Abstract

Introduction

Psoriasis (Pso) is a common, immune-mediated, chronic-relapsing, inflammatory skin disease. While a great deal is known about Pso and its treatment, there remain several treatment scenarios unaddressed by clinical studies. To be effective, treatment for Pso must alter the activity of one or more immunological pathways important in the pathogenesis of the disease. While the benefit of blocking these pathways may be apparent, there remain uncertainties regarding safety, such as infections, malignancies, and the potential for off-target effects. Existing guidelines and treatment recommendations rely primarily on clinical trial or observational data, none of which adequately address specific clinical challenges. This document describes a methodological framework for generating practical and clinically relevant guidance for situations where direct evidence is rare or absent. Guidelines implementing this framework are currently ongoing.

Methods

We develop a knowledge synthesis approach to guideline development, utilizing clinical trial data where available, and a formalized inferential decision-making process that considers indirect data coupled with structured expert opinion and analysis. This approach is best suited for situations where direct, high-level evidence is lacking. Support for each resultant recommendation is expressed as a quantified assessment of confidence.

Results

The topics to be addressed by this set of guidelines are ranked by clinicians and patients as areas of concern, with an emphasis on topics where high-level evidence may have limited availability.

Conclusion

Through this novel approach, we will derive practical, informative recommendations using the best evidence available in combination with structured expert opinion to guide best practices in complex, real-world settings.

Supplementary file2 (MP4 98653 kb)

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-021-00642-5.

Keywords: Psoriasis, Guidelines, Inference, Expert elicitation

Plain Language Summary

Clinical guidelines aim to assist doctors in managing their patients’ medical conditions. A limitation of current guidelines is that they are frequently based on randomized clinical research trials—often considered the gold standard in medical research. Clinical trials are designed to estimate the safety and effectiveness of treatment. Outside of clinical trials, doctors encounter a range of patient cases excluded from clinical trials. Our group aims to create guidelines for those clinical scenarios not adequately addressed by clinical trials. Examples include patients excluded from clinical trials, the elderly, patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and pregnant or breastfeeding women. When clinical trial data is limited, doctors must make decisions nonetheless. In certain clinical situations they are left to their own resources to consult with experts, review the data, and make inferences based on the limited data available. Instead of concluding that there is no data, the topic of interest can be broken down into components that are answerable by different types of research studies. This inference-based approach uses expert opinion and indirect evidence to support an inference-based position on topics where direct clinical data is sparse or insufficient to answer the question. This approach can be used as a complement to clinical trial data informing disease management guidelines.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-021-00642-5.

Key Summary Points

| While a great deal is known about Pso and its treatment, there remain several treatment scenarios unaddressed by clinical studies and uncertainties regarding safety, such as infections, malignancies, and the potential for off-target effects. |

| Clinical decisions must be made despite limitations of clinical trial data, and the need for current, practical, and sound assessment tools and therapeutic recommendations for patients with Pso is apparent. |

| Our group aims to define best practices in areas where direct, high-level evidence is lacking, through novel approaches that integrate structured expert opinions with analysis of existing data. |

| A formalized inference-based approach is introduced, which can be applied in clinical scenarios where there are no clinical trials, limited real world-data, and where prospective and retrospective studies are not possible or unlikely to be conducted. |

Digital Features

This article is published with digital features, including a video, to facilitate understanding of the article. To view digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.16912651.

Introduction

Psoriasis (Pso) is a multifaceted, chronic, inflammatory skin disease that continues to have a significant impact on patient quality of life. High global disease prevalence in adults, ranging between 0.09% and 11.43% depending on the country studied [1–3], magnifies the impact of Pso and the diversity of potential clinical scenarios. Presentations of Pso vary, manifesting in different areas of the body and with numerous morphologies. Comorbidities potentially associated with Pso include psoriatic arthritis, obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, hypertension, and coronary artery disease, each of which complicates disease management [4]. The emergence of new treatment options, the publication of treat-to-target algorithms [5–7], and treatment guidelines in Canada [8], the USA [9–12], Britain [13–15], and Europe [16, 17] provide some structure to the analysis and application of trial data in real-world settings, but do not address many fundamental, everyday concerns of patients and healthcare practitioners, thus leaving gaps in the management of Pso. Moreover, clinicians may not have the time or resources to address the methodological problems and limitations of clinical trials. Clinical decisions must be made despite limitations of clinical trial data, and the need for current, practical, and sound assessment tools and therapeutic recommendations for patients with Pso is apparent.

