Abstract

Background

It is estimated that up to 75% of cancer survivors may experience cognitive impairment as a result of cancer treatment and given the increasing size of the cancer survivor population, the number of affected people is set to rise considerably in coming years. There is a need, therefore, to identify effective, non‐pharmacological interventions for maintaining cognitive function or ameliorating cognitive impairment among people with a previous cancer diagnosis.

Objectives

To evaluate the cognitive effects, non‐cognitive effects, duration and safety of non‐pharmacological interventions among cancer patients targeted at maintaining cognitive function or ameliorating cognitive impairment as a result of cancer or receipt of systemic cancer treatment (i.e. chemotherapy or hormonal therapies in isolation or combination with other treatments).

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Centre Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, Embase, PUBMED, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and PsycINFO databases. We also searched registries of ongoing trials and grey literature including theses, dissertations and conference proceedings. Searches were conducted for articles published from 1980 to 29 September 2015.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of non‐pharmacological interventions to improve cognitive impairment or to maintain cognitive functioning among survivors of adult‐onset cancers who have completed systemic cancer therapy (in isolation or combination with other treatments) were eligible. Studies among individuals continuing to receive hormonal therapy were included. We excluded interventions targeted at cancer survivors with central nervous system (CNS) tumours or metastases, non‐melanoma skin cancer or those who had received cranial radiation or, were from nursing or care home settings. Language restrictions were not applied.

Data collection and analysis

Author pairs independently screened, selected, extracted data and rated the risk of bias of studies. We were unable to conduct planned meta‐analyses due to heterogeneity in the type of interventions and outcomes, with the exception of compensatory strategy training interventions for which we pooled data for mental and physical well‐being outcomes. We report a narrative synthesis of intervention effectiveness for other outcomes.

Main results

Five RCTs describing six interventions (comprising a total of 235 participants) met the eligibility criteria for the review. Two trials of computer‐assisted cognitive training interventions (n = 100), two of compensatory strategy training interventions (n = 95), one of meditation (n = 47) and one of physical activity intervention (n = 19) were identified. Each study focused on breast cancer survivors. All five studies were rated as having a high risk of bias. Data for our primary outcome of interest, cognitive function were not amenable to being pooled statistically. Cognitive training demonstrated beneficial effects on objectively assessed cognitive function (including processing speed, executive functions, cognitive flexibility, language, delayed‐ and immediate‐ memory), subjectively reported cognitive function and mental well‐being. Compensatory strategy training demonstrated improvements on objectively assessed delayed‐, immediate‐ and verbal‐memory, self‐reported cognitive function and spiritual quality of life (QoL). The meta‐analyses of two RCTs (95 participants) did not show a beneficial effect from compensatory strategy training on physical well‐being immediately (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.12, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.59 to 0.83; I2= 67%) or two months post‐intervention (SMD ‐ 0.21, 95% CI ‐0.89 to 0.47; I2 = 63%) or on mental well‐being two months post‐intervention (SMD ‐0.38, 95% CI ‐1.10 to 0.34; I2 = 67%). Lower mental well‐being immediately post‐intervention appeared to be observed in patients who received compensatory strategy training compared to wait‐list controls (SMD ‐0.57, 95% CI ‐0.98 to ‐0.16; I2 = 0%). We assessed the assembled studies using GRADE for physical and mental health outcomes and this evidence was rated to be low quality and, therefore findings should be interpreted with caution. Evidence for physical activity and meditation interventions on cognitive outcomes is unclear.

Authors' conclusions

Overall, the, albeit low‐quality evidence may be interpreted to suggest that non‐pharmacological interventions may have the potential to reduce the risk of, or ameliorate, cognitive impairment following systemic cancer treatment. Larger, multi‐site studies including an appropriate, active attentional control group, as well as consideration of functional outcomes (e.g. activities of daily living) are required in order to come to firmer conclusions about the benefits or otherwise of this intervention approach. There is also a need to conduct research into cognitive impairment among cancer patient groups other than women with breast cancer.

Plain language summary

Interventions for cognitive impairment due to non‐localised cancer treatment such as chemotherapy or hormonal therapy

The issue

An increasing number of people are surviving and living longer with cancer due to earlier diagnosis, better treatments and an aging population. In turn, there is an increasing number of people with long‐term or long‐lasting effects of cancer and its treatment. For example, up to seven in 10 cancer survivors experience changes in ability regarding memory, learning new things, concentrating, planning and making decisions about their everyday life, as a result of cancer treatment. This is known as cognitive impairment and has a significant impact on the daily activities of cancer survivors. These changes may be caused by non‐localised, systemic cancer treatment, such as chemotherapy and is often called 'chemo‐fog' or 'chemobrain'.

The aim of the review

We reviewed studies that have tested interventions intended to improve cognitive impairment or to maintain cognitive function among people who have been treated with systemic cancer treatments.

What are the main findings?

We identified five eligible studies that described six interventions. These included two studies of computerised cognitive skills practice, two cognitive coping skills training programmes, one meditation intervention and one exercise intervention. All five studies included a total of 235 women who had been treated for breast cancer. The findings suggest that cognitive skills practice and cognitive coping skills training may be useful in improving patient reports and formal assessments of cognition, as well as quality of life. There was insufficient evidence to know if meditation and exercise interventions had any effect on cognition.

What is the quality of the evidence?

The quality of the evidence was low. There were problems with study designs and, so, we need to be cautious about our conclusions.

What are the conclusions?

There is not enough good quality evidence to know if any interventions improve cognitive impairment or maintain cognitive functioning among people who have received systemic treatment for cancer. There are several ongoing trials in the field, which may provide the necessary evidence in the future.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings.

| Compensatory strategy training compared with wait‐list controls for cognitive impairment due to systemic cancer treatment | ||||||

|

Patient or population: Cancer patients with cognitive impairment due to systemic cancer treatment Intervention: Compensatory Strategy Training Comparison: Wait‐list control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Compensatory strategy training | |||||

|

Physical well‐being SF‐36 Physical Component Summary Score 0 to 100, higher scores indicate higher levels of physical well‐being Immediately post‐intervention |

The mean physical well‐being in the control group is 43.1 points1 | The mean physical well‐being in the intervention groups was 1.16pointshigher (5.72 points lower to 8.05 points higher) |

95 (2) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa, b | ||

|

Physical well‐being SF‐36 Physical Component Summary Score 0‐100, higher scores indicate higher levels of physical well‐being Two‐months post‐intervention |

The mean physical well‐being in the control group is 43.1 points | The mean physical well‐being in the intervention groups was 2.04 points lower (8.63 points lower to 4.56 points higher) |

95 (2) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa, b | ||

|

Psychological well‐being SF‐36 Mental Component Summary Score 0 to 100, higher scores indicate higher levels of physical well‐being Immediately post‐intervention |

The mean psychological well‐being in the control group is 50.5 points1 | The mean psychological well‐being in the intervention groups was 5.13 points lower (8.82 points lower to 1.44 points higher) |

95 (2) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa, b | ||

|

Psychological well‐being SF‐36 Mental Component Summary Score 0 to 100, higher scores indicate higher levels of physical well‐being Two‐months post‐intervention |

The mean psychological well‐being in the control group is 50.5 points | The mean psychological well‐being in the intervention groups was 3.42 pointslower (9.90 points lower to 3.06 points higher) |

95 (2) |

⊕⊕⊝⊝ lowa, b | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI).

CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio aRisk of Bias (‐1): One of the studies did not undertake intention‐to‐treat analysis and it is not clear if the randomisation process was fully blinded. bImprecision(‐1): The meta‐analyses report wide confidence intervals. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Control values taken from the following reference (Imayama 2013)

Abbreviations: SF‐36 = Short Form health survey‐ 36 items

Background

Description of the condition

Over the past few decades, survival rates for cancer have improved steadily. Cancer patients are living longer following treatment due to a number of factors. These include earlier detection of their cancer and the development and use of effective treatments (Coleman 2011). However, this increased survival means that long‐term or delayed/late effects of cancer treatment are being observed more frequently among cancer survivors (Treanor 2013). One such long‐term or late effect of cancer treatment is cognitive impairment. At present, there is no consensus about how to define cognitive impairment among cancer patients and there is no common method of diagnosis (Hess 2007). Changes in cognition are measured and defined in different ways. For example, patients can self‐report changes or they can be assessed formally using neuropsychological test batteries to capture changes in cognition objectively. Objective tests are the gold standard method of assessment. Change in terms of impaired functioning may be defined in several ways and at different levels of severity, for example, one standard deviation (SD) change in scores from a previous test, or 1.5 or 2 SD difference in scores from an appropriate comparison group or population norms (Wefel 2011). Cognitive impairment caused by cancer treatment may include a breakdown or change in cognitive processes. Patients may have trouble remembering, learning new things, concentrating, co‐ordinating movements or balance, making decisions that affect their everyday life; they may experience problems with the management or control system in the brain, also known as executive functioning (Nelson 2007). Neuroimaging studies among treated cancer patients have found structural changes and activity reduction in areas of the brain (including prefrontal/frontal cortex and temporal regions (including hippocampus/parahippocampus)) used for cognitive functions such as memory and executive functioning (Gehring 2012; Scherling 2013; Simó 2013).

It is estimated that up to 75 per cent of cancer survivors may experience cognitive impairment as a result of cancer treatment (Bower 2008; Ganz 2001; Harrington 2010; Stein 2008; Treanor 2014). Impairment may be short‐term or long‐lasting (10 or more years) (Ahles 2002; Bower 2008; Koppelmans 2012). The proportion of cancer patients who experience cognitive impairment varies across studies due to different study designs, treatments received by patients, treatment status (e.g. currently receiving treatment or post‐treatment), and how cognitive impairment is defined and assessed (Gehring 2012). Regarding the specific treatments that are associated with the development of cognitive impairment, a strong association has been identified between chemotherapy and cognitive impairment. Often, chemotherapy‐induced cognitive impairment is referred to as 'chemo‐brain' or 'chemo‐fog'.

Several suggestions have been made for the mechanism by which chemotherapy induces cognitive impairment. These include the following:

damage to neurons or nerve cells (Ahles 2007; Merriman 2013; Nelson 2007; Raffa 2011);

damage to deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) structures (Ahles 2007; Conroy 2013; Joshi 2005; Merriman 2013; Nelson 2007; Vardy 2008);

induced hormonal changes (Ahles 2007; Bender 2001; Merriman 2013);

induced anaemia (Hess 2007; Nelson 2007);

inflammatory response of the immune system (Ahles 2007; Ganz 2012; Janelsins 2012a; Merriman 2013; Nelson 2007)

Treatment‐related cognitive impairment may not be limited to chemotherapy. The problem may occur also following hormone therapies and local therapies such as cranial radiation (Bender 2001; Ganz 2012; Nelson 2007; Nelson 2008; Vodermaier 2009). The focus of this review is on systemic therapy, so local radiotherapy is not included. Genetic susceptibility (e.g. presence of apolipoprotein E (apoE) ε4 allele) and level of cognitive reserve (which is dependent on a combination of educational, occupational and lifestyle factors) may also be associated with the development of treatment‐induced cognitive impairment (Ahles 2007; Ahles 2012; Argyriou 2010; Merriman 2013; Nelson 2007). Other factors including symptoms of depression, anxiety, distress and fatigue may contribute to cognitive impairment (Ganz 2012; Hess 2007). Furthermore, studies have demonstrated that cognitive processes may be impaired prior to receiving treatment (Ganz 2012; Hess 2007) (for example, due to distress experienced at the time of cancer diagnosis and anxiety about treatment). The evidence is currently unclear as to how treatment‐induced cognitive impairment and cognitive impairment related to normal aging differ.

Description of the intervention

This review examines the effects of non‐pharmacological interventions designed to improve cognitive function or manage cognitive impairment following receipt of systemic cancer treatments in isolation or in combination with other treatments. Cranial radiation for central nervous system (CNS) tumours (see Cochrane review Day 2014) or metastases are not the focus of this review and were excluded. We undertook a brief scoping review to identify types of non‐pharmacological interventions that have been studied with the aim of improving cognitive impairment or maintaining cognitive functioning among cancer survivors (see Why it is important to do this review).

Three main types of interventions were identified and form the focus of the review.

Cognitive rehabilitation including cognitive training which includes repetitive practice of cognitive skills or processes via structured tasks or activities with the aim of improving cognition through practice by strengthening neural pathways (Ferguson 2012; Martin 2011), and compensatory strategy training which aims to help a patient to manage or cope with their impaired cognitive functioning by learning techniques such as the use of mnemonics to aid memory (Gehring 2012).

Physical activity interventions are hypothesised to work through improved oxygenation and blood flow to the brain, leading to improved cerebrovascular functioning (Nelson 2007), and stress reduction (Ganz 2012). Physical activity interventions include any form of exercise or physical activity which may or may not be aerobic in nature, and which may be undertaken for occupational or recreational purposes.

Meditative/relaxation‐based intervention is defined as a mental exercise that involves reaching a focused state of mind and may include breathing and visualisation exercises (Milbury 2013). Meditative/relaxation‐based interventions may maintain cognitive functioning or improve cognitive impairment directly or indirectly through stress reduction, which may aid regulation of the immune system, particularly the regulation of cytokine production (Ganz 2012; Milbury 2013).

Pharmacological treatments of treatment‐induced cognitive impairment are not eligible for this review. Two other reviews have reported on the commonly experienced side effects of pharmacological interventions as well as their benefits on cognitive functioning (Gehring 2012; Von Ah 2013). Interventions which include herbal compounds (e.g. gingko biloba), diet (e.g. high in antioxidants) or supplements (e.g. vitamin E) are also not eligible because they act on physiological processes in a similar manner to pharmacological agents. Previously published reviews in the area have grouped herbal, dietary and supplement interventions similarly, within the umbrella of pharmacological interventions (Fardell 2011).

Why it is important to do this review

Although cancer treatment‐induced cognitive impairment is usually mild to moderate, it exerts a substantial impact on a survivor's ability to perform everyday tasks. In general, treatment‐induced cognitive impairment may impact on their long‐term quality of life (QoL) and ability to process information to make treatment decisions (Ahles 2002; Ganz 2012; Hess 2007). Impairments in cognitive functioning among younger survivors may impact on their ability to return to work or education, career progression and educational attainment (Nelson 2007). Older cancer survivors may question the balance of benefits and harms of cancer treatment in terms of survival gains and their already increased risk of cognitive impairment due to age (Nelson 2007), as well as the possibility of deficits in functioning and activities of daily living (Kvale 2009). The proportion of cancer patients that develop treatment‐induced cognitive impairment varies and it is important to try to identify characteristics of at‐risk patients so that well‐informed decisions can be made about potential treatment‐related harms whilst being mindful of uncertainty about which specific chemotherapy or hormonal agents are associated with an increased risk of developing cognitive impairment (Cheung 2012). Currently, the focus is on managing treatment‐induced cognitive impairment among cancer patients generally, until specific characteristics and potential risk‐increasing treatments are identified, which might lead to potential prevention strategies. This review is also important because cancer is framed usually as a chronic condition and, as noted above, the population of cancer survivors is increasing and, therefore, the number of cancer survivors living with treatment‐induced cognitive impairment is rising.

