Significance

Our study highlights that hemochromatotic hosts are susceptible to the siderophilic enteropathogenic Yersinia because of dysregulated interleukn (IL)-1β signaling that causes rapid disruption of the intestinal tight junction, leading to acute systemic infection. This study also poses early intervention of anti–IL-1β therapy as a potentially novel strategy for treating hemochromatotic patients with severe siderophilic bacterial infections.

Keywords: hemochromatosis, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, siderophore, hyperinflammation, lethal infection

Abstract

Hemachromatosis (iron-overload) increases host susceptibility to siderophilic bacterial infections that cause serious complications, but the underlying mechanisms remain elusive. The present study demonstrates that oral infection with hyperyersiniabactin (Ybt) producing Yersinia pseudotuberculosis Δfur mutant (termed Δfur) results in severe systemic infection and acute mortality to hemochromatotic mice due to rapid disruption of the intestinal barrier. Transcriptome analysis of Δfur-infected intestine revealed up-regulation in cytokine–cytokine receptor interactions, the complement and coagulation cascade, the NF-κB signaling pathway, and chemokine signaling pathways, and down-regulation in cell-adhesion molecules and Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Further studies indicate that dysregulated interleukin (IL)-1β signaling triggered in hemachromatotic mice infected with Δfur damages the intestinal barrier by activation of myosin light-chain kinases (MLCK) and excessive neutrophilia. Inhibiting MLCK activity or depleting neutrophil infiltration reduces barrier disruption, largely ameliorates immunopathology, and substantially rescues hemochromatotic mice from lethal Δfur infection. Moreover, early intervention of IL-1β overproduction can completely rescue hemochromatotic mice from the lethal infection.

Iron is essential for virtually all organisms to perform many cellular processes but must be maintained at extremely low levels (∼10−24 M) to avoid iron toxicity and infection by bacterial pathogens (1, 2). Hemochromatosis due to genetic, dietary, or iatrogenic (hemodialysis, frequent blood transfusion) conditions predisposes individuals to infections by a variety of pathogens (3). Hereditary hemochromatosis (HH) with decreased hepcidin expression due to the HfeC282Y/C284Y mutation is an iron-overload disorder that causes increased intestinal iron absorption and accumulation of excessive iron in the liver, heart, and other organs (4). HH is among the most common genetic disorders in the United States and Caucasians (5). Clinical evidence indicates that individuals with HH, sickle-cell disease, thalassemia, or liver cirrhosis manifesting hemochromatotic disorders are prone to infections by food-borne pathogens, such as Yersinia (6, 7) and Vibrio vulnificus (8, 9), which cause serious complications, even sepsis. However, the underlying mechanisms leading to these clinical and experimental observations remain elusive.

To adapt to iron starvation conditions and obtain iron from mammalian hosts, bacterial pathogens employ a variety of iron uptake mechanisms, including the expression of transferrin/lactoferrin receptors, the use of heme acquisition systems, and the secretion of iron-scavenging siderophores, such as aerobactin, enterobactin (Ent), and yersiniabactin (Ybt) (1, 6, 10). Siderophores are low molecular mass (500 to 1,500 Da) ferric (Fe3+) chelators with higher iron-binding affinities than those of host iron chelators (11). In bacteria, the siderophore synthesis is regulated by the concentration of intracellular Fe2+ and the ferric uptake regulator (Fur) encoded by the fur gene. When the intracellular Fe2+ concentration is high, iron-bound Fur binds the Fur box or FBS (Fur binding sequence), repressing siderophore synthesis. In contrast, when the intracellular Fe2+ concentration is low, iron-unbound Fur dissociates from FBS, increasing siderophore production (12).

The Fur/siderophore-mediated iron regulation system is also used by gram-negative, enteropathogenic Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia enterocolitica (2). They usually cause self-limiting gastroenteritis in healthy humans but can cause severe diseases in immunocompromised individuals (13). A recent study reported that a siderophilic Y. enterocolitica is more lethal to iron overload mice than nonsiderophilic Y. enterocolitica (14). In pathogenic Yersinia spp., the genes encoding Ybt-mediated iron uptake are in the locus of high-pathogenicity islands, and Ybt production is strongly associated with virulence (15). The sporadic Y. pseudotuberculosis O1 strain has a Fur-regulated Ybt cluster identical to that in Yersinia pestis (2). Y. pestis or its fur mutant cultured in low iron medium dramatically increase gene expression associated with Ybt synthesis (16). As a global regulator, numerous fur mutants are attenuated in regular mouse models (12) and exhibit constitutive expression of iron uptake genes and elevated production of siderophores (16). However, whether the Δfur Y. pseudotuberculosis mutant (termed Δfur) with presumed high Ybt production display a siderophilic phenotype and how hemochromatotic animals respond to the oral Δfur infection have not yet been explored.

In this study, we used genetic and nongenetic hemochromatotic mouse models to comprehensively evaluate infection of WT Y. pseudotuberculosis PB1+ (termed PB1) and its isogenic Δfur mutant with an increased Ybt production, as well as the intestinal responses of Δfur-infected HH mice. Our results indicated that excessive Ybt production facilitated the rapid proliferation of Δfur, induced unfettered proinflammatory responses, disrupted the intestinal barrier, and caused acute lethality in hemochromatotic mice.

Results

The Δfur Mutant Displays Hyperlethality in Iron-Overloaded Mice.

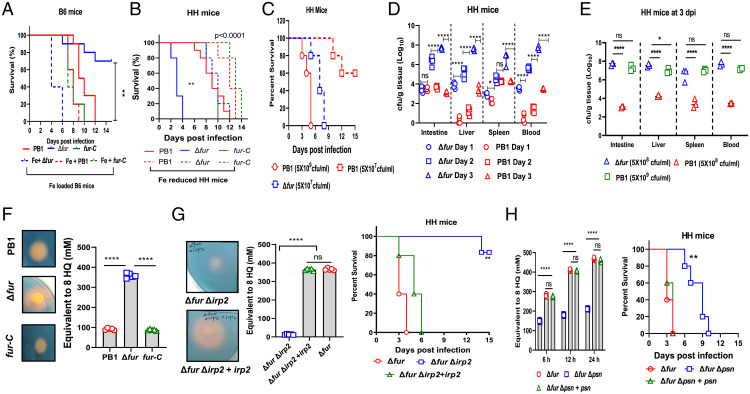

The Fur protein encoded by fur is a global iron regulator present in most prokaryotes and involved in the regulation of iron-responsive genes and a variety of metabolic pathways (12). Studies have shown that Salmonella fur mutants are attenuated in regular mouse models (17, 18). Similarly, Δfur by oral infection was substantially attenuated in C57BL6 (B6, 80% survival) (Fig. 1A) and BALB/C (60% survival) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A) mice compared to PB1 and fur-C strains, respectively. In contrast, Δfur was hypervirulent in HH (Fig. 1B) and Swiss Webster (SW) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1B) mice, resulting in 100% mortality within 4 and 6 d postinfection (dpi), respectively. In addition, infection with a 10-fold lower dose (5 × 107 colony forming units, CFU) of Δfur caused complete mortality in HH mice within 8 d (Fig. 1C), while infection with 5 × 108 CFU of PB1 caused complete mortality in HH and SW mice within 13 d (Fig. 1B and SI Appendix, Fig. S1B). Complete death was observed within 5 d in HH mice infected with 5 × 109 CFU of PB1 and partial death (40%) in HH mice infected with 5 × 107 CFU of PB1 (Fig. 1C). Unlike PB1 and fur-C infections (30 to 40% weight loss), Δfur infection caused ∼10% weight loss in HH or SW mice before death (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 C and D).

Fig. 1.

The high Ybt-producing Y. pseudotuberculosis Δfur mutant is hypervirulent to iron-overloaded mice. (A) Survival of WT B6 or iron-loaded B6 mice (n = 5 per group) infected with PB1, Δfur, or fur-C. (B) Survival of HH- or iron-reduced mice (n = 5 per group) infected as in B. (C) Survival of HH mice (n = 5 per group) infected with PB1 or Δfur. (D) Bacterial burden in PB1- or Δfur-infected HH mice (n = 5 per group) over the course of infection. (E) Bacterial burden in HH mice (n = 5 per group) infected with different dose of PB1 at 3 dpi. (F) Secretion of Ybt by PB1, Δfur, and Δfur complemented with fur (termed fur-C) grown to an OD600 of 0.8 in 5 mL LB broth at 28 °C. (G) Comparison of Ybt released by Δfur, ΔfurΔirp2, and ΔfurΔirp2 complemented with irp2 (termed ΔfurΔirp2+irp2) grown to an OD600 of 0.8 in 5 mL LB broth at 28 °C and their virulence in HH mice (n = 5 per group). (H) Comparison of Ybt released by Δfur, ΔfurΔpsn, and ΔfurΔpsn complemented with psn (termed ΔfurΔpsn+psn) (0.1 OD600 each bacterial culture) grown in 5 mL LB for the indicated period of time, and their virulence in HH mice (n = 5 per group). ns, no significance; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001.

