Abstract

Strain differentiation of Mycobacterium leprae would be of great value for epidemiological investigation to identify the infectious sources of leprosy, to understand transmission patterns, and to distinguish between relapse and reinfection. From the M. leprae genome sequence database, TTC DNA repeats were identified. Primer sets designed to amplify the region flanking TTC repeats revealed PCR products of different sizes, indicating that the number of repeats at each locus may be variable among M. leprae strains. The TTC repeats were not found in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium marinum, or human tissues, which indicated their specificity to M. leprae. Sequence analysis of the TTC repeat region in each of the M. leprae strains showed a variation of 10 to 37 repeats. In the M. leprae strains of 34 multibacillary patients at Cebu, Philippines, M. leprae with 24 and 25 TTC repeats was most common, and this was followed by strains with 14, 15, 20, 21, and 28 repeats. This study thus indicates that there are variable numbers of TTC repeats in a noncoding region of M. leprae strains and that the TTC region may be useful for strain differentiation for epidemiological investigations of leprosy.

Despite a rapid reduction in the number of registered cases over the last 15 years, leprosy is still a major public health problem in several countries (23). Even after the World Health Organization's (WHO's) efforts to eliminate leprosy as a public health problem by the year 2000, there remain hyperendemic areas in many countries which have shown no substantial decrease in the new case detection rate (23). In such areas, strain typing methods for Mycobacterium leprae would be of great value to identify the source of infection and to understand the transmission patterns of the organisms. In addition, strain differentiation methods for M. leprae isolates would be very useful in distinguishing relapse from reinfection after the completion of chemotherapy.

Several attempts have been made to identify polymorphic DNA sequences which could be used for M. leprae strain differentiation. However, restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis using various probes has not shown any differences between M. leprae isolates (4, 5, 16, 21). The single-strand conformation polymorphism patterns and DNA sequences of the region between 16S and 23S rRNA were also identical in M. leprae from different multibacillary (MB) leprosy patients (7). Although there are at least 28 dispersed repeats in the M. leprae genome (22), there are no reports on polymorphism based on the repeat. A recent report on a new class of M. leprae-specific repetitive sequence, RLEP, suggested another possibility for differentiating between M. leprae isolates, because PCR amplification of this repeat showed different intensities and the absence of the RLEP sequence in the pol(A) gene of certain M. leprae isolates (11). However, molecular typing based on this approach has not been fully explored in an effort to differentiate M. leprae isolates from different leprosy patients.

In the case of tuberculosis, RFLP analysis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis based on insertion sequences such as IS6110 has been widely employed to understand organism transmission patterns and identify epidemics of highly virulent strains and multidrug-resistant M. tuberculosis strains (6, 18). However, RFLP analysis based on the Southern blot technique is not practical in M. leprae, mainly because of the difficulty of obtaining sufficient DNA to run RFLP since M. leprae cannot be cultured in vitro. PCR-based molecular typing of M. leprae targeting variable numbers of tandem repeats may thus be a more practical option in terms of applicability in clinical laboratories. In an effort to identify such variable numbers of DNA repeats in the M. leprae genome sequences available in the Mycobacterium DataBase, we focused on a TTC repeat in a noncoding region in the cosmid MLCB2407 (GenBank accession no. AL023596). In this study, we report evidence of variable numbers of this TTC repeat in M. leprae strains from MB leprosy patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Biopsy samples.

Biopsy samples were obtained from leprosy patients who visited the Skin Clinic at the Leonard Wood Memorial Center, Cebu, Philippines, before and 1 year after starting WHO multidrug therapy. As described previously (25), frozen 5-μm sections were prepared from each biopsy sample and stored at −20°C until used for PCR. Bacterial indices were determined both for biopsy samples and for slit-skin smears by microscopic examination.

For controls, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) purified from five blood donors and a skin biopsy sample from a patient with secondary syphilis were included in this study. M. tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellulare, Mycobacterium smegmatis, Mycobacterium phlei, and Mycobacterium marinum, which had been maintained in the laboratory, were also included to examine the specificity of PCR.

Preparation of M. leprae DNA from biopsy specimens.

