Abstract

Prime editor (PE), a new genome editing tool, can generate all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, insertion, and deletion of short fragment DNA. PE has the potential to correct the majority of known human genetic disease-related mutations. Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs), the safe vector widely used in clinics, are not capable of delivering PE (∼6.3 kb) in a single vector because of the limited loading capacity (∼4.8 kb). To accommodate the loading capacity of AAVs, we constructed four split-PE (split-PE994, split-PE1005, split-PE1024, and split-PE1032) using Rma intein (Rhodothermus marinus). With the use of a GFP-mutated reporter system, PE reconstituting activities were screened, and two efficient split-PEs (split-PE1005 and split-PE1024) were identified. We then demonstrated that split-PEs delivered by dual-AAV1, especially split-PE1024, could mediate base transversion and insertion at four endogenous sites in human cells. To test the performance of split-PE in vivo, split-PE1024 was then delivered into the adult mouse retina by dual-AAV8. We demonstrated successful editing of Dnmt1 in adult mouse retina. Our study provides a new method to deliver PE to adult tissue, paving the way for in vivo gene-editing therapy using PE.

Keywords: dual-AAV, prime editor, split, gene editing, in vivo

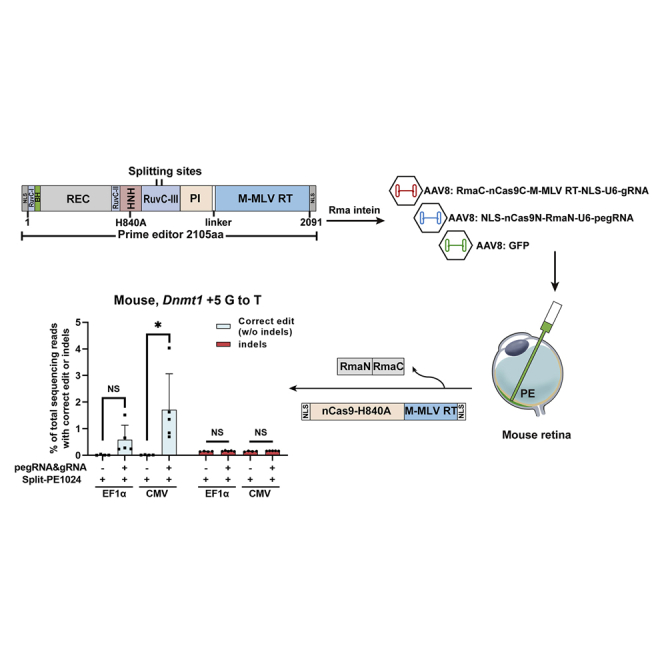

Graphical abstract

Huang and colleagues developed a dual-AAV split prime editor (split-PE) system reconstructed by Rma intein, resulting in an efficient editing endogenous gene in human cells and in adult mouse retina. The study provides a new method to deliver PE to adult tissue, paving the way for in vivo gene-editing therapy using PE.

Introduction

CRISPR-CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9), a novel genome-editing tool, guides site-specific DNA cleavage in the human genome under the guidance of a guide RNA (gRNA).1, 2, 3 In cells, double-strand break (DSB) at the target DNA site is then repaired by endogenous repair pathways, including non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and homology-directed repair (HDR),4,5 which allow the accurate “cutting and pasting” of DNA. However, HDR can be inefficient and needs exogenous templates.6,7 Then base editors, based on deaminase and Cas9 nickase (Cas9n), are developed and applied in many diseases caused by T > C or G > A mutations.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 However, base editors cannot currently correct transversion mutations, which account for about 20% of the >75,000 known disease-associated human genetic variants. In addition, the efficient method for installing targeted insertions or deletions that account for about 30% of known pathogenic human genetic variants is in demand.14 Recently, a new genome-editing tool, named the prime editor (PE), was developed. PE is capable of installing targeted insertions, deletions, and all 12 possible base-to-base conversions without inducing DSBs. PE, an RNA-protein complex, contains an effector protein composed of Cas9n-H840A and C-terminal reverse transcriptase (Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase [M-MLV RT]), and the RNA component of PE, named prime-editing extended gRNA (pegRNA), could accurately transmit genomic information from pegRNA to target locus with the help of the effector protein. Compared with base editors, PE permits not only single base editing but also insertions and deletions at target locus.14 Meanwhile, PE had been employed to repair the point mutation of sickle cell anemia (HBB p.E6V, c.20A > T),14 generate mutant mice with a point mutation (Hoxd13 p.G224A, c.671G > C),15 and edit the genome in mice16 in intestinal organoids,17 in Drosophila,18 and in plants.19

Delivering genome editing tools to the patients for in vivo genome-editing therapy is promising disease therapeutics. Viral systems, such as adeno-associated virus (AAV), lentivirus, and adenovirus, are important delivery vectors for gene therapy.12,20 Among these widely used systems, AAV has been demonstrated to be the safest and the most successful vector in the therapeutic application,21, 22, 23 which makes it a preferred tool for in vivo genome editing.12,22 Unfortunately, the loading capacity of AAV (∼4.8 kb) limits its application in delivering large genome-editing tools (e.g., base editors and PE).24,25

To tackle this issue, the effector protein of the base editor is split into two smaller parts (split-adenine base editor [ABE] and split-cytosine base editor [CBE]), which could be packaged into two separate AAVs. After infecting the cells, the two separated parts will be reconstructed into one active effector protein through two different mechanisms (RNA trans-splicing and intein-mediated protein trans-splicing). Split-ABE, reconstructed through RNA trans-splicing, shows a low A > G editing efficiency in the adult mouse muscle tissue.26 However, split-ABE, reconstructed by intein-mediated protein trans-splicing, edits the genome more efficiently in vivo.12,27 Intein, an autocatalytic internal protein domain, could catalyze self-splicing and ligation of the two flanking peptides to generate a full-length functional protein at the post-translational level. Besides ABE, intein has also been used in other oversized genome editors (e.g., Cas928,29 and CBE27,30). Rma intein from Rhodothermus marinus DnaB had been used in split-Cas9 with a 713−714 splitting site28 and split-ABE in both 573−574 and 674−675 splitting sites12 for in vivo genome editing using the dual-AAV system. Of notice, different splitting sites will affect the reconstituting activity owing to structural stability, resulting in different genome-editing efficiency.31 Rma intein has been demonstrated to be the best intein for reconstituting ABE.12 However, there is no study evaluating the effect and safety of different splitting sites of Cas9n for PE.

Thus, we developed a dual-AAV split-PE system for in vivo genome editing. First, we engineered and screened four different split-PE systems, based on Rma intein, using a GFP(green fluorescent protein)-based reporter cell. In addition, we observed successful installing of short insertion and point mutations at endogenous target sites, when split-PEs were introduced into cultured cells by either plasmid transfection or AAV infection. Furthermore, single-nucleotide transversion could be generated in vivo by injecting the dual-AAV split-PE into the adult mouse retina. Our findings suggest that dual-AAV split-PE is a feasible tool for targeted genome editing in vivo.

