Abstract

Current care models for older patients with kidney failure in the United States do not incorporate supportive care approaches. The absence of supportive care contributes to poor symptom management and unwanted forms of care at the end of life. Using an Institute for Healthcare Improvement Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement, we conducted a focused literature review, interviewed implementation experts, and convened a technical expert panel to distill existing evidence into an evidence-based supportive care change package. The change package consists of 14 best-practice recommendations for the care of patients seriously ill with kidney failure, emphasizing three key practices: systematic identification of patients who are seriously ill, goals-of-care conversations with identified patients, and care options to respond to patient wishes. Implementation will be supported through a collaborative consisting of three intensive learning sessions, monthly learning and collaboration calls, site data feedback, and quality-improvement technical assistance. To evaluate the change package’s implementation and effectiveness, we designed a mixed-methods hybrid study involving the following: (1) effectiveness evaluation (including patient outcomes and staff perception of the effectiveness of the implementation of the change package); (2) quality-improvement monitoring via monthly tracking of a suite of quality-improvement indicators tied to the change package; and (3) implementation evaluation conducted by the external evaluator using mixed methods to assess implementation of the collaborative processes. Ten dialysis centers across the country, treating approximately 1550 patients, will participate. This article describes the process informing the intervention design, components of the intervention, evaluation design and measurements, and preliminary feasibility assessments.

Clinical Trial registry name and registration number:

Pathways Project: Kidney Supportive Care, NCT04125537.

Keywords: geriatric and palliative nephrology, advance care planning, communication, end of life, goals of care, implementation science, palliative care, shared decision-making, supportive care

Introduction

Current care of older patients with advanced CKD in the United States is not patient centered, nor does it incorporate a supportive care approach to optimize patients’ quality of life. The absence of this approach is a major deficit in care (1). Patients >75 years are the fastest-growing segment of the dialysis population. If they are also frail or sick with multiple comorbid conditions, these patients may not experience a survival benefit from dialysis and are thus candidates for a primary supportive care and often a specialty palliative care approach (2). Further, although these patients often experience a significantly shortened life expectancy, planning for end-of-life care is limited, resulting in higher rates of use of the intensive care unit and in-hospital deaths at the end of life compared with patients with other chronic illnesses (3). Patients likely receive such high-intensity care because their decline is not planned for through sensitive goals-of-care discussions and advance care planning processes. Despite advances in other countries (notably Australia, Great Britain, and Canada), progress on providing patient-centered kidney supportive care has lagged in the United States (4). This article describes development of an intervention to foster uptake of supportive care best practices for patients receiving dialysis.

Intervention Development

The Pathways intervention is a multicomponent intervention structured after the collaborative-learning approach of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Breakthrough Collaborative Model (5). We based the selection of the Breakthrough Collaborative Model on the quality-improvement experience of Quality Insights Renal Network 5. Learning collaboratives are an increasingly accepted tool used to speed diffusion, implementation, and innovation of care models (6,7). The IHI Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement is one systematic, time-limited (12–18 months), tested, format for a collaborative (8). The premise of a Breakthrough Collaborative is that all participant teams teach (sharing knowledge, information, and data) and, through this process, all participants learn, share what they have learned, and repeat the cycle until the spread and adoption of knowledge and improvement is applied to multiple settings. Collaborative participants also learn from, and are coached by, expert faculty in focused topic areas of the “change package” best practices. Another feature of the Breakthrough Collaborative is use of the IHI Model for Improvement, in which teams test a series of small changes using multiple small-scale Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles. In this way, teams incrementally adapt the recommended changes outlined in the change package to their own organizational context. Authors B.V. and D.E.L. attended the IHI Breakthrough Series College in March 2017 to gain a background in conducting a collaborative. In addition, an IHI consultant was retained to advise on development of the change package.

Development of the Change Package

A change package is a set of evidence-based practices to be implemented with quality-improvement methods, and it is a central component of a Breakthrough Collaborative (9,10). To develop the Pathways change package, we followed three steps: (1) conducted a systematic literature review, (2) interviewed implementation leaders and subject-matter experts to identify key considerations in the implementation of supportive care programs, and (3) convened a technical expert panel (TEP) to distill information gathered in the first two steps and prioritize change concepts.

First, we conducted a focused literature review on interventions and outcomes in supportive care for patients with CKD and kidney failure (Supplemental Material 1 for search terms and strategy). The review was intended to add to comprehensive literature reviews conducted on literature from 2000 to 2009 for the US clinical practice guideline development (11), and from 2010 to 2014 for the international Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes Controversies Conference in Supportive Care Project and subsequent published executive summary (12). Therefore, searches were limited to publications in PubMed written in English from January 1, 2010 to January 17, 2017 on adults only.

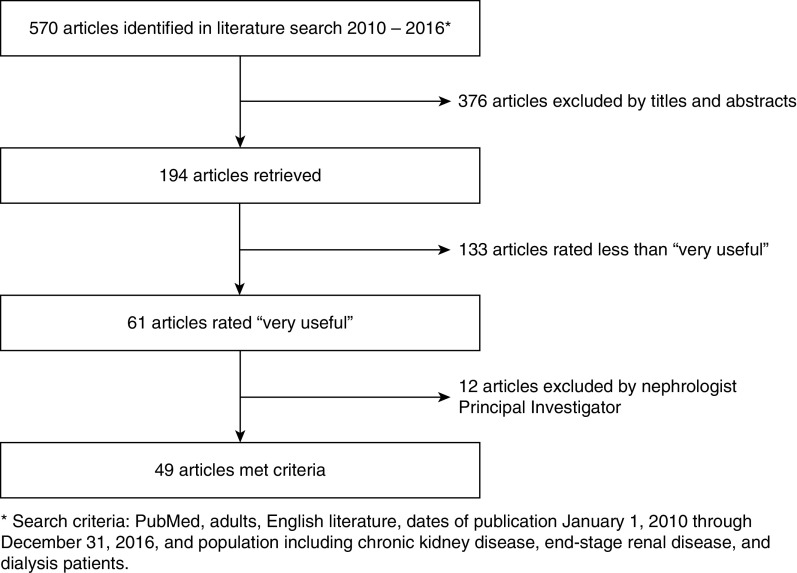

Pathways Project investigators (D.E.L. and A.H.M.) also identified articles of interest through a hand search. After duplicate references were discarded, 570 abstracts and titles were reviewed for possible inclusion (Figure 1). A total of 193 full-text articles were then retrieved and data were abstracted from each article using a concise online electronic coding form to capture information about the intervention features (e.g., disease focus, setting of care), study elements (e.g., design, sample size, population, outcomes assessed), and key outcomes/findings. Twenty professional members of the Coalition for Supportive Care of Kidney Patients volunteered to review the abstracts and rate their usefulness. All raters had substantial clinical or research expertise in supportive kidney care. Raters summarized key findings of the article relevant to delivery of supportive care, and rated the article’s usefulness for “developing a pathway for conservative management, providing supportive care through the continuum of kidney disease, or discontinuing dialysis.” A total of 61 articles were rated “very useful.” These were reviewed by one investigator (A.H.M.) for final inclusion on the basis of relevance and usefulness in developing a change package.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of article selection process for development of the change package. Of 570 articles initially identified, 49 articles met criteria for inclusion.

A list of “pearls” potentially leading to change concepts was compiled from 49 of the 61 very useful articles (Table 1). These were grouped into three conceptual areas: (1) nondialytic management, (2) supportive care throughout the continuum of care, and (3) dialysis withdrawal. When articles were similar in nature, one was selected for inclusion to reduce the burden on the TEP. The systematic literature review was supplemented by a gray literature review to identify tools, measures, and implementation information not covered in the peer-reviewed literature.

