Abstract

Background

Cocaine dependence is a public health problem characterised by recidivism and a host of medical and psychosocial complications. Cocaine dependence remains a disorder for which no pharmacological treatment of proven efficacy exists.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and the acceptability of antipsychotic medications for cocaine dependence.

Search methods

This review is an update of a previous Cochrane review published in 2007. We searched up to 15 July 2015 in Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group Specialised Register (searched in CRSLive); the Cochrane Library (including the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)); PubMed; EMBASE; CINAHL and Web of Science. All searches included non‐English language literature.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials with focus on the use of any antipsychotic medication for the treatment of cocaine dependence.

Data collection and analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane.

Main results

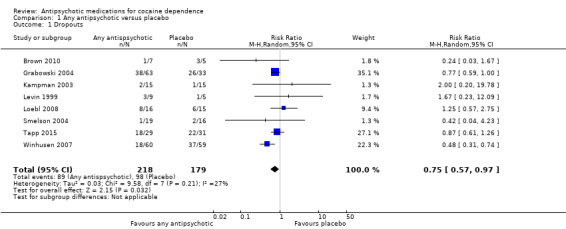

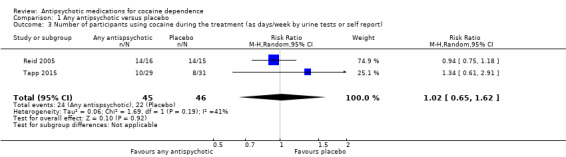

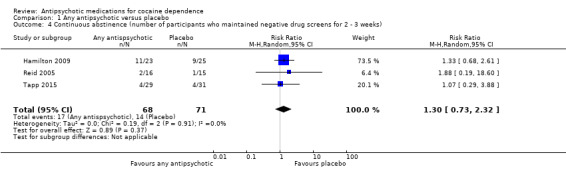

We included 14 studies (719 participants). The antipsychotic drugs studied were risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, lamotrigine, aripiprazol, haloperidol and reserpine. Comparing any antipsychotic drugs versus placebo, we found that antipsychotics reduced dropout: eight studies, 397 participants, risk ratio (RR) 0.75 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.57 to 0.97), moderate quality of evidence. We found no significant differences for any of the other primary outcomes considered: number of participants using cocaine during the treatment, two studies, 91 participants: RR 1.02 (95% CI 0.65 to 1.62); continuous abstinence, three studies, 139 participants: RR 1.30 (95% CI 0.73 to 2.32); side effects, six studies, 291 participants: RR 1.01 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.10); and craving, four studies, 240 participants: RR 0.13 (‐1.08 to 1.35). For all of these comparisons we rated the quality of evidence as low.

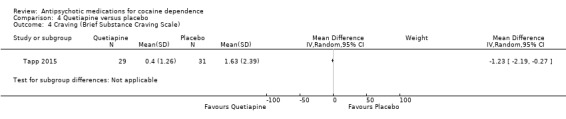

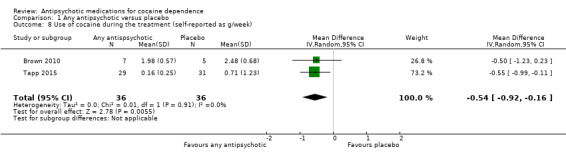

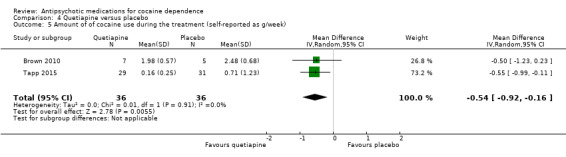

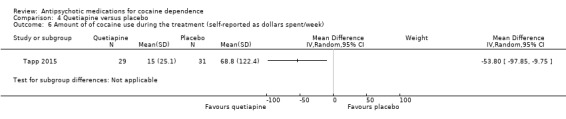

Comparisons of single drug versus placebo or versus another drug are conducted in few trials with small sample sizes, limiting the reliability of the results. Among these comparisons, only quetiapine seemed to outperform placebo in reducing cocaine use, measured by grams per week: mean difference (MD) ‐0.54 (95% CI ‐0.92 to ‐0.16), by US dollars spent per week: MD ‐53.80 (95% CI ‐97.85 to ‐9.75), and by craving: MD ‐1.23 (95% CI ‐2.19 to ‐0.27), but results came from one study with 60 participants.

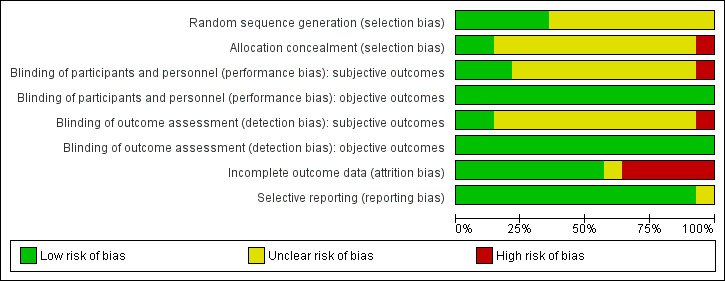

The major limitations of the studies were the high risk of attrition bias (40% of the included studies) and low quality of reporting, mainly for the risk of selection bias, performance and detection bias, that we rated as being at unclear risk for 75% to 80% of the studies. Furthermore, most of the included studies did not report results on important outcomes such as side effects, or use of cocaine during treatment and craving, which prevented the possibility of including them in statistical synthesis.

Authors' conclusions

At present, there is no evidence supporting the clinical use of antipsychotic medications in the treatment of cocaine dependence, although results come from only 14 trials, with small sample sizes and moderate to low quality of evidence.

Keywords: Humans, Antipsychotic Agents, Antipsychotic Agents/therapeutic use, Aripiprazole, Aripiprazole/therapeutic use, Benzodiazepines, Benzodiazepines/therapeutic use, Cocaine‐Related Disorders, Cocaine‐Related Disorders/drug therapy, Haloperidol, Haloperidol/therapeutic use, Lamotrigine, Olanzapine, Patient Dropouts, Patient Dropouts/statistics & numerical data, Quetiapine Fumarate, Quetiapine Fumarate/therapeutic use, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Reserpine, Reserpine/therapeutic use, Risperidone, Risperidone/therapeutic use, Triazines, Triazines/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Antipsychotic medications for cocaine dependence

Background

Cocaine dependence is often associated with medical, psychological and social problems for individual and public health, generating problems for the community. Users play a role in the spread of infectious diseases such as AIDS, hepatitis and tuberculosis, as well as in crime, violence and neonatal drug exposure. Use of drugs such as antidepressants, anticonvulsants and dopamine agonists to treat cocaine abuse or dependence is not supported by evidence from Cochrane reviews. The use of antipsychotic agents has also been considered, particularly because cocaine can induce hallucinations and paranoia that mimic psychosis.

Study characteristics

The review authors identified 14 randomised controlled trials involving 719 adults. One study was conducted in Italy, and the rest in the USA. They involve both inpatient and outpatient settings and had a duration of 14 to 168 days (mean 80 days). Eleven trials randomised participants to receive an antipsychotic drug or placebo using the following antipsychotic medications: risperidone (three studies, 1 to 4 mg/day and one study with injections of long‐acting risperidone at a dose of 25 mg/14 days); olanzapine (three studies, 2.5 to 20 mg/day); quetiapine (two studies, 400 and 800 mg/day); lamotrigine (one study, 400 mg/day); reserpine (one study, 50 mg/day). Three trials compared two drugs; olanzapine (10 mg/day) versus haloperidol (10 mg/day), olanzapine (20 mg/day) versus risperidone (9 mg/day) and aripiprazol (10 mg/day) versus ropirinol (4.5 mg/day).

Key results

The studies used different instruments or ways to assess the outcomes of interest, limiting the possibility for us to combine the data. When we grouped together all trial results comparing any antipsychotic drug to placebo, we found that antipsychotics slightly increase those who stayed in treatment but they were not effective in reducing cocaine use during treatment (two studies), in sustained abstinence (three studies), or in reducing the urge to consume cocaine (four studies). The single comparisons of each drug versus placebo or versus another drug were made in few trials with small sample sizes, limiting the reliability of the results. However, among these comparisons, only quetiapine seemed to perform better than placebo in reducing cocaine use and craving, but results came only from one study with 60 participants. Information was limited on the acceptability of treatment in terms of side effects, abstinence from cocaine use and withdrawal symptoms. Overall we found no evidence supporting the clinical use of antipsychotic medications in the treatment of cocaine dependence.

Quality of the evidence

The major limitations of the studies were the high number of people who withdrew from them and the lack of clear reporting of the methods used to conduct the studies. Moreover, the number of participants was small, and different ways of measuring and reporting results were used, limiting the possibility for us to combine the data. Overall we judged the quality of the evidence to be moderate for dropouts and low for all the other outcomes considered. The evidence is current up to 15 of July 2015.