M. leprae DNA was prepared from frozen biopsy sections as described previously (25). Briefly, about six frozen sections were disrupted vigorously in a microcentrifuge tube containing 100 μl of 0.1-mm zirconium beads in Tris-EDTA-NaCl (pH 8.0) and 50 μl of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) using a bead beater (Biospecs Products, Bartlesville, Okla.) for 1 min. After centrifugation for 5 min, the aqueous phase was collected and mixed with an equal volume of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1). After another brief centrifugation, the upper phase was collected and boiled for 10 min to destroy DNase. DNA was then precipitated with ethanol and resuspended in 10 μl of distilled water before being used for PCR.

DNA from PBMC and other mycobacterial species was prepared by freezing in liquid nitrogen and boiling five times.

PCR amplification of TTC repeats.

A 21-TTC repeat locus was identified in a noncoding sequence of the cosmid B2407 (GenBank accession no. AL023596), and a pair of primers was designed to amplify 201 bp flanking the entire 21 TTC repeats. The primer sequences were 5′-GGACCTAAACCATCCCGTTT-3′ (TTC-A) and 5′-CTACAGGGGGCACTTAGCTC-3′ (TTC-B). The PCR mixture (50 μl) consisted of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 ml of MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphate mix, 1 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Biosystems, San Francisco, Calif.), 10 pmol of each primer, and DNA prepared from biopsy samples. After denaturing DNA at 94°C for 5 min, PCR was carried out for 35 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 58°C for 30 s, and extension at 72°C for 30 s, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min in a thermocycler (model 9600; Perkin-Elmer Co., Norwalk, Conn.). A 10-μl sample of each reaction mixture was run on a 3% agarose gel.

PCR amplification of the β-actin gene in PBMC was performed as described by Choi et al. (3).

Autoradiographic analysis of PCR products.

The PCR mix (25 μl) consisted of 0.2 mM dATP, dGTP, and dCTP, 2 μM dTTP, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 pmol of each primer, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 0.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase, and 0.5 μCi of [α-32P]dTTP (3,000 μCi/mmol; NEN, Boston, Mass.). PCR was carried out for 30 cycles at the same conditions as above. Three microliters of PCR product was mixed with 3 μl of loading solution consisting of 95% formamide, 10 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 0.05% bromophenol blue, and 0.05% xylene cyanol. The mixture was then denatured at 94°C for 3 min and loaded on 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gels with 7 M urea. Electrophoresis was carried out at room temperature for 4 to 6 h at a constant power of 50 mA. Autoradiography was performed for 12 to 24 h without an intensifying screen.

Cloning and sequencing of PCR products.

PCR products from MB leprosy patients were purified using the GeneClean III kit (BIO 101, Vista, Calif.) and cloned into a PCR-TOPO vector in the TOPO TA cloning kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). The TOPO vectors containing PCR products were used for transformation of TOP10 competent cells (Invitrogen). Plasmids containing inserts were purified from broth cultures with the Qiagen plasmid kit (Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, Calif.) and sequenced with the AutoRead sequencing kit and ALF DNA sequencer (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

Nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper appear in the GenBank nucleotide sequence database under the accession numbers listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Number and frequency of TTC repeats in M. leprae strains from MB patients

| No. of repeats | Frequency (no. of patients)a | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1 | AF274483 |

| 13 | 1 | AF274484 |

| 14 | 3 | AF274485 |

| 15 | 3 | AF274486 |

| 19 | 2 | AF287975 |

| 20 | 3 | AF274487 |

| 21 | 3 | AF274488 |

| 22 | 1 | AF287976 |

| 23 | 2 | AF274489 |

| 24 | 4 | AF287977 |

| 25 | 4 | AF274490 |

| 27 | 2 | AF274491 |

| 28 | 3 | AF274492 |

| 32 | 1 | AF274493 |

| 37 | 1 | AF274494 |

n = 34.

RESULTS

PCR of TTC repeats.