Using the principles of evidence-based medicine, we implement novel approaches to develop a series of practical guidelines. Evidence-based medicine is “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients” [18]. Clinical trials are designed to address specific questions regarding intervention efficacy and adverse events in well-defined populations using the principles of controlled, scientific experiments [18, 19]. Our group aims to define best practices in areas where direct, high-level evidence is lacking, through novel approaches that integrate structured expert opinions with analysis of existing data. This includes formalizing an inference-based approach applied to clinical scenarios excluded from clinical trials, having limited real world-data, and where prospective or retrospective studies are unlikely. Physicians and patients establish clinically relevant questions addressed using existing data and, when necessary, coupled with structured expert opinion. Guidelines implementing this approach are currently ongoing.

Guideline Governance

This project was initiated by the Dermatology Association of Ontario (DAO), and supported by other professional dermatology associations and patient organizations (Table 1). The DAO functions as the coordinating institution for the entirety of this initiative and is responsible for all governance, contracts, and financial accountability. Professional dermatology associations were recruited and consulted to assist in guideline review, endorsement, and dissemination. Professional and patient associations support survey dissemination, recruitment of special committee members, and addressing regional issues, as needed. Patient organizations also ensure that patient experiences and perspectives are represented, and that guidance follows a patient-centered approach. The organization is intended to be inclusive and flexible. Associations may support or provide oversight at their leisure. Committees are structured to be flexible, and include experts with specific expertise related to the topic of interest.

Table 1.

Supporting professional associations and patient organizations

| Provincial organizations | Patient organizations |

|---|---|

| Alberta Society of Dermatologists | Canadian Association of Psoriasis Patients |

| Atlantic Provinces Dermatology Association | Canadian Skin Patient Alliance |

| Association des médecins spécialistes dermatologues du Québec | |

| Dermatology Association of Ontario | |

| The Dermatologic Society of Manitoba | |

| Saskatchewan Dermatology Association |

Committee Structure and Roles

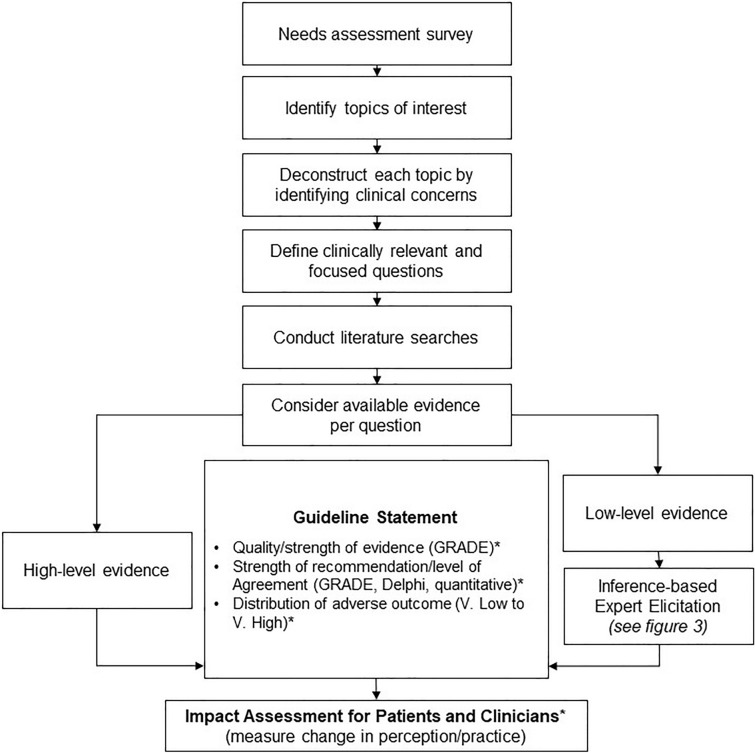

This guidelines initiative involves well-defined stakeholders, committees, subcommittees, and working groups that form and dissolve based on topics of interest (Fig. 1). Four members of the DAO were appointed to the steering committee (KAP, YP, MG, CWL). This committee identifies objectives, defines governance structure, and assists with selecting additional committee members who will contribute to this project. To form the general committee, members of the steering committee nominated dermatologists with established expertise in Pso to contribute to this initiative. Each candidate was assessed by the steering committee using a structured screening approach. Seven nominees (JB, JD, RG, CHH, MK, CM, RV) who met a minimum threshold were invited to apply for general committee membership by submitting their curriculum vitae, conflicts of interest, and a self-assessment form (Supplementary Appendix). The assessment considered clinical experience in treating Pso, peer-reviewed publications, and expertise in predefined areas, including clinical research, guideline development, statistics, and basic science.

