brain Stimulation 2008; 1: 206–223. DOI: 10.1016/j.brs.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stagg CJ, Best JG, Stephenson MC, et al. Polarity-sensitive modulation of cortical neurotransmitters by transcranial stimulation. The Journal of Neuroscience 2009; 29: 5202–5206. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4432-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stagg CJ and Nitsche MA. Physiological basis of transcranial direct current stimulation. Neuroscientist 2011; 17: 37–53. DOI: 10.1177/1073858410386614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nitsche MA and Paulus W. Sustained excitability elevations induced by transcranial DC motor cortex stimulation in humans. Neurology 2001; 57: 1899–1901. DOI: 10.1212/wnl.57.10.1899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nitsche MA and Paulus W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. The Journal of Physiology 2000; 527: 633–639. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peña-Gómez C, Sala-Lonch R, Junqué C, et al. Modulation of large-scale brain networks by transcranial direct current stimulation evidenced by resting-state functional MRI. Brain Stimulation 2012; 5: 252–263. DOI: 10.1016/j.brs.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kunze T, Hunold A, Haueisen J, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation changes resting state functional connectivity: A large-scale brain network modeling study. Neuroimage 2016; 140: 174–187. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fritsch B, Reis J, Martinowich K, et al. Direct Current Stimulation Promotes BDNF-Dependent Synaptic Plasticity: Potential Implications for Motor Learning. Neuron 2010; 66: 198–204. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kelly C and Castellanos FX. Strengthening Connections: Functional Connectivity and Brain Plasticity. Neuropsychology Review 2014; 24: 63–76. DOI: 10.1007/s11065-014-9252-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu A, Voroslakos M, Kronberg G, et al. Immediate neurophysiological effects of transcranial electrical stimulation. Nature Communications 2018; 9: 5092. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-018-07233-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruffini G, de Lara CM-R, Martinez-Zalacain I, et al. Optimized Multielectrode tDCS Modulates Corticolimbic Networks. Brain Stimulation 2017; 10: e14–e14. DOI: 10.1016/j.brs.2016.11.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruffini G, Fox MD, Ripolles O, et al. Optimization of multifocal transcranial current stimulation for weighted cortical pattern targeting from realistic modeling of electric fields. Neuroimage 2014; 89: 216–225. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Adams TG Jr, Wesley M and Rippey C. Transcranial Electric Stimulation and the Extinction of Fear. The Clinical Psychologist 2020; 74: 5–14. DOI: https://div12.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/tCP-Fall-2020.pdf. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van't Wout M, Mariano TY, Garnaat SL, et al. Can transcranial direct current stimulation augment extinction of conditioned fear? Brain Stimulation 2016; 9: 529–536. DOI: 10.1016/j.brs.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van't Wout M, Longo SM, Reddy MK, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation may modulate extinction memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Brain and Behavior 2017; 7: e00681. Article. DOI: 10.1002/brb3.681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ganho-Avila A, Goncalves OF, Guiomar R, et al. The effect of cathodal tDCS on fear extinction: A cross-measures study. PLoS One 2019; 14: e0221282. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lipp J, Draganova R, Batsikadze G, et al. Prefrontal but not cerebellar tDCS attenuates renewal of extinguished conditioned eyeblink responses. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory 2020; 170: 107137. DOI: 10.1016/j.nlm.2019.107137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vicario CM, Nitsche MA, Hoysted I, et al. Anodal transcranial direct current stimulation over the ventromedial prefrontal cortex enhances fear extinction in healthy humans: A single blind sham-controlled study. Brain Stimulation 2020; 13: 489–491. Letter. DOI: 10.1016/j.brs.2019.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abend R, Jalon I, Gurevitch G, et al. Modulation of fear extinction processes using transcranial electrical stimulation. Translational Psychiatry 2016; 6: e913. DOI: 10.1038/tp.2016.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dittert N, Huttner S, Polak T, et al. Augmentation of Fear Extinction by Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS). Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 2018; 12: 76. Article. DOI: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van 't Wout-Frank M, Shea MT, Larson VC, et al. Combined transcranial direct current stimulation with virtual reality exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder: Feasibility and pilot results. Brain Stimulation 2019; 12: 41–43. Article. DOI: 10.1016/j.brs.2018.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bation R, Poulet E, Haesebaert F, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: An open-label pilot study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2016; 65: 153–157. DOI: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.D'Urso G, Brunoni AR, Mazzaferro MP, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: A randomized, controlled, partial crossover trial. Depress Anxiety 2016; 33: 1132–1140. DOI: 10.1002/da.22578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dadashi M, Yousefi Asl V and Morsali Y. