Abstract

Although grief is a reaction to a social loss, it has been viewed almost exclusively through the lens of individual psychology and not sociology. In this article, we suggest that more attention to sociological aspects of grief is warranted. We propose a micro-sociological theory of bereavement and grief to complement, not replace, psychological perspectives. We assert that bereavement represents a state of loss-associated social deprivations (e.g., social disconnection). Further, we postulate that addressing social deprivations (e.g., enhancing social connection) will lessen severity of distressing, disabling grief and, thereby, promote adjustment to loss. Future research is needed to test our theory and the hypotheses that follow from it in the service of promoting adaptation to bereavement.

Introduction

Although grief is a reaction to a social loss, it has been viewed almost exclusively through the lens of individual psychology. Indeed, much of our work in this area has focused on psychological symptoms in bereaved individuals rather than the social impact of bereavement. We have sought to differentiate grief from other forms of intrapersonal psychological distress, (e.g., depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress), and our research helped to usher the inclusion of prolonged grief disorder (PGD) as an official individual psychopathological disorder into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).1,2,3 Despite these advances, we believe that more attention to sociological aspects of grief and bereavement is warranted. In this article, we attempt to advance a micro-sociological perspective on adapting to interpersonal loss to complement, not replace, psychological perspectives. We introduce micro-sociological conceptions of bereavement within the theory and formulate consequences of the theory.

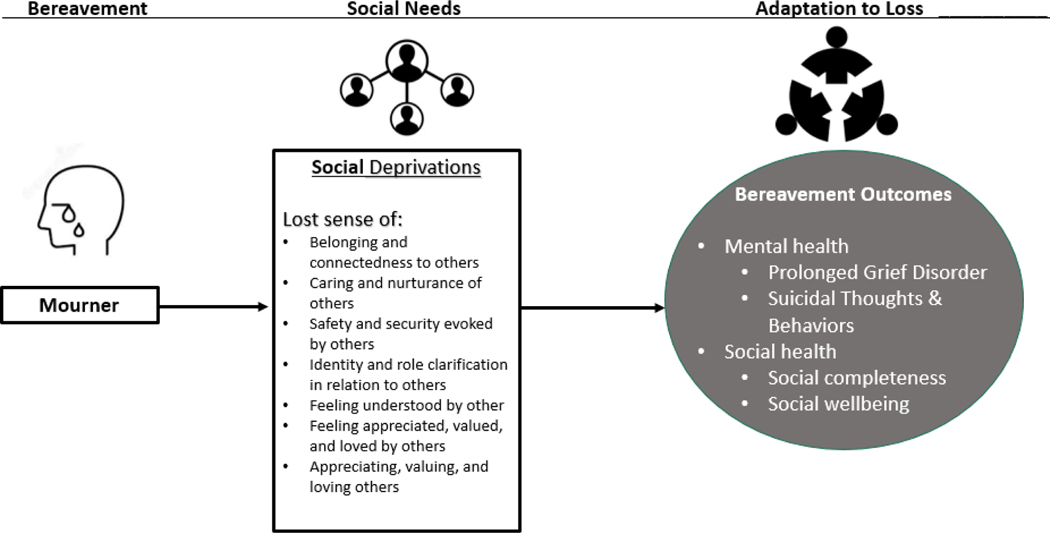

Core tenets of a micro-sociological theory of bereavement (see Figure 1)

Figure 1.

A Conceptual Model Relating the Satisfaction of Social Needs to Bereavement Adjustment

In our nascent formulation of this theory, we adopt a symbolic interactionist perspective4,5 and build on social interactionist notions, i.e., social worlds,6,7 social identities,8,9 and social interactions in the construction of and participation in those worlds and identities. Symbolic Interactionism10 provides a sociological framework for understanding how individuals interact with one another to create symbolic worlds and how these worlds shape individual behaviors.11 Adaptation to loss is a process of micro-social reorganization in the context of loss-associated social deprivation (“micro-” here referring to individual interaction within small groups, in contrast to “macro-“ which would refer to larger social interactions across organizations). It is a process of psychosocial reconstruction, of transition from a disintegrated social life moored to a constellation of lost and disrupted social worlds, identities, and patterns of behavior to a cohesive social life committed to the renovation of old and construction of new relationships.

