Abstract

Background

Population-based state cancer registries are an authoritative source for cancer statistics in the United States. They routinely collect a variety of data, including patient demographics, primary tumor site, stage at diagnosis, first course of treatment, and survival, on every cancer case that is reported across all U.S. states and territories. The goal of our project is to enrich NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry data with high-quality population-based biospecimen data in the form of digital pathology, machine-learning-based classifications, and quantitative histopathology imaging feature sets (referred to here as Pathomics features).

Materials and methods

As part of the project, the underlying informatics infrastructure was designed, tested, and implemented through close collaboration with several participating SEER registries to ensure consistency with registry processes, computational scalability, and ability to support creation of population cohorts that span multiple sites. Utilizing computational imaging algorithms and methods to both generate indices and search for matches makes it possible to reduce inter- and intra-observer inconsistencies and to improve the objectivity with which large image repositories are interrogated.

Results

Our team has created and continues to expand a well-curated repository of high-quality digitized pathology images corresponding to subjects whose data are routinely collected by the collaborating registries. Our team has systematically deployed and tested key, visual analytic methods to facilitate automated creation of population cohorts for epidemiological studies and tools to support visualization of feature clusters and evaluation of whole-slide images. As part of these efforts, we are developing and optimizing advanced search and matching algorithms to facilitate automated, content-based retrieval of digitized specimens based on their underlying image features and staining characteristics.

Conclusion

To meet the challenges of this project, we established the analytic pipelines, methods, and workflows to support the expansion and management of a growing repository of high-quality digitized pathology and information-rich, population cohorts containing objective imaging and clinical attributes to facilitate studies that seek to discriminate among different subtypes of disease, stratify patient populations, and perform comparisons of tumor characteristics within and across patient cohorts. We have also successfully developed a suite of tools based on a deep-learning method to perform quantitative characterizations of tumor regions, assess infiltrating lymphocyte distributions, and generate objective nuclear feature measurements. As part of these efforts, our team has implemented reliable methods that enable investigators to systematically search through large repositories to automatically retrieve digitized pathology specimens and correlated clinical data based on their computational signatures.

Keywords: Cancer registries, Computational imaging, Deep-learning, Digital pathology

1. Introduction

The NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program is a coordinated system of 19 cancer registries that is charged with providing timely and accurate data regarding cancer incidence, mortality, treatment, and survival. Pathology datasets currently available in the SEER registries are qualitative in nature, consisting of scoring and staging data captured in normal registry abstracts and pathology reports. Such datasets are generally subject to inter-observer variability, which can result in biases in population-wide studies of cancer incidence, mortality, survival, and prevalence. The main goal of our project is to enrich SEER registry data with high-quality population-based digital biospecimen data in the form of pathology tissue images and detailed computational tissue characterizations and features (also referred to as Pathomics features) derived from the images. Examples of Pathomics data include detailed characterizations of cancer and stromal nuclei and quantification and mapping of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) along a supplementary histology classification generated through deep-learning algorithms. These data will augment existing registry data with quantitative features obtained directly from clinically acquired whole slide tissue images and provide detailed and nuanced information on tumor histology.

The scientific premise motivating this work is that the incorporation of quantitative digital pathology into the cancer registries will result in a valuable population-wide dataset that can provide additional insight into the underlying characteristics of cancer. Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies have captured much attention of the clinical community for their capacity to provide insight as to personalized choice in treatment and therapy. A major limitation of NGS technologies is that they obliterate the spatial information associated within and throughout the tumor environment. Histopathology and immunostaining localization techniques preserve this information which is invaluable in making accurate determinations. In fact, it is through the process of histopathology examination that tumor margins/volumes are determined by pathologists prior to the NGS analysis. These parameters are subsequently used to help guide decisions regarding appropriate cut-offs for allele frequencies and drive other components of the overall analysis. Pathomics features extracted from high-resolution pathology images are a quantitative surrogate of what is described in a pathology report. The important distinction is that these features are reproducible, unlike human observations, which are highly qualitative and subject to a high degree of inter- and intra-observer variability. The importance of increasing reproducibility and reducing inter-observer variability in pathology studies has been previously reported.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26 Moreover, many studies have demonstrated that quantitative image characterizations (e.g., nuclear features, patterns of TILs) are promising biomarkers which can be used to predict outcome and treatment response, if available in a large population.27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39 These biomarkers integrated with clinical and genomics data can provide new opportunities to enhance our understanding of cancer incidence, mortality, survival, along with statistical characterizations of lifetime risk, and to improve prediction and assessment of therapeutic effectiveness.

Our project began as collaboration among investigators within the state cancer registries of New Jersey, Georgia, and Kentucky. The consortium of partnering sites has recently expanded to include the newly established New York Cancer Registry. In this collaborative effort, we are implementing a framework of data curation and analysis workflows, computational imaging tools, and informatics infrastructure to support the creation and management of a well-curated, integrated repository of high-quality digitized pathology images and Pathomics features, for subjects whose data are being collected by the registries. The framework is being developed in close collaboration with SEER registries to ensure that it is scalable and in-line with existing registry processes and can support queries and the creation of population cohorts that span multiple registries.

In our framework, whole slide tissue images in the repository are systematically processed to compute Pathomics data and to establish linkages with registry data. The current set of Pathomics data includes (1) quantification of TILs, (2) segmentation and computational description of cancerous and stromal nuclei, (3) segmentation of tumor regions, (4) characterization of regional Gleason grade for prostate cancer, and (5) identification of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) adenocarcinoma subtypes. This initial set is primarily motivated by an increasing number of scientific studies that investigate TILs and the relationships among TILs, tumors, and nuclear structure of tissue.40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 Such investigations can provide important information to advance our understanding of immune response in many cancer types. In the future, additional Pathomics features, such as the spectral and spatial signatures of staining characteristics exhibited by the digitized specimens, will be incorporated into our framework.

The informatics infrastructure for this project is being built on open-source software and leverages modern software technologies, such as containerization and web-based applications, for a scalable, extensible implementation.46,47 The infrastructure facilitates visualization of high-resolution whole slide tissue images along with associated Pathomics datasets. User authentication and access controls are implemented to thwart unauthorized access to data. The informatics infrastructure is being expanded to include tools to support content-based image retrieval.