Results

GFP-mutated (GFPm) reporter screening of split-PEs

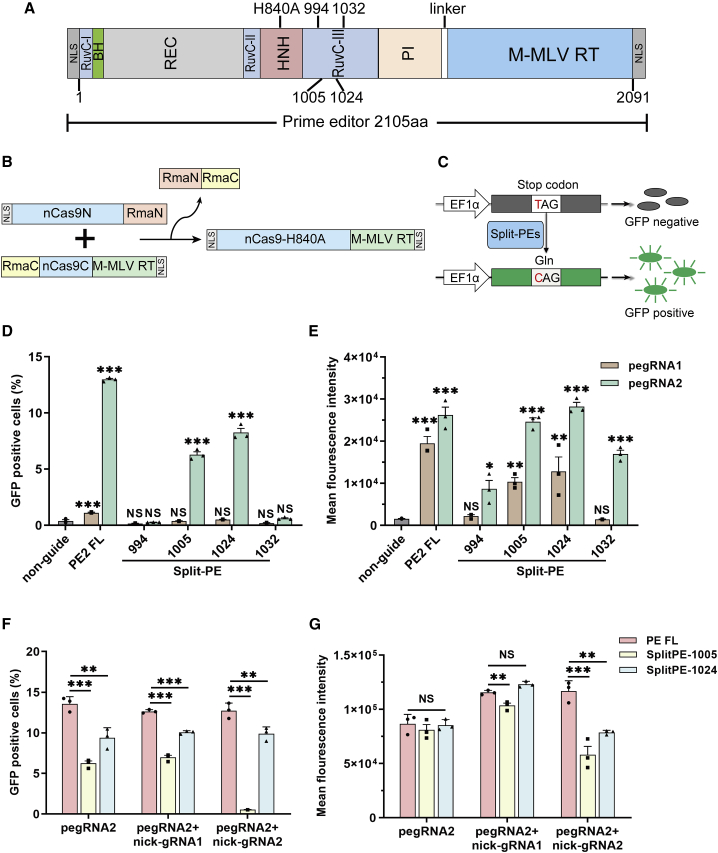

To accommodate the loading capacity of AAVs (∼4.8 kb) as well as the essential elements of the vector (promoter, terminator [poly(A)], intein, and U6-pegRNA/gRNA), we could only divide PE (∼6.3 kb) into two parts within a small region, which ranges from 990 (Asn) to 1,050 (Ile).14 More importantly, the inteinC at the C-terminal half of PE should be followed by cysteine, serine, or threonine residues,32 and then we found four sites (994−995 Thr, 1,005−1,006 Ser, 1,024−1,025 Ser, and 1,032−1,033 Thr in Cas9n-H840A) that satisfy the above two requirements. Then we divided the full-length PE into two parts at four different splitting sites (Figure 1A). The N-terminal half of PE was fused to the RmaN, whereas the C-terminal half of PE was fused to RmaC (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Efficient T-to-C editing by Split-PEs in the reporter cells

(A) Schematic of split-PEs split at four different sites (994−995, 1,005−1,006, 1,024−1,025, and 1,032−1,033). RuvC, endonuclease domain; BH, bridge helix; REC, recognition domain; HNH, His-Asn-His endonuclease domain; PI, protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM)-interacting domain; M-MLV RT, engineered Moloney murine leukemia virus (M-MLV) reverse transcriptase (D200N, L603W, T306K, W313F, T330P). (B) Schematic of Rma intein-mediated PE reconstitution through protein trans-splicing. (C) Reporter cell harbors a mutated GFP (GFPm) coding sequencing, containing a premature stop codon in the GFP coding sequence, downstream of the EF1α promoter. The GFP signal would be detected by flow cytometer when the TAG codon was converted to the CAG codon by split-PE. (D) The percentage of GFP-positive cells after different split-PE and pegRNA treatment. (E) The mean fluorescence intensity after different split-PE and pegRNA treatment. (F) The percentage of GFP-positive cells after varying split-PE3 treatment in GFPm reporter cells. (G) The mean fluorescence intensity after different split-PE3 and pegRNA2 treatment. non-guide, reporter cells transfected with full-length PE2 but not pegRNA. PE2 FL, reporter cells transfected with full-length PE2 and pegRNA. Values and error bars represent the mean ± SD of three independent biological repeats. One-way ANOVA is used for calculating statistical significance (NS, not significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

Meanwhile, we established a GFPm reporter cell line, containing a premature stop codon in the GFP coding sequence, to evaluate the prime-editing efficiency of these four split-PEs conveniently and quickly. The GFP signal would be detected by a flow cytometer when the TAG codon in GFP was converted to the CAG codon (Figure 1C).12 Taking advantage of this reporter cell, we could easily evaluate the editing efficiency of different split-PEs. First, we designed two pegRNAs, both with a 13-nucleotide (nt) primer binding site (PBS) and a 19-nt RT template (Figure S1). Then we tested the editing efficiency of these four split-PEs through transfecting cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter-driven split-PEs and U6 promoter-driven pegRNA plasmids into GFPm reporter cells. 72 h after transfection, the percentage of GFP-positive cells and the mean fluorescence intensity were calculated (Figures 1D and 1E; Figure S2). We observed high editing efficiencies using split-PE1005 and split-PE1024, which were split at 1,005−1,006 or 1,024−1,025, respectively (Figures 1D and 1E).

Compared with PE2, PE3 nicks the non-edited strand and shows increased editing efficiency at target sites.14 To probe the editing efficiency of split-PE3, we designed two gRNAs (nick-gRNA1 and nick-gRNA2) to nick the non-edited strand (Figure S1). Split-PE3, especially split-PE1024, showed robust high editing efficiency with nick-gRNA1 (Figures 1F and 1G; Figure S3). Meanwhile, we observed similar mean fluorescence intensity with split-PE1024, which was comparable to that of full-length PE3 (Figure 1G; Figure S3). These findings validated the feasibility of reconstituting split PE effector protein into one functional effector protein from two independent expression vectors through protein trans-splicing. We identified two efficient split-PEs (split-PE1005 and split-PE1024) with high prime-editing efficiency. Therefore, we focused on these split-PEs in further experiments.

