Abstract

Aim:

To test the effectiveness of a ketogenic diet and virtual coaching intervention in controlling markers of diabetes care and healthcare utilization.

Materials and Methods:

Using a difference-in-differences analysis with a waiting list control group—a quasi-experimental methodology—we estimated the 5-month change in HbA1c, body mass index, blood pressure, prescription medication use and costs, as well as healthcare utilization. The analysis included 590 patients with diabetes who were also overweight or obese, and who regularly utilize the Veterans Health Administration (VA) for healthcare. We used data from VA electronic health records from 2018 to 2020.

Results:

The ketogenic diet and virtual coaching intervention was associated with significant reductions in HbA1c (−0.69 [95% CI −1.02, −0.36]), diabetes medication fills (−0.38, [−0.49, −0.26]), body mass index (−1.07, [−1.95, −0.19]), diastolic blood pressure levels (−1.43, [−2.72, −0.14]), outpatient visits (−0.36, [−0.70, −0.02]) and prescription drug costs (−34.54 [−48.56, −20.53]). We found no significant change in emergency department visits (−0.02 [−0.05, 0.01]) or inpatient admissions (−0.01 [−0.02, 0.01]).

Conclusions:

This real-world assessment of a virtual coaching and diet programme shows that such an intervention offers short-term benefits on markers of diabetes care and healthcare utilization in patients with diabetes.

Keywords: dietary intervention, health economics, type 2 diabetes, weight control

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of diabetes is disproportionately high among US veterans. Approximately 25% of veterans have a diabetes diagnosis in comparison with 9% of the general population.1 The Veterans Health Administration (VA) incurs more than $200 million in outpatient expenditure and more than $1 billion in inpatient expenditure for veterans with diabetes.2 In light of these serious health and financial consequences, the VA recently undertook a test of effectiveness of a ketogenic diet and virtual coaching (KD-VC) intervention among patients with diabetes.

Lifestyle interventions and medical nutrition therapy are corner-stones of non-pharmacological treatment for patients with diabetes. In particular, some virtual diet interventions with coaching components have been shown to be effective in achieving short-term weight loss and improving glucose control,3–11 although less is known about the impact of coaching programmes with a specific ketogenic (keto) diet component.12 One virtual diabetes coaching programme with a keto diet component has been previously evaluated. Virta Health (San Francisco, CA) conducted a non-randomized clinical trial testing the impact of a combined individualized keto diet and telehealth medical care model on overweight and obese adults with diabetes relative to a usual care arm. This programme’s coaching component also includes an emphasis on diabetes medication management. Over a 2-year intervention period, HbA1c declined by 0.9% and 62% of participants reduced or eliminated insulin use.13–15 However, these results remain subject to bias because of the non-randomized design and the absence of a similarly motivated comparison group.

Furthermore, while the short-term clinical benefits of keto and other non-keto virtual diet interventions are promising for diabetes, there is little information on such programmes regarding healthcare utilization or costs. Increasing use of telehealth interventions may help to unburden healthcare systems of some care and treatment costs. Understanding whether virtual care interventions improve utilization and cost outcomes in diabetes is critical for healthcare system resource allocation.

Using a quasi-experimental approach, the current study was designed to estimate the effectiveness of the KD-VC programme among veterans with diabetes enrolled in VA healthcare. We conducted a difference-in-differences analysis with a waiting list control group to answer the following question: What is the impact of the KD-VC programme over 5 months on (a) markers of glucose control and metabolic health, (b) outpatient and inpatient utilization, and (c) prescription drug utilization and costs?

2 |. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 |. Study design

We used a difference-in-differences approach to estimate the impact of the KD-VC programme on key diabetes outcomes using VA electronic health records from 2018 to 2020. A difference-in-differences approach uses observational data to compare changes in outcomes between a treatment and control group, both before and after an intervention is delivered.16–18 The study was reviewed and considered exempt research by the VA Boston Healthcare System Institutional Review Board.