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Versus Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation for Augmenting Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Patients. Basic Clin Neurosci 2020; 11: 111–120. DOI: 10.32598/bcn.11.1.13333.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dinn WM, Aycicegi-Dinn A, Göral F, et al. Treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: Insights from an open trial of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) to design a RCT. Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research 2016; 22: 146–154. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ghaffari H, Yoonessi A, Darvishi MJ, et al. Normal Electrical Activity of the Brain in Obsessive-Compulsive Patients After Anodal Stimulation of the Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex. Basic Clin Neurosci 2018; 9: 135–146. DOI: 10.29252/nirp.Bcn.9.2.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gowda SM, Narayanaswamy JC, Hazari N, et al. Efficacy of pre-supplementary motor area transcranial direct current stimulation for treatment resistant obsessive compulsive disorder: A randomized, double blinded, sham controlled trial. Brain Stimul 2019; 12: 922–929. DOI: 10.1016/j.brs.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Harika-Germaneau G, Heit D, Chatard A, et al. Treating refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder with transcranial direct current stimulation: An open label study. Brain and behavior 2020; 10: e01648–e01648. DOI: 10.1002/brb3.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kumar S, Kumar N and Verma R. Safety and efficacy of adjunctive transcranial direct current stimulation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: An open-label trial. Indian J Psychiatry 2019; 61: 327–334. DOI: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_509_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Najafi K, Fakour Y, Zarrabi H, et al. Efficacy of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation in the Treatment: Resistant Patients who Suffer from Severe Obsessive-compulsive Disorder. Indian J Psychol Med 2017; 39: 573–578. DOI: 10.4103/ijpsym.Ijpsym_388_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Silva RdMFd, Brunoni AR, Goerigk S, et al. Efficacy and safety of transcranial direct current stimulation as an add-on treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized, sham-controlled trial. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021; 46: 1028–1034. DOI: 10.1038/s41386-020-00928-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Todder D, Gershi A, Perry Z, et al. Immediate Effects of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation on Obsession-Induced Anxiety in Refractory Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Pilot Study. J ect 2018; 34: e51–e57. DOI: 10.1097/yct.0000000000000473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yoosefee S, Amanat M, Salehi M, et al. The safety and efficacy of transcranial direct current stimulation as add-on therapy to fluoxetine in obsessive-compulsive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled, clinical trial. BMC Psychiatry 2020; 20: NA. Report. DOI: ARTN 570 10.1186/s12888-020-02979-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rachid F. Transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder? A qualitative review of safety and efficacy. Psychiatry Res 2019; 271: 259–264. DOI: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brunelin J, Mondino M, Bation R, et al. Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: A Systematic Review. Brain Sci 2018; 8: 37. DOI: 10.3390/brainsci8020037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chib VS, Yun K, Takahashi H, et al. Noninvasive remote activation of the ventral midbrain by transcranial direct current stimulation of prefrontal cortex. Translational psychiatry 2013; 3: e268–e268. DOI: 10.1038/tp.2013.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bikson M, Datta A and Elwassif M. Establishing safety limits for transcranial direct current stimulation. Clinical Neurophysiology 2009; 120: 1033–1034. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.03.018 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Brunoni AR, Amadera J, Berbel B, et al. A systematic review on reporting and assessment of adverse effects associated with transcranial direct current stimulation. The International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology 2011; 14: 1133–1145. DOI: 10.1017/S1461145710001690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Löwe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, et al. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). Journal of Affective Disorders 2004; 81: 61–66. DOI: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine 2006; 166: 1092–1097. DOI: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cisler JM, Esbensen K, Sellnow K, et al. Differential Roles of the Salience Network During Prediction Error Encoding and Facial Emotion Processing Among Female Adolescent Assault Victims. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging 2019; 4: 371–380. DOI: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2018.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bouton ME, Kenney FA and Rosengard C. State-dependent fear extinction with two benzodiazepine tranquilizers. Behavioral Neuroscience 1990; 104: 44–44. DOI: 10.1037//0735-7044.104.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Spiegel DA and Bruce TJ. Benzodiazepines and exposure-based cognitive behavior therapies for panic disorder: conclusions from combined treatment trials. American Journal of Psychiatry 1997; 154: 773–781. DOI: 10.1176/ajp.154.