Presently, the repository manages diagnostic whole slide tissue images and analysis results obtained from 772 prostate cases, 1410 NSCLC cases, 70 breast cancer cases, and 48 lymphoma cases from the New Jersey State Cancer Registry and from 198 breast cancer cases from the Georgia State Cancer Registry. The scientific validation of the proposed environment will be undertaken through performance studies led by investigators throughout the four collaborating sites with an overarching focus on breast cancer, colorectal cancer, lymphoma, melanoma, NSCLC, and prostate cancer. We are confident that this repository will enable effective integration of pathology imaging and feature data as an invaluable resource in SEER registries.

In the rest of the paper, we describe the design and implementation of the key components of the framework: the data curation and analysis processes, the initial set of image analysis methods, and the underlying informatics infrastructure for data management and visualization.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Aggregation, quality control, and linkage of image data

The first component of our framework is the curation of pathology imaging data and linkage with other data from the cancer registries. Image quality control is an essential step, because specimen preparation protocols and tissue scanning procedures may result in imaging artifacts and variations in image quality. We devised and refined a workflow to facilitate the collection and quality control of digitized tissue specimens and linkage of images with correlated data extracted from the cancer registries. Here we describe the workflow deployed at Rutgers and the New Jersey SEER registry; the other sites—Georgia, Kentucky, and New York—are incrementally adopting analogous workflows as approved by their SEER registries and Institutional Review Boards (IRBs).

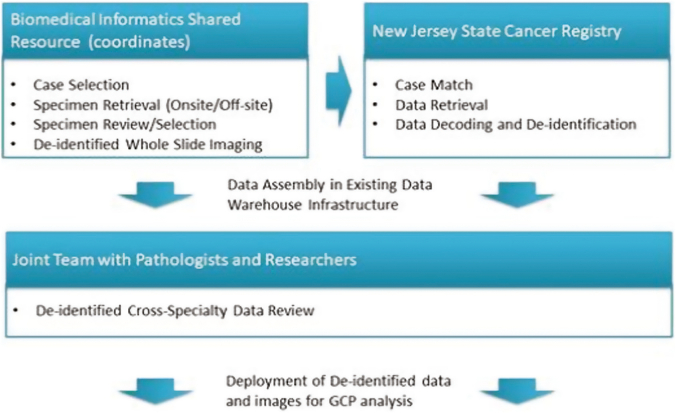

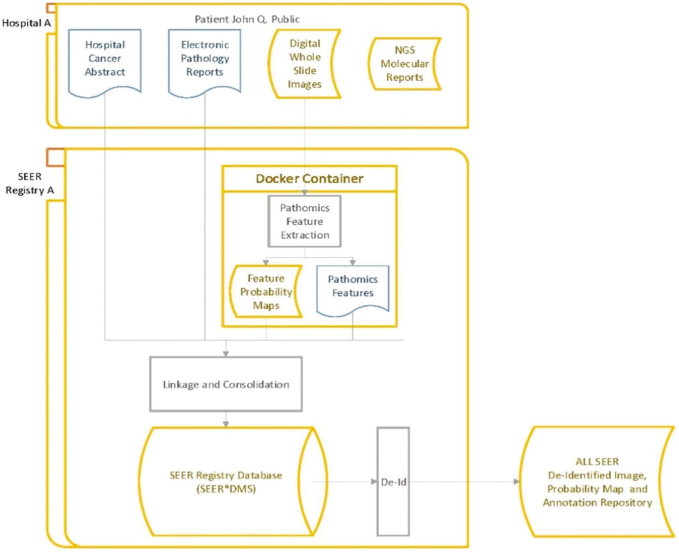

Fig. 1 depicts an instance of the workflow. Specimen retrieval and imaging are coordinated at the Biomedical Informatics Shared Resource (BISR) of Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey (RCINJ). Breast, colorectal, lung, melanoma, and prostate cancer cases suitable for the project exhibiting well-defined tumor type and diagnoses are selected by a pathologist at the RCINJ and Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School. Cases within approximately a 2-year window are retrieved from onsite storage, whereas others are requested from offsite storage with the help of BioSpecimens Repository Service of RCINJ. After a certified pathologist selects suitable slides according to requirement of each cancer type—e.g., prostate cancer specimens are selected according to the Gleason grade—the specimens are imaged with an Olympus VS120 whole slide scanner with no protected health information appearing in image filename, image metadata, or the images themselves.

Fig. 1.

Workflow for assembling linked image/data cohorts.

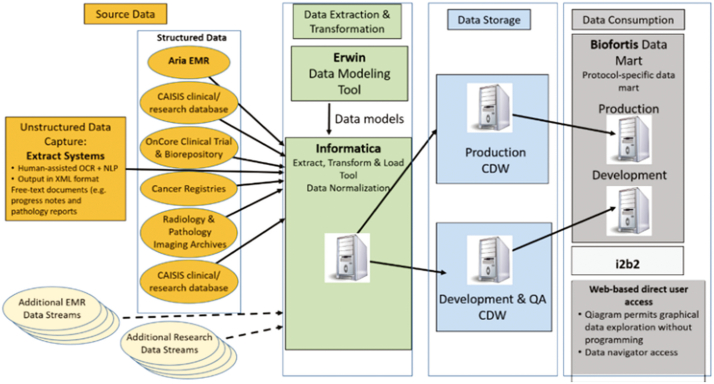

Team members from the BISR and NJCR perform cross-specialty review of the data for quality control. A secure, IRB-approved, Oracle-based (Redwood Shores, CA, USA) Clinical Research Data Warehouse is used at Rutgers to facilitate review of imaging and correlated clinical information on an individual patient basis or as part of large cohorts. The data warehouse has been commissioned to house multimodal data (genomics, digital pathology, radiology images). It orchestrates aggregation of information originating from multiple data sources including Electronic Medical Records, Clinical Trial Management Systems, Tumor Registries, Biospecimen Repositories, Radiology and Pathology archives, and Next Generation Sequencing services (Fig. 2). Innovative solutions were implemented in the warehouse to detect and extract unstructured clinical information that was embedded in paper/text documents, including synoptic pathology reports. The Warehouse receives objective oversight by a standing Data Governance Council.48 An Informatica-based (Redwood City, CA, USA) extraction transformation and load interface (ETL) has been developed to automatically populate the Data Warehouse with data elements originating from the multimodal data sources. This past year our team worked closely with the Google Healthcare team to successfully create and test an instance of the Data Warehouse on the Google Cloud Platform (GCP). In May 2020, we demonstrated the scalability of the cloud-based ETL, Warehouse, and Data Mart. As part of the project, our team will expand the use of the Warehouse by configuring it to integrate digitized pathology specimens with data originating from all of the collaborating cancer registries.

