Abstract

Objective

(1) To derive reference values for the Shock Index (heart rate/systolic blood pressure) based on a large emergency department (ED) population of febrile children and (2) to determine the diagnostic value of the Shock Index for serious illness in febrile children.

Design/setting

Observational study in 11 European EDs (2017–2018).

Patients

Febrile children with measured blood pressure.

Main outcome measures

Serious bacterial infection (SBI), invasive bacterial infection (IBI), immediate life-saving interventions (ILSIs) and intensive care unit (ICU) admission. The association between high Shock Index (>95th centile) and each outcome was determined by logistic regression adjusted for age, sex, referral, comorbidity and temperature. Additionally, we calculated sensitivity, specificity and negative/positive likelihood ratios (LRs).

Results

Of 5622 children, 461 (8.2%) had SBI, 46 (0.8%) had IBI, 203 (3.6%) were treated with ILSI and 69 (1.2%) were ICU admitted. High Shock Index was associated with SBI (adjusted OR (aOR) 1.6 (95% CI 1.3 to 1.9)), ILSI (aOR 2.5 (95% CI 2.0 to 2.9)), ICU admission (aOR 2.2 (95% CI 1.4 to 2.9)) but not with IBI (aOR: 1.5 (95% CI 0.6 to 2.4)). For the different outcomes, sensitivity for high Shock Index ranged from 0.10 to 0.15, specificity ranged from 0.95 to 0.95, negative LRs ranged from 0.90 to 0.95 and positive LRs ranged from 1.8 to 2.8.

Conclusions

High Shock Index is associated with serious illness in febrile children. However, its rule-out value is insufficient which suggests that the Shock Index is not valuable as a screening tool for all febrile children at the ED.

Keywords: epidemiology, physiology

EU multicentre ED study of presenting vital signs in >5000 febrile children with an association between "shock index" and serious illness, but low sensitivity limits utility in screening.

What is already known on this topic?

Shock Index (heart rate/systolic blood pressure) is a proposed non-invasive measure for haemodynamic assessment.

In children, high Shock Index is associated with major trauma and hospitalisation following emergency department (ED) visit.

Shock Index reference values and the value of the Shock Index to identify serious illness for febrile children attending the ED are unknown.

What this study adds?

In this cohort of febrile children at the ED, we provide reference values for the Shock Index.

High Shock Index is associated with serious illness in febrile children, but its low sensitivity makes it not valuable as a screening tool.

Our study suggests that the Shock Index is not valuable as a routine screening tool in the early assessment of febrile children at the ED.

Background

Early recognition of serious illness is of critical importance in febrile children who attend the emergency department (ED). Correct identification enables timely treatment of children with serious bacterial infections (SBIs) and children in need of intensive care unit (ICU) admission which improves patient outcomes.1–4 A recent review has studied the Shock Index, heart rate divided by systolic blood pressure (BP), as haemodynamic marker to predict disease severity in children and adults at the ED.5 Shock Index in adults has been studied in specific disease groups including trauma and myocardial infarction, and in a large general ED study in which high Shock Index >1.3 at triage has been associated with hospital admission and in-hospital mortality.6 In paediatrics, evidence of the Shock Index is limited to children with trauma,7–10 children with septic shock11–13 and a single-centre general ED population.14 To our knowledge, the Shock Index as a potential non-invasive measure in the early assessment for recognition of serious illness, including need for immediate life-saving interventions (ILSIs) and SBI, has not yet been evaluated. In addition, the association of the Shock Index with ICU admission in febrile children in a multicentre cohort is still unknown.

Like other vital signs, the normal ranges of the Shock Index are age dependent. Population-based centiles for Shock Index have been published for healthy children >8 years.15 Since fever increases heart rate values, reference values based on healthy children may not be generalisable to acutely ill children with fever attending the ED.16 17 In order to facilitate interpretation for clinical practice, clinical cut-off values are needed to classify children with high Shock Index.

We aimed (1) to derive reference values for the Shock Index based on this large ED population and (2) to determine the diagnostic value of the Shock Index for serious illness in febrile children attending European EDs.

Methods

Study design

This is a secondary analysis of the MOFICHE Study (Management and Outcome of Febrile children in Europe), embedded in the PERFORM Project (Personalized Risk assessment in Febrile illness to Optimize Real-life Management across the European Union).18 The MOFICHE Study is an observational multicentre study assessing the management and outcome of febrile children in Europe using routine data. Details of the study design are described previously.19

In short, children from 0 to 18 years presenting with fever (temperature ≥38.0°C) or with fever <72 hours before ED visit were included. Twelve EDs from eight European countries participated as part of the PERFORM Project: Austria, Germany, Greece, Latvia, the Netherlands (n=3), Spain, Slovenia and the UK (n=3). The participating hospitals were either university (n=9) or large teaching hospitals (n=3), and all were partners of the PERFORM consortium. Data were collected from January 2017 until April 2018 for at least 1 year. For the current study, we selected patients with routine BP measurement at the ED. For one ED (London, UK), BP measurements were not available and all visits from this ED were excluded.

