Two years after the first known outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the cumulative number of confirmed cases of infections has exceeded 260 million worldwide. Even more alarming, the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and its many variants are still circulating on a massive scale in the world population. Here, we present a brief analysis on the most widely spread SARS-CoV-2 variant, known as the ‘Delta variant’, with particular emphases on environmental transmission, knowledge gaps, hypotheses, and urgent questions.

A new situation

Has the long-sought relief finally arrived 18 months after the COVID-19 was declared a pandemic? Not really. Recent surges of new infections painted a dire picture. In the week ending on July 18, 2021, 4 weeks since the onset of the latest wave of the COVID-19 outbreak in Europe, there were nearly 300,000 newly confirmed cases in the United Kingdom and about one million newly confirmed cases in total across Europe (WHO 2021a). In the following week, the number of newly confirmed cases in the United States reached 370,000 after steadily dropping to about 80,000 per week levels since it peaked at the beginning of January 2021 (WHO 2021a). In China, where the new weekly cases of domestic COVID-19 infections had been kept under 500 since February 2021, about 2500 newly confirmed cases were reported in the week ending on May 23, effectively ending the quasi-safe status of domestic COVID-19 infections in the country (WHO 2021a). Since then, weekly new confirmed cases of COVID-19 have steadily increased around the globe, from about 2.6 million in mid-June to the peak of 4.6 million in late August and now rising to 4.0 million again, triggering a massive wave of new infections. The eradication of COVID-19 looks like a distant goal in the coming months near the end of 2021 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The Delta variant (B.1.617.2 and AY. *) of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has triggered a massive wave of new infections and re-emergent outbreaks around the globe, making the eradication of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a more distant goal and adding significant uncertainty to the future of mankind

A super-spreading variant

There is active surveillance on the emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants. The phylogenetic assignment of named global outbreak network (PANGO) and the global initiative on sharing all influenza data (GISAID) referred to the B.1.617.2 and all AY.* as the ‘Delta variant’, which constitutes a class of mutant strains of the SARS-CoV-2, the causation agent of the COVID-19 pandemic (GISAID 2021; PN 2021). Since it was first discovered in October 2020, the Delta variant has spread to most countries around the globe and become the predominant circulating SARS-CoV-2 variant in newly confirmed cases of COVID-19 (Yadav et al. 2021a) (Fig. 2). In India, where the Delta variant was first detected, it was identified as the main causation agent for the massive COVID-19 outbreak in the country between March and May 2021, a period with record numbers of infections and overlapping with the Kumbh Mela pilgrimage and festival (THS 2021). According to the US centers for disease control and prevention (CDC), the B.1.617.2 variant was responsible for 99.9% of total confirmed cases between September 18 and 25 in the United States (CDC 2021a). Similar situations were reported in the United Kingdom and China where the Delta variant accounted for 100% of the newly confirmed cases of COVID-19 in the 4 weeks ending on October 20 (GISAID 2021). As of December 1, 2021, a total of 176 countries and regions have verified cases of infections by the Delta (B.1.617.2) variant (CDC 2021b).

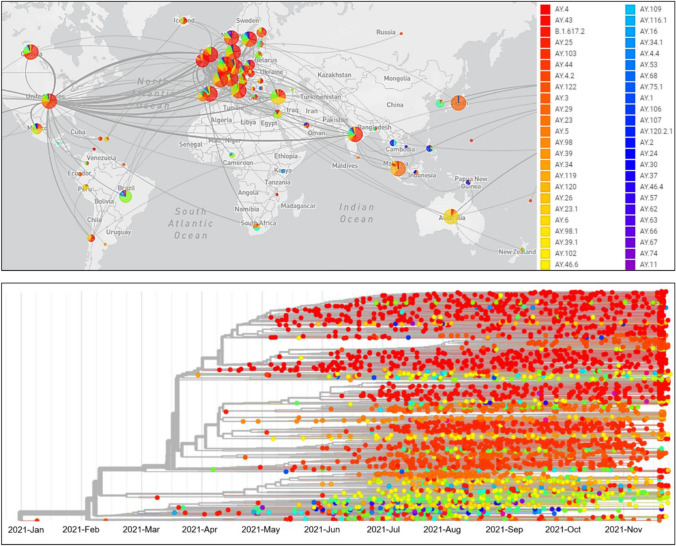

Fig. 2.

Transmissions of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Delta variant around the globe (top). Phylogeny of the Delta variant of 3948 genomes collected between January 2021 and November 2021 (bottom). Source: global initiative on sharing all influenza data (GISAID 2021). GISAID is the largest open-access portal, hosting the genome sequences and related epidemiological and clinical data of more than 5.6 million SARS-CoV-2 strains. All data were last updated on 30 November 2021

What makes the Delta variant so dangerous?

The most representative variant, B.1.617.2, is the predominant and the initial pango lineage of the Delta variant (CDC 2021a). At present, there is no proof that the transmission routes of the B.1.617.2 variant are significantly different from those of the original SARS-CoV-2, although there is strong evidence that the transmissibility of B.1.617.2 is much higher than the original SARS-CoV-2.

Compared with the original virus, B.1.617.2 is characterized by seven mutations on its spike proteins, namely, the T19R, Δ157-158, L452R, T478K, D614G, P681R, and D950N (ECDC 2021). There are five connected amino acids, proline, arginine, arginine, alanine, and arginine, located at the junction of the spike protein subunits on the original SARS-CoV-2, where they form an amino acid chain known as the furin cleavage site. As it mutates into the B.1.617.2 variant, the proline on the furin cleavage site is replaced by arginine (P681R), which reduces the acidity of this sequence (Planas et al. 2021). The result is that the furin host enzymes can more effectively recognize and cut the spike proteins on replicated viruses before they leave the host cell, which enables more spike proteins to invade human cells and facilitates the fusion between the virus envelope and the host cell membrane, thereby increasing the probability of infection in the new host (Scudellari 2021). To put it into context, about 50% of the spike proteins on SARS-CoV-2 are available for invading human cells, whereas on B.1.617.2 more than 75% of the spike proteins are capable of effectuating such actions (Scudellari 2021). Moreover, a recent study reported that L452R is also a contributor to the enhanced infectivity of B.1.617.2 by promoting interactions between the spike protein and the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor (Kimura et al. 2021).

