Abstract

Diet provides energy and nutrition for human survival, and also provides various joy of taste. Extensive studies have shown that the major components of diet, such as protein, carbohydrate and fat, play important roles in regulating aging and longevity. Whether other dietary ingredients can help prevent aging and extend longevity is a very interesting question. Here based on recent findings, we discussed dietary plant ingredients that can extend longevity by regulation of metabolism, targeting TRP channels, mitophagy, senescence pathways and circadian rhythms. Better understanding of the detailed effects and mechanisms of dietary ingredients on longevity regulation, would be helpful for developing new intervention tools for preventing aging and aging related diseases.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11130-021-00946-z.

Keywords: Phytochemical, Aging, Metabolism, Capsaicin, Urolithin a, Fisetin, Nobiletin

Introduction

Aging is a process that leads to progressive functional decline of organs over time, and increase risk of multiple chronic disorders. The composition of food is important for human health and aging [1]. Extensive studies have shown that both the quantity and quality of the nutrients in the food that we take every day are critical in changing health and disease conditions. Nutritional manipulations, such as calorie restriction, time-restricted feeding, intermittent fasting, protein or specific amino acid restriction, play notable roles in regulating aging and longevity [2–12].

The major components of food, such as protein, carbohydrate and fat, are indeed important in aging regulation. Besides these components, there are dietary ingredients that we do not take every day, or in high amount. Rather, we take some dietary ingredients in a small amount, or take them at certain frequencies.

Phytochemicals are organic compounds produced by plants or fungi. They do not directly regulate the growth, development, or reproduction of vegetables, fruits, or mushrooms, and are classified as secondary metabolites [13]. The healthy promoting effects of fruits and vegetables have been attributed to phytochemicals. For instance, new research showing that, procyanidin C1 (PCC1), a polyphenolic component of grape seed extract, can decrease tumor size and extend lifespan in preclinical animal study [14]. Pomegranate seeds is a rich source of phytochemicals and have demonstrated health promoting effects [15]. Similarly, phytochemicals in Chilean native berries may explain the use of in the of treatment of obesity [16]. The percentage of elder population keeps increasing worldwide. Aging is the most important risk factor of age-related diseases. In this background, scientists have been trying to find effective and safe geroprotective agents. Novel phytochemicals from natural sources may delay aging and prevent age-related diseases.

In this review, based on recent findings, we focus on several interesting dietary phytochemicals that may help extend lifespan by regulation of metabolism. With more understanding of the mechanisms, dietary phytochemicals could possibly be developed to powerful intervention tools for preventing aging and aging related diseases, and promoting health span and lifespan in the near future.

Plant Ingredients Targeting TRP Channels

Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels are cation channels that sense a wide spectrum of ambient temperatures [17]. TRPV1 can detect high temperatures and painful stimuli. Longevity is extended in mice and C. elegans in TRPV1 mutants. TRPA-1 can detect temperature decrease in the environment and has been found to extend lifespan as well. [18, 19].

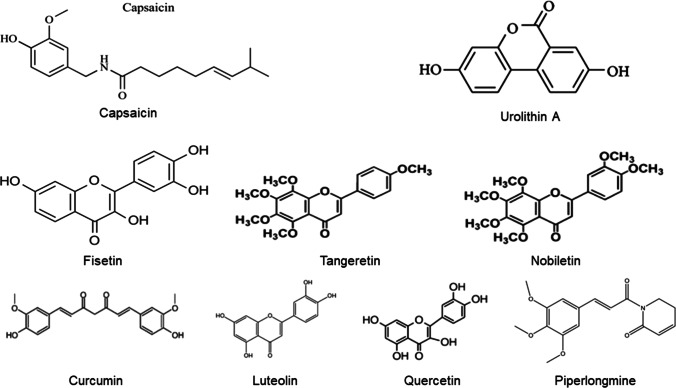

Capsaicin (structure shown in Fig. 1) [20], found in chili pepper, is the agonist of TRPV1 and may have beneficial effect on longevity. This is supported by several human surveys on diets rich in capsaicin (Supplementary Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Structure of molecules

In a recent study conducted in Italy [21], the researchers studied 22,811 residents who participated in the Moli-sani Study (2005 to 2010). The researchers conducted a follow-up survey of participants’ health conditions for median follow-up of 8.2 years and compared their eating habits. The results found that people who regularly eat chili pepper (at least four times a week) demonstrated 23% reduction in the risk of all-cause mortality, and their cerebrovascular mortality was reduced by more than half. An interesting fact is that, even for people who do not follow a healthy Mediterranean diet, the intake of chili pepper is still protective against death risk [21]. This suggests the beneficial effect of chili pepper itself on human health.

