Abstract

Objective

To investigate the financial relationships between key opinion leader (KOL) or non-KOL physicians and pharmaceutical and device companies in France.

Design

Retrospective and descriptive study.

Setting

All doctors practising in France, with a focus on 548 KOLs (board members of the professional medical associations that published guidelines in 2018–2019, identified on the associations’ websites between 2018 and 2020). Ties were collected from the ‘Transparency in Healthcare’ database.

Main outcome measures

The number and the value of gifts from 2014 to 2019, and of remunerations and contractual agreements from 2017 to 2019.

Results

KOLs represented 0.24% of the total number of physicians in France. The total value of gifts declared in the French database for all physicians amounted to €818M (US$936M, £741M). At least one gift was declared for 83% of KOLs. KOLs’ gifts represented 0.68% of the total number of gifts to physicians and 1.5% of the total value of gifts, with a mean of €3700 per capita per year.

The total value of contractual agreements declared for all physicians amounted to €125M. Contractual agreements involving the KOLs represented 0.72% of the number of contractual agreements with physicians and 2.5% of the value of the agreements, with a mean of €1900 per capita per year.

A total of €156M in remunerations were declared for all physicians. KOL remunerations represented 2.3% of the number of physician remunerations and 4.4% of the total value of the remunerations paid to physicians, with a mean of €4100 per capita per year.

Almost all professional medical associations (99%) had at least one KOL in their board with a financial tie to the industry, but the amount varied widely among the associations.

Conclusion

Financial relationships between KOLs and the industry in France are extensive. KOLs have much more financial ties than non-KOL practitioners.

Keywords: ethics (see medical ethics), health economics, quality in health care, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first time the Transparency in Healthcare database was used to analyse the links between key opinion leader (KOL) and the industry.

The authors cross-checked the nationwide database of financial ties with three databases of professional medical associations.

All medical doctors practising in France were included, with a focus on 548 KOLs defined as board members of all the professional medical associations that published clinical practice guidelines in 2018 or 2019.

The main limitation of this study arises from the quality of information provided by the French Transparency in Healthcare database.

The definition of KOLs used here is somewhat restrictive and further research is needed to better understand the links between KOLs and the industry.

Introduction

Financial ties between healthcare workers and the pharmaceutical industry may affect every aspect of medical activity, from research to clinical practice.1 Clinical trials and meta-analyses sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry are more likely to conclude that drugs are effective than non-sponsored trials.2 Industry transfers of value to physicians have been shown to be associated with more expensive, more frequent and lower quality prescriptions.3–6 Recommendations for clinical practice, which define diagnostic criteria and disease treatment, can also be influenced, since their authors often have ties with the industry.7–13

Following the example of the USA with the US Physician Payments Sunshine Act, France created the Transparency in Healthcare public database (transparence.santé.gouv.fr) in 2014.14–16 Pharmaceutical and medical device industries are required by law to disclose the value of gifts, contractual agreements and remunerations they transfer to healthcare professionals in France. In this database, ‘Gifts’ include anything that is granted without consideration, in kind or in cash, directly or indirectly, with a value greater than or equal to €10 (US$11.4) including taxes. ‘Remunerations’ represent the payment by companies for work or services with a value greater than or equal to €10. ‘Contractual agreements’ involve obligations on both sides: participation in a congress, research or clinical trial activity, training action, etc. For more convenience, this paper will gather both pharmaceutical and medical device industries under the term ‘pharmaceutical industry’.

The term ‘key opinion leaders’ (KOLs) refers to physicians who influence their peers’ medical practice, which includes but is not limited to prescribing behaviour. It was coined by sociologists who demonstrated that people were more likely to change their opinions under the influence of individuals in their network than because of the media or advertising: physician social networks hold a major influence in making physicians adopt a new drug.17 18 Pharmaceutical companies hire KOLs at different stages of the drug development process, from clinical trials to promotion.19 20 Typically, KOLs are physicians or researchers who are respected in their field and recognised for their work, such as board members of professional medical associations.20–24

Major ties between the leaders of professional medical associations and the pharmaceutical industry have recently been described in North America.11 12 In France, these financial ties had never been studied.

This paper uses the data from the Transparency in Healthcare database to describe the nature, the extent and the evolution of the financial ties of all physicians in France, with a focus on KOLs. The ties of professional medical associations were assessed by grouping the gifts, contractual agreements and remunerations received by the KOLs of each professional medical association.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective study of the financial relationships between industry and the board members of national professional medical associations that publish clinical practice guidelines. As per our protocol (registration number: osf.io/m8syh), we took into consideration the financial ties of each KOL from 2014 to 2019. KOLs were defined as board members of an association from 2018 to 2020.

