Abstract

Observing sexual behaviour change over time could help develop behavioural HIV prevention interventions for female sex workers in Zambia, where these interventions are lacking. We investigated the evolution of consistent condom use among female sex workers and their clients and steady partners. Participants were recruited into an HIV incidence cohort from 2012 to 2017. At each visit, women received HIV counselling and testing, screening for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and free condoms. Our outcome was reported consistent (100%) condom use in the previous month with steady partners, repeat clients, and non-repeat clients. Consistent condom use at baseline was highest with non-repeat clients (36%) followed by repeat clients (27%) and steady partners (17%). Consistent condom use between baseline and Month 42 increased by 35% with steady partners, 39% with repeat clients and 41% with non-repeat clients. Access to condoms, HIV/STI counselling and testing promoted positive sexual behaviour change.

Keywords: female sex workers, cohort study, condom use, risk behaviour, Zambia

INTRODUCTION

Female sex workers (FSWs) are hard-hit by the HIV epidemic in Zambia, where the national HIV prevalence is 11.3% but as high as 49% among FSWs (1). Socioeconomic factors including poverty, low levels of education and social disruption lead certain women in sub-Saharan Africa into sex work (2,3). FSWs tend to have multiple concurrent partners, use alcohol before sex, suffer violence and have condomless sex, which increases their risk of acquiring and transmitting HIV and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) (2,4).

The World Health Organisation recommends consistent condom use as an HIV prevention method for key populations (5). Biomedical interventions such as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), though effective at preventing HIV, do not protect against other STIs, pose problems of adherence, and are in short supply in sub-Saharan Africa (6–8). Condoms, when used consistently and correctly, are effective at preventing STIs, including HIV (9). Condom use by FSWs depends on many factors including sociodemographic background, knowledge of condom use benefits, partner’s beliefs about condom use and partner type (10–12).Typically, FSWs use condoms more consistently with casual clients than with regular clients and even less with non-paying partners (13–16).

Although behavioural intervention studies among FSWs in sub-Saharan Africa have shown an increase in condom use over time, cohort studies – which allow researchers to observe changes in sexual risk behaviour over time – are scarce among FSWs in Zambia (17). Participating in cohort studies, where FSWs have face-to-face interviews with study staff around sexual activity, improves the mental health of FSWs, which can then engender HIV-preventive behaviour (18,19). Observing how condom use by FSWs changes over time could thus help define behavioural interventions for FSWs in Zambia, where coverage of such interventions is low. Here, we present the results of a five-year HIV incidence cohort study investigating the evolution and predictors of consistent condom use by FSWs with their partners.

METHODS

Study Design

This sub-study is part of a larger prospective cohort study to determine HIV incidence and risk factors in a cohort of high-risk women described by Kilembe et al (20). The study began in September 2012 with open enrolment through 2015 and follow-up through September 2017. Follow-up visits occurred one month after enrolment, two months later and every three months thereafter. The study offered sexual and reproductive health services (see study procedures section) to all participants at every visit. Participants must have completed enrolment procedures and attended at least one follow-up visit to be eligible for analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Flowchart showing Zambian female sex workers who were eligible for analysis (N=389)

Study Participants

Women were eligible for enrolment in this study if they reported currently exchanging sex for money. Additional eligibility criteria included being HIV-negative, aged between 18 and 45 years, and available for follow-up throughout the study.

Ethics

The Emory University Institutional Review Board (IRB00071160) and the University of Zambia Research Ethics Committee (REF. No. 011-01-14) approved this study. All enrolled participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

Study Procedures

From September 2012 to May 2015, 16 trained community health workers and 12 peer sex workers recruited FSWs from known hotspots, including bars, lodges and streets, in Lusaka and Ndola. Recruiters distributed invitations to FSWs, inviting them to the Zambia-Emory HIV Research Project for voluntary HIV counselling and testing. Interested participants were then screened for HIV (rapid antibody tests for detection and antigen test for confirmation) at the research project; individuals who tested positive for HIV were referred to government antiretroviral clinics for further assessment, while individuals who tested negative for HIV and met previously mentioned eligibility criteria were enrolled in an HIV-incidence cohort. Women who seroconverted during the study were censored and referred to government antiretroviral clinics for further assessment.

