Abstract

Background Prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is a promising protein for breast cancer patients. It has not only been detected in prostate cancer but is also expressed by tumor cells and the endothelial cells of tumor vessels in breast cancer patients. PSMA plays a role in tumor progression and tumor angiogenesis. For this reason, a number of diagnostic and therapeutic methods to target PSMA have been developed.

Method This paper provides a general structured overview of PSMA and its oncogenic potential, with a special focus on its role in breast cancer. This narrative review is based on a selective literature search carried out in PubMed and the library of Freiburg University Clinical Center. The following key words were used for the search: “PSMA”, “PSMA and breast cancer”, “PSMA PET/CT”, “PSMA tumor progression”. Relevant articles were explicitly read through, processed, and summarized.

Conclusion PSMA could be a new diagnostic and therapeutic alternative, particularly for triple-negative breast cancer. It appears to be a potential predictive and prognostic marker.

Key words: PSMA, breast cancer, radioligand therapy, immunohistochemistry, PET/CT

Abbreviations

- CT

computed tomography

- ER

estrogen receptor

- FOLH1

folate hydrolase 1

- FDG

fluorodeoxyglucose

- GCPI

glutamate carboxypeptidase II

- HR

hormone receptor

- HUVEC

human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- n. s.

not significant

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PR

progesterone receptor

- PSMA

prostate specific membrane antigen

- TNBC

triple-negative breast cancer

- SUV

standardized uptake value

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

Introduction

Prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is a new and significant marker for breast cancer patients. This protein has not just been detected in prostate cancer but is also expressed by breast cancer tumor cells and the endothelial cells of tumor vessels. PSMA plays a role in tumor progression and tumor angiogenesis. This has led to the development of promising diagnostic and therapeutic procedures targeting PSMA.

PSMA could be a new theranostic alternative in triple-negative breast cancer. This article provides an overview of the current data on PSMA in breast cancer and the currently available diagnostic and therapeutic PSMA-targeting options.

General Information on PSMA

Prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) is a type II transmembrane protein also known as glutamate carboxypeptidase II (GCPII), folate hydrolase I (FOLH1) or N-acetyl-L-aspartyl-L-glutamate peptidase I (NAALADase I) 1 . PSMA has a three-part structure which consists of 19 intracellular, 24 transmembrane and 707 extracellular amino acids 2 . The PSMA gene is located on the short arm of chromosome 11 3 . It was first localized in a LNCaP cell line 4 . The LNCaP cell line was originally established using a metastatic lymph node from a patient with metastatic prostate cancer 4 .

PSMA performs different enzymatic activities. As a folate hydrolase it breaks down polyglutamate folate chains 5 . In the central nervous system, it corresponds to NALAADase I 6 . This catabolizes external N-acetyl-L-aspartyl-L-glutamate (NAAG) into N-acetyl-aspartate (NAA) and glutamate 7 . Inhibition of NALAADase reduces the amount of intracerebrally available glutamate, which has been shown to have a neuroprotective effect in preclinical models, for example in neuropathic pain or stroke 8 .

PSMA is expressed in both benign and malignant prostate tissue 8 . In prostate cancer, elevated PSMA expression is associated with negative prognostic factors such as a higher tumor stage, a higher Gleason score and higher hormone refractoriness of the tumor 9 , 10 . But it is also expressed by other organs such as the kidneys, bladder or salivary glands 11 , 12 , 13 . PSMA is also found in different tumor entities on tumor cells, such as kidney, bladder and ovarian cancers, and in tumor-specific vessels and tumor neovasculature, such as non-small cell lung cancer 11 , 14 .

Current Data on PSMA Expression in Breast Cancer

Healthy glandular breast tissue appears to express PSMA on its epithelial cells but not on its vascular endothelium 11 , 15 , 16 . An overview of the current data is shown in Table 1 .

Table 1 The expression of prostate-specific membrane antigen in breast cancer and healthy glandular breast tissue – detected with immunohistochemistry.

| Author, year of publication [reference] | n | Metastases (n) | PSMA expression in vessels n (%) |

PSMA expression in tumor cells n (%) |

PSMA expression in healthy glandular breast tissue n (%) |

PSMAs expression in relation to grading | PSMA expression in relation to hormone receptor status | PSMA expression in relation to histology | Overall survival in relation to PSMA expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ER: estrogen receptor; PR: progesterone receptor; HR: hormone receptor; TNBC: triple-negative breast cancer; n. s.: not significant | |||||||||

| Tolkach, 2018 17 | 315 | – | 189 (60) | 10 (3) | – | p = 0.002 | HR negative: p = 1.9 × 10E-6 TNBC: p = 0.006 |

p = 0.01 | n. s. |

| Kasoha, 2017 16 | 72 | 10 | 31 (46) | 50 (72) | 26 (67) | p = 0.004 | n. s. | p = 0.026 | n. s. |

| Wernicke, 2014 18 | 92 | 14 | 68 (74) | None | 0 | p < 0.0001 | ER negative: p < 0.0001 PR negative: p = 0.03 |

n. s. | p = 0.05 |

| Kinoshita, 2006 11 | 5 | – | – | 1 (20) | 6 (100) | – | – | – | – |

| Ross, 2004 19 | 10 | – | 7 (70) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Chang, 1999 15 | 6 | – | 5 (83) | 0 | 8 (100) | – | – | – | – |

The current data on PSMA expression in breast cancer tumor cells is inconsistent. Only tumor neovasculature appears to express PSMA relatively constantly. PSMA expression does not just occur in the tumor cells of the primary tumor but also in distant metastases. This means that PSMA could be suitable target structure for antiangiogenic therapies.

Several studies have already investigated the expression of PSMA in breast cancer. Three of these studies are of particular interest: the studies by Kasoha et al., Tolkach et al. and Wernicke et al. 16 , 17 , 18 . These studies investigated PSMA expression in the tumors of 72, 315 and 92 breast cancer patients, respectively.