These may be the key factors of the higher viral loads found in Delta variant-infected individuals and the higher transmissibility of this particular variant compared with the original SARS-CoV-2 (Choi et al. 2021a; Young et al. 2018) (Fig. 3). Further, some of these spike protein mutations may affect human immune responses directed toward the key antigenic regions of the receptor-binding protein (452 and 478) and the deletion of part of the N-terminal domain, which may explain the reduced effectiveness rates of current vaccines toward this variant (Bernal et al. 2021). In conclusion, the B.1.617.2 variant poses a more dangerous threat than the original SARS-CoV-2.

Fig. 3.

The Delta variant has higher transmissibility compared with the original severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), and has become the dominating causation agent of newly confirmed infections in the global population, as of 30 November 2021

Knowledge gaps concerning the environmental transmission of B.1.617.2 variant

There are important differences between the original SARS-CoV-2 and the B.1.617.2 variant. Table 1 lists the current findings and highlights the knowledge gaps on the latter in the current literature. Li et al. (2021a) reported that the mean oropharyngeal swab viral load of B.1.617.2-infected individuals was about 1260 times higher than that of the cases infected by the original SARS-CoV-2. Notably, Zhang et al. (2021) reported that the transmissibility of the B.1.617.2 variant was substantially higher than the latter, which is consistent with the earlier findings by Bjorkman et al. (2021), who showed that viral load is positively correlated to transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2.

Table 1.

Data pertinent to the environmental transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the Delta (B.1.617.2) variant with knowledge gaps highlighted on the latter

| Characteristic | SARS-CoV-2 (original) | B.1.617.2 (Delta) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transmissibility |

GT = 5.7 d R0 = 2.2 |

GT = 2.9 d R0 = 3.2 |

Zhang et al. (2021) |

| Oropharyngeal swab viral load |

n = 63 Ct = 34.3 |

n = 62 Ct = 24.00 Mean viral load was 1,260 times higher than those in SARS-CoV-2 infections |

Li et al. (2021a) |

| Viral load in patient's feces |

1.17 ± 0.32 log10 copies/mL (recovery stage) 2.18 ± 0.11 log10 copies/mL (acute stage) 2.01 ± 0.28 log10 copies/mL (recovery stage) |

No data at present | Jeong et al. (2020) |

| Mean incubation period | 5.2 d | 4.4 d | Zhang et al. (2021) |

|

Environmental persistence (aerosols) |

At 23 ℃ and 53% relative humidity, SARS-CoV-2 on aerosols maintained the ability to replicate after 16 h At 21–23 ℃ and 40% relative humidity, SARS-CoV-2 survived on aerosols for 3 h with a moderate reduction in infection titer |

No data at present |

van Doremalen et al. (2020) Fears et al. (2020) |

|

Environmental persistence (on surfaces) |

SARS-CoV-2 survived for 2 h–9 d on various types of common surfaces | No data at present | WHO (2020a) |

|

Environmental persistence (in water & wastewater) |

At 20 ℃, 10% of the initial viral titer (3.16 × 104 TCID50/mL) remained after 1.9–2.9 d in river water and 1.0–1.3 d in seawater At 20 ℃, almost no initial viral titer (103 TCID50/mL) remained after 3.2–6.5 d in municipal wastewater and 3.6–4.4 d in tap water |

No data at present |

Buonerba et al. (2021) Sala-Comorera et al. (2021) |

| Environmental transmission |

Inhalation of respiratory droplets ejected from the nose or mouth of an infected person Inhalation of aerosols (e.g., airborne particulates, droplet nuclei) carrying viruses Touching eyes, nose or mouth by hand contacted with virus-laden surfaces or objects (‘fomites’) Fecal–oral transmission possible |

No data at present |

Choi (2021c) Han and He (2021) WHO (2020b) |

| Protection by face mask (surgical) | When the spreader and the receiver models were separated by 50 cm and both wore surgical masks, 71% of the viral titer and 76% of the viral RNA from the spreader were blocked by the masks, respectively | No data at present | Ueki et al. (2020) |

| Social distancing requirement |

≥ 1.0 m (WHO) ≥ 1.8 m (6 feet) (CDC) |

≥ 2.5 m |

CCTV (2021) CDC (2021c) WHO (2021b) |

Abbreviations (in the order of appearance in the table): mean generation time (GT); basic reproductive number (R0); sample size (n), number of cycles when amplification reaches a certain load in polymerase chain reaction (Ct, lower Ct value indicates higher viral load of infection); median tissue culture infective dose (TCID50)

In Japan, the minimum social distance for mitigating human-to-human transmission of the B.1.617.2 variant was determined as 2.5 m based on simulations by the Fuyue supercomputer, compared with the earlier recommendation of 1.0 and 1.8 m social distancing for the original SARS-CoV-2 (CCTV 2021; CDC 2021c; WHO 2021b). It should be noted that all these recommended social distances—which are widely implemented by public health authorities for the infection prevention and control of COVID-19—are based on virus transmission by respiratory droplets. In reality, SARS-CoV-2 can survive on aerosols for 3–16 h under the room temperature and travel long distances in air (van Doremalen et al. 2020; Fears et al. 2020). Using computational fluid dynamics simulations, Rosti et al. (2020) showed that dry aerosols carrying SARS-CoV-2 could travel to 7.5 m in 20 min without the influence of ambient airflows. Indeed, airborne transmission has been recognized as an important route for the spread of COVID-19, especially in enclosed public spaces with poor ventilation (CDC 2021d; Chen et al. 2021; Choi et al. 2021b; He and Han 2021a; Morawska and Milton 2020; Sun et al. 2021). However, given the fact that there are no scientific data published to date on the persistence of the B.1.617.2 variant on aerosols, it is difficult to estimate the level of risks regarding the airborne transmission of the B.1.617.2 variant, which represents a major knowledge gap concerning the environmental transmission of the Delta variant.

