Abstract

Purpose: To perform a comprehensive and systematic critical appraisal of the genetic alterations reported to be present in adenomatoid odontogenic tumor (AOT) compared to ameloblastoma (AM), to aid in the understanding in their development and different behavior.

Methods: An electronic search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science during March 2021. Eligibility criteria included publications on humans which included genetic analysis of AOT or AM.

Results: A total of 43 articles reporting 59 AOTs and 680 AMs were included. Different genomic techniques were used, including whole-exome sequencing, direct sequencing, targeted next-generation sequencing panels and TaqMan allele-specific qPCR. Somatic mutations affecting KRAS were identified in 75.9% of all AOTs, mainly G12V; whereas a 71% of the AMs harbored BRAF mutations, mainly V600E.

Conclusions: The available genetic data reports that AOTs and AM harbor somatic mutations in well-known oncogenes, being KRAS G12V/R and BRAFV600E mutations the most common, respectively. The relatively high frequency of ameloblastoma compared to other odontogenic tumors, such as AOT, has facilitated the performance of different sequencing techniques, allowing the discovery of different mutational signatures. On the contrary, the low frequency of AOTs is an important limitation for this. The number of studies that have a assessed the genetic landscape of AOT is still very limited, not providing enough evidence to draw a conclusion regarding the relationship between the genomic alterations and its clinical behavior. Thus, the presence of other mutational signatures with clinical impact, co-occurring with background KRAS mutations or in wild-type KRAS cases, cannot be ruled out. Since BRAF and RAS are in the same MAPK pathway, it is interesting that ameloblastomas, frequently associated with BRAFV600E mutation have aggressive clinical behavior, but in contrast, AOTs, frequently associated with RAS mutations have indolent behavior. Functional studies might be required to solve this question.

Keywords: odontogenic tumors, adenomatoid odontogenic tumor, amelobalstoma, genetic mutation, BRAF, KRAS

Introduction

Adenomatoid Odontogenic Tumor (AOT) and Ameloblastoma (AM) are benign epithelial odontogenic tumors affecting most commonly the tooth bearing areas of the jaws. Both tumors are composed of a proliferation of epithelial cells arranged in a way that reminds to some extent, to the enamel organ of a tooth germ [1]. AM is well-known for being locally infiltrating, for its continuous growth, its high rates of recurrences if not adequately removed and the possibility of undergoing malignant transformation [2]. On the contrary, AOT manifests clinically as a slow and self-limiting growth which does not require the aggressive surgical approach usually adopted for AM. In AOT, recurrences are extremely rare, even if it is partially removed [3]. The clinicopathological features of both tumors, allows to consider AM as a neoplasm, whereas there is a general agreement that AOT may represent a hamartoma [3–5], although this is a matter of debate.

Different genomic alterations, which includes chromosomal imbalances and genetic mutations, have been reported to be present in ameloblastomas. Mutations in genes that belong to the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway are present in almost 90% of ameloblastomas, with BRAF V600E, being the most described mutation [6–10]. The prevalence of BRAF V600E in ameloblastoma ranges from 46 [6] to 90% [11], with a mean value of 68%. Other somatic mutations have been reported, either in MAPK or non-MAPK pathways [6, 8, 10, 12–16]. Some of these, such as mutations in PTEN, SMARCB1, EGFR, TP53, CTNNB1, and PIK3CA [6, 8–10], can occur in the background of the classical BRAF V600E mutation. Nevertheless, mutations in SMO, FGFR2, KRAS, HRAS, and NRAS have been reported to be mutually exclusive with BRAF V600E [8, 14]. Moreover, deletions in chromosome 22 [6, 17–19] and copy number alterations in BAG1, PPP2R5A, and PKD1L2 [20] have also been reported and could also be involved in the pathogenesis of the tumor.

Little information is known about the genetic background of AOT. Mutations in the β-catenin gene (CTNNB1) have been suggested, as strong cytoplasmatic expression of β-catenin is reported using immunohistochemistry [4, 21]. However, authors have failed to show alterations in CTNNB1 [4]. Nevertheless, other more recent studies have shown consistent mutations in KRAS [22–24] and copy number alterations [23] affecting IGF2BP3.

As both AM and AOT have different clinical behavior, suggesting a different biological nature, and there has been a significant interest in papers reporting their genetic alterations during the last years, the aim of this systematic review was to compare the genetic alterations of AOT with the ones reported in AM, in order to summarize the current genetic knowledge of these lesions and aid in the understanding of the genomic alterations underlying their development.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted following the PRISMA Statement guidelines.

Eligibility Criteria

Parameters were kept broad to maximize search results. The inclusion criteria consisted of full text observational research studies on humans about genetic analysis of adenomatoid odontogenic tumor or ameloblastoma, with or without clinicopathological and treatment information. Studies were excluded if they were about polymorphisms, were performed in-vitro or were not performed on human participants. Conference abstracts, articles where the full text was unavailable, bioinformatic research only, reviews, case reports, or case series without genetic analysis were also excluded.

Information Sources and Search Strategy

A preliminary literature search was conducted by one of the authors (RMF) to guide the search strategy. The search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science during March of 2021, restricted to human studies in English language and without year restrictions. The following keywords were used in the identification of potential articles: (adenomatoid odontogenic tumor OR ameloblastoma) AND (chromosomal alteration OR copy number variation OR deletion OR gene mutation OR genetic OR genomic OR genome OR insertion OR loss of heterozygosity OR microarray OR sanger sequencing OR single nucleotide variant OR targeted next-generation sequencing OR whole exome sequencing). This was further complemented with manual searches using the reference list of each identified study.

Selection Process

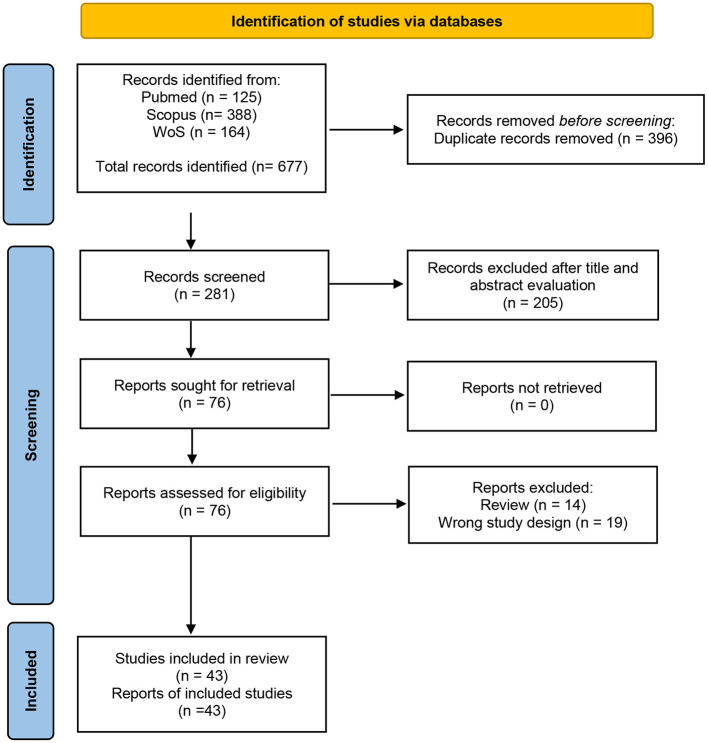

After the removal of duplicates, two independent researchers (SN and CM) read the title and abstract to identify and select articles. Full text of selected studies were then analyzed and those who met the eligibility criteria were included in the review (Figure 1). Any disagreement was resolved through discussion guided by a third researcher who acted as a referee (RMF). No automation tools were used in this process

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Data Collection Process

After reading the full text, two independent researchers (SN and CM) extracted and transferred the data to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Office 365®). Any disagreement was resolved through discussion guided by a third researcher who acted as a referee (RMF). No automation tools were used in this process.

