Abstract

The field of quality improvement and patient safety (QIPS) has matured significantly in emergency medicine over the past decade. From standalone, strategically misaligned, and incoherently designed QIPS projects years ago, emergency department (ED) leaders have now recognized that developing a more robust QIPS infrastructure helps prioritize and organize projects for a greater likelihood of success and impact for patients and the system. This process includes the development of a well-defined, accountable, and supported departmental QIPS committee. This can be achieved effectively using a deliberate and structured approach, such as the one described by Harvard Business School Professor John Kotter in his seminal work, “Leading Change.” Herein, we present a blueprint using this framework and include practical examples from our experience developing a robust and successful ED QIPS committee and infrastructure. The steps include how to develop a “burning platform,” select a guiding coalition of leaders, develop a strategic vision and initiatives, recruit a volunteer army of members, enable actions for the committee, generate short-term successes, sustain the pace of change, and, finally, enable the infrastructure to support ongoing improvements. This road map can be replicated by ED teams of variable sizes and settings to structure, prioritize, and operationalize their QIPS activities and ultimately improve the outcomes of their patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s43678-021-00252-2.

Keywords: Quality improvement; Patient Safety; Emergency Service, Hospital; Quality Indicators, Health Care

Résumé

Le domaine de l'amélioration de la qualité de la pratique clinique et de la sécurité des patients (AQSP) s'est considérablement développé en médecine d'urgence au cours de la dernière décennie. Alors qu'il y a quelques années, les projets d’AQSP étaient autonomes, mal alignés sur le plan stratégique et conçus de manière incohérente, les responsables des services d'urgence (SU) reconnaissent aujourd'hui que la mise en place d'une infrastructure d’AQSP plus solide permet de hiérarchiser et d'organiser les projets pour qu'ils aient plus de chances de réussir et d'avoir un impact sur les patients et le système. Ce processus comprend le développement d'un comité d’AQSP départemental bien défini, responsable et soutenu. On peut y parvenir efficacement en utilisant une approche délibérée et structurée, comme celle décrite par le professeur John Kotter de la Harvard Business School dans son ouvrage phare intitulé « Leading Change ». Dans le présent document, nous présentons un plan à l’aide de ce cadre et incluons des exemples pratiques tirés de notre expérience de l’élaboration d’un comité et d’une infrastructure d’AQSP de SU solides et réussis. Les étapes comprennent la façon d’élaborer une « plateforme brûlante », de sélectionner une coalition de dirigeants, d’élaborer une vision et des initiatives stratégiques, de recruter une armée de membres bénévoles, de permettre des actions pour le comité, de générer des succès à court terme, de maintenir le rythme du changement et enfin, permettre à l’infrastructure de soutenir les améliorations en cours. Cette feuille de route peut être reproduite par des équipes d'urgence de tailles et de contextes différents pour structurer, hiérarchiser et rendre opérationnelles leurs activités d’AQSP et, en fin de compte, améliorer les résultats de leurs patients.

Keywords: Qualité de l'acte, sécurité des patients, médecine d'urgence, indicateurs de qualité

Introduction

Since the publication of the Institute of Medicine’s seminal reports on quality and safety two decades ago, there has been significant growth in the operational and academic fields of quality improvement and patient safety (QIPS) [1, 2]. Yet, despite these advances, there remains a pressing need to improve the structure of our QIPS activities to produce measurable improvements in processes and care [3, 4]. This need has been exacerbated by the chronic lack of system capacity, the mounting burden of health care worker burnout and disengagement, and various acute crises (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic) [5–10]. While there are now more educational offerings on the topics of QIPS and how to conduct local improvement projects, there is still a paucity of resources on how to build capacity and structure these activities at the departmental level [11]. Having thoughtfully purposed departmental QIPS committees can be an effective way to structure improvement activities to ensure that they are cohesive and align strategically with the mission of the organization. These committees, if created, may also increase front-line providers’ professional engagement. However, they must be developed deliberately and organized intentionally for optimal impact and success.