Funding and conflict of interest reported by the studies

The majority of trials included in this review had funding from industrial sources or declared conflict of interests for some of the researchers due to different contractual collaborations with the pharmaceutical industry. Only five of the 14 included trials reported being funded exclusively by non‐industry sources, and of these just one (Grabowski 2004) disclosed no conflict of interest for the authors. Another study (Brown 2012) reported conflicts of interest for several authors and three studies (Levin 1999, Reid 2005 and Winhusen 2007) did not disclose conflict of interest of the authors. One included trial (Meini 2010) did not report information about funding sources, but disclosed no conflict of interest for the authors. The other eight studies included in this review were either funded by industry (Brown 2010; Hamilton 2009; Kampman 2003), or by a combination of industry and non‐industry grants (Akerele 2007; Loebl 2008; Smelson 2004; Smelson 2006; Tapp 2015), with three (Brown 2010; Hamilton 2009; Kampman 2003) disclosing conflicts of interests for the authors, and the rest without declaration on this issue.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Any antipsychotic versus placebo for cocaine dependence (Update).

| Any antipsychotic versus placebo for cocaine dependence | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with cocaine dependence Settings: outpatients or inpatients Intervention: Any antipsychotic versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Any antipsychotic versus placebo | |||||

| Dropouts Number of participants who dropped out from the study Follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | Study population | RR 0.75 (0.57 to 0.97) | 397 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | ||

| 547 per 1000 | 411 per 1000 (312 to 531) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 500 per 1000 | 375 per 1000 (285 to 485) | |||||

| Side effects Number of participants with at least i side effect Follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | Study population | RR 1.01 (0.93 to 1.10) | 291 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2 | ||

| 497 per 1000 | 502 per 1000 (462 to 546) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 465 per 1000 | 470 per 1000 (432 to 512) | |||||

| Number of participants using cocaine during the treatment (as days/week by urine tests or self report) Number of participants that reported the use of cocaine during the treatment Follow‐up: mean 10 weeks | Study population | RR 1.02 (0.65 to 1.62) | 91 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low3,4 | ||

| 478 per 1000 | 488 per 1000 (311 to 775) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 596 per 1000 | 608 per 1000 (387 to 966) | |||||

| Continuous abstinence (number of participants who maintained negative drug screens for 2 ‐ 3 weeks) Number of participants that maintained negative cocaine screens for at least 2 ‐ 3 weeks Follow‐up: mean 12 weeks | Study population | RR 1.30 (0.73 to 2.32) | 139 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,5 | ||

| 197 per 1000 | 256 per 1000 (144 to 457) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 129 per 1000 | 168 per 1000 (94 to 299) | |||||

| Craving (Brief Substance Craving Scale) Brief Substance Craving Scale. Scale from: 0 to 4. Follow‐up: mean 11 weeks | The mean craving (brief substance craving scale) in the control groups was 2.39 score | The mean craving (Brief Substance Craving Scale) in the intervention groups was 0.13 higher (1.08 lower to 1.35 higher) | 240 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low6,7 | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1All the studies were at unclear risk of selection bias. 2One study was at high risk of selection bias, and the others at unclear risk. One study was at high risk of performance, detection bias and attrition bias, three at unclear risk. 3All the studies were at unclear risk of selection bias; one study was at unclear risk of performance and detection bias. 4Only two studies with 91 participants. 5Only three studies with 139 participants. 6All the studies were at unclear risk of selection, performance and attrition bias. One study was at high risk of attrition bias. 7High heterogeneity (I²: 85%).

Background

Description of the condition

Cocaine is an alkaloid derived from the coca leaf, being commonly used as powder, for intranasal or intravenous use, or as crack, a free‐base form which is normally smoked. Cocaine dependence is a major public health problem, characterised by recidivism and a host of medical and psychosocial complications (EMCDDA 2014a).

There is a wide and well‐documented range of consequences associated with acute and chronic use of this drug, such as medical, psychological and social problems, including the spread of infectious diseases (e.g. AIDS, hepatitis and tuberculosis), criminal behaviour, violence and neonatal drug exposure (Higgins 1994). Both injection and non‐injection cocaine use are thought to increase the risk of HIV infection through high‐risk injecting and sexual behaviours (Sorensen 1991).

The illicit use of cocaine has become a persistent health problem worldwide. According to the estimates of the World Drug Report 2015 (UNDOC 2015) about 0.4 % of the global population uses cocaine, and in recent European national population surveys between 0.3% and 9% of the adult population report having tried cocaine at least once (i.e. lifetime prevalence), with Ireland (6.8%), Spain (8.8%) and the United Kingdom (9%) being at the upper end of this range. Recent cocaine use (last 12 months) is, in general, reported by less than 1% of adults; in most countries, the range is between 0.1% and 1%. After a peak in 2008, a decline in cocaine use has been observed in almost all countries, including those reporting high prevalence rates. In Spain and the United Kingdom recent prevalence rates are still around 2%. Although cocaine prevalence figures are much lower than comparable figures for cannabis, levels of use among younger adults can be higher than the population average. Lifetime experience among 15‐ to 34‐year‐olds ranges from 0.7% to 11.9%, with the highest levels again being found in Spain (11.1%) and the United Kingdom (11.9%). Recent use ranges from 0.2% to 3.6%, with Denmark, Italy and the Netherlands all having rates of about 2%; Spain and the United Kingdom over 3% and 3.6% respectively (EMCDDA 2014b). In the USA in 2013, an estimated 1.5 million people (0.6%) were current cocaine users (NSDUH 2014).The number of people entering treatment for the first time in their life for primary cocaine use has been decreasing in recent years in countries with traditionally high prevalence, from a peak of 38,000 in 2008 to 24,000 in 2013 (EMCDDA 2015). Differences exist between countries, with more than 70% of all cocaine users being reported by only three European countries: Spain, Italy, and the United Kingdom (EMCDDA 2015).

Description of the intervention

Although effective pharmacotherapy is available for alcohol and heroin dependence (Amato 2010; Faggiano 2003; Mattick 2014; Minozzi 2010; O'Brian 2001), none exists currently for cocaine dependence despite more than two decades of clinical trials primarily involving antidepressant, anticonvulsant and dopaminergic medications.

Cocaine effect seems to rely on its ability to increase the availability of monoamines (dopamine, serotonin and noradrenaline) in the brain. The dopamine increase in specific areas of the mesolimbic system, which is shared by cocaine with other drugs like heroin, alcohol, cannabis and nicotine, has been involved in rewarding effect of drugs and self‐administration behaviour in animals and humans (Di Chiara 1988; Drevets 1999; Drevets 2001; Volkow 2003).

There has been extensive research of optimal pharmacological approaches to the treatment of cocaine dependence, with consideration of both dopamine antagonists and agonists (Grabowski 1997; Kosten 1996).

Four Cochrane reviews have been published on the efficacy of antidepressants (Pani 2011), carbamazepine (Lima Reisser 2009), dopamine agonists (Minozzi 2015) and psychostimulants (Castells 2010) for the treatment of cocaine dependence, but none of them found clear support for the efficacy of these treatments.

Cocaine dependence remains a disorder for which no pharmacological treatment of proven efficacy exists, although considerable advances in the neurobiology of this addiction could guide future medication development.

How the intervention might work

Antipsychotics have been candidates for the treatment of addiction for their ability to block dopamine receptors and counterbalance the increase in dopaminergic activity related to drugs' effects. However, while the short‐term effect of cocaine is associated with dopamine increase in definite brain areas, acute and protracted withdrawal from this drug is associated with diminished dopaminergic neurotransmission. This reduced dopaminergic tone may underlie impaired hedonic function and increased craving, so maintaining the addictive behaviour (Dackis 2002; Kuhar 1996). On this basis, the supposed efficacy of dopamine antagonists in cocaine addiction could be questionable, since their use could even further reduce dopamine tone. While these observations apply well to classical neuroleptics, which exert their action essentially through the dopaminergic system, the so‐called 'atypical' ones, like risperidone and olanzapine, extend their action to other brain systems which have been involved in drug addiction. Particularly, their action on the serotoninergic system has been regarded with interest, given the involvement of serotonin neurotransmission in addictive behaviour (Filip 2005). The use of atypical neuroleptics in cocaine addiction has also been criticised due to their antagonist effect on dopamine receptors. However, their interference with the serotoninergic system and a less severe side‐effect profile (Berk 1999; Leucht 1999) could improve the compliance of patients and promote their retention in treatment. These assumptions would support the use of atypical neuroleptics such as olanzapine and aripripazol in the treatment of cocaine addiction.

Furthermore, cocaine use can lead to symptoms mimicking psychosis, such as hallucinations and paranoia, and the use of antipsychotics may relieve these symptoms. Some of the antipsychotics more commonly studied for this purpose are, for example, haloperidol, olanzapine, quetiapine, clozapine, risperidone and lamotrigine.

Why it is important to do this review

This review is an update of the original Cochrane review (Amato 2007). The original version on the efficacy of antipsychotic agents for the treatment of cocaine dependence did not find evidence supporting the clinical use of antipsychotic medications in the treatment of cocaine dependence.

This update reviews the current state of scientific evidence for the efficacy of antipsychotic pharmacotherapy for the treatment of cocaine dependence.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and the acceptability of antipsychotic medications for cocaine dependence.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials which focus on the use of any antipsychotic medication for cocaine dependence.

Types of participants

Cocaine‐dependent people as diagnosed by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM‐IV‐R) or by specialists, since all trials have been performed prior to the publication of the DSM‐V Manual. Trials including participants with additional diagnoses of substance dependence were also eligible. We exclude trials in people under 18 years of age and in pregnant women, because of the substantially different approach to the clinical management of these people. People with comorbid mental health conditions were included and considered in a subgroup analysis.

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention:

Any antipsychotic medication, alone or in combination with any psychosocial intervention.

Control Intervention

Placebo

No intervention

Other pharmacological interventions

Any psychosocial intervention

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Dropouts from treatment, defined as the number of participants who did not complete the treatment

Acceptability of the treatment, defined as the number and type of side effects experienced during the treatment

Use of primary substance of abuse, defined as the number of participants that reported the use of cocaine during the treatment, and/or the number of participants with urine samples positive or negative for cocaine

Results at follow‐up, defined as the number of participants using cocaine at follow‐up

Secondary outcomes

Compliance

Craving as measured by validated scales, e.g. Brief Substance Craving Scale (BSCS), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)

Severity of dependence as measured by validated scales, e.g. Addiction Severity Index (ASI), Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI‐S), Clinical Global Impression ‐ Observer Scale (CGI‐O)

Amount of cocaine use, as measured by grams used or money spent

Psychiatric symptoms/psychological distress, diagnosed using standard criteria, e.g. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐IV) criteria, or measured by validated scales, e.g. Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM‐D), Profile of Mood States Scale (POMSS), Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)

Withdrawal symptoms, measured using validated scales such as the Cocaine Selective Severity Assessment (CSSA)

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We have listed the search methods we used in the original review (Amato 2007) in Appendix 1

For the update performed up to 15 July 2015, we searched the following databases:

Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group (CDAG) Specialised Register (searched July 2015) using the search strategy outlined in Appendix 2;

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2015, Issue 7) using the search strategy outlined in Appendix 3;

MEDLINE (PubMed) (October 2006 to July 2015) using the search strategy outlined in Appendix 4;

EMBASE (Elsevier, EMBASE.com) (October 2006 to July 2015) using the search strategy outlined in Appendix 5;

CINAHL (EBSCO HOST) (October 2006 to July 2015)) using the search strategy outlined in Appendix 6;

Web of Science (Thomson Reuters) (January 2006 to January 2015) using the search strategy outlined in Appendix 7.

Searching other resources

We also searched:

The reference lists of all relevant papers to identify further studies

Some of the main electronic sources of ongoing trials (National Research Register, meta‐Register of Controlled Trials, ClinicalTrials.gov)

We contacted investigators to request information about unpublished or incomplete trials.

