Abstract

Objectives:

1) To describe activation skills of African American parents on behalf of their children with mental health needs. 2) To assess the association between parent activation skills and child mental health service use.

Methods:

Data obtained in 2010 and 2011 from African American parents in North Carolina raising a child with mental health needs (n = 325) were used to identify child mental health service use from a medical provider, counselor, therapist, or any of the above or if the child had ever been hospitalized. Logistic regression was used to model the association between parent activation and child mental health service use controlling for predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics of the family and child.

Results:

Mean parent activation was 65.5%. Over two-thirds (68%) of children had seen a medical provider, 45% had seen a therapist, and 36% had seen a counselor in the past year. A quarter (25%) had been hospitalized. A 10-unit increase in parent activation was associated with a 31% higher odds that a child had seen any outpatient provider for their mental health needs (odds ratio = 1.31, confidence interval = 1.03-1.67, p = 0.03). The association varied by type of provider. Parent activation was not associated with seeing a counselor or a therapist or with being hospitalized.

Conclusion:

African American families with activation skills are engaged and initiate child mental health service use. Findings provide a rationale for investing in the development and implementation of interventions that teach parent activation skills and facilitate their use by practices in order to help reduce disparities in child mental health service use.

Keywords: African American, child and adolescent, mental health service use, parent activation

INTRODUCTION

African American families of children with mental health needs are 30 to 60% more likely than white families to report an unmet need for care.1 In keeping with this concern, their children are 20 to 50% as likely as white children to use outpatient mental health services.2-5 As a result, African American families also experience delays in treatment that can lead to poorer outcomes.6 In addition, the prevalence of mental, behavioral, and developmental disorders in children from lower-income households is estimated at 22.1%, which is substantially higher than the 13.9% rate in higher-income households.7

To describe parents’ skills in advocating for their children’s mental health needs, researchers describe a sequential model of help-seeking.8,9 Help-seeking begins with problem recognition, then parent assessment of when issues can be managed at home and when the problem requires help, followed by help-seeking from a broad social network (family; friends; and religious, school, primary care, and specialty mental health service providers) where services may be obtained from multiple providers.10 The process of seeking and receiving is not linear but proceeds along multiple branches of the network simultaneously. At any point in time, a family may be at different stages of the help-seeking process relative to a particular service or source of help. Factors that have been linked to lower use of mental health services among African Americans include stigma, limited trust in behavioral health providers, limited familial support, religiosity or spirituality, and cultural beliefs.11 In addition, disadvantaged children have been found to be less likely to use mental health services when they experienced practical obstacles such as moving too far away from a provider, a parental job change, or moving to a different home.12

There is evidence of a number of experiences, attitudes, and skills that can facilitate parent disease management and help-seeking to meet their children’s mental health needs or their own. Patient activation is a composite of attitudes, knowledge, and skills that reflect a person’s readiness and ability to take on the role of managing both mental health and health care.13 Activation is defined as self-efficacy in self-management of chronic disease, knowing when and where to go for help, and getting one’s needs met in a health care visit.14 Because activation is independent of education and income, it holds promise for addressing disparities faced by African American parents.15 Parent activation is defined similarly to patient activation but indicates readiness and ability to manage one’s child’s health care. Parents’ experience with mental health symptoms, experience with service use, and recognition of a child’s need for mental health services are all associated with a greater likelihood of a child’s use of a mental health service.9,16,17 Parents also report that a good rapport and ease of communication with their primary care physician facilitate seeking help for their child’s mental health needs.18 Skill in chronic disease self-management (maintaining healthy behaviors, minimizing health risks, effective problem-solving, and planning) has been associated with greater physical health-related quality of life in adults with mental health needs.19 Disease management can also be used to describe the process whereby parents take an active role in fostering healthy behaviors and minimizing health risks for their children, problem-solving when health issues arise, and planning to ensure treatment adherence. Among adults with mental health needs, patient activation is associated with a greater likelihood of service use and adherence to treatment.20 Parent activation has also been associated with employment and with teacher report of successful postsecondary outcomes in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders.21

