Abstract

There is a wealth of literature investigating the role of family involvement within care homes following placement of a relative with dementia. This review summarises how family involvement is measured and aims to address two questions: (1) which interventions concerning family involvement have been evaluated? And (2) does family involvement within care homes have a positive effect on a resident’s quality of life and behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia? After searching and screening on the three major databases PsycINFO, MEDLINE and CINAHL Plus for papers published between January 2005 and May 2021, 22 papers were included for synthesis and appraisal due to their relevance to family involvement interventions and or family involvement with resident outcomes. Results show that in 11 interventions designed to enhance at least one type of family involvement, most found positive changes in communication and family–staff relationships. Improvement in resident behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia was reported in two randomised controlled trials promoting partnership. Visit frequency was associated with a reduction of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia for residents with moderate dementia. Family involvement was related to positive quality of life benefits for residents. Contrasting results and methodological weaknesses in some studies made definitive conclusions difficult. Few interventions to specifically promote family involvement within care homes following placement of a relative with dementia have been evaluated. Many proposals for further research made over a decade ago by Gaugler (2005) have yet to be extensively pursued. Uncertainty remains about how best to facilitate an optimum level and type of family involvement to ensure significant quality of life and behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia benefits for residents with dementia.

Keywords: family involvement measurement; family involvement interventions; family participation; resident outcomes; behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia BPSD; quality of life, residential, nursing and care homes; family visits and contact

Introduction

Family involvement within care homes following placement of a relative with dementia is essential for ensuring increased transparency and partnership between the care provider and client (Care Quality Commission (CQC), 2015; Department of Health, 2013; van der Steen et al. 2014). In 2005, a major review of approximately 100 studies pertaining to family involvement in residential long-term care was published (Gaugler, 2005). Gaugler recommended that future research demonstrates links between family involvement and resident outcomes and evaluate interventions to refine the literature. Now, in 2021, we ask, How far have we come? Have Gaugler’s (2005) research recommendations been followed and what have researchers discovered? This paper recaps Gaugler’s findings and explores these questions.

How is family involvement defined and measured?

Family involvement is defined as a multidimensional construct that can entail visiting, advocacy, supervising, monitoring and evaluating care, development of care partnerships and foundation care: personal, instrumental, preservative and psychosocial (Hayward et al., 2021).

Until very recently there was no single, comprehensive and robust measure that addressed the multifaceted domains of family involvement. Historically, studies have relied on the Murphy et al. (2000) Involvement scale and Montgomery (1994) ‘Family Involvement in Care’ scale. These scales appear to be similar; they measure visiting and participation in care activities, such as contact through telephone calls and letters, laundry, helping the resident walk, engagement in games and monitoring finances. They have been modified by other researchers to ensure they are fit for purpose. For an example of this see Zimmerman et al. (2013).

Reid et al. (2007) explored two measures; the family perceived involvement (F-INVOLVE) comprised of 20 items and the importance of involvement (F-IMPORTANT) comprised of 18 items. These measured the extent to which families perceive they are involved in the care of their relative and the importance they attach to being involved.

The family perceptions of caregiving role (FPCR) is a measure that includes elements related to family involvement such as role deprivation though its focus is family member wellbeing (Maas & Buckwalter, 1990). The Family Visit Scale for Dementia (FAVS-D) measures the quality of visits between family caregivers and residents with dementia (Volicer & DeRuvo, 2008). Few papers have been published regarding the psychometric properties of these instruments.

Existing literature; Gaugler and more

Gaugler (2005) made specific reference to eight studies involving residents with dementia in his seminal review. He highlighted a lack of studies exploring family involvement and resident psychosocial outcomes. Three family involvement intervention studies were reported. One found improvements in family–staff communication, another established family–staff partnership and the third intervention demonstrated a reduction in family–staff conflict. Findings from a paper related to one of the same interventions indicated that the Family Involvement in Care intervention had beneficial effects for family and staff though no significant benefit for residents (Maas et al. 2004).

While these studies appear to demonstrate a positive impact for families from their involvement with care homes, the synthesis is over 15 years old. It remains uncertain whether overall, family involvement interventions have a positive influence on resident outcomes and quality of life. Instead, we rely on three broader reviews looking at the course of resident behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD).

All three reviews pointed out the heterogeneity of studies. Two focussed on residents in care homes and found substantial variation in the path of BPSD between individual symptoms (Selbæk et al. 2017; Wetzels et al. 2010). The other review reported significant differences in the longitudinal courses of different BPSD and highlighted apathy; the only symptom with high baseline prevalence, persistence and incidence during the progression of dementia (van der Linde et al. 2016).

Petriwskyj et al. (2014) conducted a review of 26 studies published between 1990 and 2013 and primarily focussed on family choices relating to medical issues rather than wider promotion of family involvement with care. A meta-ethnographic review by Graneheim et al. (2014) focused on family role change and adjustment. Interventions to facilitate family involvement following placement of a resident with dementia were not specifically considered.

Müller et al. (2017) completed a systematic review focussed on identifying interventions to support people with dementia and their caregivers during the transition from home care to nursing home care. They discovered that there were no dementia-specific interventions relating to family and no emphasis on promoting ongoing family involvement post relocation. Instead, reducing caregiver burden was the main objective.

A systematic literature review by Riesch et al. (2018) investigated dementia-specific training for nursing home staff since 2006 and yielded 18 studies. Family dynamics and family related training topics were found to be consistently missing from training curriculums. Authors highlighted this was in stark contrast to recommendations by Alzheimer’s Association and The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence who advocate family dynamics being a key topic.

Current literature review

This review provides an update on global developments of family involvement with care homes, specific to relatives living with dementia. It spans over 15 years and considers two research topics to address the gaps described above:

1. Which interventions concerning family involvement within care homes have been evaluated?

2. Does family involvement within care homes have a positive effect on residents’ BPSD and quality of life?

Research design and methodology

This literature review is based on the York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (University of York, 2009) guidelines on conducting systematic literature reviews in healthcare. The full inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows:

Inclusion criteria

Randomised controlled trial (RCT) designs, quasi-experimental designs, interrupted time-series designs with the family member or family member and their relative as own comparison and qualitative studies.

Families (or those most responsible for caregiving and informal caregivers, of all ages) with a relative with dementia residing in a residential care home or nursing home.

Studies where N ≥ 10.

Published in English in peer-reviewed journals between 2005 and May 2021.

Training or interventions for staff, families (or families and residents) that pertained to family involvement or partnership with long-term care providers and related resident psychosocial outcomes.

Exclusion criteria

Studies, training or interventions solely set in home care, assisted community living or inpatient settings.

Training or interventions for staff and/or residents that do not involve families.

Family interventions focused solely on physical, medical or non-psychological outcomes, for example, decisions about psychotropic medication.

Studies focused exclusively on caregiver burden, stress or wellbeing

End-of-life or advanced care planning (ACP) studies where family involvement was not of primary interest.

Search strategy

In January 2016, databases PsycINFO, MEDLINE and CINAHL Plus were searched for papers published between 2005 and 2015. This search was extended in May 2019 and again in 2021. Key terms were entered into Keyword, Subject heading and Ovid. mp searches in order to find studies pertaining to family involvement (‘family’, ‘families’, ‘informal caregiver’, ‘involvement’, ‘engagement’, ‘participation’, ‘role/roles’, ‘interaction’ and ‘visit/visiting’) within a care home setting (‘care home’, ‘residential care’, ‘residential aged care’, ‘nursing home’, ‘skilled nursing facility/facilities’, ‘institutionalisation’ and ‘long-term care’) for relatives with a diagnosis of dementia (‘dementia’, ‘Alzheimer’s’ and ‘Alzheimer’s disease’). Key phrases were also used to ensure a broad search (‘working with families’ and ‘family-staff relationships’).

Three authors reviewed the papers ensuing from the search by title, abstract and full paper according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A snowball sampling strategy was used as reference lists from systematic reviews and each selected paper were examined to identify additional studies.