Study Risk of Bias Assessment

The entities included in this review are rare and as such, the highest quality of primary data is from case series. At present, there is no agreed guidelines to perform and report molecular biology studies about odontogenic tumors. Hence, there is substantial heterogeneity in their data recording and reporting. Given these limitations, the risk of bias will be uncertain on almost all reported case series, with low quality of evidence. Therefore, we have decided not to undertake these assessments.

Synthesis Methods

A narrative synthesis of the data is planned. The characteristics collected from the studies to do the quantitative analysis will be based on: first author, year, country, tissue sample, sample size, gene or chromosome involved, gene mutation, signaling pathway, and genetic assay. Visualization of the data will be presented in form of figures and tables.

Results

The search results are outlined in a PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1. The initial literature search identified 677 studies. Following duplicate removal (n = 396), 281 studies had their titles and abstracts screened by two of the reviewers (SN and CM) from which 205 articles were removed. Finally, 76 studies were included for full text evaluation to ensure they satisfied the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Thirty-four articles were excluded with the following reasons: reviews (n = 14) and wrong study design (n = 19). In total, 43 articles were included in this systematic review (Figure 1).

Adenomatoid Odontogenic Tumor

Gene Mutations

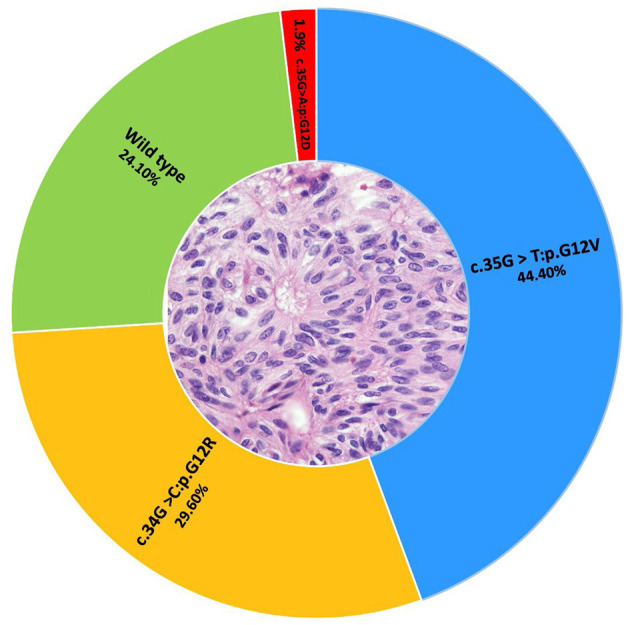

Six articles reported mutations in AOT [4, 22–26]. A total of 59 AOTs were assessed under different genomic techniques, such as direct sequencing, targeted NGS panels, and TaqMan allele-specific qPCR (Table 1). KRAS was the most commonly affected gene among the studies that included this gene in their analysis. One article used TaqMan allele-specific qPCR for KRAS [22], whereas other two worked with a Targeted NGS panel which included RAS family [23, 24] (Table 1). A total of 54 samples were analyzed among these 3 studies, from which 75.9% harbored somatic mutations in KRAS (n = 41). All the studies reported that the mutations affecting KRAS corresponded to single nucleotide variations corresponding to missense mutations [22–24]. All the mutations affected codon 12, in which three types of transversions were identified: guanine to thymidine (G>T) in 24/41 cases, guanine to cytosine (G>C) in 16/41 cases and guanine to an adenosine (G>A) in one case. The aforementioned single base variations lead to G12V, G12R, or G12D substitutions, respectively [22–24] (Figures 2, 3).

Table 1.

Gene mutations reported in AOT.

| References | Year | Country | Tissue sample | Sample size | Gene involved (n) | Gene mutation | Signaling pathway | Genetic technique assay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shimura et al. [25] | 2020 | Japan | FFPE, FT | 1 | SMO (1) | Y399S and Y394S | Hedgehog | Targeted NGS panel |

| Coura et al. [22] | 2019 | Brazil | FFPE | 38 | KRAS (27) | G12V (n = 15) | MAPK/ERK | TaqMan allele-specific qPCR, histological and morphometric analysis, immunohistochemistry and Sanger sequencing |

| G12R (n = 12) | ||||||||

| Wild type (n = 11) | ||||||||

| Bologna-Molina et al. [24] | 2018 | Japan | FFPE | 9 | KRAS (7) | G12D (n = 1) | MAPK/ERK | Targeted NGS, Luminex assay, and immunohistochemistry |

| c.35G>T: p: G12V (n = 2) | ||||||||

| G12R (n = 4) | ||||||||

| Not suitable for analysis (n = 2) | ||||||||

| Gomes et al. [23] | 2016 | Brazil | N/A | 9 | KRAS (7) | G12 | MAPK/ERK | Targeted NGS, Sanger sequencing, and qPCR |

| Wild type (n = 2) | ||||||||

| Harnet et al. [4] | 2013 | France | FFPE | 1 | CTNNB1 | No mutation | Wnt/β-catenin | Direct sequencing, immunohistochemistry |

| Perdigão et al. [26] | 2004 | Brazil | FFPE, FT | 1 | AMBN (1) | R90W | N/A | Direct sequencing |

N/A, Not Available.

Figure 2.

A total of 54 AOTs were assessed for KRAS mutations. The KRAS G12V mutation was identified in 24 cases, G12R in 16 cases and G12D in one tumor. The remaining 13 cases corresponded to wild type cases.

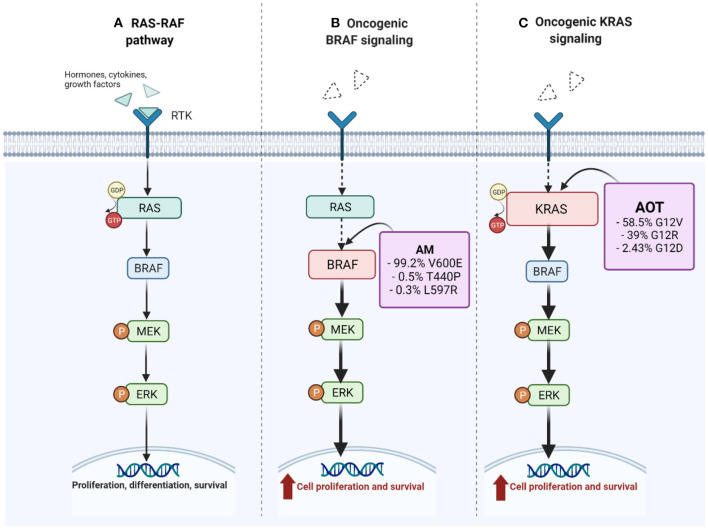

Figure 3.

Constitutive and oncogenic activation of MAPK/ERK pathway. In (A), several growth factors, hormones, and cytokines activate the receptor tyrosine-kinase (RTK) favoring the constitutive activation of RAS by switching GDP-GTP toward the activate state. The downstream signaling is regulated by RAS-GTP and additional proteins that are not shown in this figure. Ras activates BRAF which facilitates the phosphorylation of MEK, which in turn allows the phosphorylation and activation of ERK. The resulting signaling cascade culminates with translocation of ERK to the nucleus, and the activation of transcription factors that result in the expression of genes related to proliferation, differentiation, and survival. In (B,C), in the presence of oncogenic BRAF and KRAS, respectively, the constitutive activation is independent of extracellular factors and does not respond to biochemical signals that would normally regulate the activity. Adapted from “Vemurafenib in Oncogenic BRAF Signaling Pathway in Melanoma,” by BioRender.com (2021). Retrieved from: https://app.Biorender.com/biorender-templates.

