Abstract

Descriptions of the small intestinal microbiota are deficient and conflicting. We aimed to get a reliable description of the jejunal bacterial microbiota by investigating samples from two separate jejunal segments collected from the luminal mucosa during surgery. Sixty patients with morbid obesity selected for elective gastric bypass surgery were included in this survey. Samples collected by rubbing a swab against the mucosa of proximal and mid jejunal segments were characterized both quantitatively and qualitatively using a combination of microbial culture, a universal quantitative PCR and 16S deep sequencing. Within the inherent limitations of partial 16S sequencing, bacteria were assigned to the species level. By microbial culture, 53 patients (88.3%) had an estimated bacterial density of < 1600 cfu/ml in both segments whereof 31 (51.7%) were culture negative in both segments corresponding to a bacterial density below 160 cfu/ml. By quantitative PCR, 46 patients (76.7%) had less than 104 bacterial genomes/ml in both segments. The most abundant and frequently identified species by 16S deep sequencing were associated with the oral cavity, most often from the Streptococcus mitis group, the Streptococcus sanguinis group, Granulicatella adiacens/para-adiacens, the Schaalia odontolytica complex and Gemella haemolysans/taiwanensis. In general, few bacterial species were identified per sample and there was a low consistency both between the two investigated segments in each patient and between patients. The jejunal mucosa of fasting obese patients contains relatively few microorganisms and a core microbiota could not be established. The identified microbes are likely representatives of a transient microbiota and there is a high degree of overlap between the most frequently identified species in the jejunum and the recently described ileum core microbiota.

Subject terms: Microbiology, Molecular biology, Anatomy, Gastroenterology, Medical research, Molecular medicine

Introduction

The longstanding debate as to whether antibacterial mechanisms of the intestinal epithelium along with peristalsis prevent the formation of a resident jejunal microbiota, is still not resolved1–4. Descriptions of the jejunal microbiota remains vague and there is little consistency both among microbial quantifications and described microbial compositions. Contemporary textbooks5 and reviews6–12 report bacterial concentrations of 104 to 107 cfu/ml, dominated by lactobacilli, streptococci, enterococci and Veillonella spp. Enterobacteriales are also considered to be prominent participants8–10,13,14.

Deep sequencing approaches13–21 have failed to define a consistent core microbiota. Streptococcus, Prevotella, Veillonella and Fusobacterium are frequently detected genera along with a range of Proteobacteria including Enterobacteriales, Haemophilus spp. and Neisseria spp. These studies are typically based on indirect sample collection procedures like endoscopies13,14,16,17,19,20,22, nasoileal catheters18,23, capsules15 or from autopsies21. Despite the use of indirect sampling, the possibility for sample contamination from more abundantly colonized parts of the gastrointestinal tract has rarely been addressed.

We have identified four older studies on samples collected directly from the jejunal lumen during surgery3,24–26. These studies, published between 1953 and 1979 were based on culture-dependent techniques. They consistently report a high proportion of jejunal samples to be sterile, 71%, 20%, 63% and 69% respectively. The sporadic species detected, typically gram-positive facultative bacteria like viridans streptococci, were related to the oral cavity and generally considered transient microorganisms. Strict anaerobes, Enterobacteriales and enterococci were rarely detected.

In an attempt to provide a comprehensive and methodically sound description of the jejunal microbiota, we collected samples from two separate jejunal segments in a cohort of 60 patients during scheduled gastric bypass surgery. The samples were characterized qualitatively and quantitatively using a combination of microbial culture, a universal quantitative PCR and 16S deep sequencing. The study population was a selected group of patients with morbid obesity otherwise considered intestinally healthy. Although some components of their microbiota might differ from that of a normal weight population, we believe the overall findings will be representative and can contribute to our understanding of the normal human jejunal microbiota.

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 60 patients were included with a median age of 45 years and a preponderance of females (70%). All patients were intestinally healthy, but due to morbid obesity and other comorbid conditions most are classified with an ASA risk score 3 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Population characteristics | Number of patients (n = 60) | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Age years, median (range) | 45 (19–65) | |

| BMI kg/m2, median (range) | 41 (34–57) | |

| Gender, male | 18 | 30 |

| Gender, female | 42 | 70 |

| ASA score 1 | 0 | 0 |

| ASA score 2 | 3 | 5 |

| ASA score 3 | 56 | 93 |

| ASA score 4 | 1 | 2 |

| Current smoker | 0 | 0 |

| Systolic BP, mean (95%CI) | 136 (132–140) | |

| Diastolic BP, mean (95%CI) | 85 (83–87) | |

| Comorbidities | 49 | 82 |

| Diabetes, any type | 10 | 17 |

| Peroral antidiabetics | 7 | 12 |

| Insulin dependant | 1 | 2 |

| Hypertension | 21 | 35 |

| Dyslipidemia | 12 | 20 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) | 17 | 28 |

| OSA with CPAP | 15 | 25 |

| Previous cholecystectomy | 10 | 17 |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 14 | 23 |

| Median (range) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Operative time, min | 56 (31–101) | |

| Postoperative stay, days | 1 (1–7) |

BMI Body Mass Index, ASA American Society of Anesthesiologists, BP blood pressure, CPAP continuous positive airway pressure.