Analysis of the iron contents in the liver, spleen, and serum revealed that the iron levels of HH and SW mice were comparable but significantly higher than those of B6 or BALB/c mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S1E). To further determine whether Δfur virulence was associated with the iron level in the host, B6 mice were orally administered iron dextran to increase the iron content, or HH mice were intraperitoneally administered an iron chelator, deferoxamine, to reduce the iron content from day 10 before infection until 15 dpi. After oral infection with Δfur, the iron-overloaded B6 mice died within 6 d (Fig. 1A), whereas the period of survival was extended to 12 d in iron-reduced HH mice (Fig. 1B). All above mice infected with either PB1 or fur-C died within 6 to 12 dpi (Fig. 1 A and B). Similarly, Δfur Y. enterocolitica WA displayed higher virulence in HH mice than its WT counterpart (SI Appendix, Fig. S1F).

Furthermore, the bacterial burden was measured by CFU in HH mice. Intriguingly, Δfur CFUs were 13-fold and 6.5-fold (log10) higher than the PB1 CFUs in the liver and blood at 1 dpi, respectively (Fig. 1D). The Δfur CFUs in the intestine, spleen, liver, and blood increased rapidly over the course of infection and were substantially higher than those of PB1 in these organs at 3 dpi (Fig. 1D). In contrast, PB1 CFUs in the blood, liver, and spleen of B6 mice progressively increased over the course of infection. While Δfur CFUs remained very low in those organs at 3 dpi (SI Appendix, Fig. S1G), HH mice infected with a higher dose of WT PB1 (5 × 109 CFU) resulted in a high bacterial load in organs similar to mice infected with 5 × 108 CFU of Δfur (Fig. 1E).

HH predisposes mice to infection with Y. pseudotuberculosis cured of the 70-kb virulence plasmid, termed pYV (6), which encodes the Yersinia Ysc type III secretion system and its effector proteins (Yops), and is critical for the pathogenicity of Y. pseudotuberculosis (19). Hence, we assessed whether absence of the pYV impacted the virulence of Δfur. We found that the pYV-cured Δfur mutant (Δfur pYV−) had similar virulence to Δfur in HH mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S1H). However, PB1 pYV− in HH mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S1H), and both the PB1 pYV− and Δfur pYV− mutants in B6 mice, were completely avirulent (SI Appendix, Fig. S1I). Taken together, results suggested that the Δfur was lethal to iron-overloaded mice, rather than in normal iron-load animals; the lethality of Δfur in HH mice was independent of the pYV plasmid.

Excessive Ybt Production Leads to Hypervirulence of Δfur PB1 in HH Mice.

Apart from several other phenotypes, fur mutants exhibit enhanced production of siderophores (12). The virulence of pathogenic Yersinia is strongly associated with their ability to synthesize the exclusive endogenous siderophore, Ybt, which plays a significant role in iron acquisition (2, 15). Thus, we attempted to examine whether the increased Ybt production was associated with the hyperlethality of Δfur. The Ybt was qualitatively and quantitatively evaluated by chrome azurol S assay (SI Appendix, Supplementary Materials and Methods). Qualitative analysis showed that the halo surrounding colonies of Δfur was approximately twofold larger than those surrounding colonies of PB1 and Δfur harboring a fur-complement plasmid (termed fur-C) (Fig. 1F). Quantitative analysis showed that the Ybt produced by Δfur in Luria Bertani (LB) broth was 3.9- and 4.14-fold higher than those produced by PB1 and fur-C, respectively (Fig. 1F). Siderophores extracted from 5 mL of bacterial cultures at the same optical density 600 nm (OD600) were subjected to high-resolution liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry analysis for characterizing Ybt (SI Appendix, Fig. S2A). Our results showed that the peaks of Fe(III)-complex and -free Ybt from the Δfur culture supernatant were dramatically higher than those from the PB1 culture supernatant (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). Hence, these results suggested that Δfur produced larger amounts of Ybt than PB1. Furthermore, the halo surrounding colony of Δfur Y. enterocolitica WA was bigger than that of its WT counterpart, indicating high Ybt production by Δfur Y. enterocolitica WA (SI Appendix, Fig. S2C).

Genes such as irp1-2, ybtP-Q, and psn in the ybt locus, located within Yersinia chromosomal high-pathogenicity islands are involved in the Ybt system and important for the high-pathogenicity phenotype of Yersinia (15, 16). Among these, irp2 encodes high-molecular-weight protein 2 involved in Ybt synthesis, and psn encodes the Ybt receptor associated with iron uptake. The irp2 mutant is unable to synthesize Ybt, while the psn mutant can produce and secrete Ybt but is unable to use it for iron sequestration (16). Our results showed that the ΔfurΔirp2 mutant failed to produce Ybt in the supernatant of in vitro bacterial culture (Fig. 1G and SI Appendix, Fig. S2B).

Furthermore, we demonstrated that Ybt production in the intestine of HH mice infected with PB1, Δfur, and ΔfurΔirp2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 D and E) had similar profiles as that in the supernatant of in vitro cultures (SI Appendix, Fig. S2B). The expression of irp2 and psn in the intestine of Δfur-infected HH mice was 21.27- and 19.29-fold (mean) higher than that of PB1-infected HH mice, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S2F). The ΔfurΔirp2 mutant was highly attenuated in HH mice compared to its parent and the irp2 trans isogenic strain (Fig. 1G), whereas the ΔfurΔpsn mutant exhibited the significantly decreased Ybt production due to lower bacterial numbers at the same culture period and extended the median survival times in HH mice compared to its parent and the psn trans isogenic mutant (Fig. 1H). In addition, HH mice infected with the PB1Δirp2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A) showed a similar survival profile as the ΔfurΔirp2 double mutant (Fig. 1G). However, different to the complete death of HH mice infected with the ΔfurΔpsn double mutant (Fig. 1H), HH mice infected with PB1Δpsn had 60% survival (SI Appendix, Fig. S3B). Both ΔfurΔirp2 and ΔfurΔpsn mutants were completely attenuated in B6 mice compared to the Δfur, irp2, or psn trans isogenic mutants (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 C and D). Additionally, oral infection with 5 × 108 CFU of PB1 or ΔfurΔirp2 along with 10 µM Ybt recapitulated acute mortality in HH mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S3E) and dramatically increased bacterial burdens in different organs (SI Appendix, Fig. S3F).

The in vitro growth kinetics showed that Δfur grew slower than PB1 in LB media (SI Appendix, Fig. S4A) but much faster than PB1 in LB supplemented with 50 mM FeCl3 (SI Appendix, Fig. S4B). The growth rate of the ΔfurΔirp2 mutant was comparable in both LB and LB plus Fe and comparable to that of Δfur in LB, but it was much slower than that of Δfur in LB plus Fe. However, the ΔfurΔpsn mutant displayed the slowest growth in both media (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A and B). Additionally, a competition experiment was performed by the mixed culture of PB1(pYA4454-Amp) and Δfur(pYA4454-Kan) (SI Appendix, Table S1) in LB plus 50 mM FeCl3 medium. The results showed that the mixed culture grown for 6 h slightly increased CFUs of PB1(pYA4454-Amp) in comparison to the single culture of PB1(pYA4454-Amp), while CFUs of Δfur(pYA4454-Kan) in both mixed and single cultures were comparable but dramatically higher than CFUs of PB1(pYA4454-Amp) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4C). Furthermore, whether addition of Ybt promotes the growth of PB1 or ΔfurΔirp2 in LB + FeCl3 medium was determined. Our results showed that CFUs of ΔfurΔirp2 grown in LB + FeCl3 media supplemented with Ybt were similar to CFUs of Δfur, but significantly higher than CFUs of ΔfurΔirp2 grown in LB + FeCl3 medium without Ybt supplementation. In comparison to no Ybt supplementation, Ybt addition to the medium increased PB1 growth but without significant difference (SI Appendix, Fig. S4D). In addition, administration of Ybt (10 µM) alone daily through intraperitoneal or intravenous route, caused complete mortality of HH mice within 4 d (SI Appendix, Fig. S4E). Alternatively, Ybt (10 µM) administered orally once daily did not result in any mortality of HH mice, whereas Ybt (10 µM) administered orally twice daily killed mice within 5 d (SI Appendix, Fig. S4E), thus indicating that Ybt alone was toxic to HH mice. However, the defined mechanisms need to be deciphered in our future studies.