Among the remaining three studies, one article worked with a Targeted NGS panel assessing specifically mutations in SMO, BRAF, PTCH1, and GNAS [25]. Only one AOT was included and showed two missense mutations in SMO (Y394S and p.Y399S). No mutations affecting BRAF or PTCH1 were reported [25].

By direct sequencing, one study identified one heterozygous missense mutation affecting AMBN, leading to a R90W substitution [26]. Using pyrosequencing and direct sequencing, Harnet et al., did not detect mutations affecting CTNNB1 [4] in a follicular type of AOT (Table 1).

Chromosomal Alterations

To date there is only one published article about chromosomal alterations in AOT [23]. By using a whole-genome array and comparing those results with databases, Gomes et al. reported two rare losses in AOTs. One deletion affecting IGF2BP3 at 7p15.3 in a single AOT, and another affecting the chromosome 6 at q15, but no gene was identified at that position. The deletion in IGF2BP3 involved an intronic region of the protein-coding transcript, however, in silico analysis predicted the implication of the first exon of four alternative transcripts. Its potential in tumorigenesis remains unclear [23] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Chromosomal alterations in AOT and AM.

| References | Year | Country | Tumor | Tissue sample | Sample size | Genetic technique assay | Chromosome | Alteration | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diniz et al. [20] | 2017 | Brazil | AM, AC | FT | 8, 1 | Whole genome microarray, qPCR, and RT-qPCR | 9p21.1 | CNA Gain | B4GALT1 and BAG1 |

| 16q23.2 | CNA Loss | PKD1L2 | |||||||

| 1q32.3 | CNA Gain | PPP2R5A | |||||||

| Gomes et al. [23] | 2016 | Brazil | AOT | N/A | 2 | Whole genome microarray, targeted NGS, Sanger sequencing, and qPCR | 7p15.3 | CNA Loss | IGF2BP3 |

| Toida et al. [19] | 2005 | Japan | AM | FT | 9 | Comparative genomic hybridization and FISH | 1q | CNA Gain | N/A |

| 1pter, 10q, and 22q | CNA Loss | Potential candidate genes RIZ1 (1p36.3–p36.2), NBL1 (1p36.13–p36.11), TP73 (1p36.3), and CDC2L2 (1p36.3) | |||||||

| Nodit et al. [27] | 2004 | United States | AM, AC | FFPE | 12, 3 | Panel of microsatellite markers | 1p34.2 and 10q23 | Allelic loss | L- myc and PTEN |

| Jääskeläinen et al. [18] | 2002 | Finland | AM | FFPE | 20 | Comparative genomic hybridization and immunocytochemistry | 21; 16q, 19p, and of 22 | CNA Loss | N/A |

| 16p | CNA Gain | N/A | |||||||

| Guan et al. [13] | 2019 | Singapore | AM | FT | 10 | Whole-exome sequencing | None | None | N/A |

N/A, Not Available.

Ameloblastoma

Gene Mutations

Our search yielded 37 articles about the molecular landscape of ameloblastoma. A total of 680 tumors were assessed using small-to large-scale and “omics” techniques. Two studies performed whole-exome sequencing (WES) [13, 15], eight used targeted NGS panels [6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 20, 25], and the remaining 26 performed either TaqMan-allele specific probes or direct sequencing (Table 3).

Table 3.

Gene mutations reported in ameloblastoma.

| References | Year | Country | Tissue sample | Number of AM | Gene involved (n) | Gene mutation | Signaling pathway | Genetic technique assay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shi et al. [15] | 2021 | China | FT | 4 | BRAF (4) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Whole exome sequencing |

| HSPA4 (2) | E700G and H205N | N/A | ||||||

| KMT2D (1) | Frameshift deletion | N/A | ||||||

| Shimura et al. [25] | 2020 | Japan | FFPE, FT | 6 | BRAF (2) | T440P | MAPK/ERK | Targeted NGS panel |

| PTCH1 (1) | V582G | Hedgehog | ||||||

| Derakhshan et al. [28] | 2020 | Iran | FFPE | 50 | BRAF (46) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | qRT-PCR, immunohistochemistry |

| Oh et al. [11] | 2020 | Korea | FFPE | 28 | BRAF (24) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Sanger sequencing and immunohistochemistry |

| Sant'Ana et al. [29] | 2020 | Brazil | FFPE | 5 | BRAF (4) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Taqman allele-specific qPCR, Sanger sequencing |

| Seki-Soda et al. [30] | 2020 | Japan | FFPE | 21 | BRAF (16) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Sanger sequencing and immunohistochemistry |

| Zhang et al. [31] | 2020 | China | FFPE, FT | 17 | BRAF (14) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Direct sequencing |

| Duarte-Andrade et al. [32] | 2019 | Brazil | FFPE | 12 | BRAF (9) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Metabolic profiling by GC-MS and TaqMan allele-specific qPCR |

| Guan et al. [13] | 2019 | Singapore | FT | 10 | BRAF (8) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Whole exome sequencing |

| ANKRD31 (2) | P1580Q and D796Y | N/A | ||||||

| CDC73 (2) | L404I and P351T | N/A | ||||||

| CREBBP (2) | Frameshift deletion | N/A | ||||||

| DHX29 (2) | (G1121T and W374L); (L610F) | N/A | ||||||

| KMT2D (2) | Stop gain | N/A | ||||||

| PLEKHN1 (2) | Frameshift deletion | N/A | ||||||

| BCOR (1) | Frameshift deletion | N/A | ||||||

| CTNNB1 (1) | G34V and G27V | N/A | ||||||

| LRP6 (1) | P455S | N/A | ||||||

| LAMB1 (1) | Frameshift deletion | N/A | ||||||

| SCN5A (1) | F1908L; F1872L; F1925L; F1926L; F1893L | N/A | ||||||

| Oh et al. [33] | 2019 | Korea | FFPE | 30 | BRAF (27) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Sanger sequencing and immunohistochemistry |

| Narayan et al. [34] | 2019 | India | FFPE | 20 | PTEN (5) | V158E | PI3K/Akt/mTOR | Sanger sequencing |

| PTEN (5) | PI3K/Akt/mTOR | |||||||

| PTEN (5) | Stop gain | PI3K/Akt/mTOR | ||||||

| Xia et al. [35] | 2019 | China | FFPE | 5 | BRAF (3) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | TaqMan allele-specific qPCR, FISH, Alcian blue staining |

| Bartels et al. [12] | 2018 | Germany | FFPE | 20 | BRAF (5) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Targeted NGS panel, FISH, immunohistochemistry, and pyrosequencing |

| 7 | FGFR2 (4) | C383R (2) | FGF/FGFR | |||||

| FGFR2 (4) | Y376C | FGF/FGFR | ||||||

| FGFR2 (4) | V396D | FGF/FGFR | ||||||

| TP53 (1) | R248Q | p53 | ||||||

| PTEN (1) | Q171K | PI3K/Akt/mTOR | ||||||

| KRAS (1) | L56_G60dup | MAPK/ERK | ||||||

| Gültekin et al. [10] | 2018 | France | FFPE | 62 | SMO (8) | L412F (6) | Hedgehog | Sanger sequencing |

| SMO (8) | W535L (2) | Hedgehog | ||||||

| BRAF (34) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Targeted NGS panel | |||||