Fig. 1.

Stakeholder, committee, subcommittee, and working group structure

The 11 members of the general committee are responsible for identifying topics of clinical interest based on results from needs assessments of the dermatology community. The general committee also guides the structured approach to assessing questions of clinical interest, nominates and selects special committee members, and participates in research or data reviews. Financial and status reports are regularly submitted to all supporting professional associations. Members of the general committee support four subcommittees to distribute workload and ensure the interests of different stakeholders are well represented. These committees oversee various processes throughout the generation, dissemination, and amendment phases of guideline development, according to their mandate as outlined in Table 2. For example, the legacy processes and updates subcommittee will consider the feasibility of incorporating living guidelines and reviews [20].

Table 2.

Subcommittee titles and responsibilities

| Subcommittee title | Mandate |

|---|---|

| Patient audience subcommittee | Develop/recommend communication tools conveying the committee’s results to patients |

| Clinician engagement subcommittee | Develop/recommend communication tools presenting the committee’s results to clinicians |

| Process, method, and general communication subcommittee | Develop/recommend communication tools on process, methodology, and general communication |

| Legacy processes and updates subcommittee | Develop legacy processes to readily incorporate new information within the framework of these guidelines |

For each guideline topic, a working group is formed consisting of general committee and invited special committee members. These invited members are national or international delegates having expertise in the topic of interest, and participate in the development of publications in areas requiring specific expertise. All members are invited to provide their CVs, detail their experience with the topic of interest, and complete a conflict of interest (COI) declaration related to the topic. To further mitigate conflicts of interest for each outcome being assessed, authors will be invited to self-reflect on material, personal, political, or academic gain by participating in this guideline initiative. For the resultant peer-reviewed manuscript(s) associated with each topic, authorship is determined by contributions using a matrix to score contributions.

Mitigation of Competing Interests

Development of these guidelines is supported by unrestricted educational grants from pharmaceutical and cosmetic companies offering products to treat Pso. Funding sponsors do not participate in the development or approval of guidelines. None of the panel members will receive honoraria for their contributions to this work.

