Abstract

Background

Ministries of health, donors, and other decision‐makers are exploring how they can use mobile technologies to acquire accurate and timely statistics on births and deaths. These stakeholders have called for evidence‐based guidance on this topic. This review was carried out to support World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening.

Objectives

Primary objective: To assess the effects of birth notification and death notification via a mobile device, compared to standard practice.

Secondary objectives: To describe the range of strategies used to implement birth and death notification via mobile devices and identify factors influencing the implementation of birth and death notification via mobile devices.

Search methods

We searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, the Global Health Library, and POPLINE (August 2, 2019). We searched two trial registries (August 2, 2019). We also searched Epistemonikos for related systematic reviews and potentially eligible primary studies (August 27, 2019). We conducted a grey literature search using mHealthevidence.org (August 15, 2017) and issued a call for papers through popular digital health communities of practice. Finally, we conducted citation searches of included studies in Web of Science and Google Scholar (May 15, 2020). We searched for studies published after 2000 in any language.

Selection criteria

For the primary objective, we included individual and cluster‐randomised trials; cross‐over and stepped‐wedge study designs; controlled before‐after studies, provided they have at least two intervention sites and two control sites; and interrupted time series studies. For the secondary objectives, we included any study design, either quantitative, qualitative, or descriptive, that aimed to describe current strategies for birth and death notification via mobile devices; or to explore factors that influence the implementation of these strategies, including studies of acceptability or feasibility.

For the primary objective, we included studies that compared birth and death notification via mobile devices with standard practice. For the secondary objectives, we included studies of birth and death notification via mobile device as long as we could extract data relevant to our secondary objectives.

We included studies of all cadres of healthcare providers, including lay health workers; administrative, managerial, and supervisory staff; focal individuals at the village or community level; children whose births were being notified and their parents/caregivers; and individuals whose deaths were being notified and their relatives/caregivers.

Data collection and analysis

For the primary objective, two authors independently screened all records, extracted data from the included studies and assessed risk of bias. For the analyses of the primary objective, we reported means and proportions, where appropriate. We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach to assess the certainty of the evidence and we prepared a 'Summary of Findings' table.

For the secondary objectives, two authors screened all records, one author extracted data from the included studies and assessed methodological limitations using the WEIRD tool and a second author checked the data and assessments. We carried out a framework analysis using the Supporting the Use of Research Evidence (SURE) framework to identify themes in the data. We used the GRADE‐CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research) approach to assess our confidence in the evidence and we prepared a 'Summary of Qualitative Findings' table.

Main results

For the primary objective, we included one study, which used a controlled before‐after study design. The study was conducted in Lao People’s Democratic Republic and assessed the effect of using mobile devices for birth notification on outcomes related to coverage and timeliness of Hepatitis B vaccination. However, we are uncertain of the effect of this approach on these outcomes because the certainty of this evidence was assessed as very low. The included study did not assess resource use or unintended consequences. For the primary objective, we did not identify any studies using mobile devices for death notification.

For the secondary objective, we included 21 studies. All studies were conducted in low‐ or middle‐income settings. They focussed on identification of births and deaths in rural, remote, or marginalised populations who are typically under‐represented in civil registration processes or traditionally seen as having poor access to health services.

The review identified several factors that could influence the implementation of birth‐death notification via mobile device. These factors were tied to the health system, the person responsible for notifying, the community and families; and include:

‐ Geographic barriers that could prevent people’s access to birth‐death notification and post‐notification services

‐ Access to health workers and other notifiers with enough training, supervision, support, and incentives

‐ Monitoring systems that ensure the quality and timeliness of the birth and death data

‐ Legal frameworks that allow births and deaths to be notified by mobile device and by different types of notifiers

‐ Community awareness of the need to register births and deaths

‐ Socio‐cultural norms around birth and death

‐ Government commitment

‐ Cost to the system, to health workers and to families

‐ Access to electricity and network connectivity, and compatibility with existing systems

‐ Systems that protect data confidentiality

We have low to moderate confidence in these findings. This was mainly because of concerns about methodological limitations and data adequacy.

Authors' conclusions

We need more, well‐designed studies of the effect of birth and death notification via mobile devices and on factors that may influence its implementation.

Keywords: Humans; Bias; Birth Certificates; Computers, Handheld; Controlled Before-After Studies; Death Certificates; Health Services Accessibility; Rural Population; Time Factors

Plain language summary

Birth and death notification via mobile devices: a mixed methods review

What is the aim of this review?

In this Cochrane Review, we aimed to assess the effect of using mobile devices to notify births and deaths. We also aimed to describe how these mobile solutions are being used in practice and the factors that influence their use. We collected and analysed all relevant studies to answer these questions.

Key messages

We know very little about the effects of using mobile devices to notify births and deaths. Factors that can influence the implementation of this approach include factors tied to the health system and the notification system, the person responsible for notifying, the community, and the families involved.

What was studied in the review?

By registering notified births and deaths, governments can track the health of their population, identify needs and problems, and design better services. In many countries, births and deaths are not properly registered. Sometimes this is because government systems are poorly designed to facilitate registration, government workers do not have proper training, people live far from government services, or are not aware of the need to register births or deaths. In many cases, registration is affected by delays in or lack of birth or death notification.

Governments are starting to use mobile devices such as mobile phones to reduce problems with birth or death notification. In some settings, members of the public, healthcare workers and others use mobile phones to notify a birth or death to the health system or to a central registration system.

The main aim of our review was to assess what happens when people use mobile devices to notify births and deaths, compared to other systems or no systems at all. For instance, do they register more birth and deaths, and do they do this at the right time? And does this lead more babies and children to use or receive health services, such as immunisation? We also wanted to find out how people are using these mobile systems in practice and what influences their use.

What are the main results of the review?

We found 21 relevant studies. All of the studies were from low‐ or middle‐income countries. Most of these studies focussed on the notification of births and deaths in rural, remote, or marginalised populations who are often under‐represented in birth or death registration processes or have poor access to health services. Only one of the studies assessed the effect of using mobile devices for notification systems. This study focussed on birth notification. We did not find any studies that assessed the effect of using mobile devices for death notification. We are uncertain of the effect of this approach on the number of births and deaths that are properly notified because the certainty of this evidence was assessed as very low.

The other studies had information about how people use the mobile device‐based birth and death notification systems in practice. These studies pointed to several factors that could influence the implementation of birth‐death notification via mobile devices. These factors were tied to the health system and the notification system, the person responsible for notifying, the community, and the families involved. They include:

‐ Geographic barriers that could prevent people’s access to birth‐death notification and post‐notification services

‐ Access to health workers and other notifiers with enough training, supervision, support, and incentives

‐ Monitoring systems that ensure the quality and timeliness of the birth and death data

‐ Legal frameworks that allow births and deaths to be notified by mobile device and by different types of notifiers

‐ Community awareness of the need to register births and deaths

‐ Socio‐cultural norms around birth and death

‐ Government commitment

‐ Cost to the system, to health workers and to families

‐ Access to electricity and network connectivity, and compatibility with existing systems

‐ Systems that protect data confidentiality

We have low to moderate confidence in these findings. This was mainly because of the ways in which the studies were designed and small amounts of data.

How up‐to‐date is this review?