Prior to the study on chili pepper intake and mortality in Italians, scientists have looked at the health effects of spicy food consumption in Chinese residents, for median follow-up of 7.2 years among 512,891 participants between the ages of 30 and 79 [22]. The results show that relative risk of total mortality was reduced by 14% for people who consumed spicy food 6 or 7 days per week, compared to those who took less than once a week. There are also significant inverse associations between spicy food consumption and cancer, ischemic heart diseases, or respiratory disease caused mortalities [22].

Besides the surveys conducted in Europe and Asia, research on North American population also supported the positive effect of spicy food consumption on aging. In the study conducted in the United States that followed a median of 18.9 years in 16,179 participants, total mortality was reduced by 12% in participants who consumed hot red chili peppers [23].

The above research in three regions all support the correlation between mortality reduction and spicy food consumption. However, whether these associations are a direct result of the intake of spicy foods, or the consequence of other dietary or lifestyle factors, is not clear. The human population study showed that increase of serum vitamin D may slightly account for the association of the reduced mortality and the intake of chili pepper, while other cardiovascular disease (CVD) related biomarkers did not mediate the association of chili pepper with mortality [21].

To find out whether the main bioactive component of chili pepper, capsaicin, play a role in aging, we tested the effect of capsaicin on lifespan in Drosophila melanogaster. We found that low concentration of capsaicin could extend lifespan only in females, but not in males [24]. Capsaicin did not change food intake, reproductive fitness, or stress resistance. Decrease in spontaneous activity and the reduction in energy expenditure probably explained the positive effect of capsaicin [24]. The dosage of capsaicin could be important, as research shows that capsaicin produces health benefits only at low and moderate doses, whereas high doses are toxic and can even promote cancer [25, 26]. Hot pepper (Capsicum annuum), or chili, is an ancient Latin American crop rich in capsaicin [27]. Chili and capsaicinoids consumption, especially capsaicin, has been reported to have a variety of therapeutic uses, such as anti-obesity effects, antioxidant activity and cardiovascular protection, antimicrobial activity, treatment of urinary disorders, anti-cancer activity, and analgesic activity [27]. There are clinical research showing the therapeutic effects of capsaicin in humans. For example, patients with idiopathic rhinitis benefited from intranasal treatment with capsaicin. Expression of TRPV1 was reduced in patients after capsaicin treatment. The initial neuronal excitation evoked by capsaicin was followed by a long-lasting refractory period during which, the previously excited neurons no longer responded to a wide range of stimuli [28]. In clinical trials on the sensory and gastrointestinal satiety effects of capsaicin on food intake, 0.9 g red pepper (0.25% capsaicin; 80,000 Scoville thermal units) or a placebo was swallowed with tomato juice, at 30 min before each meal. It was found that in the short term, oral and gastrointestinal exposure to capsaicin can increase satiety and reduce energy and fat intake [29].

TRPV1 knockout mice are long-lived and show decreased production of neuropeptide calcitonin-gene-related peptide (CGRP), which subsequently promotes metabolic health (Supplementary Fig. 1A) [18]. It is interesting that, being an agonist of TRPV1, capsaicin in diet produces health benefits. Capsaicin could over-stimulate TRPV1 neurons and cause them to die [18], and lead to eventual loss of TRPV1 function. TRPV1 protein may play different roles in different tissues as well. For example, activation of TRPV1 can also cause production of anandamide (an endogenous cannabinoid), which regulates the immune homeostasis of the gut in mice (Supplementary Fig. 1B) [30]. In addition, capsaicin could have other signaling pathways besides TRPV1. More in-depth research to understand how dietary chili pepper and capsaicin exert beneficial effects on human health and prevent aging, would provide more evidence on dietary recommendations.