Altogether, the above in vitro and in vivo data suggested that Ybt and its receptor-mediated iron uptake were crucial for Δfur infection. The high proliferation of Δfur under excessive iron conditions contributed to its hypervirulence in HH mice in a Ybt dependent manner.

Oral Δfur Infection in HH Mice Is Independent of M Cell Translocation and Elicits Severe Intestinal Tissue Damage.

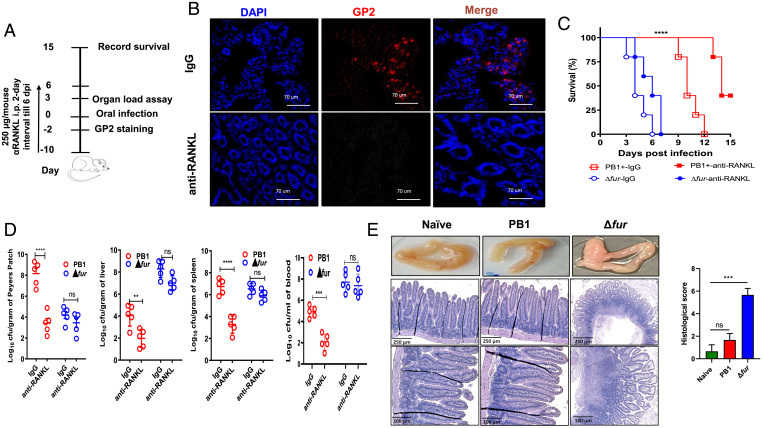

As an enteric pathogen, Y. pseudotuberculosis invades ileal Peyer’s patches (PPs) by exploiting microfold (M) cells as the main cellular entry points and then spreads to mesenteric lymph nodes and distal organs, thus causing diseases (20). Δfur disseminated to the blood and liver much faster than the PB1 strain in HH mice after oral infection (Fig. 1D). Therefore, we determined whether the fur mutation increased bacterial translocation via M cells. Glycoprotein 2 (GP2), a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein, is a marker of mature M cells (21). M cell differentiation requires receptor activator of NF-κB ligand (RANKL) and its receptor RANK (22). Intestinal M cells can be temporarily depleted by the administration of an anti-RANKL antibody (22, 23). Administration of mouse anti-RANKL antibody (Fig. 2A) transiently eliminated GP2+ M cells in the ileal PPs of HH mice compared to injection with isotype rat IgG (Fig. 2B). M-cell–depleted mice infected with PB1 exhibited 50% survival within 15 dpi and significantly attenuated bacterial loads in the PPs, liver, blood, and spleen at 3 dpi, while IgG-treated mice all died from PB1 infection within 12 dpi and had higher bacterial loads in those organs at 3 dpi (Fig. 2 C and D). In contrast, no significant alterations in mouse mortality (Fig. 2C) or bacterial burden in organs at 3 dpi (Fig. 2D) were observed between anti-RANKL– and IgG-treated Δfur-infected HH mice. Therefore, the results suggested that M cells of HH mice were dispensable for systemic and lethal infection of Δfur, but important for PB1 infection.

Fig. 2.

The hypervirulence of Δfur is independent of M-cell translocation. (A) Schematic of M-cell depletion by administering anti-RANKL antibodies. (B) Immunofluorescence staining of GP2+ M cells from ileal PPs from HH mice treated with anti-RANKL or IgG (n = 5 per group). Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. Representative images from each group are shown. (C) Survival of anti-RANKL– and IgG-treated HH mice (n = 5 per group) infected with 5 × 108 CFU of PB1 or Δfur. (D) Bacterial burden in the tissues and blood of HH mice (n = 5 per group) infected as described in C at 3 dpi. (E) Representative gross pathology and histopathology images (H&E stain) and histological scoring of the intestine sections from HH mice infected as described in C at 3 dpi (n = 3 per group). The intestine sections of naïve mice served as uninfected controls. The H&E-stained intestine sections were blindly assessed and scored by three individuals, as described earlier (60). ns, no significance; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Furthermore, assessment of the pathological alterations in the small intestine from naïve, PB1-, Δfur-infected HH mice revealed that the Δfur-infected mice developed severe edema and inflammation at 3 dpi (Fig. 2E). H&E staining showed that Δfur infection caused severe intestinal damage characterized by villus disruption and profound cell death (Fig. 2E). In contrast, no discernible pathological changes were observed in the small intestines of naïve or PB1-infected mice (Fig. 2E). Similar observations were found in the liver and spleen (SI Appendix, Fig. S5).

Acute Alterations of Gene-Expression Profiles in the Intestine of Δfur-Infected HH Mice.

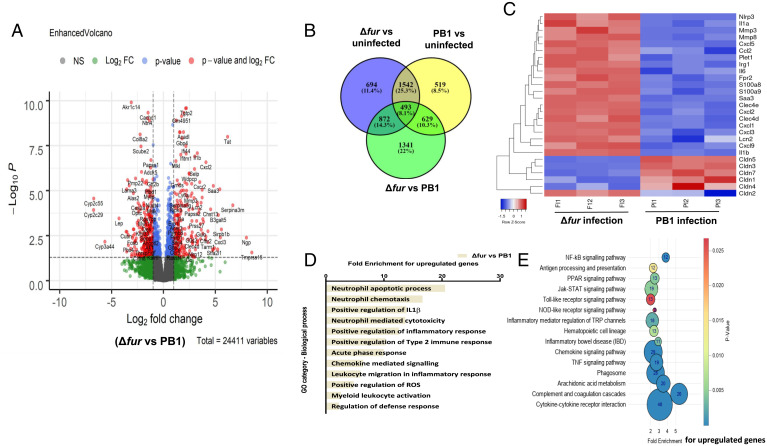

To elucidate the host responses induced by Δfur infection, the gene-expression profile of HH mice was determined by RNA sequencing and the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified by analysis package DESeq2. Of the >24,000 profiled host transcripts in the Δfur- or PB1-infected small intestine isolated at 3 dpi, 517 and 789 genes were up-regulated (log2 fold-change ≥ 2), respectively, and 1,748 and 1,373 genes were down-regulated compared to those in the uninfected mouse intestine. Compared to those in the PB1-infected intestine, the Δfur-infected intestine had 1,527 genes with increased and 1,806 genes with decreased transcript abundance (SI Appendix, Datasets S1 and S2). The top 50 genes with increased or decreased transcript abundance in Δfur vs. uninfected compared to those in PB1 vs. uninfected are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S6A. The DEGs between Δfur- and PB1-infected intestines are shown in Fig. 3A. Furthermore, 1,341 genes were differentially expressed in Δfur- vs. PB1-infected intestine but not in PB1/uninfected or Δfur/uninfected intestine (Fig. 3B). Comparison of the gene-expression levels between Δfur- and PB1-infected HH mice suggested that Δfur infection dramatically increased the transcription of genes encoding proinflammatory factors and neutrophil migration (interleukin [IL]-1β, IL-6, Cxcl2, Cxcl3, Cxcl5, Ccl2, S100a8, S100a9, Lcn2) (Fig. 3C). Genes encoding inflammasome, superoxide production, chemotactic, and signaling factors (Irg1, Nlrp3, Fpr2); metal ion scavenging proteins (Lcn2); and acute phase response fibrinolysis (Mmp3, Mmp8, Saa3) were more strongly expressed in the intestine of Δfur-infected mice than in the intestine of PB1-infected mice (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, transcript abundance of groups of genes encoding proteins, such as claudin-3, -5, or -7 (Fig. 3C)—which are associated with barrier maintenance, tissue damage repair, and regeneration (24, 25)—were significantly decreased in the Δfur-infected intestine compared to those in the PB1-infected intestine (Fig. 3C), while pore-forming claudins, such as claudin-2, were increased (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Transcriptome of the small intestine from infected HH mice. RNA-seq analysis of gene alterations in naïve, Δfur- or PB1-infected HH mice at 3 dpi (n = 3 per group). (A) Volcano plot showing DEGs. (B) Venn diagram of DEGs from naïve vs. PB1 vs. Δfur. (C) Heat map of selected host transcripts based on the DESeq2 analysis. Color coding is based on the rlog transformed read count values. (D) KEGG pathway analysis of up-regulated gene targets in the Δfur-infected mouse transcriptome. (E) GO functional clustering of genes that were up-regulated for biological processes (the most significantly affected categories are listed).

Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis demonstrated significantly affected categories of genes that were altered more by Δfur infection than by PB1 infection (Fig. 3D and SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). In the case of genes with increased transcript abundance, the GO terms were associated with chemotaxis of neutrophils, neutrophil-mediated cytotoxicity, regulation of IL-1β, and positive regulation of the inflammatory response, indicating that Δfur induced stronger inflammatory responses than those induced by PB1 (Fig. 3D). However, the GO terms including the defense response, cell–cell adhesion, and wound healing were associated with transcripts that were less abundant (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). Furthermore, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis suggested that cytokine–cytokine receptor interactions, the complement, and coagulation cascade, the NF-κB signaling pathway, and chemokine signaling pathways were enhanced (Fig. 3E), and cell-adhesion molecules and Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling pathways were suppressed in the Δfur-infected mouse intestine (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C).

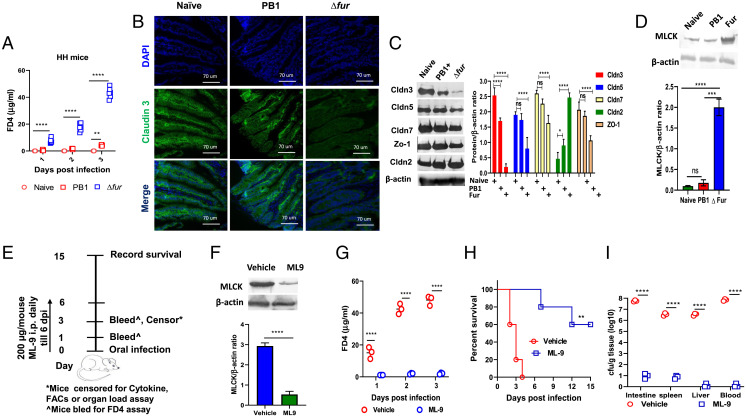

Δfur Infection Induces Rapid Disruption of Intestinal Tight Junctions and High Levels of Myosin Light-Chain Kinases.

The intestinal epithelium contains polarized epithelial cells that form tight junctions (TJ) to offer a physical barrier for preventing bacterial invasion and dissemination (26). Δfur rapidly disseminated to peripheral organs (Fig. 1D) and resulted in severe intestinal damage in HH mice (Fig. 2E) compared to that caused by the PB1 strain at 3 dpi. Furthermore, transcriptome analysis revealed significant down-regulation of the genes encoding claudin-3, -5, and -7 (Fig. 3C), which are responsible for maintaining TJ integrity (27). Thus, we hypothesized that Δfur infection might cause a drastic disruption of intestinal TJs in HH mice. To test this hypothesis, mice infected with PB1 or Δfur were orally administered fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran (4,000 Da, FD4) at 1, 2, and 3 dpi. The assay is based on the principle that increased epithelial barrier disruption would result in enhanced leakage of FD4 into circulation resulting in increased FITC fluorescence (28, 29). The serum levels of FD4 were substantially increased in Δfur-infected HH and iron-overloaded B6 mice over the 3-d course of infection, but very low in PB1-infected hemochromatotic mice (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S7A), and Δfur Δirp2- and Δfur Δpsn-infected HH mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S7B). At 3 dpi, the serum levels of FD4 in PB1- or Δfur Δpsn-infected hemochromatotic mice were slightly increased in comparison to those in Δfur Δirp2-infected mice (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S7 A and B). Intriguingly, the number of Δfur Δpsn and PB1 in organs of HH mice was comparable over the 3-d course of infection, but was substantially higher than that of Δfur Δirp2 in organs at 3 dpi, (SI Appendix, Fig. S7C). The results suggested that bacterial organ loads in HH mice infected with PB1, Δfur Δpsn, or Δfur Δirp2 were not correlated with the serum FD4 levels at early infection stage, but correlated with animal survival (Fig. 1 B, G, and H). Iron-reduced HH mice or B6 mice infected with Δfur or PB1 had low levels of serum FD4 (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 D and E). Our results implied that Δfur infection rapidly affected the intestinal epithelial integrity of hemochromatotic mice by disrupting TJ to facilitate bacterial dissemination from the intestine to blood, followed by dissemination to the liver and spleen. Importantly, intestinal TJ disruption in infected mice occurred in Ybt- and iron-dependent manner.

Fig. 4.

Disruption of the intestinal TJ and increase in MLCK in Δfur-infected HH mice. (A) Serum FD4 levels were assessed at 4-h following oral administration in naïve, PB1-, and Δfur-infected HH mice (n = 6 per group). (B) Immunofluorescence staining of claudin-3 in the small intestine of mice (n = 3 per group) described in A at 3 dpi. Representative images from each group are shown. Cell nuclei were stained with DAPI. (C) Representative immunoblot analysis of small intestine homogenates from infected HH mice (n = 3 per group) as described in A at 3 dpi. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The protein levels of the indicated claudins and ZO-1 in the small intestine of uninfected or infected mice (n = 3) were quantified by ImageJ software and normalized to the level of β-actin. (D) Analysis of the level of MLCK (n = 3 per group) by immunoblot as described in C. (E) Schematic of the inhibition of MLCK by administering ML-9. (F) Detection of MLCK in the small intestine of ML-9– or vehicle-treated Δfur-infected mice (n = 3 per group) at 3 dpi by immunoblot. (G) The serum FD4 level at 3 dpi (n = 3 per group). (H) Survival (n = 5 per group) of Δfur-infected mice treated with ML-9 or the vehicle. (I) Bacterial load in different tissues (n = 3 per group) at 3 dpi as in F. ns, no significance; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Furthermore, analysis of the TJ protein claudin-3 in the small intestine of HH mice at 3 dpi via immunofluorescence staining revealed organized localization of claudin-3 at the cell boundaries of epithelial cells manifesting intact TJs in naïve mice. Infection with PB1, ΔfurΔirp2, or ΔfurΔpsn mutant slightly decreased claudin-3 expression, but the typical TJ structure was retained (Fig. 4B and SI Appendix, Fig. S7F). However, Δfur infection led to extensive claudin-3 degradation and diffusion within cells, suggesting immense disruption of TJ integrity (Fig. 4B). Additionally, immunoblot analysis of the intestinal lysates demonstrated that Δfur infection resulted in a striking decrease of the protein levels of claudin-3, -5, -7, and ZO-1 and an increase of claudin-2, a pore-forming claudin, compared to those in the control, verifying the disruption of TJ integrity (Fig. 4C). However, the protein levels of claudin-2, -3, -5, -7, and ZO-1 in PB1-, ΔfurΔirp2-, or ΔfurΔpsn-infected mice were comparable to those in the naïve mice, indicating unaltered barrier integrity (Fig. 4C and SI Appendix, Fig. S7G).

Myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK) phosphorylates MLC, leading to actin–myosin interactions and cytoskeletal sliding, which induce epithelial barrier breakdown (30, 31). The crucial role of MLCK in regulating TJs is well documented, and inhibition of MLCK improves intestinal barrier integrity (30, 31). Transcriptomic and protein analyses indicated that Δfur infection substantially increased MLCK expression in the intestine of HH mice compared to naïve or PB1-infected HH mice (Fig. 4D and SI Appendix, Datasets S1 and S2). Subsequently, ML-9, an MLCK inhibitor (32), was used to evaluate the role of MLCK in TJ disruption. ML-9 treatment (Fig. 4E) significantly decreased MLCK levels in Δfur-infected HH mice intestine (Fig. 4F). In contrast to vehicle-treated mice, ML-9–treated mice displayed an extremely low serum FD4 flux (Fig. 4G) and rescued 60% of Δfur-infected mice (Fig. 4H). Furthermore, at 3 dpi, Δfur CFUs recovered from the intestine, spleen, liver, and blood of ML-9–treated mice were substantially lower than those from vehicle-treated mice (Fig. 4I).