Wearing face masks has been widely adopted as a mandate in public settings to contain the virus spread. There are currently no data on the effectiveness of protection against the B.1.617.2 variant by wearing face masks, although it is almost certain that due to the much higher viral loads in the respiratory tract of B.1.617.2-infected individuals, risks are likely to be substantially higher for those who do not wear masks in public places. Further, as imperfect fitting on wearers often leads to leakages from face masks, it would be more difficult to achieve the same level of protection against the B.1.617.2 variant for mask-wearers under similar situations. Previous studies showed that the nose and mouth of mask-wearers could inhale aerosols containing influenza viruses from the interspacing between the face and the mask (Cowling et al. 2010; He et al. 2013). A recent study showed that more than half of the small respiratory droplets (0.5–20 μm) ejected from a talking person wearing a standard face mask would be leaked from the top, with 15% leaked from the side and another 9% from the bottom of the mask (Cappa et al. 2021).

The fecal–oral route has been recognized as a potential route of transmission for SARS-CoV-2 (Han and He 2021; Sun and Han 2021a, 2021b). No data have been reported on the viral load of the B.1.617.2 variant in the feces of infected individuals. Recent studies on the original SARS-CoV-2 have found that there were generally high viral loads of the virus in the feces of COVID-19 patients, posing risks of fecal–oral transmission (Gu et al. 2020; Jeong et al. 2020; Olusola-Makinde and Reuben 2020; Sharma et al. 2021; Singh et al. 2021; Xiao et al. 2020). Since SARS-CoV-2 can replicate in gastrointestinal environments by binding to ACE2 receptors, and that the P681R and L452R provide more binding sites with enhanced fusion between the virus envelope and the host cell membrane, it is reasonable to anticipate that the viral load of B.1.617.2 is likely to be substantially higher in the feces of infected individuals, similar to findings in the respiratory tract and increasing the likelihood of virus transmission via fecal–oral routes. These knowledge gaps present urgent questions to the research community. Clinical and experimental data—both must be rigorously designed and executed—are needed to address these gaps and to inform public health authorities and the public for implementing more effective prevention and control measures on the Delta variant.

Effectiveness of current vaccines on the Delta variant

Do current vaccines provide meaningful protection against the Delta variant? Since there is currently no specific treatment for COVID-19, vaccination is the most effective means to prevent the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, including its variants (Dai et al. 2021). There were speculations that all current vaccines may only have limited effectiveness to protect people against infections by the Delta variant (BFA 2021). Indeed, post-vaccination infections by the Delta variant have been reported in some individuals, raising concerns on the efficacy of the current vaccines (Grant et al. 2021; Li et al. 2021b). Nonetheless, clinical and laboratory testing data published to date are generally positive showing their considerable effectiveness against the B.1.617.2 variant. Table 2 lists the testing results of four COVID-19 vaccines, namely, the BNT162b2 vaccine developed by Pfizer, the AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) vaccine by AstraZeneca, the CoronaVac vaccine by Sinovac, and the China National Biotec Group (CNBG) vaccine, on the original SARS-CoV-2 and the B.1.617.2 variant, respectively. Results from phase III clinical trials of the four COVID-19 vaccines showed that they were moderately to highly effective in preventing infections by SARS-CoV-2 after receiving two doses of vaccination.

Table 2.

Effectiveness of current vaccines against the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and the Delta (B.1.617.2) variant

| Vaccine type | SARS-CoV-2 (original) | B.1.617.2 (Delta variant) | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| BNT162b2 (Pfizer) |

n = 43,448 Effectiveness ratea: 95% |

n = 15,749 Effectiveness ratea: 88% |

Bernal et al. (2021) Pfizer (2020) |

|

n = 12,330 (0–13 d after two dose) Effectiveness ratea: 82%b |

Pouwels et al. (2021) | ||

|

n = 215,577 (≥ 14 d after two doses) Effectiveness ratea: 80%b |

|||

|

n = 1,043,289 (≥ 7 d after two doses) Effectiveness ratea: 93% (within the first month after two doses) Effectiveness ratea: 53% (≥ 4 months after two doses) |

Tartof et al. (2021) | ||

|

n = 25 Geometric mean neutralization titerc: 1,105 |

n = 25 Geometric mean neutralization titerc: 442 |

Liu et al. (2021a) | |

|

n = 19 Geometric mean neutralization titerc: 246.8 |

n = 19 Geometric mean neutralization titerc: 106.7 (delta-S1), 123.4 (delta-S2) |

Lustig et al. (2021) | |

|

AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) |

n = 32,451 Effectiveness ratea: 74% |

n = 8244 Effectiveness ratea: 67% |

Bernal et al. (2021) Falsey et al. (2021) |

|

n = 49,308 (0–13 d after two dose) Effectiveness ratea: 71%b |

Pouwels et al. (2021) | ||

|

n = 330,677 (≥ 14 d after two doses) Effectiveness ratea: 67%b |

|||

|

n = 49 Geometric mean neutralization titerc: 599.4 |

n = 49 Geometric mean neutralization titerc: 88.4 |

Thiruvengadam et al. (2021) | |

|

n = 25 Geometric mean neutralization titerc: 306 |

n = 25 Geometric mean neutralization titerc: 71 |

Liu et al. (2021a) | |

| CoronaVac |

n = 1,322 Effectiveness ratea: 91.25% |

n = 89 Effectiveness ratea: 59% (included both CoronaVac and CNBG vaccines, and most participants were vaccinated with the former) |

Li et al. (2021b) SINOVAC (2020) |

| China National Biotec Group (CNBG) |

n is unknown Effectiveness ratea: 79.34% |

CNBG (2020) |

(a) Effectiveness rates were determined by whether participants, all vaccinated with two doses of the designated vaccine, had COVID-19 infection. (b) Effectiveness rates in B.1.617.2-dominant periods in the United Kingdom. (c) Geometric mean neutralization titers were determined in sera from participants vaccinated with two doses of the designated vaccine