Fig. 2.

Clinical Research Data Warehouse workflow. The research data warehouse aggregates information from multiple data sources such as electronic health records, tumor registries, and radiology and pathology archives. It facilitates review of imaging data and linked clinical data on a single patient or cohort basis.

The images and cases are linked through deidentified ID sequences. The New Jersey State Cancer Registry receives the deidentified ID as well as case information including specific surgery number and date, so that after data retrieval and decoding encrypted fields, the deidentified ID is linked with clinical data associated with the case and, more specifically, with the diagnostic surgery. This ensures that the cancer specimen images are associated with the correct staging of the disease at the time of diagnosis so that it can be used in downstream research. The total corpus of data comprising the linked data sets encompasses more than 150 data elements, including the de-coded NAACCR data, as shown in Table 1. The de-identified images are analyzed through a set of deep-learning analysis pipelines as described in the subsequent sections.

Table 1.

Representative categories and linked data elements

| Source | Category | Representative elements |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer Registry | Demographics | age_at_dx, sex, marital_status_at_dx, race, nhia, napiia, county_at_dx, etc |

| Vital information | vital_status, date_of_death, primary_cause | |

| Tumor information | Primary_site, laterality, grade, diagnosis_confirmation | |

| Tumor extension and metastasis | cs_extension, cs_tumor_size, cs_lymph_nodes, cs_mets_at_dx | |

| Pathology info and tumor staging | histology_icdo3, behavior_icdo3, clinical and pathology staging in AJCC 6, 7, 8 and SEER staging | |

| Site-specific data | cs_site_specific factors | |

| Tumor treatments | Surgical, radiation, hormone, BRM, and other cancer treatment information | |

| Imaging | Pathology images | Digitized representative diagnostic slides in Olympus (.vsi) and Philips (.svs?) whole slide image formats, including image metadata such as imaging device, optical settings and configuration, specimen staining, etc. |

| Computational imaging signatures | Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes; tumor pattern segmentation; tumor and stromal nuclei segmentation; spatial and spectral signatures |

2.2. Extraction of pathomics features

Development of tissue image analysis methods is a highly active area of research and implementation. A variety of analysis methods for segmentation and classification of objects, regions, and structures (such as nuclei, tumors, glands) in tissue images have been developed. Excellent overviews of existing techniques can be found in several review papers.49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 Deep-learning-based analysis approaches have become popular, because deep-learning methods have been shown to outperform traditional image analysis methods in many application domains, including digital pathology. Our current tissue image analysis library consists of deep-learning methods developed by our group to classify patterns of TILs,56,57 segment tumor regions, classify tumor subtypes,58,59 and segment nuclei in whole slide images (WSIs) of hematoxylin and eosin-stained tissue samples.60,61

We should note that the analysis functionality is not limited to methods implemented by our group only. We have started with these methods because (1) they are based on state-of-the-art convolutional neural network architectures, suchasVGG16,62 Inception V4,63 ResNet,64 and U-Net,65 (2) they have achieved high accuracy scores, and (3) they have been previously used, refined, and validated in generating large, curated Pathomics datasets. For example, the TIL models were developed in close collaboration with pathologists, who generated a large set of training data, evaluated analysis results, and helped refine the models. The final models were employed to produce and publish a TIL dataset from 5202 WSIs from 13 cancer types.56,57 The nucleus segmentation model was developed in a similar approach with one difference. In addition to manually annotated segmentations, a synthetic data generation method, based on generative adversarial networks,66 was used to significantly increase the diversity and size of training data.60 The model trained with the combined manual and synthetic training data was used to generate a quality-controlled dataset of 5 billion segmented nuclei in 5060 WSIs from 10 cancer types61 in the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) repository. We plan to expand the suite of analysis methods and incorporate state-of-the-art methods developed by other groups over time. Indeed, at the time of writing this manuscript, we are in the process of integrating and validating Hover-Net67 in the framework for segmentation and classification of nuclei.

The current suite of TIL analysis models can resolve TIL distributions in a WSI at the level of 50 × 50 μm2 patches. The characteristics of tumor regions and the relationship between tumor regions and lymphocyte cells can be used to determine cancer stage and evaluate response to treatment. Our current models can segment tumor regions in lung, prostate, pancreatic, and breast cancer types and can classify tumor and non-tumor regions at the level of 88 × 88 μm2 patches. The model for prostate cancer can segment and label a tumor subregion with one of the three Gleason scores: Benign, Grade 3, and Grade 4+5. The lung tumor segmentation model is able to segment and label a tumor subregion with one of the six tumor subtypes: acinar, benign, lepidic, micropapillary, mucinous, and solid. Nucleus segmentation is one of the core digital pathology analysis steps. The shape and texture properties and spatial distributions of nuclei in tissue specimens are used in cancer diagnosis and staging. Our nucleus segmentation model can detect nuclei and delineate their boundaries in WSIs. After a WSI has been processed by the segmentation model, we compute a set of shape, intensity, and texture features. We use the PyRadiomics library68 to compute the patch-level features.

