Abstract

Background and Purpose:

Changes in diet and lifestyle factors are frequently recommended for persons with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). It is unknown whether these recommendations alter the gut microbiome and/or whether baseline microbiome predicts improvement in symptoms and quality of life following treatment. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to explore if baseline gut microbiome composition predicted response to a Comprehensive Self-Management (CSM) intervention and if the intervention resulted in a different gut microbiome composition compared to usual care.

Methods:

Individuals aged 18–70 years with IBS symptoms ≥6 months were recruited using convenience sampling. Individuals were excluded if medication use or comorbidities would influence symptoms or microbiome. Participants completed a baseline assessment and were randomized into the eight-session CSM intervention which included dietary education and cognitive behavioral therapy versus usual care. Questionnaires included demographics, quality of life, and symptom diaries. Fecal samples were collected at baseline and 3-month post-randomization for 16S rRNA-based microbiome analysis.

Results:

Within the CSM intervention group (n = 30), Shannon diversity, richness, and beta diversity measures at baseline did not predict benefit from the CSM intervention at 3 months, as measured by change in abdominal pain and quality of life. Based on both alpha and beta diversity, the change from baseline to follow-up microbiome bacterial taxa did not differ between CSM (n = 25) and usual care (n = 25).

Conclusions and Inferences:

Baseline microbiome does not predict symptom improvement with CSM intervention. We do not find evidence that the CSM intervention influences gut microbiome diversity or composition over the course of 3 months.

Keywords: irritable bowel syndrome, gastrointestinal microbiome, quality of life, cognitive behavioral therapy, self-management

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) affects individuals worldwide and can inflict a tremendous economic, social, and emotional burden (Sperber et al., 2017). Healthcare costs are higher for individuals with IBS compared to healthy adults (Doshi et al., 2014). IBS is considered a disorder of gut-brain interaction in which abdominal pain is accompanied by an altered bowel pattern (diarrhea, constipation, or mixed; Drossman, 2016). Recent studies of pathobiological markers support the hypotheses that IBS can develop from centrally dominant factors such as early adverse events/stress (Ju et al., 2020), significant life events with moderate stress in adults (Wang et al., 2020), luminal factors (infection, alterations in the GI microbiota [dysbiosis] triggering immune activation and changes in intestinal permeability and pain sensitivity; Bennet et al., 2015; Chong et al., 2019), or all of the above. In some individuals, these occur concurrently or interactively.

Recent meta-analyses and longitudinal studies suggest the gut microbiota composition differs between IBS patients and healthy individuals (Mari et al., 2020; Mars et al., 2020; Pimentel & Lembo, 2020; Simpson et al., 2020). Individuals with IBS typically have decreased diversity of their microbiome compared to healthy individuals (Pimentel & Lembo, 2020). Also, differences have been described among specific microbes with Enterobacteriales and Proteobacteria reported as greater in persons with IBS compared to healthy individuals (Mars et al., 2020; Rodiño-Janeiro et al., 2018). Likewise, decreased abundance of the genera Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium have been reported among individuals with IBS compared to healthy individuals (Liu et al., 2017; Mari et al., 2020). A systematic review reported mixed results for the genera Bacteroides and Enterococcus (Wang et al., 2020).

Among individuals with IBS, a bidirectional gut-brain relationship has been implicated through a number of pathways including the enteric nervous system, the central nervous system, and the gut microbiome (Mukhtar et al., 2019). Rodent studies support the concept that gut bacteria can influence anxiety and stress responses (Huo et al., 2017; Vodička et al., 2018). Similarly, a limited number of human studies have demonstrated that gut bacteria can influence emotion processing and stress coping (Allen et al., 2016; Heym et al., 2019; Moser et al., 2018; Tillisch et al., 2017).

Therapeutic approaches for IBS range from cognitive and behavioral strategies (e.g., relaxation, meditation) to dietary changes to medications that modulate bowel motility, secretion and/or pain perception. Cognitive and behavioral strategies have been shown in a number of clinical trials to be effective in treating IBS (Bonnert et al., 2017; Everitt et al., 2019; Lackner et al., 2018). Despite the interplay between gut bacteria and emotional processing, it is unclear if these strategies affect or are affected by gut microbiota composition.

In contrast, changes in diet have been shown to not only improve IBS symptoms but also to be dependent on baseline gut microbiota composition. A randomized controlled trial compared a traditional IBS diet (e.g., portion control, frequency, and fiber intake) to a low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (low FODMAP) diet and found that both interventions reduced IBS symptoms (Bohn et al., 2015). Non-responders to the low FODMAP group, but not the traditional IBS diet group, had an increased abundance of Bacteroides stercoris, Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter, and Desulfitispora suggesting that baseline composition may predict who is most likely to benefit (Bennet et al., 2018). The ability to predict responsiveness to a low FODMAP diet from baseline gut microbiome composition also has been reported in children (Chumpitazi et al., 2015). Similarly, increasing intake of soluble dietary fiber also has been shown to be effective in adults and children with IBS (Bijkerk et al., 2009; Shulman et al., 2017).

Comprehensive self-management interventions include components of cognitive and behavioral strategies as well as dietary education. In several randomized studies, including our own, comprehensive self-management interventions have been effective in reducing symptoms and improving quality of life (Heitkemper et al., 2004; Labus et al., 2013; Ringström et al., 2012). Our Comprehensive Self-Management (CSM) intervention was designed with components of cognitive behavioral therapy, relaxation, and dietary education (Heitkemper et al., 2004; Hsueh et al., 2011; Jarrett et al., 2016; Jarrett et al., 2009).