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Abramowitz JS, Deacon BJ, Olatunji BO, et al. Assessment of obsessive-compulsive symptom dimensions: Development and evaluation of the Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. Psychological Assessment 2010; 22: 180–198. DOI: 10.1037/a0018260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Steketee G, Chambless DL, Tran GQ, et al. Behavioral avoidance test for obsessive compulsive disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1996; 34: 73–83. DOI: 10.1016/0005-7967(95)00040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zielinski MJ, Privratsky AA, Smitherman S, et al. Does development moderate the effect of early life assaultive violence on resting-state networks? An exploratory study. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging 2018; 281: 69–77. DOI: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2018.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eklund A, Nichols TE and Knutsson H. Cluster failure: Why fMRI inferences for spatial extent have inflated false-positive rates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2016; 113: 7900–7905. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1602413113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cisler JM, Elton A, Kennedy AP, et al. Altered functional connectivity of the insular cortex across prefrontal networks in cocaine addiction. Psychiatry Research 2013; 213: 39–46. DOI: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Calhoun VD, Adali T, Pearlson GD, et al. A method for making group inferences from functional MRI data using independent component analysis. Human Brain Mapping 2001; 14: 140–151. DOI: DOI 10.1002/hbm.1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.IBM. SPSS Statistics for Windows. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp., 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Manish A, Nueckel K, Mühlberger A, et al. Effects of transcranial direct current stimulation on consolidation of fear memory. Frontiers in psychiatry 2013; 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chib VS, Yun K, Takahashi H, et al. Noninvasive remote activation of the ventral midbrain by transcranial direct current stimulation of prefrontal cortex. Translational psychiatry 2013; 3: e268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kreidler SM, Muller KE, Grunwald GK, et al. GLIMMPSE: Online Power Computation for Linear Models with and without a Baseline Covariate. J Stat Softw 2013; 54. DOI: 10.18637/jss.v054.i10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cisler JM, Steele JS, Lenow JK, et al. Functional reorganization of neural networks during repeated exposure to the traumatic memory in posttraumatic stress disorder: an exploratory fMRI study. J Psychiatr Res 2014; 48: 47–55. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2013.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sridharan D, Levitin DJ and Menon V. A critical role for the right fronto-insular cortex in switching between central-executive and default-mode networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2008; 105: 12569–12574. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0800005105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goulden N, Khusnulina A, Davis NJ, et al. The salience network is responsible for switching between the default mode network and the central executive network: replication from DCM. Neuroimage 2014; 99: 180–190. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sidlauskaite J, Wiersema JR, Roeyers H, et al. Anticipatory processes in brain state switching: Evidence from a novel cued-switching task implicating default mode and salience networks. NeuroImage 2014; 98: 359–365. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Christianson JP, Fernando ABP, Kazama AM, et al. Inhibition of Fear by Learned Safety Signals: A Mini-Symposium Review. The Journal of Neuroscience 2012; 32: 14118–14124. DOI: 10.1523/jneurosci.3340-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Rogan MT, Leon KS, Perez DL, et al. Distinct Neural Signatures for Safety and Danger in the Amygdala and Striatum of the Mouse. Neuron 2005; 46: 309–320. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Chamberlain SR, Blackwell AD, Fineberg NA, et al. The neuropsychology of obsessive compulsive disorder: the importance of failures in cognitive and behavioural inhibition as candidate endophenotypic markers. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 2005; 29: 399–420. DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Chamberlain SR, Menzies L, Hampshire A, et al. Orbitofrontal dysfunction in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and their unaffected relatives. Science 2008; 321: 421–422. DOI: 10.1126/science.1154433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Rauch SL, Shin LM, Dougherty DD, et al. Predictors of Fluvoxamine Response in Contamination-related Obsessive Compulsive Disorder: A PET Symptom Provocation Study. Neuropsychopharmacology 2002; 27: 782–791. DOI: 10.1016/S0893-133X(02)00351-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Baioui A, Pilgramm J, Merz CJ, et al. Neural response in obsessive-compulsive washers depends on individual fit of triggers. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 2013; 7: 143–143. DOI: 10.3389/fnhum.2013.00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Noble S, Scheinost D and Constable RT. A decade of test-retest reliability of functional connectivity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. NeuroImage 2019; 203: 116157. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.