Abstract

Objectives

This study will contribute to the systematic epidemiological description of morbidities among migrants, refugees and asylum seekers when crossing the Mediterranean Sea.

Setting

Since 2015, Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) has conducted search and rescue activities on the Mediterranean Sea to save lives, provide medical services, to witness and to speak out.

Participants

Between November 2016 and December 2019, MSF rescued 22 966 migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

We conducted retrospective data analysis of data collected between January 2016 and December 2019 as part of routine monitoring of the MSF’s healthcare services for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers on two search and rescue vessels.

Results

MSF conducted 12 438 outpatient consultations and 853 sexual and reproductive health consultations (24.9% of female population, 853/3420) and documented 287 consultations for sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). The most frequently diagnosed health conditions among children aged 5 years or older and adults were skin conditions (30.6%, 5475/17 869), motion sickness (28.6%, 5116/17 869), headache (15.4%, 2 748/17 869) and acute injuries (5.7%, 1013/17 869). Of acute injuries, 44.7% were non-violence-related injuries (453/1013), 30.1% were fuel burns (297/1013) and 25.4% were violence-related injuries (257/1013).

Conclusion

The limited testing and diagnostics capacity of the outpatient department, space limitations, stigma and the generally short length of stay of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers on the ships have likely led to an underestimation of morbidities, including mental health conditions and SGBV. The main diagnoses on board were directly related to journey on land and sea and stay in Libya. We conclude that this population may be relatively young and healthy but displays significant journey-related illnesses and includes migrants, refugees and asylum seekers who have suffered significant violence during their transit and need urgent access to essential services and protection in a place of safety on land.

Keywords: public health, epidemiology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We will present data from onboard outpatient consultations (n=12 438) that were systematically offered to all rescued people on one of the largest and longest running rescue vessels on the Mediterranean Sea.

This study will contribute to the systematic epidemiological description of morbidities among migrants, refugees and asylum seekers when crossing the Mediterranean Sea.

Due to the limited testing and diagnoses capacity of the outpatient department, space limitations and the generally short length of stay of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers on the ship, it was not feasible to provide in-depth medical and psychological treatment and support, which has likely led to an underestimation of actual morbidities, including mental health conditions and sexual and gender-based violence.

All data presented were collected as routine Médecins sans Frontières programme data, which needed to be recorded quickly so as not to create further delays for migrants awaiting medical care; therefore, some of the data were incomplete and could only be partly used for this analysis.

Background

Since 2014, a large number of migrants, refugees and asylum have attempted to cross the Mediterranean Sea to reach Europe. Between 2014 and 2019, 1 995 651 migrants, refugees and asylum seekers arrived in Italy, Spain, Malta, Greece and Cyprus by boat.1 The total number of deaths and missing people on the central Mediterranean Sea route is unknown. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) has reported 15 946 deaths and missing people between 2014 and 2020, which is likely an underestimation.2 The underestimation is due to the occurrence of invisible migrant shipwrecks that remain unreported and the number of victims unknown.3 The most frequently recorded countries of origin varied over time as well as by destination,4–6 and include Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea, Chad, Gambia, Ivory Coast, Libya, Mali, Nigeria, Senegal, Sudan and South Sudan.6

Many migrants, refugees and asylum seekers are fleeing protracted humanitarian emergencies in their countries of origin, embarking on long inter-regional travel prior to arriving in North Africa.5 Some migrants, refugees and asylum seekers set out to reach Europe, while others initially plan to find employment and a place to live in Libya and later might decide to travel onwards to Europe. The central Mediterranean Sea route, often via Libya to Italy, has been consistently used.1 In addition to Libya’s strategic location, conflicts and instability in the country have hindered border control and created an environment where smuggling networks can flourish.5 Prior to attempting the crossing of the central Mediterranean Sea, migrants, refugees and asylum seekers often spend long periods in unofficial and official places of captivity in Libya.5 Several reports have documented unhygienic and extremely unhealthy conditions in these detention centres, characterised by overcrowding, lack of ventilation, insufficient quantities and quality of food and lacking water and sanitation facilities.7 8 Recently, MSF published data on health conditions of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers detained in eight official detention centres where MSF has provided medical services. This report documented the dire living circumstances and adverse health effects of arbitrary detention on migrants, refugees and asylum seekers at official detention centres in Libya.9 Even prior to arriving in Libya, many migrants, refugees and asylum seekers have experienced violence including extortion, ill-treatment, trafficking, forced labour and sexual exploitation in their country of origin or along the way.5

Since 2015, Médecins sans Frontières (MSF) has conducted search and rescue activities on the central Mediterranean Sea to save lives, to provide medical services, to witness and to speak out. Between 2015 and 2018, MSF has operated the ship ‘Aquarius’ in partnership with non-governmental organisation SOS Mediterranee. Between December 2018 and July 2019, MSF had to halt their search and rescue activities on the ship ‘Aquarius’. In July 2019, search and rescue operations were resumed with SOS Mediterranee on the ship ‘Ocean Viking’.10