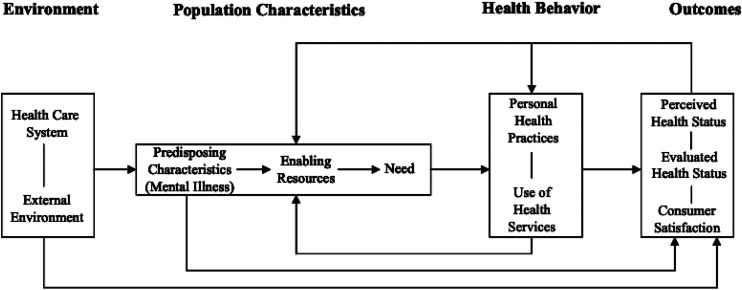

This paper describes activation skills of African American parents on behalf of their children with mental health needs. The goal is to assess the association between parent activation skills and child mental health service use. The analyses are framed by the Andersen Behavioral Model of Health Care Use, a widely used public health conceptual framework, where the predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics of the family and their child with mental health needs are associated with the child’s use of mental health services (Figure 1).22 This paper explores the hypothesis that parent activation is an enabling characteristic associated with child mental health service use, controlling for other predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics. The paper contributes to the literature through use of a unique dataset of African American children whose parents report emotional or developmental challenges with detailed information on parent self-report of activation skills and child mental health service use.

Figure 1.

Andersen behavioral model of health care use.22

METHODS

Participants

Data were compiled from African American parents living across North Carolina who had children for whom they had concerns about emotional and developmental challenges (n = 325). In response to literature suggesting that African American families are less likely to describe children’s behavior as a mental health condition, the research team characterized mental health needs as “challenges” to capture broader conceptualizations of their child’s behavior.23 The goal was to obtain a sample of parents who recognized that their child was having challenges but who may or may not have obtained a formal diagnosis for their child from a clinician. Families who felt their children were experiencing such challenges were invited to participate by means of fliers distributed to local early intervention service agencies, county social services, school special education directors, mental health agencies, and advocacy organizations. Children were 21 years old or younger to include the full range of children who might still be in school. Besides age and parental concerns about mental health or developmental challenges, there were no other inclusion/exclusion criteria. Parents or other caregivers (hereafter referred to as parents) who were interested in participating called a toll-free number to provide contact information to the study team, including their demographic data. A letter of introduction was sent to each interested participant with a brief description of the interview protocol and $40 in appreciation for their participation.

Interested participants were called within a few days of receipt of this letter to proceed with the interview or schedule a time at their convenience. The call began with a description of the interview protocol and collection of informed consent to participate. Data were collected during the winter and spring of 2010 to 2011 through a computer-assisted phone interview lasting about 45 minutes with each respondent. Interviewers were African American women with expertise in computer-assisted telephone interviewing. Interviewer racial and gender concordance was designed to facilitate rapport-building and race-concordant trust with study participants. Interviews could be completed over several phone calls if necessary. Completed interviews were obtained for 62% (325 of 526) of the families who originally expressed an interest in participating. The remaining families were lost to follow-up. Children of participating families were more likely to have a serious mental health diagnosis and to be male but not different in age from children in nonparticipating families. The study protocol was approved by the Office of Human Research Ethics of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Measures

The outcome examined was child mental health service use. Four binary measures indicated whether the respondent had taken the child to specific types of providers in the past year for his/her emotional or developmental challenges: a medical provider (pediatrician, psychiatrist, other medical doctor, nurse practitioner or physician assistant), a counselor (psychologist, social worker, or other counselor), or a therapist (speech, physical, or occupational therapist), as well as a recoded variable indicating any of the above. Each required an affirmative answer to the question, “Have you seen a [provider] in the past year?”