Bernal et al. (2021) recently evaluated the effectiveness of the BNT162b2 and AZD1222 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 variant. Their results showed an overall effectiveness rate of 88% among 15,749 vaccinated participants receiving two doses of the former, and an effectiveness rate of 67% in 8244 participants vaccinated by the latter, also receiving two doses. Liu et al. (2021a) studied the neutralization ability of serum samples collected from 50 participants who had been vaccinated with two doses of the BNT162b2 or AZD1222 vaccine. The study showed that the geometric mean neutralization titer of the B.1.617.2 variant decreased by 2.5 to 4.3-fold in sera from participants (n = 25) vaccinated with two doses of either vaccine, compared with that of the original SARS-CoV-2. Similar results were reported by Lustig et al. (2021), where the geometric mean neutralization titer of delta-S1 and delta-S2 (S1 and S2 are two branches of the B.1.617.2 lineage) decreased by 2.6 and 2.1-fold in sera from participants vaccinated with two doses of the BNT162b2 vaccine, respectively. Li et al. (2021b) studied the effectiveness of two inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines against the Delta variant, the CoronaVac and the China National Biotec Group (CNBG), in a recent outbreak in Guangzhou, China. The study showed an overall effectiveness rate of 59% among 89 vaccinated participants receiving two doses of any of the two vaccines or a mix of both, although most participants were vaccinated with the former. It was concluded that, although their effectiveness rates decreased to some extent, the current vaccines developed for SARS-CoV-2 still provide considerable protection against the Delta variant.

What next after the Delta variant?

As of November 30, 2021, the Delta variant is the only SARS-CoV-2 variant being categorized as ‘Variant of Concern’ by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), based on evidence on its increased transmissibility and potential reduction in neutralization by some Emergency Use Authorization monoclonal antibody treatments and post-vaccination sera (CDC 2021e). The Delta variant has caused massive infections around the globe, including areas with high vaccination rates. In January 2021, Zvulun (2021) reported that Israel could become the first country in the world to achieve mass immunization by COVID-19 vaccines. As of March 22, 2021, more than half of the Israeli population (53.1%) had been vaccinated with two doses of the BNT162b2 (Pfizer) vaccine (TN 2021a). The Israeli government subsequently abolished the mask order on June 15, 2021 (XH 2021). Shortly after, new COVID-19 infections began to rebound in Israel, and the Delta variant spread rapidly in the country (TN 2021b; WHO 2021c). On September 7, 2021, new daily confirmed cases in Israel set a record of 5000 since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, despite the fact that more than 60% of its population had been fully vaccinated (WHO 2021c).

Like other RNA viruses, SARS-CoV-2 has very high mutation rates (Akter et al. 2021; Dai et al. 2020; Duffy 2018; Wu et al. 2021). To date, a total of 407 pango lineages of SARS-CoV-2 variants have been identified (Nextstrain 2021). Of those, the B.1.617.2.1 (AY.1) and Lambda (C.37) variants—both have been identified with cases reported in different countries—have stronger immune escape ability than the B.1.617.2 variant, meaning that current vaccines are likely to be even less effective on these strains (Kimura et al. 2021; Liu et al. 2021b; Newsweek 2021; Yadav et al. 2021b). Recently, the AY.4.2 variant, known as the ‘Delta Plus’, has spread in the United Kingdom, which would be 10% more transmissible than its parent lineage, the B.1.617.2 (Newsweek 2021). It is of concern that, at present, both the original SARS-CoV-2 and its various variants are still being transmitted on a large scale between different hosts and species, as global newly confirmed cases have been maintained at about three million per week or above since the beginning of July 2021 (He et al. 2021; WHO 2021a). Morales et al. (2021) estimated that the true underlying mutation rate of SARS-CoV-2 is about 50% higher than previous estimates. If the transmission is not effectively contained, what is bound to happen is that the novel coronavirus, including SARS-CoV-2 and its variants, will continue to evolve into newer variants that are potentially more contagious and difficult to control (Fig. 4). As the virus continues to mutate, public health authority has warned of the possibility that eventually, some new SARS-CoV-2 variants will emerge which may render all current vaccines ineffective (SAGE 2021). There may also be new or under-investigated environmental transmission routes of these newer SARS-CoV-2 variants emerging in the future (Propper 2020).

Fig. 4.

Mutations of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) with its main variants identified to date. The Delta variant, which includes the B.1.617.2 and AY.* pango lineages, has become the dominant causation agent of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infections reported around the globe. As of 30 November 2021, a total of 407 pango lineages have emerged since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The continuing massive scale of transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and its variants may lead to the emergence of potentially more dangerous 'super-variants' in the future

A new ‘super variant’ of SARS-CoV-2—named as the ‘Omicron’ variant (B.1.1.529) which was first discovered in South Africa on 9 November 2021—has been reported and designated as a ‘Variant of Concern’ by the World Health Organization (WHO 2021d). Preliminary findings on the new variant immediately raised widespread concerns due to its unusually high number of mutations, which could make it more transmissible and result in immune evasion with increased risks of reinfection (Callaway 2021). The Omicron variant has 32 mutated sites on its spike proteins, with some associated with the transmissibility and immune escape ability of the virus. While studies are still being carried out to assess its threats and the efficacy of current vaccines on the Omicron variant, researchers have warned that the immune escape ability of the Omicron variant may exceed all previous SARS-CoV-2 variants, including the dominant Delta variant. In that sense, the Omicron variant may be the first ‘super-variant’ of SARS-CoV-2. Governments and public health authorities have responded swiftly by implementing travel bans and surveillance systems, providing booster shots, and informing the public of the current situation on the Omicron variant (CDC 2021f; NYT 2021; WHO 2021d). If the Omicron variant proves to be a more transmissible or deadly SARS-CoV-2 variant, scientists and public health authorities will face the urgent tasks of re-assessing its environmental transmission modes, environmental persistence, and prioritizing future infection prevention and control efforts. Meanwhile, the WHO reiterated that the Delta variant is still the major current cause of the pandemic, despite the recent concerns on the new Omicron variant (Choudhury 2021).

