Notes

Editorial note

There is a more recent Cochrane review on this topic: https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013668.pub2

Abstract

Background

Self‐harm (SH; intentional self‐poisoning or self‐injury) is common, often repeated, and associated with suicide. This is an update of a broader Cochrane review first published in 1998, previously updated in 1999, and now split into three separate reviews. This review focuses on psychosocial interventions in adults who engage in self‐harm.

Objectives

To assess the effects of specific psychosocial treatments versus treatment as usual, enhanced usual care or other forms of psychological therapy, in adults following SH.

Search methods

The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) trials coordinator searched the CCDAN Clinical Trials Register (to 29 April 2015). This register includes relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs) from: the Cochrane Library (all years), MEDLINE (1950 to date), EMBASE (1974 to date), and PsycINFO (1967 to date).

Selection criteria

We included RCTs comparing psychosocial treatments with treatment as usual (TAU), enhanced usual care (EUC) or alternative treatments in adults with a recent (within six months) episode of SH resulting in presentation to clinical services.

Data collection and analysis

We used Cochrane's standard methodological procedures.

Main results

We included 55 trials, with a total of 17,699 participants. Eighteen trials investigated cognitive‐behavioural‐based psychotherapy (CBT‐based psychotherapy; comprising cognitive‐behavioural, problem‐solving therapy or both). Nine investigated interventions for multiple repetition of SH/probable personality disorder, comprising emotion‐regulation group‐based psychotherapy, mentalisation, and dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT). Four investigated case management, and 11 examined remote contact interventions (postcards, emergency cards, telephone contact). Most other interventions were evaluated in only single small trials of moderate to very low quality.

There was a significant treatment effect for CBT‐based psychotherapy compared to TAU at final follow‐up in terms of fewer participants repeating SH (odds ratio (OR) 0.70, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.55 to 0.88; number of studies k = 17; N = 2665; GRADE: low quality evidence), but with no reduction in frequency of SH (mean difference (MD) ‐0.21, 95% CI ‐0.68 to 0.26; k = 6; N = 594; GRADE: low quality).

For interventions typically delivered to individuals with a history of multiple episodes of SH/probable personality disorder, group‐based emotion‐regulation psychotherapy and mentalisation were associated with significantly reduced repetition when compared to TAU: group‐based emotion‐regulation psychotherapy (OR 0.34, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.88; k = 2; N = 83; GRADE: low quality), mentalisation (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.73; k = 1; N = 134; GRADE: moderate quality). Compared with TAU, dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) showed a significant reduction in frequency of SH at final follow‐up (MD ‐18.82, 95% CI ‐36.68 to ‐0.95; k = 3; N = 292; GRADE: low quality) but not in the proportion of individuals repeating SH (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.21 to 1.59, k = 3; N = 247; GRADE: low quality). Compared with an alternative form of psychological therapy, DBT‐oriented therapy was also associated with a significant treatment effect for repetition of SH at final follow‐up (OR 0.05, 95% CI 0.00 to 0.49; k = 1; N = 24; GRADE: low quality). However, neither DBT vs 'treatment by expert' (OR 1.18, 95% CI 0.35 to 3.95; k = 1; N = 97; GRADE: very low quality) nor prolonged exposure DBT vs standard exposure DBT (OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.08 to 5.68; k = 1; N =18; GRADE: low quality) were associated with a significant reduction in repetition of SH.

Case management was not associated with a significant reduction in repetition of SH at post intervention compared to either TAU or enhanced usual care (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.47 to 1.30; k = 4; N = 1608; GRADE: moderate quality). Continuity of care by the same therapist vs a different therapist was also not associated with a significant treatment effect for repetition (OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.07 to 1.10; k = 1; N = 136; GRADE: very low quality). None of the following remote contact interventions were associated with fewer participants repeating SH compared with TAU: adherence enhancement (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.02; k = 1; N = 391; GRADE: low quality), mixed multimodal interventions (comprising psychological therapy and remote contact‐based interventions) (OR 0.98, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.43; k = 1 study; N = 684; GRADE: low quality), including a culturally adapted form of this intervention (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.44 to 1.55; k = 1; N = 167; GRADE: low quality), postcards (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.23; k = 4; N = 3277; GRADE: very low quality), emergency cards (OR 0.82, 95% CI 0.31 to 2.14; k = 2; N = 1039; GRADE: low quality), general practitioner's letter (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.44; k = 1; N = 1932; GRADE: moderate quality), telephone contact (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.42 to 1.32; k = 3; N = 840; GRADE: very low quality), and mobile telephone‐based psychological therapy (OR not estimable due to zero cell counts; GRADE: low quality).

None of the following mixed interventions were associated with reduced repetition of SH compared to either alternative forms of psychological therapy: interpersonal problem‐solving skills training, behaviour therapy, home‐based problem‐solving therapy, long‐term psychotherapy; or to TAU: provision of information and support, treatment for alcohol misuse, intensive inpatient and community treatment, general hospital admission, or intensive outpatient treatment.

We had only limited evidence on whether the intervention had different effects in men and women. Data on adverse effects, other than planned outcomes relating to suicidal behaviour, were not reported.

Authors' conclusions

CBT‐based psychological therapy can result in fewer individuals repeating SH; however, the quality of this evidence, assessed using GRADE criteria, ranged between moderate and low. Dialectical behaviour therapy for people with multiple episodes of SH/probable personality disorder may lead to a reduction in frequency of SH, but this finding is based on low quality evidence. Case management and remote contact interventions did not appear to have any benefits in terms of reducing repetition of SH. Other therapeutic approaches were mostly evaluated in single trials of moderate to very low quality such that the evidence relating to these interventions is inconclusive.

Plain language summary

Psychosocial interventions for self‐harm in adults

Why is this review important?

Self harm (SH), which includes non‐fatal intentional self‐poisoning/overdose and self‐injury, is a major problem in many countries and is linked to risk of future suicide. It is distressing for both patients and their families and friends, and places large demands on clinical services. It is therefore important to assess the evidence on treatments for SH patients.

Who will be interested in this review?

Clinicians working with people who engage in SH, policy makers, people who themselves have engaged in SH or may be at risk of doing so, and their families and relatives.

What questions does this review aim to answer?

This review is an update of a previous Cochrane review from 1999, which found little evidence of beneficial effects of psychosocial treatments on repetition of SH. This update aims to further evaluate the evidence for the effectiveness of psychosocial treatments for patients with SH with a broader range of outcomes.

Which studies were included in the review?

To be included in the review, studies had to be randomised controlled trials of psychosocial interventions for adults who had recently engaged in SH. We searched electronic databases to find all such trials published up until 29 April 2015, and found 55 that met our inclusion criteria.

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

There have now been a number of investigations of psychosocial treatments for SH in adults, with greater representation in recent years of low‐ and middle‐income countries such as China, Iran, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

Some moderate quality evidence shows that cognitive‐behavioural‐based (CBT‐based) psychotherapy (a psychotherapy intended to change unhelpful thinking, emotions and behaviour) may help prevent repetition of SH, although it did not reduce overall frequency of SH. There were encouraging results (from small trials of moderate to very low quality) for other interventions aimed at reducing the frequency of SH in people with probable personality disorder, including group‐based emotion‐regulation psychotherapy, mentalisation (a psychosocial therapy intended to increase a person’s understanding of their own and others' mental state), and dialectical behaviour therapies (DBT; psychosocial therapies intended to assist with identification of triggers that lead to reactive behaviours and to provide individuals with emotional coping skills to avoid these reactions). Whilst DBT was not associated with a significant reduction in repetition of SH at final follow‐up as compared to usual treatment, there was evidence of low quality suggesting a reduction in frequency of SH.

There was no clear evidence supporting the effectiveness of prolonged exposure to DBT, case management, approaches to improve treatment adherence, mixed multimodal interventions (comprising both psychological therapy and remote contact‐based interventions), remote contact interventions (postcards, emergency cards, and telephone contact), interpersonal problem‐solving skills training, behaviour therapy, provision of information and support, treatment for alcohol misuse, home‐based problem‐solving therapy, intensive inpatient and community treatment, general hospital admission, intensive outpatient treatment, or long‐term psychotherapy.

We had only limited evidence from a subset of the studies relating to whether the intervention had different effects in men and women. The trials did not report on side effects other than suicidal behaviour.

What should happen next?