Quality rating

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) – Version 2011 developed by Pluye et al. (2011) was chosen to assess the quality of studies as it enables the rating of studies with various methodologies. Permission to use the MMAT was obtained from the authors. Four researchers applied the tool and sought consensus when any differences arose.

Ratings of quality were based on a 21-criteria checklist involving two screening questions for all studies and five sections; qualitative (four criteria), quantitative (randomised, non-randomised and descriptive, all with four criteria each) and mixed methods (three criteria). The sections and subsets of criteria were applied according to the type of study being reviewed. Responses to rating questions included ‘Yes’, ‘No’ and ‘Can’t tell’.

Papers received a score denoted by descriptors *, **, *** and ****. For qualitative and quantitative studies, this score is the number of criteria met divided by four with scores varying from 25% (*) with one criterion met to 100% (****) with all criteria met. For mixed methods studies, overall quality is the lowest score of the study components. Criteria included quality of data sources, consideration of researcher influence and sample recruitment bias, as well as data outcome completion and dropout rates.

Classification and analysis

The selected studies were classified according to the research questions posed and divided into two tables by methodology. The tables include a synopsis and the appraisal results for each included paper. A convergent approach (Creswell et al. 2011) was predominantly employed for reporting the review findings in relation to each research question.

Results

Included studies

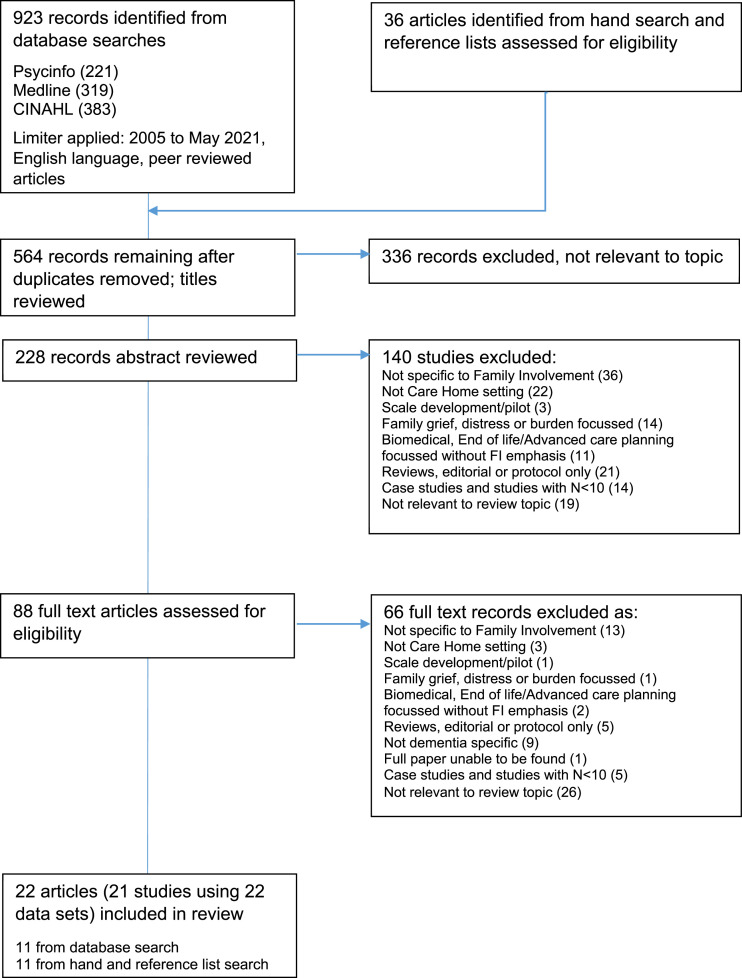

A total of 564 papers were identified from the database and hand searches. 228 remained after application of the exclusion criteria and a review of titles. Following an abstract review, a further 140 papers were excluded. 88 papers were read in full and 22 papers were retained for their relevance to the intervention and or resident outcome research questions (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of literature identification and eligibility.

Table 1 depicts studies with a quantitative or mixed methods (n = 17) design. Table 2 shows studies with qualitative designs (n = 5). Research was primarily conducted in the USA (n = 7). Other countries included Australia (n = 4), UK (n = 3), Canada (n = 2), Japan (n = 2) and New Zealand (n = 1). Three papers reporting inter-country studies were found; Italy and Netherlands (n=2, same study) and Canada, Italy and Netherlands (n = 1).

Table 1.

Papers reporting family involvement (FI) intervention or impact of FI on resident BPSD with a quantitative or mixed method study design.

| Authors | Method, approach and setting | N | Key FI domain, measures and time points | Key results | Quality rating and comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Arai et al. (2021) (Japan) RQ: 2 |

Correlational (longitudinal) Investigated how social interaction affected BPSD among residents with dementia 10 long-term care facilities 1 region |

Residents 312 | Family: frequency of visits/contact Resident: activities of daily living (ADL); cognitive function (MFIS); BPSD (NPI-Q); BPSD severity; social interaction; activity participation, resident friendships, quality of family relationships, external contact Baseline, 12 months |

Less communication with family associated with increased resident BPSD and BPSD severity. Severity stayed the same for those in frequent communication. 37% of residents had communication from family more than once per week | MMAT: **** Pos: Confounding factors and interactions accounted for, clear results reporting including effect sizes and potential biases Neg: Attrition rate |

|

Bramble et al. (2011) (Australia) RQ: 1 |

CRCT (MM) Family involvement in care (FIC) intervention 2 long-term care facilities |

Family 57 Staff 59 |

Family: knowledge (FKOD); stress (FPCR); satisfaction (FPCT) Staff: knowledge (SKOD); stress (SPCR; CSI); Attitudes toward family (AFC) Baseline, 1, 5 and 9 months |

Sig increase in both family and staff knowledge of dementia, sig decrease in family satisfaction regarding staff consideration and management effectiveness | MMAT: **** Pos: Randomised sites, blinding, power and attrition aims Neg: Small sample, follow-up attrition, no variance reported |

|

Brazil et al. (2018) (Northern Ireland, UK) RQ: 1 |

CRCT (MM) Evaluated effectiveness of an advance care planning intervention designed to assist families to participate in decision making 24 care homes |

Family 197 | Family: uncertainty in decision making (DCS); carer satisfaction (FPCS) including involvement related factors of support and communication Baseline, 6 months |

Significant reduction in family carer uncertainty in decision making and improved family carer satisfaction in nursing home care. No impact on resident hospitalisations or number of deaths found | MMAT: **** Pos: Cluster randomisation of care homes, balancing confounding variables, variance reporting Neg: Size of care homes unknown, power unclear, no blinding |

|

Chappell et al. (2014) (Canada) RQ: 2 |

Correlational (longitudinal) Examined predictors of change in social skills among residents with dementia 18 care homes 3 communities |

Family 135 Residents 149 |

Family: involvement (F-INVOLVE); involvement importance (F-IMPORT) Resident: social skills (MAS-R) Baseline (admission), 6, 12 months |

FI was not a sig predictor of changes in resident social skills over time, larger decreases in social skills associated with smaller social networks and sig fewer total visits | MMAT: **** Pos: Power, analysis reporting, longitudinal (12m), CI reporting, measures, response rate Neg: Type I error risk |

|

Dobbs et al. (2005) (USA) RQ: 2 |

Correlational (cross-sectional) Compared dementia care in residential care (RC) / assisted living (AL) to care homes 35 RC/AL, 10 care homes 4 USA states |

Family 400 Residents 400 |

Family: frequency of visits Resident: activity involvement (PAS-AD); Baseline |

Families visited at least once in the last week, family assessing activities and social involvement was related to more resident activity involvement | MMAT: *** Pos: Large sample, adjustments, variance reporting Neg: No description of family participants, non-standardised facility measures, missing data |

|

Grabowski & Mitchell (2009) (USA) RQ: 2 |

Correlational (longitudinal) Examined caregiver visit duration and resident quality end-of-life care 22 care homes 1 USA city |

Family 323 Residents 323 |

Family: oversight (visit hours per week); satisfaction with care (SWC-EOLD) Resident: health and dementia severity (BANS-S); quality of life (QUALID); quality of care (seven domains) Baseline, quarterly for 18 months/death |