Findings by microbial culture

Bacterial concentrations as estimated by microbial culture are presented in Table 2. No growth in either segment was observed for 31 patients (51.7%) and only three patients (5%) had growth that exceeded the upper limit of quantification (> 1.6 × 104). Cultivated bacteria are listed in Supplementary Table S1. When combining results from both jejunal segments, the most frequent bacteria at the patient level were: Streptococcus salivarius/vestibularis (25% of patients), S. parasanguinis (16%), S. mitis/oralis (12%), Rothia mucilaginosa (10%), Actinomyces odontolyticus (8%), Haemophilus parainfluenzae (8%), Neisseria flavescens/subflava (5%) and Neisseria parahaemolyticus (5%). Enterobacteriales were only detected in one patient (a Klebsiella pneumoniae). Fungi, a Candida albicans, grew in only one sample collected from a mid-segment.

Table 2.

Microbiological densities estimated in jejunum by aerobic and anaerobic culture.

| Growth | cfu/ml | Proximal jejunum (n) | Mid jejunum (n) | Patient level (n) (Both segments combined)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No growth | < 160 | 34 | 43 | 51.7% (31) | 88.3% |

| Single colony/broth only | 160– < 1600 | 21 | 13 | 36.7% (22) | |

| Sparse growth | 1600– < 8000 | 3 | 0 | 3.3% (2) | 11.6% |

| Moderate growth | 0.8–1.6 × 104 | 1 | 2 | 3.3% (2) | |

| Abundant growth | > 1.6 × 104 | 1 | 2 | 5% (3) | |

| In total | 60 | 60 | 100% | 100% |

*Counted by the most bacteria rich segment.

Deep sequencing technical results

The median number of reads per sample was 445,263 (range 264,689 to 911,244). After removal of chimera, small OTUs (< 50) and contaminants, the median number of remaining reads was 19,568 (range 2700 to 282,249). The median percentage of retained reads was 9.9% (range 0.5% to 97.4%) with only 16 of 120 samples having more than half of the reads left.

Microbial findings by 16S deep sequencing

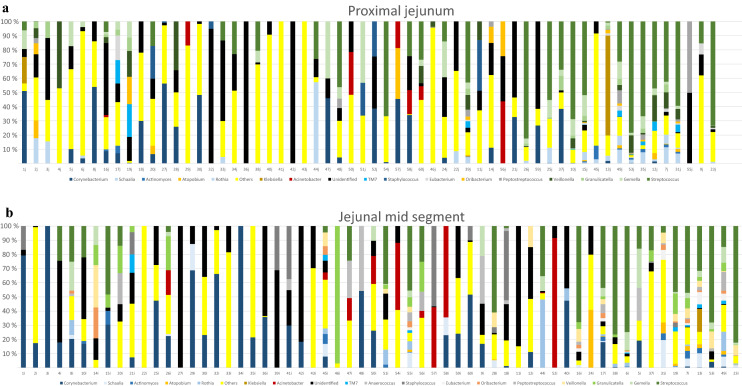

In total, after filtering of possible contaminants, we identified 218 different species (Supplementary Table S2). A per sample description at the genus level is provided in Fig. 1 and at the phylum level in Supplementary Fig. S1. Actinobacteria, especially Corynebacterium spp., seems to be more abundant in samples with low bacterial loads whereas the presence of Firmicutes, in particular Streptococcus spp., Gemella spp. and Granulicatella spp. increases in samples with higher bacterial loads.

Figure 1.

Relative distribution of most abundant genera in (a) proximal part of jejunum and (b) jejunal mid-segment. All 60 patients included. Samples are sorted by increasing bacterial concentration. Samples with concentration below the level of quantification (Ct-value ≥ 34.17) are sorted by name on the left side (35 proximal samples 1j-60j and 38 mid-segment samples, 1i-60i).

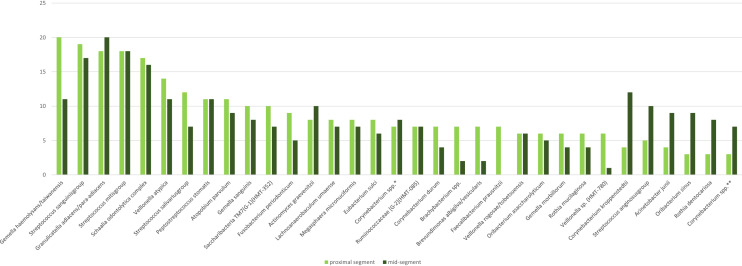

An overall species-level comparison of results from the upper and middle part of jejunum revealed no noticeable differences (Fig. 2). In addition, most species were found at low concentrations close to the limit of detection and consequently prone to random detection. Therefore, for the remaining part of this manuscript, results from the two segments were merged and reported per patient. No species was detected in more than 50% of the population and only six species/groups of species were found in more than 30% of participants: Enterobacteriales were only exceptionally detected; Escherichia coli in 3 patients (5%), Serratia grimesii/proteamaculans/liquefaciens in 3 patients (5%) and Klebsiella pneumonia complex in 2 patients (3%).

Figure 2.

Comparison of most frequent species in upper and middle jejunum. (y axis number of patients). Based on all 60 patients.