The promising results for CBT‐based psychological therapy and dialectical behaviour therapy warrant further investigation to understand which patients benefit from these types of interventions. There were only a few, generally small trials on most other types of psychosocial therapies, providing little evidence of beneficial effects; however, these cannot be ruled out. There is a need for more information about whether psychosocial interventions might work differently between men and women.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

The term 'self‐harm' is used to describe all non‐fatal intentional acts of self‐poisoning or self‐injury, irrespective of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation (Hawton 2003a). Thus it includes acts intended to result in death ('attempted suicide'), those without suicidal intent (e.g., to communicate distress, to temporarily reduce unpleasant feelings), and those with mixed motivation (Hjelmeland 2002; Scoliers 2009). The term 'parasuicide' was introduced by Kreitman 1969 to include the same range of behaviour. However, clinicians in the USA have used 'parasuicide' to refer specifically to acts of self‐harm without suicidal intent (Linehan 1991), and the term has largely fallen into disuse in the UK and other countries. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM‐5) includes two types of self‐harming behaviour as conditions for further study, namely non‐suicidal self‐injury (NSSI) and suicidal behaviour disorder (SBD). Many researchers and clinicians, however, believe this to be an artificial and somewhat misleading categorisation (Kapur 2013). We have therefore used the approach favoured in the UK and some other countries where all intentional self‐harm is conceptualised in a single category, namely self‐harm (SH). Within this category, suicidal intent is regarded as a dimensional rather than a categorical concept. Readers more familiar with the NSSI and SBD distinction may regard SH as an umbrella term for these two behaviours (although it should be noted that neither NSSI nor SBD include non‐fatal self‐poisoning).

SH has been a growing problem in most countries over the past 40 years. In the UK, researchers estimate that there are now more than 200,000 presentations to general hospitals per year (Hawton 2007). In addition, self‐harm often occurs in adults in the community and does not come to the attention of clinical services or other helping agencies (Borges 2011). SH consumes considerable hospital resources in both developed and developing countries (Carter 2005; Claassen 2006; Fleischmann 2005; Gibbs 2004; Kinyanda 2005; Parkar 2006; Schmidtke 1996; Schmidtke 2004).

Unlike suicide, in most countries SH usually occurs more commonly in females than males, although this gap decreases over the life cycle (Hawton 2008). It has also decreased in recent years (Perry 2012). SH predominantly occurs in young people, with 60% to 70% of individuals in many studies aged under 35 years. In females, rates tend to be particularly high among those aged 15 to 24, whereas in males the highest rates are usually among those in their late 20s and early 30s. SH is also less common in older people but then tends to be associated with high suicidal intent (Hawton 2008), with consequent greater risk of future suicide (Murphy 2012).

Many people who engage in SH are facing acute life problems, often in the context of longer‐term difficulties (Hawton 2003b). Common problems include disrupted relationships, employment difficulties, financial and housing problems, and social isolation. Alcohol abuse and, to a lesser extent, drug misuse are often present. There may be a history of adverse experiences, such as physical abuse, sexual abuse, or both. In older people, physical health problems, bereavement, and threatened loss of independence become increasingly important.

Many patients who present to hospital following SH have psychiatric disorders, especially depression, anxiety, and substance misuse (Hawton 2013). These disorders frequently occur in combination with personality disorder (Haw 2001).

Both psychological and biological factors appear to increase vulnerability to SH. Psychological factors include difficulties in problem‐solving and a tendency to show black and white (or all or none) thinking patterns, low self‐esteem, impulsivity, vulnerability to having pessimistic thoughts about the future (i.e., hopelessness) and a sense of entrapment ( O'Connor 2012: Williams 2000; Williams 2005). Biological factors include disturbances in the serotonergic and stress‐response systems (Van Heeringen 2014).

SH is often repeated, with 15% to 25% of individuals who present to hospital with SH returning to the same hospital following a repeat episode within a year (Carroll 2014; Owens 2002). Studies from Asia suggest a lower risk of repetition (Carroll 2014). There may be other repeat episodes that do not result in hospital presentation.

The risk of death by suicide within one year amongst people who attend hospital with SH varies across different studies, from nearly 1% to over 3% (Carroll 2014; Owens 2002). This variation reflects differences in the characteristics of the SH population and background national suicide rates. During the first year after a SH episode, the risk in the UK is 50 to 100 times that of the general population (Cooper 2005; Hawton 1988; Hawton 2003b). Of people who die by suicide, over half will have a history of SH (Foster 1997), and at least 15% will have presented to hospital with SH in the preceding year (Gairin 2003). A history of SH is the strongest risk factor for suicide across a range of psychiatric disorders (Sakinofsky 2000). Repetition of SH further increases the risk of suicide (Zahl 2004).

Description of the intervention

Psychosocial interventions include a wide variety of treatments, for example cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), problem‐solving therapy, behaviour therapy, and dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT). Treatments may vary in relation to the initial management; the location of treatment; the continuity, intensity or frequency of contact with a therapist; and the mode of delivery (individual or group‐based). We included treatments that focused on specific subgroups of SH patients in this review. These subgroups may be defined in terms of age, psychological characteristics or psychiatric diagnoses, substance misuse, and history of repetition of self‐harm. We also included studies of strategies to maintain contact with patients, such as visits to patients with poor therapeutic adherence, and contact by telephone, post and electronic means.

How the intervention might work

The mechanisms of action of psychosocial interventions might include helping people improve their coping skills and self‐esteem, tackle specific problems, overcome psychiatric disorders, increase their sense of social connectedness, and reduce impulsivity, aggression and unhelpful reactions to distressing situations.

CBT‐based psychotherapy

CBT aims to help patients identify and critically evaluate the way in which they interpret and evaluate disturbing emotional experiences and events and then change the way they deal with problems (Westbrook 2011). The therapy has three steps. First, therapists help patients change the way in which they interpret and evaluate distressing emotions. Secondly, patients learn strategies to help them change the way they think about the meaning and consequences of these emotions. Lastly, with the benefit of modified interpretation of emotions and events, the therapy helps patients to change their behaviour and especially to develop positive functional behaviour (Jones 2012).

Problem‐solving therapy, which is an integral part of CBT, assumes that psychopathological processes such as SH are ineffective and maladaptive coping behaviours. Patients might overcome them by learning skills to actively, constructively and effectively solve the problems they face in their daily life (Nezu 2010). Therapists might achieve this by encouraging patients to consciously and rationally appraise problems, reduce or modify the negative emotions generated by problems, and develop a range of possible solutions to address their problems (D'Zurilla 2010). Treatment goals include helping patients to develop a positive problem‐solving orientation, use rational problem‐solving strategies, reduce the tendency to avoid problem‐solving, and reduce the use of impulsive problem‐solving strategies (Washburn 2012).

Our rationale for including CBT and problem‐solving therapy approaches in a single category of CBT‐based psychotherapy in this review is that they share common elements. For example, problem‐solving therapy incorporates other elements of behaviour therapy and constitutes a key part of cognitive behavioural therapy; also, cognitive‐behavioural strategies are important for effective problem‐solving therapy (Hawton 1989; Westbrook 2011)

Interventions for multiple repetition of SH/probable personality disorder

The goal of emotion‐regulation training is to help patients find adaptive ways to respond to distress instead of trying to control, suppress or otherwise avoid experiencing these emotions through behaviours such as SH (Gratz 2007). Emotion‐regulation training therefore helps patients in four stages: first, to become more aware and accepting of their emotional experiences; second, to engage in goal‐directed behaviours whilst inhibiting the expression of impulsive ones; third, to use appropriate strategies to moderate the intensity and duration of their emotional responses; and fourth, to become more accepting of negative emotional experiences within their daily life (Gratz 2004).

Dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT) combines problem‐solving training, skills training, cognitive modification training and mindfulness techniques to encourage patients to accept their thoughts, feelings, and behaviours without necessarily attempting to change, suppress, or avoid these experiences (Lynch 2006; Washburn 2012). Within this framework, the aim of DBT is to help patients better regulate their emotions, achieve a sense of interpersonal effectiveness, become more tolerant of distressing thoughts and feelings, and become better at managing their own thoughts and behaviours (Linehan 1993b; Linehan 2007). The primary treatment goals of DBT are therefore threefold: to reduce SH, to reduce behaviours that interfere with treatment success (e.g., treatment non‐adherence), and to reduce any other factors that may adversely affect the patient's quality of life (e.g., frequency and duration of psychiatric hospitalisations) (Linehan 1993b). As the aim of DBT is to help patients change or adjust to significant personality characteristics, treatment is intensive and relatively prolonged.

