Abstract

Background

Cocaine dependence is a major public health problem that is characterised by recidivism and a host of medical and psychosocial complications. Although effective pharmacotherapy is available for alcohol and heroin dependence, none is currently available for cocaine dependence, despite two decades of clinical trials primarily involving antidepressant, anticonvulsivant and dopaminergic medications. Extensive consideration has been given to optimal pharmacological approaches to the treatment of individuals with cocaine dependence, and both dopamine antagonists and agonists have been considered. Anticonvulsants have been candidates for use in the treatment of addiction based on the hypothesis that seizure kindling‐like mechanisms contribute to addiction.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of anticonvulsants for individuals with cocaine dependence.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group Trials Register (June 2014), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (2014, Issue 6), MEDLINE (1966 to June 2014), EMBASE (1988 to June 2014), the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (1982 to June 2014), Web of Science (1991 to June 2014) and the reference lists of eligible articles.

Selection criteria

All randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials that focus on the use of anticonvulsant medications to treat individuals with cocaine dependence.

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard methodological procedures expected by The Cochrane Collaboration.

Main results

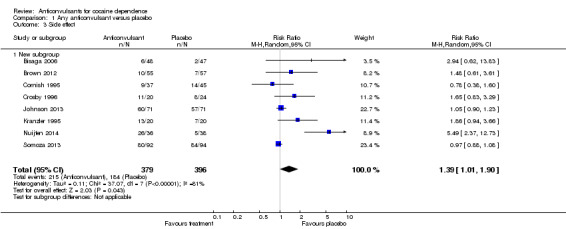

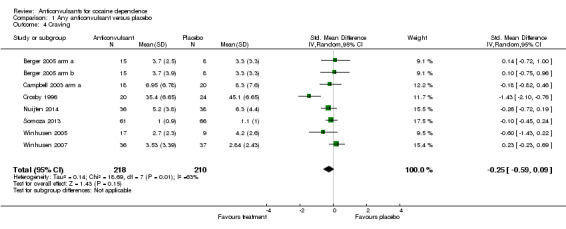

We included a total of 20 studies with 2068 participants. We studied the anticonvulsant drugs carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, phenytoin, tiagabine, topiramate and vigabatrin. All studies compared anticonvulsants versus placebo. Only one study had one arm by which the anticonvulsant was compared with the antidepressant desipramine. Upon comparison of anticonvulsant versus placebo, we found no significant differences for any of the efficacy and safety measures. Dropouts: risk ratio (RR) 0.95, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.86 to 1.05, 17 studies, 20 arms, 1695 participants, moderate quality of evidence. Use of cocaine: RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.02, nine studies, 11 arms, 867 participants, moderate quality of evidence; side effects: RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.90, eight studies, 775 participants; craving: standardised mean difference (SMD) ‐0.25, 95% CI ‐0.59 to 0.09, seven studies, eight arms, 428 participants, low quality of evidence.

Authors' conclusions

Although caution is needed when results from a limited number of small clinical trials are assessed, no current evidence supports the clinical use of anticonvulsant medications in the treatment of patients with cocaine dependence. Although the findings of new trials will improve the quality of study results, especially in relation to specific medications, anticonvulsants as a category cannot be considered first‐, second‐ or third‐line treatment for cocaine dependence.

Keywords: Humans, Anticonvulsants, Anticonvulsants/therapeutic use, Cocaine‐Related Disorders, Cocaine‐Related Disorders/drug therapy, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Anticonvulsants for cocaine dependence

Background

Cocaine is an illicit drug available as a powder for intranasal or intravenous use or smoked as crack. Short‐ and long‐term use of this drug results in the spread of infectious diseases (for example, AIDS, hepatitis, tuberculosis), crime, violence and prenatal drug exposure. Cocaine dependence is associated with medical and psychosocial complications and is a major public health problem. No proven pharmacological treatment for cocaine dependence is known. Antidepressant, anticonvulsant and dopaminergic medications have all been studied. The present review looked at the efficacy and safety of anticonvulsant drugs for treating cocaine dependence, both as a class and individually.

Study characteristics

The review authors searched scientific databases and Internet resources to identify randomised controlled trials (in which participants were allocated at random to any anticonvulsant drug or placebo or another type of drug or non‐pharmacological intervention intended to reduce,the use of cocaine). We assessed also dropout from treatment and frequency of side effects .We included people of any gender, age or ethnicity.

Key results

The review authors identified 20 studies with 2068 participants, 77% male, with a mean age of 36 years. The mean duration of the trials was 11.8 weeks (range eight to 24 weeks). All but two of the trials were conducted in the USA, all with outpatients. The anticonvulsant drugs studied were carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, phenytoin, tiagabine, topiramate and vigabatrin. All studies compared anticonvulsants versus placebo. No significant differences were found between placebo and any anticonvulsant in reducing the number of dropouts from treatment, use of cocaine, craving and severity of dependence, depression or anxiety. Side effects were slightly more frequent in the anticonvulsant groups. No current evidence supports the clinical use of anticonvulsant medications for the treatment of cocaine dependence.

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence was moderate for the outcomes dropout and use of cocaine, and was low for the outcomes side effects and craving. The major limitation of the trials was incomplete reporting of the methods used to protect against selection bias, randomly allocate participants to groups and conceal allocation. The evidence is current to June 2014.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Any anticonvulsant versus placebo for cocaine dependence.

| Any anticonvulsant versus placebo for cocaine dependence | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with cocaine dependence Settings: outpatients Intervention: any anticonvulsant versus placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Any anticonvulsant versus placebo | |||||

| Dropout Number of participants who did not complete the treatment Follow‐up: mean 11.8 weeks1 | 45 per 100 | 42 per 100 (38 to 47) | RR 0.95 (0.86 to 1.05) | 1695 (17 studies2) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate3,4 | |

| Use of cocaine (self reported or objective) Number of participants who reported the use of cocaine during treatment, and/or number of participants with urine samples positive for cocaine Follow‐up: mean 11.8 weeks1 | 77 per 100 | 71 per 100 (65 to 79) | RR 0.92 (0.84 to 1.02) | 867 (9 studies5) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate6,7 | |

| Side effect Number of participants reporting at least 1 side effect and types of side effects experienced during treatment Follow‐up: mean 11.8 weeks1 | 46 per 100 | 65 per 100 (47 to 88) | RR 1.39 (1.01 to 1.9) | 775 (8 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low8,9 | |

| Craving (BSCS) Measured by validated scales (e.g. Brief Substance Craving Scale (BSCS)) Follow‐up: mean 11.8 weeks1 | The mean craving (bscs) in the intervention groups was 0.25 standard deviations lower (0.59 lower to 0.09 higher) | 428 (7 studies11) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low11,12,13 | |||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) Working Group grades of evidence. High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Range 8 ‐ 24 weeks 2 20 treatment arms 3 In the Cornish 1995, Halikas 1997 arm a, Halikas 1997 arm b;Nuijten 2014, Umbricht 2014 studies an adequate sequence generation method was described and judged at low risk of selection bias. In the other 17 studies the method was not reported (unclear risk of bias). In five studies (Brodie 2009, Cornish 1995, Gonzalez 2007 arm a, Gonzalez 2007 arm b, Kranzler 1995, Umbricht 2014) an adequate method for allocation concealment was judged at low risk of selection bias. In all the other studies the method for allocation concealment was not reported (unclear risk of bias). Campbell 1994 arm was judged at high risk of selective reporting bias because results for drop out were not reported. 4 All the seventeen included studies were conducted in the USA 5 11 treatment arm 6 In the Cornish 1995, Halikas 1997 arm a, Halikas 1997 arm b;Nuijten 2014 studies an adequate sequence generation method was described and judged at low risk of selection bias. In the other studies the method was not reported (unclear risk of bias). In three studies (Brodie 2009, Cornish 1995, Gonzalez 2007 arm a, Gonzalez 2007 arm b) an adequate method for allocation concealment was judged at low risk of selection bias. In all the other studies the method for allocation concealment was not reported (unclear risk of bias). Nuijten 2014 were judged at high risk of performance bias and at unclear risk of detection bias All the other studies were judged at low risk of performance and detection bias. Cornish 1995, Halikas 1997 arm a, Halikas 1997 arm b, Kranzler 1995, Nuijten 2014 were judged at high risk of attrition bias. 7 I‐squared 30% 8 In the Brown 2012, Cornish 1995 and Nuijten 2014 studies an adequate sequence generation method was described and judged at low risk of selection bias. In the other studies the method was not reported (unclear risk of bias).One study was judged at high of bias ( Brown 2012) for allocation concealment. All the studies were judged at low risk of performance and detection bias. Brown 2012, Cornish 1995, Crosby 1996, Kranzler 1995, Nuijten 2014) were judged at high risk of attrition bias. All the other studies performed the analysis on the intention to treat basis or did not have withdrawn from the study. 9 I‐squared 81% 10 Eight treatment arms 11In the Nuijten 2014 studies an adequate sequence generation method was described and judged at low risk of selection bias. In the other studies the method was not reported (unclear risk of bias). In all the studies the method for allocation concealment was not reported (unclear risk of bias). Berger 2005 arm a, Berger 2005 arm b and Nuijten 2014 were judged at high risk of performance bias and at unclear risk of detection bias. Winhusen 2005 was judged at high risk both for performance and detection bias. Crosby 1996 and Nuijten 2014 were judged at high risk of attrition bias. 12I‐squared 63% 13 All the seven included studies were conducted in the USA

Background

Description of the condition

Cocaine is an alkaloid derived from the leaf of coca, which is commonly available as powder for intranasal or intravenous use, or as crack, a free‐base form that is smoked. Cocaine is a powerful stimulant that when abused typically quickly leads to dependence. Cocaine dependence is characterised by continued use of cocaine despite significant substance‐related problems.