Table 1.

Concepts extracted from literature search and provided to technical expert panel for building change package

| Pearl That May Lead to a Change Concept |

| Pathway 1: conservative, nondialytic management |

| Need hospice referral early; increase in symptoms in last 2 mo |

| Patients receiving conservative, nondialytic management may live longer than a year and need to be treated with primary palliative care skills |

| Geriatric syndromes (including frailty), old age, and high comorbidities predict poor prognosis with dialysis; may not be a survival benefit with dialysis |

| Caregivers of patients receiving conservative, nondialytic management need psychosocial support for such patients to do well |

| Quality of life and patient experience better for patients receiving conservative, nondialytic management than for patients receiving dialysis, but survival is shorter; patients willing to trade-off survival for better quality of life |

| About 15% of patients choose conservative, nondialytic management; patients respond well to choice of conservative, nondialytic management when pathway is established and presented as “natural aging” or “holistic care” |

| Erythropoietin-stimulating agents decrease fatigue of patients receiving conservative, nondialytic management |

| Risk algorithms for patients with high 90-d mortality after starting dialysis can be used to inform decision about initiating dialysis |

| A total of 93 patients over age 80 with 1‐ and 5‐yr survivals on dialysis comparable with the population of patients with kidney failure as a whole; need to examine reasons why |

| Pathway 2: supportive care throughout the continuum of care |

| Need someone to “own” symptom assessment who knows how to treat them |

| Summary of overall palliative care approach |

| Referral to nephrologist/palliative care clinician before 3 mo allows time for consideration of all RRT options, including conservative, nondialytic management; preemptive transplant; and home dialysis |

| Patients with CKD perceive end-of-life care practices of dialysis centers as falling short of their many needs; areas of unmet need include advance care planning, pain and symptom management, and psychosocial and spiritual support; need to “normalize” advance care planning discussions earlier in dialysis patient care |

| Need a communication framework for dialysis decisions that identifies patients’ values and goals and results in treatments being aligned with them |

| Frequent outpatient palliative-care clinic visits leads to fewer emergency-department visits and hospitalizations |

| Conceptualize care in all three pathways as patient centered rather than disease oriented |

| A need for all three pathways; patients and families do not understand palliative care and hospice |

| Screen for depression early and often |

| Sharing Patient's Illness Representations to Increase Trust (SPIRIT) is an effective advance care planning intervention to prepare caregivers for decisions and improve bereavement; caregivers have a limited understanding of patients’ values and goals |

| My Kidneys, My Choice is a decision aid to help patients with kidney failure with shared decision making about dialysis options |

| Patients want family members present and for nephrologists to be involved in the advance care planning discussions, and for their desire to participate to be determined before starting |

| A registry of all patients with advanced CKD who were appropriate for supportive care helped to identify what supportive care practices were being provided to patients and how often |

| Pathway 3: dialysis withdrawal |

| Tracking quality of life longitudinally can identify patients who are reconsidering whether dialysis was still worth the life it was providing |

| Need for improved detection of patients who are at high risk of dying; those with loss of independence; clinical deterioration; loss of function; inability to engage in meaningful, enjoyable activities; and those “dying on dialysis” using the surprise question, the integrated prognostic model, or the Renal Epidemiology Information Network prognostic score so that palliative care interventions, including advance care planning, can be offered to them |

| Develop advance care plan for patients at high risk of dying, including Physician or Provider Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment form, which has been shown to increase out-of-hospital death and hospice admission |

| Ethics committee deliberation on 111 patients who were being considered for withdrawal over an 8-yr period; patients were identified by new, severe, comorbid conditions, such as a stroke, intractable pain, or hemodynamic instability on dialysis |

| Nine advance care planning interventions have been studied in patients with kidney failure; one demonstrated improved patient and family well being and anxiety; others noted the importance of instilling patient confidence that their advance directives will be enacted and discussing decisions about (dis)continuing dialysis therapy separately from “aggressive” life-sustaining treatments (e.g., ventilation) |

Pathways investigator D.E.L. interviewed 17 nephrology and palliative care implementation leaders who had implemented some element of kidney supportive care in English-speaking countries (see Supplemental Material 2 for interview guide). The interviews addressed critical success factors for establishing a supportive care program and overcoming implementation barriers. Five core components needed to create a system of supportive care emerged from these interviews: (1) appropriate patient identification; (2) communication about advance care planning, and goals of care conversations; (3) symptom assessment and management; (4) collaboration with palliative care specialists; and (5) early referral to community resources, such as hospice (4). These elements were presented to the TEP to consider for inclusion in the change package.

We convened a 15-member, multidisciplinary TEP consisting of patient subject matter experts (SMEs) and professionals in the areas of nephrology, healthcare policy, palliative care, hospice, and ESKD Seamless Care Organizations. There were representatives from nephrology academic programs, large dialysis organizations, nephrology nursing, hospice and palliative care organizations, and an observer from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The disciplines of medicine, nursing, social work, chaplaincy, and healthcare administration were represented. The two patient SMEs had personal experience living with kidney failure. The TEP was sent a summary of the focused literature and the gray literature reviews before meeting, along with several key articles. The TEP met in person for 2 days in April 2017, guided by an experienced facilitator from the IHI.

The TEP was asked to evaluate and recommend best practices to include in each supportive care pathway in the change package. To develop this, the TEP discussed deficits in kidney supportive care and then developed a vision for the ideal state of goal-concordant care for patients seriously ill with kidney failure (Supplemental Material 3). They defined the ideal system as one in which patient values, preferences, and goals are elicited and respected; patients receive care that aligns with what matters most to them; and patients and families receive support, resources, and assistance to help them prepare for the end of life. They then considered the summary of evidence to develop recommendations for what evidence-based best practices would help achieve that ideal state.

After the in-person meeting, the change package was iteratively revised with TEP feedback. During this process, we paid careful attention to the use of consistent terminology that could be understood by patients and other stakeholders. For instance, on the recommendation of the patient SMEs, we agreed to use the term “medical management without dialysis” rather than “conservative care.”

The final change package consists of 14 evidence-based best practice recommendations (Supplemental Material 4, change package summary) grouped into four “change concepts”: (1) supportive care capacity (create the system); (2) values guide care (elicit and respect patient values and preferences); (3) just right care (provide the right care to the right person at the right time); and (4) throughout the continuum (bring enhanced support at the end of life). In the full change package, each best practice is concisely described using the following content: purpose, evidence, improvement process, challenges and strategies to surmount them, resources and tools, and key references (http://go.gwu.edu/pathwaysprojectchangepackage). The goal of each best-practice recommendation is to provide actionable evidence, rationale, and steps to guide improvement in that area.

Recognizing that the entire change package of 14 best practices would be overwhelming for centers to implement at one time, we prioritized three. Their selection was determined on the basis of input from the TEP, the findings from the literature reviews, and input from the organizational leaders of the participating dialysis organizations. The best practices selected were as follows: identification of patient who is seriously ill, shared decision making and advance care planning, and palliative dialysis or a systematic dialysis withdrawal process for appropriate patients. Dialysis-organization leaders were strongly in favor of concentrating on patients who were seriously ill, rather than attempting to reach all patients in the dialysis center. Prioritizing patients who were seriously ill provided a tactical solution to overcoming the barrier of lack of clinician time to implement supportive care practices or engage in advance care planning. Furthermore, some TEP members expressed reservations about discussing end-of-life issues with patients who were healthier who were intent on adapting well to dialysis and/or were hoping to receive a transplant. Although all patients can benefit from sensitive discussions of goals of care, the dialysis-organization representatives on the TEP felt that starting with patients who were seriously ill would face less resistance from clinicians.