Data collected were part of routine care and included sex, mode of referral (self-referral, general practitioner, private paediatrician, emergency medical services or other), comorbidity (chronic condition expected to last ≥1 year),20 alarming signs from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline on fever21 including consciousness (alert, voice, pain, unresponsive) and ill appearance as assessed by the physician, and vital signs: first measurement of temperature, heart rate, non-invasive systolic BP, capillary refill time. Heart rate was measured by pulse oximeters and systolic BP using oscillometric devices. In addition, we collected diagnostics (C reactive protein value (CRP) and blood cultures, cerebral spinal fluid cultures and other cultures) collected at the ED or first day of hospital admission. Further, we collected treatment with ILSI at the ED, defined as airway and breathing support (non-rebreathing mask, (non-invasive) ventilation, intubation), emergency procedures (chest needle decompression, pericardiocentesis or open thoracotomy), haemodynamic support (fluid bolus (>10 mL/kg) or blood administration) or emergency medication (naloxone, dextrose, atropine, adenosine, epinephrine or vasopressors).22 In addition, we collected data of prescribed antibiotics and general ward admission >24 hours, or ICU admission following ED visit.

To classify cause of infection in routine ED practice, we used a consensus-based flow chart19 combining all clinical data and diagnostic results. We used this flow chart to define the presumed cause of infection for each patient (online supplemental appendix 1). The diagnosis ‘definite bacterial’ infection was assigned when pathogenic bacteria were identified by sterile site culture or PCR. Patients were defined as ‘probable bacterial’ when a bacterial syndrome was suspected, but no bacteria were identified and CRP level was above 60 mg/L.23

archdischild-2020-320992supp001.pdf (979.7KB, pdf)

Outcome measures

Serious illness was defined using four different outcomes: SBI, invasive bacterial infection (IBI), ILSI and all visits requiring ICU admission. Definition of SBI was decided on in a consensus meeting of experts in paediatrics and paediatric infectious disease specialists (PERFORM partners). SBI was defined as patients with ‘definite bacterial’ or ‘probable bacterial’ with focus on infection from the gastrointestinal tract, lower respiratory tract, urinary tract, bone and joints, central nervous system or sepsis.24 25 IBI, a subset of SBI, was defined as positive bacterial culture or PCR detection of a single pathogenic bacterium in blood, cerebrospinal fluid or synovial fluid. All cultures that were treated as contaminant and cultures growing contaminants were considered non-IBI.26 In addition, cultures growing a single contaminant or candida were defined positive in patients with malignancy, immunodeficiency, immunosuppressive drugs or a central catheter, since antimicrobial treatment is recommended in these patient groups.27

Data analysis

We described the study population, and compared patients with and without BP measurement and focused the analysis on patients with BP measurement.

Part 1: Shock Index reference values

For the analysis on reference values, we excluded patients with immediate triage urgency as these patients are vitally compromised, and excluded children with missing heart rate values. First, we visualised heart rate and systolic BP by age using scatterplots. Second, we assessed the relation between heart rate and systolic BP using standardised z-scores calculated separately for different age groups: patients >1 year were grouped in 1-year age groups and patients <1 year were grouped in <3 months, 3–6 months and 6 months–1 year. Next, we calculated the Shock Index by dividing heart rate by systolic BP and calculated 95th centile Shock Index values in the different age groups.

Part 2: diagnostic value of Shock Index for serious illness

We evaluated the diagnostic value of the Shock Index using the following analyses: (1) the additional value of the Shock Index over systolic BP alone, (2) diagnostic performance of Shock Index above the 95th centile for each of the outcomes, and (3) stratified for age, we explored age-appropriate cut-off values of Shock Index for the different outcomes.

First, we assessed the additional value of the Shock Index to systolic BP by comparing a model with solely systolic BP to a model with both Shock Index and systolic BP (likelihood ratio test). Second, we used univariable logistic regression analysis to assess the association of Shock Index above the 95th centile with each of the outcomes. In multivariable analyses, we adjusted for age, sex, referral (referred vs self-referred), comorbidity and temperature. A previous study recommends to adjust for age besides the use of age-adjusted vital signs.28 Next, we calculated the diagnostic performance of Shock Index above the 95th centile for each of the outcomes using sensitivity, specificity, and negative and positive likelihood ratios (LRs). Negative LR <0.2 or positive LR >5 was defined as relevant.29 Furthermore, we described the ‘number needed to detect a disease’ which reflects the number needed to be examined in order to accurately detect on a person with the disease.30 Next, the discriminative ability of the Shock Index as continuous predictor for the outcomes was presented by area under the curve of receiver operating characteristics (AUROC) in different age groups. We used the following age groups to ensure sufficient numbers of the different outcomes for analysis: <1 year, 1–5 years, 5–10 years and >10 years. We explored age-appropriate cut-off values of the Shock Index for the different outcomes with a high sensitivity. We determined the optimal cut-off as a sensitivity of at least 90% with maximum specificity.