Identifying professional medical associations

Professional medical associations were defined as any group of physicians who publish clinical practice guidelines in France. One author (MC) built the list of eligible associations by cross-checking three different databases: the ‘Bibliothèque Médicale AF Lemanissier’ (BMLweb),25 the ‘Catalogue et index des sites médicaux de langue française’ (CISMEF),26 and the ‘Le Parisien’ catalogue of professional medical associations.27 We included only national associations and excluded association titled as concerning a ‘rare disease’. The BML website is an academic medical library that lists month by month all the consensus statements, guidelines and recommendations published in French. MC conducted a search through it from January 2018 to December 2019 and selected all the national professional medical associations regardless of the nature of the publications they were listed for. The next step was to examine the Cismef website, which has a ‘learnt society’ section that lists French speaking professional medical associations. MC selected all the professional medical associations in France from that list. Finally, MC used the ‘Le Parisien’ database that lists French learnt societies, and selected all the professional medical associations in the ‘medical science’ section. Duplicates were then eliminated and MC examined the associations one by one to determine whether they had published guidelines in 2018 or 2019. To do so, BMLweb was used fist and then the search engine for clinical practice guidelines of the Cismef website if there was no match on BMLweb, and finally Google Scholar and the association website.

Identifying KOL

Using each professional medical association’s website, MC identified between October 2018 and May 2020 all the physicians who were board members.

KOLs were defined as members of the association’s board or governing council but not of sub-committees. KOLs were identified by name, medical specialty and city of practice via the medical association website and if missing on Google. Discrepancies and uncertainties were resolved by discussion with a second author (AB).

The Transparency in Healthcare database was downloaded on 18 May 2020 from the EurosForDocs28 website. EurosForDocs is a tool inspired by the American website DollarsForDocs. EurosForDocs aims to help browsers find and understand information in the Transparency in Healthcare database by cleaning and grouping payments by categories and beneficiaries. It also harmonises the identification of doctors using their unique identification number in the National Healthcare Professional Registry: the Répertoire Partagé des Professionnels de Santé (RPPS). The RPPS of KOLs were identified by AS in the Health-Directory database and the Transparency in Healthcare database. Uncertainties were resolved by manual inspection (MC).

Identifying and extracting payment details

By using the RPPS unique identification number, data regarding payments to the identified leaders29 were extracted using the database categories: gifts, contractual agreements and remunerations. We took the data into consideration starting from the date on which their declaration became mandatory: gifts from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2019 and contractual agreements and remunerations from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2019.

The characteristics and date on which declaration of the payments became mandatory are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Presents the three categories of financial ties and the date from which they had to be declared in the transparency in healthcare database (Transparence-Santé)

| Type of ties | Definition | Mandatory information to declare |

| Gifts | Anything that is allocated or paid without consideration by a company to a health actor, with a value greater than or equal to €10 including taxes. Available categories on the website=gifts, contribution to the cost of promotional, scientific or professional events, accommodation, hospitality, catering, transport, transport and hospitality, in-kind donations, donations, donations of money, grants, training, expenditures for services and advice, fees, failed category association, empty, other. | Identity of the parties concerned, amount, nature and date of each gift. Mandatory since the law of 2013; actual website availability in 2014. |

| Contractual agreements | Contracts involving obligations on the part of the physician and the industry. For example, participation in a congress as a speaker by the physician with payment for the lecture by the company, or participation at the presentation of a new medical device by the physician with payment for transport and accommodation by the company. The agreements concern research activities, clinical trials, participation in a scientific congress or training activities. | Identity of the parties concerned, the organiser, the name, date and place of the event, date of the agreement, its precise purpose (mandatory since the law of 2013; actual availability on the website since 2014) and the amount (mandatory since the law of 2016, actual availability on the website since 2017). If the agreements give rise to payments in gifts or remuneration, the payments can be reported in the agreements category or the gifts or remunerations categories, with a numerical link to the agreement. |

| Remunerations | Payment for work or services with a value of more than €10 including taxes. | Identity of the parties, final beneficiary, date of payment, amount if it is greater than or equal to €10 (available since 2015 but mandatory since the law of 2016, actual website availability in the remuneration section in 2017). |

The transparency in healthcare database was laid down in the ‘strengthening the safety of medicines and health products’ law of December 2011, and launched in July 2014.

Outcome measures and descriptive analyses

The primary outcome was the total number and value of gifts received by all physicians and by the identified KOLs year by year since 2014.

A secondary outcome was the number and value of payments in the two additional categories available after 2017 (ie, contractual agreements and remunerations) year by year since 2017.

The distribution of payments to individual KOLs grouped by professional medical association is also presented. Quantitative data were described using the median (IQR) rather than the mean to be less biased by extreme observations. Binary outcomes were described using n (percentage). All analyses were performed using R.30

Changes to protocol

The secondary outcome concerning contractual agreements and remunerations was not part of the protocol as these declarations were not mandatory before 2017. However, after having observed that the value of remunerations represented more than three times the yearly value of gifts, it was decided to include contractual agreements and remunerations because without them, an important part of physician-industry ties would have been missed.