2.3. Management, visualization, and review of pathomics features

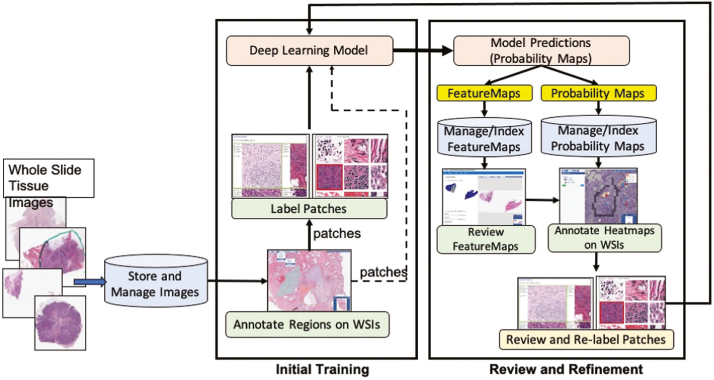

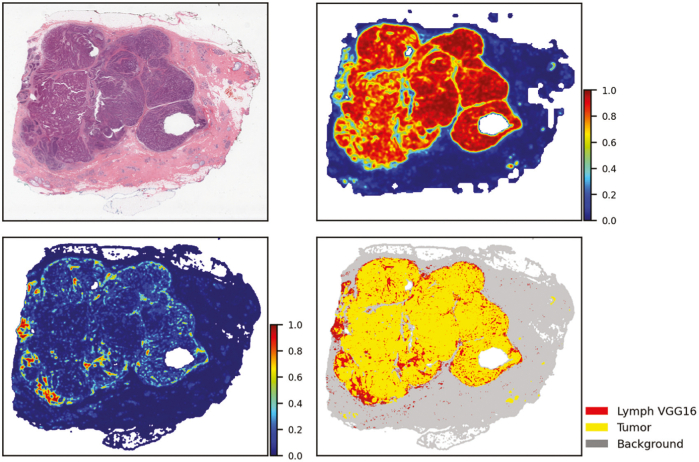

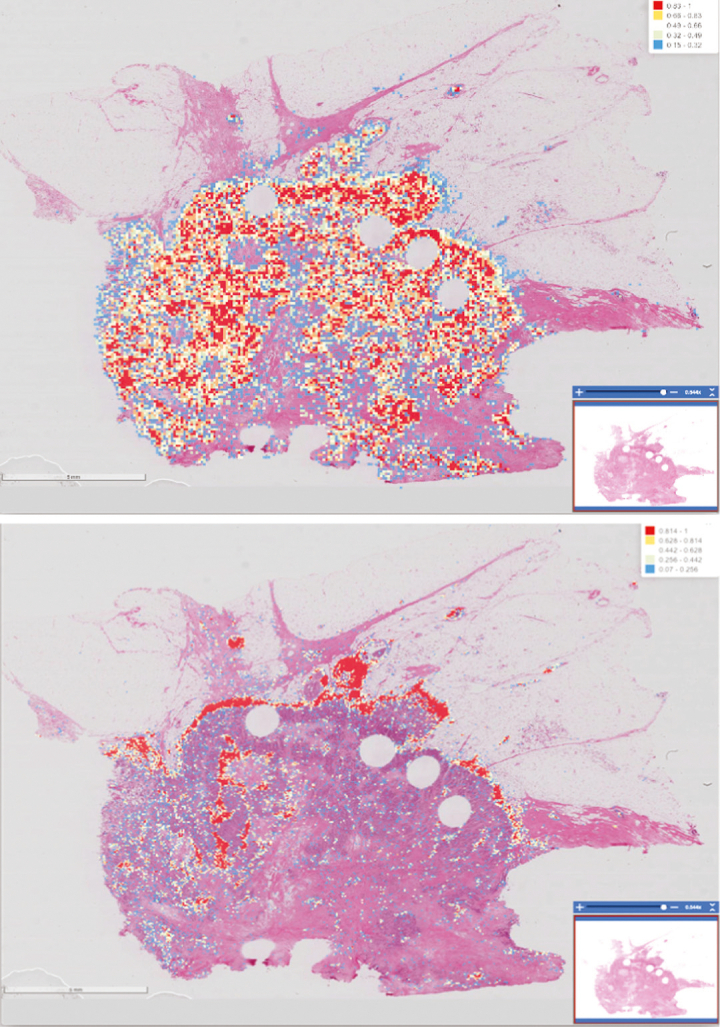

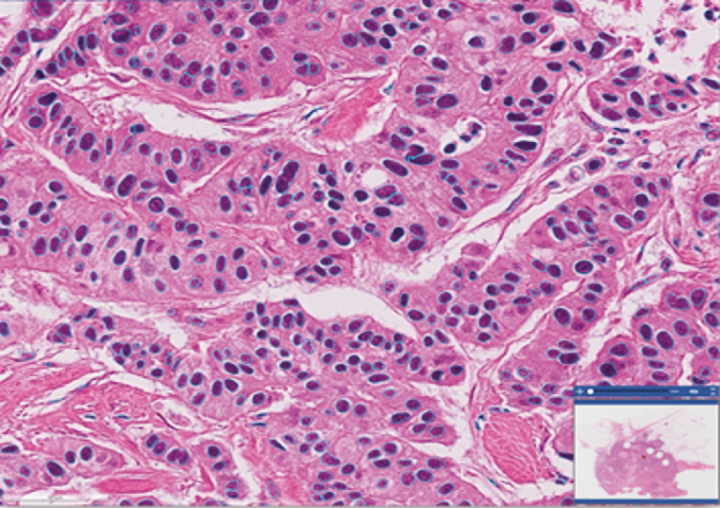

Our data analysis workflow implements an iterative train-predict-review-refine process to curate robust Pathomics features. This process is based on our earlier works in curating large Pathomics datasets57,59,61 and is carried out as part of the training and prediction phases of the deep-learning analysis pipelines. We developed a set of tools to enable the iterative process and to provide support for the management, indexing, and interactive viewing of WSIs and analysis results. The tools are implemented as a set of web-based applications and services in the PRISM and QuIP software platforms.46,47 Using these tools, pathologists can inspect the output of a tumor or TIL analysis pipeline as full-resolution heatmap overlays on WSIs. A heatmap is a spatial representation of prediction probabilities assigned to individual image patches by the deep-learning model; the probability value indicates if a patch is class-positive (e.g., TIL-positive, tumor-positive). Fig. 3 shows example heatmaps generated from the TIL (upper figure) and tumor (lower figure) analysis pipelines. Nuclear segmentation results can be viewed as polygons, which represent the boundaries of segmented nuclei as overlays on the images in QuIP (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

TIL and tumor analysis results displayed as a heatmap on the whole slide tissue image. TIL analysis results on the left and the tumor segmentation results on the right. The red color indicates a higher probability of a patch being TIL-positive (or tumor-positive) and the blue color indicates a lower probability

Fig. 4.

