Abstract

Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), an oxidoreductase, possesses two vicinal cysteines in the -Cys-Gly-His-Cys-motif that either form a disulfide bridge (S–S) or exist in a sulfhydryl form (-SH), forming oxidized or reduced PDI, respectively. PDI has been proven to be critical for platelet aggregation, thrombosis, and hemostasis, and PDI inhibition is being evaluated as a novel antithrombotic strategy. The redox states of functional PDI during the regulation of platelet aggregation, however, remain to be elucidated. Endoplasmic reticulum (ER) oxidoreductin-1α (Ero1α) and PDI constitute the pivotal oxidative folding pathway in the ER and play an important role in ER redox homeostasis. Whether Ero1α and PDI constitute an extracellular electron transport pathway to mediate platelet aggregation is an open question. Here, we found that oxidized but not reduced PDI promotes platelet aggregation. On the platelet surface, Ero1α constitutively oxidizes PDI and further regulates platelet aggregation in a glutathione-dependent manner. The Ero1α/PDI system oxidizes reduced glutathione (GSH) and establishes a reduction potential optimal for platelet aggregation. Therefore, platelet aggregation is mediated by the Ero1α-PDI-GSH electron transport system on the platelet surface. We further showed that targeting the functional interplay between PDI and Ero1α by small molecule inhibitors may be a novel strategy for antithrombotic therapy.

Keywords: PDI, Ero1α, Platelet, Glutathione, Redox

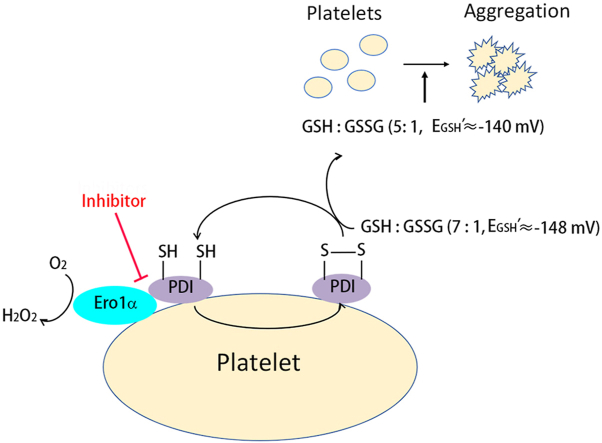

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Oxidized but not reduced PDI promotes platelet aggregation.

-

•

Ero1α and PDI constitute an electron transport pathway on platelet surface.

-

•

Ero1α and PDI provide a redox environment optimal for platelet aggregation.

-

•

The functional interplay between Ero1α and PDI can be a new target for antiplatelet therapy.

1. Introduction

Protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) is an endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-resident oxidoreductase that catalyzes the formation of correct disulfide bonds during protein folding. Approximately three decades ago, PDI was shown to be critical for platelet aggregation [1,2] and subsequently to have a major role in thrombosis and hemostasis [[3], [4], [5], [6]]. To date, several kinds of selective PDI inhibitors have been developed [7,8], and inhibition of PDI is being evaluated clinically as a novel antithrombotic strategy [9,10]. Nevertheless, the molecular and biochemical mechanisms of PDI in the regulation of platelet aggregation are far from clear.

PDI is composed of four thioredoxin domains arranged as a, b, b’ and a’. In addition, there is a linker “x” between the b′ and a′ domains and an acidic C-terminal tail. The b’ domain cooperates with the a and a’ domains to functionally interact with platelets [11], while the a’ domain is important for both platelet function and coagulation [6]. The two vicinal cysteines in the -Cys-Gly-His-Cys-motif in the a and a’ domains can exist in either a disulfide bridge (S–S) or a sulfhydryl form (-SH), forming oxidized or reduced PDI, respectively. The redox state of PDI determines either the oxidation, reduction, or isomerization reactions it catalyzes under different physiological and pathological processes [[12], [13], [14]]. However, the redox state of PDI in the regulation of platelet aggregation has never been reported. In addition, the mechanism by which only the a’ domain of PDI is required for thrombosis [6] is not clear.

PDI and ER oxidoreductin-1α (Ero1α) constitute the pivotal oxidative folding pathway in the ER. Ero1α binds to the b'xa’ fragment and preferentially oxidizes the a’ domain of PDI by utilizing oxygen [[15], [16], [17]]. The oxidase activity of Ero1α is feedback regulated via the formation or reduction of two regulatory disulfides [18,19] by PDI. The regulatory disulfides of inactive Ero1α can be reduced by reduced PDI to achieve the active form, and vice versa [20,21]. Ero1α was also found on the platelet surface and shown to contribute to redox-controlled remodeling of αIIbβ3 [22]. Therefore, it would be very interesting to study whether Ero1α and PDI constitute an extracellular electron transport pathway, similar to that in the ER, and mediate platelet aggregation.

In this study, for the first time to our knowledge, we found that oxidized PDI potentiates platelet aggregation, but reduced PDI has a limited effect. Ero1α oxidizes PDI on the platelet surface, which regulates platelet aggregation in a reduced glutathione (GSH)-dependent manner. The Ero1α/PDI system establishes an optimal GSH/GSSG reduction potential for platelet aggregation. Finally, PDI inhibitors targeting the b’ domain can efficiently disrupt the Ero1α/PDI electron transport system, revealing a novel mechanism by which these inhibitors prevent platelet aggregation. Thus, we proposed that targeting the functional interplay between PDI and Ero1α may be a new strategy for antithrombotic therapy.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

N-ethylmaleimide (NEM), methoxy polyethylene glycol 5000 maleimide (mPEG-5K), biotin-maleimide, 5,5′-dithiol-bis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), glutathione reductase (GR), rutin, bepristat 2a, streptavidin agarose and thrombin were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Collagen was from Chrono-log (Havertown, PA, USA). The LSARLAF peptide was synthesized by GenScript (Piscataway NJ, USA). Fibrinogen-FITC was prepared by a FluoReporter FITC protein labeling kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) was purchased from Roche. A HiTrap desalting column and Superdex 75 100/300 GL column were obtained from GE Healthcare. Mouse monoclonal anti-Ero1α (2G4) was purchased from Millipore. The Ero1α inhibitor was obtained from Calbiochem. Mouse monoclonal anti-PDI (RL90) and rabbit monoclonal anti-Ero1α were obtained from Abcam.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Protein expression, purification, and redox state determination

The expression and purification of PDI, PDI C1, PDI C1/2 and Ero1α were performed as described previously [15]. Reduced or oxidized PDI was prepared by dithiothreitol (DTT) reduction or K3[Fe(CN)6] oxidation as described [21]. To confirm the redox state of the proteins, 20 μM reduced or oxidized PDI was mixed with an equal volume of 2 × nonreducing loading buffer containing 5 mM mPEG-5K and incubated at 25 °C for 30 min [21]. The samples were then subjected to SDS-9% PAGE and Coomassie staining after quenching excess mPEG-5K with 25 mM DTT.

2.2.2. Insulin reduction assay

Insulin (130 μM) was mixed with 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer containing 2.5 mM EDTA and 0.5 mM DTT, pH 7.5, in a total volume of 200 μl. Insulin reduction was initiated by adding 0.5 μM PDI into the reaction mixture, and the absorption at 650 nm was monitored. To measure the IC50 of PDI inhibitors, different concentrations of inhibitors were preincubated with PDI for 15 min at 37 °C, and the values were calculated using nonlinear regression analysis.