2.2 |. Virta telehealth and keto coaching intervention

The Virta Health programme is an online telehealth and coaching intervention in which participants are counselled to adhere to a keto diet.13 The programme also includes education components and management of medications for patients with diabetes. In April 2019, VA initiated a pilot programme in which 454 veterans were given access to the Virta KD-VC programme on a first-come-first-serve basis until enrolment capacity was reached in October 2019. An additional 867 veterans who wished to enrol after capacity was reached did not have the opportunity to do so. For the purposes of this report, this group is referred to as the control group but is equivalent to a waiting list control group because of motivation comparable with the treatment group.

Veterans were required to meet several inclusion criteria. These included enrolment in medical benefits through VA, a current diabetes diagnosis (defined as HbA1c greater than or equal to 6.5%) and at least one current diabetes medication other than, or in addition to, metformin. The latter criterion was designed to exclude enrolment by patients taking metformin alone for diabetes prevention or other non-diabetes indications. Exclusion criteria included active duty status, veterans living abroad, and a list of special conditions including, but not limited to, type 1 diabetes, end stage renal disease, heart failure, active chemotherapy treatment and others. All applicants completed an initial screening based on self-report. Treatment patients were required to provide VA benefit cards, HbA1c results and prescriptions for physician validation of inclusion criteria. Control group participants did not undergo physician validation of self-reported data.

2.3 |. Data

We used data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse, which contains electronic health records and information on sociodemographic characteristics, chronic conditions, medications and vital signs, as well as VA outpatient, inpatient and emergency department utilization. Data on diabetes medication costs to the VA were provided by VA’s Pharmacy Benefits Management Services. Data were extracted from September 2018 to August 2020.

2.4 |. Matching and screening

Virta Health collected information on name, address, social security number and telephone number for all patients. These data were provided to the research team and used to match to VA patient records for analysis. Because the treatment and control groups underwent different screening processes, we imposed uniform treatment inclusion criteria using VA data to create comparable treatment and control samples with regard to underlying health status and motivation. Specifically, we screened VA data on all participants for a diabetes diagnosis within a year of application date, at least one active non-metformin diabetes medication and an HbA1c level greater than or equal to 6.5% within the prior 6 months.

2.5 |. Measurements

2.5.1 |. Outcome variables

We identified 10 outcomes of interest related to diabetes care: HbA1c, body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), emergency department (ED) visits, outpatient visits, inpatient admissions, number of insulin prescriptions, number of diabetes prescriptions and the costs of diabetes prescriptions. Outcomes were captured up to 5 months postapplication date. This window was selected because, at 6 months, patients from the waiting list began to enrol in the intervention and the COVID-19 pandemic began to impact utilization rates in the control group. When subjects had multiple observations per month, monthly averages were calculated, dropping observations that were greater than three standard deviations from the monthly subject-specific average.

2.5.2 |. Primary independent variable

The KD-VC programme effect is the primary covariate of interest, and is the interaction term between an indicator variable for treatment status (coded as 1 if treated and 0 if control) and an indicator variable for postapplication time period (coded as 1 for post-KD-VC programme application months and 0 for preapplication months). Because control participants do not have a treatment date, we used the application month as the relevant postperiod for ease of comparison.

2.5.3 |. Covariates

Sociodemographic characteristics included gender, age, race/ethnicity and urban/rural residence. Also included were Charlson co-morbidity index19 and an indicator for VA enrolment priority status (a proxy for socioeconomic status). As is standard in difference-in-differences analyses, we also include month-specific time indicators (fixed effects).