Our micro-sociological theory of bereavement includes three basic principles: First, bereavement results in a partial void in one’s social state (what we refer to as a mourner’s social space). This void in the mourner’s social space needs to be filled. The size of the void created by the loss -- the amount of social space the deceased filled, and the ways in which the deceased filled it, leads to displacement from a prior state of social equilibrium and wholeness. Second, part of adapting to a significant interpersonal loss is the process of filling this social void, of establishing a new state of social equilibrium that satisfies one’s social needs and desires. Third, everyone’s grief is distinct in that bereavement and its associated grief are related to the physical loss of a unique relationship and social constellation. However, while each mourner’s social space is depleted in unique ways, there is also a universality to the experience. It is, thus, also true that everyone’s grief is similar in that every bereaved individual experiences a social vacuum created by bereavement.

For a bereaved individual, the physical separation from the other that occurs after the death results in a severe form of social deprivation for the mourner. The mourner must confront the consequential reality that this significant other and relationship is forever transformed. From a micro-sociological perspective, the bereaved individual has lost key dimensions of the dyadic relationship with the deceased person, and the absence of the deceased in their interactions in larger (but still micro) social groups. For example, a recently widowed man who had a close relationship with his now deceased spouse is likely to have his micro-social worlds, identities, and interactions altered in a variety of ways. It leaves a void, or vacancy, in his social space (see Box 1). First and foremost, this widower has lost the micro-social world, identity, and patterns of behavior that he had created and shared with his wife. However, other aspects of his social existence are also forever changed. The widower has not only experienced change in the relationship with his deceased wife or role, but also must renegotiate, reformulate, and reconsider his identity and interactions with other extant social relationships and casual acquaintances in his broader social world. These derivative effects of the lost relationship may exacerbate or ameliorate the widower’s sense of social deprivation. His sense of belonging or connectedness with others in the micro-social space has been disrupted, and it no longer includes caring or nurturance of others, and the various other social dimensions filled by his wife. The void in one’s social space created by the loss hence depletes a mourner’s state of social health, completeness, and fulfillment. In this way, we assert that bereavement, at its core, represents a state of loss-associated social deprivation.

Box 1. Basic Concepts of a Micro-Sociological Theory of Grief.

Terminology

Bereavement – a state of loss-associated social deprivation

Grief – a process involving micro-social reorganization in the context of loss-associated social deprivation

Social space – the area filled by others in satisfying social needs

Social Needs

Belonging and connectedness to others

Caring and nurturance of others

Safety and security evoked by others

Identity and role clarification in relation to others

Feeling understood by other

Feeling appreciated, valued, and loved by others

Appreciating, valuing, and loving others

Axiom

The more effectively mourners satisfy their social needs (i.e., fill the social spaces vacated by bereavement), the less distressing and disabling their grief, and the more likely they will be to achieve a state of social completeness and wellbeing.

Adaptation to loss involves filling the social void created by the loss. For a bereaved individual, the meaning and significance of their former connection to the deceased person exist within extant and de novo social relationships. It is important to consider that surviving and emerging interpersonal relationships not only provide opportunities for socially rewarding interactions, but also may pose dilemmas for the bereaved survivor as might be the case for evolving social identities. The absence of the deceased affects emotions, daily routine, and ability to engage in potentially satisfying activities and experiences. Mourners must engage in micro-social reorganization to meet their social needs. Our theory leads us to postulate the following: the more effectively mourners are able to address their social needs and fill the social space vacated by bereavement, the less distressing and disabling their grief, and the more they will be able to return to a state of social connectedness, wellbeing, and health.

Micro-sociological interpretations of grief symptoms

Our preceding sketch of a micro-sociological theory of bereavement introduces a new paradigm within which one may interpret grief and PGD symptoms. A comparison of psychological and micro-sociological perspectives of grief symptoms has useful implications for both the assessment of grief and targets of grief interventions.

Table 1 presents items used to assess PGD in the DSM-5-TR and grief in the PG-13-R along with categorizations and interpretations of these symptoms within coincident psychological and micro-sociological domains. Within the psychological domain, the focal event is the death of a close other; symptoms of grief represent aspects of the bereaved individual’s psychological response to that death, a process of working through and reducing these symptoms. Within the micro-sociological domain, the focal event is the loss of a close relationship and related disruptions of the mourner’s social world; signs of grief represent aspects of the bereaved individual’s social deprivation due to that end; grief is a process of micro-social reorganization on a path toward fulfillment of social needs and desires, or as we conceptualize it, filling the social space vacated by the deceased close other.