At enrolment, nurses trained in psychosocial counselling administered face-to-face questionnaires to participants, collecting information on demographics and HIV risk factors in the preferred language of the participant (English, Nyanja or Bemba). Study participants returned one month after enrolment, two months later and quarterly thereafter. At subsequent visits, participants completed a face-to-face follow-up questionnaire with repeated questions on HIV risk behaviour the previous month. Women who reported no longer practicing sex work were withdrawn from the study. Nurses provided HIV counselling with free condoms, and the choice of long-acting reversible contraceptives (intrauterine device or hormonal implant) to eligible participants at every visit. At every visit, women received pregnancy tests and screening for syphilis (rapid plasma reagin serology) and trichomoniasis (vaginal swab microscopy), with free treatment provided when necessary. At the study site, FSWs were given food, beverages and travel reimbursement (50 Zambian Kwacha or 3 US Dollars).

Study Outcome

At enrolment and all follow-up visits, participants were asked how many times in the previous month they had sex with three partner types: steady partners (who FSWs had sex with regularly but not in exchange for money), repeat clients (from whom FSWs received money for sex more than once), and non-repeat clients (from whom FSWs received money for sex only once). Women were then asked a follow up question on how many of those sexual encounters involved use of a condom. This numerical information was used to create three categories classifying participants as always, sometimes or never using condoms with a given type of partner at a given time point.

Our response variable was consistent (100%) condom use by participants with their partners during vaginal, anal and oral sex. We combined all types of sexual encounters because participants reported very few anal (0.75%) and oral (0.81%) sex acts, which on their own had negligible statistical power. This repeated outcome measure was binary, with condom use coded “consistent” for women who reported always using condoms with a given type of partner during a given visit, and condom use coded “inconsistent” for women who reported not always using condoms with a given type of partner during a given visit. We dichotomised condom use into consistent versus inconsistent based on the long established literature showing that consistent condom use prevents HIV infection among serodiscordant couples (21). To compare consistent condom use by partner type at each visit, we calculated the proportion of reported sexual acts the previous month with a client or steady partner that always involved use of a condom.

Independent Variables

Independent variables fell under three categories: demographics, HIV risk factors, and sexual and reproductive health screening. Demographics were city of residence, age (years) and level of education. HIV risk factor variables were number of partners, condom use with partners and ever using alcohol. Sexual and reproductive health screening variables were pregnancy, syphilis and trichomoniasis test results. Time varying covariates were condom use, number of partners, and pregnancy and STI test results.

Statistical Analysis

In the descriptive phase, we calculated frequencies and percentages for all categorical variables tested; we also computed medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for all continuous variables tested. Reported consistent condom use in the prior month is displayed at baseline and subsequent study visits. Our cut-off point for analytical follow-up time was visit month 42 as this corresponds to the 75th percentile of the median study duration and covers 98% of the data reported for consistent condom use. We used the Mann-Kendall trend test, with significance set at p<0.05, to test the consistent condom use trend between baseline and Month 42. The null hypothesis for this test was that there was no significant consistent condom use trend between baseline and Month 42.

Since more than 10% of participants reported consistent condom use at all time points in this study, we used a Poisson regression with generalised estimation equation to estimate the relative risk of consistent condom use. The generalised estimation equation was chosen for of its ability to take into account non-independence of our repeated outcome and its robustness in estimating inference of coefficients in the final model (22). In our bivariate analysis, we used a significance level of p<0.05 to determine the factors associated with reported consistent condom use in the prior month that we later included in a backward eliminated multivariable model. Time-varying covariates were measured at the same time points as the outcome. We computed adjusted incidence rate ratios (IRR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) to estimate the relative risk of consistent condom use in our final multivariable model. All statistical analyses employed Stata version 14.2 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

RESULTS

Overall, we included 389 women in our analysis (Figure 1). Table 1 summarises baseline characteristics of the 389 FSWs in this study. The majority of participants (67%) lived in Ndola as opposed to Lusaka. Most women (58%) had either primary school education or no education at all. The median age at enrolment was 23 (IQR: 20–28). At baseline, 39% of FSWs had a steady partner, 77% reported seeing repeat clients the previous month, and 80% reported seeing non-repeat clients the previous month. Overall, baseline consistent condom use was 15%. Consistent condom use at baseline was highest with non-repeat clients (36%) followed by repeat clients (27%) and steady partners (17%).