In C. elegans, the cold-sensitive TRPA1 channel functions to detect decrease in environmental temperature and increase lifespan as well, by initiating calcium influx that eventually signals to the transcription factor DAF-16/FOXO (Supplementary Fig. 1C) [19, 31]. Loss of TRPA1 shortens lifespan at cold temperatures but not at warm temperatures, and over-expressing wild-type TRPA1 can extend lifespan at cold temperatures in C. elegans. Similarly, transgenic expression of human TRPA1 in worms promotes longevity at cold temperatures but not at warm temperatures. Interestingly, human TRPA1 can be activated by pungent chemical agonists, such as AITC (allyl isothiocyanate), to extend lifespan at warm temperatures, and acts via the same pathway as worm TRPA1 [19, 31]. AITC is a dietary ingredient from the plants, such as Armoracia rusticana or the seeds of Brassica hirta Moench, and gives the spicy flavor of wasabi and mustard oil. This finding suggests that allyl isothiocyanate may have anti-aging effect in humans by activation of TRPA1 channel. It would be interesting to find out more dietary ingredients from plants that can activate other TRP channels and extend lifespan. A previous study has shown capsiate, capsiconiate, capsainol from hot and sweet peppers, several piperine analogs from black pepper, gingeriols and shogaols from ginger, and sanshools and hydroxysanshools from sansho (Japanese pepper) to be TRPV1 agonists [32]. There are also other TRPA1 agonists such as menthol and carvacrol from food ingredients [33].

Plant Ingredients Targeting Mitophagy

Mitochondria is essential for the production of cellular energy and the metabolism. mtDNA mutations lead to the decline of mitochondrial function during aging [34]. Mitophagy, a form of autophagy that eliminates the damaged mitochondria within the cells [35], provides a therapeutic target for health complications associated with aging.

Pomegranate is a popular fruit because of its health benefits [36]. Ellagitannins, an ingredient in pomegranate, can be converted by intestinal microbes into urolithins, such as urolithin A [37]. Recent findings show that urolithin A has promising lifespan prolonging effect.

Urolithin A (Structure in Fig. 1) was found to be mitophagy activator, and therefore prevent dysfunctional mitochondria accumulation [38]. Research showed that the in C. elegans, urolithin A feeding from eggs till death yielded a lifespan increase of 45.4%. In addition, urolithin A has the function of preventing the malicious accumulation of dysfunctional mitochondria in cells.

The tests in rodents showed that, for mice on high-fat diet, urolithin A treatment for another eight months from age of 16 months, improved muscle function robustly compared with the control. For animals on normal chow diet, 6-week urolithin A treatment to 22.5 month old mice also achieved the same positive results, showing the running endurance enhanced by 42% at average. Beneficial effect of urolithin A was observed in young rats as well, with improvement in their exercise capacity [38].

Recently, the first human clinical trial (NCT02655393) of urolithin A was conducted to healthy, sedentary elderly human individuals. The results showed a safety profile, and a molecular signature response, which indicated improved mitochondrial health [39]. This supports a promising approach of dietary urolithin A consumption as an intervention to help improve mitochondrial and muscle function, and promote health in late age in humans (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Urolithin A has shown to regulate multiple processes in metabolism. Besides stimulation of mitophagy, Urolithin A also displays anti-inflammatory and anti-obese activity in animal studies. Urolithin A and its synthetic analog UAS03, can enhance gut barrier integrity and reduce inflammation in mice and human cell culture, by activating aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)- nuclear factor erythroid 2–related factor 2 (Nrf2)-dependent pathways [40]. Urolithin A can also increase energy expenditure and prevent diet-induced obesity in mice, by elevating thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue and inducing browning of white adipose tissue [41].

Urolithin A is a first-in-class natural food metabolite confirmed to be effective in human clinical trial that can stimulates mitophagy and improve mitochondrial functions. Mitophagy may be the key in treating age related conditions and diseases. Targeting deubiquitylating enzymes to stimulate mitophagy might be a promising approach [42].

Resveratrol, a polyphenol abundant in mulberries and red grapes, attenuates oxidative damage by activation of mitophagy in Alzheimer’s disease cellular model [43]. In diabetic mouse model, resveratrol inhibits mitophagy and increases mitochondrial biogenesis in skeletal muscle, and therefore prevents skeletal muscle atrophy [44]. Thus, activation and inhibition of mitophagy may both be beneficial, depending on the situation. Further identification of dietary ingredients that prevent aging by regulation of mitophagy, would provide us more understanding of the mechanisms, and provide dietary supplementation approach for promoting mitochondrial health during aging.

Plant Ingredients with Senolytic Activity

With aging, senescent cell burden increases [45]. Senescent cells can release factors, such as proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, to healthy cells nearby, and therefore cause the local and systemic dysfunction [46]. Transplanting senescent cells can lead to physical dysfunction and reduced survival even in young mice. An important finding is that senolytics, which induce apoptosis in senescent cells, can increase health and survival of old mice (Supplementary Fig. 3) [47].