On these vessels, MSF has been providing outpatient medical consultations, screening and triage, referrals, sexual and reproductive health services, including support for survivors of sexual and gender-based violence. MSF does not provide systematic mental health screening for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers, but psychological first aid. Treatment and diagnoses were performed by physicians and nurses based on clinical assessment and routine tests (body temperature, blood pressure, pulse oximetric, haemoglobin test, blood sugar, urine dipstick, malaria rapid test, pregnancy test). Treatment options were limited to basic wound care, oxygen and a limited number of pharmaceuticals. Any patient requiring more complex treatment needed medical evacuation. As on other search and rescue vessels, the MSF medical teams are working under constant pressure of the urgent assessment and treatment and support of hundreds of rescued persons in distress when a rescue is completed, complex logistical arrangements and depending on the season, harsh meteorological circumstances.11–13

There have been publications on the health conditions of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in migrant reception centres in Italy, Spain and Greece.14–17 These studies show that the majority of the diagnoses at migration reception centres were dermatological, such as scabies, skins infections and dermatitis of various origins. Respiratory infections and varicella were the most frequent infectious diseases, commonly related to the conditions experienced during the journey.

Limited quantitative data are available on the health of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers while they are on search and rescue vessels.11 13 Unlike previous studies, we will present data from onboard consultations that were systematically offered to all rescued people on one of the largest and longest running rescue vessels on the Mediterranean Sea. This study will contribute to the systematic epidemiological description of morbidities among migrants, refugees and asylum seekers when crossing the Mediterranean Sea.

Methods

We conducted retrospective data analysis of data collected between January 2016 and December 2019 as part of the routine monitoring of the MSF’s outpatient healthcare services for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers on two search and rescue vessels on the central Mediterranean Sea. We analysed data that were collected on the vessel ‘Aquarius’ between January 2016 and December 2018 and on the vessel ‘Ocean Viking’ between January and December 2019.

Study population

The study population consists of all migrants, refugees and asylum seekers who were rescued by MSF search and rescue vessels (‘Aquarius’ and ‘Ocean Viking’) on the central Mediterranean Sea between January 2016 and December 2019.

Data sources and data collection

Routine programme data

The total number of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers are established and recorded by the medical team at the start of each rescue in a register. Some basic demographic information is also captured, including sex, numbers of children under 5 years old, unaccompanied minors and pregnant women and the country of origin of the migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

Routine medical data

Clinical data collection took place as a routine medical activity. The data sets contain data from all migrants, refugees and asylum seekers who presented at the MSF outpatient department (OPD) on the search and rescue vessels with a medical complaint. The medical data collection includes the number of new and follow-up OPD consultations and sexual and reproductive health consultations, including consultations for sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). Medical evacuation and ambulatory referrals on disembarkation were made based on case severity as assessed by the medical team and were captured in the routine medical data. The medical databases also contain data on the diagnoses of patients seen at the OPD, aggregated per week.

Data analysis

Following data cleaning and transfer to STATA V.16 (Stata Corporation), we conducted descriptive analysis of the available programme and medical data. Indicators were calculated as proportions (eg, morbidities).

Patient and public involvement

For this study, we retrospectively analysed aggregated routine data from the OPD on two search and rescue vessels. Patients were not involved in the study design or implementation. Due to the short length of stay of patients on the search and rescue vessels, we are unable to disseminate the study findings to the patients.