Most families spent between one and 7 h visiting each week, family satisfaction with care highest in group that did not visit, quality of care sig worse for residents visited over 7 h per week | MMAT: *** Pos: Longitudinal, large sample, confound control, variance and limitation reporting Neg: One non-representative, geographical site |

|

Jablonski et al. (2005) (USA) RQ: 1 & 2 |

CRCT Family involvement in care (FIC) intervention 14 care home special care units Midwest |

Family 164 Residents 164 |

Resident: cognition (GDS); Function (FAC) Baseline, 3, 5, 7, 9 months |

Resident deterioration reversed initially though not sig different by 9 months, no sig effect on resident self-care ability, inappropriate behaviour or agitation | MMAT: ** Pos: Attrition adjustment, site randomisation, cluster effects considered Neg: Blinding, no family description, power calculation or effect size, attrition |

|

Livingston et al. (2017) (UK) RQ: 2 |

Correlational, cross-sectional Reported prevalence and determinants of agitation in residents with dementia 86 care homes |

Family 1281 Resident 1483 Staff 1701 |

Family: visits Resident: agitation (CMAI); quality of life (DEMQOL); dementia severity (CDR); Neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPI) Baseline |

Clinically significant agitation shown by 40% of residents with dementia. Agitation was not associated with number of visits by the main family carer | MMAT **** Pos: Large sample, sensitivity analyses, confound control, variance reporting, generalisability of results Neg: Possible underestimation of agitation level |

|

Mariani et al. (2018) (Italy and Netherlands) RQ: 1 and 2 |

Quasi-experimental (MM) Analysed shared decision making (SDM) on agreement of residents’ ‘life-and-care plans’ 2 care homes (IT 2; NL 1) |

Family 49 Residents 49 Staff 34 |

Family: quality of life (EuroQoL); sense of competence (SSCQ) Resident: care plans (case report Form); dementia stage (GDS); Katz Index of ADL Staff: sense of competence (SSCQ) Baseline and 6 months post intervention |

Overall, care plans showed higher level of agreement with policy recommendations post SDM. Improvements in resident and family involvement in care planning found in Italy | MMAT: **** Pos: Use of control groups in each location, clearly operationalised care plan measures, inter-rater agreement applied, group difference considered Neg: Small sample size per outcome, site control group variance, no estimate of variance reported |

|

Mbakile-Mahlanza et al. (2020) (Australia) RQ: 1 and 2 |

CRCT crossover Evaluated impact of Montessori activities implemented by family on visitation experiences of people living with dementia 9 care homes 1 Australian state |

Family 20 Residents 20 Staff 9 |

Family: quality of visits and satisfaction (5-point Likert scale); personal mastery (truncated PMS); quality of relationship with relative (5-point Likert scale) and across 4 dimensions (MSFCI); carer mood (CESDS); quality of life (Carer-QOL), frequency and length of visits Resident: affect and engagement (PGCARS and MPES) Baseline, during and post intervention |

Visits ranged from 2 to 32 per month, average 2 h per visit. Resident displays of pleasure and constructive engagement were significantly higher; anger, anxiety and passive engagement were significantly lower in Montessori versus control. Families experienced higher total visit satisfaction, and higher care-resident quality of relationship than in the control group | MMAT: **** Pos: Use of control groups and randomisation, group interaction and crossover effects analysed, effect size reported, low missing data rates Neg: Small sample size for multiple testing, no adjustment for group differences, control group components |

|

Minematsu (2006) (Japan) RQ: 2 |

Correlational (longitudinal) Investigated family visits and behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) 1 care home |

Residents 67 | Family: hours per week visiting/talking Resident: cognition (HDS-R); BPSD suppression (DBD) Baseline, 12 months |

Majority of residents visited between none and ten times per month on average, frequency of visits associated with positive change in HDS-R and DBD in residents with initial moderate HDS-R, change was lower where visit frequency was above average | MMAT: * Pos: Longitudinal (12 m), measures, description of analysis, multiple appraisers Neg: Small single site sample, minimal description of participants and data collection, missing measure reference and limitations |

|

Reinhardt et al. (2014) (USA) RQ: 1 and 2 |

RCT Palliative care conversation with follow-up calls intervention 1 care home Northeast |

Family 90 | Family: satisfaction with care (SWC-EOLD) Resident: symptom control (SM-EOLD); single item rating across seven end-of-life domains Baseline, 3, 6 months |

Families had sig increased care satisfaction and had documented sig more end-of-life care decisions in care records, no sig difference in symptom management | MMAT: *** Pos: Randomisation, blinding, control group Neg: Sample size, no power calculation, description of randomisation |

|

Robison et al. (2007) (USA) RQ: 1 and 2 |

CRCT (MM) Partner in caregiving intervention adapted for special care units (PIC-SCU) 20 care homes 1 USA state |

Family 388 Staff 384 |

Family: conflict (ICS); staff provision (SPRS); staff behaviour (SBS); staff empathy (SES); hassle (NHHS); family involvement (FIS) Resident: agitation (CMAI) Staff: Conflict (ICS); family behaviour (FBS); family empathy (FES) Baseline, 2 and 6 months |

Improvements in ease of talking with staff, and resident behaviours. Spouse/same-generation visits increased, number of programmes offered to families increased | MMAT: *** Pos: Sample size, 6m follow-up, confounding accounted for, response rates Neg: No variance reported, measure reliability |

|

Toles et al. (2018) (USA) RQ: 2 |

Correlational (cross-sectional) Compared family perceptions of quality of communication with staff and clinicians, and links with resident and family characteristics 22 care homes 1 USA state |

Family 302 Residents 302 |

Family: quality of communication including involvement and interactions, demographics Resident: Demographics Baseline |

Family decision makers rated quality of communication with NH staff higher than that with clinicians and reported poor quality end-of-life communication for both staff and clinicians. 26% of staff and 50% of clinicians did not involve family decision makers in decisions about treatment residents would want. | MMAT **** Pos sample size, diverse homes, data collection, measure, adjusted for clustering effects, non-significant result included in reporting Neg: 1 geographical state, uncontrolled potential confounds identified, no effect size reporting |

|

Van der Steen et al. (2012) Canada, Netherlands, Italy) RQ: 1 |

Quantitative retrospective study Evaluated families’ perspectives on acceptability, usefulness, preferred timing and way of obtaining a booklet on comfort care in dementia 38 care homes, (NL 28; IT 4; Canada 6) |

Family 138 | Family: Author developed 8-item scales Residents: Demographics & health problems assessed Baseline |

Most families perceived the booklet as useful. Approximately half of the families endorsed availability not through practitioners. Italian families’ ratings differed from other countries across several domains including way of obtaining, profession preferred and timing | MMAT: **** Pos: Factor adjustments made, confounding and clustering factors considered, missing data management detailed Neg: Non-standard scales, discrepancy in care home representation across locations. Retrospective design may have introduced bias (acknowledged) |

|

Verreault et al. (2018) (Canada) RQ: 1 & 2 |

Quasi-experimental study Assessed intervention to increase quality of care and quality of dying in people with advanced dementia including education provision, early and systematic communication with families 2 long-term care facilities |

Family 124 Residents 193 |

Family: quality of care (FPCS); Resident: symptom management (SM-EOLD); quality of dying (CAD-EOLD); Pain (PACSLAC) 48 h before death and 4 weeks post or within 6 months of relative death |

Sig increase in family satisfaction with care. Frequency of discussion with families and provision of information booklet higher than in care as usual. Sig increase in families’ perception of comfort assessment and symptom management | MMAT: **** Pos: Control group, validated measures, factor adjustments. confounding and clustering factors considered, full data management detailed Neg: Response rate disparity between study groups, no estimate of variance reported |

|

Zimmerman et al. (2005) (USA) RQ: 2 |

Correlational (longitudinal) Compared dementia care in residential care (RC) / assisted living (AL) to care homes 35 RC/AL, 10 care homes 4 USA states |