The independent variable of interest is parent activation, which we measured with the Parent Patient Activation Measure (PPAM), which captured parent activation on behalf of their child.24,25 The original Patient Activation Measure (PAM) assesses self-reported attitudes, knowledge, skill and confidence managing one’s health or chronic disease.26 The PPAM is a self-report 13-item scale with 4-level Likert responses. It is a unidimensional measure with possible scores ranging from 0 to 100 that identify 4 levels of activation ranging from “disengaged and overwhelmed” (level 1) to “maintaining behaviors and pushing further” (level 4). It is valid with excellent reliability in general and condition-specific populations. In the present study it has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88. The PAM has been used to focus on mental health needs of adults and to explore activation in predominantly African American populations, but to our knowledge not at the same time.20,27,28 The PPAM has also been used to measure activation of parents on behalf of their children with mental health disorders (mean scores=66-70).25,28 Example items include, “With everything I have going on, it is hard for me to be very involved in the help my child is getting,” and “If I can get the right services, I feel confident that my child’s life and future will be better.” An increase of 4 points in the PAM is associated with meaningful improvement in health behaviors in the general population.29

Control variables captured predisposing, enabling and need characteristics from the Andersen Behavioral Model of Health Care Use.21 Predisposing characteristics included child age (in years) and sex (male), and family experience with mental health problems (a dichotomous measure indicating whether there were other adults or children in their household with emotional or developmental challenges). Enabling variables captured highest education level of household adults (less than high school, more than high school), household income (below $35,000 which falls in between 80 percent of the 2011 state median income and 150% of the federal poverty level for a family of four; or more than $35,000), and health insurance (any versus none). Need variables measured whether the child had a serious mental disorder (parent-reported diagnosis of a serious mood or anxiety disorder, psychosis, autism, traumatic brain injury or unspecified ‘serious mental health issues’) and whether the child’s school had created an individualized education plan.

Analytic methods

Unadjusted means of outcome measures are shown by parent activation level in levels 1-3 compared to level 4 (representing the highest level) as defined by the developers of the PAM. Logistic regression was used to model the association between parent activation and child mental health service use controlling for predisposing, enabling and need characteristics of the family and child. Separate models were estimated for each type of service use (medical provider, counselor, therapist, any outpatient use in the past year and any psychiatric hospitalization ever). To assess the model fit we computed the likelihood ratio test in each imputed dataset and pooled the test statistics to construct an overall likelihood ratio test statistic as described by Meng and Rubin. 30 The resulting test statistic was compared with the F distribution with appropriate degrees of freedom. Because single items were missing for between 1% (others at home with challenges) and 16% (child ever hospitalized) of the sample, multiple imputation was used to fill missing items. Before imputation, 22.2% of the subjects had at least 1 variable (that was used in the modeling) with missing values. Analyses were conducted using SAS software version 9.2.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows family and child characteristics of the sample of African American families living in North Carolina who reported having a child with mental health needs. Mean parent activation was 66 (standard deviation = 14, range = 38.7-100). There were 135 parents at level 4 of activation (42.6%), 108 (34.1%) at level 3, 56 (17.7%) at level 2, and 18 (5.7%) at level 1. Children ranged from 1 to 21 years of age, with a mean of 11.6 years.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 325)a

| % | Mean | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family characteristics | |||

| Parent activation | 65.5 | 14.3 | |

| Others in home with challenges (adults and children) | 34.4 | ||

| Highest education level of household adults | |||

| Less than high school | 11.7 | ||

| High school diploma | 29.3 | ||

| Some college | 37.3 | ||

| College diploma or higher | 21.9 | ||

| Household income | |||

| Less than $35,000 | 79.2 | ||

| $35,000-$50,000 | 13.1 | ||

| More than $50,000 | 7.7 | ||

| Child characteristics | |||

| Child mental health service use | |||

| Visited a medical provider in the past year | 67.5 | ||

| Visited a counselor in the past year | 35.9 | ||

| Visited a therapist in the past year | 45.1 | ||

| Any outpatient use in the past year | 80.3 | ||

| Ever hospitalized for mental health needs | 25.0 | ||

| Age | 11.6 | 5.2 | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 68.6 | ||