Results

Demographic characteristics

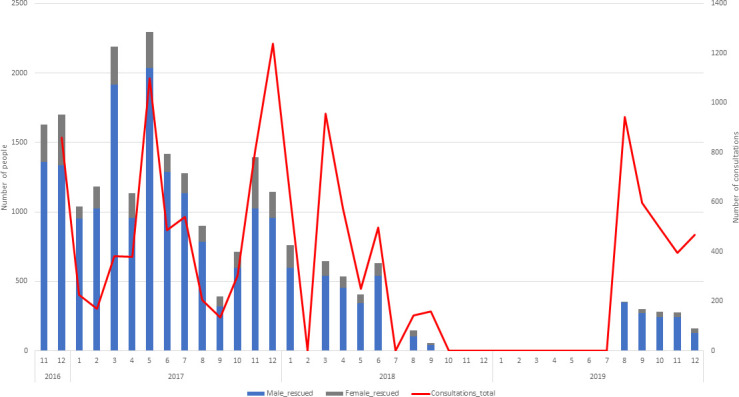

Over the course of 3 years (November 2016–December 2019), 22 966 migrants, refugees and asylum seekers were rescued by MSF’s search and rescue vessels on the central Mediterranean Sea. UNHCR reported that during this same period, 176 278 crossed the central Mediterranean Sea to Italy.18 Among rescued migrants, refugees and asylum seekers were 3420 women (14.9%, 3420/22 966). A total of 12 438 medical consultations were conducted between January 2016 and December 2019. Due to the number of rescued people and the characteristics of the intervention, the number of outpatient consultations fluctuated per month (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Number of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers rescued by MSF’s search and rescue vessels on the Mediterranean Sea and number of consultations at MSF’s Outpatient Department by month. No rescues took place in February and July 2018 and between October 2019 and July 2019. Data on number of outpatient department consultations missing for June, 2017. Blue: number of rescued males. Grey: number of rescued females. Red: number of outpatient department consultations. MSF, Médecins sans Frontières.

Between November 2017 and December 2019, 4261 unaccompanied minors were rescued (18.6%, 4261/22 966). Of the total number of rescued people, 328 were children under 5 (1.4%, 328/22 966). Of the female population, 2205 women were travelling alone (59.2%, 2205/3 420) and 346 of the rescued women were pregnant (10.1%, 346/3420). The countries of origin of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers were Nigeria (18.0%, 4140/22 966), followed by Eritrea (10.4%, 2395/22 966), Guinea Conakry (8.3%, 1916/22 966), Ivory Coast (7.2%, 1656/22 966) and Bangladesh (6.2%, 1432/22 966) (table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics and country of origin of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers rescue by MSF’s search and rescue vessels on the Mediterranean Sea, November 2016–December 2019

| n | %* | |

| Number of rescued people | 22 966 | |

| Male | 19 546 | 85.1 |

| Female | 3420 | 14.9 |

| Women travelling alone | 2025 | 59.2† |

| Pregnant women | 346 | 10.1† |

| Unaccompanied minors | 4261 | 18.6 |

| Children<5 years | 328 | 1.4 |

| Country of origin | ||

| Sub-Saharan Africa | ||

| Nigeria | 4140 | 18.0 |

| Eritrea | 2395 | 10.4 |

| Guinea Conakry | 1916 | 8.3 |

| Ivory Coast | 1656 | 7.2 |

| Sudan | 1195 | 5.2 |

| Senegal | 1166 | 5.1 |

| Gambia | 1128 | 4.9 |

| Ghana | 857 | 3.7 |

| Cameroon | 593 | 2.6 |

| Somalia | 436 | 1.9 |

| Sierra Leone | 351 | 1.5 |

| Ethiopia | 167 | 0.7 |

| Guinea Bissau | 155 | 0.7 |

| Mali | 129 | 0.6 |

| Burkina Faso | 118 | 0.5 |

| Togo | 102 | 0.4 |

| Niger | 99 | 0.4 |

| South Sudan | 59 | 0.3 |

| Chad | 49 | 0.2 |

| Benin | 31 | 0.1 |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 9 | 0.0 |

| Uganda | 9 | 0.0 |

| Central African Republic | 4 | 0.0 |

| Liberia | 2 | 0.0 |

| Asia | ||

| Bangladesh | 1432 | 6.2 |

| Syria | 334 | 1.5 |

| Pakistan | 273 | 1.2 |

| Palestina | 41 | 0.2 |

| Yemen | 22 | 0.1 |

| Iraq | 5 | 0.0 |

| Afghanistan | 3 | 0.0 |

| North Africa | ||

| Egypt | 199 | 0.9 |

| Algeria | 126 | 0.5 |

| Tunesia | 57 | 0.2 |

| Morocco | 21 | 0.1 |

| Libya | 18 | 0.1 |

| Other/unknown | ||

| Other | 96 | 0.4 |

| Unknown | 3573 | 15.6 |

*Pertentage of total number of rescued people.

†Percentage of total number of rescued women.

MSF, Médecins sans Frontières.

Health conditions

Between January 2016 and December 2019, MSF conducted 12 438 outpatient consultations, of which 9811 were new consultations (78.9%, 9811/12 438). Additionally, MSF performed 143 antenatal care consultations (41.3% of self-reported female pregnant population, 143/346) and conducted 853 sexual and reproductive health consultations (24.9% of female population, 853/3420).

In addition, MSF documented 287 consultations for SGBV, of which the vast majority (99.7%, 286/287) took place 72 hours or more after the incident occurred. Five women were recorded who were pregnant after a rape. There were eight women recorded who requested termination of pregnancy, of which six were referred on disembarkation in Europe.

MSF organised 23 urgent medical referrals, which required immediate transport to referral health facilities by fast boat or by helicopter. An additional 1552 non-urgent medical referrals were organised who were referred to non-MSF clinics on arrival on the mainland (table 2).

