Abstract

Objectives

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is a highly effective, recommended intervention for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Using behavioural theory within mixed-methods research to understand why referral remains low enables the development of targeted interventions in order to improve future PR referral.

Design

A multiphase sequential mixed-methods study.

Setting

United Kingdom (UK).

Participants

252 multiprofessional primary healthcare practitioners (PHCPs).

Measures

Phase 1: semistructured interviews. Phase 2: a 54-item paper and online questionnaire, based on the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF). Content and descriptive analysis utilised. Data mixed at two points: instrument design and interpretation.

Results

19 PHCPs took part in interviews and 233 responded to the survey. Integrated results revealed that PHCPs with a post qualifying respiratory qualification (154/241; 63.9%) referred more frequently (91/154; 59.1%) than those without (28/87; 32.2%). There were more barriers than enablers for referral in all 13 TDF domains. Key barriers included: infrequent engagement from PR provider to referrer, concern around patient’s physical ability and access to PR (particularly for those in work), assumed poor patient motivation, no clear practice referrer and few referral opportunities. These mapped to domains: belief about capabilities, social influences, environment, optimism, skills and social and professional role. Enablers to referral were observed in knowledge, social influences memory and environment domains. Many PHCPs believed in the physical and psychological value of PR. Helpful enablers were out-of-practice support from respiratory interested colleagues, dedicated referral time (annual review) and on-screen referral prompts.

Conclusions

Referral to PR is complex. Barriers outweighed enablers. Aligning these findings to behaviour change techniques will identify interventions to overcome barriers and strengthen enablers, thereby increasing referral of patients with COPD to PR.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pulmonary rehabilitation (PR), primary care, theoretical domains framework (TDF). mixed methods research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first mixed-methods study to use the Theoretical Domains Framework to identify barriers and enablers to pulmonary rehabilitation referral from a primary healthcare practitioner perspective.

The utilisation and combination of two differing research paradigms in this exploratory sequential approach offers novel and detailed insights through combined research lenses which encompass multiple perspectives.

Many geographical regions across the UK are represented and include a diverse range of primary healthcare practitioners.

A combination of participant recruitment approaches have been used to reduce potential sample and selection biases.

Generalisability of the overall findings are limited by the inability to calculate distribution and therefore response rates.

Background

Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) is a low cost, high value, internationally recommended intervention for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) which is effective in improving exercise capacity, reducing the impact of symptoms and improving prognosis.1 2 It is a structured multidisciplinary intervention combining individualised exercise with disease-related education.3 Despite the clear evidence of its effectiveness, the proportion of patients with COPD receiving PR is persistently low worldwide.4 5 Our previously published inductive qualitative paper presented the experiences of primary healthcare practitioners (PHCPs) as key potential referrers to PR.6 We found that there was a generalised awareness of PR, but little detailed knowledge of either the programme or the clinical benefits. Relationships with PR providers were limited, but considered important. Patient characteristics, rather than clinical need, influenced referral offers and referrers frequently believed patients to be poorly motivated. PR was most commonly offered during times of disease stability (usually at COPD annual review) and ease of the referral process and financial incentives positively influenced referral. In summary, referrers reported many barriers but few enablers, which collectively resulted in infrequent discussions about PR and associated referrals.

However, in order to aid the development of appropriate interventions to improve referral rates it is important to establish the generalisability and relative importance of these findings within a broader population of PHCPs. Furthermore, applying theory to identify the psychological and structural drivers that influence behaviour7 8 may offer new insights to shape interventions.9

The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) is a well-recognised approach which was derived from a synthesis of behaviour change theories,10 and examines the processes that influence behaviour.11 When applied, it offers explanations for behaviours, highlighting reasons that may inhibit or promote12 13 implementation of practice-based change.12

Using mixed methods and applying the TDF, we sought to assess and explain the reasons for low PR referral by PHCPs for patients with COPD. The aim of our multiphase design was to inform the development of theory informed interventions to improve PR referral rates from primary care in future.

Methods

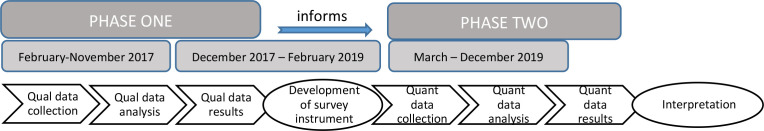

We used a multiphase sequential design defined by two separate phases (figure 1). The cognitive and practical experiences of PHCP when considering and undertaking referral for patients with COPD were initially explored using a deductive approach by applying the TDF to data from our previously collected qualitative interviews. These findings informed a second quantitative phase, where we tested themes for generalisability using a nationwide survey of PHCP, to highlight the most relevant factors influencing referral.14–16

Figure 1.

Multiphase sequential research design.

Both datasets retained independent value and meaning, but were connected at two time points: (1) where the qualitative data were used to construct the questionnaire and (2) where phase 1 and 2 results were integrated to inform interpretation. The multiphase sequential mixed-methods design therefore achieves both methodological and content integration.15 16

Patient and public involvement

There has been no public and/or patient involvement in this study.

Phase 1: application of TDF to qualitative interview data

We reanalysed data from our previously published inductive qualitative study6 in which 19 PHCPs from two differing geographical regions across Central and East of England were recruited and interviewed to thematic saturation using a predesigned topic guide. A deductive approach using content analysis17 was used for re-analysis of the data in order to align the results to the TDF and to offer new insights.

The interview topic guide (online supplemental additional file 1) was mapped to the Capability Opportunity Motivation-Behaviour model (COM-B), a model that highlights three critical prerequisites for behaviour change.18 This model was adopted rather than the TDF to guide interviews primarily because of the practical need to reduce interview length without compromising its aim. COM-B is very closely aligned to the TDF and has been utilised as a topic guide and mapped to the TDF in a similar healthcare professional study.19

bmjopen-2020-046875supp001.pdf (121.7KB, pdf)

Analysis

All interview transcripts were managed using NVivo V.12. Barriers and enablers emerging from the interviews via content analysis were mapped to the relevant TDF domain, initially using construct labelling10 20 (online supplemental additional file 2). Utterances were coded once to the key TDF construct which then determined TDF domain alignment. JSW undertook the initial coding, then five transcripts were randomly allocated and distributed throughout the team (REJ, PA and SG) and independent TDF coding occurred, followed by frequent collaborative team discussion to ensure agreement with the coding. Queries were discussed with a behavioural expert (IV).

bmjopen-2020-046875supp002.pdf (51.8KB, pdf)

Phase 2: quantitative methodology

Study design: cross-sectional survey

PHCPs were recruited via two main methods. Initially an invitation was included in a fortnightly newsletter emailed to members of the Primary Care Respiratory Society (PCRS). The survey was additionally distributed and shared by PCRS via their organisational Twitter and Facebook accounts. Social media distribution of the survey was further increased by individual and other organisational sharing, including the Facebook accounts of Advanced Practice UK and General Practice Nurse UK. A link for questionnaire completion was provided to the platform ‘Online Survey’.21 This was open between April and December 2019. To increase participation, responders were invited to opt in to a prize draw to win an I-pad.

Simultaneously, paper versions of the questionnaire were distributed at six UK conferences between March and November 2019 to attending PHCPs (predominately by hand by JSW, and using ‘in-conference bag’ distribution at one event). On self-completion, questionnaires were placed by participants in a locked ballot box and an optional token of appreciation was offered. Paper questionnaires were manually entered onto ‘Online survey’ by JSW.

As this was exploratory research, no a priori sample size calculations were performed. A pragmatic approach to study closure was adopted, this being online availability for a period of 8 months, distribution of the questionnaire at several appropriate PHCP targeted events, and that a reasonable range of PHCP had responded.

Methodology: instrument design

The cross-sectional survey (online supplemental additional file 3), collected (1) individual sociodemographic data, (2) current referral experiences, using TDF-based Likert scale questions (n=54) and (3) any new or complementary issues which may not have been previously mentioned, using an optional open question.22

bmjopen-2020-046875supp003.pdf (171.2KB, pdf)

Socio-demographic data

These included questions on geographical location of practice, job title, postqualifying respiratory education and estimated frequency of PR referrals, using questions with pre-specified options.

