Abstract

Congenital hydrocephalus is a major neurological disorder with high rates of morbidity and mortality; however, the underlying cellular and molecular mechanisms remain largely unknown. Reproducible animal models mirroring both embryonic and postnatal hydrocephalus are also limited. Here, we describe a new mouse model of congenital hydrocephalus through knockout of β-catenin in Nkx2.1-expressing regional neural progenitors. Progressive ventriculomegaly and an enlarged brain were consistently observed in knockout mice from embryonic day 12.5 through to adulthood. Transcriptome profiling revealed severe dysfunctions in progenitor maintenance in the ventricular zone and therefore in cilium biogenesis after β-catenin knockout. Histological analyses also revealed an aberrant neuronal layout in both the ventral and dorsal telencephalon in hydrocephalic mice at both embryonic and postnatal stages. Thus, knockout of β-catenin in regional neural progenitors leads to congenital hydrocephalus and provides a reproducible animal model for studying pathological changes and developing therapeutic interventions for this devastating disease.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12264-021-00763-z.

Keywords: Congenital hydrocephalus, β-Catenin, Ependymal cells, Nkx2.1, Neural development

Introduction

Congenital hydrocephalus is a pathological process involving excess cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) due to heritable gene mutations. It is one of the most common birth defects in humans, with a high incidence of 0.1% to 0.5% worldwide [1]. In newborn infants suffering from congenital hydrocephalus, characteristic symptoms include progressive head enlargement, increased intracranial pressure, progressive brain degeneration, paralysis of the limbs, and intellectual impairment; it can result in death. At present, the most frequently performed procedure for treating congenital hydrocephalus is surgical shunt placement, but this is unfortunately associated with a high failure rate and severe complications due to infection and inherent neurological deficits [2–4].

Several animal models of congenital hydrocephalus have been developed for mechanistic and therapeutic studies [5–11]. Hydrocephalic Texas (H-Tx) rats, which are generated by brother-sister mating, result in the development of spontaneous genetic mutations. However, the frequency of hydrocephalus in these rats varies between mating pairs, with an incidence of no more than 50% [12–14]. Furthermore, H-Tx rat fetuses show hydrocephalus-like dilated lateral ventricles from embryonic day (E) 18.5 to E20.5 [13], much later than the clinical detection time of congenital hydrocephalus in the middle stage of pregnancy [15, 16]. In another animal model, hydrocephalus with hop gait (hyh) mutant mouse embryos show denuded ependyma at E12.5 and agenesis of the corpus callosum and hippocampal commissure at E16.5, but do not exhibit hydrocephalus-dilated ventricles until postnatal day 1 (P1) [9, 10]. Moreover, as a spontaneous mutation, the hyh mutation without tissue specificity causes pathologies unrelated to hydrocephalus, such as severe infertility [17]. In another case, Ruvbl1 conditional knockout (cKO) mice display severe hydrocephalus after birth with concomitant acute kidney injury [18].

Our understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying congenital hydrocephalus remains limited. Clinical investigations have shown that it is associated with abnormalities in ependymal cells, a layer of ciliated epithelial cells in the ventricular zone (VZ) of the cerebral ventricles [19, 20]. Hydrocephalic fetuses at mid- or late-gestation show evident denudation of the ependyma in the aqueduct and lateral ventricles. Moreover, the denuded surface area is proportional to fetal age and hydrocephalus severity [21]. Hydrocephalus-related ependymal detachment also occurs in experimental animal models. In hyh mice, the denudation of ependymal cells is found in embryos before the onset of hydrocephalus [9]. Wnt/β-catenin signaling is activated in developing ependymal cells, and is indispensable for normal development and adult homeostasis [22, 23]. In mice, loss of function of downstream Wnt signaling machinery, such as Daple and dishevelled genes, disrupts the planar polarity of ependymal motile cilia and results in hydrocephalus three weeks after birth [24, 25].

Here, we established a new mouse model of congenital hydrocephalus by conditional deletion of β-catenin in Nkx2.1-expressing ventral neural progenitors. This reproducible congenital hydrocephalus model provides a useful tool for studying pathological changes and developing therapeutic interventions for this devastating disease.

Materials and Methods

Animals and Genotyping

The Nkx2.1-Cre, Ctnnb1fl/fl, and Rosa26-LSL-YFP mice used in this study were described previously [26–28]. E0.5 was defined as the day of sperm plug detection and P1 was defined as the day of birth. All animals were kept in a room maintained at 21°C ± 2°C and 55% ± 5% relative humidity with a 12-h light/dark cycle and free access to a standard laboratory diet and tap water. All procedures were approved by the Tongji University Animal Care Committee and complied with the fundamental guidelines for the proper conduct of animal experiments and related activities in academic research institutions under the jurisdiction of Tongji University School of Medicine. Embryos were obtained from anesthetized pregnant dams with intraperitoneal injection of avertin (400 mg/kg). Mice were genotyped by PCR using primers described previously [27–29], as follows:

| Mutants | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| Nkx2.1-Cre | CCACAGGCACCCCACAAAAATG | GCCTGGCGATCCCTGAACAT |

| Ctnnb1fl/fl or Ctnnb1fl/wt | AAGGTAGAGTGATGAAAGTTGTT | CACCATGTCCTCTGTCTATTC |

| Rosa26-LSL-YFP | AAGTTCATCTGCACCACCG | TCCTTGAAGAAGATGGTGCG |

Immunohistochemistry

Each mouse was deeply anesthetized with avertin (400 mg/kg) and perfused intracardially with 4% paraformaldehyde. The brain was removed and postfixed in the same fixative for 3 h–8 h, which was then replaced with 20% and 30% sucrose overnight. Tissues were fast-frozen in cryo-embedding compound and cut on a cryostat at 20 μm. Immunofluorescence labeling was performed by blocking the sections with 10% donkey serum in PBST (0.2% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline) for 1.5 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with primary antibodies for 36 h–48 h at 4°C. After washing, the sections were incubated with fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1,000, Jackson, West Grove, USA) overnight at 4°C. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 for 10 min at room temperature. Stained sections were washed and cover-slipped with Fluoromount-G® (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, USA). Images were captured using a Leica TSC SP8 (Leica Microsystems, Bensheim, Germany) confocal laser-scanning microscope. The antibodies used were GFP (1:1,000, rabbit IgG, Invitrogen, A-6455, Carlsbad, USA), GFP (1:1000, chicken IgY, Aves, GFP-1020, Davis, USA), β-catenin (1:500, rabbit IgG, Abcam, ab16051, Cambridge, UK), GFAP (1:500, rabbit IgG, Dako, Z0334, Santa Clara, USA), acetylated tubulin (1:500, mouse IgG, Sigma, T6793, St. Louis, USA), Ki67 (1:500, rabbit IgG, Abcam, ab15580), PH3 (1:500, rabbit IgG, CST, 53348, Danvers, USA), Dcx (1:400, goat IgG, Santa Cruz, sc-8066, Dallas, USA), Tbr1 (1:200, rabbit IgG, Abcam, ab31940), Satb2 (1:250, mouse IgG, Santa Cruz, sc-81376), Cux1 (1:250, mouse IgG, Abcam, ab54583), ChAT (1:200, goat IgG, Millipore, AB144P, Burlington, USA), SST (1:500, goat IgG, Santa Cruz, sc-7819), GABA (1:2,000, rabbit IgG, Sigma, A2052), PV (1:1,000, mouse lgG, Sigma, P3088), CR (1:1,000, mouse lgG, Swant, 6B3, Burgdorf, Switzerland), NOS (1:1,000, rabbit IgG, Millipore, AB5380) and NPY (1:200, rabbit IgG, Absci, 38619, Vancouver, USA). Antigen retrieval was performed for staining of Ki67, Tbr1, Satb2, and Cux1 with water heating of tissue sections to temperatures of nearly boiling in the presence of 0.01 mol/L sodium citrate (pH 6.0) for 30 min.