Additional Intervention Components

The classic Breakthrough Collaborative contains a number of components in addition to the change package: learning sessions, action periods, quality-improvement processes, and data collection for formative evaluation (13). We followed this schema in designing the Pathways learning collaborative (Table 2). The Pathways collaborative includes three in-person “learning sessions” of 2 days each, which are intended for “change teams” of up to five people from each participating site. In the months between learning sessions, deemed “action periods,” sites will work on implementing the best practices introduced at the learning session. During action periods, teams are expected to engage with one another through the use of multiple supports that promote shared learning; collect and submit monthly data; review monthly feedback reports; attend Pathways Project webinars and conference calls facilitated by faculty experts; and perform iterative tests of the change package recommendations via the Plan-Do-Study-Act approach, which asks three fundamental questions: What are we trying to accomplish? How will we know that a change is an improvement? What change can we make that will result in improvement?

Table 2.

Elements of the Pathways intervention determined on the basis of Institute for Healthcare Improvement Collaborative Model for Achieving Breakthrough Improvement

| Intervention Element | Description | Purpose |

| Start-up | ||

| Change package (Supplemental Material 2) | Set of 14 evidence-based best practices developed through literature review and input of technical expert panel, guiding improvement efforts designed to improve kidney supportive care and to achieve goal-concordant care, especially at the end of life. | Provide written guidance as to what to do, how to do it, and why |

| Change team and charter | Designated team from each participating dialysis center or CKD clinic that has agreed to work toward improvement of supportive care at their site. Each team develops a charter that specifies their goals, objectives, and plans. Teams needed to have at least one nephrologist “champion.” Other disciplines participated on the basis of site and personal preference and included social workers, nurse practitioners, administrators, patient advocates, and palliative care physicians. | Clearly identify who is going to lead change at clinical site and foster agreement on change team about their plans |

| Expert faculty | Interdisciplinary experts in supportive kidney care serve as faculty. Disciplines include nephrology, palliative medicine, social work, nursing, dialysis center administration, quality improvement, public health, and patient expertise. | Teach and mentor content and skills needed to implement kidney supportive care |

| Resource-rich intranet website and listserv | Website accessible to Pathways participants where all resources introduced during learning sessions or activity periods are housed for reference by teams. Also includes YouTube channel with videos produced by Pathways team and listserv for use by all Pathways participants. | Foster ongoing communication between teams and with faculty; promote easy access to information and tools that teams may need for implementation of supportive care |

| Learning sessions during collaborative | ||

| Learning sessions | Three in-person, 2-d mini conferences where teams gather to learn content, practice skills, share learning, and plan improvement activities. Each learning session has a mix of didactic teaching from experts, opportunities to practice skills, and time to share innovations with other teams. | Foster sharing of innovations through the “All Teach, All Learn” approach of the collaborative; purpose is to provide both content knowledge about how to make change, and emotional support for the process of incrementally pushing change forward |

| Communication-skills training | Trained communication facilitators, from the Veterans Administration Goals of Care Conversations Skills Training for Clinicians program, delivered 7 h of content in learning session 1. This content is based on the VitalTalk model and was explicitly adapted to nephrology concerns and situations (14). | Bolster communication skills to enable participants to increase confidence and competence in conducting goals-of-care conversations, including both shared decision making and advance care planning |

| In learning sessions 2 and 3, Pathways faculty provide additional communication-skills exercises to continue building skills with goals-of-care conversations using the Ask-Tell-Ask model. | ||

| Storyboard sessions | Each team prepares a poster that explains their progress, barriers, and key innovations. These are shared in a poster session at the learning session. | Foster sharing and spread of innovations; build team pride and enthusiasm for their work through presentation to peers |

| Activity periods between learning sessions | ||

| Pathways action calls (monthly) | Monthly videoconference call with faculty and all change teams. Teams report on successes and frustrations. Faculty provide additional teaching, especially focused on communication skills and symptom management. Cases teams have encountered are debriefed. | Reinforce skills; exchange strategies between teams for overcoming obstacles; celebrate successes to build shared commitment to change |

| Quality-improvement indicator reports | Monthly reports provided to sites showing data on set of commonly collected quality indicators. | Helps sites benchmark and see progress of their site; monitoring quality indicators helps sites recognize areas of success and areas for improvement |

| Individual trend reports provided to each site showing their own trend month to month. | ||

| Improvement-advisor monthly calls | Improvement advisor on the faculty holds call with each team separately each mo to discuss progress and plan for tests of change. | Provide technical assistance to sites on quality-improvement process using small tests of change; encourage sites to embed successful practices into standard workflows and processes |

| Site visits | Small teams of faculty (two to three faculty) visit each site for approximately half a day to meet with change team and other staff. Faculty consult with change team on their progress. Faculty model goals-of-care conversation with patient(s) and debrief with change team. All nephrologists (not just the champion[s]) are invited to lunch or dinner meeting with faculty nephrologist for talk on supportive kidney care and discussion of how this affects their practice. | Builds rapport between faculty and change team; allows faculty to better understand environment at each site;modeling goals-of care conversation in person with patient at the site helps change team to see how to move from the role plays practiced in the learning sessions to actually integrating the conversations in their work setting;meetings with other nephrologists helps the champion build support among colleagues and center leadership |

| Newsletter and email notices | Periodic newsletters with information, new relevant evidence, and reminders. | Keep Pathways participants up to date on latest evidence related to kidney supportive care and help them see the rich variety of resources available in this area; also builds connection and a sense of belonging to a larger mission |

| Faculty consultation as needed | As requested by local sites, faculty consult via phone or videoconference. | Provide ready access to expert consultation as needed |

| Customized tools and resources as needed | As sites identify areas of need, Pathways team develops additional tools or resources. For instance, a pocket card using Ask-Tell-Ask communication cues was developed after faculty observed the need for a reminder staff could keep with them on the floor (see Supplemental Material 3). | Provide targeted help as additional areas of need are identified |

The curriculum for the three learning sessions covers (1) Pathways best practices, with emphasis on the three required practices; (2) communication skills for conducting goals-of-care conversations; and (3) quality improvement and implementation (Table 3). On the basis of recommendations from the TEP, the curriculum places a heavy emphasis on improving communication skills. Before designing the Pathways curriculum, we piloted a communication module taught by VitalTalk faculty with a subset of the Pathways dialysis center teams. This led us to collaborate with the Veterans Affairs (VA) National Center for Ethics in Health Care to further adapt communication-skills training to nephrology-specific situations on the basis of the VA’s Goals of Care Conversations Skills Training for Clinicians (medical doctors, advanced practice registered nurses, and physician assistants), which is, in turn, based on VitalTalk (14,15). The nephrology-specific communication materials are now available at https://www.ethics.va.gov/goalsofcaretraining/RenalTeams.asp. The curriculum for the first learning session includes 7 hours of communication training delivered by VA faculty trainers. Reinforcement of communication skills is a regular part of the monthly Pathways action call and is modeled by faculty during site visits. Beginning with the second learning session, the curriculum shifts to emphasize a nephrology-specific form of the Ask-Tell-Ask process that we adapted specifically to address kidney failure issues (Supplemental Material 5).

Table 3.