In light of the current knowledge gaps and urgent situations, we put forward the following recommendations and urgent questions. First, we recommend that face masks should continue to be worn in addition to social distancing requirements in areas with active COVID-19 transmission. This is a lesson from Israel's recent re-emergent outbreaks of COVID-19 infections. Secondly, we appeal to people all over the world to be fully vaccinated as soon as possible. Although not 100% effective, current vaccines provide considerable protection against the dominant viral strains that are currently circulating. Meanwhile, more testing data are needed to evaluate the effectiveness of current vaccines on Delta and other variants, and public health authorities should inform the public by making these data available (Dai et al. 2020). Thirdly, the research, development, and production of new COVID-19 vaccines should accelerate to increase preparedness for new SARS-CoV-2 variants and their possible long existence and recurring outbreaks in our communities and animal reservoirs, much like the influenza viruses (He et al. 2021; He and Han 2021b). Last but not the least, researchers should investigate whether the transmission routes of new SARS-CoV-2 variants have indeed changed and particularly, whether there are existing or new environmental transmission routes that have been overlooked or underappreciated in previous dealing with the SARS-CoV-2 (Chen et al. 2021; Han et al. 2021; Han and Zhang 2020; Propper 2020; Wang et al. 2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Young Talent Program of Xi’an Jiaotong University.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest in this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Akter S, Zakia MA, Mofijur M, Ahmed SF, Ahmed SF, Vo D-VN, Khandaker G, Mahlia TMI. SARS-CoV-2 variants and environmental effects of lockdowns, masks and vaccination: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;26:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01323-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernal JL, Andrews N, Gower C, Gallagher E, Simmons R, Thelwall S, Stowe J, Tessier E, Groves N, Dabrera G, Myers R, Campbell CNJ, Amirthalingam G, Edmunds M, Zambon M, Brown KE, Hopkins S, Chand M, Ramsay M (2021) Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines against the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant. New Engl J Med 385(7):585–594. 10.1056/NEJMoa2108891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bjorkman KK, Saldi TK, Lasda E, Bauer LC, Kovarik J, Gonzales PK, Fink MR, Tat KL, Hager CR, Davis JC, Ozeroff CD, Brisson GR, Larremore DB, Leinwand LA, McQueen MB, Parker R (2021) Higher viral load drives infrequent severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 transmission between asymptomatic residence hall roommates. J Infect 224(18):1316–1324. 10.1093/infdis/jiab386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Boao Forum for Asia (BFA) (2021) Report on the global picture of COVID-19 vaccine use. https://www.boaoforum.org/newsdetial.html?itemId=0&navID=1&itemChildId=undefined&detialId=13757&pdfPid=482. Accessed 30 November 2021.

- Buonerba A, Corpuz MVA, Ballesteros F, Choo K-H, Hasan SW, Korshin GV, Belgiorno V, Barceló D, Naddeo V. Coronavirus in water media: analysis, fate, disinfection and epidemiological applications. J Hazard Mater. 2021;415:125580. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaway E. Heavily mutated Omicron variant puts scientists on alert. Nature. 2021;600:21. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-03552-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappa CD, Asadi S, Barreda S, Wexler AS, Bouvier NM, Ristenpart WD. Expiratory aerosol particle escape from surgical masks due to imperfect sealing. Sci Rep. 2021;11:12110. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-91487-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2021a) Variant proportions. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2021b) Global variants report. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#global-variant-report-map. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2021c) Guidance and tips for tribal community living during COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/tribal/social-distancing.html. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2021d) Scientific brief: SARS-CoV-2 transmission. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/sars-cov-2-transmission.html. Accessed 30 November 2021 [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2021e) SARS-CoV-2 variant classifications and definitions. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-info.html. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Chen B, Jia P, Han J. Role of indoor aerosols for COVID-19 viral transmission: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:1953–1970. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01174-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- China Central Television net (CCTV) (2021) Asia Today 20210625. https://tv.cctv.com/2021/06/26/VIDEkI4XrEO2s7gkh8jeNHoJ210626.shtml?spm=C45305.PnMHVdsoUDRF.ErEcBmid45Gx.111. Accessed 30 November 2021

- China National Biotec Group (CNBG) (2020) Sinopharm Group China National Biotec Group COVID-19 inactivated vaccine approved and listed conditionally. https://www.cnbg.com.cn/content/details_12_5965.html. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Choi H, Chatterjee P, Hwang M, Lichtfouse E, Sharma VK, Jinadatha C. The viral phoenix: enhanced infectivity and immunity evasion of SARS-CoV-2 variants. Environ Chem Lett. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01318-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Chatterjee P, Coppin JD, Martel JA, Hwang M, Jinadatha C, Sharma VK. Current understanding of the surface contamination and contact transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in healthcare settings. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:1935–1944. doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01186-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H, Chatterjee P, Lichtfouse E, Martel JA, Hwang M, Jinadatha C, Sharma VK. Classical and alternative disinfection strategies to control the COVID-19 virus in healthcare facilities: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:1945–1951. doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01180-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choudhury SR (2021) Delta variant is still the ‘major cause of the pandemic’ despite worries about omicron, WHO says. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/11/29/who-says-delta-covid-variant-still-the-priority-despite-omicron-worries.html. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Cowling BJ, Zhou Y, Ip DKM, Leung GM, Aiello AE. Face masks to prevent transmission of influenza virus: a systematic review. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138(4):449–456. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809991658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, Han J, Lichtfouse E. Who is running faster, the virus or the vaccine? Environ Chem Lett. 2020;18:1761–1766. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01110-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai H, Han J, Lichtfouse E. Smarter cures to combat COVID-19 and future pathogens: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:2759–2771. doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01224-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy S. Why are RNA virus mutation rates so damn high? PLoS Biol. 2018;16:e3000003. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) (2021) Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617 variants in India and situation in the EU/EEA. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/threat-assessment-emergence-sars-cov-2-b1617-variants#no-link. Accessed 30 November 2021.