| Female | 31.4 | ||

| Health insurance | |||

| Any health insurance | 92.8 | ||

| Any Medicaid or SCHIP | 86.9 | ||

| Any private insurance | 8.3 | ||

| Serious mental health diagnosis | 41.2 | ||

| Child has an individualized education plan | 54.3 | ||

a N for all measures unless otherwise specified.

Over two-thirds (68%) of the children had seen a medical provider, nearly half (45%) had seen a therapist, and a third (36%) had seen a counselor in the past year. A quarter (25%) of the children had been hospitalized for mental health needs sometime in their lifetime. A majority of children (79%) lived in families where household income was less than $35,000. Likewise, a majority of children (87%) were covered by Medicaid or the state children’s health insurance program; 8% had private coverage.

Table 2 shows unadjusted outcome measures by parent activation levels 1, 2, and 3 versus level 4. Nearly all (91.5%) of children of high activation parents had used some outpatient mental health services in the past year, whereas only 78.8% of children of low activation parents had done so.

Table 2.

Outcomes by level of parent activation

| Outcome | Activation level 1-3, % (n = 182) | Activation level 4, % (n = 135) | p valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visited a medical provider | 60.6 | 77.0 | 0.002 |

| Visited a counselor | 32.9 | 41.5 | 0.12 |

| Visited a therapist | 42.5 | 50.8 | 0.17 |

| Any outpatient use | 78.8 | 91.5 | 0.001 |

| Ever hospitalized | 23.6 | 28.3 | 0.48 |

a Based on pooled χ2 statistic proposed by Rubin.42

Table 3 shows the odds of having any service use, by type, for an incremental increase in parent activation in the past year controlling for predisposing, enabling, and need characteristics of the family and child (child age, sex, serious mental health diagnosis status, covered by health insurance, has an individualized education plan; parent has less than high school education; others in the home with emotional or developmental challenges; and household income less than $35,000). A 10-unit increase in parent activation was associated with a 31% higher odds that a child would see any outpatient provider for their mental health needs (odds ratio [OR] = 1.31, confidence interval [CI] = 1.03-1.67, p = 0.03). The association varied by type of provider. A 10-unit increase in parent activation was associated with a 22% higher odds that a child had seen a medical provider (OR = 1.22, CI = 1.02-1.46, p = 0.03). Parent activation level was not significantly associated with seeing a counselor or a therapist or ever having had a psychiatric hospitalization. Each of the models achieved a significant improvement in fit over the null according to a likelihood ratio test.

Table 3.

Association between parent activation and child mental health service use

| Outcome | Odds ratioa (95% confidence interval) | PPAM p value | Model LR test p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visited a medical provider | 1.220 (1.019-1.461) | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Visited a counselor | 1.128 (0.944-1.348) | 0.18 | 0.002 |

| Visited a therapist | 1.189 (0.989-1.429) | 0.07 | < 0.0001 |

| Any outpatient use | 1.310 (1.027-1.670) | 0.03 | 0.009 |

| Ever hospitalized | 0.996 (0.797-1.244) | 0.97 | 0.0002 |

a Adjusted odds ratios reported for 10-point increase in parent activation.

Effects are adjusted for child age, sex, serious mental health diagnosis status, covered by health insurance, has an individualized education plan; parent has less than high school education; others in the home with emotional or developmental challenges, and household income less than $35,000.

LR = likelihood ration; PPAM = Parent Patient Activation Measure.