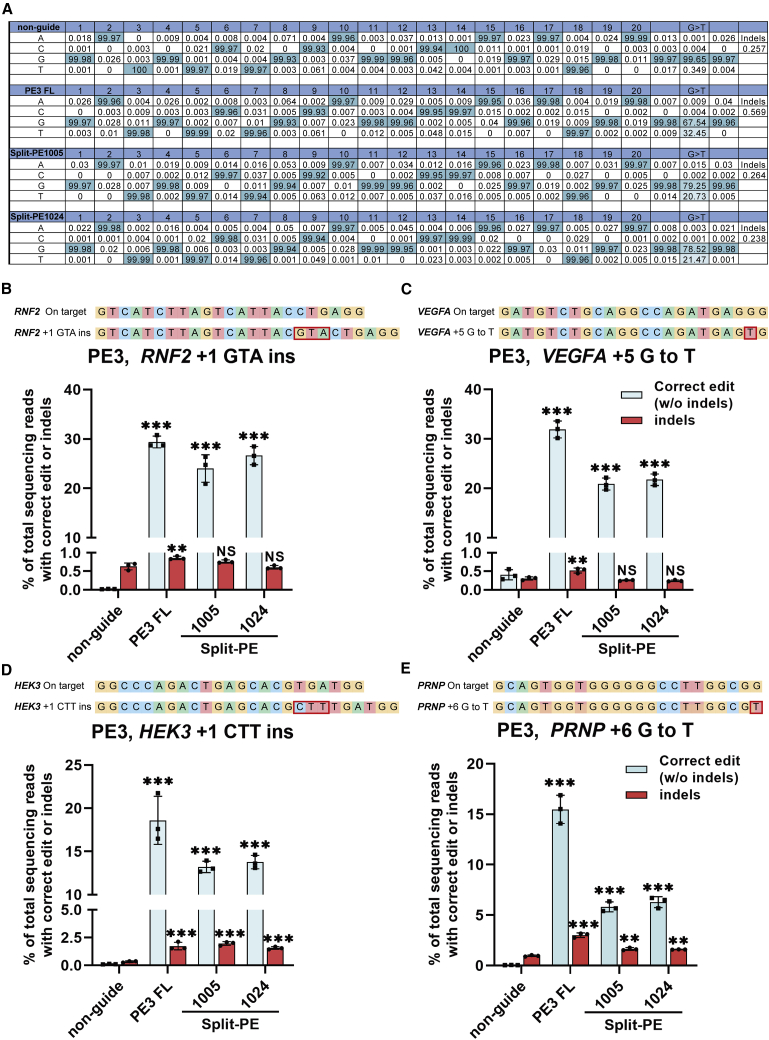

Efficient genome editing by split-PEs at endogenous sites in human cells

Inspired by the data above, we hypothesized that split-PEs might also install single-nucleotide transversion and indel mutations at endogenous target sites with high efficiency. We tested the editing efficiency of CMV promoter-driven split-PEs at four endogenous sites (RNF2 +1 GTA insertion [ins], VEGFA +5 G to T, HEK3 +1 CTT insertion [ins], and PRNP +6 G to T)14 in human HEK293T cells (Figure 2). The editing efficiency and indel rate were detected by next-generation sequencing (NGS) and analyzed by MATLAB8 and CRISPResso233 (Figure 2A). We found that both split-PE1005 or split-PE1024 splitting sites could induce efficient insertion and single-nucleotide transversion editing at all sites tested (Figures 2B−2E; Figure S4). Importantly, +1 GTA insertion was installed at the RNF2 site with similar efficiency using either split-PE1024 or full-length PE (26.62% versus 29.39%) (Figure 2B). However, there is a drop in efficiency at some gene sites using either split-PE1005 or split-PE1024 compared to full-length PE (Figures 2C−2E). These data indicate that split-PEs could catalyze insertion and single-nucleotide transversion efficiently at endogenous genomic sites in human cells. Importantly, split-PE1024 is a preferred split-PE that displays a higher editing efficiency.

Figure 2.

Prime editing of endogenous sites in HEK293T cells by split-PEs

(A) Example of deep-sequencing data analysis of G-to-T conversion at endogenous sites targeted by split-PEs. Single-nucleotide transversion editing efficiency was analyzed by MATLAB, whereas insertion editing efficiency and indel frequency were analyzed by CRISPResso2. (B) Targeted insertion of GTA at RNF2 in HEK293T. (C) Targeted transversion of G to T at VEGFA in HEK293T. (D) Targeted insertion of CTT at HEK3 in HEK293T. (E) Targeted transversion of G to T at PRNP in HEK293T. Editing efficiencies represent sequencing reads that contain the correct edit and do not contain indels among total sequencing reads. Indels were also plotted for comparison. non-guide, HEK293T cells transfected with full-length PE2 but not pegRNA. PE3 FL, HEK293T cells transfected with full-length PE2, pegRNA, and nick-gRNA. Values and error bars represent the mean ± SD of three independent biological repeats. One-way ANOVA was used for calculating statistical significance (∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