All searches included non‐English language literature, and we assessed studies with English abstracts for inclusion. We had studies translated where we considered that they were likely to meet the inclusion criteria.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

For the first review, one review author (LA) inspected the search hits by reading titles and abstracts. We obtained each potentially relevant study located in the search in full text, and two review authors (SM, LA) independently assessed them for inclusion. We resolved disagreements by discussion between all the review authors.

For the present update, two review authors (BII, SM) inspected the search hits by reading titles and abstracts. We obtained each potentially relevant study located in the search in full text, and two review authors (BII, SM) independently assessed them for inclusion. We resolved disagreements by discussion between all the review authors.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (SM, BII) independently extracted data . In case of missing data about declared outcomes in the full article, we also consulted the information reported in the Clinical Trials Registry of the US National Institutes of Health (ClinicalTrials.gov). We resolved any disagreement by discussion. We summarised key findings narratively in the first instance, and assessed them for meta‐analysis where possible.

We extracted the following data from the identified publications:

Year of publication

Country

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Mean characteristics of participants (age, sex, other substances of abuse, comorbidity)

Experimental and control treatment

Outcomes assessed

Duration of the study

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (BII, SM) independently assessed risk of bias of the included studies.

We conducted the 'Risk of bias' assessment using the criteria recommended by the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2011). The recommended approach for assessing risk of bias in studies included in Cochrane reviews is a two‐part tool, addressing specific domains, namely sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and providers (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessor (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) and selective outcome reporting (reporting bias). The first part of the tool involves describing what was reported to have happened in the study. The second part of the tool involves assigning a judgement related to the risk of bias for that entry, in terms of low, high or unclear risk. To make these judgements we used the criteria indicated by the Handbook, adapted to the addiction field. See Appendix 8 for details.

We addressed the domains of sequence generation and allocation concealment (avoidance of selection bias) in the tool by a single entry for each study.

We considered blinding of participants and of outcome assessors (avoidance of detection bias) separately for objective outcomes (e.g. dropouts, abstinence measured by urinanalysis, participants relapsed at the end of follow‐up) and for subjective outcomes (e.g. duration and severity of signs and symptoms of withdrawal, craving, participant self‐reported use of substances, side effects, psychiatric symptoms, clinical global evaluation).

We assessed incomplete outcome data (avoidance of attrition bias) for all outcomes except for the dropout rates from the treatment, which is very often the primary outcome measure in trials on addiction; see Characteristics of included studies for a detailed description of how we assessed the risks of bias in this review.

Grading of evidence

We assessed the overall quality of the evidence for the primary outcome using the GRADE system. The GRADE Working Group developed a system for grading the quality of evidence (GRADE 2004; Guyatt 2008; Guyatt 2011; Schünemann 2006) which takes into account issues not only related to internal validity but also to external validity, such as directness of results. The 'Summary of findings' tables present the main findings of a review in a transparent and simple tabular format. In particular, they provide key information concerning the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined and the sum of available data on the main outcomes.

The GRADE system uses the following criteria for assigning grades of evidence:

High: further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate: further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low: further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low: any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

Grading is decreased for the following reasons:

Serious (‐1) or very serious (‐2) limitation to study quality.

Important inconsistency (‐1).

Some (‐1) or major (‐2) uncertainty about directness.

Imprecise or sparse data (‐1).

High probability of reporting bias (‐1).

Grading is increased for the following reasons:

Strong evidence of association ‐ significant relative risk of > 2 (< 0.5) based on consistent evidence from two or more observational studies, with no plausible confounders (+1).

Very strong evidence of association ‐ significant relative risk of > 5 (< 0.2) based on direct evidence with no major threats to validity (+2).

Evidence of a dose‐response gradient (+1).

All plausible confounders would have reduced the effect (+1).

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed dichotomous outcomes by calculating the risk ratio (RR) for each trial with uncertainty in each result expressed by 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We analysed continuous outcomes by calculating the mean difference (MD) with a 95% CI when studies used the same instrument to assess the outcome. We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) when studies used different instruments. For craving score, severity of dependence (Drug ASI, CGI‐O, depression (HAM‐D) and anxiety (Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM‐A)), we compared the postintervention mean scores of the experimental and control groups. Meta‐analysis of continuous outcomes of the old studies of ASI, CGI‐O, HAM‐D and HAM‐A had to be redone for postintervention outcomes, because the previous type of analysis comparing before‐and‐after changes was incorrect.

Unit of analysis issues

We have not used data presented as the number of positive urine tests over the total number of tests in the experimental and control group as a measure of substance abuse. This is because using tests instead of the participants as the unit of analysis violates the hypothesis of independence among observations. In fact, the results of tests done in each participant are not independent.

If there had been cross‐over trials to include, we would have considered only the results of the first phase of the study.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We analysed heterogeneity by using the I² statistic and the Chi² test. Cut‐off points included an I² value greater than 50% and a P value for the Chi² test less than 0.1.

Assessment of reporting biases

We planned to use a funnel plot (plotting the effect from each study against the sample size or effect standard error) to assess the potential for bias related to the size of the trials, which could indicate possible publication bias. However this was not possible because less than ten trials were included in the analyses

Data synthesis

We combined outcomes from the individual trials through meta‐analysis when possible (comparability of interventions and outcomes between trials), using a random‐effects model, because we expected some degree of heterogeneity among trials.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We first compared any antipsychotic versus placebo. We then performed subgroup analyses for single types of antipsychotics.

Sensitivity analysis

To incorporate our assessment of risk of bias into the review process, we first plotted the intervention effect estimates stratified for risk of selection bias. If we had found differences in results among studies at different risks of bias, we planned to perform sensitivity analysis by excluding from the analysis those studies at high risk of bias. We did not conduct these analyses, because we found no studies at high risk of selection bias. Neither did we conduct sensitivity analysis excluding studies with inadequate allocation concealment, because only one of the included studies had inadequate allocation concealment, and it was not included in meta‐analysis

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

In the original review (Amato 2007), the bibliographic searches identified 97 reports; we excluded 80 studies on the basis of title and abstract, and retrieved 17 articles in full text, 8 of which we excluded, two were awaiting assessment and seven satisfied all the criteria to be included in the review.

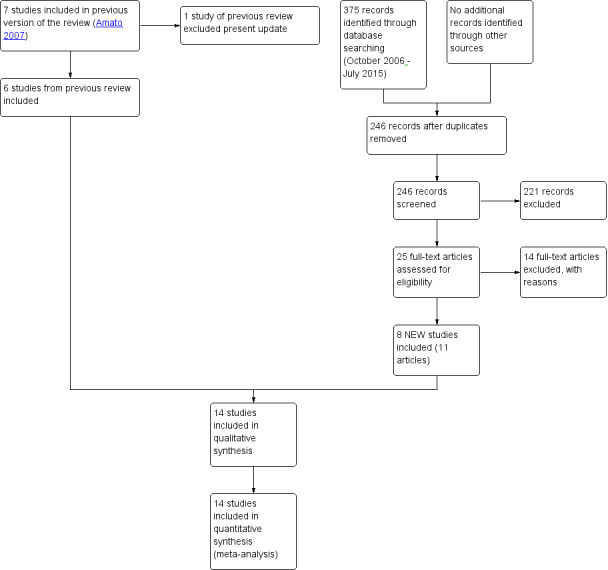

For the present update, we identified 246 reports after removing duplicates, of which we excluded 221 on the basis of title and abstract; we retrieved 25 articles in full text for more detailed evaluation, 14 of which we excluded, and 11 articles (eight studies) satisfied all the criteria to be included in the review. SeeFigure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram. Review update 2015.

We excluded from the review one study which was included in the first version (Berger 1996). For substantive descriptions of studies see 'Characteristics of included studies' and 'Characteristics of excluded studies' tables.

Included studies

We include 14 studies (719 participants); six from the original review and eight studies from the update.

Duration of trials: The mean duration of the trials was 80 days (range 14 to 168 days).

Treatment regimens and setting: Thirteen studies were conducted in the USA and one in Italy. The antipsychotic medication used in the included studies were:

Risperidone: five studies (Akerele 2007; Grabowski 2004; Levin 1999; Loebl 2008; Smelson 2004), mean dose for four of the studies 2.27 mg/day (range 1 to 4 mg) and one study with injections of long‐acting risperidone at a dose of 25 mg/14 days;

Olanzapine: five studies (Akerele 2007; Hamilton 2009; Kampman 2003; Reid 2005; Smelson 2006), mean dose 14 mg/day (range 2.5 to 20 mg/day);

Haloperidol: one study (Smelson 2006), using a target dose of 10 mg/day;

Quetiapine: two studies (Brown 2010; Tapp 2015), using doses of 400 ‐ 800 and 400 mg/day respectively;

Lamotrigine: one study (Brown 2012), using a dose of 400 mg/day;

Reserpine: one study (Winhusen 2007), using a dose of 50 mg/day;

Aripiprazol: one study (Meini 2010), using a dose of 10 mg/day.

Twelve studies were conducted in the outpatient setting, two studies in an inpatient .

Participants: The studies covered 719 cocaine‐dependent participants; 469 from nine studies according to DSM‐IV criteria (DSM‐IV‐R) and 250 from five studies with different diagnostic criteria: 142 participants from two studies based on a reference to a previous diagnosis of dependence and recent use of cocaine; 28 participants from a study selected according to ICD‐9‐CM criteria; 20 diagnosed for another study using the Mini‐International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI); and one study with 30 participants requiring certification by a psychiatrist); 477/719 (66.3%) were men, but two studies (Smelson 2004; Smelson 2006) did not report data on gender; the mean age was 41.5 years.