Given the above described relationships between emotion processing and stress and the gut microbiome and between improvement in IBS symptoms and changes in diet/gut microbiome, we carried out secondary analyses of our previously published CSM intervention to explore if: 1) Baseline gut microbiome composition predicted response to the effectiveness of the CSM intervention in reducing symptoms and improving quality of life; 2) The CSM intervention resulted in a different gut microbiome composition compared to the control group (usual care).

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This study is a secondary data analysis of a randomized controlled trial comparing the effects of a comprehensive self-management intervention to usual care on abdominal pain and quality of life (clinicaltrials.gov identifier: NCT00907790; Jarrett et al., 2016).

Sample

Potential participants were recruited from local gastroenterology clinics using direct mailings and community advertisements. Inclusion criteria included: ages 18–70 years old, history of IBS symptoms for at least 6 months prior to IBS diagnosis by a healthcare provider, experienced symptoms for at least 6 months after diagnosis, and met the Rome-III criteria at the time of the study. Individuals were excluded if medication use (e.g., antibiotics, corticosteroids) or comorbidities (e.g., celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease) would influence the measurement of symptoms, influence the participants’ ability to complete the study, or impact the gut microbiome. Women who were pregnant, breastfeeding, or planning to become pregnant in the next year also were excluded. Human subjects’ institutional review board approval was obtained as well as participant’s consent. Although both men and women were recruited into the parent study, microbiome data were only available on females.

Procedures

Participants meeting eligibility criteria completed a baseline assessment including a 4-week daily symptom diary that was completed each evening and a stool sample collection. Computer adaptive randomization was used to ensure the CSM intervention and usual care (UC) groups were balanced on age, sex, predominant stool consistency, and severity of abdominal pain at baseline. Follow-up data collection of the daily symptom diary, quality of life, and stool samples occurred at 3 months post-randomization. Outcome assessors were blinded to treatment assignment.

Intervention

Complete details regarding the CSM intervention have been published (Barney et al., 2010; Jarrett et al., 2016). Participants randomized to the CSM intervention received 8 individual sessions with an advanced practice psychiatric nurse practitioner. Participants learned about IBS as well as relaxation skills. Cognitive behavioral strategies were tailored to participants and included healthy thought patterns, problem solving, and identifying and challenging false beliefs. Participants completed a symptom and food diary which was reviewed by a registered dietitian. The information was used to develop tailored healthy eating strategies such as identifying which foods were associated with their symptoms, portion sizes, and eating frequent meals. The sessions included discussions on applying strategies to the management of IBS pain control, traveling, and eating out.

Usual Care

Participants in the UC group were notified to continue the treatment recommended by their healthcare provider.

Measures

Participant characteristics

Age, race/ethnicity, education, and IBS subtypes were assessed.

Daily diary measures

Participants completed a daily diary for 4 weeks at baseline and 3 months post-randomization. The daily diary included twenty-six symptoms. For this analysis, we focused on the mean severity of abdominal pain (primary study outcome) and bloating (secondary outcome) which participants rated on a 0–4 scale (not present, mild, moderate, severe, or very severe). In addition, we report on the percent of days reporting loose stool and percent of days reporting hard stool.

Quality of life

The IBS Quality of Life (IBS-QOL) 42-item questionnaire assesses the impact of IBS. Questions include “How often did your IBS make you feel fed up or frustrated?” and “My IBS affected my ability to succeed at work/main activity.” Participants respond on a 5-point Likert scale. Nine subscales are created: sleep, emotional, mental health beliefs, energy, physical functioning, diet, social role, physical role, and sexual relations. Subscales were standardized to a 0 to 100 score and a total score was calculated by averaging all subscales, except diet and sexual relations. A higher score indicates better quality of life (Hahn et al., 1997).

Microbiome

Participants collected stool samples at home and immediately stored them at −20 °C. Frozen samples were transported to the lab and then stored at −80 °C. 16 S rRNA gene sequencing was used to determine fecal microbial communities as previously described (Hollister et al., 2020; Luna et al., 2017). Community DNA was extracted using the PowerSoil DNA extraction kit (MoBIO, Carlsbad, CA); quantity and quality of community DNA were assessed using fluorometric methods (Qubit, Waltham, MA). Amplicon libraries were prepared using the NEXTflex V4 Amplicon-Seq kit 2.0 (Bioo Scientific, Austin, TX). Sequence libraries were generated using the MiSeq platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

Statistical Analysis

Participant demographics were described using counts and percentages for categorical variables and means and standard deviations for continuous variables. Demographics are presented for both CSM and UC groups. Participants who had microbiome samples with fewer than 10,000 reads were excluded from all analyses, and OTUs appearing in two or fewer samples were excluded from beta diversity analyses (Supplemental Figure 1). Prior to centered log ratio (CLR) transformation, zero proportions were replaced with 5e-5. FDR correction was applied within each set of analyses. Sensitivity analyses were performed using a read count threshold of 5,000 reads; data rarefied to 10,000 reads; and a pseudocount of 0.5 or 1 prior to CLR transformation. All results were qualitatively similar.

To test whether the baseline gut microbiome is associated with efficacy of the CSM intervention, we restricted the analysis to participants in the CSM Intervention group (n = 30). Two subjects were excluded from symptom-based analyses due to missing symptom data. Change scores were calculated as time 2 minus time 1 for each outcome. Shannon diversity index and species richness were computed using the vegan package in R ( vegan: Community Ecology Package, 2019). Linear regression was used to test the association between change in each outcome measure and alpha diversity at baseline (Shannon index or richness), adjusting for the baseline value of the outcome measure. For beta-diversity analyses, MiRKAT was used to test for global associations between the baseline microbiome and change score, adjusting for the baseline value of the outcome measure (Zhao et al., 2015). We considered Bray-Curtis, unweighted UniFrac, and weighted UniFrac kernels. For single-taxon tests, CLR-transformed abundances were used in linear regression analyses as described above. Family and genera were analyzed if they were present in at least 20% of samples. The Firmicutes: Bacteriodetes ratio was computed from untransformed data and log-transformed to reduce right skew.