We searched for studies that had been published up to August 2, 2019.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Primary objective: Summary of findings.

| Birth notification via mobile device compared to standard practice | ||||

|

Patient or population: Health Care Workers (HCWs), Village Health Volunteers (VHVs), newborn children Setting: Lao People’s Democratic Republic Intervention: Provision of mobile phone and credit to HCWs and VHVs to facilitate birth notification Comparison: Standard practice, i.e. no provision of mobile phone or credit to HCWs and VHVs to facilitate birth notification | ||||

| Outcomes | Birth notification via mobile phone versus standard practice | No of Participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | What happens? |

| Coverage of birth notification | ||||

| Proportion of VHVs who reported notifying a HCW about deliveries or births using mobile phones (post‐intervention comparison) | 12% more VHVs in the intervention group reported notifying a HCW using mobile phones compared to the comparison group | 101 (1 CBA)1 |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,3,4 | We are uncertain of the effect of the intervention on coverage of birth notification because the certainty of the evidence is very low. |

| Proportion of HCWs who reported receiving a notification from VHV about deliveries or birth using mobile phones (post‐intervention comparison) | 38% more HCWs in the intervention group reported receiving a notification using mobile phones compared to the comparison group | 30 (1 CBA)1 |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,3,4 | |

| Timeliness of birth notification | ||||

| Proportion of VHVs who reported notifying HCWs either during labour or within 1 day of birth using mobile phones | 18% moreVHVs in the intervention group reported notifying HCWs of imminent deliveries within 1 day of birth via mobile phones compared to the comparison group | 101 (1 CBA)1 |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,3,4 | We are uncertain of the effect of the intervention on the timeliness of birth notification because the certainty of the evidence is very low. |

| Proportion of HCWs who reported receiving a notification from VHV about imminent deliveries or within 1 day of birth using mobile phones | 15% moreHCWs in the intervention group reported being notified by VHVs of imminent deliveries within 1 day of birth via mobile phones compared to the comparison group | 30 (1 CBA)1 |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,3,4 | |

| Proportion and timeliness of legal birth registrations | ||||

| No studies were identified that reported on this outcome. | ||||

| Coverage of newborn or child health services | ||||

| Proportion of births where HCW made postnatal care visit to home | There were 10% more postnatal care home visits by HCW in the intervention group compared to the comparison group. | 1339 (1 CBA)1 |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,3,4 | We are uncertain of the effect of the intervention on coverage of newborn or child health services because the certainty of the evidence is very low |

| Proportion of births for which Hepatitis B birth dose vaccination was provided within 30 days | There were 23% more children who received the Hepatitis B birth dose vaccination within 30 days of birth in the intervention group compared to the comparison group | 1525 (1 CBA)1 |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,3,4 | |

| Timeliness of newborn or child health services | ||||

| Proportion of births where Hepatitis B birth dose vaccination was administered within 0‐1 day | There was a 0% change in the number of newborns receiving Hepatitis B birth dose vaccination within the first day after birth in the intervention group compared to comparison group. | 1525 (1 CBA)1 |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,3,4 | We are uncertain of the effect of the intervention on timeliness of newborn or child health services because the certainty of the evidence is very low |

| Proportion of births where Hepatitis B birth dose vaccination was administered within 2‐7 days | 5% fewer children received Hepatitis B birth dose vaccination between days 2 and 7 in the intervention group compared to the comparison group. | 1525 (1 CBA)1 |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,3,4 | |

| Proportion of births where the HCW made a postnatal care home visit within 24 hours of notification | 18% fewer children received a postnatal care visit at least 50% of the time by the HCW in the intervention group within 24 hours of birth compared to the comparison group. | 30 (1 CBA)1 |

⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2,3,4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk Ratio; CBA: Controlled Before‐After study; VHV: Village Health Volunteer; HCW: Health Care Worker | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence

High = This research provides a very good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different† is low.

Moderate = This research provides a good indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different† is moderate. Low = This research provides some indication of the likely effect. However, the likelihood that it will be substantially different† is high. Very low = This research does not provide a reliable indication of the likely effect. The likelihood that the effect will be substantially different† is very high. † Substantially different = a large enough difference that it might affect a decision | ||||

Explanations for certainty rating:

2 Initial rating of low certainty assigned due to non‐randomised study design, resulting in high or unclear risk of bias

3 The initial rating was downgraded one level to very low certainty for outcomes related to the coverage and timeliness of birth notification due to small sample sizes and small numbers of events.

4 The initial rating was downgraded one level to very low certainty for outcomes related to the coverage and timeliness of post‐notification health services due to concerns related to indirectness. It is unclear how many of the post‐notification service events were directly in response to the notification.

Abbreviations:

VHV, Village Heath Volunteer; HCW, Health Care Worker.

Summary of findings 2. Secondary objectives: Summary of qualitative findings.

| Summary of review finding | Studies contributing to the review finding | Overall GRADE‐CERQual assessment of confidence in the evidence | Explanation for assessment | ||

| A. Health system constraints in the implementation of birth and death notification via mobile devices | |||||

| A.1 | Geographic barriers hamper timeliness of birth and death notification conducted via mobile devices, as well as post‐notification services or processes (e.g. certification of birth or death). | Xeuatvongsa 2016; ANISA 2016; Pascoe 2012; MOVE‐IT 2013; Ngabo 2012; MBRT 2016, mVRS 2017 | Moderate confidence | Serious concerns related to methodological limitations. Few or no concerns related to coherence, relevance and adequacy | |

| A.2 | Birth and death data collected using mobile devices can help health and civil registration systems identify problems and introduce appropriate quality improvements. | Moshabela 2015; MBRT 2016; RapidSMS 2012; MVH 2017; NIMDS 2019 | Low confidence | Serious concerns related to methodological limitations and adequacy. Few or no concerns with coherence and relevance | |

| A.3 | Health workers who lack familiarity with, or prior experience in, using mobile technologies may need rigorous training as well as post‐training support. |

Andreatta 2011; Gisore 2012; Ngabo 2012; mSIMU 2017; Yugi 2016 mTika 2016; Xeuatvongsa 2016; MBRT 2016; Van Dam 2015; MBRL 2011; MOVE‐IT 2013; NIMDS 2019 |

Moderate confidence | Moderate concerns related to methodological limitations. Few or no concerns related to coherence, relevance, and adequacy | |

| A.4 | Local capacity to train future cadres of notifiers may be strengthened though 'train the trainer' approaches. | Ngabo 2012; MBRL 2011 |

Low confidence |

Serious concerns related to methodological limitations and adequacy. Few or no concerns with coherence and relevance | |

| A.5 | Mechanisms for continuous monitoring and supportive supervision are important for ensuring the quality and timeliness of birth and death data collected via mobile devices. | Andreatta 2011; mTika 2016; Ngabo 2012; MOVE‐IT 2013; Yugi 2016; Pascoe 2012 | Moderate confidence | Moderate concerns related to methodological limitations and adequacy. Few or no concerns with coherence and relevance | |

| A.6 | Inadequate attention is paid to legal frameworks governing civil registration. These may need to be modified to allow notification via mobile device and the inclusion of new cadres of notifiers (low confidence finding). |

eCRVS‐Mozambique 2017; mVRS 2017; MBRP 2015 | Low confidence | Serious concerns related to methodological limitations and adequacy. Few or no concerns with coherence and relevance | |

| A.7 | The availability of adequate human resources to conduct birth and death notification via mobile devices may be facilitated by hiring new cadres of notifiers or recruiting existing cadres of health workers to undertake notification. | Andreatta 2011; MBRL 2011; Gisore 2012; Pascoe 2012; MOVE‐IT 2013; Xeuatvongsa 2016; Yugi 2016; ANISA 2016; mVRS 2017; eCRVS‐Mozambique 2017; MBRT 2016 | Moderate confidence | Serious concerns related to methodological limitations. Few or no concerns with coherence, relevance, and adequacy | |

| A.8 | Implementing birth and death notification via mobile devices may be influenced by underlying health and civil registration system infrastructure, resources, and processes. | Ngabo 2012; MBRL 2011; MOVE‐IT 2013; Moshabela 2015; ANISA 2016; mVRS 2017; Gisore 2012;MVH 2017 | Low confidence | Serious concerns related to methodological limitations. Minor concerns related to adequacy. Few or no concerns with coherence, and relevance | |

| B. Factors related to individuals providing birth and death notification via mobile devices | |||||