Table 2.

MSF consultations and referrals of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers on MSF’s search and rescue vessels on the Mediterranean Sea, 2016–2019

| N | % | |

| All consultations | 12 438 | |

| Number of new consultations | 9811 | 78.88 |

| Other follow-up | 211 | 1.70 |

| Number of dressings new | 772 | 6.21 |

| Number of dressings follow-up | 334 | 2.69 |

| Number of injections | 1310 | 10.53 |

| SRH consultations* | 853 | 6.86 |

| ANC consultations† | 143 | 25.04 |

| SGBV consultations* | 287 | 2.31 |

| SGBV consultations<72 hours‡ | 1 | 0.35 |

| SGBV consultations>72 hours‡ | 286 | 99.65 |

| Pregnant due to rape§ | 5 | 6.58 |

| TOP requests† | 8 | 1.40 |

| TOP referrals† | 6 | 1.05 |

| Referrals | 1575 | 12.66 |

| Urgent—Medevac (fast boat/helicopter) | 23 | 1.46 |

| Not urgent (on arrival) | 1552 | 98.54 |

*Number of SRH and SGBV consultations recorded between May 2016 and December 2019. Percentages calculated over the total number of consultations in the same period.

†Number of ANC consultations, TOP requests and TOP referrals recorded between September 2017 and December 2019. Percentage calculated over the total number of SRH consultations in the same period.

‡Number of SGBV consultations that took place within and after 72 hours recorded between December 2016 and December 2019. Percentages calculated over the total number of SGBV consultations in the same period.

§Number of women pregnant due to rape recorded between January 2018 and December 2019. Percentage calculated over total number of pregnant women during the same period.

ANC, ante-natal care; MSF, Médecins sans Frontières; SGBV, sexual and gender-based violence; SRH, sexual and reproductive health; TOP, termination of pregnancy.

Among all diagnoses for children under 5, 46.8% (51/109) were related to skin conditions. The most frequently diagnosed health conditions among children aged 5 years or older and adults were skin conditions (30.6%, 5475/17 869), motion sickness (28.6%, 5116/17 869), headache (15.4%, 2748/17 869) and acute injuries (5.7%, 1013/17 869). Of acute injuries, 44.7% were non-violence-related injuries (ie, injuries that were not caused by violence) (453/1013), 30.1% were fuel burns (297/1013) and 25.4% were violence-related injuries (257/1013) (table 3).

Table 3.

Health conditions of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers on MSF’s search and rescue vessels on the Mediterranean Sea, 2016–2019: MSF outpatient department consultations

| Diagnosis | <5 years | ≥5 years | Total | Proportional morbidity (%) | ||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | |||

| Acute injuries | 4 | 0 | 834 | 179 | 1017 | 5.66 |

| Fuel burn | 0 | 0 | 212 | 85 | 297 | 1.65 |

| Non-violence related injury | 3 | 0 | 399 | 54 | 456 | 2.54 |

| Resuscitation | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 0.04 |

| Violence-related injury | 0 | 0 | 220 | 37 | 257 | 1.43 |

| Chronic diseases | 0 | 0 | 58 | 13 | 71 | 0.39 |

| Dehydration | 2 | 1 | 503 | 35 | 541 | 3.01 |

| Hypothermia | 0 | 2 | 153 | 22 | 177 | 0.98 |

| Infectious diseases | 8 | 8 | 740 | 101 | 857 | 4.77 |

| Acute bloody diarrhoea | 0 | 0 | 30 | 6 | 36 | 0.20 |

| Acute flaccid paralysis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Acute lower respiratory tract infection | 1 | 1 | 58 | 10 | 70 | 0.39 |

| Acute upper respiratory tract infection | 6 | 6 | 373 | 41 | 426 | 2.37 |

| Acute watery diarrhoea | 1 | 1 | 194 | 26 | 222 | 1.23 |

| Malaria (confirmed) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0.02 |

| Measles (suspected) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Meningitis (suspected) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Sexually transmitted infection | 0 | 0 | 51 | 13 | 64 | 0.36 |

| Tuberculosis (suspected) | 0 | 0 | 32 | 4 | 36 | 0.20 |

| Typhoid fever | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00 |

| Gynaecological conditions | 0 | 0 | 0 | 575 | 575 | 3.20 |

| Gynaecological disease | 0 | 0 | 0 | 93 | 93 | 0.52 |

| Pregnancy related | 0 | 0 | 0 | 482 | 482 | 2.68 |

| Skin conditions | 24 | 27 | 4839 | 636 | 5526 | 30.74 |

| Scabies | 7 | 9 | 1401 | 210 | 1627 | 9.05 |

| Skin disease | 14 | 18 | 3259 | 421 | 3712 | 20.65 |

| Skin infection | 3 | 0 | 179 | 5 | 187 | 1.04 |

| Mental health | 0 | 0 | 14 | 12 | 26 | 0.14 |

| Common psychiatric disorders | 0 | 0 | 9 | 11 | 20 | 0.11 |

| Severe psychiatric disorders | 0 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 0.03 |