Mentalisation refers to the ability to understand the actions of both the self and of others as meaningful given knowledge of the desires, beliefs, feelings, emotions, and motivations that underscore their behaviour (Bateman 2004; Choi‐Kain 2008). During times of interpersonal stress, however, individuals may fail to represent experiences in terms of mental states and instead become overwhelmed with negative thoughts and feelings about the self (Rossouw 2013). Behaviours such as SH may then represent an escape from these negative self‐evaluations. Mentalisation therapy aims to improve patients' ability to empathise with others in order to develop the ability to see how their own behaviours may have an impact on the feelings of others, and to regulate their own emotions more effectively (Rossouw 2013).

Case management

Case management in mental health services has mainly been developed for more severely ill patients. "In its simplest form . . . case management is a means of co‐ordinating services. Each. . . person is assigned a 'case manager' who is expected to assess that person's needs; develop a care plan; arrange for suitable care to be provided; monitor the quality of the care provided; and maintain contact with the person (Holloway 1991)" (Marshall 2000a, p. 2). Case management might have a significant role in the aftercare of self‐harm patients because of the recognised problem of poor treatment adherence in many patients and the heterogeneous nature of the problems patients are often facing (Hawton 2003b; Lizardi 2010). It has included, for example, provision of a care manager, crisis intervention, problem solving, assistance with getting to clinical appointments, and assertive outreach, each provided according to individual patient need (Morthorst 2012).

Treatment adherence enhancement approaches

These approaches include specific efforts to maintain contact with patients, such as following up patients in the community who fail to attend outpatient appointments (Van Heeringen 1995). It also includes strategies to encourage adherence with treatment (Hvid 2011).

Having the same clinician who assessed a patient initially also providing any aftercare intervention may increase treatment adherence and may also have an advantage in that the clinician is already acquainted with the patient's problems and needs.

Remote contact interventions

Remote contact interventions typically involve sending regular letters or postcards to patients. Patients may view this kind of intervention as a 'gesture of caring' that may help to counteract the sense of social isolation many SH patients experience (Cooper 2011). This sense of "social connectedness" may, in turn, have a stabilising emotional effect (Motto 2001).

Another type of remote contact intervention involves the use of emergency cards, which may encourage patients to seek help when they feel distressed as well as offering provision for on‐demand emergency contact with psychiatric services (Kapur 2010).

The fact that in many countries most individuals have their own general practitioner (GP) can also facilitate provision of care directly following SH. Interventions may include guidance for GPs on treating and managing problems commonly experienced by SH patients (e.g., depression, substance misuse, life problems). Such advice may also include advising GPs on referral of SH patients to local community services (Bennewith 2002).

Telephone contact with patients following discharge from hospital can also help to ensure a continuing sense of contact with the service and be used to provide advice and possibly psychotherapy.

The immediacy that psychotherapy by mobile telephone can achieve, when compared with standard clinic‐based psychotherapy, may help with crisis management in times of distress (Marasinghe 2012).

Why it is important to do this review

SH is a major social and healthcare problem. It is responsible for significant morbidity, is often repeated, and has strong links to suicide. It also leads to substantial healthcare costs (Sinclair 2011). Many countries now have suicide prevention strategies (WHO 2014), which include a focus on improved management of patients presenting with SH due to their greatly elevated suicide risk and their high levels of psychopathology and distress. The National Suicide Prevention Strategy for England (Her Majesty's Government Department of Health 2012) and the US suicide prevention strategy (Office of the Surgeon General 2012), for example, highlight SH patients as a high risk group for special attention.

In recent years there has been considerable focus on improving the standards of general hospital care for SH patients. The Royal College of Psychiatrists published consensus guidelines for such services in 1994 and a further guideline in 2004 (Royal College of Psychiatrists 1994; Royal College of Psychiatrists 2004). While these guidelines focus particularly on organisation of services and assessment of patients, there clearly also need to be effective treatments for SH patients. These may include both psychosocial and pharmacological interventions. In 2004 the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) produced a guideline on self‐harm, which focused on its short‐term physical and psychological management (NCCMH 2004). More recently, NICE produced a second guide focused particularly on long‐term management, using some interim data from the present review as the evidence base for therapeutic interventions (NICE 2011). A similar guideline was produced in Australia and New Zealand (Boyce 2003). We had previously conducted a systematic review of treatment interventions for SH patients in terms of reducing repetition of SH (including suicide); this review highlighted the paucity of evidence for effective treatments, at least in terms of this outcome (Hawton 1998; Hawton 1999). The first NICE guideline essentially reinforced this conclusion (NCCMH 2004). However, there was emerging evidence for beneficial effects of short‐term psychological therapy on other outcomes (depression, hopelessness, and problem resolution) (Townsend 2001). Using interim data from the present review, the second NICE guideline concluded that there was evidence showing clinical benefit of CBT‐based psychotherapeutic interventions in reducing repetition of self‐harm, compared with routine care (NICE 2011).

We have now fully updated our original review in order to provide current evidence to guide clinical policy and practice. Previous versions of this review included SH patients of any age and both psychosocial and pharmacological interventions. We have now divided this research into three separate reviews, one of interventions in children and adolescents (Hawton 2015a), another of pharmacological interventions in adults (Hawton 2015b), and this, the third, focused on psychosocial interventions in adults. We have also now included data on treatment adherence, depression, hopelessness, problem‐solving, and suicidal ideation.

Objectives

To assess the effects of specific psychosocial treatments versus either treatment as usual, enhanced usual care or other forms of alternative psychotherapy, in adults following SH.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomised controlled trials, including cluster‐randomised, multi‐arm, and cross‐over trials of specific psychosocial interventions versus any comparator (e.g., treatment as usual [TAU]/enhanced usual care [EUC]/other alternative forms of psychotherapy) in the treatment of adult SH patients.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

Participants were adult men and women (aged 18 and over) of all ethnicities. We also included trials where there were a small minority (< 15%) of adolescent participants. However, we undertook sensitivity analyses to assess the effect of including such studies.

Diagnosis

We included participants who had engaged in any type of non‐fatal intentional self‐poisoning or self‐injury in the six months prior to trial entry resulting in presentation to clinical services. There were no restrictions on the frequency with which patients engaged in SH; thus, for example, we included trials where participants had frequently repeated SH (e.g., those with self‐harming behaviour associated with borderline personality disorder).

We defined SH as any non‐fatal intentional act of self‐poisoning or self‐injury, irrespective of degree of suicidal intent or other types of motivation. Thus we included acts intended to result in death (attempted suicide), those without suicidal intent (e.g., to communicate distress, to temporarily reduce unpleasant feelings), and those with mixed motivation. Self poisoning includes both overdoses of medicinal drugs and ingestion of substances not intended for consumption (e.g., pesticides). Self‐injury includes acts such as self‐cutting, self‐mutilation, attempted hanging, and jumping in front of moving vehicles. We only included trials where participants presented to clinical services as a result of SH.

Co‐morbidities

There were no restrictions on included patients in terms of whether or not they had psychiatric disorders nor with regard to the nature of those disorders, with the exception of intellectual disability, as any SH behaviour is likely to be repetitive (e.g., head banging), and the purpose of this behaviour is usually different from that involved in SH (NICE 2011).

Setting

Interventions delivered in inpatient or outpatient settings were eligible for inclusion, as were trials from any country.

Subset data

We did not include trials in which only some participants had engaged in SH or trials in people with psychiatric disorders where SH was an outcome variable but not an inclusion criterion for entry into the trial.

Types of interventions

Comparisons included in this review were between any psychosocial intervention and any comparator (e.g., TAU/EUC/other alternative forms of psychotherapy, or placebo). As the trials included in this review assessed a wide variety of interventions, we developed categories or groups of interventions. This categorisation was based on consensus discussions within the review team and included decisions about combining trials in which there were superficial differences between treatments but the key methodologies between trials were similar. In some cases we sought more details of the therapy from authors to assist this process. Categorisation reflected both prior views on types of psychotherapy and the types of interventions that were identified as a result of the systematic review of the literature.

Experimental interventions

These included:

CBT‐based psychotherapy;

interventions for multiple repetition of SH/probable personality disorder;

case management;

treatment adherence enhancement approaches;

mixed multimodal interventions;

remote contact interventions;

other mixed interventions.

Comparator interventions

Treatment as usual

As treatment as usual (TAU) is likely to vary widely between settings, following previous work we defined TAU as any care that patient would receive had they not been included in the trial (i.e., routine care) (Hunt 2013).

Enhanced usual care

Enhanced usual care (EUC) refers to TAU that has in some way been supplemented, for example through the provision of psycho‐education, assertive outreach, or more regular contacts with case managers.

