Abstract

Ehrlichia canis causes a potentially fatal rickettsial disease of dogs that requires rapid and accurate diagnosis in order to initiate appropriate therapy leading to a favorable prognosis. We recently reported the cloning of two immunoreactive E. canis proteins, P28 and P140, that were applicable for serodiagnosis of the disease. In the present study we cloned a new immunoreactive E. canis surface protein gene of 1,170 bp, which encodes a protein with a predicted molecular mass of 42.6 kDa (P43). The P43 gene was not detected in E. chaffeensis DNA by Southern blot, and antisera against recombinant P43 (rP43) did not react with E. chaffeensis as detected by indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) assay. Forty-two dogs exhibiting signs and/or hematologic abnormalities associated with canine ehrlichiosis were tested by IFA assay and by recombinant Western immunoblot. Among the 22 samples that were IFA positive for E. canis, 100% reacted with rP43, 96% reacted with rP28, and 96% reacted with rP140. The specificity of the recombinant proteins compared to the IFAs was 96% for rP28, 88% for P43 and 63% for P140. The results of this study demonstrate that the rP43 and rP28 are sensitive and reliable serodiagnostic antigens for E. canis infections.

Canine ehrlichiosis is a potentially fatal tick-borne rickettsial disease of dogs with worldwide distribution and is primarily associated with the obligately intracellular rickettsial agent, Ehrlichia canis (9). However, canine ehrlichiosis in dogs can be caused by other ehrlichiae with similar and unique hemopoietic cell tropisms, including E. chaffeensis, E. ewingii, E. phagocytophila, and E. platys, and coinfections with multiple ehrlichial agents have been reported in dogs (1, 10). Disease manifestations in dogs caused by infections with E. chaffeensis and E. ewingii are difficult to distinguish from those caused by E. canis (1). E. canis exhibits tropism for monocytes and macrophages (15) and establishes persistent infections in the vertebrate host (8). The disease caused by E. canis is characterized by three stages: the acute stage, which lasts 2 to 4 weeks; the subclinical stage, in which dogs can remain persistently infected for years without exhibiting clinical signs; and ultimately the chronic phase, at which for many dogs the disease becomes progressively worse due to bone marrow hypoplasia and the prognosis is less favorable (21). Treating the disease in the acute phase is important for the best prognosis, but clinical presentation of canine ehrlichiosis is nonspecific, making diagnosis difficult. Hematologic abnormalities such as leukopenia and thrombocytopenia often provide useful evidence of canine ehrlichiosis and are important factors in the initial diagnosis (21).

Diagnosis of canine ehrlichiosis by serologic methods such as the indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) test has become the standard testing method due to its simplicity, reliability, and cost-effectiveness (21). However, shortcomings of the IFA test are the inability to make a species-specific diagnosis due to antigenic cross-reactivity with other closely related Ehrlichia species that infect dogs (E. chaffeensis, E. ewingii, E. phagocytophila, and E. platys) and subjective endpoint interpretations, which may result in false-negative results or false-positive results caused by cross-reactive antigens. Other diagnostic methods such as PCR have been developed for specific detection of E. canis and were reported to be more sensitive than cell culture isolation, but this method requires specialized training and expensive equipment (11). Isolation of the organism is time-consuming, and only a few laboratories have been consistently successful with this method. Furthermore, additional tests to characterize the isolate are required to define a specific etiology using this method.

Serologically cross-reactive antigens shared between E. canis and E. chaffeensis have been reported. Some of the major serologically cross-reactive proteins exhibit molecular masses of 28 to 30 kDa (2, 18), and it is now known that these proteins are encoded by homologous multigene families (16, 17). There are 21 and 5 homologous, but nonidentical, p28 genes that have been identified and sequenced in E. chaffeensis and E. canis, respectively (13, 30). Similar intraspecies and interspecies strain homology is observed between the P28 proteins of E. canis and E. chaffeensis, explaining the serologic cross-reactivity of these proteins (12). A recent report demonstrated that the recombinant P28 (rP28) from E. chaffeensis was an insensitive tool for diagnosing cases of human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (HME) (27). The underlying reason appears to be the variability of the P28 protein among different strains of E. chaffeensis (29). Conversely, the P28 genes identified in E. canis are conserved among geographically dispersed strains in the United States (12, 13), and E. canis rP28 has proven to be useful for the diagnosis of canine ehrlichiosis (16). Other homologous immunoreactive proteins, including the glycoproteins P140 in E. canis and the P120 in E. chaffeensis, have been cloned (26, 28). Reactivity of the rP120 of E. chaffeensis has correlated well with the IFA test for the serodiagnosis of HME, and preliminary studies with the rP140 of E. canis suggest that it may be a sensitive and reliable immunodiagnostic antigen (27, 28).

In this study we have cloned a new highly immunoreactive E. canis protein gene of 1,170 bp, which encodes a protein with a predicted molecular mass of 42.6 kDa (P43). The gene was not detected in E. chaffeensis DNA, and antibodies against the P43 did not react with E. chaffeensis antigen as determined by the IFA test. We compared previously described immunoreactive E. canis rP28 and rP140 proteins with the rP43 protein for the serodiagnosis of canine ehrlichiosis and found the E. canis rP43 and rP28 to be sensitive and reliable for the serologic diagnosis of E. canis infections in dogs and humans. The rP43-based assay or a molecular diagnostic assay using the p43 gene would be especially useful for epidemiologic and clinical studies to examine specific ehrlichial diseases in dogs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ehrlichiae and purification.