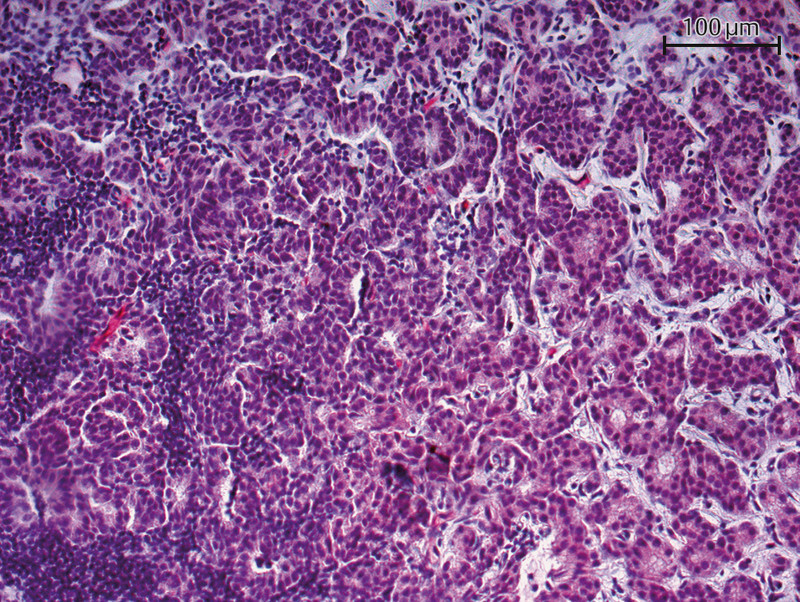

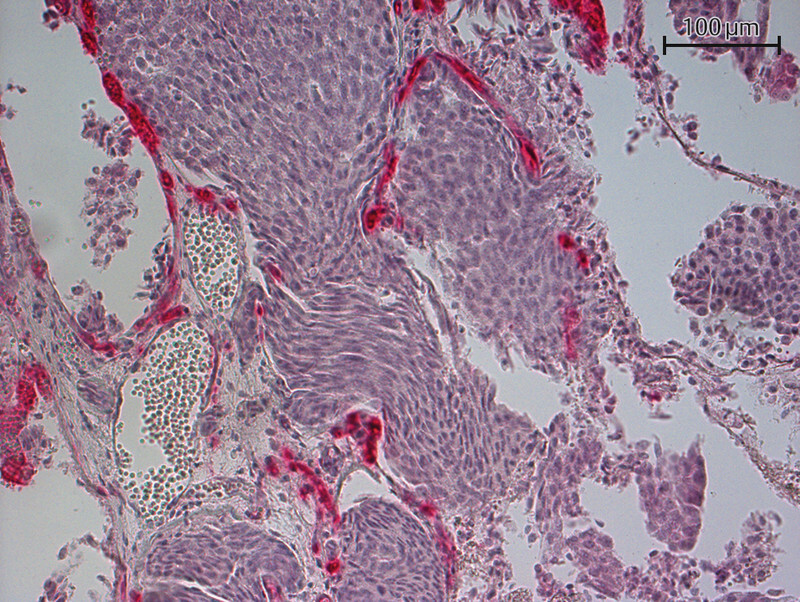

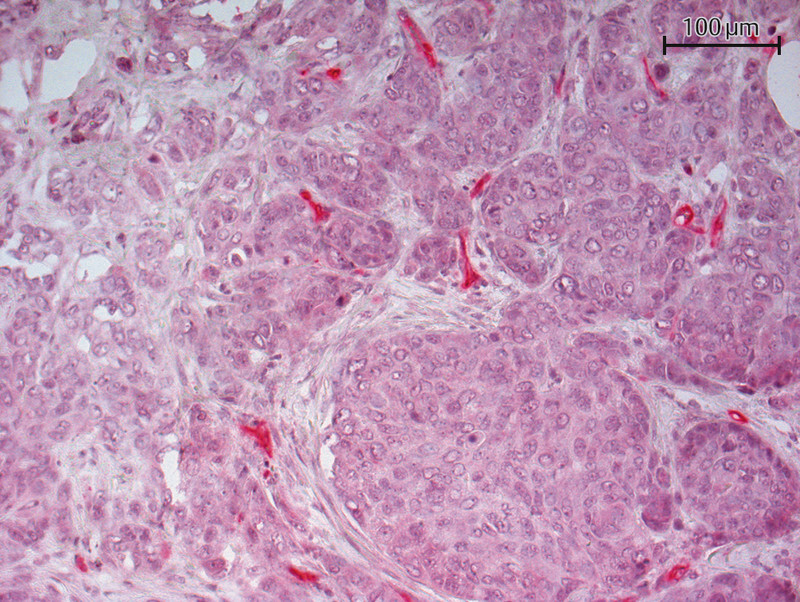

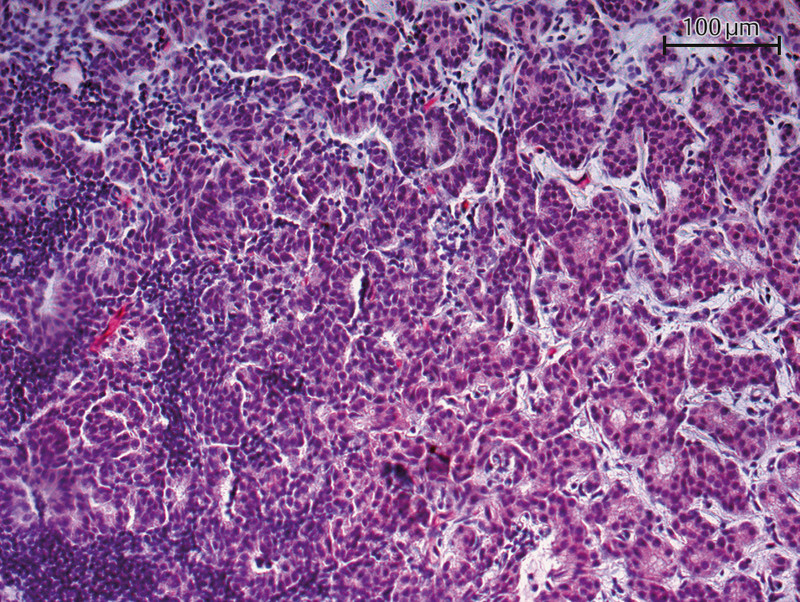

Tolkach et al. only reported PSMA expression in tumor cells in 10 (3%) out of 315 investigated samples. However, tumor vessels in 60% (n = 189) of these cases were PSMA-positive 17 . Immunohistochemical examination detected cytoplasmic PSMA staining. Wernicke et al. found PSMA-positive vessels in 90 out of 92 investigated breast cancer patients. In the two remaining cases, the healthy breast tissue vasculature was also positive for PSMA. But no PSMA expression was detected in healthy glandular breast tissue or the tumor cells 18 . In the study by Kasoha et al., tumor cells were positive for PSMA in 72% of cases (50/70) and tumor-associated neovasculature was positive for PSMA in 46% (31/68) of cases. Figs. 1 to 3 show examples of the immunohistochemical detection of PSMA expression in tumor cells and tumor neovasculature.