| Motion sickness | 2 | 3 | 4344 | 772 | 5121 | 28.48 |

| Other conditions | 15 | 13 | 2987 | 561 | 3576 | 19.89 |

| Anaemia | 0 | 0 | 8 | 3 | 11 | 0.06 |

| Fever without identified cause | 4 | 3 | 80 | 19 | 106 | 0.59 |

| Headache | 0 | 0 | 2363 | 385 | 2748 | 15.29 |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 | 0 | 28 | 21 | 49 | 0.27 |

| Eye infection | 1 | 1 | 73 | 15 | 90 | 0.50 |

| Other | 10 | 9 | 435 | 118 | 572 | 3.18 |

| Severe acute malnutrition | 0 | 0 | 7 | 2 | 9 | 0.05 |

| Sexual violence | 0 | 0 | 30 | 452 | 482 | 2.68 |

| Total | 55 | 54 | 14 509 | 3360 | 17 978 | 100 |

*Number of times disease or condition was diagnosed at the outpatient department between January 2016 and December 2019. The total number of diagnoses exceeds the total number of consultations due to staff turnover that lead to variation in procedures, documentation and measurements. For example, for some months, the deck management of motion sickness, headache and deck inspection of scabies were included in the OPD consultations, while other months they were excluded from the total OPD consultation counts.

MSF, Médecins sans Frontières; OPD, outpatient department.

Sexual and gender-based violence

MSF documented a total of 482 consultations for SGBV, of which 30 were for male and 452 were for female survivors (table 3). Of the 482 consultations for SGBV, 95 were first consultations for rape specifically in 2018 (78) and 2019.17 Of these first consultations, 99% (94/95) took place more than 72 hours after the incident. The majority of survivors were female (91.6%, 87/95) and 15 years or older (99%, 94/95). Most survivors of rape came from Nigeria (36.8%, 35/95), followed by Cameroon (21.1%, 20/95) and Ivory Coast (19%, 18/95) (table 4).

Table 4.

Consultations for rape of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers on MSF’s search and rescue vessels on the Mediterranean Sea, 2018–2019

| 2018 | 2019 | Total | ||||

| N | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Number of first consultations for rape | 78 | 17 | 95 | |||

| Time since incident | ||||||

| <72 hours | 1 | 1.28 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.05 |

| >72 hours | 77 | 98.72 | 17 | 1.00 | 94 | 98.95 |

| Age | ||||||

| <5 years | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5–14 years | 1 | 1.28 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.05 |

| ≥15 | 77 | 98.72 | 17 | 1.00 | 94 | 98.95 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 71 | 91.03 | 16 | 0.94 | 87 | 91.58 |

| Male | 7 | 8.97 | 1 | 0.06 | 8 | 8.42 |

| Country of origin | ||||||

| Cameroon | 15 | 19.23 | 5 | 29.41 | 20 | 21.05 |

| Eritrea | 2 | 2.56 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.11 |

| Ghana | 1 | 1.28 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.05 |

| Guinea Conakry | 1 | 1.28 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.05 |

| Ivory Coast | 13 | 16.67 | 5 | 29.41 | 18 | 18.95 |

| Liberia | 1 | 1.28 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.05 |

| Mali | 1 | 1.28 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.05 |

| Morocco | 3 | 3.85 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3.16 |

| Nigeria | 31 | 39.74 | 4 | 23.53 | 35 | 36.84 |

| Senegal | 1 | 1.28 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.05 |

| Sierra Leone | 5 | 6.41 | 1 | 5.88 | 6 | 6.32 |

| Somalia | 3 | 3.85 | 2 | 11.76 | 5 | 5.26 |

| Sudan | 1 | 1.28 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.05 |

MSF, Médecins sans Frontières.

Mortality on board

Between January 2016 and December 2019, five deaths occurred on MSF’s search and rescue vessels. Probable causes of death included compressive asphyxiation due to human crushes and stampedes on the wooden boats or dinghies or while getting on the boat, and severe hypothermia. In addition to these five deaths, the search and rescue vessels frequently onboarded people who had already died on their journey prior to reaching the MSF vessels.

Discussion

We were able to present data from onboard consultations that were systematically offered to all 22 966 rescued people on one of the largest and longest running rescue vessels on the Mediterranean Sea over the course of 3 years (November 2016—December 2019).