2.6 |. Statistical analysis

We first conducted a descriptive analysis of baseline characteristics of treatment and control participants before their KD-VC programme application date using t tests for binary or continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. We then estimated a difference-in-differences equation of the following multivariate linear specification:

| (1) |

where yit is one of eight outcomes for individual, i, in month, t; β3 is the change in outcome associated with receiving the KD-VC programme, Ti, in the postperiod, Postit; Xi are covariates and γt are month fixed effects. Huber-White robust standard errors were calculated at the patient level.20

Causal inference in the difference-in-differences framework relies on the assumption that the trends in the outcomes evolved similarly between treatment and control groups in the preapplication period and would have continued to evolve similarly in the absence of the treatment. This parallel-trends assumption allows inferences that the difference-in-differences estimates (β3) are attributable to the KD-VC programme, and not to other factors that may have influenced treatment uptake. To test the parallel trends assumption, we estimated regressions of the outcomes with interactions between the relative month indicator and treatment indicator for each outcome. Joint chi-squared tests of the interactions failed to reject zero differences in the trends of these outcomes between the control and treatment groups in the preapplication period.

As an additional robustness check, we examined the differential missingness of data between treatment and control patients for five outcomes: HbA1c, BMI, SBP/DBP (combined), ED visits and outpatient visits. This robustness check is designed to detect for any documentation bias in the electronic health record specifically related to treatment. We created an indicator for outcome-specific missingness (1 if missing, 0 if non-missing) and regressed this new variable on the variables in Equation (1). In this specification, a positive value of β3 would indicate the percentage point probability that treatment status is associated with outcome-specific missingness. For outcomes for which there was evidence of differential missingness, we ran weighted regressions, where weights were calculated as the inverse probability of having an observed outcome in the postapplication period.21

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Matching and screening processes