We identified some outliers with implausible amounts which seemed to indicate that some of the information in the database contained errors (eg, some gifts may have been reported in cents by the company (outliers typically ending in two zeros)). It was therefore decided a posteriori to exclude amounts exceeding €100 000 (US$118 000) for a single payment. This corresponds to 35 extreme observations (34 in 2019, 1 in 2018, that is, 0.0005% of the gifts) for an amount of €32M (4% of the total and 13% of 2019).

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were involved through the French FORMINDEP association which aims to improve the independence of physicians’ medical education. FORMINDEP members (patients and physicians) kindly accepted to participate by reviewing and editing the manuscript. The French CI3P organisation (Patient and Public Partnership Innovation Center of the Faculty of Medicine of Nice) also accepted to participate in the manuscript’s revision and editing. Their comments improved the manuscript’s quality, especially the discussion.

Results

Participants

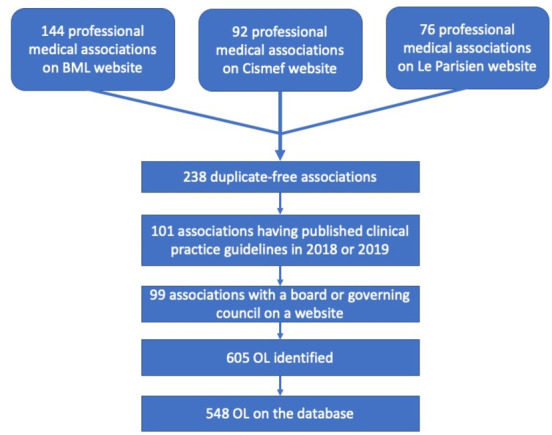

We identified 238 professional medical associations. A total of 101 of them had produced clinical practice guidelines in 2018 and/or 2019 and two of them had no website or did not describe their board on their website. We identified 605 KOLs. 548 of them were found on the Transparency in Healthcare database. The number of KOLs in each professional medical association ranged from 1 to 12, with a median of 6. 12 KOLs belonged to more than one professional medical association. The way KOLs were identified is described in the figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart representing how KOLs were identified by cross-checking three databases. BML, Bibliothèque Médicale AF Lemanissier; Cismef, Catalogue et index des sites médicaux de langue française; KOLs, key opinion leader; OL, opinion leader.

Transparency in Healthcare public database

The database reported financial ties totaling €6B (US$7.1B) over 8 years. Gifts accounted for €1.7B, contractual agreements for €1.3B and remunerations for €3B.28 Gifts, contractual agreements and remunerations are presented below starting from the year in which they were consistently declared, that is since 2014, 2017 and 2017 respectively.

Gifts (2014–2019)

When considering all physicians, 7 354 492 gifts were declared for a total value of €818M (US$936M) from 2014 to 2019. The median value of a gift was €46 (IQR=25–60, US$54).

For most KOLs (83%), at least one gift was declared from 2014 to 2019. Gifts to KOLs represented 0.68% of the total number of physician gifts and 1.5% of the total value of gifts, that is, €12.3M (US$14M). This corresponds to a mean of €3700 in gifts per KOL per year. The median value of a KOL gift was €60 (IQR=30–214, US$71).

Overall, the gifts declared for all physicians decreased in number and value from 1.3M gifts (€151M) to 923 000 gifts (€108M).

The number, value and proportion of gifts declared for KOLs decreased from 9687 gifts (0.70% of the total number of gifts to physicians)/€2.2M (1.5% of the total value of gifts to physicians) to 6044 gifts (0.65% of the total number of gifts to physicians)/€1.5M (1.4% of the total value of gifts to physicians).

The evolution year by year for each specific category of gift from 2014 to 2019 is presented in table 2.

Table 2.

Median (IQR) amount of gifts to KOL and non-KOL physicians in euros (€)

| Gift category | Physician category | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| Accommodation | All physicians | 210 (165–314) | 215 (165–341) | 215 (170–314) | 215 (164–323) | 221 (170–349) | 218 (173–328) |

| KOL | 218 (172–305) | 220 (170–330) | 218 (179–296) | 226 (176–313) | 221 (175–323) | 229 (180–344) | |

| Hospitality | All physicians | 50 (27–118) | 45 (25–60) | 46 (24–60) | 55 (30–60) | 53 (28–60) | 52 (28–60) |

| KOL | 70 (30–448) | 58 (28.2–258) | 60 (30–258) | 80.5 (40–362) | 60 (29–319) | 60 (30–329) | |

| Catering | All physicians | 40 (24–55) | 40 (24–56) | 38 (23–55) | 38 (23–56) | 38 (23–56) | 38 (24–57) |