| B.1 | Costs incurred by health workers sending notification using personal mobile phones may need to be reimbursed to facilitate sustained use of these technologies for notification. | Ngabo 2012; Pascoe 2012; mSIMU 2017; Yugi 2016; Xeuatvongsa 2016; Gisore 2012 | Moderate confidence | Moderate concerns related to methodological limitations and adequacy. Few or no concerns related to coherence or relevance | |

| B.2 | The use of mobile phones for notification is acceptable to health workers, and helps them to undertake their job responsibilities. | Ngabo 2012; Pascoe 2012; mSIMU 2017, Van Dam 2015; Yugi 2016; NIMDS 2019 | Moderate confidence | Moderate concerns related to methodological limitations and adequacy. Few or no concerns related to coherence and relevance | |

| B.3 | Health workers’ adoption of mobile birth and death notification strategies may be affected by competing priorities and the availability of adequate incentives. | MOVE‐IT 2013; mSIMU 2017; mTika 2016; MVH 2017 | Moderate confidence | Minor concerns related to methodological limitations. Serious concerns related to adequacy. Few or no concerns related to coherence and relevance | |

| C. Factors related to families for whom birth and death is notified via mobile devices | |||||

| C.1 | For some families, costs may be a barrier to completing birth and death registration post‐notification. | MOVE‐IT 2013, MBRP 2015, MBRT 2016 | Low confidence | Serious concerns related to methodological limitations and adequacy. Few or no concerns related to coherence, relevance, and adequacy | |

| C.2 | There may be a need for targeted demand generation activities in communities with low awareness of the need of birth and death registration, alongside the use of mobile phones for birth and death notification. | MOVE‐IT 2013; MBRG 2014; mVRS 2017; MBRT 2016; | Low confidence | Serious concerns related to methodological limitations. Moderate concerns related to adequacy. Few or no concerns related to coherence and relevance | |

| C.3. | Sociocultural norms may influence the timely identification of births and deaths, and should be taken into consideration when developing mobile phone interventions for notification. | MOVE‐IT 2013; MBRG 2014; MBRP 2015; ANISA 2016 | Low confidence | Serious concerns related to methodological limitations and adequacy. Few or no concerns related to coherence and relevance | |

| C.4 | Birth and death notification may increase access to these services for some families. However, they may also increase inequities in access related to low availability of supportive infrastructure (network coverage, roads, human resources), human factors (age, gender, literacy, poverty), and selective funding priorities of donors. |

Gisore 2012; MBRP 2015; MBRT 2016; Andreatta 2011; Ngabo 2012; MOVE‐IT 2013; mSIMU 2017; mTika 2016; Yugi 2016; Xeuatvongsa 2016; mVRS 2017 |

Moderate confidence | Serious concerns related to methodological limitations. Few or no concerns related to coherence, relevance, and adequacy | |

| D. Factors related to government involvement in birth and death notification via mobile devices | |||||

| D.1 | Strong government commitment is a key factor in the successful implementation of birth and death notification via mobile devices. | MBRL 2011; Ngabo 2012; Yugi 2016; mVRS 2017; eCRVS‐Mozambique 2017; MBRT 2016; MBRP 2015 | Low confidence | Serious concerns related to methodological limitations. Moderate concerns related to adequacy. Few or no concerns related to coherence or relevance | |

| E. Factors related to technologies used for birth and death notification via mobile devices | |||||

| E.1 | Cost is an important consideration in the purchase, set‐up, and scaling up of mobile technologies needed for birth and death notification. |

Ngabo 2012; Xeuatvongsa 2016; Gisore 2012; mTika 2016; Pascoe 2012; Van Dam 2015; Yugi 2016; mVRS 2017 |

Low confidence | Serious concerns related to methodological concerns. Moderate concerns related to adequacy. Few or no concerns related to coherence and relevance | |

| E.2 | Challenges when notifying births and deaths via mobile devices include poor access to electricity and incompatibility with existing systems. |

Ngabo 2012; MBRL 2011; Pascoe 2012; Gisore 2012; MBRP 2015; MBRT 2016 |

Low confidence | Serious concerns related to methodological concerns. Moderate concerns related to adequacy. Few or no concerns related to coherence and relevance | |

| E.3 | The availability of network connectivity is a key factor in the successful implementation and scale‐up of birth and death notification via mobile devices. | Ngabo 2012; Pascoe 2012; Yugi 2016; ANISA 2016; mSIMU 2017; mVRS 2017; MBRT 2016, | Moderate confidence | Serious concerns related to methodological limitations. Few or no concerns with coherence, relevance, and adequacy | |

| E.4 | Data security and encryption measures are needed to preserve confidentiality of birth and death information notified via mobile devices. |

Van Dam 2015; MBRT 2016; Ngabo 2012; MVH 2017 |

Low confidence | Serious concerns with methodological limitations and adequacy. Few or no concerns with coherence and relevance | |

Background

Globally, the birth of nearly 230 million children under the age of five, and two‐thirds of all deaths have not been officially registered (UNICEF 2016; WHO 2017a; World Bank 2014). Birth registration is a child’s right, and serves as the foundation for establishing legal identity, equitable access to basic services such as healthcare and education, and protection from exploitation (UNHCR & UNICEF 2017; UNICEF 2013). Similarly, death registration, including identification of cause of death, enables public health systems to develop and implement programmes to improve the health of populations, as well as rapidly deal with outbreaks (WHO 2013a; WHO 2017a; World Bank 2014). In the context of the post‐2015 development agenda, timely, accurate, and complete statistics on births and deaths, gained through the act of registration, are fundamental for tracking progress towards sustainable development goals and achievement of universal health coverage (WHO 2017b).

Description of the condition

Well‐functioning Civil Registration and Vital Statistics systems provide the most reliable and up‐to‐date data on births, deaths, and population size (UN‐DECA 2014). Civil registration is defined as the "'universal, continuous, permanent, and compulsory recording of vital events (live births, deaths, fetal deaths, marriages, and divorces) provided through decree or regulation in accordance with the legal requirements of each country" (UN‐DECA 2002; UNHCR & UNICEF 2017). Vital statistics are the compilation, processing, and dissemination of civil registration data in statistical form (Setel 2007; UN‐DECA 2014; UN‐DECA 2017). Statistics on births and deaths are used to generate population health indicators (e.g. fertility rate, birth rate, and life expectancy), data on mortality (e.g. maternal and infant mortality rates), and disease burden (e.g. using details of cause of death (UN‐DECA 2014)). Hence, birth and death statistics are a valuable source of data for policymakers, to guide the development of global, national, and regional health policy, programme planning, and appropriate resource‐allocation (Setel 2007; UN‐DECA 2014).

Over 100 developing countries lack functional or adequate civil registration systems for capturing vital events (World Bank 2014). The majority of individuals missed by civil registration systems reside in South Asia and sub‐Saharan Africa (AbouZahr 2015; Setel 2007; UNICEF 2016). Birth and deaths of individuals living in rural areas, or lower socioeconomic status households, are more likely to be unregistered, compared to their urban and wealthier counterparts (UNICEF 2013). There is also a link between birth registration and health outcomes (Phillips 2015). For example, children who are unregistered are more likely to miss out on essential health services, such as immunisations (Apland 2014; Fagernas 2013). Lack of accurate and timely death statistics, including cause of death, leads to weak disease surveillance, and threatens the ability of public health systems to prevent or rapidly deal with outbreaks (UN‐DECA 2017). From the health system perspective, the paucity of accurate statistics on births and deaths poses a key challenge in the estimation of programme needs (e.g. number of children eligible for health services), appropriate resource allocation, and monitoring (e.g. for calculation of indicators of health system coverage or performance (AbouZahr 2015; AbouZahr 2015a; Mahapatra 2007)).