E. canis Jake strain was isolated by Edward Breitschwerdt and Michael Levy (College of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, N.C.). The propagation of ehrlichiae was performed in DH82 cells with Dulbecco modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% bovine calf serum and 2 mM l-glutamine at 37°C. The intracellular growth in DH82 cells was monitored by presence of E. canis morulae using general cytologic staining methods. Cells were harvested when 90 to 100% of the cells were infected and then disrupted with a Braun Sonic 2000 sonicator twice at 40 W for 30 s on ice, and ehrlichiae were purified as described previously (22). The lysate was loaded onto discontinuous gradients of 42, 36, and 30% Renografin and then centrifuged at 80,000 × g for 1 h. Heavy and light bands containing ehrlichiae were collected and washed with sucrose-phosphate-potassium buffer (0.2 M sucrose, 0.05 M KH2PO4; pH 7.4) and pelleted by centrifugation.

Construction of the E. canis genomic library.

E. canis genomic DNA was prepared from purified E. canis as previously described (11). The DNA was completely double digested for 1 h with restriction enzymes HinP1I and HpaII (10 U of each enzyme). The digested E. canis DNA fragments were cloned into predigested EcoRI Lambda Zap II vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) by using duplex oligonucleotide conversion adapters (BioSynthesis, Lewisville, Tex.) with HpaII/HinP1I (GC) and EcoRI (AATT) cohesive ends separated by a 12-bp annealing core as described previously (20).

Selection of E. canis recombinants.

Anti-E. canis sera from six naturally infected dogs diagnosed at Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, were pooled and absorbed with XL-1 Blue Escherichia coli to reduce background signal. The immunoreactivity of the pooled sera was determined by Western immunoblot with E. canis antigen. Selection of E. canis recombinants with antibody was performed as described previously (20) with the following modifications. Nitrocellulose membranes overlaid on the recombinant lawn were removed and incubated in blocking buffer (2% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline [TBS, pH 7.4]) for 1 h and incubated with the pooled canine anti-E. canis serum diluted 1:10,000 in blocking buffer for 2 h. Membranes were washed and incubated with an affinity purified goat anti-canine immunoglobulin G (heavy and light chain) [IgG (H+L)] alkaline phosphatase-labeled conjugate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, Gaithersburg, Md.) at 1:5,000 for 1 h and, after another wash, bound antibody was detected with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate-nitroblue tetrazolium (BCIP-NBT). Plaques corresponding to positive reactions with E. canis antisera were purified by a single-plaque isolation and stored in SM buffer (0.1 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 10 mM MgSO4 and 2% gelatin) with chloroform. A second antibody screening on the isolated plaques was performed to confirm antibody reactivity and plaque purity.

Recombinant clone excision and plasmid recovery.

The recombinant phage were excised according to the manufacturer's protocol by incubation with XL-1 Blue MRF′ E. coli and ExAssist helper phage (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) in Luria-Bertani broth at 37°C overnight. Plasmids recovered from resistant colonies were analyzed by digestion with EcoRI corresponding to the conversion adapter-vector restriction site to confirm the presence of an insert. Colonies that contained the plasmids with insert were recovered and frozen in glycerol at −80°C for long-term storage.

DNA sequencing.

Inserts were sequenced with an ABI Prism 377 DNA Sequencer (Perkin-Elmer Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.).

Cloning, expression, and immunoreactivity of recombinant E. canis P43.

A segment representing 95% of the p43 gene was amplified by PCR and cloned directly into a pCR T7/CT TOPO TA expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) designed to produce proteins with a native N terminus and a carboxy-terminal polyhistidine region for purification. A forward primer ECa43BADf (5′-ATG TCA GAT CCA AAA CAA GGT G-3′) and reverse primer ECa43BADr (5′-TCC ATC TAC AAG TCC AAA ATC TAA-3′), designed to produce a 1,107-bp PCR product in the correct frame for expression, were used to amplify the entire gene, excluding the last 63 bp of the open reading frame (ORF) on the carboxy terminal. The cloned p43 gene was transformed into TOP10 E. coli, and positive transformants were screened for the presence of plasmid with the appropriate insert. Transformants containing the plasmid with insert were sequenced to confirm the reading frame and the orientation of the p43 gene. Plasmids containing the proper insert were used to transform BL21(DE3)/pLysS E. coli for protein expression. Expression of P43 was performed by induction with 0.5 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 4 h at 37°C. Recombinant P43 was purified by lysing BL21 E. coli cells under denaturing conditions (8 M urea, 0.1 M NaH2PO4, 0.01 Tris-C1; pH 8.0) for 1 h. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 20 to 30 min, and the supernatant was loaded onto an equilibrated nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid spin column (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.). The bound recombinant protein was washed three times with the denaturing buffer (pH 6.3) and eluted with denaturing buffer (pH 4.5). Purified recombinant protein was dialyzed against ultrapure water for 30 min in microdialyzers (Pierce, Rockford, III.). The expressed recombinant E. canis P43 was subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacyrlamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to a pure nitrocellulose membrane using a semidry electroblotting cell (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). The membrane was blocked for 1 h in 1% nonfat milk dissolved in TBS and incubated with canine anti-E. canis antibody diluted 1:1,000 for 1 h. The membrane was incubated with an affinity-purified alkaline phosphatase-labeled anti-canine IgG(H+L) conjugate (1:5,000) (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories), and bound antibody was detected with BCIP-NBT substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories).

Southern blotting.

A digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled DNA probe was produced by PCR amplification of the p43 gene with primers p43-274f (5′-GAA CCG AAA GTA GAA GAT GAT GAA GA-3′) and p43-1185r (5′-TAA GTT AAC AGG TGG CAA ATG-3′) using DIG-labeled deoxynucleotides. A single 911-bp product was visualized on an ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel. Removal of excess deoxynucleoside triphosphates and primers from the PCR-produced P43 probe was performed using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen). E. canis and E. chaffeensis genomic DNA was quantified spectrophotometrically at A260 and A280, and 0.5 μg of the DNA was digested for 1 h with AseI. The quality of the E. chaffeensis DNA was confirmed by hybridization with a 520-bp DIG-labeled probe amplified with primers 28-1f (5′-AAC TTA TGG CTT TCT CCT CCT TTC-3′) and 28-1r (5′-TTG CCT GAT AAT TCT TTT TCT GAT-3′) specific for one of the E. chaffeensis p28 genes (p28-20). The digested DNA was separated on a 0.8% agarose gel with DIG-labeled molecular mass markers (DNA Molecular Weight Marker II; Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.) and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane by capillary transfer. The membrane-bound DNA was immobilized on the membrane by UV cross-linking, and the membrane was blocked with DIG Easy Hyb buffer (Roche) for 30 min. The denatured p43 or p28 DIG-labeled probe was diluted in 7 ml of DIG Easy Hyb buffer at a concentration of 20 ng/ml and hybridized with the membrane overnight at 39°C. The membrane was washed twice in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% SDS at room temperature for 5 min each time and twice in 0.5× SSC–0.1% SDS at 68°C for 15 min each time. The membrane was incubated in blocking buffer (100 mM maleic acid, 150 mM NaCl [pH 7.5] containing 1% blocking reagent) and then washed and incubated for 30 min with alkaline phosphatase-labeled anti-DIG antibody diluted 1:5,000. The bound DIG-labeled probes were detected with BCIP-NBT substrate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories).

Dog sera.

Forty-two sera from dogs of various breeds suspected of having canine ehrlichiosis based on clinical signs and/or hematologic abnormalities were submitted to the Louisiana Veterinary Medical Diagnostic Laboratory from veterinarians statewide (Table 1). Six E. canis IFA-positive sera from dogs naturally infected in North Carolina, Virginia, and California were obtained from North Carolina State University, College of Veterinary Medicine (Table 1). Negative control sera were obtained from 15 healthy laboratory-reared beagles (Marshall Farms USA, Inc., North Rose, N.Y.), which were 1 to 2 years of age and had been housed in indoor kennels.

TABLE 1.

Summary of historical and hematological abnormalities of 42 dogs with suspected canine ehrlichiosis

| Doga | Age (yr) | Sexb | Breed | Clinical history | Hematological and chemical abnormalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | M | Skye terrier | Lethargy, anorexia, labored breathing | Thrombocytopenia, anemia |

| 2 | 5 | M | Catahoula curr X | NDc | ND |

| 3 | 11 | M/N | Mixed | Chronic uveitis, corneal edema | ND |

| 4 | 11 | F/S | Mixed | ND | ND |

| 5 | 5 | M | Catahoula Curr | Tick bites | Thrombocytopenia, leukopenia |

| 6 | 9 | M/N | Mixed | ND | ND |

| 7 | 3 | M | Mixed | Chronic lameness | ND |

| 8 | 7 | M/N | Boxer X | ND | ND |

| 9 | 7 | F/S | Chow/Rott X | Chronic nephritis, melena, weight loss | ND |

| 10 | 7 | ND | CA red tick hound | ND | Hypergammaglobulimemia |

| 11 | 5.5 | M | Shitzu | Lymphadenopathy, skin hemorage | ND |

| 12 | 1.5 | F/S | Golden retriever | Scleral injection, lethargy | Lymphopenia |

| 13 | ND | F/S | Mixed | Excessive bleeding during spaying | Thrombocytopenia |

| 14 | 11 | F/S | Heeler | Lymphadenitis, lameness | Thrombocytopenia, anemia |

| 15 | 9 | F/S | Labrador | History of ehrlichosis | ND |

| 16 | 4 | M/N | Great Dane | Nonregenerative anemia | ND |

| 17∗ | 2 | F | Mixed | Nonresponder | Anemia, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, hyperglobulinemia |

| 18∗ | 7 | M | Mixed | Profuse epistaxis | Anemia, thrombocytopenia, hyperglobulinemia, polygammopathy |

| 19∗ | 7 | M | Mixed | Anorexic, cough, bleeding ulcer | Anemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, nephropathy |

| 20∗ | 4 | M | Boykin spaniel | Anterior uveitis, acute renal failure | Anemia, thrombocytopenia, neutrophilia |

| 21∗ | 7 | F | Bulldog | Keratoconjunctivitis sicca, fever | Anemia, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminemia, hyperglobulinemia |

| 22∗ | 10 | F | Golden retriever | Nonresponder | ND |

| 23 | 0.42 (5 mo) | M | Schnauzer | Healthy | Thrombocytopenia |

| 24 | ND | M/N | Belgian tervuren | ND | ND |

| 25 | 1.5 | M/N | Brittany | Petechiae on mucous membranes | ND |

| 26 | 8 | F/S | Collie | ND | ND |

| 27 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| 28 | 4 | M | Chow mix | Severe uveitis, increased blood | ND |

| 29 | 3 | F | Catahoula curr X | Lethargic, tick history | ND |

| 30 | 10 | M | Mixed | Bleeding from venipuncture | Thrombocytopenia |

| 31 | 3.5 | M | Labrador | Febrile, lame, limb edema | Thrombocyotopenia |

| 32 | 6 | F | Fox terrier | Lethargy, norm temperature, flexor/extensor pain | ND |

| 33 | 12 | M | Labrador | ND | ND |

| 34 | 4 | M | German shepherd | Weight loss, fever | Neutrophil leukocytosis |

| 35 | 3 | M/N | Poodle | Nonspecific clinical signs | Thrombocyotopenia |

| 36 | 7 | M | Labrador | Lame following exercise-recovers | ND |

| 37 | 0.58 (7 mo) | M | Mixed | Lethargic, anorexia, febrile | Thrombcyotopenia, leukopenia |

| 38 | 9 | M | German shepherd | History of splenomegaly | ND |

| 39 | 2 | M | Pit bull | ND | Thrombocyotopenia |

| 40 | 4 | M | Mixed | No signs | Thrombocyotopenia |

| 41 | 10 | F | Sheltie | Healthy | ND |

| 42 | 1 | M/N | Mixed | Recur fever, gastritis, splenomegaly | Leukocytosis |

∗ , North Carolina sample.