To consider whether changes in the gut microbiome differed between treatment groups, we restricted the analyses to subjects with microbiome data at both time points; five participants were excluded from the CSM Intervention group accordingly. Those five participants were similar in demographics to the other CSM Intervention participants. Linear regression was used to test whether change in Shannon diversity or richness was associated with treatment group, adjusting for baseline alpha diversity. MiRKAT was used to test whether global changes in the microbiome were associated with treatment group. Distance matrices of changes were generated using paired pldist (Plantinga et al., 2019).

We consider power to detect associations between microbiome dysbiosis at baseline (for example, low alpha diversity) and success of the CSM intervention, using the CSM group only. Since this study takes advantage of existing data (Jarrett et al., 2016), the sample size of 30 is determined as the number of female subjects assigned to CSM with microbiome samples available at baseline and symptoms available at both time points. With a sample size of 30, there is 80% power to detect a correlation of 0.49 between alpha diversity and change in symptom score. If the baseline microbiome is characterized as dysbiotic (30% of subjects) or not dysbiotic (70%), there is 80% power to detect a 1.12 SD difference. Considering the question of whether change from baseline to follow-up microbiome differs between CSM (n = 25) and usual care (n = 25), there is 80% power to detect a difference of 0.81 standard deviations.

Results

Participant Characteristics

Participants had a mean age of 37.9 ± 15.5 years and had been diagnosed for at least 5 years. Approximately half of the sample had IBS-Diarrhea. The CSM intervention and UC groups had similar demographics (Table 1). Fewer participants in the UC group were married or partnered.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Women With Irritable Bowel Syndrome.

| Comprehensive Self-Management Intervention (n = 30) |

Usual Care (n = 25) |

|

|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Age | 39.0 (14.9) | 36.6 (16.5) |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) | 24.7 (4.9) | 24.8 (5.9) |

| Years since diagnosis | 6.3 (6.6) | 5.2 (7.5) |

| n (%) | n (%) | |

| Race, white | 26 (86.7%) | 20 (80.0%) |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 29 (96.7%) | 25 (100.0%) |

| Married/partnered | 17 (56.7%) | 5 (20.0%) |

| Education, college or greater | 20 (69.0%) | 12 (50.0%) |

| Job | ||

| Student | 7 (24.1%) | 8 (34.8%) |

| Professional-Managerial | 13 (44.8%) | 7 (30.4%) |

| Other | 9 (31.0%) | 8 (34.8%) |

| Irritable Bowel Syndrome Subgroups | ||

| IBS-Constipation | 9 (30.0%) | 5 (20.0%) |

| IBS-Diarrhea | 15 (50.0%) | 14 (56.0%) |

| IBS-Mixed | 5 (16.7%) | 5 (20.0%) |

| IBS-Unclassified | 1 (3.3%) | 1 (4.0%) |

Baseline Gut Microbiome and CSM Intervention Effectiveness

Among individuals in the CSM intervention group, Shannon diversity and richness (Table 2) and beta diversity measures (Table 3) at baseline were not associated with effectiveness of the CSM intervention at 3 months, as measured by change in abdominal pain and quality of life (all p > 0.4). In addition, alpha and beta diversity measures were not associated with secondary outcomes of change in bloating or percent of days with loose or hard stool. Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio did not predict who benefited from the CSM intervention. Families or genera present in >20% of subjects were not significantly associated with the effectiveness of the CSM intervention at 3 months when corrected for multiple comparisons (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Association Between Change Score for the Indicated Symptom and Alpha Diversity at Baseline in the CSM Treatment Group, Adjusting for Baseline Value of the Symptom.

| Outcome | Measure | Regression Coefficient | Partial Correlation | p-Value | FDR p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Abdominal Pain | Shannon | −0.097 | −0.107 | 0.596 | 0.851 |

| Richness | −0.002 | −0.029 | 0.887 | 0.887 | |

| Quality of Life Score | Shannon | 4.365 | 0.162 | 0.401 | 0.851 |

| Richness | 0.068 | 0.039 | 0.841 | 0.887 | |

| Mean Bloating | Shannon | 0.065 | 0.075 | 0.711 | 0.887 |

| Richness | 0.014 | 0.243 | 0.223 | 0.743 | |

| % Days with Loose Stool | Shannon | −7.198 | −0.155 | 0.439 | 0.851 |

| Richness | -1.007 | −0.336 | 0.086 | 0.743 | |

| % Days with Hard Stool | Shannon | 9.676 | 0.262 | 0.187 | 0.743 |

| Richness | 0.278 | 0.114 | 0.572 | 0.851 |

Note. Mean abdominal score and mean bloating range from 0 = not present to 4 = very severe. Quality of life ranges from 0 to 100 with a higher score indicating better quality of life. The regression coefficient indicates the average difference in change score (time 2 symptom minus baseline symptom) associated with a one-unit higher alpha diversity value, holding baseline symptom value constant. For example, the coefficient of −1.007 in the last line of the table indicates:

A subject with one additional bacterial genus at baseline (=1 higher richness) is expected to have about 1% fewer days with loose stool per month than a comparable subject (same baseline loose stool) without the additional genus.

