Abstract

Carborane is a carbon-boron molecular cluster that can be viewed as a 3D analog of benzene. It features special physical and chemical properties, and thus has the potential to serve as a new type of pharmacophore for drug design and discovery. Based on the relative positions of two cage carbons, icosahedral closo-carboranes can be classified into three isomers, ortho-carborane (o-carborane, 1,2-C2B10H12), meta-carborane (m-carborane, 1,7-C2B10H12), and para-carborane (p-carborane, 1,12-C2B10H12), and all of them can be deboronated to generate their nido- forms. Cage compound carborane and its derivatives have been demonstrated as useful chemical entities in antitumor medicinal chemistry. The applications of carboranes and their derivatives in the field of antitumor research mainly include boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT), as BNCT/photodynamic therapy dual sensitizers, and as anticancer ligands. This review summarizes the research progress on carboranes achieved up to October 2021, with particular emphasis on signaling transduction pathways, chemical structures, and mechanistic considerations of using carboranes.

Keywords: carborane, cage, antitumor, pharmacophore, drug design

Graphical abstract

The applications of carboranes in the field of antitumor treatments mainly include BNCT, BNCT/PDT dual sensitizers, and anticancer ligands. This review summarizes the research progress on carboranes as useful pharmacophores in this field, with particular emphasis on signaling transduction pathways, chemical structures, and mechanistic considerations.

Introduction

Carboranes, boron-carbon molecular cage compounds, are often viewed as the 3D analogs of benzene.1 They have a wide range of applications as useful functional building blocks in material science,2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 organometallic/coordination chemistry,11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 and medicinal chemistry.18, 19, 20, 21 In this context, considerable progress has been made in carborane functionalization.22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 The special physical and chemical properties of carboranes allow the design of carborane-containing molecules with new and better antitumor activities, and thus offer medicinal chemists a unique opportunity to explore these new chemical entities for cancer therapy.1,18, 19, 20, 21 The most recent comprehensive review regarding carboranes as pharmacophores in medicinal chemistry, by Scholz and Hey-Hawkins, appeared a decade ago,18 which did not cover the recent research progress in this area. This review highlights the major achievements in the field of carboranes as pharmacophores in antitumor medicinal chemistry, with particular emphasis on signaling transduction pathways, chemical structures, and mechanistic considerations (Figure 1).

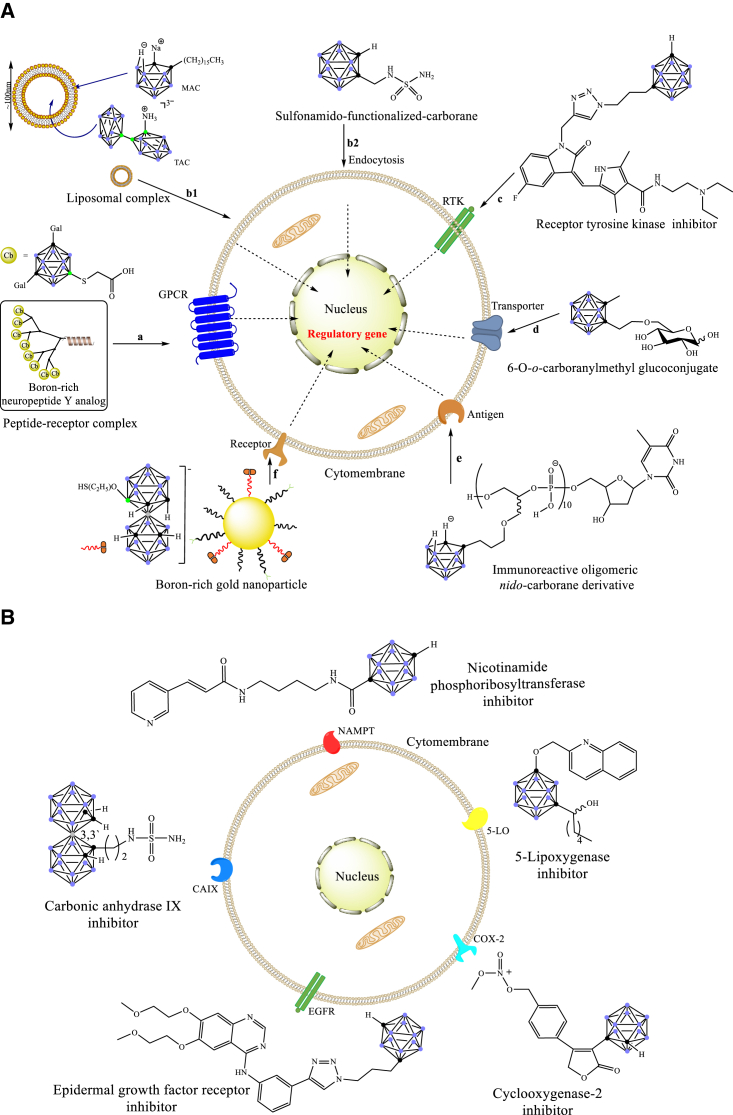

Figure 1.

Interaction of carborane derivatives and cancer cells

(A) Schematic representation of the routes of carborane derivatives entering cancer cells. (B) Carboranes bind to the skeleton of different enzyme inhibitors and interfere with receptors.

Applications of carboranes as boron neutron capture therapy agents

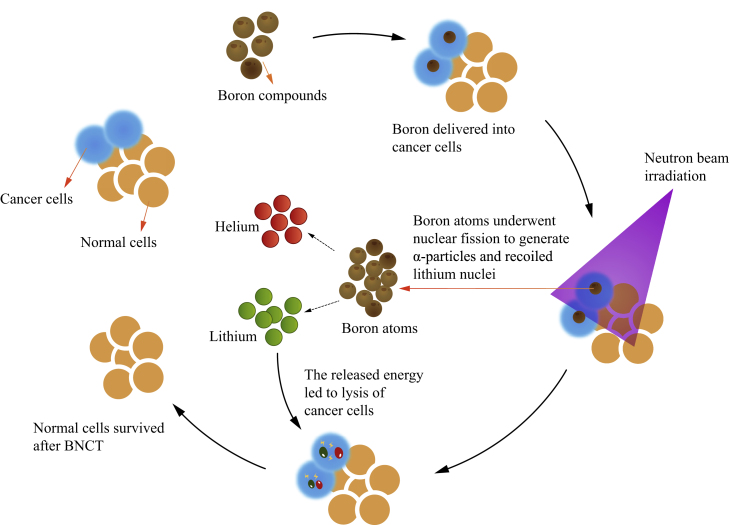

In boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT), the first step is the selective accumulation of 10B-containing compounds in cancer cells, which can be irradiated by low-energy and harmless thermal neutrons.29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 Subsequently, 10B atoms break up into α particles and lithium nuclei, yielding high linear energy transfer (LET) particles (Figure 2).29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36 As a result, 10B-containing cancer cells can be destroyed by the high-LET particles. In contrast, the surrounding normal/healthy cells can survive because of the limited path length of these particles of only 5–9 μm, which is smaller than the diameter of a general cell.29,35 If 10B-containing compounds only accumulated in cancer cells, the thermal neutron irradiation would selectively eliminate tumors under BNCT conditions (Figure 2).36 Therefore, it is critical to selectively deliver large amounts of 10B-containing compounds into cancer cells rather than normal cells. However, only two boron-containing compounds, (L)-4-dihydroxy-borylphenylalanine (BPA, 1) and sodium mercaptoundecahydro-closo-dodecarborate (BSH, 2) (Figure 3A), are currently available as BNCT agents in clinical use.37 This may be ascribed to the low selectivity for cancer cells except for brain tumors as well as head and neck cancers (HNC).38

Figure 2.

How BNCT kills tumor cells

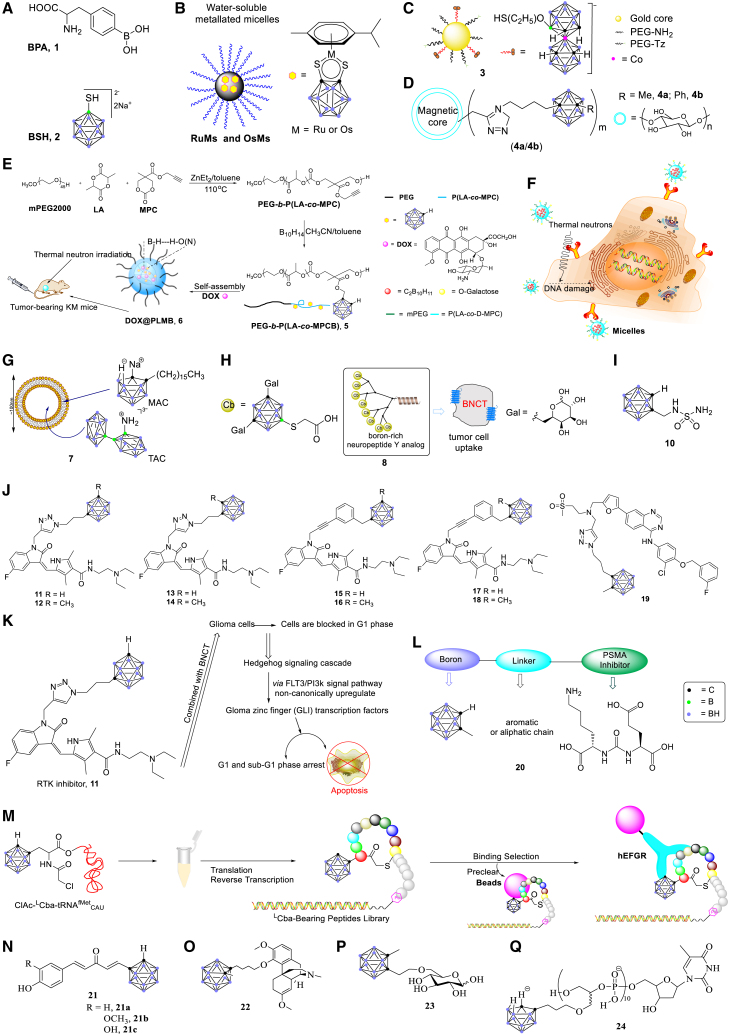

Figure 3.

Applications of carboranes in BNCT

Carboranes possess unique physical and chemical properties. They have high content of 10B atoms and the highest neutron capture cross-section. Thus they can be ideal candidates for BNCT.39 Currently, a considerable number of carborane-containing compounds have been investigated for BNCT and are discussed in the following.