2.2.3. Platelet preparation and aggregation

Human platelet preparation and aggregation were performed as described elsewhere [23]. Briefly, human venous blood was drawn into a one-seventh acid citrate dextrose (ACD, 85 mM sodium citrate, 65 mM citric acid, 2% dextrose) solution and centrifuged at 230×g for 20 min to obtain platelet-rich plasma (PRP). The PRP was then centrifuged at 600×g for 20 min to obtain platelet pellet. The pellet was resuspended in Tyrode's buffer (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.36 mM NaH2PO4, 12 mM NaHCO3, 5.5 mM glucose, 0.35% albumin, pH 7.35), and the platelet concentration was adjusted to 2 × 108/ml. Platelet aggregation was performed with a Chrono-log lumi-aggregometer (Havertown, PA, USA), and 1 mM CaCl2 was added to the platelet suspension prior to agonist administration. All studies on human platelets were performed after approval by the Institutional Review Board of the Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Science, with informed consent, in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2.4. Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed as described elsewhere [11]. Briefly, 100 μl of platelets in Tyrode's buffer (1 × 106/ml) was incubated with EN460 for 15 min and then stimulated with thrombin for 5 min at room temperature. The platelets were then incubated with anti-human/mouse P-selectin-PE or fibrinogen-FITC for 10 min. Next, the platelets were fixed with paraformaldehyde and analyzed by a BD FACSCalibur flow cytometer. To detect P-selectin expression, EDTA (1 mM), indomethacin (10 μM) and apyrase (1 U/ml) were added to the platelets to prevent aggregation.

2.2.5. Platelet adhesion assay

Platelet adhesion was performed as previously described [24]. Microtiter plates were coated with 20 μg/ml type I collagen or 1 mg/ml fibrinogen at 4 °C overnight. Platelets preincubated with 0.5 μM untreated, oxidized or reduced PDI for 15 min were then allowed to adhere to the microtiter plates for 1 h at 37 °C. After two washes with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), adherent platelets were quantified by the measurement of platelet acid phosphatase activity using p-NPP substrate.

2.2.6. Mouse tail bleeding time

EN460 or vehicle control was infused into C57 BL6/J mice to a final concentration of 50 μM (estimate the blood volume of a mouse is approximately 1.5 ml) through tail vein injection. The mouse tail was transected 3 mm from the tip, and the tail was immersed in a 15 ml test tube containing saline. Bleeding time was determined when the bleeding stopped for more than 10 s as previously described [25].

2.2.7. Measurement of total glutathione and glutathione disulfide (GSSG) in plasma

All mouse experiments were approved by the institutional Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Biophysics, Chinese Academy of Science. Mouse plasma was prepared as described [26]. Then, the levels of total glutathione and GSSG in the samples were measured by DTNB using an enzymatic recycling assay [26]. Briefly, the plasma was incubated with or without 2-vinylpyridine for 60 min at 25 °C to block GSH, and 2-vinylpyridine was then quenched by triethanolamine for 10 min at 25 °C. Then, 210 μM NADPH, 200 μM DTNB, and 0.5 U/ml GR were added to the mixture, and the absorbance at 412 nm was monitored. The slope of the absorbance over time was used to calculate the concentration of total glutathione or GSSG according to the GSH or GSSG standard curve, respectively.

2.2.8. GST-pulldown assay

PDI (10 μM) was incubated with 10 μM GST-Ero1α fusion protein in PBS for 2 h at 4 °C, and then the GST-Ero1α protein was pulldown by glutathione-Sepharose resin at 4 °C for another 1 h. After centrifugation, the beads were washed three times with PBS, and the bound proteins were detected by Coomassie staining.

To pulldown platelet PDI, 0.5 μM GST-Ero1α protein was incubated with 100 μg of platelet lysates, and the experiment was performed as described above.

2.2.9. Oxygen consumption assay

An oxygen consumption assay was performed as previously described [21]. Briefly, a final concentration of 20 μM PDI and 10 mM GSH were mixed in a total volume of 0.5 ml of buffer A (100 mM Tris-HAc, 50 mM NaCl, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.0), and the reaction was initiated by the addition of 2 μM Ero1α into the reaction vessel.

To measure oxygen consumption with platelets, 2 × 109/ml platelets instead of PDI was added to buffer A, and the reaction was initiated by the addition of 0.5 μM Ero1α, or by the activation of platelets with 0.5 U/ml thrombin after preincubating the PDI inhibitor with platelets for 15 min at 37 °C.

2.2.10. Redox state determination of platelet surface PDI

Platelets were incubated with 100 μM EN460 for 30 min at 37 °C and then centrifuged at 400×g for 10 min to remove EN460. The platelets were resuspended in Tyrode's buffer and labeled with 200 μM maleimide-biotin for 30 min at room temperature. After quenching excess maleimide-biotin with 2 mM DTT, the platelets were washed five times with Tris-buffered saline (TBS) containing 2 mM EDTA. The platelets were lysed with RIPA buffer, and labeled proteins were pulldown with streptavidin agarose at 4 °C overnight. The labeled PDI was detected by Western blot with anti-PDI serum.

2.2.11. Redox state determination of Ero1α

Ero1α (0.1 μM) was incubated with 2 × 109/ml platelets for 15 min at 37 °C, and then 10 mM NEM was added to block the free thiols in Ero1α. The redox state of Ero1α was detected by Western blot under nonreducing conditions. In some cases, platelets were activated with collagen before the addition of 10 mM NEM.

2.2.12. Statistics

Data were expressed as the mean ± SEM. Two-tailed Student's t-test for 2 groups and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test for multiple groups were used. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

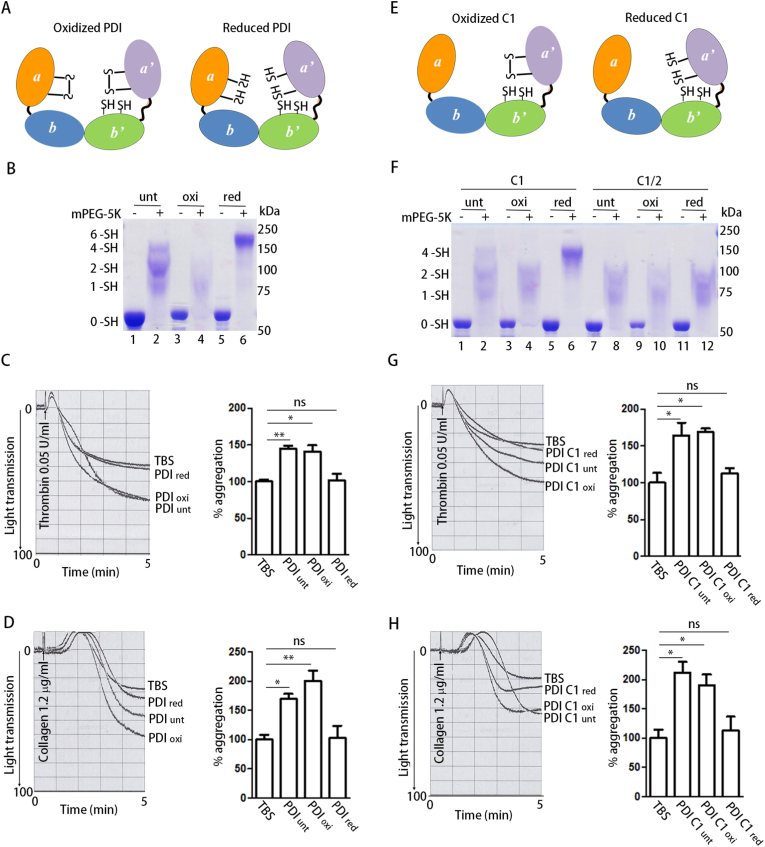

3.1. Oxidized but not reduced PDI potentiates platelet aggregation

We first compared the roles of PDI preparations under different redox states in platelet aggregation. The gel-based mPEG-5K modification assay [21] was used to monitor the redox state of PDI (Fig. 1A). The emergence of a large amount of 6 –SH species implied the predominant reduction of the two active sites in reduced PDI (PDIred) (Fig. 1B, Lane 6); in contrast, most of the oxidized PDI (PDIoxi) was modified by one or two mPEG-5K molecules in the b’ domain (Fig. 1B, Lane 4), indicating that both active sites were in oxidized form. In addition, few untreated PDI (PDIunt) molecules were modified by six mPEG-5K molecules (Fig. 1B, Lane 2), indicating that untreated PDI is more likely in the partially oxidized form.

Fig. 1.