Cocaine dependence is a major public health problem that is characterised by recidivism and a host of medical and psychosocial complications (EMCDDA 2006).

Among regular users, a broad distinction can be made between socially integrated consumers, who may be using the drug in a recreational context, and more marginalised drug users, who use cocaine, along with opioids, as part of a chronic drug problem. Regular cocaine use has been associated with cardiovascular, neurological and mental health problems, and with elevated risk of accident and dependence. Cocaine injection and use of crack cocaine are associated with the highest health risks, including transmission of infectious diseases (EMCDDA 2014).

In addition to these serious implications, cocaine use has been found to have direct negative cognitive effects on the brain, affecting tasks related to inhibition, memory, concentration, problem solving, learning, planning, attention and discrimination (Harvey 2004).

Cocaine is also implicated in acute hospital admissions, suicides and deaths (Degenhardt 2012).

Cocaine is the most commonly used illicit stimulant drug in Europe, although most users are found in only a few countries. It is estimated that about 2.2 million young adults 15 to 34 years of age (1.7% of this age group) used cocaine in the past year (EMCDDA 2014). Illicit use of cocaine is still a persistent health problem worldwide. According to recent national population surveys, between 0.4% and 9% of the adult population report that they have tried cocaine at least once (i.e. lifetime prevalence), with Italy (4.2%), Spain (8.8%) and the United Kingdom (9.0%) at the upper end of this range. In general, recent cocaine use (past 12 months) is reported by less than 2% of adults (range, 0.2% to 3.6%). In Spain and the United Kingdom, recent prevalence rates are higher than 3% (EMCDDA 2014).

The 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health found that the number of US citizens 12 years of age or older who are current users of cocaine has dropped by 44% since 2006. The US government survey on cocaine use found that in 2011, an estimated 1.4 million US citizens used cocaine ‐ down from 2.4 million in 2006. The number of people who first tried cocaine over the previous year decreased from one million in 2002 to 670,000 in 2011. In addition, the number of people who abused or were dependent on cocaine dropped from 1.7 million in 2006 to 0.8 million in 2011.

The number of people who tested positive for cocaine in the workplace dropped by 65% from 2006 to 2012, and a 44% decrease in cocaine‐related overdose deaths was reported from 2006 to 2010 (NSDUH 2011).

Although cocaine use in many South American countries has decreased or remained stable, a substantial increase in Brazil is obvious enough to be reflected in the regional prevalence rate for 2011. Cocaine use in Australia increased over the four years leading up to 2012 (UNODC 2013).

In 2012, a decrease in cocaine use among addicts seeking treatment was observed , after a peak in 2008, in Denmark, Spain and the United Kingdom, all countries reporting relatively high prevalence rates (EMCDDA 2014).

Description of the intervention

It has been estimated that at least 1.3 million people received treatment for illicit drug use in Europe during 2012.

Most treatment is provided in outpatient settings such as specialised centres, general healthcare centres such as general practitioners’ offices and low‐threshold facilities (EMCDDA 2014).

Cocaine was cited as the primary drug among 14% of all reported individuals entering specialised drug treatment in 2012 (55,000) and in 18% of those entering treatment for the first time (26,000). Differences between countries have been noted, with around 90% of all cocaine users reported by only five countries (Germany, Spain, Italy, Netherlands and United Kingdom). Together, these five countries account for just over half of the EU population (EMCDDA 2014).

Currently, no medications have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of cocaine dependence (Pani 2010).

No effective pharmacotherapy is currently available for cocaine dependence despite two decades of clinical trials involving primarily antidepressant, antipsychotic, anticonvulsant and dopaminergic medications.

Recent controlled clinical studies have highlighted some promising medications, especially glutamatergic (N‐acetylcysteine, modafinil, topiramate) and GABAergic (vigabatrin) agents, agonist replacement therapy (sustained‐release methylphenidate, d‐amphetamine) and indirect dopaminergic agents (disulfiram). Additionally, immunotherapy is a newly investigated approach (Karila 2011).

Several Cochrane systematic reviews have been published on the efficacy of antidepressants (Pani 2011), dopamine agonists (Amato 2011), psychostimulants (Castells 2010), disulfiram (Pani 2010) and antipsychotics (Amato 2007) for the treatment of cocaine dependence, but none of these provided support for the efficacy of these treatments. One published review on the efficacy of psychosocial treatment for psychostimulant dependence (Knapp 2007) showed that existing treatments have yielded modest outcomes at best, leading to the conclusion that different formats of existing treatment models should be developed and tested and new psychosocial interventions should be undertaken.

A recent study found that topiramate was more efficacious than placebo in increasing the mean weekly proportion of cocaine non‐use days and associated measures of clinical improvement among cocaine‐dependent individuals (Johnson 2013).

Nonetheless, cocaine dependence remains a disorder for which no pharmacological treatment with proved efficacy is known, although considerable advances in the neurobiology of this addiction could guide future development of medication.

How the intervention might work

The effect of cocaine seems to rely on its ability to increase the availability of monoamines (dopamine, serotonin and noradrenaline) in the brain. The dopamine increase in specific areas of the mesolimbic system with cocaine, which is shared with other drugs such as heroin, alcohol, cannabis and nicotine, has been involved in the rewarding effects of drugs and self‐administration behaviour in animals and humans (Di Chiara 1988; Drevets 1999; Drevets 2001; Volkow 2003). Anticonvulsants have been regarded as candidates for the treatment of cocaine addiction based on the hypothesis that seizure kindling‐like mechanisms contribute to addiction (Crosby 1991; Kranzler 1995). In addiction, anticonvulsants potentiate gamma‐aminobutyric acid (GABA)‐mediated inhibitory neurotransmission (Czapinski 2005; Landmark 2007). GABA neurons are part of the mesolimbic dopamine system, and activation of GABA receptors in the ventral tegmental area is known to dampen dopamine neuronal activity in the nucleus accumbens (Koob 1997). The inhibitory capacity of GABA may be effective in blocking cocaine‐induced increases in extracellular dopamine in the nucleus accumbens, which may lead to a decrease in cocaine reinforcement and reduced cocaine self administration (Campbell 1999; Kushner 1999). Some of the anticonvulsants more commonly studied for this purpose are carbamazepine, tiagabine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, topiramate, valproate, phenobarbital, phenytoin and vigabatrin.

Why it is important to do this review

In 2008, we published a Cochrane systematic review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating several anticonvulsant drugs (Minozzi 2008), with the aim of updating and completing the pre‐existing review on carbamazepine for the treatment of cocaine dependence (Lima Reisser 2000).

We concluded that no current evidence supports the clinical use of anticonvulsant medications in the treatment of cocaine dependence, and that larger randomised investigations analysing relevant outcomes (dropout, use of cocaine measured as number of individuals abstinent at the end of treatment) would have been necessary.

Since 2008, new RCTs on this topic have been published, and for this reason, an update of the systematic review is mandatory.

Objectives

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of anticonvulsants for individuals with cocaine dependence.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All RCTs and controlled clinical trials (CCTs) that focus on the use of anticonvulsant medication for cocaine dependence.

Types of participants

Cocaine‐dependent patients as diagnosed by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM‐IV‐R) or by specialists. Trials including patients with additional diagnoses of substance dependence were eligible. People younger than 18 years of age and pregnant women were excluded for the substantially different approach to clinical management that is used for these people. People with co‐morbid mental health conditions were included and were considered in the subgroup analysis.

Types of interventions

Experimental intervention

Any anticonvulsant medication alone or in combination with any psychosocial intervention.

Control interventions

Placebo.

No intervention.

Other pharmacological interventions.

Any psychosocial interventions.

When we found trials that compared different anticonvulsant medications, we performed separate subgroup analyses.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Dropouts from treatment as the number of participants who did not complete the study protocol.

Use of primary substance of abuse as the number of participants who reported use of cocaine during treatment and/or the number of participants with urine samples positive for cocaine.

Acceptability of treatment as the number of participants reporting at least one side effect and types of side effects experienced during treatment.

Secondary outcomes

Compliance as the number of participants who were adherent to the treatment protocol, or as mean and standard deviation (SD) of pills taken.

Craving as measured by validated scales (e.g. Brief Substance Craving Scale (BSCS), visual analogue scale (VAS)).

Severity of dependence as measured by validated scales (e.g. Addiction Severity Index (ASI), Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI‐S), Clinical Global Impression ‐ Observer Scale (CGI‐O)).

Psychiatric symptoms/psychological distress diagnosed using standard criteria (e.g. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) criteria, measurement by validated scales (e.g. Hamilton Depression Scale, Profile of Mood States Scale (POMSS), Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

For the original review (Minozzi 2008), we searched the following electronic databases from the earliest available date to March 2007.

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (most recent).

MEDLINE (from 1966 to March 2007).

EMBASE (from 1988 to March 2007).

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (1982 to March 2007).

For this update, we searched the following electronic databases (search date: 23 June 2014).

Cochrane Drugs and Alcohol Group (CDAG) Specialised Register* (searched June 2014).

CENTRAL (2014, Issue 6).

MEDLINE (PubMed) (March 2007 to June 2014).