Treatment by expert

This typically consists of a treatment by a widely recognised authority with significant experience in treating individuals following SH.

Other alternative forms of psychotherapy

This included other forms of psychotherapy designed to be of lower duration or intensity than the experimental intervention and could include:

brief or short‐term psychotherapy;

standard case management;

standard dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measure in this review was the occurrence of repeated SH (defined above) over a maximum follow‐up period of two years. Repetition was identified through at least one of the following: self‐report, collateral report, clinical records, or research monitoring systems. As we wished to incorporate the maximum amount of data from each trial, we included both self‐reported and hospital records of SH where available. We also assessed frequency of repetition of SH.

Secondary outcomes

1. Treatment adherence

This was assessed using a range of measures of adherence, including the proportion of participants that both started and completed treatment, pill counts, and changes in blood measures.

2. Depression

This was assessed either continuously, as scores on psychometric measures of depression symptoms (for example total scores on Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck 1961) or scores on the depression sub‐scale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond 1983)), or dichotomously, as the proportion of patients reaching defined diagnostic criteria for depression. We included both patient‐ and clinician‐reported instruments.

3. Hopelessness

This was assessed as scores on psychometric measures of hopelessness, for example total scores on the Beck Hopelessness Scale (BHS; Beck 1974). We included both patient‐ and clinician‐reported instruments.

4. Suicidal ideation

This was assessed suicidal ideation either continuously, as scores on psychometric measures (for example total scores on the Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI; Beck 1988)), or dichotomously, as the proportion of patients reaching a defined cut‐off for ideation. We included both patient‐ and clinician‐reported instruments.

5. Problem solving

Problem solving ability was assessed either continuously, as scores on psychometric measures (for example total scores on the Problem‐Solving Inventory (PSI; Heppner 1988)), or dichotomously, as the proportion of patients with improved problems. We included both patient‐ and clinician‐reported instruments.

6. Suicide

This included both register‐recorded deaths and reports from collateral informants such as family or neighbours.

Timing of the outcome assessment

We reported outcomes for the following time points.

At the conclusion of the treatment period.

Between 0 and 6 months after the conclusion of the treatment period.

Between 6 and 12 months after the conclusion of the treatment period.

Between 12 and 24 months after the conclusion of the treatment period.

Hierarchy of outcome assessment

Where a trial measured the same outcome (e.g., depression) in two or more ways, we used the most common measure across trials in any meta‐analysis, but we also reported scores from the other measure in the text of the review.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

1. The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Review Group Specialised Register (CCDANCTR)

The Cochrane Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis Group (CCDAN) maintains two clinical trials registers at their editorial base in Bristol, UK: a references register and a studies‐based register. The CCDANCTR‐References Register contains over 39,500 reports of randomised controlled trials on depression, anxiety and neurosis. Approximately 60% of these references have been tagged to individual, coded trials. The coded trials are held in the CCDANCTR‐Studies register and records are linked between the two registers through the use of unique study ID tags. Coding of trials is based on the EU‐PSI Coding Manual. Please contact the CCDAN Trials Search Coordinator for further details.

Reports of trials for inclusion in the group's registers are collated from weekly generic searches of MEDLINE (1950 to date), EMBASE (1974 to date) and PsycINFO (1967 to date), as well as quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL).

We searched the CCDANCTR (Studies and References) database on 29 April 2015 using terms for self‐harm (condition only), as outlined in Appendix 1.

We applied no restrictions on date, language, or publication status to the search.

2. Additional electronic database searches

Sarah Stockton, librarian at the University of Oxford, conducted earlier searches (1998 to October 2013) of MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library), following the search strategy outlined in Appendix 2. As the CCDANCTR already contains relevant reports of RCTs from these databases, it was unnecessary to re‐search these. Additionally, KW searched the Australian Suicide Prevention RCT Database (Christensen 2014). KW also conducted electronic searches of ClinicalTrials.gov and the ISRCTN registry using the keywords random* AND suicide attempt* OR self$harm* to identify relevant ongoing trials.

Both the original version of this review as well as an unpublished version also incorporated searches of the following databases: SIGLE (1980 to March 2005) and SocioFile (1963 to July 2006).

We updated the search of ClinicalTrials.gov and the ISRCTN registry to 29 April 2015.

Searching other resources

Handsearching

For the original version of this review the authors hand‐searched 10 specialised journals within the fields of psychology and psychiatry, including all English language suicidology journals, as outlined in Appendix 3. As these journals are now indexed in major electronic databases, we did not repeat hand‐searching for this update.

Reference lists

We checked the reference lists of all relevant papers known to our review team as well as the reference lists of major reviews that include a focus on interventions for SH patients (Baldessarini 2003; Baldessarini 2006; Beasley 1991; Brausch 2012; Burns 2000; Cipriani 2005; Cipriani 2013; Comtois 2006; Crawford 2007a; Crawford 2007b; Daigle 2011; Daniel 2009; Dew 1987; Gould 2003; Gray 2001; Gunnell 1994; Hawton 1998; Hawton 1999; Hawton 2012; Hennen 2005; Hepp 2004; Hirsch 1982; Kapur 2010; Kliem 2010; Lester 1994; Links 2003b; Lorillard 2011a; Lorillard 2011b; Luxton 2013; Mann 2005; McMain 2007b; Milner 2015; Möller 1989; Möller, 1992; Montgomery 1995; Muehlenkamp 2006; Müller‐Oerlinghausen 2005; Nock 2007; Ougrin 2011; Ougrin 2015; Tarrier 2008b; Tondo 1997; Tondo 2000; Tondo 2001; Townsend 2001; Van der Sande 1997b).

Correspondence

We consulted trial authors and other experts in the field of suicidal behaviour to find out if they were aware of any ongoing or unpublished RCTs concerning the use of psychosocial interventions for adult SH patients.

Data collection and analysis

For details of the data collection and analysis methods used in the original version of this review, see Appendix 4.

Selection of studies

For this review update all review authors independently assessed the titles of trials identified by the systematic search for eligibility. A distinction was made between:

eligible trials that compared any psychosocial intervention with a control (e.g., treatment as usual (TAU), enhanced usual care (EUC), or other alternative forms of psychotherapy);

general treatment trials (without any control treatment).

All trials identified as potentially eligible for inclusion underwent a second screening. Pairs of review authors, working independently from one another, screened the full text of relevant trials to identify whether the trials met our inclusion criteria.

We resolved disagreements following consultation with KH. Where we could not resolve disagreements based on the information reported within the trial, or where it was unclear whether the trial satisfied our inclusion criteria, we contacted authors to provide additional clarification.

Data extraction and management

In the current update, KW and one other author (TTS, EA, DG, PH, ET or KvH) independently extracted data from included trials using a standardised extraction form. In case of disagreement, authors resolved them through consensus discussions with KH.

Data extracted from each eligible trial included participant demographics, details of the treatment and control interventions, and information on the outcome measures used to evaluate the efficacy of the intervention. We contacted study authors to obtain raw data for outcomes that were not reported in the full text of included trials.

We extracted both dichotomous and continuous outcome data from eligible trials. As the use of non‐validated psychometric scales is associated with bias, we extracted continuous data only if the psychometric scale used to measure the outcome of interest had been previously published in a peer‐reviewed journal and was not subjected to item, scoring, or other modification by the trial authors (Marshall 2000b).

We planned the following main comparisons.

CBT‐based psychotherapy versus TAU or other alternative forms of psychotherapy.

Interventions for multiple repetition of SH/probable personality disorder versus TAU or other alternative forms of psychotherapy.

Case management versus TAU or other alternative forms of psychotherapy.

Treatment adherence enhancement approaches versus TAU or other alternative forms of psychotherapy.

Mixed multimodal interventions versus TAU or other alternative forms of psychotherapy.

Remote contact interventions versus TAU or other alternative forms of psychotherapy.

Other mixed interventions versus TAU or other alternative forms of psychotherapy.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Given that highly biased trials are more likely to overestimate treatment effectiveness (Moher 1998), KW and one of TTS, EA, DG, PH, ET or KvH independently evaluated the quality of included trials by using the criteria described in Higgins 2008a. This tool encourages consideration of the following domains:

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other bias.