Oxidized but not reduced PDI potentiates platelet aggregation.

(A) Scheme of oxidized (PDIoxi) and reduced (PDIred) PDI.

(B) PDI was oxidized by K3[Fe(CN)6] or reduced by DTT, and the free thiols in untreated PDI (PDIunt), PDIoxi and PDIred were quantitated by mPEG-5K labeling.

(C, D) Human platelets were incubated with PDIunt, PDIoxi, PDIred (0.5 μM) or Tris-buffered saline (TBS) alone for 15 min and then platelet aggregation was induced by thrombin (C) or collagen (D), respectively.

(E) Scheme of oxidized (PDI C1oxi) and reduced (PDI C1red) PDI C1.

(F) The free thiols in PDI C1 were quantitated by mPEG-5K as in (B). The double active site mutant PDI C1/2 was used to calibrate the number of free thiols in PDI C1.

(G, H) Human platelets were incubated with PDI C1oxi or PDI C1red (0.5 μM) for 15 min and then platelet aggregation was induced by thrombin (G) or collagen (H), respectively.

Data were shown as mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; n.s., not significant (one-way ANOVA). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Untreated PDI significantly potentiated platelet aggregation induced by thrombin (Fig. 1C) and collagen (Fig. 1D), as previously reported [6]. However, only oxidized PDI enhanced platelet aggregation compared to TBS (Fig. 1C and D), similar to untreated PDI, regardless of whether thrombin or collagen was used as an agonist. In contrast, reduced PDI had minimal effect on platelet aggregation than did TBS (Fig. 1C and D). Oxidized PDI also enhanced platelet aggregation induced by the LSARLAF peptide, which is a direct integrin αIIbβ3 agonist [27], while reduced PDI did not (Supplementary Fig. 1A). In addition, oxidized PDI significantly enhanced platelet adhesion to fibrinogen but had no effect on platelet adhesion to collagen (Supplementary Figs. 1B and C). These results suggest that oxidized PDI directly regulates αIIbβ3-mediated platelet function.

Since the a’ domain of PDI has been reported to be responsible for platelet aggregation and thrombosis [6], we tested the effects of the PDI C1 mutant (the active site in the a domain to -Ser-Gly-His-Ser-). The redox states of different PDI C1 preparations were also tested by mPEG-5K modification. Reduced PDI C1 (PDI C1red) existed exclusively in 4 –SH species, and oxidized PDI C1 (PDI C1oxi) was similar to the double active site mutant PDI C1/2 (Fig. 1F), which was modified by one or two mPEG-5K molecules in the b’ domain. Oxidized PDI C1 substantially enhanced thrombin- and collagen-induced aggregation, whereas reduced PDI C1 did not (Fig. 1G and H), implying that the oxidized a’ domain is critical for platelet aggregation. Taken together, these results demonstrate that oxidized but not reduced PDI regulates platelet aggregation.

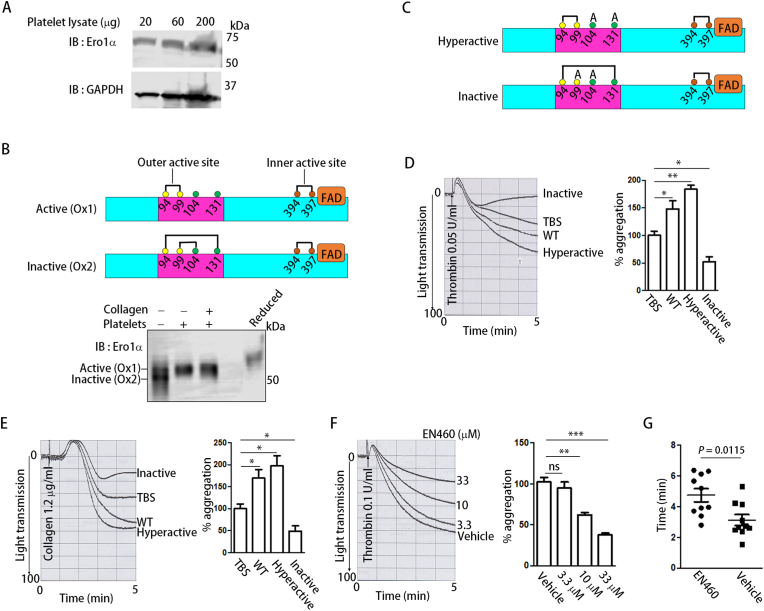

3.2. Ero1α regulates platelet aggregation via its oxidase activity

Ero1α is responsible for the reoxidation of PDI in the mammalian ER. As the Ero1α protein was detected in platelets by immunoblotting (Fig. 2A), we elucidated whether Ero1α is also responsible for the oxidation of PDI in platelets. Depending on the disruption or formation of two regulatory disulfide bonds, Cys94-Cys131 and Cys99-Cys104, purified Ero1α was present in the active (Ox1) or inactive forms (Ox2) (Fig. 2B) on a nonreducing gel (Fig. 2B, Lane 1). When incubated with platelets, the inactive form of Ero1α shifted to the active form (Fig. 2B, Lane 2). Platelet activation had no further effect on the activation of Ero1α since the addition of collagen to platelets did not further alter the redox states of Ero1α (Fig. 2B, Lane 3). To further reveal the role of the oxidase activity of Ero1α in platelet aggregation, we prepared hyperactive (C104A/C131A) and inactive (C99A/C104A) Ero1α [21] (Fig. 2C). After incubation with platelets, WT Ero1α and hyperactive Ero1α efficiently increased platelet aggregation, while inactive Ero1α significantly inhibited aggregation (Fig. 2D and E). EN460, a well-characterized Ero1α inhibitor [28], inhibited platelet aggregation in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2F). EN460 did not inhibit the surface expression of P-selectin (Supplementary Fig. 2A) but significantly decreased fibrinogen binding (Supplementary Fig. 2B), indicating that Ero1α regulates integrin αIIbβ3 activation without affecting α-granule secretion. Furthermore, when infused into mice, EN460 significantly prolonged mouse tail bleeding time (Fig. 2G), emphasizing the physiological significance of the inhibition of platelet Ero1α. Altogether, endogenous platelet Ero1α plays a key role in aggregation via its oxidase activity.

Fig. 2.

Ero1α regulates platelet aggregation via its oxidase activity.

(A) The expression of Ero1α in human platelets was detected by Western blot.

(B) Upper panel: scheme of active (Ox1) and inactive (Ox2) Ero1α. Only the inner active site (brown), outer active site (yellow) and regulatory cysteines (green) of Ero1α were shown for simplicity; Lower panel: Purified Ero1α was incubated with platelets in the presence or absence of collagen followed by NEM alkylation. The redox states of Ero1α were determined by nonreducing SDS-(9%) PAGE.

(C) Scheme of hyperactive (C104A

/C131A) and inactive (C99A

/C104A) Ero1α.

(D, E) Human platelets were incubated with WT, hyperactive or inactive Ero1α (0.5 μM) for 15 min and then platelet aggregation was induced by thrombin (D) or collagen (E), respectively.

(F) EN460 was incubated with platelets at indicated concentrations for 5

min and the effect of the inhibitor on aggregation was tested.

(G) EN460 or vehicle control was infused into C57 BL6/J mice and then mouse tail bleeding time was determined as described in the method.