DISCUSSION

The research reported here examines the role of parent activation in child mental health service use among African American families. Logistic regressions of child mental health service use suggest that parent activation is associated with greater odds of the child using any outpatient services and seeing a medical provider (a pediatrician, psychiatrist, other medical doctor, nurse practitioner or physician assistant) in the past year. This association of activation skills and child mental health service use is consistent with findings that parent-identified need is an important predictor of mental health service use for African American and other families.10,16 Future work should examine how parents use activation skills. For example, these skills may facilitate initiation of mental health service use by choosing high-quality health insurance for their child and finding suitable providers.2,3,31

The level of parent activation reported here is similar to that measured in parents asked about their children and adults asked about managing their own health care. In a national sample of adults, the mean PAM score among African American adults was 65.32 The mean PPAM score among parents of children receiving special education services was 66,24 whereas the mean among Latino parents was 70.25 Those families were receiving mental health services in a Spanish-language mental health clinic, indicating they had already been successful in finding a culturally sensitive source of care, consistent with higher levels of activation. Among adults with serious mental illness participating in studies of recovery from mental illness, mean PAM scores at baseline were about 60.28 Because adults with chronic disease face more challenges managing their health, it is understandable that they would have lower activation than the parents in this sample.

Several limitations and benefits of the sample are worth noting. The findings reported here are derived from a convenience sample of African American parents with children with mental health needs; participants were recruited from a variety of clinical, educational, and public social service organizations. Diagnoses of mental health conditions are parent reported and could be either exaggerated or minimized by respondents. The primary outcome was whether the family made at least 1 visit, which does not necessarily mean that families sustained treatment to completion. The study design is unique in allowing the examination of parent-reported patient activation skills and child mental health service use in a large, targeted sample of a hard-to-reach population. As a result, descriptive statistics suggest that these families are different from a random sample in meaningful ways. Most notable is that children in this sample were over twice as likely to have used mental health services in the past year (80%) as were African American children from a national sample (32%).5 This finding is consistent with literature that suggests that, among children who have a serious mental health diagnosis, those with parent-identified behavior problems are more likely to receive mental health services than others.10,16 These families’ strong service system involvement underscores the appropriateness of this sample for learning about facilitators that support child mental health service use in African American families. Future work should examine the relationship between parent activation and child mental health service use in community samples of African American families over time.

Several findings reported here deserve particular attention. A majority of study sample children (87%) were covered by Medicaid or the state children’s health insurance program. Because Medicaid and state health insurance program coverage are available to families with fewer resources, the promising role of parent activation in obtaining services for their children in the low-income population examined here is of critical importance.

The fact that parent activation was significantly associated with use of a medical provider but not with seeing a counselor (defined as a psychologist, social worker, or other counselor) is counterintuitive in light of an expressed preference among African American families for mental health treatments that are not medication based.33 On the other hand, findings may reflect more established trust linkages with the medical provider. For example, evidence indicates that African Americans prefer general medical services over mental health specialty services for mental health issues.34 Additionally, it could be that guidelines emphasizing pharmacological treatment for children may influence where families are referred or encouraged to seek care for these issues. Future work should examine how African American families with high activation skills negotiate the help-seeking process, from whom they seek information, and where they choose to go for services when they perceive a need for mental health services for their child.

The counseling finding may reflect error in measurement. The counseling measure may be too broadly defined, obscuring differences in use of psychologist and social worker case management services. For example, much of the service use reported in the counseling category may have been case management rather than psychotherapy. Case management services are typically provided to families to help with the burden of navigation rather than as an end goal. Receipt of case management services may be more closely related to service sector or point of entry into services than to parent activation. Limited race concordance may also play a role regarding low preference for social work services.35 Future work should disaggregate provider type to determine if these gaps continue to hold.

