Abstract

Congenital birth defects result from an abnormal development of an embryo and have detrimental effects on children’s health. Specifically, congenital heart malformations are a leading cause of death among pediatric patients and often require surgical interventions within the first year of life. Increased efforts to navigate the human genome provide an opportunity to discover multiple candidate genes in patients suffering from birth defects. These efforts, however, fail to provide an explanation regarding the mechanisms of disease pathogenesis and emphasize the need for an efficient platform to screen candidate genes. Xenopus is a rapid, cost effective, high-throughput vertebrate organism to model the mechanisms behind human disease. This review provides numerous examples describing the successful use of Xenopus to investigate the contribution of patient mutations to complex phenotypes including congenital heart disease and heterotaxy. Moreover, we describe a variety of unique methods that allow us to rapidly recapitulate patients’ phenotypes in frogs: gene knockout and knockdown strategies, the use of fate maps for targeted manipulations, and novel imaging modalities. The combination of patient genomics data and the functional studies in Xenopus will provide necessary answers to the patients suffering from birth defects. Furthermore, it will allow for the development of better diagnostic methods to ensure early detection and intervention. Finally, with better understanding of disease pathogenesis, new treatment methods can be tailored specifically to address patient’s phenotype and genotype.

1. Congenital malformations

Congenital malformations, or birth defects, occur as a result of an improper development of an embryo. These birth defects have a massive impact on pediatric health. Additionally, some congenital birth defects disrupt pregnancies leading to stillbirths and miscarriages, which is particularly devastating to parents who plan to start a family (Gregory, MacDorman, & Martin, 2014; Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network Writing Group, 2011). Every year around 8 million children are born with severe birth defects worldwide, which constitutes roughly 6% of births (Christianson, Howson, & Modell, 2006). In the United States, during the first year of life, congenital malformations are the leading cause of medical expenditure (Waitzman, Romano, & Scheffler, 1994), pediatric hospitalizations (Yoon et al., 1997), and death (Murphy, Mathews, Martin, Minkovitz, & Strobino, 2017). Moreover, birth defects remain a leading cause of death among children in different age categories. In particular, it is the number two cause of death in children between 1 and 4 years old, number three in pediatric patients from 5 to 14 years of age, and number 6 in patients from 15 to 24 years old (United States Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). Therefore, considering the tremendous impact of birth defects on pediatric patients and their families, there is an urgent need to improve both diagnostic approaches and treatment methods. Such improvements could be achieved through the combination of genetic testing and the understanding of the molecular mechanisms contributing to congenital malformations. Currently, the advancements in human genomics allow for the use of massively parallel sequencing platforms to identify candidate genes in patients with birth defects. These methods, however, fail to reveal the mechanisms behind disease pathogenesis. Hence, despite our best efforts to navigate the human genome, we still lack the ability to efficiently translate genomic data into diagnostic applications and treatments tailored specifically to patients’ genotypes. Therefore, there is an increasing need to develop platforms for testing candidate genes to determine their roles in proper embryo development and how mutations in those genes could lead to birth defects. This review describes the advantages of using Xenopus as a model organism to study congenital malformations and connect genomics knowledge with patient phenotypes and embryological mechanisms.

2. Congenital heart disease

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common and the most life-threatening birth defect. Every year CHD affects ~1% of live births and 1.3 million patients worldwide (van der Linde et al., 2011). Because much of CHD is associated with high rates of both mortality and morbidity, these heart malformations will normally need to be corrected with the use of surgery or other interventions (Xu, Murphy, Kochanek, Bastian, & Arias, 2018). Advancements in medical and surgical management allow more CHD patients to reach adulthood. Specifically, the number of adult CHD survivors is expected to rise by 5% every year (van der Bom et al., 2011; Warnes et al., 2001). This increase in survival also presents a new challenge for developing novel medical and surgical strategies to care for adult CHD patients. In particular, these adult patients have high potential to eventually develop multiple CHD associated complications, including arrhythmias, hemodynamic instability, pregnancy loss and infertility, pulmonary disease and neurodevelopmental disorders (Marino et al., 2012; Mussatto et al., 2015). Additionally, CHD patients encounter high medical care costs, which in the United States exceed 1.75 billion dollars annually (Russo & Elixhauser, 2007). Although access to health care remains one of the most important factors in the diagnosis and management of CHD, both genetic and environmental factors definitely contribute to this process as well (van der Linde et al., 2011).

Given the growing impact of CHD, it is crucial to develop platforms to test candidate genes identified through genomic sequencing. Such platforms will allow physicians to provide patients with better answers about their disease mechanisms. Further, it will improve diagnostic testing and encourage the use of individualized treatment approaches that could be specifically tailored to patient’s genotype rather than just phenotype. Xenopus is an excellent model organism to test the function of CHD candidate genes in order to investigate their role in vertebrate development and disease pathogenesis.

3. Heterotaxy can lead to a severe form of CHD

Heterotaxy (Htx) is the abnormal position of the internal organs along the left-right axis. This can have a severe effect on the function of the heart as the right and left sides of the heart have very different functions. The right heart chambers together with associated blood vessels enable the oxygenation of blood in the lungs, while the left side of the heart delivers oxygenated blood to organs and tissues. Other organs also have a left-right asymmetry including the stomach, rotation of the gut, spleen, lungs, and even the brain. Any developmental disruptions of left-right body axis patterning could lead to abnormal positioning of internal organs and their subsequent malfunction. The arrangement of internal organs along left-right body axis can be divided into three categories: Situs solitus, which is characterized by normal positioning of body organs; situs inversus, which is a completely reversed, mirror image of the normal orientation; and situs ambiguous, in which there is no defined orientation of body organs with respect to left-right body axis.

Given the left-right asymmetry of the heart, heterotaxy can lead to a severe form of CHD. It occurs in 1 in 10,000 of children with CHD and it encompasses 3% of all CHD cases (Brueckner, 2007; Zhu, Belmont, & Ware, 2006). Heterotaxy in the situs ambiguous category is one of the most severe forms of CHD (Harden et al., 2014). Hence, patients with heterotaxy often need to undergo surgery or interventional procedures but despite advancements in care, heterotaxy has a relatively poor prognosis. For example, heterotaxy patients may suffer from multiple post-operative complications including arrhythmias and respiratory issues (Amula, Ellsworth, Bratton, Arrington, & Witte, 2014; Harden et al., 2014).