Rating instruments used in the studies:

Acceptability of the treatment:

Side effects:

Abnormal Involuntary Movements Scale (NIMH 1988) used by Akerele 2007

Simpson‐Angus Scale (Simpson 1970) used by Akerele 2007

Craving:

Brief Substance Craving Scale (Somoza 1995) used by Kampman 2003, Reid 2005, Tapp 2015 and Winhusen 2007

Cocaine Craving Questionnaire (Tiffany 1993) used by Reid 2005, Brown 2010,Brown 2012 and Hamilton 2009

Visual Analogue Scale (McCormack 1988) used by Levin 1999 and Meini 2010

Voris Cocaine Craving Questionnaire (Smelson 1999) used by Smelson 2004 and Smelson 2006

Cocaine Craving Report (Weddington 1990) used by Akerele 2007

Cocaine Craving Scale (Halikas 1991) used by Loebl 2008

Use of cocaine:

Timeline Followback Interview (Sobell 1992) used by Brown 2012, Reid 2005, Tapp 2015 and Winhusen 2007

Severity of dependence:

Addiction Severity Index (McLellan 1992) used by Akerele 2007, Brown 2012, Grabowski 2004, Hamilton 2009, Kampman 2003, Loebl 2008, Reid 2005, and Winhusen 2007

Clinical Global Impression Scale (Guy 1976) used by Akerele 2007, Meini 2010 and Reid 2005

Psychiatric symptoms/psychological distress:

Anxiety

Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (Hamilton 1959) used by Kampman 2003 and Reid 2005

Depression

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Hamilton 1967) used by Akerele 2007, Brown 2012, Kampman 2003, Loebl 2008, Reid 2005, and Winhusen 2007

Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology‐SR (Rush 2003) used by Brown 2010 and Brown 2012

Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1996) used by Grabowski 2004

Psychopathology

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (Kay 1992) used by Akerele 2007 and Smelson 2006

Snaith‐Hamilton Pleasure Scale (Snaith 1995) used by Loebl 2008

Young Mania Rating Scale (Young 1978) used by Brown 2010 and Brown 2012

Withdrawal symptoms:

Cocaine Selective Severity Assessment (Kampman 1998) used by Kampman 2003 and Loebl 2008

Comparisons:

Any antipsychotic versus placebo: eight studies, 430 participants (Brown 2010; Grabowski 2004; Kampman 2003; Levin 1999; Loebl 2008; Smelson 2004; Tapp 2015; Winhusen 2007)

Risperidone versus placebo: four studies, 176 participants (Grabowski 2004; Levin 1999; Loebl 2008; Smelson 2004)

Olanzapine versus placebo: three studies, 146 participants (Hamilton 2009; Kampman 2003; Reid 2005)

Quetiapine versus placebo: two studies, 72 participants (Brown 2010; Tapp 2015)

Lamotrigine versus placebo: one study, 112 participants (Brown 2012)

Reserpine versus placebo: one study, 119 participants (Winhusen 2007)

Olanzapine versus haloperidol: one study, 31 participants (Smelson 2006)

Olanzapine versus risperidone: one study, 28 participants (Akerele 2007)

Aripiprazol versus ropirinole: one study, 28 participants (Meini 2010)

Grabowski 2004 has three arms, comparing risperidone 2 mg and 4 mg versus placebo; we have used the 33 participants in the placebo arm in both Analysis 1.1 and Analysis 2.1.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antipsychotic versus placebo, Outcome 1 Dropouts.

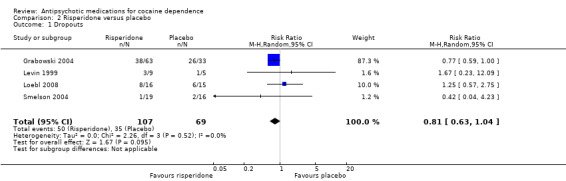

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Risperidone versus placebo, Outcome 1 Dropouts.

Excluded studies

Twenty‐four studies did not meet the criteria for inclusion. The grounds for exclusion were the following: study design: ; objective of the studies and outcomes measures: 16 studies (Evans 2001; Farren 2000; Haney 2011; Price 1997; Sherer 1988; Ersche 2010; Lile 2008; Lile 2011; Lofwall 2014; Máñez 2010; Netjek 2008; Middleton 2009; Nuzzo 2012; Rush 2009; Stoops 2007; Landabaso 2009); impossible to extract usable data: six studies (Grabowski 2000; Rubio 2006a; Rubio 2006b; Landabaso 2003; Sayers 2005; Tsuang 2002). We now excluded one study (Grabowski 2006), included in the previous version as an ongoing trial which met the inclusion criteria, due to a modification in the study protocol in 2007. The pharmacological intervention had been modified, substituting an antipsychotic drug (aripiprazol) with an antidepressant (citalopram), thus rendering it ineligible for this update. Another study included in the previous version (Berger 1996) was excluded from the update because the outcome did not comply with our inclusion criteria.

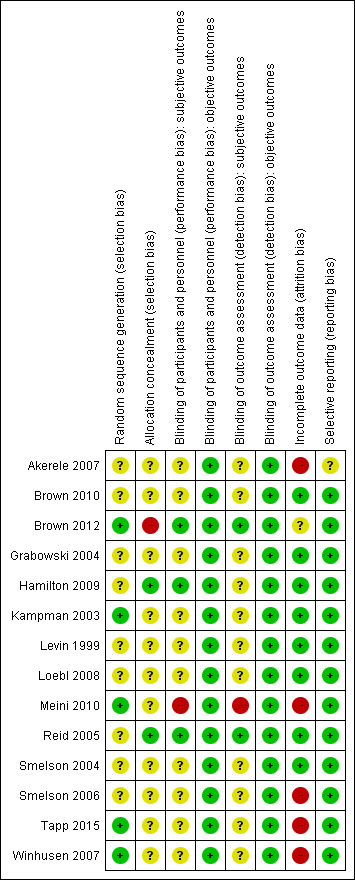

Risk of bias in included studies

All the studies were randomised controlled trials.

Allocation

Random sequence generation: we judged five studies to be at low risk of bias (Brown 2012; Kampman 2003; Meini 2010; Tapp 2015; Winhusen 2007). All the other were at unclear risk of bias because no information was provided about the methods followed.

Allocation concealment: Only two studies (Hamilton 2009; Reid 2005) had an adequate allocation concealment. One study (Brown 2012) presented a high risk of bias due to an inadequate concealment of allocation. In all the other studies the concealment of allocation was unclear.

Blinding

Performance bias

Objective outcomes: we judged all the studies to be at low risk of bias, because we considered that lack of blinding was unlikely to bias the outcomes.

Subjective outcomes: we judged only three studies (Brown 2012; Hamilton 2009; Reid 2005) to be at low risk of performance bias. One study (Meini 2010) was open‐label and judged to be at high risk of bias. All the other studies simply stated that they were double‐blind without further description, so we judged them to be at unclear risk.

Detection bias

Objective outcome: we judged all the studies to be at low risk of bias, because we considered that lack of blinding was unlikely to bias the outcomes.

Subjective outcomes: we rated only two studies (Brown 2012; Reid 2005) at low risk of performance bias. One study (Meini 2010) was open‐label and judged to be at high risk of bias . None of the other studies reported any information on this domain, so we judged them to be at unclear risk.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged five studies (Akerele 2007; Meini 2010; Smelson 2006; Tapp 2015; Winhusen 2007) to be at high risk of attrition bias because more than 30% of participants dropped out and there was no imputing of missing data or intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analysis.

One study (Brown 2012) did not report sufficient information for us to evaluate the risk of attrition bias. We rated all the other studies at low risk of attrition bias.

Selective reporting

All but one study (Akerele 2007) reported on the primary outcomes prespecified in the Methods section.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

We summarised the results, with comparisons of quantitative data where possible, first for any antipsychotic drug versus placebo (see Table 1) and then comparing separately the different types of antipsychotic medications versus placebo, as well as separate analyses for olanzapine versus haloperidol, olanzapine versus risperidone, and aripiprazol versus ropinirol.

For some outcomes reported in the included studies, it was impossible to pool the data due to the different ways of reporting the results. Different rating instruments were used and for many of them the authors did not indicate the scores considered to represent boundaries of mild, moderate and severe, to allow comparison of results between studies.

Primary outcomes

Dropouts from the treatment

Measured as number of participants who did not complete the treatment

(01) Any antipsychotic versus placebo

Eight studies (Brown 2010; Grabowski 2004; Kampman 2003; Levin 1999; Loebl 2008; Smelson 2004; Tapp 2015; Winhusen 2007), 430 participants, see Analysis 1.1 and Table 1: Risk ratio (RR) 0.75 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.57 to 0.97; I² = 27%); the results favour antipsychotic treatment.

(02) Risperidone versus placebo

Four studies (Grabowski 2004; Levin 1999; Loebl 2008; Smelson 2004), 176 participants, see Analysis 2.1, RR 0.81 (95% CI 0.63 to 1.04). The result shows a small but statistically non‐significant trend in favour of risperidone.

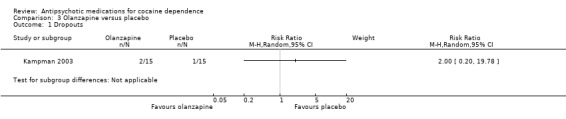

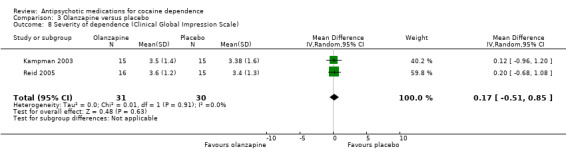

(03) Olanzapine versus placebo

One study (Kampman 2003), 30 participants, RR 2.00 (95% CI 0.20 to 19.78), see Analysis 3.1. No significant difference.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Olanzapine versus placebo, Outcome 1 Dropouts.

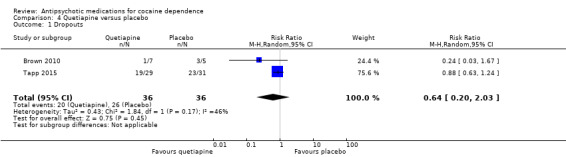

(04) Quetiapine versus placebo

Two studies (Brown 2010; Tapp 2015), 72 participants, RR 0.64 (95% CI 0.20 to 2.03), see Analysis 4.1. No significant difference.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Quetiapine versus placebo, Outcome 1 Dropouts.

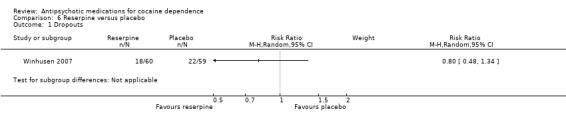

(06) Reserpine versus placebo

One study (Winhusen 2007), 119 participants, RR 0.80 (95% CI 0.48 to 1.34), see Analysis 6.1. No significant difference.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Reserpine versus placebo, Outcome 1 Dropouts.

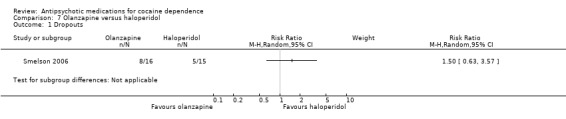

(07) Olanzapine versus haloperidol

One study (Smelson 2006), 31 participants, RR 1.50 (95% CI 0.63 to 3.57), see Analysis 7.1. No significant difference.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Olanzapine versus haloperidol, Outcome 1 Dropouts.