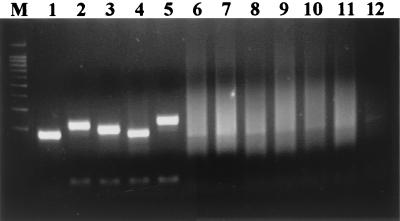

A pair of primers was designed to amplify the 201-bp region flanking the 21 TTC repeats in the cosmid B2407 (GenBank accession no. AL023596) of the M. leprae genome. In order to examine the specificity of the primer set, biopsy sections from leprosy patients and other mycobacterial species were used in PCR. When the PCR products were analyzed in the 3% agarose gel, only PCR products from MB leprosy patients gave a strong band in the 200-bp range (Fig. 1). On the other hand, biopsy samples from paucibacillary leprosy patients and DNA from other mycobacterial species did not show PCR amplification of DNA in this region. These results indicate that the primer set designed to amplify the DNA region flanking the 21 TTC repeats is specific to M. leprae. Interestingly, there were minor size differences in the PCR-amplified DNA from MB leprosy patients, suggesting a polymorphism in the PCR target DNA region.

FIG. 1.

PCR amplification of TTC repeats of M. leprae in biopsy samples from leprosy patients. Lanes 1 to 5, biopsies from MB patients; lanes 6 to 8, biopsies from PB patients; lane 9, M. avium; lane 10, M. smegmatis; lane 11, M. phlei; lane 12, healthy human PBMC; lane M, 100-bp size marker.

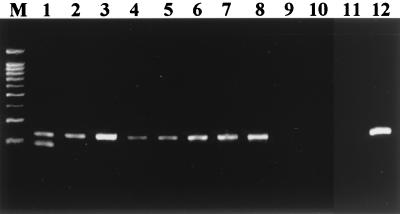

Since human chromosomal DNA contains TTC repeats, there is a possibility of DNA amplification with the primers used in this study. To rule out this possibility, PBMC from blood donors were used in the PCR amplification, with primers for the M. leprae TTC repeat region and primers for β-actin used as the control. As shown in Fig. 2, no PCR products were produced by these primers which corresponded to the M. leprae TTC repeat region, despite β-actin amplification in all cells of human origin. This result thus reconfirmed that primers designed to amplify the M. leprae TTC repeat region amplified specifically DNA of M. leprae.

FIG. 2.

PCR amplification of β-actin in biopsy samples from leprosy patients. Lane 1, multiplex PCR of TTC repeats and β-actin from the biopsy of an MB patient; lanes 2 to 5, biopsies from MB patients; lanes 6 to 8, biopsies from PB patients; lane 9, M. avium; lane 10, M. smegmatis; lane 11, M. phlei; lane 12, healthy human PBMC; lane M, 100-bp size marker.

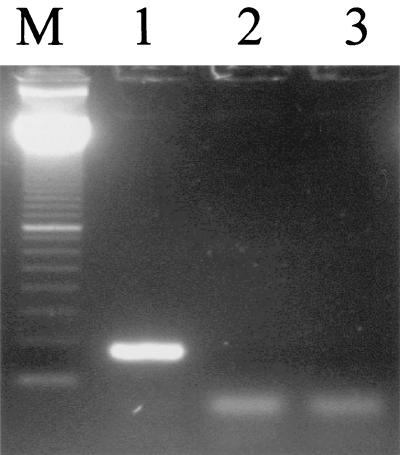

M. marinum is known to cause a granulomatous skin disease. In order to rule out M. marinum in granulomatous lesions in the skin, DNA from the organism was used in PCR for amplification of the M. leprae TTC repeat region. As shown in Fig. 3, there was no amplification of the TTC repeat region. This indicated that there is no M. leprae TTC repeat region in M. marinum. In addition, there was no amplification of M. leprae TTC repeats in a biopsy sample from a syphilis patient. This result also reconfirmed that there would be little chance of amplification of the M. leprae TTC repeat region in skin lesions from patients with nonleprosy skin diseases.

FIG. 3.

PCR amplification of TTC repeat region of M. leprae in M. marinum and biopsy sample from a patient with syphilis. Lane 1, biopsy from an MB leprosy patient; lane 2, M. marinum; lane 3, biopsy from a syphilis patient; lane M, 100-bp size marker.

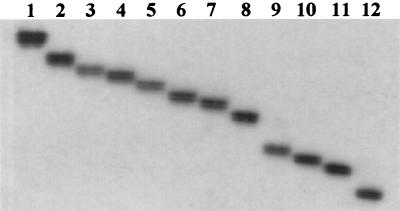

Autoradiographic analysis of PCR products.