| NRAS (2) | N/A | MAPK/ERK | ||||||

| Germany | HRAS (1) | N/A | MAPK/ERK | |||||

| EGFR (1) | N/A | EGFR | ||||||

| KRAS (2) | N/A | MAPK/ERK | ||||||

| PIK3CA (4) | N/A | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | ||||||

| Turkey | PTEN (2) | N/A | PI3K/Akt/mTOR | |||||

| FGFR (1) | N/A | FGF/FGFR | ||||||

| CDKN2A (2) | N/A | NS | ||||||

| CTNNB1 (1) | N/A | Wnt/β-catenin | ||||||

| Heikinheimo et al. [14] | 2018 | Finland | FFPE, FT | 73 | BRAF (58) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Targeted NGS panel, Sanger sequencing RT-qPCR and immunohistochemistry |

| SMO (1) | L412F | Hedgehog | ||||||

| FGFR2 (2) | C382R | FGF/FGFR | ||||||

| HRAS (2) | Q61R | MAPK/ERK | ||||||

| NRAS (2) | Q61R | MAPK/ERK | ||||||

| Soltani et al. [36] | 2018 | Iran | FFPE | 19 | BRAF (12) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Direct sequencing |

| Diniz et al. [20] | 2017 | Brazil | FT | 8 | BRAF (7) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Whole genome microarray, qPCR, and RT-qPCR |

| Yukimuri et al. [16] | 2017 | Japan | FFPE | 14 | CTNNB1 (2) | S37C and G34E | Wnt/β-catenin | Targeted NGS panel, Sanger sequencing, immunohistochemistry, immunocytochemistry, western blotting, cell culture. |

| NRAS (2) | Q61R | MAPK/ERK | ||||||

| BRAF (12) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | ||||||

| Li et al. [37] | 2016 | China | FT | 30 | APC (ND) | N/A | Wnt/β-catenin | Direct sequencing, Methylation detection of APC gene |

| Pereira et al. [38] | 2016 | Brazil | FFPE | 8 | BRAF (5) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | TaqMan allele-specific qPCR, Sanger sequencing and immunohistochemistry |

| Brunner et al. [39] | 2015 | Switzerland | FFPE | 19 | BRAF (14) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Multiplex and nested PCR, Sanger sequencing, and FISH |

| Diniz et al. [9] | 2015 | Brazil | FFPE | 17 | BRAF (14) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | qPCR and Sanger sequencing |

| Brown et al. [8] | 2014 | United States | FFPE | 50 | BRAF (31) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Allele-specific PCR, targeted NGS panel, Sanger sequencing, immunohistochemistry, western blotting, cell culture, and proliferation assays |

| KRAS (4) | G12R | MAPK/ERK | ||||||

| NRAS (3) | Q61R (2) and Q61K (1) | MAPK/ERK | ||||||

| HRAS (3) | G12S, Q61R, Q61K | MAPK/ERK | ||||||

| FGFR2 (3) | C382R (2) and V395D | FGF/FGFR | ||||||

| SMO (8) | L412F (4) | Hedgehog | ||||||

| SMO (8) | W535L (3) | Hedgehog | ||||||

| SMO (8) | G416E (1) | Hedgehog | ||||||

| CTNNB1 (2) | S33P and S45P | Wnt/β-catenin | ||||||

| PIK3CA (3) | E542K, E545K, H1047R | PI3K/AKT/mTOR | ||||||

| SMARCB1 (3) | R77H | NS | ||||||

| Kurppa et al. [7] | 2014 | Finland | FT | 24 | BRAF (15) | V600E | MAPK/ERK | Sanger sequencing, RT-qPCR, immunohistochemistry, western blotting, cell culture, and MTT cell viability assay |

| Li et al. [40] | 2014 | China | FFPE | 20 | TSC1 (10) | D24E; A84T; E445E; Q792R; C803S; L861L; Q990Q | mTOR | RT-PCR, direct sequencing, immunohistochemistry |

| Sweeney et al. [6] | 2014 | United States | FFPE | 28 | BRAF (13) | V600E (12) and L597R (1) | MAPK/ERK | Targeted NGS panel and RNA sequencing, Sanger sequencing, immunohistochemistry, western blotting, SMO functional assays, and BRAF inhibitor studies |

| SMO (11) | L412F (10) | Hedgehog | ||||||

| SMO (11) | W535L | Hedgehog | ||||||

| KRAS (4) | G12R | MAPK/ERK | ||||||

| FGFR2 (5) | C382R (4) and N549K | FGF/FGFR | ||||||

| Oikawa et al. [41] | 2013 | Japan | FFPE, FT | 18 | EGFR (0) | No mutation | EGFR | Chromogenic in situ hybridization (CISH), Direct DNA sequencing, immunohistochemistry |

| Siriwardena et al. [42] | 2009 | Japan | FFPE | 6 | CTNNB1 (0) | No mutation | Wnt/β-catenin | Direct sequencing, immunohistochemistry |

| APC (3) | G1339A | Wnt/β-catenin | ||||||

| Tanahashi et al. [43] | 2008 | Japan | FFPE | 18 | AXIN1 (1) | Silent mutation | Wnt/β-catenin | Direct sequencing, immunohistochemistry |

| AXIN2 (1) | SNP | Wnt/β-catenin | ||||||

| Miyake et al. [44] | 2006 | Japan | FFPE | 6 | CTNNB1 (1) | T40I | Wnt/β-catenin | Direct sequencing, immunohistochemistry |

| Kawabata et al. [45] | 2005 | Japan | 14 | CTNNB1 (1) | N/A | Wnt/β-catenin | Direct sequencing | |

| Kumamoto et al. [46] | 2004 | Japan | FFPE, FT | 22 | KRAS (1) | G12A | MAPK/ERK | Direct sequencing, immunohistochemistry |

| Kumamoto et al. [47] | 2004 | Japan | FFPE, FT | 10 | TP53 (0) | No mutation | p53 | Direct sequencing, immunohistochemistry |

| Perdigão et al. [26] | 2004 | Brazil | FFPE, FT | 4 | AMBN (5) | One splice site mutation | N/A | Direct sequencing |

| AMBN (5) | P81Q; T604A; M76R; Q54E | N/A | ||||||

| Sekine et al. [48] | 2003 | Japan | FFPE | 20 | CTNNB1 (1) | S45P | Wnt/β-catenin | Direct sequencing and immunohistochemistry |

| Shibata et al. [49] | 2002 | Japan | FT | 12 | TP53 (1) | C238Y | p53 | Yeast functional assay and direct sequencing |

N/A, Not Available.

More than 25 different mutations were identified in ameloblastoma. BRAF was the most frequently affected gene. BRAF mutations were assessed in 23 studies, involving a total of 530 tumors. Approximately, 71% (n = 377) of the analyzed tumors harbored somatic mutations in BRAF being the V600E mutation the most commonly reported (Figure 3). Other single-nucleotide transversions affecting BRAF were also reported but were uncommon; BRAF T440P was found in two cases [25] and BRAF L597R in one case [6].

SMO was assessed in nine studies [6, 8–10, 13–16, 25] in which 264 tumors were evaluated trough Sanger sequencing, targeted NGS panels and WES. Somatic point mutations in SMO were present in 10.6% (n = 28) of the analyzed samples. L412F was the most common mutation found in 15 cases, followed by W535L in 4 cases and G416E in only one case. One article reported 6/42 cases to harbor mutations in exon 6 and 2/42 cases in exon 9 of the SMO gene [10]. Nevertheless, the authors did not specify more about those mutations (probably they are the aforementioned L412F and W535L, respectively). Three articles identified that SMO mutations were mutually exclusive with BRAF mutations [6, 10, 14], whereas others reported that SMO mutations co-occurred with background BRAF mutations [8]. Five articles did not identify any SMO mutations [9, 13, 15, 16, 25], either through WES [13, 15], targeted NGS panel [16, 25] or Sanger sequencing [9].