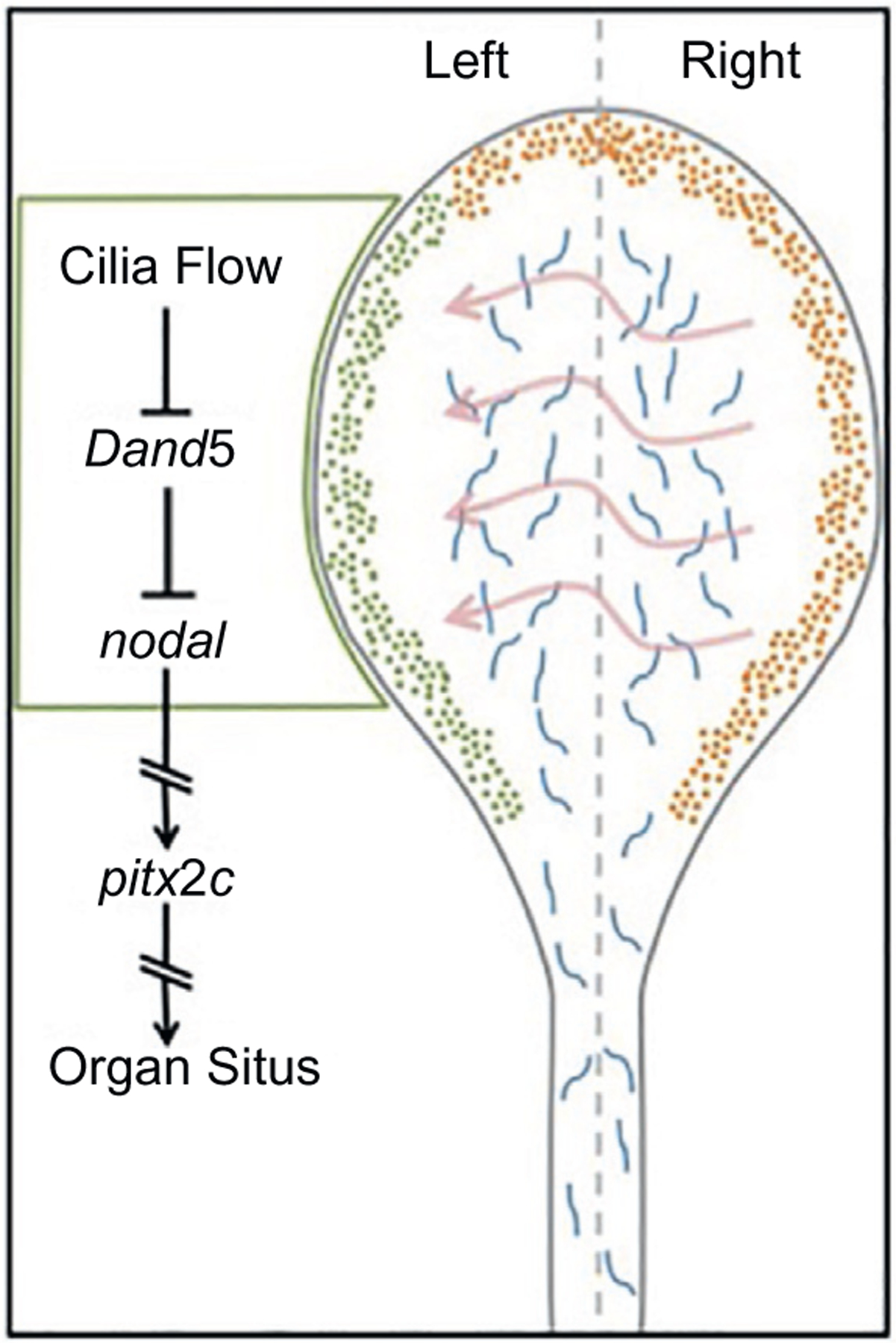

Like other congenital malformations, heterotaxy is a result of abnormal left-right embryo patterning. Left-Right embryo patterning follows a precise program that is conserved in multiple organisms. During gastrulation, the embryo establishes dorsoventral and anteroposterior body axes after the morphogenesis of the three germ layers: endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm. Near the end of gastrulation, the superficial dorsal mesoderm gives rise to the Left-Right Organizer (LRO) tissue, which will eventually break the bilateral symmetry of the embryo with respect to its left-right body axis. The LRO is a conserved tissue found in multiple organisms: it is the node in the mouse, the Kupffer’s vesicle in zebrafish, and the gastrocoel roof plate (GRP) in the frog. Left-right asymmetry is established by the leftward extracellular fluid flow generated by motile cilia in the central portion of the LRO (Fig. 1) (Nonaka, Shiratori, Saijoh, & Hamada, 2002; Okada, Takeda, Tanaka, Belmonte, & Hirokawa, 2005). This flow is detected by the peripherally located immotile cilia and translated into asymmetric gene expression (McGrath, Somlo, Makova, Tian, & Brueckner, 2003; Tabin & Vogan, 2003). Specifically, this leftward flow leads to the inhibition of dand5, an antagonist of nodal (Schweickert et al., 2010; Vonica & Brivanlou, 2007). The absence of dand5 expression leads to the activation of nodal signaling, the phosphorylation of Smad2, and the subsequent activation of pitx2 in the left lateral plate mesoderm (Kawasumi et al., 2011; Lee & Anderson, 2008). Pitx2 expression is crucial for the asymmetric formation of heart, gut and lungs (Davis et al., 2008; Kurpios et al., 2008). The heart first forms from the fusion of precursor cardiac cells from lateral plate mesoderm to form a straight cardiac tube in the midline (Abu-Issa & Kirby, 2008; Stalsberg & DeHaan, 1969). The central region of the tube will give rise to the left ventricle. One end of the cardiac tube will form the outflow tracts and the atria, while the other end will form the inflow tracts and the right ventricle. Most importantly, the rightward rotation of this cardiac tube will eventually establish the left-right asymmetry of the adult heart. Multiple signaling programs contribute to proper establishment of this asymmetry (Hamada & Tam, 2014). These include cilia driven flow in the Left-Right Organizer, that leads to the suppression of dand5, a nodal antagonist, with the subsequent activation of the nodal pathway on the left side of the embryo. Additionally, BMP signaling is thought to specify the right side of the embryo. These an additional pathways integrate to specify the LR axis and subsequent cardiac looping.

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the LR signaling cascade in the LRO.

4. Patient-driven gene discovery

4.1. Heterotaxy and rare copy-number variations

As genomic analysis has become more affordable, numerous efforts have been made to identify the genes associated with heterotaxy. In one study, the investigators identified rare copy-number variations (CNV) (Fakhro et al., 2011) in patients with heterotaxy. Using high-resolution SNP arrays in 262 heterotaxy patients and 991 control individuals, a total of 45 copy-number variations were found in patients with heterotaxy. In particular, 7 of 45 identified CNVs were large chromosomal deletions (6–25Mb), while the other 38 were small in size (27–1488kb). Examining the expression of some of these genes in Xenopus revealed that many were expressed in the left-right Organizer. Seven of these genes were selected for knockdown studies, and remarkably, the knockdown of five genes (NEK2, ROCK2, TGFBR2, GALNT11, and NUP188) using an antisense oligonucleotide morpholino caused significant abnormalities in the left-right patterning cascade (detected by in situ hybridization for pitx2c) with subsequent abnormal heart looping (Fakhro et al., 2011). More importantly, the tested genes are involved in diverse independent cellular processes, most of which have not had a previously established connection to cardiac development. For example, subsequent studies of the identified genes revealed a unique subcellular location of NUP188 and its binding partner NUP93 at the base of cilia (rather than the nuclear pore complex) and that their morpholino-mediated knockdown leads to the loss of cilia (Del Viso et al., 2016). Additionally, GALNT11 was found to regulate Notch signaling and establish the balance between motile and immotile cilia within the LRO tissue (Boskovski et al., 2013). As a third example, RAPGEF5 was recently found to regulate beta-catenin nuclear localization in the Wnt signaling pathway (Griffin et al., 2018). Therefore, pursuing a mechanism behind an identified candidate gene presents an outstanding opportunity to discover its novel function in cardiac development.

Another connection between copy-number variants and heterotaxy was made through the population based analysis conducted in New York State between 1998 and 2005 (Rigler et al., 2015). This study examined the DNA from dried blood spots from 77 newborns with classic heterotaxy. This investigation revealed 20 rare copy-number variants in genes contributing to various developmental pathways. Particularly, CNVs were identified in several members of the transforming growth factor-β superfamily, including bone morphogenic protein 2 (BMP2), fibroblast growth factor 12 (FGF12), and growth differentiation factor 7 (GDF7). Furthermore, two heterozygous deletions were identified in the gene encoding myeloid cell nuclear differentiation antigen (MNDA). Additionally, similar 20kb duplications in the oligosaccharyltransferase complex subunit (OSTC) gene were identified in three separate cases. Despite the fact that multiple genes continue to be discovered, we still have a limited knowledge about the mechanisms behind candidate gene action and their role in CHD pathogenesis.

Another study examined 69 patients with classic heterotaxy identified from 1998 to 2009 in California (Hagen et al., 2016). 56 rare CNVs were identified including genes in crucial developmental pathways such as Nodal, BMP, and WNT. More importantly, none of these genes have been previously described within a context of heterotaxy pathogenesis. Moreover, CNVs in RBFOX1 and near MIR302F were found in multiple patients encouraging further investigation of their roles in heterotaxy and left-right embryo patterning. This study provides another example of how genomic methods could be used to identify candidate without known function in cardiac development, and emphasizes the importance of understanding the mechanism of disease to better serve this patient population.

4.2. De novo variants in CHD patients

In addition to CNVs, rare de novo variants have been identified in patients with congenital heart disease. CHD is generally a sporadic illness with healthy parents that have a child with CHD. Therefore, a de novo model of disease pathogenesis seems plausible. Using exome sequencing, 2871 probands were examined, including 2645 parent-offspring trios (Jin et al., 2017). De novo mutations were found in 443 genes and are thought to contribute to 8% of all cases of CHD. The candidate genes found in this study are involved in a variety of cellular processes. Interestingly, chromatin modifiers constitute a major class of novel genes in CHD patients. In particular, loss of function de novo mutations of chromatin modifiers were identified in 2.3% of probands. Additionally, this study also emphasized the link between CHD and neurodevelopmental disorders (NDD). 3% of patients had isolated CHD phenotype, while 28% of CHD patients had both neurodevelopmental and extra-cardiac manifestations. Specifically, patients with loss of function mutations in chromatin modifiers demonstrated an 87% higher risk of developing NDD. Interestingly, autism studies also identified de novo mutations in chromatin modifiers with a surprising overlap between autism and CDD. Furthermore, from a clinical perspective, many patients with CHD also suffer from NDD. NDD had been thought to be a complication of brain hypoxia operatively or peri-operatively for CHD, but these studies strongly suggested that NDD in CHD patients may be due to genes that affect both cardiac and brain development. Hence, detecting specific mutations associated with both CHD and NDD will allow for early interventions that could significantly improve outcomes in patients with neurodevelopmental abnormalities.