Δfur Infection Initiates High Inflammatory Responses in the Intestine of HH Mice.

Transcriptomic analysis revealed a substantial induction of proinflammatory cytokines (Fig. 3C). Aberrant or uncontrolled release of proinflammatory factors damages the epithelial cell barrier. To confirm the transcriptomic data, the cytokine profiles of both Δfur- and PB1-infected intestinal tissues were analyzed (Fig. 5A and SI Appendix, Fig. S8A). Consistent with the transcriptomic data, in the Δfur-infected intestine, IL-1α, associated with neutrophil recruitment and activation of inflammatory markers (33), was 17.4-fold higher than that in the PB1-infected intestine. IL-6 and G-CSF, which attract neutrophils to the site of infection (34, 35), were 77.3- and 40-fold higher in the Δfur-infected intestine than those in the PB1-infected intestine, respectively (Fig. 5A). Additionally, IL-1β and IL-33, which belong to the IL-1 cytokine family and are known to induce permeability of epithelial TJ (36), were increased by 10- and 12-fold in Δfur-infected tissue compared to those in PB1-infected tissue, respectively (Fig. 5A). Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), released during acute inflammation resulting in necrosis or apoptosis (37), was increased by fourfold in Δfur-infected tissue compared to that in PB1-infected tissue. MIP1α (CCL3) and MIP1β (CCL4), involved in the activation of granulocytes, the release of reactive oxygen species from neutrophils, and the induction of proinflammatory cytokines (38) were substantially increased in the intestine of Δfur-infected mice compared to PB1-infected mice intestine. MCP1/CCL2, which drives the chemotaxis of myeloid and lymphoid cells (39), was dramatically increased by Δfur infection. Additionally, Δfur infection resulted in 9.3-fold higher Lcn2 levels at 3 dpi than PB1 infection (SI Appendix, Fig. S8B). Therefore, our results suggest that Δfur infection elicits a cytokine storm in HH mice that might lead to rapid lethality.

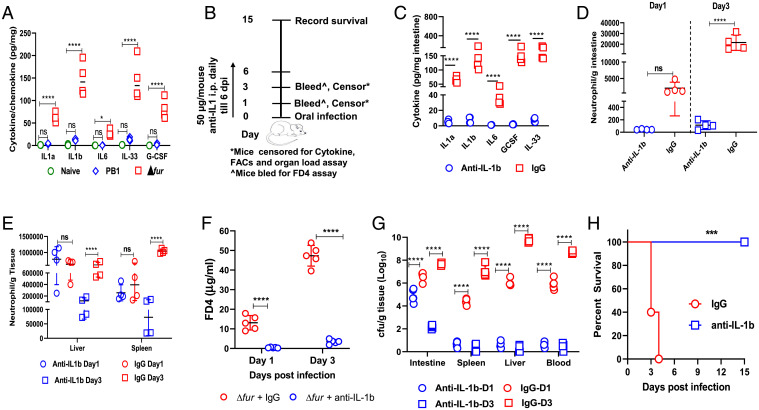

Fig. 5.

Blockage of IL-1β prevents TJ disruption and rescues Δfur-infected HH mice. (A) Cytokine analysis of the small intestine from naïve-, Δfur-, or PB1-infected HH mice (n = 4 per group) at 3 dpi. (B) Schematic of the neutralization of IL-1β in Δfur-infected HH mice. (C) Cytokines in the small intestine of Δfur-infected mice (n = 4 per group) treated with anti–IL-1β or IgG at 3 dpi. (D and E) Quantification of neutrophils (CD11b+ Ly6G+) in the small intestine (D), liver, or spleen (E) from Δfur-infected mice (n = 4 per group) treated with anti–IL-1β or IgG at 1 and 3 dpi using flow cytometry. (F) Serum FD4 levels in infected mice (n = 5 per group) at 3 dpi as described in B. (G) Bacterial load in different tissues of infected mice (n = 5 per group). (G) Survival of Δfur-infected mice (n = 5 per group) treated with anti–IL-1β or IgG. ns, no significance; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Overwhelming IL-1β Signaling Induced by Δfur Infection Leads to the Disruption of Intestinal TJs and Rapid Lethality in HH Mice.

Dramatic induction of IL-1β at both transcriptional and translational levels was observed in the intestine of Δfur-infected HH mice (Figs. 3C and 5A). Studies have shown that IL-1β–induced increase in intestinal epithelial TJ permeability contributes to the exacerbation of disease progression in hosts with underlying diseases (31, 40). Additionally, high IL-1β release during infection leads to excessive neutrophil recruitment, causing tissue damage and functional impairment of multiple organs (41). Therefore, we investigated whether the excessive IL-1β production (Fig. 5A) in the intestine of Δfur-infected HH mice promoted inflammation and TJ disruption, leading to systemic infection and acute death. IL-1β was ablated in Δfur-infected HH mice by administering anti-mouse IL-1β antibodies daily from the day of infection (Fig. 5B). Compared to the rat IgG control, anti–IL-1β treatment dramatically decreased the levels of IL-1β and other proinflammatory-associated cytokines/chemokines—such as IL-1α, IL-33, IL-6, G-CSF, TNF-α, MIP-1α/β, and MCP—at 3 dpi (Fig. 5C and SI Appendix, Fig. S8A). Additionally, we analyzed myeloid cells from anti–IL-1β- or IgG-treated Δfur-infected HH mice using flow cytometry (FACS) (SI Appendix, Fig. S8D). In the intestine, the number of neutrophils (CD11b+ Ly6G+) increased by 10-fold in the IgG-treated mice at 3 dpi compared to that at 1 dpi (Fig. 5D). In contrast, the neutrophil counts in anti–IL-1β–treated mice remained similar at 1 and 3 dpi and were ∼20-fold and ∼200-fold lower than those in IgG-treated mice at 1 and 3 dpi, respectively (Fig. 5D). Neutrophil counts in the liver or spleen of anti–IL-1β– and IgG-treated mice were comparable at 1 dpi, but were 5-fold and 10-fold lower in anti–IL-1β–treated mice than IgG-treated mice at 3 dpi, respectively (Fig. 5E). IL-1β blockade significantly decreased the level of serum FD4 (Fig. 5F) and bacterial CFUs in different organs (Fig. 5G) at 1 and 3 dpi compared to those after the IgG treatment, indicating reduced intestinal paracellular permeability and minimized TJ disruptions. Strikingly, IL-1β blockade rescued 100% of Δfur-infected mice (Fig. 5H).

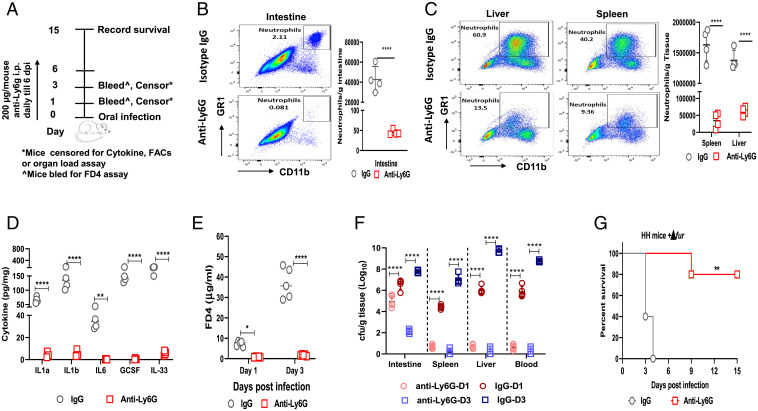

To determine whether the excessive influx of neutrophils led to intestinal barrier disruption in HH mice, we depleted neutrophils in Δfur-infected HH mice by administering anti-mouse Ly6G antibodies (Fig. 6A). The anti-Ly6G treatment ablated neutrophils in the intestine (Fig. 6B), liver, and spleen (Fig. 6C) at 3 dpi compared to those in the IgG control. Similarly, anti-Ly6G treatment dramatically decreased the levels of IL-1β and aforementioned proinflammatory-associated cytokines/chemokines in the intestine of HH mice at 3 dpi (Fig. 6D and SI Appendix, Fig. S8E). Additionally, neutrophil depletion significantly decreased the level of serum FD4 (Fig. 6E) and the Δfur CFU in different organs (Fig. 6F) at 1 and 3 dpi compared to those in IgG control and rescued 80% of Δfur-infected mice (Fig. 6G). Collectively, the uncontrolled IL-1β signaling elicited in Δfur-infected HH mice mediated excessive influx of neutrophils and vice visa, which produces high amounts of proinflammatory cytokines, leading to rapid disruption of intestinal TJ, severe systemic infection, and acute death. Blockade of IL-1β or neutrophils could ameliorate overt pathology and subvert outcomes in hemochromatotic hosts.