Overview of learning session objectives and activities

| Objectives | Didactics and Activities |

| Learning session 1 | |

| Understand Pathways Project best practices, including identification of patients who are seriously ill | Introduce Pathways project best practices |

| Describe the surprise question as a prognostication tool | |

| Kidney Innovations Café; tabletop discussions | |

| Enhance communication skills for shared decision making and advance care planning | Goals-of-care conversation training using Veterans Affairs faculty and curriculum based on VitalTalk (8 h total) |

| Communication skills: responding to emotion, eliciting patient’s goals, establishing plans to meet goals | |

| Skill practice and role play of common nephrology communication scenarios | |

| Responding to patient values | |

| Integrate supportive care into kidney care setting using incremental changes and PDSA cycle | Description of IHI Breakthrough Series, including PSDA cycles |

| Each team plans initial change project with faculty input | |

| Develop team charter, including implementation goals | |

| Understand and be prepared for data collection and submission of data for project | Description of data-collection processes |

| Demonstration of data-collection tools | |

| Learning session 2 | |

| Demonstrate steps to conduct advance care planning, shared decision making, and goals of care with patients seriously ill with kidney disease | Enhanced Communication Skills Training: using Ask-Tell-Ask; responding to emotion, empathy |

| Advance care planning discussion with palliative medicine physician | |

| Patient panel discussion | |

| Describe approaches to providing MMWD | Video interview with physician leader in MMWD in Australia |

| Breakout session: MMWD for CKD teams | |

| Breakout session: palliative dialysis for dialysis center teams | |

| Identify ways to implement Pathways best practices for supportive care of patients who are seriously ill | Collaborative sharing through storyboards |

| Idea sharing between sites | |

| Discipline-specific conversations to address shared concerns | |

| Implementation strategies | |

| Apply appropriate steps of IHI Breakthrough model of healthcare improvement techniques to implement small tests of change | Small tests of change; the PDSA cycle |

| Team working time: fishbone diagram for root cause analysis | |

| Learning session 3 | |

| Share successes and challenges in implementing supportive care | Visual storyboard presentations |

| Interdisciplinary panel of successful project teams | |

| Foster momentum for implementing Pathways best practices | Discuss implementation challenges |

| Plans to overcome challenges; collaborative discussions | |

| Data collection | |

| Use frameworks for sustainability planning to anchor changes to existing processes and “holding the gains” | “Fostering-sustainability” lecture |

| Developing a sustainability plan | |

| Fishbowl discussion: case study on sustainability plan with one site | |

| Identify opportunities and resources for spread within organization | Panel of innovative US models transforming the kidney care system |

| How to “nudge” organization culture | |

PDSA, Plan-Do-Study-Act; IHI, Institute for Healthcare Improvement; MMWD, medical management without dialysis.

Implementation of what is learned in the didactic learning sessions is a core aspect of the collaborative. To support implementation, we enlisted an expert quality-improvement advisor to conduct monthly calls with each site to discuss their change efforts and help them plan realistic tests of change, placing emphasis on helping teams integrate the Pathways best practices into the ongoing workflow that is already required of dialysis centers.

Finally, we plan to have Pathways faculty visit the sites in person several times to address questions and provide mentoring on implementation. In particular, one of the faculty will demonstrate goals-of-care conversations using the Ask-Tell-Ask approach (16) with one or two of each dialysis center’s patients who are seriously ill, and then debrief with the clinical staff.

Implementation and Effectiveness Study: Design, Setting, and Measurements

The funding organization engaged an external evaluation team who designed a mixed-methods hybrid implementation-effectiveness study (17). The study’s timeline for implementation and evaluation, determined on the basis of the funding organization’s parameters, was 18 months. In this hybrid design, dual evaluation of implementation and pilot clinical effectiveness is conducted to facilitate adoption in the real-world setting. The recommended change-package interventions require significant behavior change on the part of the individual clinical team members, changes across levels in an organization, and collaboration with outside partners (hospice and palliative care). In addition, the intervention is intended to be flexible to allow participant teams to choose what they implement and where. Therefore, each clinic is likely to implement a different package of interventions and, after 18 months of implementation, changes will not be fully in place.

The study was approved by the George Washington University Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Design

The evaluation design combines an evaluation conducted by the Pathways Project team, which includes both formative and summative evaluation components and an implementation evaluation conducted by the outside evaluation team. In combination, the evaluation encompasses three related components: (1) effectiveness evaluation (including patient outcomes and staff perception of the effectiveness of the implementation of the change package); (2) quality-improvement monitoring via monthly tracking of a suite of quality improvement indicators tied to the change package; and (3) implementation evaluation conducted by the external evaluator, using mixed methods to assess implementation of the collaborative processes.

The effectiveness evaluation will use a prepost design to assess changes in patient-reported outcomes and staff-reported outcomes. Several alternative design options were considered, including randomizing intervention and control clinics, but the participating organizations did not feel this was feasible due to business needs. We also explored the potential for a step-wedge design, but this was not feasible due to program costs and time frame.

Setting

Dialysis organizations involved in an integrated kidney care or value-based purchasing model were invited to participate. The rationale was that these models created incentives, both financial and organizational, to implement innovations. We also recruited a VA Medical Center site because the VA operates within a comprehensive, coordinated care system. However, the VA team joined the project and received IRB approval almost 9 months later than the other sites. Because of the delay, the VA data are not included in the baseline data reported here for the other ten dialysis centers.

The evaluation will include ten dialysis centers, representing a range of geographic regions and treating approximately 1550 patients receiving dialysis. These dialysis centers are part of three medium-size dialysis organizations, two of which are not-for-profit organizations. Three CKD practices associated with the dialysis centers also participated in the learning collaborative, but will not be included in the formal evaluation because the setting and patient population differs so greatly from the dialysis centers.

Data collection will occur at the participant level and at the dialysis center level. Individual-level data collected at baseline and at the end of the study will include patient-reported measures, utilization outcomes for patients who are seriously ill, staff surveys, qualitative observations of collaborative activities, and interviews with implementation teams. Center-level data will include baseline and end-of-study chart audits, and monthly implementation-process measurements.

Measurements

Table 4 lists the study instruments; Table 5 displays the schedule for data collection. There will be two primary outcome measures for the effectiveness evaluation. The primary patient-reported outcome will be quality of end-of-life communication, as measured by the Engelberg quality of communication subscale on end-of-life communication (18). The additional primary outcome measure is change in comprehensive advance care planning documentation, as measured with the chart audit tool developed for the study (Supplemental Material 6a). We explored direct measurement of goal-concordant care as the primary outcome. However, after reviewing many candidate measures, we concluded there was, as yet, no reliable measure for this concept (19–21). Several projects to develop such a measure were in initial stages, but were not yet ready for use.

Table 4.

Measurement domains and data-collection instruments

| Measurement Type/Data-Collection Method | Subdomain | Instrument |

| Patient-reported outcomes/telephone survey of patients who are seriously ill (Supplemental Material 6b) | Readiness for advance care planning | Sudore four-item advance care planning survey (31) |

| Global quality of communication | Heard and Understood one-item measure (32) | |

| Quality of communication about end-of-life care | Quality of Communication 13-item questionnaire (18) | |

| Two subscales: | ||

| General communication | ||

| EOL communication | ||

| Shared decision making | CollaboRATE three-item measure (33) | |

| Patient demographics | Patient demographics and clinical characteristics | |

| Team-reported outcome/survey (Supplemental Materials 6c and 6d) | Supportive care in practice setting |

|

| Integration of new practices | NoMAD (34) | |

| Project progress | IHI Project Progress Assessment Scale (35) | |

| Quality of advance care planning as recorded in medical record/chart audit (Supplemental Material 6a) | Completeness of ACP documentation | Chart audit codeveloped by Pathways and Stanford team |

| Elements covered: | ||

| Decision-making capacity assessed | ||

| Surrogate named | ||

| Goals-of-care discussion documented | ||

| Advance directives discussed and completed if a patient so chooses | ||

| Medical order(s) completed as appropriate (Do Not Resuscitate or POLST paradigm) form | ||

| Advance directives retrievable in the electronic health record | ||

| Advance directives or POLST/medical orders entered in the electronic regional registry if available | ||

| Utilization/monthly facility quality indicator report | Patient utilization: | |

| Seriously ill indicator | ||

| Nursing home or assisted-living residence | ||

| Discontinued dialysis | ||

| Palliative dialysis | ||

| Emergency-department visit | ||

| Hospitalized overnight | ||

| Admitted to hospice | ||

| Died | ||

| Site of death | ||

| Nonequivalent dependent variables/monthly facility quality-indicator report | Variables to control for secular trends not affected by Pathways intervention: | |

| Missed treatments | ||

| Patients in nursing homes or assisted living | ||

| Mean serum albumin for facility |

EOL, end of life; IHI, Institute for Healthcare Improvement; ACP, advanced care planning; POLST, Physician or Provider Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment.