As suggested in Fig. 1, there might be minor differences in the sizes of the PCR-amplified products of M. leprae strains. In order to improve resolution and better visualize these differences, PCR was carried out using a PCR mix containing [α-32P]dTTP, and PCR products were then denatured and run in a 6% polyacrylamide gel, followed by autoradiography. As shown in Fig. 4, there were marked differences in the size of PCR products between M. leprae strains from MB leprosy patients, which suggested that the target TTC repeat region may be a polymorphic locus of the M. leprae genome. In addition, a stepwise difference in size between the PCR products also suggested a difference in the number of TTC repeats between the M. leprae strains rather than random polymorphism in DNA sequences.

FIG. 4.

Autoradiography of electrophoresis patterns of PCR products labeled with radioisotope of a flanking region of TTC repeats of M. leprae from leprosy patients. Lane 1, 37 copies of TTC repeats; lane 2, 32 copies; lane 3, 28 copies; lane 4, 27 copies; lane 5, 25 copies; lane 6, 23 copies; lane 7, 21 copies; lane 8, 20 copies; lane 9, 15 copies; lane 10, 14 copies; lane 11, 13 copies; lane 12, 10 copies.

Sequencing of the TTC repeat region of M. leprae strains.

In order to determine the DNA sequences of the TTC repeat region of each M. leprae strain, PCR products were cloned and sequenced using an automatic sequence analyzer. As expected from the autoradiographic analysis, the number of TTC repeats varied among the M. leprae strains, ranging from 10 to 37 repeats (Table 1). The nucleotide sequence data of M. leprae strains containing different numbers of TTC repeats were registered at GenBank, and accession numbers are listed in Table 1. Of 34 MB leprosy patients, there were 15 M. leprae strains with different numbers of TTC repeats; M. leprae strains with 24 and 25 TTC repeats were most frequent and were found in four patients, and these were followed by strains with 14, 15, 20, 21, and 28 TTC repeats.

Reproducibility of PCR and sequence analysis of TTC repeats.

Since there were only small differences in the size of the PCR products of the TTC repeats, there may be technical problems in strain differentiation targeting the TTC repeat region. In order to examine the reproducibility of PCR and sequence analysis, biopsy specimens obtained from different sites at different times from four MB patients during chemotherapy were blindly analyzed by PCR, autoradiography, and sequencing after cloning the PCR products from the M. leprae strains. In all four pairs, the same number of TTC repeats was found in duplicate samples from each patient examined, indicating that PCR and sequencing of the PCR products were reproducible (data not shown). In addition, this implies that the TTC repeat seems stable during multiplication of M. leprae from infection to overt disease, which usually takes several years. These results thus indicate that the TTC repeats might be useful for the strain differentiation of M. leprae.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates clear evidence of sequence polymorphism in the TTC repeat region in M. leprae strains from leprosy patients. Such a variable number of short DNA repeats, known as a variable number of tandem repeats (VNTR), have been widely used for the molecular typing of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells (8, 10, 12, 13, 17, 19). For example, VNTR typing based on three, five, or six nucleotide repeats was useful in the epidemiological investigation of an outbreak by amoxacillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae type b (17). Likewise, three nucleotide repeats, CAA/CAG, have been employed in the typing of Candida albicans strains (2). In addition, such short DNA repeats, also known as microsatellites, have been widely used in forensic investigation (15) and for determining the genetic traits of domestic and pet animals, including horses (1), pigs (26), chickens (14), and dogs (9).

Since TTC repeats are present in human chromosomes (24), PCR amplification of TTC repeats from normal human tissues had to be ruled out in this study. Firstly, both primers were designed based on the M. leprae genome sequences flanking the TTC repeats instead of TTC repeats themselves to make sure that only M. leprae genomic DNA would anneal with the primers. Secondly, specificity was verified by the lack of amplification of TTC repeats from the biopsy samples from paucibacillary leprosy patients, who usually have few M. leprae in their biopsy samples despite the presence of human tissues. Finally, DNA of PBMC did not give PCR amplification of TTC repeats despite amplification of the β-actin gene as a positive control for human chromosomal DNA. In addition, none of six mycobacterial species, including M. tuberculosis and M. marinum, gave PCR amplification of the TTC repeat region. Therefore, we are satisfied that the PCR products were specific to the TTC repeat region of the M. leprae genome.