Several published reviews of interventions (Fardell 2011; Gehring 2012; Hines 2014; Von Ah 2011; Von Ah 2013) and epidemiology (Craig 2014; Janelsins 2014; McDougall 2014) for cancer‐related cognitive impairment among non‐CNS tumour sites have limitations due to study selection, data extraction or methodological quality appraisal, or the extent of their search in multidisciplinary databases and grey literature. Moreover, these earlier reviews were limited to studies reported in English. We conducted a scoping exercise to inform the planning of our review and found that there are several new studies in this field that were not included in existing reviews. The growing number of studies of non‐pharmacological interventions for treatment‐induced cognitive impairment merits rigorous and systematic attention. Given the prevalence of this condition and the possible preference by cancer survivors for non‐invasive, non‐pharmacological methods of management or alleviation of cognitive dysfunction, it is important to systematically review published and unpublished evidence (with no restrictions by language) on the effects of non‐pharmacological interventions to prevent or ameliorate cognitive impairment following chemotherapy in order to inform clinical and individual decision‐making. Indeed, findings from a review of qualitative studies of cancer survivors with cognitive impairment report that already many individuals may use some of the strategies that form the basis of behavioural interventions (Myers 2013).

Objectives

The primary objective of this review is to evaluate the cognitive effects, non‐cognitive effects, duration and safety of non‐pharmacological interventions among cancer patients targeted at maintaining cognitive function or ameliorating cognitive impairment as a result of cancer or receipt of systemic cancer treatment (i.e. chemotherapy or hormonal therapies in isolation or combination with other treatments). Although it is expected that non‐pharmacological interventions will pose minimal risk to patients, we examined each randomised trial to identify safety as an outcome and incorporate information on intervention safety where possible.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included only randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We excluded non‐randomised studies and trials with a quasi‐experimental method of allocation (e.g. alternation).

We contacted trial authors for further information about their method of randomisation when this was not discernible from the published report in order to decide whether or not to include their study.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria

We included the following types of participants:

patients diagnosed during adulthood (aged 16 years and older) with any tumour type, with exceptions noted under exclusion criteria;

patients who received previous systemic treatment (i.e. chemotherapy or hormonal therapies) in isolation or in combination with other treatments;

patients who received hormone therapy for prophylactic purposes following the treatment of their cancer;

patients from community or clinic settings.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded the following types of participants:

patients who received treatments such as cranial radiation;

childhood‐onset cancer survivors (aged under 16 years old) (childhood‐specific or age‐relevant cognitive functioning and patient‐reported outcome measures to assess outcomes in this group differ from adult measures (Gross‐King 2008)).

patients who received palliative care (because treatment pathways and medication regimens differ between palliative and non‐palliative care patients and these differences may influence intervention adherence (Addington 1995));

patients with primary or metastatic cancer of the brain or central nervous system (CNS) (because of the direct impact of the tumour on the brain and thus cognitive processes (Gehring 2008; Gehring 2010));

patients with non‐melanoma skin cancer (because its epidemiology and treatment differs significantly from other cancers);

patients who received prophylactic cranial radiation (because a Cochrane Review addressing interventions for cognitive impairment following cranial radiation is currently registered and the protocol is under development);

patients from nursing or care home settings (because of the likelihood of co‐morbid dementia or related conditions).

We planned to consider studies which had included both survivors of childhood‐onset and adult‐onset cancers if it was possible to extract data relating specifically to the subgroup of adult‐onset cancer survivors. However, no studies of this kind were identified.

Types of interventions

We considered studies for inclusion in the review if they used non‐pharmacological interventions (including cognitive rehabilitation, physical activity and meditative/relaxation activities) in order to maintain cognitive function or improve cognitive impairment in patients treated with systemic therapies for cancer. We included multi‐component interventions that had a pharmacological element only if the major focus was on the non‐pharmacological intervention.

Regarding control groups, we included studies with a 'no treatment' or 'usual care' group. We planned to include studies which included both an 'active' control group as well as a no treatment group and to use only data from the no treatment control group in comparison to the intervention group. However, no such studies were identified.

We did not apply any exclusion criteria regarding aspects of the intervention such as the duration, frequency of sessions or mode of delivery (e.g. face‐to‐face, computer‐ or web‐based and whether they were delivered on an individual or group basis), but we planned to discuss differences in these features when making comparisons between studies included in the review, if a sufficient number of studies were identified. We included interventions based at home or in the community, in clinics or hospitals or, in research or controlled experimental 'laboratory' settings.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

'Objective' cognitive functioning measured using a validated, standardised test e.g. Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS)

'Subjective' cognitive functioning measured using a validated, self‐report measure e.g. Functional Assessment of Cancer Treatment‐Cognition Function Scale (FACT‐Cog)

Secondary outcomes

Quality of life (QoL) including health‐related quality of life, well‐being and daily functioning measured using a validated, self‐report measure e.g. Short‐Form Health Survey (SF‐36)

Mood‐related outcomes including distress, depression or anxiety, using a validated, self‐report measure e.g. Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS)

Fatigue measured using a validated, self‐report measure e.g. Functional Assessment of Cancer Treatment‐Fatigue Scale (FACT‐F)

Sleep disturbance measured using a validated, self‐report measure e.g. Medical Outcomes Study‐Sleep Scale (MOS‐Sleep)

-

Adherence, assessed as an outcome to identify the extent to which patients follow the allocated intervention

We planned to use adherence in sensitivity analyses or as part of the 'Risk of bias' assessment (for example, we planned to compare trials with at least 80% of patients assessed at end‐point compared to trials with less than 80% of patients assessed at end‐point). However, an insufficient number of studies were identified in order to undertake a sensitivity analysis

Adverse effects e.g. injury in physical activity interventions

Treatment satisfaction

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for papers in all languages and planned to arrange for non‐English language papers to be translated, but no non‐English language papers remained following screening of titles and abstracts.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases to 29 September 2015:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Cochrane Library);

MEDLINE (via OvidSP);

Embase (via OvidSP);

PsycINFO (via OvidSP);

CINAHL (via EBSCO);

PubMed (via National Center for Biotechnology Information).

We searched the databases for publications from 1980, which is the year in which studies examining impairments in cognitive function as a result of cancer treatment began to appear in the literature (Ahles 2012).The search strategies are available in the appendices (Appendix 1; Appendix 2; Appendix 3; Appendix 4; Appendix 5; Appendix 6). We identified all relevant articles in PubMed (where available) and used the 'related articles' feature and performed further searches for newly published articles which may not have been identified from the main database search.

Searching other resources

Unpublished and grey literature

We searched the following sources for ongoing trials:

metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) (http://www.controlled-trials.com/mrct/);

Physician Data Query by the National Cancer Institute (http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq),

ClinicalTrials.gov (http://clinicaltrials.gov/);

National Cancer Institute's List of Cancer Clinical Trials (http://www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials);

World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/).

We asked the principal investigators of any identified unpublished trials for relevant data. We sought information about trials from major co‐operative groups active in this area. We identified conference proceedings and abstracts through ZETOC (http://zetoc.mimas.ac.uk) and WorldCat Dissertations. Where available, we would have included data in the review from any ongoing trials (whilst noting that results may change as the trial progresses).

Handsearching

We checked or handsearched the following sources:

citation lists of eligible studies (Horsley 2011);

citation lists of previous reviews of interventions for cognitive impairment following cancer;

papers which cited included studies;

publications by experts in the field.

We searched websites for relevant conference reports from the following sources (from 1980 to 2014):

International Cognition and Cancer Task Force (ICCTF);

International Neuropsychological Society;

British Journal of Cancer;

British Cancer Research Meeting;

Annual Meeting of European Society of Medical Oncology;

Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology;

Other relevant conference proceedings identified through Web of Science.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (CT) downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching to a reference manager software package and removed any duplicates. Pairs of review authors (CT and MD, CT and RON and CC and UM) examined the remaining references independently by title and abstract first, followed by full‐text articles. We excluded studies which clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria and obtained copies of the full text of potentially relevant references cited within these articles. The paired review authors (noted above) independently assessed the eligibility of retrieved articles. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two review authors or if necessary by an additional review author (MJC). We documented the reasons for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

We extracted the following data from included studies.