In Situ Hybridization

The probe against SST was a kind gift from Dr. Yu-Qiang Ding of Fudan University, and was cloned into the pGEM-T vector (Promega, Wisconsin, USA). For in situ hybridization, brains from E14.5 embryos were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in diethyl pyrocarbonate (DEPC)-treated water overnight and then cryoprotected with 20% and 30% sucrose in DEPC-PBS for 12–24 h. Transverse sections (20 µm) were cut on a cryostat and mounted on glass slides (Fisher Scientific, Rockford, USA). RNA probes labeled by digoxygenin-UTP (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) were produced by in vitro transcription, and hybridization signals were visualized by nitro blue tetrazolium chloride and 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (both from Fermentas, Rockford, USA) staining.

RNA Extraction, Library Preparation, and Sequencing

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol with phenol-chloroform extraction, and RNA quality was verified using a Bio-Analyzer 2100 (Agilent, Santa Clara, USA) and Qubit RNA assay kit (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, USA). Total RNA (500 ng) from each sample was used to prepare a library with the NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (E7530) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The libraries were then sequenced at 50-bp single reads on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 platform. The raw sequencing reads are available from the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE130320.

RNA-seq Data Processing and Analysis

Sequencing reads from each sample were mapped to the mouse reference genome (mm10 version) using TopHat v2.1.1. The mapped reads were further analyzed using Cufflinks v1.3.0 and the expression levels for each transcript were quantified as fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads.

For differential expression analysis, sequencing counts at the gene level were obtained using HTSeq v0.9.1. R package DESeq2 was then used to identify differentially-expressed genes (DEGs) between different conditions. To assess the significance of differential gene expression, the P-value threshold was set at 0.05 and the fold-change was set at 1.5.

Statistically enriched functional categories of genes were identified using DAVID 6.8 (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/).

Statistical Analyses

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. Unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test was used. Statistical significance was considered at P-values below 0.05: *P <0.05, **P <0.01, ***P < 0.001. In Fig. 2C and G, lateral ventricle area was calculated using ImageJ software. In Fig. 2A and E, forebrain diameter was measured using Vernier calipers.

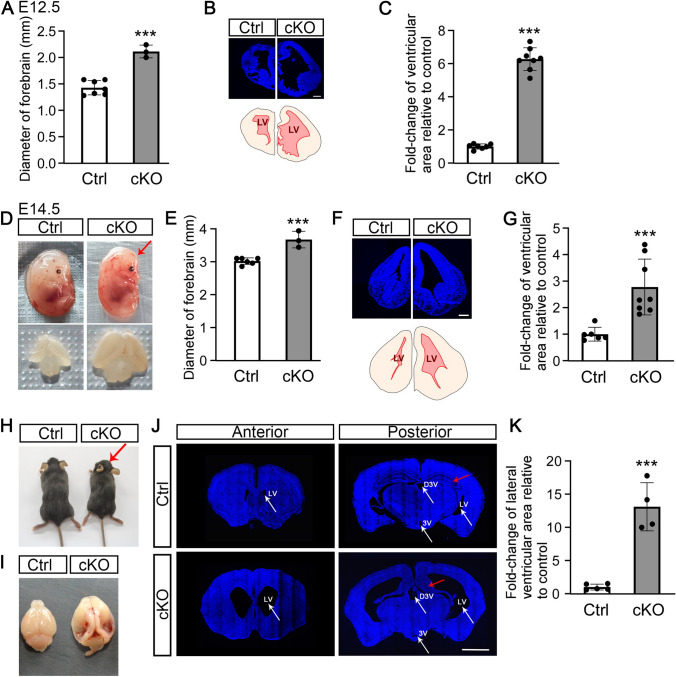

Fig. 2.

Conditional ablation of β-catenin in ventral telencephalic progenitors causes severe hydrocephalus from mid-term gestation through to adulthood. A cKO embryos at E12.5 have an enlarged brain with greater forebrain diameter (***P <0.001, unpaired t-test). B Upper panel, brain sections stained with Hoechst 33258, a nuclear marker, display a dilated ventricle in cKO mice at E12.5 (scale bar, 250 μm). Lower panel, tracing of the upper panel, showing the lateral ventricle area (LV) in red. C LV areas in control and cKO embryos at E12.5 (***P <0.001, unpaired t-test). D cKO embryo at E14.5 exhibits a domed head (upper panel; red arrow) and enlarged brain (lower panel). E cKO embryos at E14.5 have a greater forebrain diameter (***P <0.001, unpaired t-test). F Upper panel, brain sections stained with Hoechst 33258 display a dilated ventricle in cKO mice at E14.5 (scale bar, 250 μm). Lower panel, tracing of the upper panel, showing LV area in red. G LV areas in control and cKO embryos at E14.5 (***P <0.001, unpaired t-test). H, I Adult cKO mice have a smaller body and a dome-shaped head (H, red arrow), and a swollen brain (I). J, K Adult cKO mouse displaying a dilated LV (white arrows), dorsal third ventricle (D3V; white arrows), obstructed ventral third ventricle (3V; white arrows), and shrunken hippocampus (red arrows) (J) (scale bar, 2 mm) and statistics of LV area (K) (***P <0.001, unpaired t-test).

Results

Knockout of β-Catenin in Nkx2.1-expressing Neural Progenitors in the Ventral Telencephalon