We judged each source of potential bias as conferring low, high or unclear risk of bias, and we incorporated a supporting quotation from the report to justify this judgment. Where the original report provided inadequate details of the randomisation, blinding, or outcome assessment procedures, we contacted authors for clarification. We resolved disagreements through discussion with KH and reported risk of bias for each included trial in the text of the review. For cluster‐randomised and cross‐over trials, we used appropriate methods of assessing bias as outlined in Higgins 2011, sections 16.3.2 and 16.4.3.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous outcomes

We summarised dichotomous outcomes, such as the number of participants engaging in a repeat SH episode and the number of deaths by suicide, using summary odds ratios (OR) and the accompanying 95% confidence interval (CI), as the OR is the most appropriate effect size statistic for summarising associations between two dichotomous groups (Fleiss 1994).

Continuous outcomes

For outcomes reported on a continuous scale, we used mean differences (MD) and accompanying 95% CI where trials employed the same outcome measure. Where studies used different scales to assess a given outcome, we used the standardised mean difference (SMD) and its accompanying 95% CI.

We only aggregated trials for the purposes of meta‐analysis if treatments were sufficiently similar. For trials that could not be included in a meta‐analysis, we have instead provided narrative descriptions of the results.

Unit of analysis issues

Zelen design trials

Trials in this area increasingly employ Zelen's method, in which investigators obtain consent after randomisation and treatment allocation. This design may lead to bias if, for example, participants allocated to one particular arm of the trial disproportionally refuse to provide consent for participation or, alternatively, if participants only provide consent provided they are allowed to cross over to the active treatment arm (Torgerson 2004). We included four trials that employed Zelen's method in this review (Carter 2005; Hatcher 2011; Hatcher 2016a; Hatcher 2015). Given the uncertainty of whether to use data for the primary outcome based on all those randomised to the trial, or only those who consented to participation, we extracted data for the primary outcome measure using both sources where possible. We also conducted sensitivity analyses by excluding these trials to investigate what impact, if any, their inclusion had on the pooled estimate of treatment effectiveness.

Cluster‐randomised trials

Cluster randomisation, for example by clinician or general practice, can lead to overestimation of the significance of a treatment effect, resulting in an inflation of the nominal type I error rate, unless there is appropriate adjustment for the effects of clustering (Donner 2002; Kerry 1998). We planned to statistically adjust for the effects of clustering following the guidance outlined in Higgins 2008b, section 16.3.4. Clustering was an issue in one included study (Bennewith 2002); however, we were unable to adjust for the effects of clustering in subsequent analyses as the study authors could not provide us with either the intercluster coefficient or the design effect.

Cross‐over trials

A primary concern with cross‐over trials is the 'carry‐over' effect, in which the effect of the intervention treatment (e.g., pharmacological, physiological, or psychological) influences the participant's response to the subsequent control condition (Elbourne 2002). As a consequence, on entry to the second phase of the trial participants may differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. This, in turn, may result in a concomitant underestimation of the effectiveness of the treatment intervention (Curtin 2002a; Curtin 2002b). One trial included in the current update used cross‐over methodology (i.e., Marasinghe 2012). To protect against the carry‐over effect, we only extracted data from the first phase of this trial, prior to cross‐over.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

Two trials in the current review included multiple treatment groups (Stewart 2009; Wei 2013). As both intervention arms in the Stewart 2009 trial investigated the effectiveness of CBT‐based psychotherapy, we combined dichotomous data from these two arms and compared them with data from the TAU arm. For outcomes reported on a continuous scale, we combined data using the formula given in Higgins 2011, section 7.7.3.8. Wei 2013 compared two different psychotherapies with TAU, namely CBT‐based psychotherapy and telephone contact. Therefore we included this trial in both categories of intervention using the data from the relevant experimental arm. As we did not combine these interventions in any meta‐analysis, we used the same TAU data for both analyses.

Studies with adjusted effect size estimates

None of the trials included in the current update calculated adjusted effect sizes. In future updates of this review, however, where trials report both unadjusted and adjusted effect sizes, we will include only unadjusted effect sizes.

Dealing with missing data

We as review authors did not impute missing data, as we considered that the bias that would be introduced by doing this would have outweighed any benefit (in terms of increased statistical power) that may have been gained by the inclusion of imputed data. However, where authors omitted standard deviations (SD) for continuous measures, we estimated these using the method described in Townsend 2001.

Dichotomous data

Although many authors conducted their own intention‐to‐treat analyses, few presented intention‐to‐treat analyses as defined by Higgins 2008b. Therefore, we based outcome analyses for both dichotomous and continuous data on all information available on trial participants. For dichotomous outcomes, we included data on only those participants whose results were known, using as the denominator the total number of participants with data for the particular outcome of interest, as recommended (Higgins 2008b).

Continuous data

For continuous outcomes, we included data only on observed cases.

Missing data

Where data on outcomes of interest were incomplete or excluded from the text of the trial, we contacted authors to request further information.

Assessment of heterogeneity

It is possible to assess between‐study heterogeneity using either the Chi2 or I2 statistic. In this review, however, we used only the I2 statistic to determine heterogeneity, as Higgins 2003 considers this to be more reliable. The I2 statistic indicates the percentage of between‐study variation due to chance and can take any value from 0% to 100% (Higgins 2003). We used the following values to denote unimportant, moderate, substantial, and considerable heterogeneity, respectively: 0% to 40%, 30% to 60%, 50% to 90%, and 75% to 100% as per the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Deeks 2008, section 9.5.2). Where we found substantial levels of heterogeneity (i.e., ≥ 75%), we explored possible reasons. We also planned to investigate heterogeneity even when the I2 statistic was lower than 75% but either the direction or magnitude of a trial effect size was clearly discrepant from that of other trials included in the meta‐analysis (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity section for further information on these analyses).

We also report heterogeneity in the results section but only when we observed substantial levels, as indicated by an I2 statistic of 75% or greater.

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting bias occurs when the direction and significance of a particular trial's results influence the decision to publish a report on it (Egger 1997). Research suggests, for example, that trials with statistically significant findings are more likely to be submitted and subsequently accepted for publication (Hopewell 2009), leading to possible overestimation of the true treatment effect. To assess whether trials included in any meta‐analysis were affected by reporting bias, we entered data into a funnel plot but only, as recommended, when a meta‐analysis included results of at least 10 trials. Where evidence of any small‐study effects were identified, we explored reasons for funnel plot asymmetry, including the presence of publication bias (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

For the purposes of meta‐analysis, we calculated the pooled OR and accompanying 95% CI using the random‐effects model, as this is the most appropriate model for incorporating heterogeneity between trials (Deeks 2008, section 9.5.4). Specifically, we used the Mantel‐Haenszel method for dichotomous data and the inverted variance method for continuous data. However, we also undertook a fixed‐effect analysis to investigate the potential effect of method choice on the estimates of treatment effect. We descriptively report any material differences in ORs between these two methods in the text of the review. All analyses were conducted in Review Manager, version 5 (RevMan 2014).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses

In the original version of this review, we planned to undertake subgroup analyses by repeater status (i.e., history of multiple episodes of SH vs first known episode of SH) and gender but found there were insufficient data. Consequently, in this update we only undertook a priori subgroup analyses by sex or repeater status where there were sufficient data to do so.

Investigation of heterogeneity

Where meta‐analyses were associated with substantial levels of between‐study heterogeneity (i.e., as indicated by an I2 statistic ≥ 75%), KH and KW first independently triple‐checked the data to ensure that the review team had correctly entered the data. Assuming this was the case, we investigated the source of heterogeneity by visually inspecting the forest plot and removing each trial that had a very different result from the general pattern of the others until homogeneity was restored as indicted by an I2 statistic < 75%. We have reported the results of this sensitivity analysis in the text of the review alongside hypotheses regarding the likely causes of heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

We undertook sensitivity analyses, where appropriate, as outlined below.

Trial/s that used Zelen's method of randomisation (see Unit of analysis issues section).

Trial/s that contributed substantial levels of between‐study heterogeneity (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity section).

Trial/s that included some adolescent participants.

Trial/s that specifically recruited individuals diagnosed with borderline personality disorder.

Summary of findings table

We prepared a 'Summary of findings' table for the primary outcome measure, repetition of SH, following recommendations outlined in Schünemann 2008a, section 11.5. This table provides information concerning the overall quality of evidence from each included trial. We prepared the 'Summary of findings' table using GRADEpro software (GRADE profiler). We assessed quality of the evidence following recommendations in Schünemann 2008b, section 12.2.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

In this update, the search strategy outlined in Appendix 1 and Appendix 2 yielded a total of 23,725 citations. We identified a further 10 trials that were ongoing at the time of the systematic search through correspondence and discussion with researchers in the field. All have subsequently been published.