EMBASE (Elsevier, EMBASE.com) (March 2007 to June 2014).

CINAHL (EBSCO Host) (March 2007 to June 2014).

Web of Science (Thomson Reuters) (March 2007 to June 2014).

Search strategies used for all databases are shown in Appendix 1, Appendix 2, Appendix 3, Appendix 4 and Appendix 5.

In addition, we searched for ongoing clinical trials and unpublished studies via Internet searches on the following sites.

www.clinicaltrials.gov (search date: 27 June 2014).

www.who.int/ictrp/en/ (World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform) (search date: 27 June 2014).

Searching other resources

We also searched the following.

Reference lists of all relevant papers to identify further studies.

Conference proceedings likely to include trials relevant to the review.

We contacted investigators to request information about unpublished or incomplete trials.

All searches included non‐English language literature, and we assessed studies with English abstracts for inclusion. When considered likely to meet inclusion criteria, we had studies translated.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (LA) inspected the search hits by reading titles and abstracts. Two review authors (LA and SM) obtained full‐text articles for all potentially relevant studies located in the search and independently assessed them for inclusion. All review authors resolved doubts by discussion. For the present update, two review authors (MC and SM) independently inspected the search hits by reading titles and abstracts. These two review authors (MC and SM) also independently inspected full‐text versions of potentially relevant studies.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (LA and SM) independently extracted data. For the present update, two review authors (MC and SM) independently extracted data. All review authors discussed disagreements. Key findings were summarised narratively in the first instance and were assessed for meta‐analysis when possible.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SM and MC) independently assessed risk of bias of the included studies. They performed risk of bias assessment for RCTs and CCTs in this review using the criteria provided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The approach recommended for assessing risk of bias in studies included in a Cochrane review involves a two‐part tool used to address seven specific domains, namely, sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and providers (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessors (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), selective outcome reporting (reporting bias) and other sources of bias. The first part of the tool involves describing what was reported to have happened in the study. The second part of the tool involves assigning a judgement related to the risk of bias for that entry in terms of low, high or unclear risk. To make these judgements, we used the criteria provided by the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions as adapted for the field of addiction. See Appendix 6 for details.

The domains of sequence generation and allocation concealment (avoidance of selection bias) were addressed in the tool by a single entry for each study.

Blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors (avoidance of performance bias and detection bias) was considered separately for objective outcomes (e.g. dropout, use of substance of abuse as measured by urinalysis, relapse at the end of follow‐up) and subjective outcomes (e.g. duration and severity of signs and symptoms of withdrawal, patient self‐reported use of substance, side effects, craving, psychiatric symptoms).

Incomplete outcome data (avoidance of attrition bias) were considered for all outcomes except for dropout from treatment, which very often is the primary outcome measured in trials on addiction.

Grading of evidence

We assessed the overall quality of evidence for the primary outcome using the GRADE system. The Grading of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group (GRADE) developed a system for grading the quality of evidence (Grade 2004; Guyatt 2008; Guyatt 2011; Shunemann 2006), which takes into account issues related not only to internal validity but also to external validity, such as directness of results. The 'Summary of findings' tables present the main findings of a review in a transparent and simple tabular format. In particular, they provide key information concerning the quality of evidence, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined and the sum of available data on the main outcomes.

The GRADE system uses the following criteria in assigning grades of evidence.

High: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect.

Moderate: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate.

Low: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate.

Very low: Any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

Grading is decreased for the following reasons.

Serious (‐1) or very serious (‐2) limitation to study quality.

Important inconsistency (‐1).

Some (‐1) or major (‐2) uncertainty about directness.

Imprecise or sparse data (‐1).

High probability of reporting bias (‐1).

Grading is increased for the following reasons.

Strong evidence of association: significant relative risk > 2 (< 0.5) based on consistent evidence from two or more observational studies, with no plausible confounders (+1).

Very strong evidence of association: significant relative risk > 5 (< 0.2) based on direct evidence with no major threats to validity (+2).

Evidence of a dose response gradient (+1).

Effect reduced by all plausible confounders (+1).

Measures of treatment effect

We analysed dichotomous outcomes by calculating the risk ratio (RR) for each trial with uncertainty in each result expressed by 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We analysed continuous outcomes by calculating the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI when studies used the same instrument in assessing the outcome. We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) when studies used different instruments. For craving score, severity of dependence (Addiction Severity Index (Drug ASI), Clinical Global Impression ‐ Observer (CGI‐O)), depression (Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM‐D)) and anxiety (Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAM‐A)), we compared the postintervention mean scores of experimental and control groups.

Unit of analysis issues

If all arms in a multi‐arm trial were to be included in the meta‐analysis, and one treatment arm was to be included in more than one of the treatment comparisons, we divided the number of events and the number of participants in that arm by the number of treatment comparisons made. This method avoids the multiple use of participants in the pooled estimate of treatment effect while retaining information from each arm of the trial. It slightly compromises the precision of the pooled estimate.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We analysed heterogeneity by using the I2 statistic and the Chi2 test. Cut‐off points included an I2 value greater than 50% and a P value for the Chi2 test less than 0.1.

Assessment of reporting biases

A funnel plot (plot of the effect estimate from each study against the sample size or the effect standard error) was not used to assess the potential for bias related to the size of the trials, which could indicate possible publication bias, because all included studies had a small sample size and yielded results that were not statistically significant.

Data synthesis

Outcomes from the individual trials were combined through meta‐analysis when possible (comparability of interventions and outcomes between trials) using a random‐effects model because some degree of heterogeneity was expected among trials.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We first compared any anticonvulsant versus placebo. We then performed subgroup analyses for single types of anticonvulsants.

Sensitivity analysis

To incorporate our assessment of risk of bias into the review process, we first plotted the intervention effect estimates stratified for risk of bias for each relevant domain. If differences in results were noted among studies at different risks of bias, we performed sensitivity analysis by excluding from the analysis studies at high risk of bias.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

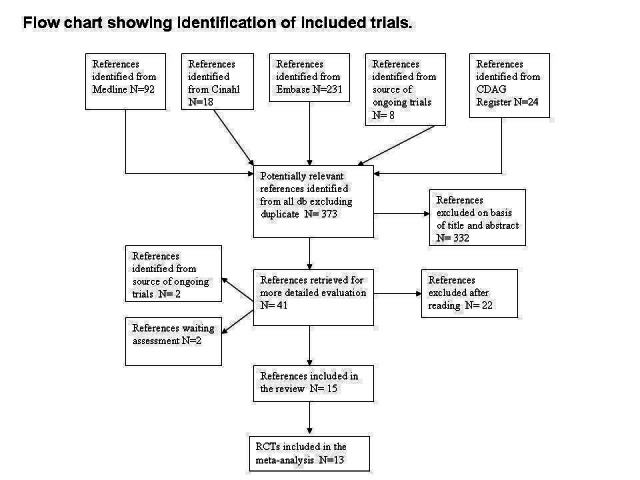

This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2008. In the first edition of this review, through bibliographic searches we identified 373 reports after removing duplicates; we excluded 332 studies on the basis of title and abstract; we retrieved 41 articles in full text for more detailed evaluation, 22 of which we excluded after reading the full text; of the remaining 19 studies, two were ongoing trials and two were unpublished studies. Therefore we excluded 22 studies and found that 15 satisfied all criteria required for inclusion in the review. See Figure 1.

1.

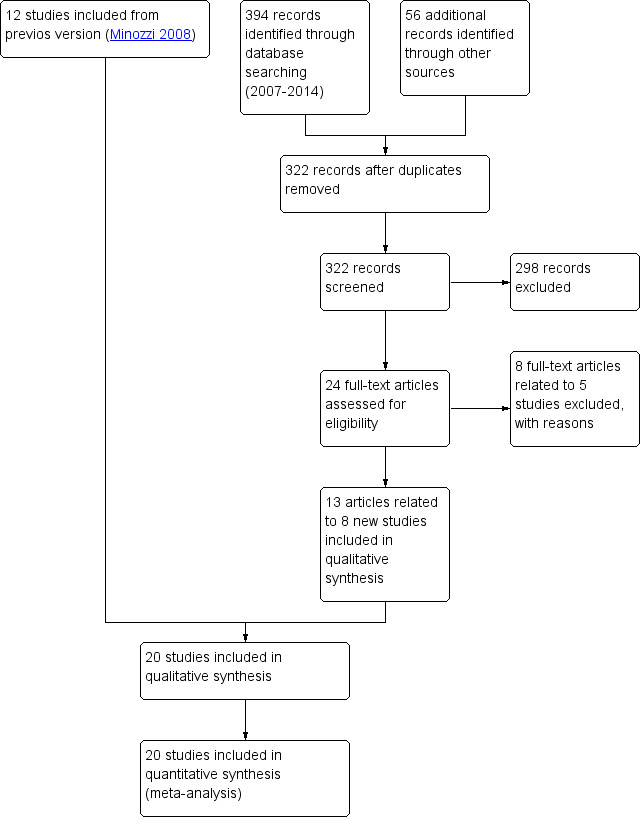

In the present update, through bibliographic searches we identified 322 records after removing duplicates; we excluded 298 studies on the basis of title and article; we retrieved 24 articles in full text for more detailed evaluation. We excluded eight articles related to five studies after reading the full text. We determined that 13 articles related to eight studies satisfied the inclusion criteria. Three were conference abstracts for which we were unable to retrieve the full publication, so we classified these as awaiting classification. We included no unpublished studies. See Figure 2.