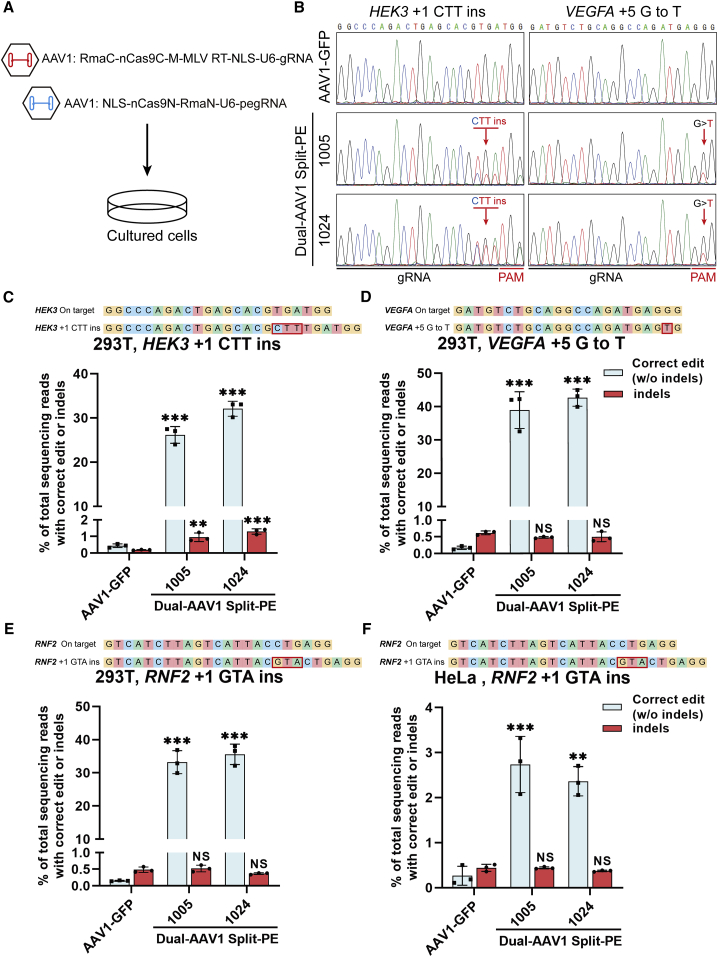

Prime editing in human cell lines through split-PEs delivered by dual-AAV

The results above verified the feasibility of split-PEs in human cells by plasmids transfection. However, whether split-PE could be delivered by AAV was still unknown. Our previous data suggested that AAV1 was an optimized AAV serotype suitable for infecting HEK293T and HeLa cells.12 Therefore, we packaged AAV1 carrying these two CMV promoter-driven split-PEs (split-PE1005 and split-PE1024) and infected HEK293T and HeLa cells with AAV1, of which the ratio between the N-terminal half and C-terminal half of PE was 1:1 (Figure 3A). We observed efficient editing of target sites in AAV1-infected HEK293T cells (Figure 3B). The editing efficiencies, further quantified by NGS, indicated that both split-PE1005 and split-PE1024 delivered by dual-AAV1 could induce efficient insertion and single-nucleotide transversion in HEK293T and HeLa cells (Figures 3C−3F). Importantly, we observed highly efficient prime editing for +1 CTT insertion at HEK3 in the HEK293T cell by split-PE1024 (32.08% ± 1.68% average efficiency and 1.29% ± 0.16% indels) and split-PE1005 (26.18% ± 1.89% average efficiency and 0.95% ± 0.25% indels) (Figure 3C). At the VEGFA locus, split-PE1024 delivered by dual-AAV1 installed +5 G-to-T transversion editing efficiently (42.65% ± 2.56%) with few indels (0.50% ± 0.15%), whereas split-PE1005 showed 38.92% ± 5.52% average efficiency and 0.48% ± 0.03% indels in HEK293T cells (Figure 3D). In addition, we observed obvious prime editing for +1 GTA insertion at the RNF2 site in HEK293T (35.59% ± 3.08% average efficiency and 0.37% ± 0.03% indels) and HeLa (2.36% ± 0.33% average efficiency and 0.37% ± 0.02% indels) cells with dual-AAV1-delivered split-PE1024, respectively. Meanwhile, split-PE1005 delivered by dual-AAV1 installed an efficient editing for +1 GTA insertion at the RNF2 site in HEK293T (33.22% ± 3.48% average efficiency and 0.52% ± 0.10% indels) and HeLa (2.73% ± 0.62% average efficiency and 0.44% ± 0.02% indels) cells (Figures 3E and 3F).

Figure 3.

Efficient editing of endogenous sites by dual-AAV split-PEs in human cells

(A) Schematic of split-PE delivered by dual-AAV1. N-terminal half and C-terminal half of split-PEs were packaged into two AAV1 separately, and then the cells were infected with both N-terminal half virus and C-terminal half virus, of which the ratio was 1:1. 5 days post-infection, cells were collected for sequencing. (B) Example of Sanger sequencing to detect editing at endogenous sites targeted by split-PEs. The red arrow indicates the edited site. (C) Targeted insertion of CTT at HEK3 in HEK293T cells. (D) Targeted transversion of G to T at VEGFA in HEK293T cells. (E) Targeted insertion of GTA at RNF2 in HEK293T cells. (F) Targeted insertion of GTA at RNF2 in HeLa cells. Editing efficiencies represent sequencing reads that contain the correct edit and do not contain indels among total sequencing reads, which were analyzed by MATLAB and CRISPResso2. Indels were plotted for comparison. AAV1-GFP, negative control. Values and error bars represent the mean ± SD of three independent biological repeats. One-way ANOVA was used for calculating statistical significance (∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001).

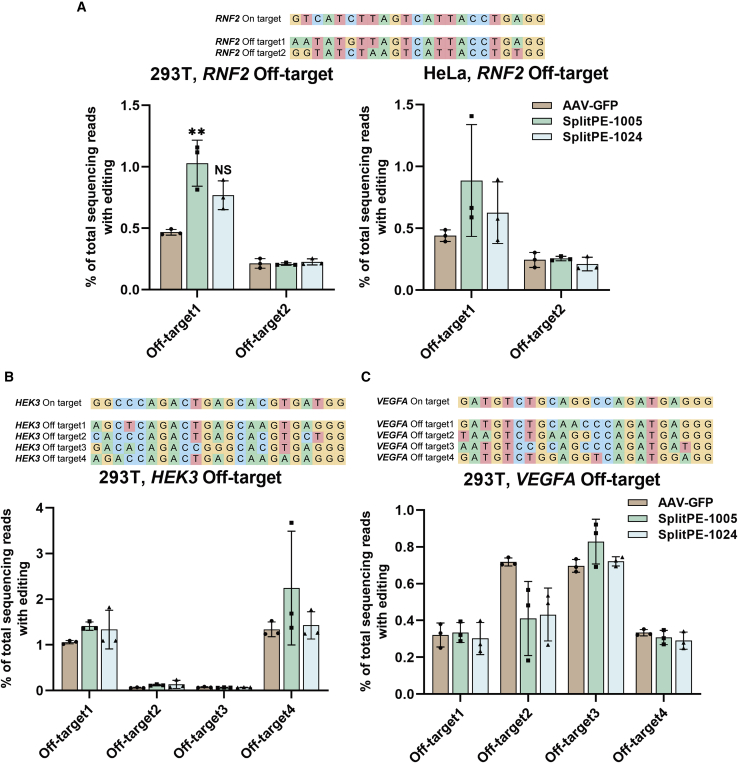

Meanwhile, to test whether prime editing would induce off-target editing, we amplified and detected the indel efficiency of off-target sites in the dual-AAV split-PE-infected cells. The indel rate (including all types of indels as well as base substitutions) of two known off-target sites of RNF2,34 four known top off-target sites of HEK3,14,35 and four predicted top off-target sites of VEGFA36,37 were detected by NGS. Intriguingly, compared to control (AAV1-GFP), split-PE1024 displayed no detectable indels at all off-target sites, suggesting its high safety and reliability (Figures 4A−4C).

Figure 4.

Off-target analysis of endogenous sites targeted by dual-AAV-delivered split-PEs in human cells

(A) Editing frequency of two known off-target sites of RNF2 in HEK293T and HeLa cells. (B) Editing frequency of four known top off-target sites of HEK3 in HEK293T cells. (C) Editing frequency of four predicted top off-target sites of VEGFA in HEK293T cells. The edits include all types of base substitutions as well as indels, which were analyzed by CRISPResso2. AAV1-GFP, negative control. Values and error bars represent the mean ± SD of three independent biological repeats. One-way ANOVA was used for calculating statistical significance (∗∗p < 0.01).

