Mexico is the Latin American country with the highest prevalence and incidence of chronic noncommunicable diseases such as obesity, arterial hypertension, and diabetes. This problem has worsened in recent years because of lengthening of life expectancy and competing financial demands (1). As a consequence of an epidemiologic transition, diabetes mellitus (DM) remains the leading cause of ESKD in Latin America, and represents 51% of ESKD cases in Mexico (2); however, in approximately 30% of patients, the cause of CKD is unknown (3).

High prevalence and poor control have led to an increased mortality associated with DM and its complications, including CKD. Kidney failure in young people not related to traditional risk factors such as diabetes and hypertension has also emerged as a cause of kidney disease in the country, although hot spots have only been documented in Poncitlan, Jalisco, and Tierra Blanca, Veracruz (4). In addition, in young people such as glomerular diseases are the cause of CKD and lack of optimal care contributes to late diagnosis of the disease.

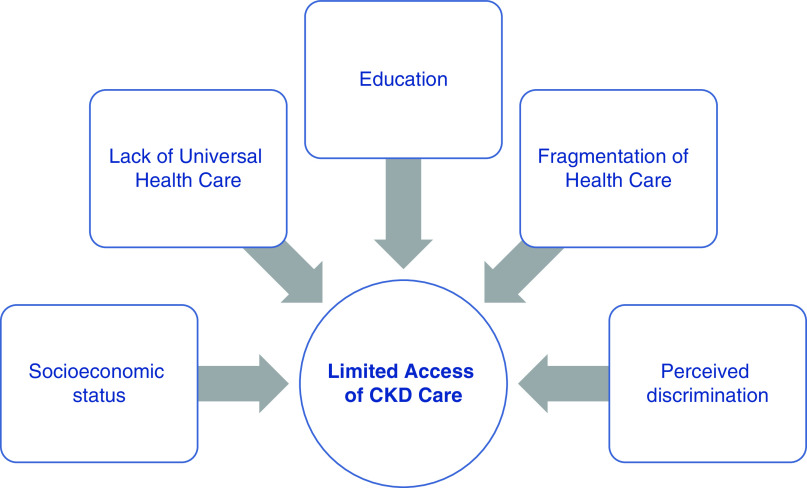

The estimated prevalence of CKD in Mexico is 9%; however, it is important to mention that despite multiple national efforts, currently Mexico lacks a national CKD or dialysis registry. Access to RRT is limited or nonexistent for the uninsured, which comprises 49% of the country’s population, and out of this 49% only 3% can afford private health insurance, leaving the rest without access to social security benefits or private health care services (5). Figure 1 shows a conceptual framework of the barriers to CKD care in Mexico.

Figure 1.

Conceptual factors of limited access of CKD care in Mexico.

Most of the health services in the country are provided by social security institutes like the Mexican Institute of Social Security (IMSS) and Institute for Social Security and Services for Civil Servants. The uninsured population access health services through the Ministry of Health, with a significant out-of-pocket cost to the people who use them (6). Significant differences are observed between the insured and uninsured Mexican populations, and universal health coverage for RRT is not available for the Mexican population (7).

In Mexico, the RRTs offered are peritoneal dialysis (PD), hemodialysis (HD), and kidney transplantation. Home HD programs are nonexistent in the country. At the beginning of the century, 15% of patients on RRT were receiving HD and 85% were receiving PD. HD has experienced progressive growth because some patients abandoned PD owing to complications (8). In addition, in 2005, private HD clinics increased in the country and national social security (IMSS) provided HD through subrogation in external HD units. The IMSS Clinical Practice Guideline established PD as the initial therapy mostly because of the lower cost, estimated at US$6000 per patient per year, compared with HD at about US$9000 per patient per year (9,10). Patients with social security can receive these treatments for free, but those without social security need to cover the costs of therapy.

