Abstract

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP) is a rare genetic disease caused by mutations in activin A receptor type I/activin-like kinase 2 (ACVR1/ALK2), a bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) type I receptor, resulting in the formation of extraskeletal or heterotopic ossification (HO) and other features consistent with premature aging. During the first decade of life, episodic bouts of inflammatory swellings (flare-ups) occur, which are typically triggered by soft tissue trauma. Through an endochondral process, these exacerbations ultimately result in skeletal muscles, tendons, ligaments, fascia, and aponeuroses transforming into ectopic bone, rendering movement impossible. We have previously shown that soft tissue injury causes early FOP lesions characterized by cellular hypoxia, cellular damage, and local inflammation. Here we show that muscle injury in FOP also results in senescent cell accumulation, and that senescence promotes tissue reprogramming toward a chondrogenic fate in FOP muscle but not wild-type (WT) muscle. Using a combination of senolytic drugs we show that senescent cell clearance and reduction in the senescence associated secretory phenotype (SASP) ameliorate HO in mouse models of FOP. We conclude that injury-induced senescent cell burden and the SASP contribute to FOP lesion formation and that tissue reprogramming in FOP is mediated by cellular senescence, altering myogenic cell fate toward a chondrogenic cell fate. Furthermore, pharmacological removal of senescent cells abrogates tissue reprogramming and HO formation. Here we provide proof-of-principle evidence for senolytic drugs as a future therapeutic strategy in FOP.

Keywords: CELLULAR SENESCENCE, FIBRODYSPLASIA OSSIFICANS PROGRESSIVA, HETEROTOPIC OSSIFICATION, MUSCLE INJURY, SENOLYTICS

Introduction

Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP; MIM #135100) is a severely disabling genetic condition recognized by congenital malformation of the first toes, progressive heterotopic ossification (HO), and accelerated features of tissue and organ aging.(1–3) Before the second decade of life, episodes of painful soft tissue swellings (ie, flare-ups) begin to occur and are frequently triggered by trauma, intramuscular injections (especially vaccinations), viral illness, muscular overstretching, falls, or muscle fatigue.(4,5) These flare-ups cause skeletal muscles, tendons, ligaments, fascia, and aponeuroses to transform into HO, ultimately resulting in cumulative and permanent immobility. Classic FOP is caused by a recurrent activating mutation (617G>A; R206H) in ACVR1/ALK2, herein noted as ACVR1R206H.(6) Individuals with FOP variants also have heterozygous ACVR1 missense mutations in conserved amino acids. Clinical evaluation suffices to diagnose FOP, but confirmatory genetic testing can be helpful in atypical presentations. Most cases of FOP are sporadic but a small number of inherited FOP cases show germline transmission in an autosomal dominant pattern.(6) Although progressive HO remains the sine qua non of FOP, clinical findings beginning in early adulthood recapitulate certain aspects of accelerated aging and have recently been described.(3)

In FOP, plausible mechanisms for production of a progeroid phenotype include injury-induced cellular senescence and unregulated activin A signaling through the mutant bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) signaling pathway.(7,8) Injury-induced senescent cell accumulation, as occurs in muscle, has recently been reported(9,10) and muscle injury is a common precipitant of episodic flare-ups in FOP.(1,2) Activin A–mediated aberrant signaling through the BMP signaling pathway has been suggested in a variety of pathological conditions shared between aging and FOP, including osteoarthritis, neurodegeneration, sarcopenia, and others (discussed in(3)). In addition, activin A is a component of the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP)(11,12) and ACVR1R206H is tremendously sensitive to BMP pathway signaling.(13) Accordingly, injury-induced senescence may lead to increased availability of activin A, amplifying BMP pathway signaling in FOP through activating mutations in ACVR1R206H and contributing to the initiation of flare-ups and susceptibility to accelerated age-related changes.(3)

Senescent cells may have several putative roles in the actuation and propagation of HO in FOP and so agents that selectively target them may be therapeutic candidates for clinical intervention. Pharmaceutical and nutraceutical compounds that kill senescent cells (ie, senolytics) were discovered as inhibitors or antagonists of pro-survival (eg, anti-apoptotic) networks in senescent cells.(14) A large number of senolytic drugs have already been described, proven to effectively delay or alleviate multiple age-associated disorders in preclinical models, and are currently being assessed in clinical trials.(11,15) Here we show the potential use of senolytic drugs in FOP as a novel therapeutic strategy to mitigate injury-induced flare-ups using two mouse models of FOP, by inhibiting tissue reprogramming from a myogenic to chondrogenic fate and abrogating subsequent endochondral HO.

Subjects and Methods

Patient samples

A patient underwent a diagnostic biopsy for a presumptive neoplasm, before the definitive diagnosis of FOP. Biopsy specimens were obtained from superficial and deep back masses that were later determined to be acute FOP lesions. Normal muscle tissue was obtained from surgical waste from the corresponding anatomic sites of an age- and sex-matched unaffected individual. Tissue samples were acquired under institutional review board approval.

Animal models

Approval for all animal experiments was obtained from the Mayo Clinic Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Animals were housed in our facility at 23°C to 25°C with a 12-hour light/dark cycle and were fed with standard laboratory chow (PicoLab Rodent Diet 20 #5053; LabDiet, St. Louis, MO, USA) with free access to water. A transgenic FOP mouse model containing a constitutively active (ca)ACVR1 allele flanked by loxP sites (caACVR1; Acrv1Q207D mice) was used for most experiments.(16) A second FOP mouse model (Acvr1R206H) containing an Acvr1 allele flanked by loxP sites was the generous gift of the International FOP Association (https://www.ifopa.org/fop_mouse_model_now_available_to_researchers). One model produces more robust HO and less dystrophic calcification (Q207D; nonphysiological) than the other (R206H; classic, physiological). A 0.9% NaCl solution containing adenovirus-Cre (5 × 1010 genome copies per mouse) was used to induce expression of ACVR1. Cardiotoxin (CTX; 10mM; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used to induce an injury/inflammatory response by injection (100 μL total volume) into the left hind limb musculature of mice from both models at 3 weeks of age. Tissues were recovered at 1, 2, 5, 7, and 14 days after CTX injection. At 14 days after CTX injection, 100% of animals reproducibly form HO at the injection site. Animals were randomly assigned to control or treatment groups. Wild-type (WT) mice littermates were used as controls. A cocktail of the senolytics dasatinib (D) and quercetin (Q) (D, 5 mg/kg + Q, 50 mg/kg) was administered on the indicated days by oral gavage, with vehicle as the control. Using the wire-grasp test, mobility in the left hind limb of mice was assessed by observation of their ability to grasp a wire using all four limbs.(16) Unimpaired mice grasp the wire with all four limbs (simultaneously), whereas mice with impaired mobility of a joint can only grasp the wire with three limbs.

Tissue harvesting and processing

For animal models, the hindlimb musculature was dissected and muscle tissue was processed by standard techniques, including formalin fixation and paraffin-embedding, or frozen, and then cut cross-sectionally (5-μm sections) at a perpendicular angle to the longitudinal axis of the belly of the muscle. The area of CTX injury within 5 days of injection was identified histologically by lymphocytic infiltration and by muscle necrosis. More than 5 days post-CTX injury, regions of interest (ROIs) were identified histologically by fibrosis, chondrogenesis, endochondral bone formation, or by gross structural deformation (if present). After identification of ROIs, consecutive paraffin or frozen sections (≥10) were examined by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and immunohistochemistry (IHC), or staining with a colorimetric substrate for senescence-associated β-galactosidase activity, respectively. For human muscle tissue, consecutive tissue sections through each of the muscle biopsies were evaluated and multiple sections were sampled within each tissue piece. For both mouse and human tissue, quantification of positively stained cells was performed at multiple sectional depths in each sample.

Micro–computed tomography

Micro–computed tomography (μCT) imaging of mice was performed using a Scanco VivaCT 40 device (Brüttisellen, Switzerland) to determine HO volume and obtain a two-dimensional (2D) image of the medial sagittal plane (source voltage, 55 kV; source current, 142 mA; isotropic voxel size, 10.5 mm). Bone versus “nonbone” was distinguished by upper and lower thresholds of 1000 and 150 Hounsfield units, respectively.

Cells and cell culture

Primary myoblasts were isolated as described(17) and grown on Matrigel-coated dishes with 20% serum, chicken embryo extract, and fibroblast growth factor, at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2. C2C12 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC CRL-1772; Manassas, VA, USA) and were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Life Technologies, Inc., Grand Island, NY, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Life Technologies) and 100 U/mL penicillin and streptomycin (WELGENE Inc., Gyeongsan-si, South Korea) at 37°C in humidified air with 5% CO2. C2C12 cells were made senescent by treatment with 600μM H2O2 for 2 hours in cell-specific growth medium (DMEM + 10% FBS) and after incubation in growth medium for 4 days, trypsinized, split at a 1:2 ratio, and then the entire process repeated a second time.(18) Treated cells were washed three times in growth medium before seeding in transwells. A transwell system (Corning Transwell Multiple Well Plate with Permeable Inserts; Corning, Corning, NY, USA) was used in co-culture experiments. Briefly, FOP or WT myoblasts were seeded at the bottom of a cell culture well (10,000 cells/cm2) and senescent cells were seeded on top of a transwell (5000 cells/cm2). Senescent cells are separated from the myoblasts by a microporous membrane allowing soluble factors produced by senescent cells to condition the medium surrounding the myoblasts.

The isolation and use of SHED cells have been previously described. SHED cells are Tie2-positive connective tissue progenitor cells established from human deciduous teeth and when isolated from FOP patients have the identical stoichiometry and genomic location of their mutations.(16,19) SHED cell strains were established from subjects with FOP and unaffected controls (age- and sex-matched). To minimize variability in SHED cell strains based on donor heterogeneity, only SHED cell strains were used that expressed the median ID1 gene expression among FOP and control (unaffected) donors.(13,16) For analyses, SHED cells were plated at 1 × 104 cells/cm2 in α minimum essential medium (αMEM)/10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and grown under standard conditions in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37°C.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-βgal) is a marker to identify senescent cells.(14) The SA-β-Gal assay was performed on tissue sections at the indicated days after CTX injection or on cells made senescent for co-culturing in the transwell system using a standard staining kit (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA; Catalog# 9860S). For analysis, 100 cells were quantified per low power field (LPF) and approximately eight LPFs were analyzed per 5 μm tissue section. Quantification was performed using a Nikon Eclipse CiL Microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) with NIS-Elements Imaging software, NIS-Elements AR 5.02.00 with extended depth of focus (EDF) view.

Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA from cultured cells or muscle tissue was isolated using RNeasy Mini Columns (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA, USA). For muscle tissue, a 10-mm region surrounding the site of CTX injection was excised and homogenized. The cDNA was generated from mRNA using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems by Life Technologies, Foster City, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions and RT-qPCR was performed by standard procedures.(13,16) The following forward (F) and reverse (R) murine (Mu) and human (Hu) primers were used:

Mu GAPDH FTGAAGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTGGC

Mu GAPDH RCATGTAGGCCATGAGGTCCACCAC

Hu ID1 FAGTGGTGCTTGGTCTGTCG

Hu ID1 RGCTCCTTGAGGCGTGAGTAG

Hu 18 s FATCCCTGAAAAGTTCCAGCA

Hu 18 s RCTGCTTTCCTCAACACCACA

Mu Myo G FCAACCAGGAGGAGCGCGATCTCCG

Mu Myo G RGCTGGGTGTTAGCCTTATGTGAATGG

Mu Sox2 FGCACAACTCGGAGATCAGCAA

Mu Sox2 RCTCGGTCTCGGACAAAAGTTTC

Mu Nanog FAGTGGAGTATCCCAGCATCCA

Mu Nanog RTCCAGATGCGTTCACCAGATAG

Mu OCT4 FTCTTTCCACCAGGCCCCCGGCTC

Mu OCT4 RTGCGGGCGGACATGGGGAGATCC

Mu Sox9 FGCGTGCAGCACAAGAAAGAC

Mu Sox9 RTCCGTTCTTCACCGACTTCCT

Mu Aggrecan FCCTGCTACTTCATCGACCCC

Mu Aggrecan RAGATGCTGTTGACTCGAACCT

Mu Col2a1 FCGAGTGGAAGAGCGGAGACTA

Mu Col2a1 RGAAAACTTTCATGGCGTCCAA

Mu Myf5 FCGGCATGCCTGAATGTAACAG

Mu Myf5 RAGAGAGGGAAGCTGTGTC T

Mu Desmin FTGGAATACCGACACCAGATCCA

Mu Desmin RCTGCCTCATCAGGGAGTCGTT

Mu MRF4 FAAGTGTTTCGGATCATTCCAG

Mu MRF4 RAAATACTGTCCACGATGGAAG

Mu Pax3 FGGAAGCAGAAGAAAGCGAGAAA

Mu Pax3 RGAGGCTCGCTCACTCAGGAT

Mu Pax 7 FAGACAGGTGGCGACTCCG

Mu Pax 7 RCTAATCGAACTCACTGAGGGCAC

Mu IL-6 FACCACGGCCTTCCCTACTTC

MuIL-6 RTTGGGAGTGGTATCCTCTGTGA

Mu MMP3 FTTGACGATGATGAACGATGGA

Mu MMP3 RGAGCAGCAACCAGGAATAGGTT

Mu MMP13 FTGAGGAAGACCTTGTGTTTGCA

Mu MMP13 RGCAAGAGTCGCAGGATGGTAGT

Mu CCL2 FGTCTGTGCTGACCCCAAGAAG

Mu CCL2 RTGGTTCCGATCCAGGTTTTTA

Mu P15 FAGATCCCAACGCCCTGAAC

Mu P15 RCCCATCATCATGACCTGGATT

Mu P16 FGAACTCTTTCGGTCGTACCC

Mu P16 RAGTTCGAATCTGCACCGTAGT

Mu P19 FGCGATAAGAGAGGGCCATAGC

Mu P19 RCCTGTGGTGGAGATCAGATTCA

Mu P21 FGAACATCTCAGGGCCGAAAA

Mu P21 RTGCGCTTGGAGTGATAGAAATC

Mu P27 FTCCGCCTGCAGAAATCTCTT

Mu P27 RCCAAGTCCCGGGTTAGTTCTT

GraphPad Prism, version 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) was used to generate heat maps of the quantitative RT-PC results.

IHC

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue blocks were sectioned at 5 μm. For P16 immunohistochemistry, the FFPE unstained slides were deparaffinized by standard methods and P16 antibody (Roche Tissue Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) or NANOG antibody (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA) was incubated at a 1:200 dilution or 1:500, respectively, for 18 hours at 4°C. Detection of signal was performed per instructions out-lined in the Vectastain Elite ABC kit (#PK-6101; Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA) and using the DAB Peroxidase Substrate (#PK-4100; Vector Laboratories, Inc.). The colorimetric substrate turns positive cells brown/black; negative cells appear purple/blue. The expression of P16 was considered positive when both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining was identified. For analysis, 100 cells were quantified per LPF and approximately eight LPFs were analyzed per 5-μm tissue section. Quantification was performed using a Nikon Eclipse CiL Microscope (Nikon) with NIS-Elements Imaging software, NIS-Elements AR 5.02.00 with EDF view. Isotype controls were performed for the IHC related to human and animal muscle sections (Fig. S1).

Telomere dysfunction–induced foci assay

The telomere dysfunction–induced foci (TIF) assay was performed on embedded tissue sections after incubation in 0.01M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 95°C for 15 minutes, on ice for 15 minutes, and then washed in water and PBS for 5 minutes each. The TIF assay was performed as described.(20,21) In-depth Z-stacking was used (a minimum of 135 optical slices with 63× objective). The number of TIFs per cell were assessed by manual quantification of partially or fully overlapping (in the same optical slice, Z) signals from the telomere probe and γ-H2AX in z-by-z analysis. Images were deconvolved using a deconvolution algorithm, with blind deconvolution in AutoQuant X3 (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA). TIF+ cells were quantified using FIJI software (an open source image processing package based on ImageJ2 software; NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA; https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/) and defined as having at least one co-localized focus.

Study design and statistical analyses

All experiments were performed with at least three technical and biological replicates, with sample sizes indicated in the figure legends. Data was checked for normality using histograms and all variables tested for skewness and kurtosis. The key primary comparisons were between FOP and control tissues using a two-sample, paired t test with a significance level of 0.05 (two-tailed). In the transwell co-culture model, the key primary comparison was between cells derived from WT and FOP animals using a two-sample t test with a significance level of 0.05 (two-tailed). Based on variability data from previous studies in our laboratory with five mice/group, studies were powered to detect differences between groups of 15% in HO bone volume with 80% power. Two-way ANOVA was used with one or more of the following factors: genotype, drug treatment. Following ANOVA, Tukey’s test was used to adjust for multiple comparisons. Data is represented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). GraphPad Prism, version 8, was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Muscle injury induces senescent cells in Acvr1Q207D mice and senescent cells exist in biopsied FOP lesional tissue

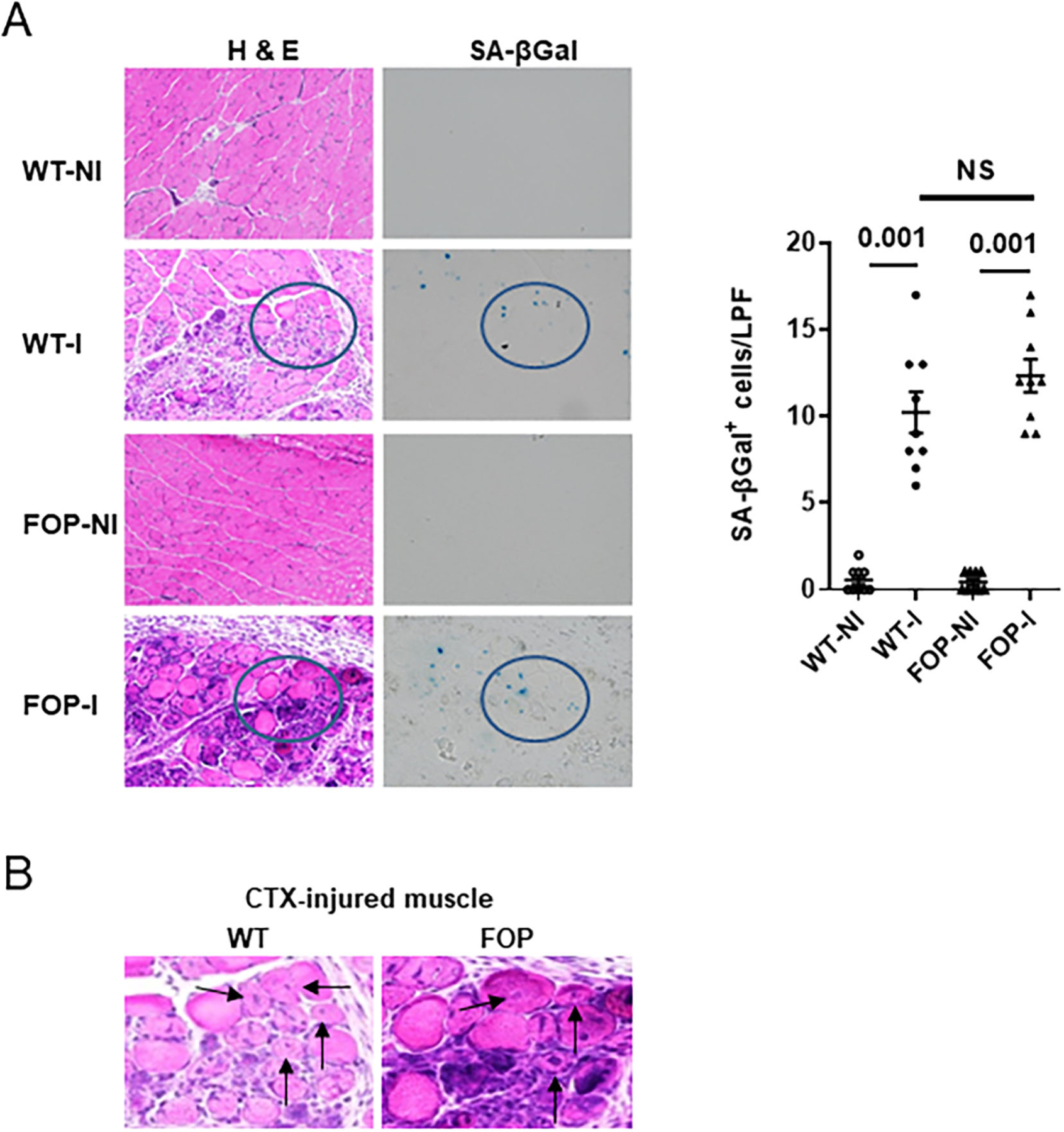

Using CTX injection into the tibialis anterior muscle as a standardized method of creating soft tissue damage, we detected SA-βgal–positive cells 5 days after injury in Acvr1Q207D mice (Fig. 1A,B). The accumulation of senescent cells in injured muscle from Acvr1Q207D mice was robust, exceeding that found in non-injured, vehicle-injected muscle from WT or Acvr1Q207D mice by over 12-fold (Fig. 1A). Injured muscle from WT mice also accumulated senescent cells after injury. Thus, although there is no difference in SA-β-Gal+ cells between injured WT and FOP muscle tissue (Fig. 1), there is, in fact, quite a large difference between injured and uninjured muscle tissue, whether derived from WT or FOP muscle tissue.