2.

Study flow diagram of the updated version.

For substantive descriptions of studies, see Characteristics of included studies and Characteristics of excluded studies tables.

Included studies

Fifteen studies with 1066 participants met the inclusion criteria for this review in the first edition. In the update, 13 additional articles related to eight studies were further included. Moreover, for the updated version, we decided to exclude three studies that had been included in the first version: two (Reid 2005; Sofuoglu 1999) because they did not fulfil the inclusion criteria, and one (Gonzalez 2003) because it was an interim analysis of already included studies (Gonzalez 2007 arm a; Gonzalez 2007 arm b), and the same participants in two of three arms were counted in both studies. Finally, we included 20 studies with 2068 participants.

Duration of trials

The mean duration of the trials was 11.8 weeks (range, eight to 24 weeks).

Treatment regimens

The anticonvulsants utilised in the included studies were as follows.

Carbamazepine: six studies, nine arms (Campbell 1994 arm a; Campbell 1994 arm b; Campbell 2003 arm a; Campbell 2003 arm b; Cornish 1995; Halikas 1997 arm a; Halikas 1997 arm b; Kranzler 1995; Montoya 1994); mean dose 375 mg/d.

Tiagabine: three studies (Gonzalez 2007 arm a; Winhusen 2005, Winhusen 2007); mean dose 21 mg/d.

Gabapentin: three studies (Berger 2005 arm b; Bisaga 2006; Gonzalez 2007 arm b); mean dose 1933 mg/d.

Phenytoin: one study (Crosby 1996); doses of 100 mg/d.

Lamotrigine: two studies (Berger 2005 arm a; Brown 2012); dose max 150 mg/d in one study and not reported in the other.

Topiramate: five studies (Johnson 2013; Kampman 2004; Kampman 2013; Nuijten 2014; Umbricht 2014); dose max 200 mg/d in two studies, 300 mg/d in three studies.

Vigabatrin: two studies (Brodie 2009; Somoza 2013); 250 and 300 mL/d, respectively.

Setting

One study was conducted in Mexico, and one in The Netherlands; all others were conducted in the USA.

All studies were conducted in an outpatient setting.

Participants

A total of 2068 cocaine addicts according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition Revised (DSM‐IV‐R) criteria. A total of 77.4% were male; mean age was 36.2 years. All participants were actively using cocaine. Routes of administration of cocaine included 84.5% smoked crack cocaine, 10.6% intranasal and 6.6% intravenous in the 13 studies that reported this information.

Rating instruments used in these studies

Brief Substance Craving Scale (BSCS) (Somoza 1995): four studies, five arms (Berger 2005 arm a; Berger 2005 arm b; Somoza 2013; Winhusen 2005; Winhusen 2007).

Minnesota Cocaine Craving Scale (Halikas 1991): one study (Kampman 2013).

Adapted version of Obsessive Compulsive Dinking Scale for Craving (Anton 1996): one study (Nuijten 2014).

Halikas‐Crosby Drug Impairment Rating Scale for Craving (Hal‐DIRS): one study (Campbell 2003 arm a).

CSSA for Craving (Mulvaney 1999): one study (Umbricht 2014).

Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (McLellan 1992): six studies, seven arms (Berger 2005 arm a; Berger 2005 arm b; Kampman 2013; Kranzler 1995; Nuijten 2014; Winhusen 2005; Winhusen 2007).

Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI‐O) (Guy 1976): six studies, seven arms (Berger 2005 arm a; Berger 2005 arm b; Brodie 2009; Kranzler 1995; Somoza 2013; Winhusen 2005; Winhusen 2007).

Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (Hamilton 1959): four studies, five arms (Berger 2005 arm a; Berger 2005 arm b; Brodie 2009; Brown 2012; Winhusen 2005).

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (Hamilton 1967): three studies, four arms (Berger 2005 arm a; Berger 2005 arm b; Brodie 2009; Winhusen 2005).

Beck Depression Inventory (Beck 1961): two studies (Kranzler 1995; Umbricht 2014).

State Anxiety Inventory (Spielberg 1983): two studies (Kranzler 1995; Umbricht 2014).

Excluded studies

A total of 31 studies did not meet the criteria for inclusion in this review. Grounds for exclusion included study design not in the inclusion criteria: 15 studies (Ahmadi 2006, Brown 2003; Campbell 2001; Cornish 1995 b; Elkashef 2005; Halikas 1989; Johnoson 2005; Kampman 2005; Khun 1989; Leiderman 2005; Llopis Llacer 2008; Reis 2008; Salloum 2007; Vocci 2005; Zullino 2004); objectives not in the inclusion criteria: six studies (Haney 2005; Hart 2004; Hart 2007; Reid 2009; Sofuoglu 2005; Winter 2000); no useable outcome measures: three studies (Brady 2002; Halikas 1991; Hatsukami 1991); types of interventions not in the inclusion criteria: four studies (five articles) (Gorelick 1994; Mancino 2014; Mariani 2012; Reid 2005); and types of participants not in the inclusion criteria: two studies (Kemp 2009; Sofuoglu 1999). An interim analysis of already included studies was performed by one study (Gonzalez 2003).

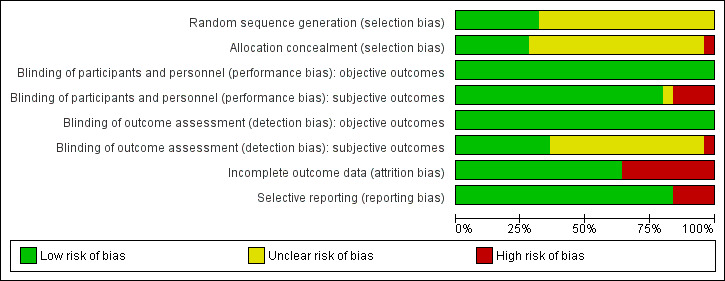

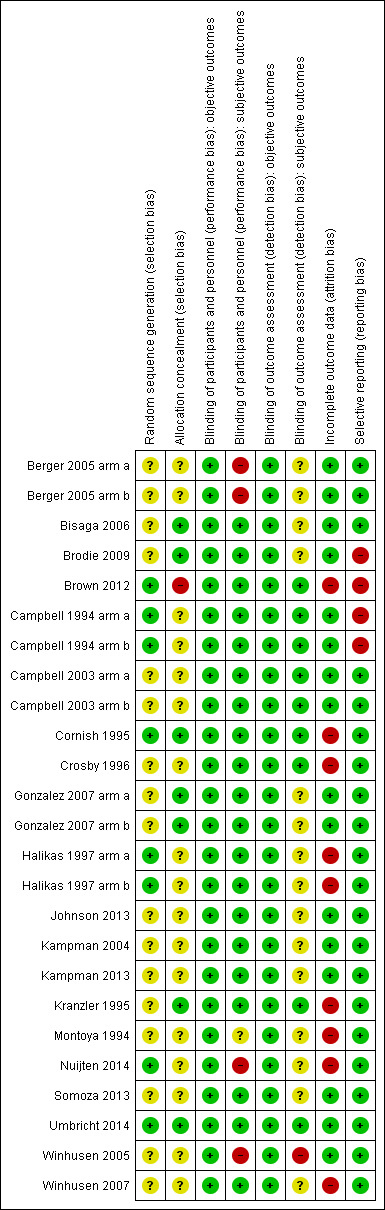

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Six studies; eight arms (Brown 2012; Campbell 1994 arm a; Campbell 1994 arm b; Cornish 1995; Halikas 1997 arm a; Halikas 1997 arm b; Nuijten 2014; Umbricht 2014) were judged at low risk of selection bias because they used an adequate sequence generation method. In all of the other studies, the method was not reported.

Allocation concealment

Six studies, seven arms (Bisaga 2006; Brodie 2009; Cornish 1995; Gonzalez 2007 arm a; Gonzalez 2007 arm b; Kranzler 1995; Umbricht 2014) were judged at low risk of selection bias because researchers used an adequate method for allocation concealment. One study was judged at high of bias (Brown 2012). In all of the other studies, investigators did not report the method used for allocation concealment.

Blinding

All but three studies (four arms) (Berger 2005 arm a; Berger 2005 arm b; Nuijten 2014; Winhusen 2005) were double‐blind controlled trials.

Objective outcomes

All studies were judged at low risk of bias.

Subjective outcomes

Performance bias

Three studies (Berger 2005 arm a; Berger 2005 arm b; Nuijten 2014 and Winhusen 2005) were judged at high risk. All other studies were judged at low risk of performance and detection bias.

Detection bias

One study (Winhusen 2005) was judged at high risk; 12 studies were judged at unclear risk of detection bias, and the remaining studies were at low risk.

Incomplete outcome data

Eight studies, nine arms (Brown 2012; Cornish 1995; Crosby 1996; Halikas 1997 arm a; Halikas 1997 arm b; Kranzler 1995; Montoya 1994; Nuijten 2014; Winhusen 2007) were judged at high risk of attrition bias. Investigators in all of the other studies performed the analysis on an intention‐to‐treat basis or did not report withdrawal from the study.