| KOL | 40 (23–59) | 40 (23–59) | 40 (23–58) | 40 (23–58) | 40 (24–59) | 40 (24–59) | |

| Transport | All physicians | 208 (91–420) | 200 (88–398) | 191 (85–380) | 189 (79–357) | 182 (81–344) | 177 (77–332) |

| KOL | 202 (70–471) | 206 (74.2–461) | 244 (96–477) | 207 (77–445) | 198 (79.8–414) | 187 (71–395) | |

| Contributions to the cost of promotional events | All physicians | 60 (50–400) | 60 (50–404) | 60 (44–400) | 200 (55–455) | 400 (250–590) | 440 (260–650) |

| KOL | 320 (60–591) | 350 (60–600) | 390 (87–650) | 450 (186–729) | 470 (290–740) | 538 (290–796) | |

| Donations-Grants-Training | All physicians | 21 (17–30) | 23 (17–50) | 36 (23–94) | 62 (30–171) | 55 (29–171) | 55 (25–144) |

| KOL | 83 (60–275) | 68 (27.5–1578) | 96 (63.5–138) | 76 (45–192) | 155 (42–225) | 80 (42–180) | |

| Service and consulting | All physicians | 26 (22–30) | 30 (22–45) | 30 (24–50) | 30 (25–40) | 50 (25–80) | 116 (40–362) |

| KOL | 30 (24–120) | 47 (29–325) | 65 (30–600) | 32 (25–83) | 130 (74–309) | 158 (69–506) | |

| Other | All physicians | 100 (30–350) | 140 (30–496) | 100 (19–375) | 22 (16–84) | 25 (16–104) | 49 (16–220) |

| KOL | 337 (34.8–1000) | 800 (195–1188) | 700 (100–1000) | 310 (23–915) | 40 (12–153) | 79.5 (12–500) | |

| Total | All physicians | 45 (25–60) | 45 (25–60) | 45 (25–60) | 46 (25–60) | 48 (25–60) | 49 (26–60) |

| KOL | 59 (29–198) | 60 (30–224) | 60 (30–217) | 60 (30–213) | 60 (31–214) | 60 (31–210) |

KOL, key opinion leader.

Almost all (99%) associations had at least one board member for whom at least one gift had been declared since 2014. The median value of gifts declared for all the corresponding KOLs of a professional medical association was €61 000 (IQR=14 000–143 000; US$70 000) but varied widely between associations. For 1% of the associations, no gift had been declared for their KOLs. For 16%, gifts to their KOLs represented less than €1000 per year. For 39%, the value of gifts ranged between €10 000 and €50 000 and for 11%, more than €50 000 had been declared in gifts to their KOLs each year.

Contractual agreements (2017–2019)

For all physicians, 1.67 million contractual agreements were declared from 2017 to 2019 for a total of €125M (US$143M). For 1.28 million of these agreements (77%), the reported amount was null. A null amount can be explained either by a joint report in one of the two other categories (when the agreement is linked with a gift or remuneration) or by a wrong declaration.

Contractual agreements with KOLs represented 0.72% of all agreements declared for physicians and 2.5% of the value of these agreements, that is, €3M (US$3.6M). This corresponds to a mean of €1900 in declared agreements per KOL per year. For 9496 KOL agreements (79%), the reported amount was null.

Overall, contractual agreements declared for all physicians increased from €42M in 2017 to €43M in 2019.

The evolution year by year of the total value and median value of agreements is presented in table 3.

Table 3.

Number of contractual agreements with no amount, total value of agreements for which an amount could be found and number of agreements with a declared amount in the contractual agreement section, total and median (IQR) amount of remunerations to KOL and non-KOL physicians, year by year since they are consistently declared

| Payment category | Physicians category | Amount | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Total |

| Contractual agreements | All physicians | No of agreements for which the amount could not be found in the agreement section (percentage of the number of agreements) | 446 204 (79%) | 443 687 (79%) | 394 393 (72%) | 1 284 284 |

| Total value of agreements for which an amount could be found in the agreement section in € | 42 905 877 | 39 962 079 | 43 098 150 | 125 966 106 | ||

| No of agreements with a declared amount in the agreement section | 118 860 | 119 844 | 150 987 | 389 691 | ||

| KOL | No of agreements for which the amount could not be found in the agreement section (percentage of the number of agreements) | 3514 (80%) | 3319 (80%) | 2663 (76%) | 9496 | |

| Total value of agreements for which an amount could be found in the agreement section in € | 1 123 947 | 1 040 295 | 1 000 651 | 3 164 893 | ||

| No of agreements with a declared amount in the agreement section | 903 | 837 | 843 | 2583 | ||

| Remunerations | All physicians | Total amount in € | 49 152 264 | 53 142 546 | 54 254 342 | 156,549 152 |

| Median (IQR) | 300 (65–750) | 350 (65–800) | 130 (50–613) | 250 | ||

| Number of remunerations | 77 277 | 77 436 | 96 160 | 250 573 | ||

| KOL | Total amount in € | 2 355 894 | 2 346 293 | 2 172 827 | 6 875 014 | |

| Median (IQR) | 946 (527–1440) | 1000 (600–1497) | 998 (538–1375) | 1000 | ||

| No of remunerations | 1950 | 1901 | 1876 | 5718 |

KOL, key opinion leader.