In consultation with CCDAN, we divided the original review (Hawton 1998; Hawton 1999) into three separate reviews: the present review focuses on psychosocial interventions for adults, a second review deals with pharmacological interventions for adults (Hawton 2015b), and the third assesses interventions for children and adolescents (Hawton 2015a). Nine of the additional 10 trials evaluated psychosocial interventions for adults, and were therefore included in the present update. The remaining trial evaluated an intervention for children and adolescents; this is included in the related relevant review (i.e., Hawton 2015a).

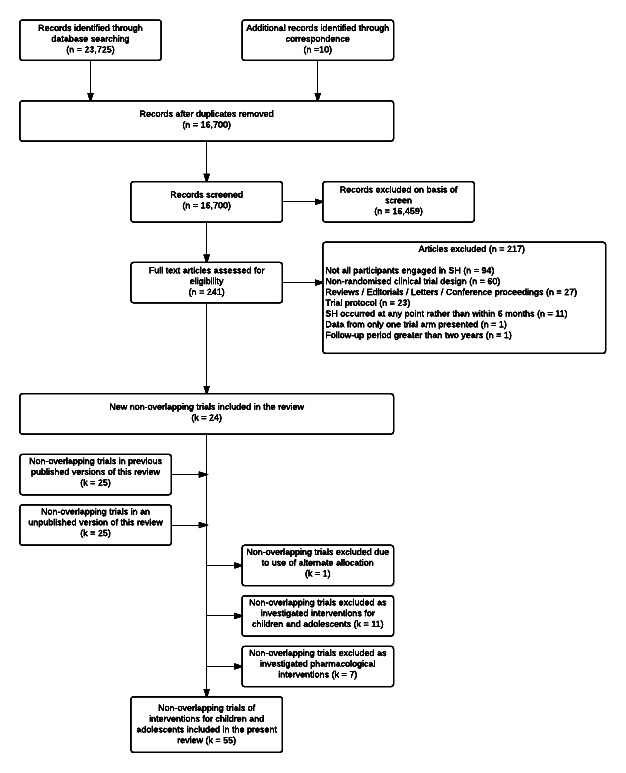

After deduplication, the initial number of citations decreased to 16,700. Of these, we excluded 16,459 after screening the titles and abstracts and a further 217 after reviewing the full texts (Figure 1).

1.

Search flow diagram of included and excluded studies for the 2014 update.

Included studies

In the previous versions of this review (Hawton 1998; Hawton 1999; NICE 2011), we included 36 trials of psychosocial interventions for adults following SH (Allard 1992; Bateman 2009; Bennewith 2002; Brown 2005; Carter 2005; Cedereke 2002; Clarke 2002; Dubois 1999; Evans 1999a; Evans 1999b; Fleischmann 2008; Gibbons 1978; Gratz 2006; Guthrie 2001; Hawton 1981; Hawton 1987a; Liberman 1981; Linehan 1991; Linehan 2006; McLeavey 1994; McMain 2009; Morgan 1993; Patsiokas 1985; Salkovskis 1990; Slee 2008; Stewart 2009; Torhorst 1987; Torhorst 1988; Turner 2000; Tyrer 2003; Vaiva 2006; Van der Sande 1997a; Van Heeringen 1995; Waterhouse 1990; Weinberg 2006; Welu 1977). The present update included information from an additional 19 trials (Beautrais 2010; Crawford 2010; Davidson 2014; Gratz 2014; Harned 2014; Hassanian‐Moghaddam 2011; Hatcher 2016a; Hatcher 2015; Hatcher 2011; Husain 2014; Hvid 2011; Kapur 2013a; Kawanishi 2014; Marasinghe 2012; McAuliffe 2014; Morthorst 2012; Priebe 2012; Tapolaa 2010; Wei 2013). The present review therefore included 55 non‐overlapping trials. Five further follow‐up studies (i.e., Bertolote 2010; Hassanzadeh 2010; McMain 2012, Vijayakumar 2011 and Xu 2012) provide additional data for two of these trials (Fleischmann 2008; McMain 2009).

We obtained unpublished data from corresponding authors from a further 36 trials (Bateman 2009; Beautrais 2010; Bennewith 2002; Brown 2005; Carter 2005; Cedereke 2002; Clarke 2002; Crawford 2010; Davidson 2014; Dubois 1999; Fleischmann 2008; Gratz 2006; Gratz 2014; Guthrie 2001; Harned 2014; Hassanian‐Moghaddam 2011; Hatcher 2016a; Hatcher 2015; Hatcher 2011; Husain 2014; Hvid 2011; Linehan 1991; Linehan 2006; Marasinghe 2012; McAuliffe 2014; McMain 2009; Patsiokas 1985; Priebe 2012; Slee 2008; Stewart 2009; Tapolaa 2010; Turner 2000; Tyrer 2003; Vaiva 2006; Wei 2013; Weinberg 2006).

We also identified 16 ongoing trials of psychosocial interventions following SH in adults (see Characteristics of ongoing studies section for further information on these trials).

Design

Study authors described all 55 independent trials as randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Most (number of studies k = 49; 89.1%) employed a simple randomisation procedure based on individual allocation to the intervention and control groups. Zelen's post‐randomisation consent design was used in four trials (Carter 2005; Hatcher 2016a; Hatcher 2015; Hatcher 2011), a cluster‐randomisation procedure in one (Bennewith 2002), and a matched pair randomisation procedure in another (Cedereke 2002).

Participants

The included trials comprised a total of 17,699 participants. All had engaged in at least one episode of SH in the six months prior to randomisation.

Participant characteristics

In the 39 trials that recorded information on age, the average age of participants at randomisation was 30.9 years (SD 4.6). Twenty trials included a small number of adolescent participants (i.e., under 18 years of age at randomisation) (Carter 2005; Dubois 1999; Evans 1999b; Gibbons 1978; Hassanian‐Moghaddam 2011; Hatcher 2016a; Hatcher 2015; Hatcher 2011; Hawton 1987a; Husain 2014; Hvid 2011; Marasinghe 2012; McLeavey 1994; Morthorst 2012; Priebe 2012; Salkovskis 1990; Slee 2008; Van der Sande 1997a; Van Heeringen 1995; Wei 2013). However, investigators did not record the precise number in any of them. As the majority of participants in these trials were adults, we included them in the present review rather than in the related review specific to interventions for children and adolescents (i.e., Hawton 2015a). The majority of the sample was female in the 46 trials that recorded information on sex (k = 46; mean 69.2%), reflecting the typical pattern for SH (Hawton 2008).

Diagnosis

In all trials, a recent episode of SH was a requirement for trial entry. SH includes intentional acts of self‐harm (i.e., self‐poisoning or self‐injury) and not acts such as recreational use of drugs that may result in accidental harm.

A history of multiple episodes of SH was a requirement for participation in 13 trials (Evans 1999b; Gratz 2006; Gratz 2014; Harned 2014; Liberman 1981; Linehan 1991; Linehan 2006; McMain 2009; Priebe 2012; Salkovskis 1990; Torhorst 1988; Tyrer 2003; Weinberg 2006). For an additional 28 trials, over half the sample had a history of multiple episodes of SH (Allard 1992; Bateman 2009; Beautrais 2010; Bennewith 2002; Brown 2005; Carter 2005; Cedereke 2002; Crawford 2010; Davidson 2014; Dubois 1999; Gibbons 1978; Guthrie 2001; Hatcher 2016a; Hatcher 2015; Hatcher 2011; Husain 2014; Kapur 2013a; Marasinghe 2012; McAuliffe 2014; McLeavey 1994; Morthorst 2012; Patsiokas 1985; Slee 2008; Stewart 2009; Tapolaa 2010; Turner 2000; Wei 2013; Welu 1977). In four further trials, just under half of the sample had a history of multiple episodes of SH (Clarke 2002: 47.0%; Evans 1999a: 47.6%; Kawanishi 2014: 49.2%; Van der Sande 1997a: 46.3%). We present the proportion with a prior history of SH in the remaining eight trials in Table 8. Morgan 1993 excluded those with a history of multiple episodes of SH from participation, whilst Torhorst 1987 provided no information on the proportion of the sample with a history of multiple episodes of SH.

1. Proportion of the sample with a history of self‐harm prior to the index attempt.

| Reference |

History of SH prior to index episode (%) |

| Fleischmann 2008 | 21.1 |

| Hawton 1981 | 32.3 |

| Hawton 1987a | 31.2 |

| Hassanian‐Moghaddam 2011 | 34.2 |

| Hvid 2011 | 38.3 |

| Vaiva 2006 | 8.9a |

| Van Heeringen 1995 | 29.8 |

| Waterhouse 1990 | 36.4 |

aProportion with more than four previous episodes of SH over the three‐year period preceding trial entry.