Fig 1.

Muscle injury-induced senescence. (A) H&E as well as senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-βgal) staining of the tibialis anterior muscle from WT and a FOP mouse model (Q207D) is shown 5 days after vehicle injection (NI) or I. Quantification of SA-βgal+ cells is shown (right panel; n = 9 animals). LPF (original magnification ×200); p values are indicated among comparison groups. (B) CTX-induced muscle damage 5 days after injury and showing mononuclear infiltration and centralized muscle cell nuclei (arrows). These are taken from within circular insets shown in A.I = injury by cardiotoxin injection; LPF = low-power field; NI = no injury; NS = not significant; SA-βgal = senescence-associated β-galactosidase; WT = wild-type.

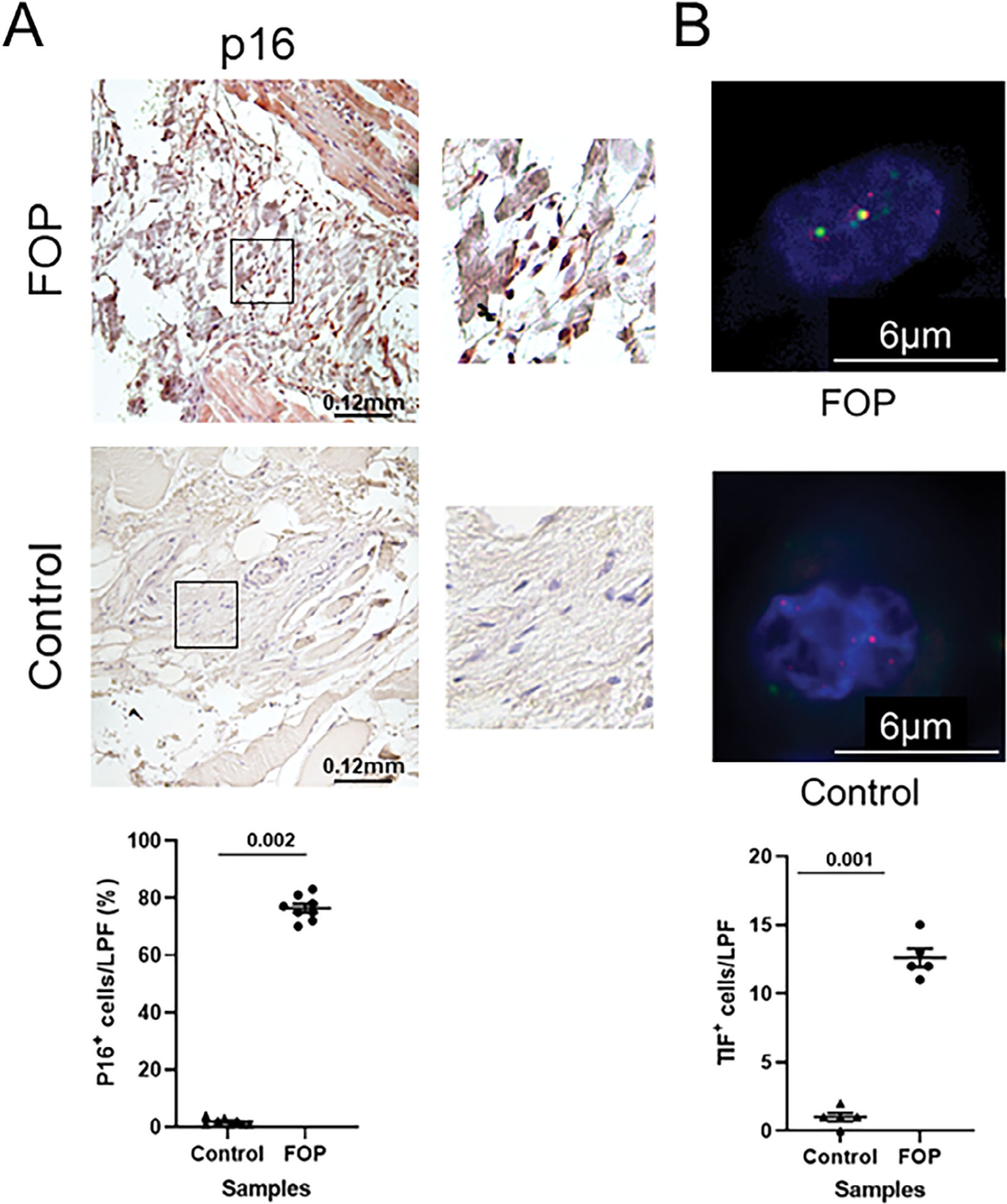

Importantly, senescent cells were identified in biopsied lesions from an FOP patient (Fig. 2), supporting our hypothesis that senescent cells accumulate in early FOP lesions. In this experiment, senescent cells were detected by two markers associated with cellular senescence, P16 (Fig. 2A) and dysfunctional telomeres (Fig. 2B), the latter detected by co-localization of the DNA damage protein γ-H2AX with the telomeric DNA. After quantification of each marker in multiple tissue sections from FOP and control biopsies, affected (FOP) but not unaffected tissue showed major senescent cell burden.

Fig 2.

Identification of senescent cells in biopsied FOP lesional tissue. (A) Detection of P16+ cells by immunohistochemistry in FOP (top) and control (middle) muscle tissue sections is shown with quantification of tissue sections (bottom; n = 8 sections). (B) Detection of senescent cells by TIF assay in FOP and control tissue sections (n = 5 sections). Green, γH2AX; red, telomere; yellow, TIF. For quantification, each point in the graphs depicts the percentage of senescent cells (P16 IHC) or absolute number of senescent cells (TIF assay) per LPF (original magnification ×200) from control (unaffected) or FOP tissue sections derived from the individual donor. On average, 100 cells were quantified per LPF and approximately eight LPFs were analyzed per tissue section for p16 IHC; 50 cells were quantified per LPF and five LPFs were analyzed per section for TIF. IHC = immunohistochemistry; LPF = low power field; TIF = telomere dysfunction–induced foci.

Senescent markers and SASP factors are expressed in injured muscle of Acvr1Q207D mice

