Abstract

Background

Acute post-ablation pericarditis is the most common complication of epicardial ablation of ventricular arrhythmias, while regional pericarditis following an initially uneventful endocardial catheter ablation (CA) procedure is a rare and elusive diagnosis.

Case summary

We report a case of a 66-year-old Russian female who developed chest pain accompanied by electrocardiogram (ECG) changes—biphasic T waves in V1–V4 leads after an initially uncomplicated premature ventricular complex CA procedure. After examination and investigations, including transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) and cardiac computed tomography (CCT), she was diagnosed with regional pericarditis, which occurred even though the ablation was uneventful with the limited number of radiofrequency applications. Furthermore, the diagnosis was difficult due to normal body temperature and the absence of pericardial effusion and myocardial abnormalities on TTE, findings that are not characteristic of pericarditis. The patient’s last office visit was in 6 months after the procedure. Neither patient had any complaintsnor there were any changes on ECG and TTE.

Discussion

Regional post-ablation pericarditis is a relatively rare type of post-cardiac injury syndrome (PCIS). The varying severity of the PCIS clinical course makes the diagnosis of post-ablation pericarditis initially difficult, especially in patients undergoing an uneventful CA procedure. Non-invasive imaging modalities as CMR and CCT should be considered initially in elusive cases of PCIS.

Keywords: Post-ablation pericarditis, Regional injury, Cardiac magnetic resonance, Radiofrequency ablation, Premature ventricular complex, Case report

Learning points.

Post-ablation cardiac injury syndrome may occur after a routine, uneventful shot-wise catheter ablation procedure.

The localized character of the injury limits the systemic manifestations of post-cardiac injury syndrome and makes the diagnosis of regional pericarditis elusive.

Non-invasive cardiac imaging modalities such as cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and cardiac computed tomography help distinguish an initial diagnosis of regional pericarditis and avoid the performance of unnecessary emergency invasive procedures.

Introduction

Catheter ablation (CA) of ventricular arrhythmias is a safe and effective treatment option, especially for patients with frequent, symptomatic premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) originating in the ventricular outflow tracts.1 The rate and pattern of the procedure-related complications vary broadly depending on the CA approach, access, underlying heart disease.2–4 Acute post-ablation pericarditis is the most common complication of epicardial CA,5 while pericarditis following the uneventful endocardial CA is relatively rare and difficult to diagnose. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) and cardiac computed tomography (CCT) allow better visualization of the heart and pericardium and should be considered in elusive cases.6,7 We present a regional pericarditis case after successful uneventful right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) PVC ablation.

Timeline

| September 2019 | Detection of frequent, symptomatic, monomorphic premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) on the 24 h of electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring. |

| 25 May 2020 | Uneventful shot-wise radiofrequency ablation of right ventricular outflow tract (RVOT) PVCs. |

| 27 May 2020 | The patient developed chest pain. Electrocardiogram revealed—biphasic T waves in V2–V4 leads. Transthoracic echocardiography did not reveal any signs of pericardial effusion or local myocardial abnormalities. |

| 27 May 2020 | Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging showed local accumulation of pericardial fluid in front of the RVOT anterior wall, adjacent oedema, and pericardial contrast enhancement and the diagnosis of local post-ablation pericarditis was confirmed. Non-steroid anti-inflammation drug therapy was started. |

| 1 June 2020 | Chest pain and ECG changes regression. However, cardiac computed tomography revealed a loculated pericardial effusion anterior to the right ventricle on the length of 2.5 cm and a 7 mm separation of pericardial layers. |

| Six months after ablation | Normal ECG, no episodes of chest pain or discomfort |

Case presentation

A 66-year-old Russian female was referred to our clinic for dull oppressive non-radiating retrosternal chest pain occurring on the 2nd day post-ablation. The patient had undergone an uneventful RVOT radiofrequency ablation 2 days earlier for frequent (>22 000 per day), drug-resistant (bisoprolol, sotalol, and propafenone) PVC due to frequent symptoms of skipped beats, palpitations accompanied by dizziness, light-headedness, and exertional dyspnoea. The patient also reported a history of well-controlled arterial hypertension (treated with the combination of enalapril and hydrochlorothiazide) and diabetes mellitus (treated with metformin), class 1 obesity (body mass index 33 kg/m2).