Fisetin (Structure in Fig. 1) [48], a natural flavonoid ingredient from many fruits and vegetables, such as strawberry, demonstrated potent senolytic activity and low side effect, and has been found to have a significant positive effect on the health and longevity of older mice. Both acute and intermittent treatment of fisetin decreased the level of senescence markers in progeroid syndrome mouse model and in aged wild-type mice. In old wild-type mice, fisetin administration can reduce age-related pathology and extend lifespan. Test in human tissues also showed senotherapeutic activity [49].

Fisetin has shown beneficial effects in Alzheimer’s disease model as well. Fisetin feeding to APPswe/PS1dE9 double transgenic AD mice at early life stage, which is from 3 to 12 month old, can prevent progressive memory loss and learning disabilities. This correlates with elevated p25 level and anti-inflammatory pathways [50]. In SAMP8 mice, a model of sporadic AD and dementia, fisetin again reduces cognitive dysfunction, and helps the markers associated with stress, synaptic function and inflammation recover to normal [51].

In addition, fisetin has positive role on metabolism regulation. Fisetin can attenuate metabolic dysfunction in mice on high fructose diet, possibly by suppressing NF-κB and activating the Nrf2 pathway [52]. Fisetin can also alleviate insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in mice on high fat diet [53]. In streptozotocin induced diabetic rat model, fisetin ameliorates the development of diabetic cardiomyopathy injury [54].

There are several flavonoid ingredients from plants that have shown senolytic activity, such as quercetin, curcumin, and luteolin [49]. Quercetin, which is initially identified to have senolytic properties when combined with dasatinib, targets BCL-2 and related anti-apoptotic pathways [55]. The combination of dasatinib plus quercetin can improve physical function and extend lifespan in old rodents [47], and prevent cognitive deficits in mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease [56]. The combination of dasatinib plus quercetin also showed in clinical trial to help improve physical function in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a senescence-associated disease [57]. Recent screening on flavonoids showed that fisetin, curcumin, and luteolin exibited more potent senotherapeutic activity than quercetin [49]. Among these, fisetin is the most potent senolytic. Piperlongumine, which is a natural ingredient from a variety of species in the genus Piper, has been found to be a promising senolytic agent as well [58].

However, a new study showed that fisetin or dasatinib and quercetin cocktail oral treatment had sexually dimorphic and chemical dependent effects on C57BL/6 mice [59]. When fisetin was given monthly to young adulthood mice (4–13 months), markers of aging reduced in males but not females. When Dasatinib plus quercetin was administered to young adulthood mice, accelerated aging was observed in females while there is no effect on males. Thus, the effects of senolytic compounds on aging and health, may be associated with dosage, the timing, sex, and the compounds themselves. Although administration of senolytic compounds is a promising approach for lifespan and healthspan extending therapeutic intervention, further research and evaluation by clinical trials are required before application in human beings.

Plant Ingredients Targeting Circadian Rhythms

The circadian clock orchestrates daily oscillations of essential physiological processes. Rhythm amplitude shows the difference between peak and trough of the circadian cycle, indicating the robustness of oscillation. Reduced amplitude has been associated with pathological conditions [60, 61].

Nobiletin (Structure in Fig. 1), a citrus flavonoid ingredient, has been found to regulate circadian rhythms and delay aging. Nobiletin was found to be able to enhance the clock amplitude in a cell-based circadian reporter assay. In a mouse model of metabolic disorder, nobiletin could effectively enhance the tissue clock protein levels, improve energy metabolism regulation, and prevent metabolic disease [62]. Nobiletin targets retinoid acid receptor-related orphan receptors (RORs), nuclear receptors functioning in the stabilization loop of the molecular oscillator, and demonstrates the beneficial effect in a Clock gene-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 4).

In aged mice fed with a regular diet, nobiletin extended median lifespan, and has beneficial effects on circadian activity, body temperature, sleep and glucose metabolism. When mice were given metabolic challenges by feeding with high fat diet, nobiletin showed a more significant effect on the physiological function of aged mice. Several skeletal muscle-related functions have been significantly improved, including grip, athletic endurance, and runner running. A further study indicated that improving and optimizing mitochondrial respiratory function in skeletal muscle was the mechanism [63]. Nobiletin also protected cholesterol and bile acid metabolism in high fat diet fed aged mice [64]. However, the beneficial metabolic effects of nobiletin in high fat diet fed mice is independent of AMPK activation [65]. Research in C. elegans supported the anti-aging and lifespan extension effect of nobiletin [66].