5. The challenges of patient-driven gene discovery efforts

The advancement of research methods to interrogate the human genome in CHD patients can improve our understanding of CHD and heterotaxy mechanisms. However, there are multiple challenges in defining precise disease causality using genomic data only. While the use of advanced sequencing methods enables the identification of the genes associated with heterotaxy, the establishment of their disease causality presents a challenge. Specifically, proof of disease causality requires that multiple detrimental alleles be identified in CHD patients compared to controls. However, due to high locus heterogeneity, multiple alleles are difficult in small to medium sized cohorts of CHD patients. From an embryological perspective, high locus heterogeneity is not surprising as multiple genes contribute to such complex processes as cardiac development and left-right patterning. In the future, the identification of multiple alleles will become possible with additional reductions in sequencing costs.

The next challenge is to unveil the molecular mechanisms behind the identified candidate genes and how their disruption contributes to congenital heart disease and embryo patterning pathogenesis. In order to accomplish this aim, we need an efficient high-throughput model to screen candidate genes identified by genome sequencing. While we await multiple allele identification to confirm disease causality, if we had an efficient screening platform, we could still use patient based gene discovery to identify genes that affect heart development. Xenopus offers a highly efficient model organism that could provide multiple benefits for patients with congenital heart disease. First, most patients and families yearn for some meaning in the patients’ illness. For some, gene sequencing can identify a known cause of CHD and this provides a critical answer and the potential for genetic counseling in the future. But for many, no defined genetic cause is identified, but instead, variants of unknown significance. By testing these in Xenopus, we can establish that at least in this animal model the candidate gene does indeed affect heart development, a lunching platform for mechanistic studies. Many patients/families are very grateful for such discoveries as this provides some meaning (by creating a scientific research avenue) to their child’s illness. In the future, understanding molecular mechanism could provide more accurate information about disease prognosis and will advance patient care. Additionally, most genetic conditions are often described in terms of patient symptoms and phenotypes. Such evaluation fails to acknowledge the differences in patients’ genotypes as this information is often unavailable. Therefore, known treatment approaches are mostly targeted toward patients’ phenotypes and are not ideal. A better understanding of patients’ genotypes will also provide a more tailored treatment method and will improve disease outcomes.

To make this a reality, we need to address two challenges: assigning the disease causality to a specific gene, and determining mechanism of the disease. As discussed previously, the proof of disease causality presents a challenge due to high locus heterogeneity. Furthermore, a large number of identified genes may not have a known function in cardiac development or left-right patterning. In addition, some of the identified genes do not have a function previously described at all. Therefore, in the absence of massive population sequencing data, the ascertainment of molecular mechanisms should not wait until multiple alleles are identified since Xenopus is a perfect model organism to recapitulate human disease phenotypes and advance our understanding of plausible disease mechanisms. This screening platform has the potential to reveal the molecular mechanisms of human disease and explain complicated patient phenotypes. Therefore, Xenopus is a perfect animal model to test the function of candidate genes in congenital organ malformations, including cardiac abnormalities and left-right patterning defects such as heterotaxy.

6. Xenopus tools to study congenital disease

Xenopus is a fantastic model organism to study human disease. It enables a rapid, efficient and cost-effective screening approach of candidate genes to determine their role in left-right patterning and cardiac development (Blum et al., 2009; Wallingford, Liu, & Zheng, 2010; Warkman & Krieg, 2007). Two species of Xenopus are widely used in developmental research. Each species offers specific advantages. Xenopus laevis produces large allotetraploid embryos that are excellent for gene overexpression analysis and biochemical studies because the embryos can be cooled to allow time to inject mRNAs at the early cleavage stages. Additionally, they produce a large number of eggs via in vitro fertilization so abundant that biochemical experiments are greatly facilitated. Xenopus tropicalis, on the other hand, is a diploid organism that is a perfect match by facilitating loss of function studies. In addition, both Xenopus species develop externally, which allows for analysis and easy manipulation of an embryo. Furthermore, Xenopus early tadpoles are transparent, which provides an easy way to examine the gross morphology of internal organs under a light microscope. More significantly, Xenopus organogenesis is a rapid process. For example, the embryonic heart can be visualized as early as 3 days after fertilization. In addition, abnormal cardiac looping can be detected simply through the examination of the outflow tract of stage 45 embryos under light microscope. More importantly, the early development of the Xenopus heart does not depend on blood circulation as oxygen delivery takes place through simple diffusion. This allows for a greater variety of genomic manipulations that may not be possible in mice due to potential embryonic lethality. In addition, the Xenopus genome has significant conservation with human. The genome of Xenopus tropicalis contains orthologues for approximately 79% of genes identified in human disease (Grant et al., 2015; Hellsten et al., 2010; Khokha, 2012). Moreover, the frog genome has a high degree of synteny with the human genome, containing long equivalent regions with genes positioned in a conserved order (Blitz, 2012; Blitz, Biesinger, Xie, & Cho, 2013). Synteny is particularly useful for distinguishing orthologues from paralogs. Additionally, the anatomic structure and the development of Xenopus heart are characterized by a higher degree of conservation with human than other aquatic animals (Showell & Conlon, 2007). In comparison to a four-chambered human heart, a zebrafish heart has two chambers only: an atrium and a ventricle. Xenopus, on the other hand, has a three-chamber heart including a ventricle, and left and right atria separated by a septum (Mohun, Leong, Weninger, & Sparrow, 2000). Also, similar to human, a Xenopus heart contains trabeculae within the ventricular myocardium. More importantly, the background rate of cardiac malformation is very low, which allows for a robust identification of genes that could be disruptive for heart formation. Finally, the maintenance of Xenopus species is inexpensive compared to mammalian models.

6.1. Manipulations of gene expression in Xenopus

Gene expression in Xenopus embryos can be easily manipulated using micro-injections of mRNA and antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (MO) for gain or loss of function, respectively. MOs are designed to target either the start site or the splice site of the mRNA transcript. They have been traditionally used for gene knockdown strategies due to their ability to target both maternal and zygotic transcripts. As an alternative, CRISPR-Cas9 mediated gene knockout works well even in the F0 generation (Bhattacharya, Marfo, Li, Lane, & Khokha, 2015). This strategy works best with the co-injection of Cas9 protein with the target sgRNA. The injection of Cas9 protein, rather than Cas9 mRNA, has been shown to have a higher cutting efficiency and a lower toxicity. Targeted DNA editing can be easily evaluated via PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing followed by subsequent mismatch analysis using a free online Interference of CRISPR Edits (ICE) tool (Hsiau et al., 2018). Importantly, successful CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genome editing of both alleles can be detected as early as 2h post injections in F0 embryos (Bhattacharya et al., 2015). Furthermore, CRISPR embryos can be raised to generate stable frog lines carrying specific mutations or indels. Therefore, CRISPR-Cas9 is an effective genome editing tool to use in Xenopus to knockout genes from the zygotic genome.

Another major advantage of using Xenopus to study organ development is the ability to efficiently generate transgenic animals (Amaya & Kroll, 2010; Hirsch et al., 2002). Successful incorporation of exogenous DNA into the genome of a one-cell embryo prior to cell division has been reported in both Xenopus tropicalis and Xenopus laevis (Marsh-Armstrong, Huang, Berry, & Brown, 1999; Offield, Hirsch, & Grainger, 2000). Moreover, a precise, targeted genomic integration using homology-directed repair (HDR) has been shown in Xenopus (Aslan, Tadjuidje, Zorn, & Cha, 2017). When coupled to a fluorescent reporter, the expression of a transgene can be monitored in a living, developing embryo over time. Moreover, tissue explants from transgenic animals can be transplanted into ectopic sites of a wild-type animal and examined via detection of a fluorescent signal combining the power of cut and paste embryology with transgenic reporter lines. Additionally, the use of different fluorescent reporters allows for detection of the interaction between multiple transgenes in the same animal. Furthermore, an inducible transgene activation has been shown to provide a controlled spatio-temporal expression (Chae, Zimmerman, & Grainger, 2002; Rankin, Zorn, & Buchholz, 2011). Together these properties make Xenopus an effective model organism to study multiple developmental processes including kidney development (Corkins et al., 2018), lymphangiogenesis (Ny et al., 2013), signaling pathways (Tran, Sekkali, Van Imschoot, Janssens, & Vleminckx, 2010), apoptosis (Kominami et al., 2006), and epigenetic changes (Suzuki et al., 2016). More specifically, transgenic Xenopus animals have been used in the studies of heart chamber formation to visualize muscle fiber development (Smith et al., 2005). In this study, the expression of green fluorescent protein (GFP) was placed under control of the cardiac-specific MLC1v gene promoter, to examine the muscle formation of both the ventricle and the atria throughout tadpole development. The fluorescent signal was first detected during the heart tube looping stage, which establishes the separation between the ventricle and the outflow tract. Later, the MLC1v transgene became apparent on the atrial side of the atrioventricular boundary. Moreover, the transgenic GFP expression also showed a distinct arrangement of muscle fibers in the chamber versus the outflow tract myocardium. Therefore, this is yet another example how the use of transgenic animals can aid in studies of the tissue- and stage-specific expression of target genes.