Table 1.

Psychological and Micro-Sociological Perspectives on Grief Symptoms

| Psychological Domain | Micro-Sociological Domain | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| Criterion | DSM-5-TR Item | PG-13-R Item | Category | Interpretation | Category | Interpretation |

|

| ||||||

| A | Death of a close other | Have you lost someone significant to you? | Event | Death of a close other and related separation distress? | Event | Loss of a close social relationship and related social disruption |

| B.1 | Intense yearning/longing | Do you feel yourself longing or yearning for the person who died? | Affective | Primary affective response to the death of a close other | Socio-affective | Social emotional desire to continue the lost social relationship |

| B.2 | Preoccupation with thoughts or memories of the deceased person | Do you have trouble doing the things you normally do because you are thinking so much about the person who died? | Cognitive | Cognitive aspect of yearning/longing | Socio-cognitive | Social cognitive desire to continue the lost social relationship |

| C.1 | Identity disruption | Do you feel confused about your role in life or feel like you don’t know who you are any more (i.e., feeling like that a part of you has died)? | Cognitive | Identification with the deceased person | Social Identities | Dislocation of social identity defined within the lost social relationship |

| C.2 | Disbelief about the death | Do you have trouble believing that the person who died is really gone? | Cognitive | Denial; Blocking the reality of the death of a significant other from thought | Socio-cognitive | Persistence of symbols/meanings from the lost social relationship |

| C.3 | Avoidance of reminders that the person is dead | Do you avoid reminders that the person who died is really gone? | Behavioral | Behavioral aspect of disbelief | Socio-cognitive | Resistance to decomposition of symbols/meanings from the lost social relationship |

| C.4 | Intense emotional pain related to the death | Do you feel emotional pain (e.g., anger, bitterness, sorrow) related to the death? | Affective | Secondary affective responses to the death of a significant other | Socio-affective | Decomposition of emotional ties to the lost social relationship |

| C.5 | Difficulty with reintegration into life after the death | Do you feel that you have trouble re-engaging in life (e.g., problems engaging with friends, pursuing interests, planning for the future)? | Behavioral | Behavioral aspect of preoccupation with thoughts or memories of the deceased person | Social Interactions | Resistance to reorganization of symbols/meanings from the lost social relationship |

| C.6 | Emotional numbness as a result of the death | Do you feel emotionally numb or detached from others? | Affective | Emotional shock in response to the death of a significant other | Socio-affective | Void in social emotional ties created by the loss of the social relationship |

| C.7 | Feeling that life is meaningless as a result of the death | Do you feel that life is meaningless without the person who died? | Cognitive | Appraisal of life’s significance in the wake of the death of a significant other | Socio-cognitive | Decomposition of symbols/meanings from the lost social relationship |

| C.8 | Intense loneliness as a result of the death | Do you feel alone or lonely without the deceased? | Cognitive | Perception of being socially isolated | Social Interactions | Void in meaningful social interactions created by the loss of the social relationship |

Recent empirical research from the perspective of the new theory

To date, much more empirical research on grief has focused on psychiatry and clinical psychology rather than sociology. Further, work that does include and examine social factors in grief is neither cast nor interpreted in micro-sociological, symbolic interactionist terms. Nevertheless, there are some recent studies whose findings may be viewed as consistent with, and potentially supportive of, the micro-sociological theory of bereavement outlined above.

In addition to meeting the social needs outlined in Box 1, social relationships impact grief adjustment via psychological pathways. They offer important roles and opportunities to manifest aspects of the mourner’s identity and to further their sense of purpose in life. They also can facilitate adaptive meaning reconstruction of narratives that bereaved individuals develop of the life and death of a deceased close other, which is a central feature of adaptive grieving processes.12,13,14,15 [cross-reference Neimeyer article] Recent empirical studies have found that meaning reconstruction is inversely related to PGD symptomatology,16,17 mediates associations between socially-relevant risks for PGD (e.g., attachment style, grief-related social support, and relationship to the deceased) and development of PGD symptomatology,18 and serves as a viable foundation for a new meaning-centered grief therapy.19

In close peer social relationships, e.g., close friendships and spousal relationships, individuals interact with others in meaningful ways that help define these micro-social worlds and their identities within in them. Thus, within our micro-sociological theory of bereavement, we would expect that: (Hypothesis 1) loss of a close other creates a large social void (state of bereavement) and it is a sizeable task (process of micro-sociological reorganization) to fill it, and (Hypothesis 2) social interactions within close relationships are an effective means for bereaved individuals to fill social spaces created by the loss. Findings from recent empirical investigations are consistent with these hypotheses.