In around half of the included trials (k = 25; 45.4%), the authors stated either within the trial report or through correspondence that they included participants irrespective of whether or not the episode of SH involved suicidal intent (Bateman 2009; Beautrais 2010; Bennewith 2002; Clarke 2002; Davidson 2014; Fleischmann 2008; Harned 2014; Hatcher 2016a; Hatcher 2015; Hatcher 2011; Hawton 1981; Hawton 1987a; Hvid 2011; Kapur 2013a; Liberman 1981; Linehan 2006; McAuliffe 2014; McMain 2009; Patsiokas 1985; Slee 2008; Tapolaa 2010; Torhorst 1987; Turner 2000; Tyrer 2003; Van Heeringen 1995; Waterhouse 1990). Seven trials included participants following a 'suicide attempt' (i.e., suggestive of evidence of suicidal intent) (Allard 1992; Cedereke 2002; Morthorst 2012; Salkovskis 1990; Torhorst 1988; Van der Sande 1997a; Wei 2013). A further five trials included participants only if there had been evidence of suicidal intent (Brown 2005; Kawanishi 2014; Marasinghe 2012; Stewart 2009; Welu 1977), whilst in an additional two, the majority of participants (76.5% and 74.0% respectively) expressed a wish to die (Guthrie 2001; Husain 2014). Gratz 2014 included participants only if there was no evidence of suicidal intent, whilst only 2.0% in one trial expressed a wish to die (Vaiva 2006). Thirteen trials did not report information on suicidal intent (Carter 2005; Crawford 2010; Dubois 1999; Evans 1999a; Evans 1999b; Gibbons 1978; Gratz 2006; Hassanian‐Moghaddam 2011; Linehan 1991; McLeavey 1994; Morgan 1993; Priebe 2012; Weinberg 2006).

Twenty‐five trials did not report information on the methods of SH for the index episode (Allard 1992; Bateman 2009; Cedereke 2002; Davidson 2014; Dubois 1999; Evans 1999b; Fleischmann 2008; Gratz 2006; Gratz 2014; Hvid 2011; Kapur 2013a; Linehan 1991; Linehan 2006; Marasinghe 2012; McMain 2009; Morthorst 2012; Patsiokas 1985; Priebe 2012; Salkovskis 1990; Stewart 2009; Tapolaa 2010; Turner 2000; Tyrer 2003; Wei 2013; Weinberg 2006). One trial provided information on the methods used in all episodes of SH (including the index episode) in the two years preceding trial entry (Liberman 1981). A total of 55.7% of these episodes involved self‐poisoning and 44.3% involved self‐injury. One additional trial provided information on methods used in the three months prior to trial entry with a total of 61 (67.8%) participants in this trial engaging in self‐injury at least once over this period; however, investigators did not specify the methods that the remaining 29 participants used for SH (Slee 2008). We present methods of SH for the remaining 28 trials in Table 9. In these trials, the majority of participants had engaged in self‐poisoning (k = 28; 79.9%). Two trials included only those who engaged in self‐injury (Harned 2014; Welu 1977), whilst in a further trial the majority of participants (75.6%) had engaged in self‐poisoning using pesticides (Husain 2014).

2. Methods used for the index episode of self‐harm in included studies.

| Reference | Methoda | ||||

|

Self poisoning (any) n (%) |

Self poisoning (pesticides) n (%) |

Self injury (any) n (%) |

Combined self‐poisoning and self‐injury n (%) |

Unspecified n (%) |

|

| Beautrais 2010b | 250 (76.7) | — | 64 (19.6) | — | 15 (4.6) |

| Bennewith 2002 | 7,733 (89.7) | — | 158 (8.2) | — | 41 (2.1) |

| Brown 2005 | 70 (58.3) | — | 33 (27.5) | — | 17 (14.2) |

| Carter 2005 | 772 (100) | — | — | — | — |

| Clarke 2002b | 442 (94.6) | — | 25 (5.3) | 8 (1.7) | — |

| Crawford 2010c | 74 (71.8) | — | 25 (24.3) | — | — |

| Evans 1999a | 808 (97.7) | — | — | — | 19 (2.3) |

| Gibbons 1978 | 400 (100) | — | — | — | — |

| Guthrie 2001 | 119 (100) | — | — | — | — |

| Harned 2014 | — | — | 26 (100) | — | — |

| Hassanian‐Moghaddam 2011 | 2300 (100) | — | — | — | — |

| Hatcher 2011 | 471 (85.3) | — | 81 (14.7) | — | — |

| Hatcher 2015 | 532 (77.8) | — | 125 (18.3) | 27 (3.9) | — |

| Hatcher 2016a | 115 (68.9) | — | 41 (24.5) | 11 (6.6) | — |

| Hawton 1981 | 96 (100) | — | — | — | |

| Hawton 1987a | 80 (100) | — | — | — | |

| Husain 2014b | 65 (29.4) | 167 (75.6) | 4 (1.8) | — | — |

| Kawanishi 2014b | 707 (77.3) | — | 332 (36.3) | — | 42 (4.6) |

| McAuliffe 2014d | 161 (37.2) | — | 57 (13.2) | — | 4 (0.9) |

| Morgan 1993 | 207 (97.6) | — | — | — | 5 (2.4) |

| McLeavey 1994 | 39 (100) | — | — | — | — |

| Torhorst 1987 | 141 (100) | — | — | — | — |

| Torhorst 1988 | 80 (100) | — | — | — | — |

| Vaiva 2006 | 605 (100) | — | — | — | — |

| Van der Sande 1997a | 232 (84.7) | — | — | — | 42 (15.3) |

| Van Heeringen 1995 | 463 (89.7) | — | — | — | 53 (10.3) |

| Waterhouse 1990 | 77 (100) | — | — | — | — |

| Welu 1977 | — | 120 (100) | — | — | |

aRefers to the methods used for the index episode. b Percentages are greater than 100% because participants may have used multiple methods. c The remaining four (3.9%) participants used multiple, unspecified methods. d Methods of self‐harm for the remaining 211 (48.7%) participants were not provided.

Comorbidities

We present information on current psychiatric diagnoses for all 55 trials in Table 10. Eight trials focused specifically on participants diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (Bateman 2009; Gratz 2006; Gratz 2014; Linehan 1991; Linehan 2006; McMain 2009; Turner 2000; Weinberg 2006), three focused on participants diagnosed with any personality disorder (Davidson 2014; Evans 1999b; Priebe 2012), one focused specifically on participants diagnosed with alcohol use (Crawford 2010), and one focused on participants with comorbid post‐traumatic stress disorder and borderline personality disorder (Harned 2014).

3. Major categories of psychiatric diagnoses in included studies.

| Reference | Psychiatric diagnosisa | |||||||||||

|

Major depression n (%) |

Any other mood disorder n (%) |

Any anxiety disorder n (%) |

Any psychotic disorder n (%) |

Post‐traumatic stress n (%) |

Any eating disorder n (%) |

Alcohol use disorder/dependence n (%) |

Drug use disorder/dependence n (%) |

Substance use disorder/dependence n (%) |

Adjustment disorder n (%) |

Borderline personality disorder n (%) |

Any other personality disorder n (%) | |

| Allard 1992 | 130(86.7) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 79 (52.7) | — | — | 68 (45.3) |

| Bateman 2009 | 75 (56.0) | 103 (76.9) | 82 (61.2) | 19 (14.2) | 37 (27.6) | — | — | 72 (53.7) | — | 134 (100) | b | |

| Beautrais 2010 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Bennewith 2002 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Brown 2005 | 92 (77.0) | — | — | — | — | — | 36 (30.0) | 48 (40.0) | 82 (68.0) | — | — | — |

| Carter 2005 | No information on specific categories of psychiatric diagnosis reportedc | |||||||||||

| Cedereke 2002d | — | 91 (42.1) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 62 (28.7) | — | — |

| Clarke 2002 | — | 98 (56.0)e | 60 (34.0)e | 12 (3.0) | — | — | 26 (41.0)f | — | — | — | — | |

| Crawford 2010 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Davidson 2014 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 17 (85.0) | 20 (100) |

| Dubois 1999 | — | — | — | 43 (42.1) | — | — | — | — | 13 (12.7) | — | — | — |

| Evans 1999a | 707/827 (85.5) diagnosed with any major psychiatric disorder | |||||||||||