Selective reporting

Brodie 2009 was judged at high risk of selective reporting bias because results for cocaine craving, HAM‐A and HAM‐D scores or CGI severity and CGI were not reported. Study authors stated only that they observed no differences. Campbell 1994 arm a and Campbell 1994 arm b were judged at high risk of selective reporting bias because results for dropout were not reported. Study authors stated only that they observed no differences. Brown 2012 was judged at high risk of reporting bias because retention in treatment, which is one of the most relevant outcomes in the field of addiction, was not reported. For the other studies, the study protocol was not available but published reports included all expected outcomes, including those that were prespecified in the Methods section, so they were judged at low risk of reporting bias.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Comparisons

Any anticonvulsant versus placebo: 21 studies, 25 arms.

-

Single anticonvulsant versus placebo.

Subcategory 2.1: carbamazepine versus placebo: six studies, seven arms.

Subcategory 2.2: tiagabine versus placebo: three studies.

Subcategory 2.3: gabapentin versus placebo: three studies.

Subcategory 2.4: phenytoin versus placebo: one study.

Subcategory 2.5: lamotrigine versus placebo: two studies.

Subcategory 2.6: topiramate versus placebo: five studies.

Subcategory 2.7: vigabatrin versus placebo: two studies.

Anticonvulsant versus antidepressive (desipramine): two studies.

Two studies (Berger 2005 and Gonzalez 2007) included three arms, each comparing lamotrigine (Berger 2005 arm a) and gabapentin (Berger 2005 arm b) versus placebo and tiagabine (Gonzalez 2007 arm a) and gabapentin (Gonzalez 2007 arm b) versus placebo; in order to do not doublecounting the participants, we divided the number participants and events in the placebo group for comparison 2 and 1. In cases where only one event occurred in the placebo group, this could not be divided, so events and participants have been counted twice.

Two studies (Campbell 1994 and Campbell 2003) had three arms, each comparing carbamazepine versus placebo (Campbell 1994 arm a; Campbell 2003 arm a) and desipramine (Campbell 1994 arm b; Campbell 2003 arm b). The study of Halikas 1997 had three arms comparing carbamazepine 400 mg (Halikas 1997 arm a) and carbamazepine 800 mg (Halikas 1997 arm b) versus placebo; in order to do not doublecounting the participants, we divided the number participants and events in the placebo group for comparison 2 and 1.

Primary outcomes

Dropouts from treatment as number of participants who did not complete treatment

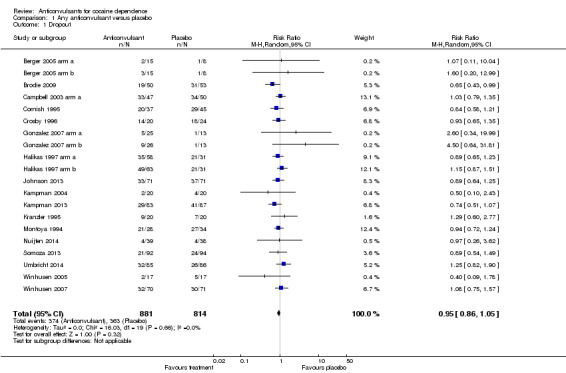

(1) Any anticonvulsants versus placebo (see Table 1) 17 studies, 20 arms (Berger 2005 arm a; Berger 2005 arm b; Brodie 2009; Campbell 2003 arm a; Cornish 1995; Crosby 1996; Gonzalez 2007 arm a; Gonzalez 2007 arm b; Halikas 1997 arm a; Halikas 1997 arm b; Johnson 2013; Kampman 2004; Kampman 2013; Kranzler 1995; Montoya 1994; Nuijten 2014; Somoza 2013; Umbricht 2014; Winhusen 2005; Winhusen 2007), 1695 participants, RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.05; no significant difference between anticonvulsant and placebo (see Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any anticonvulsant versus placebo, Outcome 1 Dropout.

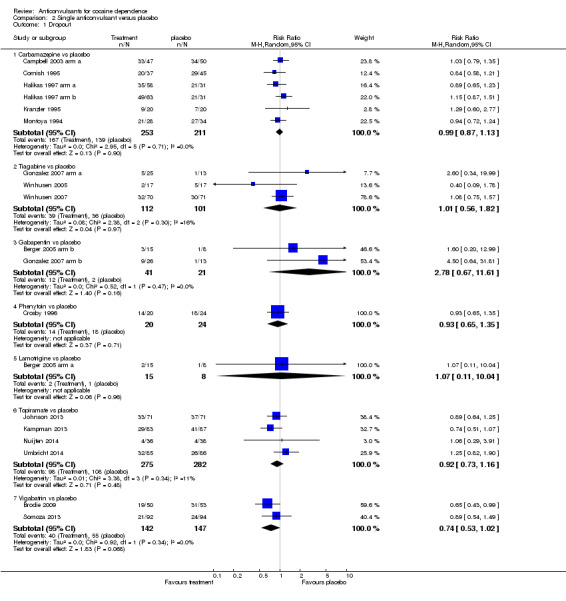

(2) Single anticonvulsants versus placebo Subcategory 2.1: carbamazepine versus placebo, five studies, six arms (Campbell 2003 arm a; Cornish 1995; Halikas 1997 arm a; Halikas 1997 arm b; Kranzler 1995; Montoya 1994), 464 participants, RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.13; no significant difference (see Analysis 2.1). Subcategory 2.2: tiagabine versus placebo, three studies (Gonzalez 2007 arm a; Winhusen 2005; Winhusen 2007), 213 participants, RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.82; no significant difference (see Analysis 2.1). Subcategory 2.3: gabapentin versus placebo, two studies (Berger 2005 arm b; Gonzalez 2007 arm b), 62 participants, RR 2.78, 95% CI 0.67 to 11.61; the result is statistically significant in favour of placebo (see Analysis 2.1). Subcategory 2.4: phenytoin versus placebo, one study (Crosby 1996), 44 participants, RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.35; no significant difference (see Analysis 2.1). Subcategory 2.5: lamotrigine versus placebo, one study (Berger 2005 arm a), 23 participants, RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.11 to 10.04; no significant difference (see Analysis 2.1). Subcategory 2.6: topiramate versus placebo, four studies (Johnson 2013; Kampman 2004; Nuijten 2014; Umbricht 2014), 557 participants, RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.16; no significant difference (see Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Single anticonvulsant versus placebo, Outcome 1 Dropout.

Subcategory 2.7: vigabatrin versus placebo, two studies (Brodie 2009; Somoza 2013), 289 participants, RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.02; a trend favours vigabatrin.

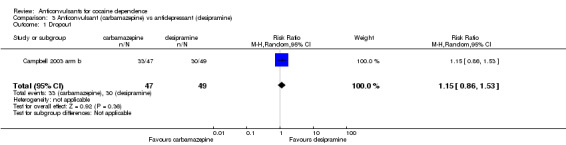

(3) Carbamazepine versus desipramine One study (Campbell 2003 arm b), 96 participants, RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.53; no significant difference.

Use of cocaine (urinalysis or self reported)

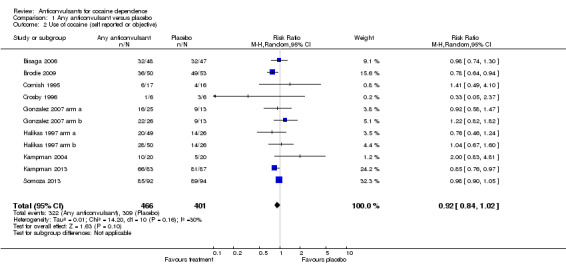

(1) Any anticonvulsants versus placebo (see Table 1) Nine studies, 11 arms (Bisaga 2006; Brodie 2009; Cornish 1995; Crosby 1996; Gonzalez 2007 arm a; Gonzalez 2007 arm b; Halikas 1997 arm a; Halikas 1997 arm b; Kampman 2004; Kampman 2013; Somoza 2013), 867 participants (see Analysis 1.2), RR 0.92, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.02; no significant difference.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any anticonvulsant versus placebo, Outcome 2 Use of cocaine (self reported or objective).

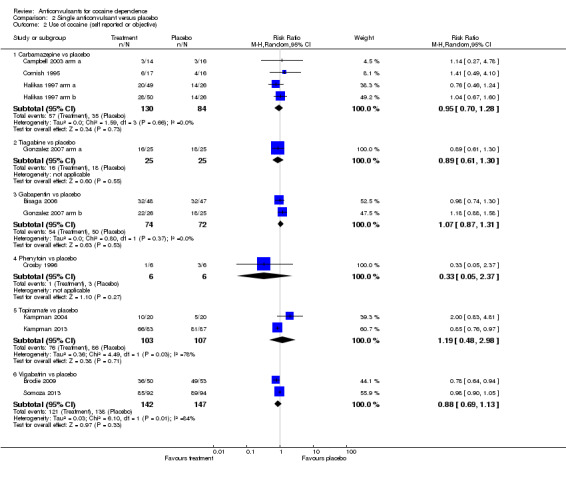

(2) Single anticonvulsants versus placebo Subcategory 2.1: carbamazepine versus placebo, three studies, four arms (Campbell 2003 arm a; Cornish 1995; Halikas 1997 arm a; Halikas 1997 arm b), 214 participants (Analysis 2.2), RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.28; no significant difference. Subcategory 2.2: tiagabine versus placebo, one study (Gonzalez 2007 arm a), 50 participants, RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.61 to 1.30; no significant difference (see Analysis 2.2). Subcategory 2.3: gabapentin versus placebo, two studies (Bisaga 2006; Gonzalez 2007 arm b), 146 participants (see Analysis 2.2), RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.31; no significant difference (see Analysis 2.2). Subcategory 2.4: phenytoin versus placebo, one study (Crosby 1996), 12 participants, RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.05 to 2.37; no significant difference (see Analysis 2.2). Subcategory 2.6: topiramate versus placebo, two studies (Kampman 2004; Kampman 2013), 210 participants, RR 1.19, 95% CI 0.48 to 2.98; no significant difference.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Single anticonvulsant versus placebo, Outcome 2 Use of cocaine (self reported or objective).