Authors, year of publication and journal citation (including language)

Country

Setting

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Study design, methodology

-

Study population:

total number randomised

age

sex/gender

co‐morbidities

cancer site

stage (the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics staging system)

grade

treatment history

education

socio‐economic status

cognitive status at baseline

-

Intervention details:

definition/details

intervention components (we created a taxonomy of intervention components by extracting data on the specific components involved in each intervention)

safety

adverse effects

-

Comparison:

definition/details

Risk of bias in study (seeAssessment of risk of bias in included studies)

Duration of follow‐up

-

Outcomes:

we extracted the definition and unit of measurement (if relevant) for each outcome

we extracted information about the measures and their properties including domains of cognition used to assess outcomes

we recorded variables and their adjustment in the analyses when calculating adjusted estimates

-

Results:

number of participants allocated to each intervention group and control group, the total number analysed for each outcome, and the proportion of participants in the intervention and control groups that were lost to follow‐up and their reasons

We planned to extract results as follows:

-

Continuous outcomes (e.g. cognitive functioning measures)

baseline value and final mean value and standard deviation of the outcome of interest and the number of patients assessed at end‐point in each group at end of follow‐up in order to estimate the mean between‐group difference and standard error.

-

Dichotomous outcomes (e.g. adverse events):

hazard ratio (HR) or, if a HR was unavailable the number of patients in each treatment group that experienced the outcome of interest and the number of patients assessed for that outcome in order to calculate a risk ratio (RR). However, no dichotomous outcomes were reported in any of the included studies.

We extracted reported unadjusted and adjusted statistics. Our data analysis was guided by an intention‐to‐treat approach in which participants were analysed according to the groups to which they had been randomly assigned. We noted the time points at which outcomes were collected and reported.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias in included studies using the Cochrane tool (Higgins 2011). We used RevMan to facilitate the presentation of our findings from the 'Risk of bias' assessment (Review Manager 2014). This assessment addressed selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias and other potential sources of bias including comparability of intervention and control group cognitive function scores at baseline, as well as the validity and reliability of cognitive function assessment measures.

We used the following items to assess risk of bias:

random sequence generation (selection bias);

allocation concealment (selection bias);

blinding of participants (performance bias);

blinding of personnel (performance bias);

blinding of assessment of outcomes (detection bias);

incomplete outcome data (attrition bias);

selective outcome reporting (reporting bias).

Three review authors worked in pairs (CT and RON or CT and UM) to apply the 'Risk of bias' tool independently. Any differences were resolved by discussion or with an additional review author (MD). We summarised results in a 'Risk of bias' graph. We had planned to examine funnel plots corresponding to meta‐analysis of cognitive functioning (the primary outcome) to assess the potential for small‐study effects such as publication bias if sufficient studies were included (e.g. more than 10), but too few studies were identified.

An overall risk of bias score was given to each study based on the following criteria.

Low: all criteria scored as low risk of bias

Moderate: one or two criteria unclear or high risk of bias

High: more than two criteria scored unclear or high risk of bias

Measures of treatment effect

The majority of outcome variables were continuous and the studies used a variety of tools to assess cognitive function. We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) to compare treatment groups when different scales were used. Neuropsychological tests do not provide a global score of cognitive function usually, so trials tended to include multiple cognitive function test scores. We planned to conduct meta‐analyses based on similar cognitive function domains measured across trials (e.g. executive functioning), if appropriate data were available from a sufficient number of trials of similar interventions, but few studies were identified. Therefore, we only undertook small meta‐analyses comparing compensatory strategy training interventions when comparable outcomes were reported (e.g. physical and mental well‐being). We planned to use the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to compare treatment groups for dichotomous outcomes such as adverse events, but, dichotomous outcomes were not reported in any of the studies.

Dealing with missing data

We did not impute missing outcome data for cognitive functioning (the primary outcome) or for any of the secondary outcomes, but imputed data had been reported in two studies (Ferguson 2012; Milbury 2013). We asked trial authors for data on outcomes for participants whose data were not reported.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We estimated heterogeneity using the I2 statistic within the meta‐analysis of two trials that we conducted.

Data synthesis

It was not possible to implement all the plans in our protocol because of an insufficient number of studies and the low methodological quality of the studies. We were not in a position to address each intervention type or category (e.g. cognitive rehabilitation, physical activity and relaxation/meditative) in separate meta‐analyses, pool results of studies in meta‐analyses using the Cochrane statistical software, (Review Manager 2014), or in trials with multiple treatment groups, divide the 'shared' comparison group into a number of treatment groups and treat comparisons between each treatment group and the split comparison group as independent comparisons. We used a random‐effects model with inverse variance weighting for the meta‐analyses (DerSimonian 1986). 'Summary of findings' tables were created in RevMan (Review Manager 2014) to summarise intervention effects and the quality of evidence using the Cochrane GRADE approach. The GRADE approach considers quality according to five factors: risk of bias, indirectness of evidence, inconsistency of evidence, imprecision of effect estimates and publication bias. The quality of evidence was downgraded from 'high' to 'moderate', 'low' or 'very low' quality according to limitations in each of the aforementioned factors.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not conduct the planned subgroup analyses for factors such as age, sex, cancer site, cancer stage, type of intervention, treatment history, cognitive status prior to study enrolment and duration of intervention because so few studies were identified.

Sensitivity analysis

Similarly, we did not perform sensitivity analyses (by, for example, re‐running analyses without studies deemed to have a high risk of bias) because of the small number of included studies.

Results

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of ongoing studies

Results of the search

Electronic search

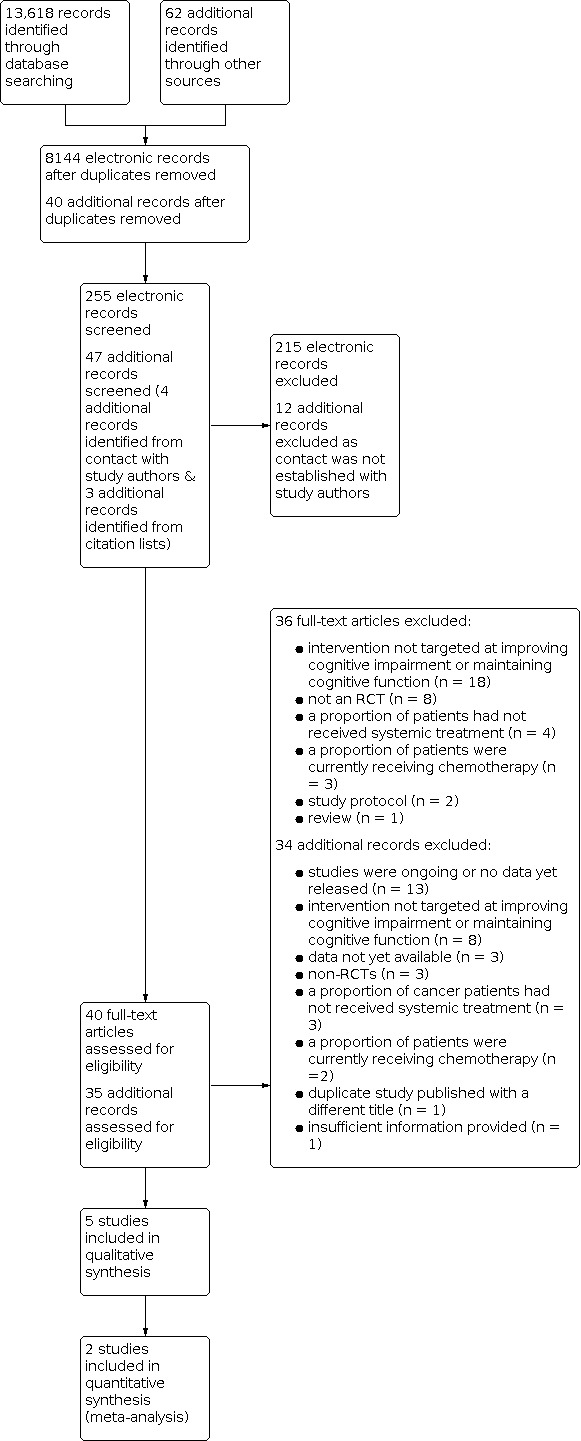

A total of 13,618 titles were identified from the electronic searches (Figure 1). Following removal of duplicate titles, 8144 titles remained. Screening of titles resulted in the exclusion of 7889 papers. The remaining 255 abstracts were examined for inclusion and 215 of these were excluded. Forty full‐text papers were obtained and fully screened for eligibility in the review. Four of these studies met our review's eligibility criteria.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Grey literature and unpublished sources

Sixty‐two potentially relevant studies were identified from unpublished and grey literature sources. One study was included, for which, a published conference poster was available.