Defining Priority Topics

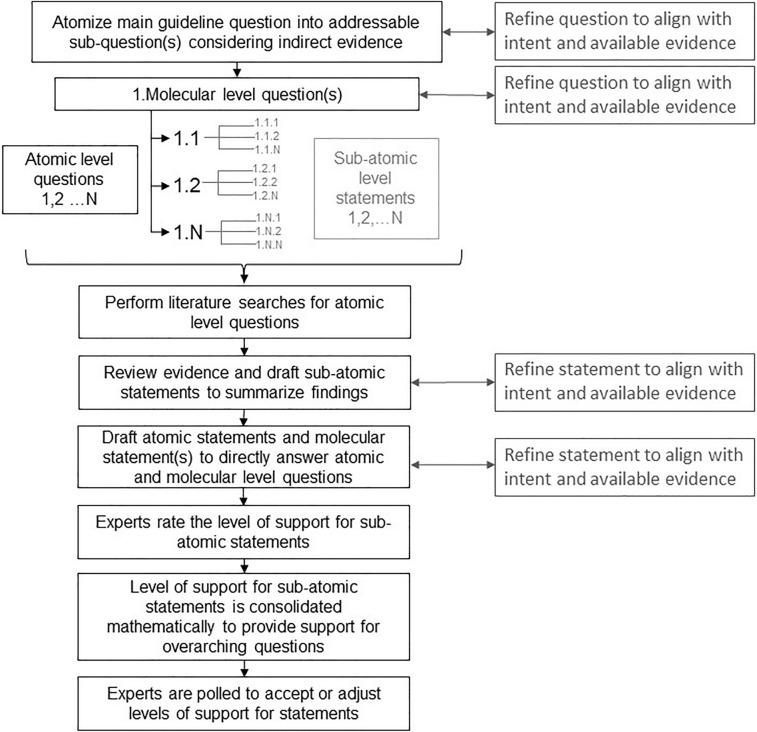

To ensure high standards of guideline development, the AGREE II instrument [21] will be consulted during the guideline development process. The proposed guideline framework (Fig. 2) begins with a needs assessment surveys of patients with Pso, and national and international dermatologists who are experts in the field of Pso are polled to generate topics of clinical interest. The first online needs assessment survey was circulated to 900 national and international dermatologists from 17 January to 18 February 2020 through email lists of stakeholder professional associations and dermatologists identified by the steering committee. The survey consisted of a prespecified list of topics created by the general committee and open-ended questions to suggest other priority topics. Respondents ranked the topics in the field that were most important to address with practical guidelines. There were 99 respondents, including 80 Canadian dermatologists and 19 international dermatologists. The general committee reviewed the results of the needs assessment survey, and prioritized topics of interest based on topic frequency and discussions among all committee members. The initial needs assessment defined five priority topics to address with practical guidelines. An initial patient needs survey was conducted in English and French through the social media accounts and email newsletter of the Canadian Association of Psoriasis Patients from October 2020 to January 2021. The survey will be refined to elicit patient concerns, with an annual reassessment. Ethics committee approval was not required, per section 2.5 of the TCPS2, as physician and patient needs assessment surveys are conducted as part of a quality improvement endeavor to inform topics for future clinical guidelines.

Fig. 2.

Guidelines framework. Process for identifying clinically relevant questions and generating recommendations. *To be used as applicable, where appropriate. GRADE grading of recommendation, assessment, development, and evaluation

Clinical Questions

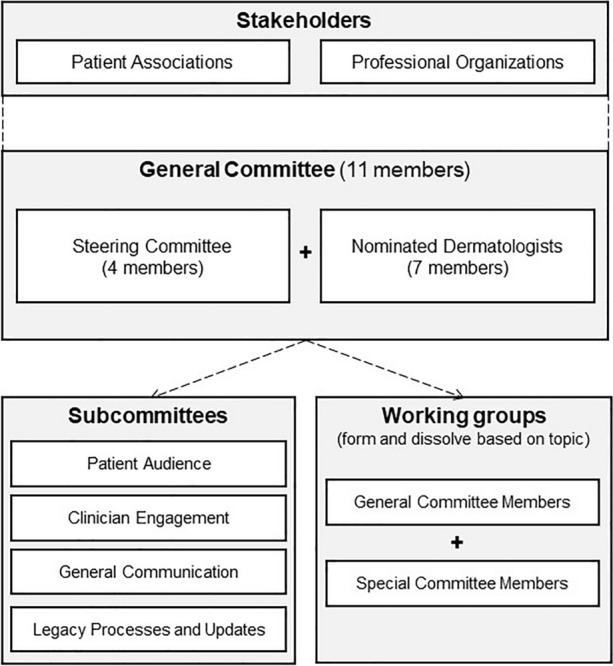

Certain questions are fundamental to diagnosing, assessing, and treating Pso in complex or multifaceted clinical situations. For each topic, clinical concerns will be identified by the working group. These clinical concerns will be broken down into clinically relevant and focused questions for which studies or observations are available. Consensus instruments such as a Delphi or modified Delphi process may be used to generate questions. Where appropriate, the PICO (Problem/Patient/Population, Intervention/Indicator, Comparison, Outcome) structure will be used. This group intends to be flexible in the tools used to draw conclusions and assess evidence. Many clinically relevant questions do not have sufficient data to confidently assess risk. An alternative to direct observation, an inferential methodology, may be implemented. Inference-based expert elicitation is a tool used in other disciplines including astrophysics, environmental modeling, and economics to make decisions where direct evidence is not available and is unlikely or impossible due to current scientific limitations [22–25], and has been implemented by our guidelines group as a proof-of-concept exercise to estimate Pso prevalence [3]. Although inferential approaches are used to make decisions in individual patient cases, our group aims to formalize an inference-based approach that can be applied in clinical scenarios where there are no clinical trials, limited real world-data, and where prospective or retrospective evidence is not possible or unlikely. Where appropriate, committee members will rely on a logical decision process: atomize the question into components that are addressed by high-grade observations (Fig. 3). Questions may be refined to align with intent and available evidence as the inference-based inquiry evolves.

Fig. 3.