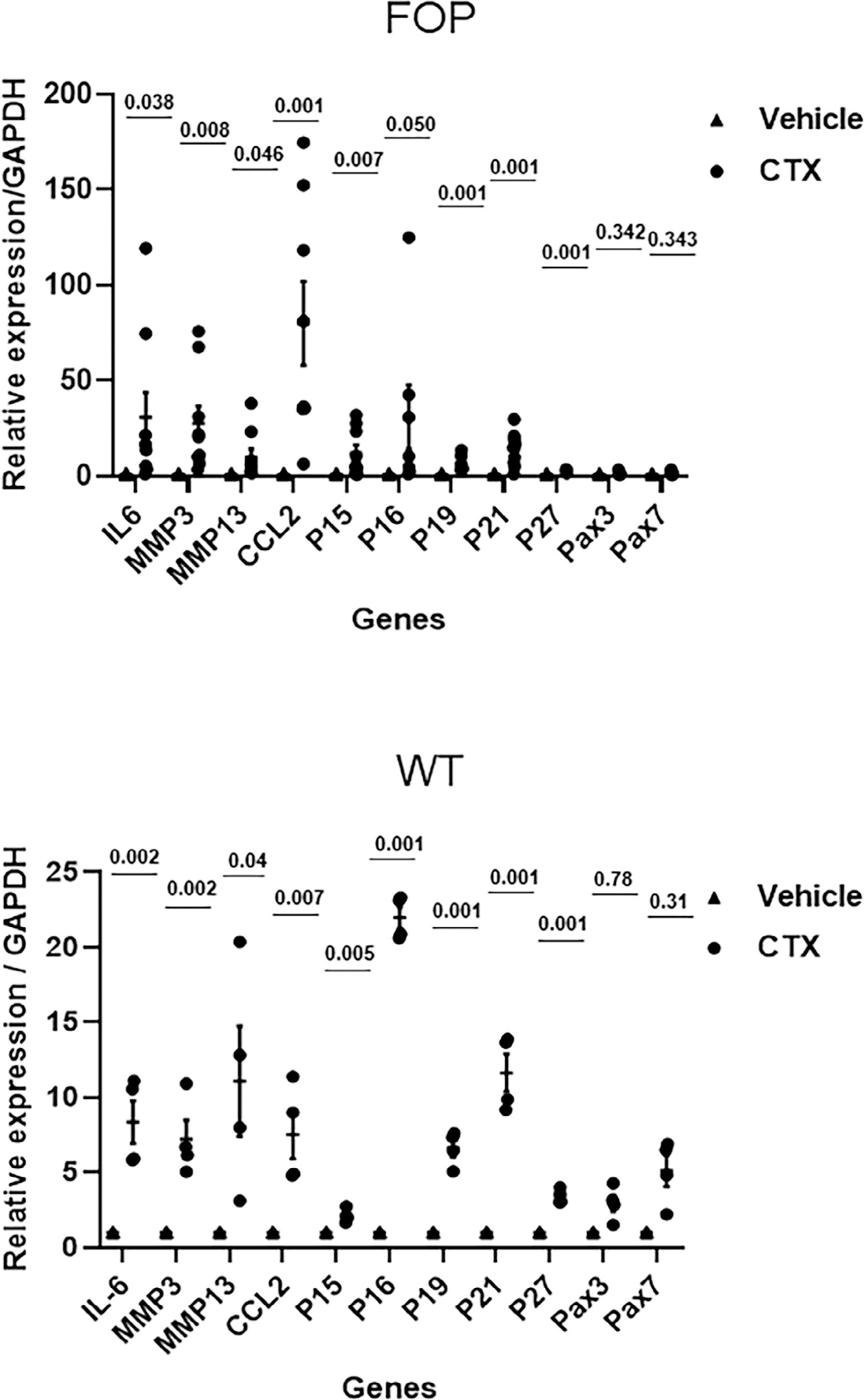

We also measured changes in gene expression among markers of senescence, components of the SASP, and some muscle-related genes in injured FOP and WT mouse muscle tissue 5 days after CTX injury (Fig. 3). Genes associated with senescence, including those for p15 and p16, were substantially elevated in CTX-injured FOP and WT muscle tissue compared to uninjured (vehicle) controls. Among components of the SASP, interleukin 6 (IL-6), matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) were markedly overexpressed in CTX-injured FOP and WT muscle tissue relative to vehicle controls (Fig. 3). Myogenesis-related gene expression (ie, Pax 3, Pax7) did not significantly differ on day 5 postinjury, although there was a trend toward increased expression in injured WT muscle.

Fig 3.

Upregulated senescent markers and SASP factors 5 days after injury of the tibialis anterior muscle by CTX injection. Upper panel: FOP mouse model (Acvr1Q207D). Lower panel: WT. Values of p are indicated. Biological replicates: n = 4 animals/WT group; 6 animals/FOP group. CTX = cardiotoxin; SASP = senescence associated secretory phenotype.

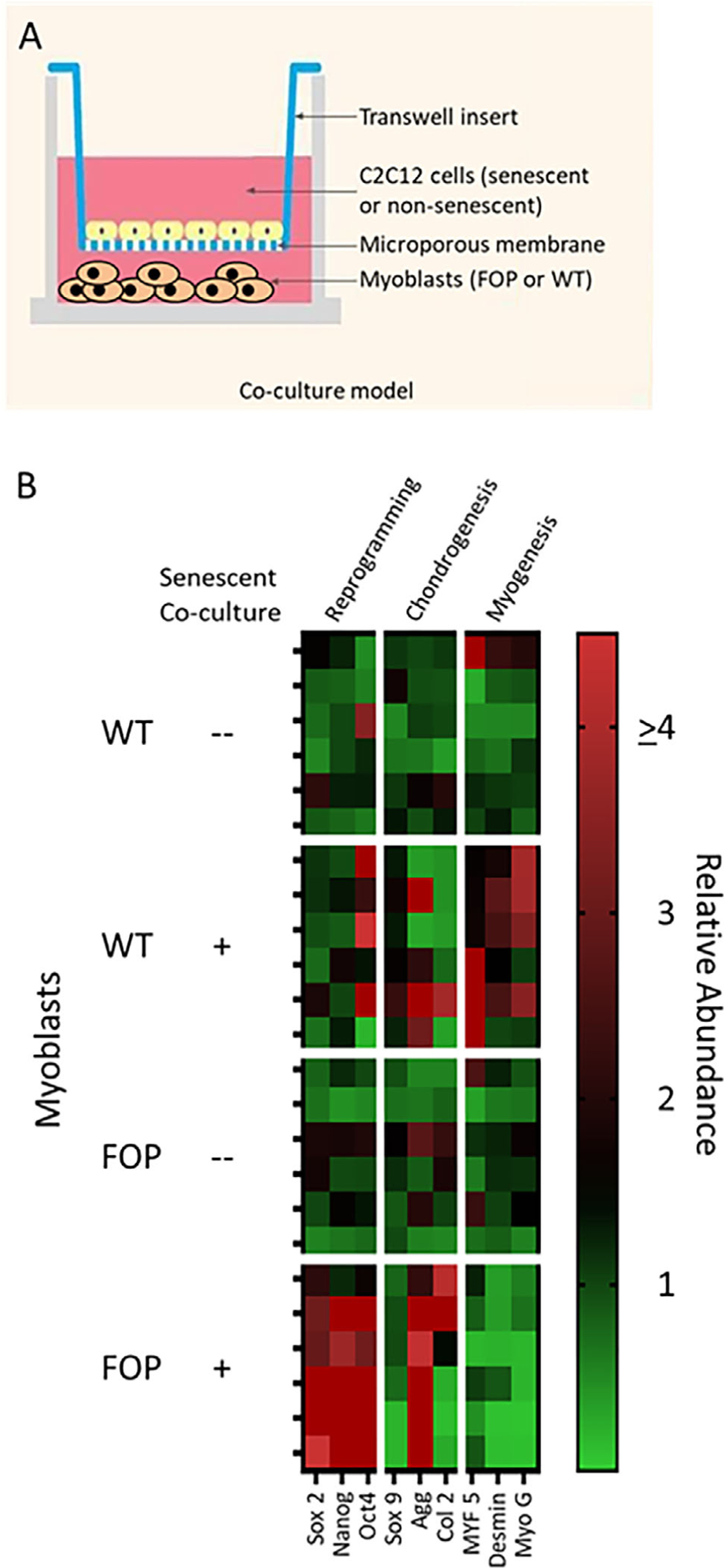

Cellular reprogramming and chondrogenesis occur in FOP myoblasts in the presence of the SASP

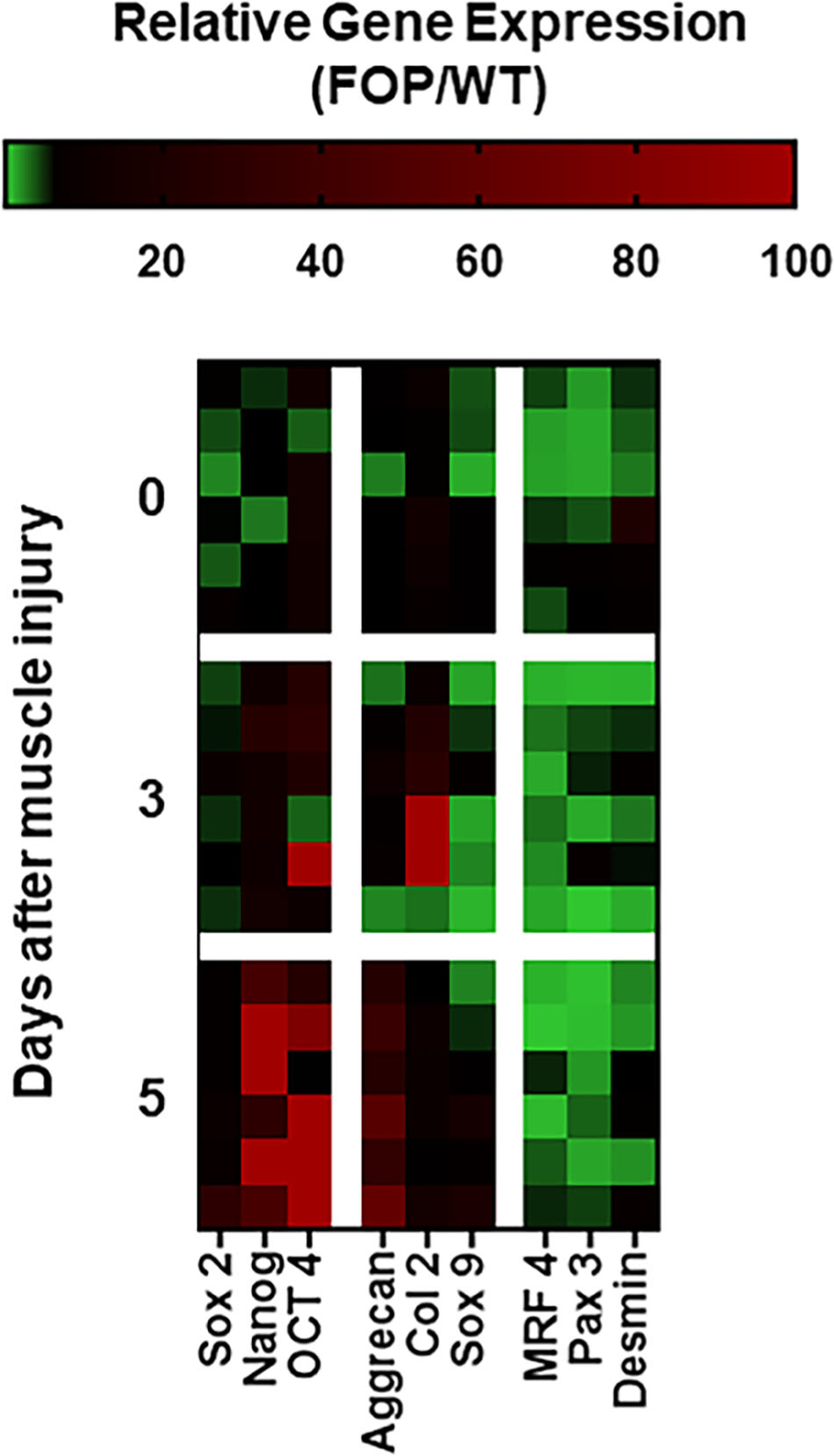

Growing evidence suggests that injury permits in vivo reprogramming in skeletal muscle and that this process can be supported and advanced by senescent cell accumulation at or near the site of injured tissue.(9) We developed an in vitro model for evaluation of the SASP on tissue reprogramming after muscle injury. The model is a transwell co-culture system where FOP or WT myoblasts are seeded at the bottom of a cell culture well and senescent cells are seeded on top of a transwell (Fig. 4A). The senescent cells are separated from the myoblasts by a microporous membrane that allows soluble factors produced by senescent cells (ie, the SASP) to condition the medium surrounding the myoblasts. Figure 4B shows that in the presence of senescent cell co-culture in this transwell model, FOP myoblasts (but not WT myoblasts) preferentially express genes consistent with reprogramming (eg, Nanog) and chondrogenesis (eg, aggrecan). In contrast, WT myoblasts are directed toward a myogenic fate in the presence of the SASP (eg, upregulation of MYF 5). In the absence of the SASP (ie, non-senescent cells contributing soluble factors), neither FOP nor WT myoblasts express genes consistent with reprogramming or differentiation (Fig. 4B). Quantitative RT-PCR data related to Fig. 4B is shown in Fig. S2.