Carboranes bound to nanoparticles

Nanoparticles are able to enhance permeability and retention effects as well as targeting effects, and thus can deliver 10B atoms into tumor tissues with high concentrations.40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45 Using nanomaterials to deliver 10B-containing compounds for BNCT can potentially improve drug accumulation in tumor tissues.46 Hydrophobic carborane fragments and the polymerized nanoparticles can be formed on a single backbone chain.47 Carborane derivatives bound to nanoparticles have many advantages, including high stability, high accumulation in cancer cells, and ready preparation, and have become potential drug-delivery systems for nanomedicines and BNCT.46,47

Ruthenium and osmium are a class of transition metals widely used in cancer therapy.48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 Complexes containing electron-deficient ruthenium and osmium carborane were reported by the Sadler and Hanna groups.50,51 The redox-active response of these carborane-containing complexes to biomolecules have resulted in their potential application in cancer therapy.48 Additionally, Pluronic is a kind of amphiphilic block copolymer with good biocompatibility whose nanostructures have been widely used in biomedical fields.52, 53, 54, 55 Sadler and co-workers employed Pluronic triblock copolymer P123 micelles to encapsulate 16 electron complexes, yielding polymer micelles RuMs and OsMs in water through the self-assembly of nanoparticles (Figure 3B).50 They showed greater selectivity to cancer cells as well as higher intracellular boron concentrations compared with normal cells.50,52 These findings have provided promising complexes for BNCT.

Llop and co-workers recently reported that boron-rich gold nanoparticles (AuNPs, 3) (Figure 3C) could serve as drug carriers for BNCT.56 Multifunctional AuNPs (core diameter 4.1 ± 1.5 nm) were synthesized as drug carriers with potential applications in BNCT.56 On the other hand, the Wang group reported that self-assembled gold nanoclusters were able to combine with carborane amino derivatives with good biocompatibility and stability.57 They achieved selective delivery of carborane derivatives into tumor tissues through the enhanced permeability and retention effect as well as a nanoscale effect.57

Among the nanoscale boron carriers, the carborane-loaded nanoscale covalent organic polymers (BCOPs) and magnetic nanoparticles are effective carriers in the BNCT.58, 59, 60, 61, 62 Multifunctional BCOPs were prepared from a Schiff base condensation reaction and further functionalized into BCOP-5T (five octyl chains) through alkyl chain engineering and size adjustment.58 With the loading of carborane, the 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[amino-(polyethyleneglycol)-2000] (Mw = 2000) coated with BCOP-5T exhibits excellent physiological stability and biocompatibility, and has been used as a carborane-loaded nanocarrier in BNCT.58 Hosmane and co-workers showed that through the click reaction, the carborane cage was successfully adsorbed into the modified magnetic nanoparticles (4) (Figure 3D).61

Doxorubicin (DOX) is an anthracycline antitumor antibiotic with a variety of hydroxyl and amino motifs.63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68 Although DOX has been widely used in the treatment of a variety of cancers, serious cardiotoxicity is a major challenge.63 Nanoparticle delivery systems can potentially improve the efficacy and reduce the toxicity of DOX.64, 65, 66,69 The Yan group reported that DOX combined with nanoparticles reduced the toxicity in the treatment of liver cancer.67

To achieve combined administration of DOX in BNCT and chemotherapy (Figure 3E), carborane conjugated amphiphilic copolymer PEG-b-P (LA-co-MPCB) (PLMB, 5) nanoparticles were synthesized by Huang and colleagues.68 DOX@PLMB (6) was formed by self-assembly of nanoparticles, which prevented boron compounds from leakage into the bloodstream by virtue of the covalent bond between carborane and the backbone chain of polymerization.68 Also, it was able to protect DOX from bursting release due to its dihydrogen bonding with carborane. Moreover, these authors found that the blood circulation time of DOX@PLMB was prolonged and boron accumulation was increased in tumor tissues. Therefore, DOX@PLMB has reduced systemic toxicity and an improved therapeutic effect.68

Carboranes bound to PEG/liposomes

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common cause of death from cancer.70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75 D’Souza and Devarajan reported that the asialoglycoprotein receptor (ASGPR) could serve as an ideal target specific for delivery to HCC.76 The Zhou group reported that galactose and lactose residues had a strong affinity for ASGPR.77 The carborane-containing clusters self-assembled into micelles with HCC-targeting property were synthesized by Liu and co-workers (Figure 3F).78 Compared with BSH, the carborane-containing micelles enhance the selectivity and absorptive capacity of hepatoma carcinoma cells, and thus the cytotoxicity is reduced. The micelles can weaken the migratory behavior and induce apoptosis of cancer cells by destroying double-stranded DNA during cancer treatment.78

Among the macromolecular substances, liposomes fused with cell membranes delivered boron-containing elements into tumor tissues.79, 80, 81, 82, 83 Hawthorne’s group reported using liposomes as a transport medium for boron elements.79,80 Liposomes were converted into an ammonio derivative, Na3[1-(2′-B10H9)-2NH3B10H8] (TAC), which provided high concentration and long residence time of boron in cancer cells. Hawthorne and co-workers also designed a complementary lipophilic reagent, K[nido-7CH3(CH2)15-7,8-C2B9H11] (MAC), which could be stably incorporated into the liposomal bilayer (Figure 3G).79 Subsequently, the liposomal bilayer specifically bound to receptors on the surface of cancer cells and entered into cancer cells through endocytosis.79 It was demonstrated that the inclusion of amphoteric nido-carborane in the liposomal bilayer accumulated a high concentration of boron in tumor tissues.79 Also, the application of BNCT was able to encapsulate carboranes in small unilamellar liposomes to selectively deliver 10B to synovial tissues of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA).84 Moreover, as polyethylene glycol (PEG) is biocompatible,85, 86, 87 the carborane-PEG conjugate has been used as a new type of boron carrier.85, 86, 87 The simple encapsulation of nido-carborane anions in PEG liposomes as the boron carriers of BNCT was reported by Lee et al.85 PEGylated liposomes effectively delivered boron compounds by encapsulating carborane and delivering it into tumor cells.85

Carboranes bound to peptide ligands

G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) refer to a large family of cell-surface receptors.88, 89, 90, 91, 92 As a seven-pass transmembrane protein, GPCRs that are overexpressed on the membrane of cancer cells bound to peptide ligands and thus could be used as a shuttle for tumor-directed boron absorption systems (Figure 3H).88 Among them, human Y1 receptor (hY1R),88,89 gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRPR),90 and ghrelin receptor (GhrR)91,92 have become viable targets for BNCT by virtue of their high expression on the surface of cancer cells and their ability to internalize the bound ligands. In this context, the groups of Beck-Sickinger88 and Hey-Hawkins89, 90, 91 reported that the combination of carborane and hY1R, GRPR, or GhrR could represent a boron delivery agent in BNCT for the delivery of therapeutic drugs to cancer cells. Neuropeptide Y (NPY), a peptide of the three-membered NPY hormone family,88,89 bound to hY1R to form an NPY complex (8), and the complex was internalized into cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis. Carborane was introduced into the NPY complex by solid-phase peptide synthesis. A boron-modified NPY complex was then used as the boron carrier of BNCT, which selectively delivered therapeutic drugs into breast cancer cells.88,89 The significant overexpression of GRPR in various malignant tumor tissues makes it a very attractive target,90,91 whereby carborane could be attached to the peptide conjugates targeting tumor cells through GPCRs overexpressed on cancer cell membranes. Similarly, the expression of GhrR on a variety of cancer cells makes it a viable target for BNCT.91,92 GhrR could serve as a delivery system of BNCT to deliver high doses of boron into cancer cells.92

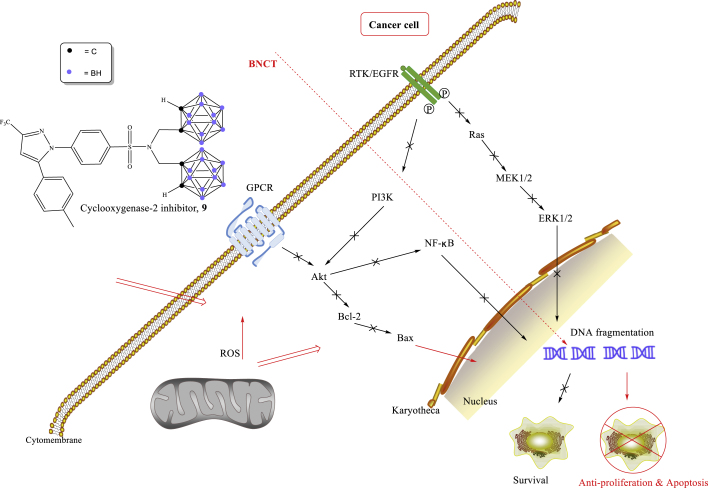

Carboranes bound to enzyme/receptor inhibitors

Cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) is highly expressed in HNC,93, 94, 95 which can be used as a potential target for HNC.96, 97, 98, 99 The Chen group developed a novel carborane-containing COX-2 inhibitor (9), which was able to induce apoptosis of cancer cells through BNCT and was effectively used for the treatment of HNC.93 It was shown that COX-2 inhibitor causes DNA double-strand breaks and forms reactive oxygen species, followed by downregulation of expression of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt) and mitogen-activated protein kinase, finally inducing apoptosis of cancer cells in BNCT (Figure 4).93

Figure 4.

Signaling pathways of a carborane-derived COX-2 inhibitor

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a type of zinc-dependent endopeptidase that participate in the remodeling and degradation of all components of the extracellular matrix.100, 101, 102, 103, 104 It has been reported that carborane can combine with MMP ligands to deliver boron atoms into cancer cells, achieving the use of BNCT for dual therapy of tumors.104

Carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX, 10) is an enzyme overexpressed in mesothelioma and breast cancer cells.105, 106, 107, 108 CAIX inhibitors specifically bind to the low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor on the surface of cancer cells to form receptor-LDL complexes, and is delivered into cancer cells through endocytosis (Figure 3I).105 Sulfonamido-functionalized-carborane (CA-SF) was discovered by the Geninatti-Crich group.105 CA-SF served as a CAIX inhibitor and boron delivery agent and has been used in BNCT (Figure 3I) to inhibit the growth of mesothelioma and breast cancer cells.