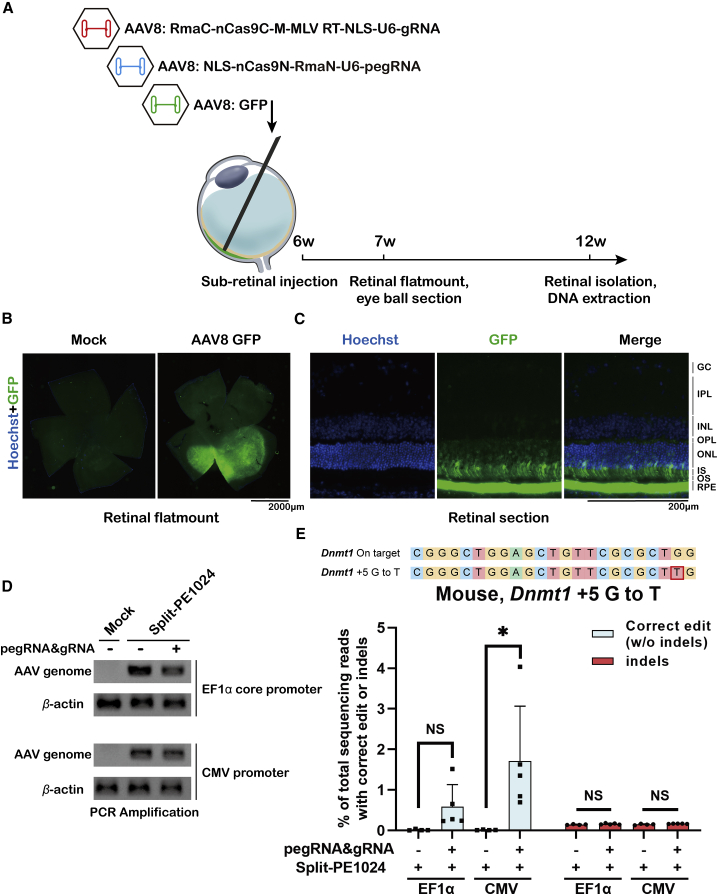

Single-nucleotide transversion in mouse retina by split-PE1024 delivered with AAV

The retina is a small and immune privilege organism that makes it an applicable target for AAV-mediated gene therapy.38,39 To test the feasibility of the editing target site by split-PE in vivo, dual-AAV8 split-PE1024 targeting Dnmt1 (p.P55Q, c.G164T) inducing +5 G-to-T transversion was injected into the adult mouse retina. A total of 1.1 × 1010 vector genome (vg) AAV8 (5 × 109 vg N-terminal half of split-PE1024 + 5 × 109 vg C-terminal half of split-PE1024 + 1 × 109 vg GFP) was injected into 6-week-old mouse eyes through sub-retinal injection (Figure 5A). 1 week post-injection, the mouse retina was isolated. The GFP signal could be observed around the injection site (Figure 5B). The majority of infected cells with GFP expression was limited to photoreceptors and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) (Figure 5C). 6 weeks post-injection, mouse retinal genomic DNA was extracted for PCR amplification. We confirmed the infection of AAV by PCR amplification (Figure 5D) and quantitative PCR analysis (Figure S6) of the AAV genome in mouse retina. The editing efficiency, further quantified by NGS, indicated that split-PE1024 with the CMV promoter performed +5 G-to-T transversion editing with an average efficiency of 1.71% ± 1.35% and average indels of 0.17% ± 0.01% at Dnmt1 in the adult mouse retina, which showed a significant difference compared with control (split-PE1024 with non-targeting pegRNA). Unfortunately, the elongation factor (EF)1α core promoter injecting mouse retina showed an average editing efficiency of 0.58% ± 0.54% (Figure 5E), which may result from the fact that the copy number of the N-terminal half of the EF1α core promoter-driven split-PE was slightly lower than that of the CMV promoter-driven split-PE (Figure S6). Meanwhile, split-PE1024 displayed no detectable indels at eight predicted top off-target sites of Dnmt1, suggesting its high safety and reliability (Figure S7). These data showed that endogenous genomic sites in adult mouse retina could be edited split-PE delivered with dual-AAV.

Figure 5.

Efficient editing of Dnmt1 in adult mouse eye by split-PE1024 delivered with dual AAVs

(A) Schematic illustration of subretinal injection. 1.1 × 1010 vg AAV8 (5 × 109 vg N-terminal half of split-PE1024 + 5 × 109 vg C-terminal half of split-PE1024 + 1 × 109 vg GFP) was injected into 6-week-old mouse retina. Mouse retina genomic DNA was isolated and extracted 6 weeks post-injection. (B) Representative retinal flat-mount showing variable GFP intensity and uneven distribution. 1 week post-injection of 109 vg AAV8-GFP, the mouse retina was isolated. Scale bar, 2,000 μm. (C) Fluorescence image of mouse retina section. RPE, retinal pigment epithelium; OS, outer segment; IS, inner segment; ONL, outer nuclear layer; OPL, outer plexiform layer; INL, inner nuclear layer; IPL, inner plexiform layer; GC, ganglion cell layer. Scale bar, 200 μm. (D) PCR amplification to detect the AAV genome in mouse retina injected with non-targeting or Dnmt1-targeting dual-AAV split-PEs with the EF1α or CMV promoter. Mock, noninjected control mouse retina. (E) Targeted editing efficiencies at the Dnmt1 site in adult mouse retina. Editing efficiencies represent sequencing reads that contain the correct edit and do not contain indels among total sequencing reads, which were analyzed by MATLAB and CRISPResso2. Indels were plotted for comparison. Retina injected with split-PE1024 and non-targeting pegRNA as the negative control. Values and error bars represent the mean ± SD of more than three independent mice eyes. t test was used for calculating statistical significance (∗p < 0.05).

Discussion

In this study, we developed an optimized dual-AAV split-PE using Rma intein, which would enable in vivo genome editing by PE. First, we engineered and screened two efficient split-PEs (split-PE1005 and split-PE1024) with high editing efficiency using a GFP-based reporter cell line (Figure 1). Then, we demonstrated that split-PEs, especially split-PE1024, could mediate robust base-to-base transversion editing and insertion in mammalian cells through plasmid transfection or dual-AAV infection (Figures 2 and 3; Figures S4 and S5). We further confirmed the successful editing for +5 G-to-T transversion at Dnmt1 in adult mouse retina through dual-AAV8 split-PE1024.

However, dual-AAV split-PE1024 performed low transversion editing (1.71% ± 1.35%) at Dnmt1 in the adult mouse retina (Figure 5E), Meanwhile, Hyewon Jang et al.40 reported almost the same editing efficiency (1.87%) in the mouse retina using trans-splicing AAV (tsAAV) vectors, which delivered two trans-splicing PE2 together with pegRNA and nick-gRNA. The low editing efficiencies may due to the relatively low editing activity of the PE system. The main problems facing PEs at present are the limited scope of application and low editing efficiency in different gene locus. Thus, a recent study described the engineered PEs to expand the range of their target sites using various protospacer-adjacent motif (PAM)-flexible Cas9 variants, which could successfully generate more than 50 types of mutations with high prime-editing activity in HEK293T cells.41 The formation of pegRNA is an identified factor affecting prime-editing efficiency, and some studies focus on the design of pegRNA to improve the prime-editing activity.42,43 Recently, Caixia Gao and colleagues44 reported an optimal performance of PE in rice, resulting from designing prime binding sites with a melting temperature of 30°C and using two in trans pegRNAs editing the same targets substantially. Yao Liu et al.45 have generated enhanced PE (ePE) with markedly higher editing efficiency using multiple modifications, which prevent pegRNA circularization through the Csy4 process and optimized the scaffold of pegRNA. However, the changes of pegRNA are inapplicable to many human pathogenic genetic variants.14 Therefore, further studies are needed to optimize the PEs to improve the editing efficiency.