Mutations in other genes related to the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway, such as KRAS, NRAS, HRAS, and FGFR2 were identified in 4.3% (12/276) [6, 10, 12, 46], 3.5% (9/254) [10, 14, 16], 2.4% (6/254) [10, 14], and 5.5% (14/254) [6, 8, 12] of the analyzed samples, respectively (Table 3). These mutations tended to be mutually exclusive with BRAF mutations.

Mutations in the tumor suppressor gene TP53, were of low frequency reported only by two studies. Shibata et al. found TP53 mutations in 1 of 12 ameloblastomas [49] and Bartels et al. in 1 of 7 [12]. Kumamoto et al., were unable to find TP53 mutations in their cohort of 10 ameloblastomas [47]. Mutations in other tumor suppressor genes, such as PTEN, are also of low frequency and have been reported in 5/20 [34], 1/7 (12), and 2/62 ameloblastomas [10].

One article reported 45% of their cohort (9/20 ameloblastomas) to harbor missense mutations (in non-SNP sites) affecting TSC1. Correspondingly, those samples showed significantly lower mRNA expression levels compared to normal mucosa, suggesting a higher proliferation rate in ameloblastoma attributed to abnormal mTOR accumulation [40].

Two articles that performed WES reported the presence of mutations affecting KMT2D occurring in the background of BRAF mutations [13, 15]. Guan et al. [13], reported 2/10 ameloblastomas to harbor non-sense mutations in KMT2D, whereas Shi et al. [15], identified 1/4 ameloblastomas with a frameshift deletion in the same gene.

Odontogenesis-related genes have been widely associated with the etiopathogenesis of ameloblastoma. Somatic mutations in BCOR (inactivating frameshift deletion) LRP6, SCN5A (missense mutations in both), and LAMB1 (frameshift deletion) were identified with WES [13], and co-occurred in the background of BRAF mutations. Three missense and one splicing site mutations affecting the ameloblastin gene (AMBN) were found in 4/4 ameloblastomas by direct sequencing [26]. Mutations related to Wnt/β-catenin pathway have been reported affecting CTNNB1 in 3.3% (9/272) of the cases [8, 10, 13, 16, 42, 44, 45, 48]. Likewise, another member of this pathway, APC, was reported by one study to be mutated in 3/6 cases [42] and another study reported four different single nucleotide variations affecting different locus at this gene in a cohort of 30 patients, with a mutation rate that ranged from 6.25 to 27.5% [37] (Table 3). Contrary to this, Tanahashi et al., assessed CTNNB1, APC, AXIN1, and AXIN2 in 18 ameloblastomas, and did not identify any missense mutations in these genes. However, the authors found one silent mutation in AXIN1 and one single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) in AXIN2 [43]. Similarly, Siriwardena et al., did not identify mutations in CTNNB1 among six ameloblastomas [42].

Chromosomal Alterations

Five articles reported chromosomal imbalances in ameloblastomas by using comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) [18, 19], microsatellite markers [27], WES [13] or whole-genome microarray [20]. Overall, these articles reported a relative stability in terms of chromosomal imbalances in ameloblastomas. Jääskeläinen et al., found copy number alterations (CNAs) in 2/17 ameloblastomas [18]; Toida et al., in 1/9 ameloblastomas [19]; whereas Diniz et al., reported seven rare CNAs (affecting 3 ameloblastomas) and 4 copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity (cnLOH) (affecting 2 ameloblastomas) [20]. Nodit et al., reported L-myc and PTEN as the two genes with most allelic losses (71 and 62%, respectively) and that the overal frequency of allelic loss was similar among ameloblastomas and ameloblastic carcinomas.

Discussion

Odontogenic tumors (OT) arise from dental tissues or their remnants, and for decades, this statement was only supported by the histologic appearance of these lesions, which resembles the enamel organ, dental papilla or the dental follicle [1, 50, 51]. Increasing evidence showing mutations and/or chromosomal alterations in the same genes expressed during odontogenesis have confirmed this association, consolidating the close relationship between ontogenesis and oncogenesis [8, 9, 14, 16, 38, 52–60]. The ongoing development of the molecular aspects of odontogenic tumors has revolutionized the understanding of the ethiopathogenesis of these heterogenous group of lesions, allowing the proposal of novel molecular therapeutic targets. However, the exact mechanism underlying the tumorigenic process and possible causes for their different clinical behavior remains unknown.

Both AOT and AM are odontogenic tumors of epithelial origin, but their clinical behavior is diametrically different, resulting in different treatment approaches and prognosis. In the current systematic review, we aimed to compare the genetic alterations of AOT with the ones reported in AM, in order to summarize the current genetic knowledge of these lesions and aid in the understanding of the genomic alterations underlying their development and different behavior.

Our search identified six studies that analyzed the genetic aspects of AOTs (n = 59), in contrast to 37 that explored the genetic landscape of ameloblastoma (n = 530). Mutation in exon 12 of KRAS was found to be present in 76% of AOTs with G12V/R being the most found [22, 23]. On the other hand, mutations in BRAF were found in 71.1% of the samples, corresponding mainly to V600E [6, 25] (Figure 3). Interestingly, the proportion of AOTs with KRAS driver mutation, is similar to the proportion of driver mutations reported in ameloblastoma. Due to its high frequency, KRAS mutations were proposed as a driver mutation and signature marker of AOTs [22–24]. Because KRAS mutations are a recurrent finding in AOTs, Coura et al. [22], suggested the presence of KRAS G12V/R to help in the diagnosis of controversial cases of AOT, in the same way that BRAF V600E could be used in routine ameloblastoma diagnostics [14, 38].

The RAS oncogene family is comprised of three members, KRAS, NRAS, and HRAS, and plays an important role in normal development, but also for cancer development. Activated point mutations on RAS proteins are widely present across a different spectrum of human cancers [61, 62]. Our review showed that all KRAS mutations reported in AOTs have been found affecting codon 12 [22–24]. Mutations affecting this codon have been reported in non-small cell lung cancer and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, being present in almost half of the cases for the former, and in 16% for the latter [63, 64]. KRAS corresponds to a small GTPase that transduces extracellular signals to intracellular signal transduction cascades [65] (Figure 3). It has been suggested that the mutation subtype may affect downstream signaling differently, which could be reflected clinically [66, 67]. Nevertheless, to date, this has not been demonstrated in AOTs. Coura et al., reported in their cohort of 38 AOTs, no statistically significant association between the presence of mutations (mainly KRAS G12V and G12R) and clinicopathological parameters (including patient's age, tumor size, location, follicular or extrafollicular variants, and fibrous capsule thickness) [22].

The activation of RAS/GTP complexes, can activate several downstream signaling pathways such as Raf-MEK-ERK, PI3K-AKT-mTOR, RalGDS-RalA/B, and the TIAM1-RAC1 [65]. To date, only the activation of the MAPK/ERK pathway has been demonstrated in AOT. With immunohistochemistry, Coura et al., demonstrated not only KRAS-mutated cases, but also wild-type KRAS cases to have strong pERK1/2 expression. This suggests that the MAPK pathway can be activated by other mechanisms rather than KRAS mutations [22]. Similarly, using immunohistochemical techniques, Bologna-Molina et al., demonstrated AOTs to express different proteins related to the MAPK/ERK pathway, including EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, CRAF, ERK, and MEK [24].