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are a subclass of tyrosine kinases that are involved in mediating cell-to-cell communication and controlling a wide range of complex biological functions.109, 110, 111, 112 Carborane-containing RTK inhibitors (11–19) were designed for the treatment of glioblastoma and prostate cancer (Figure 3J).113, 114, 115, 116 Recently, the combination of RTK inhibitors and BNCT, i.e., combination therapy, was suggested by Cerecetto and co-workers.113 They proposed a plausible mechanism whereby Hedgehog signal cascade non-canonically upregulated glioma zinc finger transcription factors via the FLT3/PI3K signaling pathway. RTK inhibitors specifically bound to receptors on the surface of cancer cells and were delivered into cancer cells through endocytosis (Figure 3K).113

Prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA), i.e., glutamate carboxypeptidase II, is an enzyme highly expressed on the surface of prostate cancer cells. PSMA is commonly used as a target for prostate cancer imaging and drug delivery.117, 118, 119, 120, 121 As boron-containing inhibitors generally had high binding affinity to PSMA, Flavell and co-workers combined PSMA inhibitor scaffolds with boric acids/carborane derivatives, delivering boron into prostate cancer cells and prostate tumor xenograft models (20, Figure 3L).119 The results showed that it was feasible to treat low-metastatic prostate cancer with PSMA containing boric acids or carboranes, thus demonstrating the potential role of PSMA in BNCT for the treatment of prostate cancer.119

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a member of the transmembrane RTK family, is involved in promoting growth, proliferation, migration, angiogenesis, and chemotherapy resistance in tumors.113,122, 123, 124, 125 Antisense oligonucleotides conjugated with boron clusters (B-ASOs) could serve as potential gene expression inhibitors and boron carriers for BNCT,126, 127, 128, 129 providing a dual-action therapeutic platform. Some B-ASOs were designed to inhibit the biosynthesis of the EGFR for BNCT.126, 127, 128 Another example of combining carborane with EGFR was to integrate L-carboranylalanine (LCba), an artificial cluster-type amino acid, into a peptide (Figure 3M), by which Suga and co-workers established a macrocyclic peptide library containing LCba residues.130 In this case, macrocyclic peptides have the advantages of high affinity for human EGFR (hEGFR) and high selectivity for hEGFR-expressing cells, as well as ready synthesis.

Curcumin, which is naturally present in turmeric plants, has been utilized to treat a variety of cancers and prevent Alzheimer's disease.131, 132, 133, 134, 135 Deagostino and co-workers found a new type of boronated analog of curcumin (21) that could be used in combination with BNCT.132 In this carborane-derived compound, β-diketone functionality was replaced by a carbonyl group while two phenolic rings were replaced by an o-carboranyl cage (Figure 3N).

Carboranes bound to sinomenine

Sinomenine is a natural bioactive alkali extracted from the root of climbing ivy and has been widely used to relieve the symptoms of RA.136 Recently, Zhu and co-workers designed and synthesized137 a carborane-containing sinomenine derivative from sinomenine to treat RA (Figure 3O).137, 138, 139 They found that the uptake of boron and compound 22 in rat C6 glioma cells was significantly higher than that of BPA and BSH. Moreover, the concentration of boron in the cancer cells indicated that compound 22 had a higher permeability to the cell membrane, which was consistent with the results of the effectiveness of killing cancer cells in vitro.137

Carboranes bound to carbohydrates/antibodies

Monosaccharides have been proven as another type of ideal candidate for BNCT, mainly due to their high water solubility, high biocompatibility, and low systemic toxicity.140, 141, 142, 143 The Ekholm group reported that monosaccharides could bind to carbohydrate transporters such as glucose transporters, and a glucoconjugate bearing an o-carboranylmethyl substituent (23) was designed and synthesized (Figure 3P).142 In addition, immune protein was proposed as a general boron delivery agent.144, 145, 146, 147 The bispecific antibody (BsMAb, 24, Figure 3Q) was used to target tumor tissues by virtue of the tumor antigen specificity of BsMAb.144 In this context, BsMAb was discovered by Hawthorne and co-workers, providing an alternative method for site-directed boron targeting.144 This bispecific antibody can potentially be used as a boron delivery agent of BNCT for cancer treatment.

Applications of carboranes as BNCT/photodynamic therapy dual sensitizer

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) and BNCT are promising cancer treatment modalities.148, 149, 150, 151, 152 Both approaches are based on the selective accumulation and retention of non-toxic sensitizer molecules (light or neutron sensitizers) in the target cells, whereby the target cells are treated by external radiation to activate the sensitizer, destroying the target cells.148 Dual therapies could thus improve therapeutic effectiveness by targeting different cellular components.148 Therefore, the synthesis of drugs with PDT and BNCT dual sensitizers have attracted much research interest.153, 154, 155

Conjugates of chlorin e6 with iron bis(dicarbollide) nanoclusters

Chlorins can accumulate in tumor tissues and have been widely used as photosensitizers for PDT.156, 157, 158, 159 Moreover, chlorins have been utilized in conjugated boron nanoclusters, such as cobalt bis(dicarbonides), which were particularly attractive as boron-containing partial conjugates of chlorins.160 Semioshkin et al. and Viñas and co-workers demonstrated that cobalt bis(dicarbollides) were non-toxic both in vivo and in vitro.161,162

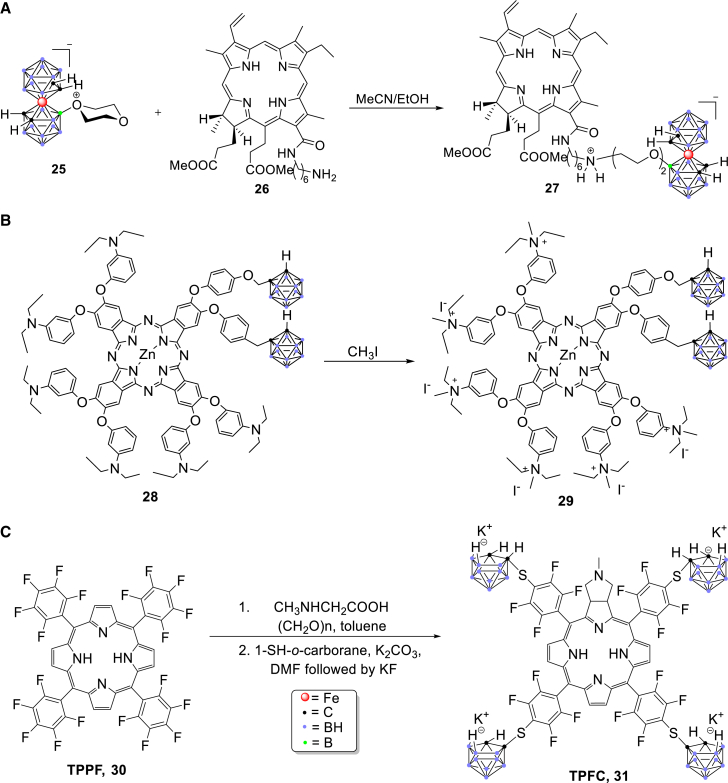

Conjugate of chlorin e6 with iron bis(dicarbollide) nanocluster (27), a dual sensitizer of BNCT and PDT, was synthesized by the Feofanov group (Figure 5A).163 They found that conjugate 27 accumulated effectively in rat glioblastoma, delivering >109 boron atoms per C6 cell (rat glioblastoma C6 cell), which resulted in 50% and 90% of photoinduced cell death with the concentrations of 35 ± 3 and 80 ± 3 nM, respectively. Therefore, this conjugate provided an alternative direction for further research regarding the combination of PDT and BNCT.163

Figure 5.

Synthesis of carborane-derived PDT/BNCT dual sensitizers

Phthalocyanine-ortho-carborane conjugates

Boronated tetrapyrrole derivatives are promising dual sensitizers for BNCT and PDT by virtue of their low cytotoxicity under dark conditions, high boron content, and good tumor affinity.164 Among these compounds, phthalocyanine (PC) has attracted much interest in cancer treatment due to its high singlet oxygen production capacity, high molar extinction coefficient, high optical stability, and strong near-infrared absorption capacity.165 In this context, a water-soluble, o-carborane-derived PC complex (29) was designed and obtained by Hamuryudan and co-workers.166 Carboranes served as the boron source of BNCT while PC played a role in PDT activation (Figure 5B). This combination greatly enhances tumor killing efficiency.

Tetrakis(p-carboranylthio-tetrafluorophenyl)chlorins

Boronated porphyrins and their derivatives can preferentially accumulate in cancer cells with low dark cytotoxicity,167, 168, 169 and thus have potential applications as BNCT/PDT dual sensitizers.167, 168, 169, 170 The Vicente group reported that boronated chlorin killed T98G cells of human glioma,171 while Pandey and co-workers found that fluorinated substituents promoted photosensitivity.172 It was also found that fluorinated porphyrins had higher photokinetic activity than their non-fluorinated counterparts.171,172 Tetrafluorophenyl porphyrin (TPPF, 30) was synthesized by Drain and co-workers through microwave reaction.153 Vicente and co-workers synthesized a novel carborane-derived sensitizer, tetrakis(p-carboranylthio-tetrafluorophenyl)chlorin (TPFC, 31) from TPPF (Figure 5C).154 The same group also reported that F98 rat glioma cells and F98 rat glioma brain tumor model could be used to evaluate the applicability of TPFC as a sensitizer. In in vitro studies, TPFC was located close to the nuclei and was highly photosensitive.173 According to the results from Vicente and colleagues, the efficacy of TPFC in the treatment of F98 rat glioma was comparable with that of BPA.154,173 Therefore, TPFC is potentially a promising dual sensitizer for PDT and BNCT.