Psychometric data

Barriers and enablers for PR referral identified from the phase 1 qualitative findings were converted into belief statements,20 including some that sought to test direct understanding. All questions were generated and aligned to the TDF by the coder (JSW) and validated by other team coders (REJ), including a TDF expert (IV). Fifty-four closed, fully labelled 5-point Likert scale questions/belief statements were included with responses ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ and a midpoint rating. Some statements were reversed as an opposite belief to that frequently reported in the phase 1 data. These design elements were purposely selected to improve reliability and validity.23

The final survey mapped the 54 belief statements and open question section to 12 out of 14 theoretical domains (‘emotion’ and ‘behavioural regulation’ was excluded, given its low mapping in phase 1 results). Two rounds of survey piloting were undertaken with five practice nurses and the questionnaire refined to ensure question clarity and clearer completion instructions.

Analysis

All data were exported into an Excel V.16spreadsheet and STATA V.16 used to conduct simple descriptive statistics (frequencies and percentages), dichotomising into Agree/Strongly Agree versus the remaining options. Free text that directly related to barriers and enablers of referral practice was content-mapped to the TDF and thematic analysis applied.24

Results: phase 2

Response rates

Paper surveys (>1100) were distributed across six UK primary care focused events which were attended by a variety of PHCPs. A total of 154 (~14%) were returned and 134 (83%)/154 completed the survey sufficiently and were included. Online, it is unknown how many potential practitioners read the survey invitation, therefore participation rates could not be calculated. One hundred and twenty three participants started the online survey, but only 99 (80.5%) completed it and were included in the analysis.

Full details of the paper survey distribution and return rates can be found in online supplemental additional file 1.

Description of participants

Table 1 presents the sociodemographic characteristics for participants in the phase 2 quantitative (n=233) studies. Participants characteristics for phase 1 (qualitative) are available in the previously published paper.6

Table 1.

Baseline demographics of phase 2 participants

|

|

Phase 2 survey (n=233) | |||

| Conference (n=134) (%) |

Online (n=99) (%) |

Total (n=233) (%) |

||

| Primary healthcare practitioner role | General practitioner (GP) | 18 (13.4) | 11 (11.1) | 29 (12.5) |

| Advanced nurse practitioner (ANP) | 25 (18.7) | 32 (32.3) | 57 (24.5) | |

| Practice nurse (PN) | 85 (63.4) | 44 (44.5) | 129 (55.4) | |

| Emergency care practitioner (ECP) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (1) | 2 (0.9) | |

| Pharmacist | – | 4 (4) | 4 (1.7) | |

| Healthcare assistant (HCA) | – | 1 (1) | 1 (0.4) | |

| Other | 5 (3.7) | 6 (6.1) | 11 (4.7)) | |

| Total responses | 134/134 (100) | 99/99 (100) | 233/233 (100) | |

| Sex | Female | 115 (91.3) | 92 (92.9) | 207 (92) |

| Male | 11 (8.7) | 7 (7.1) | 18 (8) | |

| Total responses | 126/134 (94) | 99/99 (100) | 225/233 (96.6) | |

| Age (years) | 18–29 | 5 (3.8) | 2 (2) | 7 (3.0) |

| 30–39 | 32 (24) | 11 (11.1) | 43 (18.5) | |

| 40–49 | 36 (27.1) | 40 (40.4) | 76 (32.8) | |

| 50–59 | 49 (36.8) | 40 (40.4) | 89 (38.4) | |

| 60+ | 11 (8.3) | 6 (6.1) | 17 (7.3) | |

| Total responses | 133/134 (99.3) | 99/99 (100) | 232/233 (99.6) | |

| Ethnicity | White British | 112 (84.2) | 87 (87.9) | 199 (85.7) |

| White other | 8 (6) | 4 (4.1) | 12 (5.2) | |

| Asian/Asian British | 7 (5.3) | 3 (3) | 10 (4.3) | |

| Mixed multiple ethnic groups | 1 (0.7) | 2 (2) | 3 (1.3) | |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 2 (1.4) | – | 2 (0.9) | |

| Other ethnic group | 3 (2.4) | 3 (3) | 6 (2.6) | |

| Total responses | 133/134 (99.3) | 99/99 (100) | 232/233 (99.6) | |

| Practice geographical location | Scotland | 1 (0.8) | 3 (3) | 4 (1.7) |

| England North East and West | 31 (23.6) | 15 (15.1) | 46 (20) | |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 8 (6.1) | 6 (6.1) | 14 (6) | |

| Midlands (East and West) | 20 (15.3) | 16 (16.1) | 36 (15.8) | |

| East of England | 23 (17.5) | 18 (18.2) | 41 (17.8) | |

| Wales | 31 (23.6) | – | 31 (13.5) | |

| London | 3 (2.4) | 6 (6.1) | 9 (3.9) | |

| South (East and West) | 14 (10.7) | 35 (35.4) | 49 (21.3) | |

| Total responses | 131/134 (97.8) | 99/99 (100) | 230/233 (98.7) | |

| Years in general practice | <5 | 39 (29.9) | 23 (23.2) | 62 (27) |

| 6–10 | 26 (19.8) | 25 (25.3) | 51 (22.2) | |

| 11–15 | 18 (13.7) | 18 (18.2) | 36 (15.7) | |

| 16–20 | 22 (16.8) | 14 (14.1) | 36 (15.7) | |

| 21+ | 26 (19.8) | 19 (19.2) | 45 (19.4) | |

| Total responses | 131/134 (97.8) | 99/99 (100) | 230/233 (98.7) | |

| Currently see patients with COPD | Acute management | 9 (6.7) | 5 (5) | 14 (6) |

| Chronic management | 30 (22.6) | 26 (26.3) | 56 (24) | |

| Acute and chronic management | 81 (60.9) | 67 (67.6) | 148 (64) | |

| Don’t see patients with COPD | 13 (9.8) | 1 (1) | 14 (6) | |

| Total responses | 133/134 (99.3) | 99/99 (100) | 232/233 (99.6) | |

| CPD respiratory qualifications* | None | 62 (46.3) | 19 (19.2) | 81 (34.8) |

| COPD diploma | 28 (20.9) | 50 (50.5) | 78 (33.5) | |

| Asthma diploma | 38 (28.4) | 52 (50.5) | 90 (38.6) | |

| ARTP Spiro | 34 (25.4) | 40 (40.4) | 74 (31.8) | |

| Other | 16 (11.9) | 26 (26.3) | 42 (18) | |

| >1 qualification | 32 (23.9) | 51 (51.5) | 83 (35.6) | |

| Total responses | 210 | 238 | 448 | |

| Reported PR referral practice | Yes (frequency not specified) | – | 11 (11.1) | 11 (4.7) |

| Weekly | 16 (12) | 32 (32.3) | 48 (20.7) | |

| Monthly | 40 (30.1) | 21 (21.2) | 61 (26.3) | |

| <Monthly | 43 (32.3) | 29 (29.3) | 72 (31) | |

| None | 34 (25.6) | 6 (6.1) | 40 (17.3) | |

| Total | 133/134 (99.3) | 99/99 (100) | 232/233 (99.6) | |

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPD, continuous practice development; PR, pulmonary rehabilitation.

In contrast to the qualitative study where 6 (32%)/19 were GPs, the survey respondents were predominantly female nurses. Nurse respondents were similarly distributed across both conference and online groups (110/134, 82.1%; and 76/99, 76.9%, respectively) and responders from both sources had similar time working in practice. However, respondents recruited through conferences, compared with those who responded online, tended to be younger (28% <40 years of age), more likely to be practice nurses rather than other types of professionals, but were less likely to have respiratory qualifications, to see patients with COPD or to refer them to PR.