Data were shown as mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s., not significant (one-way ANOVA). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

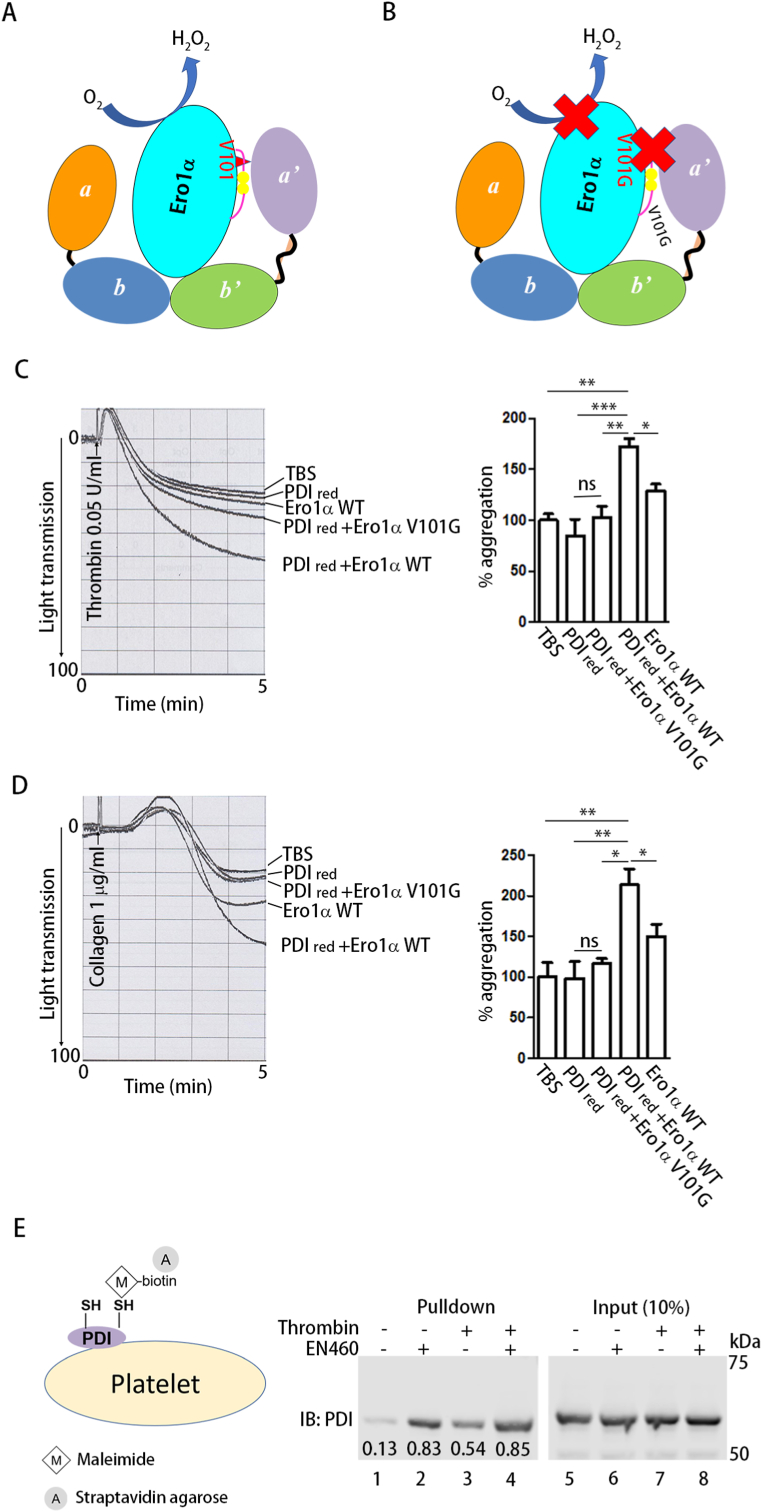

3.3. Ero1α regulates platelet aggregation through the oxidation of PDI

Ero1α oxidizes PDI by utilizing oxygen (Fig. 3A), and the conserved Val101 in Ero1α plays a critical role in the recognition and oxidation of the PDI a’ domain [17] (Fig. 3B). We incubated both WT Ero1α and reduced PDI with platelets and tested the effect of their functional interplay on platelet aggregation. Reduced PDI alone did not increase aggregation; however, platelet aggregation induced by thrombin (Fig. 3C) or collagen (Fig. 3D) was significantly enhanced upon further addition of WT Ero1α but not the V101G mutant, which disrupted the interaction between Ero1α and PDI. These results suggest that the efficient oxidation of PDI by Ero1α plays an important role in the regulation of platelet aggregation. Next, we incubated EN460 with platelets and tested whether endogenous platelet Ero1α also oxidizes PDI on platelets. The redox state of platelet surface PDI was detected by labeling the free thiols in PDI with biotin-maleimide and streptavidin agarose pulldown (Fig. 3E). Only a few PDI molecules were labeled (Fig. 3E, Lane 1); however, inhibition of Ero1α by EN460 substantially increased the biotin-maleimide modification of PDI (Fig. 3E, Lane 2). PDI was reduced during platelet activation (Fig. 3E, Lane 3); however, platelet activation did not result in a further reduction in PDI in the presence of EN460 (Fig. 3E, Lanes 2 and 4). As a control, incubation of EN460 with platelets did not result in a global change in platelet surface thiols (Supplementary Fig. 3), further validating the specificity of EN460 as an inhibitor of the Ero1α-PDI axis. Thus, Ero1α regulates platelet aggregation through the oxidation of PDI.

Fig. 3.

Ero1α regulates platelet aggregation through the reoxidation of PDI.

(A, B) Scheme illustrating that WT Ero1α oxidized PDI (A) but the V101G mutant didn't (B).

(C, D) Human platelets were incubated with reduced PDI (0.25 μM) alone or in combination with Ero1α WT (0.25 μM) or V101G mutant (0.25 μM), and then platelet aggregation was induced by thrombin (C) or collagen (D), respectively.

(E) human platelets were incubated with or without EN460 (100 μM) for 30 min and then the redox state of platelet surface PDI was detected by thiol labeling with maleimide-biotin followed by streptavidin agarose pulldown and Western blot. The numbers below the bands indicated the density of each band normalized to the corresponding input.

Data were shown as mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s., not significant (one-way ANOVA).

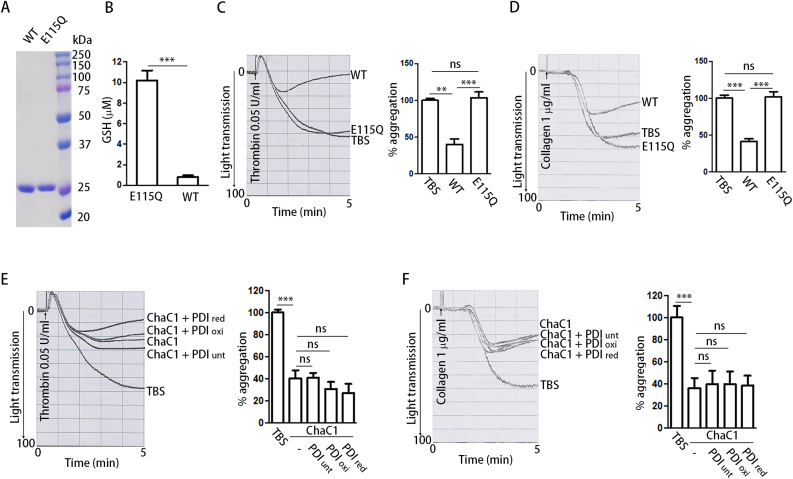

3.4. PDI regulates platelet aggregation in a GSH-dependent manner

GSH is the most abundant redox modulator of the cellular environment, and has also been found to be important for regulating the redox environment of platelets in blood [23]. To explore whether GSH could be a target of PDI in the regulation of platelet aggregation, we prepared the recombinant protein ChaC1, a γ-glutamyl cyclotransferase that specifically degrades GSH [29], as well as its inactive form E115Q (Fig. 4A). Active ChaC1 degraded more than 90% of GSH after incubation with plasma (Fig. 4B). Inactive ChaC1 did not affect platelet aggregation, whereas active ChaC1 markedly impaired platelet aggregation (Fig. 4C and D), suggesting that GSH plays an important role in platelet aggregation. Importantly, with GSH depletion, neither oxidized nor reduced PDI had an effect on platelet aggregation (Fig. 4E and F). These results indicate that the regulation of platelet aggregation by PDI strictly depends on the presence of GSH.

Fig. 4.

PDI regulates platelet aggregation in a GSH-dependent manner.