Other sources

Three additional potentially relevant studies were identified from the citation lists of included papers but were excluded. No further studies were identified from papers which cited the included studies or related articles identified using PubMed.

Included studies

A total of five studies describing six interventions were included in the review. One study (Von Ah 2012) included two intervention groups and a shared wait‐list control group; participants had an equal chance of being randomised into one of the three groups. Three studies (Ferguson 2012; Kesler 2013; Von Ah 2012) tested four cognitive rehabilitation interventions including two cognitive training interventions (Kesler 2013; Von Ah 2012), and two compensatory strategy training interventions (Ferguson 2012; Von Ah 2012). A fourth study tested the feasibility of Tibetan Sound Meditation on improving cognitive and non‐cognitive outcomes. The fifth study (Campbell 2014) tested the effectiveness of aerobic exercise on improving cognitive outcomes.

In total, 235 participants were recruited in all five studies and randomised to an intervention group or to a wait‐list control group. The wait‐list control groups received standard care during the study and were offered the intervention at the end of the study period. All five studies recruited women who had survived breast cancer. The studies were conducted in two countries: four in the US (Ferguson 2012; Kesler 2013; Milbury 2013; Von Ah 2012) and, one in Canada (Campbell 2014). Four studies were published in peer‐reviewed scientific journals (Ferguson 2012; Kesler 2013; Milbury 2013; Von Ah 2012), and Campbell 2014 was presented at a conference. All studies were reported in English.

Ferguson 2012 tested an eight‐week cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)‐based Memory Attention Adaptation Training (MAAT) intervention which targeted improvement of memory and attention. The study enrolled women with stages I to IIIa breast cancer who had completed chemotherapy at least 18‐months previously and who self‐reported cognitive changes since treatment. The intervention was delivered face‐to‐face (with telephone contact between visits) by a clinical health psychologist. MAAT incorporated education, self‐awareness training, self‐regulation training (including relaxation) and cognitive compensatory strategy training. This study was underpowered and linear interpolation methods were used to account for missing data in order to undertake an intention‐to‐treat analysis. ANCOVA models were undertaken controlling for education and IQ to test for intervention effects on objective cognitive outcomes (verbal memory, speed of processing), self‐reported cognitive function and quality of life (QoL). Unexpectedly, the MAAT intervention targeting attention did not include an objective assessment of attention.

Von Ah 2012 examined the effects of a computerised cognitive training intervention named 'Insight' and a compensatory strategy training intervention named 'ACTIVE', which targeted memory compared to wait‐list controls. The interventions involved 10 one‐hour sessions delivered in a group setting by a trained interventionist over a six‐week period. This study did not specify the stage of cancer but required their participants to be disease‐free and treated for primary, non‐metastatic breast cancer and have completed chemotherapy at least one year previously. The Insight programme is commercially available, the version adapted for use in this trial targeted executive functions. The ACTIVE intervention included sessions on compensatory strategy training for memory and strategy practice to enhance self‐efficacy. The authors conducted general linear mixed models to assess differences between intervention and control groups using age, education, between‐group treatment effects, within‐group time effects and baseline values for each respective outcome as covariates.

Kesler 2013 reported the results of a 12‐week, home‐based, commercially‐available, computerised cognitive training intervention targeting executive functions among females with stages I to IIIa breast cancer. Participants were recruited irrespective of cognitive function status but had to have completed chemotherapy at least 18 months previously. Women allocated to the intervention received written instructions and weekly telephone/email contact for 48 sessions. Using ANCOVA models, a number of covariates including baseline cognitive flexibility scores, age, level of education, radiation, distress scores, hormonal therapy and time since chemotherapy were initially added to the models to assess the effects of the intervention on executive functions; however, the covariates were later removed as they did not significantly impact upon the relationship between cognitive training and executive functions. The primary outcome of interest in the study was cognitive flexibility measured by the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task and a Bonferroni correction was applied for all additional ANCOVA models to control for the effects of multiple testing. The authors also calculated corrected effect sizes to counteract potential practice effects of the neuropsychological test measures by subtracting the within‐group control group effect size from that of the intervention group.

Milbury 2013 assessed the feasibility and effectiveness of Tibetan Sound Meditation on cognitive function (self‐reported, visuomotor co‐ordination, processing speed, attention, working memory, verbal fluency and memory), and non‐cognitive outcomes (fatigue, depression, sleep disturbances, spiritual well‐being and health‐related quality of life) among women with stages I to IIIa breast cancer who were treated with chemotherapy up to five years previously. Each participant was eligible if they self‐reported cognitive impairment using a partial version of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐ Cognitive functioning sub scale (FACT‐Cog). Tibetan Sound Meditation is a meditative practice involving breathing techniques, visualisation, meditative sounds and cognitive tasks. The 6‐week intervention was delivered by a trained meditation instructor to between one and three participants who were provided also with a CD and written instructions to practice at home. Objective assessments of cognition were not undertaken immediately post‐intervention in order to counteract practice effects. Statistical analyses involved between‐group ANOVA models controlling for baseline values of each respective outcome. There were limitations to this study as a formal sample size calculation was not reported in the paper and the authors stated that the study was statistically under‐powered which may account for the absence of significant intervention effects (Milbury 2013). This intervention is currently being evaluated in a larger randomised controlled trial (RCT) including neuro‐imaging techniques as an additional objective measure of cognition (Cohen 2014).

In a Canadian proof of concept study, 19 women who had completed chemotherapy for early‐stage (I‐IIIa) breast cancer at least three months previously were allocated to 24 weeks of aerobic exercise (n = 10) or to a delayed exercise control group (n = 9) (Campbell 2014). To be eligible, participants had to self‐report changes in cognitive function which had persisted since treatment. Researchers undertook paired t‐tests and ANCOVA models controlling for baseline scores to observe changes in self‐reported cognitive function, objectively assessed memory, learning, verbal fluency, processing speed and executive functions over time. The 24‐week long intervention (including twice‐weekly contacts) involved supervised and independent aerobic exercise sessions but it is not clear if this was delivered face‐to‐face or in a group setting and the type of professional involved in the intervention was not described. The results of this study were reported in a conference poster and have not yet been published in a peer‐reviewed journal (as of August 2015). Correspondence was made with the author to obtain further information regarding, for example, randomisation.

Where necessary, study authors were contacted to provide data in a different format than was reported in the original papers. For example, Von Ah 2012 reported effect sizes (including 95% confidence intervals) for composite scores of their objective measures, but did not report the means and standard deviations on composite scores or individual measures at post‐intervention time points that were required in order to undertake a meta‐analysis. Non‐imputed values of outcomes were requested for one study (Ferguson 2012). At the time of writing of this review, requests for alternatively presented data were unfulfilled. Therefore, findings as reported in the original papers were included in this review.

Components and techniques of interventions

Two review authors (CT and MD) developed a taxonomy of similar and unique intervention components and techniques across the six interventions. A standardised pro forma was created, guided by the COMPASS criteria (Hodges 2011) for defining psychological interventions and the Behaviour Change Techniques (BCT) taxonomy (Michie 2013). Two techniques were common across all six interventions: instruction on how to perform the behaviour and demonstration (Campbell 2014; Ferguson 2012; Kesler 2013; Milbury 2013; Von Ah 2012). Behavioural practice/rehearsal was common to five interventions (Ferguson 2012; Kesler 2013; Milbury 2013; Von Ah 2012). Several techniques were common to three interventions: social support (unspecified) due to the group setting delivery of the intervention (Kesler 2013; Milbury 2013; Von Ah 2012), feedback on behaviour (Ferguson 2012; Kesler 2013; Von Ah 2012), generalisation of a target behaviour from a supervised setting to everyday settings (Campbell 2014; Ferguson 2012; Milbury 2013), and graded tasks of increasing difficulty (Campbell 2014; Kesler 2013; Von Ah 2012). Two interventions, CBT MAAT compensatory training (Ferguson 2012) and Tibetan Sound Meditation (Milbury 2013) included reducing negative emotions as a technique. Prompts/cues were used in two interventions (Ferguson 2012; Kesler 2013) via telephone contact from a member of the research team.