Subcategory 2.7: vigabatrin versus placebo, two studies (Brodie 2009; Somoza 2013), 289 participants, RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.13; no significant difference (see Analysis 2.2).

Any side effects

(1) Any anticonvulsants versus placebo (see Table 1) Eight studies (Bisaga 2006; Brown 2012; Cornish 1995; Crosby 1996; Johnson 2013; Kranzler 1995; Nuijten 2014; Somoza 2013), 775 participants (see Analysis 1.3), RR 1.39, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.90. Heterogeneity in the results was very high (P value < 0.00001; I2 81%). Results favoured placebo.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any anticonvulsant versus placebo, Outcome 3 Side effect.

Serious adverse events (SAEs): Seven studies reported data about SAEs. Berger 2005 arm a and Berger 2005 arm b reported three SAEs, none of which were related to the study medication. The first involved a placebo participant who accidentally shot himself in the eye with a nail gun, which required surgery, while he was in the follow‐up phase of the study. The other two SAEs occurred in participants who were taking gabapentin. Bisaga 2006 reported five SAEs, four occurring in participants randomly assigned to gabapentin. Three of the SAEs in the gabapentin group were mild and resolved without hospitalisation (chest pain, bloody stools and calf pain), and one warranted removal from the study (depression with suicidal tendencies). None of the SAEs were judged to be related to the gabapentin. In Cornish 1995, the only unexpected, serious adverse medical event that occurred was the death of one participant who was randomly assigned to carbamazepine. Montoya 1994 and Nuijten 2014 reported that no SAEs occurred. In Somoza 2013, 11 participants collectively experienced a total of 14 SAEs. The three SAEs involving placebo group participants (manic episode, hip replacement and insomnia) were determined to be unrelated to the study medication. Of 11 SAEs experienced by eight vigabatrin group participants, eight (experienced by five participants) were deemed to be unrelated or unlikely to be related to the study medication. Winhusen 2005 reported a total of three SAEs, none of which were related to the study medications. In Winhusen 2007, a total of 10 SAEs were reported for randomly assigned participants, with two participants experiencing two SAEs. Serious adverse events in the tiagabine group included hospitalisation due to suicidal ideation and hospitalisation for detoxification from alcohol and cocaine. An additional three tiagabine participants were hospitalised as the result of chest pains. Finally, one participant in the tiagabine group experienced two hospitalisations ‐ one for gallstones and one for being incoherent and agitated following use of a large amount of cocaine. One of the placebo participants was hospitalised as the result of experiencing visual hallucinations and agitation, and a second placebo participant experienced two hospitalisations, both due to chest pains, which he attributed to panic attacks. All SAEs were rated as unrelated to the study medication or with only a remote possibility of being related to the study medication.

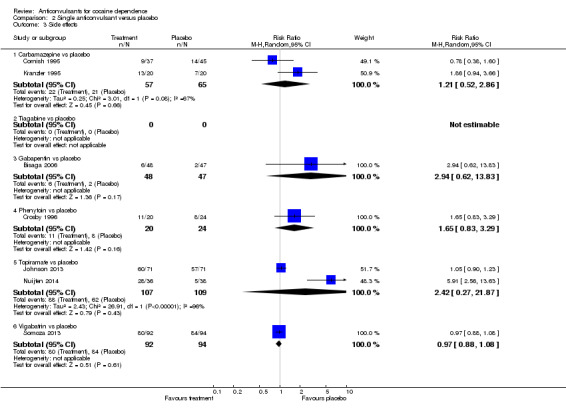

(2) Single anticonvulsants versus placebo Subcategory 2.1: carbamazepine versus placebo, two studies (Cornish 1995; Kranzler 1995), 122 participants, RR 1.21, 95% CI 0.52 to 2.86; no significant difference (see Analysis 2.3). Subcategory 2.3: gabapentin versus placebo, one study (Bisaga 2006), 95 participants, RR 2.94, 95% CI 0.62 to 13.83; the result is statistically significant in favour of placebo (see Analysis 2.3). Subcategory 2.4: phenytoin versus placebo, one study (Crosby 1996), 44 participants, RR 1.65, 95% CI 0.83 to 3.29; no significant difference (see Analysis 2.3). Subcategory 2.6: topiramate versus placebo, two studies (Johnson 2013; Nuijten 2014), 216 participants, RR 2.42, 95% CI 0.27 to 21.87; no significant difference (see Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Single anticonvulsant versus placebo, Outcome 3 Side effects.

Subcategory 2.7: vigabatrin versus placebo, one study (Somoza 2013), 186 participants, RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.08; no significant difference (see Analysis 2.3).

Sensitivity analysis

For comparison 1, we plotted the intervention effect estimates stratified for risk of bias for random sequence generation and allocation concealment. We found no difference in the results, so sensitivity analysis excluding studies with high risk of bias was not performed.

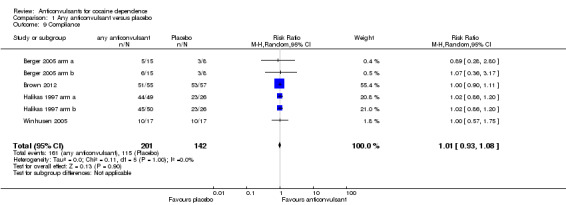

Secondary outcomes

Compliance

(1) Any anticonvulsants versus placebo

Four studies, six arms measured compliance as the number of participants fully compliant on the basis of pill counts (Berger 2005 arm a; Berger 2005 arm b; Brown 2012; Halikas 1997 arm a; Halikas 1997 arm b; Winhusen 2005), 343 participants, RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.08; no significant difference (see Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any anticonvulsant versus placebo, Outcome 9 Compliance.

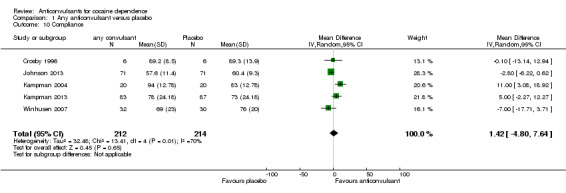

Five studies measured compliance as a mean percentage of pills taken by each group (Crosby 1996; Johnson 2013; Kampman 2004; Kampman 2013; Winhusen 2007), 426 participants, MD 1.42, 95% CI ‐4.80 to 7.64; no significant difference (see Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any anticonvulsant versus placebo, Outcome 10 Compliance.

Five studies, seven arms reported information on compliance in different and often incomplete modalities.

Bisaga 2006, Campbell 2003 arm a and Campbell 2003 arm b measured compliance by plasma level and reported only the percentage of participants compliant in the anticonvulsant group as 83%, 71% and 63%, respectively .

Gonzalez 2007 arm a and Gonzalez 2007 arm a reported “over 95% compliance with no significant difference between groups”.

Nuijten 2014 reported, “Topiramate titration (3weeks) was completed by 28 participants (77.6%). Of these, 27 participants were prescribed the maximum dose of 200mg/day and one patient received 150 mg/day due to adverse events. Twenty‐two patients (61.1%) received Topiramate treatment for at least 6 weeks, nine patients (25.0%) for at least 9 weeks and five patients (13.9%) completed at least 11 weeks. The mean dose of Topiramate in the 28 ‘titration completers’ was 189 mg/day (sd=32.1)”. Information on adherence was not reported for the placebo group.

Somoza 2013 reported, “Based on pill counts, 55.4% of participants were more than 90% compliant, and 66.2% of participants were more than 70% compliant, with no statistically significant difference between the treatment groups”.

The remaining studies did not assess this outcome.

Craving

(1) Any anticonvulsants versus placebo (see Table 1) Seven studies, eight arms (Berger 2005 arm a; Berger 2005 arm b; Campbell 2003 arm a; Crosby 1996; Nuijten 2014; Somoza 2013; Winhusen 2005; Winhusen 2007), 428 participants, SMD ‐0.25, 95% CI ‐0.59 to 0.09; no significant difference (see Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any anticonvulsant versus placebo, Outcome 4 Craving.

Severity of dependence (Addiction Severity Index)

(1) Any anticonvulsants versus placebo

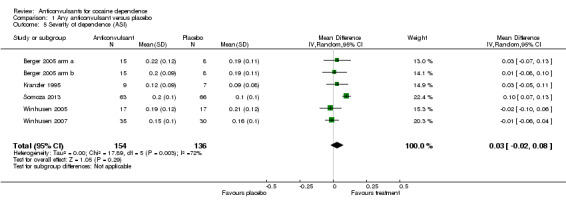

Five studies, six arms (Berger 2005 arm a; Berger 2005 arm b; Kranzler 1995; Somoza 2013; Winhusen 2005, Winhusen 2007), 290 participants, MD 0.03, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.08; no significant difference (see Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any anticonvulsant versus placebo, Outcome 5 Severity of dependence (ASI).