Applications of carboranes as anticancer ligands

Estrogen receptor ligands

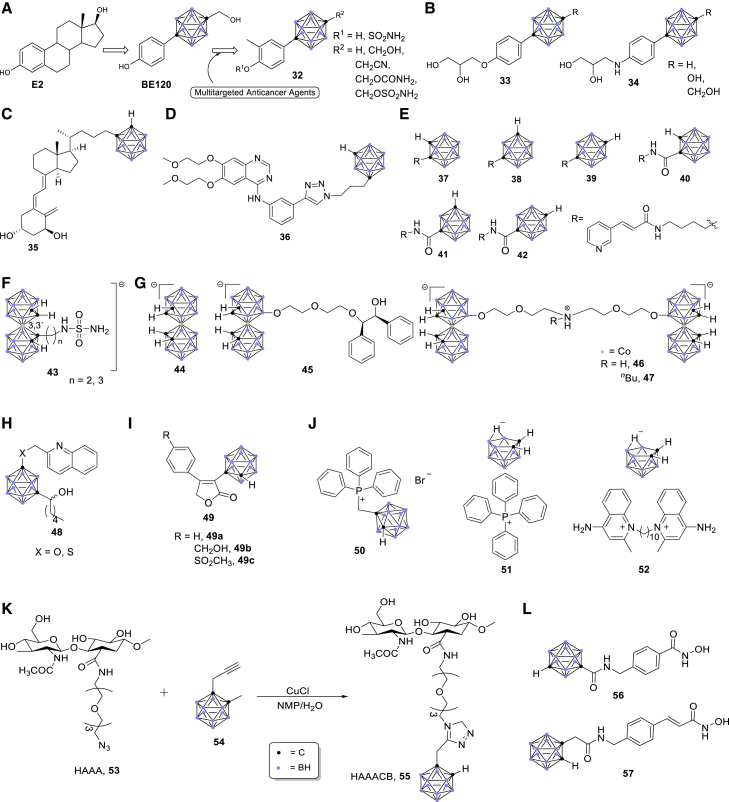

Estrogen has important functions in cardiovascular, reproductive, skeletal, and central nervous systems.174, 175, 176, 177, 178, 179, 180, 181 E2 (17β-estradiol) and E1 (precursor of E2) were synthesized from estrone sulfate by steroid sulfatase (STS).174 Therefore, STS could be considered as a promising target for the treatment of breast cancer. In this context, Ohta and co-workers employed carborane as a hydrophobic pharmacophore, and several carborane-containing compounds were synthesized for the treatment of breast cancer.174,182 Among these, 1-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-12-hydroxymethyl-p-carborane (BE120) showed a potent binding ability to the estrogen receptor α (Figure 6A).182

Figure 6.

Applications of carboranes in anticancer ligands

Androgen receptor ligands

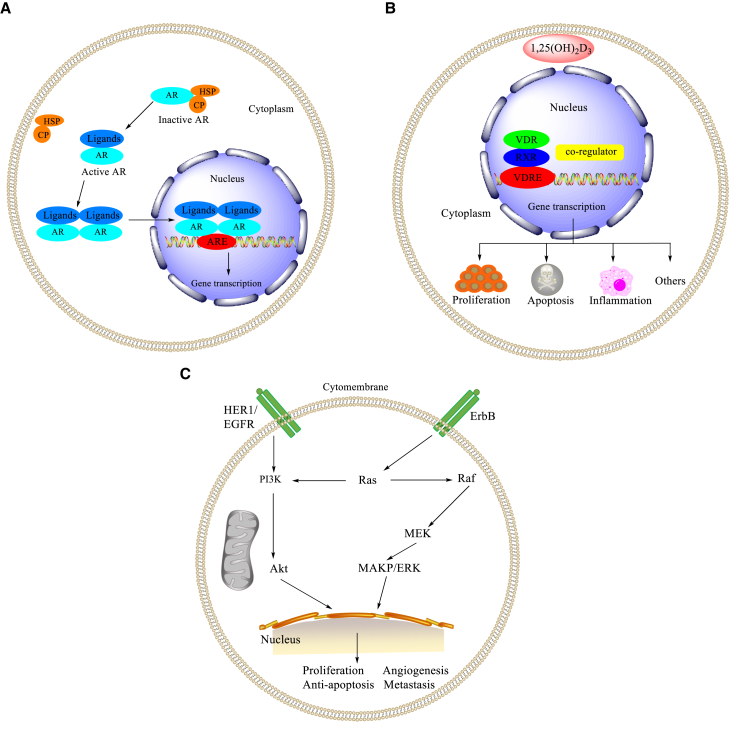

Similarly, the Ohta/Endo group developed carborane-derived compounds to target androgen receptor (AR).183,184 The AR homodimer translocated to nucleus and bound to the androgen response elements (AREs) in DNA, after which the AR-ARE complexes interacted with the promoters to regulate the target genes (Figure 7A).185 Subsequently, several carborane-containing AR ligands were developed as candidates for prostate cancer therapeutics.186, 187, 188 The carborane cage served as a hydrophobic pharmacophore for the AR ligand binding domain (AR LBD) of antagonists (33, 34) (Figure 6B).183,184

Figure 7.

Mechanisms and signaling pathways

(A) Mechanisms of gene regulation by AR. (B) Mechanisms of gene regulation by VDR. (C) Signaling pathways regulated by EGFR.

Vitamin D receptor ligands

Vitamin D nuclear receptor (VDR) is expressed in a variety of tumors and can be used as a potential target for cancer treatment.189, 190, 191, 192 A potent VDR agonist (35) with the combination of 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25D) and a carborane motif was designed and synthesized by Mouriño and colleagues,193 which represented the first example of vitamin D analog binding to the LBD of VDR (Figure 6C). 1,25D hormone regulates various physiological and pathological processes, such as cell proliferation and differentiation.193 In the nucleus, vitamin D and its analogs bind to VDR and then form the VDR-retinoid X receptor complexes, and bind to the vitamin D response element (Figure 7B).189 These results showed that carborane-derived vitamin D analogs could be employed for specific molecular recognition as well as anticancer drug design and discovery.

Epidermal growth factor receptor ligands

EGFR/ErbB1 is a member of the ErbB protein family of RTKs.194, 195, 196, 197 The signaling pathways regulated by EGF-EGFR play key roles in regulating basic cell functions, such as cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, and migration (Figure 7C).194,198 EGFR-mediated cellular events are interfered with by inhibiting EGF from binding to EGFR on the surface of cancer cells.199, 200, 201 By employing the carborane cage as a pharmacophore, Viñas’ group demonstrated that a carborane-containing erlotinib derivative, 1,7-closo-carboranylanilinoquinazoline (36, Figure 6D), had a higher affinity than its parent compound erlotinib.201

Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase receptor ligands

Nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT) is a first rate-limiting enzyme in the cycle of mammalian nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+).202, 203, 204, 205 Recent studies showed that NAMPT plays an essential role in metabolism, cell proliferation/survival, and inflammation.202, 203, 204, 205 In this context, a series of carborane-containing NAMPT inhibitors (37–42) were designed and synthesized by Nakamura and co-workers (Figure 6E).202 Among these inhibitors, compounds 41 and 42 showed significant NAMPT inhibitory activity with IC50 values of 0.098 ± 0.008 and 0.057 ± 0.001 μM, respectively (Figure 6E).202

Carbonic anhydrase ligands

CAIX is an enzyme expressed on the surface of hypoxic tumor cells.206, 207, 208, 209 This enzyme promoted the survival of tumor cells and could be a target for anticancer therapy.206,207 In this context, biscarborane-containing CAIX inhibitors (43) were designed and synthesized by the Grüner group (Figure 6F).206,210 These cobalt bis(dicarbollide) ions acted as highly potent and specific CAIX inhibitors both in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, the crystal structure of the cobaltacarborane inhibitor bound to the CAIX active site; therefore, the enzyme cavity was able to easily accommodate the cobalt bis(dicarbollide) cluster (Figure 6F).206,210

HIV protease receptor ligands

Human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) protease is a potent target in the treatment of HIV-1 infection,211, 212, 213 and is also a target for anti-HIV drug design.214, 215, 216 The Konvalinka group discovered a series of novel non-peptide protease inhibitors that were able to inhibit a variety of protease inhibitor-resistant protease species (44–47, Figure 6G).217, 218, 219 These substituted metallacarboranes were effective and selective inhibitors of wild-type and mutated HIV proteases.

5-Lipoxygenase receptor ligands

5-Lipoxygenase (5-LO) acts as a catalyst for the conversion of arachidonic acid to leukotrienes.220, 221, 222, 223 The activity of 5-LO is affected by 5-lipoxygenase activating protein (FLAP), and Rev-5901 is an early inhibitor of FLAP-mediated 5-LO activation.224 As the introduction of carborane can improve the pharmacokinetic behavior of metabolically unstable drugs,224,225 the Hey-Hawkins group introduced carborane as a highly metabolically stable pharmacophore to the traditional 5-LO inhibitors (Figure 6H).224,225 Carborane-containing Rev-5901 derivatives showed the isosteric replacement of the phenyl ring by a carborane cage, leading to improved cytotoxicity in melanoma and colon cancer cells.224

Cyclooxygenase ligands

COX-2 is involved in carcinogenesis, and increasing studies have been conducted on the potential cytotoxic properties of COX-2 selective inhibitors.226, 227, 228, 229 The incorporation of carborane units into the established anti-inflammatory drugs improved their metabolic stability.226 Hey-Hawkins and co-workers designed and synthesized several carborane-containing rofecoxib derivatives (49, Figure 6I), and these compounds showed superior selectivity against melanoma and colon cancer cells in comparison with normal cells.226

Delocalized lipophilic cation ligands

The discovery of delocalized lipophilic cations (DLCs) is a milestone of organelle-specific drug delivery.230, 231, 232, 233 Owing to the high selectivity of growth arrest of DLC-functionalized carboranes for cancer cells, such as primary glioblastoma cancer stem cells, Vizirianakis and colleagues reported that DLC-functionalized carboranes (50–52) had potential applications in selective anticancer therapeutics (Figure 6J).230, 231, 232, 233 They also demonstrated that the target-specific DLC-functionalized carboranes could act as BNCT agents.230, 231, 232, 233

Hyaluronic acid ligands

Hyaluronic acid is a highly biocompatible polysaccharide that plays an important role in cancer metastasis.234, 235, 236, 237, 238, 239, 240, 241, 242 It also interacts with various types of receptors that are overexpressed in cancer tissues.234, 235, 236 Introduction of carborane motifs can enhance the hydrophobic interaction between the bioactive compounds and their receptors and thus improve their stability and bioavailability in vivo.237, 238, 239, 240, 241, 242 Crescenzi and co-workers synthesized hyaluronan-amidoazido-carborane (HAAACB) (55) through a click-type coupling of hyaluronan-amidoazide and carboranyl alkyne (Figure 6K).237,238 They found that HAAACB could specifically interact with the CD44 receptor, leading to accumulation of boron atoms in cancer cells, which will have potential application in BNCT.237,238

Histone deacetylase ligands

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are known to be responsible for the global silencing of tumor-suppressor genes.243, 244, 245, 246, 247, 248, 249 Overexpression of HDACs was shown to be linked to several cancer types, and their selective inhibition results in potentiated anticancer effects.249 Treatment with histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACis) can reverse this process and restore normal cell function. Therefore, HDACis have emerged as valuable epigenetic modulators for the treatment of cancers.243,249 Hansen and co-workers identified the meta-carboranyl hydroxamate 56 as the hit compound with an IC50 value of 0.006 μM and a more than 280-fold selectivity for HDAC6.249 To investigate the influence of the carborane moiety, they synthesized aryl analogs for the best pan-inhibitory compound 57 and the most selective HDAC6 inhibitor 56 (Figure 6L).249 Both 56 and 57 demonstrated synergistic anticancer activity when combined with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib.249

Conclusion

This review summarizes the recent advances in carborane-containing compounds with potential applications in antitumor treatments. Carboranes have been proven as useful pharmacophores in boron delivery agents for BNCT as well as hydrophobic drug carriers for certain biological targets. The introduction of carborane moieties into the skeletons of traditional organic compounds (hits, leads, drugs) can change the activity of the drugs or drug candidates and thus regulate their effects on cancer cells, as shown in the various examples discussed in this review. Although this research area is still in its infancy, selective functionalization of carboranes to obtain various carborane-containing derivatives has received increasing research attention. Application of carboranes as antitumor pharmacophores will open a new and specialized avenue for novel drug design and discovery.