In aged mouse models, nobiletin showed markedly beneficial effects as well. In senescence-accelerated SAMP8 mice, nobiletin improves cognitive impairment, and reduces oxidative burden and tau phosphorylation [67]. Nobiletin alleviated cognitive deficits and pathological features in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease [68].

There have been studies searching for small molecules that modulate circadian rhythms. High-throughput screen using reporter cells has identified several synthetic small molecules that enhance clock amplitude [69, 70]. The screening used the heterozygous Clock∆19/+ PER2::Luc reporter cells, which exhibit about one-third rhythm amplitude of wild-type Clock+/+ cells, and the compounds that can restore the reporter rhythm amplitude were selected. High-throughput screen also identified natural compounds that enhance reporter rhythm as well [62]. The most potent one is nobiletin, the natural flavone ingredient in citrus. Tangeretin, a close analog of nobiletin and also a natural plant ingredient, also showed the ability to enhance rhythm amplitude. The finding that nobiletin, an agonist of retinoid acid receptor-related orphan receptors (RORs), can promote circadian metabolism and healthy aging, suggests that more research on dietary compounds with clock-enhancing effect, would provide promising intervention that enhances health during aging.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Diet provides human beings with the energy and nutrition they need to survive, and it also provides humans’ life with joy. Among the many foods, which ones can help human beings enjoy food and also help achieve healthy aging? This is a very interesting question.

Substantial evidence has accumulated that interventions on main components of daily food, including caloric restriction, protein restriction, low protein high carbohydrate diets, and essential amino acid restriction, can increase lifespan in animal models [3]. What other dietary ingredients can help prolong lifespan?

Recently, urolithin A, an end-product from ellagitannins in the pomegranate fruit, has shown promising benefit in promoting healthy muscle function during aging, in a human clinical trial [39]. Quercetin, another ingredient from plant, together with dasatinib to act as senolytics, also helped improving physical function in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), a senescence-associated disease, in a clinical trial [57]. These findings demonstrate the potential powerful role of dietary phytochemicals in health promotion during aging.

Metabolism is an important mechanism in aging regulation, and deterioration in metabolism is closely related with aging. In this review, dietary phytochemicals targeting TRP channels, mitophagy, senescence pathways and circadian rhythms were discussed on longevity extending effect (Table 1). An important question is how we can efficiently find out promising phytochemicals. A screening of 5,300 small molecules based on reporter cells only helped researchers identified two natural ingredients, nobiletin and tangeretin, with circadian rhythm amplitude enhancing effect [62]. Testing on compounds with similar structure might be a good strategy, since tangeretin is a close analog of nobiletin [71] (Fig. 1) in targeting circadian rhythms. It is also supported by the fact that fisetin [48], quercetin [72], curcumin [73], and luteolin [74] are all flavonoids (structures in Fig. 1) and have senolytic activity [49]. Additionally, piperlongumine (structure in Fig. 1) [75], which is a potential senolytic agent, is structurally related to quercetin [76]. Besides the challenge in the initial identification, it takes efforts to clarify the molecular mechanism of action and direct targets of phytochemicals with longevity extending effect. In addition, hormesis, the biphasic dose-response is applicable to the plant-derived compounds mentioned in the article. Future research also needs to explore the different effects of different doses of dietary ingredients [77, 78].

Table 1.

Dietary phytochemicals that extend longevity by regulation of metabolism

| Target | Dietary plant ingredient | Mechanism of action |

|---|---|---|

| TRP channels | Capsaicin, AITC (allyl isothiocyanate) | TRPV1 agonist and regulation of neuropeptide calcitonin-gene-related peptide (CGRP) production; TRPA1 agonist and signals to DAF-16/FOXO |

| Mitophagy | Urolithin A, deubiquitylating enzymes inhibitors, resveratrol | Activation or inhibition of mitophagy and improvement of muscle function |

| Senescence pathways | Fisetin, quercetin, piperlongumine, curcumin, and luteolin | Targeting BCL-2 and related anti-apoptotic pathways |

| Circadian rhythms | Nobiletin, tangeretin | Targeting retinoid acid receptor-related orphan receptors (RORs) and enhancing circadian rhythm amplitude |

During the COVID-19 outbreak, herbal recipes have proved to be helpful to reduce the symptoms in China. There are also evidences that functional food components acting as a nutritional supplement, can help human beings prevent from infection of COVID-19 or enhance the recovery, by boosting the immune function [79]. Thus, the phytochemicals from nature could be a great treasure for human beings for curing diseases and also preventing aging. For example, the black chokeberry extract has a high content of quercetin, which has health-protective activities such as prolonging life span, anti-proliferation, improving glucose and lipid metabolism, preventing neurodegenerative diseases [80]. The urolithin A, fisetin and other substances discussed in the article are also present in daily edible fruits, such as pomegranates, berries, apples, and grapes. Further research unravelling the detailed effects and mechanisms of dietary ingredients on longevity regulation, would be helpful for humans to develop more interventions to achieve healthy aging, and meanwhile, to allow individually customed dietary approach that balance between health and personal preferences.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 303 kb)

Funding

This work was supported by the grant to J.S. (National Natural Science Foundation of China, 31500970).