Family 170 Residents 170 |

Family: frequency of visits Resident: activity involvement (PAS-AD); quality of life (QOL in AD-activity); behaviour (DCM) Baseline, 6 months |

Families spent almost 7 h per week on average visiting or talking with the resident, FI was associated to higher resident quality of life | MMAT: **** Pos: Longitudinal, randomisation within site, confound adjustments, limitation reporting Neg: Missing data, no power analysis or effect size |

Note: ADL = Activities of daily living; AFC = Attitudes towards family checklist; BANS-S = Bedford Alzheimer’s Nursing Severity subscale; CAD-EOLD = Comfort Assessment in Dying; Carer-QOL = Carer’s quality of life; CDR = Clinical Dementia Rating; CESDS = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale; CMAI = Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory; CRCT = Clustered randomised controlled trial; CSI = Caregiver stress inventory; DBD = Dementia behaviour disturbance scale; DCM = Dementia Care Mapping; DCS = Decisional Conflict Scale; DEMQOL = Dementia Quality of Life Measure; EuroQOL = EQ-5D Standardised Health Outcome Measure; FAC = Functional Abilities Checklist; FBS = Family Behaviors Scale; FES = Family Empathy Scale; FIS = Family Involvement Scale; FKOD = Family Knowledge of dementia test; FPCR = Family perceptions of caregiving role; FPCS = Family perceptions of care scale; FPCT = Family perceptions of care tool; GDS = Global Deterioration Scale; HDS-R = Hasegawa Dementia Scale-Revised; ICS = Interpersonal Conflict Scale; MAS-R = Multi-Focus Assessment Scale Revised; MFIS = Mental Function Impairment Scale; MPES = Menorah Park Engagement Scale; MSFCI = Mutuality Scale of the Family Caregiving Inventory; NHHS = Nursing Home Hassles Scale; NPI = Neuropsychiatric inventory; PACSLAC = Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate; PAS-AD = Patient Activity Scale–Alzheimer’s Disease; PGCARS = Philadelphia Geriatric Center Affect Rating Scale; PMS = Pearlin mastery Scale; QUALID = Quality of Life in Late-Stage Dementia; RCT = Randomised controlled trial; RQ = Research Question; SBS = Staff Behaviors Scale; SES = Staff Empathy Scale; sig = significant; SKOD = Staff knowledge of dementia test; SM-EOLD = Symptom Management at the End-of-Life in Dementia Scale; SPCR = Staff perceptions of caregiving role; SPRS = Staff Provision to Residents Scale; SWC-EOLD = Satisfaction with Care at the End-of-Life in Dementia Scale; SSCQ = Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire.

Table 2.

Papers reporting family involvement (FI) interventions or impact of FI on resident BPSD with a qualitative design.

| Authors | Method, approach and setting | N | Key domain and time points (single unless stated) | Key results | Quality rating and comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Aveyard & Davies (2006) (UK) RQ: 1 |

Interviews, focus group Action group intervention (senses framework) 1 care home |

Family 7 Staff 18 |

Collaborative working between residents, relatives, staff and researchers | Families and staff created a shared understanding, learned to value each other, became a powerful voice for change and moved forward | MMAT: **** Pos: Longitudinal design, member checks, researcher influence, limitation reporting Neg: Small sample, atypical single site |

|

Brannelly et al. (2019) (New Zealand) RQ: 1 and 2 |

Focus group interviews Thematic analysis 1 care home |

Family 11 Staff 9 |

Impact of a new inclusive care model, live an ordinary life on care support workers and family where encouraging family contact was core aim | Families found the unit calmer, more welcoming, with improved staff–family communication. Staff reported increased confidence and positive changes in wellbeing for residents. FI resulted in improved, tailored activities for residents | MMAT: *** Pos: Longitudinal design, use of audio recording, multiple authors involved in levels of analysis and theme validation Neg: Small sample size, 1 location, no unit details, no result verification with participants, researcher influence unclear |

|

Mariani et al. (2017) (Italy & Netherlands) RQ: 1 and 2 |

Focus group interviews Descriptive with content analysis 2 care homes (IT 1; NL 1) |

Staff 19 | Barriers, facilitators and influencing factors to the implementation of a shared decision making (SDM) framework for care planning of which involving family was a central aim | Training using role play found to be useful for staff learning how to involve residents and family caregivers in optimal way. Improvements found in cooperation with families and care records. Multidisciplinary working and communication skills key to enabling FI as were family compliance factors; closeness, usual involvement with care tasks, family perceptions about need for SDM. | MMAT: **** Pos: Interview guide, multi-country, inter-rater agreement and consensus, group difference considered, well reported analysis results and participant quotes Neg: Small sample size, difference in dementia severity by location, 1 setting per location, different languages used |

|

Stirling et al. (2014) (Australia) RQ: 1 |

Interviews, focus and action groups Dementia and dying: Discussion tool 4 care homes |

Family 11 | Facilitation of staff–family communication about palliative care | Families and staff reported the tool promoted a different type of communication where families were engaged, confidence in talking about dementia trajectory and palliative care was improved and family-staff relationships were enhanced | MMAT: *** Pos: Description of tool development, stakeholder review Neg: Small sample, no result verification, researcher influence unclear |

|

Walmsley & McCormack (2017) (Australia) RQ: 2 |

Video recorded observations Phenomenological with thematic analysis 4 care homes |

Family 14 Resident 5 |

Relational social engagement (RSE) and retained awareness in people with severe dementia during interactions with family Two separate time points at families’ convenience |

Family interactions during visits resulted in retained awareness beyond assessed levels in those with severe dementia. RSE evident whether interactions were positive or negative | MMAT: *** Pos: Independent audit, separate analysis, theory links, researcher stance and bias considered Neg: Subjectivity of interpretation; speech of residents was limited, small sample size, care home details missing from results |

Note: RQ = Research Question.

Data from one study were investigated in multiple ways and reported separately (Dobbs et al. 2005; Zimmerman et al. 2005). Two separate datasets were collected within a single study and reported across more than one paper (Mariani et al. 2017, 2018). Therefore, 22 papers representing 21 studies drawn from 22 unique datasets informed the results.

Study design and quality

Quality ratings ranged from * to **** indicating a wide variation in study quality (see Table 3). The majority of the studies scored *** or above and showed many methodological strengths including use of multiple sites in their samples, clear description of analyses, management of confounding variables and application of verification procedures. The remaining two studies were of low-to-medium quality, receiving ratings between * and **. Findings remain included where other studies identified similar or corroborating results. Despite appropriate study designs for the questions posed, some studies had high attrition rates, did not appear to consider power, and involved sample size too small for analyses conducted. The quality of other studies was reduced by incomplete reporting of data collection or results.

Table 3.

Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) scores for included studies.

| Study | MMAT |

|---|---|

| Quantitative studies | |

| Minematsu (2006) | * |

| Jablonsk et al. (2005) | ** |

| Dobbs et al. (2005) a | *** |

| Grabowski & Mitchell (2009) | *** |

| Reinhardt et al. (2014) | *** |

| Arai et al. (2021) | **** |

| Chappell et al. (2014) | **** |

| Livingston et al. (2017) | **** |

| Mbakile-Mahlanza et al. (2020) | **** |

| Toles et al. (2018) | **** |

| Van der Steen et al. (2012) | **** |

| Verreault et al. (2018) | **** |

| Zimmerman et al. (2005) a | **** |

| Qualitative studies | |

| Brannelly et al. (2019) | *** |

| Stirling et al. (2014) | *** |

| Walmsley & McCormack (2017) | *** |

| Aveyard & Davies (2006) | **** |

| Mariani et al. (2017) b | **** |

| Mixed methods studies | |

| Robison et al. (2007) | *** |

| Bramble et al. (2011) c | **** |

| Brazil et al. (2018) d | **** |

| Mariani et al. (2018) b | **** |

Note: Scores vary from *(25%) one criterion met, to **** (100%) all criteria met.

aRelated studies (Dementia Care Project, USA).

bRelated studies (Shared Decision-Making framework, Italy and Netherlands).

cMixed method RCT; 2009 paper reports qualitative results.

dMixed method RCT; 2018 reports qualitative results (UK)—related specific domain.