(A) The purity of recombinant ChaC1 and its inactive mutant (E115Q) was detected by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie staining.

(B) The active or inactive ChaC1 (3 μM) was incubated with whole blood for 1 h at room temperature, and then the total glutathione concentration was measured with DTNB method using an enzymatic GSH recycling assay.

(C, D) To evaluate the effect of GSH on platelet aggregation, whole blood was treated with active or inactive ChaC1 (3 μM) and then the platelets were isolated and stimulated with thrombin (C) or collagen (D), respectively.

(E, F) ChaC1-treated platelets were incubated with untreated, oxidized or reduced PDI (0.5 μM) for 15 min, and then platelet aggregation was induced by thrombin (E) or collagen (F), respectively.

Data were shown as mean ± SEM, **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s., not significant (one-way ANOVA).

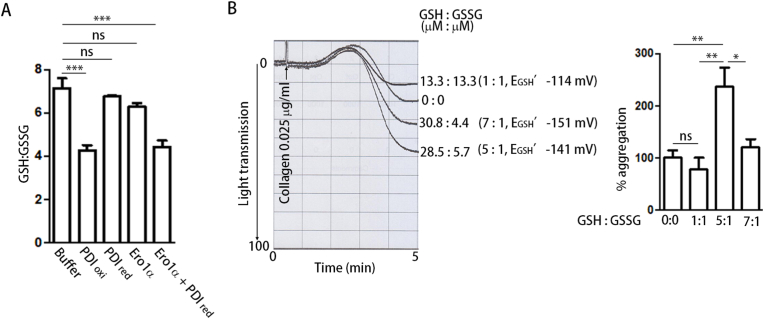

3.5. The Ero1α/PDI system increases the reduction potential of plasma glutathione to promote platelet aggregation

We further investigated the relationship between the Ero1α/PDI system and the GSH/GSSG level in plasma. Plasma glutathione was reported to be present predominantly in the reduced form, with the ratio of GSH/GSSG being in the range of 13:1 to 3.5:1 [[30], [31], [32]]. By using the enzymatic GSH recycling assay, we found that the ratio of GSH/GSSG in plasma was ∼7:1 to 8:1 (Fig. 5A, Table 1). Interestingly, oxidized PDI can oxidize GSH to GSSG, altering the ratio of GSH/GSSG from ∼7:1 to ∼4:1 and increasing the reduction potential of plasma glutathione from −148 mV to −139 mV (Fig. 5A, Table 1). Reduced PDI or Ero1α alone had little effect on the oxidation of GSH (Fig. 5A, Table 1). When reduced PDI and Ero1α were combined, GSH was oxidized, and the ratio of GSH/GSSG was altered to a similar extent as with oxidized PDI alone (Fig. 5A, Table 1). This reminded us of a previous finding that a GSH/GSSG ratio of 5:1 is the optimal redox environment for platelet aggregation [23]. We then tested the effect of different GSH/GSSG ratios on platelet aggregation without adding the Ero1α/PDI system. Among different combinations of GSH/GSSG with total glutathione at 40 μM, the ratio of 5:1 (equal to −141 mV) always resulted in the best potentiation on platelet aggregation (Fig. 5B). This reduction potential is very similar to the reduction potential provided by the Ero1α/PDI system. Taken together, these results indicate that the Ero1α/PDI system is able to establish an optimal reduction potential for platelet aggregation.

Fig. 5.

The Ero1α/PDI system establishes an optimal reduction environment for platelet aggregation.

(A) The plasma was incubated with the indicated protein or protein combination for 15

min, and then the total glutathione (GStotal) and GSSG concentration of the plasma was measured by DTNB using an enzymatic GSH recycling assay. GSH/GSSG was calculated as (GStotal - 2 × GSSG)/GSSG.

(B) Platelet aggregation was induced by collagen in the presence of different GSH/GSSG redox buffer.

Data were shown as mean ± SEM, *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; n.s., not significant (one-way ANOVA).

Table 1.

The Ero1α/PDI system oxidized GSH and increased the reduction potential of plasma glutathione.

| GStotal (μM) | GSH (μM) | GSSG (μM) | GSH/GSSG | E’ (mV) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buffer | 23.2 ± 1.8 | 18.1 ± 1.7 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 7.1 ± 0.5 | −148 ± 2 |

| PDIoxi | 22.6 ± 1.6 | 15.4 ± 0.8 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | −138 ± 1** |

| PDIred | 23.2 ± 1.4 | 17.8 ± 1.1 | 2.7 ± 0.1 | 6.7 ± 0.1 | −146 ± 1 |

| PDIred + Ero1α | 22.8 ± 1.6 | 15.7 ± 0.9 | 3.6 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | −136 ± 1** |

| Ero1α | 23.0 ± 1.6 | 17.5 ± 1.3 | 2.8 ± 0.1 | 6.3 ± 0.2 | −145 ± 1 |

The reduction potential was calculated according to the Nernst equation (E′ = E0′ - RT/nF * ln([GSH]2/[GSSG]), where E0′ = −258 mV, pH 7.3 [52] (n = 3). **P < 0.01, compared to buffer. Unpaired Student's t-test.