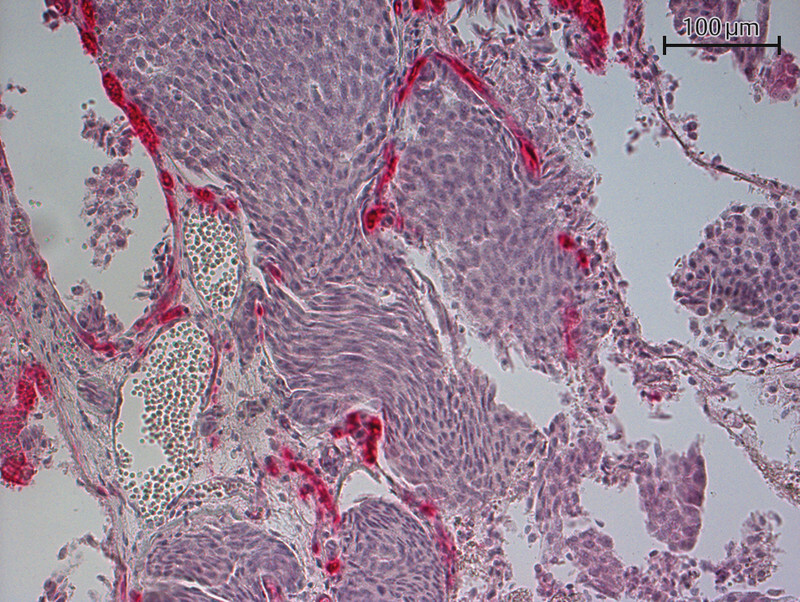

Fig. 1.

Immunohistochemical staining of a primary tumor specimen with a PSMA antibody (20-fold magnification) – PSMA detected in tumor vessels.

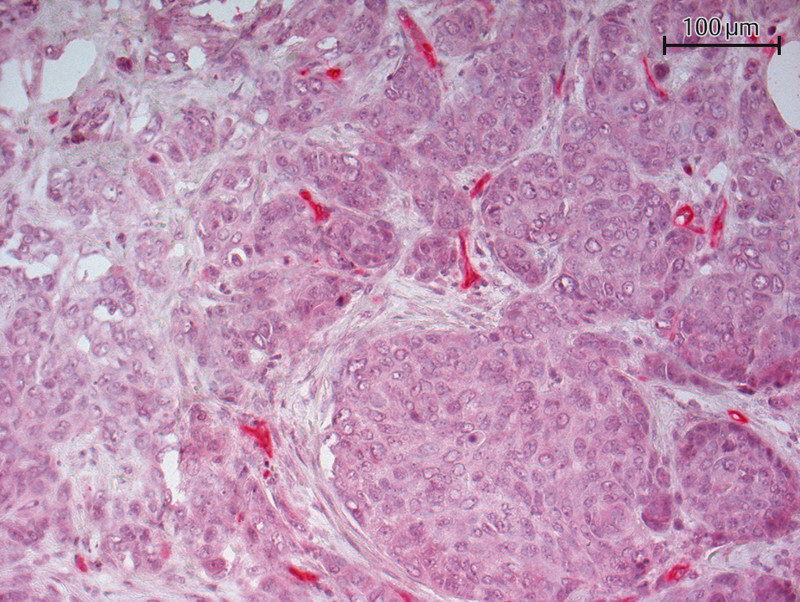

Fig. 3.

Immunohistochemical staining of a brain metastasis with a PSMA antibody (20-fold magnification) – PSMA detected.

Fig. 2.

Immunohistochemical staining of a lymph node metastasis with a PSMA antibody (20-fold magnification) – PSMA expression detected in tumor vessels.

Other studies have also examined PSMA expression in breast cancer. Chang et al. used five different PSMA antibodies and found that PSMA was expressed both in the membrane and intracytoplasmically in the tumor neovasculature of five of the six investigated cases. Four of these cases were invasive ductal breast cancers 15 . The tumor cells in this study were PSMA-negative. All eight stained healthy breast tissue specimens, however, showed PSMA expression on the epithelium. The vasculature in the healthy tissue was PSMA-negative 15 . In another study by Kinoshita et al., the staining reaction to the PSMA antibody in the six investigated cases with normal glandular breast tissue was moderate. One of the five specimens of invasive ductal breast cancers showed weak PSMA immunoreactivity 11 . Ross et al. detected PSMA expression in the neovasculature of invasive ductal breast cancers in seven of 10 cases 19 . All of the eight phyllodes tumors of the breast investigated by Mhawech-Fauceglia et al. were PSMA-negative 20 .

PSMA is not just expressed by primary tumors but also by distant metastases 16 , 18 , 21 . Kasoha et al. investigated 12 distant metastases (bone and brain metastases); when they compared the primary tumors with the distant metastases, they found a significantly increased PSMA expression in the tumor-associated neovasculature of brain metastases (p = 0.049). But this elevated PSMA expression was not detected in tumor cells 16 . Wernicke et al. investigated 14 brain metastases using immunohistochemical staining; in all cases, PSMA was expressed in the tumor-associated neovasculature. In the 10 paired cases, the PSMA expression in metastases was identical to the PSMA expression in the corresponding primary tumor. Nomura et al. found that PSMA expression in tumor-associated neovasculature was three times higher compared to healthy brain tissue in five investigated brain metastases (p = 0.007). However, the extent of PSMA expression in the metastases and the primary tumor differed in the four paired cases: PSMA expression was lower in the brain metastases of three of the patients compared to PSMA expression in breast tumors in the same patients.