Several challenges to civil registration have been identified in the literature, including geographic barriers (UNICEF 2013), low demand or lack of incentives for registration (Apland 2014; UNICEF 2013; WHO 2013b; World Bank 2014), use of paper‐based systems for reporting and recording births (Oomman 2013; World Bank 2014), and lack of, or incorrect, cause of death coding and documentation (Mikkelsen 2015; Rampatige 2013). Poor integration of Civil Registration and Vital Statistics systems with other government or citizen databases leads to missed opportunities, for instance, where data on births and deaths captured by the health system are not linked to civil registration systems (World Bank 2014). Even when integration between the health and civil registration system may exist, home births or deaths may not be reported where formal community‐level notification processes are deficient (World Bank 2014).

A global scale‐up plan for strengthening civil registration systems has been developed by the World Health Organization and the World Bank, with the aim to "achieve universal civil registration of births, deaths, and other vital events, including reporting cause of death, and access to legal proof of registration for all individuals by 2030” (World Bank 2014). A cornerstone of this plan is the prioritisation and strengthening of the linkages between health and Civil Registration and Vital Statistics systems (Muzzi 2010; WHO 2013a; World Bank 2014). This includes a push to modernise data systems associated with civil registration through the use of digital information systems, and to improve coverage of registration services among underserved populations such as those residing in rural areas (Oomman 2013; World Bank 2014). In these respects, the global proliferation of mobile phones and cellular network connectivity is increasingly being leveraged, especially in resource‐limited settings, to drive development and use of digital civil registration applications (ITU 2016; Labrique 2012; Labrique 2013; Oomman 2013). Official notifiers include health workers or other cadres of workers permitted under law to carry out notifications. With growing access to mobile phones, community‐based individuals, such as vaccination programme workers, community health workers, and village elders can serve as 'notifiers', helping to increase the reach of civil registration systems to underserved rural and remote regions (World Bank 2014). Such an approach may help to reduce delays in identification and reporting of births and deaths to health systems, local civil registration authorities, or both (World Bank 2014).

Description of the intervention

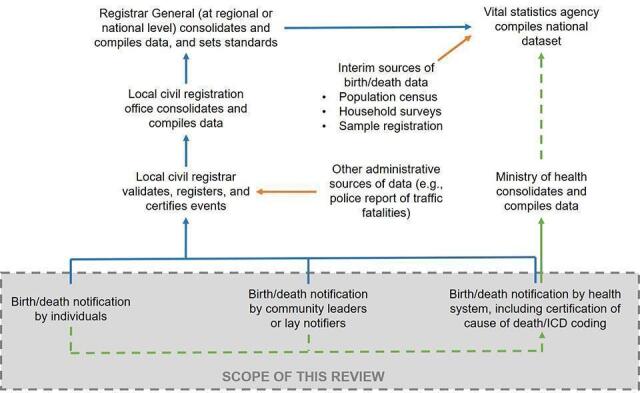

Civil registration involves four major activities: recording, notification, registration, and certification (see Figure 1 (Setel 2007; WHO 2013a)).

1.

Linkage between CRVS and health system Adapted fromSetel 2007and World Bank and World Health Organization 2014 (World Bank 2014).

Recording entails capturing details related to a vital event at the point of the event. For example, details of a birth may be recorded on a paper form at the health facility or at home.

This is followed by notification, wherein details of the recorded event are communicated to the local civil registration office by lawful notifiers. In official terms, a notification is defined as the capture and onward transmission of minimum essential information on the fact of birth or death by a designated informant, agent or official of the CRVS system using a CRVS authorised notification form (paper or electronic) with that transmission of information being sufficient to support eventual registration and certification of the vital event.

Upon receiving a notification, the civil registrar registers the event, by verifying event details, and recording them in a civil register.

Subsequently, a legally valid certificate of registration is issued. The certificate serves as proof that the birth or death has been registered in a civil register.

Registered events are aggregated by the national authorities to produce vital statistics on key health and development indicators.

Since notification is the key step that triggers registration, many strategies to improve the coverage and timeliness of birth or death registration are focussed on reducing delays in notification, especially by using mobile devices to notify local officials. The scope of this review is limited to the notification of births and deaths conducted via mobile devices.

-

By birth notification, we mean the transmission of information via a mobile device to a centralised system or focal individual(s) to report a birth event.

In addition to the formal notification process, which leads to birth registration as it occurs within the context of Civil Registration and Vital Statistics systems, we included informal notification of births in this definition. By this, we mean that individuals, other than those defined under the law as official notifiers, may be involved in notifying with mobile devices. It may also mean that the notification is directed to focal individuals other than the civil registrar, or communicated directly to a digital system, and transmitted for purposes other than civil registration.

-

By death notification, we mean the transmission of information via a mobile device to a centralised system or focal individual(s) to report a death event. Death notification may include information on the cause of death.

As in the case of birth notification, we also included informal notifications of death in this definition. By this, we mean that individuals, other than those defined under the law as official notifiers, may be involved in providing a notification. It may also mean that the notification is directed to focal individuals other than the civil registrar, or communicated directly to a digital system, and may be transmitted for purposes other than civil registration.

By mobile devices, we mean mobile phones of any kind (but not analogue land line telephones), as well as tablets, personal digital assistants, and smartphones. Laptops are not included in this list.

How the intervention might work

For birth notifications, information related to the birth may be transmitted via mobile phones as phone calls, inputs to an interactive voice response, or an unstructured supplementary service data (USSD) system, as short messaging service (SMS), from mobile device‐based applications (apps), or to publicly known short codes or access numbers. The content of the birth notification may vary by country or implementation, but may include the name of the child born, name and address of the parents, place and date of birth, and details of birth outcomes.

An example of a formal birth notification sent via a mobile device, is when a community‐based notifier uses his or her mobile phone to relay notification about a home‐based birth to a digital civil registration system via USSD (NIRA 2017). The notification may be received and reviewed for accuracy and completeness by the local civil registration office before a birth certificate is issued. Direct notification to the civil registrar by lawful notifiers is considered an active notification. Passive notification occurs in cases where a notification form is provided by health authorities to families and when family members bear the onus of reporting the birth or death event to the civil registrar.

An example of an informal birth notification sent via a mobile device, is when a village elder sends information about a birth, via SMS, to a central digital server, for the purpose of enroling the child in a longitudinal vaccination tracking system. The enrolment of the child in the tracking system may be used to initiate vaccination services for the child, and to track their subsequent vaccinations.

For death notifications, information related to the death may be transmitted via mobile phones as phone calls, inputs to an interactive voice response or USSD system, as SMS, from apps, or to publicly known short codes or access numbers. The content of the death notification may vary by country or implementation, but may include name of the deceased, name and address of relatives (for example, spouse), place and date of death, and details of the cause of death.

An example of a formal death notification, sent via mobile device, is when a health worker uses a mobile phone app to transmit information about a death, including cause of death, to a digital civil registration system. The notification may be received and reviewed for accuracy and completeness by the local civil registration office before a death certificate is issued.

An example of an informal death notification sent via a mobile device, is when a community health worker sends a message about a death, via SMS, to a central digital server, for the purpose of disease surveillance.

Why it is important to do this review

Ministries of health, donors, and decision‐makers face expanding opportunities to harness the ubiquity and penetration of mobile technology to address longstanding challenges related to acquiring accurate and timely statistics on births and deaths. There is high demand from these stakeholders for evidence‐based guidance on the value of digital tools to strengthen linkages between civil registration and health systems, as a mechanism to improve the timeliness and accuracy of birth and death statistics. In response to this global need, the World Health Organization has developed guidelines to inform investments on digital health approaches that use mobile phones for birth and death notifications (WHO Guidelines 2019).