6.2. Targeted injections in Xenopus

In addition to successful, cost-effective knockout and knockdown methods, Xenopus has advantages for the analysis of left-right patterning that is not shared by any other organism. For example, injection of one cell of the two-cell embryo can target either the left or right side of the embryo. Using fluorescent tracers, one can easily detected the injected side of the embryo and compare it to the un-injected side. Such manipulations are highly useful as they provide an internal control in the same animal for each experiment. In addition to two-cell stage injection, Xenopus embryos have a well-defined cell fate map for each organ system (Moody, 1987). This allows for targeted injections, where the expression of genes can be modified in specific organs or tissues. Additional studies of cardiac marker gene expression analysis as well as fate mapping data of cardiac progenitor cells at different stages of development are now available and could be used to better understand cardiac development (Gessert & Kühl, 2009). This study also describes an early segregation of cardiac lineages and could be used to understand the molecular mechanisms behind cardiogenesis. Therefore, Xenopus embryos offer straightforward manipulations to precisely track specific phenotypes.

6.3. Imaging modalities: Optical coherence tomography

Novel imaging modalities, such as optical coherence tomography (OCT), can be used to evaluate heart and craniofacial malformations in Xenopus embryos (Deniz et al., 2017). Similar to ultrasound, OCT uses light waves to obtain in vivo cross-sectional images of internal structures at micrometer resolution (Huang et al., 1991). OCT can visualize the atria, trabeculated ventricle, the outflow tract, and the atrioventricular valve and provide quantitative data. Moreover, this technology is non-destructive so live tadpole can be imaged repetitively over time so disease progression can be tracked over time in the same animal. Furthermore, subsequent imaging presents an opportunity to distinguish between the primary and secondary effects of a specific phenotype. Due to all these advantages, OCT is an effective tool to model human disease states in Xenopus. Recently, this imaging modality was used to recapitulate a known cause of cardiomyopathy. Mutation in myosin heavy chain 6 (myh6) disrupts the structure of a sarcomere, which is a functional unit of cardiac muscle. A MO-mediated knockdown of myh6 in Xenopus resulted in higher end systolic diameters, a sign of systolic dysfunction from reduced contractility. Moreover, the presence of dilated atria combined with the lower excursion distance of the atrioventricular valve suggested that the reduced expression of myh6 leads to a non-compliant ventricle with poor contractility. Additionally, the outflow tract in the depleted tadpole was much narrower and had lower excursion distance compared to control tadpoles, again reflecting a reduction in cardiac output. Thus, OCT can be effectively used in Xenopus to model human heart disease.

6.4. Tissue explant assays

The use of tissue explant experiments in Xenopus makes it an effective model to study cardiac development and congenital heart malformations. Tissue explant technique dates back to the famous experiments by Spemann and Mangold, who showed that the transplantation of the blastopore lip to an ectopic site can induce the formation of the secondary axis from the ectodermal tissue that was supposed to become epidermis (Spemann & Mangold, 1923). Subsequent work by Nieuwkoop showed that ectodermal tissue can be induced by endoderm to transform into mesoderm (Nieuwkoop, 1969). This work demonstrated the importance of signaling patterns in the establishment of the three germ layers and their derivatives in the developing embryos. The heart is a derivative of the mesodermal layer and multiple signaling pathways contribute to proper cardiac development. These signaling pathways could be directly or indirectly involved in the development of other organs as well. Additionally, development is a cascade of serial steps so signaling events at one time point could have primary as well as secondary effects on cardiac structure. Therefore, there is a need to isolate progenitor cardiac tissue at a specific time points while minimizing the effects from other signaling factors and surrounding tissues. Explant experiments provide such a framework and can be successfully used to define the mechanism of cardiac differentiation as a mesodermal derivative. Specifically, Xenopus laevis eggs are often used in these experiments due to their larger size as compared to Xenopus tropicalis. These embryos can also efficiently regenerate after a microsurgery. Importantly, because early cleavage stages are holoblastic (as opposed to meroblastic cleavages in chick or zebrafish embryos), yolk is distributed to all cells so explants do not require any supplemental nutrition as it can survive using the nutrients stored intracellularly. Dissected tissue develops and differentiates in a simple salt solution.

Heart development begins in the mesodermal region called the dorsal marginal zone (DMZ), while the ventral marginal zone (VMZ) does not contribute to the cardiac development. Cardiogenesis in Xenopus starts at the onset of gastrulation with the formation of precardiac mesoderm on both sides of the Spemann organizer. During gastrulation, the progenitor cells from those regions will migrate anteriorly to the ventral midline where they will undergo fusion. Later this fused crescent-like structure will split into two distinct lineages forming the first heart field and the second heart field. The first heart field contributes to the formation of a ventricle and two atria, while the second heart field will form the outflow tract.

Both DMZ and VMZ explants can be utilized to study heart morphogenesis. DMZ explants allow investigators to examine the endogenous signals and processes present in the cardiogenic dorsoanterior mesoderm that are necessary for heart formation. On the contrary, VMZ explants provide noncardiogenic tissue that could be subjected to signals capable of inducing the heart in an ectopic environment. Molecular manipulations can be easily targeted to these tissues at the four-cell stage of development by targeting the dorsal blastomeres. Additionally, during later stages of development (stages 10–10.5), the appearance of the dorsal blastopore lip marks the DMZ, from which the heart derives. Once isolated and cultured, both DMZ and VMZ can be evaluated for specific gene expression changes using a variety of methods including in situ hybridization, Western blotting, and differentiation into beating cardiomyocyte tissue. For instance, explant tissue experiments were used to show that Wnt antagonism initiated heart development (Schneider & Mercola, 2001). Using Xenopus laevis embryos at four-cell stage, the mRNAs of Wnt and BMP antagonists were injected into both ventral blastomeres. VMZ explants were removed at stage 10, kept in culture and analyzed at stage 30 using RT-PCR for the expression of cardiac-specific genes. The ectopic expression of dkk-1, an antagonist of Wnt signaling, in the VMZ led to the expression of cardiac-specific genes including Nkx2.5 and Tbx5 as well as cardiomyocyte contractile proteins TnIc and MHCα. Additionally, TnIc transcripts were shown to localize to the VMZ region via in situ hybridization. Furthermore, the expression of crescent, also a Wnt antagonist, led to the expression of muscle actin, a known marker of skeletal and cardiac muscle. Ectopic crescent expression also resulted in the localization of TnIc in the ventral explants. When examined at later stages of development (stage 41), the injection of both dkk-1 and crescent resulted in the generation of a heart beat in the VMZ explants. In addition, via immunohistochemistry staining, the VMZ explants expressed cardiac-specific isoform of troponin-T. Besides dkk-1 and crescent, the injection of GSK3β mRNA (which degrades β catenin and inhibits Wnt signaling) into ventral blastomeres was also shown to induce the expression of cardiac-specific genes, TnIc and MHCα. Together these experiments showed that the inhibition of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is sufficient for the formation of the heart in an ectopic ventral tissue.

Since the expression of Wnt antagonists in the VMZ caused the induction of cardiogenesis, the overexpression of Wnt proteins in the DMZ was expected to abolish cardiac formation. There are four Wnt genes expressed during gastrulation: Wnt3A, Wnt5A, Wnt8, and Wnt11. The injection of Wnt3A and Wnt8 cDNA into dorsal blastomeres resulted in the inhibition of cardiac gene expression. The DMZ explants from injected embryos had reductions in the expression of Nkx2.5 and TnIc. Interestingly, Wnt5A and Wnt11 injections did not change the cardiac gene expression profile. Together, these experiments involving tissue explants established the significance of Wnt signaling in heart development.

Besides DMZ and VMZ explants, animal cap tissue can also be utilized to study heart development. The cells in the naïve animal caps initially are pluripotent but do not spontaneously differentiate into cardiac tissue. Different concentration of activin can be added to the growth media in order to induce different cell fates. A low concentration of activin will promote the formation of ventral mesoderm, while growing embryos in a medium concentration of activin will result in the formation of dorsal mesoderm. Moreover, a high concentration of activin will stimulate the development of endodermal tissue. Since normal cardiogenesis relies on the interplay between the endodermal signal induction of mesodermal tissue, it is possible to use a specific activin concentration to enable communication between the endodermal and mesodermal layers. This approach improved our understanding of the role of canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling in heart development (Afouda et al., 2008). Since the canonical Wnt signaling pathway (Wnt/β-catenin) is known to suppress cardiac development, and non-canonical Wnt signaling (Wnt11/JNK) promotes heart formation, it is interesting to understand the factors involved in the interplay between these two opposing pathways. Specifically, the use of tissue explants simplifies the approach as the manipulation of these crucial developmental pathways in an entire embryo will be confounding due to the multiple tissues affected. Animal cap explants from embryos injected with activin mRNA were able to initiate cardiogenesis as indicated by the expression of cardiac specific markers such as GATA4, GATA6, Nkx2.5, etc. When an inducible form of β-catenin was introduced, it reduced the expression of GATA transcription factors. Moreover, an inducible form of GATA transcription factors rescued the phenotypes caused by the overexpression of β-catenin. These preliminary results suggested a regulatory pathway in which Wnt/β-catenin signaling suppresses GATA gene expression to prevent cardiogenesis. These results were further confirmed when gene expression analysis was compared in DMZ explants and whole embryos. Specifically, in the whole embryo, β-catenin overexpression reduced the expression of cardiac-specific genes MLC2 and TnIc; moreover, the activation of GATA in these embryos rescued this reduction in cardiac markers. These findings demonstrated that Wnt/β-catenin signaling has a negative effect on cardiogenesis, and that GATA transcription factors are downstream effectors in this process.