M, male; M/N, male, neutered; F, female; F/S, female, spayed.

ND, no data available.

IFA assay.

Antigen slides were prepared using E. canis Louisiana strain-infected canine bone marrow cells as described previously (7). The infected cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 10 ml of PBS with 0.01% bovine albumin. A portion (10 ml) of antigen was applied to each well of 12-well slides. The slides were air dried and acetone fixed for 10 min. Serial twofold dilutions of dog sera were prepared in PBS from a initial dilution of 1:40. Then, 10 ml of the diluted serum was added to each well. Slides were incubated at 37°C for 30 min, washed twice in PBS, and air dried. An affinity-purified fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-canine IgG(H+L) antibody (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories) diluted 1:50 was added to each well, incubated for 30 min, and then washed. Slides were examined using a UV microscope with filters for fluorescein. An antibody titer of 1:40 or greater was considered positive.

To demonstrate the specificity or cross-reactivity of polyclonal antibodies produced against the rP43, an IFA test using anti-rP43 antiserum was performed with E. canis and E. chaffeensis antigen slides. Antigen slides were incubated with anti-rP43 polyclonal serum diluted 1:100. The slides were washed and incubated with an anti-mouse IgA-IgG-IgM(H+L) FITC-labeled antibody and examined as described above.

Recombinant proteins.

The E. canis rP140 and rP28 have been previously described (12, 25, 28). The E. canis rP140 contained 78% of the ORF, primarily the repeat region, and the E. canis rP28 included the entire ORF. The rP43 expressed protein included 95% of the ORF, excluding the last 21 C-terminal amino acids of the protein described here.

Western blotting of clinical sera.

The recombinant proteins P43, P28, and P140 were separated on a preparative SDS–12% polyacrylamide slab minigel under denaturing conditions. The proteins were transferred to a pure nitrocellulose membrane (0.45 μm pore size; Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.) by using a Trans-Blot SD Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad) at 15 V for 30 min. The protein transfer was monitored by staining membranes with Ponceau S. The position of each recombinant protein was recorded, and the membranes were incubated in blocking buffer (2% nonfat milk in TBS [pH 7.4]). The membranes were placed in a Mini-Protein II Multiscreen Apparatus (Bio-Rad), with a 1:100 dilution of each dog serum, and incubated for 1 h with continuous orbital rocking. The membrane was removed and washed three times with 0.1 M TBS and Tween 20 (0.02%). The membranes were then incubated with a secondary affinity-purified, alkaline phosphatase-labeled anti-canine IgG(H+L) conjugate (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories) diluted 1:5,000 for 1 h with continuous agitation. After the membranes were washed, the bound antibody was visualized with BCIP-NBT substrate.

Nucleotide sequence and accession numbers.

The GenBank accession number for the nucleic acid and amino acid sequences of the E. canis p43 gene described here is AF252298.

RESULTS

p43 gene sequence.

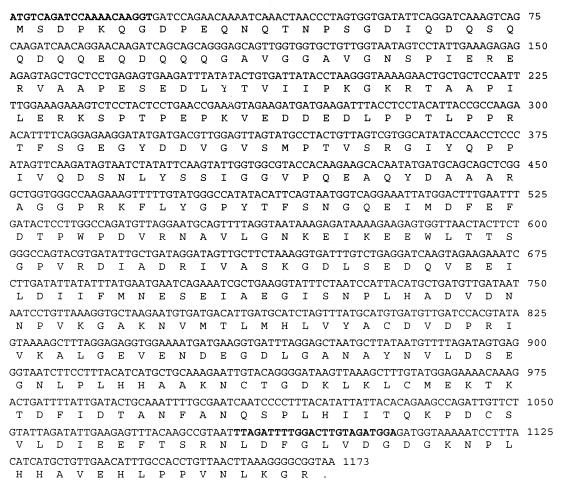

Twelve clones reactive with the pooled anti-E. canis dog sera were digested with EcoRI to determine if the clones contained E. canis DNA inserts. Four clones (41, 52, 72, and 84) had a 2.9-kb insert identified by agarose gel electrophoresis. These four clones were selected for further sequencing and were determined to be identical. One complete and two incomplete ORFs were identified in these clones. The complete ORF was 1,170 bp in length encoding a predicted protein of 390 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of 42.6 kDa (Fig. 1). There were no signal sequences identified, and the protein was predicted to be cytoplasmic (Signal P V1.1 program, http://genome.cbs.dtu.dk/services /Signal P). A BLAST search revealed that the P43 amino acid sequence exhibited significant similarity (45%) with an 88-amino-acid region from the P160 of the HGE agent, Anaplasma phagocytophila. An incomplete ORF 5′ of the p43 gene had significant homology (56%) with the deoxyguanosine triphosphate triphosphohydrolase of Rickettsia prowazekii. The incomplete ORF 3′ of the p43 gene had homology with numerous ankyrin proteins.

FIG. 1.