- Falsey AR, Sobieszczyk ME, Hirsch I, Sproule S, Robb ML, Corey L, Neuzil KM, Hahn W, Hunt J, Mulligan MJ, McEvoy C, DeJesus E, Hassman M, Little SJ, Pahud BA, Durbin A, Pickrell P, Daar ES, Bush L, Solis J, Carr QO, Oyedele T, Buchbinder S, Cowden J, Vargas SL, Benavides AG, Call R, Keefer MC, Kirkpatrick BD, Pullman J, Tong T, Isaacs MB, Benkeser D, Janes HE, Nason MC, Green JA, Kelly EJ, Maaske J, Mueller N, Shoemaker K, Takas T, Marshall RP, Pangalos MN, Villafana T, Gonzalez-Lopez A. Phase 3 safety and efficacy of AZD1222 (ChAdOx1 nCoV-19) Covid-19 vaccine. New Engl J Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2105290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fears AC, Klimstra WB, Duprex P, Hartman A, Weaver S, Plante K, Mirchandani D, Plante JA, Aguilar P, Fernández D, Nalca A, Totura A, Dyer D, Kearney B, Lackemeyer M, Bohannon JK, Johnson R, Garry R, Reed D, Roy C. Persistence of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 in aerosol suspensions. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(9):2168–2171. doi: 10.3201/eid2609.201806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) (2021) Tracking of variants. https://www.gisaid.org/hcov19-variants/. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Grant R, Charmet T, Schaeffer L, Galmiche S, Madec Y, Von Platen C, Chény O, Omar F, David C, Rogoff A, Paireau J, Cauchemez S, Carrat F, Septfons A, Levy-Bruhl D, Mailles A, Fontanet A (2021) Impact of SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant on incubation, transmission settings and vaccine effectiveness: results from a nationwide case-control study in France. Lancet Reg Health Eur 100278. 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gu J, Han B, Wang J. COVID-19: Gastrointestinal manifestations and potential fecal-oral transmission. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):1518–1519. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, He S. Urban flooding events pose risks of virus spread during the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. Sci Total Environ. 2021;755(1):142491. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Zhang Y. Microfiber pillow as a potential harbor and environmental medium transmitting respiratory pathogens during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ecotoxicol Environ Safety. 2020;205:111177. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Zhang X, He S, Jia P. Can the coronavirus disease be transmitted from food? A review of evidence, risks, policies and knowledge gaps. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:5–16. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01101-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Han J. Electrostatic fine particles emitted from laser printers as potential vectors for airborne transmission of COVID-19. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:17–24. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01069-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Han J. Biorepositories (biobanks) of human body fluids and materials as archives for tracing early infections of COVID-19. Environ Pollut. 2021;274:116525. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X, Reponen T, McKay RT, Grinshpun SA. Effect of particle size on the performance of an N95 Filtering facepiece respirator and a surgical mask at various breathing conditions. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2013;47(11):1180–1187. doi: 10.1080/02786826.2013.829209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He S, Han J, Lichtfouse E. Backward transmission of COVID-19 from humans to animals may propagate reinfections and induce vaccine failure. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:763–768. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01140-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong HW, Kim SM, Kim HS, Kim YI, Kim JH, Cho JY, Kim SH, Kang H, Kim SG, Park SJ, Kim EH, Choi YK. Viable SARS-CoV-2 in various specimens from COVID-19 patients. Clin Microbiol Infec. 2020;26(11):1520–1524. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura I, Kosugi Y, Wu J, Yamasoba D, Butlertanaka EP, Tanaka YL, Liu Y, Shirakawa K, Kazuma Y, Nomura R, Horisawa Y, Tokunaga K, Takaori-Kondo A, Arase H, Genotype T, to Phenotype Japan C. Saito A, Nakagawa S, Sato K. SARS-CoV-2 Lambda variant exhibits higher infectivity and immune resistance. BioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.07.28.454085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Deng A, Li K, Hu Y, Li Z, Xiong Q, Liu Z, Guo Q, Zou L, Zhang H, Zhang M, Ouyang F, Su J, Su W, Xu J, Lin H, Sun J, Peng J, Jiang H, Zhou P, Hu T, Luo M, Zhang Y, Zheng H, Xiao J, Liu T, Che R, Zeng H, Zheng Z, Huang Y, Yu J, Yi L, Wu J, Chen J, Zhong H, Deng X, Kang M, Pybus OG, Hall M, Lythgoe KA, Li Y, Yuan J, He J, Lu J. Viral infection and transmission in a large, well-traced outbreak caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant. MedRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.07.07.21260122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Huang Y, Wang W, Li X, Huang Y, Wang W, Jing Q, Zhang C, Qin P, Guan W, Gan L, Li Y, Liu W, Dong H, Miao Y, Fan S, Zhang Z, Zhang D, Zhong N. Effectiveness of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines against the Delta variant infection in Guangzhou: a test-negative case–control real-world study. Emerg Microbes Infec. 2021;10(1):1751–1759. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2021.1969291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Wei P, Zhang Q, Aviszus K, Linderberger J, Yang J, Liu J, Chen Z, Waheed H, Reynoso L, Downey GP, Frankel SK, Kappler J, Marrack P, Zhang G. The Lambda variant of SARS-CoV-2 has a better chance than the Delta variant to escape vaccines. BioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.08.25.457692. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Ginn HM, Dejnirattisai W, Supasa P, Wang B, Tuekprakhon A, Nutalai R, Zhou D, Mentzer AJ, Zhao Y, Duyvesteyn HME, López-Camacho C, Slon-Campos J, Walter TS, Skelly D, Johnson SA, Ritter TG, Mason C, Costa Clemens SA, Gomes Naveca F, Nascimento V, Nascimento F, Fernandes da Costa C, Resende PC, Pauvolid-Correa A, Siqueira MM, Dold C, Temperton N, Dong T, Pollard AJ, Knight JC, Crook D, Lambe T, Clutterbuck E, Bibi S, Flaxman A, Bittaye M, Belij-Rammerstorfer S, Gilbert SC, Malik T, Carroll MW, Klenerman P, Barnes E, Dunachie SJ, Baillie V, Serafin N, Ditse Z, Da Silva K, Paterson NG, Williams MA, Hall DR, Madhi S, Nunes MC, Goulder P, Fry EE, Mongkolsapaya J, Ren J, Stuart DI, Screaton GR (2021a) Reduced neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 B.1.617 by vaccine and convalescent serum. Cell 184(16): 4220–4236. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.06.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lustig Y, Zuckerman N, Nemet I, Atari N, Mandelboim M (2021) Neutralising capacity against Delta (B.1.617.2) and other variants of concern following Comirnaty (BNT162b2, BioNTech/Pfizer) vaccination in health care workers, Israel. Eurosurveillance 26(26): 2100557. doi:10.2807/15607917.ES.2021.26.26.2100557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Morales AC, Rice AM, Ho AT, Mordstein C, Mühlhausen S, Watson S, Cano L, Young B, Kudla G, Hurst LD (2021) Causes and consequences of purifying selection on SARS-CoV-2. Genome Biol Evol 13(10): evab196. 10.1093/gbe/evab196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Morawska L, Milton DK. It is time to address airborne transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71(9):2311–2313. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pango Network (PN) (2021) New AY lineages. https://www.pango.network/new-ay-lineages/. Accessed 30 November 2021