Missing values

Patients with missing data for the outcomes (cause of infection, focus of infection, ICU admission) were excluded from analysis (n=26). Missing values for referral, comorbidity, temperature, heart rate, capillary refill time and consciousness were multiple imputed including all available information of the patients using the mice package31 which resulted in 20 imputation sets (details in online supplemental appendix 2). In a sensitivity analysis, using a different approach to deal with missing BP data, we selected all EDs with >20% BP measurements and imputed missing BP values. In this subset, we repeated all analyses from part 2. All data analyses were performed in R V.3.6.

Results

Study population

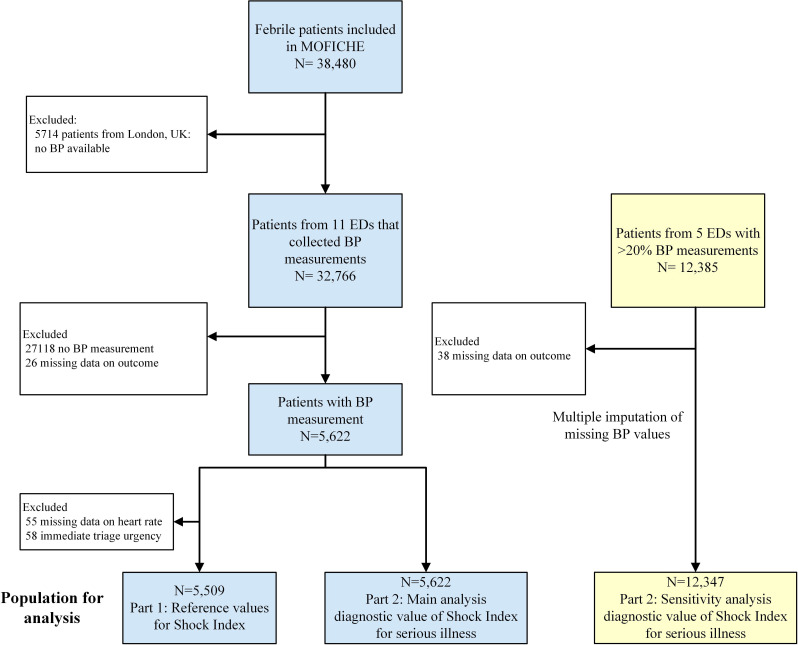

Of 32 766 eligible patients, we included 5622 patients with BP measurement and complete outcome (2548 female (45.3%), median age 4.2 years (IQR 1.8–8.4)) (figure 1). Of those, 1338 (23.8%) patients had comorbidity and 2354 patients (41.9%) were referred to the ED. Regarding the outcomes, 461 patients (8.2%) had SBI, 46 (0.8) IBI, 203 (3.6%) patients were treated with ILSI and 69 (1.2%) were admitted to the ICU (table 1, details in online supplemental appendix 3). Of the 203 patients with ILSI, 30 (17.8%) were admitted to the ICU. Patients with BP measurement had more often one of the outcomes of serious illness than patients without BP measurement (details in online supplemental appendix 4).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of study population. BP, blood pressure; EDs, emergency departments.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of the study population and for the different outcomes

| Study population, n=5622 | Missing | SBI, n=461 | IBI, n=46 | ILSI, n=203 | ICU admission, n=69 | |

| n (%) | n | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| General characteristics | ||||||

| Age in years, median (IQR) | 4.2 (1.8–8.5) | 5.3 (1.8–12.0) | 4.8 (1.3–9.1) | 4.1 (1.5–9.2) | 2.8 (1.1–5.8) | |

| Female | 2548 (45.3) | 228 (49.5) | 21 (45.7) | 89 (43.8) | 36 (52.2) | |

| Comorbidity | 1338 (23.8) | 91 | 167 (36.2) | 29 (63.0) | 92 (45.3) | 28 (40.6) |

| Complex comorbidity | 530 (9.4) | 85 (18.4) | 21 (45.7) | 53 (26.1) | 20 (29.0) | |

| Referred | 2354 (41.9) | 110 | 293 (63.6) | 35 (76.1) | 152 (74.9) | 55 (79.7) |

| Triage urgency | 264 | |||||

| Low: standard, non-urgent | 1746 (31.1) | 184 (39.9) | 6 (13.0) | 23 (11.3) | 5 (7.3) | |

| High: immediate, very urgent, intermediate | 3612 (64.2) | 224 (48.6) | 37 (80.4) | 159 (78.3) | 58 (84.1) | |

| Clinical symptoms | ||||||

| Fever duration in days, median (IQR) | 1.5 (0.5–3) | 704 | 1.5 (0.5–3) | 0.5 (0.5–3) | 0.5 (0.5–1.5) | 0.5 (0.5–1.5) |

| Ill appearance | 868 (15.4) | 620 | 173 (37.5) | 22 (47.8) | 106 (52.2) | 40 (58.0) |

| Decreased consciousness | 82 (1.5) | 90 | 10 (2.2) | 5 (10.9) | 42 (20.7) | 23 (33.3) |

| Vital signs | ||||||

| Temperature in °C, median (IQR) | 37.6 (36.8–38.4) | 480 | 37.9 (37.1–38.7) | 38.4 (37.7–39.2) | 38.2 (37.3–39) | 38.1 (37.1–38.7) |