Fig 4.

(A) Myoblasts from an FOP mouse model (Acvr1Q207D) or WT animals were assessed for responses to secretory factors produced by senescent (ie, the SASP) or non-senescent cells in an in vitro co-culture system. (B) Reprogramming and chondrogenesis occur in FOP myoblasts in the presence of the SASP in an in vitro co-culture model. WT myoblasts undergo initiation of myogenesis in the presence of the SASP. Heat mapping shows the relative expression of genes quantified by qRT-PCR, each row representing a biological replicate (n = 6 per condition; ie, myoblasts derived from uninjured FOP or WT animals and co-cultured with senescent or non-senescent cells). SASP = senescence associated secretory phenotype; WT = wild-type.

Muscle injury in Acvr1Q207D mice promotes tissue reprogramming toward a chondrogenic fate

We also used an FOP mouse model to collect data on tissue reprogramming and differentiation after injury in vivo. Figure 5 illustrates that FOP muscle tissue injured in vivo undergoes reprogramming toward a chondrogenic fate. Compared to control (uninjured) muscle tissue from FOP and WT mice, injured FOP muscle has a gene expression profile consistent with tissue reprogramming as early as 3 days after CTX injury (Fig. 5). By day 5 after FOP muscle injury, there is a >20-fold induction of reprogramming (eg, Nanog, Oct4) and chondrogenesis-related (eg, aggrecan) genes (Fig. 5). These data indicate that tissue reprogramming is in close temporal proximity to chondrogenesis in FOP. Quantitative RT-PCR data related to Fig. 5 is shown in Fig. S3.

Fig 5.

Muscle injury in an FOP mouse model (Acvr1Q207D) promotes tissue reprogramming toward a chondrogenic fate. Heat mapping shows gene expression profiles by qRT-PCR in injured FOP muscle tissue relative to WT. Each row represents a biological replicate (n = 6 animals/time point). Days after muscle injury are indicated. Day 0 is the non-injured, vehicle-injected control. WT = wild-type.

Senolytics reduce senescent cell burden and level of reprogramming factors

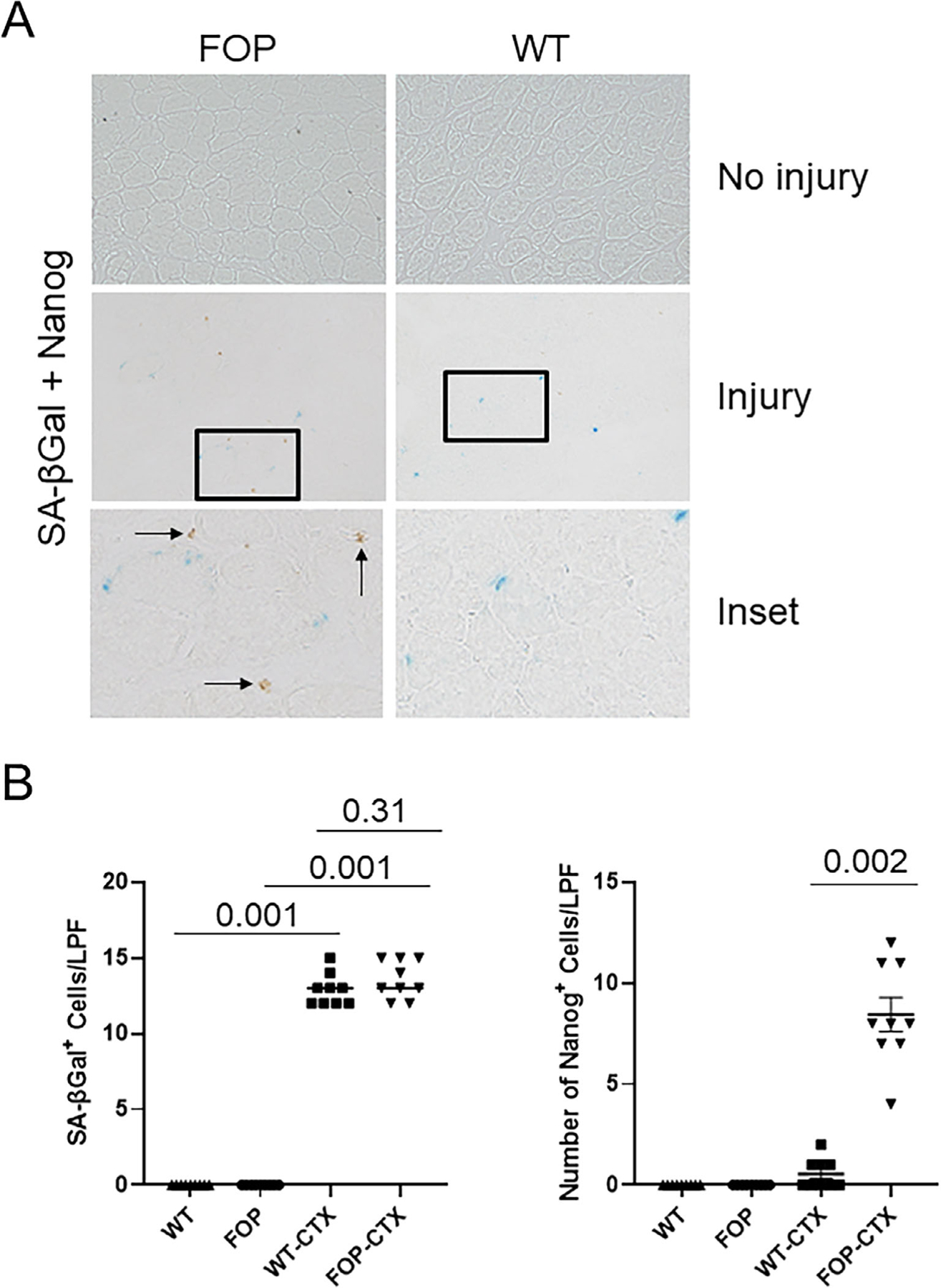

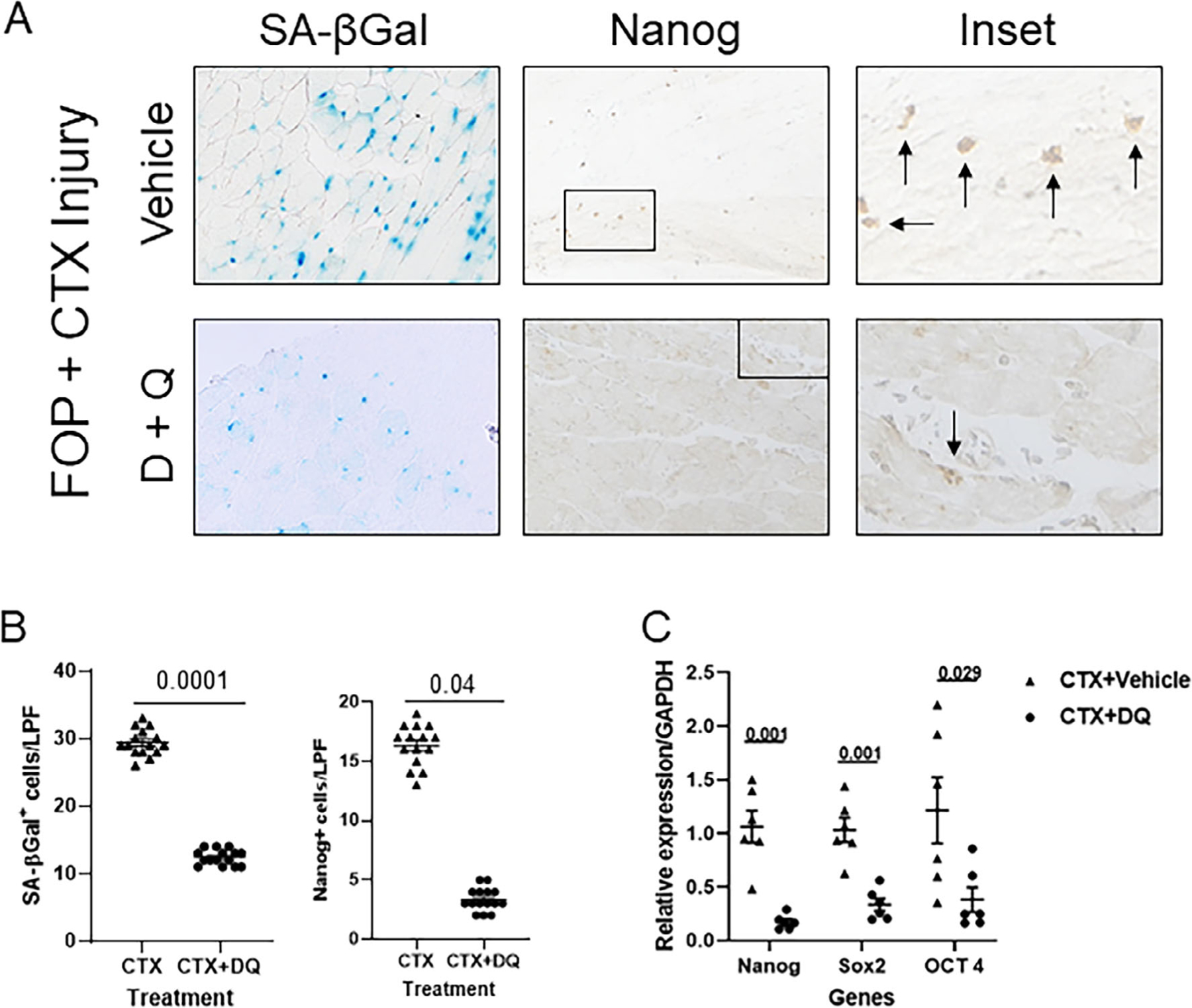

Importantly, upregulation of reprogramming factors occurs in the same early FOP lesions where senescent cells accumulate (Fig. 6A,B) and senolytics reduce both senescent cell burden and level of reprogramming factors (Fig. 7A–C). In addition to SA-β-Gal+ cells, several senescence-associated genes, including p16 and components of the SASP, are diminished after D+Q treatment of injured muscle (Fig. S4). Taken together, these results suggest that it is not the relative number of senescent cells, but also the tissue reprogramming response to the SASP and muscle injury (chondrogenic rather than myogenic) that is aberrant in FOP.