Parent activation was not associated with visiting a therapist. For young children, early-intervention services are provided free of charge and in the home, making it easier for families to accommodate service use and thus less reliant on parent activation skills. Older children may receive therapy services at school, also reducing the burden on families to obtain and pay for services.36

Parent activation also was not associated with ever having had a psychiatric hospitalization. Although ideally, parent skill managing their child’s mental health and getting services to meet those needs would be associated with a lower incidence of poor outcomes such as a psychiatric hospitalization, 2 issues may obscure this association here. First, the survey question lumps together all kinds of hospitals: “In the past year, has [child] been admitted for an overnight stay in a hospital or other facility to receive help for emotional or developmental challenges?” A brief stay in a community hospital psychiatric ward may be preferable to a stay in a long-term state psychiatric facility and thus reflect high activation skills. Moreover, even when families are good at getting the services they want, inpatient psychiatric stays might be driven by child need more than parent skills. Ideally, future work should examine how parent activation skills are associated with the child’s lifetime use of psychiatric hospitalization.

African American families with patient activation skills are engaged and initiate child mental health service use. Findings suggest there may be value in investing in the development and implementation of interventions that teach parent activation skills and facilitate their use by practices in order to help reduce disparities in child mental health service use. There has already been considerable investment through the Affordable Care Act in patient-centered medical homes for pediatric populations with cooccurring physical and mental health needs that facilitate shared decision-making in the context of an integrated primary care setting.37 Nonetheless, racial and ethnic disparities in their use remain.38 These persistent disparities, together with the promising findings described here, can help prioritize a research and policy agenda focused on empowering families and training practices to better work with them.39 Interventions have already been developed that successfully teach activation to Latino parents on behalf of their children25 and to African American, Latino, and other adults regarding their own health.20,40 Current work is exploring combined patient- and practice-level interventions that facilitate patient activation and how such skills may improve the quality of the clinical encounter.41 Such work has the potential to determine if parent agency in a supportive practice context extends to expressing preferences about treatment approaches and outcome goals that may lead not only to increased child mental health service use but also to higher satisfaction with care, an important knowledge gap, especially for African American families.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement: The author(s) have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgments: Support for this study was provided by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (P60MD000244). The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of Carol Burt, Sharmila Udyavar, and the families who participated in this research project.

Ethical Statement: All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of North Carolina and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards and were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Authors’ Contributions: Drs Thomas, Ellis, Lightfoot, Perryman, Sikich, and Morrissey participated in the study design. All authors participated in the acquisition and analysis of data. Drs Thomas, Adams, and Davis and Ms Annis participated in the drafting of the final manuscript. All authors participated in the critical review of the manuscript. All authors have given final approval to the manuscript.