Quantification by PCR

Bacterial genome concentrations as determined by the quantitative 16S rRNA PCR are presented in Table 3. The median density was found to be below our limit of genomic quantification i.e. < 2.9 × 103 bacterial genomes per ml.

Table 3.

Microbial densities estimated by quantitative 16S rRNA PCR.

| Genome copies/ml | Proximal jejunum (n) | Mid jejunum (n) | Patient level (n) (Both segments combined)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| 105– < 106 | 5% (3) | 5% (3) | 5% (3) |

| 104– < 105 | 16.7% (10) | 6.7% (4) | 18.3% (11) |

| 2.9 × 103– < 104 | 20% (12) | 25% (15) | 36.7% (22) |

| < 2.9 × 103 | 58.3% (35) | 63.3% (38) | 40% (24) |

*Counted by the most microbial genome-rich segment.

Intra-patient concentration differences between proximal and mid-jejunal samples were generally small, and there was no overall tendency towards a higher bacterial load in neither of the segments. In four patients (9, 49, 53 and 55) we observed a more than tenfold concentration difference between the two samples, two of them with the highest load in the proximal sample and two with the highest load in the more distal sample.

Results from microbial culture and 16S deep sequencing compared

A comparison of findings by microbial culture versus by deep sequencing is provided in Supplementary Table S3. As expected, deep sequencing identified far more species than culture. Out of 120 samples, only 43 were culture positive. Still, culture made 22 identifications not reproduced by sequencing. These identifications were most often from the species Haemophilus parainfluenzae, Actinomyces odontolyticus, Micrococcus luteus, Streptococcus mitis group and Streptococcus salivarius/vestibularis.

Comparison of sequencing results from this study with previously reported results from the ileum

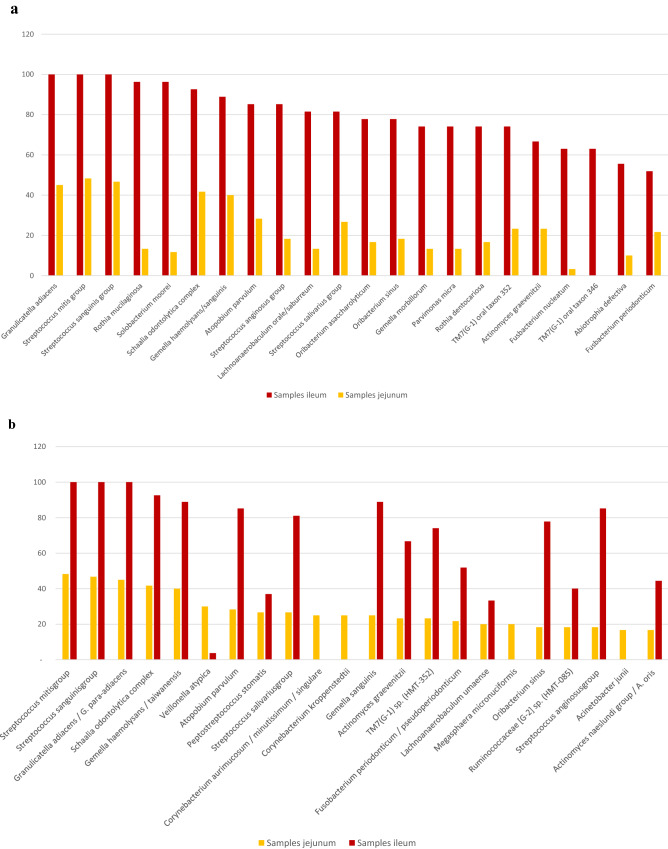

In a recent study on peroperative ileal samples from patients undergoing radical cystectomy27 we defined an ileum core microbiota consisting of 22 species, each present in more than half of the patients. In Fig. 3a, we show that except from the provisional species TM7(G-1) oral taxon 346, all 22 ileum core microbiota species were also detected in the jejunal samples although much more sporadically. In Fig. 3b we compare the most frequent species in jejunum with their corresponding frequencies in ileum. Except from Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii, C. aurimucosum/minutissimum/singulare and Acinetobacter junii, all these were also part of the ileum core microbiota. Again, most of them were much more frequently detected in ileum. Granulicatella adiacens, Streptococcus mitis group and Streptococcus sanguinis group were the three most frequent identifications in both ileum and jejunum.

Figure 3.

(a) Previously reported ileum core microbiota (based on 27 patients) sorted by frequency (%) compared to observed frequency in jejunum (upper and middle segment combined for all 60 patients) and (b). Most frequently detected species in jejunum (upper and middle segment combined) sorted by frequency (%) compared to previously reported frequency in ileum. Based on all 60 patients.

Discussion

Our results indicate that the jejunum is more scarcely populated by bacteria than specified by contemporary reviews and textbooks. Using a combination of cultivation and deep sequencing with a limit of detection in the range 102 to 103 cfu/genomes per milliliter of sample material, we were unable to recover a resident core microbiota in the proximal and middle parts of the human jejunum.