A comparison of PSMA expression with prognostic and predictive factors for breast cancer showed that increased expression was significantly associated with a higher tumor grade 16 , 17 , 18 . Wernicke et al. found PSMA expression was significantly higher depending on tumor size 18 , and Tolkach et al. reported significantly increased PSMA expression in invasive ductal breast cancer (compared to invasive lobular breast cancer) and was also associated with higher T, N or UICC stages 17 . Kasoha et al. confirmed this finding with regard to histology, with invasive ductal breast cancers expressing higher levels of PSMA than breast cancers with a different histology 16 . However, Wernicke et al. were unable to find any association between histology and PSMA status 18 .

Tolkach et al. detected a higher expression of PSMA in tumor-associated microvessels, particularly in tumors that were not hormone receptor-positive or HER2/neu-positive or were triple-negative (p = 1.9e-06 and p = 0.006). PSMA expression in triple-negative cancers was 4.5 times higher than in other tumors. The study by Tolkach et al. investigated tissue samples from 47 (14.9%) hormone receptor-negative and 33 (10.5%) triple-negative tumors 17 . Wernicke et al. also found a higher number of PSMA-positive vessels in estrogen receptor-negative (p < 0.0001) and progesterone receptor-negative (p = 0.03) tumors. They investigated 12 (11%) tissue samples from estrogen receptor-negative tumors and 24 specimens (24%) from progesterone receptor-negative tumors 18 . However, Kasoha et al. were unable to establish a significant association between hormone receptor status and simultaneous expression of PSMA in tumor cells and tumor-associated neovasculature 16 .

As regards patient survival, only Wernicke et al. reported a lower 10-year survival rate in cases with elevated PSMA expression 18 .

The different staining results could be explained by the different methods used for staining and by the different evaluation methods used, which included different primary antibodies to bind several epitopes of PSMA, differences in the dilution of the primary antibody, and different antigen-retrieval methods. There were also significant differences in the ways studies quantified PSMA-positive vessels.

In summary, it appears that increased PSMA expression is associated with higher tumor grades and higher UICC stages. Particularly triple-negative and invasive ductal breast cancer have been found to express PSMA in the endothelium of tumor-associated vasculature. PSMA expression in tumor-associated vasculature is lower in invasive lobular breast cancer or breast cancers with a different histology. In one patient population, an association was detected between PSMA expression in endothelial vascular cells and poorer overall survival 18 .

The Role of PSMA in Tumor Progression

The precise function of PSMA has still not been fully elucidated. It is a protein that appears to contribute to tumor progression in a number of ways. Several hypotheses have been proposed:

PSMA contributes to tumor progression due to its function as a folate hydrolase

PSMA does not just function as a folate hydrolase in the small intestine but also in prostate cancer cells 22 . Yao et al. have already demonstrated that prostate cancer cells which expressed PSMA in vitro and in animal experiments have a greater invasive potential 23 . They were also able to show that PSMA enables the uptake of monoglutamate folate after hydrolysis of polyglutamate chains. It appears that PSMA does not just breakdown polyglutamate folate chains in the luminal cells of the small intestine but also in prostate cancer cells. This function may be responsible for the increased invasiveness and poorer prognosis of PSMA-expressing prostate cancers, as this increases cell folate uptake, an essential component in nucleic acid synthesis 23 , 24 .

In contrast, Gordon et al. suggested that PSMA-induced folate uptake is essential for the regeneration of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), which, in turn, is indispensable for angiogenesis. The enzymatic function of PSMA as a folate hydrolase may therefore not just lead to an increase in local folate levels but also encourage eNOS regeneration through the increase in available folate. PSMA may support the angiogenesis of new blood vessels through this signaling pathway 25 .

PSMA contributes to carcinogenesis

Bradbury et al. were able to show in an in-vitro model that breast cancer cell lines in which the PSMA gene was downregulated had a lower cell proliferation, cell adhesion, and cell migration capacity 26 . The proposed explanation for this was that inactivation of the MDM2 gene leads to a reduction in PSMA expression and vice versa 26 . MDM2 is responsible, among other things, for the malignant degeneration of cells by inhibiting the p53 tumor suppressor protein 27 . This means that lower PSMA expression could be associated with lower MDM2 expression.

Caromile et al. formulated the hypothesis that PSMA may interrupt signaling between β1 integrin and IGF-1R through its association with RACK1, which could lead to an increased proliferation of tumor cells 28 .

PSMA leads to neoangiogenesis in tumors

The study group of Liu et al. developed an in-vitro model to show that the tumor microenvironment initiates vascular PSMA expression. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC[s]) were incubated either in media containing vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) or in tumor-conditioned media (TCM) from different tumor cell lines. HUVECs formed tube-like vesicles in the TCM of estrogen receptor-negative cell lines. These vesicles were PSMA-positive. The vesicles formed in the media containing estrogen receptor-positive cell lines were incomplete. It appears that estrogen receptor-negative cell lines secrete factors which promote PSMA expression and tumor angiogenesis 29 . These results were also confirmed by Nguyen et al. in cell lines from other tumor entities 30 .

Another study was able to show that PSMA modulates the laminin-specific β1 integrin function. PSMA is responsible for the initial ligand binding of β1 integrin and participates in a regulatory loop involving β1 integrin and PAK1, which in turn supports cell invasion in angiogenesis 31 .

PSMA in triple-negative breast cancer

PSMA appears to be playing a particularly interesting role in triple-negative breast cancers. Wernicke et al. and Tolkach et al. have already reported increased PSMA expression in these cancers 17 , 18 .