Table 5.

Pathways Project data-collection overview

| Measure | Mo 0; LS-1 | Mo 0–6; Action Period 1 | Mo 6; LS-2 | Mo 7–11; Action Period 2 | Mo 12; LS-3 | Mo 13–16; Action Period 3 | Mo 16–18; Follow-Up Data Collection |

| Patient-reported outcomes | |||||||

| Patient telephone survey | Once | Once | |||||

| Team-reported outcomes | |||||||

| KSC-IQ (all staff) | Once | Once | |||||

| NoMAD (change team staff only) | Once | Once | Once | ||||

| Quality of advance care planning | |||||||

| Advance care planning chart review for patients who are seriously ill | Once | Once | |||||

| Patient-level data | |||||||

| Demographics and service utilization of patient who is seriously ill | Monthly May–July | Monthly July–September | |||||

| Facility-level quality indicators | |||||||

| Aggregate utilization and quality indicators | Monthly | Monthly | Monthly | Monthly |

LS, learning session; KSC-IQ, Kidney Supportive Care Implementation Quotient.

Secondary outcomes include patient-reported outcomes of engagement in advance care planning, shared decision making, quality of end-of-life communication (Supplemental Material 6b), staff report of supportive-care provision (Supplemental Material 6c), and staff report of implementation (Supplemental Material 6d). Exploratory outcomes include provision of palliative dialysis, withdrawal from dialysis, emergency-department visits, hospitalizations, and hospice admissions.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Clinicians at each center will use the “surprise question” to identify patients who are seriously ill (22,23). At baseline and end of study, patients identified as seriously ill in the previous 3 months will be invited to complete a telephone survey. Exclusion criteria include age <21 years; impaired cognition, as determined either by dialysis center or by research coordinators; language other than English or Spanish. (The original protocol submitted to ClinicalTrials.gov specified a cutoff age of 18 years. This was modified to 21 years on the advice of the participating sites.) The survey will be administered by telephone by trained interviewers from the West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science Institute. We will use validated survey instruments to assess quality of communication, engagement in advance care planning, and shared decision making among patients who are seriously ill (Table 4).

Chart Audit of Advance Care Planning Documentation

The chart audit will be conducted by research associates, at each site, on the charts of patients identified as seriously ill by dialysis center clinical staff, using a checklist developed for the purpose of this study to assess goals of care documentation (see Supplemental Material 6a for audit tool and instructions). Auditors from each site were trained in the use of the tool by Pathways staff via a webinar and provision of detailed audit instructions. The checklist assesses whether the following are present in the chart: (1) decision-making capacity assessment; (2) a Do-Not-Resuscitate or medical order (Medical Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment, also called Physician or Provider Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment in some states); (3) the patient’s designated healthcare agent and, if so, whether contact information was also present; (4) an advance directive and, if so, whether a copy of it was present; (5) a goals-of-care discussion and, if present, what the patient’s preferences were; and (6) an advance directive or medical order and whether it had been placed in the local hospital electronic medical record system and/or regional or statewide registry.

Nonequivalent Dependent Variables

In addition to measuring process outcomes that we expect to change, we also plan to measure processes that we do not expect to be affected by the intervention. Use of such nonequivalent dependent variables is a technique used in quasi-experimental designs to mitigate internal threats to validity in such quasi-experimental designs (24). We chose three nonequivalent dependent variables: number of missed treatments; number of patients living in nursing homes or assisted living; and mean serum albumin, which we thought might be affected by secular trends but not by the Pathways intervention.

Implementation Processes and Outcomes

Implementation processes and outcomes will be assessed using mixed methods, including surveying dialysis center implementation teams on integration of change-package elements into routine work, observation of collaborative activities, and interviews with a subset of implementing teams at the end of the study. Implementation outcomes will use the framework of Proctor et al. (25). The dialysis center staff will complete one survey at baseline and end of study (Kidney Supportive Care Implementation Quotient [KSC-IQ]) and a second survey during implementation and at the end (NoMAD survey; Normalization Process Theory. available at http://www.normalizationprocess.org/nomad-study/). The KSC-IQ assesses staff perception of how well their organization delivers 17 components of kidney supportive care. Survey questions are scored on a Likert scale from one to three, and are tied to the best practices in the evidence-based change package. The NoMAD survey measures implementation processes from the perspectives of implementers; the measure was only perceived to be appropriate once the sites were familiar with the new practices and could judge their utilization (i.e., after learning session 1). Both surveys can be completed either online or on paper.

Utilization

The evaluation will include several exploratory utilization outcomes. These include goals-of-care conversations held within 30 days of discharge from the hospital, frequency of palliative dialysis (defined as nonstandard dialysis schedule or prescription), dialysis withdrawal, the number of emergency-department visits and hospitalizations, hospice admissions, and site of death. Utilization measures will be collected monthly for all patients identified as seriously ill in the previous month.

Baseline Participant Demographic Data, Baseline Chart Audit, and Feasibility of Data Collection

Study Participants

During the 3-month baseline period, the average total census at the ten reporting dialysis facilities was 1544 patients. (The protocol filed with ClinicalTrials.gov specified a 4-month baseline period. This was shortened to 3 months due to delays in IRB approval which delayed the start of the patient telephone survey.) Sites screened 98% of patients each month and identified 19% as seriously ill. As expected, the census of patients who were seriously ill varied from month to month as new patients were identified, while others died or were transferred to other centers. This resulted in a cumulative total of 335 patients who were seriously ill at baseline, of whom 179 (53%) initially agreed to be contacted. Of these 179 patients, we reached 59 (33%) with up to three contact attempts. The reasons for surveys not being completed were that 61 patients could not be reached by phone (no answer or voice mailbox full), 49 declined to participate once reached (not interested or did not feel well or were too cognitively impaired), and ten died before they could be contacted. Table 6 presents the demographics for the patients who were surveyed and those who were not. The majority of patients in both groups were White, ≥65 years old, and had been on dialysis ≥3 years. The significant differences between the groups were that the surveyed group had higher percentages of Black patients and of English-speaking patients, and a lower percentage of Asian patients, perhaps because of language barriers (P=0.02 for race; P=0.01 for primary language).

Table 6.