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fontana L. The science of nutritional modulation of aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;39:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Most J, et al. Calorie restriction in humans: an update. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;39:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simpson SJ, et al. Dietary protein, aging and nutritional geometry. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;39:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2017.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manoogian ENC, Panda S. Circadian rhythms, time-restricted feeding, and healthy aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;39:59–67. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown-Borg HM, Buffenstein R. Cutting back on the essentials: can manipulating intake of specific amino acids modulate health and lifespan? Ageing Res Rev. 2017;39:87–95. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattson MP, Longo VD, Harvie M. Impact of intermittent fasting on health and disease processes. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;39:46–58. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ingram DK, de Cabo R. Calorie restriction in rodents: caveats to consider. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;39:15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2017.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Balasubramanian P, Mattison JA, Anderson RM. Nutrition, metabolism, and targeting aging in nonhuman primates. Ageing Res Rev. 2017;39:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoddy KK, et al. Intermittent fasting and metabolic health: from religious fast to time-restricted feeding. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2020;28(Suppl 1):S29–s37. doi: 10.1002/oby.22829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwangbo DS, et al. Mechanisms of lifespan regulation by calorie restriction and intermittent fasting in model organisms. Nutrients. 2020;12:1194. doi: 10.3390/nu12041194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waldman HS, Renteria LI, McAllister MJ. Time-restricted feeding for the prevention of cardiometabolic diseases in high-stress occupations: a mechanistic review. Nutr Rev. 2020;78:459–464. doi: 10.1093/nutrit/nuz090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu S, et al. Intermittent fasting as a nutrition approach against obesity and metabolic disease. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2020;23:387–394. doi: 10.1097/mco.0000000000000694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martel J, et al. Hormetic effects of phytochemicals on health and longevity. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2019;30:335–346. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu Q et al (2021) Procyanidin C1 is a natural agent with senolytic activity against aging and age-related diseases. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2021.04.14.439765