- New York Times (NYT) (2021) Biden calls Omicron a ‘cause for concern, not a cause for panic.’ https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/29/us/politics/biden-vaccines-omicron.html. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Newsweek (2021) Delta Sub-Variant AY.4.2 continues to spread as child israel's first case. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/delta-sub-variant-ay-4-2-continues-to-spread-as-child-israel-s-first-case/ar-AAPKFkl. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Nextstrain (2021) Genomic epidemiology of novel coronavirus–Global subsampling. https://nextstrain.org/ncov/gisaid/global. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Olusola-Makinde OO, Reuben RC. Ticking bomb: Prolonged faecal shedding of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) and environmental implications. Environ Pollut. 2020;267:115485. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.115485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfizer (2020) Pfizer and BioNTech Announce Publication of Results from Landmark Phase 3 Trial of BNT162b2 COVID-19 Vaccine Candidate in The New England Journal of Medicine. https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-and-biontech-announce-publication-results-landmark. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Planas D, Veyer D, Baidaliuk A, Staropoli I, Guivel-Benhassine F, Rajah MM, Planchais C, Porrot F, Robillard N, Puech J, Prot M, Gallais F, Gantner P, Velay A, Le Guen J, Kassis-Chikhani N, Edriss D, Belec L, Seve A, Courtellemont L, Péré H, Hocqueloux L, Fafi-Kremer S, Prazuck T, Mouquet H, Bruel T, Simon-Lorière E, Rey FA, Schwartz O. Reduced sensitivity of SARS-CoV-2 variant Delta to antibody neutralization. Nature. 2021;596:276–280. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03777-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pouwels KB, Pritchard E, Matthews PC, Stoesser N, Eyre DW, Vihta K-D, House T, Hay J, Bell JI, Newton JN, Farrar J, Crook D, Cook D, Rourke E, Studley R, Peto TEA, Diamond I, Walker AS. Effect of Delta variant on viral burden and vaccine effectiveness against new SARS-CoV-2 infections in the UK. Nat Med. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01548-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Propper RE. Is sweat a possible route of transmission of SARS-CoV-2? Exp Biol Med. 2020;245(12):997–998. doi: 10.1177/1535370220935409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosti ME, Olivieri S, Cavaiola M, Seminara A, Mazzino A. Fluid dynamics of COVID-19 airborne infection suggests urgent data for a scientific design of social distancing. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):22426. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-80078-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sala-Comorera L, Reynolds LJ, Martin NA, O'Sullivan JJ, Meijer WG, Fletcher NF. Decay of infectious SARS-CoV-2 and surrogates in aquatic environments. Water Res. 2021;201:117090. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies (SAGE) (2021) Research and analysis: Long term evolution of SARS-CoV-2, 26 July 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/long-term-evolution-of-sars-cov-2-26-july-2021. Accessed 25 October 2021

- Scudellari M. How the coronavirus infects cells–and why Delta is so dangerous. Nature. 2021;595(7869):640–644. doi: 10.1038/d41586-021-02039-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma VK, Jinadatha C, Lichtfouse E, Decroly E, van Helden J, Choi H, Chatterjee P. COVID-19 epidemiologic surveillance using wastewater. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:1911–1915. doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01188-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Kumar V, Kapoor D, Dhanjal DS, Singh J. Detection and disinfection of COVID-19 virus in wastewater. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:1917–1933. doi: 10.1007/s10311-021-01202-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinovac Biotech Ltd (SINOVAC) (2020) Beijing Sinovac Biotech Ltd. COVID-19 inactivated vaccine CoronaVac® Phase III Clinical study data released. http://www.sinovac.com/news/shownews.php?id=426. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (2021f) CDC Statement on B.1.1.529 (Omicron variant). https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2021/s1126-B11-529-omicron.html. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Sun S, Han J. Unflushable or missing toilet paper, the dilemma for developing communities during the COVID-19 episode. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:711–717. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01064-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Han J. Open defecation and squat toilets, an overlooked risk of fecal transmission of COVID-19 and other pathogens in developing communities. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:787–795. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01143-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Li J, Han J. How human thermal plume influences near-human transport of respiratory droplets and airborne particles: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19:1971–1982. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01178-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartof SY, Slezak JM, Fischer H, Hong V, Ackerson BK, Ranasinghe ON, Frankland TB, Ogun OA, Zamparo JM, Gray S, Valluri SR, Pan K, Angulo FJ, Jodar L, McLaughlin JM. Effectiveness of mRNA BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccine up to 6 months in a large integrated health system in the USA: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2021;398(10309):1407–1416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02183-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tencent news (TN) (2021a) Israel is close to universal immunity. https://new.qq.com/omn/20210325/20210325A0055R00.html. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Tencent news (TN) (2021b) Israel has seen a sudden reversal of the epidemic, with a surge in confirmed cases and severe cases, for reasons that remain unclear. https://new.qq.com/omn/20210818/20210818A0DEEQ00.html. Accessed 30 November 2021.