Demographics of patients who were seriously ill by baseline interview status, N=335

| Variables | Interviewed (N=59), N (%) | Not Interviewed (N=276), N (%) | P Value | Missing (%) |

| Male sex | 30 (51) | 165 (60) | 0.25 | 0.3 |

| Age group (yr) | 0.72 | 2 | ||

| <55 | 7 (12) | 31 (12) | ||

| 55–64 | 15 (25) | 67 (25) | ||

| 65–74 | 23 (39) | 85 (32) | ||

| 75–84 | 8 (14) | 55 (20) | ||

| ≥85 | 6 (10) | 31 (12) | ||

| Race | 0.02 | 0.6 | ||

| White | 32 (54) | 168 (61) | ||

| Black | 22 (37) | 59 (22) | ||

| Asian | 1 (2) | 27 (10) | ||

| Other | 4 (7) | 20 (7) | ||

| Non-Hispanic Ethnicity | 40 (74) | 172 (69) | 0.60 | 10 |

| Medicaid=yes | 26 (53) | 140 (63) | 0.29 | 18 |

| Primary language | 0.01 | 24 | ||

| English | 45 (92) | 151 (73) | ||

| Spanish | 4 (8) | 36 (18) | ||

| Other | 0 (0) | 19 (9) | ||

| Years on dialysis | 0.98 | 0.3 | ||

| <1 yr | 10 (17) | 48 (18) | ||

| 1–2 yr | 18 (31) | 80 (29) | ||

| ≥3 yr | 31 (53) | 147 (54) | ||

| Site | 0.23 | 0.0 | ||

| Site 1 | 2 (3) | 10 (4) | ||

| Site 2 | 12 (20) | 49 (18) | ||

| Site 3 | 2 (3) | 28 (10) | ||

| Site 4 | 5 (9) | 11 (4) | ||

| Site 5 | 10 (17) | 22 (8) | ||

| Site 6 | 3 (5) | 23 (8) | ||

| Site 7 | 3 (5) | 15 (5) | ||

| Site 8 | 8 (14) | 26 (9) | ||

| Site 9 | 4 (7) | 25 (9) | ||

| Site 10 | 10 (17) | 67 (24) |

Chart Audit

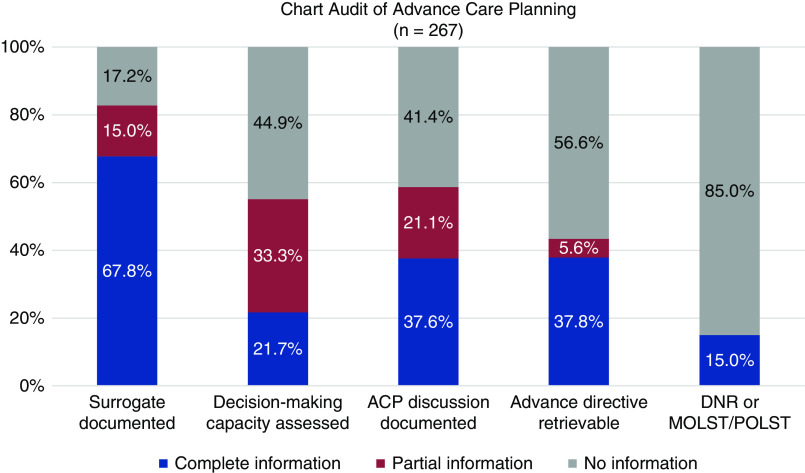

The chart audit was conducted on 267 (94%) of 284 patients who were identified as seriously ill in the first month of the baseline period (May 2019). Charts were rated as containing complete, partial, or no information on each variable. (Figure 2) Across all sites, 181 charts (68%) contained complete information about the patient’s designated healthcare agent, including how to contact the agent; 40 (15%) had partial information; and 46 (17%) had no information. Documentation of assessment of decision-making capacity was complete in 58 charts (22%), partial in 89 (33%), and missing in 120 (45%). Documentation of a goals-of-care discussion, including the patient’s particular preferences, was found in 100 charts (38%), with no goals-of-care discussion noted in 110 charts (41%). A copy of an advance directive was retrievable from 101 charts (38%); a statement that the patient had an advance directive, without the document being available in the chart, was found for 15 patients (6%); and 151 charts (56.6%) had no information about an advance directive. Medical orders—such as Do Not Resuscitate or Medical Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment/Physician or Provider Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment—were even rarer in the charts of these patients who were seriously ill; they were only present in 40 charts (15%).

Figure 2.

Baseline documentation of advance care planning in charts of seriously ill patients. Availability of complete information about different components of advance care planning varied, from high of 68% of patients with complete information about a surrogate, to low of 15% of information with a medical order such as DNR or POLST accessible in the chart. ACP, advance care planning; DNR, Do Not Resuscitate; MOLST, Medical Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment; POLST, Physician or Provider Order for Life-Sustaining Treatment.

Dialysis Staff Survey

For the baseline KSC-IQ survey, 156 staff submitted responses via either email or an online portal. Sites were asked to distribute the survey widely to all staff at the center. The number of returned surveys varied widely, from three responses at one site to 31 at another site.

Discussion

The Pathways Project is a novel approach to address the major clinical problem of poor-quality end-of-life care for many patients receiving dialysis. It is the first effort in the United States to standardize elements of kidney supportive care and implement them in multiple sites that are part of multiple dialysis organizations. To our knowledge, it is also the first time that a learning-collaborative model has been used to guide implementation of kidney supportive care. As called for in the Breakthrough Collaborative model, an evidence-based change package will provide the content guidance as teams work to set and achieve improvement goals. To improve supportive care practices, all teams are asked to implement the following interventions: to systematically identify patients who are seriously ill; conduct shared decision-making and advance care planning conversations with them; and respond, when appropriate, with palliative dialysis options or supported options for stopping dialysis, including hospice referral. The education about, and implementation of, kidney supportive care best practices will be reinforced by a collaborative learning approach among the dialysis center teams with monthly calls to share what each has learned about successful implementation; monthly quality metrics to track trends in supportive care best practices, allowing formative evaluation; and monthly calls with the Pathways quality-improvement advisor to discuss each site’s monthly reports and implementation change efforts, and to help them plan realistic incremental tests of change.

In selecting the best practices for implementation, and in designing the data-collection processes, we placed a premium on feasibility within existing dialysis center resources. Although it may be argued that all patients in a dialysis center would benefit from supportive care practices, it is easier to persuade busy clinicians to start with a smaller, high-priority subset of patients. This approach has been recommended by others for introducing goals-of-care discussions into the dialysis center (26,27). It addresses the major barrier of time limitations, which is often cited as a reason clinicians do not conduct advance care planning (26–28), and is consistent with change theories that recommend reducing barriers and friction that may impede adoption of a change (29).

A goal of a learning collaborative is to enable participants to adapt the change-package components to local conditions and culture; thus, implementation is not rigorously protocolized in the way that a clinical efficacy trial is conducted. Evaluation of multicomponent, complex interventions, such as Pathways, can be challenging (30). The evaluation is designed to capture a range of information to paint a full qualitative and quantitative picture of the experience of participants in the collaborative and the outcomes produced.

Our baseline data collection showed that the chart audit was feasible, but that it was very difficult to recruit patients who were seriously ill for the telephone survey. Chart audits were completed for 94% of patients who were seriously ill, with very little missing data. However, baseline telephone surveys were only completed for 18% of patients who were seriously ill. The main barriers were language (the survey was offered in English and Spanish, but not in other languages), cognitive limitations, and patients’ unwillingness to respond to phone calls. However, the patients who did complete the telephone survey at baseline were demographically similar to those patients who did not complete the survey, other than in regards to race and language. Future studies of participants who are seriously ill may need to consider approaches to increase response rates, such as face-to-face or on-dialysis interviews, or the use of substituted proxy reports.