There is growing evidence on the use of mobile devices for birth and death notification. A previous systematic review on digital interventions for Civil Registration and Vital Statistics was published in 2013 (WHO 2013a). It examined literature from 23 countries, but found limited peer‐reviewed evidence for the use of mobile devices to notify birth and death events. This review, focussed entirely on low‐ and middle‐income countries, did not report quantitative outcomes, or examine factors that influenced the use of mobile phones to notify officials of birth and death events. Since this review was published, several new studies describing birth or death notification via mobile devices have emerged. Hence, it is important to conduct a systematic review to assess these new studies. Preliminary findings from this systematic review were used to directly inform WHO guidelines on the effectiveness of digital strategies to improve data on births and deaths (WHO Guidelines 2019).

Objectives

Primary objectives

To assess the effects of birth notification via a mobile device, compared to standard practice.

To assess the effects of death notification via a mobile device, compared to standard practice.

Secondary objectives

To describe the range of strategies used to implement birth and death notification via mobile devices.

To identify factors influencing the implementation of birth and death notification via mobile devices.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

To address the primary objectives, we included the following study designs:

Individual and cluster‐randomised trials;

Cross‐over and stepped‐wedge study designs;

Controlled before‐after studies, provided they had at least two intervention sites and two control sites; and

Interrupted time series studies, if there was a clearly defined time point when the intervention occurred and at least three data points before and three after the intervention.

To address the secondary objectives, we included any study design, either quantitative, qualitative, or descriptive, that aimed to:

Describe current strategies for birth and death notification via mobile devices; or

Explore factors that influence the implementation these strategies, including studies of acceptability or feasibility.

To address both the primary and secondary objectives, we included published studies, conference abstracts, and unpublished data. We included studies regardless of their publication status and language of publication.

Types of participants

The following participants were included in this review:

All cadres of healthcare providers, including professionals, paraprofessionals, and lay health workers (LHWs);

Administrative, managerial, and supervisory staff at health facilities;

Administrative, managerial, and supervisory staff, including registrars, associated with civil registration units;

Focal individuals at the village‐ or community‐level (e.g. village leaders);

Parents or other caregivers (e.g. grandparents) of children whose birth is being notified; and

Relatives or caregivers of deceased individuals.

Types of interventions

To address the primary objectives, we included studies that compared birth and death notification via mobile devices with standard practice. We defined standard practice as non‐digital and non‐mobile, paper‐based processes and workflows for notifying birth and death events.

The comparisons for this review were:

birth notification via mobile devices compared with standard practice; and

death notification via mobile devices, compared with standard practice.

We included:

studies in which birth or death notification was sent by parents, caregivers, other family members, administrative, managerial or supervisory staff, focal individuals in the community, or health workers, via mobile devices, to alert a central system, organisation, or civil registration agency that a birth or death has taken place;

studies in which notified births were enrolled into a digital health record for tracking provision of newborn and child health services;

studies in which birth notification was part of a pregnancy digital health record, and where outcomes were reported for the postnatal period onward;

studies in which notified deaths, including cause of death, were reported to a disease surveillance system; and

studies in which birth and death notifications were delivered as part of a wider package, if we judged the birth or death notification to be the major component of the intervention.

To address the secondary objectives, in addition to the above inclusion criteria, we included:

studies in which birth and death notifications were delivered as part of a wider package:

even if birth and death notifications were judged not to be the major component of the intervention; and

as long as we could extract data on the birth and death notification components that were relevant to the secondary objectives.

When addressing both the primary and secondary objectives, we excluded:

studies in which birth and death notification was conducted on stationary computers or laptops alone;

studies that compared different specifications of technology systems (e.g. software, communication channels) for birth or death notification;

studies in which birth notification was part of a pregnancy digital health record, and where outcomes were only reported for the pregnancy period. Such studies were excluded from this review because we would not be able to link the effect of the mobile birth notification to outcomes that occurred during pregnancy. While such studies were excluded from this review, outcomes related to the pregnancy period from such studies were extracted and included in a separate review.

studies that only described interventions to improve attribution of cause of death (e.g. digital verbal autopsy tools), without a notification component; and

feasibility or pilot studies (for the primary objectives only. These study designs were included for the secondary objectives).

Types of outcome measures

Primary objective: Types of outcome measures

To address the primary objectives, we included studies that reported outcomes related to birth and death notification via mobile devices. When birth and death notifications were described in the same study, we extracted and reported outcome data for birth and death notifications separately. Specific outcomes of interest are listed below.

For birth notification via mobile device

coverage (e.g. proportion) of births notified via mobile devices;

timeliness of birth notification via mobile device (e.g. time between birth and birth notification via mobile device);

proportion of legal birth registrations in response to birth notifications via mobile device, where legal birth registration is defined as the recording, within the civil registry, of the occurrence and characteristics of births in accordance with the legal requirements of a country. Legal birth registration is conducted by a civil registrar.

timeliness of legal birth registrations in response to birth notification via mobile device (e.g. time between birth notification and legal birth registration);

coverage of (e.g. proportion of children receiving) newborn or child health services (e.g. immunisations) in response to birth notification via mobile device;

timeliness of receipt of newborn or child health services (e.g. immunisations) in response to birth notification via mobile device (i.e. time between birth and receipt of services).

For death notifications via mobile device

coverage (e.g. proportion) of deaths notified via mobile devices;

timeliness of death notification via mobile device (i.e. time between death and death notification via mobile device);

proportion of legal death registrations in response to death notifications via mobile device, where legal death registration is defined as the recording, within the civil registry, of the occurrence and characteristics of death in accordance with the legal requirements of a country. Legal death registration is conducted by a civil registrar.

timeliness of legal death registrations in response to death notification via mobile device (i.e. time between death notification and legal death registration);

proportion of deaths where causes of death were ascertained, reported, or both, to a disease surveillance system in response to death notifications via mobile device;

timeliness of causes of death ascertainment, reporting to a disease surveillance system, or both, in response to death notifications via mobile device (i.e. time between death and cause of death ascertainment).

For both birth and death notifications via mobile device

quantitative measures of notifiers’ acceptability or satisfaction (or both) with birth and death notifications via mobile device;

resource use (e.g. human resources and time, including additional time spent by notifiers when managing and transitioning from paper to digital reporting systems, training, supplies, and equipment);

unintended consequences (e.g. transmission of inaccurate data, for instance, by incorrect data entry, privacy and disclosure issues, failure or delay in message delivery, interrupted workflow due to infrastructure constraints for recharging batteries and network coverage, and impact on equity).

Secondary objectives: Topics of interest

To address the secondary objectives, we extracted data about strategies for the notification of births and deaths via mobile devices, and data about factors that influenced the implementation of these strategies.

Search methods for identification of studies

An independent information specialist (JE) developed the search strategies in consultation with the review authors. We only included studies published after 2000. This decision was based on the increased availability and penetration of mobile devices in low‐ and middle‐income countries starting in 2000 (ITU 2016). Search strategies were comprised of titles, abstracts, and keywords, including controlled vocabulary terms. We did not apply any limits on language.

We used a study design search filter used by Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) to retrieve both randomised and non‐randomised studies. See Appendix 1 for all search strategies used.

Electronic searches

To address the primary and secondary objectives, we searched the following databases:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) in the Cochrane Library (Issues 8, 2019, searched on August 2, 2019)

MEDLINE and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations and Daily 1946 to August 01, 2019, Ovid (searched on August 2, 2019)

Embase 1974 to 2019 Week 30, Ovid (searched on August 2, 2019)

Global Index Medicus/Global Health Library, WHO (searched on August 2, 2019)

POPLINE K4Heath (searched on August 2, 2019)

Searching other resources

To address both the primary and the secondary objectives, we also searched the following sources:

Trial registries

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP; www.who.int/ictrp, searched on August 2, 2019);

US National Institutes of Health Ongoing Trials Register ClinicalTrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov, searched on August 2, 2019).