DNA sequence and predicted protein sequence of the 43-kDa protien gene of E. canis. The primer sequences used to amplify and clone the gene into the prokaryotic expression vector are shown in boldface.

Cloning, expression, and immunoreactivity of the p43 gene.

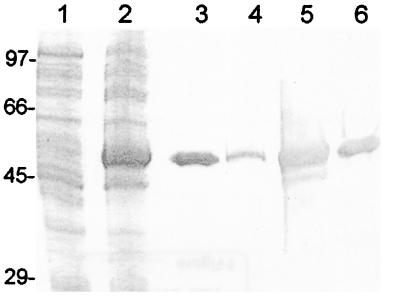

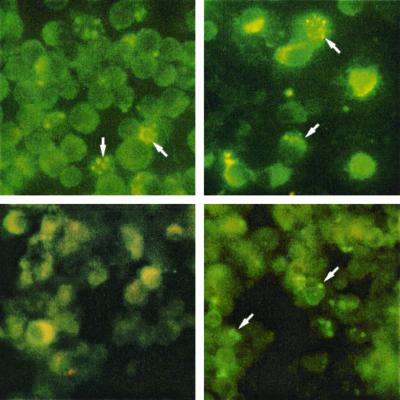

An 1,113-bp product was amplified from genomic E. canis DNA using p43BADf and p43BADr and cloned directly into a prokaryotic expression vector (pCRT7/CT; Invitrogen). The rP43 (95% ORF) was expressed in E. coli, and it exhibited a molecular mass of approximately 50 kDa (Fig. 2). The apparent molecular mass of the expressed fusion protein was slightly larger than the predicted mass including the C-terminal fusion tag (5 kDa). The recombinant expressed protein reacted with anti-E. canis antiserum from an infected dog and the anti-rP43 antibody produced in a mouse (Fig. 2). The anti-rP43 did not react with E. canis antigen separated by SDS-PAGE but did react with E. canis-infected DH82 cells by IFA (Fig. 3). The polyclonal anti-rP43 did not react with E. chaffeensis-infected DH82 cells by IFA.

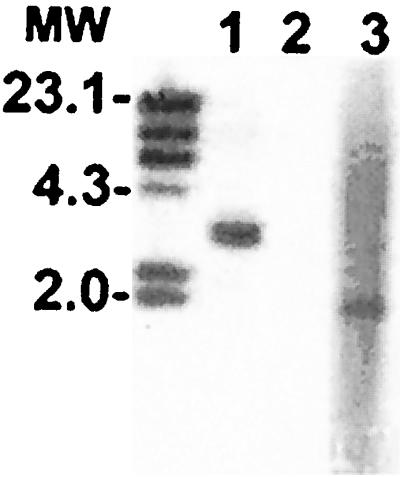

FIG. 2.

E. canis rP43 expressed in E. coli BL21 with a His6 fusion tag. A Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE gel with uninduced rP43-E. coli (lane 1), rP43-E. coli induced with IPTG (lane 2), and purified E. canis rP43 (lane 3) and the corresponding Western immunoblots with canine anti-E. canis antiserum (lanes 4 to 6, respectively) are shown.

FIG. 3.

E. chaffeensis (left)- and E. canis (right)-infected DH82 cells reacted by indirect immunofluorescence with respective convalesent human (E. chaffeensis, left) or canine (E. canis, right) antisera to demonstrate presence of antigen (top) and with anti-rP43 (bottom). Reactivity with anti-rP43 polyclonal antibody was observed only with the E. canis antigen (right). Magnification, ×40.

Southern blotting.

To determine if a homologous gene was present in E. chaffeensis, a Southern blot was performed with a DIG-labeled DNA probe. We identified the p43 gene in an approximately 3-kb fragment of AseI-digested E. canis genomic DNA, but the probe did not hybridize with E. chaffeensis genomic DNA digested similarly (Fig. 4), indicating that a closely related homologous gene was not detected in E. chaffeensis. The quality of E. chaffeensis DNA was confirmed by hybridization of a E. chaffeensis p28 gene probe with a 2.1-kb DNA fragment (Fig. 4). We further attempted to identify a p43 homolog in E. chaffeensis using PCR with four different primer pairs derived from the E. canis p43 gene sequence, but no amplification product was obtained.

FIG. 4.

Southern blot with E. canis and E. chaffeensis DNA (0.5 μg) using a 911-bp DIG-labeled p43 gene probe. The E. canis p43 hybridized with a single band in the genomic DNA of E. canis digested with AseI (lane 1). E. chaffeensis DNA did not hybridize with the p43 gene probe (lane 2). The quality of the E. chaffeensis DNA was confirmed by hybridization of an E. chaffeensis p28 gene probe (p28-20) with a 2.1-kb DNA fragment (lane 3). MW; DIG-labeled DNA markers (in kilobases).

Serodiagnosis by using IFA and recombinant proteins.