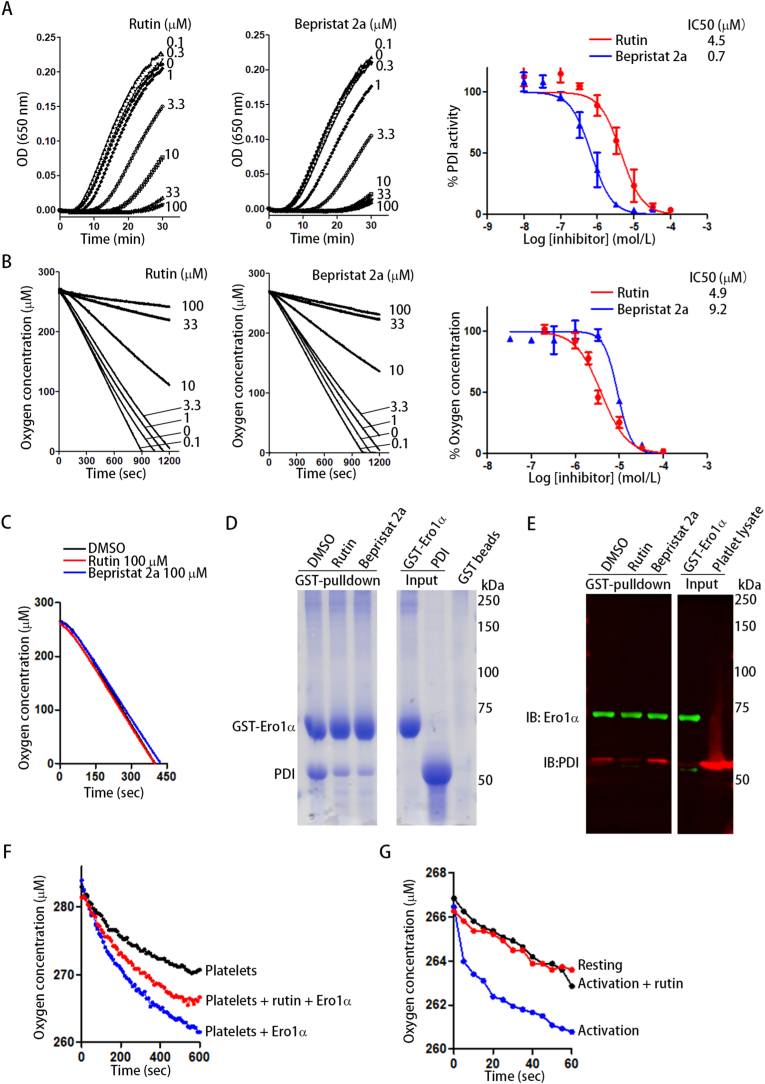

3.6. Disruption of the Ero1α/PDI oxidative pathway prevents platelet aggregation

Next, we tested whether disruption of the Ero1α/PDI oxidative pathway could be a novel strategy to prevent platelet aggregation. Rutin and bepristat 2a have been recently reported as novel PDI inhibitors that inhibit both PDI oxidoreductase activity and platelet aggregation, possibly by binding to the b’ domain of PDI and blocking αIIbβ3 binding [7,8]. Because the binding of PDI to Ero1α relies on the b’ domain of PDI [15,16], we reasoned that rutin and bepristat 2a could be potent Ero1α/PDI inhibitors. Both rutin and bepristat 2a inhibited the reductase activity of PDI using insulin as a model substrate, with IC50 values of 4.5 μM and 0.7 μM, respectively (Fig. 6A), similar to the effect previously reported [7,8]. More intriguingly, both rutin and bepristat 2a decreased Ero1α-catalyzed oxygen consumption, with IC50 values of 4.9 μM and 9.2 μM, respectively (Fig. 6B). The inhibition of oxygen consumption by rutin and bepristat 2a was specifically mediated by targeting PDI because neither inhibited the Ero1α-catalyzed oxidation of DTT in the absence of PDI (Fig. 6C). Both rutin and bepristat 2a markedly decreased the amount of PDI that bound to GST-Ero1α (Fig. 6D, Lanes 2 and 3). More importantly, rutin also prevented platelet PDI from interacting with Ero1α (Fig. 6E, Lane 2), but bepristat 2a did not (Fig. 6E, Lane 3). We speculated that rutin and bepristat 2a may bind to different sites on PDI and that these sites may have different effects on the binding of PDI with Ero1α, especially in platelets.

Fig. 6.

Rutin disrupts PDI and Ero1α interaction and inhibits the Ero1α/PDI oxidative pathway.

(A, B) Dose response and IC50 of rutin and bepristat 2a in insulin reduction assay (A) and in Ero1α-catalyzed oxygen consumption using PDI/GSH as substrates (B).

(C) Rutin or bepristat 2a was incubated with Ero1α and the oxygen consumption was monitored by using DTT as a substrate.

(D) Rutin or bepristat 2a was preincubated with PDI for 15

min followed the addition of GST-Ero1α and a further incubation of 30 min. The interaction of PDI and Ero1α was analyzed by GST-pulldown and Coomassie staining.

(E) Rutin or bepristat 2a was incubated with platelets followed by the addition of GST-Ero1α and a further incubation of 30 min. The platelets were lysed and the interaction of Ero1α with platelet PDI was tested by GST-pulldown and Western blot.

(F, G) Rutin or DMSO was incubated with platelets (2 × 109/ml) and then Ero1α was added to platelets (F); or 0.5 U/ml of thrombin was added to activate the platelets (G). The change of oxygen concentration in the platelet suspension was monitored.

The Ero1α/PDI system oxidized GSH and altered the GSH/GSSG ratio, but rutin inhibited this alteration when incubated with PDI (Table 2). While Ero1α induced oxygen consumption by platelets, rutin decreased the oxygen consumption induced by Ero1α (Fig. 6F). Platelet activation increased oxygen consumption (Fig. 6G); when rutin was added to the activated platelets, oxygen consumption was decreased to the level of resting platelets (Fig. 6G). Taken together, these results suggest that in addition to inhibiting the binding of PDI to its substrate, such as integrin αIIbβ3 on platelets, disruption of the interaction between PDI and its upstream oxidase Ero1α could be a novel mechanism by which rutin inhibits platelet aggregation.

Table 2.

Rutin prevented the Ero1α/PDI-catalyzed increase of reduction potential of plasma glutathione.

| GStotal (μM) | GSH (μM) | GSSG (μM) | GSH/GSSG | E’ (mV) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buffer | 26.8 ± 2.2 | 23.8 ± 2.1 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 8.2 ± 1.1 | −148 ± 3 |

| DMSO + PDI + Ero1α | 26.8 ± 2.6 | 23.1 ± 2.3 | 3.7 ± 0.3 | 5.2 ± 0.3 | −140 ± 1* |

| Rutin + PDI + Ero1α | 27.0 ± 3.0 | 24.0 ± 1.8 | 3.0 ± 0.4 | 7.8 ± 0.8 | −149 ± 2 |

The reduction potential was calculated as described in Table 1. *P < 0.05, compared to buffer. Unpaired Student's t-test.

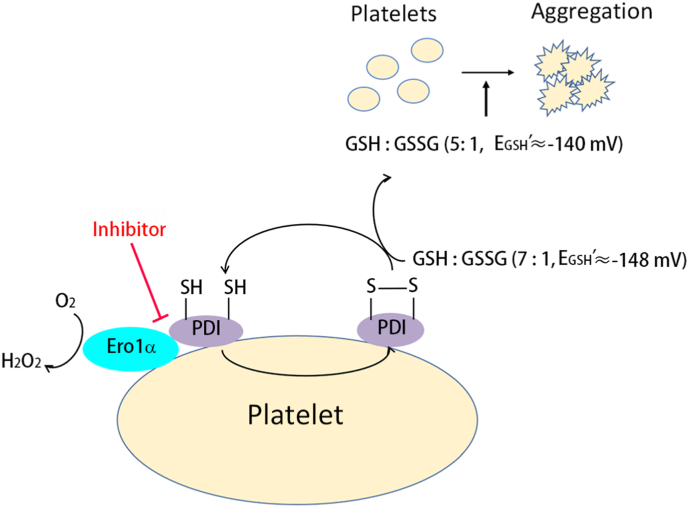

4. Discussion

The critical role of PDI in regulating platelet aggregation and thrombus formation is supported by a growing body of evidence; however, the redox state of PDI that regulates platelet aggregation remains a major question. In this study, for the first time to our knowledge, we unravel that oxidized but not reduced PDI promotes platelet function mediated by the integrin αIIbβ3. Ero1α forms an electron transport system with PDI and constitutively oxidizes PDI on the platelet surface. The Ero1α/PDI system oxidizes GSH and provides a reduction potential (approx. −140 mV in our system) optimal for platelet aggregation. We further show that targeting the functional interplay between PDI and Ero1α could be a novel strategy for antiplatelet therapy (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Working model of the Ero1α/PDI electron transport system on platelet aggregation.

Platelet Ero1α oxidizes PDI on platelet surface, maintaining most PDI to be in its oxidized state and the reduction potential of plasma glutathione to be approx. −148 mV. Additional Ero1α and PDI released from platelet or from other sources further oxidizes GSH to form GSSG, thereby altering the GSH/GSSG ratio and increases the reduction potential to approx. −140 mV. The increase of glutathione reduction potential provides an optimal redox environment for platelet aggregation. Disruption of the interaction between Ero1α and PDI can block the disulfides transfer from oxygen to the downstream molecules, and finally inhibits platelet aggregation.

Recombinant PDI purified from E. coli was used to potentiate platelet aggregation and to rescue the impaired aggregation of PDI-knockout platelets [5,6]. The redox state of the protein, however, was not checked. PDI purified from bovine liver was found to contain 1.1–1.3 mol of free thiols and 2.2–2.3 mol of GSH-reducible disulfides per mol of PDI [32], indicating that purified PDI is predominantly in the oxidized form. The mPEG-5K modification results also suggest that untreated PDI is mostly in the oxidized state. Thus, this could be why both untreated and oxidized PDI potentiate platelet aggregation to a similar extent. Nevertheless, oxidized PDI could be reduced by a plasma membrane reductive system [33] after being added to platelets. Thus, a side-by-side comparison of oxidized and reduced PDI is necessary to determine which redox form of PDI plays a role in platelet aggregation. The findings that oxidized PDI enhances aggregation but reduced PDI has little effect clearly demonstrate the requirement of oxidized PDI for platelet aggregation.