Fig 6.

Muscle injury induces senescent cell accumulation and the tissue reprogramming factor Nanog in FOP. (A) After CTX-induced muscle injury, both WT and FOP (Q207D) mice accumulate SA-βGal+ senescent cells (blue) but only injured FOP muscle tissue demonstrates substantial numbers of Nanog+ cells (brown; see arrows, insets) in the same areas of senescent myoblasts. (B) Quantification of SA-βGal+ cells and Nanog+ cells in uninjured and injured muscle. Compared to FOP, the presence of Nanog+ cells in injured WT muscle is negligible (right; n = 9). Data shown in all panels are from muscle tissue 5 days after CTX injury. No injury means vehicle injection. LPF (original magnification ×200); *p < 0.05. CTX = cardiotoxin; LPF = low power field; SA-βGal = senescence-associated β-galactosidase; WT = wild-type.

Fig 7.

The combination of dasatinib plus quercetin (D+Q) reduces senescent cell burden, upregulation of the reprogramming factor Nanog, and accumulation of Nanog+ cells after muscle injury in a FOP mouse model (Acvr1Q207D). (A) D+Q reduces the presence of SA-βGal+ senescent myoblasts (blue) and Nanog+ cells (brown; see arrows, insets) in injured FOP muscle. (B) Quantification of SA-βGal+ senescent myoblasts (left; n = 15 animals) and Nanog+ cells (right; n = 15 animals) in tissue sections of injured muscle. (C) Quantification of reprogramming factors in injured FOP muscle tissue by RT-PCR (n = 6 animals). Note the reduction of reprogramming factors in FOP mice treated with D+Q. Data shown in all panels are from muscle tissue 5 days after CTX injury. LPF (original magnification ×200); p values are indicated among comparison groups. LPF = low-power field; SA-βGal = senescence-associated β-galactosidase.

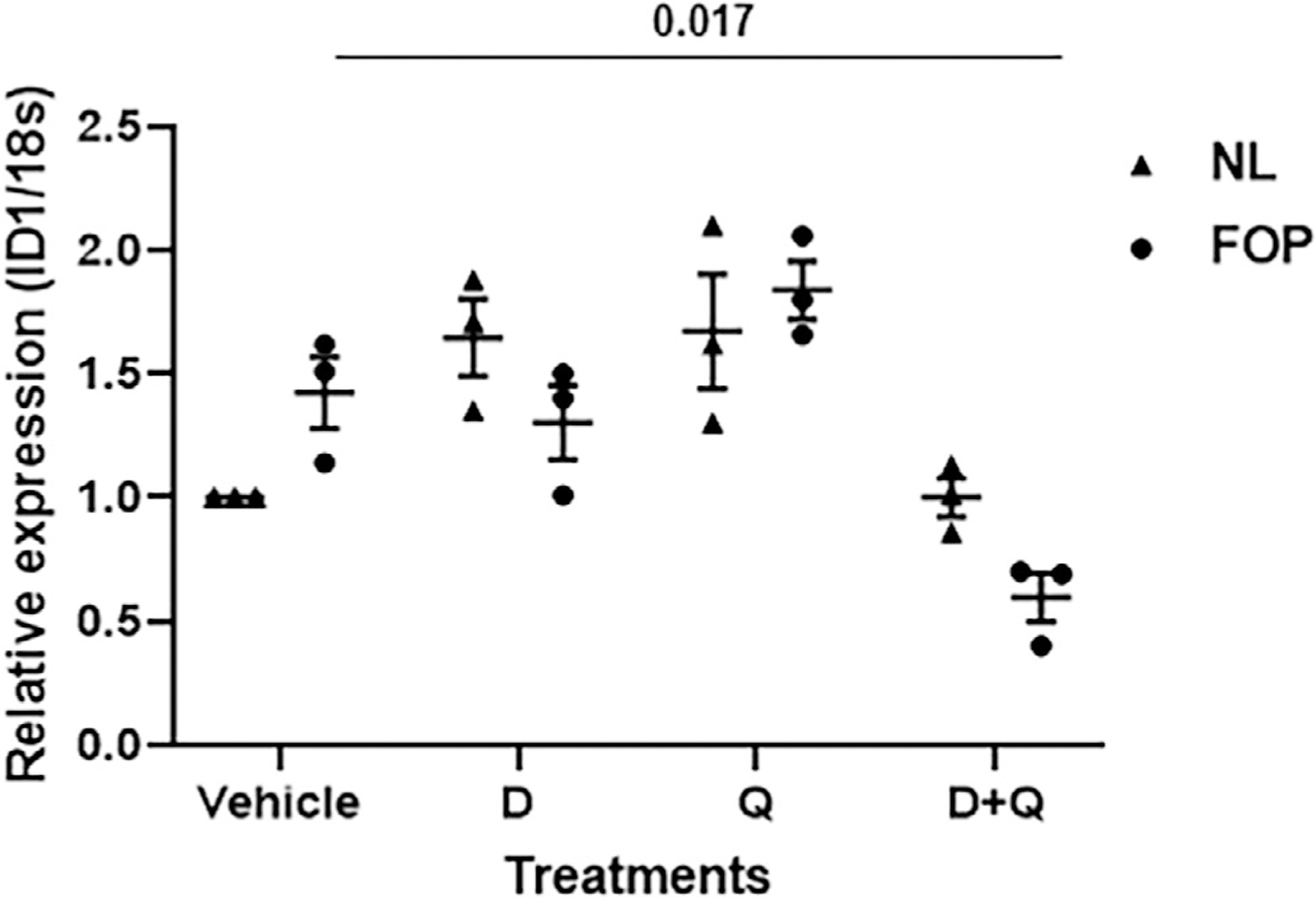

Senolytics reduce basal BMP pathway signaling in FOP stem cells

Compounds that selectively kill senescent cells were originally reported based on their ability to target pro-survival/anti-apoptotic networks in senescent cells.(14) Aberrant BMP pathway signaling, especially in the basal state, is a direct consequence of the ACVR1 gain-of-function mutations in FOP with ID1 as a consistent readout of this activity.(13,16) Figure 8 shows that the senolytic combination of dasatinib and quercetin (D+Q) reduces basal (leaky) BMP pathway signaling in FOP stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED cells), an in vitro model for FOP. Therefore, the potential efficacy of D+Q is not only related to their role as senolytics, but also as agents which in combination directly target the basal activity of the mutated ACVR1 in FOP.

Fig 8.

The combination of dasatinib plus quercetin (D+Q) reduces basal BMP pathway signaling in vitro. Stem cells from human exfoliated deciduous teeth (SHED cells) were treated with D, Q, D+Q, or vehicle and ID1 expression measured by qRT-PCR (n = 3 SHED cell lines/genotype; 3 donors/genotype). NL (unaffected). Values of p are indicated among comparison groups. NL = normal.