The University Health Network is a tertiary care academic medical centre in Toronto with two emergency departments (EDs) that combined have more than 125,000 annual patient visits, with a growth rate of approximately 6% per year. The EDs are staffed by 85 physicians, four physician assistants, four nurse practitioners, over 200 registered nurses, and more than 50 allied health providers and support staff, as well as trainees for all health professions. Seven years ago, we set out to revamp our QIPS committee in an effort to have a measurable impact on patient experiences and outcomes. Our committee now has more than 50 interprofessional members (a dozen of whom have pursued formal training in QIPS), and we have achieved significant growth in engagement (e.g., patient focus groups driving project directions, contribution to governmental taskforces), grant funding (over $500,000 for QIPS initiatives), and academic dissemination (over 100 abstracts and 100 invited presentations, numerous social media articles read over 50,000 times in total). Over 30 quality and safety initiatives led by our QIPS committee members have been published, and Table 1 presents a selection of them with important lessons learned from each. They have ranged from improved patient care (e.g., faster diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction, more reliable collection of blood cultures, earlier provision of analgesia) and satisfaction (e.g., communication and education-oriented initiatives) to operational efficiency (e.g., optimized bed utilization and patient flow) [3, 4, 12–16].

Table 1.

Selected quality improvement and patient safety projects published

| Year | Name [Reference] | Team composition | Funding | Brief description | Lessons learned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | Improving emergency department flow through a Rapid Medical Unit [3] |

Co-Leads: nursing and medical leadership Core members: front-line providers, clerical staff |

Cost neutral to operational budget; in-kind by contributors | Patients presenting with very-low acuity concerns had disproportionately long wait times in our tertiary care centre, so we reassigned staff, modified schedules and repurposed resources to streamline their care in a dedicated area. Both physician initial assessment time (98–70 min) and total length of stay (165–130 min) decreased despite increased patient volumes, without affecting wait times for higher acuity patients | For projects that affect workflow of front-line providers, deeply embedding them in the improvement team and carefully incorporating their feedback led to ongoing iteration and sustained improvement |

| 2015 | Improved emergency department flow through optimized bed utilization [4] |

Lead: nurse (patient care coordinator) Core members: medical leadership, front-line providers (especially nurses) |

Operational budget; protected time for physician improver | Due to flow-interrupting challenges including operational bottlenecks and cultural issues, high-acuity patients were experiencing undue delays in their time waiting between triage and bed placement. We underwent seven PDSA cycles, mostly focused on optimizing communication strategies, leading to a 90th percentile time-to-bed decrease from 120 to 66 min | The most conspicuous root causes may not be the ones contributing the most to the problem, and utilizing QI process tools (e.g., Ishikawa diagram, process mapping, Pareto chart) can be extremely revealing |

| 2016 | A Quality Improvement Initiative to Decrease the Rate of Solitary Blood Cultures in the Emergency Department [16] |

Lead: physician Core members: physician assistants, physicians, nursing leadership |

Cost neutral to operational budget; admin time for physician assistant; in-kind by physicians | Sending a solitary blood culture to the laboratory (as opposed to two, as per best practice) can lead to safety gaps and resource utilization issues. We compared an educational approach to one where a forcing function was added, and this combined method led to a 71.8% relative reduction (29.5% absolute reduction) in the number of solitary samples sent | Education is necessary but not sufficient to change behaviours, and forcing functions are powerful tools that can be added |

| 2017 | Checklist for Head Injury Management Evaluation Study (CHIMES): a quality improvement initiative to reduce imaging utilization for head injuries in the emergency department [13] |

Lead: resident Core members: physician leader, clerical staff, nursing leadership, nurse practitioners, physician assistants |

Operational budget and academic practicum project for resident lead; small hospital QI grant for subsequent phase | Most patients with head injury are diagnosed with minor ones, yet a large proportion undergo computed tomography (CT) scans. Through provider education, a checklist developed iteratively by the team from evidence-based materials, improved patient communication and practice feedback on local group practices, we reduced the proportion of CT scans by 13.9% over 3 months (sustained to 8% at 16 months) without causing adverse events | Engrained practice patterns are difficult to change, but improvements can be achieved through multi-modal approaches that involve front-line providers in their development |

| 2018 | Improving timely analgesia administration for musculoskeletal pain in the emergency department [15] |