A limitation to this study is the quasi-experimental, prepost design without a control group. Prepost designs are subject to several threats to internal validity, particularly secular trends. However, resource limitations and business considerations of the participating organizations made control groups infeasible. We expect that the mixed-methods design will provide rich qualitative information to supplement the trend data, thus strengthening the ability to assess whether secular trends played a minimal or strong role in the outcomes.

The TEP recommended that we measure the outcome of goal-concordant care, but no validated measure was available. Instead, we used surrogate markers of the process that are thought to influence, and lead to, achieving goal-concordant care. We created the KSC-IQ survey as a novel measure of kidney supportive care implementation. It was developed for this project on the basis of a review of the literature and expert review for face and content validity; it has not undergone psychometric testing. There are no comparisons or established norms for the KSC-IQ.

The Pathways change-package, best-practice recommendations are determined on the basis of a literature review and consensus of the TEP convened for the Pathways Project. Although we believe they accurately represent the state-of-the-art interventions with regard to kidney supportive care, they have not been subjected to an evidence-grading process, which would be difficult to do due to the lack of clinical trials in this area.

Very few studies have explicitly focused on enrolling patients seriously ill with kidney failure, and monitoring the outcomes that matter to these patients. Even fewer studies have focused on the implementation of supportive care practices. The Pathways Project is innovative because it will help to fill the knowledge gap of how to improve the quality of supportive care for patients seriously ill with kidney failure.

In conclusion, numerous national and international reports have documented the gaps in the quality of care for patients seriously ill with kidney failure, but there is, as yet, little guidance on the specific practices and implementation methods that will effectively address this gap. The Pathways Project will test whether a learning-collaborative approach can help to close this gap. We expect to learn valuable lessons about what fosters, and what impedes, the effort of dialysis centers to incorporate the Pathways intervention into their usual workflow processes to improve kidney supportive care for their patients.

Disclosures

D.E. Lupu reports receiving funded time from the Coalition for Supportive Care of Kidney Patients, and grant support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation for the Pathways Project and the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation for the My Way Project. A.H. Moss reports receiving funding from the George Washington University School of Nursing, which has grant support from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation for the Pathways Project, and grant support from the National Institutes of Health. All remaining authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This study and the Pathways Project are funded by Gordon E. and Betty I. Moore Foundation grants #5397, #8039, and #139736.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank all of the patients who consented to be interviewed and who participated in the Pathways Project. The authors gratefully acknowledge the superb technical assistance of Ms. Shari Sliwa and Mr. Payton Smith. We thank the following persons who oversaw the conduct of the Pathways Project at their respective dialysis centers: Mr. Steve Weiss (Atlantic Dialysis); Dr. Matthew Esson, Dr. Richard Fuquay, Ms. Ann Mooney, and Ms. Katie DiTomaso (ARA Denver area and ARA DeSoto); Dr. Nathaniel Berman, Dr. Andrew Bohmart, and Ms. Hilary Marion (Rogosin Institute); and Dr. Samir Patel and Dr. Sonika Pandey (Washington VA Medical Center). We also thank the West Virginia Clinical and Translational Science patient interviewers: Ms. Louise Moore, Ms. Elyse Krupp, and Ms. Dioconda Rollo. We thank Dr. Elizabeth Malcolm for contributions to scoping and designing the evaluation. We appreciate the contribution of VitalTalk faculty, Dr. Jane Schell and Dr. Robert Cohen, in a pilot training program. We are especially grateful for the leadership of Dr. Jill S. Lowery (Acting Chief, Ethics Policy, National Center for Ethics in Health Care, VA) who led the adaptation of the VA Goals of Care communication training for nephrology clinicians. Dr. Elizabeth Anderson and Dr. Christine Corbett contributed content on communication skills and medical management without dialysis to the learning sessions. For assistance in the literature review and development of the change package, the authors thank Ms. Andrea Moore, Dr. Janet Lynch, Dr. Joshua Nyyrenda, and Ms. Kelly Brooks of the Quality Insights Renal Network 5 and numerous volunteers from the Coalition for Supportive Care of Kidney Patients who prepared article summaries. The professional and patient participants on the TEP helped shape the change package, and we are thankful for their insights about how to improve care. For facilitation of the TEP, we thank Ms. Kelly McCutcheon Adams from the IHI. For funding this project, we thank the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

Author Contributions

A. Aldous, G. Harbert, L. Holdsworth, D. E. Lupu, M. Kurella Tamura, and A. H. Moss wrote the original draft; A. Aldous, L. Holdsworth, and M. Kurella Tamura were responsible for formal analysis; A. Aldous, L. Holdsworth, M. Kurella Tamura, D. E. Lupu, and A. H. Moss were responsible for data curation; G. Harbert, D. E. Lupu, A. H. Moss, A. Nicklas, and B. Vinson were responsible for project administration; L. Holdsworth, M. Kurella Tamura, D. E. Lupu, and A. H. Moss were responsible for investigation and methodology; L. Holdsworth, M. Kurella Tamura, D. E. Lupu, A. H. Moss, and B. Vinson were responsible for funding acquisition; D. E. Lupu and A. H. Moss conceptualized the study, were responsible for resources, and provided supervision; and all authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Supplemental Material

This article contains supplemental material online at http://kidney360.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.34067/KID.0005892020/-/DCSupplemental.

Literature search terms and strategy. Download Supplemental Material 1, PDF file, 1.12 MB (1.1MB, pdf)

Interview guide for interviews of implementation leaders. Download Supplemental Material 2, PDF file, 1.12 MB (1.1MB, pdf)

Questions for the Technical Expert Panel meeting. Download Supplemental Material 3, PDF file, 1.12 MB (1.1MB, pdf)

Pathways Project Change Package – 1-page summary. Download Supplemental Material 4, PDF file, 1.12 MB (1.1MB, pdf)

Ask-Tell-Ask card. Download Supplemental Material 5, PDF file, 1.12 MB (1.1MB, pdf)

Evaluation data collection and survey instruments: a. Chart audit instructions; b. Patient survey instrument; c. KSC-IQ staff survey; d. NOMAD adaptation. Download Supplemental Material 6, PDF file, 1.12 MB (1.1MB, pdf)

References

- 1.Kurella Tamura M, O’Hare AM, Lin E, Holdsworth LM, Malcolm E, Moss AH: Palliative care disincentives in CKD: Changing policy to improve CKD care. Am J Kidney Dis 71: 866–873, 2018. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.12.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown L, Gardner G, Bonner A: A comparison of treatment options for management of end stage kidney disease in elderly patients: A systematic review. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep 11: 197–208, 2013. 10.11124/jbisrir-2014-1152 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wachterman MW, Pilver C, Smith D, Ersek M, Lipsitz SR, Keating NL: Quality of end-of-life care provided to patients with different serious illnesses. JAMA Intern Med 176: 1095–1102, 2016. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.1200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lupu D, Nyirenda J; Coalition for Supportive Care of Kidney Patients (CSCKP): Creating kidney supportive care programs: Lessons learned around the world, 2018. Available at: https://go.gwu.edu/creatingkidneysupportivecareprograms. Accessed September 29, 2020

- 5.Institute for Healthcare Improvement: The breakthrough series: IHI’s collaborative model for achieving breakthrough improvement. Boston, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nix M, McNamara P, Genevro J, Vargas N, Mistry K, Fournier A, Shofer M, Lomotan E, Miller T, Ricciardi R, Bierman AS: Learning collaboratives: Insights and a new taxonomy from AHRQ’s two decades of experience. Health Aff (Millwood) 37: 205–212, 2018. 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells S, Tamir O, Gray J, Naidoo D, Bekhit M, Goldmann D: Are quality improvement collaboratives effective? A systematic review. BMJ Qual Saf 27: 226–240, 2018. 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ØVretveit J, Bate P, Cleary P, Cretin S, Gustafson D, McInnes K, McLeod H, Molfenter T, Plsek P, Robert G, Shortell S, Wilson T: Quality collaboratives: Lessons from research. Qual Saf Health Care 11: 345–351, 2002. 10.1136/qhc.11.4.345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Improving Chronic Illness Care: Change package: Improving chronic illness care. Available at: http://www.improvingchroniccare.org/index.php?p=Change_Package&s=386. Accessed September 29, 2020