Data from the IMSS reported a total of 59,754 patients on dialysis; 59% are on PD and 41% are on HD. Out of the total RRT population, 25% are on automated PD, 33% are on continuous ambulatory PD, 19% are on hospital-based HD units, and 23% are on external HD units. There is a subrogation system, where social security institutes have agreements with dialysis provider companies or other private hospitals that offer the service. Some have evaluated the HD cost between private and public dialysis units with little differences in the costs. In most centers patients are evaluated by internists or nephrologist every 1 or 2 months (10). Because of the lack of nephrologists, many HD units in the country are run by primary care physicians or internists. Some have reported the average number of dialysis treatments provided are 1.2 per week, with a duration of 3 hours per session and a cost per session of at least US$55–85. Only 2% of patients on prevalent HD receive three sessions per week and only 8% have an AVF (5) (Table 1). Méndez-Durán et al. (11) reported complications in patients on PD and patients on HD with health insurance (IMSS). The most frequent complications in patients on PD were peritonitis, volume overload, and mechanical dysfunction of the catheter; the most frequent complications in patients on HD were volume overload, hypertensive crisis, and hyperkalemia.

Table 1.

RRT in Mexico

| Country | Characteristics | Mexico |

| Prevalence (pmp) (12) | 1142 | |

| Dialysis coverage (6) | Public health insurance (nonprofit HD units) | 48% |

| No health insurance (for-profit HD units) | 49% | |

| Private health care services (for-profit HD units) | 3% | |

| No. of patients in RRT (IMSS data) (7) | 59,754 (100%) | |

| PD | 35,255 (59%) | |

| CAPD | 15,536 (26%) | |

| APD | 19,719 (33%) | |

| HD | 24,499 (41%) | |

| HH | 0 (0%) | |

| Hospital-based HD | 10,756 (18%) | |

| External HD units | 13,743 (23%) | |

| Average length of HD treatment | 3 h, 1.2 sessions/wk | |

| Vascular access type | VC | 92% |

| AVF | 8% | |

| Dialysis nursing staff (12) | Nurses | 70% |

| Technicians | 30% | |

| Nurse-to-patient ratio | 1:3 | |

| Patient follow-up frequency | Once every 1–3 mo | |

| Cost per yr (US$) (11) | PD | $6000 |

| HD | $9000 |

pmp, per million population; HD, hemodialysis; IMSS, Mexican Institute of Social Security; PD, peritoneal dialysis; CAPD, continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis; APD, automated peritoneal dialysis; HH, home hemodialysis; VC, vascular catheter; AVF, arteriovenous fistula.

In Mexico, the Official Norm for the Practice of HD, updated in early 2017, recommends having HD equipment for the exclusive use of seropositive patients (hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and HIV). Therefore, screening for these infections is done at the start of therapy and controls are made every 4 months. Patients who are seronegative for hepatitis B surface antigen should be vaccinated for hepatitis B. Although the Official Norm allows reuse of dialysis filters for a maximum of 12 times, most HD clinics do not reuse them (12).

The above data represents insured patients, but the outcomes for those who are uninsured are not comparable. Mexico has the sixth highest CKD mortality rate in the world (13). The CKD mortality rate between 1990 and 2017 increased 102% in Mexico. Agudelo-Botero et al. (14) found that men have a greater mortality rate for CKD than women (64.9 [95% CI, 61.6 to 67.3] versus 52.2 [95% CI, 50.5 to 53.7]).

Garcia-Garcia et al. (3) reported major incident and prevalent rates of dialysis of 327 per million population (pmp) and 939 pmp in the insured population compared with 99 pmp and 166 pmp in the noninsured population. Many uninsured Mexican patients with CKD refuse dialysis, have very advanced disease at the time of first nephrologic evaluation, eventually abandon their treatment, and have exceedingly high rates of mortality after dialysis initiation. Valdez et al. (15)reported the poor outcomes in the noninsured population in 850 patients with ESKD. Approximately 85% of patients started RRT as an emergency owing to uremic syndrome, hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, or acute pulmonary edema. The majority had not been seen by a nephrologist. Overall survival reached 46% at 3 years of follow-up and, as expected, survival depended on the duration and the quality of the RRT offered. For instance, survival was 100% for kidney transplant, 73% for continuous ambulatory PD, 8% for patients that received HD only when it became an emergency (intermittent HD), and 11% for patients on emergency PD or intermittent PD. Also, mortality rate was higher in patients without health insurance than patients with health insurance (57% versus 38%). This alarming data reflects the fact that uninsured patients with intermittent modalities and poor economic conditions experience the worst outcomes (15).