Inference-based expert elicitation. Process for atomizing overarching guideline questions in a hierarchical manner into addressable subquestions for which inference-based statements are drafted and support is rated at the different levels

Reviewing Evidence and Generating Guidance Statements or Inferential Conclusions

The proposed guideline framework (Fig. 2) aims to use the best evidence available and gather expert estimates in areas with identified data gaps to inform standards of practice. Medical writers conduct scoping searches or systematic literature searches in PubMed for each clinical question depending on the nature of the question, under the direction of the guideline authors. Additional databases are considered or search terms refined as needed. Existing systematic reviews may also be consulted, where appropriate, and may be appraised using validated tools such as AMSTAR 2 [26] to assess their utility in the development of recommendations. Working group authors identify search terms and parameters, including inclusion and exclusion criteria to gather both direct and inferential evidence to answer each question. Where high-level evidence is available to answer a question, the evidence will be considered to draft recommendations for voting. Evidence and level of evidence will be ranked. Where appropriate, Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria [27] will judge certainty and strength of available evidence. The strength of the recommendation and level of agreement will be assessed using appropriate tools such as GRADE [27], Delphi [28], or quantification on a scale [22].

Where clinical trial data or other strong evidence are lacking, expert opinion may be elicited using point estimates or other tools to guide practical recommendations (Fig. 3). Guidelines should not be proscriptive as each clinical situation is unique, and it is important to consider that sometimes the best evidence available is not direct evidence. Considering the weight of available indirect evidence, authors will construct inferential statements to address the questions of interest. Evidence and level of evidence for each statement is ranked. Each statement is made more precise based upon the available evidence and intent of the statement. In place of a consensus, panel members will determine their level of confidence or level of support in each concluding statement. Level of support can be consolidated mathematically to guide the inference process, wherein support for subatomic questions is consolidated to provide support for overarching atomic and molecular level statements. Experts will complete surveys to accept or adjust any estimates that are provided as a guide.

While inferential thinking is not novel to clinical medicine, a formalized approach to inference is. This framework facilitates the aggregation of knowledge and opinions from an expert community to make decisions in the face of limited or imperfect information by making probabilistic judgments to quantify uncertainty. Data from multiple experts is aggregated, subsequently discussed, and examined with statistical models such as inferential decision models or Bayesian models after all contributors are exposed to the compiled data of their peers. For example, confidence or degree of belief for each statement is quantified by polling of clinicians on their degree of confidence in the conclusion of each atomic question and the inferences derived therefrom. Both individual responses and aggregated responses are considered. Where appropriate, a risk assessment is undertaken to estimate the probability of an adverse outcome based on the recommendation (ranked very low, low, moderate, high, or very high), or more specifically quantified as an estimated risk. Expert elicitation using the quantile method [25] may be used to numerically quantify the degrees of risk (ranked minimal, minor, moderate, significant, or severe) and to quantify risk as a probability.

Knowledge Translation and Guideline Implementation

To facilitate knowledge translation, the clinical practice guideline may be published as an accessible summary of recommendations, with an independently published comprehensive review of evidence. Implementation toolkits that incorporate patient-perspectives will be developed, under the guidance of the clinician engagement subcommittee. A summary of the recommendations for patients may be created under the guidance of the patient audience subcommittee and patient advisors.

An impact assessment may be undertaken to measure the impact of the recommendations and resulting changes in perception and practice. A survey will be administered before and after physicians review the manuscript to solicit the degree of comfort with treating a given condition or under specific clinical scenarios. Aggregate responses with distribution of comfort level will be presented to maintain anonymity. Open-ended questions may be used to identify practice-changing elements of the guidelines. A similar impact assessment may be undertaken in patient populations before and after reading the patient summary of recommendations.

Discussion

The need for clinical practice guidelines that follow a rigorous and transparent methodology, while being accessible, concise, and regularly updated is apparent [29]. This guideline development process utilizes a combination of evaluative frameworks to help guide clinical decisions in areas involving both high and low certainty evidence. Some clinical questions have sufficient evidence to formulate recommendations using frameworks such as GRADE [27]. Most clinical concerns lack sufficient evidence to develop evidence-based clinical recommendations. Yet these concerns are relevant to everyday practice. Though randomized controlled clinical trials are considered the highest level of evidence, there are areas where this level of evidence cannot be attained. An example of where evidence is scarce is in HIV patients who have Pso. These patients may present with more severe or treatment refractory cutaneous disease [30], but they are prohibited from participating in Pso clinical trials. An additional example is the exclusion of HIV-positive patients from cancer treatment trials [31, 32]. Concerns about immunosuppressive effects and subsequent complications of Pso treatments result in conservative approaches to treatment of this population [30]. Other excluded populations underrepresented or excluded from participating in clinical trials are the elderly, pregnant women, patients with multiple uncontrolled comorbidities, and those with a history of malignancy. Exclusion criteria for clinical trials result in a necessarily narrow definition of patients. Clinical trial populations are often restricted to those with a lower risk profile than might be found in a real-world population [33].