Keystone species are thought to be important for shaping the organization and diversity of an ecological community, and a common core microbiota has been variably defined as microbial taxa present in between 30 and 95% of a population28. In our material, only five identifications were made in more than 30% of the patients: Streptococcus mitis group (48%), Streptococcus sanguinis group (47%), Granulicatella adiacens/para-adiacens (45%), Schaalia odontolytica complex (42%) and Gemella haemolysans/taiwanensis (40%). All of these are groups of species not possible to differentiate by 16S rRNA sequencing, and therefore most likely, as previously demonstrated in ileum27, represent more than one species each. Further, microbial resemblance between samples was low both between the upper and middle segments in each patient and between patients.

We detected a wide range of Corynebacterium species in this study, and they also dominated in some of the weak positive samples. Among these, Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii, Corynebacterium aurimucosum and Corynebacterium durum were detected rather frequently (18–25% of patients). Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii was first isolated from a sputum sample, C. durum from respiratory samples and C. aurimucosum from human clinical samples. Also the other Corynebacteria deemed relevant in this study are associated with the human microbiota and/or human infections with the exception of C. vitaeruminis, a vitamin-B producing microbe isolated from the rumen of cows. It could be argued that C. vitaeruminis should be removed as biologically unexpected, but is was detected in seven patient samples.

The jejunal samples also generally revealed low bacterial densities, both by cultivation and by 16S rRNA quantification. The median density was < 1600 cfu/ml or < 2.9 × 103 bacterial genomes/ml. Only 23.3% of the samples had an estimated bacterial concentration above 104 genome copies per ml. In contrast to cultivation, 16S deep sequencing was positive in all samples, although sometimes only with a single species.

Despite being performed on two different patient populations, the overall spectrum of bacteria identified from the jejunal samples in the present study, bears a striking resemblance to the ileal core microbiota as defined by our recent studies on surgically collected ileal samples (Fig. 3a,b)27,29. 16S Ct-values indicate that the bacterial concentration in ileum is at least 100 fold higher than in jejunum. The overall impression is that bacterial cells are capable of multiplying and forming a stable microbiota with a definable core microbiota only more distally in the ileum. Consequently, our results revitalize discussions as to whether the human jejunum harbors only transient microbes and no resident microbiota.

The higher bacterial concentrations in jejunum reported by previous 16S deep sequencing studies might reflect the use of indirect sample collection methods by endoscopies, nasoileal catheters and capsules with an inherent risk of contamination from the more abundantly colonized upper gastrointestinal tract. The human oral cavity has a rich and dense microbiota30 and saliva is estimated to contain 109 cfu/ml31. Provided a bacterial density of maximum 103–104 in jejunum, this represents a gradient of at least 1:105 suggesting that both endoscopies and nasoileal tubes introduce a considerable risk for contamination32. This can also affect microbial composition. In a study using endoscopy to collect samples33 they found Bacteroides, Prevotella and Helicobacter to be among the most frequent and dominant genera. Although we also found multiple species from these genera in our samples they were mainly represented as only minor constituents. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to combine 16S deep sequencing with samples collected directly from the jejunal mucosa during surgery. Our results are more in line with older culture-based studies on samples collected by needle aspiration from the jejunum of intestinally healthy individuals during abdominal surgery.

This investigation has some notable limitations. There might be differences in the microbiota of obese patients versus a normal weight population. Obesity has earlier been associated with increased risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth34 in which case the bacterial load in jejunum from non-obese might be even lower than observed in this study. On the other hand, our patients were subjected to a 3 week low calorie diet with an unknown impact on the jejunal microbiota. Further, the patients were in a fasting state. Earlier publications have found the small intestine to harbor more bacteria after meals35 and that environmental and food-related bacteria then make up a considerable part of the findings36. Therefore, as the goal of this study was to describe a normal physiological core microbiota, data from a fasting state might be preferable.

The antibiotic prophylaxis in this study, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX), is active against both gram negative and gram positive bacteria, but less effective against anaerobic bacteria. The antibiotic prophylaxis could interfere with results from cultivation. However, in 1978, Corrodi et al.25 collected jejunal content by sterile needle aspiration in eight obese patients during a gastric bypass procedure without antibiotic prophylaxis. They found 63% of samples to be cultivable sterile, even more than in our material (51.7%). The 16S deep sequencing is less likely to be noticeably affected by the antibiotics given only 2 h before surgery. Finally, although the surgeons were instructed to rub the sample collection swab firmly against the intestinal mucosa it could be that some mucosa-associated bacteria were not effectively sampled.

The strengths of this study are a high number of subjects compared to previous studies, the investigation of two separate jejunal segments from each patient and the use of surgically collected mucosal samples free of contamination from other parts of the gastrointestinal tract. Future studies on the small intestine should attempt to reduce the sampling biases by also using surgically collected samples. Unfortunately, it is a significant challenge to obtain these samples from patients not a priori in need of surgery on the small intestines. Sterile needle sampling during other types of elective abdominal surgery as used in the older culture-based studies, could represent an alternative. Although ethical and patient safety aspects need to be re-evaluated by contemporary experts in both ethics and clinical medicine, this might represent an acceptable approach in order to provide reliable data from the understudied segment of the gastrointestinal tract most essential for nutrient uptake and probably also host-microbe interactions.