Morgenroth et al. also investigated this topic. They not only confirmed PSMA expression in a triple-negative breast cancer cell line but also found an increased angiogenic potential. To do this, HUVECs were incubated in tumor-conditioned media from an estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cell line (MCF-7) and from a triple-negative breast cancer cell line (MDA-MB231) and the formation of tube-like structures was observed. It was found that the HUVECs which were exposed to the TCM of MDA-MB231 cell lines developed tube-like formations. Moreover, the endothelial cells were found to be positive for PSMA on flow cytometry. It appears that exposure of HUVECs to TCM from the triple-negative cell line induced PSMA expression. On imaging ( 68 Ga positron-emission tomography [PET/CT]), PSMA expression was only detected in the triple-negative cell line from xenografts of these murine cell lines. The authors not only characterized the PSMA expression of HUVECs but also carried out PSMA-targeted radioligand therapy (using 177 Lu-PSMA-617) in the tubular endothelial structures. They were able to show that the antiangiogenic potential of this therapy was higher in the tube-like formations which had been conditioned in TCM from triple-negative tumors (the apoptosis rate was 48.15% compared to 15% in those exposed to TCM from MCF-7). Morgenroth et al. proposed an interesting hypothesis, whereby PSMA expression in triple-negative breast cancer may contribute to this cancerʼs increased resistance to therapy. Triple-negative breast cancer can increase the amount of intracellular glutathione which acts as an antioxidant against oxygen radicals. Glutathione is a tripeptide of glycine, cysteine and glutamate. The NALAADase activity of PSMA releases glutamate. This can then be used by the cells of triple-negative breast cancers to form glutathione, making it more resistant to oxidative stress 32 . In the above-mentioned study, Liu et al. also observed the formation of (PSMA-positive) vasculature in the estrogen receptor-negative cell line but not in the estrogen receptor-positive cell line 33 .

In conclusion, PSMA contributes to tumor progression and neoangiogenesis in many ways. It appears to play a particularly important role in triple-negative breast cancer.

This makes PSMA a promising protein which could serve as a new target structure for the diagnosis and/or therapy of triple-negative breast cancers.

PSMA in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Breast Cancer

The standard immunohistochemical diagnosis of breast cancer includes, among other things, determining the receptor expression of estrogen, progesterone and HER2/neu receptors 34 . In the metastatic setting, the receptors on the metastasis may differ from those of the primary tumor, a change that is known as a receptor switch 35 . HER2/neu-targeted therapy could be reserved for such patient populations, and new molecules such as the Affibody ® have been developed for this purpose. Targeted binding of this molecule to her2/neu followed by PET/CT imaging is a non-invasive method to determine patientsʼ HER2/neu status (which does not require a biopsy of the metastasis) 36 .

Two important insights can be concluded from this: firstly, carrying out PET/CT to evaluate patientsʼ response to targeted therapy for breast cancer is the way forward; secondly, it is important to precisely determine the expression of a protein in breast cancer metastases. The data on PSMA expression in breast cancer metastases is not sufficient to confidently conclude that histopathological determination of PSMA in the primary tumor means that it is expressed in the corresponding metastases. A further characterization of PSMA expression in breast cancer metastases based on both immunohistochemistry and imaging is therefore necessary.

To date, PSMA-PET/CT has only been used in a few patients with breast cancer. Overall, however, the results have been promising 37 . Table 2 provides an overview of the currently available data.

Table 2 Detection of prostate-specific membrane antigen in breast cancer using PET/CT.

| Author, year of publication [reference] | N | PSMA expression detetected | Population | Confirmation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR: progesterone receptor | ||||

| Passah, 2018 38 | 1 | present | 33-year-old patient with metastatic TNBC | 18 F-FDG-PET/CT |

| Sathekge, 2015 39 | 1 | present | 33-year-old patient with metastatic breast cancer | clinical, 18 F-FDG-PET/CT |

| Sathekge, 2017 40 | 19 | overall detection rate: 84% | patients with both PR-positive and PR-negative breast cancer (primary or recurrent or metastatic disease) | clinical, histology, 18 F-FDG-PET/CT (n = 7) |

| Kasoha, 2017 16 | 1 | 1 | 79-year-old patient with breast cancer and bone metastasis | clinical, histology |

| Medina-Ornelas, 2020 41 | 21 | 76% | patients with primary metastatic disease who did not have prior therapy and had different hormone receptor and HER2/neu receptor statuses | 18 F-FDG-PET/CT |

Passah et al. carried out PSMA ligand PET/CT in a 33-year-old patient with triple-negative breast cancer and detected liver metastases and a thoracic wall recurrence after surgical therapy, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. The findings were confirmed by imaging using [ 18 F] fluorodeoxyglucose-(FDG-) PET/CT 38 .

Based on the case report of Passah et al., this diagnostic workup was repeated in 2017 in a larger patient population (n = 19). The results of the study were very promising. Using PSMA ligand PET/CT, Sathekge et al. were able to detect PSMA positivity in 84% (n = 81) of previously identified tumor lesions. Seven patients had previously been examined using FDG PET/CT. Overall, 13 primary tumors and/or local recurrences as well as 15 lesions (affected lymph nodes) and 53 metastatic lesions were identified with PSMA PET/CT. The tracer uptake in distant metastases was significantly higher compared to the respective primary tumor. As regards hormone receptor expression, the study only investigated patients for progesterone receptor status. A total of six patients had progesterone receptor-positive and seven patients had progesterone receptor-negative breast cancer. The receptor status of six patients was unknown. PSMA-specific imaging was able to identify 31 positive lesions in both the progesterone receptor-positive and the progesterone receptor-negative groups. No significant differences were found with regard to the mean standardized uptake value (SUV). A comparison of PSMA PET/CT with FDG-PET/CT showed a discrepancy of seven lesions (six lesions were PSMA-negative, one lesion which was found on PSMA PET/CT imaging was not visible with FDG PET/CT). Moreover, a significant association between the SUVs of both types of examination was found (p = 0.015) 39 , 40 .

Kasoha et al. also carried out PSMA ligand PET/CT in a patient with known PSMA-positive bone metastases of breast cancer. The bone metastases were PSMA-positive on PSMA-specific imaging 16 .