Fig. 6.

Inhibition of neutrophilia prevents TJ disruption and rescues Δfur-infected HH mice. (A) Schematic of neutrophil depletion in Δfur-infected HH mice. (B and C) Quantification of neutrophils (CD11b+ Ly6G+ GR1+) in the small intestine (B), liver, or spleen (C) from Δfur-infected mice (n = 4 per group) treated with anti-Ly6G or the isotype control at 3 dpi using flow cytometry. (D) Cytokines in the small intestine homogenates at 3 dpi from infected mice (n = 4) as in B. (E) Serum FD4 levels in infected mice (n = 5 per group) at 3 dpi as described in B. (F) Bacterial load in different tissues of infected mice (n = 5 per group) at 3 dpi as described in B. (G) Survival of Δfur-infected mice (n = 5 per group) treated with anti-Ly6G or IgG. ns, no significance; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001.

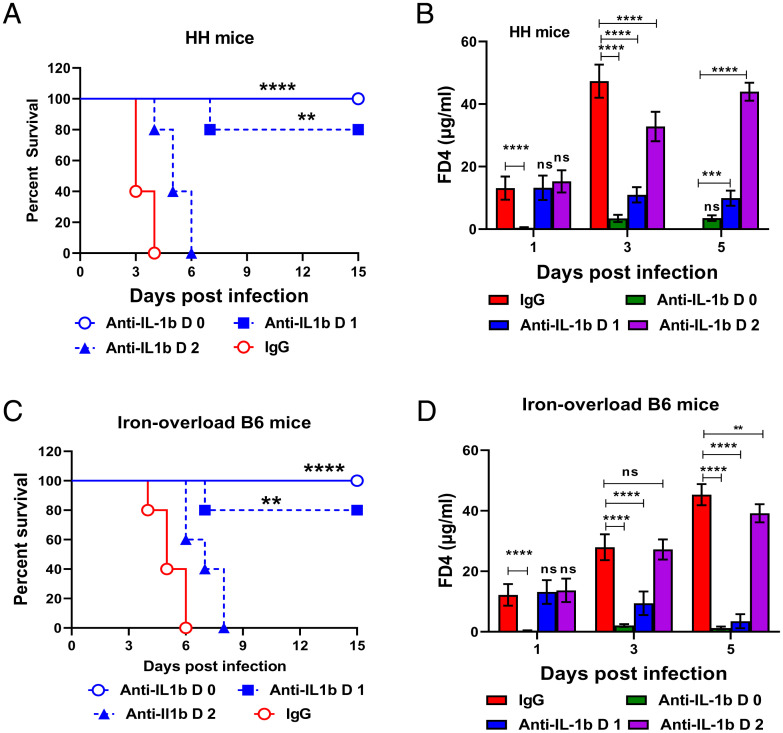

Anti–IL-1β Treatment Ameliorates the Outcomes of Both Genetic and Nongenetic Hemochromatotic Mice at Different Stages of Δfur Infection.

Our results showed that Δfur-infected hemochromatotic mice developed a rapid lethal infection within a short period of time (Fig. 1 B and C), and Δfur-infected mice all survived after receiving an immediate administration of anti–IL-1β (Fig. 5). In real scenarios, hemochromatosis patients infected with siderophilic bacteria develop certain disease symptoms before treatment. In addition, a human anti–IL-1β monoclonal antibody (mAb), canakinumab, is being tested for treating multiple diseases in phase IIb/III trials (42). Thus, determining which timepoint to administer anti–IL-1β during disease development would be clinically relevant. Given this, survival and the serum level of FD4 of Δfur-infected HH and iron-overloaded B6 mice treated with anti-mouse IL-1β starting on 0, 1, or 2 dpi were evaluated. Initiation of anti–IL-1β therapy from 0 dpi rescued 100% of both mice, and from 1 dpi rescued 80% of those mice (Fig. 7 A and C). During both early treatments, mice were healthy as depicted by low levels of serum FD4 (Fig. 7 B and D) and increased weight gaining during the 15-d observation period (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 F and G). However, administration of anti–IL-1β at 2 dpi only extended the median survival times in both mice (Fig. 7 A and C) with substantially elevated levels of serum FD4 (Fig. 7 B and D). These results indicate that early IL-1β blockage during infection can be an effective strategy to prevent siderophilic infections in hemochromatotic individuals.

Fig. 7.

Anti–IL-1β treatment ameliorates the susceptibility of iron-overloaded mice to Δfur infection. Δfur-infected hemochromatotic mice were treated with anti–IL-1β or IgG at 1 and 2 dpi, respectively. (A) Survival of HH mice (n = 5 per group). (B) Analysis of FD4 in serum from HH mice (n = 5 per group). (C) Survival of iron-overloaded B6 mice (n = 5 per group). (D) Analysis of FD4 in serum from iron-overloaded B6 mice (n = 5 per group). ns, no significance; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Discussion

In this study, the Δfur mutant with high Ybt production, as a siderophilic bacterium defined in previous studies (14, 43, 44), manifested attenuation in normal iron-loaded mice but was hypervirulent to iron-overloaded mice. In addition, high Ybt production coupled with the high proliferation of Δfur under excessive iron conditions contributed to its hypervirulence in HH mice. Our data indicated that oral, intravenous, or intraperitoneal administration with certain amounts of Ybt alone could lead to complete mortality in mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S4E). However, how Ybt causes lethality is unclear yet, and needs to be pursued further. Similar to a previous study (45), dissemination of PB1 was partially associated with M cells. Interestingly, dissemination of Δfur within HH mice was independent of M cells but resulted in rapid disruption of intestinal TJ barrier as evidenced by the high-serum FD4 and decreased expression of TJ proteins claudin-3, -5, -7, and ZO-1 at both the transcriptional and translational levels. Studies have reported that iron overload results in a defective TJ barrier in humans and animals (46, 47). Therefore, the extraordinarily rapid growth of Δfur in the intestine of HH mice because of high production of Ybt coordinated with its receptor (Psn) may exacerbate defect of TJ barrier, lead to loss of the intestinal barrier, and promote bacterial dissemination to the blood, liver, and other organs. The high-iron contents in these organs may further promote explosive bacterial growth, resulting in sepsis, severe tissue damage, and acute death.

Intestinal transcriptome and cytokine analyses demonstrated that Δfur-infected HH mice had a dramatic increase of proinflammatory cytokines associated with the IL-1β signaling pathway, neutrophil recruitment, NF-κB, and TNF-α signaling pathways, and a decrease of TJ proteins associated with the integrity of the intestinal barrier. Additionally, Δfur-infected HH mice exhibited substantially increased production of the antimicrobial protein Lcn2. However, the increased level of Lcn2 seemed unable to control Δfur proliferation. As mentioned earlier (48), iron-overload tips the immunoregulatory balance of hosts unfavorably and impairs host immunity, which may favor the explosive proliferation of Δfur in HH mice. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) injection in hemochromatotic mice is reported to induce acute inflammation and increase mortality (46, 49). Y. pseudotuberculosis LPS is a potent proinflammatory activator of TLR4 (50). Moreover, Lcn2 up-regulation is TLR4-dependent (51), and Lcn2 in combination with Ybt can strongly induce proinflammatory cytokine secretion (52). In addition, iron-overload promotes gut leakage and translocation of organismal molecules (46). Therefore, robust replication of Δfur releases large amounts of LPS and Ybt that may easily access to intestinal lamina propria of HH mice, and lead to uncontrolled proinflammatory responses, aggressive tissue damage, and acute death.

Moreover, iron-overload or siderophores compromises the phagocytic and bactericidal capacities of neutrophils from mice and humans (53, 54). In addition, Y. pseudotuberculosis can disrupt intestinal barrier integrity through hematopoietic TLR2 signaling (32). So, there is another possibility that high replications of Δfur in the intestinal lumen of HH mice may activate TLR2/4 signaling and the paracellular transport of Δfur to lamina propria via the leaky gut, triggering elicitation of high amounts of IL-1β and recruitment of excess neutrophils. Therefore, the more compromised host responses caused by the combination of iron-overload and Ybt in Δfur-infected HH mice may not effectively control Yersinia infection, leading to detrimental consequences. Further studies are required to test these hypotheses.