Conclusion

Proper sample collection methods is crucial for studies on the small intestine. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study of the jejunal bacterial microbiota collected surgically on intestinally healthy patients. Our data fail to demonstrate a jejunal resident core microbiota. Most species identified by both cultivation and deep sequencing appear only sporadically with high intra-individual differences and also considerable differences between the upper and mid segments in each patients.

Patients and methods

Population

Sixty patients scheduled for gastric bypass surgery at Vestfold Hospital Trust (SiV HF) were consecutively enrolled from December 2017 to September 2018. The study was approved by The Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics in the South-Eastern Norway Regional Health Region (2017/106 REK sør-øst D). All methods were performed in accordance with this approval and in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. There were no predefined exclusion criteria.

All patients were prescribed a preoperative low-calorie diet (< 1000 kcal/day) 3 weeks before surgery, and recommended a preoperative weight loss of approximately 5%. Patients underwent fasting for solid foods a minimum of 6 h before surgery, and fluids were withheld 2 h before the procedure. Standard per oral preoperative antibiotic prophylaxis was given in the form of TMP/SMX (160 mg/800 mg) 2 h prior to surgery. All patients were examined preoperatively by a surgeon and there were no evidence of intestinal disease.

Surgical sample collection

A standard laparoscopic gastric bypass was performed in all patients with an antegastric antecolic Roux-en-Y configuration using linear staplers. Four microbiological samples were collected from the openings of the small bowel prior to forming the two intracorporal anastomoses. Two samples were taken 60 cm from the ligament of Treitz prior the gastrojejunostomy, and two 120 cm further along the jejunum (180 cm from the ligament of Treitz) before creating the jejunojejunostomy. The swab from a standard Transwab medium (MWE, Medical Wire, UK), was introduced through a clean laparoscopy trocar and rubbed against the luminal wall to absorb the jejunum mucosal secretion. One sample from each site was cultivated within 2 h. The other pair of samples were frozen at − 70° for later DNA extraction.

Sample cultivation and identification of bacterial colonies

50 μl of vortexed content from the Transwab medium was distributed on blood, chocolate, MacConckey and Sabouraud Dextrose agars respectively for incubation in 5% CO2 enriched air at 37 °C for 5 days. The same amount was spread on blood and Menadione agar plates and inoculated to a Thio broth and incubated anaerobically for 5 days. Growth was evaluated by experienced lab technicians and all colony variants were submitted for matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) identification using the Biotyper version 4.1.70.0–4.1.90.0 software. Scores above 2000 with consistent naming (category A) were accepted for identification at the species level. Scores between 1700 and 1999 were accepted for a genus level identification. For each species, colonies were quantified on the plate with the most abundant growth.

Quantification by microbial culture

The swab in the Transwab kit absorbs 150 μl of sample material. The Transwab tube contains 1050 μl of solution, giving a 1:8 dilution of the sample. Provided 50 μl are spread on an agar plate, one colony (or growth in broth exclusively) corresponds to 1 × 8 × 20 = 160 cfu/ml in the original sample which was our lower limit of detection. Quantification by bacterial growth was performed according to Table 4.

Table 4.

Quantification by microbial culture.

| Growth | Colonies on plate | Cfu/ ml | Growth |

|---|---|---|---|

| No growth (lower limit of detection) | 0 | < 160 |

Non-substantial < 1600 cfu/ml |

| Single colonies/ broth only | 1–9 | 160– < 1600 | |

| Sparsely growth | 10–49 | 1600– < 8000 |

Substantial ≥ 1600 cfu/ml |

| Moderate growth | 50–100 | 0.8–1.6 × 104 | |

| Abundant growth (upper limit of detection) | > 100 | > 1.6 × 104 |

Quantification by real-time PCR

The quantitative 16S rRNA gene-PCR was based on the dual priming oligonucleotide (DPO) principle to avoid interference from human DNA37. The 5-end of the primers were modified according to Dyrhovden et. al.38 (16S_DPO_Short-F: 5’-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAIIIIIAACGCT-3’ and 16S_DPO_Short-R: 5’-CGGCTGCTGGCAIIIAITTRGC-3’). The universal anti-sense probe was designed for this study and placed in a highly conserved region of the 16S rRNA gene (Escherichia coli 16S rRNA position 360 to 341)39 (16S-Pb: FAM-CCYACTGCTGCCTCCCGTAG-BBQ). The PCR reaction mixture consisted of 12.5 µL Premix Ex Taq Mastermix (TaKaRa Bio, Kusatsu, Japan), 1.5 µL of each primer (from a 10 µM solution), 0.5 µL probe (from a 10 µM solution), 7 µL PCR grade water and 2 µL of template giving a total reaction volume of 25 µL. The PCR was run on a QuantStudio5 real-time PCR instrument (ThermoFisher) using a two-step thermal profile: (1) Enzyme activation at 95 °C for 30 s (2) melting at 95 °C for 10 s (3) annealing/extension at 60 °C for 20 s. Step (2) and (3) were repeated 40 times.