- 15.Fourati M, et al. Bioactive compounds and pharmacological potential of pomegranate (Punica granatum) seeds - a review. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2020;75:477–486. doi: 10.1007/s11130-020-00863-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia-Diaz DF, et al. A review of the potential of Chilean native berries in the treatment of obesity and its related features. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2019;74:277–286. doi: 10.1007/s11130-019-00746-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen X et al (2020) Transient receptor potential canonical (TRPC) channels: then and now. Cells 9. 10.3390/cells9091983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Riera CE, et al. TRPV1 pain receptors regulate longevity and metabolism by neuropeptide signaling. Cell. 2014;157:1023–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xiao R, et al. A genetic program promotes C. elegans longevity at cold temperatures via a thermosensitive TRP channel. Cell. 2013;152:806–817. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yasueda A, Ito T, Maeda K. Review: evidence-based clinical research of anti-obesity supplements in Japan. Immunol Endocr Metab Agents Med Chem. 2013;13:185–195. doi: 10.2174/1871522213666131118221347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bonaccio M, et al. Chili pepper consumption and mortality in Italian adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:3139–3149. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.09.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv J, et al. Consumption of spicy foods and total and cause specific mortality: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2015;351:h3942. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h3942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chopan M, Littenberg B (2017) The association of hot red chili pepper consumption and mortality: a large population-based cohort study. PLoS One 12:e0169876. 10.1371/journal.pone.0169876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Shen J, et al. Sex specific effects of capsaicin on longevity regulation. Exp Gerontol. 2020;130:110788. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2019.110788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bode AM, Dong Z. The two faces of capsaicin. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2809–2814. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-10-3756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surh YJ, Lee SS. Capsaicin, a double-edged sword: toxicity, metabolism, and chemopreventive potential. Life Sci. 1995;56:1845–1855. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(95)00159-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hernández-Pérez T, et al. Capsicum annuum (hot pepper): an ancient Latin-American crop with outstanding bioactive compounds and nutraceutical potential. A review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2020;19:2972–2993. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fokkens W, Hellings P, Segboer C. Capsaicin for rhinitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016;16:60. doi: 10.1007/s11882-016-0638-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Smeets A, Lejeune MP. Sensory and gastrointestinal satiety effects of capsaicin on food intake. Int J Obes. 2005;29:682–688. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Acharya N, et al. Endocannabinoid system acts as a regulator of immune homeostasis in the gut. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:5005–5010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1612177114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang B, et al. Environmental temperature differentially modulates C. elegans longevity through a thermosensitive TRP Channel. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1414–1424. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Watanabe T, Terada Y. Food compounds activating thermosensitive TRP channels in Asian herbal and medicinal foods. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2015;61(Suppl):S86–S88. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.61.S86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mukaiyama M, Usui T, Nagumo Y. Non-electrophilic TRPA1 agonists, menthol, carvacrol and clotrimazole, open epithelial tight junctions via TRPA1 activation. J Biochem. 2020;168:407–415. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvaa057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bratic A, Larsson NG. The role of mitochondria in aging. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:951–957. doi: 10.1172/JCI64125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Youle RJ, Narendra DP. Mechanisms of mitophagy. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:9–14. doi: 10.1038/nrm3028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johanningsmeier SD, Harris GK. Pomegranate as a functional food and nutraceutical source. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2011;2:181–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-030810-153709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Espin JC, et al. Biological significance of urolithins, the gut microbial ellagic acid-derived metabolites: the evidence so far. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:270418. doi: 10.1155/2013/270418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryu D, et al. Urolithin a induces mitophagy and prolongs lifespan in C. elegans and increases muscle function in rodents. Nat Med. 2016;22:879–888. doi: 10.1038/nm.4132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andreux PA, et al. The mitophagy activator urolithin a is safe and induces a molecular signature of improved mitochondrial and cellular health in humans. Nature Metabolism. 2019;1:595–603. doi: 10.1038/s42255-019-0073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Singh R, et al. Enhancement of the gut barrier integrity by a microbial metabolite through the Nrf2 pathway. Nat Commun. 2019;10:89. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07859-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xia B, et al. Urolithin a exerts antiobesity effects through enhancing adipose tissue thermogenesis in mice. PLoS Biol. 2020;18:e3000688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harrigan JA, et al. Deubiquitylating enzymes and drug discovery: emerging opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2018;17:57–78. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang H, et al. Resveratrol attenuates oxidative damage through activating mitophagy in an in vitro model of Alzheimer's disease. Toxicol Lett. 2018;282:100–108. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2017.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang D, et al. Resveratrol improves muscle atrophy by modulating mitochondrial quality control in STZ-induced diabetic mice. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2018;62:e1700941. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201700941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhu Y, et al. Cellular senescence and the senescent secretory phenotype in age-related chronic diseases. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2014;17:324–328. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu M et al (2015) JAK inhibition alleviates the cellular senescence-associated secretory phenotype and frailty in old age. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:E6301–E6310. 10.1073/pnas.1515386112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Xu M, et al. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat Med. 2018;24:1246–1256. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0092-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kim JH, et al. Fisetin suppresses macrophage-mediated inflammatory responses by blockade of Src and Syk. Biomol Ther (Seoul) 2015;23:414–420. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2015.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yousefzadeh MJ, et al. Fisetin is a senotherapeutic that extends health and lifespan. EBioMedicine. 