Segmented nuclei overlaid as polygons shown in blue on the WSI. Each polygon represents the boundary of a segmented nucleus

Fig. 5 shows how the iterative process is executed with QuIP. For example, after a set of WSIs are processed by the TIL and tumor segmentation models, the source WSIs and the heatmaps are loaded to QuIP for management and visualization. The heatmaps and WSIs are also transformed into feature maps. Feature maps are lower resolution representations of the heatmaps and WSIs in a four-panel image. Fig. 6 illustrates an example feature map which combines TIL results from a VGG16 model and tumor segmentation results from a ResNet model. The upper left corner of the image is the low-resolution tissue image, the upper right corner is the tumor segmentation map, the lower left corner represents the TIL map, and the lower right corner is the combined and thresholded TIL and tumor maps. Feature maps allow a pathologist to review results more efficiently than examining full-resolution images and maps. If the pathologist sees potential problems with the results during this review, they use the web applications in QuIP to visualize the WSIs and heatmaps at higher resolutions. If the review necessitates refinements to the model, additional training data are generated and added to the training dataset. They can annotate regions in an image using web-based visualization and annotation tools. Patches extracted from these annotations are reviewed and labeled to create additional training data. The model is refined by re-training the method with the updated training dataset.

Fig. 5.

The iterative workflow starts with a set of patches which are extracted from whole slide tissue images and labeled for initial model training. Predictions from the trained model are reviewed as feature maps and heatmaps. The heatmaps are annotated to generate additional labeled patches which are added to the training dataset. The deep learning network is retrained with the updated training dataset to refine the model

Fig. 6.

A feature map representation of TIL and tumor analysis results generated from a WSI in the Cancer Genome Atlas repository. The low-resolution version of the input WSI is displayed in the upper left corner. The upper right corner is the tumor segmentation map. The TIL map is displayed in the lower left corner. The lower right corner is the combined and thresholded TIL and tumor maps.

3. Results

The current implementation of the framework—the curation and analysis workflows, analysis methods, and informatics infrastructure—has been successfully deployed. The workflows and analytic methods have received IRB approval at all collaborating institutions. The framework has been employed to create a repository of diagnostic images from 772 prostate cases, 1410 NSCLC cases, 70 breast cancer cases, and 48 lymphoma cases from the New Jersey State Cancer Registry and from 198 breast cancer cases from the Georgia State Cancer Registry. The repository also contains results from TIL and tumor segmentation for each image and more than 2.5 billion segmented nuclei from all of the images. For each image, there are two TIL analysis results (one generated from the VGG16 network and the other from the Inception V4 network). The images and Pathomics data are managed by an instance of QuIP running at Stony Brook for interactive visualization of images and Pathomics features. All of the results and images are also stored in Box folders to facilitate bulk data downloads.

4. Discussion and conclusions

Evaluation of cancer control interventions in prevention, screening, and treatment and their effects on population trends in incidence and mortality hinge on accurate, reproducible, and nuanced pathology characterizations. Diagnostic and treatment guidelines also specify detailed measurements of TILs, nuclear grade; i.e., evaluation of the size and shape of the nucleus in the tumor cells, mitoses, and IHC staining, which are currently not included in cancer registry data abstraction. Presently, the SEER Pathology workflow, depicted in Fig. 7, begins with normal registry abstracts and electronic pathology (e-Path) reports securely transmitted to the SEER registries. Although scoring and staging data are captured and made available through the registries, there have been numerous studies that showed a high level of inter-observer variability among the diagnostic classifications rendered by pathologists, which can potentially give rise to biases when conducting population-wide studies. As the diagnosis of cancer and its immune response to therapy is made through tissue studies, the integration of pathology imaging in SEER registries is critical to precisely classify tumors and predict tumor response to therapies.

Fig. 7.

Pathology image workflow. WSIs are de-identified and analyzed by deep-learning analysis pipelines deployed in containers. Image data are linked to the SEER Registry database to enhance it with quantitative imaging features (such as TIL distributions and tumor segmentations) extracted by deep-learning models. De-identified images and imaging features can then be used for data mining and research purposes.

Whole slide tissue scanning technologies have advanced significantly over the past 20 years.69 They are capable of imaging tissue specimens at high resolution in several minutes, and with advanced auto-focussing mechanisms and automated slide trays, they can process batches of tissue samples with little-to-no manual intervention. Several studies have evaluated the utility of imaged tissue data in pathology workflows.70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75 The Food and Drug Administration has approved a number of digital pathology systems for diagnostic use.76 We expect that digital pathology will be employed increasingly as part of routine pathology workflows at hospitals and medical research centers. As institutions adopt digital WSIs into their pathology workflows, we can envision that the images and molecular reports will also be securely transmitted to the SEER registries. Within the SEER registry, images will be automatically processed by the suite of feature extraction pipelines appropriate for the type of cancer. The SEER database will be enhanced with quantitative features and the accompanying pipeline distribution version. SEER*DMS will be used to link and integrate cancer abstracts, e-Path reports, WSIs, and Pathomics feature sets from all reporting facilities. De-identified images and annotations will then be extracted for data mining and research use. Our work on building a repository of curated WSIs and Pathomics features is an important step toward realizing this capability. Availability of tissue images and Pathomics datasets will also provide an invaluable resource for medical education and Pathology training as well as to facilitate multi-disciplinary approaches, improved quality control, and more efficient remote and collaborative access to tissue information.77,78

The first phase of our project focussed on the collection of cases and correlated pathology specimens from the archives of New Jersey State Cancer Registries and Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey and on targeted prostate and NSCLC cases. To date, we have established a repository of (1) high-quality digitized pathology images for subjects whose data are already being routinely collected by the collaborating registries and (2) Pathomics features consisting of patterns of TILs, tumor region segmentations and classifications, and segmented nuclei. We have completed the initial linkages with registry data, thus enabling the creation of information rich, population cohorts containing objective imaging and clinical attributes that can be mined. As part of the second phase of the effort, we have increased the number of contributing state registries to include Georgia, Kentucky, and New York and we have simultaneously expanded the scope of cancers under study by including melanoma, breast, and colorectal cancers. We will also build upon our team’s previous research efforts to design, develop, and optimize algorithms and methods that can quickly and reliably search through a growing reference library of cases to automatically identify and retrieve previously analyzed lesions which exhibit the most similar characteristics to a given query case for clinical decision support20, 21, 22,25,79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86 and to conduct more granular comparisons of tumors within and across patient populations. One of the potential advantages of this approach over purely alphanumeric search strategies is that it will enable investigators to systematically interrogate the data while visualizing the most relevant digitized pathology specimens.32,33

As part of the next phase of our project, we plan to investigate the automated nature of the full range of algorithms and methods for their capacity to enable clinicians and investigators to quickly and reliably answer questions such as: (a) What level of morphological variations are detected among a given set of tumors or specimens? (b) What changes in computational biomarker signatures occur at onset and key stages of disease progression? (c) What is the likely prognosis for a given patient population?