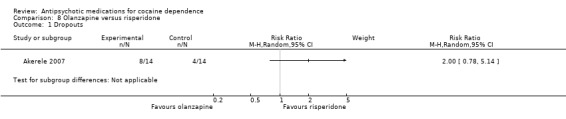

(08) Olanzapine versus risperidone

One study (Akerele 2007), 28 participants, RR 2.00 (95% CI 0.78 to 5.14), see Analysis 8.1. No significant difference.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Olanzapine versus risperidone, Outcome 1 Dropouts.

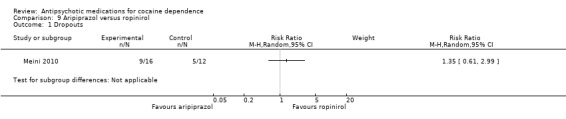

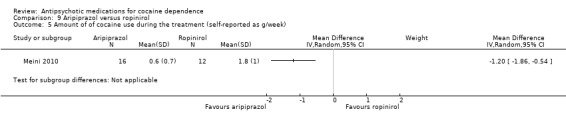

(09) Aripiprazol versus ropinirol

One study (Meini 2010), 28 participants, RR 1.35 (95% CI 0.61 to 2.99), see Analysis 9.1. No significant difference.

9.1. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Aripiprazol versus ropinirol, Outcome 1 Dropouts.

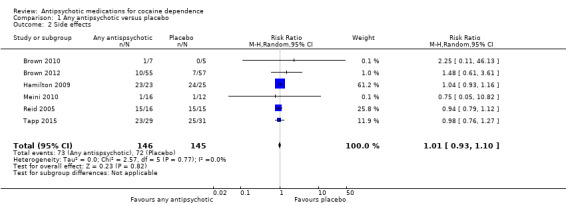

Acceptability of the treatment

Measured as number of participants presenting at least one side effect

(01) Any antipsychotic versus placebo

Six studies (Brown 2010; Brown 2012; Hamilton 2009;Meini 2010; Reid 2005; Tapp 2015), 291 participants, RR 1.01 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.10), see Analysis 1.2 and Table 1; no statistically significant difference.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antipsychotic versus placebo, Outcome 2 Side effects.

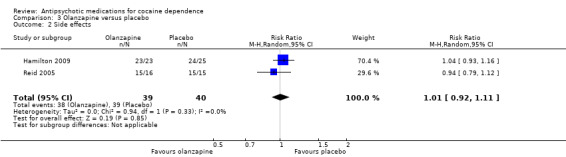

(03) Olanzapine versus placebo

Two studies (Hamilton 2009; Reid 2005), 79 participants, RR 1.01 (95% CI 0.92 to 1.11), see Analysis 3.2, no significant difference.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Olanzapine versus placebo, Outcome 2 Side effects.

One study (Kampman 2003) reported that adverse events were evenly distributed between the olanzapine and placebo groups, without significant differences in the occurrence of any adverse event between the two groups.

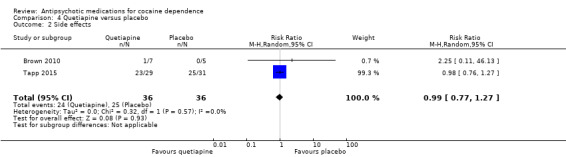

(04) Quetiapine versus placebo

Two studies (Brown 2010; Tapp 2015), 72 participants, RR 0.99 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.27), see Analysis 4.2; no significant difference.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Quetiapine versus placebo, Outcome 2 Side effects.

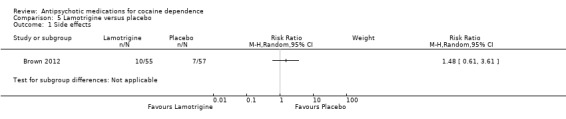

(05) Lamotrigine versus placebo

One study (Brown 2012), 112 participants, RR 1.48 (95% CI 0.61 to 3.61), see Analysis 5.1, no significant difference.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Lamotrigine versus placebo, Outcome 1 Side effects.

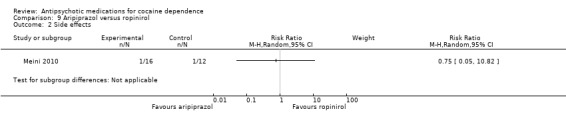

(09) Aripiprazol versus ropinirol One study (Meini 2010), 28 participants, RR 0.75 (95% CI 0.05 to 10.82), see Analysis 9.2, no significant difference.

9.2. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Aripiprazol versus ropinirol, Outcome 2 Side effects.

Use of primary substance of abuse

(01) Any antipsychotic versus placebo

Measured as the number of participants that reported the use of cocaine during the treatment

Two studies (Reid 2005; Tapp 2015), 91 participants, RR 1.02 (95% CI 0.65 to 1.62), see Analysis 1.3 and Table 1; no significant difference.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antipsychotic versus placebo, Outcome 3 Number of participants using cocaine during the treatment (as days/week by urine tests or self report).

Measured as continuous abstinence (number of participants that maintained negative cocaine screens for at least 2 ‐ 3 weeks)

Three studies (Hamilton 2009; Reid 2005; Tapp 2015), 139 participants, RR 1.30 (95% CI 0.73 to 2.32), see Analysis 1.4 and Table 1; no significant difference.

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antipsychotic versus placebo, Outcome 4 Continuous abstinence (number of participants who maintained negative drug screens for 2 ‐ 3 weeks).

(02) Risperidone versus placebo

Measured as the number of participants that maintained negative cocaine screens throughout the treatment period

One study (Loebl 2008) of 31 participants, reported that five participants in the risperidone group had negative cocaine screens at 50% or more of their visits throughout the treatment period, and that the 11 other participants were abstinent at 28% or fewer of their visits. Only one participant in the placebo group had negative cocaine screens at 50% or more of their visits. The difference was not statistically significant (Fisher exact test = 0.17). Participants in the risperidone group had a mean reduction in days of cocaine use in the preceding 30 days of 51% (standard deviation (SD) 45%), and in the placebo group of 9% (SD 117%). This difference was also not statistically significant.

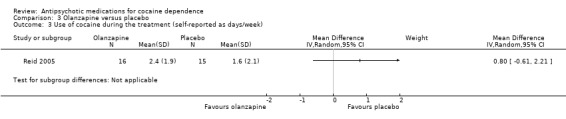

(03) Olanzapine versus placebo

Measured as the number of participants that reported the use of cocaine during the treatment

One study (Reid 2005) of 31 participants measured self‐reported cocaine use in days/week, and did not find a statistically significant treatment effect, MD 0.80 (95% CI ‐0.61 to 2.21), seeAnalysis 3.3.

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Olanzapine versus placebo, Outcome 3 Use of cocaine during the treatment (self‐reported as days/week).

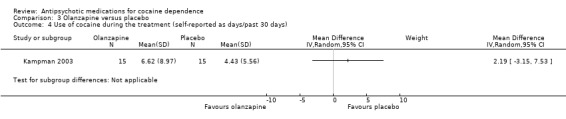

A second study (Kampman 2003) measured self‐reported cocaine use in days during the past 30 days in 30 participants, and reported similar results: MD 2.19 (95% CI ‐3.15 to 7.53), seeAnalysis 3.4.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Olanzapine versus placebo, Outcome 4 Use of cocaine during the treatment (self‐reported as days/past 30 days).

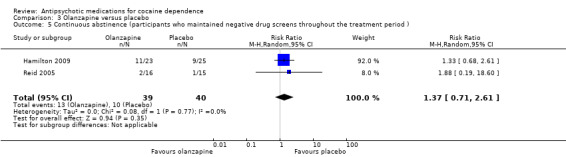

Measured as the number of participants that maintained negative cocaine screens throughout the treatment period

Two studies (Hamilton 2009; Reid 2005), 79 participants, RR 1.37 (95% CI 0.71 to 2.61; I² = 0%) see Analysis 3.5, did not find a statistically significant treatment effect on continuous abstinence.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Olanzapine versus placebo, Outcome 5 Continuous abstinence (participants who maintained negative drug screens throughout the treatment period ).

(04) Quetiapine versus placebo

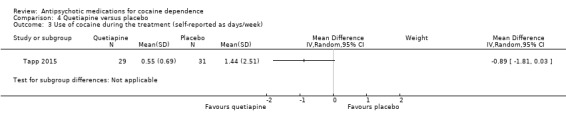

Measured as the number of participants that reported the use of cocaine during the treatment

One study (Tapp 2015), 60 participants, measured self‐reported cocaine use in days/week. No statistically significant results were reported, MD ‐0.89 (95% CI ‐1.81 to 0.03), see Analysis 4.3.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Quetiapine versus placebo, Outcome 3 Use of cocaine during the treatment (self‐reported as days/week).

Measured as the number of participants that had negative cocaine screens for three consecutive weeks

One study (Tapp 2015), 60 participants, showed no differences in terms of end‐of‐trial abstinence (13.7% in the quetiapine group versus 12.9% in the placebo group (Wald statistic = 0.01, df = 1, P = 0.92)). By the end of the study, 30% of participants who completed the study had achieved this remission, but there was no statistically significant difference in the percentage of change by group.

(05) Lamotrigine versus placebo

One study (Brown 2012) with 112 participants reported, using a declining‐effects random regression model, no differences in treatment effect between groups (F = 1.1, P = 0.31) in the percentage of days of cocaine use as measured by the change from week 1 to week 12.

(06) Reserpine versus placebo

Measured by weekly proportion of self‐reported cocaine non‐use days, confirmed by negative cocaine screens

One study(Winhusen 2007) of 119 participants showed a higher average of non‐use days (7%) than the reserpine group across the treatment period, and found no difference between groups over the treatment period (GEE, P = 0.45).

Results at follow‐up

None of the included studies presented results on follow‐up in a way suitable for use in a meta‐analysis or narrative description.

Secondary outcomes

Compliance

(03) Olanzapine versus placebo

Measured by pill count

One study (Hamilton 2009), 48 participants, reported no significant differences in mean percentage of adherence to prescribed olanzapine (93.4%, SD 9.9%) and prescribed placebo (90.1%, SD 13.1%); these did not significantly differ by one‐way ANOVA (F(1,43) = 0.896, P = 0.349).