Apart from KRAS mutations, other somatic point mutations affecting SMO and AMBN [25, 26], and losses affecting 7p15.3 and 6q15 [23], were also found in AOTs. In a similar way, other somatic mutations have been reported in ameloblastoma, mainly affecting: SMO [6, 8, 10, 14], other MAPK pathway-related genes such as KRAS, NRAS, HRAS, FGFR2 [6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16] and in a lower frequency, PTEN [10, 12, 34] and CTNNB1 [8, 10, 12, 13, 16, 34, 42, 44, 45] among others. Interesting results were found by Diniz et al., who reported one ameloblastoma negative for BRAFV600E, with greater number of CNAs and cnLOH encompassing genes directly related with RAF/MAPK pathway activation, suggesting an alternative mechanism of mimicking this pathway [20].

Recently, Bello et al. [68] proposed that the interactions between the adhesion proteins FAK, paxillin and PI3K may be relevant in the aggressiveness of AM compared to AOT, based on the observation that FAK expression was stronger in AM compared to AOT, and that one case of peripheral AM with strong expression of the three proteins had a history of two recurrences. Nevertheless, their conclusions should be carefully interpreted because were based on observations based on a small cohort of AOTs (n = 7).

The biological nature of AOT has been a constant matter of debate. In 2017, Reichart et al. [69], compared the immunohistochemical expression of different factors between AOT and AM, and proposed AOT to be a hamartomatous process rather than a true neoplasm [69]. Markers related to invasion, such as cytokeratin profiles and integrins, to proliferation, such as MDM2, p53 protein and metallothionein levels, were found to be higher in ameloblastomas compared to AOTs. Also, AOTs showed lower levels of matrix metalloproteinases (consistent with a reduced local aggressiveness), Ki76 and anti-apoptosis markers such as Bcl-2, and higher levels of β-catenin (suggesting greater cell adhesion properties) [69]. Similarly, there are publications about the strong cytoplasmatic expression of β-catenin on AOTs [4, 21], however no mutation in CTNNB1 was detected [4]. The proposal of Reichart et al. [69] was based purely on immunohistochemical findings without considering genetic aspect. Although our knowledge about the molecular background of AOT is still very limited, the genetic data collected by this review points to the direction that AOT harbor mutations in important oncogenic driver genes, such as KRAS, and based purely on this, some authors have proposed it as a neoplasm [22]. Nevertheless, until now, the presence of these genetic alteration seems not to have a direct impact on its clinical behavior. Thus, care has to be taken when interpreting these findings.

The low number of studies that have performed small to large-scale and/or “omics” techniques to characterize the molecular background of AOTs, the low frequency of AOT (accounting for <5% of odontogenic tumors) [70–72], limited clinical information availability, and the fact that most of the available studies come from single-institution series or case reports, limit the conclusions than can be drawed out of these findings. Also, current publications are all retrospective studies based on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples (much of them subjected to decalcifications methods), which shows inherent limitations, mainly related to the quality of the nucleic acids for these purposes and the difficulty of retrieving a large cohort. Nevertheless, molecular pathology is demonstrating its utility in the diagnosis of challenging cases and for targeted therapy of disfiguring tumors such as ameloblastoma, avoiding considerable post-surgical morbidities.

Conclusions

The available genetic data reports that 75% of AOTs harbor somatic mutations in KRAS, a well-known oncogene. Nevertheless, the number of studies that have a assessed the genetic landscape of AOT is still very limited, not providing enough evidence to draw a conclusion regarding the relationship between the genomic alterations and its clinical behavior. There are a significant number of studies that have assessed the genetic aspects of ameloblastoma. Different genetic alterations have been reported, being the BRAFV600E mutation the most common. The relatively high frequency of ameloblastoma compared to other odontogenic tumors, such as AOT, has facilitated the performance of different sequencing techniques, allowing the discovery of different mutational signatures. On the contrary, the low frequency of AOTs is an important limitation for this. Thus, the presence of other mutational signatures with clinical impact, co-occurring with KRAS background or in wild-type KRAS cases, cannot be ruled out.