| Prolonged capillary refill (>3 s) | 105 (1.9) | 866 | 24 (5.2) | 3 (6.5) | 39 (19.2) | 18 (26.1) |

| Tachycardia (APLS) | 1667 (29.7) | 55 | 199 (43.2) | 27 (58.7) | 113 (55.7) | 38 (55.1) |

| Hypotension (APLS) | 209 (3.7) | 38 (8.2) | 3 (6.5) | 22 (10.8) | 10 (14.5) | |

| Shock Index, median (IQR) | 1.2 (1.0–1.4) | 55 | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 1.3 (1.9–1.6) | 1.3 (1.1–1.6) | 1.4 (1.2–1.7) |

| Shock Index, >95th centile for age | 310 (5.5) | 55 | 44 (9.5) | 6 (13.0) | 29 (14.3) | 8 (11.6) |

| Diagnostics and treatment | ||||||

| C reactive protein in mg/L, median (IQR) | 20 (5–61) | 3378 | 91 (38–154) | 58 (17–147) | 20 (5–75) | 19 (4–83) |

| Blood cultures performed | 967 (17.2) | 243 (52.7) | 46 (100) | 118 (58.1) | 44 (63.8) | |

| Cerebrospinal fluid performed | 140 (2.5) | 34 (7.4) | 8 (17.4) | 28 (13.8) | 20 (29.0) | |

| Admission to the ward >24 hours | 1159 (20.6) | 137 | 281 (61.0) | 34 (73.9) | 109 (53.7) | |

| Admission to the ICU | 69 (1.2) | 19 (4.1) | 7 (15.2) | 43 (21.2) | 69 (100) | |

| Antibiotic treatment following ED visit | 1983 (35.3) | 55 | 407 (88.3) | 44 (95.7) | 151 (74.4) | 50 (72.5) |

APLS, advanced paediatric life support; ED, emergency department; IBI, invasive bacterial infection; ICU, intensive care unit; ILSI, immediate life-saving intervention; SBI, serious bacterial infection.

Part 1: Shock Index reference values

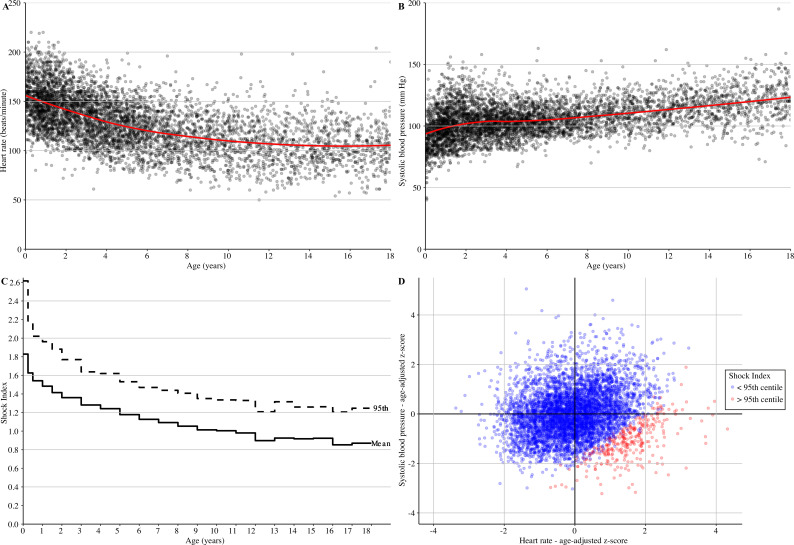

In our cohort of febrile children, systolic BP values increased with age, whereas heart rate and Shock Index values decreased with age (figure 2A–D, online supplemental appendix 5). The 95th centile for Shock Index was 2.61 for children <3 months and decreased to 1.21 for children aged 17–18 years. Overall, Shock Index values were higher in children with tachycardia or hypotension than in children without tachycardia or hypotension (p<0.001). Children with tachycardia or hypotension more often had Shock Index values above the 95th centile (293 of 1765, 16.6%) than children without tachycardia or hypotension (14 of 3744, 0.4%).

Figure 2.

(A) Scatterplots of heart rate for age; (B) systolic blood pressure (BP) for age; (C) step chart of reference values of Shock Index (mean and 95th centile); (D) scatterplot of age-adjusted z-scores of systolic BP for age-adjusted z-scores of heart rate.

Part 2: diagnostic value of Shock Index for serious illness

Overall, 5.5% (310 of 5622) of patients had Shock Index values >95th centile. In patients with SBI, IBI, ILSI or ICU admission, high Shock Index >95th centile occurred in 9.5% (44 of 461), 13.0% (6 of 46), 14.3% (29 of 203) and 11.6% (8 of 69), respectively (table 1).