Another study (Kampman 2003), 30 participants, described similar results with an average percentage of prescribed pills taken by the olanzapine‐treated participants of 84.5% compared to 89.3% in the placebo‐treated group (t = 0.629, df = 28, not statistically significant).

A third study (Reid 2005) of 31 participants reported that compliance with medication treatment was not significantly different between any treatment groups (P = 0.832).

(06) Reserpine versus placebo

Measured by pill count

One study (Winhusen 2007) of 119 participants assessed this outcome, calculating a compliance score from the number of tablets dispensed minus the number returned or reported lost divided by the number of tablets prescribed. The mean of this compliance score for the reserpine group, 0.79 (SD = 0.23), was not significantly different from that of the placebo group at 0.74 (SD = 0.34), (t = 1.13, P = 0.26).

(08) Olanzapine versus risperidone

Measured by self‐reported ingestion of medication

One study (Akerele 2007), 28 participants, showed no difference in the percentage reduction of self‐reported missed dosage over all administered doses: Olanzapine group 7% and risperidone group 8% (t = 0.31, df = 20, P = 0.76).

Craving

The included studies used different scales to rate this outcome, limiting the possibility to pool data.

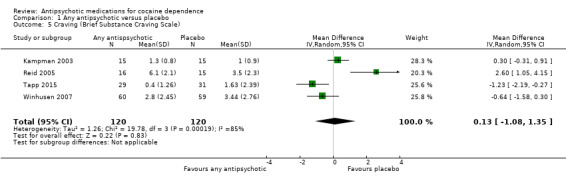

(01) Any antipsychotic versus placebo

Measured by Brief Substance Craving Scale

Four studies (Kampman 2003; Reid 2005; Tapp 2015; Winhusen 2007), 240 participants, MD 0.13 (95% CI ‐1.08 to 1.35), see Analysis 1.5 and Table 1, showed no significant difference, but heterogeneity was extremely high ( I2:85%) .

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antipsychotic versus placebo, Outcome 5 Craving (Brief Substance Craving Scale).

(02) Risperidone versus placebo

Measured by mean decrease of Visual Analogue Scale

In one study (Levin 1999),14 participants, using a scale from 0 to 100, the percentage reduction of the score after treatment was ‐31% in the risperidone group compared with ‐49% in the placebo group. The result was not y significant.

Measured by mean decrease in Minnesota Cocaine Craving Scale

One study (Loebl 2008) of 31 participants showed no treatment effect on intensity (F = 0.03, P = 0.86) or frequency (F = 1.69, P = 0.11) of craving, but described a trend for main effect in duration of craving episodes, with a smaller decrease in the risperidone group (56.6%) than in the placebo group (65.7%, F = 2.71, P = 0.11).

Measured by improvement on the Voris Cocaine Craving Questionnaire (VCCQ) subscale scores

One study (Smelson 2004) of 35 participants showed a significant main effect of time for the craving (F = 33.62, P = 0.01), mood (F = 5.78, P = 0.023), and sick (F = 4.264, P = 0.040) subscales of the VCCQ ( no further description is provided about which symptoms the term "sick" refers to), suggesting that participants in both groups improved over the course of the study.

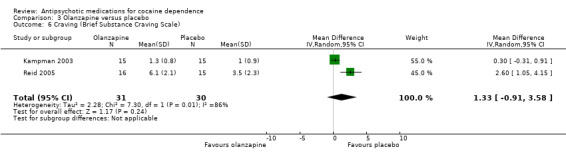

(03) Olanzapine versus placebo

Measured by Brief Substance Craving Scale

Two studies (Kampman 2003; Reid 2005), 61 participants, see Analysis 3.6. MD 1.33 (95% CI ‐0.91 to 3.58; I² = 86%). There is no significant difference that could indicate a treatment effect, but heterogeneity was extremely high .

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Olanzapine versus placebo, Outcome 6 Craving (Brief Substance Craving Scale).

Another study (Hamilton 2009), 48 participants, did not find statistically significant differences between the olanzapine and placebo groups for the Craving Questionnaire.

(04) Quetiapine versus placebo

Measured by Brief Substance Craving Scale

One study (Tapp 2015), 60 participants, reported no differences between groups in terms of absence of cravings (34.5% in quetiapine group versus 29.0% in placebo group; Wald statistic = 0.21,df = 1, P = 0.65). See also Analysis 4.4. MD ‐1.23 (95% CI ‐2.19 to ‐0.27), which also shows no statistically significant difference.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Quetiapine versus placebo, Outcome 4 Craving (Brief Substance Craving Scale).

(05) Lamotrigine versus placebo

Measured by Cocaine Craving Questionnaire

One study (Brown 2012), 112 participants, reported using a declining‐effects random regression model, and found no differences in treatment effect between groups (F = 0.4, P = 0.53) as measured by the change from week 1 to week 12.

(06) Reserpine versus placebo

Measured by Brief Substance Craving Scale

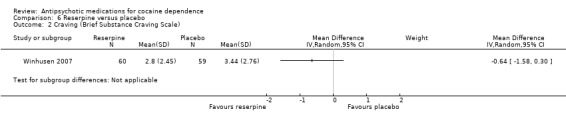

One study (Winhusen 2007), 119 participants, see Analysis 6.2. MD ‐0.64 (95% CI ‐1.58 to 0.30), no statistically significant difference.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Reserpine versus placebo, Outcome 2 Craving (Brief Substance Craving Scale).

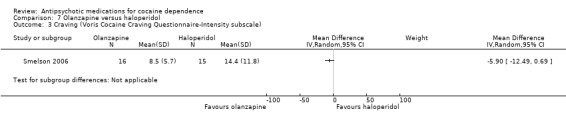

(07) Olanzapine versus haloperidol

Measured by Voris Cocaine Craving Questionnaire

One study (Smelson 2006), 31 participants, see Analysis 7.3. MD ‐5.90 (95% CI ‐12.49 to 0.69), no statistically significant difference.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Olanzapine versus haloperidol, Outcome 3 Craving (Voris Cocaine Craving Questionnaire‐Intensity subscale).

(08) Olanzapine versus risperidone

Measured by Cocaine Craving Report

One study (Akerele 2007), in an analysis of the cocaine‐dependent subgroup with 19 participants, reported no statistically significant differences between groups in terms of cocaine craving over time.

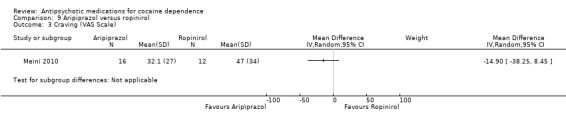

(09) Aripiprazol versus ropinirol

Measured by Voris Cocaine Craving Questionnaire

This small trial (Meini 2010) of 28 participants, found no statistically significant differences: MD ‐14.90 (95% CI ‐38.25 to 8.45), see Analysis 9.3.

9.3. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Aripiprazol versus ropinirol, Outcome 3 Craving (VAS Scale).

Severity of dependence

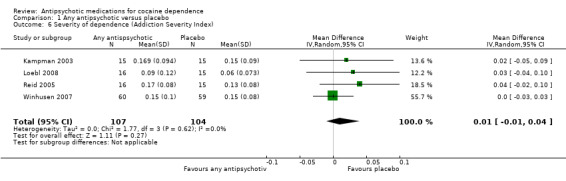

(01) Any antipsychotic versus placebo

Measured by Addiction Severity Index (ASI)

Four studies (Kampman 2003; Loebl 2008; Reid 2005; Winhusen 2007), 211 participants, MD 0.01 (95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.04), see Analysis 1.6, showed no statistically significant difference in ASI global scores.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antipsychotic versus placebo, Outcome 6 Severity of dependence (Addiction Severity Index).

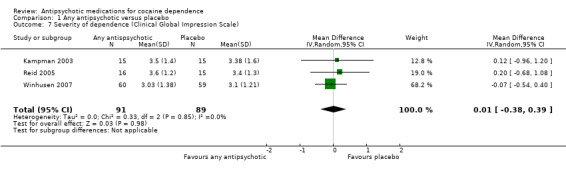

Measured by Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGIS)

Three studies (Kampman 2003; Reid 2005; Winhusen 2007), 180 participants, MD 0.01 (95% CI ‐0.38 to 0.39), see Analysis 1.7, showed a similar result on CGIS scores.

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antipsychotic versus placebo, Outcome 7 Severity of dependence (Clinical Global Impression Scale).

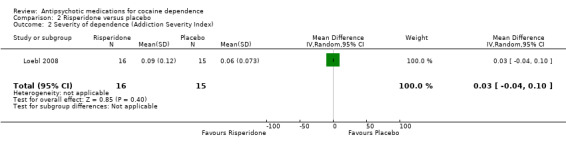

(02) Risperidone versus placebo

Measured by Addiction Severity Index (ASI)

One study (Loebl 2008) of 31 participants reported no main effect of treatment for cocaine selective ASI scores, and showed no statistically significant differences in drug composite scores: MD 0.03 (95% CI ‐0.04 to 0.10), see Analysis 2.2.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Risperidone versus placebo, Outcome 2 Severity of dependence (Addiction Severity Index).

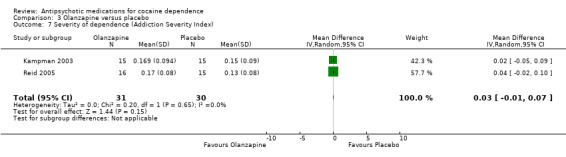

(03) Olanzapine versus placebo

Measured by Addiction Severity Index (ASI) Two studies (Kampman 2003; Reid 2005), 61 participants, see Analysis 3.7. MD 0.03 (95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.07) showed no statistically significant differences.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Olanzapine versus placebo, Outcome 7 Severity of dependence (Addiction Severity Index).

One study (Hamilton 2009), 48 participants, identified no statistically significant differences between the olanzapine and placebo groups on any of the ASI subscale measures.

Measured by Clinical Global Impression Scale Using another measuring instrument, the above‐mentioned two studies (Kampman 2003; Reid 2005), 61 participants, see Analysis 3.8, MD 0.17 (95% CI ‐0.51 to 0.85) presented similar non‐significant results.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Olanzapine versus placebo, Outcome 8 Severity of dependence (Clinical Global Impression Scale).