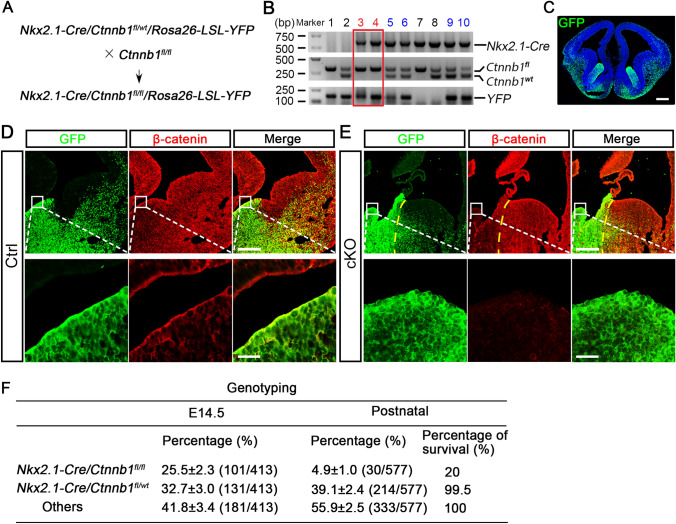

The VZ develops into ependymal cells that line the walls of the cerebral ventricles [30]. During telencephalon development, Nkx2.1 is expressed in the VZ of the ventral-most telencephalon. To study the role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling during the development of ventral neural progenitors and ependymal cells, we crossed Nkx2.1-Cre;Ctnnb1fl/wt;Rosa-26-LSL-YFP mice with Ctnnb1fl/fl mice to yield Nkx2.1-Cre;Ctnnb1fl/wt;Rosa-26-LSL-YFP control and Nkx2.1-Cre;Ctnnb1fl/fl;Rosa-26-LSL-YFP cKO mice with a lineage tracing background [27–29] (Fig. 1A, B), in which Nkx2.1-expressing progenitors and their descendant cells were traced by yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) and recognized by a green fluorescent protein (GFP) antibody (Fig. 1C). Immunostaining confirmed that in mid-gestation embryos the GFP signal was restricted to the ventral-most telencephalon, suggesting a tight expression pattern of Cre recombinase under the control of the Nkx2.1 promoter. Meanwhile, the protein level of β-catenin, encoded by gene of Ctnnb1, was significantly lower in GFP-expressing cells in cKO embryos than in control littermates (Fig. 1D, E), indicating efficient and lineage-specific β-catenin knockout. Genotyping revealed that the occurrence rates of heterozygous mice at E14.5 and P1 were 32.7% and 39.1%, respectively, which followed Mendel’s laws, while the proportion of homozygous mice was 25.5% at E14.5, but only 4.9% at P1 (Fig. 1F). These results indicate that Wnt/β-catenin signaling is required for the normal development of ventral telencephalic progenitors and β-catenin deletion in these progenitors leads to perinatal lethality.

Fig. 1.

Conditional ablation of β-catenin in ventral telencephalic progenitors. A Schematic of breeding strategy for generation of conditional β-catenin knockout (cKO) mice in a lineage-tracing background. B Genotyping results of littermate mice (red box indicates YFP-tagged homozygous mice; blue numbers indicate YFP-tagged heterozygous mice). C Representative image showing that YFP-labelled Nkx2.1-Cre-expressing cells, recognized by GFP antibody, mainly reside in the MGE and POA at E14.5 (scale bar, 250 μm). D, E Expression of β-catenin in the GFP-labeled MGE in control (Ctrl; D) and cKO (E) coronal forebrain sections at E14.5 at low (scale bar, 250 μm) and high (scale bar, 25 μm) magnification (yellow dashed lines separate MGE and LGE regions in the cKO embryo). F Genotyping results showing that the proportion of homozygous mice is significantly reduced in the postnatal stage comparing with that at E14.5, demonstrating the massive death of mutant mice after birth. About 20% of postnatal mutant mice survived to adulthood.

Conditional Ablation of β-Catenin in Ventral Telencephalic Progenitors Causes Severe Hydrocephalus from Mid-term Gestation Through to Adulthood

Strikingly, the forebrains of cKO embryos were significantly enlarged at E12.5 (Figs 2A and S1A). Histopathological examination demonstrated that cKO mice had remarkably dilated ventricles in comparison to their control siblings at E12.5 (Fig. 2B, C). At E14.5, the cKO embryos had domed heads, typical of hydrocephalus, as well as enlarged brains and dilated cerebral ventricles (Figs. 2D–G and S1B). Notably, under meticulous care and removal of competitor siblings with unrelated genotypes, approximately 20% of cKO mice survived to adulthood (Fig. 1F). The adult cKO mice had a smaller body size than control mice, but with an obvious dome-shaped head and enlarged brain (Fig. 2H, I). Severe dilation of the lateral and dorsal third ventricles as well as a reduced hippocampus were evident in cKO mice (Fig. 2J). Remarkably, the lateral ventricles in the cKO mice were dilated >10-fold compared with those in the control mice (Fig. 2K).

Together, these results demonstrate that β-catenin deletions in ventral telencephalic neural progenitors lead to progressive and persistent congenital hydrocephalus starting from mid-term gestation. The Nkx2.1-Cre;Ctnnb1fl/fl;Rosa26-LSL-YFP cKO mice can therefore serve as a reliable mouse model for studying hydrocephalus at both embryonic and postnatal stages.

Abnormal Development of the Medial Ganglionic Eminence (MGE) in Congenital Hydrocephalic Mice

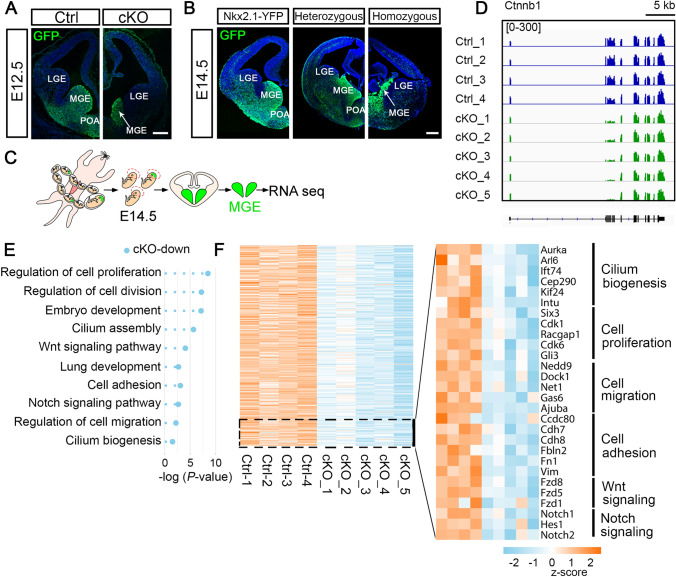

Nkx2.1 was expressed in developing ventral telencephalic progenitors in the MGE and preoptic area (POA) (Fig. 3A, B). At E12.5 and E14.5, the YFP-expressing MGE was markedly deformed in cKO embryos compared with their control littermates (Fig. 3A, B), consistent with previous research [31]. This suggests that the hydrocephalus phenotype arises from the abnormal development of MGE progenitors. To characterize the molecular features, we microdissected the MGE from E14.5 control and cKO embryos and profiled their transcriptomes through RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Abnormal development of the MGE in congenital hydrocephalic mice. A Representative images showing that the YFP reporter, which marks ventral telencephalon progenitors, is strengthened and visualized by GFP staining. At E12.5, the MGE from a cKO embryo shows remarkable shrinkage (white arrow) compared to that of control (scale bar, 250 μm). B Sections through the MGE from an Nkx2.1-Cre;Rosa26-LSL-YFP (Nkx2.1-YFP) tracing embryo and a heterozygous control embryo show no difference, while the MGE from a homozygous cKO embryo shows prominent shrinkage (white arrow) in coronal sections at E14.5 (scale bar, 250 μm). C MGE tissue microdissected from control and cKO embryos at E14.5 is subjected to RNA-seq. D Confirmation of the deletion of exons 2–6 of Ctnnb1 in cKO-MGE by visualization analysis. Controls 1–3 are Nkx2.1-YFP mice and control 4 is a heterozygous mouse. Both genotypes show similar gene expression profiles. Scale bar, 5 kb. E GO analyses of DEGs show that the functional annotations of down-regulated genes associated with cKO are highly enriched in cell proliferation, cell migration, embryonic development, cilium biogenesis, and Wnt and Notch signaling. F Heat maps of expression levels of DEGs in control and cKO embryos. Representative genes from GO term-enriched biological functions are listed on the right.