In addition, the structure of split-PE may also affect the joined full-length PEs (Figures 1 and 2), which is mainly related to the chosen inteins and splitting sites. Mxe intein (Mycobacterium xenopi) was used in split-Cas9 at the 656−657 site and resulted in ∼50% recovery of cleavage activity compared to full-length Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9).46 Npu intein (Nostoc punctiforme), used in split-CBE at both 573−57427 and 739−74030 sites, performed comparable editing rates compared to the full-length version. ABE has been previously split at both 573−574 and 674−675 sites with Rma intein, , and these two split-ABE showed similar or even higher editing efficiency compared to full-length ABE in some sites.12 Recently, Pengpeng Liu et al.47 reported that split-PE employing the Npu DNAE split intein has successfully utilized dual-AAVs for the delivery and enabled the correction of a pathogenic mutation in the mouse liver with low editing efficiencies (2.3% ± 0.4% at 6 weeks and 3.1% ± 0.6% at 10 weeks). Rma intein has been demonstrated to be the best intein for reconstituting ABE compared to the Mxe intein and Npu intein.12 Therefore, we engineered four different split-PE systems based on Rma intein in this study (Figure 1). However, it is possible to construct more efficient split-PEs after screening more inteins and splitting sites.

Encouragingly, the development of prime editing fills the gaps in the field of genome editing, enabling all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, insertion, and deletion. In theory, the vast majority of known human pathogenic alleles (about 89%) could be efficiently and precisely corrected by PE without inducing DSBs.14 Simultaneously, two research groups reported that DSBs induced by Cas9 are toxic and induce a p53-mediated DNA damage response.48,49 PE is theoretically safer than CRISPR-Cas. Our study presents a novel dual-AAV split-PE system for genome editing in adult mammals in vivo. Split-PEs may provide new therapeutics for previously incurable human genetic diseases.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and transfection

HEK293T, HeLa, and ARPE-19 cells were from ATCC, all of which were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; HyClone) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S; Invitrogen). Polyethylenimine (PEI) was used for transfection in HEK293T at about 75% confluency. The split-PE-related plasmids were transfected into the ARPE-19 cells by electroporation (Lonza; 4D X-Unit, EA-104). Cells were collected 3 days post-transfection for further analysis.

Mouse

CD-1 mice were fed under a stable raising condition (22°C ± 1°C) in a pathogen-free animal facility in Sun Yat-sen University. Experimental protocols associated with the handling of mice were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sun Yat-sen University, PR China.

Plasmid construction

pCMV-PE2 came from Addgene (#132775). All split-PE driven by the CMV promoter or EF1α core promoter were modified from pX601 (Addgene; #61591). pLenti-GFP-puro was modified from pLenti-gRNA-puro (Addgene; #52963) containing a premature stop codon in the GFP coding sequence (Figure S1). pegRNAs were ligated to pLenti-gRNA-puro, pxSplit-PE1005, or pxSplit-PE1024; gRNAs were ligated to pLenti-gRNA-puro, pxSplit-PE1006, or pxSplit-PE1025. pegRNA and gRNA sequences for different targets were listed in Table S1. The vectors, in which PEs were driven by the CMV promoter, were used in Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4, and the vectors with the CMV promoter or EF1α core promoter-driven PE expression were used in Figure 5. The split-PE AAV vector contains either inverted terminal repeat (ITR)-promoter-nucleic localization signal (NLS)-Cas9nN-RmaN-poly(A)-U6-pegRNA-ITR or ITR-promoter-RmaC-Cas9nC-M-MLV RT-NLS-poly(A)-U6-gRNA-ITR.

Establishment of GFPm reporter cell line

HEK293T cells were transfected with pLenti-GFP-puro and lentivirus packaging vectors pMD2.G and pSPAX2. Then, HEK293T cells were infected with lentivirus supplemented carrying GFP with 8 μg/mL polybrene. 2 days post-infection, infected cells were selected with 2 μg/mL puromycin for at least 7 days.

Flow cytometry analysis

GFPm reporter cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline once and digested by 0.25% trypsin (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Then, the digested cells were terminated by the addition of phosphate-buffered saline containing 10% FBS. Samples were then detected by CytoFLEX (Beckman) to determine the percentage of GFP-positive cells.

AAV preparation

AAV package and quantification were referred to Addgene’s protocols. HEK293T cells were transfected with transfer plasmid and AAV packaging vectors pHelper and Rep/Cap at about 75% confluency. 96 h post-transfection, the supernatant was collected and processed with PEG8000 (Sigma) for virus precipitation. Meanwhile, cells were collected and lysed by sonication and Benzonase treatment. For further purification of AAVs, an iodixanol gradient was used for ultracentrifugation. Fractions containing AAVs were collected and resuspended by phosphate-buffered saline with 0.001% Pluronic F-68. Finally, the qPCR analysis was used for determining the titers of the virus with the primers listed on Addgene (ITR FP (forward primer): 5′-GGAACCCCTAGTGATGGAGTT-3′; ITR FRP (reverse primer): 5′-CGGCCTCAGTGAGCGA-3′). Purified AAV was aliquoted and stored at −80°C.

AAV infection in human cells

5,000 HEK293T cells or HeLa cells were seeded in 24-well plates and infected with AAV1 at 107 MOI. 5 days post-infection, cells were collected for genomic DNA extraction using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN).

Subretinal injection

6-week-old CD-1 female mice were anesthetized. Phenylephrine (0.5%) and tropicamide (0.5%) were used for dilating the pupils. Then, proparacaine hydrochloride (0.5%) was used for anesthetizing the pupils. For assisted visualization of the mouse retina, a little ophthalmic viscoelastic solution was dropped on the corneal surface. Then, a small hole was punctured at the corneal margin using a 30G needle. 1 μL AAV8 (5 × 109 vg N-terminal half of split-PE1024 + 5 × 109 vg C-terminal half of split-PE1024 + 1 × 109 vg GFP) was injected using a 33G blunt-end needle (Hamilton; 7803-05) in 40 s, which was connected with a Hamilton syringe (1701RN no needle, 7653-01) and inserted through the hole and positioned to subretinal space. For preventing dryness and post-surgery infection, vet ointment was used post-injection.