Addition of Shock Index to the model with only systolic BP led to a significant improved model for each of the outcomes (p<0.05). As a sole predictor, the 95th centile cut-off of Shock Index was associated with SBI (OR 1.9 (95% CI 1.6 to 2.3)), IBI (OR 2.6 (95% CI 1.7 to 3.4)), ILSI (OR 3.1 (95% CI 2.7 to 3.5)) and ICU admission (OR 2.6 (95% CI 1.9 to 3.3)). For SBI, ILSI and ICU admission, this association remained after adjustment for age, sex, referral, comorbidity and temperature (SBI: adjusted OR (aOR) 1.6 (95% CI 1.3 to 1.9); ILSI: aOR 2.5 (95% CI 2.0 to 2.9); ICU admission: aOR 2.2 (95% CI 1.4 to 2.9)), but the association was not significant for IBI (aOR 1.5 (95% CI 0.6 to 2.4)). The 95th centile cut-off of Shock Index had high specificity (all outcomes 0.95 (95% CI 0.94 to 0.95)) and positive LRs ranging from 1.8 to 2.8, but had low sensitivity (range 0.10–0.15) and poor negative LRs (range 0.90–0.95) for the different outcomes (table 2). The number needed to detect a disease for the 95th centile cut-off of Shock Index ranged from 10 to 20 for the different outcomes (table 2). Stratified by age, the AUROC of the Shock Index as continuous predictor ranged 0.55–0.66 for SBI, ranged 0.56–0.74 for IBI, ranged 0.57–0.71 for ILSI, and ranged 0.52–0.73 for ICU admission (table 3). Consequently, when attempting to define age-specific cut-off values, these had high sensitivity (>90%) but low specificity (0%–54%) for the different outcomes (online supplemental appendix 6).

Table 2.

Diagnostic value of high Shock Index >95th centile for serious illness, n=5622

| OR (95% CI) |

aOR* (95% CI) |

Sensitivity (95% CI) |

Specificity (95% CI) |

Positive LR (95% CI) |

Negative LR (95% CI) |

Number needed to detect a disease (N) | |

| SBI, n=461 | 1.9 (1.6 to 2.3) | 1.6 (1.3 to 1.9) | 0.10 (0.07 to 0.13) | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.95) | 1.8 (1.4 to 2.5) | 0.95 (0.93 to 0.98) | 20 |

| IBI, n=46 | 2.6 (1.7 to 3.4) | 1.5 (0.6 to 2.4) | 0.13 (0.05 to 0.26) | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.95) | 2.4 (1.1 to 5.1) | 0.92 (0.82 to 1.03) | 12.5 |

| ILSI, n=203 | 3.1 (2.7 to 3.5) | 2.5 (2.0 to 2.9) | 0.15 (0.10 to 0.20) | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.95) | 2.8 (2.0 to 4.0) | 0.90 (0.85 to 0.95) | 10 |

| ICU admission, n=69 | 2.6 (1.9 to 3.3) | 2.2 (1.4 to 2.9) | 0.13 (0.06 to 0.23) | 0.95 (0.94 to 0.95) | 2.4 (1.3 to 4.5) | 0.92 (0.84 to 1.01) | 12.5 |

*Adjusted for age, sex, referral, comorbidity and temperature.

aOR, adjusted OR; IBI, invasive bacterial infection; ICU, intensive care unit; ILSI, immediate life-saving intervention; LR, likelihood ratio; SBI, serious bacterial infection.

Table 3.

Discriminative value of Shock Index (continuous) for serious illness, stratified for age n=5622

| SBI | IBI | ILSI | ICU admission | |

| AUC (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | AUC (95% CI) | |

| Shock Index (continuous) stratified for age | ||||

| <1 year, n=801 | 0.66 (0.60 to 0.72) | 0.71 (0.56 to 0.85) | 0.70 (0.60 to 0.80) | 0.73 (0.59 to 0.87) |

| 1–5 years, n=2395 | 0.54 (0.49 to 0.59) | 0.56 (0.42 to 0.70) | 0.57 (0.51 to 0.64) | 0.58 (0.47 to 0.68) |

| 5–10 years, n=1330 | 0.56 (0.50 to 0.62) | 0.68 (0.50 to 0.86) | 0.61 (0.52 to 0.69) | 0.52 (0.36 to 0.69) |

| >10 years, n=1096 | 0.55 (0.50 to 0.60) | 0.74 (0.63 to 0.85) | 0.71 (0.64 to 0.79) | 0.72 (0.45 to 0.98) |

AUC, area under the curve; IBI, invasive bacterial infection; ICU, intensive care unit; ILSI, immediate life-saving intervention; SBI, serious bacterial infection.

The sensitivity analysis including all visits from the five EDs with >20% BP measurements (n=12 347) provided similar results for the diagnostic value of Shock Index >95th centile (online supplemental appendix 7).

Discussion

In this large European multicentre study, we provided reference values for Shock Index in febrile children attending the ED. In addition, we evaluated the diagnostic value of Shock Index for serious illness defined as SBI, IBI, ILSI and ICU admission. High Shock Index showed an association with serious illness, but its rule-out value was poor.