Lead: nurse practitioner Core members: physician leader, nursing leadership and front-line nurses (especially those who do triage) |

Operational budget and academic protected time for nurse practitioner lead | Musculoskeletal injuries are common presentations to EDs and patients are often in pain, but our time-to-analgesia (from patent triage) was felt to be suboptimal for patient-centred care. Through triage-initiated analgesia protocols and process improvements, a documentation aid, reference materials and targeted provider feedback, the time-to-analgesia decreased from 129 to 100 min | Interventions need to be co-designed and championed by those who will be utilizing them; otherwise, time is wasted on solutions that cannot be operationalized or will encounter unnecessary resistance |

| 2019 | Quality improvement initiative for improved patient communication in an ED rapid assessment zone [14] |

Lead: resident Core members: medical, clerical and nursing leadership |

Operational budget and academic project for resident lead; in-kind for contributors | Patient-clinician communication in the ED is challenged with time pressures and interruptions, leading to decreased patient satisfaction. We engaged patients (i.e., focus group, surveys) and providers to develop a novel tool (AEI: Acknowledge, Empathize, Inform), patient information pamphlets and a multimedia solution aimed at improving communication. It resulted in improved patient satisfaction and decreased patient anxiety | Meaningfully engaging patients in QI initiatives leads to new and improved insights that can then inform interventions that are more robust and effective |

| 2020 | Sharing and Teaching Electrocardiograms to Minimize Infarction: reducing diagnostic time for acute coronary occlusion in the emergency department [12] |

Lead: physician Core members: medical leadership, front-line physicians |

Cost neutral to operational budget; in-kind for physician lead | ECGs that do not meet classic STEMI criteria can nonetheless represent occlusion myocardial infarction, and prompt recognition of select pattern can lead to improved patient care. Through broad then recurrent and targeted multi-modal educational approaches combined with group audit and feedback, the median ECG-to-cath lab activation time decreased from 28.0 to 8.0 min, without any increase in the balancing measure of percentage of Code STEMI without culprit lesion | Educational approaches are more effective when varied (e.g., multi-modal) and repeated or recurrent, and they can be bolstered with targeted audit and feedback |

N.B. PDSA Plan-Do-Study-Act, QI quality improvement, ED emergency department, ECG electrocardiogram, STEMI ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction

Developing our QIPS committee has provided an opportunity to engage, support, and develop both leaders and staff in defining and implementing QIPS improvements on the front lines, where they have the greatest impact. This experience, driven and influenced by our collective professional experiences, has helped us crystalize our approach in a way that can now be shared as a blueprint for departments of various sizes and settings that are interested in better structuring their QIPS activities.

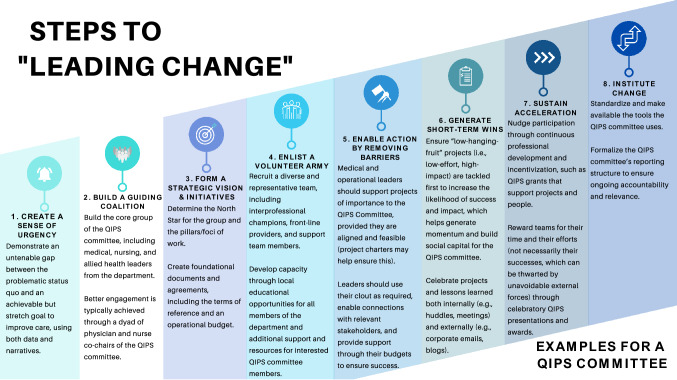

Building an emergency department quality improvement and patient safety committee

Given the numerous steps required and hurdles faced when developing a new committee—from team engagement, resource acquisition, and program organization—a structured approach is essential. An excellent approach is the Leading Change model developed by Harvard Business School Professor John Kotter [17], because it is sequential and additive, it aligns well with QIPS endeavours, and it is the most commonly used change management model in healthcare [18]. Figure 1 shows the eight chronological steps in the Kotter framework, with the relevant descriptions and examples needed to develop an effective QIPS committee.