Targeted deep sequencing

Genomic DNA was purified from cultured cells or mouse RPE using a DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (QIAGEN). The target/off-target sites were amplified with barcode-containing primers and a KOD PCR kit (Toyobo) to generate a deep-sequencing library. PCR products were then sequenced paired end 150 HiSeq 2000 (Illumina). Single-nucleotide transversion-editing efficiency was analyzed by MATLAB,8 whereas insertion editing efficiency and indel frequency were analyzed by CRISPResso2.33

Mouse retinal processing

1 week post-injection, for mouse retinal flatmount, the mouse retina was isolated and cut to a “clover” shape to release any tensions in the phosphate-buffered saline. The cut retina was then stained in 0.1% Hoechst and mounted in 7.5% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), 50 mM Tris (pH 8.0), mounting media. For the mouse retinal section, after removing the cornea and lens, the eyecup was washed with phosphate-buffered saline twice and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 30 min. Fixed eyecup was incubated in phosphate-buffered saline with 30% sucrose at 4°C for 12 h. Incubated eye cup was then immersed in Tissue-Tek O.C.T.(optimal cutting temperature) compound for cryo-section and stained in 0.1% Hoechst. Mouse retinal flatmount and section were imaged by the Lionheart imaging system.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significances were examined using one-way ANOVA with the Dunnett’s test for data with equal variance among multiple values and normal distribution (GraphPad 8.0.2). t test was also used for calculating statistical significance comparing two groups of normally distributed data. Data were deemed significant at ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗0.01, or ∗∗∗0.001.

High-throughput sequencing (HTS) data availability

HTS data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database (SRA; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra) under accession numbers NCBI: PRJNA739843 and NCBI: PRJNA739877 and listed in Table S2.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC1001901), National Natural Science Foundation of China (31971365 and 32001063), Guangdong Special Support Program (2019BT02Y276), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2020B1515120090), and Guangzhou Science and Technology Project (201803010020 and 201803010032).

Author contributions

J.H. conceived and designed the project and contributed to the final approval of the manuscript. S.Z., Y.C., G.W., J. Wen, J. Wu, Q.L., Y.L., R.K., S.H., and J. Wang performed the experiments and analyzed the data. S.Z., Y.C., P.L., and J.H. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.07.011.