Although the kidney transplant rate has increased from 1.57 pmp in 1984 to 22.8 pmp in 2015, only 2939 kidney transplants were done in the country in 2019 and 17,189 patients are currently on the deceased donor list (16). Because the cost of kidney transplantation and immunosuppressive therapy is not provided for uninsured patients, the kidney transplantation rate is lower in patients without social security (5). In fact, transplant rates are 72 pmp in the insured population versus 7.5 pmp in the noninsured population (3). Despite these barriers, survival is superior among those uninsured patients that undergo kidney transplantation, even if immunosuppressive therapy is not warranted.

In 2003 the Seguro Popular (Popular Insurance) program was funded by the federal government in order to have universal health coverage for all diseases; however, CKD and RRT were never covered by this entity (10). On January 1, 2020, the Health Institute for Welfare (Instituto de Salud para el Bienestar) was implemented to replace Popular Insurance. According to the government, this entity is designed to provide medical services at the first and second level of care to all people who lack social security. However, as of the time of writing, there is still no coverage for RRT (17).

Few strategies are required in order to improve our health system. First, it is essential to create a National Health Program that focuses on preventing chronic noncommunicable diseases such obesity, DM, and hypertension. Second, the first level of care should be strengthened and universal coverage for CKD guaranteed. Third, the increase of public investment in health and decrease in out-of-pocket expenses is urgently needed. Fourth, a main governing body would allow for the elimination of the fragmentation of the health system, the decentralization of dialysis and transplant programs, and the regulation of bidding systems that allow economically accessible dialysis therapy. Finally, early referral to nephrologists is a key point for timely treatment and preventing the progression to ESKD. Because there are only nine nephrologists per 1 million inhabitants, it is imperative that primary care physicians can identify and treat CKD at earlier stages.

In conclusion, CKD care in Mexico is suboptimal. Outcomes are far worse in the uninsured population. Urgent recognition of CKD by the authorities as a public health problem is warranted in order to optimize health care services and improve access to care in the CKD population.

Disclosures

All authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

None.

Author Contributions

M. Madero and E. Vasquez-Jimenez wrote the original draft of the manuscript.

Footnotes

This article contains a podcast at https://www.asn-online.org/media/podcast/K360/2020_06_25_K3602020000091.mp3