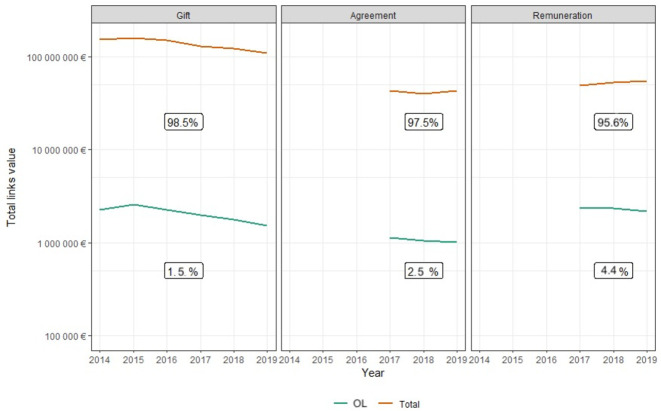

The number, the value and the proportion of contractual agreements declared for KOLs decreased each year, from 4400 agreements (0.78% of the number of agreements with physicians)/€1.1M (2.6% of the value of agreements with physicians) in 2017 to 3500 agreements (0.64% of the number of agreements with physicians)/€1M (2.3% of the value of agreements with physicians) in 2019. This evolution is depicted in figure 2.

Figure 2.

Evolution of the three kinds of financial ties for key opinion leaders (KOLs) and all physicians. The gifts declared for all physicians decreased in number and value over time; the number, the value and the proportion of gifts declared for KOLs decreased. The contractual agreements declared for all physicians increased; the number, the value and the proportion of contractual agreements declared for KOLs decreased. The remunerations declared for all physicians increased; the number, the value and the proportion of remunerations declared for KOLs decreased. OL, opinion leader.

The median value of contractual agreements declared for all the corresponding KOLs of an association was €15 900 per year and also varied widely between associations (IQR=390–35 617).

Remunerations (2017–2019)

For all physicians, 250 873 remunerations were declared totaling €156M (US$178M) from 2017 to 2019. The median amount of a remuneration was €250 (IQR 55–742) (US$296). KOLs received 2.3% of physician remunerations, that is, €6.8M (US$7.8M) or 4.4% of the total value of remunerations to physicians. Overall, KOLs received four times more remunerations than other physicians, which represents a mean of €4100 in remunerations per KOL per year.

Regarding all physicians, remunerations increased in number and total value but the median amount decreased sharply. The evolution of the total amount of remunerations is presented in table 3. Physician remunerations increased from 77 277 remunerations/€49M in 2017 to 96 160 remunerations/€54M in 2019.

The number, value and proportion of remunerations declared for KOLs decreased each year from 2017 (1900 remunerations, 2.5% of the number of remunerations to physicians, accounting for €2.3M and 4.8% of the value of remunerations to physicians) to 2019 (1800 remunerations, 1.9% of the number of remunerations to physicians, accounting for €2.1M and 4% of the value of remunerations to physicians in 2019).

The median amount of remunerations declared for all the corresponding KOLs of an association was €21 000 per year and also varied widely between associations (IQR 1012–68 977, US$25 000).

Discussion

Principal findings

From 2014 to 2019, €818M in gifts were declared for physicians in France. From 2017 to 2019, €125M in contractual agreements and €156M in remunerations were declared for physicians in France. The amount of gifts decreased while the total amount of declared contractual agreements and remunerations increased. Gifts represented the largest amount declared. 83% of the KOLs received at least one gift from the pharmaceutical industry from 2014 to 2019 for a total amount of €12.3M.

Almost every professional medical association included at least one KOL who had received one or more gifts since 2014 (99%) or 2017 (97%). Over the whole period, the median value of gifts per association was €61 000 (US$70 000). From 2017 to 2019, the median cumulative value for each professional medical association was €15 900 in contractual agreements and €21 900 in remunerations. The number and value of gifts, contractual agreements and remunerations for all the members of a single association varied widely from one association to another.

The number, value and proportion of gifts, contractual agreements and remunerations for KOLs slightly decreased over time. Remunerations represented the largest amount declared for KOLs with a median amount per capita four times higher than for other physicians. KOLs represented 0.24% of the physicians but were associated with 1.5% of the gifts, 2.4% of the contractual agreements and 4.4% of the remunerations in value. This represents €3700 in gifts, €1900 in agreements and €4100 in remunerations per capita per year. The amount for contractual agreements is probably underestimated since 79% of KOL agreement amounts were declared null in the database (see above).