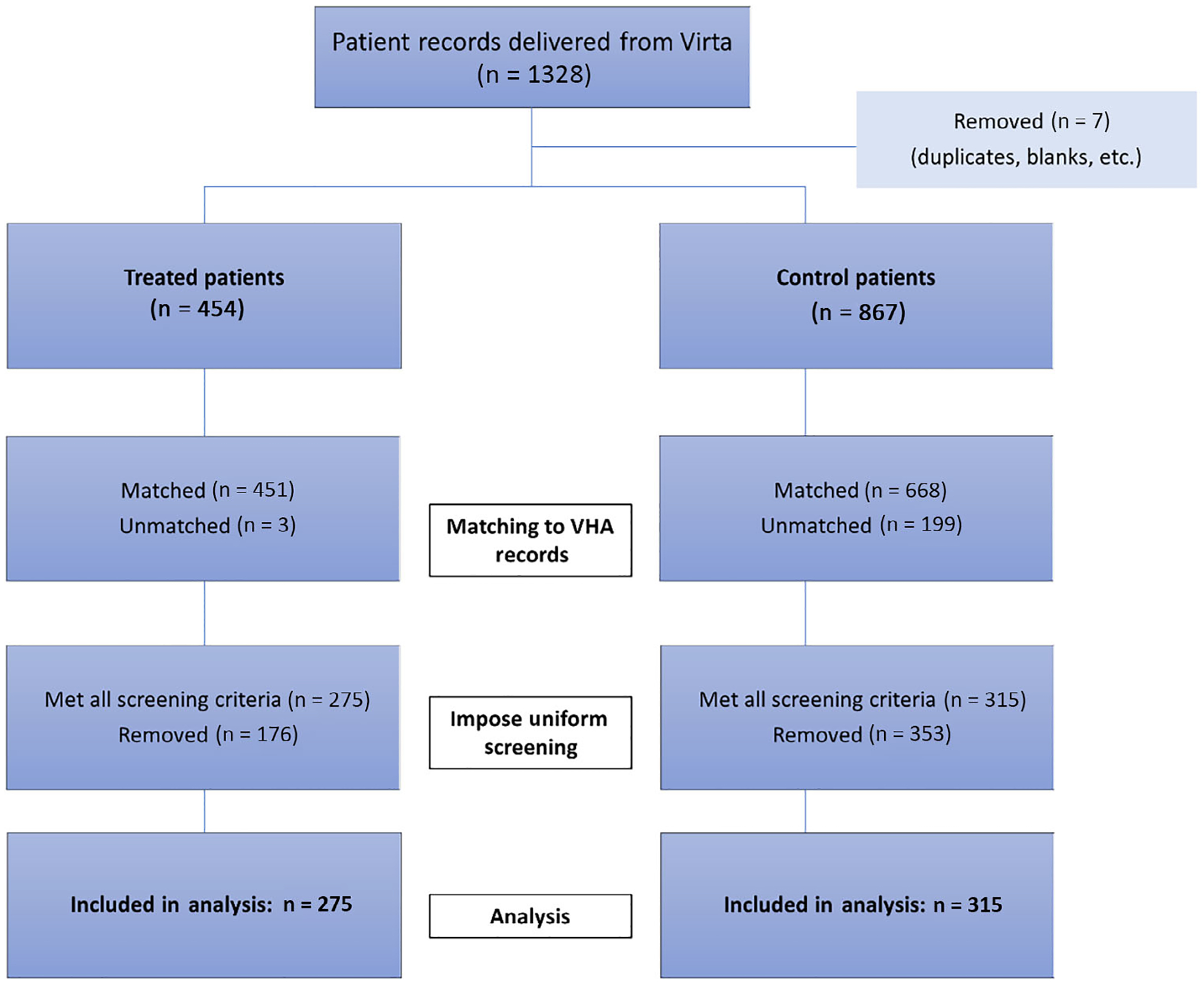

Virta Health provided 1328 patient records to the VA research team. Seven of these records were removed because of duplicate entries or blank records. Of the viable records, 454 were marked as treatment patients and 867 were marked as control patients. Figure 1 shows how the analytical sample was derived. Using a combination of patient identifiers, 84.7% of Virta Health records were successfully matched to VA records. The match rate was higher in the treatment group (99.3%) than in the control group (77.0%). The somewhat higher match rate in the treatment group is probably because these participants were actively screened for eligibility by Virta Health staff whereas control group participants were not. After matching patient records, we imposed uniform inclusion criteria using VA data on HbA1c, diabetes diagnosis and prescription medications. Of the matched sample, 52.7% met all three inclusion criteria: 61.0% in the treatment group and 47.2% in the control group. The final analytical sample contained 590 patients: 275 in the treatment group and 315 in the control group.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of veterans in the analytical sample. VHA, Veterans Health Administration

3.2 |. Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the treatment and control groups are presented in Table 1. Treatment patients were more probable to be male and non-Hispanic White, and each of these variables are controlled for in the regression models. The treatment group had slightly lower baseline HbA1c and monthly insulin prescriptions, and slightly higher prior participation in VA weight-loss programmes. However, the trends in these variables between treatment and control groups were statistically indistinguishable during the preapplication period, supporting the assumption of parallel trends. All other measures of sociodemographic variables, healthcare utilization, health status and prescriptions were evenly distributed between treatment and control groups.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of veterans enrolled in the ketogenic diet and virtual coaching programme and in the waiting list control group, 2018–2020

| Baseline variables | Treatment (n = 275) | Control (n = 315) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||