Software availability

The QuIP software and analysis methods are available as open-source codes for use by other research groups. The QuIP software platform can be downloaded and built from https://github.com/SBU-BMI/quip_distro.

The codes for the analysis methods can be accessed from links at https://github.com/SBU-BMI/histopathology_analysis.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work is supported, in part, by UG3CA225021, UH3CA225021, U24 CA215109, U24CA180924-01A1, and 5UL1TR003017 grants from the National Institutes of Health and generous contributions to Stony Brook from Bob Beals and Betsy Barton. Additional support was provided through funding from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs - Boston Healthcare System through contract, IPA-RU-092920. This work leveraged resources from XSEDE, which is supported by NSF ACI-1548562 grant, including the Bridges system (NSF ACI-1445606) at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center. Services, results and/or products in support of the research were generated by Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey Biomedical Informatics Shared Resource NCI-CCSG P30CA072720-5917.

Declaration of Competing Interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Allsbrook W.C., Jr., Mangold K.A., Johnson M.H., Lane R.B., Lane C.G., Epstein J.I. Interobserver reproducibility of Gleason grading of prostatic carcinoma: General pathologist. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:81–88. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2001.21135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berney D.M., Algaba F., Camparo P., et al. The reasons behind variation in Gleason grading of prostatic biopsies: Areas of agreement and misconception among 266 European pathologists. Histopathology. 2014;64:405–411. doi: 10.1111/his.12284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bueno-de-Mesquita J.M., Nuyten D.S., Wesseling J., van Tinteren H., Linn S.C., van de Vijver M.J. The impact of inter-observer variation in pathological assessment of node-negative breast cancer on clinical risk assessment and patient selection for adjuvant systemic treatment. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:40–47. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grilley-Olson J.E., Hayes D.N., Moore D.T., et al. Validation of interobserver agreement in lung cancer assessment: Hematoxylin-eosin diagnostic reproducibility for non-small cell lung cancer: The 2004 World Health Organization classification and therapeutically relevant subsets. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013;137:32–40. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2012-0033-OA. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matasar M.J., Shi W., Silberstien J., et al. Expert second-opinion pathology review of lymphoma in the era of the World Health Organization classification. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:159–166. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muenzel D., Engels H.P., Bruegel M., Kehl V., Rummeny E.J., Metz S. Intra- and inter-observer variability in measurement of target lesions: Implication on response evaluation according to RECIST 1.1. Radiol. Oncol. 2012;46:8–18. doi: 10.2478/v10019-012-0009-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakazato Y., Maeshima A.M., Ishikawa Y., et al. Interobserver agreement in the nuclear grading of primary pulmonary adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:736–743. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318288dbd8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Netto G.J., Eisenberger M., Epstein J.I. TAX 3501 Trial Investigators. Interobserver variability in histologic evaluation of radical prostatectomy between central and local pathologists: Findings of TAX 3501 multinational clinical trial. Urology. 2011;77:1155–1160. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.08.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rizzardi A.E., Johnson A.T., Vogel R.I., et al. Quantitative comparison of immunohistochemical staining measured by digital image analysis versus pathologist visual scoring. Diagn Pathol. 2012;7:42. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-7-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roggli V.L., Vollmer R.T., Greenberg S.D., McGavran M.H., Spjut H.J., Yesner R. Lung cancer heterogeneity: A blinded and randomized study of 100 consecutive cases. Hum Pathol. 1985;16:569–579. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(85)80106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sørensen J.B., Hirsch F.R., Gazdar A., Olsen J.E. Interobserver variability in histopathologic subtyping and grading of pulmonary adenocarcinoma. Cancer. 1993;71:2971–2976. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19930515)71:10<2971::aid-cncr2820711014>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warth A., Stenzinger A., von Brünneck A.C., et al. Interobserver variability in the application of the novel IASLC/ATS/ERS classification for pulmonary adenocarcinomas. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1221–1227. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00219211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilkins B.S., Erber W.N., Bareford D., et al. Bone marrow pathology in essential thrombocythemia: Interobserver reliability and utility for identifying disease subtypes. Blood. 2008;111:60–70. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-05-091850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yoon S.H., Kim K.W., Goo J.M., Kim D.W., Hahn S. Observer variability in RECIST-based tumour burden measurements: A meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2016;53:5–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett J.M. The FAB/MIC/WHO proposals for the classification of the chronic lymphoid leukemias. Rev Clin Exp Hematol. 2002;6:330–334. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-0734.2002.00301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Head D.R., Savage R.A., Cerezo L., et al. Reproducibility of the French-American-British classification of acute leukemia: The Southwest Oncology Group Experience. Am J Hematol. 1985;18:47–57. doi: 10.1002/ajh.2830180108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baumann I., Nenninger R., Harms H., et al. Image analysis detects lineage-specific morphologic markers in leukemic blast cells. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;105:23–30. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/105.1.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabril M.Y., Yousef G.M. Informatics for practicing anatomical pathologists: Marking a new era in pathology practice. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:349–358. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2009.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wedman P., Aladhami A., Beste M., et al. A new image analysis method based on morphometric and fractal parameters for rapid evaluation of in situ mammalian mast cell status. Microsc Microanal. 2015;21:1573–1581. doi: 10.1017/S1431927615015342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foran D.J., Comaniciu D., Meer P., Goodell L.A. Computer-assisted discrimination among malignant lymphomas and leukemia using immunophenotyping, intelligent image repositories, and telemicroscopy. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2000;4:265–273. doi: 10.1109/4233.897058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang L., Tuzel O., Chen W., et al. Pathminer: A web-based tool for computer-assisted diagnostics in pathology. IEEE Trans Inf Technol Biomed. 2009;13:291–299. doi: 10.1109/TITB.2008.2008801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Foran D.J., Yang L., Chen W., et al. Imageminer: A software system for comparative analysis of tissue microarrays using content-based image retrieval, high-performance computing, and grid technology. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:403–415. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kurc T., Qi X., Wang D., et al. Scalable analysis of big pathology image data cohorts using efficient methods and high-performance computing strategies. BMC Bioinform. 