Referral to PR by type of healthcare professional

Overall, 109 (49.1%) reported being frequent referrers to PR, with GPs being less likely to refer and other professions including emergency care practitioners, nurse practitioners and advanced nurse practitioner (ANPs) more likely to refer. Referral was also higher among those with one or more continuous practice development (CPD) respiratory qualifications. However, this may be partly related to such qualification being higher among ANPs (82.5% (47/57)) and other grouped professions (58.8% (10/17)) than among GPs (17.9% (5/28)). More than 10 years spent in general practice appeared to marginally increase referral frequency (60.7%; 51.8%). Table 2 presents PHCP reported referral practice.

Table 2.

PHCP referral practice*

| Frequent referral n (%) (weekly or monthly) Total N=109 |

Infrequent referral n (%) (>monthly or no referral) Total N=113 |

|

| Staff type | ||

| GP (n=28) | 10 (35.7) | 18 (64.3) |

| PN (n=120) | 57 (47.5) | 63 (52.5) |

| ANP (n=57) | 32 (56.1) | 25 (43.9) |

| Other (ECP/NP/Pharm/HCA) (n=17) | 10 (58.8) | 7 (41.2) |

| CPD respiratory qualification | 84 (77.1) | 59 (52.2) |

| Years in practice >10 years† | 65/107 (60.7) | 58/112 (51.8) |

*11/99 online PHCPs specified that they referred to PR but did not specify referral frequency and were removed from this analysis.

†107/109 and 112/113 reported time spent in general practice.

CPD, continuous practice development; ECP, emergency care practitioner; GP, general practitioner; HCA, healthcare assistant; NP, nurse practitioner; PHCP, primary healthcare practitioner; PN, practice nurse; PR, pulmonary rehabilitation.

Forty (17.2%) of 233 responding PHCPs reported never referring to PR, with the largest group being practice nurses (29/40; 72.5%). Thirty-three of 40 PHCPs offered a variety of reasons for non-referral including; not considering it to be part of their role, not seeing patients with COPD or not knowing they could refer (12/33; 36.4%). Others reported it was undertaken by other respiratory specialist/interested healthcare professionals across primary and secondary care settings (12/33; 36.4%). Further reported reasons were unsure how to and/or a lack of training (5/33; 15.1%), uncertainty about local service provision (3/33; 9.1%) and 1/33 (3.0%) reported belief that patients were not interested.

Phase 1 results: TDF analysis of the qualitative interviews

Table 3 shows the referral behaviour of PHCPs mapped to all 14 TDF domains. The most frequently mapped domain was social and professional role (n=287 times) while the least mapped was behavioural regulation (n=4).

Table 3.

Phase 1: mapping of barriers and enablers for referral to TDF domains

| TDF domain (construct mapping frequency) | Content mapping (n) | Key | Evidence supporting |

|

1. Social and Professional role (A coherent set of behaviours and displayed personal qualities of an individual in a social or work setting) |

289 | Referral was considered everyone’s role, however it was considered best undertaken by the PHCP during disease stability and at annual review. It was often considered to be the practice nurses’ role, but also respiratory-interested others. Most PHCPs considered it their duty of care to motivate patients. Only 1 of 19 PHCPs described implementing practice leadership to improve PR awareness and/or referral. |

It is largely the nurses’ job to see stable COPD patients at an annual review and that is the most appropriate time to refer to pulmonary rehabilitation, not during an acute exacerbation. GP5 No, I think it’s everybody’s role, I mean I’m not sure about my non-respiratory colleagues. PN2 So we've put forward a proper business case for it (Local PR service). GP4 |

|

2. Knowledge (An awareness of the existence of something) |

256 | 17 of 19 PHCPs knew of the existence of PR and a generalised understanding of its purpose. PR Knowledge was reported to be gained through post qualification education and networking events. Local PR knowledge such as programme timing, waiting list (if any), and availability of patient transport, was often unknown and were described as inhibitors to referral discussions. The referral criteria Medical Research Council (MRC) dyspnoea score ≥3 was frequently cited as a referral prompt, although some PHCPs wanted to refer patients with MRC scores of 2 and felt unable to. |

I think it’s a fundamental treatment and I think it’s better than drugs. PN7 Do you currently refer to PR? P -I wouldn’t know where. GP2 I don’t know how to describe pulmonary rehab to a patient. GP3 I just feel that we don’t know enough about the program to confidently hand on your heart sell it. PN1 We’ve also got the barrier of we can only refer if their MRC is 3 or 4 or 5. PN5 |

|

3. Environment (Any circumstance of a person’s situation or environment that discourages or encourages the development of skills and abilities, independence, social competence and adaptive behaviour) |

195 | PR referral was often considered inappropriate in non-COPD focused consultations or when a patient was consulting for an acute exacerbation. Clinical time constraints were often described as inhibiting referral, although annual review considered appropriate time because of its clinical focus, template design and longer consultation time. PHCPs often stated little PR promotional material was available in practice for patients or staff; there were however mixed views on the potential value of this. Three practices had initiated an in-practice 12 weekly, 1 hour generic exercise group, this appeared to be seen as equivalent to PR by 1 PN. |

I think in our role when you’re treating potentially acutely unwell people in a really limited time span then it’s, it is realistically going to be hard to cover everything, really hard. ANP2 On the annual review well I follow the template and when I get to the pulmonary rehab I mention it then and I say, ‘Would you like to go?’ PN3 It would be useful for our local organisation I think to give us some little leaflets about what they do so we can give that to patients about the local service. ANP4 I’m not against a leaflet but have you seen how many posters and leaflets we have on our walls? GP2 |

|

4. Belief about capabilities (Acceptance of the truth, reality, or validity about an ability, talent, or facility that a person can put to constructive use) |

141 | Individual PHCP PR referral confidence varied, with particular uncertainty expressed in how to best ‘sell PR’ and how to motivate unmotivated patients. Although most were confident in reassuring patients that PR would improve breathlessness. PHCPs with positive non-pharmacological and exercise beliefs appeared to have greater confidence in PR benefit and patients’ abilities. A number of PHCPs described patients with COPD as uninterested in improving their health and some PHCPs emphasised patients needed to be committed to PR. While some PHCPs described ‘knowing’ which patients would accept referral, others described undertaking subjective patient assessment and expressed concerns about patients’ exercise capability in the presence of breathlessness. For patients receiving oxygen therapy there was much uncertainty of the benefit of PR and an assumption that oxygen/secondary care teams would have previously offered this. Most PHCPs considered key environmental factors such as session timing, venue accessibility, patient financial hardship, as barriers for most patients. Patients in work, or those able to take the dog for a walk/wearing walking boots were considered ‘too well’ for PR. |

I would need to feel confident, before I speak to this patient about it. ANP4 I quite like…Non-medicinal treatment…think if you're excited by it then it’s easier for patients to get excited by it as well. GP4 They are also very very clear that there not going to take anyone on their course unless there is 100% commitment at the beginning that they are going to complete the course. ANP1 You look at the ones that you think would more likely go. ANP4 It’s really basically where I see a need, where I see they can benefit. ANP1 If the patients already on oxygen therapy, then it’s likely that they’ve already been seen by them. HCA The main stumbling block is that you come across is I’m not going every week for x number of weeks, I can't afford it, I haven't got that much time, how do you expect me to get there….not a huge number of our patients drive. GP4 There’s some patients that I would like to refer but they can’t go because of work commitments. PN3 It’s quite surprising that some patients are still working at odd jobs and things like that and keep them very active. So, for those patients it’s not so important. PN3 |

|

5. Memory (Inc: decision-making) (The ability to retain information, focus selectively on aspects of the environment and choose between two or more alternatives) |

118 | Some PHCPs reported forgetting to refer patients to PR, however, embedded system reminders often found in COPD review templates or on-screen prompts were cited as important for most PHCPs. Patient behaviour and clinical presentation altered decision-making processes for some PHCPs for example not referring current smokers, or remembering PR in light of increasing COPD symptom burden and disease deterioration, while earlier concerns for patient capability and commitment became less apparent. |