| Males (%) | 85.8 | 92.7 | .007 |

| Age, y (average) | 58.1 | 57.7 | .577 |

| Urban resident (%) | 66.2 | 72.7 | .086 |

| Race/ethnicity (%) | |||

| Black, non-Hispanic | 13.8 | 19.4 | .02 |

| White, non-Hispanic | 68.4 | 56.2 | |

| Hispanic | 7.3 | 11.8 | |

| Other, non-Hispanic | 7.3 | 10.5 | |

| Missing | 3.3 | 2.2 | |

| Priority status (%) | |||

| 1–3 | 73.5 | 70.8 | .732 |

| 4–6 | 16.4 | 18.7 | |

| 7–8 | 10.2 | 10.5 | |

| VA utilization | |||

| Outpatient visits (monthly average) | 3.8 | 3.5 | .167 |

| Emergency department visits (monthly average) | 0.07 | 0.07 | .931 |

| Inpatient admissions (monthly average) | 0.02 | 0.02 | .977 |

| Health status | |||

| Co-morbidity index (average) | 1.0 | 1.2 | .204 |

| BMI (kg/m2, average)a | 35.2 (n = 260) | 35.0 (n = 298) | .842 |

| HbA1c (%, average) | 8.8 | 9.1 | .048 |

| Prescriptions (Rx) | |||

| Metformin (%) | 73.1 | 67.9 | .172 |

| Insulin (monthly average) | 0.5 | 0.6 | .042 |

| Diabetes medications (monthly average) | 1.1 | 1.1 | .607 |

| Total no. of non-metformin prescriptions | 6.2 | 6.5 | .371 |

| Average cost of diabetes prescriptions (monthly average) | 92.8 | 89.8 | .696 |

Note: P values were computed using two-sample t tests for differences in continuous variables, and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; Rx, number of fills; VA, Veterans Health Administration.

The number of observations for BMI are smaller because of missingness in the variable. Sample sizes for this metric are presented in parentheses next to group averages.

3.3 |. Impacts of the keto diet and virtual coaching programme

The difference-in-differences estimates comparing health outcomes before and after KD-VC programme application dates are reported in Table 2 and are shown graphically in Figure 2. The KD-VC programme was associated with a −0.69% (standard error [SE]: 0.168) decline in HbA1c and BMI was reduced by −1.07 (SE: 0.447) during the 5-month study period. Significant reductions were noted in the number of monthly insulin prescriptions and all monthly diabetes-related medications. The reduction in average monthly diabetes-related medication costs was −$34.54 (SE: 7.135) per patient. Treatment was associated with a small reduction in the number of monthly outpatient visits. No significant changes in inpatient admissions or ED visits were detected.

TABLE 2.

Five-month changes in diabetes outcomes for veterans in the ketogenic diet and virtual coaching programme and control groups, before and after Virta application dates

| Outcomes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HbA1c | Body mass index | Systolic blood pressure | Diastolic blood pressure | Outpatient visits (no.) | Inpatient admissions (no.) | ED visits (no.) | Insulin prescriptions (no.) | Any diabetes prescriptions (no.) | Prescription drug costs |

| Treatment*postperiod (DiD estimator)a | 0.69*** (0.168) |

−1.07* (0.447) |

−0.78 (1.245) |

−1.43* (0.658) |

−0.36* (0.175) |

−0.01 (0.008) |

−0.02 (0.015) |

−0.21*** (0.041) |

−0.38*** (0.059) |

−34.54** (7.135) |

| Treatment group indicator | −0.23 (0.148) |

0.52 (0.655) |

−0.63 (1.197) |

0.84 (0.647) |

0.28 (0.206) |

0.002 (0.0051) |

0.0033 (0.014) |

−0.030 (0.050) |

0.024 (0.060) |

8.897 (8.796) |

| Postperiod indicator | −0.24 (0.178) |

−0.15 (0.573) |

−0.37 (1.382) |

0.26 (0.701) |

0.57** (0.197) |

0.002 (0.008) |

−0.0079 (0.014) |

−0.0034 (0.045) |

0.054 (0.070) |

3.281 (8.568) |

| Observations | 1548 | 2459 | 2794 | 2794 | 7080 | 7080 | 7080 | 7080 | 7080 | 7080 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.104 | 0.046 | 0.019 | 0.107 | 0.086 | 0.010 | 0.009 | 0.028 | 0.022 | 0.011 |

The treatment*postperiod difference-in-difference (DiD) indicator estimates the impact of Virta treatment. Robust standard errors are displayed in parentheses. All regression models included variables for male, age, co-morbidity index, urban, race/ethnicity, priority status and calendar month fixed effects, not shown here. Full regression results are presented in Appendices SA and SB. The number of observations are reported at the patient-month level.