Using data from a large-scale longitudinal observational cohort study, Lui et al.20 report that the death of a close friend adversely affects bereaved individuals’ physical and psychological well-being and emotional and social functioning for up to four years. Milman et al.18 report that spousal, as opposed to non-spousal, bereavement is associated with greater PGD symptoms, consistent with prior investigations. Each of these reports is consistent with our first hypothesis.

In a study examining different sources of school-based social support on grief and grief-related growth among children and adolescents bereaved by the loss of a sibling, Sharp et al.21, report that social support from friends is associated with grief-related growth regardless of age, and inversely associated with grief among adolescents. The authors also report that peer support moderates associations between parent support, grief and grief-related growth, accentuating beneficial effects of parent support, for adolescents but not children. In a web-based study of adolescents bereaved by the loss of a parent, Hirooka et al.22 report that “having fun with friends” is positively associated with posttraumatic growth. In a longitudinal cohort study of couples bereaved by perinatal loss, Tseng et al.23 report that greater marital satisfaction is associated with lower intensity of grief independent of effects of experience of infertility, number of living children and other factors on grief. Each of these reports is consistent with our second hypothesis.

Concluding Remarks

In this article, we propose a micro-sociological theory of bereavement, which provides novel conceptualizations of adaptive tasks, interpretations of symptoms and signs of grief and PGD, and insights into recent empirical investigations of bereavement and grief. It may also guide development of interventions targeting micro-sociological reorganization to fill the social void created by the loss of a close other and thereby promote grief resolution. Future research should build on prior work on social rewards24 and attachment25 and examine the features of individuals and relationships that may best satisfy social needs. It should also evaluate interventions that facilitate micro-sociological reorganization in the service of promoting more fuller adaptation to interpersonal loss.

Footnotes

No conflict of interest

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Prigerson HG, Horowitz MJ, Jacobs SC, Parkes CM, Aslan M, Goodkin K, Raphael B, Marwit SJ, Wortman C, Neimeyer RA, Bonanno GA, Block SD, Kissane D, Boelen P, Maercker A, Litz BT, Johnson JG, First MB, Maciejewski PK. Prolonged grief disorder: Psychometric validation of criteria proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11. PLoS Med. 2009; 6(8):e1000121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maciejewski PK, Maercker A, Boelen PA, Prigerson HG. “Prolonged grief disorder” and “persistent complex bereavement disorder”, but not “complicated grief”, are one and the same diagnostic entity: an analysis of data from the Yale Bereavement Study. World Psychiatry. 2016; 15(3):266–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Prigerson HG, Boelen PA, Xu J, Smith KV, Maciejewski PK. Validation of the new DSM-5-TR criteria for prolonged grief disorder and the PG-13-Revised (PG-13-R) scale. World Psychiatry. 2021; 20(1):96–106. * This report validates the new PGD diagnosis in the DSM using data from three independent epidemiological studies. The report also validates the PG-13-R scale, which measures the grief construct that grounds PGD in individual psychology.

- 4.House JS. The three faces of social psychology. Sociometry 1977; 40(2): 161–177. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Carter MJ, Fuller C. Symbols, meaning, and action: The past, present, and future of symbolic interactionism. Current Sociology Review 2016; 64(6):931–961. * This article surveys symbolic interactionist thought and research, which is focused on the construction and maintenance of meaningful micro-social interactions among individuals.