Table 3.

p-Values from Analysis of Baseline Microbiome Beta Diversity (Representing Global Similarity in Baseline Microbiome) and Similarity in Change Scores Within the CSM Treatment Group, Adjusting for Baseline Value of the Outcome Measure.

| Outcome | Bray-Curtis | Unweighted UniFrac | Weighted UniFrac | Omnibus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Abdominal Pain | 0.816 | 0.821 | 0.949 | 0.974 |

| Quality of Life Score | 0.598 | 0.890 | 0.769 | 0.830 |

| Mean Bloating | 0.994 | 0.993 | 0.989 | 1.000 |

| % Days with Loose Stool | 0.975 | 0.130 | 0.841 | 0.276 |

| % Days with Hard Stool | 0.520 | 0.030 | 0.510 | 0.064 |

Note. Mean abdominal score and mean bloating range from 0 = not present to 4 = very severe. Quality of life ranges from 0 to 100 with a higher score indicating better quality of life.

Difference Between Baseline and Follow-Up Gut Microbiome

There were no significant differences in the microbiome between intervention and usual care at baseline (Shannon diversity p = 0.82, richness p = 0.87, beta-diversity p = 0.59). The degree of dissimilarity between baseline and follow-up microbiome, based on both alpha and beta diversity, did not differ between CSM intervention and UC groups. Mean change in Shannon diversity in the CSM group was −0.02 (SD 0.32, IQR −0.25 to 0.21); in the UC group, mean change was 0.01 (SD 0.38, IQR −0.26 to 0.13, Figure 1). That is, the distribution of changes in alpha diversity was nearly identical between treatment groups. A similar conclusion can be drawn when comparing beta diversity of changes in the microbiome. The PCoA plot of global dissimilarity between subjects’ microbiome changes shows no clustering by treatment group (Figure 2A). The distribution of dissimilarity values are similar within and across groups, indicating that global changes in the microbiome are no more similar among subjects in the same treatment group than subjects in different treatment groups (Figure 2B). Specifically, average within-CSM dissimilarity is 0.0042 (SD 0.0013), average within-UC dissimilarity is 0.0046 (SD 0.0013), and the average dissimilarity between subjects in different groups is 0.0046 (SD 0.0015), where the paired quantitative Bray-Curtis measure is used to quantify dissimilarity between subjects. As shown in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, differences in families or genera present in >20% of subjects were not significant when controlled for multiple comparisons.

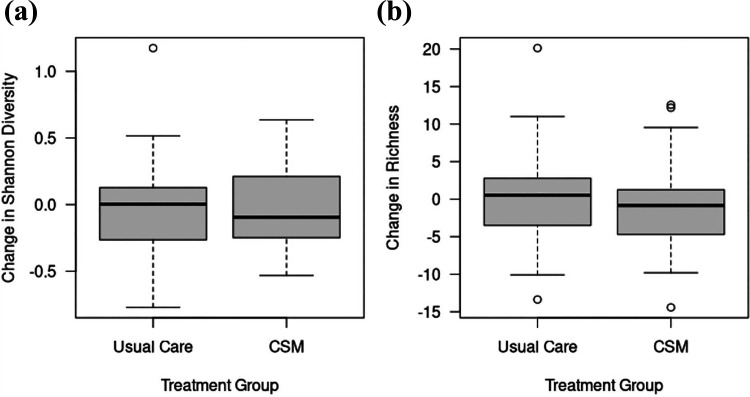

Figure 1.

Change in alpha-diversity measures (a) Shannon diversity and (b) richness between baseline and follow up for women in usual care and CSM intervention. Alpha-diversity: p = 0.862 for association between change in Shannon and treatment group; p = 0.583 for association between change in richness and treatment group (both adjusted for baseline alpha-diversity).

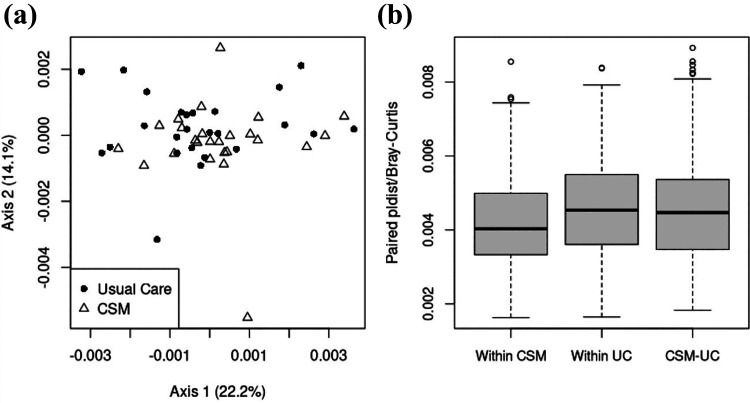

Figure 2.

Global dissimilarity in changes in the microbiome between baseline and follow-up for women in usual care and CSM intervention. (a): PCoA plot using paired pldist with the quantitative Bray-Curtis dissimilarity. (b): Box plot of dissimilarity values (paired pldist/quantitative Bray-Curtis) within each treatment group and across groups. Beta-diversity: p = 0.523 for association between change in microbiome and treatment group.

Discussion

Baseline phyla, family, genus, and diversity measures of the gut microbiome did not predict symptom and quality of life improvement at 3 months post-randomization among women with IBS randomized to a comprehensive self-management intervention. In addition, there was no evidence of systematic change between baseline and follow-up microbiome in either treatment group, irrespective of clinical improvement. These findings occurred for global microbiome measures. Global exploratory analysis showed no family or genera that predicted treatment effectiveness or changed from baseline to 3-month post-randomization follow-up.

In an intervention with CBT and dietary education, baseline microbiome was unable to predict treatment effectiveness, extending the findings of other dietary-only interventions. For instance, Bennet and colleagues (2018) found that among adults with IBS, baseline microbiome did not discriminate between responders and non-responders to traditional IBS diet education, whereas baseline microbiome discriminated between responders and non-responders placed on a low FODMAP diet (non-responders having increased Streptococcus, Dorea, Ruminococcus gnavus, Desulfitispora, Bacteroides stercoris, Pseudomonas, and Acinetobacter). In addition, the current study adds to the literature regarding the stability of the gut microbiome in spite of traditional diet education and lifestyle modification in the short term (3 months; Wu et al., 2011). Our previous work identified individuals randomized to an earlier CSM intervention increased their intake of soluble and insoluble fiber by 1 gram per day, which persisted to 12 months post-randomization (Hsueh et al., 2011). Fiber has been associated with an increase in microbiota diversity and abundance as well as secondary bile acids in the feces (Jefferson & Adolphus, 2019; Singh et al., 2019), although higher fiber intake may be needed to modify the gut microbiome.