P < 0.01.

P < 0.05.

P < 0.001.

FIGURE 2.

Difference-in-differences graphs for 5-month changes in diabetes outcomes for veterans in the ketogenic diet and virtual coaching treatment and control groups, before and after Virta application dates. Shown are the average monthly trends in eight different outcome measures (HbA1c, body mass index [BMI], systolic blood pressure [SBP], diastolic blood pressure [DBP], number of diabetes medication fills [No. T2D Rx], number of insulin medication fills [No. insulin Rx], number of Veterans Health Administration [VA] outpatient visits and number of VA emergency department [ED] visits) for the Virta treatment group and the waiting list control group. Virta application month is indexed at month zero

For all outcomes, results did not vary significantly with the inclusion of baseline covariates and/or time fixed effects in the models. Unadjusted differences in outcomes are presented in Appendix SA and month-specific treatment effects are included in Appendix SB.

3.4 |. Tests for differential missingness in outcomes

We tested for differential missingness in outcomes between treatment and control groups for HbA1c, BMI, SBP/DBP (combined), ED visits and outpatient visits (Appendix SC). Only one outcome, BMI, showed evidence of differential attrition. Treatment group patients were 5% more probable to have a missing BMI value and 4% more probable to have a missing BP value in the postapplication period, relative to control group patients. We then weighted the observations in the primary difference-in-differences specification using the inverse of the probability of having a non-missing BMI value in the postapplication period. Results from this analysis were not meaningfully different from the results in the primary specifications (Appendix SD).

4 |. DISCUSSION

In this quasi-experimental study using a difference-in-differences analysis with a waiting list control group, we found that a KD-VC programme was associated with significant reductions in HbA1c, diabetes medication fills, prescription medication costs, BMI, DBP and outpatient visits over 5 months among overweight and obese veterans with diabetes. Results were also robust when assessed for differential missingness of data. These findings support a role for this programme as a lifestyle intervention for patients with diabetes.

The magnitude of the changes we observed are consistent with prior research investigating the efficacy of other virtual diet programmes for diabetes care, irrespective of dietary guidelines.22 With respect to HbA1c, we found that the KD-VC programme reduced HbA1c by 0.69%. Reductions of this magnitude are considered clinically meaningful by clinicians and regulatory agencies.23 Other named diet virtual programmes that advocate the restriction of certain foods or macronutrients report short-term HbA1c reductions in the range of 0.8%–1.1%, although there is substantial variation in the strengths of study designs.3–5,12 Named virtual diet programmes that promote healthy eating based on national dietary guidelines, national diabetes guidelines or caloric restriction either report no impact on HbA1c or reductions of up to 0.6%–0.9%.6–11 However, many of these reports did not include a control group for comparison.

We found that participation in the KD-VC programme led to an estimated 1.07 kg/m2 reduction in BMI, which is approximately 3% of the average preapplication BMI in the control group. This treatment effect is comparable with previously published studies of virtual diabetes programmes, which report BMI reductions associated with programme participation of 2.5%–8%.3,6–8,10,13–15,24–28 Although we observed differential missingness in the BMI outcome, with treatment group participants being 5% more probable to have a missing outcome in the postapplication period, the use of inverse probability weighting models did not change the magnitude or precision of the results.

A novel contribution of this study is its use of administrative data to examine the impact of a KD-VC programme on healthcare utilization and costs. We found that the intervention led to a 0.36 reduction in the average number of monthly outpatient visits per patient and a 0.38 reduction in the average number of monthly diabetes medication fills over the 5-month period. The 34.5% reduction in diabetes medication fills from the baseline (preapplication period) is similar to that reported by other virtual diabetes programmes, in which declines in medication usage are in the 5%–40% range.4–7,10 Savings attributable to the reduction in diabetes-related medications were approximately $35 per patient per month, which represents approximately 10% of the monthly programme cost. These cost reductions are probably conservative relative to other healthcare systems. Prescription drug prices within the VA are lower than private sector costs, as the VA negotiates medication purchase prices and uses a unified list of covered drugs, and discounts are defined by law.