Visualization analysis confirmed that reads covering exons 2–6 of Ctnnb1 were significantly fewer in cKO embryos than in other exons and control mice (Fig. 3D), confirming the knockout efficacy. Principal component analysis of the DEGs clustered the cKO and control groups (Fig. S2A). We retrieved a total of 1,366 DEGs specifically up-regulated and 1,123 that were down-regulated in cKO mice (Fig. S2B). Of note, the cKO-associated down-regulated genes were highly enriched in the Wnt and Notch signaling pathways, cell proliferation, and embryonic development (Fig. 3E, F).

Cell-cell Adhesion and Cilium-development Events are Impaired in Congenital Hydrocephalic Mice

Zechel et al. topographically mapped hallmark gene expression in the mouse MGE and grouped genes specifically expressed in the VZ, as well as the subventricular (SVZ) and mantle zones (MZ), regions adjacent to the VZ [32]. VZ genes are primarily associated with proliferation, DNA packing and replication, and cell-cycle regulation, while SVZ genes are enriched in interneuron differentiation, cell morphogenesis, and forebrain development, suggesting that this cluster contains interneuron precursors that are gradually differentiating into postmitotic neurons. The most mature neurons reside in the MZ, resulting in their characterization as related to neuronal differentiation, migration, and projection [32].

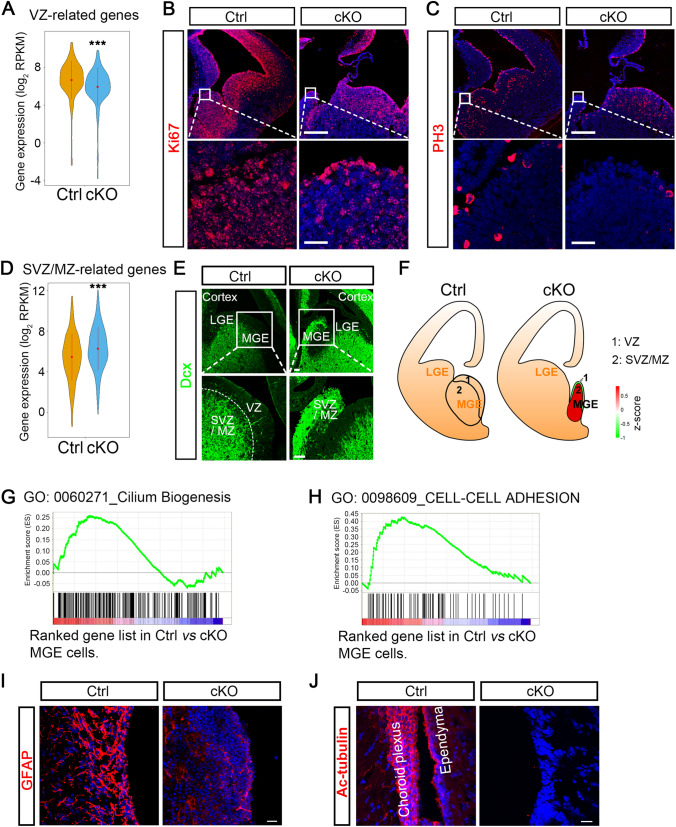

We found that VZ-associated genes were significantly down-regulated in the MGE of cKO embryos (Fig. 4A). Ki67-labeled cells remain in the cell cycle, while phospho-histone 3 (PH3)-labeled cells are in a mitotic state. Both Ki67- and PH3-labeling assays showed that there were significantly fewer cKO-MGE cells that were proliferating or dividing at E14.5 (Fig. 4B, C). These results were further supported by similar cKO embryos with reduced numbers of proliferating cell nuclear antigen-labeled and Ki67-labeled cells in the MGE with β-catenin knockout [31]. Moreover, the report that knockout of β-catenin in Nkx2.1-expressing MGE-like cells in vitro differentiated from human embryonic stem cells significantly impairs progenitor cell proliferation is also consistent with our results [33]. On the other hand, SVZ- and MZ-associated genes were substantially up-regulated in the cKO MGE (Fig. 4D). We further evaluated coronal forebrain sections at E14.5 for doublecortin (Dcx), a marker of neuroblasts and immature neurons located in the SVZ and MZ. As expected, Dcx was expressed in the SVZ and MZ, but not in the VZ in the ventral telencephalic region of control embryos. In cKO mice, however, the entire MGE was strongly labeled with Dcx, and the VZ area could not be distinguished (Fig. 4E). Based on our RNA-seq data, we proposed a topographical map of the MGE, which showed that ablation of β-catenin in the MGE leads to advanced neuronal differentiation and cell-cycle exit (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

Cell-cell adhesion and cilium-development events are impaired in congenital hydrocephalic mice. A Gene profiles specifically expressed in the VZ of the mouse MGE reported in Zechel et al. VZ-related hallmark genes are significantly down-regulated in our profiling data from cKO cells (***P <0.001, unpaired t-test). B, C Immunofluorescence staining for proliferation with Ki67 (B) and PH3 (C) in coronal forebrain sections from E14.5 embryos shows a significantly decreased population of proliferative cells in cKO mice (scale bars, 250 μm for low magnification; 25 μm for high magnification). D Gene profiles specifically expressed in the SVZ and MZ of the mouse MGE from Zechel et al. SVZ- and MZ-related genes are significantly up-regulated in cKO-MGE at E14.5 (***P <0.001, unpaired t-test). E Representative images of Dcx immunostaining in ventral regions from E14.5 embryos of control and cKO mice. Dcx-expressing neuroblasts or newborn neurons are located in the SVZ and MZ but not the VZ in control embryos, whereas they populate the entire MGE (SVZ and MZ) in cKO embryos. White boxes outline the regions shown below at higher magnification. The white dotted line separates VZ and SVZ/MZ regions. Scale bars, 50 μm. F Topographical maps of the MGE in control and cKO embryos. G, H Gene set enrichment analyses showing the enrichment of cilium biogenesis (G) and cell-cell adhesion (H) functional modules in genes enriched in control compared with cKO progenitors. I Immunostaining of the LV wall with GFAP, a marker of ependymal cells, showing a remarkable reduction of ependymal cells in newborn cKO mice at P1 (scale bar, 20 μm). J Lateral ventricle wall in adult brain sections stained with antibody against acetylated tubulin (Ac-Tub), a marker of cilia. Ac-Tub expression is missing from the cells lining the LV in cKO mice (scale bar, 20 μm).