In order to understand the role of GATA transcription factors in the process of heart formation and to identify their downstream targets, a MO-mediated knockdown of GATA4 and GATA6 was performed in three different tissue samples: a DMZ explant, a VMZ explant injected with a Dkk-1 mRNA to stimulate cardiogenesis, and the whole embryo tissue. In all three sample, the reduction of GATA4 and GATA6 led to the reduced expression of Wnt11, a non-canonical Wnt ligand. Additionally, this work also confirmed that Wnt11 is a direct target of GATA4 and GATA6 transcription factors. Moreover, a MO-mediated reduction in Wnt11 both in the DMZ explants and whole embryos resulted in the reduced expression of cardiac-specific genes and differentiation into beating cardiomyocytes. These findings established the link between the canonical and non-canonical Wnt signaling in the process of heart formation. Using both DMZ and VMZ explants as well as whole embryos, this work established a negative regulation of GATA transcription factors by canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling. In turn, GATA factors were shown to directly induce the expression of Wnt11, which is part of the non-canonical Wnt11/JNK signaling pathway. More importantly, because all findings in the explants from the DMZ, VMZ and animal caps explants are consistent with the whole embryos findings, it justifies the use of explant tissue experiments to study specific organ development and to eliminate any additional spatio-temporal signaling factors present in the whole embryo.

This work in Xenopus was further expanded by the work done in mice focusing on the combination of factors necessary to induce cardiac tissue formation from mesoderm (Takeuchi & Bruneau, 2009). In these studies, the combination of two transcription factors, GATA4 and Tbx5, and a cardiac-specific subunit of BAF chromatin-remodeling complexes, Baf60c, induced the differentiation of cardiac myocytes from both non-cardiogenic posterior mesoderm and the extraembryonic mesoderm of the amnion. Interestingly, the combination of Gata4 and Baf60c stimulated the expression of cardiac-specific genes but failed to induce contractile tissue. The addition of Tbx5, however, resulted in the development of contracting cardiomyocytes. Moreover, Baf60c was shown to help GATA4 to bind to the loci of its cardiac target genes. These additional findings emphasized the importance of chromatin-remodeling complexes in the process of tissue-specific gene expression.

7. Xenopus as a system to understand human disease

7.1. The role of nucleoporins in CHD and heterotaxy

Xenopus is a rapid, cost-effective system that enables the screening of multiple candidate genes identified through large-scale genome sequencing studies in order to identify a role in cardiac development. The variety of methods available in Xenopus provides an opportunity to study genes with no known role in cardiac development or even genes with no defined role in development at all. For example, the use of Xenopus allowed us to discover a novel function of nucleoporins in development. Nucleoporin proteins are the building blocks of the nuclear pore complexes (NPCs). NPCs are massive (~100MDa) structures embedded in the nuclear membrane, the main function of which is to regulate nucleocytoplasmic transport. Each NPC contains about 30 nucleoporins that are organized into sub-complexes and share an eightfold concentric symmetry (Rout & Aitchison, 2000). The NPC scaffold contains the outer ring complex (Nup107–160 or “Y” complex) and the inner ring complex (Nup93 complex) (Hurt & Beck, 2015). The scaffold proteins play an important role for the NPC assembly as they anchor the other nucleoporins, including the Phe-Gly (FG)-rich nucleoporins. FG nucleoporins are particularly significant as they form a size-selective barrier for passive diffusion, and they have the ability to interact with nuclear transport receptors for active transport. While nucleoporins are best characterized by their role within the NPC, there is growing evidence about additional functions of nucleoporins during development. For example, a duplication of the inner ring Nup188 was found in a patient with heterotaxy and CHD (Fakhro et al., 2011). Considering a crucial role of NPCs play in cellular processes, it is interesting to know what effect such duplication would have on the organism development. Moreover, since nucleocytoplasmic transport is important for all cells, it is fascinating that this patient could have a potential alteration to the NPC structure and assembly, and could present with a specific developmental phenotype that spares some organs and tissues in the body.

The depletion of Nup188 with a MO caused abnormal heart looping in Xenopus embryos at stage 45 of development. Furthermore, since Nup188 forms an inner ring complex with other nucleoporins, we hypothesized that knockdown of Nup93, another inner ring protein that binds to Nup188, would also show a cardiac looping phenotype and indeed MO depletion of Nup93 did. To investigate the effect of inner ring nucleoporins on the left-right patterning, the expression of two markers was examined: pitx2 and coco (dand5, cerl2). The depletion of both Nup188 and Nup93 caused an abnormal, mostly absent, expression of pitx2. Furthermore, the loss of Nup188 and Nup93 resulted in a bilateral, symmetrical coco expression suggesting a ciliary dysfunction in the Left-Right Organizer tissue. To better understand this finding, MO injections were performed into one cell of the two-cell embryo. Since ciliary motility is crucial on the left side of the LRO where it represses the expression of coco (Vick et al., 2009), the injection of Nup188 MO into the left side had a more detrimental effect on heart looping compared to right sided targeting. This result further supported the potential cilia abnormality in the context of Nup188 and Nup93 depletion. Interestingly, the depletion of inner ring nucleoporins caused a reduction in cilia both in the frog LRO and in human retinal pigmented epithelial (RPE) cells. Moreover, the epidermal multiciliated cells were dramatically lost with Nup93 depletion. This result seemed specific to these inner ring nucleoporins as depletion of the outer ring nucleoporin Nup133 did not lead to cilia defects.

To eliminate the possibility that this phenotype could be due to a drastic disruption of nucleocytoplasmic transport, a NLS-GFP construct normally localized to the nucleus even in Nup93 or Nup188 depleted embryos. Furthermore, the density of the NPCs remained the same for injected and un-injected embryos. Additionally, the overexpression of Nup188, as seen in the patient, also led to abnormal heart looping and the loss of cilia in the LRO and the multiciliated cells. These findings suggested that changes in Nup188 levels neither affected nuclear transport, nor alter the number of NPC complexes per cell. While subtle changes could not be eliminated in NPC function, the investigators began looking for alternative functions for these inner ring nucleoporins.

Surprisingly, both Nup188 and Nup93 were also found at the cilium base where they co-localize with centrioles in Xenopus embryos and human RPE cells. Interestingly, these nucleoporins do not form a “ciliary pore complex” at the base of the cilium. First, these nucleoporins were found at the centriole rather than the transition zone which is where the ciliary diffusion barrier is thought to function. Next, using super-resolution PALM imaging, the size of the Nup188 puncta was much smaller when compared to the NPC dimensions and had no central pore. Finally, the Nup188 clusters were shown to form a structure consisting of two barrels that are perpendicular to each other in the pericentriolar material. This is a unique finding since it describes a novel subcellular localization of Nup188 outside of NPC. Moreover, the presence of Nup188 at the cilium base provides insight about why the depletion or overexpression of Nup188 has such a detrimental effect on cilium, left-right patterning and heart formation. Based on this work, the presence of two distinct cellular pools of Nup188 was subsequently confirmed (Vishnoi et al., 2020). Specifically, centrosomal accumulation of Nup188 in the pericentriolar material results from newly synthesized Nup188 protein. This Nup188 pool is distinct from the one present at the NPC, which is not exchanged or incorporated into the centrosomal Nup188 structures. Even after mitosis, nuclear Nup188 remains in the NPCs and is not redistributed into the centrosomal pool.

The presence and turnover of Nup188 at the centrosomes are regulated by proteasome activity. Interestingly, the turnover of centriolar Nup188 is more dynamic when compared with the NPC pool. This observation provides a plausible hypothesis why patients with either a duplication or depletion of Nup188 may have tissue-specific defects that spare some of the organs within a body. Since the NPC pool of Nup188 is more stable, the more dynamic centriolar pool of Nup188 will be more affected by the changes in Nup188 levels. Such changes in Nup188 expression will directly affect the structure and function of cilia, which is crucial for the establishment of left-right asymmetry of human body. Together these findings provide insight into the role of Nup188 in cilia structure and function, left-right patterning and cardiac formation.