This study has some limitations that may impact its generalizability. The study was conducted in a real-world environment and randomization was not performed. We worked to overcome this by simulating inclusion criteria with administrative data, and this produced study groups that approached being matched on observable characteristics. After imposing uniform screening criteria, we found no significant differences in pretreatment trends among study participants. We were unable to control for motivational differences between treatment and control groups, so it is possible that some veterans who initially expressed interest in the KD-VC programme would not have enrolled or completed the treatment if offered the chance. The study design also did not allow us to monitor KD-VC programme adherence in the treatment group or dietary changes in the control group.

It remains unclear whether the favourable effects observed operate through the personalized coaching component, the keto diet, patient motivation, or some combination of these. Given that adherence to the keto diet may be difficult and that the long-term effects of the diet are as of yet unknown, it is important to understand the differential impacts of various components of virtual diabetes programmes.12 Because we relied on administrative data for outcome measures, there was potential for differential missingness. Although we observed greater postapplication missingness for some data in the treatment group, models that used inverse probability of observation weighting produced similar findings to the main results. Finally, it is important to note that we cannot comment on the durability of these results. The postapplication study period was 5 months, and therefore we cannot infer that results with a KD-VC programme are sustainable over longer periods of time.

In this study we showed that a lifestyle intervention involving a KD-VC programme produced clinically meaningful effects over 5 months on biochemical markers and healthcare utilization in patients with diabetes. As patients’ personal and cultural preferences for diets are probable to vary, future research may seek to test the efficacy and appropriateness of a variety of diet options with or without coaching.22 This research could inform how virtual diet programmes could be used to meet the needs of patients with diabetes. Compiling a scientifically rigorous evidence base with long-term follow-up data, attention to possible untoward effects and appropriate control groups is critically important as we continue to seek innovative approaches to diabetes prevention and treatment.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was reviewed and exempted by the VA Boston Health System IRB, and subsequently approved by the R&D committee and assigned R&D #3317-X. This work is supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development (HSR&D SDR 20-386) and National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (R01 DK114098).

Funding information

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Grant/Award Number: R01 DK114098; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Grant/Award Number: HSR&D SDR 20-386

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of the article at the publisher’s website.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs, United States Government, Boston University, or Harvard University.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Authors elect not to share data and the reason is: VA data is restricted to authorized VA researchers.