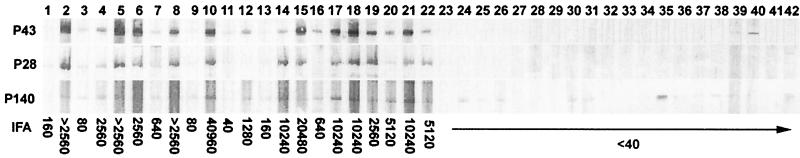

Evaluation of 42 cases clinically suspected to be canine ehrlichiosis by IFA analysis identified 22 seropositive cases with titers ranging from 40 to >40,960 (Table 2 and Fig. 5). Approximately half (21) of the 42 samples had titers 80 or greater, and the other half (21) had titers of 40 or less, which provided the appropriate samples for evaluation of overall sensitivity of the IFA test and recombinant proteins. Of the 42 samples, 20 were found to be negative by the test IFA at 1:40. The recombinant E. canis rP43 had the best correlation with positive IFA samples at a 100% sensitivity, followed by rP28 (96%) and r140 (96%). All samples with IFA titers of ≥80 had 100% positive correlation with the rP43, and all but one had 100% with the rP28. The density of the reaction as demonstrated by Western immunoblot with the recombinant proteins appeared to be proportional to the IFA titer (Fig. 5). rP43 and rP28 exhibited the best combination of sensitivity and specificity, and rP140 reacted nonspecifically with several IFA-negative sera. The observation that three dogs, which were IFA negative for E. canis, were weakly positive to the rP43 antigen suggests that this antigen may be more sensitive than the IFA test rather than less specific. To confirm the specificity, 15 laboratory-reared dogs without a prior history of canine ehrlichiosis were tested, and all were negative for antibodies to E. canis by IFA. Although none of their sera reacted with the rP43 or the rP28, the sera of eight of these dogs reacted with the rP140 (not shown).

TABLE 2.

Reaction of suspect canine ehrlichiosis sera by IFA and with recombinant E. canis proteins as determined by Western immunoblot

| Dog no. | IFA titer | Reactiona with E. canis recombinant protein:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P43 | P140 | P28 | ||

| 1 | 160 | + | + | + |

| 2 | >2,560 | + | + | + |

| 3 | 80 | + | + | + |

| 4 | 2,560 | + | + | + |

| 5 | >2,560 | + | + | + |

| 6 | 2,560 | + | + | + |

| 7 | 640 | + | + | + |

| 8 | >2,560 | + | + | + |

| 9 | 80 | + | + | + |

| 10 | >40,960 | + | + | + |

| 11 | 40 | + | + | + |

| 12 | 1,280 | + | + | + |

| 13 | 160 | + | + | + |

| 14 | 10,240 | + | + | + |

| 15 | 20,480 | + | + | + |

| 16 | 640 | + | + | − |

| 17 | >10,240 | + | + | + |

| 18 | >10,240 | + | + | + |

| 19 | 2,560 | + | + | + |

| 20 | 5,120 | + | + | + |

| 21 | 10,240 | + | + | + |

| 22 | 5,120 | + | + | + |

| 23 | <40 | − | − | − |

| 24 | <40 | − | + | − |

| 25 | <40 | − | + | − |

| 26 | <40 | − | + | − |

| 27 | <40 | − | − | − |

| 28 | <40 | − | − | − |

| 29 | <40 | − | + | − |

| 30 | <40 | − | + | − |

| 31 | <40 | + | + | − |

| 32 | <40 | − | + | − |

| 33 | <40 | − | − | − |

| 34 | <40 | − | − | − |

| 35 | <40 | − | + | − |

| 36 | <40 | − | + | − |

| 37 | <40 | − | + | − |

| 38 | <40 | − | + | − |

| 39 | <40 | + | + | − |

| 40 | <40 | + | − | − |

| 41 | <40 | − | − | − |

| 42 | <40 | − | + | − |

+ , reaction; −, no reaction.

FIG. 5.

Protein immunoblotting of 42 suspect canine ehrlichiosis cases with recombinant E. canis P43, P28, and P140. The corresponding IFA titers to E. canis are shown at the bottom of each lane.

DISCUSSION

We have previously demonstrated the immunoreactivity and potential use of the E. canis rP140 and rP28 proteins as serodiagnostic antigens (12, 28). In this study, we have identified a new immunoreactive protein of E. canis that may be useful for serodiagnosis. rP43 had 100% correlation with samples having an IFA titer of ≥40 and did react with several samples with IFA titers of <40. The increased reactivity of the P43 with numerous IFA-positive sera compared to the P28 suggests that P43 may be more sensitive as a diagnostic antigen. Hence, the weak reactivity of several IFA-negative samples with the rP43 may be hypothesized to reflect the increased sensitivity of the P43; however, paired serum samples were not available to confirm disease in these dogs. The rP43 did not react with sera from laboratory-raised dogs, suggesting that the positive reactions with rP43 from these suspect canine ehrlichiosis cases were specific. rP43 is strongly immunoreactive, and the molecular mass coincides with other ehrlichial proteins observed by Western blot that are immunodominant and cross-reactive between species. This led us to speculate that a homologous p43 gene was present in E. chaffeensis. Hence, we attempted to identify a homologous gene in E. chaffeensis by Southern blot and PCR, but a homologous gene was not detected. In addition anti-rP43 polyclonal antibody reacted strongly with E. canis antigen by as seen IFA testing but not with E. chaffeensis antigen. This evidence suggests that this protein may be antigenically unique to E. canis and may not be the cross-reactive antigen observed by Western immunoblot of E. chaffeensis antigen. The absence of a detectable p43 gene copy in the E. chaffeensis genome and of cross-reactive antibodies against the protein with E. chaffeensis antigens suggests that it could potentially be used for differential diagnosis of E. canis and E. chaffeensis infections in dogs and humans. The fact that all IFA-positive sera with titers of >80 reacted with this apparently species-specific protein suggests that these dogs were infected with E. canis. However, dog 20 was PCR positive on multiple occasions for E. chaffeensis (1). Conversely, P28 would not be useful for such differential diagnosis, since cross-reactivity between the P28 proteins of E. canis and E. chaffeensis is well documented (2, 3). The E. canis P140 is similar to the E. chaffeensis P120 in that they both have tandem repeat units and they are heavily glycosylated (14). The proteins are homologous, but the homology occurs primarily in the N-terminus region upstream of the repeat regions. However, small homologous serine-rich motifs have been identified in the repeat regions (14). Antibodies produced against the two recombinant proteins do not cross-react (14), and probes designed from each gene did not hybridize in Southern blots with heterologous ehrlichial genomic DNA (28). We previously reported that the glycosylated P120 of E. chaffeensis was specific for the diagnosis of HME and that IFA-negative human sera did not react with the rP120 (24). The reactivity of rP140 with the E. canis IFA-negative sera of suspect cases, as well as of the IFA-negative laboratory-reared dogs, suggests that nonspecific cross-reactive antibodies may be involved. One explanation could be the presence of natural antibodies directed at the carbohydrate glycans attached to this protein. Natural antibodies directed at carbohydrates such as those found on red blood cells (blood group antigens) and endothelial cells (hyperacute organ rejection) are believed to be elicited in response to carbohydrate epitopes displayed by microorganisms and parasites (6). Galactose-α1,3-galactose is contains a major epitope of natural antibodies that is well recognized in humans (5). Although little is known about natural antibodies in dogs, there are seven major blood group antigens, suggesting that a wide variety of natural antibodies are present in dogs. The relatively low specificity of E. canis rP140 in dogs is likely due to unique natural antibodies against specific carbohydrate epitopes present on E. canis rP140 and E. chaffeensis rP120 in some dogs. The specificity of natural antibodies varies among animals and humans and thus may explain the reactions of E. canis rP140 observed in dogs in contrast to the specificity we observed using human sera against the similarly glycosylated E. chaffeensis rP120.