Contributor Information

Puping Liang, Email: liangpp5@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Junjiu Huang, Email: hjunjiu@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Cong L., Ran F.A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., Habib N., Hsu P.D., Wu X., Jiang W., Marraffini L.A., Zhang F. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823. doi: 10.1126/science.1231143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jinek M., Chylinski K., Fonfara I., Hauer M., Doudna J.A., Charpentier E. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science. 2012;337:816–821. doi: 10.1126/science.1225829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mali P., Yang L., Esvelt K.M., Aach J., Guell M., DiCarlo J.E., Norville J.E., Church G.M. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Komor A.C., Badran A.H., Liu D.R. CRISPR-Based Technologies for the Manipulation of Eukaryotic Genomes. Cell. 2017;168:20–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hsu P.D., Lander E.S., Zhang F. Development and applications of CRISPR-Cas9 for genome engineering. Cell. 2014;157:1262–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bibikova M., Carroll D., Segal D.J., Trautman J.K., Smith J., Kim Y.G., Chandrasegaran S. Stimulation of homologous recombination through targeted cleavage by chimeric nucleases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:289–297. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.1.289-297.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liang P., Xu Y., Zhang X., Ding C., Huang R., Zhang Z., Lv J., Xie X., Chen Y., Li Y., et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing in human tripronuclear zygotes. Protein Cell. 2015;6:363–372. doi: 10.1007/s13238-015-0153-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaudelli N.M., Komor A.C., Rees H.A., Packer M.S., Badran A.H., Bryson D.I., Liu D.R. Programmable base editing of A•T to G•C in genomic DNA without DNA cleavage. Nature. 2017;551:464–471. doi: 10.1038/nature24644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Komor A.C., Kim Y.B., Packer M.S., Zuris J.A., Liu D.R. Programmable editing of a target base in genomic DNA without double-stranded DNA cleavage. Nature. 2016;533:420–424. doi: 10.1038/nature17946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang P., Ding C., Sun H., Xie X., Xu Y., Zhang X., Sun Y., Xiong Y., Ma W., Liu Y., et al. Correction of β-thalassemia mutant by base editor in human embryos. Protein Cell. 2017;8:811–822. doi: 10.1007/s13238-017-0475-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeng J., Wu Y., Ren C., Bonanno J., Shen A.H., Shea D., Gehrke J.M., Clement K., Luk K., Yao Q., et al. Therapeutic base editing of human hematopoietic stem cells. Nat. Med. 2020;26:535–541. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0790-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen Y.X., Zhi S.Y., Liu W.L., Wen J.K., Hu S.H., Cao T.Q., Sun H., Li Y., Huang L., Liu Y., et al. Development of Highly Efficient Dual-AAV Split Adenosine Base Editor for In Vivo Gene Therapy. Small Methods. 2020;4:2000309. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun H., Zhi S., Wu G., Wu G., Cao T., Hao H., Songyang Z., Liang P., Huang J. Cost-effective generation of A-to-G mutant mice by zygote electroporation of adenine base editor ribonucleoproteins. J. Genet. Genomics. 2020;47:337–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jgg.2020.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anzalone A.V., Randolph P.B., Davis J.R., Sousa A.A., Koblan L.W., Levy J.M., Chen P.J., Wilson C., Newby G.A., Raguram A., Liu D.R. Search-and-replace genome editing without double-strand breaks or donor DNA. Nature. 2019;576:149–157. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1711-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y., Li X., He S., Huang S., Li C., Chen Y., Liu Z., Huang X., Wang X. Efficient generation of mouse models with the prime editing system. Cell Discov. 2020;6:27. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0165-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gao P., Lyu Q., Ghanam A.R., Lazzarotto C.R., Newby G.A., Zhang W., Choi M., Slivano O.J., Holden K., Walker J.A., 2nd, et al. Prime editing in mice reveals the essentiality of a single base in driving tissue-specific gene expression. Genome Biol. 2021;22:83. doi: 10.1186/s13059-021-02304-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schene I.F., Joore I.P., Oka R., Mokry M., van Vugt A.H.M., van Boxtel R., van der Doef H.P.J., van der Laan L.J.W., Verstegen M.M.A., van Hasselt P.M., et al. Prime editing for functional repair in patient-derived disease models. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:5352. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19136-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bosch J.A., Birchak G., Perrimon N. Precise genome engineering in Drosophila using prime editing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2021996118. e2021996118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin Q., Zong Y., Xue C., Wang S., Jin S., Zhu Z., Wang Y., Anzalone A.V., Raguram A., Doman J.L., et al. Prime genome editing in rice and wheat. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:582–585. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0455-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y., Zhi S., Liang P., Zheng Q., Liu M., Zhao Q., Ren J., Cui J., Huang J., Liu Y., Songyang Z. Single AAV-Mediated CRISPR-SaCas9 Inhibits HSV-1 Replication by Editing ICP4 in Trigeminal Ganglion Neurons. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020;18:33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.omtm.2020.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li C., Samulski R.J. Engineering adeno-associated virus vectors for gene therapy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2020;21:255–272. doi: 10.1038/s41576-019-0205-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang D., Tai P.W.L., Gao G. Adeno-associated virus vector as a platform for gene therapy delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:358–378. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0012-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.MacLaren R.E., Groppe M., Barnard A.R., Cottriall C.L., Tolmachova T., Seymour L., Clark K.R., During M.J., Cremers F.P., Black G.C., et al. Retinal gene therapy in patients with choroideremia: initial findings from a phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1129–1137. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62117-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Haasteren J., Li J., Scheideler O.J., Murthy N., Schaffer D.V. The delivery challenge: fulfilling the promise of therapeutic genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:845–855. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0565-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anzalone A.V., Koblan L.W., Liu D.R. Genome editing with CRISPR-Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors. Nat. Biotechnol. 2020;38:824–844. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0561-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ryu S.M., Koo T., Kim K., Lim K., Baek G., Kim S.T., Kim H.S., Kim D.E., Lee H., Chung E., Kim J.S. Adenine base editing in mouse embryos and an adult mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:536–539. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy J.M., Yeh W.H., Pendse N., Davis J.R., Hennessey E., Butcher R., Koblan L.W., Comander J., Liu Q., Liu D.R. Cytosine and adenine base editing of the brain, liver, retina, heart and skeletal muscle of mice via adeno-associated viruses. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2020;4:97–110. doi: 10.1038/s41551-019-0501-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chew W.L., Tabebordbar M., Cheng J.K.W., Mali P., Wu E.Y., Ng A.H.M., Zhu K., Wagers A.J., Church G.M. A multifunctional AAV-CRISPR-Cas9 and its host response. Nat. Methods. 2016;13:868–874. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zetsche B., Volz S.E., Zhang F. A split-Cas9 architecture for inducible genome editing and transcription modulation. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:139–142. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Villiger L., Grisch-Chan H.M., Lindsay H., Ringnalda F., Pogliano C.B., Allegri G., Fingerhut R., Häberle J., Matos J., Robinson M.D., et al. Treatment of a metabolic liver disease by in vivo genome base editing in adult mice. Nat. Med. 2018;24:1519–1525. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0209-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li Y. Split-inteins and their bioapplications. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015;37:2121–2137. doi: 10.1007/s10529-015-1905-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aranko A.S., Wlodawer A., Iwaï H. Nature’s recipe for splitting inteins. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2014;27:263–271. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzu028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clement K., Rees H., Canver M.C., Gehrke J.M., Farouni R., Hsu J.Y., Cole M.A., Liu D.R., Joung J.K., Bauer D.E., Pinello L. CRISPResso2 provides accurate and rapid genome editing sequence analysis. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:224–226. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0032-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim D., Kim S., Kim S., Park J., Kim J.S. Genome-wide target specificities of CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases revealed by multiplex Digenome-seq. Genome Res. 2016;26:406–415. doi: 10.1101/gr.199588.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsai S.Q., Zheng Z., Nguyen N.T., Liebers M., Topkar V.V., Thapar V., Wyvekens N., Khayter C., Iafrate A.J., Le L.P., et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015;33:187–197. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Labun K., Montague T.G., Krause M., Torres Cleuren Y.N., Tjeldnes H., Valen E. CHOPCHOP v3: expanding the CRISPR web toolbox beyond genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W171–W174. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pliatsika V., Rigoutsos I. “Off-Spotter”: very fast and exhaustive enumeration of genomic lookalikes for designing CRISPR/Cas guide RNAs. Biol. Direct. 2015;10:4. doi: 10.1186/s13062-015-0035-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu W., Wu Z. In Vivo Applications of CRISPR-Based Genome Editing in the Retina. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018;6:53. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2018.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin F.-L., Wang P.-Y., Chuang Y.-F., Wang J.-H., Wong V.H.Y., Bui B.V., Liu G.-S. Gene Therapy Intervention in Neovascular Eye Disease: A Recent Update. Mol. Ther. 2020;28:2120–2138. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2020.06.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jang H., Shin J.H., Jo D.H., Seo J.H., Yu G., Gopalappa R., Cho S.-R., Kim J.H., Kim H.H. Prime editing enables precise genome editing in mouse liver and retina. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.01.08.425835. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kweon J., Yoon J.-K., Jang A.-H., Shin H.R., See J.-E., Jang G., Kim J.-I., Kim Y. Engineered prime editors with PAM flexibility. Mol. Ther. 2021;29:2001–2007. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim H.K., Yu G., Park J., Min S., Lee S., Yoon S., Kim H.H. Predicting the efficiency of prime editing guide RNAs in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021;39:198–206. doi: 10.1038/s41587-020-0677-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Standage-Beier K., Tekel S.J., Brafman D.A., Wang X. Prime Editing Guide RNA Design Automation Using PINE-CONE. ACS Synth. Biol. 2021;10:422–427. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin Q., Jin S., Zong Y., Yu H., Zhu Z., Liu G., Kou L., Wang Y., Qiu J.L., Li J., Gao C. High-efficiency prime editing with optimized, paired pegRNAs in plants. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41587-021-00868-w. Published online March 25, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu Y., Yang G., Huang S., Li X., Wang X., Li G., Chi T., Chen Y., Huang X., Wang X. Enhancing prime editing by Csy4-mediated processing of pegRNA. Cell Res. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41422-021-00520-x. Published online June 8, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fine E.J., Appleton C.M., White D.E., Brown M.T., Deshmukh H., Kemp M.L., Bao G. Trans-spliced Cas9 allows cleavage of HBB and CCR5 genes in human cells using compact expression cassettes. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:10777. doi: 10.1038/srep10777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu P., Liang S.Q., Zheng C., Mintzer E., Zhao Y.G., Ponnienselvan K., Mir A., Sontheimer E.J., Gao G., Flotte T.R., et al. Improved prime editors enable pathogenic allele correction and cancer modelling in adult mice. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:2121. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22295-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haapaniemi E., Botla S., Persson J., Schmierer B., Taipale J. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing induces a p53-mediated DNA damage response. Nat. Med. 2018;24:927–930. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0049-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ihry R.J., Worringer K.A., Salick M.R., Frias E., Ho D., Theriault K., Kommineni S., Chen J., Sondey M., Ye C., et al. p53 inhibits CRISPR-Cas9 engineering in human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Med. 2018;24:939–946. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0050-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.