Real-world evidence may better reflect actual clinical environments and patient populations in which medical treatments are used [34]; however, this data is subject to numerous biases: prescriber bias, enrollment bias, confounder bias, survivor bias, observer bias, assessment bias, lack of precision, collection bias, enrichment bias, and absence of appropriate control populations [35]. Label restrictions may preclude patients with specific underlying conditions from enrolling in pragmatic studies [36]. In the case of uncommon conditions, many years of observations or large numbers of patients are required before the number of events in the population of interest provides sufficient power to estimate a sound statistic. When clinical trial and real-world evidence are lacking, expert elicitation based on careful review of available evidence can be used to guide practice. Constructing fundamental questions supported by direct observations or basic science permits an evidence-based approach to consolidate and circumscribe evidence, which by logical inference, directs conclusions regarding the primary clinical concern.

All approaches to knowledge synthesis have limitations, and applying inferential judgements is not an exception. Inferential judgements are, by their nature, less direct and presume the most influential elemental questions are identified and assessed. Focusing attention on several narrowly focused issues has the inherent risk of missing an important factor. Inference may rely on low-level evidence, which is mitigated by capturing the degree of certainty. Uncertainty is intrinsic to all observations and inferences whether direct or indirect. When observations are conducted in a scientific manner, clinical trials being an example, intrinsic uncertainty can be formally assessed. In most instances, quantifying uncertainty is challenging. The present approach provides a structured approach to estimating support, certainty, or confidence for inferred conclusion.

Conclusion

The present guideline development framework results in practical, informative recommendations for topics identified by physicians and patients as areas of clinical concern. Best available evidence is combined with expert opinions based on structured probabilistic judgements. By applying this method, best practices are defined for clinically complex areas where high-level evidence is lacking.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the following professional and patient organizations for their support of this guideline’s initiative: Alberta Society of Dermatologists, Atlantic Provinces Dermatology Association, Association des médecins spécialistes dermatologues du Québec, Dermatology Association of Ontario, The Dermatologic Society of Manitoba, Saskatchewan Dermatology Association, Canadian Association of Psoriasis Patients, Canadian Skin Patient Alliance.

Funding

This project was initiated and financially sponsored by the Dermatology Association of Ontario. Unrestricted educational grants have been provided by the following industry partners (listed alphabetically): AbbVie Inc., Janssen Inc., LEO Pharma Inc., and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Inc. These grants were pooled and used to pay for the journal’s Rapid Service Fee as well as medical writing assistance as outlined below.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Author contributions

KAP contributed to the concept and design, drafting, review and editing of the manuscript. JB, JPD, MJG, CHH, MGK, CWL, CM, YP and RBV contributed to the concept and design, review and editing of the manuscript.

Medical writing, editorial, and other assistance

Anna Czerwonka, H BSc, Travis Brooke-Bisschop, MSc, Robyn Leonard, BSc, and Jai Sharma, MSc of FUSE Health (Toronto, ON) provided professional medical writing services and organizational support for this manuscript. Medical writing assistance was funded by pooled unrestricted educational grants from AbbVie Inc., Janssen Inc., LEO Pharma Inc., and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Inc.