Fig. 1.

Steps to leading change and examples for QIPS committees.

Adapted from Kotter [17]

Create a sense of urgency

The phrase “Never let a good crisis go to waste,” attributed to former White House chief of staff Rahm Emanuel, among others [19], perhaps most appropriately frames the mindset required to spark the creation of a QIPS committee. To build a “burning platform” demonstrating to stakeholders that the status quo is an untenable solution and that a future state is both necessary and attainable, a number of principles must be considered. First, identify quality and safety issues that not only resonate with the local team (i.e., those who will drive the change) but also align with the organization’s broader strategic goals (which will help secure resources and create broader impact) by engaging with relevant hospital leaders. Second, demonstrate the magnitude and importance of these issues, through both data and narrative stories, to appeal to people’s intellect and emotions. And, finally, illustrate why the status quo is more problematic than change is, framing the journey in a solution-oriented and proactive way while ensuring that the destination is both attainable and meaningfully better. While there is no perfect indicator that the platform is burning “enough”, a useful sign consists of witnessing an increasingly large number of ED team members incorporating the platform’s themes in their own thinking and discussions.

Build a guiding coalition

Concurrent to articulating the urgency and building the value proposition, it is crucial to recruit driven, diverse, respected, and knowledgeable individuals to lead the QIPS committee [20]. These people should share a common purpose and possess the influence needed to make the change efforts achievable [21]. Important stakeholders include individuals from various professions who have relevant roles and responsibilities. Table 2 presents these individuals with some of the qualifications they may have and the roles they may play, and the CAEP 2018 Symposium paper focusing on QIPS describes possible models adopted and the level of technical proficiency required in the team [11]. We believe that a dyad model of physician–nurse co-leadership (i.e., inter-professionally diverse) for the QIPS committee results in greater situational awareness and buy-in from the broader team. These co-chairs are typically charged with leading the remaining steps, supported closely by their guiding coalition. The co-chairs should be attributed both title and support, as feasible, to ensure their meaningful contribution, protected bandwidth, and legitimacy.

Table 2.

Leaders of the QIPS committee

| Guiding coalition | |

|---|---|

| Roles | Description |

| QIPS committee co-chairs |

•Dyad of physician–nurse leadership is often most effective •Advanced expertise in QIPS methodologies is very helpful (and should be supported if not already acquired) |

| Medical and nursing/allied health leadership |

•Crucial to ensuring the engagement and buy-in of the ED’s interprofessional team •Necessary to ensure the alignment of the project with organizational priorities and the commitment of funds and resources (including limited but essential administrative support), and this must be explicitly emphasized as an important contribution |

| QIPS coordinator |

•Helpful in supporting the work from an administrative and data management point of view •Position can be shared across research and other academic portfolios (e.g., a research coordinator providing one-day-a-week support to QIPS activities) |

N.B.: QIPS Quality Improvement and Patient Safety

Form a strategic vision and strategic initiatives

Once the QIPS committee’s leadership has been established, a compelling vision is required to ensure that the “future state” represents a meaningful and specific improvement. While large interprofessional visioning exercises add value, our experience is that they tend to be even more useful after some element of buy-in and early successes have already been achieved to orient members to the opportunity at hand. Vision and mission statements should be developed by and refined with the core QIPS committee’s constituency, which may help ensure that committee objectives subsequently developed are as SMART (specific, measurable, actionable, realistic, and time-defined) as possible, much like in QIPS projects themselves [22]. As shown in Table 3, numerous elements should be considered to increase the likelihood that the vision is accomplished.

Table 3.