We have demonstrated that the E. canis P28 is conserved among geographically separate strains (12, 13). The conservation of this major outer membrane protein among E. canis strains certainly makes it an attractive serodiagnostic candidate antigen. In this study, the E. canis P28 reacted with 96% of the canine sera with an IFA titer of ≥40. The immunoreactivity of this protein with clinical samples from dogs appears to be much better than the reactivity of the E. chaffeensis P28 with human sera. rP28 of E. chaffeensis has proven to be a poor serodiagnostic antigen (27), which is probably related to the diversity of the gene encoding this protein among different strains of E. chaffeensis (29), in addition to the fact that there are 21 homologous but nonidentical p28 genes in the E. chaffeensis genome that may be expressed differentially (30). The conservation of the E. canis p28 gene among American isolates may explain why E. canis rP28 correlates better with the IFA test than does the E. chaffeensis rP28. E. canis rP28 appeared to be less reactive than rP43 when the intensity of the reaction on Western immunoblots was compared. Recent reports have demonstrated that Anaplasma marginale expresses unique msp2 genes in the tick salivary gland, and these antigenically distinct msp2 proteins are the first variants expressed during acute rickettsemia after transmission to the vertebrate host (19). Similar expression of unique variant E. canis p28 genes in the tick salivary gland and expression of these unique variants in the vertebrate host after transmission may occur. Thus, any P28 used for serodiagnosis that is not transmitted by the arthropod host and expressed in the vertebrate host could potentially be less sensitive at detecting acute-phase antibodies.

There is a possibility that some of the dogs used in this study might have been infected with E. ewingii. It has been reported that sera from dogs infected with E. ewingii do not cross-react with the P28 proteins of E. canis or E. chaffeensis (18). Therefore, the single case in this study in which there is reactivity with rP43 and rP140, but not rP28, could possibly be an E. ewingii infection. It is not clear if E. canis rP43 and rP140 cross-react with antibodies in sera from E. ewingii-infected dogs, although proteins with molecular masses of 43 to 47 kDa have demonstrated some cross-reactivity.

We specifically wanted to evaluate a wide range of antibody titers using the recombinant proteins to determine possible differences in diagnostic sensitivity compared to IFA. In these cases submitted for ehrlichiosis testing, three dogs with clinical signs associated with the disease were found to be IFA negative but reacted positively with rP43. The reactivity of these IFA-negative samples with the rP43 suggests that the recombinant proteins could be more sensitive than the IFA test for serodiagnosis. The possibility of cross-reactivity of the rP43 elicited by antigens of an unknown agent may exist, but further testing with acute-phase and convalescent sera from suspect cases would be necessary to provide the information required to confirm the specificity. It is suggested by this study that low antibody titers may be more difficult to detect by the IFA method. Other factors that may also contribute to variations in IFA results include the subjectivity of the endpoint as determined by various readers, differences in antigen production, the use of other reagents, and the assay conditions. The rP140 appears to be especially sensitive at detecting low antibody titers, which would be particularly important for detecting early E. canis infections, considering that the best prognosis correlates with early treatment. The use of recombinant proteins for the diagnosis of E. canis infections would be advantageous to achieve greater consistency of the quality of the antigen and the elimination of test subjectivity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Xue-jie Yu for helpful discussions and advice and Mitch Boudreaux and Barbara Hegarty for assistance obtaining clinical histories and sera.

This study was funded by a grant from the Clayton Foundation for Research and by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI31431).