Table I:

Baseline characteristics of Zambian female sex workers (N=389)

| Variable | N (%) |

|---|---|

| City of residence | |

| Ndola | 262 (67) |

| Lusaka | 127 (33) |

| Age, median (IQR) | 23 (20–28) |

| Education | |

| None | 34 (9) |

| Primary | 190 (49) |

| Secondary or higher | 165 (42) |

| Have a steady partner | |

| No | 237 (61) |

| Yes | 151 (39) |

| Number of clients last month, median (IQR) | 5 (2–10) |

| Consistent (100%) condom use with steady partner last month N/A=237 | 20 (17) |

| Consistent (100%) condom use with repeat clients last month N/A=32 | 82 (27) |

| Consistent (100%) condom use with non-repeat clients last month N/A=23 | 111 (36) |

| Ever use alcohol | |

| No | 80 (21) |

| Yes | 307 (79) |

| Pregnant | |

| No | 311 (80) |

| Yes | 15 (4) |

| Syphilis | |

| Negative | 345 (89) |

| Positive | 44 (11) |

| Trichomonas vaginalis | |

| Negative | 343 (91) |

| Positive | 32 (9) |

Ns do not always equal total due to missing values; N/A= not applicable/partner not reported

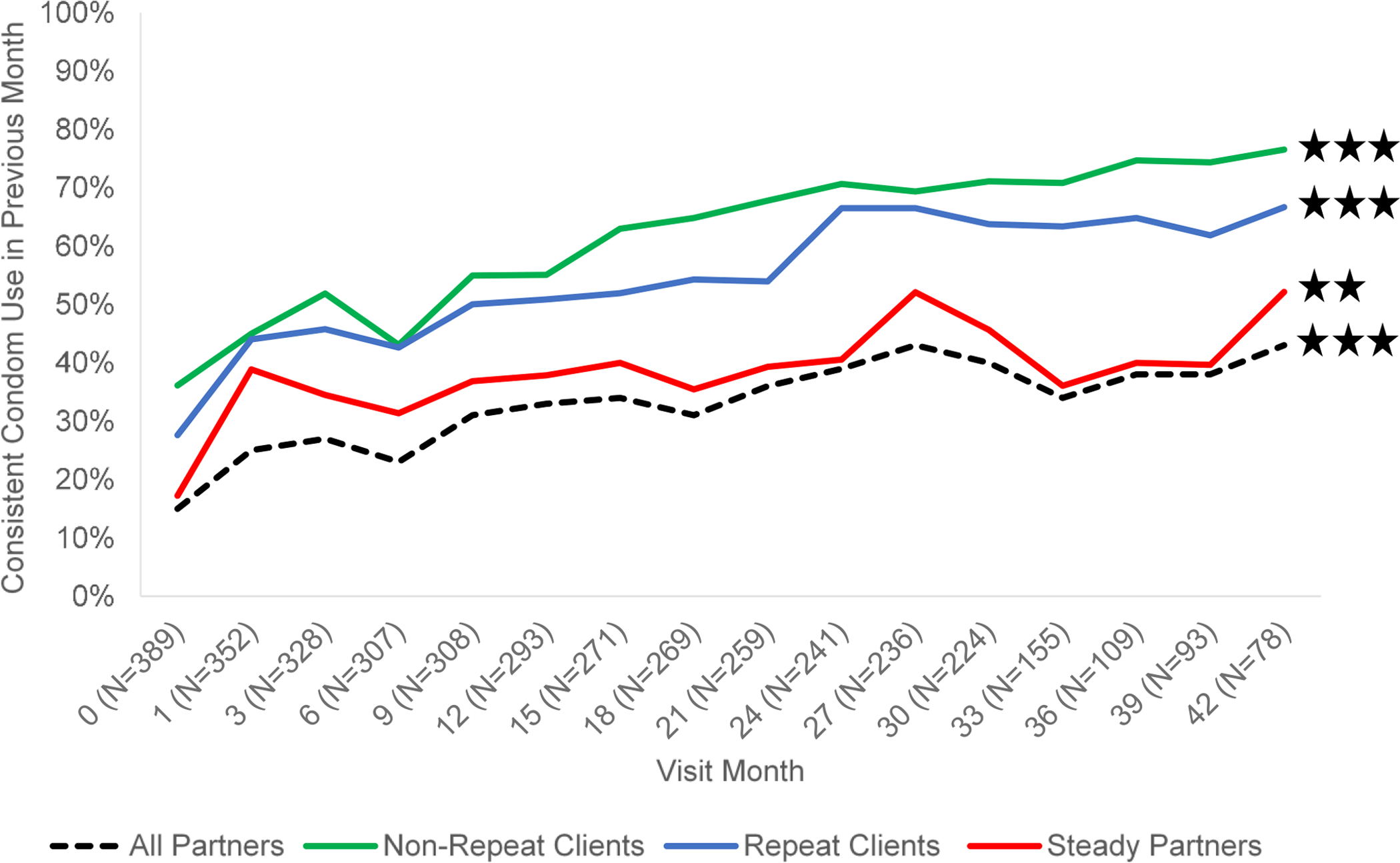

The median duration for participants in this study was 33.5 months (IQR: 30.2–42.7). Reported consistent condom use with all partners increased gradually throughout the study and remained highest with non-repeat clients and lowest with steady partners (Figure 2). Overall, consistent condom use increased by 28% between baseline and Month 42 (Mann-Kendall trend test, p<0.001). Consistent condom use between baseline and Month 42 increased by 35% with steady partners (Mann-Kendall trend test, p<0.01), 39% with repeat clients (p<0.001) and 41% with non-repeat clients (Mann-Kendall trend test, p<0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Condom use trend with all partners of Zambian female sex workers.

Mann-Kendall trend test: **p-value < 0.01, ***p-value < 0.001

Table 2 displays factors associated with consistent condom use. With each advancing study visit, the likelihood of consistent condom use with all partners increased by 2% (AIRR: 1.02, 95% CI: 1.02–1.03). Women living in Lusaka were almost four times as likely to report using condoms consistently than women living in Ndola (AIRR: 2.16, 95% CI: 1.75–2.67). Women who reported using condoms consistently had around a quarter reduced likelihood of testing positive for syphilis (AIRR: 0.76, 95% CI: 0.59–0.99) and falling pregnant (AIRR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.56–0.97). For every additional client seen the prior month, participants were 1% less likely to report consistent condom use (AIRR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.99–0.99). Women who ever used alcohol had 22% lower likelihood of consistent condom use than women who never used alcohol (AIRR: 0.78, 95% CI: 0.62–0.99).