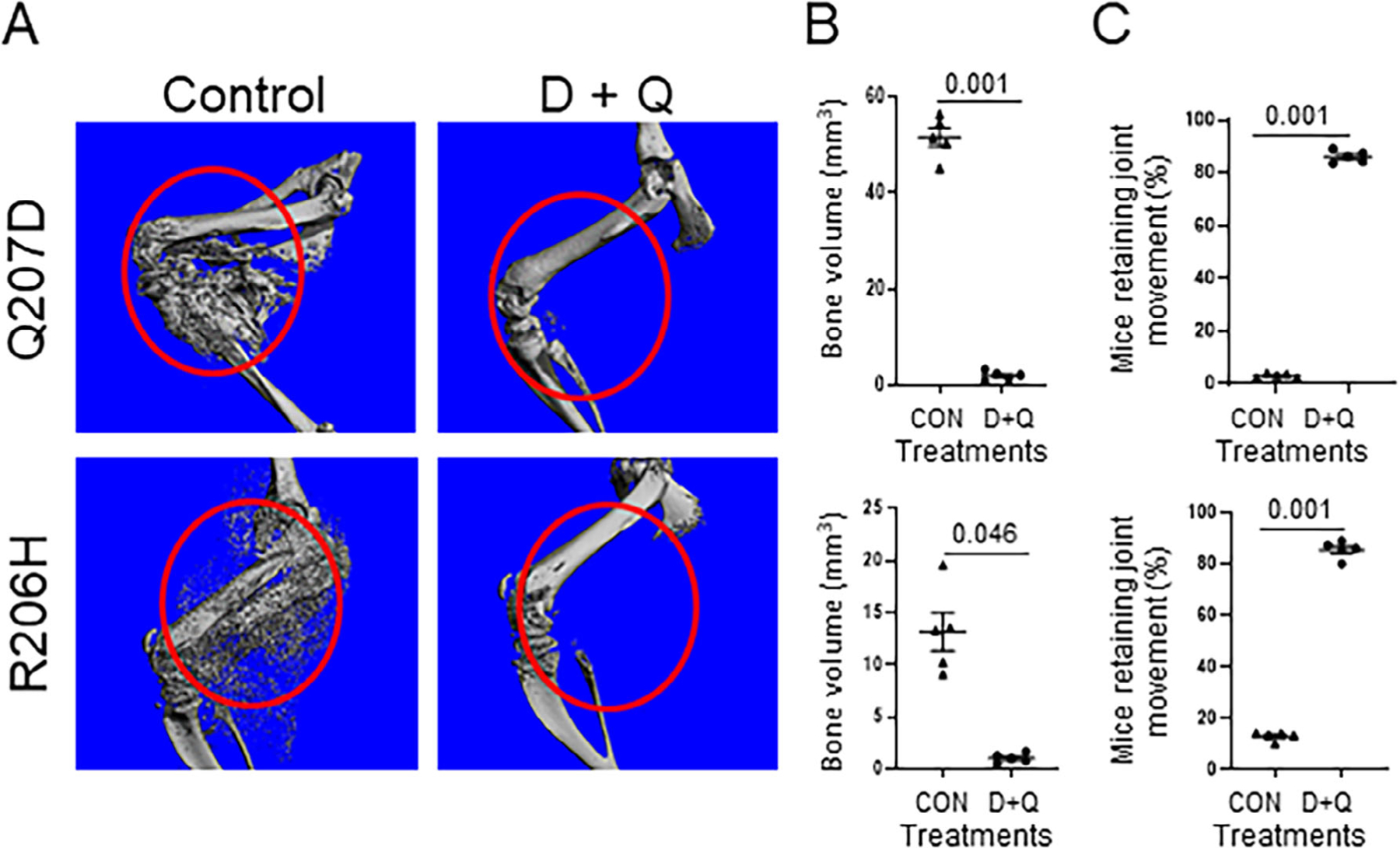

Senolytics ameliorate HO in FOP mouse models

Because our data supported that D+Q reduced BMP pathway signaling in vitro and that senescent cells accumulated after CTX-induced muscle injury (Fig. 1), we tested the efficacy of D+Q in two mouse models of FOP that produce HO by 14 days postinjury, one more robustly (Q207D; nonphysiological) than the other (R206H; classic, physiological) (Fig. 9A). D+Q significantly reduced HO to negligible levels when given as a prophylactic regimen (daily, beginning 2 days prior to CTX injection) (Fig. 9A,B). D and Q, individually, also reduced total HO burden (Fig. S5), but together are synergistic. In light of in vitro data showing that only the combination of D+Q (and not D or Q) reduced BMP pathway signaling (Fig. 8), the in vivo finding that either D or Q alone could decrease HO suggests that their major target is senescence. Furthermore, D+Q reduced senescent cell burden in both FOP models (Fig. 7A, Fig. S6). D+Q in both models preserved joint mobility (Fig. 9C).

Fig 9.

The combination of dasatinib plus quercetin (D+Q) ameliorates HO in two FOP mouse models (Acvr1Q207D and Acvr1R206H). (A) Representative high-resolution imaging of HO by μCT 14 days after CTX muscle injury. (B) Quantification of HO bone volume (n = 5 animals/group). (C) Joint mobility by the functional wire grasp test (n = 5 animals/group). Values of p are indicated among comparison groups.

Discussion

While conducting studies on the efficacy of apigenin-like compounds to reduce BMP pathway signaling in vitro and HO in a mouse model of FOP,(16) we made the serendipitous observation that many of these agents are bioflavonoids that have been described as senolytic drugs. Together with recent findings that senescent cells accumulate at sites of soft-tissue injury and can mediate tissue reprogramming,(9,22) we formulated the hypothesis that injury-induced senescent cells accumulate in FOP lesions, promote reprogramming of tissue-resident stem cells, and shift cell fate from a myogenic to a chondrogenic lineage, thus leading to ectopic endochondral bone formation. Our data confirm both the initial observation and our subsequent hypothesis-driven inquiries.

Currently, there are no approved therapies for FOP, either for the prevention of flare-ups or for their episodic treatment when they occur, although ongoing clinical trials may offer future promise.(23) The likelihood for senolytic drugs to become part of the therapeutic management of FOP seems possible in the near future, both because of our encouraging preclinical data and the availability of senolytics as nutraceuticals or repurposed drugs. Legitimate concerns about adverse events and risks of long-term undesirable outcomes related to senolytics are diminished by the need for infrequent administration, owing to the quick removal of senescent cells and their time to re-accumulation. Our data suggest a way forward for a randomized clinical trial with senolytics for FOP.

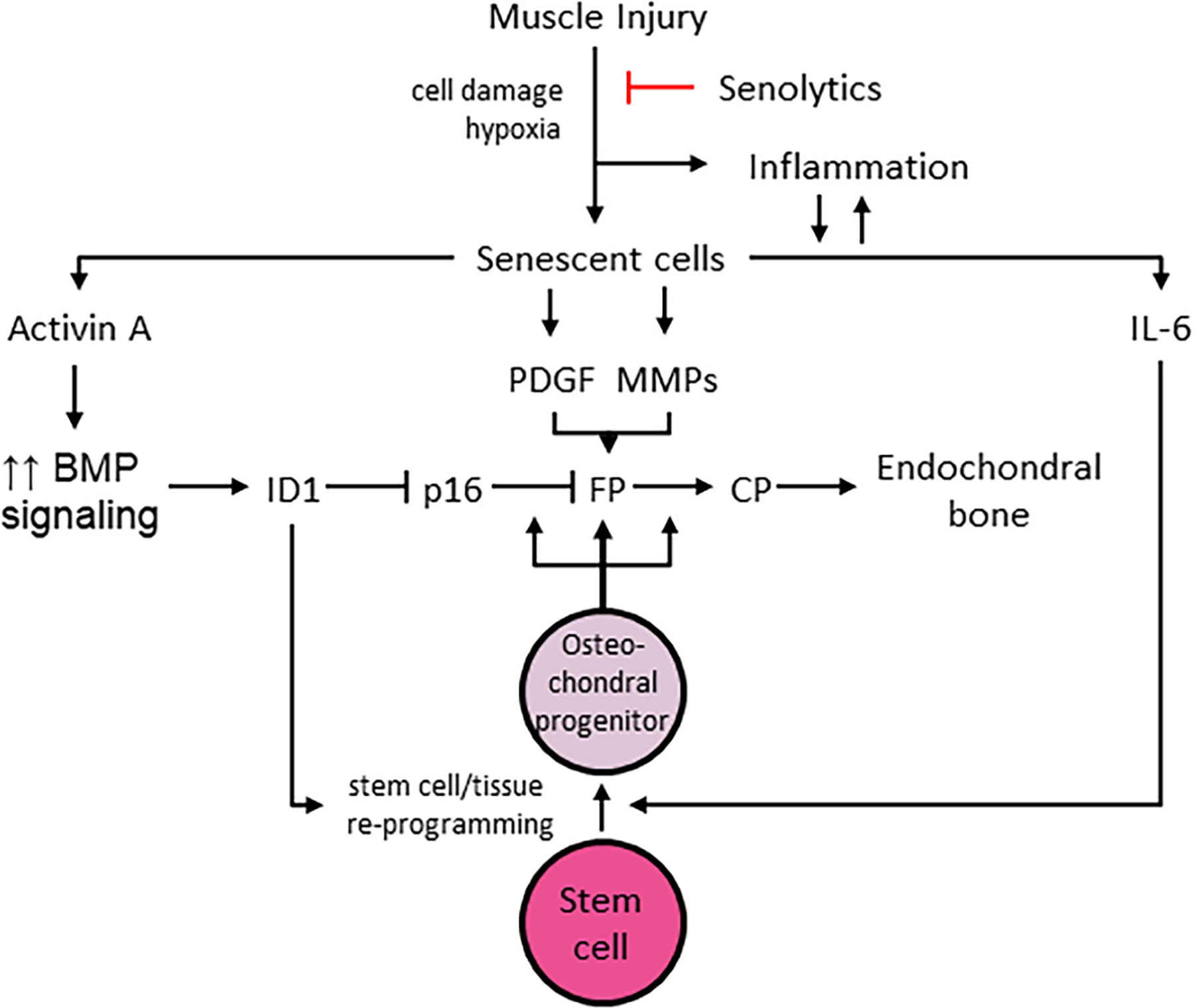

In FOP, injuries due to blunt trauma, viral illness, and muscle overuse can result in acute exacerbations. Tissue damage is caused by microbial and endogenous injury and produces a hypoxic microenvironment.(16,24) Secondary to injury and perhaps other insults, senescent cells accumulate in soft tissues and may initiate and propagate events that amplify BMP pathway signaling and contribute to the reprogramming of stem cells in target tissues (Fig. 10). Senescence is often a response to cellular and other damage resulting in an irreversible cell-cycle arrest with concomitant triggering of the SASP.(25,26) Components of the SASP include factors that directly promote enhanced BMP pathway signaling and stem cell reprogramming, including activin A and IL-6, respectively. It is clear that activin A stimulates BMP pathway signaling in FOP cells, due to activating mutations in the ACVR1 gene.(7,8,13,27,28) We can further hypothesize that in contrast, normal cells, including myoblasts, would respond to activin A quite differently. As described by Hatsell and colleagues,(7) ACVR1, together with type II receptors, binds activin A, but the complex does not stimulate phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8; instead, activin acts as an inhibitor of canonical BMP signaling.

Fig 10.

Proposed schema for role(s) of senescent cell accumulation in injury-induced HO. Other abbreviations as described in the text. CP = connective tissue progenitor cells; FP = fibroproliferation.

In addition to the known effects of IL-6 in tissue reprogramming, FOP cells demonstrate a heightened capacity for induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) generation.(29) In normal cells, iPSC generation is increased by the transduction of mutant ACVR1 or SMAD1 or by the addition of BMP4 early in the reprogramming process. ID genes, transcriptional targets of BMP-SMAD signaling, are critically important for iPSC generation and can inhibit p16/INK4A-mediated cell senescence, a key obstacle to reprogramming.(29) Hence, expansion of the early FOP lesion and stimulation of osteochondral precursor cells may be facilitated by ID1 and other ID genes (Fig. 10). Increased BMP pathway signaling accelerates robust fibroproliferation, perhaps propagated by other components of the SASP, including platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and MMPs (Fig. 10). Reprogrammed stem cells give rise to osteochondral progenitors that promote heterotopic endochondral bone formation in mature FOP lesions (Fig. 10).