Systematic review registry

We searched Epistemonikos (www.epistemonikos.org) on September 27, 2019 for related systematic reviews and potentially eligible primary studies.

Grey literature

We conducted a grey literature search to identify studies not indexed in the databases listed above, and to capture the broader range of study designs to be included for the secondary objectives. Because this review is focussed on birth and death notifications using mobile devices, we reviewed mhealthevidence.org on August, 15, 2017 for contributed content that is not referenced in MEDLINE Ovid. In addition, the WHO issued a call for papers through popular digital health communities of practice, such as the Global Digital Health Network and Implementing Best Practices, to identify additional primary studies and grey literature. Results from the grey literature were only incorporated in the first round of the search since the mhealthevidence.org database was no longer being curated at the time of subsequent searches.

Other resources

We reviewed reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews for potentially eligible studies.

We contacted authors of included studies and reviews to clarify reported published information, and to seek unpublished results and data.

We conducted citation searches of included studies in Web of Science, Clarivate Analytics; and in Google Scholar (searched on May 15, 2020).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching to a reference management database, and removed duplicates. Two review authors independently screened titles and abstracts for inclusion. We retrieved the full‐text study reports and publications, and two review authors independently screened the full texts, identified studies for inclusion, and identified and recorded reasons for excluding ineligible studies. We resolved any disagreement through discussion or, if required, we consulted a third review author. For one study in French, we consulted with a review author with appropriate fluency.

We listed studies that initially appeared to meet the inclusion criteria, but that we excluded after reviewing the full‐text report, in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the review. We also recorded any information that we could obtain about relevant ongoing studies. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Liberati 2009).

Data extraction and management

We used the EPOC standard data collection form and adapted it for study characteristics and outcome data (EPOC 2017a); we piloted the form on at least one study in the review.

To address the primary objectives, two review authors independently extracted the study characteristics from the included studies, including:

General information: title, reference details, author contact details, publication type, funding source, conflicts of interest of study authors;

Methods: study design, number of study sites and location, study setting, withdrawals, date of study, follow‐up;

Participants: number, mean age, age range, gender, severity of condition, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, other relevant characteristics;

Interventions: intervention components, comparison, intervention purpose, mode, timing, frequency, and duration of intervention delivery, content of the intervention, type of mobile device used (smartphone, tablet, feature phone, basic phone), interoperability, compliance with national guidelines, data security, fidelity assessment;

Outcomes: main and other outcomes specified and collected, time points reported;

Notes: funding for trial, notable conflicts of interest of trial authors, ethical approval, interoperability, data security, compliance with national guidelines, limitations for delivery at scale.

Two review authors independently extracted outcome data from included studies. We noted in the Characteristics of included studies table if outcome data were reported in an unusable way. We resolved disagreements by consensus or by involving a third review author.

To address the first of the secondary objectives on describing the range of strategies to used to implement birth and death notification via mobile devices, one review author extracted descriptive data where applicable and available, including the details of the intervention/s used, groups or stakeholders involved in implementing the intervention, pathway of action (how they thought it would work), context of implementation, type of evaluation (study design), and outcome measures assessed. A second review author checked the extracted data.

To address the second of the secondary objectives on assessing the factors affecting the implementation of birth and death notifications via mobile device, one review author used the SURE (Supporting the Use of Research Evidence) framework (Appendix 2), which provides a comprehensive list of possible factors that may influence the implementation of health system interventions (Glenton 2017; SURE 2011). A second review author checked the extracted data. We extracted data on:

health system constraints (e.g. accessibility of care, financial resources, human resources, educational and training system, including recruitment and selection, clinical supervision, support structures and guidelines, internal communication, external communication, allocation of authority, accountability, community participation, management or leadership (or both), information systems, facilities, client processes, distribution systems, incentives, bureaucracy, relationship with norms and standards)

individual characteristics (e.g. knowledge and skills, attitudes regarding programme acceptability, appropriateness and credibility, motivation to change or adopt new behaviour)

social and political constraints (e.g. ideology, governance, short‐term thinking, contracts, legislation or regulation, donor policies, influential people, corruption, political stability and commitment)

In addition, we included any emergent codes which were not captured within the SURE framework but that described implementation challenges.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies for the primary objective

For studies addressing the primary objectives, two review authors independently assessed risk of bias, using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011), and the guidance from the EPOC group (EPOC 2017b). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion, or by involving a third review author. We assessed the risk of bias according to the following domains:

random sequence generation;

allocation concealment;

baseline outcomes measurements similar;

baseline characteristics similar;

incomplete outcome data;

knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study;

protection against contamination;

selective outcome reporting;

other risks of bias;

intervention independent of other changes (interrupted time series studies only);

shape of the intervention effect if prespecified (interrupted time series studies only);

intervention unlikely to affect data collection (interrupted time series studies only).

We judged each potential source of bias as high, low, or unclear, and provided a quote from the study report together with a justification for our judgement in the Risk of bias in included studies table. We summarised the 'Risk of bias' judgements for each of the domains listed. We considered blinding separately for different key outcomes where necessary (e.g. for unblinded outcome assessment, risk of bias for all‐cause mortality may be very different than for a patient‐reported pain scale). Where information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or correspondence with a trialist, we noted this in the Risk of bias in included studies table. We did not exclude studies on the grounds of their risk of bias, but clearly reported the risk of bias when presenting the results of the studies.

When considering intervention effects, we took into account the risk of bias of the studies that contributed to that outcome.

We conducted the review according to this published protocol and have reported any deviations form it in the Differences between protocol and review section of this review.

Assessment of methodological limitations of included studies for the secondary objectives

For the secondary objectives, the included studies comprised a multitude of study designs and study aims, including case studies that were primarily descriptive. We were unable to find an accepted tool designed to appraise methodological limitations that could accommodate this variation in study design. We, therefore, piloted a newly developed tool for assessing the limitations of sources, such as programme reports, that do not use typical empirical research designs. One review author assessed the limitations of the studies using the Ways of Evaluating Important and Relevant Data (WEIRD) Tool (Lewin 2019) and a second review author checked the assessments. The tool, which is currently being piloted in EPOC and other systematic reviews, is available in Appendix 3.

For each item/question in the tool, the review author selected one of the following response options:

Yes ‐ the item was addressed adequately in the source

Unclear ‐ it is not clear if the item was addressed adequately in the source

No ‐ the item was not addressed adequately in the source

Not applicable ‐ the item is not relevant to the source being assessed

Based on the assessments for each WEIRD tool item, an overall assessment of the limitations of the source was made as follows:

Where the assessments for most items in the tool were 'Yes' ‐ no or few limitations

Where the assessments for most items in the tool were 'Yes' or 'Unclear' ‐ minor limitations

Where the assessments for one or more questions in the tool were 'No' ‐ major limitations

The overall assessment for each source was then used as part of the GRADE‐CERQual assessment of how much confidence to place in each secondary objective finding.

Measures of treatment effect

For the analyses of the primary objectives, we reported means and proportions, where appropriate. When applicable, we estimated the effect of the intervention using risk ratio or risk difference for dichotomous data, together with the associated 95% confidence interval, and mean difference or standardised mean difference for continuous data, together with the associated 95% confidence interval. We ensured that an increase in scores for continuous outcomes could be interpreted in the same way for each outcome, explained the direction to the reader, and reported where the directions were reversed, if this was necessary.

Unit of analysis issues

For the analyses of the primary objectives, we performed data analysis at the same level as the allocation to avoid unit of analyses errors. We did not identify any cluster‐randomised trials for inclusion in the review. See Appendix 4 for methods specified in the protocol (Vasudevan 2019) but not used in the review.

Dealing with missing data

For the analyses of the primary objectives, we intended to contact investigators in order to verify key study characteristics and request missing outcome data (e.g. when a study was identified as abstract only), but this was not an issue.