Acknowledgments

Y.C. acknowledges the research fund of Southwest Medical University (05/00040174). Z.X. is thankful to the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 81503093, 81972643, and 81672444) for financial support.

Author contributions

Z.X. conceptualized and designed this article. Y.C., F.D., and L.T. wrote and revised the manuscript. J.X., Y.Z., X.W., M.L., J.S., Q.W., and C.H.C. provided critical comments and edited the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final article.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Poater J., Solà M., Viñas C., Teixidor F. π aromaticity and three-dimensional aromaticity: two sides of the same coin? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014;53:12191–12195. doi: 10.1002/anie.201407359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bauduin P., Prevost S., Farràs P., Teixidor F., Diat O., Zemb T. A theta-shaped amphiphilic cobaltabisdicarbollide anion: transition from monolayer vesicles to micelles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2011;50:5298–5300. doi: 10.1002/anie.201100410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cioran A.M., Musteti A.D., Teixidor F., Krpetić Ž., Prior I.A., He Q., Kiely C.J., Brust M., Viñas C. Mercaptocarborane-capped gold nanoparticles: electron pools and ion traps with switchable hydrophilicity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:212–221. doi: 10.1021/ja203367h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz J.J., Mendoza A.M., Wattanatorn N., Zhao Y., Nguyen V.T., Spokoyny A.M., Mirkin C.A., Baše T., Weiss P.S. Surface dipole control of liquid crystal alignment. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:5957–5967. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Villagómez C.J., Sasaki T., Tour J.M., Grill L. Bottom-up assembly of molecular wagons on a surface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:16848–16854. doi: 10.1021/ja105542j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Qian E.A., Wixtrom A.I., Axtell J.C., Saebi A., Jung D., Rehak P., Han Y., Moully E.H., Mosallaei D., Chow S., et al. Atomically precise organomimetic cluster nanomolecules assembled via perfluoroaryl-thiol S(N)Ar chemistry. Nat. Chem. 2017;9:333–340. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saha A., Oleshkevich E., Vinas C., Teixidor F. Biomimetic inspired core-canopy quantum dots: ions trapped in voids induce kinetic fluorescence switching. Adv. Mater. 2017;29 doi: 10.1002/adma.201704238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jude H., Disteldorf H., Fischer S., Wedge T., Hawkridge A.M., Arif A.M., Hawthorne M.F., Muddiman D.C., Stang P.J. Coordination-driven self-assemblies with a carborane backbone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12131–12139. doi: 10.1021/ja053050i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koshino M., Tanaka T., Solin N., Suenaga K., Isobe H., Nakamura E. Imaging of single organic molecules in motion. Science. 2007;316:853. doi: 10.1126/science.1138690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dash B.P., Satapathy R., Gaillard E.R., Maguire J.A., Hosmane N.S. Synthesis and properties of carborane-appended C(3)-symmetrical extended pi systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:6578–6587. doi: 10.1021/ja101845m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xie Z. Advances in the chemistry of metallacarboranes of f-block elements. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002;231:23–46. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xie Z. Cyclopentadienyl-carboranyl hybrid compounds: a new class of versatile ligands for organometallic chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003;36:1–9. doi: 10.1021/ar010146i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yao Z.-J., Jin G.-X. Transition metal complexes based on carboranyl ligands containing N, P, and S donors: synthesis, reactivity and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2013;257:2522–2535. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiu Z., Ren S., Xie Z. Transition metal-carboryne complexes: synthesis, bonding, and reactivity. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011;44:299–309. doi: 10.1021/ar100156f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Estrada J., Lavallo V. Fusing dicarbollide ions with N-heterocyclic carbenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2017;56:9906–9909. doi: 10.1002/anie.201705857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Axtell J.C., Kirlikovali K.O., Djurovich P.I., Jung D., Nguyen V.T., Munekiyo B., Royappa A.T., Rheingold A.L., Spokoyny A.M. Blue phosphorescent zwitterionic iridium(III) complexes featuring weakly coordinating nido-carborane-based ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:15758–15765. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou Y.P., Raoufmoghaddam S., Szilvási T., Driess M. A bis(silylene)-substituted ortho-carborane as a superior ligand in the nickel-catalyzed amination of arenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2016;55:12868–12872. doi: 10.1002/anie.201606979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scholz M., Hey-Hawkins E. Carbaboranes as pharmacophores: properties, synthesis, and application strategies. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:7035–7062. doi: 10.1021/cr200038x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Issa F., Kassiou M., Rendina L.M. Boron in drug discovery: carboranes as unique pharmacophores in biologically active compounds. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:5701–5722. doi: 10.1021/cr2000866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Armstrong A.F., Valliant J.F. The bioinorganic and medicinal chemistry of carboranes: from new drug discovery to molecular imaging and therapy. Dalton Trans. 2007:4240–4251. doi: 10.1039/b709843j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valliant J.F., Guenther K.J., King A.S., Morel P., Schaffer P., Sogbein O.O., Stephenson K.A. The medicinal chemistry of carboranes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2002;232:173–230. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quan Y., Xie Z. Controlled functionalization of o-carborane via transition metal catalyzed B-H activation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019;48:3660–3673. doi: 10.1039/c9cs00169g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quan Y., Qiu Z., Xie Z. Transition-Metal-Catalyzed selective cage B-H functionalization of o-carboranes. Chemistry. 2018;24:2795–2805. doi: 10.1002/chem.201704937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X., Yan H. Transition metal-induced B-H functionalization of o-carborane. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019;378:466–482. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dziedzic R.M., Spokoyny A.M. Metal-catalyzed cross-coupling chemistry with polyhedral boranes. Chem. Commun. 2019;55:430–442. doi: 10.1039/c8cc08693a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quan Y., Tang C., Xie Z. Nucleophilic substitution: a facile strategy for selective B-H functionalization of carboranes. Dalton Trans. 2019;48:7494–7498. doi: 10.1039/c9dt01140d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yu W.-B., Cui P.-F., Gao W.-X., Jin G.-X. BH activation of carboranes induced by late transition metals. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2017;350:300–319. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo C., Qiu Z., Xie Z. Catalytic cage BH functionalization of carboranes via “cage walking” strategy. ACS Catal. 2021;11:2134–2140. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ali F., N S.H., Zhu Y. Boron chemistry for medical applications. Molecules. 2020;25:828. doi: 10.3390/molecules25040828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dymova M.A., Taskaev S.Y., Richter V.A., Kuligina E.V. Boron neutron capture therapy: current status and future perspectives. Cancer Commun. (Lond) 2020;40:406–421. doi: 10.1002/cac2.12089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sauerwein W.A.G., Sancey L., Hey-Hawkins E., Kellert M., Panza L., Imperio D., Balcerzyk M., Rizzo G., Scalco E., Herrmann K., et al. Theranostics in boron neutron capture therapy. Life (Basel) 2021;11:330. doi: 10.3390/life11040330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanno H., Nagata H., Ishiguro A., Tsuzuranuki S., Nakano S., Nonaka T., Kiyohara K., Kimura T., Sugawara A., Okazaki Y., et al. Designation products: boron neutron capture therapy for head and neck carcinoma. Oncologist. 2021;26:e1250–e1255. doi: 10.1002/onco.13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamana K., Kawasaki R., Sanada Y., Tabata A., Bando K., Yoshikawa K., Azuma H., Sakurai Y., Masunaga S.I., Suzuki M., et al. Tumor-targeting hyaluronic acid/fluorescent carborane complex for boron neutron capture therapy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021;559:210–216. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rykowski S., Gurda-Woźna D., Orlicka-Płocka M., Fedoruk-Wyszomirska A., Giel-Pietraszuk M., Wyszko E., Kowalczyk A., Stączek P., Bak A., Kiliszek A., et al. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of novel 3-carboranyl-1,8-naphthalimide derivatives as potential anticancer agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:2772. doi: 10.3390/ijms22052772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Evangelista L., Jori G., Martini D., Sotti G. Boron neutron capture therapy and 18F-labelled borophenylalanine positron emission tomography: a critical and clinical overview of the literature. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2013;74:91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malouff T.D., Seneviratne D.S., Ebner D.K., Stross W.C., Waddle M.R., Trifiletti D.M., Krishnan S. Boron neutron capture therapy: a review of clinical applications. Front. Oncol. 2021;11:601820. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.601820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Feiner I.V.J., Pulagam K.R., Uribe K.B., Passannante R., Simó C., Zamacola K., Gómez-Vallejo V., Herrero-Álvarez N., Cossío U., Baz Z., et al. Pre-targeting with ultra-small nanoparticles: boron carbon dots as drug candidates for boron neutron capture therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2021;9:410–420. doi: 10.1039/d0tb01880e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakase I., Katayama M., Hattori Y., Ishimura M., Inaura S., Fujiwara D., Takatani-Nakase T., Fujii I., Futaki S., Kirihata M. Intracellular target delivery of cell-penetrating peptide-conjugated dodecaborate for boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) Chem. Commun. (Camb) 2019;55:13955–13958. doi: 10.1039/c9cc03924d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen G., Yang J., Lu G., Liu P.C., Chen Q., Xie Z., Wu C. One stone kills three birds: novel boron-containing vesicles for potential BNCT, controlled drug release, and diagnostic imaging. Mol. Pharm. 2014;11:3291–3299. doi: 10.1021/mp400641u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yinghuai Z., Hosmane N.S. Applications and perspectives of boron-enriched nanocomposites in cancer therapy. Future Med. Chem. 2013;5:705–714. doi: 10.4155/fmc.13.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liko F., Hindré F., Fernandez-Megia E. Dendrimers as innovative radiopharmaceuticals in cancer radionanotherapy. Biomacromolecules. 2016;17:3103–3114. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b00929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gozzi M., Schwarze B., Hey-Hawkins E. Preparing (Metalla)carboranes for nanomedicine. ChemMedChem. 2021;16:1533–1565. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202000983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Swietnicki W., Goldeman W., Psurski M., Nasulewicz-Goldeman A., Boguszewska-Czubara A., Drab M., Sycz J., Goszczyński T.M. Metallacarborane derivatives effective against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Yersinia enterocolitica. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021;22:6762. doi: 10.3390/ijms22136762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heide F., McDougall M., Harder-Viddal C., Roshko R., Davidson D., Wu J., Aprosoff C., Moya-Torres A., Lin F., Stetefeld J. Boron rich nanotube drug carrier system is suited for boron neutron capture therapy. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:15520. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-95044-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao F., Hu K., Shao C., Jin G. Original boron cluster covalent with poly-zwitterionic BODIPYs for boron neutron capture therapy agent. Polym. Test. 2021;100:107269. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colson Y.L., Grinstaff M.W. Biologically responsive polymeric nanoparticles for drug delivery. Adv. Mater. 2012;24:3878–3886. doi: 10.1002/adma.201200420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barth R.F., Mi P., Yang W. Boron delivery agents for neutron capture therapy of cancer. Cancer Commun. (Lond) 2018;38:35. doi: 10.1186/s40880-018-0299-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Studer V., Anghel N., Desiatkina O., Felder T., Boubaker G., Amdouni Y., Ramseier J., Hungerbühler M., Kempf C., Heverhagen J.T., et al. Conjugates containing two and three trithiolato-bridged dinuclear ruthenium(II)-Arene units as in vitro antiparasitic and anticancer agents. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2020;13:471. doi: 10.3390/ph13120471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Drača D., Marković M., Gozzi M., Mijatović S., Maksimović-Ivanić D., Hey-Hawkins E. Ruthenacarborane and quinoline: a promising combination for the treatment of brain tumors. Molecules. 2021;26:3801. doi: 10.3390/molecules26133801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barry N.P., Pitto-Barry A., Romero-Canelón I., Tran J., Soldevila-Barreda J.J., Hands-Portman I., Smith C.J., Kirby N., Dove A.P., O'Reilly R.K., et al. Precious metal carborane polymer nanoparticles: characterisation of micellar formulations and anticancer activity. Faraday Discuss. 2014;175:229–240. doi: 10.1039/c4fd00098f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barry N.P., Kemp T.F., Sadler P.J., Hanna J.V. A multinuclear 1H, 13C and 11B solid-state MAS NMR study of 16- and 18-electron organometallic ruthenium and osmium carborane complexes. Dalton Trans. 2014;43:4945–4949. doi: 10.1039/c3dt53589d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiong X.Y., Tam K.C., Gan L.H. Polymeric nanostructures for drug delivery applications based on Pluronic copolymer systems. J. Nanosci Nanotechnol. 2006;6:2638–2650. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2006.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khaliq N.U., Park D.Y., Yun B.M., Yang D.H., Jung Y.W., Seo J.H., Hwang C.S., Yuk S.H. Pluronics: intelligent building units for targeted cancer therapy and molecular imaging. Int. J. Pharm. 2019;556:30–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.11.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lim C., Moon J., Sim T., Hoang N.H., Won W.R., Lee E.S., Youn Y.S., Choi H.G., Oh K., Oh K.T. Cyclic RGD-conjugated Pluronic(®) blending system for active, targeted drug delivery. Int. J. Nanomed. 2018;13:4627–4639. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S171794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Akash M.S., Rehman K. Recent progress in biomedical applications of Pluronic (PF127): pharmaceutical perspectives. J. Control. Release. 2015;209:120–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Feiner I.V.J., Pulagam K.R., Gómez-Vallejo V., Zamacola K., Baz Z., Caffarel M.M., Lawrie C.H., Ruiz-de-Angulo A., Carril M., Llop J. Therapeutic pretargeting with gold nanoparticles as drug candidates for boron neutron capture therapy. Part. Part. Syst. Charact. 2020;37:2000200. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang J., Chen L., Ye J., Li Z., Jiang H., Yan H., Stogniy M.Y., Sivaev I.B., Bregadze V.I., Wang X. Carborane derivative conjugated with gold nanoclusters for targeted cancer cell imaging. Biomacromolecules. 2017;18:1466–1472. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.6b01845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shi Y., Fu Q., Li J., Liu H., Zhang Z., Liu T., Liu Z. Covalent organic polymer as a carborane carrier for imaging-facilitated boron neutron capture therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2020;12:55564–55573. doi: 10.1021/acsami.0c15251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Guan Q., Zhou L.L., Li W.Y., Li Y.A., Dong Y.B. Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) for cancer therapeutics. Chemistry. 2020;26:5583–5591. doi: 10.1002/chem.201905150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Valenzuela C., Chen C., Sun M., Ye Z., Zhang J. Strategies and applications of covalent organic frameworks as promising nanoplatforms in cancer therapy. J. Mater. Chem. B. 2021;9:3450–3483. doi: 10.1039/d1tb00041a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhu Y., Lin Y., Zhu Y.Z., Lu J., Maguire J.A., Hosmane N.S. Boron drug delivery via encapsulated magnetic nanocomposites: a new approach for BNCT in cancer treatment. J. Nanomater. 2010;2010:409320. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liao C., Li Y., Tjong S.C. Bactericidal and cytotoxic properties of silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:449. doi: 10.3390/ijms20020449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Szuławska A., Czyz M. [Molecular mechanisms of anthracyclines action] Postepy Hig Med. Dosw (Online) 2006;60:78–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Min Y., Caster J.M., Eblan M.J., Wang A.Z. Clinical translation of nanomedicine. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:11147–11190. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li J., Zhao J., Tan T., Liu M., Zeng Z., Zeng Y., Zhang L., Fu C., Chen D., Xie T. Nanoparticle drug delivery system for glioma and its efficacy improvement strategies: a comprehensive review. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020;15:2563–2582. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S243223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Naeem M., Awan U.A., Subhan F., Cao J., Hlaing S.P., Lee J., Im E., Jung Y., Yoo J.W. Advances in colon-targeted nano-drug delivery systems: challenges and solutions. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2020;43:153–169. doi: 10.1007/s12272-020-01219-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhang X., Li J., Yan M. Targeted hepatocellular carcinoma therapy: transferrin modified, self-assembled polymeric nanomedicine for co-delivery of cisplatin and doxorubicin. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2016;42:1590–1599. doi: 10.3109/03639045.2016.1160103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Xiong H., Zhou D., Qi Y., Zhang Z., Xie Z., Chen X., Jing X., Meng F., Huang Y. Doxorubicin-loaded carborane-conjugated polymeric nanoparticles as delivery system for combination cancer therapy. Biomacromolecules. 2015;16:3980–3988. doi: 10.1021/acs.biomac.5b01311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang W., Liu X., Zheng X., Jin H.J., Li X. Biomineralization: an opportunity and challenge of nanoparticle drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2020;9 doi: 10.1002/adhm.202001117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McGlynn K.A., Petrick J.L., El-Serag H.B. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2021;73:4–13. doi: 10.1002/hep.31288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Finn R.S., Zhu A.X. Evolution of systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2021;73:150–157. doi: 10.1002/hep.31306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Huang D.Q., El-Serag H.B., Loomba R. Global epidemiology of NAFLD-related HCC: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021;18:223–238. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00381-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Llovet J.M., Zucman-Rossi J., Pikarsky E., Sangro B., Schwartz M., Sherman M., Gores G. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2016;2:16018. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pinter M., Scheiner B., Peck-Radosavljevic M. Immunotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a focus on special subgroups. Gut. 2021;70:204–214. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cheng A.L. Pursuing efficacious systemic therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021;18:95–96. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-00405-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.D'Souza A.A., Devarajan P.V. Asialoglycoprotein receptor mediated hepatocyte targeting—strategies and applications. J. Control. Release. 2015;203:126–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu D.Q., Lu B., Chang C., Chen C.S., Wang T., Zhang Y.Y., Cheng S.X., Jiang X.J., Zhang X.Z., Zhuo R.X. Galactosylated fluorescent labeled micelles as a liver targeting drug carrier. Biomaterials. 2009;30:1363–1371. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2008.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhang T., Li G., Li S., Wang Z., He D., Wang Y., Zhang J., Li J., Bai Z., Zhang Q., et al. Asialoglycoprotein receptor targeted micelles containing carborane clusters for effective boron neutron capture therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces. 2019;182:110397. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2019.110397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kueffer P.J., Maitz C.A., Khan A.A., Schuster S.A., Shlyakhtina N.I., Jalisatgi S.S., Brockman J.D., Nigg D.W., Hawthorne M.F. Boron neutron capture therapy demonstrated in mice bearing EMT6 tumors following selective delivery of boron by rationally designed liposomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2013;110:6512–6517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1303437110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maitz C.A., Khan A.A., Kueffer P.J., Brockman J.D., Dixson J., Jalisatgi S.S., Nigg D.W., Everett T.A., Hawthorne M.F. Validation and comparison of the therapeutic efficacy of boron neutron capture therapy mediated by boron-rich liposomes in multiple murine tumor models. Transl. Oncol. 2017;10:686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2017.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Moosavian S.A., Sahebkar A. Aptamer-functionalized liposomes for targeted cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2019;448:144–154. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2019.01.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Askarizadeh A., Butler A.E., Badiee A., Sahebkar A. Liposomal nanocarriers for statins: a pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics appraisal. J. Cell Physiol. 2019;234:1219–1229. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gu Z., Da Silva C.G., Van der Maaden K., Ossendorp F., Cruz L.J. Liposome-based drug delivery systems in cancer immunotherapy. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12:1054. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12111054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Watson-Clark R.A., Banquerigo M.L., Shelly K., Hawthorne M.F., Brahn E. Model studies directed toward the application of boron neutron capture therapy to rheumatoid arthritis: boron delivery by liposomes in rat collagen-induced arthritis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1998;95:2531–2534. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.5.2531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lee W., Sarkar S., Ahn H., Kim J.Y., Lee Y.J., Chang Y., Yoo J. PEGylated liposome encapsulating nido-carborane showed significant tumor suppression in boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2020;522:669–675. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.11.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li Y., Zhang T., Liu Q., He J. PEG-derivatized dual-functional nanomicelles for improved cancer therapy. Front. Pharmacol. 2019;10:808. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Boussios S., Karihtala P., Moschetta M., Karathanasi A., Sadauskaite A., Rassy E., Pavlidis N. Combined strategies with poly (ADP-Ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors for the treatment of ovarian cancer: a literature review. Diagnostics (Basel) 2019;9:87. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics9030087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Worm D.J., Hoppenz P., Els-Heindl S., Kellert M., Kuhnert R., Saretz S., Köbberling J., Riedl B., Hey-Hawkins E., Beck-Sickinger A.G. Selective neuropeptide Y conjugates with maximized carborane loading as promising boron delivery agents for boron neutron capture therapy. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63:2358–2371. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kellert M., Worm D.J., Hoppenz P., Sárosi M.B., Lönnecke P., Riedl B., Koebberling J., Beck-Sickinger A.G., Hey-Hawkins E. Modular triazine-based carborane-containing carboxylic acids—synthesis and characterisation of potential boron neutron capture therapy agents made of readily accessible building blocks. Dalton Trans. 2019;48:10834–10844. doi: 10.1039/c9dt02130b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hoppenz P., Els-Heindl S., Kellert M., Kuhnert R., Saretz S., Lerchen H.G., Köbberling J., Riedl B., Hey-Hawkins E., Beck-Sickinger A.G. A selective carborane-functionalized gastrin-releasing peptide receptor agonist as boron delivery agent for boron neutron capture therapy. J. Org. Chem. 2020;85:1446–1457. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.9b02406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Kellert M., Hoppenz P., Lönnecke P., Worm D.J., Riedl B., Koebberling J., Beck-Sickinger A.G., Hey-Hawkins E. Tuning a modular system—synthesis and characterisation of a boron-rich s-triazine-based carboxylic acid and amine bearing a galactopyranosyl moiety. Dalton Trans. 2020;49:57–69. doi: 10.1039/c9dt04031e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Worm D.J., Els-Heindl S., Kellert M., Kuhnert R., Saretz S., Koebberling J., Riedl B., Hey-Hawkins E., Beck-Sickinger A.G. A stable meta-carborane enables the generation of boron-rich peptide agonists targeting the ghrelin receptor. J. Pept. Sci. 2018;24:e3119. doi: 10.1002/psc.3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang T., Du S., Wang Y., Guo Y., Yi Y., Liu B., Liu Y., Chen X., Zhao Q., He D., et al. Novel carborane compounds based on cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors for effective boron neutron capture therapy of tongue squamous cell carcinoma. ChemistrySelect. 2020;5:14652–14660. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Eberhart C.E., Coffey R.J., Radhika A., Giardiello F.M., Ferrenbach S., DuBois R.N. Up-regulation of cyclooxygenase 2 gene expression in human colorectal adenomas and adenocarcinomas. Gastroenterology. 1994;107:1183–1188. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chan G., Boyle J.O., Yang E.K., Zhang F., Sacks P.G., Shah J.P., Edelstein D., Soslow R.A., Koki A.T., Woerner B.M., et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 expression is up-regulated in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Res. 1999;59:991–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nagaraju G.P., El-Rayes B.F. Cyclooxygenase-2 in gastrointestinal malignancies. Cancer. 2019;125:1221–1227. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yu X., Li Z. MicroRNA expression and its implications for diagnosis and therapy of tongue squamous cell carcinoma. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2016;20:10–16. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Karatas O.F., Oner M., Abay A., Diyapoglu A. MicroRNAs in human tongue squamous cell carcinoma: from pathogenesis to therapeutic implications. Oral Oncol. 2017;67:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2017.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Duz M.B., Karatas O.F., Guzel E., Turgut N.F., Yilmaz M., Creighton C.J., Ozen M. Identification of miR-139-5p as a saliva biomarker for tongue squamous cell carcinoma: a pilot study. Cell Oncol. (Dordr) 2016;39:187–193. doi: 10.1007/s13402-015-0259-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Quintero-Fabián S., Arreola R., Becerril-Villanueva E., Torres-Romero J.C., Arana-Argáez V., Lara-Riegos J., Ramírez-Camacho M.A., Alvarez-Sánchez M.E. Role of matrix metalloproteinases in angiogenesis and cancer. Front. Oncol. 2019;9:1370. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.01370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gonzalez-Avila G., Sommer B., Mendoza-Posada D.A., Ramos C., Garcia-Hernandez A.A., Falfan-Valencia R. Matrix metalloproteinases participation in the metastatic process and their diagnostic and therapeutic applications in cancer. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2019;137:57–83. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2019.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cabral-Pacheco G.A., Garza-Veloz I., Castruita-De la Rosa C., Ramirez-Acuña J.M., Perez-Romero B.A., Guerrero-Rodriguez J.F., Martinez-Avila N., Martinez-Fierro M.L. The roles of matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in human diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020;21:9739. doi: 10.3390/ijms21249739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rousselle P., Montmasson M., Garnier C. Extracellular matrix contribution to skin wound re-epithelialization. Matrix Biol. 2019;75-76:12–26. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2018.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lutz M.R., Jr., Flieger S., Colorina A., Wozny J., Hosmane N.S., Becker D.P. Carborane-containing matrix metalloprotease (MMP) ligands as candidates for boron neutron-capture therapy (BNCT) ChemMedChem. 2020;15:1897–1908. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202000470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Alberti D., Michelotti A., Lanfranco A., Protti N., Altieri S., Deagostino A., Geninatti-Crich S. In vitro and in vivo BNCT investigations using a carborane containing sulfonamide targeting CAIX epitopes on malignant pleural mesothelioma and breast cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:19274. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-76370-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pastorekova S., Gillies R.J. The role of carbonic anhydrase IX in cancer development: links to hypoxia, acidosis, and beyond. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2019;38:65–77. doi: 10.1007/s10555-019-09799-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Supuran C.T., Alterio V., Di Fiore A., K D.A., Carta F., Monti S.M., De Simone G. Inhibition of carbonic anhydrase IX targets primary tumors, metastases, and cancer stem cells: three for the price of one. Med. Res. Rev. 2018;38:1799–1836. doi: 10.1002/med.21497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lee S.H., Griffiths J.R. How and why are cancers acidic? Carbonic anhydrase IX and the homeostatic control of tumour extracellular pH. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1616. doi: 10.3390/cancers12061616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Du Z., Lovly C.M. Mechanisms of receptor tyrosine kinase activation in cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2018;17:58. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0782-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zhang Y., Xia M., Jin K., Wang S., Wei H., Fan C., Wu Y., Li X., Li X., Li G., et al. Function of the c-Met receptor tyrosine kinase in carcinogenesis and associated therapeutic opportunities. Mol. Cancer. 2018;17:45. doi: 10.1186/s12943-018-0796-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhu C., Wei Y., Wei X. AXL receptor tyrosine kinase as a promising anti-cancer approach: functions, molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Mol. Cancer. 2019;18:153. doi: 10.1186/s12943-019-1090-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Trenker R., Jura N. Receptor tyrosine kinase activation: from the ligand perspective. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2020;63:174–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2020.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Alamón C., Dávila B., García M.F., Sánchez C., Kovacs M., Trias E., Barbeito L., Gabay M., Zeineh N., Gavish M., et al. Sunitinib-containing carborane pharmacophore with the ability to inhibit tyrosine kinases receptors FLT3, KIT and PDGFR-β, exhibits powerful in vivo anti-glioblastoma activity. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:3423. doi: 10.3390/cancers12113423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Couto M., Alamón C., Nievas S., Perona M., Dagrosa M.A., Teixidor F., Cabral P., Viñas C., Cerecetto H. Bimodal therapeutic agents against glioblastoma, one of the most lethal forms of cancer. Chemistry. 2020;26:14335–14340. doi: 10.1002/chem.202002963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kanygin V., Zaboronok A., Taskaeva I., Zavjalov E., Mukhamadiyarov R., Kichigin A., Kasatova A., Razumov I., Sibirtsev R., Mathis B.J. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of fluorescently labeled borocaptate-containing liposomes. J. Fluoresc. 2021;31:73–83. doi: 10.1007/s10895-020-02637-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Couto M., Mastandrea I., Cabrera M., Cabral P., Teixidor F., Cerecetto H., Viñas C. Small-molecule kinase-inhibitors-loaded boron cluster as hybrid agents for glioma-cell-targeting therapy. Chemistry. 2017;23:9233–9238. doi: 10.1002/chem.201701965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Cimadamore A., Cheng M., Santoni M., Lopez-Beltran A., Battelli N., Massari F., Galosi A.B., Scarpelli M., Montironi R. New prostate cancer targets for diagnosis, imaging, and therapy: focus on prostate-specific membrane antigen. Front. Oncol. 2018;8:653. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Wüstemann T., Haberkorn U., Babich J., Mier W. Targeting prostate cancer: prostate-specific membrane antigen based diagnosis and therapy. Med. Res. Rev. 2019;39:40–69. doi: 10.1002/med.21508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Wang S., Blaha C., Santos R., Huynh T., Hayes T.R., Beckford-Vera D.R., Blecha J.E., Hong A.S., Fogarty M., Hope T.A., et al. Synthesis and initial biological evaluation of boron-containing prostate-specific membrane antigen ligands for treatment of prostate cancer using boron neutron capture therapy. Mol. Pharm. 2019;16:3831–3841. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.9b00464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Iravani A., Violet J., Azad A., Hofman M.S. Lutetium-177 prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) theranostics: practical nuances and intricacies. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2020;23:38–52. doi: 10.1038/s41391-019-0174-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hyväkkä A., Virtanen V., Kemppainen J., Grönroos T.J., Minn H., Sundvall M. More than meets the eye: scientific rationale behind molecular imaging and therapeutic targeting of prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) in metastatic prostate cancer and beyond. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:2244. doi: 10.3390/cancers13092244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mitchell R.A., Luwor R.B., Burgess A.W. Epidermal growth factor receptor: structure-function informing the design of anticancer therapeutics. Exp. Cell Res. 2018;371:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2018.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Harbeck N., Penault-Llorca F., Cortes J., Gnant M., Houssami N., Poortmans P., Ruddy K., Tsang J., Cardoso F. Breast cancer. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2019;5:66. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0111-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Nakada M., Kita D., Teng L., Pyko I.V., Watanabe T., Hayashi Y., Hamada J.I. Receptor tyrosine kinases: principles and functions in glioma invasion. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2020;1202:151–178. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-30651-9_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.London M., Gallo E. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) involvement in epithelial-derived cancers and its current antibody-based immunotherapies. Cell Biol. Int. 2020;44:1267–1282. doi: 10.1002/cbin.11340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ebenryter-Olbińska K., Kaniowski D., Sobczak M., Wojtczak B.A., Janczak S., Wielgus E., Nawrot B., Leśnikowski Z.J. Versatile method for the site-specific modification of DNA with boron clusters: anti-epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) Antisense oligonucleotide case. Chemistry. 2017;23:16535–16546. doi: 10.1002/chem.201702957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kaniowski D., Ebenryter-Olbińska K., Sobczak M., Wojtczak B., Janczak S., Leśnikowski Z.J., Nawrot B. High boron-loaded DNA-oligomers as potential boron neutron capture therapy and antisense oligonucleotide dual-action anticancer agents. Molecules. 2017;22:1393. doi: 10.3390/molecules22091393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Kaniowski D., Ebenryter-Olbinska K., Kulik K., Janczak S., Maciaszek A., Bednarska-Szczepaniak K., Nawrot B., Lesnikowski Z. Boron clusters as a platform for new materials: composites of nucleic acids and oligofunctionalized carboranes (C(2)B(10)H(12)) and their assembly into functional nanoparticles. Nanoscale. 2020;12:103–114. doi: 10.1039/c9nr06550d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kaniowski D., Kulik K., Ebenryter-Olbińska K., Wielgus E., Leśnikowski Z., Nawrot B. Metallacarborane complex boosts the rate of DNA oligonucleotide hydrolysis in the reaction catalyzed by snake venom phosphodiesterase. Biomolecules. 2020;10:718. doi: 10.3390/biom10050718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Yin Y., Ochi N., Craven T.W., Baker D., Takigawa N., Suga H. De novo carborane-containing macrocyclic peptides targeting human epidermal growth factor receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:19193–19197. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b09106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ashrafizadeh M., Najafi M., Makvandi P., Zarrabi A., Farkhondeh T., Samarghandian S. Versatile role of curcumin and its derivatives in lung cancer therapy. J. Cell Physiol. 2020;235:9241–9268. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Azzi E., Alberti D., Parisotto S., Oppedisano A., Protti N., Altieri S., Geninatti-Crich S., Deagostino A. Design, synthesis and preliminary in-vitro studies of novel boronated monocarbonyl analogues of Curcumin (BMAC) for antitumor and β-amyloid disaggregation activity. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;93:103324. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Noureddin S.A., El-Shishtawy R.M., Al-Footy K.O. Curcumin analogues and their hybrid molecules as multifunctional drugs. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;182:111631. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.111631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Rahban M., Habibi-Rezaei M., Mazaheri M., Saso L., Moosavi-Movahedi A.A. Anti-viral potential and modulation of Nrf2 by curcumin: pharmacological implications. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020;9:1228. doi: 10.3390/antiox9121228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Piwowarczyk L., Stawny M., Mlynarczyk D.T., Muszalska-Kolos I., Goslinski T., Jelińska A. Role of curcumin and (-)-epigallocatechin-3-O-gallate in bladder cancer treatment: a review. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1801. doi: 10.3390/cancers12071801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Long L.H., Wu P.F., Chen X.L., Zhang Z., Chen Y., Li Y.Y., Jin Y., Chen J.G., Wang F. HPLC and LC-MS analysis of sinomenine and its application in pharmacokinetic studies in rats. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2010;31:1508–1514. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Cai J., Hosmane N.S., Takagaki M., Zhu Y. Synthesis, molecular docking, and in vitro boron neutron capture therapy assay of carboranyl sinomenine. Molecules. 2020;25:4697. doi: 10.3390/molecules25204697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Yinghuai Z., Peng A.T., Carpenter K., Maguire J.A., Hosmane N.S., Takagaki M. Substituted carborane-appended water-soluble single-wall carbon nanotubes: new approach to boron neutron capture therapy drug delivery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:9875–9880. doi: 10.1021/ja0517116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Zhu Y., Lin Y., Hosmane N.S. Synthesis and in vitro anti-tumor activity of carboranyl levodopa. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;90:103090. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Itoh T., Tamura K., Ueda H., Tanaka T., Sato K., Kuroda R., Aoki S. Design and synthesis of boron containing monosaccharides by the hydroboration of d-glucal for use in boron neutron capture therapy (BNCT) Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2018;26:5922–5933. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2018.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Cheong K.L., Qiu H.M., Du H., Liu Y., Khan B.M. Oligosaccharides derived from red seaweed: production, properties, and potential health and cosmetic applications. Molecules. 2018;23:2451. doi: 10.3390/molecules23102451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Matović J., Järvinen J., Bland H.C., Sokka I.K., Imlimthan S., Ferrando R.M., Huttunen K.M., Timonen J., Peräniemi S., Aitio O., et al. Addressing the biochemical foundations of a glucose-based "Trojan horse"-strategy to boron neutron capture therapy: from chemical synthesis to in vitro assessment. Mol. Pharm. 2020;17:3885–3899. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c00630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Matović J., Järvinen J., Sokka I.K., Imlimthan S., Raitanen J.E., Montaser A., Maaheimo H., Huttunen K.M., Peräniemi S., Airaksinen A.J., et al. Exploring the biochemical foundations of a successful GLUT1-targeting strategy to BNCT: chemical synthesis and in vitro evaluation of the entire positional isomer library of ortho-carboranylmethyl-bearing glucoconjugates. Mol. Pharm. 2021;18:285–304. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c00917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Primus F.J., Pak R.H., Richard-Dickson K.J., Szalai G., Bolen J.L., Jr., Kane R.R., Hawthorne M.F. Bispecific antibody mediated targeting of nido-carboranes to human colon carcinoma cells. Bioconjug. Chem. 1996;7:532–535. doi: 10.1021/bc960050m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Liu L., Barth R.F., Adams D.M., Soloway A.H., Reisfeld R.A. Critical evaluation of bispecific antibodies as targeting agents for boron neutron capture therapy of brain tumors. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:2581–2587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Labrijn A.F., Janmaat M.L., Reichert J.M., Parren P. Bispecific antibodies: a mechanistic review of the pipeline. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18:585–608. doi: 10.1038/s41573-019-0028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Middelburg J., Kemper K., Engelberts P., Labrijn A.F., Schuurman J., van Hall T. Overcoming challenges for CD3-bispecific antibody therapy in solid tumors. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:287. doi: 10.3390/cancers13020287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Dolmans D.E., Fukumura D., Jain R.K. Photodynamic therapy for cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2003;3:380–387. doi: 10.1038/nrc1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Asano R., Nagami A., Fukumoto Y., Miura K., Yazama F., Ito H., Sakata I., Tai A. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new boron-containing chlorin derivatives as agents for both photodynamic therapy and boron neutron capture therapy of cancer. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014;24:1339–1343. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Nakahara Y., Ito H., Masuoka J., Abe T. Boron neutron capture therapy and photodynamic therapy for high-grade meningiomas. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:1334. doi: 10.3390/cancers12051334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Asano R., Nagami A., Fukumoto Y., Miura K., Yazama F., Ito H., Sakata I., Tai A. Synthesis and biological evaluation of new BSH-conjugated chlorin derivatives as agents for both photodynamic therapy and boron neutron capture therapy of cancer. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B. 2014;140:140–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Conway-Kenny R., Ferrer-Ugalde A., Careta O., Cui X., Zhao J., Nogués C., Núñez R., Cabrera-González J., Draper S.M. Ru(II) and Ir(III) phenanthroline-based photosensitisers bearing o-carborane: PDT agents with boron carriers for potential BNCT. Biomater. Sci. 2021;9:5691–5702. doi: 10.1039/d1bm00730k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Samaroo D., Soll C.E., Todaro L.J., Drain C.M. Efficient microwave-assisted synthesis of amine-substituted tetrakis(pentafluorophenyl)porphyrin. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4985–4988. doi: 10.1021/ol060946z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Hao E., Friso E., Miotto G., Jori G., Soncin M., Fabris C., Sibrian-Vazquez M., Vicente M.G. Synthesis and biological investigations of tetrakis(p-carboranylthio-tetrafluorophenyl)chlorin (TPFC) Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008;6:3732–3740. doi: 10.1039/b807836j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Li H., Fronczek F.R., Vicente M.G. Cobaltacarborane-phthalocyanine conjugates: syntheses and photophysical properties. J. Organomet. Chem. 2009;694:1607–1611. doi: 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2008.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Juzeniene A. Chlorin e6-based photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy and photodiagnosis. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2009;6:94–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pdpdt.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Steponkiene S., Valanciunaite J., Skripka A., Rotomskis R. Cellular uptake and photosensitizing properties of quantum dot-chlorin e6 complex: in vitro study. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2014;10:679–686. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2014.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Beack S., Kong W.H., Jung H.S., Do I.H., Han S., Kim H., Kim K.S., Yun S.H., Hahn S.K. Photodynamic therapy of melanoma skin cancer using carbon dot-chlorin e6-hyaluronate conjugate. Acta Biomater. 2015;26:295–305. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Zhang D., Wu M., Zeng Y., Wu L., Wang Q., Han X., Liu X., Liu J. Chlorin e6 conjugated poly(dopamine) nanospheres as PDT/PTT dual-modal therapeutic agents for enhanced cancer therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 2015;7:8176–8187. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b01027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Renner M.W., Miura M., Easson M.W., Vicente M.G. Recent progress in the syntheses and biological evaluation of boronated porphyrins for boron neutron-capture therapy. Anticancer Agents Med. Chem. 2006;6:145–157. doi: 10.2174/187152006776119135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Semioshkin A.A., Sivaev I.B., Bregadze V.I. Cyclic oxonium derivatives of polyhedral boron hydrides and their synthetic applications. Dalton Trans. 2008:977–992. doi: 10.1039/b715363e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Fuentes I., García-Mendiola T., Sato S., Pita M., Nakamura H., Lorenzo E., Teixidor F., Marques F., Viñas C. Metallacarboranes on the road to anticancer therapies: cellular uptake, DNA interaction, and biological evaluation of cobaltabisdicarbollide [COSAN] Chemistry. 2018;24:17239–17254. doi: 10.1002/chem.201803178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Ignatova A.A., Korostey Y.S., Fedotova M.K., Sivaev I.B., Bregadze V.I., Mironov A.F., Grin M.A., Feofanov A.V. Conjugate of chlorin е(6) with iron bis(dicarbollide) nanocluster: synthesis and biological properties. Future Med. Chem. 2020;12:1015–1023. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2020-0029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]