Previous research comparing traditional IBS dietary recommendations and a low FODMAP diet found that only participants in the low FODMAP diet demonstrated a change in bacterial composition (Bennet et al., 2018). Thus, although traditional dietary advice may lead to symptom reduction when combined with CBT intervention (Bohn et al., 2015; Jarrett et al., 2016), more intensive dietary interventions such as the low FODMAP diet may be needed to influence the gut microbiome (Biesiekierski et al., 2019). It could be that traditional dietary advice includes changing multiple dietary components which, while making small individual changes, may not lead to an overall effect, since different food items may differentially impact microbiome (Windgassen et al., 2017). Alternatively, the gut microbiome may remain stable even during dietary alterations.

Few studies have examined the relationship between the gut microbiome and CBT interventions. A preliminary report in a research abstract identified that men and women with IBS (N = 49) who responded to CBT with a reduced IBS Symptom Severity Score had increased levels of genus Roseburia and Lachnobacterium and decreased Bacteroides, Parabacteroides, and Prevotella at baseline compared to those who did not respond to a 4-week CBT intervention (Jacobs et al., 2018). Since few studies have examined this potential relationship between a comprehensive program like CSM or specifically CBT and the gut microbiome and its metabolites (Schnorr & Bachner, 2016), additional research is needed to build the evidence regarding if the microbiome can modulate central processes and/or whether central processes alter gut bacteria (O’Mahony et al., 2015; Valles-Colomer et al., 2019; van de Wouw et al., 2018). Alternatively, it potentially points to other mechanisms which influence the relationship between CBT and improved outcomes. As CBT has been shown to influence brain processes (Yoshino et al., 2018), it could be that CBT works through a central mechanism such as reduction of anxiety, catastrophizing, or pain sensitivity (Windgassen et al., 2017, 2019).

Although the gut microbiome-brain axis is hypothesized to play a role in IBS, few studies have examined the gut microbiome before and after CBT treatment. The gut microbiome may influence central nervous system and cognition through metabolites such as bile and short chain fatty acids, tryptophan, and lipopolysaccharides (Zhu et al., 2020). In the current study, CBT which included dietary education also did not influence the gut microbiome as measured by 16S rRNA. However, it could be that the functionality of the bacteria and which metabolites are produced is more important than which bacteria are present.

This study has several limitations. These findings can be generalized to females with IBS. Specific IBS subtype differences were not investigated and could confound disease specific findings but such an approach was underpowered in the present study. Future studies examining sex/gender and IBS subtype differences are needed. Although individuals made dietary changes, information on dietary nutrients was not collected and therefore it is not clear what specific dietary components participants may have modified. Sample size may also limit the interpretation of these results. This study does have the strength of utilizing a prospective daily symptom diary to assess symptoms of abdominal pain and bloating.

Clinical and Nursing Implications

In a nurse-delivered comprehensive self-management intervention which included traditional IBS dietary education and CBT, measures of the gut microbiome did not predict improvement in symptom and quality of life. Additional research is needed to determine biomarkers that may predict response to intervention in order to provide a precision health approach to IBS self-management. Furthermore, more intensive dietary interventions, such as the low FODMAP diet, may be needed to influence the gut microbiome.

In conclusion, baseline microbiome does not appear to predict the effectiveness of a comprehensive self-management intervention. In addition, the CSM intervention did not appear to drive changes in the microbiome between baseline and follow-up. Further research is needed to examine the role of the microbiome in predicting effectiveness of CBT and dietary interventions among IBS in order to develop a precision treatment approach.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-brn-10.1177_1099800420984543 for A Comprehensive Self-Management Program With Diet Education Does Not Alter Microbiome Characteristics in Women With Irritable Bowel Syndrome by Kendra J. Kamp, Anna M. Plantinga, Kevin C. Cain, Robert L. Burr, Pamela Barney, Monica Jarrett, Ruth Ann Luna, Tor Savidge, Robert Shulman and Margaret M. Heitkemper in Biological Research For Nursing

Supplemental Material, sj-xlsx-1-brn-10.1177_1099800420984543 for A Comprehensive Self-Management Program With Diet Education Does Not Alter Microbiome Characteristics in Women With Irritable Bowel Syndrome by Kendra J. Kamp, Anna M. Plantinga, Kevin C. Cain, Robert L. Burr, Pamela Barney, Monica Jarrett, Ruth Ann Luna, Tor Savidge, Robert Shulman and Margaret M. Heitkemper in Biological Research For Nursing

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Kamp, K.J. contributed to conception and design, contributed to analysis and interpretation, drafted manuscript, gave final approval, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. Plantinga, A.M. contributed to conception and design, contributed to analysis and interpretation, drafted manuscript, gave final approval, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. Cain, K.C. contributed to conception and design, contributed to analysis and interpretation, critically revised manuscript, gave final approval, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. Burr, R.L. contributed to conception and design, contributed to analysis and interpretation, critically revised manuscript, gave final approval, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy Barney, P., contributed to design contributed to acquisition and interpretation critically revised manuscript gave final approval agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. Jarrett, M. contributed to design, contributed to acquisition and interpretation, critically revised manuscript, gave final approval, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. Luna, R.A. contributed to analysis, critically revised manuscript, gave final approval, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. Savage, T. contributed to analysis, critically revised manuscript, gave final approval, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. Shulman, R. contributed to conception, contributed to interpretation, critically revised manuscript, gave final approval, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy. Heitkemper, M.M. contributed to conception and design, contributed to acquisition and interpretation, drafted manuscript, gave final approval, and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Nursing Research, R01NR004142. Kendra J. Kamp was supported, in part, by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, T32DK007742. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ORCID iD: Kendra J. Kamp  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7753-3564