The above results indicated that β-catenin deletion in MGE progenitors results in abnormal MGE development. Gene Ontology (GO) analyses and related hierarchical clustering heatmaps revealed that cell-cell adhesion genes and cilium generation-associated genes were significantly down-regulated in cKO mice (Fig. 3E, F). Gene set enrichment analysis also confirmed that cell-cell adhesion and cilium biogenesis-related pathways were remarkably de-enriched in the MGE of cKO embryos (Fig. 4G, H). These findings were further supported by the fact that GFAP-labeled ependymal cells lining the lateral ventricles were reduced in newborn cKO mice at P1 (Fig. 4I). Meanwhile, acetylated tubulin (Ac-Tub)-labeled cilia were almost absent from cKO mice (Fig. 4J). Together, cell-cell adhesion and cilium-development events were severely impaired in cKO mice through mid-gestation, which may contribute to the development of congenital hydrocephalus in this mutant.

Of note, the hypothalamic ventral third ventricle appeared to be obstructed in cKO mice (Fig. 2J), indicating that the aqueduct was blocked. Nkx2.1 was also expressed in the developing hypothalamus. However, different from its role in the developing MGE, knockout of β-catenin led to more hypothalamic progenitors remaining in the cell cycle as shown by more Ki67-expressing cells surrounding the third ventricle in cKO embryos at E14.5 (Fig. S3A), indicating the over-proliferation of hypothalamic progenitors. Our finding is supported by another study showing that Wnt/β-catenin pathway activity inhibits the proliferation and self-renewal of radial glial progenitor cells in the hypothalamus [34]. These data suggest that the obstructed third ventricle in cKO mice might result from the over-proliferation of hypothalamic progenitors and might be another pathological change causing hydrocephalus.

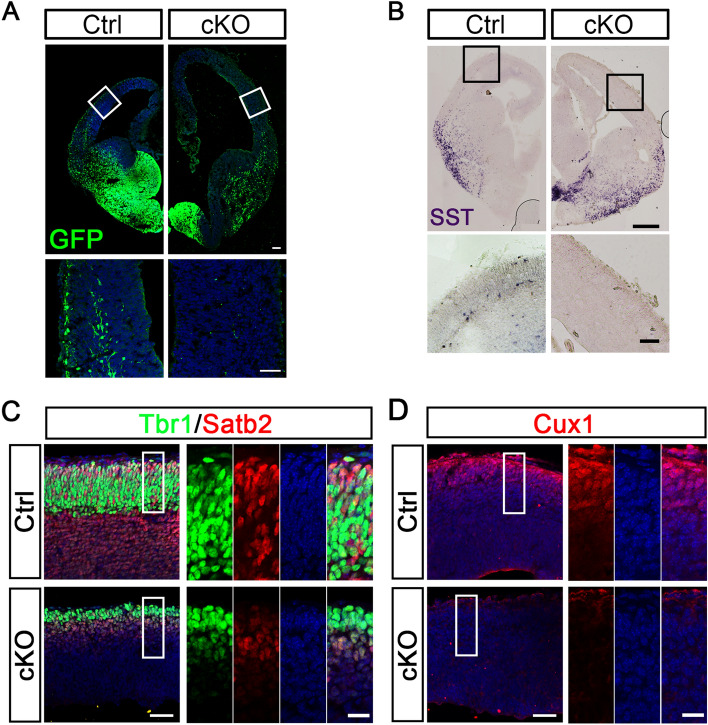

Congenital Hydrocephalic Mice Exhibit Abnormal Neuronal Development

In E14.5 control embryos, YFP-expressing interneurons (INs) generated from the ventral telencephalon actively migrated to the cortex, forming superficial and deep migratory streams (Fig. 5A). However, these streams were completely absent from cKO embryos (Fig. 5A). In situ hybridization also revealed that somatostatin (SST)-positive INs normally migrated to the cortex in control embryos, but were almost absent from the cortex of cKO embryos (Fig. 5B). Notably, although many SST-positive INs were generated in cKO embryos, they were trapped at the ventral–dorsal boundary (Fig. 5B), suggesting that severe neuronal migration defects occur in hydrocephalic mice during embryonic development.

Fig. 5.

Congenital hydrocephalic mice exhibit abnormal neural development. A GFP staining of coronal sections from E14.5 control and cKO mice. GFP-labeled INs migrate tangentially into the cortex and form superficial and deep migratory streams in control embryos, whereas these streams are completely missing from cKO embryos. Boxes outline the regions shown below at higher magnification (scale bars, 100 μm for lower magnification; 50 μm for higher magnification). B Representative images showing in situ hybridization of SST mRNA expression in coronal sections from control and cKO at E14.5. Compared with controls, more SST-positive INs are generated in cKO embryos, but they are trapped at the ventral-dorsal boundary. Boxes indicate the regions shown below at higher magnification. SST-expressing cells normally migrate to the cortex in control embryos, but are almost absent from the cortex of cKO embryos (scale bars, 250 μm for lower magnification; 50 μm for higher magnification). C, D Tbr1, Satb2 (C), and Cux1 (D) immunostaining in the cortex of E14.5 embryos of control and cKO mice (scale bars, 50 μm for lower magnification; 20 μm for higher magnification).

In the cortex of control embryos, the transcription factors Tbr1, Satb2, and Cux1, which are mainly expressed in postmitotic projection neurons in layers V–VI, II–IV, and II–III, respectively [35, 36], were found in the outer layer of the cortical plate (Fig. 5C, D). However, the number of these cortical neurons was markedly decreased in cKO embryos (Fig. 5C, D). These findings suggest that cortical neurogenesis is impaired in congenital hydrocephalic mice

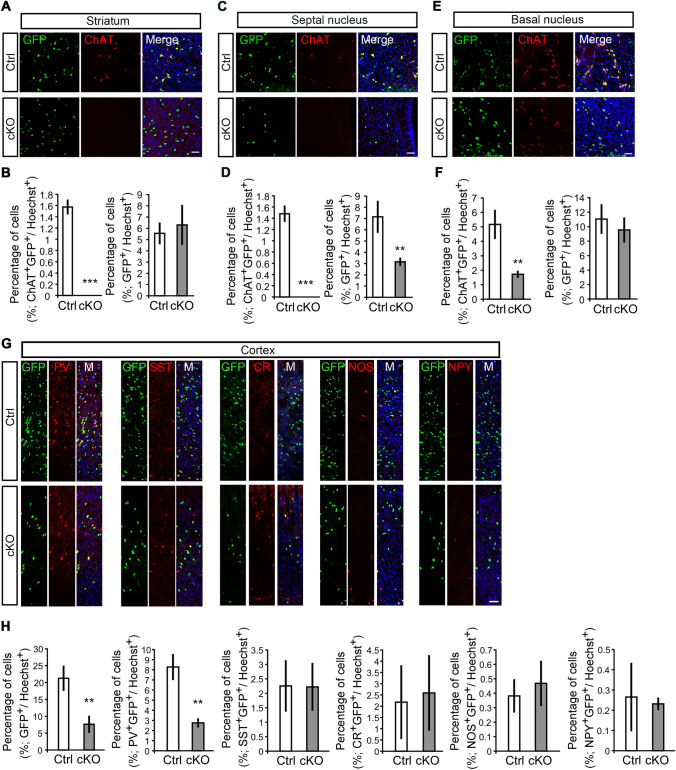

Hydrocephalic Mice Show Abnormal Neuronal Architecture at Adult Stage

In embryonic development, the MGE is a major origin of choline acetyltransferase (ChAT)-labelled ventral forebrain cholinergic neurons [37, 38]. Besides, the MGE generates >70% of forebrain GABA (γ-aminobutyric acid)-ergic INs. Based on distinct biochemical constituents and synaptic connectivity, MGE-derived GABA INs include diverse subtypes, which are characterized by parvalbumin (PV) and somatostatin (SST) neurons, as well as a small population labeled with calretinin, nitric oxide synthase, or neuropeptide Y [39]. MGE-generated ChAT neurons and INs migrate tangentially to populate other telencephalic regions, such as the striatum, septum, cortex, and hippocampus, playing important roles in building neural circuits with excitatory neurons [37, 39, 40].