Streptococcus pneumoniae was selected as a quantitative standard due to its similarity to the other bacteria in the mitis group constituting an important part of the small intestinal microbiota. It also possesses four copies of the 16S rRNA gene which is close the estimated average number of 16S copies in bacterial genomes40,41. We extracted total nucleic acids from a heavy suspension of Streptococcus pneumoniae ATCC 49619 in PCR grade water using a MagNaPure Compact automated extractor (Roche, Mannheim, Germany). The DNA concentration in two individual samplings of the eluate was measured on a Qubit Fluorometer (Qiagen). Based on these measurements (37.3 and 39.3 ng/µl; average 38.3 ng/µl) and a genome size of 2,096,423 basepairs (ATCC 49619/GenBank accession GCA_003966485.1) we calculated the concentration of S. pneumoniae in our eluate to be 1.69 × 107 genomes/µl. From this eluate we made a ten-fold dilution series from 1.69 × 107 to 1.69 × 10–2. Each of the nine dilution steps was run in triplet in the quantitative real-time 16S PCR. The PCR was found to be linear down to dilution step 7, i.e. 1.69 × 100 genomes/µl with an average Ct-value of 34.17 (Supplementary Fig. S2). Provided 2 µl of template and 4 copies of the 16S rRNA gene per genome this corresponds to approximately 14 target copies per PCR reaction. Taking into account the 1:833 dilution of our clinical samples during sample collection and DNA extraction, it further corresponds to 2816 bacterial genomes/ml of jejunal content which was therefore our lower limit of molecular quantification.

The S. pneumoniae 1.69 × 106 dilution step was included as a standard in the subsequent analysis of the jejunal samples. The standard was run in triplet and the average Ct-value used to adjust the quantitative estimates for the jejunal samples. The observed inter-run variation for the standard was small (average Ct-values 31.25, 31.11 and 30.93 respectively). The estimated genome copy number per PCR reaction for the standard was 2 × 1.69 × 101 i.e. 33.8 genomes which corresponds to ~ 2.9 × 103 bacterial genomes/ml in a jejunal sample.

Sample preparation and DNA extraction for 16S deep sequencing

Two-hundred μl of nuclease-free water (Ambion, Thermo Fisher Scienfic) and 450 μl sample solution from the Transwab media (MWE, Medical Wire, England) were transferred to Matrix E glasses (mpbio, MP Biomedicals, United States) and run on a FastPrep 24 instrument for 2 × 45 s. After bead-beating, the samples were centrifuged for 2 min at 13,000 rpm. Thereafter 200 μl of supernatant from each sample was used for DNA extraction and purification on a QIAsymphony automated extractor using the “DSP DNA Mini kit” (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Negative controls

Unused Transwab sample collection tubes from the two batches used in this study were included as negative controls. In addition, one Transwab tube from each batch was spiked with 1 μl of a 0.5 McFarland suspension of Legionella pneumophila (corresponding to 1.5 × 105 bacterial cells) and included as weak positive extraction controls. Each extraction set-up therefore included two negative and two weak positive controls. Five extraction set-ups were necessary to process all samples, resulting in a total of ten negative and ten weak positive controls. Air-swabs were not included as negative controls in this study.

16S deep sequencing

Deep sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene was based on the Illumina V3-V4 16S metagenomics protocol with some modifications as described previously38: PCR amplification of the V3-V4 region was done as a real time PCR reaction on a LightCycler 480 PCR instrument (Roche) using the TBGreen Premix Ex Taq (TaKaRa, Shiga, Japan) mastermix instead of the KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix. The PCR mixture consisted of 12.5 μl mastermix, 8.5 μl PCR-grade water, 1 μl of each primer (from a 10 μM solution, giving a final concentration of 0.4 μM in the PCR) and 2 μl template. After an initial polymerase activation step of 30 s at 95 °C the thermal profile included 45 cycles of 20 s at 95 °C (melting), 30 s at 60 °C (annealing), and 30 s at 72 °C (extension). The PCR products from the real time TBGreen reaction were used directly in downstream steps. The rest of the procedure was performed according to the Illumina protocol without further modifications. Sequencing was done on a MiSeq instrument (Illumina, San Diego, CA) using the Miseq reagent kit V3 (2 × 300 bp reads).

Sequence data analysis

After sequencing, FASTQ-files were analyzed using the RipSeq NGS software (Pathogenomix, Santa Cruz, CA). After merging of R1 and R2 files, sequences shorter than 300 base pairs were removed before de novo clustering into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) using a 99% similarity threshold. OTUs with fewer than 50 sequences were rejected. Remaining OTUs were annotated using a blast search against the Pathogenomix Prime database. For an unambiguous species-level identification, we required ≥ 99.0% homology with a high-quality reference sequence combined with a minimum distance of > 0.8% to the next alternative species. For hits above 99% but with less than 0.8% distance to the next alternative species the alternative species is presented in parenthesis. Slashed results were used for OTUs that obtained identical scores against more than one species. Homologies between 97 and 99% qualified for genus-level identification.