I do need a reminders because my head’s full, so as I say, I don’t want to tick boxes but I do need a prompt. PN7 That’s something that we do, so we have a prompt that pops up saying has this patient been referred to pulmonary rehab. GP5 I think I go through phases, I’ll do it really well for a while and somebody has motivated me and then I’ll forget that and do something else. PN7 Breathlessness and exacerbations, I think, would be the key factors. GP3 |

|

6. Optimism (The confidence that things will happen for the best or that desired goals will be attained) |

110 | PHCPs frequently reported that patients did not want to attend PR, citing disease stigma and lack of activation as underlying reasons. Negative patient responses appeared to dampen PHCPs optimism and reduce subsequent referral offers. Positive patient experience however had the opposite effect. Positive and negative perceptions of PR providers were also reported on the basis of service quality and frequency of referral acceptance, this appeared to influence referral behaviour. |

The first thing you think, Are they going to do it? ANP4 Patients don’t want it. PN5 Even if you then said what the evidence was and how you could improve, it’s – I think that group of people are really difficult to engage.GP3 If they’re negative anyway everything you suggest they sort of have an answer, Oh no that won’t work. PN4 The longer the wait time, the less likely they are to turn up. HCA I don’t think it’s the greatest service, it does have an impact because I’m not going to tell my patients to go. PN7 |

|

7. Belief about consequences (Acceptance of the truth, reality, or validity about outcomes of a behaviour in a given situation) |

107 | There was a general sense that PR is positive with many health and psychological benefits, but beliefs captured in other domains impacted on PHCP belief about consequences of referral offer. A small number of PHCPs expressed concern that PR might worsen patient’s depression and/or anxiety, particularly for those socially isolated. |

I’ve seen patients that have been… their lives have been transformed in the first year. PN7 Might have prevented the exacerbation if they’d gone PN5 I will say that when I’m talking to patients, say it’s better than drugs, but I still get a closed reaction. PN7 If we can improve patient’s breathing they’re less likely to get anxious, that makes them less likely to dial 999 or likely to do something about it. And perhaps use their rescue packs more appropriately. ANP4 I wouldn’t want to mention it if it ended up being that I’m saying there’s this really good helpful programme but actually if she’s so effected by her disease that she doesn’t leave the house then I wouldn’t want to have mentioned it and then not for her not to be able to go. ANP2 |

|

8. Social influences (Those interpersonal processes that can cause individuals to change their thoughts, feelings, or behaviours) |

84 | Out of practice engagement from PR providers and PR advocates were important in increasing overall awareness and positively influencing referral behaviour. Almost all PHCPs described little to no engagement from providers themselves, and described not knowing what had happened to completed referrals. PHCPs also reported that positive patient PR experiences positively influenced PHCPs referral behaviour and that family can be influential, yet patients rarely ask for PR. PHCPs described a need to increase PR’s profile publicly and for it to be marketed similarly to pharmacological treatments. The name PR itself was considered by some PHCPs to be a negative influence as ‘rehab’ was deemed to have undesirable connotations. |

Our referral rate has gone up a lot since the respiratory MDT’s because every single one of those patients has subsequently had a referral. GP4 At the moment I wouldn’t know how many people we refer, is that referral going up, Nobodies giving us feedback from the rehab team about how we are doing as a surgery. PN1 If patients that have been to it you know express a positive experience that is something you can share with other people that you are trying to refer. GP1 I asked him to talk to his wife, because I knew she’d want him to go, because I know her through a different channel, and erm… he’s come back and said ‘Ooo I’ll give it a shot. PN5 Nobody has picked up a leaflet and walked in with it and said can you refer me, nobody has. ANP1 |

|

9. Skills (An ability or proficiency acquired through practice) |

79 | The physical act of referring patients to PR were described as largely straightforward by most PHCPs, although there was no standardised process across the two regions. Most undertook this action independently, although there were descriptions of practice administrators helping. However, frequency of referral to PR when described in interviews, was far lower than that which was documented on the returned research interest form. |

Do you currently refer people to pulmonary rehab? Some, some. PN7 I’ve been at this practice for nearly three years now and it’s sort of something that falls really far down on your list of things that you do on your COPD review, so it’s always the last thing that you come to. GP4 It’s very easy. It’s a form erm it’s a just a single sheet. PN2 Quicker, easier referral, much easier referral method. PN7 |

|

10. Reinforcement (Increasing the probability of a response by arranging a dependent relationship, or contingency, between the response and a given stimulus) |

59 | There appeared to be no direct sanctions for non-referral of patients, although practice financial rewards in one region appeared to enhance awareness and referral. Outside of these practices there was a suggestion that financial incentives would be advantageous, additionally calculating health cost benefit for PR attendance was suggested as potential enabler. Additionally reinforcements such as those offered by social influences and patients were also described to be valuable. |

We’ve got this thing called A** that we’re doing for, you know it was the QOF before, so like A** has taken over that so I think because of the A** the doctor who is the lead A** leader he discusses that a lot because of course you get points, you still get the points for it like QoF. So the more we refer is the more points we get so there’s an incentive there for the practice. PN6 Yeah if they did something on the BBC or something they might all be in the next day saying, ‘Oh I wanna do that’. PN4 If you spent 5 minutes with somebody then at the end of that they agreed to go and then they attended, then you would be motivated to do it again. GP5 |

|

11. Goals (Mental representations of outcomes or ‘end states’ that an individual wants to achieve) |

47 | Referral to PR was a low-level goal for most PHCPs, but one that varied by consultation type and was not considered during an acute exacerbation review. However, referral appeared to become a goal in the presence of worsening patient symptoms. Some PHCPs described wanting to refer more patients and learning strategies to improve patient acceptance, but described frequent discord between PHCP and patient goals which PHCPs found challenging. No PHCPs discussed set practice PR referral targets although one GP reported plans to set up a programme geographically closer to practice (captured as leadership in the domain social and professional). |

As a practice, when we do the acute exacerbation we're pretty much focus on the acute exacerbation. GP4 I refer a few to pulmonary rehab but I don’t do as many as I feel I should. PN7 She was more receptive because she’d had a few flares up, not after the first one but because she’s had a few. And I think that makes them more receptive to doing that sort of thing. ANP4 One hand I’m wanting them to engage with the disease process so that actually they’ve got more skills to self-manage and that’s going to actually keep them much better for the rest if their whole of their life, on the other hand they don’t want to be classified as ill. ANP1 It would help me in trying to find out why she didn’t go because I would challenge her on it and try and get her to go again and give it another go and that would help me in. ANP4 |

|

12. Intentions (A conscious decision to perform a behaviour or a resolve to act in a certain way) |

39 | Some PHCPs have described adopting patient-aimed strategies that included persistence and warnings against over-reliance and/or possible reduced effectiveness of pharmacological treatments in an effort to move patients to a state ready for PR referral. There also appeared to be an understanding that acceptance for many patients takes time. |

I said you know you’ve used those rescue packs a lot you know if we could get your breathing a bit better, perhaps you wouldn’t be so bad…., and she said, alright then I’ll see, do the referral. ANP4 How would you feel about something that’s not medicine based but will probably help you as much as the inhalers that we’ve put you on, she was suddenly very interested in. GP4 I look for that chink of interest and then I’ll try and worm my way in then. PN7 He was very adamant that he didn’t want to go, then I gave him the booklet. PN5 |

|

13. Emotion (A complex reaction pattern, involving experiential, behavioural, and physiological elements, by which the individual attempts to deal with a personally significant matter or event) |

6 | PHCPs emotion was rarely discussed although some said they felt annoyed with providers if a referral had been rejected. There were high levels of empathy towards patients particularly among nurses; a small number described not wanting to offer the hope of PR to patients and for PR providers to reject referral, this appeared to be a particular concern for patients with high disease burden. |

Most of our patients are reasonably trusting and say well you seem quite excited by it so shall we give it a try. GP4 They’re gonna meet all these people they don’t know and be told to lift this walk here, do that and they’re frightened, its…I’d be terrified. PN5 I just don’t want to raise–if you raise patients’ hopes and say – and offer it, then it can make them–you know, if they’re already depressed because of the COPD, it could just make the depression worse you know, so I don’t want to impact on their mental wellbeing. ANP1 |

|

14. Behavioural regulation (Anything aimed at managing or changing objectively observed or measured actions) |

4 | Some PHCPs saw events such as hospital admissions/out-patient appointments as good opportunities for patients to change behaviours but for staff in those settings to instigate referral. PHCP personal behavioural regulation was low, many did not know how any they had referred or what, post referral, the patient’s journey had become. One participant described the research interview as helpful in allowing them to consider how to change their referral approach, but most PHCPs did not vocalise intentions to change or modify current or future PR referral behaviours. |

I don’t know how much is done in secondary care, but very often when stuff, when you’ve been in anywhere near secondary care people really its often quite a sit up moment, gosh this is serious enough for me to have to go to hospital, even if it an outpatient appointment. ANP1 This is one of your treatment choices’ and perhaps I need to change, thinking about it, my approach in–er, how I word it. ANP4 It’s trying to make it a priority. ANP4 |

ANP, advanced nurse practitioner; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GP, general practitioner; HCA, healthcare assistant; PHCP, primary healthcare practitioner; PN, practice nurse; PR, pulmonary rehabilitation; QoF, quaility outcomes framework.