To study the long-term effects of hydrocephalus in adult mice, we investigated the neuronal architecture in both the dorsal and ventral telencephalon. In control mice, ventral progenitor-derived ChAT neurons mainly resided in the striatum, septal area, and basal nucleus (Fig. 6A–F). In adult cKO mice, however, YFP-marked ChAT neurons were completely missing in the striatum and septal area, and dramatically reduced in the basal nucleus (Fig. 6A–F). On the other hand, of note, the YFP-labelled GABA INs were decreased markedly in adult cKO mice (Fig. 6G, H). Among all subtypes, PV neurons showed the most prominent defects in the cortex of cKO mice (Fig. 6G, H). These data indicate that congenital hydrocephalus mediated by β-catenin deletion results in irreparable neuronal migration defects in at least some types of neurons.

Fig. 6.

Hydrocephalic β-catenin mutant mice show abnormal neuronal architecture in adulthood. A–F Coronal sections and percentages of cells in adult control and cKO mice immunolabeled with GFP and ChAT antibodies. ChAT+GFP+ neurons are completely missing from the striatum (A and B) and septal nucleus (C and D) of cKO mice, and remarkably decreased in the basal nucleus (E and F). The percentages of GFP+ cells are also significantly reduced in the septal nucleus (C and D) of cKO mice (scale bars, 50 μm; n = 142–690 cells in at least three independent experiments; **P <0.01, ***P <0.001, unpaired t-test). G, H The numbers of GFP+ and PV+GFP+ INs are remarkably lower in the cortex of adult cKO mice than in littermate controls. No significant differences in SST+GFP+, CR+GFP+, NOS+GFP+, and NPY+GFP+ INs in the cortex of adult cKO mice compared to those in controls (scale bar, 50 μm; n = 31–843 cells in at least three independent experiments; **P <0.01, unpaired t-test).

Congenital Hydrocephalic Mice Show Impaired Motor Function, Anxiety-like Behavior, and Learning–memory Deficits

To further study the pathological phenotypes of the β-catenin mutants, we performed behavioral tests in control and cKO mice. The rotating rod test showed that retention times on the rotating Plexiglas rod differed for adult control and cKO mice (Fig. S4A), suggesting impaired motor ability in the latter. In the open field test, time traveled in the center was significantly reduced in cKO mice (Fig. S4B), revealing anxiety-like behavior [41]. In the fear conditioning and Morris water maze tests, both fear and spatial memory were remarkably impaired in cKO mice (Fig. S4C–G). The impaired behavioral profiles of cKO mice coincided with typical symptoms of hydrocephalus [42] that may result from developmental and irreversible defects in the nervous system.

Discussion

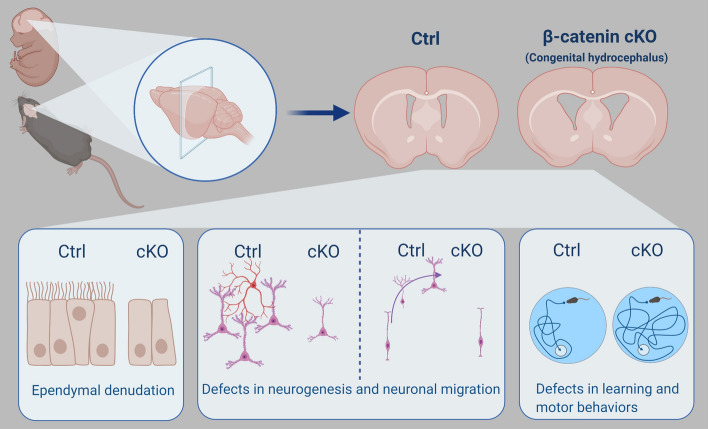

Here, we established a stable mouse model of congenital hydrocephalus based on β-catenin deletion in Nkx2.1-expressing ventral neural progenitors. These mice consistently showed enlarged brains and ventriculomegaly starting from E12.5 and maintained disease phenotypes throughout adulthood. This reproducible animal model exhibits the earliest onset of disease pathology and is suitable for studying transient or long-lasting neuropathological changes under high mechanical pressure in both the embryonic and adulthood stages (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Schematic of regional β-catenin deletion-induced long-lasting congenital hydrocephalus. In this study, we generated a new mouse model of congenital hydrocephalus through knockout of β-catenin in Nkx2.1-expressing regional neural progenitors. Progressive ventriculomegaly and an enlarged brain were consistently observed in knockout mice from E12.5 through to adulthood. Meanwhile, severe dysfunctions of ependymal cells and cilium biogenesis were found within the ventricular zone after β-catenin knockout. The hydrocephalic mice showed aberrant neurogenesis and neuronal migration in both the ventral and dorsal telencephalon. Typical defects in motor and learning behaviors were also found in the mutants. The image was generated using BioRender.

Nkx2.1 is a key transcription factor important for ventral telencephalic neural progenitor development and is strongly expressed in neuroepithelial cells located in the regional VZ [30, 43], from which ependymal cells lining the cerebral ventricles are derived [30]. Wnt/β-catenin signaling is a key regulator of ependymal cell development [22, 23]. Here, whole-genome RNA-seq revealed that conditional knockout of β-catenin in Nkx2.1-expressing progenitors led to a remarkable down-regulation of VZ-featured genes at E14.5, suggesting aberrant development of ventral telencephalic neural progenitors or denudation of the VZ as well as ependymal cells. This was further supported by immunostaining studies, which showed that Ki67- and PH3-positive proliferative VZ progenitors were dramatically reduced in β-catenin cKO embryos. Similar impaired progenitor cell proliferation has also been found in β-catenin mutant MGE cells in both in vitro and in vivo experiments [31, 33]. Moreover, SVZ/MZ-related genes were increased in the mutant MGE at E14.5, and this was validated by the fact that Dcx-labelled neuroblasts rather than neuroepithelial or ependymal cells lined the wall of the ventral lateral ventricle in mutant mice. These results implied that conditional β-catenin deletion causes abnormal MGE development with advanced neuronal differentiation and cell-cycle exit.