Research questions

1. Which interventions concerning family involvement within care homes have been evaluated?

Thirteen of the 22 papers reported interventions designed to promote or improve at least one aspect of family involvement. Eleven separate interventions were described. Five of these were family focussed (Bramble et al. 2011; Brazil et al. 2018; Mbakile-Mahlanza et al. 2020; Robison et al. 2007; Stirling et al. 2014). The remainder (Aveyard & Davies, 2006; Brannelly et al. 2019; Mariani et al. 2018; Reinhardt et al. 2014; Van der Steen et al. 2012) with contexts of care planning, care quality, decision making and a new care model, considered family involvement alongside several components; in one case family involvement was one of five (Verreault et al. 2018).

Four intervention studies used the same booklet (or an adapted version) ‘Comfort Care at the end-of-life for persons with Alzheimer’s disease or other degenerative diseases of the brain’ (Arcand & Caron, 2005) as part of their family education and engagement components (Brazil et al. 2018; Jablonski et al., 2005; van der Steen et al. 2012; Verreault et al. 2018). The Jablonski et al. (2005) study achieved an MMAT score of ** and is not described here.

Robison et al. (2007) clustered randomised control trial (CRCT) found that a Partner in Caregiving intervention was effective for improving family–staff communication and increasing spousal or same generation contact. Both of these results were sustained at a 6-month follow-up; however, no significant change in staff reported conflict was found. Despite this, the care homes were also found to have increased the number of programmes offered to families.

Another CRCT by Bramble et al. (2011) found the Family Involvement in Care intervention to significantly improve family knowledge of dementia, while family satisfaction with staff consideration and management effectiveness decreased. In Mbakile-Mahlanza et al.’s (2020) crossover CRCT families experienced higher visit satisfaction when encouraged to deliver Montessori activities. Lower ratings of total quality of relationship were found for non-spousal carers. Learning how to deliver Montessori activities resulted in a negative impact on carer mood. Authors proposed family involvement include peer support, dementia education and training in Montessori activities.

A randomised control trial (RCT) with a palliative care conversation intervention (Reinhardt et al. 2014) found families added end-of-life care decisions to resident records. Family satisfaction with care increased and remained so at the 6-month follow-up. Along a similar end-of-life care theme, Verreault et al. (2018) conducted a quasi-experimental study examining a multifaceted ACP intervention. This included early and systematic communication with families and found frequency of discussions and booklet provision higher in the intervention group than in care as usual.

Mariani et al. (2018) quasi-experimental, mixed method, two-country study trialled a shared decision making (SDM) programme in long-term care. A key aim of the intervention was for staff to learn how to involve family caregivers and residents in the care planning process. After implementation, Italian care plans for people with dementia showed significant improvements in multiple factors including family participation. Care plans across both countries showed a high level of agreement with international care planning policy in which family involvement is recommended. Specifically, in qualitative analysis of focus group data, Mariani et al. (2017) reported that staff found the SDM framework facilitated both cooperation with families and clarity about staff–family role separation.

Brazil et al. (2018) instigated a paired RCT to explore the effectiveness of an ACP intervention that included a trained ACP facilitator and involved family meetings and education. Researchers found the intervention reduced family carer uncertainty in decision making concerning resident care and their perceptions of the quality of care in nursing homes was improved. When van der Steen et al. (2012) previously conducted a three-country evaluation (N = 138) of the same booklet as used by Brazil et al. (2018) most families of residents with advanced dementia rated the education tool as useful. Differences between countries were apparent across aspects of involvement such as timing of receipt of educative booklet, preferred method of access (online or direct) and content. Most families preferred to engage with the booklet at admission or soon after when care planning or a medical difficulty took place.

Stirling et al. (2014) developed and evaluated a Dementia and Dying discussion tool. They found that all care homes in their study had established processes and policies for involving families in the event that a resident’s health significantly deteriorated. However, participants advised communication and information provision could be improved. Families perceived that the tool promoted a new, positive and transparent communication style as well as improved family–staff relationships. Both family and staff confidence in talking about the course of dementia improved and overall engagement increased (Stirling et al. 2014).

The Aveyard and Davies (2006) study conducted over 2 years, evaluated an action group intervention that was based on relationship-centred care and a senses framework. Family and staff learnt to value each other and develop a powerful voice for change. Results also included improved family–staff partnerships, greater shared understanding and better communication. Families reported a sense of having a place and role in the care home, improved opportunities to support staff and a new purpose in visiting. Staff reported appreciation of support, recognition and positive feedback from families.

Similar results were reported by Brannelly et al. (2019). In ‘an ordinary life’ model with family-centred care, a lighter atmosphere and looser rules, families found the care home calmer and more welcoming. They felt cared for, perceived staff as helpful and reported improved staff–family communication. Staff’ role satisfaction increased when encouraged to speak directly with families for advice. Barriers to involvement included staff work patterns, time consuming written communication, environmental concerns (Aveyard & Davies, 2006) and limited time available to visit (Brannelly et al. 2019).

2. Does family involvement with care homes have a positive effect on residents’ BPSD and quality of life?

Of the 22 included papers, 17 involved studies that reported resident outcomes and included eight of the family involvement intervention studies outlined above. Other papers reported resident outcomes relating to; family visits or telephone calls (7), a multi-item family involvement scale (1) and quality of family communication (1). Three papers reported qualitative results. An MMAT score of ** or below was assigned to two of the papers reporting quantitative results, Jablonski et al. (2005) and Minematsu (2006).

The two CRCTs and RCT investigating different family involvement interventions, described earlier in this review, reported contrasting outcomes of BPSD for residents at their 6-month follow-up. While resident behaviours (Robison et al. 2007), engagement and affect (Mbakile-Mahlanza et al. (2020) improved, Reinhardt et al. (2014) found no significant change in symptom management. This later finding was echoed in Jablonski et al. (2005) CRCT undertaken over 9 months where no significant effect of the Family Involvement in Care intervention was found for resident self-care ability, inappropriate behaviour or agitation. Additional support for this idea comes from a large cross-sectional study by Livingston et al. (2017) where family visits were not associated with higher agitation levels in residents with dementia.

Conversely, in the ‘ordinary life’ context, Brannelly et al. (2019) reported improvements in both resident wellbeing and tailoring of activities to resident interests. Mbakile-Mahlanza et al. (2020) also found carer type was significant; higher levels of resident happiness and slightly higher levels of anger were present when offspring led sessions rather than spouses. Passive engagement was lower when a non-spouse delivered activities.

The Minematsu (2006) study found family visit frequency was associated with a reduction in BPSD for residents with moderate dementia. A positive change in BPSD was greater for residents receiving a monthly average of up to 10 visits when compared to residents receiving more than ten visits in a month. Similarly, a recent 1-year follow-up study also in Japan found BPSD of residents were likely to increase over time where there were low levels of communication with family and relatives (less than several times per year). Low communication levels were also associated with an increase in BPSD severity (Arai et al. 2021).

Two additional studies found family involvement to be related to positive quality of life (Chappell et al. 2014; Dobbs et al. 2005; Zimmerman et al. 2005) and end-of-life (Verreault et al. 2018) benefits for residents. Family involvement was associated to higher resident quality of life in activity participation though not a significant predictor of change in resident social skills. Post an ACP intervention, families and staff perceived resident quality of dying (in the last 90 days and 48 hours) higher than in care as usual. However, the family involvement factor of communication with families was only one of five components involved.

A number of studies did not directly measure resident quality of life. Quality of care is a core contributor to quality of life (Banerjee et al. 2010); therefore, relevant results are reported below. Families rated care quality higher after the ACP intervention (Verreault et al. 2018) and families of people with advanced dementia rated quality of communication about resident end-of-life concerns, higher for care home staff over clinicians (Toles et al. 2018).

Grabowski and Mitchell (2009) found no significant differences in quality of end-of-life care outcomes if residents were visited for none or between one to 7 hours per week. Residents who were visited by family for over 7 hours per week experienced significantly worse quality of care in five out of eight end-of-life care outcomes. This resonates with the Minematsu (2006) finding above and implies there may be an optimal minimum and maximum amount of time families could spend with their relatives to ensure the best outcomes.