Table II:

Factors associated with consistent condom use among Zambian female sex workers

| Consistent Condom Use in Previous Month | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | IRR | 95% CI | AIRR | 95% CI |

| Visit month# (per study visit advancement) | 1.02 | 1.02–1.03*** | 1.02 | 1.02–1.03*** |

| City of residence | ||||

| Ndola (ref) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Lusaka | 2.09 | 1.69–2.59*** | 2.16 | 1.75–2.68*** |

| Age (per one year increase) | 1.02 | 1.01–1.03* | - | - |

| Education | ||||

| None (ref) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Primary | 0.72 | 0.49–1.06 | - | - |

| Secondary or higher | 0.94 | 0.65–1.39 | - | - |

| Have a steady partner | ||||

| No (ref) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Yes | 1.13 | 0.90–1.42 | - | - |

| Number of clients last month# (per one client increase) | 0.99 | 0.98–0.99*** | 0.99 | 0.99–0.99** |

| Ever use alcohol | ||||

| No (ref) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Yes | 0.67 | 0.53–0.87** | 0.78 | 0.62–0.99* |

| Pregnant# | ||||

| No (ref) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Yes | 0.78 | 0.60–1.02 | 0.74 | 0.56–0.97* |

| Syphilis# | ||||

| Negative (ref) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Positive | 0.70 | 0.51–0.96* | 0.76 | 0.59–0.99* |

| Trichomonas vaginalis # | ||||

| Negative (ref) | 1 | - | 1 | - |

| Positive | 0.79 | 0.60–1.04 | - | - |

Ref= reference category;

time varying covariate

(A)IRR= (adjusted) incidence rate ratio; CI= confidence interval

p-value < 0.05,

p-value < 0.01,

p-value < 0.001

DISCUSSION

We found that reported consistent condom use by FSWs increased from baseline through follow-up with all types of partners. This indicates that FSWs in Zambia can adopt safer sexual practices after receiving regular HIV testing and counselling and HIV/STI prevention education. Similar to a previous study in Mexico, women in our study received HIV counselling and testing with free condoms every three months, which is likely to have encouraged less risky sexual behaviour (23). The pathway through which exposure to such services may have influenced condom use is illustrated in the literature; where behavioural interventions that combine health education and condom provision have been shown to increase condom use among FSWs in Africa (17). Our finding suggests that regular HIV/STI screening and prevention education with free condoms should be standard of care for FSWs enrolled in cohort studies.