In our profiling data, mutant embryos at E14.5 showed significant down-regulation of genes essential for cilium biogenesis. Indeed, GFAP-labelled ependymal cells were largely impaired in β-catenin cKO newborn mice, and Ac-Tub-marked cilia in the ependymal cells were absent from the walls of the lateral ventricles of mutant mice. Since the ciliated ependymal cells exhibit coordinated beating to direct the flow of CSF, ciliary dysfunction as a consequence of abnormalities in the ependymal cell is frequently associated with blockage of CSF flow, which would further induce the abnormal accumulation of CSF and subsequent ventriculomegaly and enlarged brain, characteristic of hydrocephalus [44]. We therefore hypothesize that β-catenin deletion in Nkx2.1-expressing neural progenitors result in progenitor developmental defects, i.e., VZ denudation and dysfunction of cilium biogenesis in ependymal cells, which, in turn, lead to congenital hydrocephalus. Our study also revealed that dysfunction in the ventral VZ–ependymal cell–cilium biogenesis stream is sufficient to induce severe congenital hydrocephalus. It will be interesting to study whether knockout of β-catenin in other regional progenitors can also lead to hydrocephalus.

We also found over-proliferation of hypothalamic progenitors and stenosis of the hypothalamic ventral third ventricle in mutant mice, which is line with a previous study showing that Wnt/β-catenin pathway activity inhibits radial glial progenitor cell proliferation and self-renewal in the hypothalamus [34]. There is evidence that ependymal denudation and disruption result in the loss of adjacent neural stem cells residing in local VZ regions of the lateral ventricles, which further inhibits differentiation of the subcommissural organ (SCO) from neural stem cells [45]. Absence of the SCO can cause aqueduct obliteration [46]. Given that aqueduct obliteration is a main trigger of congenital hydrocephalus [47], it is reasonable to hypothesize that β-catenin deletion in ventral progenitors destroys ependymal cells and adjacent neural stem cells, which impairs the development of the SCO and induces aqueduct obliteration through aberrations of the SCO and further aggravates congenital hydrocephalus.

Ventriculomegaly creates potentially harmful pressure on surrounding tissues and causes irreversible neural developmental damage. Here, mutant mice exhibited severe motor and learning skill defects, consistent with other animal models of hydrocephalus and with clinical observations [42]. ChAT neurons develop from Nkx2.1-expressing ventral telencephalic progenitors, which were completely absent from the striatum and septal area in the mutants. Although we could not tell whether the dysfunction of ChAT neurons arose directly from the ventral telencephalic progenitors themselves or indirectly from harmful mechanical pressure, we found consistent malformations of cellular architecture in the cortex of mutant mice. At mid-gestation, the two migratory streams of INs were completely absent; while many INs were generated normally, they were trapped in the ventral region. Furthermore, neurogenesis in the cortex was substantially hindered in mutants. In adults, the PV INs were markedly decreased in the cortex of mutant mice. These data indicated that congenital hydrocephalus-generated ventriculomegaly causes aberrant mechanical pressure on surrounding cortex, which results in irreversible cortical neuronal developmental defects. This process may account for the behavioral and neurological dysfunctions in this disease.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFA0108000 and 2019YFA0110300), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (8205020, 32000689, 31400934, 31771132, 31872760, 31801204, and 31800858), the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (19JC1415100 and 21140902300), the Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (C120114), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2017M621526), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and the Major Program of Development Fund for Shanghai Zhangjiang National Innovation Demonstration Zone (Stem Cell Strategic Biobank and Clinical Translation Platform of Stem Cell Technology, ZJ2018-ZD-004).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Xiaoqing Zhang, Email: xqzhang@tongji.edu.cn.

Xiaocui Li, Email: sisi1113@163.com.