In 2020, Medina-Ornelas et al. published their results in a study comparing FDG PET/CTs and PSMA ligand PET/CTs in patients with primary metastatic breast cancer who had not undergone prior therapy. Examinations were carried out in 21 patients. Four of them had luminal A tumors, four had luminal B and HER2/neu-positive tumors, two had luminal B and HER2/neu-negative tumors, six had non-luminal HER2-positive tumors and five had triple-negative cancer. The detection rates of FDG PET/CT and PSMA ligand were compared. Overall, the detection rate using PSMA-specific imaging was lower than with FDG PET/CT in all patients. In patients with triple-negative or HER2-positive breast cancer, every lesion visible on FDG PET/CT was also positive on PSMA imaging. This was also the case for bone metastases, irrespective of their histology. In summary, in-vivo PSMA positivity was detected in 76% of cases, with a sensitivity of 84% and a specificity of 91.8% 41 .

Detection of metastasis using imaging is not just very important for diagnostic reasons. The images obtained can also provide value information about patientsʼ potential response to PSMA-targeted therapy. Patients with PSMA-positive lesions on imaging could benefit from PSMA-targeted therapy.

The conclusion drawn from these studies is that imaging to detect PSMA expression must be carried out prior to starting PSMA-targeted therapy. Primary tumors can be evaluated with immunohistochemistry. However, when attempting to detect PSMA expression in metastases, in many cases no tissue is available for analysis. The current results of studies which compared the expression of PSMA in primary tumors and their corresponding metastases show that it is not possible to infer that the PSMA status of the primary tumor is an indication of the potential PSMA expression in distant metastases. The detection of PSMA positivity in a primary tumor or metastasis using PSMA PET/CT could plug this diagnostic gap. Using PSMA PET/CT would also avoid the side effects of biopsies undertaken for histological assessment of a lesion, such as injection canal metastasis, infection, or hematoma. This type of imaging could also be used for therapeutic monitoring.

Other Alternatives to PSMA Diagnosis

The PSMA status of a breast cancer lesion can also be evaluated based on an analysis of circulating tumor cells (CTCs). Out of a total of 41 patients with triple-negative breast cancer, PSMA expression in CTCs were identified in 15% (6/41) of cases. Patients with PSMA-positive CTCs before undergoing chemotherapy were less likely to achieve pathological complete remission after chemotherapy. Recurrence occurred earlier if PSMA expression was detected (p = 0.0039) and overall survival rates were lower (p = 0.0059) 42 . Evaluation of the PSMA status of CTCs could help to predict the response to PSMA-targeted therapy in triple-negative breast cancer. The analysis of circulating tumor cells is a minimally invasive method which could offer an alternative to biopsies of metastases. As regards her2 status, predicting her2 overexpression in metastases based on the analysis of CTCs appears to be possible 43 . Overall, the expression patterns of CTCs were found to be more similar to those of metastases than to those of the primary tumors 43 , 44 , 45 . CTCs could therefore be a good alternative method for a non-invasive evaluation of PSMA expression in metastatic breast cancer. The PSMA status of metastases could also be evaluated. This approach could offer an alternative to PET/CT if it becomes possible to achieve a similarly high quality of imaging. However, no studies on this have yet been carried out. This would be interesting, not just from a diagnostic point of view, as it could also provide valuable information about the potential response to PSMA-targeted therapy.

PSMA-targeted Therapies

PSMA ligands are internalized after binding 28 , making this protein a suitable target structure for treatment with radionuclides.

The benefits of PSMA-targeted radioligand therapy for prostate cancer have already been demonstrated 46 , 47 . In a study by Yadav et al., 90 patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer were treated with PSMA radioligand therapy. PSA levels decreased in 56 (62.2%) patients. 19 (27.5%) patients had partial remission, 30 (43.5%) patients had stable disease, and 20 (29%) experienced disease progression.

Prostate cancer examinations have shown that even after prior radioligand therapy, repeating this therapy can still elicit a response in cases of progression after an initial response to therapy 48 .

One limitation of PSMA-targeted radioligand therapy is the impact of heterogeneous PSMA expression, which can lead to reduced uptake of the ligand, thereby reducing the efficacy of treatment 49 . PSMA radioligand therapy is therefore no longer used in cases with heterogeneous PSMA expression. As PET/CT should be carried out before administering therapy, the nuclear medicine decision on whether or not to administer radioligand therapy can be taken before the start of therapy.

PSMA radioligand therapy has few or moderate side effects. Xerostomia and anemia are the most clinically relevant side effects. Other potential side effects include leukocytopenia and thrombocytopenia as well as elevated liver function tests and an increase in renal retention parameters such as fatigue, nausea, vomiting or diarrhea 46 , 47 , 48 . However, PSMA radioligand therapy is generally tolerated well. Grade 3 and 4 toxicities are very rare 48 .

PSMA-targeted radioligand therapy is not the only therapy currently attracting a lot of interest. Other therapeutic approaches which make use of the enzyme functions of the protein have already been developed.

The folate HBPE(CT20p) was developed for this therapeutic approach. The assumption underpinning the development of this nanocarrier is that the folate hydrolase PSMA does not just convert folate polyglutamates, it also enables folate uptake by malignant cells. This was confirmed by the study of Flores et al. They were not just able to show that folate-conjugated therapeutics are selectively taken up by PSMA-positive cells but also that they induce considerable changes in cell morphology 50 . This method could be particularly important for breast cancer patients. The therapeutic peptide used (CT20p) leads to morphological changes of the cytoskeleton, impairs mitochondrial movement and actin polymerization. It has already been investigated in breast cancer models and was found to reduce cancer cell invasiveness 50 .

Radio-guided surgery is a new therapeutic approach currently being developed further to treat prostate cancer. Up to now, it was used as salvage surgery to treat patients who still have PSMA-positive lesions on 68 Ga PSMA PET/CT imaging after radical prostatectomy. It uses a radioactive substance which specifically binds to PSMA. The studies carried out to date have shown promising results, with accurate resection of PSMA-positive lesions already detected with PET/CT and complete biochemical response achieved in 66% of patients treated who received this treatment 51 . A postoperative comparison between activity measured with a gamma probe and histopathological results showed that metastasis was correctly identified in most cases 52 .

This therapeutic approach is particularly interesting for patients with prostate cancer, as affected lymph nodes may also be present outside the standard resection area of extended pelvic lymphadenectomy. In addition, lymphatic flow may change after primary (surgical) therapy, with metastases developing in unusual locations 51 . Whether this method can be used to treat breast cancer patients is still not clear.