The remaining techniques were unique to intervention types. The physical activity intervention included the unique technique of goal setting as each individual was expected to reach the target exercise prescription by week eight of the intervention (Campbell 2014), whereas, framing/reframing was a technique unique to Tibetan Sound Meditation (Milbury 2013). Each compensatory strategy training intervention comprised the following techniques: instruction on how to perform‐ and, demonstration of‐ the behaviour via teaching the participants compensatory strategies and; behavioural practice/rehearsal of strategies was encouraged (Ferguson 2012; Von Ah 2012). Other techniques (some of which were unique) in the CBT‐based MAAT intervention include: feedback on behaviour via phone‐call to adapt or adjust techniques, self‐monitoring of behaviour whereby participants were encouraged to keep a daily planner, information about antecedents of behaviour and health consequences via education, prompts/cues, generalisation of target behaviour, reduction of negative emotions via relaxation, mental rehearsal of successful performance through visualisation and self‐talk using verbal rehearsal (Ferguson 2012). Both computerised cognitive training interventions contained common techniques: instruction on how to perform the behaviour, demonstration of how to perform the behaviour, behavioural practice/rehearsal, graded tasks, feedback on behaviour and feedback on outcomes of behaviour (Kesler 2013; Von Ah 2012). The interventions differed in their use of specific techniques: prompts/cues via weekly telephone calls were used in one study (Kesler 2013), whereas, social support (unspecified) due to the group setting of intervention delivery was used in the second study (Von Ah 2012).

Outcomes

The five studies used a range of different outcome measures. Three studies only provided participant assessments at one month (Milbury 2013) and two months (Ferguson 2012; Von Ah 2012) post‐intervention in addition to end‐of‐intervention assessments. The other two studies provided participant assessments only at the end of the intervention (Campbell 2014; Kesler 2013).

Cognitive outcomes

Although there was some overlap in the cognitive functioning domains objectively assessed across the studies, a variety of outcome measures were used. Some measures were used to measure more than one cognitive function.

Processing speed

The most commonly measured aspect of cognition was processing speed which was measured in all five studies using: the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) digit symbol‐coding subset (Ferguson 2012; Milbury 2013); the trail making letter‐number, colour‐word interference, colour‐word and switching trials of the Delis‐Kaplan Executive Function System (D‐KEFS) (Ferguson 2012); three subtests of the Useful Field of View were summed to calculate a composite processing speed score (Von Ah 2012); trials A and B and trial A‐B difference of the Trail Making Test (Campbell 2014) and; the WAIS version four symbol search subset (Kesler 2013).

Executive functions

Executive functions were assessed in two studies using the D‐KEFS letter fluency test (Kesler 2013) and the Trail Making Test (Campbell 2014). Other aspects of Executive function measured include: working memory, assessed, using the WAIS version four digit span subtest (Kesler 2013; Milbury 2013); attention using the WAIS digit symbol‐coding and digit span subsets (Milbury 2013) and; cognitive flexibility using the Wisconsin Card Sorting Task (WCST) (Kesler 2013). Verbal fluency was assessed in two studies using the Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) (Campbell 2014; Milbury 2013). Language was assessed in one study using the letter fluency subtest of the D‐KEFS (Kesler 2013).

Memory and learning

Memory and learning were measured in one study using the total recall, delayed recall, retention and delayed recognition index subtests of the HVLT (Campbell 2014). Visuomotor co‐ordination was assessed by one study using the WAIS digit symbol subset (Milbury 2013). One study created composite scores for memory outcomes, composite scores for immediate memory recall were calculated from the sum of recall trials 1‐5, short delay and recognition scores of the RAVLT and immediate recall of the Rivermead Behavioral paragraph Recall Test (RBPRT) (Von Ah 2012). Composite scores were also calculated for delayed memory recall from the long‐term delay scores of the RAVLT and RBPRT (Von Ah 2012). Alternate test forms of the CVLT (Ferguson 2012), D‐KEFS and HVLT (Kesler 2013) were used to counteract practice effects across two studies.

Verbal memory

Verbal memory was assessed in three studies using: summed raw score of trials 1‐5 of the California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) version two (Ferguson 2012); trials 1‐5, list B and recall of the Rey Adult Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT) (Milbury 2013) and; the Hopkin's Verbal Learning Test (HVLT) (Kesler 2013).

Self‐reported cognitive function

All five studies included outcome measures to allow participants to self‐report cognitive functioning. The most commonly used outcome measure was the FACT‐Cog which provides data on perceived cognitive concerns, perceived cognitive abilities, impact on QoL and comments from others (Campbell 2014; Milbury 2013; Von Ah 2012). In addition, three further outcome measures of subjective cognitive function were administered; two of which refer to specific domains of cognition. The additional measures include: Squire Subjective Memory Questionnaire (Von Ah 2012), the Behavioral Rating Inventory of Executive Functioning (Kesler 2013) and Multiple Abilities Subjective Questionnaire measuring five domains of cognition including language, visual perception, verbal‐, visual‐ memory and attention (Ferguson 2012).

Non‐cognitive outcomes

A number of additional outcomes were assessed including quality of life, depression, anxiety, fatigue and sleep disturbances. Quality of life was assessed as a secondary outcome in three studies: overall quality of life scores were provided using the Quality of life‐Cancer Survivor (QOL‐CS) and the Quality of life Index‐Cancer version (QLI‐C) scales (Von Ah 2012); domain scores for physical‐, psychological‐, social‐ and spiritual‐ quality of life were measured using the QOL‐CS (Ferguson 2012) and spiritual quality of life only using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐ Spiritual sub scale (FACT‐Spiritual) (Milbury 2013). Physical‐ and mental‐health status were assessed using the SF‐36 in two studies (Milbury 2013; Von Ah 2012).

The Center for Epidemiologial Studies‐ Depression scale (CES‐D) was used to assess depression in three studies (Ferguson 2012; Milbury 2013; Von Ah 2012). The Spielberger State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) was used to assess state anxiety in one study (Von Ah 2012) and state and trait anxiety in a further study (Ferguson 2012). Fatigue was assessed in two studies using the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐ Fatigue (FACT‐F) scale (Von Ah 2012) and Brief Fatigue Inventory (BFI) (Milbury 2013). The Clinical Assessment of Depression was used to assess psychological distress including depression, anxiety and cognitive fatigue in one study (Kesler 2013). Depression, anxiety and fatigue are related to cognitive function and were unlikely to improve or decline directly as a result of the cognitive‐ and compensatory‐strategy training interventions, therefore their assessment was undertaken in order to control for these factors in analysis in each of the three studies (Ferguson 2012; Kesler 2013; Von Ah 2012). One study only assessed sleep disturbances using the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (Milbury 2013). The study assessing the effectiveness of the Tibetan Sound Meditation intervention hypothesised also that improvements would be observed in quality of life, fatigue, mood and sleep outcomes for participants (Milbury 2013).

Treatment satisfaction

Three studies assessed satisfaction with the intervention: a study‐specific measure was used in one study (Ferguson 2012), the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire was used in a second study (Von Ah 2012) and a third study required participants to keep a brief evaluation of their satisfaction and acceptability of weekly sessions (Milbury 2013). Acceptability of the intervention was assessed in an additional study using a study‐specific questionnaire (Von Ah 2012).

Safety

Safety issues and adverse effects related to the intervention were captured in one study only (Kesler 2013). This study reported no safety issues or adverse events.