Sequence analysis of the PCR products from each M. leprae strain of MB leprosy patients revealed differences only in the TTC repeats, and no differences between strains were shown in the sequence between the TTC repeats and the primers in either direction. This suggested that most of the sequences in M. leprae, even in the noncoding region, are conserved, as has been shown in other studies (4, 5, 16, 21). The exact mechanism of the evolution of M. leprae strains with different numbers of TTC repeats remains to be explained, although a slippage or addition of one codon during replication is the most plausible explanation (20, 24). It is also not known yet how stable TTC repeats in M. leprae are during multiplication of its genome after infection in humans, which usually occurs several years before its clinical manifestations.

In the cosmid B2407, which was derived from M. leprae grown in armadillo, there were 21 TTC repeats. Interestingly, there were three leprosy patients who were infected with M. leprae strains with 21 TTC repeats (Table 1). Although the three patients were from Cebu City, Philippines, it is very hard to believe that there is any epidemiological association between M. leprae strains from patients in this study and those used in the preparation of the cosmid library. If there are other regions containing VNTR, a combination of VNTR including TTC repeats will allow easier strain differentiation of M. leprae. For example, there were at least five VNTR loci in M. tuberculosis (10), and they proved useful in determining evolutionary traits of Mycobacterium bovis and M. bovis BCG strains worldwide.

In previous studies, a polymorphic site in the M. leprae genome was searched for epidemiological investigation, particularly for distinguishing between relapse and reinfection. Using the molecular typing method, it is now almost possible to determine the difference between M. leprae strains. To our knowledge, this is the second piece of evidence which shows polymorphism in M. leprae strains, the first being the RLEP insertion sequences found in the poly(A) gene and described previously (11). However, PCR of the TTC repeats has an advantage over PCR of the RLEP insertion sequence because it can show the size differences of PCR products, whereas RLEP PCR shows intensity differences. It would be of great interest to compare the two polymorphisms using the same specimens.

In summary, the results of this study indicate that there are a variable number of TTC repeats in a noncoding region of the M. leprae strains and that the TTC region is useful for the strain differentiation of M. leprae, which could be used for epidemiological investigation and the PCR-based diagnosis of leprosy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by grants from the Korean Science and Engineering Foundation (981-0701-076-2), Seoul, Korea; the UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR); and the Leonard Wood Memorial (American Leprosy Foundation), Rockville, Md.

We thank clinical and technical staffs at the Leonard Wood Memorial Center in Cebu, Philippines, for their help in the collection and processing of clinical samples. We are also grateful to Tomas P. Gillis of G. W. Long Hansen's Disease Center for his critical discussion of the results.