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7753-3564

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Allen A. P., Hutch W., Borre Y. E., Kennedy P. J., Temko A., Boylan G., Murphy E., Cryan J. F., Dinan T. G., Clarke G. (2016). Bifidobacterium longum 1714 as a translational psychobiotic: Modulation of stress, electrophysiology and neurocognition in healthy volunteers. Translational Psychiatry, 6(11), e939–e939. 10.1038/tp.2016.191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennet S. M. P., Bohn L., Storsrud S., Liljebo T., Collin L., Lindfors P., Tornblom H., Ohman L., Simren M. (2018). Multivariate modelling of faecal bacterial profiles of patients with IBS predicts responsiveness to a diet low in FODMAPs. Gut, 67(5), 872–881. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennet S. M. P., Ohman L., Simren M. (2015). Gut microbiota as potential orchestrators of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut Liver, 9(3), 318–331. 10.5009/gnl14344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barney P., Weisman P., Jarrett M., Levy R. L., Heitkemper M. (2010). Master your IBS: An 8-week plan proven to control the symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. AGA Press. [Google Scholar]

- Biesiekierski J. R., Jalanka J., Staudacher H. M. (2019). Can gut microbiota composition predict response to dietary treatments? Nutrients, 11(5), 1134. 10.3390/nu11051134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bijkerk C. J., de Wit N. J., Muris J. W., Whorwell P. J., Knottnerus J. A., Hoes A. W. (2009). Soluble or insoluble fibre in irritable bowel syndrome in primary care? Randomised placebo controlled trial. BMJ, 339, b3154. 10.1136/bmj.b3154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn L., Storsrud S., Liljebo T., Collin L., Lindfors P., Tornblom H., Simren M. (2015). Diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome as well as traditional dietary advice: A randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology, 149(6), 1399–1407. e1392. 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnert M., Olén O., Lalouni M., Benninga M. A., Bottai M., Engelbrektsson J., Hedman E., Lenhard F., Melin B., Simrén M., Vigerland S., Serlachius E., Ljótsson B. (2017). Internet-delivered cognitive behavior therapy for adolescents with irritable bowel syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 112(1), 152–162. 10.1038/ajg.2016.503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong P. P., Chin V. K., Looi C. Y., Wong W. F., Madhavan P., Yong V. C. (2019). The microbiome and irritable bowel syndrome—A review on the pathophysiology, current research and future therapy. Frontiers in Microbiology, 10, 1136–1136. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumpitazi B. P., Cope J. L., Hollister E. B., Tsai C. M., McMeans A. R., Luna R. A., Versalovic J., Shulman R. J. (2015) Randomised clinical trial: gut microbiome biomarkers are associated with clinical response to a low FODMAP diet in children with the irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 42(4), 418–427. 10.1111/apt.13286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doshi J. A., Cai Q., Buono J. L., Spalding W. M., Sarocco P., Tan H., Stephenson J. J., Carson R. T. (2014). Economic burden of irritable bowel syndrome with constipation: A retrospective analysis of health care costs in a commercially insured population. Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, 20(4), 382–390. 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.4.382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drossman D. A. (2016). Functional gastrointestinal disorders: History, pathophysiology, clinical features and Rome IV. Gastroenterology, 150(6), 1262–1279. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt H. A., Landau S., O’Reilly G., Sibelli A., Hughes S., Windgassen S., Holland R., Little P., McCrone P., Bishop F., Goldsmith K., Coleman N., Logan R., Chalder T., Moss-Morris R. (2019). Assessing telephone-delivered cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) and web-delivered CBT versus treatment as usual in irritable bowel syndrome (ACTIB): A multicentre randomised trial. Gut, 68(9), 1613–1623. 10.1136/gutjnl-2018-317805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn B. A., Kirchdoerfer L. J., Fullerton S., Mayer E. (1997). Evaluation of a new quality of life questionnaire for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 11(3), 547–552. 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.00168.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitkemper M. M., Jarrett M. E., Levy R. L., Cain K. C., Burr R. L., Feld A., Barney P., Weisman P. (2004). Self-management for women with irritable bowel syndrome. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2(7), 585–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heym N., Heasman B. C., Hunter K., Blanco S. R., Wang G. Y., Siegert R., Cleare A., Gibson G. R., Kumari V., Sumich A. L. (2019). The role of microbiota and inflammation in self-judgement and empathy: Implications for understanding the brain-gut-microbiome axis in depression. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 236(5), 1459–1470. 10.1007/s00213-019-05230-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollister E. B., Cain K. C., Shulman R. J., Jarrett M. E., Burr R. L., Ko C., Zia J., Han C. J., Heitkemper M. M. (2020). Relationships of microbiome markers with extraintestinal, psychological distress and gastrointestinal symptoms, and quality of life in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 54(2), 175–183. 10.1097/mcg.0000000000001107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh H.-F., Jarrett M. E., Cain K. C., Burr R. L., Deechakawan W., Heitkemper M. M. (2011). Does a self-management program change dietary intake in adults with irritable bowel syndrome? Gastroenterology Nursing, 34(2), 108–116. 10.1097/SGA.0b013e31821092e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huo R., Zeng B., Zeng L., Cheng K., Li B., Luo Y., Wang H., Zhou C., Fang L., Li W., Niu R., Wei H., Xie P. (2017). Microbiota modulate anxiety-like behavior and endocrine abnormalities in hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 7, 489. 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs J. P., Lackner J. M., Lagishetty V., Gudleski G. D., Firth R. S., Tillisch K., Naliboff B. D., Labus J. S., Mayer E. A. (2018). 915—intestinal microbiota predict response to cognitive behavioral therapy for irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology, 154(6), S–181. 10.1016/S0016-5085(18)31017-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett M. E., Cain K. C., Barney P. G., Burr R. L., Naliboff B. D., Shulman R., Zia J., Heitkemper M. M. (2016). Balance of autonomic nervous system predicts who benefits from a self-management intervention program for irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 22(1), 102–111. 10.5056/jnm15067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett M. E., Cain K. C., Burr R. L., Hertig V. L., Rosen S. N., Heitkemper M. M. (2009). Comprehensive self-management for irritable bowel syndrome: Randomized trial of in-person vs. combined in-person and telephone sessions. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 104(12), 3004–3014. 10.1038/ajg.2009.479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jefferson A., Adolphus K. (2019). The effects of intact cereal grain fibers, including wheat bran on the gut microbiota composition of healthy adults: A systematic review. Frontiers in Nutrition, 6, 33. 