A dichotomous role of IL-1β in driving inflammation is well documented (55). Low levels of IL-1β seem to help the resolution of infection (56), whereas high amounts of IL-1β release and excessive recruitment of neutrophils during intestinal inflammation leads to hypercytokinemia and further exacerbates disease status (57). Additionally, excessive IL-1β is known to induce intestinal TJ permeability mediated by an increase in MLCK protein expression and activity (58). The increased MLCK disrupts the barrier integrity by perturbing the interaction between TJ proteins and the actin-myosin cytoskeleton (58). Δfur infection triggered high levels of MLCK in the intestine of HH mice, which were correlated with substantially increased intestinal TJ permeability, bacterial organ loads, and inflammatory cytokines. Treatment with ML-9 decreased disruption of intestinal permeability and significantly improved mouse survival. Direct ablation of either IL-1β or neutrophils dramatically ameliorated the Δfur infection-mediated rapid disruption of intestinal TJs and led to better survival than inhibition of MLCK. Thus, alleviation of the initially dysregulated inflammation would be more effective than that of downstream responses.

Altogether, our study suggests that unfettered IL-1β production in the intestine of Δfur-infected iron-overloaded mice results in excessive neutrophil infiltration and acute hyperinflammation, causing rapid disruption of the intestinal barrier by activation of MLCK, leading to profuse bacterial dissemination to the blood and subsequent lethal systemic infection. More detailed mechanisms about how Δfur infection trigger overwhelming responses in iron-overloaded mice need to be deciphered in further studies. In addition, anti–IL-1β treatment via an early intervention effectively rescued genetic and nongenetic iron-overloaded mice with Δfur infection, which provides a therapy for iron-overloaded patients with severe siderophilic bacterial infections.

Methods

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, Culture Conditions, and Molecular Protocols.

All the bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in SI Appendix, Table S1. All the reagents, bacterial cultures, and molecular and genetic procedures used in this study are described in SI Appendix.

Ybt Detection and Quantification.

The details of Ybt detection and quantification are described in SI Appendix.

Animals and Animal Experiments.

WT C57BL/6J (B6) and HH B6.129S6-Hfetm2Nca/J mice in the B6 background were procured from Jackson Laboratories. BALB/c mice and SW mice were obtained from Taconic and Charles Rivers, respectively. Mice were bred and/or housed in a specific pathogen-free facility at the Albany Medical College. Male and female mice 6- to 8-wk old were used in the present study. Animal studies were conducted following the NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (59) and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Albany Medical College (ACUP# 20-01001). Iron-overloaded B6 mice or iron-reduced HH mice were generated as described in the SI Appendix. MLCK inhibition and depletion of IL-1β or neutrophils were performed as described in SI Appendix. Depletion of IL-1β or neutrophils was performed as described in the SI Appendix. Mice were deprived of food and water for 6 h and then administered 200 µL of PBS containing 5 × 108 CFU of the indicated Y. pseudotuberculosis by oral gavage with PBS as a control. The mobility and mortality of infected animals were monitored for 15 d. Bacterial burden in different tissues was determined as described in SI Appendix. All the results were confirmed from two independent experiments.

Iron Assay.

The measurement of the iron content in mouse tissues and serum using an iron assay kit is described in SI Appendix.

FITC-Dextran Assay.

FITC-dextran assays for intestinal permeability are described in SI Appendix.

Histopathology Analysis.

Tissue sections were stained with H&E, immunostained, and examined as described in SI Appendix.

Quantification of Cytokines/Chemokines.

The cytokine/chemokine profiles of small intestine homogenates of uninfected, PB1-, or Δfur-infected HH mice were determined using the Bio-Plex Pro Mouse Cytokine Plex assay. The details are provided in SI Appendix.

RNA-Sequencing Analysis of the Small Intestine.

Uninfected, PB1-, or Δfur-infected HH mice (n = 3 each group) were killed at 3 dpi, and their intestines were harvested and stored in RNAlater at −80 °C. Total RNA was extracted from frozen intestine sections using an RNAeasy mini kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s instructions. To remove trace DNA, a column DNase treatment was performed using RNase-free DNase according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The quality of total RNA was evaluated using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). A complementary DNA library was prepared using a New England Biolabs Ultra II Directional kit, and sequencing was performed on the Nextseq500 system according to Illumina’s standard protocol (https://en.novogene.com/). After sequencing, individual base calls were demultiplexed and assigned to fastq files using Illumina’s bcl2fastq program. Raw fastq files were then assessed for quality using FASTQC. Following evaluation of quality and control, RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) libraries were aligned to the GRCm38/mm10 mouse reference genome, and gene counts were generated using STAR. The RNA-seq data are uploaded to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database and is available under accession no. GSE180888. Analysis of differential gene expression was performed using the DESeq2 package in R. Heatmaps were generated using heatmap, and dot plots were generated using ggplot26.

GO and KEGG Enrichment Analyses.

Significant DEGs were subjected to GO enrichment analysis by the GOseq R Package to correct for the gene length bias. GO analysis was performed using the GeneOntology online tool powered by Panther (https://geneontology.org/). The top GO categories were identified according to the P value score. Pathway analysis of the significant DEGs was performed using the KEGG database (https://www.kegg.jp/kegg/). Statistical enrichment of the DEGs in KEGG pathways was tested using KOBAS.

Flow Cytometry Analysis.

A single-cell suspension was prepared from the intestine, spleen, and liver and stained with the fluorescently labeled antibodies listed in SI Appendix. Data were acquired using a BD FACS Canto machine and analyzed using FlowJo software. The total live neutrophil count was normalized to the tissue weight and plotted as the number of live neutrophils per gram tissue. The details are provided in SI Appendix.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analyses of comparisons of data among groups were performed with one-way ANOVA/univariate or two-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used for survival analysis. All data were analyzed using GraphPad PRISM 8.0 software. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (ns, no significance; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001). Experiments were repeated twice and representatives of two individual experiments are depicted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Roy Curtiss III at the University of Florida for sharing the χ strains and pYA plasmids; Dr. Xue Xia for assisting with the immunofluorescence staining and mass spectrometry; and Xiaoying Kuang for generating the graphs of the Kyoto Enycyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways. This work was supported by NIH Grants R01AI125623 (to W.S.), R01AI148366 (to Z.G.), and R21AI137719 (to F.W.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2110166119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the GEO database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE180888).