The factors associated with consistent condom use in our study highlight the sexual and reproductive health vulnerability linked to inconsistent condom use. FSWs who reported using condoms inconsistently were more likely to report ever using alcohol, and to test positive for syphilis. Initial interactions between FSWs and clients tend to take place in areas where alcohol is served (24–26). Under the influence of alcohol, FSWs and their clients might engage in condomless sex, which elevates their risk of HIV and STIs such as syphilis (27–29). FSWs who used condoms inconsistently were significantly more likely to fall pregnant during our study; any unplanned pregnancies observed would call for dual method use – i.e. condoms with an additional modern contraceptive method – to protect against HIV, STIs and unintended pregnancy (30–32).

In line with previous studies, our results show a hierarchical difference in consistent condom use, which was highest with steady partners and lowest with non-repeat clients of FSWs (13–16). This finding suggests that intimacy and regularity are key influences on the sexual behaviour of FSWs. Much like women in past studies, FSWs are less likely to use condoms the longer a relationship lasts (33,34). This calls for tailoring of HIV risk reduction messaging to the partner profile of FSWs. Evidence from Zambian couples also suggests that counselling FSWs on HIV risk reduction jointly with their partners could be an effective prevention strategy (35).

Our findings have certain constraints. Firstly, condom use was self-reported and therefore subject to recall bias, which we minimised by limiting the reporting period to the previous month. Self-report of condom use was also potentially subject to social desirability bias, which could have led to participants overreporting condom use to study staff. Thirdly, our dichotomous condom use outcome considered all FSWs with less than 100% condom use as inconsistent condom users, which underestimated the overall increase in condom use. Our choice to dichotomise was, however, based on the literature showing the effectiveness of consistent condom use in preventing HIV infection (21). Lastly, due to this being a non-randomised study, it is difficult for us to determine why we observed an increase in consistent condom use. The repeated measures design of the study did though enhance the validity of our findings by reducing variability.

Despite its limitations, our study makes a valuable contribution to the literature. Our finding that participating in cohort studies with exposure to regular HIV counselling, testing and free condoms can increase condom use with paying and non-paying partners is key for FSWs in Zambia. Moreover, HIV research projects in Africa lack adequate integration of sexual and reproductive health services for FSWs (36). To strengthen current HIV prevention efforts for FSWs, research studies must integrate HIV counselling and testing, family planning, STI screening and PrEP (1).

CONCLUSION

We observed that Zambian FSWs in an HIV incidence study offering regular sexual and reproductive health services used condoms more consistently with all of their partners over time. This revealed the underexplored sexual health benefits of participating in cohort studies among FSWs in an HIV endemic setting. We recommend that condom provision, risk reduction counselling, HIV testing, and STI and pregnancy screening be deployed outside of research settings to minimise the HIV risk faced by FSWs. The hierarchical trend of condom use, which declined from casual to intimate partners, calls for differentiated HIV prevention interventions based on partner type. In settings where legal and healthcare systems marginalise sex workers, combining interventions with non-discriminatory policy will be necessary to meet the sexual and reproductive health needs of FSWs.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the support from the University of California, San Francisco’s International Traineeships in AIDS Prevention Studies (ITAPS), U.S. NIMH, R25MH123256.

Funding:

This study was supported by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) with the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID, https://www.usaid.gov/). A full list of IAVI donors can be found at https://www.iavi.org/; National Institutes of Health (https://www.nih.gov/) grants (R01 MH66767, R01 HD40125, and R01 MH95503; R01 AI051231); the AIDS International Training and Research Program Fogarty International Center (D43 TW001042); and the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409). The contents of this manuscript are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the US Government.

Footnotes

Conflicts: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare

Ethics: The Emory University Institutional Review Board (IRB00071160) and the University of Zambia Research Ethics Committee (REF. No. 011-01-14) approved this study.