Assessment of heterogeneity

For the analyses of the primary objectives, we intended to assess the heterogeneity of studies, but due to insufficient numbers of studies identified, we did not conduct the assessment. See Appendix 4 for methods specified in the protocol (Vasudevan 2019) but not used in the review.

Assessment of reporting biases

For the analyses of the primary objectives, we did not explore the impact of including studies with missing data since this was not an issue. See Appendix 4 for methods specified in the protocol (Vasudevan 2019) but not used in the review.

Data synthesis

For the analyses of the primary objectives, we proposed to undertake meta‐analyses only where this was meaningful, i.e. if the treatments, participants, and the underlying clinical question were similar enough for pooling to make sense. See Appendix 4 for methods specified in the protocol (Vasudevan 2019) but not used in the review.

To address the first of the secondary objectives (to describe the range of strategies used to implement birth‐death notification via mobile device), we presented the range of strategies that we identified in a table format.

To address the second of the secondary objectives (to identify factors influencing the implementation of birth‐death notification via mobile device), one review author familiarised themself with the extracted data and then applied the SURE framework, moving between the data and the themes covered in the framework, but also searching for additional themes until all the extracted data had been assessed. Two review authors then assessed, discussed and agreed upon the definitions and boundaries of each of the emerging themes.

To develop the implications for practice, one review author went through each finding, identified factors that may influence the implementation of the intervention, and developed prompts for future implementers. These prompts were reviewed by at least one other review author. These prompts are not intended to be recommendations, but are instead phrased as questions to help implementers consider the implications of the review findings in their context. The questions are presented in the ‘Implications for practice’ section.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

If meaningful, we planned to carry out the following subgroup analyses:

by study setting (e.g. high‐income versus low‐ and middle‐income countries; urban versus rural);

by whether there was an existing CRVS (paper‐based) system in place versus no CRVS system in place at all;

by whether the notification was formal (i.e. for civil registration) versus informal (for purposes other than civil registration).

We proposed to use the following outcomes in subgroup analysis.

For birth notifications via mobile device

coverage (e.g. proportion) of births notified via mobile device;

timeliness of birth notifications via mobile device (e.g. time between birth and birth notification via mobile device);

timeliness of receipt of newborn or child health services (e.g. immunisations) in response to birth notifications via mobile device (i.e. time between birth and receipt of services).

For death notifications via mobile device

coverage (e.g. proportion) of deaths notified via mobile device;

timeliness of death notifications via mobile device (i.e. time between death and death notification via mobile device);

timeliness of cause of death ascertainment, reporting to a disease surveillance system, or both, in response to death notifications via mobile device (i.e. time between death and cause of death ascertainment).

Sensitivity analysis

See Appendix 4 for methods related to subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity for the primary objectives that were specified in the protocol (Vasudevan 2019) but not used in the review.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

For the primary objectives, two review authors independently assessed the certainty of the evidence (high, moderate, low, and very low), using the five GRADE considerations (risk of bias, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias (Guyatt 2008)). We used methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of interventions (Higgins 2011), and the EPOC worksheets (EPOC 2017d), and GRADEpro software (GRADEpro GDT). We resolved disagreements on certainty ratings by discussion and have provided justification for decisions to down‐ or upgrade the ratings, using footnotes in the table. We used plain language statements to report these findings in the review (EPOC 2017e).

We summarised our findings in 'Summary of findings' tables (EPOC 2017d) for the main intervention comparisons, and included the most important outcomes and the certainty of the evidence for these outcomes.

For the secondary objectives, one review author used the GRADE‐CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research) approach to assess our confidence in each finding (Lewin 2018) and a second review author checked the assessments. GRADE‐CERQual assesses confidence in the evidence, based on the following four key components: methodological limitations of included studies; coherence of the review finding; adequacy of the data contributing to a review finding; and relevance of the included studies to the review question. After assessing each of the four components, we made a judgement about the overall confidence in the evidence supporting the review finding. We assessed confidence as high, moderate, low, or very low. The final assessment was based on consensus among the two review authors. All findings started as high confidence and were then graded down if there were important concerns regarding any of the GRADE‐CERQual components.

We presented summaries of the findings and our assessments of confidence in these findings in Table 2. We also presented detailed descriptions of our confidence assessment in Appendix 5.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

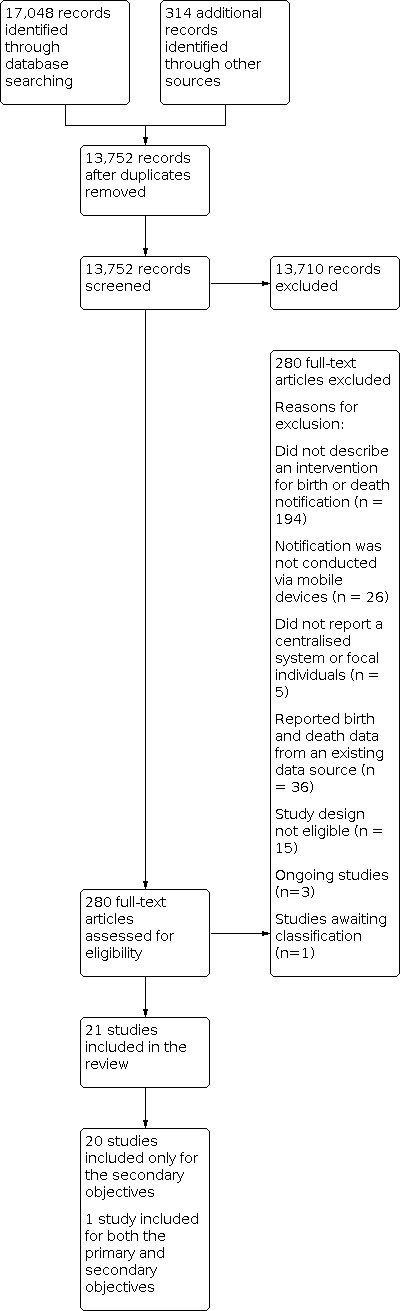

We included 21 studies in the review. We also found three ongoing studies and one study awaiting classification. Figure 2 summarises the study selection process as a PRISMA flowchart. For an overview of the included studies, see the Characteristics of included studies table. For an overview of the studies that we excluded during full‐text review, see the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

2.

Study flow diagram.

From the 21 included studies, we identified one study that met the inclusion criteria for the primary objectives. This study described a birth notification intervention (Xeuatvongsa 2016). We did not find any studies that described a death notification intervention and that met the inclusion criteria for the primary objectives. We identified three ongoing studies that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria for the primary objectives and that are described in the Characteristics of ongoing studies table. The study awaiting classification is reported in the Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

All 21 included studies addressed the secondary objectives (Andreatta 2011; ANISA 2016; eCRVS‐Mozambique 2017; Gisore 2012; MBRG 2014; MBRL 2011; MBRP 2015; MBRT 2016; Moshabela 2015; MOVE‐IT 2013; mSIMU 2017; mTika 2016; MVH 2017; mVRS 2017; Ngabo 2012; NIMDS 2019; Pascoe 2012; RapidSMS 2012; Van Dam 2015; Xeuatvongsa 2016; Yugi 2016).

Included studies

Study design and comparisons

The study addressing the primary objectives employed a controlled before‐after study design. (Xeuatvongsa 2016). The comparison was standard of care. This study measured the following outcomes: coverage and timeliness of birth notification, and coverage and timeliness of post‐notification health services.

Many studies addressing the secondary objectives were descriptive reports of programmes rather than formal qualitative or quantitative studies (Characteristics of included studies). The three studies that used rigorous study designs were controlled before‐after studies (mTika 2016; Xeuatvongsa 2016) and a cluster‐randomised trial (mSIMU 2017). One of these studies was also included in relation to the primary review objectives (Xeuatvongsa 2016), while the other two did not report the necessary outcomes for inclusion in relation to the primary review objectives. For all studies addressing the secondary objectives (including the before‐after studies and the randomised trial), most of the data we extracted were based on operational data. In many cases, the data were taken from the discussion section or other sections of the report, and were often based on the report authors’ own observations.