2018;36:18–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Currais A, et al. Modulation of p25 and inflammatory pathways by fisetin maintains cognitive function in Alzheimer's disease transgenic mice. Aging Cell. 2014;13:379–390. doi: 10.1111/acel.12185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Currais A, et al. Fisetin reduces the impact of aging on behavior and physiology in the rapidly aging SAMP8 mouse. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73:299–307. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shi YS, et al. Fisetin attenuates metabolic dysfunction in mice challenged with a high-fructose diet. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:8291–8298. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b02140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ge C, et al. Fisetin supplementation prevents high fat diet-induced diabetic nephropathy by repressing insulin resistance and RIP3-regulated inflammation. Food Funct. 2019;10:2970–2985. doi: 10.1039/c8fo01653d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Althunibat OY, et al. Fisetin ameliorates oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis in diabetic cardiomyopathy. Life Sci. 2019;221:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2019.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhu Y, et al. New agents that target senescent cells: the flavone, fisetin, and the BCL-XL inhibitors, A1331852 and A1155463. Aging (Albany NY) 2017;9:955–963. doi: 10.18632/aging.101202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang P, et al. Senolytic therapy alleviates Aß-associated oligodendrocyte progenitor cell senescence and cognitive deficits in an Alzheimer's disease model. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:719–728. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0372-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Justice JN et al (2019) Senolytics in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: results from a first-in-human, open-label, pilot study. EBioMedicine. 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.12.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Wang Y, et al. Discovery of piperlongumine as a potential novel lead for the development of senolytic agents. Aging (Albany NY) 2016;8:2915–2926. doi: 10.18632/aging.101100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fang Y et al (2021) Sexual dimorphic responses of C57BL/6 mice to fisetin or dasatinib and quercetin cocktail oral treatment. bioRxiv. 10.1101/2021.11.08.467509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Marcheva B, et al. Disruption of the CLOCK components CLOCK and BMAL1 leads to hypoinsulinaemia and diabetes. Nature. 2010;466:627–631. doi: 10.1038/nature09253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vitaterna MH, et al. The mouse clock mutation reduces circadian pacemaker amplitude and enhances efficacy of resetting stimuli and phase-response curve amplitude. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9327–9332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603601103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.He B, et al. The small molecule nobiletin targets the molecular oscillator to enhance circadian rhythms and protect against metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab. 2016;23:610–621. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nohara K, et al. Nobiletin fortifies mitochondrial respiration in skeletal muscle to promote healthy aging against metabolic challenge. Nat Commun. 2019;10:3923. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11926-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nohara K et al (2019) Coordinate regulation of cholesterol and bile acid metabolism by the clock modifier nobiletin in metabolically challenged old mice. Int J Mol Sci 20:4281. 10.3390/ijms20174281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Morrow NM et al (2020) The citrus flavonoid nobiletin confers protection from metabolic dysregulation in high-fat fed- mice independent of AMPK. J Lipid Res 61:387–402. 10.1194/jlr.RA119000542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Yang X et al (2020) Nobiletin delays aging and enhances stress resistance of Caenorhabditis elegans. Int J Mol Sci 21:341. 10.3390/ijms21010341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Nakajima A, et al. Nobiletin, a citrus flavonoid, ameliorates cognitive impairment, oxidative burden, and hyperphosphorylation of tau in senescence-accelerated mouse. Behav Brain Res. 2013;250:351–360. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakajima A, Ohizumi Y (2019) Potential benefits of nobiletin, a citrus flavonoid, against Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Int J Mol Sci 20:3380. 10.3390/ijms20143380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Doruk YU, et al. A CLOCK-binding small molecule disrupts the interaction between CLOCK and BMAL1 and enhances circadian rhythm amplitude. J Biol Chem. 2020;295:3518–3531. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA119.011332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Chen Z, et al. Identification of diverse modulators of central and peripheral circadian clocks by high-throughput chemical screening. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:101–106. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1118034108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nichols LA, et al. Citrus flavonoids repress the mRNA for stearoyl-CoA desaturase, a key enzyme in lipid synthesis and obesity control, in rat primary hepatocytes. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:36. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-10-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.dos Santos AE et al (2014) Quercetin and quercetin 3-O-glycosides from Bauhinia longifolia (bong.) Steud. Show anti-Mayaro virus activity. Parasit Vectors 7:130. 10.1186/1756-3305-7-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Zunino SJ, et al. Oral or parenteral administration of curcumin does not prevent the growth of high-risk t(4;11) acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells engrafted into a NOD/SCID mouse model. Int J Oncol. 2013;42:741–748. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2012.1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pratheeshkumar P, et al. Luteolin inhibits human prostate tumor growth by suppressing vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2-mediated angiogenesis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aodah A et al (2016) Preformulation studies on piperlongumine. PLoS One 11:e0151707. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 76.Kirkland JL, Tchkonia T. Cellular Senescence: A Translational Perspective EBioMedicine. 2017;21:21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Martel J, et al. Phytochemicals as prebiotics and biological stress inducers. Trends Biochem Sci. 2020;45:462–471. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2020.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Calabrese EJ. Hormesis mediates acquired resilience: using plant-derived chemicals to enhance health. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2021;12:355–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev-food-062420-124437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Singh P, et al. Potential inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 and functional food components as nutritional supplement for COVID-19: a review. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2020;75:458–466. doi: 10.1007/s11130-020-00861-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Platonova EY, et al. Black chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) extracts in terms of geroprotector criteria. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2021;114:570–584. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.06.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 303 kb)