Activation and pace mapping techniques were used to localize the PVC source. The earliest focal endocardial activation was detected in the RVOT anteroseptal wall 1 cm below the pulmonary valve. Power-controlled, open-irrigated tip radiofrequency applications were performed in this area leading to PVC elimination. The temperature was limited to 44°C, the power output was 40 W, and the total radiofrequency ablation (RFA) duration was 300 s.

On readmission, the physical examination was unremarkable: the blood pressure was 125/80 mmHg, heart rate 75 b.p.m., respiratory rate 18, oxygen saturation 100% on room air. Heart sounds were muffled, without any heart murmurs (including pericardial rub); the second sound was accentuated in the aortic area during cardiac auscultation. Lungs were clear to auscultation with no crackles or wheezes.

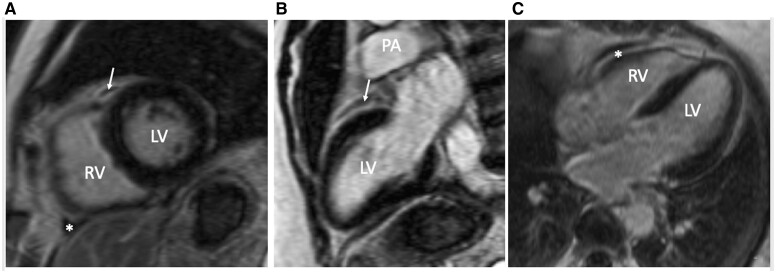

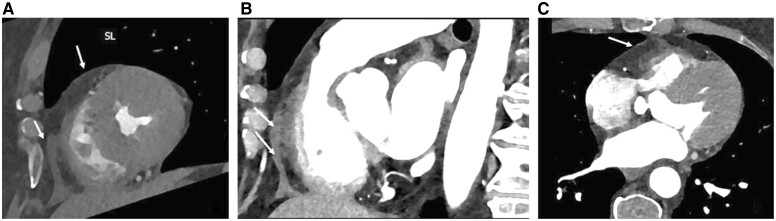

Twelve lead electrocardiogram (ECG) at the time of presentation showed biphasic T waves in V1–V4 (Figure 1A and B). Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) did not reveal any signs of pericardial effusion or local myocardial abnormalities. Complete blood count did not show any abnormal changes. The high-sensitive C-reactive protein level was 3.38 mg/L (normal ranges: 1–3 mg/L). The measurement of cardiac troponin level was inappropriate due to the expected post-ablation elevation of cardiac biomarkers. The CMR showed local accumulation of pericardial fluid in front of the RVOT anterior wall, accompanied by adjacent oedema and pericardial contrast enhancement (Figure 2). The only significant finding on CCT, performed for comprehensive coronary anatomy assessment, was loculated pericardial effusion anterior to the right ventricle on the length of 2.5 cm and a 7 mm separation of pericardial layers (Figure 3) which corresponds to changes detected by CMR. There were no signs of coronary artery injury significant coronary artery disease.

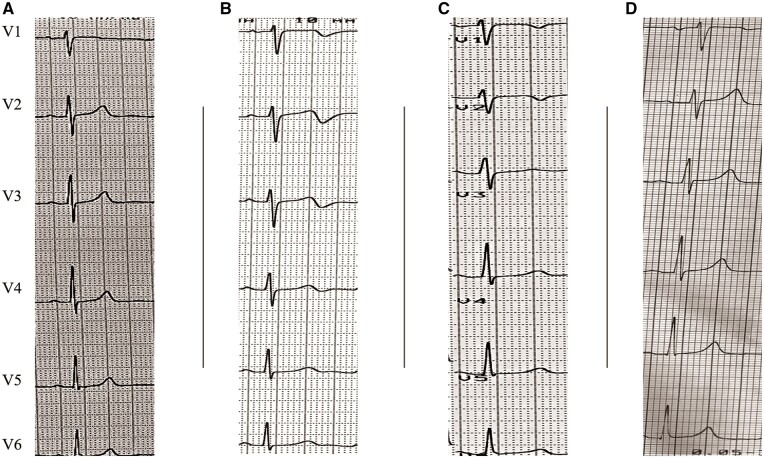

Figure 1.