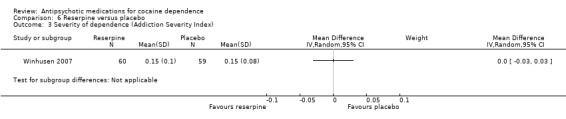

(06) Reserpine versus placebo

Measured by Addiction Severity Index One study (Winhusen 2007), 119 participants, see Analysis 6.3, MD 0.00 (95% CI ‐0.03 to 0.03) found no statistically significant difference.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Reserpine versus placebo, Outcome 3 Severity of dependence (Addiction Severity Index).

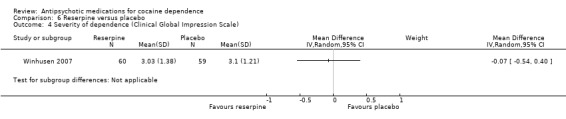

Measured by Clinical Global Impression Scale The same study (Winhusen 2007), 119 participants, see Analysis 6.4, presented similar results using another scale: MD ‐0.07 (95% CI ‐0.54 to 0.40).

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Reserpine versus placebo, Outcome 4 Severity of dependence (Clinical Global Impression Scale).

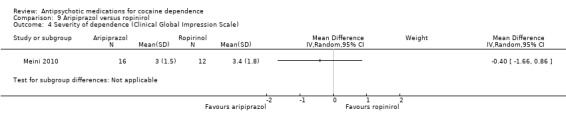

(09) Aripiprazol versus ropinirol

Measured by Clinical Global Impression Scale

One study (Meini 2010), 28 participants, also reported statistically non‐significant results for addiction severity: MD ‐0.40 (95% CI ‐1.66 to 0.86). See Analysis 9.4.

9.4. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Aripiprazol versus ropinirol, Outcome 4 Severity of dependence (Clinical Global Impression Scale).

Amount of cocaine use

(01) Any antipsychotic versus placebo

Measured by grams used during the last week

Two studies (Brown 2010; Tapp 2015), 72 participants, MD ‐0.54 (95% CI ‐0.92 to ‐0.16), see Analysis 1.8, showed a small statistically significant reduction in self‐reported grams of cocaine used during the past week in the antipsychotic treatment group. But again, the result is limited by the small sample size of the included studies.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antipsychotic versus placebo, Outcome 8 Use of cocaine during the treatment (self‐reported as g/week).

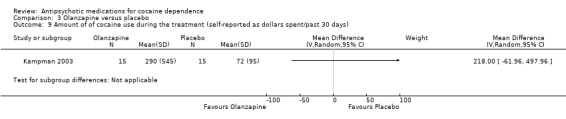

(03) Olanzapine versus placebo

Measured by money (US dollars) spent during past 30 days

One study(Kampman 2003), 30 participants, MD 218 (95% CI ‐61.96 to 497.96), see Analysis 3.9, showed no significant difference.

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Olanzapine versus placebo, Outcome 9 Amount of of cocaine use during the treatment (self‐reported as dollars spent/past 30 days).

(04) Quetiapine versus placebo

Measured by grams used during the last week

Two studies (Brown 2010; Tapp 2015), 72 participants, showed a very small statistically significant difference in favour of quetiapine when comparing the amount of cocaine use by grams per week: MD ‐0.54 (95% CI ‐0.92 to ‐0.16), see Analysis 4.5.

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Quetiapine versus placebo, Outcome 5 Amount of of cocaine use during the treatment (self‐reported as g/week).

Measured by money (US dollars) spent during the last week

One of these studies (Tapp 2015), 60 participants, also measured the amount of cocaine use by US dollars spent per week and found results in favour of quetiapine: MD ‐53.80 (95% CI ‐97.85 to ‐9.75), see Analysis 4.6. But the generalisability of this finding is low, due to the small sample size .

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Quetiapine versus placebo, Outcome 6 Amount of of cocaine use during the treatment (self‐reported as dollars spent/week).

(05) Lamotrigine versus placebo

One study (Brown 2012), 112 participants, using a declining‐effects random regression model, reported a statistically significant decrease in US dollars spent on cocaine in the lamotrigine group compared to the placebo group (F = 3.9, P = 0.05), as measured by the change from week 1 to week 12.

(09) Aripiprazol versus ropinirol

Measured by grams of self‐reported cocaine consume per week One study (Meini 2010), 28 participants, see Analysis 9.5, shows a small statistically significant effect in favour of aripiprazol: MD: ‐1.20 (95% CI ‐1.86 to ‐0.54), but the generalisability is low due the very small sample size.

9.5. Analysis.

Comparison 9 Aripiprazol versus ropinirol, Outcome 5 Amount of of cocaine use during the treatment (self‐reported as g/week).

Psychiatric symptoms/psychological distress

Depression

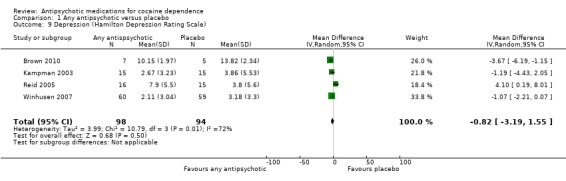

(01) Any antipsychotic versus placebo

Measured by Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

Four studies (Brown 2010; Kampman 2003; Reid 2005; Winhusen 2007), 192 participants, MD ‐0.82 (95% CI ‐3.19 to 1.55), see Analysis 1.9, showed a statistically non‐significant reduction in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores over the treatment periods in favour of antipsychotic treatment.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any antipsychotic versus placebo, Outcome 9 Depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale).

(02) Risperidone versus placebo

Measured by Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

One study (Loebl 2008) of 31 participants reported that no participants assigned to risperidone who completed the trial had an improvement in depressive symptoms. There was a mean increase in HAM‐D scores in the risperidone group of 7.4 (SD 8.8) and in the placebo group a decrease of ‐2.3 (SD 5.8,P = 0.018).

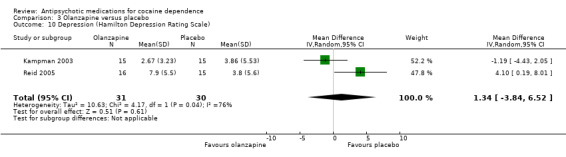

(03) Olanzapine versus placebo

Measured by Hamilton Depression Rating Scale Two studies (Kampman 2003; Reid 2005), 61 participants, see Analysis 3.10, MD 1.34 (95% CI ‐3.84 to 6.52; I² = 76%). No significant difference found, but heterogeneity was extremely high.

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Olanzapine versus placebo, Outcome 10 Depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale).

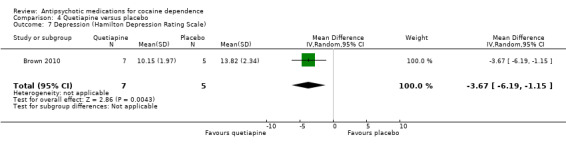

(04) Quetiapine versus placebo

Measured by Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

One small trial (Brown 2010) of 12 participants, see Analysis 4.7, MD ‐3.67 (95% CI ‐6.19 to ‐1.15) obtained results favouring quetiapine in reducing HAM‐D mean scores, but the very small sample size limits generalisability.

4.7. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Quetiapine versus placebo, Outcome 7 Depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale).

Measured by Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology‐SR

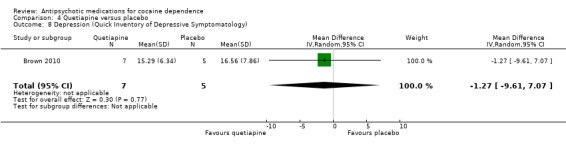

One small trial (Brown 2010) of 12 participants, see Analysis 4.8, MD ‐1.27 (95% CI ‐9.61 to 7.07) showed no statistically significant difference.

4.8. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Quetiapine versus placebo, Outcome 8 Depression (Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology).

(05) Lamotrigine versus placebo

Measured by Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology‐SR

One study (Brown 2012), 112 participants,using a declining‐effects random regression model, reported no differences in score changes between groups in depressive symptoms measured by HAM‐D (F = 0.3, P = 0.57) and QIDS‐SR (F = 0.1, P = 0.89) from week 1 to week 12.

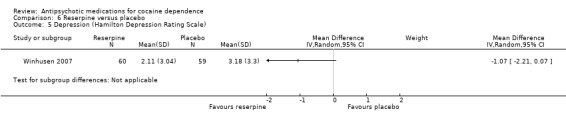

(06) Reserpine versus placebo

Measured by Hamilton Depression Rating Scale One study (Winhusen 2007), 119 participants, see Analysis 6.5, MD ‐1.07 (95% CI ‐2.21 to 0.07) No significant difference found,

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Reserpine versus placebo, Outcome 5 Depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale).

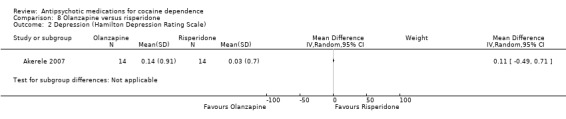

(08) Olanzapine versus risperidone

Measured by Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

One study (Akerele 2007), 28 participants, see Analysis 8.2, showed no significant differences: MD 0.11 (95% CI ‐0.49 to 0.71).

8.2. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Olanzapine versus risperidone, Outcome 2 Depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale).

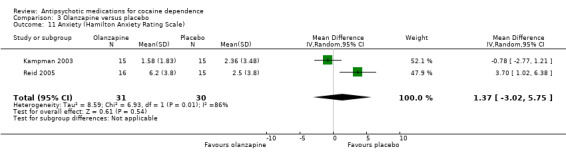

Anxiety

(03) Olanzapine versus placebo

Measured by Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale Two studies (Kampman 2003; Reid 2005), 61 participants, see Analysis 3.11, MD 1.37 (95% CI ‐3.02 to 5.75; I² = 86%) showed no significant difference, but heterogeneity was extremely high.

3.11. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Olanzapine versus placebo, Outcome 11 Anxiety (Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale).

Psychopathology

(02) Risperidone versus placebo

Measured by Snaith‐Hamilton Pleasure Scale

One study (Loebl 2008), 31 participants, reported no effect of treatment.

(04) Quetiapine versus placebo

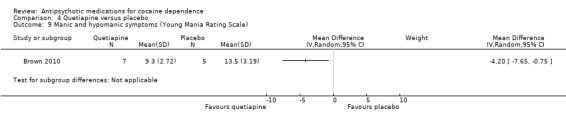

Measured by Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)

One small trial (Brown 2010) of 12 participants, see Analysis 4.9, MD ‐4.20 (95% CI ‐7.65 to ‐0.75) obtained results favouring quetiapine in reducing YMRS mean scores, but the small sample size limits generalisability.