References

- 1.Cassat J. E., Skaar E. P., Iron in infection and immunity. Cell Host Microbe 13, 509–519 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rakin A., Schneider L., Podladchikova O., Hunger for iron: The alternative siderophore iron scavenging systems in highly virulent Yersinia. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2, 151 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan F. A., Fisher M. A., Khakoo R. A., Association of hemochromatosis with infectious diseases: Expanding spectrum. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 11, 482–487 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pietrangelo A., Hereditary hemochromatosis: Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Gastroenterology 139, 393–408, 408 e1–2 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emanuele D., Tuason I., Edwards Q. T., HFE-associated hereditary hemochromatosis: Overview of genetics and clinical implications for nurse practitioners in primary care settings. J. Am. Assoc. Nurse Pract. 26, 113–122 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miller H. K., Schwiesow L., Au-Yeung W., Auerbuch V., Hereditary hemochromatosis predisposes mice to Yersinia pseudotuberculosis infection even in the absence of the type III secretion system. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 6, 69 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thwaites P. A., Woods M. L., Sepsis and siderosis, Yersinia enterocolitica and hereditary haemochromatosis. BMJ Case Rep. 2017, bcr2016218185 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Patino J., et al. , 659: Fulminant Vibrio vulnificus infection in a patient with homozygous hemochromatosis HFE H63 mutation. Crit. Care Med. 49, 324 (2021).33332816 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerhard G. S., et al. , Vibrio vulnificus septicemia in a patient with the hemochromatosis HFE C282Y mutation. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 125, 1107–1109 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilson B. R., Bogdan A. R., Miyazawa M., Hashimoto K., Tsuji Y., Siderophores in iron metabolism: From mechanism to therapy potential. Trends Mol. Med. 22, 1077–1090 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hider R. C., Kong X., Chemistry and biology of siderophores. Nat. Prod. Rep. 27, 637–657 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Troxell B., Hassan H. M., Transcriptional regulation by Ferric Uptake Regulator (Fur) in pathogenic bacteria. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 3, 59 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galindo C. L., Rosenzweig J. A., Kirtley M. L., Chopra A. K., Pathogenesis of Y. enterocolitica and Y. pseudotuberculosis in human yersiniosis. J. Pathogens 2011, 182051 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stefanova D., et al. , Endogenous hepcidin and its agonist mediate resistance to selected infections by clearing non-transferrin-bound iron. Blood 130, 245–257 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carniel E., Guilvout I., Prentice M., Characterization of a large chromosomal “high-pathogenicity island” in biotype 1B Yersinia enterocolitica. J. Bacteriol. 178, 6743–6751 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perry R. D., Fetherston J. D., Yersiniabactin iron uptake: Mechanisms and role in Yersinia pestis pathogenesis. Microbes Infect. 13, 808–817 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtiss R. III, et al. , Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium strains with regulated delayed attenuation in vivo. Infect. Immun. 77, 1071–1082 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vishwakarma V., et al. , Evaluation of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium TTSS-2 deficient fur mutant as safe live-attenuated vaccine candidate for immunocompromised mice. PLoS One 7, e52043 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schubert K. A., Xu Y., Shao F., Auerbuch V., The Yersinia type III secretion system as a tool for studying cytosolic innate immune surveillance. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 74, 221–245 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mecsas J., Bilis I., Falkow S., Identification of attenuated Yersinia pseudotuberculosis strains and characterization of an orogastric infection in BALB/c mice on day 5 postinfection by signature-tagged mutagenesis. Infect. Immun. 69, 2779–2787 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mabbott N. A., Donaldson D. S., Ohno H., Williams I. R., Mahajan A., Microfold (M) cells: Important immunosurveillance posts in the intestinal epithelium. Mucosal Immunol. 6, 666–677 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knoop K. A., et al. , RANKL is necessary and sufficient to initiate development of antigen-sampling M cells in the intestinal epithelium. J. Immunol. 183, 5738–5747 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lai N. Y., et al. , Gut-innervating nociceptor neurons regulate Peyer’s patch microfold cells and SFB levels to mediate Salmonella host defense. Cell 180, 33–49.e22 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bucker R., Schumann M., Amasheh S., Schulzke J. D., Claudins in intestinal function and disease. Curr. Top. Membr. 65, 195–227 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ulluwishewa D., et al. , Regulation of tight junction permeability by intestinal bacteria and dietary components. J. Nutr. 141, 769–776 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chelakkot C., Ghim J., Ryu S. H., Mechanisms regulating intestinal barrier integrity and its pathological implications. Exp. Mol. Med. 50, 1–9 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Hernandez V., Quiros M., Nusrat A., Intestinal epithelial claudins: Expression and regulation in homeostasis and inflammation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1397, 66–79 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Volynets V., et al. , Assessment of the intestinal barrier with five different permeability tests in healthy C57BL/6J and BALB/cJ mice. Dig. Dis. Sci. 61, 737–746 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woting A., Blaut M., Small intestinal permeability and gut-transit time determined with low and high molecular weight fluorescein isothiocyanate-dextrans in C3H mice. Nutrients 10, E685 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luissint A.-C., Parkos C. A., Nusrat A., Inflammation and the intestinal barrier: Leukocyte–epithelial cell interactions, cell junction remodeling, and mucosal repair. Gastroenterology 151, 616–632 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Sadi R. M., Ma T. Y., IL-1β causes an increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability. J. Immunol. 178, 4641–4649 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jung C., et al. , Yersinia pseudotuberculosis disrupts intestinal barrier integrity through hematopoietic TLR-2 signaling. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 2239–2251 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lugrin J., et al. , Cutting edge: IL-1α is a crucial danger signal triggering acute myocardial inflammation during myocardial infarction. J. Immunol. 194, 499–503 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fielding C. A., et al. , IL-6 regulates neutrophil trafficking during acute inflammation via STAT3. J. Immunol. 181, 2189–2195 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bonavita O., Mollica Poeta V., Massara M., Mantovani A., Bonecchi R., Regulation of hematopoiesis by the chemokine system. Cytokine 109, 76–80 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palmieri V., et al. , Interleukin-33 signaling exacerbates experimental infectious colitis by enhancing gut permeability and inhibiting protective Th17 immunity. Mucosal Immunol. 14, 923–936 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Idriss H. T., Naismith J. H., TNF alpha and the TNF receptor superfamily: Structure-function relationship(s). Microsc. Res. Tech. 50, 184–195 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Capucetti A., Albano F., Bonecchi R., Multiple roles for chemokines in neutrophil biology. Front. Immunol. 11, 1259 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gschwandtner M., Derler R., Midwood K. S., More than just attractive: How CCL2 influences myeloid cell behavior beyond chemotaxis. Front. Immunol. 10, 2759 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dinarello C. A., Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood 87, 2095–2147 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patankar J. V., Becker C., Cell death in the gut epithelium and implications for chronic inflammation. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 543–556 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gram H., The long and winding road in pharmaceutical development of canakinumab from rare genetic autoinflammatory syndromes to myocardial infarction and cancer. Pharmacol. Res. 154, 104139 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arezes J., et al. , Hepcidin-induced hypoferremia is a critical host defense mechanism against the siderophilic bacterium Vibrio vulnificus. Cell Host Microbe 17, 47–57 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Michels K. R., et al. , Hepcidin-mediated iron sequestration protects against bacterial dissemination during pneumonia. JCI Insight 2, e92002 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barnes P. D., Bergman M. A., Mecsas J., Isberg R. R., Yersinia pseudotuberculosis disseminates directly from a replicating bacterial pool in the intestine. J. Exp. Med. 203, 1591–1601 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Visitchanakun P., et al. , Gut leakage enhances sepsis susceptibility in iron-overloaded β-thalassemia mice through macrophage hyperinflammatory responses. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 318, G966–G979 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fang S., Zhuo Z., Yu X., Wang H., Feng J., Oral administration of liquid iron preparation containing excess iron induces intestine and liver injury, impairs intestinal barrier function and alters the gut microbiota in rats. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 47, 12–20 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Porto G., De Sousa M., Iron overload and immunity. World J. Gastroenterol. 13, 4707–4715 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fillebeen C., et al. , Hepcidin-mediated hypoferremic response to acute inflammation requires a threshold of Bmp6/Hjv/Smad signaling. Blood 132, 1829–1841 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rebeil R., Ernst R. K., Gowen B. B., Miller S. I., Hinnebusch B. J., Variation in lipid A structure in the pathogenic yersiniae. Mol. Microbiol. 52, 1363–1373 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chan Y. R., et al. , Lipocalin 2 is required for pulmonary host defense against Klebsiella infection. J. Immunol. 182, 4947–4956 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holden V. I., et al. , Bacterial siderophores that evade or overwhelm lipocalin 2 induce hypoxia inducible factor 1α and proinflammatory cytokine secretion in cultured respiratory epithelial cells. Infect. Immun. 82, 3826–3836 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Saha P., et al. , Bacterial siderophores hijack neutrophil functions. J. Immunol. 198, 4293–4303 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wiener E., Impaired phagocyte antibacterial effector functions in beta-thalassemia: A likely factor in the increased susceptibility to bacterial infections. Hematology 8, 35–40 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mao C. Y., et al. , Double-edged-sword effect of IL-1β on the osteogenesis of periodontal ligament stem cells via crosstalk between the NF-κB, MAPK and BMP/Smad signaling pathways. Cell Death Dis. 7, e2296 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.van der Meer J. W., Barza M., Wolff S. M., Dinarello C. A., A low dose of recombinant interleukin 1 protects granulocytopenic mice from lethal gram-negative infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 1620–1623 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sharma D., Kanneganti T. D., Inflammatory cell death in intestinal pathologies. Immunol. Rev. 280, 57–73 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Al-Sadi R., Ye D., Dokladny K., Ma T. Y., Mechanism of IL-1beta-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability. J. Immunol. 180, 5653–5661 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.National Research Council, Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academies Press, Washington, DC, ed. 8, 2011). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Erben U., et al. , A guide to histomorphological evaluation of intestinal inflammation in mouse models. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 7, 4557–4576 (2014). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the GEO database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE180888).