The number of rescues varied per month due to the constantly changing ‘search and rescue landscape’, including restrictions on search and rescue activities of Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) and the increased involvement of the Libyan Coast Guard in rescues, returning large numbers of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers to Libya.19 20 Additionally, the number of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers attempting to make the crossing also fluctuated per month depending on weather conditions.20

Between January 2016 and December 2019, MSF conducted 12 438 outpatient consultations. MSF situational reports showed that the length of stay of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers on the search and rescue vessels varied, with increasingly long standoffs on sea in 2019. At times, the ship needed to stay off-coast for weeks with rescued people onboard while waiting to be assigned a place of safety for disembarkation. This had a direct impact on the volume of OPD consultations and medical and psychological complaints, as crowded living conditions and confined spaces onboard were causing discomfort and rescued people needed multiple consultations while awaiting non-urgent referrals.

Women represented 14.9% of the rescued migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. While this percentage is lower than the percentage of women seeking asylum in the European Union, the demographic breakdown was similar on other search and rescue vessels on the central Mediterranean route.13 21 The percentage of children under 5 and unaccompanied minors was also lower than expected compared with the percentages seeking asylum in the European Union. The central Mediterranean route is considered relatively difficult and might be less often attempted by women and children. Moreover, in critical rescues, which occur frequently on this part of the sea, there is oftentimes much loss of life, which impacts women and children disproportionately.2

The high proportional morbidity of skin conditions has been noted on other search and rescue vessels as well, frequently with superinfection.13 14 Scabies is typically associated with long permanence in conditions of poor hygiene, crowd, poverty and detentions.22–24 Therefore, the high burden of skin conditions among migrants, refugees and asylum seekers included in this study, like scabies, could be linked to the living conditions on the migrants’ journey and while they are in Libya.9

Almost 6% of the diagnoses on board (n=1017) were fuel burn wounds, violent and non-violent trauma. Similar chemical burns due to benzene were found on other search and rescue vessels, due to the mixture of saltwater with fuel that is often spilled inside the boats and stays attached to the clothing and body, causing deep burns due to prolonged skin contact.13 25 Women appear to be disproportionately affected by fuel burn wounds. An explanation could be that women often sit in the middle of the boat to be protected from the waves as they often cannot swim. If there is any fuel leakage, this often accumulates in the middle of the boat where the women sit. Some non-violent injuries may have been sustained on the dinghies or during the rescue operations. The long journey to Libya and often prolonged stay in Libya, during which people are on the move and often face exploitation, contributed to the violence-related injuries that were diagnosed.

Non-communicable diseases (NCD) only made up for 0.4% of all diagnoses. Similarly, complications from NCDs were identified in 0.7% of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers on the search and rescue vessel of NGO Open Arms on the Mediterranean Sea (n=4516).13 The lack of testing equipment, the short length of stay and the prioritisation of urgent medical care on the rescue vessels could lead to an underestimation of NCDs in rescued people. The young age and initially relatively good health of migrants that take the central Mediterranean route could also play a role.

Time and space constraints on board make it not feasible or desirable to conduct systematic mental health screening on board. Only self-reported mental health reports were recorded at the outpatient clinic. Migrant reception centres and health facilities in Europe that are implementing mental health services have found a high burden of mental health conditions.15 26 27 Similar mental health conditions following trauma have been seen along other migratory routes, such as the western Balkan corridor to Northern Europe. A study showed that nearly one-in-three migrants seen at MSF mental health clinics experienced physical or psychological trauma along their journey, many of which reporting anxiety and mental trauma.28 Considering the treacherous journey that the migrants, refugees and asylum seekers will have had to endure, including the attempt to cross on oftentimes overcrowded dinghies or wooden boats with lacking hygiene conditions and food and water availability, and in combination with underlying trauma, the psychological first aid offered by MSF is essential. Especially with the increasingly longer stand offs on sea, keeping migrants, refugees and asylum seekers on board of the search and rescue vessels for weeks. However, the limitations of space, capacity and lack of interpreters, as also noted on search and rescue vessels in Greece, will continue hinder the medical team’s ability to provide more in-depth mental health support on the ships.25 29

Out of the 482 SGBV consultations, there were 95 first consultations specifically for rape. The MSF medical team attempted to have systematic consultations with all rescued women and carefully ask about SGBV and any support they may need. However, this was difficult to implement due to space and time constraints and the hesitance of SGBV survivors to speak out due to fear of stigmatisation. Only 30 consultations were conducted for male survivors of SGBV in general, of which seven consultations were conducted for male survivors of rape specifically, which is a likely underestimation of the true number of male survivors. Additional male survivors of SGBV have been identified by non-medical staff on board and is confirmed by testimonies given by rescued people, but they refused medical consultation and were, therefore, not included in the analysis.