| Evans 1999b | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Fleischmann 2008 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Gibbons 1978 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Gratz 2006 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 22 (100) | — |

| Gratz 2014 | — | 31 (50.0) | 38 (61.3) | — | 22 (35.5) | 8 (12.9) | — | — | 1 (1.6) | — | 62 (100) | b |

| Guthrie 2001 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Harned 2014 | — | 22 (83.3) | 23 (87.5) | — | — | 3 (12.5) | — | — | 11 (41.7) | — | 26 (100) | 16 (62.5) |

| Hassanian‐Moghaddam 2011 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Hatcher 2011 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Hatcher 2015 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Hatcher 2016a | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Hawton 1981 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Hawton 1987a | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Husain 2014 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Hvid 2011 | No information on specific categories of psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Kapur 2013a | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Kawanishi 2014g | — | 425(46.5) | — | 179(19.6) | — | — | — | — | 45 (4.9) | 191 (20.9) | — | — |

| Liberman 1981 | — | 24 (100) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | h |

| Linehan 1991 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 44 (100) | — |

| Linehan 2006 | 73 (72.3) | — | 79 (78.2) | — | 50 (49.5) | 24 (23.8) | — | — | 30 (29.7) | — | 101(100) | b |

| Marasinghe 2012 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| McAuliffe 2014 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| McLeavey 1994 | — | 9 (23.1) | 1 (2.5) | — | — | — | 5 (12.8) | — | — | — | — | 6 (15.4) |

| McMain 2009 | 88 (48.9) | — | 135 (75.0) | — | 71 (37.4) | 24 (13.3) | — | — | 17 (9.4) | — | 180(100) | b |

| Morgan 1993 | — | 53 (25.0) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | |

| Morthorst 2012 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reportedi | |||||||||||

| Patsiokas 1985 | No information on specific categories of psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Priebe 2012j | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 80 (100) |

| Salkovskis 1990 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Slee 2008 | — | 80 (88.9) | 50 (55.6) | — | — | 15 (16.7) | — | — | 15 (16.7) | — | — | — |

| Stewart 2009 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Tapolaa 2010 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Torhorst 1987 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Torhorst 1988 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Turner 2000 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 24 (100) | — |

| Tyrer 2003 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 471(98.1) |

| Vaiva 2006 | No information on specific categories of psychiatric diagnosis reportedk | |||||||||||

| Van der Sande 1997a | — | 86 (31.4) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 40 (14.6) | — | — |

| Van Heeringen 1995 | — | 76 (14.7) | 14 (2.7) | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — |

| Waterhouse 1990 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

| Wei 2013 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reportedl | |||||||||||

| Weinberg 2006 | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | — | 30 (100) | — |

| Welu 1977 | No information on psychiatric diagnosis reported | |||||||||||

a All diagnoses represent current rather than lifetime diagnoses. b As participants could be diagnosed with more than one axis II diagnosis, the absolute number of participants diagnosed with any other personality disorder in this trial is unclear. c Median number (interquartile range) of psychiatric diagnoses in the both the intervention and control groups was 2 (1‐3). Information on specific categories of psychiatric diagnosis; however, were not reported. d A total of 47/216 (21.7%) of the sample were diagnosed with any psychiatric disorder other than a mood or adjustment disorder. e Diagnosed with a possible psychiatric disorder according to cut‐off scores on the Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). Out of a total of 176 participants with complete ratings on this instrument. f Diagnosed with problematic alcohol use according to cut‐off scores on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT). Out of a total of 63 participants with complete ratings on this instrument. g An additional 73/914 (8.0%) were diagnosed with any other major psychiatric disorder. h The authors state that "[m]ost patients would have been given personality disorder designations. . . including histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, avoidant, and dependent types" (p.1127). The absolute number of participants diagnosed with any one of these personality disorders in this trial is, however, unclear. i A total of 14/243 (5.8%) participants had been admitted to a psychiatric inpatient ward in the four weeks prior to the index suicide attempt. These patients were therefore likely to have been diagnosed with a current major psychiatric illness. j Mean (standard deviation (SD)) number of axis I psychiatric disorders was 8.0 (3.1) (n = 63) and mean (SD) number of axis II diagnoses was 3.5 (1.6) (n = 80). k A total of 100/459 (21.8%) of participants had, however, been referred for psychiatric treatment at the time of the index suicide attempt. These patients were therefore likely to have been diagnosed with a current major psychiatric illness. l A total of 166/239 (69.4%) were, however, diagnosed with a major psychiatric illness according to DSM‐IV‐TR criteria.

Details on comorbid diagnoses were not reported in the majority of trials (k = 49; 89.1%) (Allard 1992; Bateman 2009; Beautrais 2010; Bennewith 2002; Cedereke 2002; Clarke 2002; Crawford 2010; Dubois 1999; Evans 1999a; Evans 1999b; Fleischmann 2008; Gibbons 1978; Gratz 2006; Guthrie 2001; Harned 2014; Hassanian‐Moghaddam 2011; Hatcher 2016a; Hatcher 2015; Hatcher 2011; Hawton 1981; Hawton 1987a; Husain 2014; Hvid 2011; Kapur 2013a; Kawanishi 2014; Liberman 1981; Linehan 1991; Linehan 2006; Marasinghe 2012; McAuliffe 2014; McLeavey 1994; Morgan 1993; Morthorst 2012; Patsiokas 1985; Priebe 2012; Salkovskis 1990; Stewart 2009; Tapolaa 2010; Torhorst 1987; Torhorst 1988; Turner 2000; Tyrer 2003; Vaiva 2006; Van der Sande 1997a; Van Heeringen 1995; Waterhouse 1990; Wei 2013; Weinberg 2006; Welu 1977). In Brown 2005, most participants (85.0%) were diagnosed with more than one psychiatric disorder; however, the authors did not provide information on specific diagnoses. In an additional three trials (Carter 2005; McMain 2009; Slee 2008), the median number of psychiatric diagnoses was greater than two, suggesting that participants in these trials were also diagnosed with more than one psychiatric disorder; however, none of the three reported further information on specific diagnoses. In one trial, 45.0% of the participants were diagnosed with comorbid personality disorder and substance misuse (Davidson 2014), whilst in another, just under half of the sample (45.9%) had a comorbid personality diagnosis (Gratz 2014).

Setting

Of the 55 independent RCTs included in this review, most took place in the United Kingdom (k = 17) or the United States (k = 12), followed by New Zealand (k = 4), Australia (k = 2), Canada (k = 2), Denmark (k = 2), France (k = 2), Germany (k = 2), the Netherlands (k = 2), and one each from Belgium, China, Finland, Iran, Japan, Pakistan, the Republic of Ireland, Sri Lanka, and Sweden. One trial was a multicentre study conducted in a number of countries.

Interventions

The trials included in this review investigated the effectiveness of various forms of psychosocial intervention.

CBT‐based psychotherapy versus TAU (k = 18: Brown 2005; Davidson 2014; Dubois 1999; Evans 1999b; Gibbons 1978; Guthrie 2001; Hatcher 2011; Hawton 1987a; Husain 2014; McAuliffe 2014; Patsiokas 1985; Salkovskis 1990; Slee 2008; Stewart 2009; Tapolaa 2010; Tyrer 2003; Wei 2013; Weinberg 2006).

Interventions for multiple repetition of SH versus TAU (k = 6: Bateman 2009; Gratz 2006; Gratz 2014; Linehan 1991; McMain 2009; Priebe 2012) or other alternative forms of psychotherapy (k = 3: Harned 2014; Linehan 2006; Turner 2000).

Case management versus TAU (k = 4: Clarke 2002; Hvid 2011; Kawanishi 2014; Morthorst 2012).

Treatment adherence enhancement approaches versus TAU (k = 1: Van Heeringen 1995) or other alternative forms of psychotherapy (k = 1: Torhorst 1987).

Mixed multimodal interventions versus TAU (k = 2: Hatcher 2016a; Hatcher 2015).

Remote contact interventions versus TAU (k = 11: Beautrais 2010; Bennewith 2002; Carter 2005; Cedereke 2002; Evans 1999a; Hassanian‐Moghaddam 2011; Kapur 2013a; Marasinghe 2012; Morgan 1993; Vaiva 2006; Wei 2013).

Other mixed interventions versus TAU (k = 5: Allard 1992; Crawford 2010; Fleischmann 2008; Van der Sande 1997a; Welu 1977) or other alternative forms of psychotherapy (k = 5: Hawton 1981; Liberman 1981; McLeavey 1994; Torhorst 1988; Waterhouse 1990).

Outcomes