Some case reports have also described the use of PSMA-targeted therapy in patients with breast cancer. Tolkach et al., for example, used PSMA radioligand therapy to treat a 38-year-old patient with triple-negative breast cancer. The treatment was well tolerated but progression recurred after four weeks. The patient did not receive further therapy cycles because of renewed progression 17 . Von Hoff et al. tested docetaxel-encapsulated nanoparticle BIND-014 therapy where docetaxel-encapsulated nanoparticles target PSMA in a cohort which included a patient with breast cancer. The 39-year-old patient showed a partial response to this therapy 53 .

Conclusion

In summary, PSMA is a promising protein, which is not just expressed in the primary tumor but also in the distant metastases of breast cancer. Its expression appears to be limited to tumor-associated neovasculature. PSMA contributes to tumor progression and neoangiogenesis on many levels. This is particularly the case in triple-negative breast cancer. PSMA-specific diagnosis and therapy is already well established for prostate cancer. Although only a few cases have investigated the benefit of this approach to treat breast cancer patients, the results have been promising. Continued research in this area could establish a new alternative for diagnosis and treatment, particularly for patients with triple-negative breast cancer.

Acknowledgements

IMM-PACT Programme for Clinician Scientists, Internal Medicine II, Medical Center – University of Freiburg and Medical Faculty, supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – 413517907.

Danksagung

IMM-PACT-Programm für Clinician Scientists, Innere Medizin II, Medizinisches Zentrum – Universität Freiburg und Medizinische Fakultät, Universität Freiburg, gefördert durch die Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) – 413517907.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest./Die Autorinnen/Autoren geben an, dass kein Interessenkonflikt besteht.

References/Literatur

- 1.OʼKeefe D S, Bacich D J, Heston W DW. Totowa: Humana Press; 2001. Prostate Cancer: Biology, Genetics and the new Therapeutics. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bacich D J, Pinto J T, Tong W P. Cloning, expression, genomic localization, and enzymatic activities of the mouse homolog of prostate-specific membrane antigen/NAALADase/folate hydrolase. Mamm Genome. 2001;12:117–123. doi: 10.1007/s003350010240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.OʼKeefe D S, Su S L, Bacich D J. Mapping, genomic organization and promoter analysis of the human prostate-specific membrane antigen gene. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1443:113–127. doi: 10.1016/S0167-4781(98)00200-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horoszewicz J S, Leong S S, Chu T M. The LNCaP cell line-a new model for studies on human prostatic carcinoma. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1980;37:115–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Devlin A M, Ling E, Peerson J M. Glutamate carboxypeptidase II: a polymorphism associated with lower levels of serum folate and hyperhomocysteinemia. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2837–2844. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.19.2837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter R E, Feldman A R, Coyle J T. Prostate-specific membrane antigen is a hydrolase with substrate and pharmacologic characteristics of a neuropeptidase. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1996;93:749–753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stauch Slusher B, Tsai G, Yoo G. Immunocytochemical localization of the N-acetyl-aspartyl-glutamate (NAAG) hydrolyzing enzyme N-acetylated α-linked acidic dipeptidase (NAALADase) J Comp Neurol. 1992;315:217–229. doi: 10.1002/cne.903150208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mesters J R, Barinka C, Li W. Structure of glutamate carboxypeptidase II, a drug target in neuronal damage and prostate cancer. EMBO J. 2006;25:1375–1384. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rajasekaran A K, Anilkumar G, Christiansen J J. Is prostate-specific membrane antigen a multifunctional protein? Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2005;288:975–981. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00506.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minner S, Wittmer C, Graefen M. High level PSMA expression is associated with early PSA recurrence in surgically treated prostate cancer. Prostate. 2011;71:281–288. doi: 10.1002/pros.21241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kinoshita Y, Kuratsukuri K, Landas S. Expression of Prostate-Specific membrane antigen in normal and malignant human tissues. World J Surg. 2006;30:628–636. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0544-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silver D A, Pellicer I, Fair W R. Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen Expression in Normal and Malignant Human Tissues. Clin Cancer Res. 1997;3:81–85. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0544-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wright G L, Haley C, Beckett M. Expression of Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen in normal, benign, and malignant prostate tissues. Urol Oncol Semin Orig Investig. 1995;1:18–28. doi: 10.1016/1078-1439(95)00002-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang H, Wang L, Song W. Expression of Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen in Lung Cancer Cells and Tumor Neovasculature Endothelial Cells and Its Clinical Significance. PLoS One. 2015 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chang S S, Reuter V E, Heston W D. Five different anti-prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) antibodies confirm PSMA expression in tumor-associated neovasculature. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3192–3198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kasoha M, Unger C, Solomayer E. Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) expression in breast cancer and its metastases. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2017;34:479–490. doi: 10.1007/s10585-018-9878-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tolkach Y, Gevensleben H, Bundschuh R. Prostate-specific membrane antigen in breast cancer: a comprehensive evaluation of expression and a case report of radionuclide therapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;169:447–455. doi: 10.1007/s10549-018-4717-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wernicke A G, Varma S, Greenwood E A. Prostate-specific membrane antigen expression in tumor-associated vasculature of breast cancers. Apmis. 2014;122:482–489. doi: 10.1111/apm.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross J S, Schenkein D, Webb I. Expression of prostate specific membrane antigen in the neo-vasculature of non-prostate cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:3110. doi: 10.1200/jco.2004.22.90140.3110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mhawech-Fauceglia P, Zhang S, Terracciano L. Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) protein expression in normal and neoplastic tissues and its sensitivity and specificity in prostate adenocarcinoma: An immunohistochemical study using mutiple tumour tissue microarray technique. Histopathology. 2007;50:472–483. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2007.02635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nomura N, Pastorino S, Jiang P. Prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA) expression in primary gliomas and breast cancer brain metastases. Cancer Cell Int. 2004;14:26. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-14-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pinto J T, Suffoletto B P, Berzin T M. Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen: A Novel Folate Hydrolase in Human Prostatic Carcinoma Cells. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:1445–1451. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yao V, Berkman C E, Choi J K. Expression of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), increases cell folate uptake and proliferation and suggests a novel role for PSMA in the uptake of the non-polyglutamated folate, folic acid. Prostate. 2010;70:305–316. doi: 10.1002/pros.21065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Löffler G, Petrides P E, Heinrich P C. 8. Aufl. Berlin: Springer; 2007. Löffler/Petrides Biochemie und Pathobiochemie. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gordon I O, Tretiakova M R, Noffsinger A E. Prostate-specific membrane antigen expression in regeneration and repair. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:1421–1427. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2008.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradbury R, Jiang W ENG, Cui Y. MDM2 and PSMA Play Inhibitory Roles in Metastatic Breast Cancer Cells Through Regulation of Matrix Metalloproteinases. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:1143–1151. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-17972-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliner J, Pietenpol J, Thiagalingam S. Oncoprotein MDM2 conceals the activation domain of tumour suppressor p 53. Nature. 1993;362:857–860. doi: 10.1038/362857a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Caromile L A, Shapiro L H. PSMA redirects MAPK to PI3K-AKT signaling to promote prostate cancer progression. Mol Cell Oncol. 2017;4:1–3. doi: 10.1080/23723556.2017.1321168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu H, Rajasekaran A K, Moy P. Constitutive and Antibody-induced Internalization of Prostate-specific Membrane Antigen. Cancer Res. 1998;8:4055–4060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen D P, Xiong P L, Liu H. Induction of PSMA and Internalization of an Anti-PSMA mAb in the Vascular Compartment. Mol Cancer Res. 2016;14:1045–1053. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conway R E, Petrovic N, Zhong L. Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen Regulates Angiogenesis by Modulating Integrin Signal Transduction. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:5310–5324. doi: 10.1128/mcb.00084-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morgenroth A, Tinkir E, Vogg A TJ. Targeting of prostate-specific membrane antigen for radio-ligand therapy of triple-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2019;21:116. doi: 10.1186/s13058-019-1205-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu T, Jabbes M, Nedrow-Byers J R. Detection of prostate-specific membrane antigen on HUVECs in response to breast tumor-conditioned medium. Int J Oncol. 2011;38:1349–1355. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2011.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie Interdisziplinäre S3-Leitlinie für die Früherkennung, Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge des Mammakarzinoms 2018Accessed April 01, 2021 at:https://www.leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/leitlinien/mammakarzinom/