Elimination of chimera and contaminant background DNA

Chimeric OTUs were filtered from all samples using the RipSeq NGS chimera check. Sequencing results from all twenty negative/weak positive controls were pooled. The most abundant contaminant species (Cutibacterium acnes, Ralstonia pickettii and Staphylococcus capitis/caprae/epidermidis, Aquabacterium and Hydrotalea flava) were highly consistent across all controls and used to define sample-specific cutoffs for valid identifications42. All species/sequence-types detected in any of the negative controls were removed from the sample sequencing results unless when they appeared in higher concentrations than all the most abundant contaminants listed above. All cultured bacteria were accepted as valid findings. Some of the cultured species were also represented in the negative sequencing controls, and therefore could not be included based on the sequencing data. This illustrates the value of combining two independent detection principles. A complete list of bacteria identified in our negative/weak positive sequencing controls is provided in Supplementary Table S4. Finally, species appearing only once among all the 120 samples, and species considered clearly biologically unexpected were removed. A complete list of rejected identifications is presented in Supplementary Table S5.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

H.C.V., T.S. and M.S. designed the study. E.U. and Ø.K. structured the manuscript together with H.V. M.S. collected samples and obtained clinical characteristics from journals. Ø.K., I.L.A. and R.M.N. did the main laboratory work together with H.C.V. H.C.V. did the description analyzes with support from Ø.K. All authors contributed to interpretation of the data and read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Department of Microbiology and Department of Research and Innovation, Vestfold Hospital Trust, and Department of Microbiology, Haukeland University Hospital. The work was also supported by grants from Norwegian Society for Thoracic Laparoscopic Surgery, Norwegian Society for Gastrointestinal Surgery and from Usage of Antimicrobial Agents and Occurrence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Norway (NORM).

Data availability

The data for this study have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) at EMBL-EBI under accession number PRJEB46597 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/PRJEB46597).

Competing interests

ØK has contributed to the development of the RipSeq NGS software and is a shareholder in Pathogenomix. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-05723-9.