The Ero1α/PDI oxidative folding system plays an important role in ER redox homeostasis [34]. Ero1α was shown to be expressed on the platelet surface and was associated with PDI and αIIbβ3 in activated platelets [22]. Here, we provide the following experimental evidence that Ero1α-PDI-GSH constitutes an electron transport pathway on platelet that functions in platelet aggregation: 1) reduced PDI alone had minimal effect on platelet aggregation but enhanced aggregation in the presence of Ero1α; 2) reduced PDI was not able to increase platelet aggregation together with Ero1α V101G, which cannot oxidize PDI; 3) Ero1α along with reduced PDI oxidized GSH to GSSG, but Ero1α or PDI alone had limited effects; 4) Ero1α increased oxygen consumption when incubated with platelets; and 5) inhibition of endogenous platelet Ero1α resulted in decreased platelet aggregation and prolonged mouse tail bleeding time. The redox state of PDI secreted from platelets or bound to the platelet surface is a fundamental question that must be answered. Our study provides direct evidence that PDI is oxidized by Ero1α on the platelet surface. The inhibition of endogenous platelet Ero1α substantially elevated the amount of reduced PDI on the platelet surface, indicating that platelet surface PDI was oxidized by endogenous platelet Ero1α. PDI was not further reduced by platelet activation in the presence of EN460, indicating that most PDI was reduced when Ero1α was inhibited. These results clearly demonstrate that platelet surface PDI is constitutively oxidized by Ero1α, independent of platelet activation.

The finding that Ero1α and PDI constitute an electron transport pathway on the platelet surface also explains why only the a’ domain of PDI is responsible for platelet aggregation and thrombosis [6], because Ero1α prefers to oxidize the a’ domain rather than the a domain of PDI [15]. Several PDI family members, including ERp5, ERp57, ERp72 and ERp46, exist on the platelet surface and regulate platelet activation [25,[35], [36], [37], [38]]. Although they are not efficiently oxidized by Ero1α in the ER because they lack the unique b’ domain of PDI, they are potent regulators of Ero1α activation for possessing the -Cys-Gly-His-Cys-active sites [21]. However, whether they can activate Ero1α on the platelet surface or cooperate with Ero1α for functional electron transfer is yet unknown. It will be interesting to elucidate the distinct roles of different PDI family members in platelet activation in the future.

An optimal redox environment constituted by a GSH/GSSG ratio of 5:1 is important for platelet aggregation [23]. However, the glutathione in plasma is basically present in the reduced form (GSH) [24]. How this optimal GSH/GSSG ratio is regulated is not clear. Moreover, the reduction potential of glutathione is determined by [GSH]2/[GSSG] [39], so it is critical to know the absolute concentrations of the two species but not just their ratios. We first showed that plasma GSH was required for PDI-regulated platelet aggregation. More importantly, the Ero1α/PDI electron transport system oxidized plasma GSH and increased the reduction potential of glutathione from −148 mV (GSH/GSSG ≈ 7:1) to −140 mV (GSH/GSSG ≈ 5:1). A reconstituted glutathione buffer with the ratio of GSH/GSSG ≈5:1 (28 μM/6 μM, −141 mV) gave the best potentiation on platelet aggregation among the conditions we tested, representing an optimal reduction potential for platelet aggregation. This result is in line with a previous study that showed that adding a 10 μM/2 μM (−131 mV) or 20 μM/4 μM (−140 mV) GSH/GSSG mixture gave better potentiation than the use of the same ratio but with higher concentrations (lower reduction potential) [23]. Taken together, our results suggest that the Ero1α/PDI electron transport pathway oxidizes GSH and modulates an optimal reduction potential for platelet aggregation. In this process, electrons are sequentially transferred from GSSG to PDI, Ero1α and finally to oxygen. Notably, the relatively narrow change in the reduction potential (approx. 10 mV) that regulates platelet aggregation is particularly significant because the regulation of platelet aggregation must be very sensitive to vascular injury but also tightly regulated to prevent unwanted platelet activation and adverse thrombotic events.

The mechanism by which this optimal reduction potential regulates platelet aggregation is not clear. It has been demonstrated that an appropriate GSH/GSSG redox buffer (5:1) significantly promoted PDI-catalyzed reactivation of reduced RNase [32], a process that requires both oxidation and isomerization of disulfide bonds. The main target of PDI in platelet aggregation is the integrin αIIbβ3 [6,40], and thiol-disulfide exchange is required for αIIbβ3 activation [[41], [42], [43], [44]]. Thus, the optimal reduction potential of approximately −140 mV could also enhance both the oxidoreductase and isomerase activities of platelet PDI to catalyze disulfide rearrangement or disulfide formation in αIIbβ3 [45], allowing it to go from an inactive to a primed or activated state. On the other hand, it is possible that the specific reduction potential could alter the intermediates of αIIbβ3, which could make them better substrates for PDI. In addition, αIIbβ3 displays intrinsic thiol isomerase activity [46,47], so this optimal reduction potential could also be helpful for the thiol isomerase activity of αIIbβ3 and promote αIIbβ3-catalyzed reactions, such as autocatalyzed intramolecular thiol-disulfide exchange.

The critical role of the Ero1α/PDI electron transport system in platelet aggregation makes it a promising target for antithrombotic therapy. The unique b’ domain of PDI plays a critical role in the selective oxidation of PDI by Ero1α. Thus, the b’ domain could serve as a feasible target for specific inhibition of the Ero1α and PDI interaction. Rutin is an antithrombotic agent that targets the b’ domain of PDI [7,48]. Rutin, in addition to inhibiting the reductase activity of PDI, also disrupted the functional interplay between Ero1α and PDI. Bepristats are another set of PDI inhibitors that also target the b’ domain and inhibit platelet activation and thrombosis [8]. Unexpectedly, bepristat 2a did not disrupt the interaction between platelet PDI and Ero1α, although it inhibited the Ero1α and PDI interaction in the oxygen consumption assay. Rutin inhibited the reductase activity of PDI in both the insulin reduction and Di-E-GSSG assays, whereas bepristat 2a only inhibited the reductase activity of PDI in the insulin reduction assay but increased PDI's activity in the Di-E-GSSG assay [8,48], implying that these two inhibitors may have different binding sites on PDI. In our study, the IC50 of bepristat 2a in the insulin reduction assay was ten times lower than that in the oxygen consumption assay. Altogether, these results suggest that rutin more potently inhibits the interaction of PDI with both its substrate and its oxidase on platelets. Since the Ero1α/PDI oxidative folding pathway is also important in cancer progression [17,49], future drug development targeting the functional interplay between Ero1α and PDI could kill two birds with one stone for both anticancer and antithrombotic therapy, which is especially important for the clinical treatment of cancer patients with a high risk of thrombosis [50,51].

Author contributions

Lu W. performed experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; X.W. performed experiments and analyzed the data; X.L., Q.J., H.S. provided key instruments and helped platelet aggregation experiments; C.C.W. and Lei W. supervised the study, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate Dr. David W. Essex (Sol Sherry Thrombosis Research Center, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA, USA) for helpful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32022033, 31771261, 31870761); the National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFA0504000, 2021YFA1300800); the Strategic Priority Research Program of CAS (XDB37020303); the Youth Innovation Promotion Association, CAS, to Lei Wang, and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2018M641499) to Lu Wang.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2022.102244.

Contributor Information

Lu Wang, Email: lu.wang163@gmail.com.