Similarly, in the SDM intervention study, Mariani et al. (2017, 2018) found improvements in care plans about reporting resident wishes and needs regarding social, psychological and relational factors. In contrast, the presence of family prevented staff-resident discussions about intimacy. Some types and styles of family participation obstructed resident involvement in care planning (Mariani et al. 2017) and therefore limited residents’ direct influence over their own quality of life and care.

On a different note, Walmsley and McCormack (2017) qualitative study observed family–relative interactions and the speech, voice, facial expressions and body gestures exhibited by relatives. During family visits, residents with severe dementia retained awareness beyond assessed levels. Relational social engagement, the way in which families demonstrate optimal interaction was reciprocated in residents, whether positive or negative. For instance, resident BPSD including agitation, frustration and withdrawal were visible when social cues were ignored, family communication was negative or appeared to leave the resident feeling powerless. In contrast, family interactions encompassing a willingness to follow social signals, appropriate communication styles, emotional and cognitive validation, positivity and spontaneity, were met with reciprocated speech and non-speech responses from the resident. These included indicators of positive BPSD including expressions of self, demonstration of having fun, intimacy and social bonding.

Summary

Few interventions have been developed to specifically promote family involvement within care homes, following placement of a relative with dementia. Of the interventions evaluated, all were found to yield positive results including improvements in family–staff communication, family knowledge of dementia and family participation. However, the impact of family involvement and related interventions on residents’ BPSD and quality of life showed mixed results.

Discussion

What do we know now that we did not know a decade ago?

Involvement interventions

Consistent with earlier reviews (Gaugler, 2005; Petriwskyj et al. 2014) there is evidence that a Partner in Caregiving intervention adapted for dementia settings produces positive benefits for families and staff. The Family Involvement in Care intervention also appeared to translate well to care homes in a country (Australia) beyond the USA. A care model that nurtured family-centred care and family involvement interventions about advanced care or shared and end-of-life decision making, was well received and linked to improved communication and care planning.

While these findings are encouraging, they are informed by 13 studies, half of which were conducted in no more than two care homes. The studies tended to explore one context for involvement such as decision making or end-of-life care. Additionally, the variation in methodology and quality of the evidence available may have contributed to the inconsistency of the review results. With so few studies to draw on, it is difficult to make conclusions in agreement or otherwise with previous reviews.

Most interventions did not unilaterally concentrate on family involvement; granular understanding about which aspect of each intervention (or whether interactions between intervention components) is positively or negatively impacting family involvement remains largely unknown. While several countries include family participation in policy (Mariani et al. 2017) in some contexts such as care homes based in rural locations, family views remain a low priority for management and staff (see Hamiduzzaman et al. 2020). Policy change is not sufficient; interventions that specifically target promotion of effective levels of family involvement are required.

Until rich evidence about effective interventions is available, it may be necessary to look for indirect supporting evidence, in studies where fostering family involvement was not a main aim. For instance, a recent paper reporting the feasibility for use of the Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale for Dementia (IPOS-Dem) by non-nurse trained healthcare staff found, use of the measure increased family empowerment and engagement in care (Ellis-Smith et al. 2018).

Resident outcomes and family involvement

A detailed understanding of the active components of family involvement interventions for improving resident BPSD outcomes is also lacking. While communication with families is associated with slowing the progression and severity of BPSD (a motivator for involvement, see Tsai et al. 2021), some findings in this review challenge the Gaugler (2005) assertion that family involvement leads to improved quality of life and quality of care for residents. Instead, family involvement and involvement interventions may not universally benefit residents even when families and staff report increased contact, improved family–staff collaboration or satisfaction with care (Jablonski et al. 2005; Petriwskyj et al. 2014; Reinhardt et al. 2014). Similar to Kidder and Smith’s (2006) findings, high family contact frequency was linked to worse outcomes for residents and lower quality of care. There may be an optimum level of family contact, no more than ten visits per month or 7 hours per week, that enables positive BPSD and quality of care and life outcomes for residents with dementia (Grabowski & Mitchell, 2009; Minematsu, 2006).

This idea should be treated with caution; many family, organisational and resident factors influence family contact (Hayward et al., 2021) and are consequently likely to impact related resident outcomes. Quality of time spent may be more important (see Mbakile-Mahlanza et al. 2020). How these distinctions and specific components of family involvement relate to resident outcomes is not adequately evident from available studies and warrants further investigation.

The coronavirus pandemic and restriction on visitation highlighted the valuable resource that families add to care homes and provides anecdotal evidence for how the prevention of family involvement leads to negative resident outcomes. Verbeek et al. (2020) reported experiences with allowing visitors back in nursing homes after a ban. Care homes acknowledged the added value of real and personal contact between families and residents and reported a positive impact on wellbeing for all.

The small number of studies, differences in findings and mixed study quality mean a reliable conclusion cannot be drawn about the positive changes in BPSD, increased participation in activities and positive association with quality of life found in approximately half of the studies that considered resident outcomes. To emphasise this point, when reporting a cross-sectional prevalence study of a 292-care home, single-provider sample, McCreedy et al. (2018) made caveated proposals. While low family participation in care planning may impact quality of resident end-of-life care, the drivers of variation across care homes of type and level of family involvement remain unexplained. Livingston et al. (2017) also caution it may be too simplistic to consider associations between a factor (such as agitation) and a family involvement measure, particularly when the measure is restricted to one agent such as the main carer and not wider family visits.

Have Gaugler’s (2005) recommendations for research been adopted?

Gaugler’s (2005) recommendations for refinement of the evidence base relating to study methodology, inclusion of resident outcomes and relevant interventions, have been partially met. Eleven of the 22 studies had longitudinal designs. Ten studies included resident outcome measures with a family involvement measure or intervention though any links found were not always significant. On at least five occasions, family involvement was solely measured in terms of visits or contact. Staff report lower family contact frequency than families report (Cohen et al. 2014) therefore research using multiple informants is required to ensure accurate visit and contact related results.

New research would benefit from focussed exploration of the factors that influence family involvement raised in (Hayward et al., 2021) to determine which and if any, account for inter-family and inter-care home variation in family involvement. The learnings from this could then be incorporated into design of family involvement interventions. The evidence base needs studies that employ both a comprehensive measure of family involvement and resident outcomes.

Strengths and limitations

Three researchers and three databases were used for paper selection. Extensive hand searches were completed to ensure search strategy bias was minimised. Four researchers and a consensus approach were used for paper appraisal. Five of the 50 papers included in reviews used for comparison matched our included studies. To limit reporting bias, findings that corroborate and contrast in evidence to our findings have been described when alternative papers within the earlier reviews were cited.

While development continues and further improvements are recommended (Hong et al. 2018), the MMAT quality appraisal tool is an efficient, globally utilised tool with accrued evidence of content validity and reliability (Pace et al. 2012). When 75% of the papers with varied designs were appraised with an alternative tool (Kmet et al. 2004), a comparison indicated that there were no obvious differences in appraisal outcome; a paper with a low Kmet et al. (2004) score was also found to have a low MMAT rating.

UK-based research of interventions to promote family involvement following placement of a relative with dementia is under represented. Across the entire set of study designs and reporting there were weaknesses which may have inflated the risk of bias in results. Five studies used appropriate cluster randomisation designs (Bramble et al. 2011; Brazil et al. 2018; Jablonski et al. 2005; Mbakile-Mahlanza et al. 2020; Robison et al. 2007); however, the studies varied in their consideration of and control for clustering effects. Confounding by site and intra-cluster correlation effects may have impacted results (Donner & Klar, 2000). Small samples of two or fewer care homes and inconsistent variance and effect size reporting were also problematic. In qualitative studies the inclusion of an atypical, non-country representative care home and the lack of result verification processes were design disadvantages.