We have shown that senescent cells are detectable in animal models of FOP after muscle injury and in lesional biopsies from an FOP patient. We further have shown that senescent cell burden, including the SASP, is pronounced in injured muscle tissue from FOP animal models as well as in WT animals; however, the response to injury is dramatically different between FOP and WT animals. In muscle damaged by acute or chronic injury, transcription factors appear to mediate the reprogramming effect in response to SASP factors, especially IL-6.(9,30) Senescence-mediated reprogramming appears to occur in nearby non-senescent cells in parallel with infiltration of macrophages to clear dying tissue.(9) As part of the SASP, interleukins might have a role in tissue reprogramming in FOP and MMPs may be involved in the early fibrotic response; however, a role for CCL2 is unclear but may be important in the inflammatory reaction to injury. CCL2 is a small molecule that functions as a cytokine to attract monocytes and other immune cells to the inflammatory sites caused by injury or infection.(31,32)

IL-6 and other SASP factors enhance reprogramming by Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM) in non-senescent cells(22) into induced pluripotent stem cells. An association between senescence and OSKM-related reprogramming exists whereby cells that cannot become senescent (ie, those without p16INK4a/ARF) have limited reprogramming capacity.(10,22) Further supporting this relationship, chemical antagonism of NFκB, a key promoter of the SASP, decreases the likelihood of tissue reprogramming in vivo.(10) Conditions of senescent cell accumulation, such as physiological aging and wound healing, have also been associated with OSKM-related reprogramming and induction of dedifferentiation, respectively.(10,22) We have shown here that after injury in FOP, lineage switching from a myogenic to a chondrogenic fate appears to be mediated by tissue reprogramming factors. Conversely, our data support that myoblasts do not have a chondrogenic phenotype under control conditions (eg, WT genotype with or without injury or FOP genotype with no injury).

Currently there is no curative therapy for FOP, but symptomatic treatment using high-dose corticosteroids may ameliorate the painful inflammation and extensive edema often observed in the initial clinical stages that precede ectopic bony lesion formation.(1,33) Anticipatory management is centered on preventative strategies to mitigate the likelihood of falls, pulmonary dysfunction, and viral illnesses. The median estimated life expectancy of an individual with FOP is about 56 years.(34) A majority of patients are non-ambulatory by the age of 30 years and typically die of cardiorespiratory conditions.(34) In FOP, cellular senescence may have several mechanistic roles in HO formation and interventions that target senescence and/or the SASP may represent future therapeutic approaches. Various so-called senotherapeutic compounds have been described, are beneficial in preventing or mitigating many age-onset disorders or syndromes in animal models, and are the focus of study in ongoing clinical trials.(11,15) Their possible clinical usage in FOP represents a unique treatment strategy to lessen the deleterious consequences of trauma-induced flare-ups and that deserves additional evaluation.

We have shown that senescent cell clearance in FOP mice abrogates both the abnormal response to injury and subsequent HO. We also show in an in vitro model of FOP that the senolytic combination of D+Q may also have a slight inhibitory effect on the leaky, basal BMP signaling characteristic of the mutated ACVR1 receptor in FOP. However, based on their known primary targets and use of modified Koch’s postulates, we hypothesize that the major contributory effect of senolytics in HO reduction is related to the removal of senescent cells. D and Q individually are senolytic agents that act on different senescent cell apoptotic pathways(35) and together their effect is synergistic on HO reduction. One explanation for this is that senescence is a major contributor to HO formation in the models we used. Also, we employed modified Koch’s postulates to show that: (i) senescent cells are detectable in conjunction with FOP lesions; (ii) senescent cell accumulation (or the SASP), as in muscle injury, causes tissue reprogramming that propagates lesion formation; and (iii) senescent cell clearance alleviates HO. Our data in two FOP models are very encouraging in that, at least in a prophylactic dosing regimen of D+Q, HO was nearly completely prevented. Because injury-induced senescence is not limited to FOP, there is the opportunity to potentially broaden our findings to idiopathic (ie, nonhereditary) HO.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Radiant Hope Foundation (HW, RJP), P01 AG062413 (RJP), The Robert and Arlene Kogod Professorship in Geriatric Medicine (RJP), the International Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva Association (HW, FSK), the Center for Research in FOP and Related Disorders (FSK), the Ian Cali Endowment for FOP Research, (FSK), and The Isaac and Rose Nassau Professorship of Orthopaedic Molecular Medicine (FSK).

Footnotes

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Conflict of Interests

The authors have no conflicts of interest related to the contents of this paper. RJP and FSK are research investigators for Clementia Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (an Ipsen Company) and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals. RJP and FSK are the current and past presidents, respectively, of the International Clinical Council on FOP.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1.Pignolo RJ, Shore EM, Kaplan FS. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: clinical and genetic aspects. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2011;6:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pignolo RJ, Shore EM, Kaplan FS. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva: diagnosis, management, and therapeutic horizons. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2013;10(Suppl 2):437–448. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pignolo RJ, Wang H, Kaplan FS. Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP): a segmental progeroid syndrome. Front Endocrinol 2020;10: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pignolo RJ, Bedford-Gay C, Liljesthrom M, et al. The natural history of flare-ups in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP): a comprehensive global assessment. J Bone Miner Res 2016;31(3):650–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pignolo RJ, Kaplan FS. Clinical staging of fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP). Bone 2018;109:111–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shore EM, Xu M, Feldman GJ, et al. A recurrent mutation in the BMP type I receptor ACVR1 causes inherited and sporadic fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Nat Genet 2006;38(5):525–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hatsell SJ, Idone V, Wolken DM, et al. ACVR1R206H receptor mutation causes fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva by imparting responsiveness to activin A. Sci Transl Med 2015;7(303):303ra137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hino K, Ikeya M, Horigome K, et al. Neofunction of ACVR1 in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112(50): 15438–15443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiche A, Le Roux I, von Joest M, et al. Injury-induced senescence enables in vivo reprogramming in skeletal muscle. Cell Stem Cell 2017;20(3):407–414.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mosteiro L, Pantoja C, Alcazar N, et al. Tissue damage and senescence provide critical signals for cellular reprogramming in vivo. Science. 2016;354(6315):aaf4445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirkland JL, Tchkonia T, Zhu Y, Niedernhofer LJ, Robbins PD. The clinical potential of Senolytic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65(10):2297–2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu M, Palmer AK, Ding H, et al. Targeting senescent cells enhances adipogenesis and metabolic function in old age. Elife 2015;4:e12997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H, Shore EM, Pignolo RJ, Kaplan FS. Activin A amplifies dysregulated BMP signaling and induces chondro-osseous differentiation of primary connective tissue progenitor cells in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP). Bone 2018;109:218–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhu Y, Tchkonia T, Pirtskhalava T, et al. The Achilles’ heel of senescent cells: from transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 2015;14(4): 644–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL. Aging, cell senescence, and chronic disease: emerging therapeutic strategies. JAMA 2018;320(13):1319–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Lindborg C, Lounev V, et al. Cellular hypoxia promotes heterotopic ossification by amplifying BMP signaling. J Bone Miner Res 2016;31(9):1652–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shahini A, Vydiam K, Choudhury D, et al. Efficient and high yield isolation of myoblasts from skeletal muscle. Stem Cell Res 2018;30: 122–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sugihara H, Teramoto N, Yamanouchi K, Matsuwaki T, Nishihara M. Oxidative stress-mediated senescence in mesenchymal progenitor cells causes the loss of their fibro/adipogenic potential and abrogates myoblast fusion. Aging (Albany NY) 2018;10(4):747–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Billings PC, Fiori JL, Bentwood JL, et al. Dysregulated BMP signaling and enhanced osteogenic differentiation of connective tissue progenitor cells from patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP). J Bone Miner Res 2008;23(3):305–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hewitt G, Jurk D, Marques FD, et al. Telomeres are favoured targets of a persistent DNA damage response in ageing and stress-induced senescence. Nat Commun 2012;3:708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang H, Chen Q, Lee SH, Choi Y, Johnson FB, Pignolo RJ. Impairment of osteoblast differentiation due to proliferation-independent telomere dysfunction in mouse models of accelerated aging. Aging Cell 2012;11(4):704–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mosteiro L, Pantoja C, de Martino A, Serrano M. Senescence promotes in vivo reprogramming through p16INK4a and IL-6. Aging Cell 2018;17(2):e12711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pignolo RJ, Kaplan FS. Druggable targets, clinical trial design and proposed pharmacological management in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs 2020;8(4):101–109. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang H, Behrens EM, Pignolo RJ, Kaplan FS. ECSIT links TLR and BMP signaling in FOP connective tissue progenitor cells. Bone 2018;109: 201–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freund A, Orjalo AV, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Inflammatory networks during cellular senescence: causes and consequences. Trends Mol Med 2010;16(5):238–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munoz-Espin D, Serrano M. Cellular senescence: from physiology to pathology. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014;15(7):482–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hino K, Horigome K, Nishio M, et al. Activin-A enhances mTOR signaling to promote aberrant chondrogenesis in fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Clin Invest 2017;127(9):3339–3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lees-Shepard JB, Yamamoto M, Biswas AA, et al. Activin-dependent signaling in fibro/adipogenic progenitors causes fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. Nat Commun 2018;9(1):471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayashi Y, Hsiao EC, Sami S, et al. BMP-SMAD-ID promotes reprogramming to pluripotency by inhibiting p16/INK4A-dependent senescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016;113(46):13057–13062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brady JJ, Li M, Suthram S, Jiang H, Wong WH, Blau HM. Early role for IL-6 signalling during generation of induced pluripotent stem cells revealed by heterokaryon RNA-Seq. Nat Cell Biol 2013;15(10):1244–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carr MW, Roth SJ, Luther E, Rose SS, Springer TA. Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 acts as a T-lymphocyte chemoattractant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994;91(9):3652–3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu LL, Warren MK, Rose WL, Gong W, Wang JM. Human recombinant monocyte chemotactic protein and other C-C chemokines bind and induce directional migration of dendritic cells in vitro. J Leukoc Biol 1996;60(3):365–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan FS, Pignolo RJ, Al Mukaddam MM, Shore EM. Hard targets for a second skeleton: therapeutic horizons for fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva (FOP). Expert Opin Orphan Drugs 2017;5(4):291–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaplan FS, Zasloff MA, Kitterman JA, Shore EM, Hong CC, Rocke DM. Early mortality and cardiorespiratory failure in patients with fibrodysplasia ossificans progressiva. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92(3): 686–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kirkland JL, Tchkonia T. Cellular senescence: a translational perspective. EBioMedicine 2017;21:21–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.