Since BRAF and RAS are in the same MAPK pathway, it is interesting that ameloblastomas, frequently associated with BRAFV600E mutation have aggressive clinical behavior, but in contrast, AOTs, frequently associated with RAS mutations have indolent behavior. Functional studies might be required to solve this question.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA. Revision of the 1992-edition of the WHO histological typing of odontogenic tumours. A suggestion. J Oral Pathol Med. (2002) 31:253–8. 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2002.310501.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright JM, Vered M. Update from the 4th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumours: odontogenic and maxillofacial bone tumors. Head Neck Pathol. (2017) 11:68–77. 10.1007/s12105-017-0794-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Matos FR, Nonaka CF, Pinto LP, de Souza LB, de Almeida Freitas R. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumor: retrospective study of 15 cases with emphasis on histopathologic features. Head Neck Pathol. (2012) 6:430–7. 10.1007/s12105-012-0388-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harnet JC, Pedeutour F, Raybaud H, Ambrosetti D, Fabas T, Lombardi T. Immunohistological features in adenomatoid odontogenic tumor: review of the literature and first expression and mutational analysis of β-catenin in this unusual lesion of the jaws. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. (2013) 71:706–13. 10.1016/j.joms.2012.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Razavi SM, Tabatabaie SH, Hoseini AT, Hoseini ET, Khabazian A. A comparative immunohistochemical study of Ki-67 and Bcl-2 expression in solid ameloblastoma and adenomatoid odontogenic tumor. Dent Res J. (2012) 9:192–7. 10.4103/1735-3327.95235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sweeney RT, McClary AC, Myers BR, Biscocho J, Neahring L, Kwei KA, et al. Identification of recurrent SMO and BRAF mutations in ameloblastomas. Nat Genet. (2014) 46:722–5. 10.1038/ng.2986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kurppa KJ, Catón J, Morgan PR, Ristimäki A, Ruhin B, Kellokoski J, et al. High frequency of BRAF V600E mutations in ameloblastoma. J Pathol. (2014) 232:492–8. 10.1002/path.4317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown NA, Rolland D, McHugh JB, Weigelin HC, Zhao L, Lim MS, et al. Activating FGFR2-RAS-BRAF mutations in ameloblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. (2014) 20:5517–26. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diniz MG, Gomes CC, Guimaraes BV, Castro WH, Lacerda JC, Cardoso SV, et al. Assessment of BRAFV600E and SMOF412E mutations in epithelial odontogenic tumours. Tumour Biol. (2015) 36:5649–53. 10.1007/s13277-015-3238-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gültekin SE, Aziz R, Heydt C, Sengüven B, Zöller J, Safi AF, et al. The landscape of genetic alterations in ameloblastomas relates to clinical features. Virchows Arch. (2018) 472:807–14. 10.1007/s00428-018-2305-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oh KY, Cho SD, Yoon HJ, Lee JI, Ahn SH, Hong SD. High prevalence of BRAF V600E mutations in Korean patients with ameloblastoma: clinicopathological significance and correlation with epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Oral Pathol Med. (2019) 48:413–20. 10.1111/jop.12851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bartels S, Adisa A, Aladelusi T, Lemound J, Stucki-Koch A, Hussein S, et al. Molecular defects in BRAF wild-type ameloblastomas and craniopharyngiomas-differences in mutation profiles in epithelial-derived oropharyngeal neoplasms. Virchows Arch. (2018) 472:1055–9. 10.1007/s00428-018-2323-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guan P, Wong SF, Lim JQ, Ng CCY, Soong PL, Sim CQX, et al. Mutational signatures in mandibular ameloblastoma correlate with smoking. J Dent Res. (2019) 98:652–8. 10.1177/0022034519837248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heikinheimo K, Huhtala JM, Thiel A, Kurppa KJ, Heikinheimo H, Kovac M, et al. The mutational profile of unicystic ameloblastoma. J Dent Res. (2019) 98:54–60. 10.1177/0022034518798810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi Y, Li M, Yu Y, Zhou Y, Wang S. Whole exome sequencing and system biology analysis support the “two-hit” mechanism in the onset of ameloblastoma. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. (2021) e510–7. 10.4317/medoral.24385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yukimori A, Oikawa Y, Morita KI, Nguyen CTK, Harada H, Yamaguchi S, et al. Genetic basis of calcifying cystic odontogenic tumors. PLoS ONE. (2017) 12:e0180224. 10.1371/journal.pone.0180224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barril N, Oliveira PR, Tajara EH. Monosomy 22 and del(10)(p12) in an ameloblastoma previously diagnosed as an adenoid cystic carcinoma of the salivary gland. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. (1996) 91:74–6. 10.1016/S0165-4608(96)00154-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jääskeläinen K, Jee KJ, Leivo I, Saloniemi I, Knuutila S, Heikinheimo K. Cell proliferation and chromosomal changes in human ameloblastoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. (2002) 136:31–7. 10.1016/S0165-4608(02)00512-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toida M, Balázs M, Treszl A, Rákosy Z, Kato K, Yamazaki Y, et al. Analysis of ameloblastomas by comparative genomic hybridization and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. (2005) 159:99–104. 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diniz MG, Duarte AP, Villacis RA, Guimaraes BVA, Duarte LCP, Rogatto SR, et al. Rare copy number alterations and copy-neutral loss of heterozygosity revealed in ameloblastomas by high-density whole-genome microarray analysis. J Oral Pathol Med. (2017) 46:371–6. 10.1111/jop.12505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santos HBP, Medeiros HCM, Mafra RP, Miguel MCC, Galvão HC, de Souza LB. Regulation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway may be related to Regγ in benign epithelial odontogenic lesions. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. (2019) 128:43–51. 10.1016/j.oooo.2018.12.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coura BP, Bernardes VF, de Sousa SF, França JA, Pereira NB, Pontes HAR, et al. KRAS mutations drive adenomatoid odontogenic tumor and are independent of clinicopathological features. Modern Pathol. (2019) 32:799–806. 10.1038/s41379-018-0194-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomes CC, de Sousa SF, de Menezes GH, Duarte AP, Pereira Tdos S, Moreira RG, et al. Recurrent KRAS G12V pathogenic mutation in adenomatoid odontogenic tumours. Oral Oncol. (2016) 56:e3–5. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bologna-Molina R, Ogawa I, Mosqueda-Taylor A, Takata T, Sánchez-Romero C, Villarroel-Dorrego M, et al. Detection of MAPK/ERK pathway proteins and KRAS mutations in adenomatoid odontogenic tumors. Oral Dis. (2019) 25:481–7. 10.1111/odi.12989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shimura M, Nakashiro K-I, Sawatani Y, Hasegawa T, Kamimura R, Izumi S, et al. Whole exome sequencing of SMO, BRAF, PTCH1 and GNAS in odontogenic diseases. In Vivo. (2020) 34:3233. 10.21873/invivo.12159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Perdigão PF, Gomez RS, Pimenta FJ, De Marco L. Ameloblastin gene (AMBN) mutations associated with epithelial odontogenic tumors. Oral Oncol. (2004) 40:841–6. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2004.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nodit L, Barnes L, Childers E, Finkelstein S, Swalsky P, Hunt J. Allelic loss of tumor suppressor genes in ameloblastic tumors. Mod Pathol. (2004) 17:1062–7. 10.1038/modpathol.3800147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Derakhshan S, Aminishakib P, Karimi A, Saffar H, Abdollahi A, Mohammadpour H, et al. High frequency of BRAF V600E mutation in Iranian population ameloblastomas. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. (2020) 25:e502–7. 10.4317/medoral.23519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sant'Ana MSP, dos Santos Costa SF, da Silva MP, Martins-Chaves RR, Pereira TdSF, de Oliveira EM, et al. BRAF p.V600E status in epithelial areas of ameloblastoma with different histological aspects: implications to the clinical practice. J Oral Pathol Med. (2021) 50:478–84. 10.1111/jop.13155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seki-Soda M, Sano T, Ito K, Yokoo S, Oyama T. An immunohistochemical and genetic study of BRAFV600E mutation in Japanese patients with ameloblastoma. Pathol Int. (2020) 70:224–30. 10.1111/pin.12899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang R, Yang Q, Qu J, Hong Y, Liu P, Li T. The BRAF p.V600E mutation is a common event in ameloblastomas but is absent in odontogenic keratocysts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. (2020) 129:229–35. 10.1016/j.oooo.2019.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Duarte-Andrade FF, Silva AMB, Vitório JG, Canuto GAB, Costa SFS, Diniz MG, et al. The importance of BRAF-V600E mutation to ameloblastoma metabolism. J Oral Pathol Med. (2019) 48:307–14. 10.1111/jop.12839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oh KY, Cho SD, Yoon HJ, Lee JI, Hong SD. Discrepancy between immunohistochemistry and sequencing for BRAF V600E in odontogenic tumours: comparative analysis of two VE1 antibodies. J Oral Pathol Med. (2021) 50:85–91. 10.1111/jop.13108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Narayan B, Urs AB, Augustine J, Singh H, Polipalli SK, Kumar S, et al. Genetic alteration of Exon 5 of the PTEN gene in Indian patients with ameloblastoma. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. (2019) 127:225–30. 10.1016/j.oooo.2018.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xia R-H, Zhang C-Y, Sun J-J, Tian Z, Hu Y-H, Gu T, et al. Ameloblastoma with mucous cells: a clinicopathological, BRAF mutation, and MAML2 rearrangement study. Oral Dis. (2020) 26:805–14. 