- 6.Strauss A. A Social World Perspective. Studies in Symbolic Interaction 1978; 1:119–128. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Unruh DR. The Nature of Social Worlds. The Pacific Sociological Review 1980; 23(3):271–296. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stryker S, Burke PJ. The Past, Present, and Future of an Identity Theory. Social Psychology Quarterly 2000; 63(4):284–297. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serpe RT, Stryker S. The Symbolic Interactionist Perspective and Identity Theory. In: Schwartz S, Luyckx K, Vignoles V. (eds) Handbook of Identity Theory and Research (p. 225–248). Springer, New York, NY, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall PM. Symbolic Interaction. In Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology 2007; doi: 10.1002/9781405165518.wboss310. ISBN 9781405124331. [DOI]

- 11.West RL, Turner LH. Introducing Communication Theory: Analysis and Application (6th ed). New York. ISBN9781259870323, OCLC 967775008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neimeyer RA, Prigerson HG, Davies B. Mourning and Meaning. American Behavioral Scientist 2002; 46(2):235–251. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neimeyer RA, Baldwin SA, Gillies J. Continuing Bonds and Reconstructing Meaning: Mitigating Complications in Bereavement. Death Studies 2006; 30:715–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Neimeyer RA, Klass D, Dennis MR. A Social Constructionist Account of Grief: Loss and the Narration of Meaning. Death Studies 2014; 38:485–498. * This article presents a story-telling conceptual framework for understanding personal and collective meaning-making processes in grief, including construction of narratives about the deceased individual.

- 15.Neimeyer RA. Meaning reconstruction in bereavement: Development of a research program. Death Studies 2019; 43(2): 79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellet BW, Neimeyer RA, Berman JS. Event Centrality and Bereavement Symptomatology: The Moderating Role of Meaning Made. OMEGA—Journal of Death and Dying 2018; 78(1):3–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breen LJ, Karangoda MD, Kane RT, Howting DA, Aoun SM. Differences in meanings made according to prolonged grief symptomatology. Death Studies 2018; 42(2(: 69–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milman E, Neimeyer RA, Fitzpatrick M, MacKinnon CJ, Muis KR, Cohen SR. Prolonged grief and the disruption of meaning: Establishing a mediation model. J Couns Psychol. 2019; 6(6):714–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lichtenthal WG, Catarozoli C, Masterson M, Slivjak E, Schofield E, Roberts KE, Neimeyer RA, Wiener L, Prigerson HG, Kissane DW, Li Y, Breitbart W. An open trial of meaning-centered grief therapy: Rationale and preliminary evaluation. Palliat Support Care. 2019;17(1):2–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu W-M, Forbat L, Katrina Anderson K. Death of a close friend: Short and long-term impacts on physical, psychological and social well-being. PLoS One 2019;14(4):e0214838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sharp KMH, Russell C, Keim M, Barrera M, Gilmer MJ, Foster Akard T, Compas BE, Fairclough DL, Davies B, Hogan N, Young-Saleme T, Vannatta K, Gerhardt CA. Grief and growth in bereaved siblings: Interactions between different sources of social support. Sch Psychol Q. 2018;33(3):363–371. * This study reports that different sources of school-based social support (i.e., from friends, peers, and teachers) affect grief and grief-related growth among students bereaved by deaths of siblings. It highlights that grief is a social process.

- 22.Hirooka K, Fukahori H, Akita Y, Ozawa M. Posttraumatic Growth Among Japanese Parentally Bereaved Adolescents: A Web-Based Survey. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2017; 34(5):442–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tseng YF, Cheng HR, Chen YP, Yang SF, Cheng PT. Grief reactions of couples to perinatal loss: A one-year prospective follow-up. J Clin Nurs. 2017; 26(23–24):5133–5142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Solomonov N, Bress JN, Sirey J, Gunning FM, Flückiger C, Raue PJ, Areán PA, Alexopoulos GS. Engagement in Socially and Interpersonally Rewarding Activities as a Predictor of Outcome in “Engage” Behavioral Activation Therapy for Late-Life Depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019. Jun;27(6):571–578. * This study finds that interpersonal interactions with specific friends or family members, but not engagement in social-group activities, increase behavioral activation and reduce depression. Although not a study of grief, it lends further support to our conjecture that interactions within close peer relationships are effective means to satisfy social needs.

- 25.LeRoy AS, Knee CR, Derrick JL, Fagundes CP. Implications for reward processing in differential responses to loss: Impacts on attachment hierarchy reorganization. Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2019. 23(4), 391–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]