Early elements of QIPS committee infrastructure

| Elements | Descriptions |

|---|---|

| Terms of reference | Committing to vision and mission statements that resonate with the broader team, as well as to short- and long-term objectives that appeal to both the leadership and front-line workers, is crucial to ensuring buy-in. Table 5 (in supplementary materials) provides a template for terms of reference for a QIPS committee, focusing on the roles/responsibilities as well as the rules and medico-legal framework involved [23] |

| Pillars or focus of work | It is important to focus the work that the QIPS committee will perform to address local quality gaps while considering stakeholders’ expertise and interests. This can range from broader themes (e.g., focusing on vulnerable populations) to more specific ideas (e.g., improving linkages with addiction services for patients with substance use disorder). A frequency-impact matrix can be used to help prioritize issues that are of most relevance to the team and patients [24] |

| Operational budget | When QIPS initiatives align with operational gaps and strategic priorities, and when departmental leadership is engaged, funds to support projects can be more easily found or supported through operational budgets (whether ED or hospital based). Additional and dedicated funds can be used to support time for contributors, costs for project evaluation (e.g., data analyst time), costs for dissemination (e.g., publication fees), or expenditures for activities that support the work of the committee members (e.g., a celebration event) |

N.B.: QIPS Quality Improvement and Patient Safety

Enlist a volunteer army

The members of the QIPS committee are those who will fulfill its vision, so their recruitment and engagement are the next priorities. Table 4 describes who these individuals can be, with relevant characteristics. The exact number of contributors will vary in each centre based on ED size and competing activities, but the key element is to enlist the support of those most dedicated and enthusiastic to effect change in their setting. Their identification can be facilitated by a stakeholder analysis exercise [25]. The recruitment of these players can be accomplished through a multi-modal approach via targeted discussions with promising individuals, announcements at departmental huddles, and more generic email communications. The following approaches can be used to recruit QIPS committee members and keep them engaged:

Organize recurring meetings to increase the visibility of the work being done and attract new QIPS committee members. Ensuring that departmental leadership attends these meetings will demonstrate the importance of the work and keep current members encouraged and motivated. Ensuring that employees are protected from other duties to attend and compensating physicians’ time (e.g., from admin or group funding pools) for attendance will also increase participation. Figure 2 (in supplementary materials) shows a sample agenda (with topics and descriptions) for a typical 90-min QIPS committee quarterly meeting.

Encourage would-be members to contribute to initiatives that appeal to them (i.e., create projects from the ground up, rather than with a top–down approach), perhaps initially only so they can gain experience and confidence.

Encourage and support baseline QIPS professional development for all members of the department. This will serve to: (1) enlist interested individuals to join the QIPS committee; (2) empower members with newfound skill sets and confidence to create positive change; and (3) ensure that the broader team understands the rationale for change [26].

Select promising individuals for additional coaching and mentorship, including supporting them to pursue courses or certificates/degrees to increase their expertise [27].

Table 4.

Members of the QIPS committee

| Volunteer army | |

|---|---|

| Roles | Description |

| Champions |

•Require expertise and/or interest in QIPS; they should be coached and mentored to support projects and eventually lead their own •May coach others through an approachable, supportive, and enthusiastic demeanour |

| Interprofessional front-line providers |

•Physicians, nurses, trainees, allied health professionals, etc. •Respected clinical providers with energy and commitment who want to support changes |

| Departmental staff and workers |

•Clerks, environmental services workers, information technology specialists, etc. •Possess energy and dedication to improve local care |

| Academic leadership |

•As required, in academic centres where scholarly pursuits are encouraged •Possess academic expertise and scholarly output experience to drive the effective dissemination of project results |

N.B.: QIPS Quality Improvement and Patient Safety

Enable action by removing barriers

Once the QIPS committee has been established, its leadership team drives the actual improvement work. Successful QIPS projects improve patient care, and those that also enhance provider satisfaction and reduce their frustrations are more often sustained [28]. If the perceived improvements to patient care and provider workflow are greater than the perceived efforts required to contribute to projects, providers will often want to be involved in or support QIPS projects [29]. The following are typical barriers that are encountered and their possible solutions:

Novice QIPS project leads can fail to appreciate how the risk of scope creep and the lack of broad stakeholder engagement can affect the likelihood of project success. As a general principle, if either the status quo or a system change benefits or compromises the authority or influence of a stakeholder, they need to be engaged early. The completion of a project charter at the outset of project development helps avoid these traps. Box 1 illustrates an easy-to-use template, which typically results in a project charter less than two pages in length but containing all the important information. Projects that fail to progress adequately according to the agreed upon deliverables and timelines should be assessed to determine whether greater attention or resources are needed; occasionally, these projects may need to be stopped, so that efforts and resources can be concentrated on higher yield pursuits.