Tachycardia and delayed capillary refill are early haemodynamic markers of shock, while hypotension is considered a late sign. The Shock Index combines the properties of heart rate and systolic BP and could potentially improve identification of acutely ill children at the ED. Previous studies in paediatrics have been studying the role of Shock Index in trauma, septic shock, and hospital and ICU admission.5 7 8 10–14 32 33 In our previous single-centre study, we found an association of high Shock Index for hospital and ICU admission in children with different presentations at the ED.14 Although this previous study included both febrile and non-febrile children, our study confirms an association of high Shock Index with SBI, ILSI and ICU admission in febrile children.

In adults, Shock Index values of >0.9 are related to hospital admission and mortality.5 6 In children, reference values and accurate cut-off values for Shock Index are yet unclear. Rappaport et al 15 have provided reference values of the Shock Index for healthy subjects aged >8 years based on auscultatory BP measurements. Gupta and Alam13 reported Shock Index values in a small study of children with sepsis for the outcome mortality. In this study, we provide reference values of the Shock Index for febrile children attending EDs. These values could be used as a reference value for clinical practice or further studies, although generalisability of these values to all febrile children or other populations may be limited.

In our sample of patients with measured BP, Shock Index values above the 95th centile cut-off value were associated with SBI, ILSI and ICU admission adjusted for age, sex, referral, comorbidity and temperature. In this multivariate analysis, Shock Index 95th centile was not significantly associated with IBI although the trend was similar. High Shock Index had high specificity and moderate positive LRs, but had poor rule-out value with low sensitivity and poor negative LRs. Its poor rule-out value makes the Shock Index not a valuable screening tool at the ED. Although we identified age-specific cut-off values with high sensitivity, none had adequate specificity and therefore leading to high number of false positives. Although this was not the focus of our study, the Shock Index may have additional value in specific high-risk patients or as repeated measurement for monitoring disease course or treatment effect.

Physiologically based scores have been developed for the early recognition of disease severity in children including scores as quick Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (qSOFA), quick Paediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction-2 (qPELOD-2) and Liverpool qSOFA (LqSOFA).34–37 In previous ED studies, these scores showed high specificity but low sensitivity for serious illness.36 37 LqSOFA is based on heart rate and capillary refill time as haemodynamic parameters, whereas qSOFA and qPELOD-2 both require BP measurement. Since heart rate and capillary refill time are easy to assess in children, LqSOFA could be more easily implemented than scores that need BP measurement. The low sensitivity of these scores, however, makes them of limited clinical value for routine use at the ED.

Systolic BP measurement is also required for the Shock Index. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence does not advise routine BP measurement in febrile children attending the ED,21 but recommends BP measurement in children with abnormal heart rate or prolonged capillary refill. In our cohort, BP measurement was performed in 1799 of 7804 (23%) of children with abnormal heart rate or capillary refill. This poor adherence to recommendations agrees with findings of moderate adherence to other vital sign measurements in febrile children in different European EDs.38

Strengths of this study include the participation of different EDs in Europe, the detailed data collection and the evaluation of the Shock Index for different definitions of serious illness: SBI, IBI, ILSI and ICU admittance, and adjustment for age, sex, referral, comorbidity and temperature. Our study has limitations. First, the selection of patients with BP measurement could have led to selection bias. Due to the limited number of BP measurements in our cohort, multiple imputation of systolic BP in all patients was not possible. In a sensitivity analysis, we imputed systolic BP in all visits of febrile children at the five EDs with >20% BP measurement and found similar results. This suggests that the selection of patients with BP measurement did not influence our results. The low proportion of BP measurement in our study reflects clinical practice where guidelines do not advise routine BP measurement in febrile children.21 38 Patients with BP measurement, however, likely reflect the group in which the Shock Index would potentially be used in clinical practice.

Second, we focused our analysis on high Shock Index since in febrile children we expect the combination of tachycardia and hypotension to be valuable. However, we recognise that hypotension without compensatory high heart rate is a relevant sign of shock which could result in normal Shock Index values. Lastly, the presence of hypotension or tachycardia may have influenced decisions to initiate treatment with ILSI or paediatric ICU admission. We acknowledge that Shock Index might not be a complete independent variable for these outcomes.

Conclusions

In this large observational study of 11 European EDs, we provide reference values for Shock Index for febrile children at the ED. High Shock Index was associated with serious illness like SBI, IBI, ILSI and ICU admission. For serious illness, the rule-out value of high Shock Index was not sufficient. Our results suggest that the Shock Index is not valuable as a routine screening tool in the early assessment of febrile children at the ED.

Acknowledgments

Members of PERFORM consortium are listed in online supplemental appendix 8.

Footnotes

Twitter: @CarrolEnitan, @rgnijman

Correction notice: This paper has been updated since it was published online. Because of a production error the full title of the paper was omitted and this has now been reinstated.