Strengths and limitations

This study is exhaustive of all ties declared in the French Transparency in Healthcare database. All physicians practising in France were included since declaration of industry ties is mandatory.

However, the results may be underestimated since many amounts for contractual agreements were not available. One reason for this is that when a physician signs an agreement conferring an advantage, the amount can be declared nil as a contractual agreement or a gift, or declared as both an agreement and a gift. There is no government control at this level.

The effect of this bias is difficult to predict. Either firms did not declare the amount of thousands of contractual agreements, thus underestimating the amounts received by physicians or the amount of an agreement could have been counted twice. The entire Eurofordocs database (with all beneficiaries, without time limitation) contains 5.5 million contractual agreements, 3.3 million of which have a nil amount. 2.2 million gifts are reported to be linked to an agreement but have an invalid textual link. There are, therefore, at least 1.1 million contractual agreements with a nil amount despite the legal obligation to declare them.

Another limitation lies in the fact that the data comes from the declarations of the pharmaceutical industry itself with typos. Moreover, there may be a delay in data reporting, and remunerations may have been misclassified as it was possible to declare them as gifts or as remunerations until October 2017.

Finally, in the absence of an official definition, we chose an objective but restrictive definition of a KOL which led us to rule out many individuals with great leverage who could also have been included as KOLs.

Comparison with other studies

Our results are in line with those observed worldwide but add new data regarding the French context. A very recent US study showed that nearly three-quarters of the leaders of the 10 most influential professional medical associations in the USA had ties with the pharmaceutical industry, with wide variations in the amount of payments reported between the professional medical associations.11 Total general payments of US$24.8M (€20.8M, £18.9M) were linked to the 235 KOLs of the 10 most influential professional medical associations over 3 years. The total median general payment was US$6000 (IQR US$309–US$54 000) (€5000, £4500).

In the American study, KOLs received 10 times more per capita per year in total amount than the French KOLs, and more than 83 times more in terms of median amount.

The amounts involved in the American study seems to be much greater. This difference could be explained by societal differences but also by the fact that we included professional medical associations regardless of their size, cost or influence. The difference could also be explained by the fact that the USA has a population five times larger than France and has four times more physicians, which may represent an important return on investment. Finally, in the USA, there are more mandatory payments to report, and there are enforcement measures and effective penalties that do not exist in France.31

Implications of this study

Despite multiple calls for more distance,1 11 32–34 KOLs still have privileged relationships with the pharmaceutical industry. This phenomenon can lead to lower quality in guidelines and to a general loss of confidence in both KOLs and physicians. In recent years, several guidelines have been abrogated due to doubts about the independence of the experts involved in writing them.35–38 In turn, Chakroun et al have shown that disclosure of conflicts of interest reduces public and physician trust in KOLs.39 Experience shows that financial ties can also be instrumentalised to discredit any expert position, the link being used as an argument to call into question the scientific opinion.40–42

Our study’s finding of remaining concealments in the amounts of contractual agreements, despite the legal obligation to declare them, shows that transparency is still in progress and that both researchers and citizens do not yet have access to all the data. For us, the main area for improvement would be to make it mandatory to report the amount of gifts and remunerations conferred by a contractual agreement in the contractual agreement section. In addition, the declarations should be checked by the public authorities, which is the only way to guarantee the reliability of the information provided.

Future research might focus on the correlation between the amount of gifts and the medical specialty or the cost of the relevant diseases. Further research is needed to identify other kinds of KOLs such as the department heads of teaching hospitals, and medical university lecturers. Financial ties could be tracked over time, acting as a nudge to help chart moves towards independence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Pierre-Alain Jachiet for his proofreading of the manuscript, his help to fully understand the database and properly use EurosForDocs. Patients and public were involved through the French FORMINDEP association that aims to improve the independence of physicians’ medical education. FORMINDEP members (patients and physicians) kindly accepted to participate by reviewing and editing the manuscript. The French CI3P organisation (Patient and Public Partnership Innovation Centre of the Faculty of Medicine of Nice) also accepted to participate in the manuscript’s revision and editing. Their comments improved the manuscript’s quality, especially the discussion. The authors also thank the reviewers and the editor for valuable comments that helped to improve the manuscript and Yvonne van der Does (Office of International Scientific Visibility, Université Côte d'Azur) for proofreading. The research team would like to thank the Agence Régionale de Santé Provence Alpe Côté d’Azur for funding the Article Processing Charges.