Limitations

The need for services was high and onboard staff were often overwhelmed with sudden influxes of rescued people. This impacted the ability of the medical team to collect accurate data and properly document diagnoses and demographic characteristics. Therefore, we do not have reliable population counts, which could be used as denominators for the calculation of disease incidence or assess whether the length of stay had an effect on the number of OPD consultations or diagnosed morbidities.

Due to the limited testing and diagnoses capacity of the OPD, space limitations and the generally short length of stay of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers on the ship, it was not feasible to provide in-depth medical and psychological treatment and support, which has likely led to an underestimation of actual morbidities including mental health conditions and SGBV.

All data presented were collected as routine MSF programme data, that needed to be recorded quickly so as not to create further delays for migrants awaiting medical care. Therefore, some of the data were incomplete and could only be partly used for this analysis. While case definitions stayed the same throughout the observation period, staff turnover lead to variation in procedures, documentation and measurements. For example, for some months, the deck management of motion sickness, headache and deck inspection of scabies were included in the OPD consultations, while other months they were excluded from the total OPD consultation counts. The recording of skin diseases, skin infections and scabies also varied over time, which resulted in three diagnosis categories that are difficult to disentangle retrospectively.

Conclusion

MSF’s access to the rescue areas in the central Mediterranean Sea has varied over the past 3 years and has been unpredictable. In line with findings from other studies of morbidities on search and rescue vessels, the main diagnoses on board where MSF teams have operated were non-severe and directly related to the migration journey on the boat and previously on the way to and in Libya such as overcrowding, lack of drinking and washing water, extreme sun exposure, heat or cold. Approximately, one-third of total diagnosis were scabies, one-third motion sickness and one-sixth headache. However, of the diseases on board, we also identified potentially severe conditions related to the journey in about 10% of the population, namely, dehydration, hypothermia and acute injuries. Additionally, we identified survivors of sexual and gender-based violence and violence-related injuries, which most likely are only the top of the iceberg. The number of diagnoses of infectious diseases was very low compared with other diagnoses.13–15 We conclude that this population may be relatively young and healthy but displays significant journey-related illnesses and includes migrants, refugees and asylum seekers who have suffered significant violence during their transit and need urgent and direct access to essential services and protection in a place of safety on land.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Our deepest gratitude and respect goes to the teams that provide support to migrants, refugees and asylum seekers on search and rescue vessels and beyond every day.

Footnotes

Contributors: AF, GH and RK were responsible for data acquisition. EvB and AK conceptualised the study. EvB was responsible for the data analysis. EvB and AK drafted the first version of the manuscript. EvB, AK, AF, GH, RK, IA, TT and HH-S were responsible for data interpretation. EvB, AK, AF, GH, RK, IA, TT and HH-S reviewed and contributed to the final version of the manuscript. EVB acts as guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants; but this research fulfilled the exemption criteria set by the Médecins Sans Frontières Ethics Review Board for a posteriori analyses of routinely collected clinical data and thus did not require MSF ERB review. It was conducted with permission from Melissa McRae, Medical Director, Operational Centre Amsterdam, Médecins Sans Frontières. This is a retrospective analysis of routinely collected data. Therefore, it has been exempted from full ethical review by MSF Holland’s research committee. The data in the used datasets did not contain individual identifiers. The data sets were password protected and only accessible by the first and last author.

References

- 1.IOM . IOM: Mediterranean arrivals reach 110,699 in 2019; deaths reach 1,283. world deaths fall | international organization for migration, 2019. Available: https://www.iom.int/news/iom-mediterranean-arrivals-reach-110699-2019-deaths-reach-1283-world-deaths-fall [Accessed 11 Dec 2020].

- 2.UNHCR Italy . Europe - Dead and missing at sea, 2021. Available: http://data2.unhcr.org/en/dataviz/95?sv=0&geo=0 [Accessed 11 Dec 2020].

- 3.IOM . Missing migrants project | Mediterranean update 1 March 2016, 2021. Available: https://www.iom.int/infographics/missing-migrants-project-mediterranean-update-1-march-2016 [Accessed 5 Feb 2021].

- 4.Kassar H, Dourgnon P. The big crossing: illegal boat migrants in the Mediterranean. Eur J Public Health 2014;24 Suppl 1:11–15. 10.1093/eurpub/cku099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNHCR . Mixed migration trends in Libya: changing dynamics and protection challenges evolution of the journey and situations of refugees and migrants in southern Libya, 2017. Available: www.altaiconsulting.com [Accessed 11 Dec 2020].

- 6.UNHCR . Mediterranean Situation: Greece [Internet]. Operational Portal, 2021. Available: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5179%0Ahttps://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean?id=1940%0Ahttps://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean%0Ahttp://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/mediterranean/location/5179 [Accessed 11 Dec 2020].

- 7.Nation U . Desperate and dangerous: report on the human rights situation of migrants and refugees in Libya, 2018. Available: https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/LY/LibyaMigrationReport.pdf [Accessed 11 Dec 2020].