In addition to Nup188, the role of other nucleoporins continues to be discovered in the context of development and congenital heart disease. Like Nup188, nucleoporin 205 (Nup205) is also a component of the inner ring complex of the NPC. Moreover, it is a paralogue of Nup188 (Beck & Hurt, 2017). Mutations in Nup205 have also been implicated as a cause of CHD (Chen et al., 2019). The depletion of Nup205 in Xenopus embryos caused abnormal heart looping and disrupted the expression of pitx2 and dand5 similar to Nup188 and Nup93 depletion (Marquez, Bhattacharya, Lusk, & Khokha, 2021). Moreover, nup205 depletion also resulted in the abnormal formation of the pronepros and suggested the role of Nup205 in kidney development as well. Due to the combination of cardiac looping and kidney phenotype, a ciliary defect was suspected in the Nup205-depleted embryos. Indeed, the loss of Nup205 resulted in the loss of cilia in the LRO tissue, epidermal MCCs and pronephroi. More importantly, Nup205 was also found to localize both to the NPC and the ciliary base. Furthermore, the depletion of Nup205 caused an abnormal docking of basal bodies to the apical cell surface. Similarly, the depletion of Nup93 and Nup188 also led to the mislocalization of the basal bodies. To better understand this connection between inner ring nucleoporins in the ciliary function, MO-mediated depletion of Nup205, Nup93 and Nup188 was performed and resulted in the loss of cilia. Interestingly, the ciliary loss caused by the depletion of Nup188 and Nup205 was rescued by the expression of either Nup188 or Nup205. On the other hand, ciliary defect from the depletion of Nup93 was rescued by Nup93 expression only. Therefore, this suggests a redundant function of Nup188 and Nup205 at the ciliary base. This work describes a novel subcellular localization of nucleoporins and their new function within the context of ciliary biology and human disease.

7.2. Patient-driven gene discovery and insights into developmental pathways with Xenopus

7.2.1. Wnt/β-catenin pathway

Mutations in guanine nucleotide exchange factor (RAPGEF5) have been reported in patients with CHD and heterotaxy (Fakhro et al., 2011). This factor has recently been shown to contribute to the Wnt signaling pathway via regulating nuclear translocation of β-catenin (Griffin et al., 2018). The Wnt signaling pathway plays an important role in the development of embryonic tissue and its dysregulation contributes to cancer. A key step in this pathway is the nuclear import of β-catenin. In the absence of Wnt ligand binding, β-catenin remains in the cytoplasm, where is undergoes phosphorylation by the β-catenin degradation complex and subsequent degradation by the proteasome. However, when the Wnt ligand is bound to its receptor, the β-catenin degradation complex is inhibited, and β-catenin can translocate into the nucleus, bind to the TCF/LEF and induce the expression of Wnt-responsive genes. Although crucial, the mechanism of β-catenin nuclear import remains unknown. The nuclear transport receptor for β-catenin import has not been identified yet. However, these is evidence that the nuclear import of β-catenin requires energy and a GTPase activity (Fagotto, 2013).

To understand the contribution of RAPGEF5 to CHD and heterotaxy, its effect on left-right patterning was examined first. The depletion of RAPGEF5 resulted in an abnormal cardiac situs and abnormal expression of pitx2 (a marker of left-right patterning) in the lateral plate mesoderm. Interestingly, the expression of coco in the LRO tissue was reduced even before extracellular flow was initiated to break the left-right symmetry. Moreover, the expression of other LRO markers, xnr1 and gdf3, was also significantly reduced when RAPGEF5 was depleted. These findings suggested that the reduction of RAPGEF5 expression prevented the proper patterning of the LRO tissue. Since the LRO is derived from the superficial dorsal mesoderm and is formed near the end of gastrulation, the expression of dorsal mesodermal markers was examined. Specifically, the depletion of RAPGEF5 caused the reduction of foxj1 and xnr3 expression. These two genes are known direct targets of the Wnt signaling pathway. Interestingly, reduced expression of RAPGEF5 caused changes in both total β-catenin levels as well as in stabilized (unphosphorylated) β-catenin levels. To understand such an effect on β-catenin levels and what roles RAPGEF5 could play in this pathway, the investigators used the Xenopus secondary axis assay. The overexpression of β-catenin is known to induce secondary axes in Xenopus embryos (Funayama, Fagotto, McCrea, & Gumbiner, 1995). This strategy is extremely useful as the resulting secondary axes can be easily examined in live embryos under the light microscope. Interestingly, the depletion of RAPGEF5 significantly reduced the formation of secondary axis caused by the injection of both wildtype and surprisingly stabilized β-catenin mRNAs. This result was also consistent with the findings from a TOPFlash luciferase assay, in which the expression of luciferase is under control of TCF/LEF binding. In this assay, the depletion of Rapgef5 significantly reduced the luciferase signal. These findings suggested a negative regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway by the depletion of RAPGEF5.

Of note, the depletion of Rapgef5 reduced nuclear accumulation of β-catenin. More importantly, when a β-catenin fusion to an N-terminal classic nuclear localization signal from SV40 large T antigen was expressed, RAPGEF5 depletion had no effect. This NLS is known to interact with the Ran/importin-β1 nuclear transport pathway. These findings indicated that nuclear localization of β-catenin via RAPGEF5 was independent of Ran/ImportinB1. Moreover, this study also confirmed the nuclear localization of Rapgef5 and its connection to the nuclear Raps, which are known to interact with β-catenin. This work is yet another example how Xenopus could be used to elucidate the mechanisms behind human disease and identify new genes involved in conserved developmental pathways. Moreover, since nuclear translocation of β-catenin contributes to the development of colorectal cancer, these findings could be used in therapeutic applications.

7.2.2. Notch pathway

A heterotaxy gene GALNT11, encoding for a polypeptide N-acetylgalactosaminyltransferas e, has been shown to play a crucial role in the Notch signaling pathway (Boskovski et al., 2013). GALNT11 controls the initiation of GalNAc-type O-glycosylation and had no known function in cardiac development or heterotaxy. Hence, this example further emphasizes why we need an efficient system, such as Xenopus, to test these candidate genes. In order to understand the role of GALNT11 in cardiac development, the process of heart looping was examined in GALNT11-depleted embryos. In addition to abnormal heart lopping, these embryos also had abnormal expression of pitx2 and coco, which suggested a defect in the cilia-mediated leftward flow of extracellular fluid in the LRO. Given the ease at which epidermal MCCs can be assayed for cilia since they are external and abundant, the examination of the epidermal MCCs revealed that GALNT11 knockdown increased the density of MCCs on the epidermis, while the overexpression of GALNT11 caused a decreased density of MCCs. This phenotype mimicked Notch signaling effects on MCC formation suggesting that GALNT11 may play a role in this pathway. Notch signaling consists of multiple factors. Specifically, it requires the binding of the Delta or Jagged ligand to the transmembrane Notch receptor, and the CBF1/Su(H)/Lag-1 (CSL) transcription factor complex. The binding of the ligand induces multiple cleavage events that result in the release of the Notch intracellular domain (NICD), its translocation into the nucleus to drive the expression of Notch-responsive genes. In order to test the contribution of Galnt11 to the Notch signaling pathway, a rescue experiment was carried out using Notch pathway members to attempt a rescue of the Galnt11 knockdown phenotype in the pitx2 assay. Delta gain-of-function did not rescue the abnormal pitx2 expression in the Galnt11 morphants. However, both nicd and a constitutively active CSL protein rescued the phenotype. This suggested that Galnt11 functions downstream of the Notch receptor binding by the Delta ligand. Considering that Notch receptor is subject to different O-glycosylations, mass spectrometry analysis was used to identify whether the Notch receptor can also be a target of the GalNAc-type-O-glycosylation. It was found that there is a glycosylation site right next to the ADAM protease cleavage site within the Notch receptor. This glycosylation appears to enhance the cleavage of the Notch receptor and increase the release of the NICD from the membrane enhancing Notch signaling.