Ling Liu, Email: lliu@tongji.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Walsh S, Donnan J, Morrissey A, Sikora L, Bowen S, Collins K, et al. A systematic review of the risks factors associated with the onset and natural progression of hydrocephalus. Neurotoxicology. 2017;61:33–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arslan M, Aycan A, Gulsen I, Akyol ME, Kuyumcu F. Relationship between hydrocephalus etiology and ventriculoperitoneal shunt infection in children and review of literature. JPMA J Pak Med Assoc. 2018;68:38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kahle KT, Kulkarni AV, Limbrick DD, Warf BC. Hydrocephalus in children. Lancet. 2016;387:788–799. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60694-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huo J, Qi Z, Chen S, Wang Q, Wu X, Zang D, et al. Neuroimage-based consciousness evaluation of patients with secondary doubtful hydrocephalus before and after lumbar drainage. Neurosci Bull. 2020;36:985–996. doi: 10.1007/s12264-020-00542-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davy BE, Robinson ML. Congenital hydrocephalus in hy3 mice is caused by a frameshift mutation in Hydin, a large novel gene. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:1163–1170. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Feldner A, Adam MG, Tetzlaff F, Moll I, Komljenovic D, Sahm F, et al. Loss of Mpdz impairs ependymal cell integrity leading to perinatal-onset hydrocephalus in mice. EMBO Mol Med. 2017;9:890–905. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galbreath E, Kim SJ, Park K, Brenner M, Messing A. Overexpression of TGF-beta 1 in the central nervous system of transgenic mice results in hydrocephalus. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1995;54:339–349. doi: 10.1097/00005072-199505000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ibañez-Tallon I, Gorokhova S, Heintz N. Loss of function of axonemal dynein Mdnah5 causes primary ciliary dyskinesia and hydrocephalus. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:715–721. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.6.715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiménez AJ, Tomé M, Páez P, Wagner C, Rodríguez S, Fernández-Llebrez P, et al. A programmed ependymal denudation precedes congenital hydrocephalus in the hyh mutant mouse. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:1105–1119. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.11.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Páez P, Bátiz LF, Roales-Buján R, Rodríguez-Pérez LM, Rodríguez S, Jiménez AJ, et al. Patterned neuropathologic events occurring in hyh congenital hydrocephalic mutant mice. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2007;66:1082–1092. doi: 10.1097/nen.0b013e31815c1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sapiro R, Kostetskii I, Olds-Clarke P, Gerton GL, Radice GL, Strauss JF., III Male infertility, impaired sperm motility, and hydrocephalus in mice deficient in sperm-associated antigen 6. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6298–6305. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.17.6298-6305.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boillat CA, Jones HC, Kaiser GL. Aqueduct Stenosis in hydrocephalus: Ultrastructural investigation in neonatal H-Tx rat brain. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1999;9:44–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones HC, Bucknall RM. Inherited prenatal hydrocephalus in the H-Tx rat: A morphological study. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1988;14:263–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1988.tb00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones HC, Lopman BA, Jones TW, Carter BJ, Depelteau JS, Morel L. The expression of inherited hydrocephalus in H-Tx rats. Child's Nerv Syst. 2000;16:578–584. doi: 10.1007/s003810000330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leliefeld PH, Gooskens RHJM, Tulleken CAF, Regli L, Uiterwaal CSPM, Han KS, et al. Noninvasive detection of the distinction between progressive and compensated hydrocephalus in infants: Is it possible? J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2010;5:562–568. doi: 10.3171/2010.2.PEDS09309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moritake K, Nagai H, Nagasako N, Yamasaki M, Oi S, Hata T. Diagnosis of congenital hydrocephalus and delivery of its patients in Japan. Brain Dev. 2008;30:381–386. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bátiz LF, De Blas GA, Michaut MA, Ramírez AR, Rodríguez F, Ratto MH, et al. Sperm from hyh mice carrying a point mutation in alphaSNAP have a defect in acrosome reaction. PLoS One 2009, 4: e4963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Dafinger C, Rinschen MM, Borgal L, Ehrenberg C, Basten SG, Franke M, et al. Targeted deletion of the AAA-ATPase Ruvbl1 in mice disrupts ciliary integrity and causes renal disease and hydrocephalus. Exp Mol Med. 2018;50:1–17. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0108-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Wit OA, den Dunnen WF, Sollie KM, Muñoz RI, Meiners LC, Brouwer OF, et al. Pathogenesis of cerebral malformations in human fetuses with meningomyelocele. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 2008;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1743-8454-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sival DA, Guerra M, den Dunnen WF, Bátiz LF, Alvial G, Castañeyra-Perdomo A, et al. Neuroependymal denudation is in progress in full-term human foetal spina bifida aperta. Brain Pathol. 2011;21:163–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Domínguez-Pinos MD, Páez P, Jiménez AJ, Weil B, Arráez MA, Pérez-Fígares JM, et al. Ependymal denudation and alterations of the subventricular zone occur in human fetuses with a moderate communicating hydrocephalus. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2005;64:595–604. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000171648.86718.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shinozuka T, Takada R, Yoshida S, Yonemura S, Takada S. Wnt produced by stretched roof-plate cells is required for the promotion of cell proliferation around the central canal of the spinal cord. Development 2019, 146. doi:10.1242/dev.159343. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Xing L, Anbarchian T, Tsai JM, Plant GW, Nusse R. Wnt/β-catenin signaling regulates ependymal cell development and adult homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115:E5954–E5962. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1803297115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Takagishi M, Sawada M, Ohata S, Asai NY, Enomoto A, Takahashi K, et al. Daple coordinates planar polarized microtubule dynamics in ependymal cells and contributes to hydrocephalus. Cell Rep. 2017;20:960–972. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohata S, Nakatani J, Herranz-Pérez V, Cheng J, Belinson H, Inubushi T, et al. Loss of Dishevelleds disrupts planar polarity in ependymal motile Cilia and results in hydrocephalus. Neuron. 2014;83:558–571. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cai YQ, Zhang QQ, Wang CM, Zhang Y, Ma T, Zhou X, et al. Nuclear receptor COUP-TFII-expressing neocortical interneurons are derived from the medial and lateral/caudal ganglionic eminence and define specific subsets of mature interneurons. J Comp Neurol. 2013;521:479–497. doi: 10.1002/cne.23186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu Q, Tam M, Anderson SA. Fate mapping Nkx2.1-lineage cells in the mouse telencephalon. J Comp Neurol 2008, 506: 16–29. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Srinivas S, Watanabe T, Lin CS, William CM, Tanabe Y, Jessell TM, et al. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brault V, Moore R, Kutsch S, Ishibashi M, Rowitch DH, McMahon AP, et al. Inactivation of the (β)-catenin gene by Wnt1-Cre-mediated deletion results in dramatic brain malformation and failure of craniofacial development. Development. 2001;128:1253–1264. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.8.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delgado RN, Lim DA. Embryonic Nkx2.1-expressing neural precursor cells contribute to the regional heterogeneity of adult V-SVZ neural stem cells. Dev Biol 2015, 407: 265–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Gulacsi AA, Anderson SA. Beta-catenin-mediated Wnt signaling regulates neurogenesis in the ventral telencephalon. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1383–1391. doi: 10.1038/nn.2226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zechel S, Zajac P, Lönnerberg P, Ibáñez CF, Linnarsson S. Topographical transcriptome mapping of the mouse medial ganglionic eminence by spatially resolved RNA-seq. Genome Biol. 2014;15:486. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0486-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ma L, Wang Y, Hui Y, Du Y, Chen Z, Feng H, et al. WNT/NOTCH pathway is essential for the maintenance and expansion of human MGE progenitors. Stem Cell Reports. 2019;12:934–949. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duncan RN, Xie Y, McPherson AD, Taibi AV, Bonkowsky JL, Douglass AD, et al. Hypothalamic radial Glia function as self-renewing neural progenitors in the absence of Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Development. 2016;143:45–53. doi: 10.1242/dev.126813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saito T, Hanai S, Takashima S, Nakagawa E, Okazaki S, Inoue T, et al. Neocortical layer formation of human developing brains and lissencephalies: Consideration of layer-specific marker expression. Cereb Cortex. 2011;21:588–596. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhq125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cubelos Beatriz, Briz Carlos G., Maria EstebanOrtega Gemma, Nieto Marta. Cux1 and Cux2 selectively target basal and apical dendritic compartments of layer II-III cortical neurons. Dev Neurobiol 2015, 75: 163–172. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Wang CM, You Y, Qi DS, Zhou X, Wang L, Wei S, et al. Human and monkey striatal interneurons are derived from the medial ganglionic eminence but not from the adult subventricular zone. J Neurosci. 2014;34:10906–10923. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1758-14.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fragkouli A, van Wijk NV, Lopes R, Kessaris N, Pachnis V. LIM homeodomain transcription factor-dependent specification of bipotential MGE progenitors into cholinergic and GABAergic striatal interneurons. Development. 2009;136:3841–3851. doi: 10.1242/dev.038083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kepecs A, Fishell G. Interneuron cell types are fit to function. Nature. 2014;505:318–326. doi: 10.1038/nature12983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marín O. Cellular and molecular mechanisms controlling the migration of neocortical interneurons. Eur J Neurosci. 2013;38:2019–2029. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cuesta S, Funes A, Pacchioni AM. Social isolation in male rats during adolescence inhibits the wnt/β-catenin pathway in the prefrontal cortex and enhances anxiety and cocaine-induced plasticity in adulthood. Neurosci Bull. 2020;36:611–624. doi: 10.1007/s12264-020-00466-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng H, Yu WM, Waclaw RR, Kontaridis MI, Neel BG, Qu CK. Gain-of-function mutations in the gene encoding the tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 induce hydrocephalus in a catalytically dependent manner. Sci Signal 2018, 11: eaao1591. doi:10.1126/scisignal.aao1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Chi L, Fan B, Feng D, Chen Z, Liu Z, Hui Y, et al. The dorsoventral patterning of human forebrain follows an activation/transformation model. Cereb Cortex. 2017;27:2941–2954. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Treat AC, Wheeler DS, Stolz DB, Tsang M, Friedman PA, Romero G. The PDZ protein Na+/H+ exchanger regulatory factor-1 (NHERF1) regulates planar cell polarity and motile Cilia organization. PLoS One 2016, 11: e0153144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.McAllister JP. Pathophysiology of congenital and neonatal hydrocephalus. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;17:285–294. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vio K, Rodríguez S, Yulis CR, Oliver C, Rodríguez EM. The subcommissural organ of the rat secretes Reissner's fiber glycoproteins and CSF-soluble proteins reaching the internal and external CSF compartments. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 2008;5:3. doi: 10.1186/1743-8454-5-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodríguez EM, Guerra MM. Neural stem cells and fetal-onset hydrocephalus. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2017;52:446–461. doi: 10.1159/000453074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.