Severity of dependence (Clinical Global Impression Scale ‐ Observer)

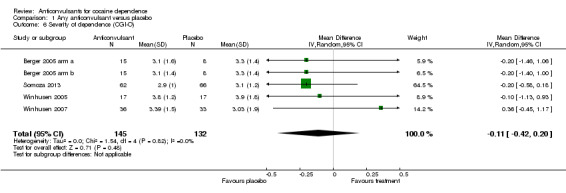

(1) Any anticonvulsants versus placebo Four studies, five arms (Berger 2005 arm a; Berger 2005 arm b; Somoza 2013; Winhusen 2005; Winhusen 2007), 277 participants, MD ‐0.11, 95% CI ‐0.42 to 0.20; no significant difference (see Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any anticonvulsant versus placebo, Outcome 6 Severity of dependence (CGI‐O).

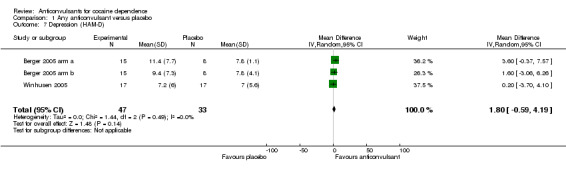

Depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale)

(1) Any anticonvulsants versus placebo Two studies, three arms (Berger 2005 arm a; Berger 2005 arm b; Winhusen 2005), 80 participants, MD 1.80, 95% CI ‐0.59 to 4.19; no significant difference (see Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any anticonvulsant versus placebo, Outcome 7 Depression (HAM‐D).

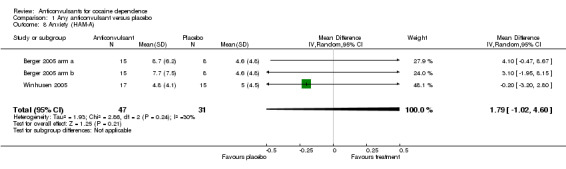

Anxiety (Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale)

(1) Any anticonvulsants versus placebo Two studies, three arms (Berger 2005 arm a; Berger 2005 arm b; Winhusen 2005), 78 participants, MD 1.79, 95% CI ‐1.02 to 4.60; no significant difference (see Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any anticonvulsant versus placebo, Outcome 8 Anxiety (HAM‐A).

Discussion

Summary of main results

We found 20 studies including 2068 participants comparing anticonvulsants versus placebo for the treatment of cocaine dependence. The anticonvulsants assessed were carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, phenytoin, tiagabine, topiramate and vigabatrin.

Overall, no significant differences were found for any of the primary and secondary outcomes when any anticonvulsants were compared with placebo. Also in the subgroup analyses comparing a single anticonvulsant versus placebo, no differences were found in any of the primary or secondary outcomes.

Results on side effects are few because only 8/21 (38%) studies reported data on side effects in a useable way. Moreover heterogeneity is high between studies in the frequencies of any side effects; this suggests that side effects could have been defined differently within studies, and that probably studies for which the frequency of side effects was very low reported only the most significant or important ones, whereas studies with high frequency reported any and low relevant side effects.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

All but two of the 21 included studies were conducted in the USA. This could limit the generalisability of the results because health effects of various substances of abuse seem to be strongly dependent on social context, and the location at which studies were conducted could act as an effect modifier in the estimation of efficacy of treatment. Moreover among the included participants, 84.5% smoked crack cocaine, and only 10.6% used the intranasal route in the 13 studies that reported this information. These frequencies do not reflect the real prevalence of the different formulations of cocaine and route of administration: In European countries, crack cocaine represents around 13% of individuals seeking treatment (ranging from 1% in Italy and 36% in England) (EMCDDA 2012). This further limits on the generalisability of the results.

Quality of the evidence

Only 7/21 (30%) studies have been judged as having low risk of selection bias; all other studies were judged as having unclear risk of selection bias because the information was not reported. All but three studies (86%) were double‐blind. A total of 8/21 (38%) studies were judged as having high risk of attrition bias. All other studies performed the analysis on an intention‐to‐treat basis or reported no withdrawals from the study. Two studies were judged to be at high risk of selective reporting because they did not report results for dropout, and because they did not report raw data for craving or psychiatric outcomes but only stated that no differences were noted.

However, with subgroup analysis, as in the case of single classes of anticonvulsants, single types of medications and confounder/moderator evaluation, as well as with comparisons versus other medications, findings of the review were limited by the small number of studies included in the meta‐analysis of study outcomes. Therefore the precision of the calculated effects is low. Finally, the great heterogeneity of the scales used in the primary studies and the way in which results were reported often made a cumulative analysis impossible.

Potential biases in the review process

We found no unpublished studies despite efforts to contact all first authors of the included studies and to perform a search of conference proceedings. We did not use funnel plots to assess the possibility of publication bias because in this review, only small negative studies have been included, and in this situation, this method is not sensitive.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Both preclinical and clinical studies have investigated the potential involvement of this class of medication in the treatment of substance use disorders; clinical trials specifically designed for evaluation of anticonvulsants and their efficacy and safety in cocaine dependence have been performed. Among the reviews published after our previous Cochrane review on the topic, two (Cohen 2014; Shinn 2010) were exclusively interested in the efficacy of topiramate. They adopted a narrative approach and reported results of two clinical trials and one clinical trial, respectively. A third review (Alvarez 2010) was characterised by a meta‐analytical approach (Alvarez 2010). It included 15 randomised, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled clinical trials involving 1236 participants and evaluated seven anticonvulsant drugs. According to this review, treatments do not show improvement in subject retention compared with placebo, and the number of cocaine‐positive urine samples was close to reaching statistical significance (95% CI 0.85 to 1.06) compared with placebo.

Our review, besides applying Cochrane methodology, includes 20 studies with 2068 participants, and it extends evaluations to a wider range of primary and secondary outcomes. On the whole, the results that we obtained show no evidence of differences between anticonvulsants and placebo. However, it has to be considered that anticonvulsants constitute a really heterogeneous group. Besides their anticonvulsant action, they have different pharmacological profiles and indications. This would suggest the need for a more detailed evaluation of singular medications. Unfortunately, for most outcomes, meta‐analyses carried out on specific anticonvulsants included only one or two studies and few participants.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Although caution is needed when results from a limited number of clinical trials are assessed, at present no current evidence supports the clinical use of anticonvulsants, as a category, in the treatment of cocaine dependence. In terms of specific medications, the insufficiency of evidence may leave to clinicians the alternative of balancing possible benefits against potential adverse effects of treatment.

Implications for research.

To answer the urgent demand of clinicians, patients, families and the community as a whole for adequate treatment for cocaine dependence, we must improve primary research in the field of addiction to make the best possible use of a single study. Researchers must design larger randomised investigations to analyse relevant outcomes (dropout, use of cocaine measured as number of participants abstinent at the end of treatment). The fact that this review has found that the anticonvulsants investigated are not efficacious for cocaine dependence should not discourage researchers from carrying out new clinical trials on anticonvulsants with different pharmacological characteristics. Some of these studies are ongoing and will be added to this review as soon as their results become available. Besides increasing the numbers of trials and participants, these studies (five on topiramate, two on vigabatrin, two on tiagabine, one on levetiracetam), when available, will contribute to evaluation of the efficacy of specific medications.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 8 June 2015 | Amended | Reference correction |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2007 Review first published: Issue 2, 2008

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 11 March 2015 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | The previous version of this review has been withdrawn because of conflicts of interest of one review author; the review team has been changed, and 5 new studies added |

| 11 March 2015 | New search has been performed | A new search was conducted |

| 6 September 2011 | Amended | Plain language summary was amended |

| 21 March 2008 | Amended | Review was converted to new review format |

| 7 February 2008 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendments were made |

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Zuzana Mitrova for helping with search strategies and for facilitating the editorial process, and Professor Robert Ali, who is the contact editor for this review.

Appendices

Appendix 1. CENTRAL search

MeSH descriptor: [Cocaine‐Related Disorders] explode all trees

(cocaine* or crack):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

#1 or #2

(anticonvulsant* or carbamazepine or clorazepate or clobazam or clonazepam or chlordiazepoxide or divalproex or ethosuximide or ethosuximide or ethotoin or felbamate or fosphenytoin or gabapentin or lignocaine or lamotrigine or levetiracetam or lidocaine or hydantoins or levetiracetam or methsuximide or oxcarbazepine or paraldehyde or phenacemide or phenytoin or pregabalin or primidone or succinimide or tiagabine or topiramate or valproate or vigabatrin or zonisamide):ti,ab,kw (Word variations have been searched)

ACTH:ti,ab

#4 or #5

#3 and #6

Appendix 2. MEDLINE search strategy

Cocaine‐Related Disorders [Mesh]

((cocaine*[tiab]) AND (abuse*[tiab] OR addict*[tiab] OR dependen*[tiab]))

#1 OR #2

"Anticonvulsants"[Mesh]

anticonvulsant* [tiab]

ACTH[tiab]

carbamazepine OR clorazepate OR clobazam OR clonazepam OR chlordiazepoxide OR divalproex OR ethosuximide OR ethosuximide OR ethotoin OR felbamate OR fosphenytoin OR gabapentin OR lignocaine OR lamotrigine OR levetiracetam OR lidocaine OR hydantoins OR levetiracetam OR methsuximide OR oxcarbazepine OR paraldehyde OR phenacemide OR phenytoin OR pregabalin OR primidone OR succinimide OR tiagabine OR topiramate OR valproate OR vigabatrin OR zonisamide

#4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7

randomized controlled trial [pt])

controlled clinical trial [pt])

randomized [tiab])

drug therapy [sh])

randomly [tiab])

trial [tiab])

groups [tiab])

placebo [tiab]