10.1111/odi.13281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soltani M, Tabatabaiefar MA, Mohsenifar Z, Pourreza MR, Moridnia A, Shariati L, et al. Genetic study of the BRAF gene reveals new variants and high frequency of the V600E mutation among Iranian ameloblastoma patients. J Oral Pathol Med. (2018) 47:86–90. 10.1111/jop.12610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li N, Liu B, Sui C, Jiang Y. Analysis of APC mutation in human ameloblastoma and clinical significance. Springerplus. (2016) 5:314. 10.1186/s40064-016-1904-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pereira NB, Pereira KM, Coura BP, Diniz MG, de Castro WH, Gomes CC, et al. BRAFV600E mutation in the diagnosis of unicystic ameloblastoma. J Oral Pathol Med. (2016) 45:780–5. 10.1111/jop.12443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brunner P, Bihl M, Jundt G, Baumhoer D, Hoeller S. BRAF p .V600E mutations are not unique to ameloblastoma and are shared by other odontogenic tumors with ameloblastic morphology. Oral Oncol. (2015) 51:e77–8. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2015.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li N, Liu B, Zhong M, Chen Y. Detection of tuberous sclerosis complex 1 expression and direct sequencing in ameloblastoma. Acta Medica Mediterranea. (2014) 30:827–33. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oikawa M, Miki Y, Shimizu Y, Kumamoto H. Assessment of protein expression and gene status of human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) family molecules in ameloblastomas. J Oral Pathol Med. (2013) 42:424–34. 10.1111/jop.12024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Siriwardena BS, Kudo Y, Ogawa I, Tilakaratne WM, Takata T. Aberrant beta-catenin expression and adenomatous polyposis coli gene mutation in ameloblastoma and odontogenic carcinoma. Oral Oncol. (2009) 45:103–8. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2008.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanahashi J, Daa T, Yada N, Kashima K, Kondoh Y, Yokoyama S. Mutational analysis of Wnt signaling molecules in ameloblastoma with aberrant nuclear expression of β-catenin. J Oral Pathol Med. (2008) 37:565–70. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2008.00645.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miyake T, Tanaka Y, Kato K, Tanaka M, Sato Y, Ijiri R, et al. Gene mutation analysis and immunohistochemical study of beta-catenin in odontogenic tumors. Pathol Int. (2006) 56:732–7. 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2006.02039.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawabata T, Takahashi K, Sugai M, Murashima-Suginami A, Ando S, Shimizu A, et al. Polymorphisms in PTCH1 affect the risk of ameloblastoma. J Dent Res. (2005) 84:812–6. 10.1177/154405910508400906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kumamoto H, Takahashi N, Ooya K. K-Ras gene status and expression of Ras/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling molecules in ameloblastomas. J Oral Pathol Med. (2004) 33:360–7. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2004.00141.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumamoto H, Izutsu T, Ohki K, Takahashi N, Ooya K. p53 gene status and expression of p53, MDM2, and p14 proteins in ameloblastomas. J Oral Pathol Med. (2004) 33:292–9. 10.1111/j.0904-2512.2004.00044.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sekine S, Sato S, Takata T, Fukuda Y, Ishida T, Kishino M, et al. Beta-catenin mutations are frequent in calcifying odontogenic cysts, but rare in ameloblastomas. Am J Pathol. (2003) 163:1707–12. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63528-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shibata T, Nakata D, Chiba I, Yamashita T, Abiko Y, Tada M, et al. Detection of TP53 mutation in ameloblastoma by the use of a yeast functional assay. J Oral Pathol Med. (2002) 31:534–8. 10.1034/j.1600-0714.2002.00006.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pindborg JJ, Kramer IRH, Torloni H. Histological Typing of Odontogenic Tumours, Jaw Cysts, and Allied Lesions. Geneva: World Health Organization; (1971). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kramer IR, Pindborg JJ, Shear M. WHO International Histological Classification of Tumours: Histological Typing of Odontogenic Tumours. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agaimy A, Skalova A, Franchi A, Alshagroud R, Gill AJ, Stoehr R, et al. Ameloblastic fibrosarcoma: clinicopathological and molecular analysis of seven cases highlighting frequent BRAF and occasional NRAS mutations. Histopathology. (2020) 76:814–21. 10.1111/his.14053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Coura BP, Bernardes VF, Ferreira de Sousa S, Diniz MG, Moreira RG, Benevenuto de Andrade BA, et al. Targeted next-generation sequencing and allele-specific qPCR of laser capture microdissected samples uncover molecular differences in mixed odontogenic tumors. J Mol Diagnostics. (2020) 1393–9. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2020.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Diniz MG, Galvão CF, Macedo PS, Gomes CC, Gomez RS. Evidence of loss of heterozygosity of the PTCH gene in orthokeratinized odontogenic cyst. J Oral Pathol Med. (2011) 40:277–80. 10.1111/j.1600-0714.2010.00977.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heikinheimo K, Jee KJ, Niini T, Aalto Y, Happonen RP, Leivo I, et al. Gene expression profiling of ameloblastoma and human tooth germ by means of a cDNA microarray. J Dent Res. (2002) 81:525–30. 10.1177/154405910208100805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heikinheimo K, Kurppa KJ, Laiho A, Peltonen S, Berdal A, Bouattour A, et al. Early dental epithelial transcription factors distinguish ameloblastoma from keratocystic odontogenic tumor. J Dent Res. (2015) 94:101–11. 10.1177/0022034514556815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu SJ, Parker J, Divaris K, Padilla R, Murrah V, Wright JT. Ameloblastoma phenotypes reflected in distinct transcriptome profiles. Sci Rep Uk. (2016) 6:1–10. 10.1038/srep30867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Juuri E, Isaksson S, Jussila M, Heikinheimo K, Thesleff I. Expression of the stem cell marker, SOX2, in ameloblastoma and dental epithelium. Eur J Oral Sci. (2013) 121:509–16. 10.1111/eos.12095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kumamoto H, Ohki K, Ooya K. Expression of Sonic hedgehog (SHH) signaling molecules in ameloblastomas. J Oral Pathol Med. (2004) 33:185–90. 10.1111/j.0904-2512.2004.00070.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qu J, Yu F, Hong Y, Guo Y, Sun L, Li X, et al. Underestimated PTCH1 mutation rate in sporadic keratocystic odontogenic tumors. Oral Oncol. (2015) 51:40–5. 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2014.09.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Haigis KM. KRAS alleles: the devil is in the detail. Trends Cancer. (2017) 3:686–97. 10.1016/j.trecan.2017.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jančík S, Drábek J, Radzioch D, Hajdúch M. Clinical relevance of KRAS in human cancers. J Biomed Biotechnol. (2010) 2010:150960. 10.1155/2010/150960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Salgia R, Pharaon R, Mambetsariev I, Nam A, Sattler M. The improbable targeted therapy: KRAS as an emerging target in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Cell Rep Med. (2021) 2:100186. 10.1016/j.xcrm.2020.100186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Waters A, Der C. KRAS: the critical driver and therapeutic target for pancreatic cancer. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Med. (2017) 8:a031435. 10.1101/cshperspect.a031435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Román M, Baraibar I, López I, Nadal E, Rolfo C, Vicent S, et al. KRAS oncogene in non-small cell lung cancer: clinical perspectives on the treatment of an old target. Mol Cancer. (2018) 17:33. 10.1186/s12943-018-0789-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Biernacka A, Tsongalis PD, Peterson JD, de Abreu FB, Black CC, Gutmann EJ, et al. The potential utility of re-mining results of somatic mutation testing: KRAS status in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Genet. (2016) 209:195–8. 10.1016/j.cancergen.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kim EY, Kim A, Kim SK, Kim HJ, Chang J, Ahn CM, et al. KRAS oncogene substitutions in Korean NSCLC patients: clinical implication and relationship with pAKT and RalGTPases expression. Lung Cancer. (2014) 85:299–305. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bello IO, Alrabeeah MA, AlFouzan NF, Alabdulaali NA, Nieminen P. FAK, paxillin, and PI3K in ameloblastoma and adenomatoid odontogenic tumor. Clin Oral Investig. (2021) 25:1559–67. 10.1007/s00784-020-03465-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reichart P, Philipsen H, Khongkhunthian P, Sciubba J. Immunoprofile of the adenomatoid odontogenic tumor. Oral Dis. (2017) 23:731–6. 10.1111/odi.12572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nalabolu GRK, Mohiddin A, Hiremath SKS, Manyam R, Bharath TS, Raju PR. Epidemiological study of odontogenic tumours: an institutional experience. J Infect Public Health. (2017) 10:324–30. 10.1016/j.jiph.2016.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Siriwardena B, Crane H, O'Neill N, Abdelkarim R, Brierley DJ, Franklin CD, et al. Odontogenic tumors and lesions treated in a single specialist oral and maxillofacial pathology unit in the United Kingdom in 1992-2016. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. (2019) 127:151–66. 10.1016/j.oooo.2018.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Philipsen HP, Reichart PA. Adenomatoid odontogenic tumour: facts and figures. Oral Oncol. (1999) 35:125–31. 10.1016/S1368-8375(98)00111-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.