Disclosures

Kim A Papp has served as an investigator, speaker, advisor/consultant for and/or received grants/honoraria from AbbVie, Akros, Amgen, Anacor, Arcutis, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Baxalta, Baxter, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CanFite, Celgene, Coherus, Dermira, Dow Pharma, Eli Lilly, Forward Pharma, Galderma, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Kyowa Hakko Kirin, LEO Pharma, Meiji Seika Pharma, Merck (MSD), Merck-Serono, Mitsubishi Pharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi-aventis, Sanofi Genzyme, Takeda, UCB, and Valeant. Melinda J Gooderham has served as an investigator, speaker, advisor and/or consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Actelion, Akros, Arcutis, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Celgene, Coherus, Dermira, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Glenmark, GSK, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin, Leo Pharma, Medimmune, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Regeneron, Sanofi Genzyme, UCB, and Valeant. Charles W Lynde has served as an Advisory Board Member, Speaker, Consultant for and/or received honoraria or grants from, AbbVie, Amgen, Bausch Health, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, GSK, Leo Pharma, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, Valeant. Yves Poulin has received grants/honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Aquinox, Aralez, Baxalta, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Dermira, DS Biopharma, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Galderma, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen, Leo Pharma, MedImmune, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Takeda, UCB Pharma, and Valeant. Jennifer Beecker has served as an investigator, speaker, advisor/consultant for and/or received grants/honoraria from AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, Concert, Galderma, Eli Lilly, Incyte, Janssen, Johnson and Johnson, Leo Pharma, L’Oréal Group, Novartis, Sanofi Genzyme, Pfizer, and UCB. Jan P Dutz has served as an advisor/consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Bausch, Celgene, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Sanofi, has received grants and honoraria from AbbVie, Janssen, Corbis, Lilly, and has served as a speaker for Celgene, Janssen. JD is supported by a Senior Scientist Award of the BC Children’s Hospital Research Institute. Robert Gniadecki has served as an advisor/consultant for AbbVie, Bausch, Celgene, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Lilly, Novartis, Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi, and served as a speaker for Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Sanofi. Chih-ho Hong has served as an investigator, speaker, advisor and/or consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Acterlion, Akros, Arcutis, BMS, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene, Dermira, Dermavant, Eli-Lilly, Galderma, GSK, Incyte, Janssen, Leo Pharma, Medimmune, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi-Genzyme, Sun Pharma, UCB and Valeant (Bausch Health). Mark G Kirchhof has served as an advisor/consultant for AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Bausch Health, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Leo, Novartis, UCB, Sanofi Genzyme, and served as a speaker for AbbVie, Janssen, Leo, Novartis, Pfizer, UCB, Sanofi Genzyme. Catherine Maari has served as an Investigator, Advisory Board Member, Speaker, Consultant for, and/or received honoraria or grants from, AbbVie, UCB, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Leo pharma, GSK-Stiefel, Janssen, Novartis, Bausch and Pfizer. Ronald B Vender has served as an advisor/consultant and speaker, and received grants and honoraria, from AbbVie, Amgen, Bausch-Health, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB.

Compliance with ethics guidelines

Ethics committee approval was not required per section 2.5 of the TCPS2, as physician and patient needs assessment surveys are conducted as part of a quality improvement endeavor to inform topics for future clinical guidelines.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during the guidelines process will be published as supplementary information files, and any further queries may be made to the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Global report on PSORIASIS. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parisi R, Symmons DPM, Griffiths CEM, Ashcroft DM. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol Elsevier Masson SAS. 2013;133:377–385. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papp KA, Gniadecki R, Beecker J, Dutz J, Gooderham MJ, Hong CH, et al. Psoriasis prevalence and severity by expert elicitation. Dermatol Ther. 2021;11:1053–1064. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00518-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takeshita J, Grewal S, Langan SM, Mehta NN, Ogdie A, Van Voorhees AS, et al. Psoriasis and comorbid diseases: epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:377–390. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.07.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cunha JS, Qureshi AA, Reginato AM. Management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in a multidisciplinary rheumatology/dermatology clinic. Fed Pract. 2015;32:14S–20S. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim W, Jerome D, Yeung J. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis. Can Fam Physician. 2017;63:278–285. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gisondi P, Talamonti M, Chiricozzi A, Piaserico S, Amerio P, Balato A, et al. Treat-to-target approach for the management of patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: consensus recommendations. Dermatol Ther. 2021;11:235–252. doi: 10.1007/s13555-020-00475-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Papp K, Gulliver W, Lynde C, Poulin Y, Ashkenas J. Canadian guidelines for the management of plaque psoriasis: overview. J Cutan Med Surg. 2011;15:210–219. doi: 10.2310/7750.2011.10066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menter A, Strober BE, Kaplan DH, Kivelevitch D, Prater EF, Stoff B, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1029–1072. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, Gelfand JM, Lichten J, Mehta NN, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Menter A, Gelfand JM, Connor C, Armstrong AW, Cordoro KM, Davis DMR, et al. Joint American Academy of Dermatology-National Psoriasis Foundation guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis with systemic nonbiologic therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1445–1486. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elmets C, Korman N, Farley Prater E, Wong E, Rupani R, Kivelevitch D. Joint AAD-NPF Guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with topical therapy and alternative medicine modalities for psoriasis severity measures. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:432–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Psoriasis: assessment and management. Systemic therapy. 2017. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg153/chapt. [PubMed]