In order to better understand the connection between ciliary function, Notch signaling pathway and Galnt11 function, the LRO cilia was examined using live imaging. Based on the two cilia model (McGrath et al., 2003; Tabin & Vogan, 2003), there are two types of cilia in the LRO: motile cilia that generate extracellular fluid flow to break the left-right symmetry, and immotile cilia located in the periphery of the LRO that mechanically sense the extracellular fluid flow and drive downstream signaling. A major question in the field was how are two cilia types specified in the LRO: motile and immotile cilia. When notch1 was overexpressed, the LR phenotypes mimicked cilia immotility while when galnt11 or notch1 were depleted, the LR phenotypes suggested that there was a loss of cilia signaling. One possible explanation is that with gain of Notch signaling, immotile cilia were preferentially formed while with loss of Notch signaling, motile cilia formed. Indeed, by live confocal imaging cilia in the Xenopus LRO, the overexpression of nicd resulted in a reduced ratio of the motile to immotile cilia. In contrast, the knockdown of notch1 or galnt11 demonstrated a reverse phenotype with an increased ratio of motile to immotile cilia. Consistent with this finding, the overexpression of nicd or Galnt11 reduced the expression of Foxj1 and Rfx2, critical transcription factors that regulate motile ciliogenesis. Together these results indicate that the identity of the cilia was changed from immotile to motile. This work is a great example of how Xenopus can be used to understand the role of novel candidate genes in signaling pathways affecting both Notch signaling and ciliary function. More importantly, it reveals a plausible mechanism of human disease, even when there is just a small cohorts of patients lacking the second allele to define disease causality.

7.3. CHD and Down syndrome

Xenopus can be used as a model organism to study diseases with rather complex phenotypes. For example, patients with Down syndrome often present with multiple cardiac malformations including tetralogy of Fallot, patent ductus arteriosus, atrial and ventricular septal defects. Therefore, it is rather interesting to discover genes responsible for such complex phenotypes. One such candidate gene is congenital heart disease protein 5 (CHD5), or tryptophan-rich basic protein (WRB). This gene is located within the restricted region of chromosome 21 in patients with both Down syndrome and heart defects. It is unknown whether CHD5 has a distinct function in heart formation that is independent of Trisomy 21. The analysis of CHD5 mRNA expression in the Medaka fish (Oryzias latipes) via in situ hybridization revealed signal in the differentiating ventricle in the endocardial cells at stage 28 (Murata, Degmetich, Kinoshita, & Shimada, 2009). Later, at stages 35 and 39, CHD5 mRNA and protein were found in the looped ventricle and atrium. The depletion of CHD5 using a morpholino resulted in abnormal heart looping, atrium elongation and abnormally large ventricles. Besides cardiac abnormalities, these morphants also had defects in ocular development characterized by narrowed interpupillary distances and cyclops. Together these findings support a contribution of CHD5 to heart development; however, they do not demonstrate a distinct role of CHD5 in cardiac formation that is independent from Trisomy 21.

In addition to CHD5, the zinc-finger transcription factor CASTOR (CASZ1) was implicated in vertebrate heart development. Specifically, the reduction in CASZ1 in Xenopus embryos prohibited cardiac progenitor cells from differentiating into cardiac myocytes, which resulted in cardia bifida and abnormal cardiac morphogenesis (Christine & Conlon, 2008). A link between CASZ1 and CHD5 was established using a yeast two-hybrid system, where full-length CASZ1 was evaluated for its interaction with a library generated from the stage 28 Xenopus cardiac enriched tissue (Sojka et al., 2014). Moreover, in vivo interaction between these two proteins was confirmed using co-immunoprecipitation in Xenopus embryos. Additionally, both CASZ1 and CHD5 had expression in the developing myocardium and co-localized to the nuclei of cardiomyocytes in Xenopus embryos. Interestingly, MO-mediated depletion of chd5 in Xenopus did not demonstrate any cardiac specification defects at early tadpole stages of development. However, reduced levels of chd5 had a detrimental effect on later cardiac development at stage 37. Specifically, the reduction of CHD5 did not affect initial differentiation as the expression of tropomyosin, a cardiac marker, remained intact. Low CHD5 levels, however, abolished the processes of cardiac looping and chamber formation, and resulted in a thicker myocardial layer. Moreover, the depletion of CHD5 prevented cell movements toward the midline and fusion of the cardiac fields. Parts of the heart also had disrupted cell movements even prior to chamber formation. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) also revealed that reduction in CHD5 levels caused a failure in cell shape changes that are normally required for maturation of the linear cardiac tube. Additionally, similar phenotypes were observed when CASZ1 was depleted; however, CHD5 depletion caused more severe phenotypes.

In terms of the mechanism behind these cellular changes, CHD5-depleted embryos had decreased cardiomyocyte numbers and a lower mitotic index rather than an increased level of apoptosis. Moreover, the depletion of both proteins caused a looser association of the cells within cardiac tissue indicating that these proteins may play a role in the cell-to-cell adhesion processes. Indeed, the expression of zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1), a tight junction marker, was either diffuse or absent in the myocardial tissue with reduced levels of CHD5 and CASZ1. Additional transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis of CHD5- and CASZ1-depleted Xenopus embryos revealed increased gaps between cardiomyocytes, breaks in the basement membrane of the myocardium, and the ectopic deposition of laminin in the deeper myocardial layers. Together these findings indicate that these proteins have an important function regulating the integrity of the myocardial tissue. Additionally, the expression of ZO-1 and claudin-5 were reduced and demonstrated a diffuse pattern of deposition in CHD5- and CASZ1-depleted embryos. In contrast, no changes were observed in the expression of β1-integrin. These findings suggested that the depletion of these two proteins specifically change the structure of the tight junctions rather than globally changing the extracellular matrix-cytoskeletal junctions.

This work also examined the nature of interaction between CASZ1 and CHD5. Specifically, the depletion of CHD5 did not affect the expression or nuclear localization of CASZ1. However, the activity of CASZ1 was found to depend on its interaction with CHD5. While the CASZ1 depletion phenotype was partially rescued by the full-length CASZ1 mRNA injection, the CASZ1 mRNA lacking the CHD5-interacting domain (CID) did not rescue the CASZ1 depletion phenotype. This finding suggests that while CHD5 does not influence the expression or nuclear localization of CASZ1, its interaction is necessary for the activity of CASZ1 in cardiac development. Additionally, the overexpression of either full-length of CASZ1 or its CHD5-interacting domain (CID) resulted in the abnormalities of the cardiac looping and morphogenesis defects. Therefore, a balanced interaction between CASZ1 and CHD5 is necessary for proper cardiac development.

7.4. CHD and chromatin regulators

Recent large scale studies of CHD have shown an enrichment of de novo mutations in chromatin modifiers. Hence, there has been substantial interest in understanding the role of these genes in heart development. Novel functions of chromatin regulators in heart development have been discovered using Xenopus as a model organism. A de novo mutation in WDR5 was identified in patients with heterotaxy and CHD (Jin et al., 2017). The role of WDR5 in chromatin remodeling is well-defined: it is a scaffolding protein in the H3K4 methyltransferase complex. Methylation of lysine 4 in histone 3 (H3K4) plays an important role in the gene expression regulation. In particular, the tri-methylation of this residue is often found within the promoter of active genes, while the mono- and di-methylation of H3K4 is often present within enhancer regions. However, the role of WDR5 in development or heart formation had been unknown. Since the patient carrying a de novo missense WDR5 mutation presented with a right (rather than a normal left) aortic arch, a defect in Left-Right patterning was suspected. The depletion of WDR5 using a morpholino caused both LR patterning markers, pitx2 and dand5, to have an abnormal expression (Kulkarni & Khokha, 2018). Since the disruption of cilia on the left side of the LRO has more detrimental effects on LR patterning (Vick et al., 2009), the injections of WDR5 MO were performed into one cell of the two-cell embryo. The depletion of WDR5 on the left side of the embryo resulted in a higher percentage of abnormal pitx2 and dand5 expression as compared to the right-side injections. This suggested a role of WDR5 in ciliary function. Indeed, using confocal microscopy, the depletion of WDR5 resulted in shorter cilia that were reduced in number in the LRO.

Given the loss of cilia, the expression of cilia-specific genes dnah9, rfx2 and foxj1 were examined in the LRO. The expression of dnah9 and rfx2 remained intact. However, the depletion of WDR5 caused reduced levels of foxj, which is a known target of WDR5 methyltransferase activity. The injection of foxj1 mRNA into WDR5-depleted embryos rescued the phenotype confirming foxj1 as a downstream effector of the WDR5 action providing an explanation for the loss of cilia.