References

- 1.Savage DC. Microbial ecology of the gastrointestinal tract. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1977;31:107–133. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.31.100177.000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorbach SL, Plaut AG, Nahas L, Weinstein L, Spanknebel G, Levitan R. Studies of intestinal microflora. II. Microorganisms of the small intestine and their relations to oral and fecal flora. Gastroenterology. 1967;53(6):856–867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bornside GH, Welsh JS, Cohn I. Bacterial flora of the human small intestine. JAMA. 1966;196(13):1125–1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donaldson RM., Jr Normal bacterial populations of the intestine and their relation to intestinal function. N. Engl. J. Med. 1964;270(20):1050–1056. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196405142702007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Versalovic J, Highlander SK, Petrosino JF, et al. The human microbiome. In: Jorgensen JH, Pfaller MA, Carroll KC, Funke G, Landry ML, Richter SS, et al., editors. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 11. ASM Press; 2015. pp. 226–237. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Booijink CC, Zoetendal EG, Kleerebezem M, de Vos WM. Microbial communities in the human small intestine: Coupling diversity to metagenomics. Future Microbiol. 2007;2(3):285–295. doi: 10.2217/17460913.2.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cotter PD. Small intestine and microbiota. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2011;27(2):99–105. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328341dc67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donaldson GP, Lee SM, Mazmanian SK. Gut biogeography of the bacterial microbiota. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2016;14(1):20–32. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martinez-Guryn K, Leone V, Chang EB. Regional diversity of the gastrointestinal microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;26(3):314–324. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2019.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lema I, Araujo JR, Rolhion N, Demignot S. Jejunum: The understudied meeting place of dietary lipids and the microbiota. Biochimie. 2020;178:124–136. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2020.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aron-Wisnewsky J, Dore J, Clement K. The importance of the gut microbiota after bariatric surgery. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;9(10):590–598. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2012.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piewngam P, De Mets F, Otto M. Intestinal microbiota: The hidden gems in the gut? Asian Pac. J. Allergy Immunol. 2020;38:215–224. doi: 10.12932/AP-020720-0897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leite GG, Weitsman S, Parodi G, Celly S, Sedighi R, Sanchez M, et al. Mapping the segmental microbiomes in the human small bowel in comparison with stool: A REIMAGINE study. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2020;65:2595–2604. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06173-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sundin OH, Mendoza-Ladd A, Zeng M, Diaz-Arevalo D, Morales E, Fagan BM, et al. The human jejunum has an endogenous microbiota that differs from those in the oral cavity and colon. BMC Microbiol. 2017;17(1):160. doi: 10.1186/s12866-017-1059-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dlugosz A, Winckler B, Lundin E, Zakikhany K, Sandstrom G, Ye W, et al. No difference in small bowel microbiota between patients with irritable bowel syndrome and healthy controls. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:8508. doi: 10.1038/srep08508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung C-S, Chang P-F, Liao C-H, Lee T-H, Chen Y, Lee Y-C, et al. Differences of microbiota in small bowel and faeces between irritable bowel syndrome patients and healthy subjects. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2016;51(4):410–419. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2015.1116107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vuik F, Dicksved J, Lam S, Fuhler G, van der Laan L, van de Winkel A, et al. Composition of the mucosa-associated microbiota along the entire gastrointestinal tract of human individuals. United Eur. Gastroenterol. J. 2019;7(7):897–907. doi: 10.1177/2050640619852255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seekatz AM, Schnizlein MK, Koenigsknecht MJ, Baker JR, Hasler WL, Bleske BE, et al. Spatial and temporal analysis of the stomach and small-intestinal microbiota in fasted healthy humans. mSphere. 2019;4(2):e00126. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00126-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shin AS, Gao X, Bohm M, Lin H, Gupta A, Nelson DE, et al. Characterization of proximal small intestinal microbiota in patients with suspected small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2019;10(8):e00073. doi: 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kashiwagi S, Naito Y, Inoue R, Takagi T, Nakano T, Inada Y, et al. Mucosa-associated microbiota in the gastrointestinal tract of healthy Japanese subjects. Digestion. 2020;101(2):107–120. doi: 10.1159/000496102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayashi H, Takahashi R, Nishi T, Sakamoto M, Benno Y. Molecular analysis of jejunal, ileal, caecal and recto-sigmoidal human colonic microbiota using 16S rRNA gene libraries and terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism. J. Med. Microbiol. 2005;54(Pt 11):1093–1101. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.45935-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mailhe M, Ricaboni D, Vitton V, Gonzalez JM, Bachar D, Dubourg G, et al. Repertoire of the gut microbiota from stomach to colon using culturomics and next-generation sequencing. BMC Microbiol. 2018;18(1):157. doi: 10.1186/s12866-018-1304-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 23.Angelakis E, Armougom F, Carriere F, Bachar D, Laugier R, Lagier JC, et al. A metagenomic investigation of the duodenal microbiota reveals links with obesity. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(9):e0137784. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0137784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cregan J, Hayward NJ. The bacterial content of the healthy human small intestine. BMJ. 1953;1(4824):1356–1359. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4824.1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Corrodi P, Wideman PA, Sutter VL, Drenick EJ, Passaro E, Jr, Finegold SM. Bacterial flora of the small bowel before and after bypass procedure for morbid obesity. J. Infect. Dis. 1978;137(1):1–6. doi: 10.1093/infdis/137.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thadepalli H, Lou MA, Bach VT, Matsui TK, Mandal AK. Microflora of the human small intestine. Am. J. Surg. 1979;138(6):845–850. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(79)90309-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villmones HC, Haug ES, Ulvestad E, Grude N, Stenstad T, Halland A, et al. Species level description of the human ileal bacterial microbiota. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):4736. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-23198-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Risely A. Applying the core microbiome to understand host–microbe systems. J. Anim. Ecol. 2020;89(7):1549–1558. doi: 10.1111/1365-2656.13229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Villmones HC, Halland A, Stenstad T, Ulvestad E, Weedon-Fekjær H, Kommedal Ø. The cultivable microbiota of the human distal ileum. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020;27:912e.7–912e.13. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2020.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dewhirst FE, Chen T, Izard J, Paster BJ, Tanner AC, Yu WH, et al. The human oral microbiome. J. Bacteriol. 2010;192(19):5002–5017. doi: 10.1128/JB.00542-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R. Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS Biol. 2016;14(8):e1002533. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamilton I, Worsley B, Cobden I, Cooke E, Shoesmith J, Axon A. Simultaneous culture of saliva and jejunal aspirate in the investigation of small bowel bacterial overgrowth. Gut. 1982;23(10):847–853. doi: 10.1136/gut.23.10.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zmora N, Zilberman-Schapira G, Suez J, Mor U, Dori-Bachash M, Bashiardes S, et al. Personalized gut mucosal colonization resistance to empiric probiotics is associated with unique host and microbiome features. Cell. 2018;174(6):1388–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roland B, Lee D, Miller L, Vegesna A, Yolken R, Severance E, et al. Obesity increases the risk of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO) Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2018;30(3):e13199. doi: 10.1111/nmo.13199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Drasar BS, Shiner M, McLeod GM. Studies on the intestinal flora. I. The bacterial flora of the gastrointestinal tract in healthy and achlorhydric persons. Gastroenterology. 1969;56(1):71–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Derrien M, van Hylckama Vlieg JE. Fate, activity, and impact of ingested bacteria within the human gut microbiota. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23(6):354–366. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kommedal Ø, Simmon K, Karaca D, Langeland N, Wiker HG. Dual priming oligonucleotides for broad-range amplification of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene directly from human clinical specimens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012;50(4):1289–1294. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06269-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dyrhovden R, Nygaard RM, Patel R, Ulvestad E, Kommedal O. The bacterial etiology of pleural empyema. A descriptive and comparative metagenomic study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018;25:981–986. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baker G, Smith JJ, Cowan DA. Review and re-analysis of domain-specific 16S primers. J. Microbiol. Methods. 2003;55(3):541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Větrovský T, Baldrian P. The variability of the 16S rRNA gene in bacterial genomes and its consequences for bacterial community analyses. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2):e57923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun D-L, Jiang X, Wu QL, Zhou N-Y. Intragenomic heterogeneity of 16S rRNA genes causes overestimation of prokaryotic diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013;79(19):5962–5969. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01282-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dyrhovden R, Rippin M, Øvrebø KK, Nygaard RM, Ulvestad E, Kommedal Ø. Managing contamination and diverse bacterial loads in 16S rRNA deep sequencing of clinical samples: Implications of the law of small numbers. MBio. 2021;12(3):e00598–e621. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00598-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data for this study have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) at EMBL-EBI under accession number PRJEB46597 (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/browser/view/PRJEB46597).