Precordial leads of pre- and post-ablation electrocardiograms showing the dynamics of electrocardiogram changes in V1–V4 leads. (A) Pre-ablation electrocardiogram with biphasic T wave in I lead and positive T waves in V2–V4 leads; (B) electrocardiogram on 2nd post-ablation day at the time of chest pain presentation revealed biphasic T waves in V1–V4; (C) electrocardiogram on the 7th post-ablation day shows regression of T wave changes; (D) electrocardiogram during 6 months of follow-up revealed complete regression of T wave changes.

Figure 2.

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging with late gadolinium enhancement: (A) cardiac short-axis view; (B) long-axis two-chamber view; (C) long-axis four-chamber view. A small local lens-like collection of pericardial fluid in front of right ventricular outflow tract is marked with arrows. Focal enhancement of adjacent pericardial layers is marked with an asterisk. LV, left ventricle; PA, pulmonary artery; RV, right ventricle; RVOT, right ventricle outflow tract.

Figure 3.

Cardiac computed tomography, multiplanar reconstructions (A) short-axis view; (B) right ventricular outflow tract view; (C) long-axis four-chamber view. Arrows indicate a small focal collection of pericardial fluid in the right ventricular outflow tract and right ventricular free wall. RV, right ventricle.

A non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug therapy (Diclofenac sodium 75 mg/daily for injection was chosen due to reported aspirin and ibuprofen allergy) was started. Both chest pain and ECG changes regressed shortly after anti-inflammatory therapy initiation (Figure 1C). Therefore, anti-inflammatory therapy was discontinued in 3 days. There were no adverse effects associated with the therapy; the patient did not have any complaints or symptoms and was discharged within 5 days.

Discussion

We reported a case of regional pericarditis occurring on the 2nd day following an initially uncomplicated PVC RFA procedure. Regional post-ablation pericarditis is a rare type of post-cardiac injury syndrome (PCIS). Immune-mediated inflammation secondary to initial cardiac injury seems the most likely mechanism of PCIS.8 The myocardial injury itself or direct thermal injury in the pericardium initiates inflammation, leading to variable clinical presentations—from localized pericarditis, as in our case, to massive pleuropericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade.9 Most reported PCIS cases are related to cardiac perforation,8 and PCIS, occurring after initially uncomplicated endocardial CA procedures,10–15 is predominantly associated with extended linear ablation lesions. On the other hand, the varying severity of the clinical course of PCIS (Table 1) makes the initial diagnosis of post-ablation pericarditis difficult and usually requires a differential diagnosis of a coronary event. In our case, the absence of a history of coronary artery disease (negative exercise stress test 2 months before ablation), normal TTE data, uncomplicated course of RVOT spot-wise RFA makes the ECG changes and chest pain unlikely to be of ischaemic origin.

It is also credible that iatrogenic right ventricle (RV) perforation related to PVC ablation might be responsible for this case. However, most iatrogenic cardiac perforation cases occur intraprocedural/during the first post-ablation hours and/or after 1–2 weeks (inflammation associated cases) and present mainly with haemodynamic deterioration. So analysing the time course and clinical pattern of the event in our patient, we discounted the possibility of iatrogenic RV wall perforation.

Thus, although the limited number of radiofrequency applications, normal body temperature, and the absence of pericardial effusion and myocardial abnormalities on TTE made the diagnosis of post-ablation cardiac injury less likely, we assumed that chest pain, ECG changes were due to post-ablation myocardial ‘oedema’ leading to regional pericarditis. The absence of systemic reaction was due to the localized character of the injury. Thus, we suggested that the patient developed regional PCIS, and the localized character of the injury had limited the systemic manifestations of the inflammation. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging and CCT confirmed our assumptions. Considering the superiority of CMR in evaluating cardiac anatomy and depicting pericardium,7 these non-invasive imaging modalities should be considered initially in elusive cases of PCIS.