4.9. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Quetiapine versus placebo, Outcome 9 Manic and hypomanic symptoms (Young Mania Rating Scale).

(05) Lamotrigine versus placebo

Measured by Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS)

One study (Brown 2012), 112 participants, using a declining‐effects random regression model, reported no differences in treatment effect between groups in manic and hypomanic symptoms (F = 0.5, P = 0.47) as measured by the change from week 1 to week 12.

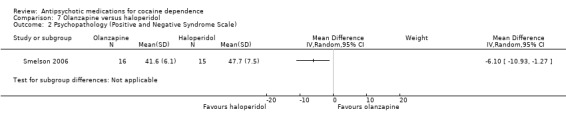

(07) Olanzapine versus haloperidol

Measured by Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) One study (Smelson 2006), 31 participants, see Analysis 7.2, MD ‐6.10 (95% CI ‐10.93 to ‐1.27) showed results favouring haloperidol in reducing scores, but the small sample size limits generalisability.

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Olanzapine versus haloperidol, Outcome 2 Psychopathology (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale).

(08) Olanzapine versus risperidone

Measured by Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

The Akerele 2007 study found a decrease in severity on the positive subscale over time for both groups (Z = 2.53, P = 0.01), but found no statistically significant differences between groups (Z = 0.49, P = 0.62) and no decrease in severity for the negative subscale over time (Z = 0.34, P = 0.73).

Withdrawal symptoms

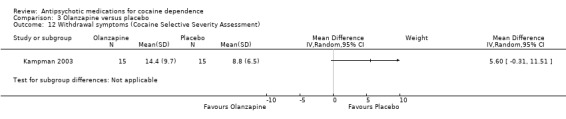

(03) Olanzapine versus placebo

Measured by Cocaine Selective Severity Assessment

One study (Kampman 2003), 30 participants see Analysis 3.12, MD 5.60 (95% CI ‐0.31 to 11.51) found no statistically significant difference in withdrawal symptoms between groups.

3.12. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Olanzapine versus placebo, Outcome 12 Withdrawal symptoms (Cocaine Selective Severity Assessment).

Discussion

Summary of main results

We include 14 trials. They tested risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, lamotrigine, reserpine, haloperidol and aripiprazol as antipsychotic agents for the treatment of cocaine dependence, comparing them with placebo and in three studies (Akerele 2007; Meini 2010; Smelson 2006) comparing two drugs.

Comparing any antipsychotic drugs versus placebo, we found moderate‐quality evidence that antipsychotics reduced dropouts; these findings came from eight studies with 397 participants (Brown 2010; Grabowski 2004; Kampman 2003; Levin 1999; Loebl 2008; Smelson 2004; Tapp 2015; Winhusen 2007). There were no significant differences for any of the other primary outcomes: number of participants using cocaine during the treatment (as days/week by urine tests or self report): continuous abstinence (number of participants who maintained negative drug screens for two to three weeks), and side effects (number of participants with at least one side effect), but the evidence was low and came from only two, three and four studies respectively. We also found low‐quality evidence showing no difference in craving as assessed by the BSCS, but these results are based on only four studies with 240 participants (Kampman 2003; Reid 2005; Tapp 2015; Winhusen 2007). The single comparisons of each drug versus placebo or versus another drug included few trials with small sample sizes, so limiting the reliability of the results. Among these comparisons, only quetiapine seemed to perform better than placebo in reducing cocaine use as measured by grams per week or US dollars spent per week, and in levels of craving assessed by the BSCS. These results came only from two studies, one with 60 participants (Tapp 2015) and another with 20 participants (Brown 2010).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Thirteen of the 14 included studies were conducted in the USA; this limits the generalisability of the results, because health effects of various substances of abuse seem to be strongly dependent on social context, and the location of the conduct of the studies could act as an effect modifier in the estimation of the efficacy of treatment.

Most of the included studies did not report useful results on important outcomes such as side effects, use of cocaine during the treatment and craving. In those studies which did report them, it was not possible to undertake a cumulative analysis because of the great heterogeneity of the scales used in the primary studies and in the way in which results are reported.

Quality of the evidence

The major limitations of the studies were the high risk of attrition bias (40% of the included studies) and the low quality of reporting, mainly affecting the risk of selection bias, and performance and detection bias, which we rated as being at unclear risk for 75% to 80% of the studies. Overall we rated study quality as moderate for dropouts, and low for the other outcomes

Potential biases in the review process

Risk of publication bias by Funnel plot could not be assessed because less than ten trials were included in the analysis. We performed a very comprehensive search and contacted investigators to request information about unpublished or incomplete trials. However, publication bias could not be excluded because only small studies have been included in the analyses.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The argument in favour of antipsychotics for treating cocaine use disorders is based largely on their use in treating psychiatric complications, which is not the same as treating the use disorder itself. Antipsychotics are not risk‐free medications; their side effects are not trivial and may be long‐lasting. We have not found positive effects on reduction in cocaine use. At present, there is no evidence supporting the clinical use of antipsychotic medications in the treatment of cocaine dependence, although results come from only 14 trials, with small sample sizes and moderate‐to‐low quality of evidence.

Implications for research.

Most of the included studies did not report useful results on important outcomes such as side effects, use of cocaine during the treatment, and craving. When studies did report them, no cumulative analysis was possible due to great heterogeneity among the scales used by the primary studies and in the way results were reported. This major problem needs to be addressed in future research through the use of instruments that allow for improved comparability of results and by following best‐practice recommendations for the reporting of results (i.e. GRADE).

Given the absence of promising results for reduction of drug use and the relevance of side effects, no further research seems to be justified to explore the effectiveness of this class of drug in people without psychiatric comorbidities or complications.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 June 2016 | Amended | added information about source of support |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 1, 2007 Review first published: Issue 3, 2007

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 7 February 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Conclusions not changed. |

| 7 February 2016 | New search has been performed | Searches updated. |

| 20 October 2008 | Amended | Contact details updated |

| 21 March 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 10 May 2007 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

Blanca I Indave undertook this update as her trainee's project at the EMCDDA under supervision of Marica Ferri. We would like to thank Marica Ferri for her support in particular on the assessment of the quality of the studies.We would like to acknowledge the previous contributions of Marina Davoli who was a co‐author on previous versions and helped with liaison on discussion and results writing. We thank Zuzana Mitrova, the trial search co‐ordinator, for her help in performing the bibliographic searches and retrieving the articles for the review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies October 2006

In the first version of the review we identified relevant studies by searching the following sources from the earliest available date to 2006: MEDLINE (1966 toOctober 2006), EMBASE (1980 to October 2006), CINAHL (1982 to October 2006), Cochrane Drug and Alcohol Group Specialised Register (October 2006)

MEDLINE search strategy

1.exp cocaine‐related disorders/ 2.((cocaine$) adj2 (abuse$ or addict$ or dependen$)).ti,ab 3.exp cocaine/ or exp crack cocaine/ 4.cocaine.ti,ab 5.1 or 2 or 3 or 4 6.exp antipsychotic/ 7.antipsychotic$.ti,ab 8.exp serotonin antagonists/ 9.5‐HT2$.ti,ab 10.chlorpromazine.mp. or exp Chlorpromazine/ 11.fluphenazine.mp. or exp Fluphenazine/ 12.perphenazine.mp. or exp Perphenazine/ 13.prochlorperazine.mp. or exp Prochlorperazine/ 14.thioridazine.mp. or exp Thioridazine/ 15.trifluoperazine.mp. or exp Trifluoperazine/ 16.haloperidol.mp. or exp Haloperidol/ 17.droperidol.mp. or exp Droperidol/ 18.pimozide.mp. or exp Pimozide/ 19.clozapine.mp. or exp Clozapine/ 20.olanzapine.mp. 21.risperidone.mp. or exp Risperidone/ 22.quetiapine.mp. 23.ziprasidone.mp. 24.aripiprazole.mp. 25.symbax.ti,ab. 26.tetrabenazine.mp. or exp Tetrabenazine/ 27. OR 6/26 28. 5 and 27 combined with the phases 1 & 2 of the Cochrane Sensitive Search Strategy for the identification of RCTs as published in Appendix 5b2, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions: 29.randomized controlled trial.pt. 30.randomized controlled trials/ 31.controlled clinical trial.pt. 32.random allocation/ 33.double blind method/ 34.single blind method/ 35.29/34 36.clinical trial.pt. 37.exp clinical trials/ 38.(clin$ adj trial$).ab,ti. 39.((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj (blind$ or mask$)).ab,ti 40.exp PLACEBOS/ 41.placebo$.ab,ti 42.random$.ab,ti 43.exp Research Design/ 44.36/43 45.35 or 44 46.4 and 7 and 12 47.30 and 29 48.limit 31 to human

EMBASE search strategy

exp drug abuse/

exp Cocaine Dependence/

((cocaine) adj2 (abuse$ or addict$ or dependen$)).ti,ab.

((drug or substance) adj2 (abuse$ or addict$ or dependen$)).ti,ab.

1 or 2 or 3 or 4

exp COCAINE DERIVATIVE/ or exp COCAINE/

cocaine.ti,ab.

6 or 7

antipsychotic.mp.

serotonin agents.mp. or exp Serotonin Receptor Affecting Agent/

exp CHLORPROMAZINE/ or chlorpromazine.mp.

fluphenazine.mp. or exp FLUPHENAZINE/

perphenazine.mp. or exp PERPHENAZINE/

exp PROCHLORPERAZINE/ or prochlorperazine.mp.

thioridazine.mp. or exp THIORIDAZINE/

exp TRIFLUOPERAZINE/ or trifluoperazine.mp.

haloperidol.mp. or exp HALOPERIDOL/

exp DROPERIDOL/ or droperidol.mp.

pimozide.mp. or exp PIMOZIDE/

clozapine.mp. or exp CLOZAPINE/

exp OLANZAPINE/ or olanzapine.mp.

risperidone.mp. or exp RISPERIDONE/

quetiapine.mp. or exp QUETIAPINE/

ziprasidone.mp. or exp ZIPRASIDONE/

aripiprazole.mp. or exp ARIPIPRAZOLE/

symbax.ti,ab.

tetrabenazine.mp. or exp TETRABENAZINE/

OR 9/27

5 and 8 and 28

random$.ti,ab.

placebo$.ti,ab.

((singl$ or doubl$ or trebl$ or tripl$) adj2 (blind$ or mask$)).mp.

(cross‐over$ or crossover$).tw.