Excluded studies

Electronic database search

Thirty‐six studies were excluded following examination of the full text for reasons specified in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Grey literature and unpublished sources

Twenty‐two studies were excluded as they were duplicated registered titles or studies that were identified by the electronic database search. Contact was made with the Principal Investigator or named contact researcher when there were insufficient essential details in a paper. We contacted the researcher to obtain data or an update on study progress for 40 studies in the grey literature or unpublished sources. Two replies referred to four additional studies which had not been identified from other sources. Thereafter, 34 studies were excluded. Reasons for exclusion are specified in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Regarding the four additional studies that were forwarded to the review team by three of the contacted authors, three studies were excluded because the tested interventions were not targeted at maintaining cognitive function or improving cognitive impairment and the other study was excluded because patients who had not received systemic treatment were included and we were unable to separate these patients from those patients who had received systemic treatment.

Other sources

Three studies were excluded for the following reasons: the intervention was not targeted at improving cognitive impairment or maintaining cognitive functioning (n = 2) and one study was not an RCT.

Ongoing studies

Thirteen ongoing studies were identified from trial registries. Interventions included: computerised cognitive training (n = 4), compensatory strategy training (n = 3), physical activity (n = 2), cognitive training (n = 1) and meditation (n = 1). One trial combined computerised cognitive training and telephone compensatory strategy training. A further trial included three interventions encompassing (i) computerised cognitive training, compensatory strategy training and relaxation, (ii) active journal writing, compensatory strategy training and relaxation and (iii) computerised cognitive training only.

Risk of bias in included studies

All five studies were assessed for risk of bias using the 'Risk of bias' tool provided in RevMan 5.3 (Review Manager 2014). We assessed the following aspects of the studies: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of personnel/participants, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, baseline imbalance in cognition scores (both objectively assessed and subjectively reported) and reliability and validity of cognition outcome assessments (Figure 2). Overall, studies were categorised as having a high risk of bias.

2.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

The criteria for the review required studies to be randomised. Each of the four published studies described how participants were allocated to groups using computer‐generated lists (Ferguson 2012; Kesler 2013), stratified blocks (Campbell 2014; Von Ah 2012) and; minimisation (Milbury 2013). Contact with the author of the unpublished study confirmed that an appropriate random sequence generation method was used, namely block randomisation (Campbell 2014). All studies were scored as having a low risk of bias relating to random sequence allocation.

Allocation concealment

Four studies described clearly a method of allocation concealment that was judged to be of low risk of bias. They used computer‐based allocation methods (Ferguson 2012; Kesler 2013), serially numbered, opaque envelopes (Campbell 2014), or allocation was undertaken by personnel not involved in the study (Von Ah 2012). One study did not include sufficient detail to make a judgement, so we categorised this as having an 'unclear' risk of bias (Milbury 2013).

Blinding

Performance bias

Due to the nature of the non‐pharmacological interventions being delivered, it was not possible for study participants to be blinded to group allocation. Therefore, each study was scored as 'low risk' because it is unlikely that knowledge of group allocation by researcher or participant would influence outcomes (Campbell 2014; Ferguson 2012; Kesler 2013; Milbury 2013; Von Ah 2012).

Detection bias

Three studies included a clear statement that outcome assessors were blinded to the group allocation of participants and were therefore rated as having a 'low' risk of detection bias (Ferguson 2012; Kesler 2013; Von Ah 2012). Information provided on a registered trial database about the unpublished study indicated that outcome assessors were blind to group allocation of study participants (Campbell 2014). The final study was rated as having 'unclear' risk of bias because insufficient information about the outcome assessors was reported (Milbury 2013).

Incomplete outcome data

Two studies were rated as having a 'low' risk of attrition bias because all dropouts were accounted for in both the intervention and control groups and similar reasons for dropout were reported (Campbell 2014; Ferguson 2012). Furthermore, intention‐to‐treat analysis was undertaken for three studies (Campbell 2014; Ferguson 2012; Milbury 2013). Ferguson 2012 used linear interpolation methods to impute missing data and did not undertake sensitivity analysis. Two further studies were rated as 'high' risk of bias because they did not undertake intention‐to‐treat analysis (Kesler 2013; Von Ah 2012).The final study was rated as 'unclear' risk of bias as the reason for the dropout of one control group participant was not reported and they did not describe their method of intention‐to‐treat analysis (Milbury 2013).

Selective reporting

Three studies were rated as having an 'unclear' risk of bias due to the failure to report data related to: results of significance testing in their tables (Milbury 2013), potential confounding variables in tables (Ferguson 2012) and, means and standard deviations for individual test measures and composite scores at follow‐up time points (Von Ah 2012). The remaining two studies received a 'low' risk of bias score because all outcome measure data were reported in both study text and tables (Campbell 2014; Kesler 2013).

Other potential sources of bias

Other potential sources of bias in this review may result from baseline imbalances in objectively measured and subjectively reported cognitive function scores due to the possible failure of the randomisation strategy. Additionally, there is a poor correlation between objective and subjective assessments of cognitive function (Green 2005). Often, the cognitive function assessment measures that are used among cancer patients or survivors have been taken from other populations e.g. brain trauma, therefore, the use of potentially unreliable or invalid measures among the cancer population presents a potential risk of bias.

Four (Campbell 2014; Ferguson 2012; Kesler 2013; Milbury 2013) of the five studies were rated as having an 'unclear' risk of bias relating to baseline imbalances in objectively assessed cognitive function due to a failure to report the absence (or presence) of between‐group differences in objectively assessed cognitive function at baseline. Only one study (Von Ah 2012) reported that there were no between‐group baseline differences in objectively assessed cognitive function and therefore was rated as having 'low' risk of bias. Similarly for between‐group differences in subjectively reported cognitive function at baseline, only one study stated clearly whether or not any differences between‐groups were present (Ferguson 2012) and, therefore, was rated as having a 'low' risk of bias. The other studies were rated as having an 'unclear' risk of bias as no clear statement of baseline differences were reported (Campbell 2014; Kesler 2013; Milbury 2013; Von Ah 2012).

The studies reported infrequently on the reliability and validity of cognitive function assessment measures, therefore, the risk of bias was judged to be 'unclear' for the validity (Ferguson 2012; Milbury 2013; Von Ah 2012) and reliability (Ferguson 2012; Milbury 2013; Von Ah 2012) of objective outcome measures and, the validity (Campbell 2014; Ferguson 2012; Milbury 2013; Von Ah 2012) and reliability (Campbell 2014; Ferguson 2012; Kesler 2013; Milbury 2013; Von Ah 2012) of subjective outcome measures. For the validity and reliability of objective outcome measures, a rating of 'low' risk of bias was given to two studies because they reported on the psychometric information related to the measures (Kesler 2013) or chose their outcome measures based on the guidelines provided by the ICCTF (Campbell 2014). One study only provided psychometric information relating to their outcome measure to assess subjective cognitive function and thus it was rated as having a 'low' risk of bias (Kesler 2013).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

We were able to undertake meta‐analyses from two studies (n = 95 participants) comparing physical and mental well‐being immediately after, and 2 months after receipt of compensatory strategy training.

Computer‐assisted cognitive training

The two computer‐assisted cognitive training interventions (Kesler 2013; Von Ah 2012) recruited 100 participants in total. The studies reported on two overlapping outcomes only: processing speed and self‐reported cognitive function.

Objectively assessed cognitive outcomes

Kesler 2013 found a statistically significant improvement in processing speed compared to the control group immediately post‐intervention (between‐group effect size (d) = 0.87, P = 0.009). Similarly, Von Ah 2012 found significant improvements in processing speed compared to the control group immediately post‐intervention (d = 0.55, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.01 to 1.08, P value = 0.04) and two ‐months post‐intervention (d = 0.67, 95% CI = 0.14 to 1.21, P value = 0.016). This study also calculated reliable improvement scores; a participant demonstrated reliable improvement if their performance on a measure improved by at least one standard error of measurement. Compared to 43% and 61% of wait‐list controls, 68% and 67% of intervention participants demonstrated reliable improvement immediately and two months post‐intervention, respectively.