Consent to participate: All enrolled FSWs provided written informed consent to participate in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNAIDS. UNAIDS Data 2019 [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland; 2019. [cited 2019 Dec 11]. Available from: https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2019-UNAIDS-data_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baral S, Beyrer C, Muessig K, Poteat T, Wirtz AL, Decker MR, et al. Burden of HIV among female sex workers in low-income and middle-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012. Jul;12(7):538–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scorgie F, Chersich MF, Ntaganira I, Gerbase A, Lule F, Lo Y-R. Socio-Demographic Characteristics and Behavioral Risk Factors of Female Sex Workers in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2012. May 1;16(4):920–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Malama K, Sagaon-Teyssier L, Parker R, Tichacek A, Sharkey T, Kilembe W, et al. Client-Initiated Violence Against Zambian Female Sex Workers: Prevalence and Associations With Behavior, Environment, and Sexual History: Journal of Interpersonal Violence [Internet]. 2019. Jul 3 [cited 2019 Oct 22]; Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/eprint/JV2HWHPXSKWEGMM5VAJY/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.World Health Organisation. WHO Expands Recommendation on Oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis of HIV Infection (PrEP) [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2015. [cited 2020 Jul 4]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/197906/WHO_HIV_2015.48_eng.pdf;jsessionid=0FF1F0C2002F493E392EB772FD8FE6DF?sequence=1 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cairns G. PrEP spreads across Africa – slowly [Internet]. United Kingdom: Aidsmap; 2018. [cited 2019 Oct 24]. Available from: http://www.aidsmap.com/news/aug-2018/prep-spreads-across-africa-slowly [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shea J, Bula A, Dunda W, Hosseinipour MC, Golin CE, Hoffman IF, et al. “THE DRUG WILL HELP PROTECT MY TOMORROW”: PERCEPTIONS OF INTEGRATING PREP INTO HIV PREVENTION BEHAVIORS AMONG FEMALE SEX WORKERS IN LILONGWE, MALAWI. AIDS Educ Prev. 2019. Oct;31(5):421–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emmanuel G, Folayan M, Undelikwe G, Ochonye B, Jayeoba T, Yusuf A, et al. Community perspectives on barriers and challenges to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis access by men who have sex with men and female sex workers access in Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2020. Jan 15;20(1):69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Charania MR, Crepaz N, Guenther-Gray C, Henny K, Liau A, Willis LA, et al. Efficacy of Structural-Level Condom Distribution Interventions: A Meta-Analysis of U.S. and International Studies, 1998–2007. AIDS Behav. 2011. Oct 1;15(7):1283–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Rossem R, Meekers D, Akinyemi Z. Consistent condom use with different types of partners: evidence from two Nigerian surveys. AIDS Educ Prev. 2001. Jun;13(3):252–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adu-Oppong A, Grimes RM, Ross MW, Risser J, Kessie G. Social and Behavioral Determinants of Consistent Condom Use Among Female Commercial Sex Workers in Ghana. AIDS Education and Prevention. 2007. Apr;19(2):160–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ntumbanzondo M, Dubrow R, Niccolai LM, Mwandagalirwa K, Merson MH. Unprotected intercourse for extra money among commercial sex workers in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. AIDS Care. 2006. Oct;18(7):777–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallo MF, Warner L, Bell AJ, Bukusi EA, Sharma A, Njoroge B, et al. Determinants of Condom Use Among Female Sex Workers in Kenya: A Case-Crossover Analysis. Journal of Women’s Health (15409996). 2011. May;20(5):733–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kayembe PK, Mapatano MA, Busangu AF, Nyandwe JK, Musema GM, Kibungu JP, et al. Determinants of consistent condom use among female commercial sex workers in the Democratic Republic of Congo: implications for interventions. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 2008. Jun 1;84(3):202–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinsler JJ, Blas MM, Cabral A, Carcamo C, Halsey N, Brown B. Understanding STI Risk and Condom Use Patterns by Partner Type Among Female Sex Workers in Peru. Open AIDS J. 2014. May 30;8:17–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fehrenbacher AE, Chowdhury D, Jana S, Ray P, Dey B, Ghose T, et al. Consistent Condom Use by Married and Cohabiting Female Sex Workers in India: Investigating Relational Norms with Commercial Versus Intimate Partners. AIDS Behav. 