Project leads can influence local processes, but they may need the collaboration of stakeholders outside their department to ensure interdepartmental success. Departmental leaders should use their connections and clout to create relevant networking opportunities. For leaders, supporting fewer projects more closely (thereby increasing their likelihood of completion and success) will often lead to a greater overall impact than attempting to encourage more projects in a superficial fashion (which may lead to more project failures).

Box 1. Sample project charter template.

Project title

What title would be short enough to be remembered while encompassing important components of your project?

Problem and background

What is the core quality issue that you are trying to improve, and what are the factors involved?

Rationale and benefits

Why is this an important problem to tackle, and what are the expected benefits?

Aim statement and deliverables

What are the goals and objectives of this project?

Scope

What are the things (people, tasks, processes) that this project will and will not address?

Measures

What are the outcome, process, and balancing measures that you are planning to assess?

Change ideas

What are you going to be attempting or changing, if already known?

Project leader, team members, and responsibilities

Who is the point person accountable for the project’s progress? Who are the other members? Who will do what?

Resources

What resources will you require—human, financial, equipment, authorizations and permissions, etc.?

Timelines and milestones

When do you anticipate starting to work on this project, implementing it, and completing it?

Generate short-term wins

Intentionally supporting projects with higher potential impacts despite requiring relatively lower efforts (i.e., low-hanging fruit) can be a simple strategy for early success that new QIPS committees often forget. These early victories are crucial to generating positive momentum. Allowing front-line workers to choose specific projects they care about (e.g., those that have a positive impact on their workflow or the direct care they provide to patients) within the themes defined by the leadership team typically leads to greater success and sustainability. Conversely, having front-line workers work on their pet project that is misaligned with organizational priorities or having leaders impose projects that fail to excite and motivate the team are two approaches that often lead to disappointment and failure.

Additional pitfalls to avoid in the selection of projects include choosing projects that necessitate significant infrastructure or workflow changes (including information technology) or that rely too much on external stakeholders for implementation (e.g., telling other professions or departments how to do their work is rarely well received, unless their involvement and engagement are significant). Relatedly, supporting only so many projects as those with QIPS expertise and bandwidth can support is key to avoid starting projects that cannot be completed. The exact number will be different based on the size and capacity of the team, but it is likely to be less than a handful in the early stages of most QIPS committees.

Celebrating early successes loudly and widely is crucial to fostering camaraderie between team members and to building momentum for the QIPS committee. This can be achieved through recognizing projects, leaders, and teams at departmental huddles and meetings and by publicizing them through organization-wide corporate messages and emails.

Sustain acceleration

After achieving early successes, the QIPS committee can build even more momentum through capacity building and incentivization. The former can be achieved through ongoing mentorship and skill set development for team members. Ensuring that their professional development is synergistic with other reporting and professional structures (e.g., hospital and university appointments) is another important consideration. Incentivization can be offered through financial support (for projects or courses) and opportunities for career advancement (e.g., representing the department on a hospital-wide committee that aligns with their interests and project). Financial support can also be constructed through a local QIPS grant competition (e.g., to compensate individuals for time spent on data collection or analysis). Having QIPS presentations at departmental grand rounds is a helpful way to recognize and celebrate the efforts of the QIPS team, regardless of their specific output or success (given that valuable learnings can be gleaned for the organization even with failed projects). These presentations can also be tied to awards, which can serve to provide a financial reward, recognize achievements in QIPS formally, and support team members in career advancement. Encouraging teams to disseminate their work externally and to publish their projects and findings are also key ways to boost morale, build credibility, and advance members’ career objectives.