Lei Wang, Email: wanglei@ibp.ac.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Essex D.W., Li M. Protein disulfide isomerase mediates platelet aggregation and secretion. Br. J. Haematol. 1999;104:448–454. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.1999.01197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Essex D.W., Li M., Miller A., Feinman R.D. Protein disulfide isomerase and sulfhydryl-dependent pathways in platelet activation. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6070–6075. doi: 10.1021/bi002454e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho J., Furie B.C., Coughlin S.R., Furie B. A critical role for extracellular protein disulfide isomerase during thrombus formation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:1123–1131. doi: 10.1172/JCI34134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reinhardt C., et al. Protein disulfide isomerase acts as an injury response signal than enhances fibrin generation via tissue factor activation. J. Clin. Invest. 2008;118:1110–1122. doi: 10.1172/JCI32376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim K., et al. Platelet protein disulfide isomerase is required for thrombus formation but not for hemostasis in mice. Blood. 2013;122:1052–1061. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-492504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou J., et al. The C-terminal CGHC motif of protein disulfide isomerase supports thrombosis. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:4391–4406. doi: 10.1172/JCI80319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jasuja R., et al. Protein disulfide isomerase inhibitors constitute a new class of antithrombotic agents. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:2104–2113. doi: 10.1172/JCI61228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bekendam R.H., et al. A substrate-driven allosteric switch that enhances PDI catalytic activity. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12579. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furie B., Flaumenhaft R. Thiol isomerases in thrombus formation. Circ. Res. 2014;114:1162–1173. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.301808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flaumenhaft R., Furie B., Zwicker J.I. Therapeutic implications of protein disulfide isomerase inhibition in thrombotic disease. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2015;35:16–23. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.303410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang L., et al. The b’ domain of protein disulfide isomerase cooperates with the a and a’ domain to functionally interact with platelets. J. Thromb. Haemostasis. 2019;17:371–382. doi: 10.1111/jth.14366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brophy T.M., Coller B.S., Ahamed J. Identification of the thiol isomerase-binding peptide, mastoparan, as a novel inhibitor of shear-induced transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1) activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:10628–10639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.439034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mineiro M.F., et al. Urate hydroperoxide oxidizes endothelial cell surface protein disulfide isomerase-A1 and impairs adherence. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj. 2020;1894:129481. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2019.129481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gimenez M., et al. Disulfide bond between protein disulfide isomerase and p47(phox) in vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019;39:224–236. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang L., et al. Reconstitution of human Ero1-alpha/protein disulfide isomerase oxidative folding pathway in vitro. Position-dependent differences in role between the a and a’ domains of protein disulfide isomerase. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:199–206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806645200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inaba K., et al. Crystal structures of human Ero1alpha reveal the mechanisms of regulated and targeted oxidation of PDI. EMBO J. 2010;29:3330–3343. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y., et al. Targeting the functional interplay between endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductin-1α and protein disulfide isomerase suppresses the progression of cervical cancer. EBioMedicine. 2019;41:408–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2019.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Appenzeller-Herzog C., et al. A novel disulphide switch mechanism in Ero1alpha balances ER oxidation in human cells. EMBO J. 2008;27:2977–2987. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baker K.M., et al. Low reduction potential of Ero1alpha regulatory disulphides ensures tight control of substrate oxidation. EMBO J. 2008;27:2988–2997. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Appenzeller-Herzog C., et al. Disulphide production by Ero1α-PDI relay is rapid and effectively regulated. EMBO J. 2010;29:3318–3329. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang L., et al. Different interaction modes for protein disulfide isomerase (PDI) as an efficient regulator and a specific substrate of endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductin-1alpha (Ero1alpha) J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:31188–31199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.602961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Swiatkowska M., et al. Ero1α is expressed on blood platelets in association with protein-disulfide isomerase and contributes to redox-controlled remodeling of αIIbβ3. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:29807–29883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.092486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Essex D.W., Li M. Redox control of platelet aggregation. Biochemistry. 2003;42:129–136. doi: 10.1021/bi0205045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellavite P., et al. A colorimetric method for the measurement of platelet adhesion in microtiter plates. Anal. Biochem. 1994;216:444–450. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang L., et al. Platelet-derived ERp57 mediates platelet incorporation into a growing thrombus by regulation of the αIIbβ3 integrin. Blood. 2013;122:3642–3650. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-06-506691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson M.E., Meister A. Dynamic state of glutathione in blood plasma. J. Biol. Chem. 1980;255:9530–9533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derrick J.M., et al. The peptide LSARLAF causes platelet secretion and aggregation by directly activating the integrin αIIbβ3. Biochem. J. 1997;325:309–313. doi: 10.1042/bj3250309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blais J.D., et al. A small molecule inhibitor of endoplasmic reticulum oxidation 1 (ERO1) with selectively reversible thiol reactivity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:20993–21003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.126599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kumar A., et al. Mammalian proapoptotic factor ChaC1 and its homologues function as γ-glutamyl cyclotransferases acting specifically on glutathione. EMBO Rep. 2012;13:1095–1101. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lash L.H., Jones D.P. Distribution of oxidized and reduced forms of glutathione and cysteine in rat plasma. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1985;240:583–592. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90065-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mansoor M.A., Svardal A.M., Ueland P.M. Determination of the in vivo redox status of cysteine, cysteinylglycine, homocysteine, and glutathione in human plasma. Anal. Biochem. 1992;200:218–229. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(92)90456-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lyles M.M., Gilbert H.F. Catalysis of the oxidative folding of ribonuclease A by protein disulfide isomerase: dependence of the rate on the composition of the redox buffer. Biochemistry. 1991;30:613–619. doi: 10.1021/bi00217a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolvetang E.J., et al. Apoptosis induced by inhibitors of the plasma membrane NADPH-oxidase involves Bcl-2 and calcineurin. Cell Growth Differ. 1996;7:1315–1325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang L., Wang X., Wang C.C. Protein disulfide-isomerase, a folding catalyst and a redox-regulated chaperone. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2015;83:305–313. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jordan P.A., et al. A role for the thiol isomerase protein ERP5 in platelet function. Blood. 2005;105:1500–1507. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-02-0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Holbrook L.M., et al. The platelet-surface thiol isomerase enzyme ERp57 modulates platelet function. J. Thromb. Haemostasis. 2012;10:278–288. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04593.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou J., et al. The disulfide isomerase ERp72 supports arterial thrombosis in mice. Blood. 2017;130:817–828. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-12-755587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou J., et al. A novel role for endoplasmic reticulum protein 46 (ERp46) in platelet function and arterial thrombosis in mice. Blood. 2021:2021012055. doi: 10.1182/blood.2021012055. blood. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hatahet F., Ruddock L.W. Protein disulfide isomerase: a critical evaluation of its function in disulfide bond formation. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2009;11:2807–2850. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cho J., et al. Protein disulfide isomerase capture during thrombus formation in vivo depends on the presence of β3 integrin. Blood. 2012;120:647–655. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-372532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yan B., Smith J.W. A redox site involved in integrin activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:39964–39972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiao T., et al. Structural basis for allostery in integrins and binding to fibrinogen-mimetic therapeutics. Nature. 2004;432:59–67. doi: 10.1038/nature02976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mor-Cohen R. Disulfide bonds as regulators of integrin function in thrombosis and hemostasis. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2016;24:16–31. doi: 10.1089/ars.2014.6149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Manickam N., Ahmad S.S., Essex D.W. Vicinal thiols are required for activation of the αIIbβ3 platelet integrin. J. Thromb. Haemostasis. 2011;9:1207–1215. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang M., Flaumenhaft R. Oxidative cysteine modification of thiol isomerases in thrombotic disease: a hypothesis. Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2021 doi: 10.1089/ars.2021.0108. 0108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O'Neill S., et al. The platelet integrin αIIbβ3 has an endogenous thiol isomerase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:36984–36990. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003279200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhu G., et al. The integrin PSI domain has an endogenous thiol isomerase function and is a novel target for antiplatelet therapy. Blood. 2017;129:1840–1854. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-07-729400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lin L., et al. Quercetin-3-rutinoside inhibits protein disulfide isomerase by binding to its b'x domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2015;290:23543–23552. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.666180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shergalis A.G., et al. Role of the ERO1-PDI interaction in oxidative protein folding and disease. Pharmacol. Ther. 2020;210:107525. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2020. 107525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stopa J.D., Zwicker J.I. The interaction of protein disulfide isomerase and cancer associated thrombosis. Thromb. Res. 2018;164:S130–S135. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zwicker J.I., et al. Targeting protein disulfide isomerase with the flavonoid isoquercetin to improve hypercoagulability in advanced cancer. JCI Insight. 2019;4 doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.125851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones D.P. Redox potential of GSH/GSSG couple: assay and biological significance. Methods Enzymol. 2002;348:93–112. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)48630-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.