Interestingly, during the course of these experiments, WDR5 was found to have an H3K4-independent role in the LR patterning, which had not been appreciated before. In addition to abnormal cilia in the LRO, WDR5 is also essential for the cilia in MCCs on the epidermal surface. Depletion of WDR5 dramatically eliminates the cilia in the MCCs which are responsible for a brisk extracellular fluid flow much like the mucociliary clearance in mammalian lungs. As expected, depletion of WDR5 dramatically eliminated the extracellular fluid flow across the epidermal surface and the addition of human wildtype WDR5 rescued this loss of flow. Biochemically, WDR5 binds different subunits of the methyltransferase that is essential for methyltransferase activity. An S91K WDR5 mutant completely abolishes this binding as well as methyltransferase activity. Unexpectedly, the S91K WDR5 mutant rescued the extracellular fluid flow and cilia of the MCCs in WDR5 depleted embryos suggesting a non-chromatin role for WDR5. Consistent with this finding, the patient had a K7Q mutation. For methyltransferase activity, the first 26 amino acids of WDR5 are not necessary which has been established functionally, biochemically, and by crystallo-graphic structure and therefore the relevance of a K7Q mutation in the patient was far from certain. Using Xenopus, the K7Q mutation could not rescue the WDR5 depletion phenotype in the MCC indicating that it was critical for function in this context. While investigating non-chromatin molecular mechanism of WDR5, WDR5 was localized to the base of the cilia and appeared essential for the formation of the actin network in which the basal bodies of cilia are embedded at the apical surface of a MCC. In fact, the K7Q mutation appeared to affect the ciliary localization of WDR5 providing an explanation of its pathogenicity. Taken together, these results suggest that the examination of genes in the context of patient phenotypes and the investigation of pathogenic molecular mechanism can reveal new functions for proteins that had previously been considered only in a single context. Patient-driven gene discovery and molecular mechanism analysis can identify new functions for proteins thought to be already carefully characterized.

Other chromatin modifications have been shown to contribute to cardiac development by controlling ciliary motility rather than ciliogenesis (Robson et al., 2019). Specifically, de novo mutations affecting genes that affect the monoubiquitination of histone H2B on K120 (H2Bub1) were identified in patients with CHD. H2Bub1 is catalyzed by the RNF20-RNF40 complex together with the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme UBE2B. MO-mediated depletion of rnf20 resulted in abnormal expression of both pitx2 and dand5, especially when rnf20 was depleted on the left side of the embryo. Additionally, rnf20 was found to be expressed in the LRO and multiciliated tissues in Xenopus and mouse including oviduct, trachea, and brain. Together these findings suggested a role of rnf20 in the function of the cilia. The depletion of rnf20 using a MO did not affect the cilia length, number, or the orientation in the LRO. However, it reduced the ciliary rotational frequency. Moreover, a similar motility defect was observed in the multiciliated cells of the Xenopus epidermis, while the morphology and distribution of the cilia remained intact. Furthermore, the depletion of rnf20 resulted in the reduction of the epidermal fluid flow. Additionally, TEM analysis revealed shortened or absent inner dynein arm in the epidermal cilia of the rnf20-depleted embryos. Since rnf20 is part of a complex, the contribution of other members to the ciliary function was examined. The loss of other components, including rnf40 and ube2b, in combination with rnf20 resulted in the reduced velocity of the epidermal cilia. Therefore, other members of the complex contribute to the proper motility of the cilium.

To identify the possible mechanism behind RNF20 complex activity, the levels of H2Bub1 were examined throughout development and were found to be upregulated during the formation of both the LRO and the epidermal cilia. Additionally, when rnf20 is depleted, the levels of H2Bub1 were reduced suggesting a developmental regulation of H2B modification, which is dependent on the Rnf20 activity and correlates with the formation of the LRO and epidermal cilia. Using ChIP-Seq, a ciliary transcription factor Rfx3 was identified as one of the genes enriched with H2Bub1 marks. To determine the downstream targets of rnf20, the expression levels of ChIP-Seq target genes was examined in the LRO. Using qPCR analysis of the LRO tissue from the rnf20-depleted embryos, reduced levels of dnah7 and rfx3 mRNAs were detected. Additional analysis using in situ hybridization examining the localization of these transcripts and RNA-Seq experiments confirmed these results. Moreover, overexpression of rfx3 rescued the defects in ciliary motility, epidermal flow and abnormal pitx2 expression in the rnf20-depleted embryos. This result established that monoubiquitination of histone H2B by RNF20 complex activates rfx3 transcription, which acts an important transcription factor for cilia genes, including dyneins. Therefore, RNF20 mutations identified in the CHD patients have a direct detrimental effect on the ciliary function and subsequent left-right patterning and cardiac development.

Additional chromatin modifiers have been implicated in cardiac development and disease. Mutations in the H3K4 methyltransferase KMT2D have been identified in patients with Kabuki syndrome (Schwenty-Lara, Nürnberger, & Borchers, 2019). Kabuki syndrome is a rare, autosomal dominant disorder characterized by malformations of multiple organ systems. Multiple abnormalities include distinct facial features (cleft palate and abnormally small jaw), short stature, intellectual disability and skeletal abnormalities. The two most common cardiac manifestations in children with Kabuki syndrome include the narrowing of the main artery in the body (coarctation of the aorta) and the presence of holes between heart chambers (atrial and ventricular septal defects). Other malformations include renal dysplasia or hypoplasia, hydronephrosis and the fusion of two kidneys (a horseshoe kidney).

KMT2D is a large protein capable of catalyzing mono-, di- and tri-methylation reactions. Moreover, the C-terminus of this peptide contains the SET domain that is necessary for its methyltransferase activity. Using in situ hybridization, it was shown that KMT2D is ubiquitously expressed in Xenopus at stages of cardiac development, with enrichment in the anterior region including cardiac precursor cells. To understand the impact of KMT2D mutations on heart formation, a MO-mediated depletion of this protein was performed in the cardiac mesoderm and the expression of α-myosin heavy chain (MHCα) was examined. Control embryos maintained the expression of MHCα in the atria, the ventricle, and the jaw. In contrast, KMT2D morphants developed cardiac abnormalities and a misplacement/reduction of jaw muscles. Heart defects included a hypoplastic morphology including malformed, laterally displaced hearts as well as the formation of tube-like structures that lacked three-chamber structural organization. These findings were also consistent with the histological sections demonstrating a narrow lumen with no separation of the heart tube into atria and a ventricle. In addition, the depletion of KMT2D affected cardiac differentiation. Specifically, it resulted in an abnormal expression of MHCα at the onset of cardiac differentiation and cardiac Troponin I, a marker of terminal differentiation.

To evaluate the impact of KMT2D depletion on the development of the first and second heart fields, the expression of Tbx20 and Isl1 were examined, respectively. KMT2D morphants had reduced levels of Tbx20 and the cells expressing Tbx20 were positioned more posterior than in un-injected embryos. The expression of Isl1 was also reduced in the KMT2D morphants, however, there was no cell misplacement. This result confirmed an important role of KMT2D in the cardiac differentiation and the establishment of the first and second heart fields. Additionally, the expression of Nkx2.5 was examined since it contributes to the development of both first and second cardiac fields. The depletion of KMT2D resulted in a reduced number of cells expressing of Nkx2.5, with some of cells demonstrating a complete loss of Nkx2.5 expression. These results suggested that KMT2D depletion has a global effect on cardiac specification early on in development. The analysis of gene expression in the precardiac precursor cells showed that KMT2D did not have an effect on this process. Together these findings show that KMT2D does not influence early cardiac development but becomes crucial during the separation of first and second heart fields.

8. Conclusion

The significant burden of congenital birth defects on child health requires more efficient, accessible and affordable diagnostic and treatment methods. To develop such practices, we must better understand the mechanisms leading to the development of birth defects. The advances in genome sequencing combined with the decline in its costs allow for identification of multiple genes in patients with CHD and heterotaxy, a few of which are described in this article. However, sequencing by itself does not provide answers to patients about the pathogenesis of their conditions. Considering the broad spectrum of molecular pathways these genes have been found to contribute to, it is important to appreciate how complex these diseases are in terms of physiology and embryo development. Moreover, we also need to consider utilizing a proper model organism that will allow for the exploration of patient phenotype and underlying mechanisms. Based on multiple examples described in this article, Xenopus does serve as an efficient, rapid, cost-effective system that offers a variety of methods to study congenital malformations. The ability to model human disease in Xenopus will allow us to understand disease pathogenesis. In turn, this will not only provide answers to patients and their families, but will also allow for better counseling regarding future risks based on the mechanism of pathogenesis of the disease. Moreover, crucial laboratory findings can be brought back to patient care via improvements in diagnostic testing, tailored treatment methods, and specific outcomes. Importantly, since most genetic syndromes are grouped based on shared phenotypes, specific genotype information will allow for a more precise management and outcome predictions in patient that may explain clinical outcome differences even though some of the phenotypes are shared. Therefore, as sequencing becomes more rapid and less expensive, the need for high-throughput screening platforms to model patient disease will increase, and Xenopus provides all the tools that can be used for this process. Finally, this patient-driven gene discovery process will establish the necessary collaboration between different experts in the fields of medicine and biological sciences. Specifically, clinicians can provide care to patients suffering from birth defects, while medical geneticists can identify the candidate genes mutated in those patients. Furthermore, biomedical scientists in the variety of disciplines including developmental, cellular and molecular biology can combine their efforts to explore the complex mechanisms and signaling pathways that could be dysregulated in patients affected by CHD and heterotaxy. This collaborative effort in combination with the advantages of proper model organisms, such as Xenopus, will lead to the improvements in care for patients with CHD, heterotaxy, and birth defects in general.

Footnotes

Author conflict of interest

None.

References