10.3389/fnut.2019.00033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ju T., Naliboff B. D., Shih W., Presson A. P., Liu C., Gupta A., Mayer E. A., Chang L. (2020). Risk and protective factors related to early adverse life events in irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, 54(1), 63–69. 10.1097/mcg.0000000000001153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labus J., Gupta A., Gill H. K., Posserud I., Mayer M., Raeen H., Bolus R., Simren M., Naliboff B. D., Mayer E. A. (2013). Randomised clinical trial: Symptoms of the irritable bowel syndrome are improved by a psycho-education group intervention. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 37(3), 304–315. 10.1111/apt.12171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner J. M., Jaccard J., Keefer L., Brenner D. M., Firth R. S., Gudleski G. D., Hamilton F. A., Katz L. A., Krasner S. S., Ma C.-X., Radziwon C. D., Sitrin M. D. (2018). Improvement in gastrointestinal symptoms after cognitive behavior therapy for refractory irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology, 155(1), 47–57. 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.03.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. N., Wu H., Chen Y. Z., Chen Y. J., Shen X. Z., Liu T. T. (2017). Altered molecular signature of intestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome patients compared with healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Digestive and Liver Disease, 49(4), 331–337. 10.1016/j.dld.2017.01.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luna R. A., Oezguen N., Balderas M., Venkatachalam A., Runge J. K., Versalovic J., Veenstra-VanderWeele J., Anderson G. M., Savidge T., Williams K. C. (2017). Distinct microbiome-neuroimmune signatures correlate with functional abdominal pain in children with autism spectrum disorder. Cellular and Molecular Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 3(2), 218–230. 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2016.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mari A., Abu Baker F., Mahamid M., Sbeit W., Khoury T. (2020). The evolving role of gut microbiota in the management of irritable bowel syndrome: An overview of the current knowledge. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(3). 10.3390/jcm9030685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mars R. A. T., Yang Y., Ward T., Houtti M., Priya S., Lekatz H. R., Tang X., Sun Z., Kalari K. R., Korem T., Bhattarai Y., Zheng T., Bar N., Frost G., Johnson A. J., van Treuren W., Han S., Ordog T., Grover M., Sonnenburg J., D’Amato M., Camilleri M., Elinav E., Segal E., Blekhman R., Farrugia G., Swann J. R., Knights D., Kashyap P. C. (2020). Longitudinal multi-omics reveals subset-specific mechanisms underlying irritable bowel syndrome. Cell, 182(6), 1460–1473. e1417. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser G., Fournier C., Peter J. (2018). Intestinal microbiome-gut-brain axis and irritable bowel syndrome. Wiener medizinische Wochenschrift (1946), 168(3–4), 62–66. 10.1007/s10354-017-0592-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar K., Nawaz H., Abid S. (2019). Functional gastrointestinal disorders and gut-brain axis: What does the future hold? World Journal of Gastroenterology, 25(5), 552–566. 10.3748/wjg.v25.i5.552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Mahony S. M., Clarke G., Borre Y. E., Dinan T. G., Cryan J. F. (2015). Serotonin, tryptophan metabolism and the brain-gut-microbiome axis. Behavioural Brain Research, 277, 32–48. 10.1016/j.bbr.2014.07.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimentel M., Lembo A. (2020). Microbiome and its role in irritable bowel syndrome. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 65, 829–839. 10.1007/s10620-020-06109-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plantinga A. M., Chen J., Jenq R. R., Wu M. C. (2019). PLDIST: Ecological dissimilarities for paired and longitudinal microbiome association analysis. Bioinformatics, 35(19), 3567–3575. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ringström G., Störsrud S., Simrén M. (2012). A comparison of a short nurse-based and a long multidisciplinary version of structured patient education in irritable bowel syndrome. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 24(8), 950–957. 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328354f41f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodiño-Janeiro B. K., Vicario M., Alonso-Cotoner C., Pascua-García R., Santos J. (2018). A review of microbiota and irritable bowel syndrome: Future in therapies. Advances in Therapy, 35(3), 289–310. 10.1007/s12325-018-0673-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnorr S. L., Bachner H. A. (2016). Integrative therapies in anxiety treatment with special emphasis on the gut microbiome. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 89(3), 397–422. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman R. J., Hollister E. B., Cain K., Czyzewski D. I., Self M. M., Weidler E. M., Devaraj S., Luna R. A., Versalovic J., Heitkemper M. (2017). Psyllium fiber reduces abdominal pain in children with irritable bowel syndrome in a randomized, double-blind trial. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 15(5), 712–719. e714. 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.03.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson C. A., Mu A., Haslam N., Schwartz O. S., Simmons J. G. (2020). Feeling down? A systematic review of the gut microbiota in anxiety/depression and irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of Affective Disorders, 266, 429–446. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.01.124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh J., Metrani R., Shivanagoudra S. R., Jayaprakasha G. K., Patil B. S. (2019). Review on bile acids: Effects of the gut microbiome, interactions with dietary fiber, and alterations in the bioaccessibility of bioactive compounds. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 67(33), 9124–9138. 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b07306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperber A. D., Dumitrascu D., Fukudo S., Gerson C., Ghoshal U. C., Gwee K. A., Hungin A. P. S., Kang J.-Y., Minhu C., Schmulson M., Bolotin A., Friger M., Freud T., Whitehead W. (2017). The global prevalence of IBS in adults remains elusive due to the heterogeneity of studies: A Rome Foundation working team literature review. Gut, 66(6), 1075. 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillisch K., Mayer E. A., Gupta A., Gill Z., Brazeilles R., Le Nevé B., van Hylckama Vlieg J. E. T., Guyonnet D., Derrien M., Labus J. S. (2017). Brain structure and response to emotional stimuli as related to gut microbial profiles in healthy women. Psychosomatic Medicine, 79(8), 905–913. 10.1097/psy.0000000000000493 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valles-Colomer M., Falony G., Darzi Y., Tigchelaar E. F., Wang J., Tito R. Y., Schiweck C., Kurilshikov A., Joossens M., Wijmenga C., Claes S., Van Oudenhove L., Zhernakova A., Vieira-Silva S., Raes J. (2019). The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nature Microbiology, 4(4), 623–632. 10.1038/s41564-018-0337-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Wouw M., Boehme M., Lyte J. M., Wiley N., Strain C., O’Sullivan O., Clarke G., Stanton C., Dinan T. G., Cryan J. F. (2018). Short-chain fatty acids: Microbial metabolites that alleviate stress-induced brain-gut axis alterations. The Journal of Physiology, 596(20), 4923–4944. 10.1113/jp276431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- vegan: Community Ecology Package. (2019). Version Version R package version 2.5-6). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan

- Vodička M., Ergang P., Hrnčíř T., Mikulecká A., Kvapilová P., Vagnerová K., Šestáková B., Fajstová A., Hermanová P., Hudcovic T., Kozáková H., Pácha J. (2018). Microbiota affects the expression of genes involved in HPA axis regulation and local metabolism of glucocorticoids in chronic psychosocial stress. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 73, 615–624. 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Alammar N., Singh R., Nanavati J., Song Y., Chaudhary R., Mullin G. E. (2020). Gut microbial dysbiosis in the irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 120(4), 565–586. 10.1016/j.jand.2019.05.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windgassen S., Moss-Morris R., Chilcot J., Sibelli A., Goldsmith K., Chalder T. (2017). The journey between brain and gut: A systematic review of psychological mechanisms of treatment effect in irritable bowel syndrome. British Journal of Health Psychology, 22(4), 701–736. 10.1111/bjhp.12250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windgassen S., Moss-Morris R., Goldsmith K., Chalder T. (2019). Key mechanisms of cognitive behavioural therapy in irritable bowel syndrome: The importance of gastrointestinal related cognitions, behaviours and general anxiety. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 118, 73–82. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G. D., Chen J., Hoffmann C., Bittinger K., Chen Y.-Y., Keilbaugh S. A., Bewtra M., Knights D., Walters W. A., Knight R., Sinha R., Gilroy E., Gupta K., Baldassano R., Nessel L., Li H., Bushman F. D., Lewis J. D. (2011). Linking long-term dietary patterns with gut microbial enterotypes. Science (New York, N.Y.), 334(6052), 105–108. 10.1126/science.1208344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino A., Okamoto Y., Okada G., Takamura M., Ichikawa N., Shibasaki C., Yokoyama S., Doi M., Jinnin R., Yamashita H., Horikoshi M., Yamawaki S. (2018). Changes in resting-state brain networks after cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Psychological Medicine, 48(7), 1148–1156. 10.1017/s0033291717002598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N., Chen J., Carroll I. M., Ringel-Kulka T., Epstein M. P., Zhou H., Zhou J. J., Ringel Y., Li H., Wu M. C. (2015). Testing in microbiome-profiling studies with MiRKAT, the microbiome regression-based kernel association test. American Journal of Human Genetics, 96(5), 797–807. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Jiang Y., Xu K., Cui M., Ye W., Zhao G., Jin L., Chen X. (2020). The progress of gut microbiome research related to brain disorders. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 17(1), 25. 10.1186/s12974-020-1705-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material, sj-pdf-1-brn-10.1177_1099800420984543 for A Comprehensive Self-Management Program With Diet Education Does Not Alter Microbiome Characteristics in Women With Irritable Bowel Syndrome by Kendra J. Kamp, Anna M. Plantinga, Kevin C. Cain, Robert L. Burr, Pamela Barney, Monica Jarrett, Ruth Ann Luna, Tor Savidge, Robert Shulman and Margaret M. Heitkemper in Biological Research For Nursing

Supplemental Material, sj-xlsx-1-brn-10.1177_1099800420984543 for A Comprehensive Self-Management Program With Diet Education Does Not Alter Microbiome Characteristics in Women With Irritable Bowel Syndrome by Kendra J. Kamp, Anna M. Plantinga, Kevin C. Cain, Robert L. Burr, Pamela Barney, Monica Jarrett, Ruth Ann Luna, Tor Savidge, Robert Shulman and Margaret M. Heitkemper in Biological Research For Nursing