- 35.Zidan J, Dashkovsky I, Stayerman C. Comparison of HER-2 overexpression in primary breast cancer and metastatic sites and its effect on biological targeting therapy of metastatic disease. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:552–556. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alhuseinalkhudhur A, Lubberink M, Lindman H. Kinetic analysis of HER2-binding ABY-025 Affibody molecule using dynamic PET in patients with metastatic breast cancer. EJNMMI Res. 2020;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13550-020-0603-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bertagna F, Albano D, Cerudelli E. Radiolabelled PSMA PET/CT in breast cancer. A systematic review. Nucl Med Rev Cent East Eur. 2020;23:32–35. doi: 10.5603/NMR.2020.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Passah A, Arora S, Damle N. 68Ga-Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen PET/CT in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Clin Nucl Med. 2018;43:460–461. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000002071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sathekge M, Modiselle M, Vorster M. 68Ga-PSMA imaging of metastatic breast cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2015;42:1482–1483. doi: 10.1007/s00259-015-3066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sathekge M, Lengaga T, Modiselle M. 68Ga-PSMA-HBED-CC PET imaging in breast carcinoma patients. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2017;44:689–694. doi: 10.1007/s00259-016-3563-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Medina-Ornelas S, García-Perez F, Estrada-Lobato E. 68Ga-PSMA PET/CT in the evaluation of locally advanced and metastatic breast cancer, a single center experience. Am J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2020;10:135–142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kasimir-Bauer S, Keup C, Hoffman O. Circulating Tumor Cells Expressing the Prostate Specific Membrane Antigen (PSMA) Indicate Worse Outcome in Primary, Non-Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aktas B, Kasimir-Bauer S, Müller V. Comparison of the HER2, estrogen and progesterone receptor expression profile of primary tumor, metastases and circulating tumor cells in metastatic breast cancer patients. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2587-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Onstenk W, Sieuwerts A M, Mostert B. Molecular characteristics of circulating tumor cells resemble the liver metastasis more closely than the primary tumor in metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:59058–59069. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lianidou E, Pantel K. Liquid biopsies. Genes, Chromosomes and Cancer. 2019;58:219–232. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yadav M P, Ballal S, Bal C. Efficacy and Safety of 177Lu-PSMA-617 Radioligand Therapy in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Patients. Clin Nucl Med. 2020;45:19–31. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000002833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rahbar K, Ahmadzaehfar H, Kratochwil C. German Multicenter Study Investigating 177 Lu-PSMA-617 Radioligand Therapy in Advanced Prostate Cancer Patients . J Nucl Med. 2017;58:85–90. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.183194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Violet J, Sandhu A, Iravani A. Long-Term Follow-up and Outcomes of Retreatment in an Expanded 50-Patient Single-Center Phase II Prospective Trial of 177Lu-PSMA-617 Theranostics in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. J Nucl Med. 2020;61:857–865. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.119.236414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Current K, Meyer C, Magyar C. Investigating PSMA-Targeted Radioligand Therapy Efficacy as a Function of Cellular PSMA Levels and Intratumoral PSMA Heterogeneity. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:2946–2955. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-19-1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Flores O, Santra S, Kaittanis C. PSMA-targeted theranostic nanocarrier for prostate cancer. Theranostics. 2017;7:2477–2494. doi: 10.7150/thno.18879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maurer T, Graefen M, van der Poel H. Prostate-Specific Membrane Antigen – Guided Surgery. J Nuclear Med. 2020;61:6–13. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.119.232330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rauscher I, Düwel C, Wirtz M. Value of 111 In-prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA)-radioguided surgery for salvage lymphadenectomy in recurrent prostate cancer: correlation with histopathology and clinical follow-up . BJU Int. 2017;120:40–47. doi: 10.1111/bju.13713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Von Hoff D, Mita M M, Ramanathan R K. Phase I Study of PSMA-Targeted Docetaxel-Containing Nanoparticle BIND-014 in Patients with Advanced Solid Tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:3157–3164. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]