REFERENCES

- 1.Liu Y, Sayam S, Shao X, et al. Prevalence of and trends in diabetes among veterans, United States, 2005–2014. Prev Chronic Dis 2017; 14:170230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maciejewski ML, Maynard C. Diabetes-related utilization and costs for inpatient and outpatient services in the Veterans Administration. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(suppl 2):b69–b73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kempf K, Altpeter B, Berger J, et al. Efficacy of the telemedical lifestyle intervention program TeLiPro in advanced stages of type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(7): 863–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saslow LR, Summers C, Aikens JE, Unwin DJ. Outcomes of a digitally delivered low-carbohydrate type 2 diabetes self-management program: 1-year results of a single-arm longitudinal study. JMIR Diabetes. 2018;3(3):e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berman MA, Guthrie NL, Edwards KL, et al. Change in glycemic control with use of a digital therapeutic in adults with type 2 diabetes: cohort study. JMIR Diabetes. 2018;3(1):e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim S, Kang SM, Kim KM, et al. Multifactorial intervention in diabetes care using real-time monitoring and tailored feedback in type 2 diabetes. Acta Diabetol. 2016;53(2):189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim KM, Park KS, Lee HJ, et al. Efficacy of a new medical information system, ubiquitous healthcare service with voice inception technique in elderly diabetic patients. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):18214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansel B, Giral P, Gambotti L, et al. A fully automated web-based program improves lifestyle habits and HbA1c in patients with type 2 diabetes and abdominal obesity: randomized trial of patient E-coaching nutritional support (the ANODE study). J Med Internet Res. 2017; 19(11):e360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koot D, Goh PSC, Lim RSM, et al. A mobile lifestyle management program (GlycoLeap) for people with type 2 diabetes: single-arm feasibility study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(5):e12965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ku EJ, Park J, Jeon HJ, Oh TK, Choi HJ. Clinical efficacy and plausibility of a smartphone-based integrated online real-time diabetes care system via glucose and diet data management: a pilot study. Intern Med J. 2020;50:1524–1532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schusterbauer V, Feitek D, Kastner P, Toplak H. Two-stage evaluation of a telehealth nutrition management service in support of diabesity therapy. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2018;248:314–321. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirkpatrick CF, Bolick JP, Kris-Etherton PM, et al. Review of current evidence and clinical recommendations on the effects of low-carbohydrate and very-low-carbohydrate (including ketogenic) diets for the management of body weight and other cardiometabolic risk factors: a scientific statement from the National Lipid Association Nutrition and Lifestyle Task Force. J Clin Lipidol. 2019;13(5):689–711.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Athinarayanan SJ, Adams RN, Hallberg SJ, et al. Long-term effects of a novel continuous remote care intervention including nutritional ketosis for the management of type 2 diabetes: a 2-year non-randomized clinical trial. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKenzie AL, Hallberg SJ, Creighton BC, et al. A novel intervention including individualized nutritional recommendations reduces hemoglobin A1c level, medication use, and weight in type 2 diabetes. JMIR Diabetes. 2017;2(1):e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hallberg SJ, McKenzie AL, Williams PT, et al. Effectiveness and safety of a novel care model for the Management of Type 2 diabetes at 1 year: an open-label, non-randomized, controlled study. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9(2):583–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leino AD, Dorsch MP, Lester CA. Changes in statin use among US adults with diabetes: a population-based analysis of NHANES 2011–2018. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(12):3110–3112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dimick JB, Ryan AM. Methods for evaluating changes in health care policy: the difference-in-differences approach. JAMA. 2014;312(22): 2401–2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee J, Callaghan T, Ory M, Zhao H, Bolin JN. The impact of Medicaid expansion on diabetes management. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(5):1094–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S. How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Q J Econ. 2004;119(1):249–275. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansournia MA, Altman DG. Statistics notes inverse probability weighting. Br Med J. 2016;352:i189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Veazie S, Vela K, Helfand M. Evidence brief: virtual diet programs for diabetes. Washington (DC), USA: Department of Veterans Affairs (US); 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenters-Westra E, Schindhelm RK, Bilo HJ, Groenier KH, Slingerland RJ. Differences in interpretation of haemoglobin A1c values among diabetes care professionals. Neth J Med. 2014;72(9):462–466. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haste A, Adamson AJ, McColl E, Araujo-Soares V, Bell R. Web-based weight loss intervention for men with type 2 diabetes: pilot randomized controlled trial. JMIR Diabetes. 2017;2(2):e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun C, Sun L, Xi S, et al. Mobile phone-based telemedicine practice in older Chinese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2019;7(1):e10664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Storch K, Graaf E, Wunderlich M, Rietz C, Polidori MC, Woopen C. Telemedicine-assisted self-management program for type 2 diabetes patients. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2019;21(9):514–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wayne N, Perez DF, Kaplan DM, Ritvo P. Health coaching reduces HbA1c in type 2 diabetic patients from a lower-socioeconomic status community: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2015; 17(10):e224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhanpuri NH, Hallberg SJ, Williams PT, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factor responses to a type 2 diabetes care model including nutritional ketosis induced by sustained carbohydrate restriction at 1 year: an open label, non-randomized, controlled study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Authors elect not to share data and the reason is: VA data is restricted to authorized VA researchers.