- 10.Institute for Healthcare Improvement: Science of improvement: Spreading changes. Boston, Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Available at: http://www.ihi.org:80/resources/Pages/HowtoImprove/ScienceofImprovementSpreadingChanges.aspx. Accessed September 29, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renal Physician’s Association: Shared decision-making in the appropriate initiation of and withdrawal from dialysis: Clinical practice guideline. Rockville, MD, Renal Physician’s Association, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davison SN, Levin A, Moss AH, Jha V, Brown EA, Brennan F, Murtagh FEM, Naicker S, Germain MJ, O’Donoghue DJ, Morton RL, Obrador GT; Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes: Executive summary of the KDIGO Controversies conference on supportive care in chronic kidney disease: Developing a roadmap to improving quality care. Kidney Int 88: 447–459, 2015. 10.1038/ki.2015.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nembhard IM: Learning and improving in quality improvement collaboratives: Which collaborative features do participants value most? Health Serv Res 44: 359–378, 2009. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00923.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for Ethics in Health Care: Goals of care conversations skills training for physicians, advance practice nurses, and physician assistants. Washington DC, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for Ethics in Health Care, 2019. Available at: https://www.ethics.va.gov/goalsofcaretraining/practitioner.asp. Accessed October 29, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 15.VitalTalk . Available at: http://www.vitaltalk.org/. Accessed September 29, 2020

- 16.Lupu D, Moss A; Using “Ask-Tell-Ask” in person-centered care: Promoting goals of care conversations with dialysis patients and their families during COVID-19. Supportive strategies for kidney care community during COVID-19: Communication series. Coalition for Supportive Care of Kidney Patients. Available at: http://go.gwu.edu/GOCconversations. Accessed October 1, 2020

- 17.Curran GM, Bauer M, Mittman B, Pyne JM, Stetler C: Effectiveness-implementation hybrid designs: Combining elements of clinical effectiveness and implementation research to enhance public health impact. Med Care 50: 217–226, 2012. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182408812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engelberg R, Downey L, Curtis JR: Psychometric characteristics of a quality of communication questionnaire assessing communication about end-of-life care. J Palliat Med 9: 1086–1098, 2006. 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halpern SD: Goal-concordant care — searching for the holy grail. N Engl J Med 381: 1603–1606, 2019. 10.1056/NEJMp1908153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanders JJ, Curtis JR, Tulsky JA: Achieving goal-concordant care: A conceptual model and approach to measuring serious illness communication and its impact. J Palliat Med 21: S17–S27, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Turnbull AE, Hartog CS: Goal-concordant care in the ICU: A conceptual framework for future research. Intensive Care Med 43: 1847–1849, 2017. 10.1007/s00134-017-4873-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moss AH, Ganjoo J, Sharma S, Gansor J, Senft S, Weaner B, Dalton C, MacKay K, Pellegrino B, Anantharaman P, Schmidt R: Utility of the “surprise” question to identify dialysis patients with high mortality. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 3: 1379–1384, 2008. 10.2215/CJN.00940208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White N, Kupeli N, Vickerstaff V, Stone P: How accurate is the ‘surprise question’ at identifying patients at the end of life? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med 15: 139, 2017. 10.1186/s12916-017-0907-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coryn CLS, Hobson KA: Using nonequivalent dependent variables to reduce internal validity threats in quasi-experiments: Rationale, history, and examples from practice. New Dir Eval 2011: 31–39, 2011. 10.1002/ev.375 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, Hovmand P, Aarons G, Bunger A, Griffey R, Hensley M: Outcomes for implementation research: Conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health 38: 65–76, 2011. 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mandel EI, Bernacki RE, Block SD: Serious illness conversations in ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 854–863, 2017. 10.2215/CJN.05760516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goff SL, Unruh ML, Klingensmith J, Eneanya ND, Garvey C, Germain MJ, Cohen LM: Advance care planning with patients on hemodialysis: An implementation study. BMC Palliat Care 18: 64, 2019. 10.1186/s12904-019-0437-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luckett T, Sellars M, Tieman J, Pollock CA, Silvester W, Butow PN, Detering KM, Brennan F, Clayton JM: Advance care planning for adults with CKD: A systematic integrative review. Am J Kidney Dis 63: 761–770, 2014. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kotter JP, Schlesinger LA: Choosing strategies for change. Harv Bus Rev 57: 106–114, 1979 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nadeem E, Olin SS, Hill LC, Hoagwood KE, Horwitz SM: Understanding the components of quality improvement collaboratives: A systematic literature review. Milbank Q 91: 354–394, 2013. 10.1111/milq.12016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sudore RL, Heyland DK, Barnes DE, Howard M, Fassbender K, Robinson CA, Boscardin J, You JJ: Measuring advance care planning: Optimizing the advance care planning engagement survey. J Pain Symptom Manage 53: 669–681.e8, 2017. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.10.367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gramling R, Stanek S, Ladwig S, Gajary-Coots E, Cimino J, Anderson W, Norton SA, Aslakson RA, Ast K, Elk R, Garner KK, Gramling R, Grudzen C, Kamal AH, Lamba S, LeBlanc TW, Rhodes RL, Roeland E, Schulman-Green D, Unroe KT; AAHPM Research Committee Writing Group: Feeling heard and understood: A patient-reported quality measure for the inpatient palliative care setting. J Pain Symptom Manage 51: 150–154, 2016. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barr PJ, Thompson R, Walsh T, Grande SW, Ozanne EM, Elwyn G: The psychometric properties of CollaboRATE: A fast and frugal patient-reported measure of the shared decision-making process [published correction appears in J Med Internet Res 17: e32, 2015 10.2196/jmir.4272]. J Med Internet Res 16: e2, 2014. 10.2196/jmir.3085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.May C, Rapley T, Mair FS, Treweek S, Murray E, Ballini L, Macfarlane A, Girling M, Finch TL: Normalization process theory on-line users’ manual, toolkit and NoMAD instrument, 2015. Available at: http://www.normalizationprocess.org. Accessed August 18, 2018

- 35.Institute for Healthcare Improvement: IHI Assessment Scale for Collaboratives. Boston, Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/AssessmentScaleforCollaboratives.aspx. Accessed August 14, 2018 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Literature search terms and strategy. Download Supplemental Material 1, PDF file, 1.12 MB (1.1MB, pdf)

Interview guide for interviews of implementation leaders. Download Supplemental Material 2, PDF file, 1.12 MB (1.1MB, pdf)

Questions for the Technical Expert Panel meeting. Download Supplemental Material 3, PDF file, 1.12 MB (1.1MB, pdf)

Pathways Project Change Package – 1-page summary. Download Supplemental Material 4, PDF file, 1.12 MB (1.1MB, pdf)

Ask-Tell-Ask card. Download Supplemental Material 5, PDF file, 1.12 MB (1.1MB, pdf)

Evaluation data collection and survey instruments: a. Chart audit instructions; b. Patient survey instrument; c. KSC-IQ staff survey; d. NOMAD adaptation. Download Supplemental Material 6, PDF file, 1.12 MB (1.1MB, pdf)