Footnotes

Contributors: MC and AB initiated and designed the study, searched the literature, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. AS performed the analysis, contributed to the study design and interpreted results. FN contributed to the study design and interpreted the results. AB is the guarantor. All authors have critically revised the manuscript and approved the manuscript. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The Transparency in Healthcare database was downloaded on 18 May 2020 from the website EurosForDocs. Data from EurosForDocs are available on https://www.eurosfordocs.fr/data%23donn-es. Analytic code from the study is available on https://osf.io/4756p/?view_only=df16d649d87847e5aa9478960620bf81.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study does not involve human participants.

References

- 1.Moynihan R, Bero L, Hill S, et al. Pathways to independence: towards producing and using trustworthy evidence. BMJ 2019;367:l6576. 10.1136/bmj.l6576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lundh A, Lexchin J, Mintzes B, et al. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;2:MR000033. 10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brunt CS. Physician characteristics, industry transfers, and pharmaceutical prescribing: empirical evidence from Medicare and the physician payment sunshine act. Health Serv Res 2019;54:636-649. 10.1111/1475-6773.13064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hadland SE, Rivera-Aguirre A, Marshall BDL, et al. Association of pharmaceutical industry marketing of opioid products with mortality from Opioid-Related overdoses. JAMA Netw Open 2019;2:e186007. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeJong C, Aguilar T, Tseng C-W, et al. Pharmaceutical industry-sponsored meals and physician prescribing patterns for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med 2016;176:1114. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.2765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goupil B, Balusson F, Naudet F, et al. Association between gifts from pharmaceutical companies to French general practitioners and their drug prescribing patterns in 2016: retrospective study using the French transparency in healthcare and national health data system databases. BMJ 2019;367:l6015. 10.1136/bmj.l6015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schott G, Dünnweber C, Mühlbauer B, et al. Does the pharmaceutical industry influence guidelines? Dtsch Ärztebl Int 2013;110:575–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horn J, Checketts JX, Jawhar O, et al. Evaluation of industry relationships among authors of otolaryngology clinical practice guidelines. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2018;144:194–201. 10.1001/jamaoto.2017.2741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Combs TR, Scott J, Jorski A, et al. Evaluation of industry relationships among authors of clinical practice guidelines in gastroenterology. JAMA Intern Med 2018;178:1711–2. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Checketts JX, Sims MT, Vassar M. Evaluating industry payments among dermatology clinical practice guidelines authors. JAMA Dermatol 2017;153:1229–35. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.3109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moynihan R, Albarqouni L, Nangla C, et al. Financial ties between leaders of influential us professional medical associations and industry: cross sectional study. BMJ 2020;369:m1505. 10.1136/bmj.m1505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Elder K, Turner KA, Cosgrove L, et al. Reporting of financial conflicts of interest by Canadian clinical practice guideline producers: a descriptive study. CMAJ 2020;192:E617–25. 10.1503/cmaj.191737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moynihan RN, Cooke GPE, Doust JA, et al. Expanding disease definitions in guidelines and expert panel ties to industry: a cross-sectional study of common conditions in the United States. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001500. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.N° LOI. 2011-2012 Du 29 Décembre 2011 relative Au Renforcement de la Sécurité Sanitaire Du Médicament et des Produits de Santé, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Décret n° 2016-1939 du 28 décembre 2016 relatif la déclaration publique d’intérêts prévue l’article L. 1451-1 du code de la santé publique et la transparence des avantages accordés par les entreprises produisant ou commercialisant des produits finalité sanitaire et cosmétique destinés l’homme | Legifrance. Available: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/eli/decret/2016/12/28/AFSX1637582D/jo/texte [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 16.Fabbri A, Santos Ala, Mezinska S, et al. Sunshine policies and murky shadows in Europe: disclosure of pharmaceutical industry payments to health professionals in nine European countries. Int J Health Policy Manag 2018;7:504–9. 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sismondo S. How to make opinion leaders and influence people. CMAJ 2015;187:759–60. 10.1503/cmaj.150032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coleman J, Katz E. The diffusion of an innovation among physicians! 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 19.The pharma marketing glossary. pharma marketing network. Available: https://www.pharma-mkting.com/glossary/ [Accessed 19 Jul 2020].