2015;16:399. doi: 10.1186/s12859-015-0831-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren J., Karagoz K., Gatza M.L., et al. Recurrence analysis on prostate cancer patients with Gleason score 7 using integrated histopathology whole-slide images and genomic data through deep neural networks. J Med Imaging (Bellingham) 2018;5 doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.5.4.047501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen W., Meer P., Georgescu B., He W., Goodell L.A., Foran D.J. Image mining for investigative pathology using optimized feature extraction and data fusion. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2005;79:59–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cmpb.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Girolami I., Gambaro G., Ghimenton C., et al. Pre-implantation kidney biopsy: Value of the expertise in determining histological score and comparison with the whole organ on a series of discarded kidneys. J Nephrol. 2020;33:167–176. doi: 10.1007/s40620-019-00638-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu K.H., Zhang C., Berry G.J., et al. Predicting non-small cell lung cancer prognosis by fully automated microscopic pathology image features. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12474. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Romo-Bucheli D., Janowczyk A., Gilmore H., Romero E., Madabhushi A. Automated tubule nuclei quantification and correlation with oncotype DX risk categories in ER+ breast cancer whole slide images. Sci Rep. 2016;6:32706. doi: 10.1038/srep32706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leo P., Lee G., Shih N.N., Elliott R., Feldman M.D., Madabhushi A. Evaluating stability of histomorphometric features across scanner and staining variations: Prostate cancer diagnosis from whole slide images. J Med Imaging (Bellingham) 2016;3 doi: 10.1117/1.JMI.3.4.047502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cooper L.A., Gutman D.A., Chisolm C., et al. The tumor microenvironment strongly impacts master transcriptional regulators and gene expression class of glioblastoma. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:2108–2119. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen X.S., Wu J.Y., Huang O., et al. Molecular subtype can predict the response and outcome of Chinese locally advanced breast cancer patients treated with preoperative therapy. Oncol Rep. 2010;23:1213–1220. doi: 10.3892/or_00000752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck A.H., Sangoi A.R., Leung S., et al. Systematic analysis of breast cancer morphology uncovers stromal features associated with survival. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:108ra113. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jögi A., Vaapil M., Johansson M., Påhlman S. Cancer cell differentiation heterogeneity and aggressive behavior in solid tumors. Ups J Med Sci. 2012;117:217–224. doi: 10.3109/03009734.2012.659294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ojansivu V., Linder N., Rahtu E., et al. Automated classification of breast cancer morphology in histopathological images. Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng J., Mo X., Wang X., Parwani A., Feng Q., Huang K. Identification of topological features in renal tumor microenvironment associated with patient survival. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:1024–1030. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chennubhotla C., Clarke L.P., Fedorov A., et al. An assessment of imaging informatics for precision medicine in cancer. Yearb Med Inform. 2017;26:110–119. doi: 10.15265/IY-2017-041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Colen R., Foster I., Gatenby R., et al. NCI workshop report: Clinical and computational requirements for correlating imaging phenotypes with genomics signatures. Transl Oncol. 2014;7:556–569. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2014.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo X., Zang X., Yang L., et al. Comprehensive computational pathological image analysis predicts lung cancer prognosis. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:501–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang C., Pécot T., Zynger D.L., Machiraju R., Shapiro C.L., Huang K. Identifying survival associated morphological features of triple negative breast cancer using multiple datasets. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20:680–687. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2012-001538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thorsson V., Gibbs D.L., Brown S.D., et al. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. The immune landscape of cancer. Immunity. 2019;51:411–412. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tille J.C., Vieira A.F., Saint-Martin C., et al. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes are associated with poor prognosis in invasive lobular breast carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2020;33:2198–2207. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-0561-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amgad M., Stovgaard E.S., Balslev E., et al. International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group. Report on computational assessment of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes from the International Immuno-Oncology Biomarker Working Group. NPJ. Breast Cancer. 2020;6:16. doi: 10.1038/s41523-020-0154-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koh J., Kim S., Kim M.Y., Go H., Jeon Y.K., Chung D.H. Prognostic implications of intratumoral CD103+ tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in pulmonary squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:13762–13769. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eriksen A.C., Sørensen F.B., Lindebjerg J., et al. The prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in stage II colon cancer. A nationwide population-based study. Transl Oncol. 2018;11:979–987. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zito Marino F., Ascierto P.A., Rossi G., et al. Are tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes protagonists or background actors in patient selection for cancer immunotherapy? Exp Opin Biol Ther. 2017;17:735–746. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2017.1309387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Saltz J., Sharma A., Iyer G., et al. A containerized software system for generation, management, and exploration of features from whole slide tissue images. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e79–e82. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharma A., Tarbox L., Kurc T., et al. PRISM: A platform for imaging in precision medicine. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4:491–499. doi: 10.1200/CCI.20.00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Foran D.J., Chen W., Chu H., et al. Roadmap to a comprehensive clinical data warehouse for precision medicine applications in oncology. Cancer Inform. 2017;16 doi: 10.1177/1176935117694349. (1176935117694349) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Madabhushi A., Lee G. Image analysis and machine learning in digital pathology: Challenges and opportunities. Med Image Anal. 2016;33:170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2016.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang S., Yang D.M., Rong R., Zhan X., Xiao G. Pathology image analysis using segmentation deep learning algorithms. Am J Pathol. 2019;189:1686–1698. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2019.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bozorgtabar B., Mahapatra D., Zlobec I., Rau T.T., Thiran J.P. Editorial: Computational pathology. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020;7:245. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Deng S., Zhang X., Yan W., et al. Deep learning in digital pathology image analysis: A survey. Front Med. 2020;14:470–487. doi: 10.1007/s11684-020-0782-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Niazi M.K.K., Parwani A.V., Gurcan M.N. Digital pathology and artificial intelligence. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:e253–e261. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30154-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gurcan M.N., Boucheron L.E., Can A., Madabhushi A., Rajpoot N.M., Yener B. Histopathological image analysis: A review. IEEE Rev Biomed Eng. 2009;2:147–171. doi: 10.1109/RBME.2009.2034865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Panayides A.S., Amini A., Filipovic N.D., et al. AI in medical imaging informatics: Current challenges and future directions. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform. 2020;24:1837–1857. doi: 10.1109/JBHI.2020.2991043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Abousamra S., Hou L., Gupta R., et al. Learning from thresholds: Fully automated classification of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes for multiple cancer types. arXiv. 2019 http://arxiv.org/abs/1907.03960 [updated 2019 Jul 9; cited 2021 Oct 19]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 57.Saltz J., Gupta R., Hou L., et al. Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Spatial organization and molecular correlation of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes using deep learning on pathology images. Cell Rep. 2018;23 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.086. (181-93.e7) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Le H., Samaras D., Kurc T., Gupta R., Shroyer K., Saltz J. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), October 13-17, 2019. Springer; Shenzhen, China. New York: 2019. Pancreatic cancer detection in whole slide images using noisy label annotations; pp. 541–549. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Le H., Gupta R., Hou L., et al. Utilizing automated breast cancer detection to identify spatial distributions of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in invasive breast cancer. Am J Pathol. 2020;190:1491–1504. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hou L., Agarwal A., Samaras D., Kurc T.M., Gupta R.R., Saltz J.H. Robust histopathology image analysis: To label or to synthesize? Proc IEEE Comput Soc Conf Comput Vis Pattern Recognit. 2019;2019:8533–8542. doi: 10.1109/CVPR.2019.00873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hou L., Gupta R., Van Arnam J.S., et al. Dataset of segmented nuclei in hematoxylin and eosin stained histopathology images of ten cancer types. Sci Data. 2020;7:185. doi: 10.1038/s41597-020-0528-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Simonyan K., Zisserman A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv. 2014 http://arxiv.org/abs/1409.1556 [updated 2015 Apr 10; cited 2021 Oct 19]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 63.Szegedy C., Ioffe S., Vanhoucke V., Alemi A. Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the impact of residual connections on learning. AAAI. 2017:31. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/AAAI/article/view/11231 Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 64.He K., Zhang X., Ren S., Sun J. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, June 27-30, 2016, Las Vegas, NV. IEEE; Piscataway, NJ: 2016. Deep residual learning for image recognition; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Falk T., Mai D., Bensch R., et al. U-net: Deep learning for cell counting, detection, and morphometry. Nat Methods. 2019;16:67–70. doi: 10.1038/s41592-018-0261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Goodfellow I.J., Pouget-Abadie J., Mirza M., et al. Generative adversarial networks. arXiv. 2014 http://arxiv.org/abs/1406.2661 [updated 2014 Jun 10; cited 2021 Oct 19]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 67.Graham S., Vu Q.D., Raza S.E.A., et al. HoVer-Net: Simultaneous segmentation and classification of nuclei in multi-tissue histology images. Med Image Anal. 2019;58 doi: 10.1016/j.media.2019.101563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.van Griethuysen J.J.M., Fedorov A., Parmar C., et al. Computational radiomics system to decode the radiographic phenotype. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e104–e107. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pantanowitz L., Sharma A., Carter A.B., Kurc T., Sussman A., Saltz J. Twenty years of digital pathology: An overview of the road travelled, what is on the horizon, and the emergence of vendorneutral archives. J Pathol Inform. 2018;9:40. doi: 10.4103/jpi.jpi_69_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Brunelli M., Beccari S., Colombari R., et al. iPathology cockpit diagnostic station: Validation according to College of American Pathologists Pathology and Laboratory Quality Center recommendation at the hospital trust and University of Verona. Diagn Pathol. 2014;9(suppl 1):S12. doi: 10.1186/1746-1596-9-S1-S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Griffin J., Treanor D. Digital pathology in clinical use: Where are we now and what is holding us back? Histopathology. 2017;70:134–145. doi: 10.1111/his.12993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zarella M.D., Bowman D., Aeffner F., et al. A practical guide to whole slide imaging: A white paper from the digital pathology association. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143:222–234. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2018-0343-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Aeffner F., Zarella M.D., Buchbinder N., et al. Introduction to digital image analysis in wholeslide imaging: A white paper from the Digital Pathology Association. J Pathol Inform. 2019;10:9. doi: 10.4103/jpi.jpi_82_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee J.J., Jedrych J., Pantanowitz L., Ho J. Validation of digital pathology for primary histopathological diagnosis of routine, inflammatory dermatopathology cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:17–23. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pantanowitz L., Michelow P., Hazelhurst S., et al. A digital pathology solution to resolve the tissue floater conundrum. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2021;145:359–364. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2020-0034-OA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Evans A.J., Bauer T.W., Bui M.M., et al. US Food and Drug Administration approval of whole slide imaging for primary diagnosis: A key milestone is reached and new questions are raised. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2018;142:1383–1387. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2017-0496-CP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Eccher A., Neil D., Ciangherotti A., et al. Digital reporting of whole-slide images is safe and suitable for assessing organ quality in preimplantation renal biopsies. Hum Pathol. 2016;47:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cima L., Brunelli M., Parwani A., et al. Validation of remote digital frozen sections for cancer and transplant intraoperative services. J Pathol Inform. 2018;9:34. doi: 10.4103/jpi.jpi_52_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tuzel O., Yang L., Meer P., Foran D.J. Classification of hematologic malignancies using texton signatures. Pattern Anal Appl. 2007;10:277–290. doi: 10.1007/s10044-007-0066-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cukierski W.J., Nandy K., Gudla P., et al. Ranked retrieval of segmented nuclei for objective assessment of cancer gene repositioning. BMC Bioinform. 2012;13:232. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-13-232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Qi X., Wang D., Rodero I., et al. Content-based histopathology image retrieval using CometCloud. BMC Bioinform. 2014;15:287. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-15-287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Yang L., Qi X., Xing F., Kurc T., Saltz J., Foran D.J. Parallel content-based sub-image retrieval using hierarchical searching. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:996–1002. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Chen W., Schmidt C., Parashar M., Reiss M., Foran D.J. Decentralized data sharing of tissue microarrays for investigative research in oncology. Cancer Inform. 2007;2:373–388. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang L., Chen W., Meer P., Salaru G., Feldman M.D., Foran D.J. High throughput analysis of breast cancer specimens on the grid. Med Image Comput Comput Assist Interv. 2007;10:617–625. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75757-3_75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Qi X., Kim H., Xing F., Parashar M., Foran D.J., Yang L. The analysis of image feature robustness using CometCloud. J Pathol Inform. 2012;3:33. doi: 10.4103/2153-3539.101782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chen Y., McGee J., Chen X., et al. Identification of druggable cancer driver genes amplified across TCGA datasets. PLoS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]