The patient’s last office visit was in 6 months after the procedure. The patient did not have any complaints or symptoms, and there were no abnormalities on their ECG (Figure 1D) or TTE.

Conclusion

The possibility of the PCIS following even a routine, uneventful CA procedure should always be considered. A thorough analysis of clinical signs and symptoms with CMR and CCT performance helps make an initial diagnosis of regional pericarditis and avoid the performance of unnecessary emergency invasive procedures.

Lead author biography

Dr Karapet V. Davtyan is a cardiac surgeon specialized in the interventional treatment of cardiac arrhythmias in adults and children. He works as a Head of the Department of Heart Rhythm and Conduction Disorders at the National Medical Research Center for Therapy and Preventive Medicine in Moscow. He and his team perform more than 800 ablation cases per year.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal - Case Reports online.

Slide sets: A fully edited slide set detailing this case and suitable for local presentation is available online as Supplementary data.

Consent: The authors confirm that written consent for submission and publication of this case report including images and associated text has been obtained from the patient in line with COPE guidance.

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Funding: None declared.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Cronin EM, Bogun FM, Maury P, Peichl P, Chen M, Namboodiri N. et al. 2019 HRS/EHRA/APHRS/LAHRS expert consensus statement on catheter ablation of ventricular arrhythmias. Heart Rhythm 2020;17:e2–e154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ling Z, Liu Z, Su L, Zipunnikov V, Wu J, Du H. et al. Radiofrequency ablation versus antiarrhythmic medication for treatment of ventricular premature beats from the right ventricular outflow tract: prospective randomized study. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2014;7:237–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Carrigan TP, Patel S, Yokokawa M, Schmidlin E, Swanson S, Morady F. et al. Anatomic relationships between the coronary venous system, surrounding structures, and the site of origin of epicardial ventricular arrhythmias. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2014;25:1336–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Latchamsetty R, Yokokawa M, Morady F, Kim HM, Mathew S, Tilz R. et al. Multicenter outcomes for catheter ablation of idiopathic premature ventricular complexes. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2015;1:116–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tarantino N, Della Rocca DG, Faggioni M, Zhang X-D, Mohanty S, Anannab A. et al. Epicardial ablation complications. Card Electrophysiol Clin 2020;12:409–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hundley WG, Bluemke DA, Finn JP, Flamm SD, Fogel MA, Friedrich MG. et al. ; American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. ACCF/ACR/AHA/NASCI/SCMR 2010 expert consensus document on cardiovascular magnetic resonance: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010;55:2614–2662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bogaert J, Francone M.. Pericardial disease: value of CT and MR imaging. Radiology 2013;267:340–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li W, Sun J, Yu Y, Wang Z-Q, Zhang P-P, Guo K. et al. Clinical features of post cardiac injury syndrome following catheter ablation of arrhythmias: systematic review and additional cases. Heart Lung Circ 2019;28:1689–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Imazio M, Hoit BD.. Review: post-cardiac injury syndromes. An emerging cause of pericardial diseases. Int J Cardiol 2013;168:648–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koller ML, Maier SKG, Bauer WR, Schanzenbächer P.. Postcardiac injury syndrome following radiofrequency ablation of atrial flutter. Z Kardiol 2004;93:560–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zheng LR, Hu X, Xia S, Chen Y.. Postcardiac injury syndrome following radiofrequency ablation of idiopathic left ventricular tachycardia. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2007;18:269–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zheng MF, Wang Z, Bao ZY.. Myocardial injury and pericarditis after combined left atrial and coronary sinus ablation in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: a case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2020;20:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Orme J, Eddin M, Loli A.. Regional pericarditis status post cardiac ablation: a case report. N Am J Med Sci 2014;6:481–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wood MA, Ellenbogen KA, Hall J, Kay GN.. Post-pericardiotomy syndrome following linear left atrial radiofrequency ablation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2003;9:55–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kibos A, Pacouret G, Babuty D, De Labriolle A, Fauchier L, Charbonnier B.. Postcardiac injury syndrome complicating radiofrequency ablation of the atrioventricular node. Acute Card Care 2006;8:122–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.