Institute change

Hard-wiring lasting changes into the cultural framework of an organization is an important step in ensuring the sustainability of the QIPS committee as leaders transition. This is akin to the sustainability phase of QI projects [28], but at the higher level of the system. This includes standardizing processes for the QIPS committee, such as making available the documents included in this paper and other QIPS resources and tools (e.g., process maps, Pareto charts, and driver diagrams). Establishing the QIPS committee’s reporting structure for ongoing accountability and relevance is also needed to make its work sustainable. This can be achieved through the inclusion of the QIPS committee co-chairs in the departmental leadership structure, so they can ensure that there is bidirectional communication with the team about quality and safety concerns and initiatives. Other examples include the expectation that annual performance appraisal and activity reports will be sent to the departmental chief and operational director, who can ensure that priorities continue to be aligned. Over time, it is helpful to take stock of the QIPS committee’s progress—both successes and failures—to adjust and re-align the work, focusing on both outcomes (i.e., what patients and providers experience) and processes (i.e., what committee leaders can influence more directly). In turn, this will fuel the cycle of continuous improvement. Nowadays, more than ever, it is important to remain attuned to the QIPS committee’s bandwidth for this work and level of commitment, including and especially in terms of mental health, wellness, and burnout. Finally, there must be a growth and succession plan to ensure the QIPS committee’s work continues as leaders and organizational priorities change. This can be enabled through professional and leadership skills development for promising committee members and with a defined term length for QIPS committee co-chairs.

Conclusion

While advances in the field of quality and safety in health care have been numerous in recent years, it remains difficult for organizations to operationalize improvements in processes and outcomes at the departmental level. QIPS committees are an effective way to achieve this, especially if they are structured and empowered for success. The Leading Change framework can be applied sequentially and deliberately, as presented here in a blueprint with specific examples and tools. Importantly, departments of various sizes and types of settings can use this road map to ensure that QIPS activities are structured in ways that are most likely to lead to patient care improvements.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the physicians, nurses, trainees, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, allied health, clerical staff, and other contributors who have been committed for years to improving the quality and safety of care of the patients we serve in our community. Special thanks go to Dr. Anil Chopra, whose vision enabled the transformation and positive impacts described in this manuscript. And final thanks go to Tayler Lee Young for creating the Figure 1 infographics, as well as Carol Hilton for her comments on the manuscript.

Author contributions

The lead author (LBC) conceptualized the design of the manuscript, which was revised and edited by all authors. All authors contributed to the development, operations, evaluation, and/or sustainability of the QIPS committee described herein. The lead author (LBC) wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was reviewed critically and improved by all authors, who all approved the final version. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

There are no funding sources.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kohn LT, Corrigan J, Donaldson MS. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington: National Academy Press; 2000. p. 287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm : a new health system for the 21st century. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001. xx, p. 337