REFERENCES

- 1.Binns M M, Holmes N G, Holliman A, Scott A M. The identification of polymorphic microsatellite loci in the horse and their use in thoroughbred parentage testing. Br Vet J. 1995;151:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0007-1935(05)80057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bretagne S, Costa J M, Besmond C, Carsique R, Calderone R. Microsatellite polymorphism in the promoter sequence of the elongation factor 3 gene of Candida albicans as the basis for a typing system. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1777–1780. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1777-1780.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choi C H, Park J Y, Lee J, Lim J H, Shin E C, Ahn Y S, Kim C H, Kim S J, Kim J D, Choi I S, Choi I H. Fas ligand and fas are expressed constitutively in human astrocytes and the expression increases with IL-1, IL-6, TNF-α, or IFN-γ. J Immunol. 1999;162:1889–1895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clark-Curtiss J E, Jacobs W R, Jr, Docherty M A, Ritchie L R, Curtiss R., III Molecular analysis of DNA and construction of genomic libraries of Mycobacterium leprae. J Bacteriol. 1985;161:1093–1102. doi: 10.1128/jb.161.3.1093-1102.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark-Curtiss J E, Walsh G P. Conservation of genomic sequences among isolates of Mycobacterium leprae. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:4844–4851. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.9.4844-4851.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daley C L, Small P M, Schecter G F, Schoolnik G K, McAdam R A, Jacobs W R, Jr, Hopewell P C. An outbreak of tuberculosis with accelerated progression among persons infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. An analysis using restriction-fragment-length polymorphisms. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:231–235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201233260404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Wit M Y, Klatser P R. Mycobacterium leprae isolates from different sources have identical sequences of the spacer region between the 16S and 23S ribosomal RNA genes. Microbiology. 1994;140:1983–1987. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-8-1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field D, Wills C. Abundant microsatellite polymorphism in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and the different distributions of microsatellites in eight prokaryotes and S. cerevisiae, result from strong mutation pressures and a variety of selective forces. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1647–1652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Francisco L V, Langston A A, Mellersh C S, Neal G L, Ostrander E A. A class of highly polymorphic tetranucleotide repeats for canine genetic mapping. Mamm Genome. 1996;7:359–362. doi: 10.1007/s003359900104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frothingham R, Meeker-O'Connell W A. Genetic diversity in the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex based on variable numbers of tandem DNA repeats. Microbiology. 1998;144:1189–1196. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-5-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fsihi H, Cole S T. The Mycobacterium leprae genome: systematic sequence analysis identifies key catabolic enzymes, ATP-dependent transport systems and a novel polA locus associated with genomic variability. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:909–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein D B, Clark A G. Microsatellite variation in North American populations of Drosophila melanogaster. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995;23:3882–3886. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.19.3882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groppe K, Sanders I, Wiemken A, Boller T. A microsatellite marker for studying the ecology and diversity of fungal endophytes (Epichloe spp.) in grasses. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3943–3949. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.11.3943-3949.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McConnell S K J, Dawson D A, Wardle A, Burke T. The isolation and mapping of 19 tetranucleotide microsatellite markers in the chicken. Anim Genet. 1999;30:183–189. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2052.1999.00454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pelotti S, Mantovani V, Esposti P D, D'Apote L, Bragliani M, Maiolini E, Abbondanza A, Pappalardo G. The DRPLA CAG repeats in an Italian population sample: evaluation of the polymorphism for forensic applications. J Forensic Sci. 1998;43:410–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sela S, Clark-Curtiss J E, Bercovier H. Characterization and taxonomic implications of the rRNA genes of Mycobacterium leprae. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:70–73. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.70-73.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Belkum A, Melchers W J G, Ijsseldijk C, Nohlmans L, Verbrugh H, Meis J F G M. Outbreak of amoxicillin-resistant Haemophilus influenzae type b: variable number of tandem repeats as novel molecular markers. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1517–1520. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1517-1520.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Embden J D A, Cave M D, Crawford J T, Dale J W, Eisenach K D, Gicquel B, Hermans P, Martin C, McAdam R, Shinnick T M, Small P M. Strain identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by DNA fingerprinting: recommendations for a standardized methodology. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:406–409. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.406-409.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Van Soolingen D, De Haas P E W, Hermans P W M, Groenen P M A, Van Embden J D A. Comparison of various repetitive DNA elements as genetic markers for strain differentiation and epidemiology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1987–1995. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.1987-1995.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wells R D, Parniewski P, Pluciennik A, Bacolla A, Gellibolian R, Jaworski A. Small slipped register genetic instabilities in Escherichia coli in triplet repeat sequences associated with hereditary neurological diseases. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19532–19541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams D L, Gillis T P. A study of the relatedness of Mycobacterium leprae isolates using restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis. Acta Leprol. 1989;7(Suppl. 1):226–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woods S A, Cole S T. A family of dispersed repeats in Mycobacterium leprae. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1745–1751. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization. Action programme for the elimination of leprosy. Status Report. WHO/LEP/98.2. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu M J, Chow L W, Hsieh M. Amplification of GAA/TTC triplet repeat in vitro: preferential expansion of (TTC)n strand. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1407:155–162. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(98)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoon K-H, Cho S-N, Lee M-K, Abalos R M, Cellona R V, Fajardo T T, Jr, Guido L S, dela Cruz E C, Walsh G P, Kim J-D. Evaluation of polymerase chain reaction amplification of Mycobacterium leprae-specific repetitive sequence in biopsy specimens from leprosy patients. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:895–899. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.4.895-899.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao F, Ambady S, Ponce de Leon F A, Miller L M, Kunncy J K, Grimm D R, Schook L B, Louis C F. Microsatellite markers from a microdissected swine chromosome 6 genomic library. Anim Genet. 1999;30:251–255. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2052.1999.00502.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]