Contributors: Conceptualisation—NNH, JMZ, DB, EA, UvB, EC, IE, ME, MvdF, RdG, JAH, BK, EL, IM, FM-T, RGN, MP, IR-C, MT, DZ, WZ, ML, CV and HAM. Data curation—NNH, DB, UvB, EC, IE, ME, MvdF, RdG, JAH, BK, EL, IM, FM-T, RGN, MP, IR-C, MT, DZ, WZ, ML, CV and HAM. Formal analysis—NNH, EA and HAM. Methodology—NNH, JMZ, DB, EA, UvB, EC, IE, ME, MvdF, RdG, JAH, BK, EL, IM, FM-T, RN, MP, IR-C, MT, DZ, WZ, ML, CV and HAM. Supervision—HAM. Visualisation—NNH. Writing (original draft)—NNH. Writing (review and editing)—JMZ, DB, EA, UvB, EC, IE, ME, MvdF, RdG, JAH, BK, EL, IM, FM-T, RGN, MP, IR-C, MT, DZ, WZ, ML, CV and HAM.

Funding: This work was supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. 668303), by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centres at Imperial College London, Newcastle Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Newcastle University, and by NIHR Academic Clinical Fellowship award (ACL-2018-21-00 to RN).

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. A data set containing individual participant data will be made available in a public data repository containing a specific DOI. The data will be anonymised and will not contain any identifiable data. The data manager of the PERFORM consortium can be contacted for inquiries (Tisham.de@imperial.ac.uk).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by all the participating hospitals. No informed consent was needed for this study. Austria (Ethikkommission Medizinische Universitat Graz, ID: 28-518 ex 15/16); Germany (Ethikkommission Bei Der LMU München, ID: 699-16); Greece (ethics committee, ID: 9683/18.07.2016); Latvia (Centrala medicinas etikas komiteja, ID: 14.07.201 6. No. Il 16-07-14); Slovenia (Republic of Slovenia National Medical Ethics Committee, ID: 0120-483/2016-3); Spain (Comité Autonómico de Ética de la Investigación de Galicia, ID: 2016/331); The Netherlands (Commissie Mensgebonden onderzoek, ID: NL58103.091.16); the UK (ethics committee, ID: 16/LO/1684, IRAS application no. 209035, confidentiality advisory group reference: 16/CAG/0136). In the UK, an 'opt-out' procedure was used for this study.

References

- 1. Thompson MJ, Ninis N, Perera R, et al. Clinical recognition of meningococcal disease in children and adolescents. Lancet 2006;367:397–403. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)67932-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wolfe I, Cass H, Thompson MJ, et al. Improving child health services in the UK: insights from Europe and their implications for the NHS reforms. BMJ 2011;342:d1277. 10.1136/bmj.d1277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pruinelli L, Westra BL, Yadav P, et al. Delay within the 3-hour surviving sepsis campaign guideline on mortality for patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care Med 2018;46:500–5. 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Torsvik M, Gustad LT, Mehl A, et al. Early identification of sepsis in hospital inpatients by ward nurses increases 30-day survival. Crit Care 2016;20:244. 10.1186/s13054-016-1423-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koch E, Lovett S, Nghiem T, et al. Shock index in the emergency department: utility and limitations. Open Access Emerg Med 2019;11:179–99. 10.2147/OAEM.S178358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Al Jalbout N, Balhara KS, Hamade B, et al. Shock index as a predictor of hospital admission and inpatient mortality in a US national database of emergency departments. Emerg Med J 2019;36:293–7. 10.1136/emermed-2018-208002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Acker SN, Ross JT, Partrick DA, et al. Pediatric specific shock index accurately identifies severely injured children. J Pediatr Surg 2015;50:331–4. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Acker SN, Bredbeck B, Partrick DA, et al. Shock index, pediatric age-adjusted (SIPA) is more accurate than age-adjusted hypotension for trauma team activation. Surgery 2017;161:803–7. 10.1016/j.surg.2016.08.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nordin A, Shi J, Wheeler K, et al. Age-Adjusted shock index: from injury to arrival. J Pediatr Surg 2019;54:984–8. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.01.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Linnaus ME, Notrica DM, Langlais CS, et al. Prospective validation of the shock index pediatric-adjusted (SIPA) in blunt liver and spleen trauma: an ATOMAC+ study. J Pediatr Surg 2017;52:340–4. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.09.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yasaka Y, Khemani RG, Markovitz BP. Is shock index associated with outcome in children with sepsis/septic shock?*. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2013;14:e372–9. 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182975eee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rousseaux J, Grandbastien B, Dorkenoo A, et al. Prognostic value of shock index in children with septic shock. Pediatr Emerg Care 2013;29:1055–9. 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182a5c99c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gupta S, Alam A. Shock Index-A useful noninvasive marker associated with age-specific early mortality in children with severe sepsis and septic shock: age-specific shock index cut-offs. J Intensive Care Med 2020;35:984–91. 10.1177/0885066618802779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hagedoorn NN, Zachariasse JM, Moll HA. Association between hypotension and serious illness in the emergency department: an observational study. Arch Dis Child 2020;105:545–51. 10.1136/archdischild-2018-316231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rappaport LD, Deakyne S, Carcillo JA, et al. Age- and sex-specific normal values for shock index in national health and nutrition examination survey 1999-2008 for ages 8 years and older. Am J Emerg Med 2013;31:838–42. 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hagedoorn NN, Zachariasse JM, Moll HA. A comparison of clinical paediatric guidelines for hypotension with population-based lower centiles: a systematic review. Crit Care 2019;23:380 Online. 10.1186/s13054-019-2653-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nijman RG, Thompson M, van Veen M, et al. Derivation and validation of age and temperature specific reference values and centile charts to predict lower respiratory tract infection in children with fever: prospective observational study. BMJ 2012;345:e4224. 10.1136/bmj.e4224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. PERFORM consortium . Personalised risk assessment in febrile illness to optimise real-life management (PERFORM); 2019.