#9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16

animals [mh] NOT humans [mh]

#17 NOT #18

#3 AND #8 AND #19

Appendix 3. EMBASE search strategy

'cocaine dependence'/exp

(cocaine:ab,ti AND (abus*:ab,ti OR dependen*:ab,ti OR disorder*:ab,ti OR addict*:ab,ti))

'cocaine'/exp OR 'cocaine derivative'/exp AND

#1 OR #2 OR #3

'anticonvulsive agent'/exp OR

acth:ab,ti OR anticonvulsant*:ab,ti OR carbamazepine:ab,ti OR clorazepate:ab,ti OR clobazam:ab,ti OR clonazepam:ab,ti OR chlordiazepoxide:ab,ti OR divalproex:ab,ti OR ethosuximide:ab,ti OR ethotoin:ab,ti OR felbamate:ab,ti OR fosphenytoin:ab,ti OR gabapentin:ab,ti OR lignocaine:ab,ti OR lamotrigine:ab,ti OR lidocaine:ab,ti OR hydantoins:ab,ti OR levetiracetam:ab,ti OR methsuximide:ab,ti OR oxcarbazepine:ab,ti OR paraldehyde:ab,ti OR phenacemide:ab,ti OR phenytoin:ab,ti OR pregabalin:ab,ti OR primidone:ab,ti OR succinimide:ab,ti OR tiagabine:ab,ti OR topiramate:ab,ti OR valproate:ab,ti OR vigabatrin:ab,ti OR zonisamide:ab,ti AND

#5 OR #6

'randomized controlled trial'/exp

'crossover procedure'/exp

'double blind procedure'/exp

'single blind procedure'/exp

'controlled clinical trial'/exp

'clinical trial'/exp

placebo:ab,ti OR 'double blind':ab,ti OR 'single blind':ab,ti OR assign*:ab,ti OR allocat*:ab,ti OR volunteer*:ab,ti OR random*:ab,ti OR factorial*:ab,ti OR crossover:ab,ti OR (cross:ab,ti AND over:ab,ti)

#8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14

#4 AND #7 AND #15

Appendix 4. CINAHL search strategy

(MH "Substance Use Disorders+")

TX((cocaine) AND (abuse* OR dependen* OR addict* OR disorder*))

TI cocaine* OR AB cocaine* OR MH cocaine

S1 OR S2 OR S3

(MH "Anticonvulsants+")

TI (carbamazepine OR clorazepate OR clobazam OR clonazepam OR chlordiazepoxide OR divalproex OR ethosuximide OR ethosuximide OR ethotoin OR felbamate OR fosphenytoin OR gabapentin OR lignocaine OR lamotrigine OR levetiracetam OR lidocaine OR hydantoins OR levetiracetam OR methsuximide OR oxcarbazepine OR paraldehyde OR phenacemide OR phenytoin OR pregabalin OR primidone OR succinimide OR tiagabine OR topiramate OR valproate OR vigabatrin OR zonisamide)

AB (carbamazepine OR clorazepate OR clobazam OR clonazepam OR chlordiazepoxide OR divalproex OR ethosuximide OR ethosuximide OR ethotoin OR felbamate OR fosphenytoin OR gabapentin OR lignocaine OR lamotrigine OR levetiracetam OR lidocaine OR hydantoins OR levetiracetam OR methsuximide OR oxcarbazepine OR paraldehyde OR phenacemide OR phenytoin OR pregabalin OR primidone OR succinimide OR tiagabine OR topiramate OR valproate OR vigabatrin OR zonisamide)

TI anticonvulsant* OR AB anticonvulsant*

TI ACTH OR AB ACTH

S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9

MH "Clinical Trials+"

PT Clinical trial

TI clinic* N1 trial* or AB clinic* N1 trial*

TI ( singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl* ) and TI ( blind* or mask* )

AB ( singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl* ) and AB ( blind* or mask* )

TI randomi?ed control* trial* or AB randomi?ed control* trial*

MH "Random Assignment"

TI random* allocat* or AB random* allocat*

MH "Placebos"

TI placebo* or AB placebo*

MH "Quantitative Studies"

S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17 OR S18 OR S19 OR S20 OR S21

S4 AND S10 AND S22

Appendix 5. Web of Science search strategy

TS=((( cocaine* OR crack) AND (abuse* OR depend* OR addict* OR disorder* OR detox* OR withdraw* OR abstinen* OR abstain*)))

TS=(anticonvulsant* OR carbamazepine OR clorazepate OR clobazam OR clonazepam OR chlordiazepoxide OR divalproex OR ethosuximide OR ethosuximide OR ethotoin OR felbamate OR fosphenytoin OR gabapentin OR lignocaine OR lamotrigine OR levetiracetam OR lidocaine OR hydantoins OR levetiracetam OR methsuximide OR oxcarbazepine OR paraldehyde OR phenacemide OR phenytoin OR pregabalin OR primidone OR succinimide OR tiagabine OR topiramate OR valproate OR vigabatrin OR zonisamide)

TS= clinical trial* OR TS=research design OR TS=comparative stud* OR TS=evaluation stud* OR TS=controlled trial* OR TS=follow‐up stud* OR TS=prospective stud* OR TS=random* OR TS=placebo* OR TS=(single blind*) OR TS=(double blind*)

#1 AND #2 AND #3

Indexes=SCI‐EXPANDED, SSCI, A&HCI Timespan=All years

Appendix 6. Criteria for risk of bias assessment

| Item | Judgment | Description |

| 1. Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process such as random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimisation |

| High risk | Investigators describe a non‐random component in the sequence generation process such as odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; hospital or clinic record number; alternation; judgement of the clinician; results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; availability of the intervention | |

| Unclear risk | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement of low or high risk | |

| 2. Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Low risk | Investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because one of the following, or an equivalent method, was used to conceal allocation: central allocation (including telephone, web‐based and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation); sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes |

| High risk | Investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments because one of the following methods was used: open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or nonopaque or were not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure | |

| Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk. This is usually the case if the method of concealment is not described or is not described in sufficient detail to allow a definitive judgement | |

| 3. Blinding of participants and providers (performance bias); objective outcomes |

Low risk | No blinding or incomplete blinding, but the review authors judge that the outcome is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding Blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and unlikely that blinding could have been broken |

| High risk | No blinding or incomplete blinding, and outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding Blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding |

|

| Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk | |

| 4. Blinding of participants and providers (performance bias); subjective outcomes |

Low risk | Blinding of participants and providers and unlikely that blinding could have been broken |

| High risk | No blinding or incomplete blinding, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding Blinding of key study participants and personnel attempted, but likely that blinding could have been broken, and the outcome is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding |

|

| Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk | |

| 5. Blinding of outcome assessor (detection bias); objective outcomes |

Low risk | No blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding Blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that blinding could have been broken |

| High risk | No blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding Blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding |

|

| Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk | |

| 6.Blinding of outcome assessor (detection bias); subjective outcomes |

Low risk | Blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that blinding could have been broken |

| High risk | No blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding Blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding |

|

| Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk | |

| 7. Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias); for all outcomes except retention in treatment or dropout |

Low risk | No missing outcome data Reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias) Missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size Missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods All randomly assigned participants are reported/analysed in the group to which they were allocatedby randomisation, irrespective of non‐compliance and co‐interventions (intention to treat) |

| High risk | Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardised difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size ‘As‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation |

|

| Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk (e.g. number randomised not stated, no reasons for missing data provided; number of dropouts not reported for each group) | |

| 8. Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | Study protocol is available, and all of the study’s prespecified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the prespecified way Study protocol is not available, but it is clear that published reports include all expected outcomes, including those that were prespecified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon) |

| High risk | Not all of the study’s prespecified primary outcomes have been reported One or more primary outcomes are reported using measurements, analysis methods or subsets of the data (e.g. subscales) that were not prespecified One or more reported primary outcomes were not prespecified (unless clear justification for their reporting is provided, such as an unexpected adverse effect) One or more outcomes of interest in the review are reported incompletely, so that they cannot be entered in a meta‐analysis The study report fails to include results for a key outcome that would be expected to have been reported for such a study |

|

| Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk |

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Any anticonvulsant versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Dropout | 20 | 1695 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.95 [0.86, 1.05] |

| 2 Use of cocaine (self reported or objective) | 11 | 867 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.92 [0.84, 1.02] |

| 3 Side effect | 8 | 775 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.39 [1.01, 1.90] |

| 3.1 New subgroup | 8 | 775 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.39 [1.01, 1.90] |

| 4 Craving | 8 | 428 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.25 [‐0.59, 0.09] |

| 5 Severity of dependence (ASI) | 6 | 290 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 0.03 [‐0.02, 0.08] |

| 6 Severity of dependence (CGI‐O) | 5 | 277 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.11 [‐0.42, 0.20] |

| 7 Depression (HAM‐D) | 3 | 80 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.80 [‐0.59, 4.19] |

| 8 Anxiety (HAM‐A) | 3 | 78 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.79 [‐1.02, 4.60] |

| 9 Compliance | 6 | 343 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.93, 1.08] |

| 10 Compliance | 5 | 426 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | 1.42 [‐4.80, 7.64] |

Comparison 2. Single anticonvulsant versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Dropout | 19 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 Carbamazepine vs placebo | 6 | 464 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.87, 1.13] |

| 1.2 Tiagabine vs placebo | 3 | 213 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 1.01 [0.56, 1.82] |