Phase 2: questionnaire results—referral practice beliefs

Table 4 presents the number and proportion of PHCPs that agreed or strongly agreed with each belief statement by frequency of referral.

Table 4.

Results of TDF belief statements by referral frequency

| TDF domain | TDF questions (n=54) | Frequent referral n=109 (%) (weekly/monthly) |

Infrequent referral n=113 (%) (>monthly or no referral) |

Total n=222(%) |

| 1. Knowledge | I am aware of the content of PR programmes* | 97/109 (89.0) | 72/113 (63.7) | 169/222 (76.1) |

| I am aware of PR programme objectives.* | 99/109 (90.8) | 75/113 (66.4) | 174/222 (78.4) | |

| I am unsure of the evidence base for PR | 18/109 (16.5) | 30/113 (26.5) | 49/222 (21.6) | |

| I know where geographically my local PR programme is delivered* | 92/109 (84.4) | 70/113 (61.9) | 162/222 (73.0) | |

| I know when it is appropriate to refer a patient with COPD to PR* | 106/109 (97.3) | 74/113 (65.5) | 180/222 (81.1) | |

| I can answer questions patients have about PR* | 88/109 (80.7) | 60/113 (53.1) | 148/222 (66.7) | |

| I know how to contact my local PR provider* | 91/109 (83.2) | 68/113 (60.2) | 159/222 (71.6) | |

| 2. Skill | It is easy to refer a patient to PR* | 87/109 (80.0) | 48/113 (42.5) | 135/222 (60.8) |

| 3. Social and professional role | Referral to PR is the practice nurse role | 63/109 (57.8) | 45/113 (39.8) | 108/222 (48.6) |

| Other general practice staff in my practice (excluding practice nurse) refer patients to PR | 52/109 (47.7) | 63/113 (55.8) | 115/222 (51.8) | |

| I believe in encouraging patients to attend PR | 109/109 (100) | 104/112 (92.9) | 213/221 (96.4) | |

| 4. Environment | Resources about PR (ie, written information) are readily available | 39/109 (35.7) | 25/112 (22.3) | 64/221 (29.0) |

| There is not enough time in practice to refer | 12/109 (11.0) | 22/113 (19.5) | 34/222 (15.3) | |

| 5. Social influences | My local PR providers regularly engage with me | 31/109 (28.4) | 17/113 (15.0) | 48/222 (22.6) |

| PR is something that patients ask for | 3/109 (2.8) | 8/112 (7.1) | 11/221 (5.0) | |

| There are good relationships in practice with PR providers | 44/109 (40.4) | 28/112 (25.0) | 72/221 (32.6) | |

| PR providers are good at communicating outcomes of referrals I have made | 39/109 (35.8) | 25/112 (22.3) | 64/221 (29.0) | |

| 6. Optimism (including pessimism) | I am confident my local PR provider offers a good service for my patients* | 81/109 (74.3) | 52/113 (46.0) | 135/222 (60.8) |

| I don’t believe patients will attend PR after I have referred | 16/109 (14.7) | 16/113 (14.2) | 32/222 (14.4) | |

| Patients who smoke are not motivated to take part in PR | 7/109 (6.4) | 7/113 (6.2) | 14/222 (6.3) | |

| Patients who live alone won’t like to take part in group PR | 5/109 (4.6) | 2/113 (1.8) | 7/222 (3.2) | |

| Patients are motivated to attend PR | 23/109 (21.6) | 30/111 (27.0) | 53/219 (24.2) | |

| 7. Belief about capabilities (self) | I am confident in my ability to encourage patients to attend PR, even when they are not motivated | 91/109 (83.5) | 73/113 (67.6) | 164/222 (73.9) |

| I do not find it easy to discuss PR with patients | 8/109 (7.3) | 25/113 (22.1) | 36/222 (16.2) | |

| Belief about capabilities (patients) | Patients without their own transport won’t be able to get to PR | 40/109 (36.7) | 26/113 (23.0) | 66/222 (29.7) |

| Patients in work are not able to attend PR* | 62/109 (56.9) | 35/113 (31.0) | 97/222 (43.7) | |

| Patients who use home oxygen are unable to take part in PR | 4/109 (3.7) | 6/113 (5.3) | 10/222 (4.5) | |

| 8. Belief about consequences | If I keep pushing patients to attend PR this will disadvantage my relationship with them. | 10/109 (9.2) | 10/112 (8.9) | 20/221 (9.0) |

| I believe patients may be harmed by taking part In PR | 1/109 (0.9) | 1/113 (0.9) | 2/222 (0.9) | |

| I believe most patients will attend and complete PR following my referral | 55/109 (50.4) | 47/112 (42.0) | 102/221 (46.2) | |

| PR is not beneficial to patients who are breathless | 3/109 (2.8) | 3/113 (2.7) | 6/222 (2.7) | |

| PR is best suited to those patients with worsening breathlessness | 29/109 (26.6) | 29/112 (25.9) | 58/221 (26.2) | |

| PR is best suited to those who have frequent exacerbations | 27/109 (24.8) | 28/112 (25.0) | 55/221 (24.9) | |

| PR reduces hospital admissions | 101/109 (92.7) | 97/112 (86.6) | 198/221 (89.6) | |

| PR reduces risk of mortality | 85/109 (78.0) | 82/112 (73.2) | 167/221 (75.6) | |

| If patients attend PR this will reduce their general practice visits | 73/109 (67.0) | 78/112 (69.6) | 151/221 (68.3) | |

| PR reduces exacerbations | 88/109 (80.7) | 84/112 (75.0) | 172/221 (77.8) | |

| PR improves breathlessness | 103/109 (94.5) | 100/112 (89.3) | 203/221 (91.9) | |

| PR reduces a patient’s anxiety and/or depression. | 97/108 (89.8) | 96/112 (85.7) | 193/220 (87.7) | |

| 9.Goals | Referring patients to PR is something I have been advised to do* | 95/107 (88.8) | 57/112 (50.9) | 152/219 (69.4) |

| My practice regularly reviews COPD registers to ensure eligible patients with COPD are offered PR | 51/109 (46.8) | 40/113 (35.4) | 91/222 (41.0) | |

| There are set targets within the practice to improve PR referral rates | 23/109 (21.1) | 21/113 (18.6) | 44/222 (19.8) | |

| 10. Memory (Inc. decision-making) | I often forget to refer patients with COPD to PR | 3/109 (2.8) | 23/113 (20.4) | 26/222 (11.7) |

| Prompts to refer patients to PR within annual review templates are important reminders for me | 72/109 (66.1) | 69/112 (61.6) | 141/221 (63.8) | |

| I only refer patients if they have quit smoking | 1/109 (0.9) | 3/113 (2.7) | 4/222 (1.8) | |

| I only refer patients if they are optimised on their respiratory medication | 17/109 (15.6) | 12/113 (10.6) | 29/222 (13.1) | |

| PR is most suited to patients with COPD who have frequent exacerbations | 20/109 (18.3) | 20/113 (17.7) | 40/221 (18.1) | |

| The best time to discuss PR referral with patients is when they are stable | 32/109 (29.4) | 25/112 (22.3) | 57/221 (25.8) | |

| 11. Reinforcement | More healthcare practitioners will discuss PR with patients because of the QoF incentive | 75/109 (68.8) | 73/112 (65.2) | 148/221 (67.0) |

| My practice receives financial incentives for referral to PR (before April 2019) | 6/108 (5.6) | 5/113 (4.4) | 11/221 (5.0) | |

| I believe patient attendance to PR will increase because of the QoF incentive | 41/109 (37.6) | 58/112 (51.8) | 99/221 (44.8) | |

| I believe the QoF incentive will not increase patients PR attendance | 29/109 (26.6) | 25/112 (2.3) | 54/221 (24.4) | |

| There will be greater awareness of PR within practices because of the new QoF incentives | 84/109 (77.1) | 71/112 (63.4) | 155/221 (70.1) | |

| 12. Intentions | I will refer more patients to PR now there are practice QoF incentives (from April 2019) | 30/109 (27.5) | 42/112 (37.5) | 72/221 (32.6) |

*Differences in results of >20% between frequent and infrequent referrer.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PR, pulmonary rehabilitation; TDF, Theoretical Domains Framework.