References

- 1.Inkelas M, Raghavan R, Larson K, Kuo AA, Ortega AN. Unmet mental health need and access to services for children with special health care needs and their families. Ambul Pediatr 2007 Nov-Dec;7(6):431-8. DOI: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.08.001, PMID:17996836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Popescu I, Xu H, Krivelyova A, Ettner SL. Disparities in receipt of specialty services among children with mental health need enrolled in the CMHI. Psychiatr Serv 2015 Mar 1;66(3):242-8. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300055, PMID:25727111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook BL, Barry CL, Busch SH. Racial/ethnic disparity trends in children's mental health care access and expenditures from 2002 to 2007. Health Serv Res 2013 Feb;48(1):129-49. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01439.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Merikangas K. R., He J.-p., Burstein M., et al. Service utilization for lifetime mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results of the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011 Jan;50(1):32-45. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.10.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cummings JR, Druss BG. Racial/ethnic differences in mental health service use among adolescents with major depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011 Feb;50(2):160-70. DOI: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merritt-Davis OB, Keshavan MS. Pathways to care for African Americans with early psychosis. Psychiatr Serv 2006 Jul;57(7):1043-4. DOI: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.1043, PMID:16816293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cree RA, Bitsko RH, Robinson LR, et al. Health care, family, and community factors associated with mental, behavioral, and developmental disorders and poverty among children aged 2-8 years - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018 Dec;67(50):1377-83. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6750a1, PMID:30571671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shanley DC, Reid GJ, Evans B. How parents seek help for children with mental health problems. Adm Policy Ment Health 2008 May;35(3):135-46. DOI: 10.1007/s10488-006-0107-6, PMID:17211717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zwaanswijk M, Van der Ende J, Verhaak PFM, Bensing JM, Verhulst FC. The different stages and actors involved in the process leading to the use of adolescent mental health services. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry 2007 Oct;12(4):567-82. DOI: 10.1177/1359104507080985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banta JE, James S, Haviland MG, Andersen RM. Race/ethnicity, parent-identified emotional difficulties, and mental health visits among California children. J Behav Health Serv Res 2013 Jan;40(1):5-19. DOI: 10.1007/s11414-012-9298-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maura J, Weisman de Mamani A. Mental health disparities, treatment engagement, and attrition among racial/ethnic minorities with severe mental illness: a review. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2017 Dec;24(3-4):187-210. DOI: 10.1007/s10880-017-9510-2, PMID:28900779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bornheimer LA, Acri MC, Gopalan G, McKay MM. Barriers to service utilization and child mental health treatment attendance among poverty-affected families. Psychiatr Serv 2018 Oct;69(10):1101-4. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700317, PMID:29983111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stock R, Tusler M. Do increases in patient activation result in improved self-management behaviors? Health Serv Res 2007 Aug;42(4):1443-63. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00669.x, PMID:17610432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the patient Activation measure (PAM): Conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 2004 Aug;39(4 Pt 1):1005-26. DOI: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2004.00269.x, PMID:15230939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith SG, Curtis LM, Wardle J, von Wagner C, Wolf MS. Skill set or mind set? Associations between health literacy, patient activation and health. PLoS One 2013 Sep;8(9):e74373. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074373, PMID:24023942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thurston IB, Phares V, Coates EE, Bogart LM. Child problem recognition and help-seeking intentions among black and white parents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2015;44(4):604-15. DOI: 10.1080/15374416.2014.883929, PMID:24635659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Turner EA, Liew J. Children’s adjustment and child mental health service use: The role of parents’ attitudes and personal service use in an upper middle class sample. Community Ment Health J 2010 Jun;46(3):231-40. DOI: 10.1007/s10597-009-9221-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sayal K, Tischler V, Coope C, et al. Parental help-seeking in primary care for child and adolescent mental health concerns: Qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry 2010 Dec;197(6):476-81. DOI: 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.081448, PMID:21119154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Druss BG, Zhao L, von Esenwein SA, et al. The health and recovery peer (HARP) program: a peer-led intervention to improve medical self-management for persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr Res 2010 May;118(1-3):264-70. DOI: 10.1016/j.schres.2010.01.026, PMID:20185272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Alegría M., Polo A., Gao S., et al. Evaluation of a patient activation and empowerment intervention in mental health care. Medical Care 2008 Mar;46(3):247-56. DOI: 10.1097/mlr.0b013e318158af52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruble L, McGrew JH, Wong V, Adams M, Yu Y. A preliminary study of parent activation, parent-teacher alliance, transition planning quality, and IEP and postsecondary goal attainment of students with ASD. J Autism Dev Disord 2019 Aug;49(8):3231-43. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-019-04047-4, PMID:31087213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The behavioral model for vulnerable populations: Application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health Serv Res 2000 Feb;34(6):1273-302.PMID:10654830. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donohue MR, Childs AW, Richards M, Robins DL. Race influences parent report of concerns about symptoms of autism spectrum disorder. Autism 2019 Jan;23(1):100-11. DOI: 10.1177/1362361317722030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green AL, Lambert MC, Hurley KD. Measuring activation in parents of youth with emotional and behavioral disorders. J Behav Health Serv Res 2019 Apr;46(2):306-18. DOI: 10.1007/s11414-018-9627-6, PMID:29956072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomas KC, Stein GL, Williams CS, et al. Fostering activation among Latino parents of children with mental health needs: An RCT. Psychiatr Serv 2017 Oct;68(10):1068-75. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ps.201600366, PMID:28566024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moljord IE, Lara-Cabrera ML, Perestelo-Pérez L, Rivero-Santana A, Eriksen L, Linaker OM. Psychometric properties of the patient activation measure-13 among out-patients waiting for mental health treatment: a validation study in Norway. Patient Educ Couns 2015 Nov;98(11):1410-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.06.009, PMID:26146239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Eneanya ND, Winter M, Cabral H, et al. Health literacy and education as mediators of racial disparities in patient activation within an elderly patient cohort. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2016;27(3):1427-40. DOI: 10.1353/hpu.2016.0133, PMID:27524777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green CA, Perrin NA, Polen MR, Leo MC, Hibbard JH, Tusler M. Development of the patient activation measure for mental health. Adm Policy Ment Health 2010 Jul;37(4):327-33. DOI: 10.1007/s10488-009-0239-6, PMID:19728074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Harvey L, Fowles JB, Xi M, Terry P. When activation changes, what else changes? The relationship between change in patient activation measure (PAM) and employees’ health status and health behaviors. Patient Educ Couns 2012 Aug;88(2):338-43. DOI: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.02.005, PMID:22459636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meng X-L, Rubin DB. Performing likelihood ratio tests with multiply-imputed data sets. Biometrika 1992;79(1):103–11. DOI: 10.1093/biomet/79.1.103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flores G, Lin H, Walker C, et al. A cross-sectional study of parental awareness of and reasons for lack of health insurance among minority children, and the impact on health, access to care, and unmet needs. Int J Equity Health 2016 Mar;15:44. DOI: 10.1186/s12939-016-0331-y, PMID:27000795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hibbard JH, Cunningham PJ. How engaged are consumers in their health and health care, and why does it matter? Res Brief 2008 Oct;8(8):1-9.PMID:18946947. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nadeem E, Lange JM, Miranda J. Mental health care preferences among low-income and minority women. Arch Womens Ment Health 2008 Jun;11(2):93-102. DOI: 10.1007/s00737-008-0002-0, PMID:18463940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neighbors HW, Caldwell C, Williams DR, et al. Race, ethnicity, and the use of services for mental disorders: Results from the National Survey of American Life. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007 Apr;64(4):485-94. DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.4.485, PMID:17404125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Straussner SLA, Senreich E, Steen JT. Wounded healers: a multistate study of licensed social workers' behavioral health problems. Soc Work 2018 Apr;63(2):125-33. DOI: 10.1093/sw/swy012, PMID:29425335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas KC, Ellis AR, McLaurin C, Daniels J, Morrissey JP. Access to care for autism-related services. J Autism Dev Disord 2007 Nov;37(10):1902-12. DOI: 10.1007/s10803-006-0323-7, PMID:17372817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shortell SM, Poon BY, Ramsay PP, et al. A multilevel analysis of patient engagement and patient-reported outcomes in primary care practices of accountable care organizations. J Gen Intern Med 2017 Jun;32(6):640-7. DOI: 10.1007/s11606-016-3980-z, PMID:28160187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pérez Jolles M, Thomas KC. Disparities in self-reported access to patient-centered medical home care for children with special health care needs. Medical Care 2018 Oct;56(10):840-6. DOI: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tai-Seale M, Sullivan G, Cheney A, Thomas K, Frosch D. The language of engagement: “Aha!” moments from engaging patients and community stakeholders in two PCORI pilot projects of the patient-centered outcomes research Institute. Perm J 2016 Spring;20:89-92. DOI: 10.7812/TPP/15-123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hibbard JH, Greene J, Tusler, M. Improving the outcomes of disease management by tailoring care to the patient's level of activation. Am J Manag Care 2009 Jun;15(6):353-60.PMID:19514801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chew S., Brewster L., Tarrant C., Martin G., Armstrong N.. Fidelity or flexibility: An ethnographic study of the implementation and use of the Patient Activation Measure. Patient Education and Counseling 2018 May;101(5):932-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]