- 20.Moynihan R. Key opinion leaders: independent experts or drug representatives in disguise? BMJ 2008;336:1402–3. 10.1136/bmj.39575.675787.651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sismondo S. Key opinion leaders and the corruption of medical knowledge: what the Sunshine Act will and won't cast light on. J Law Med Ethics 2013;41:635–43. 10.1111/jlme.12073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meffert JJ. Key opinion leaders: where they come from and how that affects the drugs you prescribe. Dermatol Ther 2009;22:262–8. 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01240.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Revue Prescrire . Leaders d’opinion : coûteux, mais rentables pour les firmes pharmaceutiques. 25, 2005: 777. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Revue Prescrire . Les leaders d’opinion, instrument marketing des firmes. 32. Rev Prescrire, 2012: 219. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nouveautés, consensus et lignes directrices - Bmlweb. Available: http://www.bmlweb.org/nouveaute.html [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 26.Société savante - CISMeF. Available: http://www.chu-rouen.fr/page/cismef-type-ressource/societe-savante [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 27.Liste de sociétés savantes scientifiques en France. Available: http://dictionnaire.sensagent.leparisien.fr/LISTE%20DE%20SOCIETES%20SAVANTES%20SCIENTIFIQUES%20EN%20FRANCE/fr-fr/ [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 28.Euros for Docs - vison par professionnel bénéficiaire. Available: https://www.eurosfordocs.fr/metabase/dashboard/2 [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 29.Traitement des données EurosforDocs. Euros for docs. Available: https://www.eurosfordocs.fr/data/ [Accessed 14 Jun 2020].

- 30.R Development Core Team . R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, 2005. Available: https://wp.unil.ch/asi/documentation/citer-r-dans-un-rapport/ [Accessed 12 Aug 2020].

- 31.Rapport : La prévention des conflits d’intérêts en matière d’expertise sanitaire – mars, 2016. Available: https://www.ccomptes.fr/sites/default/files/EzPublish/20160323-prevention-conflits-interets-en-matiere-expertise-sanitaire.pdf#page=65 [Accessed 5 Aug 2020].

- 32.Fava GA. Should the drug industry work with key opinion leaders? no. BMJ 2008;336:1405. 10.1136/bmj.39541.731493.59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sculier J-P. Conflits d’intérêt : une notion souvent (volontairement) ignorée des médecins Conflicts of interest : a concept often (voluntary) ignored by physicians. Rev Med Brux 2010;31:199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilson M. The sunshine act: commercial conflicts of interest and the limits of transparency. Open Med 2014;8:e10–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Décision n°2011.05.064/MJ du 18 mai 2011 du Collège de la Haute Autorité de Santé portant abrogation de la recommandation « Diagnostic et prise en charge de la maladie d’Alzheimer et des maladies apparentées ». Haute Autorité de Santé. Available: https://webzine.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_1056866/fr/decision-n2011-05-064/mj-du-18-mai-2011-du-college-de-la-haute-autorite-de-sante-portant-abrogation-de-la-recommandation-diagnostic-et-prise-en-charge-de-la-maladie-d-alzheimer-et-des-maladies-apparentees [Accessed 9 Nov 2020].

- 36.Dyslipidémies : face au doute sur l’impartialité de certains de ses experts, la HAS abroge sa recommandation. Haute Autorité de Santé. Available: https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_2885402/fr/dyslipidemies-face-au-doute-sur-l-impartialite-de-certains-de-ses-experts-la-has-abroge-sa-recommandation [Accessed 5 Aug 2020].

- 37.Traitement médicamenteux du diabète de type 2 : recommandation retirée le 2 mai 2011. Haute Autorité de Santé. Available: https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/c_459270/fr/traitement-medicamenteux-du-diabete-de-type-2-recommandation-retiree-le-2-mai-2011 [Accessed 5 Aug 2020].

- 38.Barbaroux A, Jedat V. Lifelong continuing education. In: Critical analysis of scientific and medical information. 163. Management of links of interest. exercer, 2020: 233–6. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chakroun R, Milhabet I. [Medical opinion leaders conflict of interests: effects of disclosures on the trust of the public and general practitioners]. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique 2011;59:233–42. 10.1016/j.respe.2010.12.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Conflits d’intérêts : Karine Lacombe répond Didier Raoult. egora.fr, 2020. Available: https://www.egora.fr/actus-pro/sante-publique/59825-conflits-d-interets-karine-lacombe-repond-a-didier-raoult [Accessed 5 Aug 2020].

- 41.Girard E. 118.000 euros de MSD, 116.000 euros de Roche : faut-il s’inquiéter des liens entre labos et conseils scientifiques ? Marianne, 2020. Available: https://www.marianne.net/societe/118000-euros-de-msd-116000-euros-de-roche-faut-il-s-inquieter-des-liens-entre-labos-et [Accessed 5 Aug 2020].

- 42.Sallet F, Lebossé V, Toulemonde M. #TransparenceCHU : comment nous avons enquêté sur les liens entre labos et médecins. leparisien.fr, 2020. Available: https://www.leparisien.fr/economie/transparencechu-comment-nous-avons-enquete-sur-les-liens-entre-labos-et-medecins-10-01-2020-8233257.php [Accessed 6 Aug 2020].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. The Transparency in Healthcare database was downloaded on 18 May 2020 from the website EurosForDocs. Data from EurosForDocs are available on https://www.eurosfordocs.fr/data%23donn-es. Analytic code from the study is available on https://osf.io/4756p/?view_only=df16d649d87847e5aa9478960620bf81.