- 3.Chartier L, Josephson T, Bates K, Kuipers M. Improving emergency department flow through Rapid Medical Evaluation unit. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2015;4(1):u206156. doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u206156.w2663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chartier LB, Simoes L, Kuipers M, McGovern B. Improving Emergency Department flow through optimized bed utilization. BMJ Qual Improv Rep. 2016;5(1):u206156. doi: 10.1136/bmjquality.u206156.w2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernstein SL, Aronsky D, Duseja R, Epstein S, Handel D, Hwang U, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on clinically oriented outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16(1):1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guttmann A, Schull MJ, Vermeulen MJ, Stukel TA. Association between waiting times and short term mortality and hospital admission after departure from emergency department: population based cohort study from Ontario. Canada. BMJ. 2011;342:d2983. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stang AS, Crotts J, Johnson DW, Hartling L, Guttmann A. Crowding measures associated with the quality of emergency department care: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(6):643–656. doi: 10.1111/acem.12682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Wit K, Mercuri M, Wallner C, Clayton N, Archambault P, Ritchie K, et al. Canadian emergency physician psychological distress and burnout during the first 10 weeks of COVID-19: a mixed-methods study. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2020;1(5):1030–1038. doi: 10.1002/emp2.12225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaucher N, Trottier ED, Côté AJ, Ali H, Lavoie B, Bourque CJ, et al. A survey of Canadian emergency physicians' experiences and perspectives during the COVID-19 pandemic. CJEM. 2021;23(4):466–474. doi: 10.1007/s43678-021-00129-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee D, Jung H, Lou W, Rauchwerger D, Chartier LB, Masood S, et al. The Impact of COVID-19 on a large, Canadian community emergency department. Western J Emerg Med. 2021;22(3):572–579. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2021.1.50123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chartier LB, Mondoux SE, Stang AS, Dukelow AM, Dowling SK, Kwok ESH, et al. How do emergency departments and emergency leaders catalyze positive change through quality improvement collaborations? CJEM. 2019;21(4):542–549. doi: 10.1017/cem.2019.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaren JTT, Taher AK, Kapoor M, Yi SL, Chartier LB. Sharing and Teaching Electrocardiograms to Minimize Infarction (STEMI): reducing diagnostic time for acute coronary occlusion in the emergency department. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;48:18–32. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2021.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Masood S, Woolner V, Yoon JH, Chartier LB. Checklist for Head Injury Management Evaluation Study (CHIMES): a quality improvement initiative to reduce imaging utilisation for head injuries in the emergency department. BMJ Open Qual. 2020;9(1):e0000811. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taher A, Magcalas FW, Woolner V, Casey S, Davies D, Chartier LB. Quality improvement initiative for improved patient communication in an ED rapid assessment zone. Emerg Med J. 2020;37(12):811-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Woolner V, Ahluwalia R, Lum H, Beane K, Avelino J, Chartier LB. Improving timely analgesia administration for musculoskeletal pain in the emergency department. BMJ Open Qual. 2020;9(1):e000797. doi: 10.1136/bmjoq-2019-000797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choi J, Ensafi S, Chartier LB, Van Praet O. A quality improvement initiative to decrease the rate of solitary blood cultures in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2017;24(9):1080–1087. doi: 10.1111/acem.13161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kotter J. Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail. Harv Bus Rev. 1995;March/April:57–68.

- 18.Harrison R, Fischer S, Walpola RL, Chauhan A, Babalola T, Mears S, et al. Where do models for change management, improvement and implementation meet? A systematic review of the applications of change management models in healthcare. J Healthcare Leadership. 2021;13:85–108. doi: 10.2147/JHL.S289176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Interview with Rahm Emanuel. In: Journal. WS, editor. Last accessed: April 22, 2021. ed2008.

- 20.Collins JC. Good to great: why some companies make the leap–and others don't. 1. New York: HarperBusiness; 2001. p. 300. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kotter JP. Leading change. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press; 1996. p. 187. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chartier LB, Stang AS, Vaillancourt S, Cheng AHY. Quality improvement primer part 2: executing a quality improvement project in the emergency department. CJEM. 2018;20(4):532–538. doi: 10.1017/cem.2017.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quality of Care Information Protection Act, 2016. Quote. Ministry of Health and Long Term Care; 2016.

- 24.Provost LP, Murray SK. The health care data guide : learning from data for improvement. 1. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2011. p. 445. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chartier LB, Cheng AHY, Stang AS, Vaillancourt S. Quality improvement primer part 1: preparing for a quality improvement project in the emergency department. CJEM. 2018;20(1):104–111. doi: 10.1017/cem.2017.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chartier LB, Douglas SL, Tawadrous D, Stang AS, Vaillancourt S, Nasser L, et al. Recommendations for enhancing collaboration between the Canadian emergency department quality improvement and research communities. CJEM. 2021;23(3):303–309. doi: 10.1007/s43678-020-00079-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. Quality Improvement and Patient Safety. 2021. Available at: https://caep.ca/em-community/get-involved/qips-committee/. Accessed 22 Apr 2021.

- 28.Chartier LB, Vaillancourt S, Cheng AHY, Stang AS. Quality improvement primer part 3: evaluating and sustaining a quality improvement project in the emergency department. CJEM. 2018;21(2):261–268. doi: 10.1017/cem.2018.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayes C, [Internet]. Highly Adoptable Improvement Model; 2015 [Cited 2017 Apr 03]. Available from: http://www.highlyadoptableqi.com/index.html2015.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.