In general, most PHCPs had some PR knowledge (especially the frequent referrers) and understood the beneficial consequences of PR. However, resources, social influences (such as relationship with PR providers) and pessimism about patient motivations were perceived barriers by a high proportion of PHCPs, irrespective of their referral practice.

There were however, differences in domains between frequent and infrequent PR referrers.

The greatest differences were within the ‘Knowledge’ domain. Frequent referrers most commonly reported agreement with all seven statements, when compared with the infrequent referrers. For example, 97.3% reported knowing when to refer to PR and 80.7% being able to answer patients’ questions versus 65.5% and 53.1% of infrequent referrers.

Further group differences were demonstrated in the ‘Skills’ domain and ‘Beliefs about (PHCP) capabilities’, which showed that infrequent referrers were less confident in encouraging unmotivated patients to attend PR (67.6% vs 83.5% of frequent referrers). Reduced confidence among infrequent referrers was further reflected within the ‘Optimism’ domain and belief statement ‘I am confident my local provider offers a good service’ (46% against 74.3% of frequent referrers). However, over half (56.9%) of frequent referrers felt that patients in work were not able to attend PR, compared with less than a third (31%) of those who referred infrequently.

The remaining belief statements demonstrated greater group similarities than differences.

Environment, social and professional role

Most respondents felt that there was enough time in practice to refer (84.7%) and believed in encouraging PR attendance (96.4%). Yet promotional information on PR was rarely available in practices (29%). There was no clearly identified PR referrer; less than half (48.6%) felt it was the practice nurse’s role and (51.8%) reported other practice staff refer.

Social influences

Frequent referrers were slightly more likely to agree with three of the four domain belief statements than infrequent referrers. Although, collectively the groups reported both PR provider engagement and referral outcome reporting as low at only 22.6% and 29%, respectively. PHCPs also reported patients rarely request referral to PR (5%).

Belief about consequences and optimism

Most PHCPs agreed that PR offers physical health benefits, including improving breathlessness and reducing hospital admissions (91.9%, 89.6%), respectively. Yet far fewer PHCPs believed patients would attend and complete PR (46.2%), with fewer still agreeing that patients are PR motivated (24.2%).

Memory (decision-making)

Only a small number of PHCPs reported forgetting to refer patients to PR (11.7%). COPD annual review templates were reported as helpful referral reminders (63.8%) and 25.8% reported the best time to discuss referral with patients was during COPD stability. Patient characteristics such as disease stability and smoking status do not appear to impede PHCP referral decisions as 98.2% reported referring smokers.

Goals, reinforcement and intention

In-practice review of eligible patients was not commonly reported (41%) and only 19.8% reported in-practice targets to improve referral rates. Practice financial reward for referral (pre April 2019) was rarely reported (5%); indeed the implementation of financial reward via national QoF incentives (post April 2019) was considered unlikely to greatly improve referral behaviours, with less than a third (32.6%) stating they would refer more. However, there was general agreement that this incentive would increase practice awareness of PR (70.1%).

Phase 2: questionnaire—open questions

A third of PHCPs (33.8%) responded to the open question at the end of the survey including 5/11 PHCPs who reported referral, but did not specify frequency (answer length 3–167 words, mean 35). Non-frequent referrers reported more open comments (43/113, 38.1%) than frequent referrers (33/109, 30.3%).

This gave an additional 94 comments that related directly to PR referral. These were content mapped to all 12 relevant TDF domains. The comments predominately cited referral barriers.

Belief about capabilities had the highest number of comments 36/94 (38.3%) with many encompassing concerns about PR accessibility, particularly transport challenges for patients. For example, ‘Location of PR too far for patients to travel and too much commitment. Patients tend to be older adults on generally low incomes. A number of my patients would attend if it was close by with no expense’. A small number of PHCPs (3.2%) considered a patient’s inability to complete pre-PR spirometry as a referral barrier, and 10.6% of comments related to referral processes, which were reported to be lengthy and as such ‘easier simpler’ processes were requested.

Connected results

In order to identify the key factors that inhibit and/or enable PHCP referral to PR, Phase 1 and phase 2 results were merged to allow for data contrast and meta-inference16 (table 5).

Table 5.

Matrix of integrated results

| TDF domain | Phase 1: qualitative study main factors | Phase 2: survey main factors | Barrier—✗/Enabler—✓ |

| Social and professional role | It is largely seen as the practice nurse role, or staff undertaking COPD review The best time to refer a patient is when they are stable Most PHCPs believe in encouraging patients to attend |

Not clearly PNs role, but PHCP doing annual review is most likely referrer Disagree Agree |

PHCP undertaking annual review (not necessarily the PN)—✓ Not generalisable in quantitative data ✓ |

| Knowledge | Generally a good basic knowledge Little detailed local programme knowledge Knowledge is largely gained from CPD/networking |

Agree (generally higher in frequent referrers) Disagree (higher local knowledge in frequent referrers) Agree |

Enabler—but room for improvement ✓ ✓ |

| Environment | There is a lack of time in practice Referral is only considered during non-acute COPD focused consultations There is a lack of PR promotional material available in practices |

Disagree Agreed (some infrequent referrers reported not to see patients with COPD) Agree |

Not generalisable in the quantitative data ✗ ✗ |

| Memory | On screen reminders are important Referral prompted when patients have symptoms that are worsening |

Agree Disagree |

✓ Not generalisable in the quantitative data |

| Optimism | Patients do not want PR/are not motivated PR providers do not offer a good service |

Agree Some agreement more so with infrequent referrers |

✗ ✗ |

| Belief about consequences | PR is good for patient’s physical and psychological health PR may harm patients (psychologically) Pushing PR might harm my relationship Patients will not always attend and complete post referral |

Agree Disagree Disagree General agreement |

✓ Not generalisable in the quantitative data Not generalisable in the quantitative data ✗ |

| Belief about capability | Talking to patients about PR is challenging Patients in work are unable to attend PR Transport is a barrier Not for patients with oxygen Not for patients who smoke Best suited to those who have frequent exacerbations |

Some agreement more so with infrequent referrers Agree Agree (open question) Disagree Disagree Disagree |

✗ ✗ ✗ Not generalisable in the quantitative data Not generalisable in the quantitative data Not generalisable in the quantitative data |

| Social influences | Lack of PR provider engagement and feedback to referrer Patients do not ask for PR |

Agree Agree |

✗ ✗ |

| Skills | Referral to PR by PHCP is low Referral process is relatively easy |

Agree Disagreement, particularly by infrequent referrers |

✗ Likely barrier |

| Reinforcement | Financial reward increases referral rates Patients decline PR Financial reward increases practice awareness |

Most do not think this would change behaviour Not captured explicitly Agree |

Not generalisable in the quantitative data Likely barrier ✓ |

| Goals | No set in-practice process to improve or review referral rates. | Agree | ✗ |

| Intentions | Referral acceptance takes time General desire to refer more patients |

Not captured explicitly Not captured explicitly |

Likely barrier Likely enabler |

| Emotion | PHCPs are fearful on behalf of patients Frustration with PR providers |

Concern over access abilities (expressed in free text, may capture PHCP fear) Not captured explicitly |

✗ ✗ |

| Behavioural regulation | PHCPs do not know how many patients they have referred PHCPs have no planned intentions to change behaviour |

Agree Largely agree, although some emerging interventions (free text) |

✗ Likely barrier |

✗Barrier and agreement with Phase 1 data.