- 8.Human Rights Watch . No escape from hell : EU policies contribute to abuse of migrants in Libya, 2019. Available: https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/eu0119_web2.pdf [Accessed 11 Dec 2020].

- 9.Kuehne A, van Boetzelaer E, Alfani P, et al. Health of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in detention in Tripoli, Libya, 2018-2019: retrospective analysis of routine medical programme data. PLoS One 2021;16:e0252460. 10.1371/journal.pone.0252460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medecins sans Frontieres . Search and rescue in the Mediterranean | Doctors Without Borders - USA, 2020. Available: https://www.doctorswithoutborders.org/search-and-rescue-mediterranean [Accessed 11 Dec 2020].

- 11.Kulla M, Josse F, Stierholz M, et al. Initial assessment and treatment of refugees in the Mediterranean sea (a secondary data analysis concerning the initial assessment and treatment of 2656 refugees rescued from distress at sea in support of the EUNAVFOR Med relief mission of the EU). Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2016;24:75. 10.1186/s13049-016-0270-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haga JM. The sea route to Europe – a Mediterranean massacre [Internet]. Vol. 135, Tidsskrift for den Norske Laegeforening, 2015. Available: https://tidsskriftet.no/en/2015/11/sea-route-europe-mediterranean-massacre [Accessed 11 Dec 2020]. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Cañardo G, Gálvez J, Jiménez J, et al. Health status of rescued people by the NGO open arms in response to the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean sea. Confl Health 2020;14:21. 10.1186/s13031-020-00275-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Meco E, Di Napoli A, Amato LM, et al. Infectious and dermatological diseases among arriving migrants on the Italian coasts. Eur J Public Health 2018;28:910–6. 10.1093/eurpub/cky126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trovato A, Reid A, Takarinda KC, et al. Dangerous crossing: demographic and clinical features of rescued sea migrants seen in 2014 at an outpatient clinic at Augusta harbor, Italy. Confl Health 2016;10:14. 10.1186/s13031-016-0080-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakalou E, Riza E, Chalikias M, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of refugees seeking primary healthcare services in Greece in the period 2015-2016: a descriptive study. Int Health 2018;10:421–9. 10.1093/inthealth/ihy042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Serre-Delcor N, Ascaso C, Soriano-Arandes A, et al. Health status of asylum seekers, Spain. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018;98:300–7. 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.UNHCR . Refugee & Migrant Arrivals To Europe in 2019 (Mediterranean), 2019. Available: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/74670 [Accessed 23 Mar 2021].

- 19.UNHCR . Desperate Journeys - Refugees and migrants arriving in Europe and at Europe’s borders [Internet]. Unhcr, 2019. Available: https://www.unhcr.org/desperatejourneys/%0Ahttps://data2.unhcr.org/en/documents/download/67712#_ga=2.254364495.618840998.1550701619-305019919.1544779305 [Accessed 11 Dec 2020].

- 20.MSF-OCA . MSF-OCA internal monthly medical reports and situation reports 2016-2019.

- 21.Europe and Central Asia Regional Office UN Women . Report on the legal rights of women and girl asylum seekers in the European Union, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Global Detention Project (GDP) . Immigration detention in Bahrain, 2016. Available: https://www.refworld.org/docid/5864ce3d4.html [Accessed 11 Dec 2020].

- 23.UNICEF . Trapped: Inside Libya’s detention centres - UNICEF Connect, 2017. Available: https://blogs.unicef.org/blog/libyan-detention-centres/ [Accessed 11 Dec 2020].

- 24.Fuller LC. Epidemiology of scabies. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2013;26:123–6. 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32835eb851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Escobio F, Etiennoul M, Spindola S. Rescue medical activities in the Mediterranean migrant crisis. Confl Health 2017;11:3. 10.1186/s13031-017-0105-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angeletti S, Ceccarelli G, Bazzardi R, et al. Migrants rescued on the Mediterranean sea route: nutritional, psychological status and infectious disease control. J Infect Dev Ctries 2020;14:454–62. 10.3855/jidc.11918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pfortmueller CA, Stotz M, Lindner G, et al. Multimorbidity in adult asylum seekers: a first overview. PLoS One 2013;8:e82671. 10.1371/journal.pone.0082671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arsenijević J, Schillberg E, Ponthieu A, et al. A crisis of protection and safe passage: violence experienced by migrants/refugees travelling along the Western Balkan corridor to northern Europe. Confl Health 2017;11:6. 10.1186/s13031-017-0107-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shortall CK, Glazik R, Sornum A, et al. On the ferries: the unmet health care needs of transiting refugees in Greece. Int Health 2017;9:272–80. 10.1093/inthealth/ihx032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.