Setting

The study that addressed the primary objectives was conducted in Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Xeuatvongsa 2016).

The studies that addressed the secondary objectives were also conducted in low‐ or middle income settings. Five studies took place in Asia: Lao People’s Democratic Republic (Xeuatvongsa 2016), Bangladesh (mTika 2016), Pakistan (ANISA 2016; MBRP 2015; NIMDS 2019), and India (ANISA 2016). Fifteen studies took place in sub‐Saharan Africa: Kenya (Gisore 2012; mSIMU 2017), Mozambique (eCRVS‐Mozambique 2017), Tanzania (MBRT 2016; MOVE‐IT 2013; Pascoe 2012), Zambia (Van Dam 2015), Liberia (MBRL 2011), Ghana (Andreatta 2011; MBRG 2014), Uganda (mVRS 2017), Rwanda (Ngabo 2012), South Sudan (Yugi 2016), Nigeria (RapidSMS 2012) and Senegal (Moshabela 2015). One study took place in the Middle East: Syria (MVH 2017). There were no studies in high‐income settings.

With the exception of the eRegister platform (Van Dam 2015) in Lusaka, Zambia, all included studies focussed on identification of births and deaths in rural, remote, or marginalised populations who are typically under‐represented in civil registration processes or traditionally seen as having poor access to health services. The mTika study implemented a birth notification intervention in Dhaka, but focussed on populations in urban slums (mTika 2016).

Participants

We classified individuals providing notifications into one of four categories: lay health workers, family members, healthcare organisations, and community‐based informants.

In the study addressing the primary objectives, birth notification was conducted by healthcare workers and a cadre of lay health workers called village health workers (Xeuatvongsa 2016).

In most of the studies addressing the secondary objectives, notification of births and deaths was conducted by lay health workers.

Lay health workers included community‐based and facility‐based workers such as traditional birth attendants, immunisation providers, community health workers (e.g. Lady Healthcare Worker, Accredited Social Health Activists), and village heath volunteers. (Andreatta 2011; MBRL 2011; MBRT 2016; Moshabela 2015; mTika 2016; Ngabo 2012; NIMDS 2019; RapidSMS 2012; Van Dam 2015; Xeuatvongsa 2016; Yugi 2016)

In one of these studies, individuals from healthcare organisations and NGOs (non‐governmental organisations) that were part of the Syria Response Turkey Health Cluster used the Monitoring Violence against Health Care (MVH) tool to notify deaths (MVH 2017).

Eight of these 21 studies included community‐based informants such as village elders, village chiefs, community volunteers, village reporters, marriage registrars, telecom agents, village executive officers, or village residents with access to a mobile phone (ANISA 2016; eCRVS‐Mozambique 2017; Gisore 2012; MBRG 2014; MBRP 2015; MOVE‐IT 2013; mSIMU 2017; mVRS 2017).

In two of the 21 studies, mothers or other family members were provided instructions or resources to directly report births to a centralised server (ANISA 2016; mTika 2016)

Interventions for notification of births and deaths via mobile devices

The study addressing the primary objectives only implemented birth notification.

Among the 22 studies addressing the secondary objectives:

Nine implemented birth notification only (ANISA 2016; MBRL 2011; MBRP 2015; MBRT 2016; mSIMU 2017; mTika 2016; mVRS 2017; RapidSMS 2012; Xeuatvongsa 2016).

Five implemented death notification only (MVH 2017; NIMDS 2019; Pascoe 2012; Van Dam 2015; Yugi 2016).

Seven implemented both birth and death notification via mobile devices (Andreatta 2011; eCRVS‐Mozambique 2017; Gisore 2012; MBRG 2014; Moshabela 2015; MOVE‐IT 2013; Ngabo 2012).

Eight studies described efforts to increase birth or death notification in conjunction with the national civil registration authority (eCRVS‐Mozambique 2017; MBRG 2014; MBRL 2011; MBRP 2015; MBRT 2016; MOVE‐IT 2013; mVRS 2017; RapidSMS 2012), while the remaining studies used birth or death notification to increase the coverage or timeliness of health services (Andreatta 2011; ANISA 2016; Gisore 2012; Moshabela 2015; mSIMU 2017; mTika 2016; Ngabo 2012; NIMDS 2019; Van Dam 2015; Xeuatvongsa 2016), and disease surveillance programs (Pascoe 2012; Yugi 2016). One study collected data on mortality resulting from attacks on healthcare organisations to assess violations of international humanitarian laws during war (MVH 2017).

The majority of the studies used basic mobile phones with voice and SMS capabilities. Birth notification was typically relayed as a text message (Andreatta 2011; MBRT 2016; MOVE‐IT 2013; mSIMU 2017; Ngabo 2012; mTika 2016; RapidSMS 2012), via phone call (ANISA 2016; Xeuatvongsa 2016), or via USSD (eCRVS‐Mozambique 2017; mVRS 2017). In one study in Kenya, each pair of village elder and registry administrator determined their modality of mobile phone communication (Gisore 2012). For birth notification, several studies used smartphone‐based apps. (MBRG 2014; MBRL 2011; MBRP 2015; MBRT 2016; Moshabela 2015) Most common modalities of death notification were SMS (Andreatta 2011; Ngabo 2012; NIMDS 2019; Yugi 2016) or smartphone‐based apps (Moshabela 2015; MVH 2017; Pascoe 2012; Van Dam 2015).

Some studies used open source data collection platforms such as RapidSMS (Ngabo 2012; RapidSMS 2012), Nokia Data Gathering (MBRL 2011), CommCare (Van Dam 2015), ChildCount+ (Moshabela 2015) and District Health Information Software 2 (DHIS2) (Pascoe 2012). System interoperability with national‐level health information systems was described poorly in the included sources. Only three studies described linkages of birth or death notification information to national‐level systems: DHIS2 in Tanzania (Pascoe 2012), a national Data Health Information System (DHIS) in South Sudan (Yugi 2016), and the Bangladesh Ministry of Health and Family Welfare’s Management Information System (mTika 2016).

Funding and conflicts

Sixteen studies listed their sources of funding (Andreatta 2011; ANISA 2016; Gisore 2012; MBRG 2014; MBRL 2011; MBRP 2015; MBRT 2016; MOVE‐IT 2013; mSIMU 2017; mTika 2016; MVH 2017; Ngabo 2012; RapidSMS 2012; Van Dam 2015; Xeuatvongsa 2016; Yugi 2016). Conflict of interest statements were available in reports of 12 studies (Andreatta 2011; ANISA 2016; Gisore 2012; MBRL 2011; Moshabela 2015; mTika 2016; MVH 2017; Ngabo 2012; NIMDS 2019; Van Dam 2015; Xeuatvongsa 2016; Yugi 2016).

Excluded studies

We excluded 242 studies from the review following full‐text screening. Studies were excluded because they did not describe an intervention for birth or death notification (n = 160); notification was not conducted via mobile devices or the use of mobile devices for notification was poorly described (n = 26); they did not report a centralised system or focal individuals for birth or death notification (n = 5); the studies used existing sources of data (n = 36); or the publications were not of relevant design (n = 15) (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Risk of bias in included studies

Risk of bias in included studies addressing the primary objective

The study that met the eligibility criteria for addressing the primary objective (Xeuatvongsa 2016) used a controlled before‐after study design. We judged the study as having high or unclear risk across various criteria, as described in Table 3.

1. Risk of bias in the included study for the primary objective (Xeuatvongsa 2016).

| Bias | Authors' judgementa | Support for judgement |