Significant intervention effects compared to wait‐list controls were found on a number of other objective assessments of cognitive function immediately post‐intervention including executive functions (d = 0.82, P value = 0.003), cognitive flexibility (d = 0.58, P = 0.008) and language (d = 0.82, P value = 0.003) (Kesler 2013). Despite working memory (a domain of executive functions) being targeted by the Kesler 2013 cognitive training intervention, no improvement was observed compared to the control group. This may be due to choice of outcome measure; the digit span test to measure working memory relies on auditory stimuli which may not be sufficient to capture the effects of the visually‐orientated intervention on working memory.

Kesler 2013 reported a trend towards a beneficial effect of the intervention compared to wait‐list controls on verbal memory immediately post‐intervention (d = 0.56, P value = 0.07). Although the intervention did not target specifically verbal memory, the authors reported that this observed trend may be due to the downstream effects of improvements in executive functions i.e. the cognitive domains targeted by the intervention. Transfer effects of the Insight intervention were observed on immediate memory recall immediately‐ (d = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.22 to 1.29, P value = 0.007) and two months post‐intervention (d = 0.82, 95% CI = 0.28 to 1.35, P value = 0.001), and on delayed memory recall two months post‐intervention (d = 0.72, 0.18 to 1.26, P value = 0.001) compared to controls. In terms of reliable improvement, for immediate memory recall immediately, and two months post‐intervention 41% and 30% of intervention participants demonstrated reliable improvement, compared to 10% and 18% of controls, respectively. Compared to 11% of controls, 33% of intervention participants demonstrated reliable improvement on delayed memory recall two months post‐intervention (Von Ah 2012).

Subjective cognitive function

A beneficial effect on self‐reported cognitive functioning was found for the intervention compared to the control group. An improvement was not observed on the global composite score of the BRIEF cognitive functioning measure, but improvements were observed on two BRIEF subscales including planning and/or organisation (d = 0.44, P value = 0.02) and task monitoring (d = 0.43, P value = 0.03). It is not clear why the authors calculated corrected effect sizes for the BRIEF subscales as it is unlikely that patient‐reported outcome measures are at risk of practice effects. This study did not assess intervention effects at additional time points so there is no information on the sustainability of intervention effects (Kesler 2013). Compared to wait‐list controls, significant improvements were found for self‐reported cognitive functioning on the FACT‐Cog (d = 0.55, 95% CI = 0.01 to 1.08) and SSMQ (d = 0.44, 95% CI =‐ 0.09 to 0.98) measures immediately post‐intervention, but this effect was not observed at two months post‐intervention.

Non‐cognitive outcomes

The Insight intervention also demonstrated beneficial effects on QoL. There was a beneficial effect of the Insight intervention on perceived mental health immediately‐ (d = 0.72, 0.19 to 1.26, P value = 0.01), and two months post‐intervention (d = 0.60, 0.07 to 1.13, P value = 0.03) compared to wait‐list controls. Nevertheless, overall quality of life was not improved as a result of the Insight intervention (Von Ah 2012).

Compensatory strategy training

The two compensatory strategy training interventions (Ferguson 2012; Von Ah 2012) recruited 99 participants in total. Data from 95 participants could be used in the meta‐analyses of physical and mental well‐being. The two studies measured two overlapping outcomes: processing speed and self‐reported cognitive functioning with findings in similar directions.

Objectively assessed cognitive outcomes

A beneficial effect of the ACTIVE intervention was found with improvements in immediate‐ (d = 0.59, 95% CI = 0.05 to 1.13, P value = 0.036) and delayed‐ (d = 0.70, 95% CI = 0.16 to 1.24, P value = 0.013) memory recall compared to controls at two months post‐intervention. This effect was not observed immediately post‐intervention which may reflect findings of similarly published literature. Thirty‐nine per cent and 42% of intervention participants demonstrated reliable improvement two months post‐intervention on immediate‐ and delayed‐memory recall compared to 18% and 11% of controls, respectively (Von Ah 2012). A significant group by time interaction (F (2, 76) = 53.16, P value < 0.05) with significant improvements in verbal memory compared to the wait‐list control group immediately post‐intervention (intervention d =‐0.36 versus control d = 0.14, P value < 0.001) and two‐months post‐intervention (intervention d = ‐0.81 versus control d = ‐0.18, P value < 0.001) were observed. Many of the MAAT intervention compensatory strategies involved verbalisation and vocalisations which may result in this observed effect. Relaxation techniques may also have contributed to improvements in verbal memory.

No improvements were observed on processing speed as a result of the ACTIVE (Von Ah 2012) or MAAT intervention (Ferguson 2012).

Subjective cognitive function

Compared to wait‐list controls, a beneficial effect of the ACTIVE intervention was found on subjectively reported cognitive function assessed by the FACT‐Cog (d = 0.59, P value = 0.036) and SSMQ ( d = 0.71, P value = 0.012) measures immediately post‐intervention and the FACT‐Cog (d = 0.65, P value = 0.021) and SSMQ (d = 0.84, P value = 0.003) measures two‐months post‐intervention (Von Ah 2012). There were no MAAT intervention effects for self‐reported cognitive functioning. The study authors report also that the FACT‐Cog (which was not yet developed at the time of the study) may be more effective to assess self‐reported cognitive function than the MASQ (Ferguson 2012).

Non‐cognitive outcomes

We considered the analysis of physical and mental health to be of low quality and that it should be interpreted with caution. See Table 1 for more information.

When we performed meta‐analyses of these two studies, there was no apparent effect of compensatory strategy training compared to wait‐list controls on physical well‐being immediately post‐intervention (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.12, 95% CI ‐0.59 to 0.83), although between‐study heterogeneity in this effect was moderate (I2 = 67%) (Analysis 1.1; Figure 3). Similarly, two‐months post‐intervention there was no apparent effect of compensatory strategy training compared to controls on physical well‐being (SMD ‐0.21, 95% CI ‐0.89 to 0.47; I2 = 63%) (Analysis 2.1; Figure 4). The effect of compensatory strategy training intervention on psychological well‐being post‐intervention favoured the wait‐list control group (SMD ‐0.57, 95% CI ‐0.98 to ‐0.16; I2 = 0%), with no observed between‐study heterogeneity (Analysis 1.2; Figure 5). The favourable effect of the compensatory strategy training intervention on psychological well‐being among the control group was no longer observed two months post‐intervention (SMD ‐0.38, 95% CI ‐1.10 to 0.34; I2 = 67%) (Analysis 2.2; Figure 6).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Compensatory strategy training versus wait‐list control immediately post‐intervention, Outcome 1: Physical well‐being

3.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Compensatory strategies, outcome: 1.1 Physical well‐being at post‐intervention.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Compensatory strategy training versus wait‐list control 2‐months post‐intervention, Outcome 1: Physical well‐being

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Compensatory strategies versus wait‐list control 2‐months post‐intervention, outcome: 2.1 Physical well‐being.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Compensatory strategy training versus wait‐list control immediately post‐intervention, Outcome 2: Psychological well‐being

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 Compensatory strategies versus wait‐list control immediately post‐intervention, outcome: 1.2 Psychological well‐being.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Compensatory strategy training versus wait‐list control 2‐months post‐intervention, Outcome 2: Psychological well‐being

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 2 Compensatory strategies versus wait‐list control 2‐months post‐intervention, outcome: 2.2 Psychological well‐being.

A significant time by group interaction (F(2,76) = 3.44, P value < 0.05) was observed for the MAAT intervention on spiritual quality of life compared to wait‐list controls immediately post‐intervention (intervention d =‐0.35 versus control d = 0.14) and two months post‐intervention (intervention d = ‐0.11 versus control d = 0.15) in a repeated measures ANCOVA model controlling for education and IQ. The authors report that this observed improvement may reflect participants' perceived optimism, hopefulness and purpose in life represented by the spiritual QoL items (Ferguson 2012).

Meditation/relaxation intervention