✓Enabler and agreement with Phase 1 data.

COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPD, continuous practice development; PHCPs, primary healthcare practitioners; PN, practice nurse; PR, pulmonary rehabilitation.

Most PHCPs believed in PR and encouraged patients to attend. Referral is most likely to be considered at annual review (indeed referral is rarely offered to patients outside of this consultation). On-screen prompts are helpful reminders, but in practice material promoting PR is rare. PHCP PR knowledge is largely gained from networking with other respiratory interested health professionals and/or CPD education. PHCPs report patients have little motivation for PR, rarely ask for referral to PR and view that patients in work are unlikely to be able to attend.

Some findings of the qualitative study were not clearly replicated in the survey results. For example, phase one qualitative data highlighted that some GPs and ANPs felt the practice nurse was best placed to undertake PR referral at the time of annual review, yet respiratory interested GPs and those undertaking annual review did not share this view. The phase 2 survey data supported the latter position, where 29 (22.5%)/129 of practice nurses reported never referring. Therefore responsibility of PR referral is not based on profession, but is undertaken by PHCPs who are respiratory interested and/or conducting the patient’s annual review.

Qualitative generalisable findings were limited in a number of areas meaning clear conclusion cannot be drawn, these included; time available to undertake referral, ease of referral process, perceptions of quality of PR programme, referral of patients when COPD symptom burden is increasing and non-referral in order to protect patient relationship.

Where generalisability is clear, a summary of the key behavioural barriers and enablers by TDF domain is shown in table 5, demonstrating a greater number of barriers than enablers to referral. However, it is also important to report that barriers and enablers most commonly coexist within the same domains.

Discussion

This is the first time the TDF has been applied to a mixed-methods study to understand the key factors that determine referral to PR by PHCPs.

Results highlighted multiple intertwined barriers and few enablers across all TDF domains. Many (although not all) of the findings from the qualitative study were affirmed by the more generalisable survey and highlight that referral to PR from primary care remains poor, and that PHCPs believed that PR was beneficial for patients and wanted to refer more. They did however, request greater engagement from providers, better knowledge of local programmes and improvements in PR promotion. They also reported that in-practice goals and monitoring of referrals to address the shortfall in patients referred were rare.

However, PHCPs collectively reported low confidence in patients’ abilities and motivations to attend PR, a belief likely to be strengthened by reports of few patients requesting referral. Beliefs about low uptake may explain why referral is commonly offered at times of increasing COPD symptoms, thus acting as a lever to referral acceptance. Infrequent referrers reported reduced confidence in encouraging unmotivated patients to attend, with similar findings reported in phase 1 data as PHCPs expressed concerns around the protection of relationships with patients. Venue accessibility also appears to be a barrier and while the direct survey question (question 21) appeared not to overtly agree with this, both phase 1 and the phase 2 open question results highlighted transport as both a practical and financial barrier.

Variability in referral rate by PHCP profession was an unexpected finding and offers insights that (1) few PNs refer and (2) where it is considered to be the ‘respiratory nurse’ role, referral opportunities may become reduced. The association between referral frequency and respiratory qualification is also a new finding. ANPs were those most likely to refer and to have respiratory qualifications.

Relation to other studies

This mixed-methods TDF-based study finds agreement with many key referral factors presented in our previous inductive qualitative study using the same data6 and Cox et al’s25 TDF-applied systematic review which included patients and HCPs views on PR barriers and enablers. However, this primary mixed-methods study reports additional findings. It disputes that the PN is the main referrer to PR within primary care, and questions the value of practice-based financial reward as a referral incentive. It also highlights that the referral process itself is not straightforward and there are no sanctions for non-referral, but that there is time in practice to refer.

Increasing the population sample and geographical reach in this study strengthens current known referral barriers including, poor patient motivation, few in-practice resources, perceived venue access difficulties and little awareness of local PR provision.26–29 Subjective patient assessments including PHCPs perceptions of patients capabilities and motivations have been described as influencing PHCP referral decisions here and previously published.6 This is a novel finding in relation to PR referral, yet similar HCP pessimistic attitudes, relating to a patient’s capability and motivation to access services and change behaviours to improve health outcomes have been reported in the primary healthcare management of reducing cardiovascular disease risk in people with serious mental illness.30 31

Phase 1 and inductive data analysis6 suggested that offering PR at COPD symptom increase was common yet this was unconfirmed in the survey results. This may demonstrate further social desirability reporting as previous analyses have demonstrated patients attending PR to have 1.24 hospitalisations per patient-year (95% CI: 0.66 to 2.34) suggesting sicker patients are those most likely to be offered PR.32 However, referral at this time supports both PHCP and patients’ concerns about patient’s capabilities,6 25 33 meaning lower acceptance and adherence to PR is probable, and negative PHCP beliefs about referral outcomes are likely to perpetuate. An alternative approach and one that appears not to be currently undertaken is to refer at the point of an acute exacerbation of COPD, which maybe a referral lever.33

In our original inductive analysis,6 we reported that financial incentives may be important, yet results in this current study are mixed and PHCPs appear uncertain of their value. It will be interesting to observe the impact of the newly implemented financial rewards for PR referral in England, but where similar practice based quality outcome framework (QoF) rewards were implemented for referral to diabetes programmes, uptake did not greatly improve.34 Given positive correlations between referral rates and CPD education, efforts to increase the number and education of the primary care workforce by Health Education England35 36 is encouraging.

The literature also supports a general consensus that for patients in employment, PR is largely considered inaccessible.6 28 This was reported as a barrier by the frequent referrers more than the infrequent referrers, which questions whether PR knowledge itself is a potential barrier as previously reported6 and that PHCP beliefs influence subsequent referral behaviours.

Strengths and limitations

Using the previously published qualitative data to inform the questionnaire offered valuable insights into PHCP referral practices and is a key strength of this research.

The range and number of PHCPs included from across the UK were broadly representative of the general practice nursing workforce, while less so for others, notably doctors and is a limitation.37 We recognise that predominately respiratory interested participants may have taken part in this study which may skew results, and it is noted that online participants reported higher referral practice and respiratory qualification(s) than their counterparts, which may be a study limitation, suggesting that more emphasis should be placed on the perspective of the infrequent referrers. Adopting additional recruitment strategies such as via general practice-based conferences is seen as a study strength which sought to capture a range of PHCPs’ views. Demographic similarities across all three recruitment streams highlight study design attempts to reduce participation and sample selection biases. Questionnaire-specific biases relating to self-reporting response is a source of potential weakness, specifically where responses maybe perceived to be ‘socially acceptable’, otherwise known as social desirability.38 This may offer some explanation around the variation observed in the belief about capabilities domain of the integrated results matrix (table 5). Grouping participants by reported referral frequency is a study strength, particularly as the aim is to understand both what supports and inhibits referral. Another limitation is that we are not sure about exact response rates where distribution was unknown.

Much of the validity of the TDF is gained from its direct application with HCPs, as utilised here. Transcript content mapping to 84 constructs is complex and time consuming as also described by others39 but was considered the most comprehensive approach in the absence of a gold standard approach to TDF application.39 The TDF offers a functional approach to behavioural data analysis, most likely to be helpful when there is little to no underlying knowledge of the investigating phenomenon. However, the inter-relations between referrer, patient and provider have previously been reported to be important factors in the referral journey.6 Yet, the TDF does not offer causal determinants of behaviour20 and alignment to predetermined domains reduces the ability to consider any phenomena falling outside those domains and the likely connecting relations, meaning the whole picture maybe missed and is a potential limitation.

All authors had different professional backgrounds, one of whom (JSW) is an experienced respiratory nurse specialist which may have altered data analysis although transparency and frequent team analysis sought to reduce potential bias.