Non-English reporting, N < 10 and carer burden exclusion criteria may mean relevant papers were missed. These restrictions minimised bias and avoided emphasis on findings from non-representative samples. Due to overlapping timeframes, 2005 and 2006 papers were unlikely to address any of Gaugler’s (2005) recommendations for future research. Their inclusion meant the combination of Gaugler’s and this review spanned the known available literature base, from 1960 to May 2021.

Implications for clinical practice

Family involvement interventions do appear to have positive outcomes for families, staff and residents’ quality of life and end-of-life, although for residents this is not yet extensively substantiated. Different groups of residents according to their shared BPSD symptoms may respond differently to different types and frequency of family participation. Interventions that promote an optimal level of family involvement (yet to be established) warrant inclusion in policy and standardised practice to ensure resident and family-centred care. Fernandes et al. (2018) agree and following their recent exploratory study in a long-term institution in Brazil, concluded residents were willing and happy when family were involved, and intervention programmes with family as the foundation, are essential.

Three of the involvement intervention guides from studies in this review were easily accessible though one required a request to be sent to the authors. Detailed theoretical frameworks for a further intervention and the booklet resource commonly used were available while other interventions appeared to be limited to the description within an empirical paper. Care home promotion of involvement continues to be sporadic and often basic (Ampe et al. 2016); therefore, open access to detailed guides would encourage wider replication of the family involvement interventions and facilitate evidence-based best practice in care.

Future research

A new measure, developed by Fast et al. (2019) called Family Involvement Questionnaire-Long-Term Care (FIQ-LTC), has been shown to be reliable. It involves over 40 items and measures various aspects of family involvement in the lives of older adults residing in long-term care facilities. Additional studies to verify the measure’s psychometric properties are now required. Whilst the FIQ-LTC questionnaire and Reid et al. (2007) measures will enable future research to provide a more complete picture, papers in the review reported here have relied on basic descriptive and historical measures.

Future research needs to investigate links between an array of contact and involvement types such as personalisation of family–staff relationships, teamwork, family–staff discussions and resident BPSD and quality of life outcomes. This would provide more clarity about the effect the shift in emphasis to partnerships and evaluation of care (and away from foundation care) is having on residents.

People with dementia should live an ‘ordinary life’ in care homes (Brannelly et al. 2019) yet there is great variation in the ordinary life of each resident. We lack substantial evidence for how the absence of family or existing yet uninvolved family effect outcomes for residents with dementia, family and staff. Studies reporting the impact of COVID-19 visitation bans may provide valuable insights. Do staff prefer working with residents who do not have family or whose families are uninvolved? How does staff preference impact resident outcomes?

The evidence would benefit from testing and wider country replication of family involvement interventions that concentrate exclusively on family involvement and target more than one domain of family involvement. Future studies will need to use the recently developed comprehensive family involvement measures to ensure earlier measure limitations (inconsistent use of measures and reliance on a single, self-report measure) are avoided enabling credibility of any effectiveness-based conclusions.

Recently, Backhaus et al. (2020) explored the content of interventions that foster family involvement with nursing homes. Few interventions were found that seek to promote an equal family–staff partnership. Six helpful recommendations for the future development of interventions were made including to pay more attention to mutual exchange and reciprocity between family and staff members.

Families are keen to participate in research (Drake et al. 2019). There are increasing calls for relationship-centred models of care (Allison et al. 2019). It is essential to explore and resolve why there are so few interventions that promote family involvement in care homes, target removing barriers to participation and foster family involvement known and predicted to positively impact resident outcomes. Is a government level mandate required before study resources are allocated to this arena?

Conclusions

A small number of intervention studies (n = 13) with differences in methodological quality and heterogenous outcomes were identified. The Partner in Care intervention (Robison et al. 2007), an ACP intervention (Verreault et al. 2018) and a Montessori activity intervention of which family involvement was one target, were the only interventions to quantitatively demonstrate both an improvement in at least one aspect of family involvement and an improvement in resident outcomes. Evidence exists that interventions that promote family involvement yield positive results, including improved family–staff relationships and communication, improved family knowledge of dementia, better care planning, greater family participation and higher family perceived quality of care. Reliable conclusions about positive changes in resident BPSD and quality of life are unable to be drawn due to the differences across the studies in terms of components, content, method and focus.

More research is needed that involves new and enhanced interventions, specifically designed to concentrate on ways to involve families within care homes (Heap and Wolverson, 2020) and deliver positive outcomes for both families and residents living with dementia. Many of Gaugler’s (2005) recommendations have yet to be addressed and multifaceted types of family involvement need to be included in future studies. Systematic attention to involving and empowering families when developing interventions is also essential (Ampe et al. 2016).

This review and a second paper in the series (Hayward et al., 2021) provide a comprehensive view of family involvement: a proposed new definition, types, factors that influence, the process, relationship to person and family-centred care principles, measures of involvement, how family involvement is being promoted in care homes, the impact of involvement on residents wellbeing and finally recommendations for development of future interventions. This series and Backhaus et al. (2020) significantly move the dementia-specific, family involvement with care homes, evidence base forward.

Biography

Janine K Hayward is a Chartered Clinical Psychologist and Honorary Research Fellow at University College London. She has delivered psychology services in the third sector at Maggie’s Cancer centre and is currently working in private practice. Janine’s research while completing a doctorate in psychology at University College London focussed on new care home residents with dementia, specifically development and trial of a healthy adjustment programme and family involvement with care homes. More broadly, Janine is interested in research and clinical practice involving psychological therapies including Compassion Focused Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy and Mindfulness for adolescents, adults and older adults impacted by pain, cancer, chronic and severe and enduring mental illness. She has published papers and presented research relating to dementia, HIV and blood borne viruses, complex regional pain syndrome and mental health skill training for trauma ward staff.

Charlotte Gould is a Trainee Clinical Psychologist in her 2nd year at Royal Holloway University of London, currently on placement in a forensic inpatient service. Previously, she has had training experience in paediatrics, primary care mental health and pre-training worked in a specialist learning disability service. Prior to this, she worked with those experiencing a first episode of psychosis and delivered Family Intervention alongside Cognitive Behavioural Therapy approaches. Charlotte has also worked in prisons both clinically and in a research capacity. She was the lead research assistant on a study piloting a prisoner suicide screening tool developed at the University of Oxford and has published two papers in this discipline.

Emma Palluotto is a Trainee Clinical Psychologist in her 1st year at University of East London, currently working in an Improving Access to Psychological Therapies Service. Previously, she worked as an Assistant Psychologist at Great Ormond St. Hospital (GOSH) in London. Emma worked with children with rare metabolic conditions and their families, delivering interventions and neuropsychological assessments. Emma has worked with children with neurodevelopmental conditions, predominantly Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), both at Buckinghamshire Child & Adolescent Mental Health Service and the Social Communication Disorders Clinic (SCDC) at GOSH. Whilst working in SCDC, Emma carried out research into patterns in co-occurring psychiatric traits in children with ASD as part of her undergraduate BSc in Psychology, which was disseminated at the International Society for Autism Research conference, and also contributed to the Autism Families Project with the Institute of Child Health (University College London).

Emily Kitson is a Post Graduate Researcher undertaking a PhD in organisational psychology, specialising in personality change, risk-taking, wellbeing and health. She has presented her research on personality, stress and safety behaviours at the British Psychological Society DOP conference and is currently working on several papers to improve safety at work. Emily has an interest in the study of dementia and has worked at Kings College London on a clinical trial with dementia patients in private care homes. She has also been involved with the Care Home Research Network and organised one of their annual conferences. Previously, Emily has assisted with the IMAGEN project at Kings College London, which combines brain imagining, genetics and psychiatry to increase our understanding of adolescent brain development and behaviour, including impulsivity, sensitivity to rewards and emotional processing.

Emily Fisher is the Programme Manager for the CST-International research programme. She completed an MSc in Dementia: Causes, Treatments and Research (Mental Health) from UCL, and has previous experience in national dementia and ageing charities.