- Tencent news (TN) (2021c) US cut off an 8country flight, Australia or urgent call for stopover students to return! https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20211129A0C7EC00. Accessed 30 November 2021.

- The Health Site (THS) (2021) Delhi hospital reports fourfold upsurge in long covid cases after second wave. https://www.thehealthsite.com/news/delhi-hospital-reports-fourfold-upsurge-in-long-covid-cases-after-second-wave-826214/. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Thiruvengadam R, Awasthi A, Medigeshi G, Bhattacharya S, Mani S, Sivasubbu S, Shrivastava T, Samal S, Rathna Murugesan D, Koundinya Desiraju B, Kshetrapal P, Pandey R, Scaria V, Kumar Malik P, Taneja J, Binayke A, Vohra T, Zaheer A, Rathore D, Ahmad Khan N, Shaman H, Ahmed S, Kumar R, Deshpande S, Subramani C, Wadhwa N, Gupta N, Pandey AK, Bhattacharya J, Agrawal A, Vrati S, Bhatnagar S, Garg PK (2021) Effectiveness of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection during the delta (B.1.617.2) variant surge in India: a test-negative, case-control study and a mechanistic study of post-vaccination immune responses. Lancet Infect Dis. 10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00680-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ueki H, Furusawa Y, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Imai M, Kabata H, Nishimura H, Kawaoka Y, Imperiale MJ (2020) Effectiveness of Face Masks in Preventing Airborne Transmission of SARS-CoV-2. mSphere 5(5): e00637–20. 10.1128/mSphere.00637-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Morris DH, Holbrook MG, Gamble A, Williamson BN, Tamin A, Harcourt JL, Thornburg NJ, Gerber SI, Lloyd-Smith JO, de Wit E, Munster VJ. Aerosol and surface stability of SARS-CoV-2 as compared with SARS-CoV-1. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(16):1564–1567. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2004973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Han J, Lichtfouse E. Unprotected mothers and infants breastfeeding in public amenities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Environ Chem Lett. 2020;18:1447–1450. doi: 10.1007/s10311-020-01054-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2020b) Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): How is it transmitted? https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-how-is-it-transmitted. Accessed 30 November 2021

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2021d) Classification of Omicron (B.1.1.529): SARS-CoV-2 Variant of Concern. https://www.who.int/news/item/26-11-2021-classification-of-omicron-(b.1.1.529)-sars-cov-2-variant-of-concern. Accessed 30 November 2021

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2020a) Water, sanitation, hygiene, and waste management for the COVID-19 virus. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance-publications. Accessed 30 November 2021

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2021a) WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed 30 November 2021

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2021b) Advice for the public: Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public. Accessed 30 November 2021

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2021c) Global: Israel. https://covid19.who.int/region/euro/country/il. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Wu A, Wang L, Zhou H-Y, Ji C-Y, Xia SZ, Cao Y, Meng J, Ding X, Gold S, Jiang T, Cheng G. One year of SARS-CoV-2 evolution. Cell Host Microbe. 2021;29(4):50–507. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2021.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao F, Sun J, Xu Y, Li F, Huang X, Li H, Zhao J. Infectious SARS-CoV-2 in feces of patient with severe COVID-19. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(8):1920–1922. doi: 10.3201/eid2608.200681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xinhua international (XH) (2021) The epidemic prevention and control situation has improved significantly, and Israel has lifted a ban on face masks. http://static.cms.xinhua-news.cn/c/2021-06-16/4511208.shtml. Accessed 30 November 2021

- Yadav PD, Sapkal GN, Abraham P, Ella R, Deshpande G, Patil DY, Nyayanit DA, Gupta N, Sahay RR, Shete AM, Panda S, Bhargava B, Mohan VK (2021a) Neutralization of variant under investigation B.1.617 with sera of BBV152 vaccinees. Clin Infect Dis ciab411. 10.1093/cid/ciab411 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yadav PD, Sahay RR, Sapkal G, Nyayanit D, Shete AM, Deshpande G, Patil DY, Gupta N, Kumar S, Abraham P, Panda S, Bhargava B (2021b) Comparable neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 Delta AY.1 and Delta with individuals sera vaccinated with BBV152. J Travel Med taab154. 10.1093/jtm/taab154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Young SG, Kitchen A, Kayali G, Carrel M. Unlocking pandemic potential: prevalence and spatial patterns of key substitutions in avian influenza H5N1 in Egyptian isolates. Bmc Infect Dis. 2018;18(1):314. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3222-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Xiao J, Deng A, Zhang Y, Zhuang Y, Hu T, Li J, Tu H, Li B, Zhou Y, Yuan J, Luo L, Liang Z, Huang Y, Ye G, Cai M, Li G, Yang B, Xu B, Huang X, Cui Y, Ren D, Zhang Y, Kang M, Li Y (2021) Transmission dynamics of an outbreak of the COVID-19 Delta variant B.1.617.2–Guangdong province, China, May–June 2021. China CDC Weekly 3(27): 584–586. 10.46234/ccdcw2021.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zvulun R (2021) Scientists seek clues that COVID-vaccine rollouts are working. Nature 589: 504–505. https://media.nature.com/original/magazine-assets/d41586-021-00140-w/d41586-021-00140-w.pdf