- 14.Smith CH, Jabbar-Lopez ZK, Yiu ZZ, Bale T, Burden AD, Coates LC, et al. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for biologic therapy for psoriasis 2017. Br J Dermatol. 2017;177:628–636. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith CH, Yiu ZZN, Bale T, Burden AD, Coates LC, Edwards W, et al. British Association of Dermatologists guidelines for biologic therapy for psoriasis 2020: a rapid update. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:628–637. doi: 10.1111/bjd.19039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gisondi P, Altomare G, Ayala F, Bardazzi F, Bianchi L, Chiricozzi A, et al. Italian guidelines on the systemic treatments of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatology Venereol. 2017;31:774–790. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Amatore F, Villani AP, Tauber M, Viguier M, Guillot B. French guidelines on the use of systemic treatments for moderate-to-severe psoriasis in adults. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:464–483. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. It’s about integrating individual clinical expertise and the best external evidence. Br Med J. 1996;312:71–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haynes B, Sackett D, Guyatt G, Tugwell P. Clinical epidemiology: how to do clinical practice research. 3. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akl EA, Meerpohl JJ, Elliott J, Kahale LA, Schünemann HJ, Agoritsas T, et al. Living systematic reviews: 4. Living guideline recommendations. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;91:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. CMAJ. 2010;182:839–842. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.090449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Expert O’Hagan A, Elicitation Knowledge. Subjective but Scientific. Am Stat. 2019;73:69–81. doi: 10.1080/00031305.2018.1518265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morgan MG. Use (and abuse) of expert elicitation in support of decision making for public policy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:7176–7184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319946111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hemming V, Burgman MA, Hanea AM, McBride MF, Wintle BC. A practical guide to structured expert elicitation using the IDEA protocol. Methods Ecol Evol. 2018;9:169–180. doi: 10.1111/2041-210X.12857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.O’Hagan A, Buck C, Daneshkhah A, Eiser J, Garthwaite P, Jenkinson D, et al. Uncertain judgements: eliciting experts’ probabilities. New York: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shea B, Reeves B, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guyatt G, Oxman A, Vist G, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Yiu Z, Jabbar-Lopez Z, Ahmed S, Mohd Mustapa M, Chi C-C, Flohr C. Results from the BJD survey on readership views towards clinical practice guidelines. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183:188–189. doi: 10.1111/bjd.18960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Menon K, Van Voorhees AS, Bebo BF, Gladman DD, Hsu S, Kalb RE, et al. Psoriasis in patients with HIV infection: from the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62:291–299. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2009.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Venturelli S, Pria AD, Stegmann K, Smith P, Bower M. The exclusion of people living with HIV (PLWH) from clinical trials in lymphoma. Br J Cancer. 2015;113:861–863. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uldrick TS, Ison G, Rudek MA, Noy A, Schwartz K, Bruinooge S, et al. Modernizing clinical trial eligibility criteria: recommendations of the American society of clinical oncology-friends of cancer research HIV working group. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3774–3780. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.7338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kennedy-Martin T, Curtis S, Faries D, Robinson S, Johnston J. A literature review on the representativeness of randomized controlled trial samples and implications for the external validity of trial results. Trials Trials. 2015;16:495. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-1023-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bartlett VL, Dhruva SS, Shah ND, Ryan P, Ross JS. Feasibility of using real-world data to replicate clinical trial evidence. JAMA Netw open. 2019;2:e1912869. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blonde L, Khunti K, Harris SB, Meizinger C, Skolnik NS. Interpretation and impact of real-world clinical data for the practicing clinician. Adv Ther. 2018;35:1763–1774. doi: 10.1007/s12325-018-0805-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leather DA, Jones R, Woodcock A, Vestbo J, Jacques L, Thomas M. Real-world data and randomised controlled trials: the Salford lung study. Adv Ther. 2020;37:977–997. doi: 10.1007/s12325-019-01192-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during the guidelines process will be published as supplementary information files, and any further queries may be made to the corresponding author on reasonable request.