Aimee Spector, Professor of Old Age Clinical Psychology, is a dementia researcher at University College London and a clinical psychologist specialising in ageing and dementia. She developed Cognitive Stimulation therapy (CST) as her PhD thesis and has been involved in numerous subsequent CST research including the evaluation of maintenance CST and individual CST. She is an author on all the CST manuals, developed the CST training course and has personally trained around 3000 people in CST. She is director of the international CST centre at UCL and involved in CST research in Hong Kong, Brazil, India and Tanzania. Her research programme more broadly focuses on the development and evaluation of psychological therapies for dementia, including Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, Compassion Focused Therapy and Mindfulness. She has published over 80 academic papers, three book chapters and eight books.

Appendix

Abbreviations

- ACP

Advanced care planning

- BPSD

Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia

- CQC

Care quality commission

- CRCT

Clustered randomised control trial

- FI

Family involvement (in figures/tables, otherwise initials avoided as recommended in guidelines)

- FIQ-LTC

Family Involvement Questionnaire-Long-Term Care

- RCT

Randomised controlled trial

- SDM

Shared decision making

- MMAT

The mixed methods appraisal tool

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Geolocation information: The research was managed from London, UK.

ORCID iDs

Janine K Hayward https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8144-5690

Emily R Fisher https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8110-8405

Aimee Spector https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4448-8143

References

- Allison T. A., Balbino R. T., Covinsky K. E. (2019). Caring community and relationship centred care on an end-stage dementia special care unit. Age and Ageing, 48(5), 727-734. 10.1093/ageing/afz030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ampe S., Sevenants A., Smets T., Declercq A., Van Audenhove C. (2016). Advance care planning for nursing home residents with dementia: Policy vs. practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(3), 569-581. 10.1111/jan.12854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai A., Khaltar A., Ozaki T., Katsumata Y. (2021). Influence of social interaction on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia over 1 year among long-term care facility residents. Geriatric Nursing, 42(2), 509-516. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2020.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arcand M., Caron (2005). Comfort care at the end of life for persons with Alzheimer’s disease or other degenerative diseases of the brain. Centre de Sante et de Services Sociaux e Institut Universitaire de Geriatrie de Sherbrooke. Retrieved May 2018 from http://www.vumc.nl/afdelingen-themas/4851287/27785/5214110/HandreikingDementie.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Aveyard B., Davies S. (2006). Moving forward together: Evaluation of an action group involving staff and relatives within a nursing home for older people with dementia. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 1(2), 95-104. 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2006.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus R., Hoek L. J. M., de Vries E., van Haastregt J. C. M., Hamers J. P. H., Verbeek H. (2020). Interventions to foster family inclusion in nursing homes for people with dementia: A systematic review. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 1-17. 10.1186/s12877-020-01836-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Willis R., Graham N., Gurland B. J. (2010). The Stroud/ADI dementia quality framework: A cross-national population-level framework for assessing the quality of life impacts of services and policies for people with dementia and their family carers. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(3), 249-257. 10.1002/gps.2330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramble M., Moyle W., Shum D. (2011). A quasi-experimental design trial exploring the effect of a partnership intervention on family and staff well-being in long-term dementia care. Aging & Mental Health, 15(8), 995-1007. 10.1080/13607863.2011.583625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannelly T., Gilmour J. A., O’Reilly H., Leighton M., Woodford A. (2019). An ordinary life: People with dementia living in a residential setting. Dementia, 18(2), 757-768. 10.1177/1471301217693169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazil K., Carter G., Cardwell C., Clarke M., Hudson P., Froggatt K., McLaughlin D., Passmore P., Kernohan W. G. (2018). Effectiveness of advance care planning with family carers in dementia nursing homes: A paired cluster randomized controlled trial. Palliative Medicine, 32(3), 603-612. 10.1177/0269216317722413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Care Quality Commission (2015). Regulation 20: Duty of candour - information for providers. Retrieved May 2018 from http://www.cqc.org.uk. [Google Scholar]

- Chappell N. L., Kadlec H., Reid C. (2014). Change and predictors of change in social skills of nursing home residents with dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementiasr, 29(1), 23-31. 10.1177/1533317513505129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L. W., Zimmerman S., Reed D., Sloane P. D., Beeber A. S., Washington T., Cagle J. G., Gwyther L. P. (2014). Dementia in relation to family caregiver involvement and burden in long-term care. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 33(5), 522-540. 10.1177/0733464813505701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. W., Klassen A. C., Plano Clark V. L., Smith K. C. (2011). Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. National Institutes of Health, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. https://obssrarchive.od.nih.gov/mixed_methods_research/. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (2013). Dementia: A state of the nation report on dementia care and support in England. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/dementia-care-and-support. [Google Scholar]

- Dobbs D., Munn J., Zimmerman S., Boustani M., Williams C. S., Sloane P. D., Reed P. S. (2005). Characteristics associated with lower activity involvement in long-term care residents with dementia. The Gerontologist, 45(1), 81-86. 10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donner A., Klar N. (2000). Design and analysis of cluster randomization trials in health research. Arnold Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Drake C., Wald H. L., Eber L. B., Trojanowski J. I., Nearing K. A., Boxer R. S. (2019). Research priorities in post-acute and long-term care: Results of a stakeholder needs assessment. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 20(7), 911-915. 10.1016/j.jamda.2019.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis-Smith C., Higginson I. J., Daveson B. A., Henson L. A., Evans C. J. (2018). How can a measure improve assessment and management of symptoms and concerns for people with dementia in care homes? A mixed-methods feasibility and process evaluation of IPOS-Dem. Plos One, 13(7), e0200240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fast C. T., Houlihan D., Buchanan J. A. (2019). Developing the family involvement questionnaire-long-term care: A measure of familial involvement in the lives of residents at long-term care facilities. The Gerontologist, 59(2), e52-e65. 10.1093/geront/gnx197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes M. A., Sousa J. W. O. G., Sousa W. S. d., Gomes L. F. d. D., Almeida C. A. P. L., Damasceno C. K. C. S., Carvalho A. R. B. d., Ibiapina A. R. d. S., de Sousa Ibiapina A. R. (2018). Cuidados prestados ao idoso com Alzheimer em instituições de longa permanência. Revista de Enfermagem UFPE on line, 12(5), 1346. 10.5205/1981-8963-v12i5a230651p1346-1354-2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gaugler J. E. (2005). Family involvement in residential long-term care: A synthesis and critical review. Aging & Mental Health, 9(2), 105-118. 10.1080/13607860412331310245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabowski D. C., Mitchell S. L. (2009). Family oversight and the quality of nursing home care for residents with advanced dementia. Medical Care, 47(5), 568-574. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318195fce7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim U. H., Johansson A., Lindgren B.-M. (2014). Family caregivers’ experiences of relinquishing the care of a person with dementia to a nursing home: Insights from a meta-ethnographic study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 28(2), 215-224. 10.1111/scs.12046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamiduzzaman M., Kuot A., Greenhill J., Strivens E., Isaac V. (2020). Towards personalized care: Factors associated with the quality of life of residents with dementia in Australian rural aged care homes. Plos One, 15(5), e0233450. 10.1371/journal.pone.0233450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayward J. K., Gould C., Palluotto E., Kitson E. C., Spector A. (2021). Family involvement with care homes following placement of a relative living with dementia: A review. Ageing & Society, 1-46. 10.1017/S0144686X21000957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heap C. J., Wolverson E. (2020). Intensive Interaction and discourses of personhood: A focus group study with dementia caregivers. Dementia, 19(6), 2018-2037. 10.1177/1471301218814389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Q. N., Gonzalez-Reyes A., Pluye P. (2018). Improving the usefulness of a tool for appraising the quality of qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT). Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 24(3), 459-467. 10.1111/jep.12884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski R. A., Reed D., Maas M. L. (2005). Care intervention for older adults with Alzheimer's Disease and related dementias: Effect of family involvement on cognitive and functional outcomes in nursing homes. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 31(6), 38-48. 10.3928/0098-9134-20050601-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidder S. W., Smith D. A. (2006). Is there a conflicted surrogate syndrome affecting quality of care in nursing homes? Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 7(3), 168-172. 10.1016/j.jamda.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kmet L. M., Lee R. C., Cook L. S. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. http://www.ihe.ca/publications/. [Google Scholar]