References

- 1.Obrador GT, Rubilar X, Agazzi E, Estefan J: The challenge of providing renal replacement therapy in developing countries: The Latin American Perspective. Am J Kidney Dis 67: 499–506, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cusumano AM, Garcia-Garcia G, Gonzalez-Bedat MC, Marinovich S, Lugon J, Poblete-Badal H, Elgueta S, Gomez R, Hernandez-Fonseca F, Almaguer M, Rodriguez-Manzano S, Freire N, Luna-Guerra J, Rodriguez G, Bochicchio T, Cuero C, Cuevas D, Pereda C, Carlini R: Latin American Dialysis and Transplant Registry: 2008 prevalence and incidence of end-stage renal disease and correlation with socioeconomic indexes. Kidney Int Suppl (2011) 3: 153–156, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Garcia G, Monteón-Ramos JF, García-Bejarano H, Gomez-Navarro B, Reyes IH, Lomeli AM, Palomeque M, Cortes-Sanabria L, Breien-Alcaraz H, Ruiz-Morales NM: Renal replacement therapy among disadvantaged populations in Mexico: A report from the Jalisco Dialysis and Transplant Registry (REDTJAL). Kidney Int Suppl 68: S58–S61, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.García-García G, Gutiérrez-Padilla A, Pérez-Gómez HR, Chavez-Iñiguez JS, Morraz-Mejia EF, Amador-Jimenez MJ, Romero-Muñoz AC, Gonzalez-De la Peña MDM, Klarenbach S, Tonelli M: Chronic kidney disease of unknown cause in Mexico: The case of Poncitlan, Jalisco [published online ahead of print Aug 9, 2019]. Clin Nephrol doi: 10.5414/CNP92S107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.García-García G, Chávez-íñiguez JS: The tragedy of having ESRD in Mexico. Kidney Int Rep 3: 1027–1029, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tirado-Gómez LL, Durán-Arenas JL, Rojas-Russell ME, Venado-Estrada A, Pacheco-Domínguez RL, López-Cervantes M: Las unidades de hemodiálisis en México: Una evaluación de sus características, procesos y resultados. Salud Publica Mex 53[Suppl 4]: S491–S498, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knaul FM, González-Pier E, Gómez-Dantés O, García-Junco D, Arreola-Ornelas H, Barraza-Lloréns M, Sandoval R, Caballero F, Hernández-Avila M, Juan M, Kershenobich D, Nigenda G, Ruelas E, Sepúlveda J, Tapia R, Soberón G, Chertorivski S, Frenk J: The quest for universal health coverage: Achieving social protection for all in Mexico. Lancet 380: 1259–1279, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peña JC: Transición y equilibrio de la diálisis peritoneal y la hemodiálisis en la próxima década. Nefrología Mexicana 23: 77–81, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tratamiento sustitutivo de la función renal. Diálisis y Hemodiálisis en la insuficiencia renal crónica. México, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, 2014

- 10.Garcia-Garcia G, Garcia-Bejarano H, Breien-Coronado H, Perez-Cortez G, Pazarin-Villaseñor L, Torre-Campos L, Alcantar-Vallin L: End-stage renal disease in Mexico. In: Chronic Kidney Disease in Disadvantaged Populations, edited by Garcia Garcia G, Agodoa L, Norris K, New York, Elsevier, 2017, pp 77–82. Available at: http://www.imss.gob.mx/sites/all/statics/guiasclinicas/727GER.pdf. Accessed February 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Méndez-Durán A, Ignorosa-Luna MH, Pérez-Aguilar G, Rivera-Rodríguez FJ, González-Izquierdo JJ, Dávila-Torres J: Estado actual de las terapias sustitutivas de la función renal en el Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc 54: 588–593, 2016 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mexicana Norma Oficial NOM-003-SSA3-2016, Para la Práctica de Hemodiálisis,2017. Available at: http://www.dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5469489&fecha=20/01/2017. Accessed January 2020

- 13.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation : GBD Compare Visualization Tool, 2019. Available at: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/. Accessed February 2020

- 14.Agudelo-Botero M, Valdez-Ortiz R, Giraldo-Rodríguez L, González-Robledo MC, Mino-León D, Rosales-Herrera MF, Cahuana-Hurtado L, Rojas-Russell ME, Dávila-Cervantes CA: Overview of the burden of chronic kidney disease in Mexico: Secondary data analysis based on the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. BMJ Open 10: e035285, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valdez-Ortiz R, Navarro-Reynoso F, Olvera-Soto MG, Martin-Alemañy G, Rodríguez-Matías A, Hernández-Arciniega CR, Cortes-Pérez M, Chávez-López E, García-Villalobos G, Hinojosa-Heredia H, Camacho-Aguirre AY, Valdez-Ortiz Á, Cantú-Quintanilla G, Gómez-Guerrero I, Reding A, Pérez-Navarro M, Obrador G, Correa-Rotter R: Mortality in patients with chronic renal disease without health insurance in Mexico: Opportunities for a National Renal Health policy. Kidney Int Rep 3: 1171–1182, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centro Nacional de Trasplantes : Reporte Anual 2019 de Donación y Trasplantes en México, 2019. Available at: http://cenatra.salud.gob.mx/transparencia/trasplante_estadisticas.html. Accessed January 2020

- 17.Secretaría de Salud : Ley General de Salud, Secretaría de Salud, 2019. Available at: https://dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5583029&fecha=28/12/2019. Accessed January 2020