REFERENCES

- 1.Breitschwerdt E B, Hegarty B C, Hancock S I. Sequential evaluation of dogs naturally infected with Ehrlichia canis, Ehrlichia chaffeensis, Ehrlichia equi, Ehrlichia ewingii, or Bartonella vinsonii. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2645–2651. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2645-2651.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen S M, Cullman L C, Walker D H. Western immunoblotting analysis of the antibody responses of patients with human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis to different strains of Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia canis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:731–735. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.6.731-735.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen S M, Dumler J S, Feng H M, Walker D H. Identification of the antigenic constituents of Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;50:52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen S M, Popov V L, Feng H M, Walker D H. Analysis and ultrastructural localization of Ehrlichia chaffeensis proteins with monoclonal antibodies. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:405–412. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galili U, Macher B A, Buehler J, Shohet S B. Human natural anti-alpha-galactosyl IgG. II. The specific recognition of alpha (1–3)-linked galactose residues. J Exp Med. 1985;162:573–582. doi: 10.1084/jem.162.2.573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galili U, Mandrell R E, Hamadeh R M, Shohet S B, Griffiss J M. Interaction between human natural anti-alpha-galactosyl immunoglobulin G xand bacteria of the human flora. Infect Immun. 1988;56:1730–1737. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.7.1730-1737.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaunt S D, Corstvet R E, Berry C M, Brennan B. Isolation of Ehrlichia canis from dogs following subcutaneous inoculation. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1429–1432. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.6.1429-1432.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrus S, Waner T, Aizenberg I, Foley J E, Poland A M, Bark H. Amplification of ehrlichial DNA from dogs 34 months after infection with Ehrlichia canis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:73–76. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.73-76.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huxsoll D L, Hildebrandt P K, Nims R M. Tropical canine pancytopenia. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1970;157:1627–1632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kordick S K, Breitschwerdt E B, Hegarty B C, Southwick K L, Colitz C M, Hancock S I, Bradley J M, Rumbough R, Mcpherson J T, MacCormack J N. Coinfection with multiple tick-borne pathogens in a Walker Hound kennel in North Carolina. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2631–2638. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2631-2638.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McBride J W, Corstvet R E, Gaunt S D, Chinsangaram J, Akita G Y, Osburn B I. PCR detection of acute Ehrlichia canis infection in dogs. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1996;8:441–447. doi: 10.1177/104063879600800406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McBride J W, Yu X J, Walker D H. Molecular cloning of the gene for a conserved major immunoreactive 28-kilodalton protein of Ehrlichia canis: a potential serodiagnostic antigen. Clin Diag Lab Immunol. 1999;6:392–399. doi: 10.1128/cdli.6.3.392-399.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McBride J W, Yu X J, Walker D H. A conserved, transcriptionally active p28 multigene locus of Ehrlichia canis. Gene. 2000;254:245–252. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00256-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McBride J W, Yu X J, Walker D H. Glycosylation of homologous immunodominant proteins of Ehrlichia chaffeensis and E. canis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:13–18. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.13-18.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nyindo M B, Ristic M, Huxsoll D L, Smith A R. Tropical canine pancytopenia: in vitro cultivation of the causative agent—Ehrlichia canis. Am J Vet Res. 1971;32:1651–1658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohashi N, Unver A, Zhi N, Rikihisa Y. Cloning and characterization of multigenes encoding the immunodominant 30-kilodalton major outer membrane proteins of Ehrlichia canis and application of the recombinant protein for serodiagnosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2671–2680. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2671-2680.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohashi N, Zhi N, Zhang Y, Rikihisa Y. Immunodominant major outer membrane proteins of Ehrlichia chaffeensis are encoded by a polymorphic multigene family. Infect Immun. 1998;66:132–139. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.132-139.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rikihisa Y, Ewing S A, Fox J C. Western immunoblot analysis of Ehrlichia chaffeensis, E. canis, or E. ewingii infections in dogs and humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2107–2112. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.9.2107-2112.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rurangirwa F R, Stiller D, French D M, Palmer G H. Restriction of major surface protein 2 (MSP2) variants during tick transmission of the ehrlichia Anaplasma marginale. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3171–3176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.6.3171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stover C K, Vodkin M H, Oaks E V. Use of conversion adaptors to clone antigen genes in λgt11. Anal Biochem. 1987;163:398–407. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90241-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Troy G C, Forrester S D. Canine ehrlichiosis. In: Green C E, editor. Infectious diseases of the dog and cat. Philadelphia, Pa: The W. B. Saunders Co.; 1990. pp. 404–418. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss E, Coolbaugh J C, Williams J C. Separation of viable Rickettsia typhi from yolk sac and L cell host components by renografin density gradient centrifugation. Appl Microbiol. 1975;30:456–463. doi: 10.1128/am.30.3.456-463.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu X, Brouqui P, Dumler J S, Raoult D. Detection of Ehrlichia chaffeensis in human tissue by using a species-specific monoclonal antibody. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3284–3288. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.12.3284-3288.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu X J, Crocquet-Valdes P, Cullman L C, Popov V L, Walker D H. Comparison of Ehrlichia chaffeensis recombinant proteins for diagnosis of human monocytotropic erhlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2568–2575. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2568-2575.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu X J, Crocquet-Valdes P, Cullman L C, Walker D H. The recombinant 120-kilodalton protein of Ehrlichia chaffeensis, a potential diagnostic tool. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2853–2855. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.11.2853-2855.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu X J, Crocquet-Valdes P, Walker D H. Cloning and sequencing of the gene for a 120-kDa immunodominant protein of Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Gene. 1997;184:149–154. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00586-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu X J, Crocquet-Valdes P A, Cullman L C, Popov V L, Walker D H. Comparison of Ehrlichia chaffeensis recombinant proteins for serologic diagnosis of human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2568–2575. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2568-2575.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu X J, McBride J W, Diaz C M, Walker D H. Molecular cloning and characterization of the 120-kilodalton protein gene of Ehrlichia canis and application of the recombinant 120-kilodalton protein for serodiagnosis of canine ehrlichiosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:369–374. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.369-374.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu X J, McBride J W, Walker D H. Genetic diversity of the 28-kilodalton outer membrane protein gene in human isolates of Ehrlichia chaffeensis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:1137–1143. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.4.1137-1143.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu X J, McBride J W, Zhang X F, Walker D H. Characterization of the complete transcriptionally active p28 multigene family of Ehrlichia chaffeensis. Gene. 2000;248:59–68. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(00)00147-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]