- 19. Hagedoorn NN, Borensztajn DM, Nijman R, et al. Variation in antibiotic prescription rates in febrile children presenting to emergency departments across Europe (MOFICHE): A multicentre observational study. PLoS Med 2020;17:e1003208. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Simon TD, Cawthon ML, Stanford S, et al. Pediatric medical complexity algorithm: a new method to stratify children by medical complexity. Pediatrics 2014;133:e1647–54. 10.1542/peds.2013-3875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) . Fever in under 5s: assessment and initial managment CG160 May 2013; 2013. [PubMed]

- 22. Lee JY, Oh SH, Peck EH, et al. The validity of the Canadian triage and acuity scale in predicting resource utilization and the need for immediate life-saving interventions in elderly emergency department patients. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 2011;19:68. 10.1186/1757-7241-19-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Herberg JA, Kaforou M, Wright VJ, et al. Diagnostic test accuracy of a 2-Transcript host RNA signature for discriminating bacterial vs viral infection in febrile children. JAMA 2016;316:835–45. 10.1001/jama.2016.11236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nijman RG, Vergouwe Y, Thompson M, et al. Clinical prediction model to aid emergency doctors managing febrile children at risk of serious bacterial infections: diagnostic study. BMJ 2013;346:f1706. 10.1136/bmj.f1706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Irwin AD, Grant A, Williams R, et al. Predicting risk of serious bacterial infections in febrile children in the emergency department. Pediatrics 2017;140. 10.1542/peds.2016-2853. [Epub ahead of print: 05 07 2017]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pneumonia Etiology Research for Child Health (PERCH) Study Group . Causes of severe pneumonia requiring hospital admission in children without HIV infection from Africa and Asia: the PERCH multi-country case-control study. Lancet 2019;394:757–79. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30721-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hagedoorn NN, Borensztajn D, Nijman RG, et al. Development and validation of a prediction model for invasive bacterial infections in febrile children at European emergency departments: MOFICHE, a prospective observational study. Arch Dis Child 2021;106:641–7. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Spruijt B, Vergouwe Y, Nijman RG, et al. Vital signs should be maintained as continuous variables when predicting bacterial infections in febrile children. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:453–7. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Van den Bruel A, Haj-Hassan T, Thompson M, et al. Diagnostic value of clinical features at presentation to identify serious infection in children in developed countries: a systematic review. Lancet 2010;375:834–45. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62000-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Linn S, Grunau PD. New patient-oriented summary measure of net total gain in certainty for dichotomous diagnostic tests. Epidemiol Perspect Innov 2006;3:11. 10.1186/1742-5573-3-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Buuren Svan, Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice : Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Stat Softw 2011;45:67. 10.18637/jss.v045.i03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Strutt J, Flood A, Kharbanda AB. Shock index as a predictor of morbidity and mortality in pediatric trauma patients. Pediatr Emerg Care 2019;35:132–7. 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Traynor MD, Hernandez MC, Clarke DL, et al. Utilization of age-adjusted shock index in a resource-strained setting. J Pediatr Surg 2019;54:2621–6. 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.08.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schlapbach LJ, Straney L, Bellomo R, et al. Prognostic accuracy of age-adapted SOFA, SIRS, PELOD-2, and qSOFA for in-hospital mortality among children with suspected infection admitted to the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med 2018;44:179–88. 10.1007/s00134-017-5021-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leclerc F, Duhamel A, Deken V, et al. Can the pediatric logistic organ Dysfunction-2 score on day 1 be used in clinical criteria for sepsis in children? Pediatr Crit Care Med 2017;18:758–63. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Romaine ST, Potter J, Khanijau A, et al. Accuracy of a modified qSOFA score for predicting critical care admission in febrile children. Pediatrics 2020;146:e20200782. 10.1542/peds.2020-0782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van Nassau SC, van Beek RH, Driessen GJ, et al. Translating Sepsis-3 criteria in children: prognostic accuracy of age-adjusted quick SOFA score in children visiting the emergency department with suspected bacterial infection. Front Pediatr 2018;6:266. 10.3389/fped.2018.00266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. van de Maat J, Jonkman H, van de Voort E, et al. Measuring vital signs in children with fever at the emergency department: an observational study on adherence to the NICE recommendations in Europe. Eur J Pediatr 2020;179:1097–106. 10.1007/s00431-020-03601-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

archdischild-2020-320992supp001.pdf (979.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available in a public, open access repository. A data set containing individual participant data will be made available in a public data repository containing a specific DOI. The data will be anonymised and will not contain any identifiable data. The data manager of the PERFORM consortium can be contacted for inquiries (Tisham.de@imperial.ac.uk).