2018. Dec 1;22(12):4034–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okafor UO, Crutzen R, Aduak Y, Adebajo S, Van den Borne HW. Behavioural interventions promoting condom use among female sex workers in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2017. Jul 3;16(3):257–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunn JKL, Roth AM, Center KE, Wiehe SE. The Unanticipated Benefits of Behavioral Assessments and Interviews on Anxiety, Self-Esteem and Depression Among Women Engaging in Transactional Sex. Community Ment Health J. 2016. Nov 1;52(8):1064–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chudakov B, Ilan K, Belmaker RH, Cwikel J. The motivation and mental health of sex workers. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002. Sep;28(4):305–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kilembe W, Inambao M, Sharkey T, Wall KM, Parker R, Himukumbwa C, et al. Single Mothers and Female Sex Workers in Zambia Have Similar Risk Profiles. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 2019. Jun 17;35(9):814–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Vincenzi I. A longitudinal study of human immunodeficiency virus transmission by heterosexual partners. European Study Group on Heterosexual Transmission of HIV. N Engl J Med. 1994. Aug 11;331(6):341–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hubbard AE, Ahern J, Fleischer NL, der Laan MV, Lippman SA, Jewell N, et al. To GEE or Not to GEE: Comparing Population Average and Mixed Models for Estimating the Associations Between Neighborhood Risk Factors and Health. Epidemiology. 2010. Jul;21(4):467–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tracas A, Bazzi AR, Artamonova I, Rangel MG, Staines H, Ulibarri MD. Changes in Condom Use over Time among Female Sex Workers and their Male Noncommerical Partners and Clients. AIDS Educ Prev. 2016. Aug;28(4):312–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Q, Li X, Stanton B. Alcohol Use Among Female Sex Workers and Male Clients: An Integrative Review of Global Literature. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010. Mar 1;45(2):188–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fritz KE, Woelk GB, Bassett MT, McFarland WC, Routh JA, Tobaiwa O, et al. The Association Between Alcohol Use, Sexual Risk Behavior, and HIV Infection Among Men Attending Beerhalls in Harare, Zimbabwe. AIDS and Behavior. 2002;8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roth EA, Benoit C, Jansson M, Hallsgrimdottir H. Public Drinking Venues as Risk Environments: Commercial Sex, Alcohol and Violence in a Large Informal Settlement in Nairobi, Kenya. Human Ecology. 2017. Apr;45(2):277–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chersich MF, Luchters SMF, Malonza IM, Mwarogo P, King’ola N, Temmerman M. Heavy episodic drinking among Kenyan female sex workers is associated with unsafe sex, sexual violence and sexually transmitted infections. Int J STD AIDS. 2007. Nov;18(11):764–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chersich MF, Bosire W, King’ola N, Temmerman M, Luchters S. Effects of hazardous and harmful alcohol use on HIV incidence and sexual behaviour: a cohort study of Kenyan female sex workers. Global Health. 2014. Apr 3;10:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang B, Li X, Stanton B, Zhang L, Fang X. Alcohol Use, Unprotected Sex, and Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Female Sex Workers in China. Sex Transm Dis. 2010. Oct;37(10):629–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feldblum PJ, Nasution MD, Hoke TH, Damme KV, Turner AN, Gmach R, et al. Pregnancy among sex workers participating in a condom intervention trial highlights the need for dual protection. Contraception. 2007. Aug 1;76(2):105–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mbita G, Mwanamsangu A, Plotkin M, Casalini C, Shao A, Lija G, et al. Consistent Condom Use and Dual Protection Among Female Sex Workers: Surveillance Findings from a Large-Scale, Community-Based Combination HIV Prevention Program in Tanzania. AIDS Behav [Internet]. 2019. Aug 23 [cited 2019 Sep 19]; Available from: 10.1007/s10461-019-02642-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li JL, Kilembe W, Inambao M, Vwalika B, Parker R, Sharkey T, et al. Fertility intentions and long-acting reversible contraceptive use among HIV-negative single mothers in Zambia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020. Apr;222(4S):S917.e1–S917.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Macaluso M, Demand MJ, Artz LM, Hook EWI. Partner type and condom use. AIDS. 2000. Mar 31;14(5):537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Duncan EAW. Influence of Partner Type on Condom Use. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2011. Oct 31;21(7):784–802. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Malama K, Kilembe W, Inambao M, Hoagland A, Sharkey T, Parker R, et al. A couple-focused, integrated unplanned pregnancy and HIV prevention program in urban and rural Zambia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020. Apr;222(4S):S915.e1–S915.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dhana A, Luchters S, Moore L, Lafort Y, Roy A, Scorgie F, et al. Systematic review of facility-based sexual and reproductive health services for female sex workers in Africa. Global Health. 2014. Jun 10;10:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]