Implications for policy and practice

While this paper highlights multiple barriers in referring patients with COPD to PR, barriers to high-quality healthcare for patients with COPD span throughout the disease trajectory and persist across health service provisions worldwide.40–42 It is interesting to note that few participants in our study thought that a financial incentive was important. It is however difficult to assess this given that face-to-face PR programmes were suspended across the country as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, as previously highlighted QoF incentives for referral to diabetes programmes did not greatly improve uptake. What we need to do now is to design and test an intervention for improving referral to PR which incorporates multisystem level changes. Additional intervention considerations will also need to include post COVID-19 infection control adaptations, as well as managing increases in service demands arising from programme suspension backlogs and new referrals, including COVID-19 survivors.43

Conclusions

This is the first mixed-methods research study to examine the factors that inhibit and enable referral to PR for patients with COPD from a primary care perspective. While knowledge and respiratory qualification appear to be enablers, many barriers persist which must be overcome to increase referral opportunities for all eligible patients. The most important aspects to address are to increase PR provider engagement with referrers, increase PR awareness and support for potential patients and all PHCPs, including those with respiratory qualifications and to increase PHCP internal motivation for PR referral, particularly for those patients in work and those with less symptom burden. Mapping these TDF findings to behaviour change techniques are important next steps which will enable clear targeted interventions to be identified and tested in clinical practice, which will ultimately increase referral to PR, thereby improving health outcomes of patients with COPD and reducing health service utilisation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participating primary healthcare practitioners for giving up their time, providing the data and contributing to this study.

Footnotes

Twitter: @Nurse_JSW

Contributors: JSW collected, analysed and interpreted phase 1 and phase 2 data and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. REJ, PA, SG and AE contributed to study design, data analysis and interpretation of phase 1 and 2 data. RJ, PA and SG all contributed to the writing of the manuscript. IV supported phase 1 topic guide development, phase 1 data alignment to the TDF and the formulation of the phase 2 questionnaire where behavioural expert consensus was sought. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. REJ accepts responsibility for this work and is the guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

The datasets during and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All data requests should be sent to R.E.Jordan@bham.ac.uk.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Phase 1 approval granted by Health Research Authority: Project ID: 213 367. Phase 2 approval granted by University of Birmingham: ERN_19–0439. All participants in phase 1 and phase 2 studies gave consent.

References

- 1.McCarthy B, Casey D, Devane D, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;3. 10.1002/14651858.CD003793.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Puhan MA, Gimeno-Santos E, Cates CJ, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation following exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;12:CD005305. 10.1002/14651858.CD005305.pub4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolton CE, Bevan-Smith EF, Blakey JD, et al. British thoracic Society guideline on pulmonary rehabilitation in adults. Thorax 2013;68 Suppl 2:ii1–30. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2013-203808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McNaughton A, Weatherall M, Williams G, et al. An audit of pulmonary rehabilitation program. Clinical Audit 2016;8:7–12. 10.2147/CA.S111924 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steiner M HBJ, Lowe D, Searle L. Pulmonary rehabilitation: steps to breathe better. National chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) audit programme: clinical audit of pulmonary rehabilitation services in England and Wales 2015. London: RCP, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watson JS, Adab P, Jordan RE, et al. Referral of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease to pulmonary rehabilitation: a qualitative study of barriers and enablers for primary healthcare practitioners. Br J Gen Pract 2020;70:e274–84. 10.3399/bjgp20X708101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colquhoun HL, Squires JE, Kolehmainen N, et al. Methods for designing interventions to change healthcare professionals' behaviour: a systematic review. Implement Sci 2017;12:30. 10.1186/s13012-017-0560-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis R, Campbell R, Hildon Z, et al. Theories of behaviour and behaviour change across the social and behavioural sciences: a scoping review. Health Psychol Rev 2015;9:323–44. 10.1080/17437199.2014.941722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Birken SA, Powell BJ, Shea CM, et al. Criteria for selecting implementation science theories and frameworks: results from an international survey. Implement Sci 2017;12:124. 10.1186/s13012-017-0656-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cane J, O'Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci 2012;7:37. 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci 2015;10:53. 10.1186/s13012-015-0242-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, et al. From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Appl Psychol 2008;57:660–80. 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2008.00341.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Phillips CJ, Marshall AP, Chaves NJ, et al. Experiences of using the theoretical domains framework across diverse clinical environments: a qualitative study. J Multidiscip Healthc 2015;8:139–46. 10.2147/JMDH.S78458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dyson J, Lawton R, Jackson C, et al. Development of a theory-based instrument to identify barriers and levers to best hand hygiene practice among healthcare practitioners. Implement Sci 2013;8:111. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res 2013;48:2134–56. 10.1111/1475-6773.12117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Creswell J, Clark P. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. 2nd ed. London: SAGE, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:42. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Atkins L, Hunkeler EM, Jensen CD, et al. Factors influencing variation in physician adenoma detection rates: a theory-based approach for performance improvement. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:617–26. 10.1016/j.gie.2015.08.075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, et al. A guide to using the theoretical domains framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci 2017;12:77. 10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Online survey JISC . Online survey (formerly Bos). Bristol UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 22.O'Cathain A, Thomas KJ. "Any other comments?" Open questions on questionnaires - a bane or a bonus to research? BMC Med Res Methodol 2004;4:25. 10.1186/1471-2288-4-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weijters B, Cabooter E, Schillewaert N. The effect of rating scale format on response styles: the number of response categories and response category labels. International Journal of Research in Marketing 2010;27:236–47. 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2010.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Braun V, Clarke V. Successful qualitative research: a practical guide for beginners. 1st edn. London: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cox NS, Oliveira CC, Lahham A, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation referral and participation are commonly influenced by environment, knowledge, and beliefs about consequences: a systematic review using the theoretical domains framework. J Physiother 2017;63:84–93. 10.1016/j.jphys.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harris D, Hayter M, Allender S. Improving the uptake of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD: qualitative study of experiences and attitudes. Br J Gen Pract 2008;58:703–10. 10.3399/bjgp08X342363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Foster F, Piggott R, Riley L, et al. Working with primary care clinicians and patients to introduce strategies for increasing referrals for pulmonary rehabilitation. Prim Health Care Res Dev 2016;17:226–37. 10.1017/S1463423615000286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Molin KR, Egerod I, Valentiner LS, et al. General practitioners' perceptions of COPD treatment: thematic analysis of qualitative interviews. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2016;11:1929–37. 10.2147/COPD.S108611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Johnston KN, Young M, Grimmer KA, et al. Barriers to, and facilitators for, referral to pulmonary rehabilitation in COPD patients from the perspective of Australian general practitioners: a qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J 2013;22:319–24. 10.4104/pcrj.2013.00062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burton A, Osborn D, Atkins L, et al. Lowering cardiovascular disease risk for people with severe mental illnesses in primary care: a focus group study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0136603. 10.1371/journal.pone.0136603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hassan S, Ross J, Marston L, et al. A primary care-led intervention to reduce cardiovascular disease risk in people with severe mental illness (primrose): a secondary qualitative analysis. The Lancet 2019;394:S50. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32847-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moore E, Palmer T, Newson R, et al. Pulmonary rehabilitation as a mechanism to reduce hospitalizations for acute exacerbations of COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 2016;150:837–59. 10.1016/j.chest.2016.05.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moore L, Hogg L, White P. Acceptability and feasibility of pulmonary rehabilitation for COPD: a community qualitative study. Prim Care Respir J 2012;21:419–24. 10.4104/pcrj.2012.00086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Health & Social Care Information Centre HQIPDU . National diabetes audit 2013-2014 and 2014-2015. Report 1: care processes and treatment targets, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rowland M. The future of primary care: creating teams for tomorrow. Health Education England: Primary Care Workforce Commission, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Practitioners RCoG, Skills for Health . Skills for health. core capabilities framework for advanced clinical practice (nurses) working in general practice / primary care in England, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Primary Care Workforce Team ND . General practice workforce 31 December 2019. Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fisher RJ. Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect Questioning. J Consum Res 1993;20:303–15. 10.1086/209351 [DOI] [Google Scholar]